FOUR

THE CLINTON PREDICAMENT

A little more than a century separated the end of the Andrew Johnson impeachment ordeal and the beginning of Richard Nixon’s. After the latter, it would be merely two decades before the next serious impeachment effort was set in motion.

On August 9, 1994, almost 20 years to the day that Nixon resigned, a three-judge panel appointed former U.S. solicitor general Kenneth Starr as independent counsel to investigate the 42nd president of the United States, William Jefferson Clinton. Clinton’s defenders would insist that the entire ordeal was about sex, but the subject of Starr’s initial investigation was hardly sexy: Clinton’s involvement as an investor in the Whitewater real estate development in Arkansas in the 1970s and early ’80s, a decade before he was elected president. But when it comes to independent counsels, way leads on to way and investigations dramatically change course. Starr’s inquiry eventually led to Clinton’s impeachment on charges unrelated to Whitewater.

In May 1994, 15 months into Clinton’s presidency, an Arkansas government employee named Paula Jones filed suit against Clinton in federal court in Arkansas, demanding $700,000 in damages for sexually harassing her in May 1991 while he was governor of Arkansas. Ms. Jones alleged that, at a conference of state employees, Clinton had a state trooper tell Jones that he wanted to see her in his hotel room. The trooper escorted her to Clinton’s suite, where Clinton exposed himself and asked Jones to kiss his genitals. When she refused his advances, he told her to keep quiet about the interaction.

As civil suits tend to do, Jones v. Clinton dragged on for some time with limited progress. The same could be said of Independent Counsel Starr’s investigation of Whitewater. Starr was actually not the first independent counsel to probe Whitewater. In January 1994, Attorney General Janet Reno had appointed Robert Fiske to that post. On June 30, Fiske produced an interim report finding no wrongdoing by Clinton. On that same day, however, Clinton signed into law a bill replacing the old “special prosecutor” office with an “independent counsel.” Whereas special prosecutors had been chosen by the attorney general, the new statute called for appointment of the independent counsel by a “Special Division”—a panel of three court of appeals judges themselves appointed by the chief justice.

Reno requested that Fiske be appointed to the new position in order to maintain continuity with his investigation. However, the panel, led by conservative Judge David Sentelle of the D.C. Circuit, opted for Starr instead. Although Fiske was a Republican, in no way beholden to Reno or President Clinton, the panel claimed that his earlier appointment by Reno created an appearance of impropriety. Starr himself was a long-time Republican and federal court of appeals judge before his selection as solicitor general by President George H.W. Bush. He was in private practice when tapped to be independent counsel.

Monica Lewinsky government identification photo, dated 1997

While Starr investigated Whitewater, President Clinton entered far more dangerous territory. In November 1995, he and Monica Lewinsky, a 22-year-old unpaid intern who worked in the West Wing of the White House, commenced an intimate relationship. Over the next six months, on at least eight occasions Clinton and Lewinsky engaged in sexual relations in rooms adjacent to the Oval Office. Their encounters typically involved oral sex but never intercourse.

In April 1996, Lewinsky was transferred to a secretarial job with the Defense Department, allegedly a deliberate move by White House aides to put distance between the president and his intern. Though Clinton allegedly broke off the relationship in May, he and Lewinsky remained in touch, occasionally exchanging gifts and engaging in phone sex. She sometimes visited the White House, where she was ushered in to see the president by his secretary, Betty Currie. Clinton and Lewinsky engaged in sexual relations twice more in early 1997, before Clinton again broke things off in May.

Thereafter, their relationship consisted largely of phone calls in which Lewinsky, who disliked her job at the Pentagon, beseeched the president to help her find work elsewhere. He put her in touch with his friend Vernon Jordan, a prominent Washington attorney whose intervention eventually helped Lewinsky land a job with Revlon, though the offer was later rescinded.

Meanwhile, on May 27, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Paula Jones’s lawsuit against President Clinton could go forward while he was in office. Eight justices stated that conclusion uncategorically, whereas Stephen Breyer left the door open for the president to establish that the lawsuit would interfere with his constitutional responsibilities (in which case it would be postponed until he was no longer in office).

After the Supreme Court decision, the trial judge in the suit, Susan Webber Wright, ruled that during pretrial “discovery” (the legal process for obtaining information from the other side), Jones’s lawyers could inquire about improper relationships between Clinton and other women who served under him. Accordingly, they sought to depose Lewinsky, whose relationship with Clinton they learned about from her friend Linda Tripp. Upon hearing from his attorneys that Lewinsky’s name was on the list of people Jones’s lawyers wished to depose, Clinton encouraged Lewinsky to claim that her visits to the White House were either to see Betty Currie or to deliver documents.

In December, Lewinsky received a subpoena to appear for a deposition in late January and to bring with her any gifts she had received from Clinton. Lewinsky drafted an affidavit, with the assistance of counsel, asserting that she had not had a sexual relationship with Clinton. She also transferred to Currie some of Clinton’s gifts to her.

On January 17, 1998, Jones’s lawyers deposed Clinton. He denied having had sexual relations with Lewinsky. The next day, he summoned Currie to his office and made highly suggestive comments that appeared to be telling Currie what to say if she were asked about his relationship with Lewinsky. (“We were never really alone” and “Monica came on to me and I never touched her, right?”) A few days later, he had another conversation with Currie along the same lines.

On the day before Clinton’s deposition, Independent Counsel Starr, now in his fourth year investigating Whitewater, obtained from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia permission to expand his investigation to include Clinton’s possible obstruction of justice with respect to the Jones’s lawsuit. Starr knew about Clinton’s relationship with Lewinsky from Tripp, who secretly taped her conversations with Lewinsky about Clinton. (Tripp claimed to do so to protect herself from perjury if she were deposed by Jones’s lawyers, though circumstantial evidence suggests that she wished to bring Clinton down.)

On that same day, attorneys from Starr’s office approached Lewinsky and told her she was vulnerable to prosecution for perjury and obstruction of justice. They offered her immunity if she would record conversations between herself and Clinton and Jordan. She declined.

When media reports revealed Starr’s investigation of his involvement with Lewinsky, Clinton publicly denied any sexual relationship, most famously in his nationally televised declaration on January 26 that “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.”

On April 1, Judge Wright granted summary judgment for Clinton in the Paula Jones lawsuit, finding that even if Clinton did what Jones accused him of, his conduct did not rise to the level of “criminal sexual assault” (as Jones had alleged) because it involved no physical contact, and she could not prevail on her claim of sexual harassment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act because she failed to show that she suffered “tangible job detriment.” Jones’s lawyers announced their intention to appeal the decision.

With the lawsuit at least temporarily sidelined, Clinton’s denials held up for several months. They began to unravel on July 28 when Lewinsky accepted an offer of immunity from Starr’s office. She testified before a grand jury and turned over extensive documentation of her affair with Clinton (which was buttressed by several witnesses, including Bettie Currie and secret service agents). The smoking gun, so to speak, was Lewinsky’s blue dress, stained by semen shown by DNA tests to have come from Clinton.

President Bill Clinton at his desk in the Oval Office

Before the results of the DNA tests were announced, Clinton, from the White House, testified before a grand jury over closed-circuit television on August 17. He acknowledged “inappropriate intimate contact” with Lewinsky but, while refusing to go into detail, insisted that he had nevertheless not testified falsely during his deposition in the Jones case. Rather, Clinton claimed to have clung to the definition of “sexual relations” given at the deposition, which did not specifically include oral-genital contact. Thus, he maintained, his encounters with Lewinsky “did not constitute sexual relations as I understood the term to be defined at my January 17, 1998, deposition.”

Clinton also insisted that he spoke truthfully when testifying at the deposition that he and Lewinsky were rarely alone, since there were other people “in the vicinity.” He denied having encouraged her or Bettie Currie to lie or to conceal evidence in any way. He claimed that his instructions to Currie were designed solely to refresh her recollection.

On September 9, three weeks later, Independent Counsel Starr submitted a report to Congress. The Starr Report stated at the outset that it contained “substantial and credible information that President William Jefferson Clinton committed [multiple] acts that may constitute grounds for an impeachment,”1 most of which stemmed from lying under oath during his deposition in the Jones case and before the grand jury; attempting to suborn Betty Currie; and attempting to obstruct justice by encouraging Lewinsky to file a false affidavit and not to comply with the subpoena to turn over gifts.*

Calls for Clinton’s impeachment, which had become frequent once he acknowledged the sexual relationship with Lewinsky a few weeks earlier, intensified. When on October 5 the House Judiciary Committee met to consider impeachment for the first time, battle lines were drawn. Republican members, who were in the majority, harkened back to the last time the House had considered impeachment—Watergate. Democrats scoffed at the comparison. Democrat John Conyers from Michigan, the one member of the Judiciary Committee who had sat on the committee in 1974, said, “This is not Watergate. It is an extramarital affair.”2 (Ironically, Conyers would be forced to resign in 2017 over allegations of sexual harassment.) South Carolina Republican Lindsey Graham was a rare member to stake out a middle ground: “Is this Watergate or Peyton Place? I don’t know.”3

But most members knew exactly how they felt, and the respective opening statements by majority and minority counsel suggested an unbridgeable divide. Republican counsel David Schippers described “an ongoing series of deliberate and direct assaults by Mr. Clinton upon the justice system of the United States,”4 whereas Democratic counsel Abbe Lowell insisted that Clinton’s wrongdoing came down to three words: “lying about sex.”5 The serious wrongdoing in the case, according to Lowell, was at Clinton’s expense: He was the victim of a politically motivated lawsuit and an overzealous independent counsel.

The committee adopted by straight party line vote (21–16) a proposal by its chairman, Republican Henry Hyde of Illinois, modeled closely on a similar effort to investigate Watergate a quarter century earlier. The resolution, if adopted by the full House, would establish an “impeachment inquiry” by the committee and give it subpoena power.

Unlike in the Judiciary Committee, sentiments in the full House of Representatives did not break down entirely along partisan lines: A number of conservative Democrats pronounced themselves disgusted by Clinton’s behavior and favored pursuing impeachment. When on October 8 the House authorized an inquiry into impeachment, the vote was 258–176, with 31 Democrats joining Republicans. (By contrast, the House vote to pursue impeachment of Nixon had been 410–4.)

In the midterm elections less than a month later, Democrats did surprisingly well, gaining five seats in the House. It was the first time since the early 19th century that the president’s party did not lose seats (often dozens) in the sixth year of an administration. The elections seemed like a clear repudiation of the move to impeach Clinton, and left the Republicans with just a tiny majority—223 members to 211 Democrats. Speaker Newt Gingrich, who had pushed impeachment, resigned from the House.

If the election gave the Republicans second thoughts about impeachment, it did not stop them from moving forward. This may seem surprising, but in 1998 impeachment did not seem quite as big a deal as it once had. To some extent, it had been normalized by Watergate. Whereas the Andrew Johnson fiasco led to avoidance of impeachment for the next century, the successful pursuit of Richard Nixon produced the reverse effect. In the 25 years between the Nixon and Clinton impeachment efforts, there had been six serious impeachment investigations and three actual impeachments. (There had been none in the previous 38 years.) All three involved judges, and all three resulted in convictions in the Senate. The most recent two involved perjury—Alcee Hastings and Walter Nixon (no relation to Richard), convicted in 1988 and 1989 respectively. Hastings was elected to Congress in 1993, and thus voted on the Clinton impeachment!

Sixty-seven of the House members who voted on Clinton’s impeachment were in Congress during the Nixon impeachment process, including seven who served on the House Judiciary Committee that approved articles of impeachment against Nixon. Seven members of the Senate who tried Clinton had been in Congress during the proceedings involving Nixon. Fred Thompson, a lawyer for the Senate Watergate committee, was now a senator from Tennessee.

On November 9, just six days after Republicans’ poor performance in the midterms, the House Judiciary Committee held hearings concerning impeachment. Nineteen experts testified about whether the Constitution contemplates impeachment for the kinds of acts Clinton allegedly committed. The experts solicited by Republicans claimed that Clinton’s behavior offered textbook examples of impeachable offenses; those summoned by Democrats claimed that impeachment was reserved for actions more egregious and more directly implicating the president’s official responsibilities.

On November 13, Clinton and Paula Jones reached an agreement to settle her lawsuit, with Clinton paying Jones $850,000 but not admitting guilt. (Jones’s appeal of the dismissal of her suit was pending at the time.) The White House now felt in position to put the entire affair behind it and privately supported Democrats in Congress who tried to persuade Republicans to formally “censure” the president as an alternative to impeachment. Republicans, having come too far to settle for a mere statement of condemnation, declined the overtures.

On November 19, Independent Counsel Starr testified before the Judiciary Committee. The session proved contentious, to put it mildly. Before Starr had even been sworn in, Representative Conyers called him a “federally paid sex policeman.”6

Starr’s two-hour opening statement painstakingly covered Clinton’s sins, but he also exonerated Clinton with respect to various matters he had investigated before Monica Lewinsky came along: Whitewater, the so-called “Travelgate” scandal (various White House office workers being fired, allegedly to make room for friends of the Clintons), and the White House’s alleged improper collection of FBI files. Starr presented himself as a pure officer of the court who sought nothing but justice: “I am not a man of politics, of public relations, or of polls.”7

Democrats weren’t buying it. In the course of his hour-long questioning of the witness, Democrat counsel Abbe Lowell hardly asked about the evidence and allegations against Clinton. Instead, he sought to paint Starr as a partisan inquisitor, emphasizing his contacts with Paula Jones’s lawyers and his failure to report possible conflicts of interest when appointed independent counsel in the first place.

Each member of the committee was allotted five minutes to question Starr. Democrats used theirs as much to speechify as to question the witness, whereas Republicans lobbed him softballs. The prime-time showdown (literally, as it aired at 8:30 p.m.) was between Starr and Clinton’s personal counsel, David Kendall. Kendall, too, spent no time on the allegations against his client. Instead, he sought to prosecute Starr. Among his many accusations, perhaps the most serious was that Starr’s team engaged in illegal leaking of grand jury testimony on an unprecedented scale. Starr claimed the leaks actually came from Clinton’s lawyers. Impasse.

Throughout his allotted 90 minutes, Kendall dripped contempt for Starr. Republican counsel David Schippers offered a slightly different perspective. “I’ve been an attorney for almost forty years,” he said to Starr. “I want to say I’m proud to be in the same room with you and your staff.”8

The next day, November 20, Samuel Dash, the well-regarded Watergate investigator who had been serving as Starr’s ethics adviser, stepped down from that position, claiming that Starr acted improperly by appearing as an advocate before the committee.

Shortly after Clinton’s grand jury testimony, the House Judiciary Committee sent the president 81 questions to be answered under oath. On November 27, the White House delivered to the Judiciary Committee Clinton’s answers, which for the most part reiterated what he had told the grand jury. His tone was defiant, any cooperation reluctant. For example, when asked whether he had taken an oath to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, Clinton responded, “I do not recall the precise wording of the oath.”9

On December 1, the Judiciary Committee heard from two ordinary citizens who had been convicted of perjury in connection with civil suits. One of them, a doctor for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs convicted for falsely denying sexual relations with a patient, told the committee that the president “must abide by the same laws as the rest of us.”10 If such testimony hit home, the same hearing also produced a less successful witness for the Republicans: Charles Wiggins, a senior federal court of appeals judge who had been a member of the House Judiciary Committee that recommended the impeachment of Richard Nixon. Wiggins testified that, while Clinton did commit impeachable offenses, they were “not of the gravity to remove him from office.”11

On December 8, Clinton’s attorneys opened the defense case. In his opening statement, Greg Craig acknowledged that Clinton’s actions were immoral, but insisted they were not impeachable. Craig called several witnesses designed to establish that Clinton’s misdeeds bore no relation to Richard Nixon’s, including Richard Ben-Veniste, a Watergate prosecutor; three members of the Judiciary Committee in 1974 who voted to impeach Nixon; and William Weld, a former Republican governor who had served on the impeachment inquiry staff (alongside Hillary Rodham) during Watergate.

One of Clinton’s own lawyers, Chuck Ruff, had been a Watergate special prosecutor, and now he made a closing argument for the defense. Ruff told members of the committee that they “cannot overturn the will of the people.” Such language was a redundant reminder that impeachment is at least partly a political process. (Indeed during this hearing and beyond, Clinton met and spoke on the phone with several moderate Republicans, seeking their support if the case came to the full House.)

Under aggressive questioning from Republican members, Ruff skillfully set forth the Clinton line with respect to perjury: The president had been, at least in his own mind, “evasive but truthful.”12 But, Ruff implied, even if Clinton had falsified which parts of Lewinsky’s body he had touched, and thus technically had been wrong to claim they did not have sexual relations under the definition used during his deposition, did Congress really wish to impeach a president over that?

In his closing statement, House Democratic counsel Lowell drew a dryly amusing contrast with Watergate. There, tapes proved that Nixon misused the CIA, FBI, and IRS. Here, the relevant tapes involved “Monica Lewinsky and Linda Tripp talking about going shopping.”13 How could anyone compare the abuse of constitutional powers at the heart of Watergate with lies about a consensual private affair?

Lowell’s Republican counterpart, David Schippers, advanced a drastically different view: “If you don’t impeach,” he told the members, “then no House of Representatives will ever be able to impeach again.”14 Perhaps Schippers did not know that, at the Andrew Johnson impeachment and trial, pro-impeachment congressmen had made the same claim.

Late in the afternoon of the next day, December 11, just as the Judiciary Committee concluded debate and was about to commence a vote on impeachment, President Clinton walked out to the Rose Garden and made a statement. He apologized more fully than ever before; he was “profoundly sorry for all I have done wrong in words and deeds.”15

Ten minutes later, the clerk of the Judiciary Committee called the roll. The Committee approved three articles of impeachment, two charging perjury (one in Clinton’s deposition in the Jones case, the other before the grand jury) and one obstruction of justice. Two of the votes went according to straight party-line vote, whereas the perjury charge stemming from Clinton’s deposition in the Jones case produced a single defection (Republican Lindsey Graham voting no). The committee recessed at 9:15 p.m., leaving the vote on the fourth article for the following morning.

Article Four charged abuse of power stemming from Clinton’s numerous lies to the American people and in his answers to the 81 questions from the Judiciary Committee, as well as frivolously invoking executive privilege to impede the independent counsel’s investigation. However, as this article was perceived to lack support, Republicans amended it the following morning to strike all of it except Clinton’s false answers to the committee’s questions. The stripped-down article passed 21–16 along straight party lines. The committee would send the full House four articles of impeachment.

During the following week, members of the House, especially those considered swing votes, received thousands of phone calls and emails. They also took note of polls showing that roughly 60 percent of the American people opposed impeachment. Democrats continued to lobby their Republican colleagues to accept the compromise of censuring Clinton, a measure approved of by a majority of Americans.

On December 16, 1998, the day before the full House of Representatives was scheduled to begin impeachment hearings, Clinton ordered commencement of a four-day cruise missile attack on Iraq. The mission was supposedly retaliation for Saddam Hussein’s failure to comply with U.N. resolutions to permit inspections designed to ensure that he retained no weapons of mass destruction.

Also on December 16, David Schippers arranged for fence-sitting members of the House (and any other members who wanted to join them) to see an exhibition of evidence that, because it came in late and was inflammatory, Chairman Hyde excluded from the Judiciary Committee hearings: documents supporting the claim that 20 years earlier Clinton had raped a woman, Juanita Broaddrick. (Broaddrick did not come forward at the time, but filed an affidavit with Paula Jones’s lawyers in 1997.)

On December 17, the House convened in the morning and passed a resolution 417–5 supporting the troops flying combat missions in Iraq. House Speaker-to-be Bob Livingston (anointed Gingrich’s successor, though it could not become official until the next congressional session in January) announced a one-day postponement of the impeachment hearings on account of the military action. Democrats protested to no avail that the postponement should last until the military action was complete.

Livingston had other problems on his hands besides angry Democrats. That day, lured by a $1 million offer by Hustler publisher Larry Flynt, a woman came forward and revealed that she had an affair with Livingston years earlier. Livingston confessed to his colleagues that he had indeed “on occasion strayed from my marriage,”16 an awkward admission just as Livingston’s troops sought to impeach a president for misconduct rooted in adultery.

On Friday, December 18, at 9:00 a.m., the House of Representatives convened to consider the second presidential impeachment in U.S. history.

In the opening statement favoring impeachment, Chairman Henry Hyde immediately clarified that this “is not a question about sex” but rather “a question of the willful, premeditated, deliberate corruption of the nation’s system of justice.” He closed his eloquent remarks by urging the House to “keep our appointment with history.”17 He received a standing ovation . . . from the Republicans.

House minority leader Dick Gephardt opened for the Democrats and, like most Clinton defenders, did not address the specific charges against the president. Instead, he waged a series of complaints: 1) the debate should not be happening while U.S. troops were in combat; 2) the punishment of impeachment was disproportionate to President Clinton’s misconduct; and 3) it was unfair that the censure option was not being brought to the floor. “You are trampling the Constitution,” he scolded Republicans, and received a standing ovation . . . from the Democrats.18

Twelve hours of angry debate ensued, with Republicans savaging Clinton and Democrats accusing Republicans of a “coup d’état” and “constitutional assassination.”

The following morning, Livingston took to the floor and called on Clinton to resign. Democrats screamed at him “You resign!” and Livingston proceeded to do exactly that—or, at any rate, to renounce his claim to be the next Speaker of the House. Was this real life or a Tom Clancy novel? A president on the verge of impeachment was bombing a foreign country and the impeaching party had just lost its new leader to a scandal of his own.

Both sides immediately seized on Livingston’s move to support their narrative. To Republicans, he had displayed what honorable people do under such circumstances: Clinton should follow Livingston’s lead and resign or else be made to leave office involuntary. To Democrats, Livingston was another victim of a growing “sexual McCarthyism” that had to stop. Neither side would get its wish.

Just a few hours after Livingston’s dramatic announcement, and some impassioned pleas from both sides, the roll was called. The House of Representatives adopted two of the four proposed articles of impeachment.

The vote was 228 to 206 supporting impeachment for Clinton’s perjury before the grand jury, with all but 10 members (five in each direction) voting the party line. The vote on obstruction of justice was 221–212, with all but five Democrats voting no and all but 12 Republicans voting yes. The other two articles, also based on allegations of perjury, were defeated. One, alleging falsehoods in Clinton’s deposition in the Jones lawsuit, went down 229–205, with the same five Democrat yes votes and 29 Republicans breaking ranks to vote no. The other, alleging falsehoods and non-responses to the 81 questions propounded by the Judiciary Committee, was defeated 285–148, with only one Democrat voting yes and 81 Republicans in opposition.

The vote sent the case to the Senate for trial, but more immediately it sent House Democrats scurrying to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Eighty of them piled into buses and cars that took them to the White House for a show of solidarity with the impeached president.

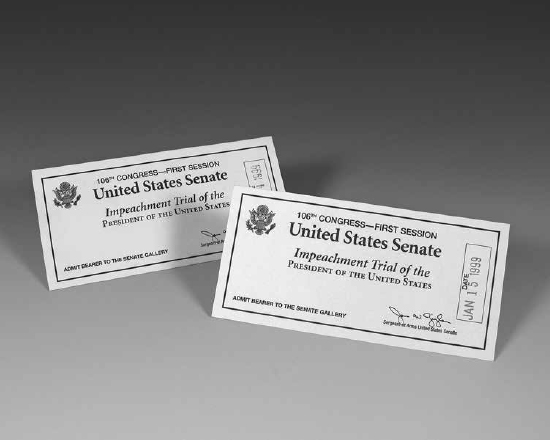

Two tickets for Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial, January 14–15, 1999.

The Republicans had prevailed in the House, but polls gave them no cause to gloat. The public continued to oppose the removal of Clinton from office and showed little stomach for a drawn-out process. The House managers wanted to call at least 15 witnesses, but Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, who held several secret meetings with pollsters and political consultants, wanted no part of that. After considerable internal debate, and then debate with the Democrats, Senate Republicans deferred the question of witnesses until mid-trial.

As this and other questions about trial procedure were negotiated among the senators, the House managers, and Clinton’s attorneys, one thing was understood and from time to time articulated: There was virtually no chance Clinton would be convicted. In a private session, Senator Ted Stevens, a Republican from Alaska, told the House managers that they would be wasting their time calling witnesses, because at least 34 senators would never vote to convict. This was Alice in Wonderland: Verdict first, trial later.

To those who refused to consider the case a done deal (out of either excessive optimism or pessimism), the identity of the person presiding over the trial, Chief Justice William Rehnquist, gave each side cause for concern. Rehnquist was a lifelong Republican, a conservative justice appointed to the Court by Nixon and elevated to Chief Justice by Ronald Reagan. On the other hand, back in 1992 he had written Grand Inquests, a book criticizing the politicized impeachment of Andrew Johnson.

Whatever the chief justice’s feelings about Clinton’s trial, he stayed true to his own sartorial preferences. As he had for the last few years, he wore gold braids on the sleeves of his otherwise traditional black robe, homage to a Gilbert and Sullivan opera. He had witnessed a performance of Iolanthe in which the Lord Chancellor wore such a costume.

The trial formally commenced on January 7. Rehnquist and the senators were sworn in by 96-year-old president pro tempore Strom Thurmond, whose father was alive during the impeachment of Andrew Johnson. Following the swearing in, the first week was given over to wrangling, most of it behind closed doors, over the still-not-determined trial processes.

The trial began in earnest on January 14, with the managers’ opening statements. There would be quite a few such statements—the Republicans had put together a team of 13 managers, all House members, all of whom made opening remarks.

Their addresses mixed high-minded rhetoric about the rule of law with detailed factual recitation of the president’s misdeeds and clips of his many misstatements (including “I did not have sexual relations with that woman”). The first round of opening statements was effective enough that it reportedly had some Democratic senators reconsidering their opposition to conviction. The Senate recessed at 7:00 p.m.

The next day brought opening statements by five more managers and, near the end of the day, the first formal objection. Democratic Senator Tom Harkin rose to object when manager Bob Barr referred to the senators as “jurors.” The managers had used the term repeatedly, but for some reason Harkin held his objection until now. Quoting from the Constitution and The Federalist Papers, he argued at length that the senators were really judges with a broader mandate than the term jurors implied.

Chief Justice Rehnquist agreed, and admonished the managers not to use the term. Republicans were furious, though presumably more on dubious principle (whose side was the chief justice on?) than anything else. But they decided it wasn’t worth overruling Rehnquist, especially since his ruling seemed eminently defensible.

When the Senate met the next day, Saturday, January 16, the managers presented the last of their opening statements. Lindsey Graham acknowledged that “to set aside an election is a very scary thought in a democracy,” but claimed the Senate had little choice—a perjurer could not be the nation’s chief magistrate. He urged the Senate to “cleanse this office.”19

The president’s defense commenced on January 19, with a statement by Charles Ruff, a brilliant attorney who had been wheelchair-bound from the age of 25 (having become paralyzed through a non-diagnosed illness) and would pass away the next year. Ruff succeeded in poking holes in the managers’ case, but arguably the more impressive pro-Clinton statement came later that night from the president himself, during the annual State of the Union address. Clinton actually made no mention of his trial, but earned rave reviews for his upbeat tone, bipartisan message, and even for mouthing “I love you” to his wife, who sat up in the gallery with, among others, civil rights hero Rosa Parks.

The next day brought opening statements from Clinton’s attorneys Greg Craig and Cheryl Mills. The latter, an African American woman (the 13 House managers were all white men), received powerful praise from all corners. She compared Clinton to Thomas Jefferson, John F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr., great but flawed men whose sexual escapades did not detract from their commitment to human rights.

The following day, January 21, brought forth more Clinton defenders. His attorney David Kendall did a workmanlike job, but Dale Bumpers, Clinton’s fellow Arkansan whose 24-year tenure in the Senate had ended with his retirement just three weeks earlier, stole the show. Most memorably, the folksy Bumpers said: “When you hear somebody say ‘this is not about sex,’ it’s about sex.”20

Friday, January 22, was the first of two days set aside for questions from the senators and answers by the attorneys. Senators submitted questions for one side or the other to the chief justice, who read them aloud. Many of the questions were planted by the attorneys, giving them a chance to play gotcha with factual errors by the other side. Occasionally, a question broke through the rat-a-tat-tat and got to the heart of the matter. One such question came from Robert Byrd, the crusty Democrat from West Virginia, the longest-serving senator in U.S. history and a rare Democrat considered a possible yes vote to convict Clinton.

Byrd quoted from Federalist 65 that impeachment redresses “the abuse or violation of some public trust” and asked Clinton’s lawyers, “How does the president defend against the charge that, by giving false and misleading statements under oath, [he] abused or violated some public trust?”21 Ruff responded that Clinton’s false statements were in the context of a lawsuit over a private matter and it was absurd to believe that such misconduct is so serious as to threaten the country or justify overturning the will of the people. Apparently, the answer landed. Later that day Byrd put out a statement calling for dismissal of the charges and an end to the trial.

Another question that proved influential came jointly from Democratic senators Herbert Kohl and John Edwards. Assuming Clinton did in fact commit perjury and obstruction of justice, they asked, “can reasonable people disagree with the conclusion that . . . he must be convicted and removed from office?”22

Lindsey Graham responded, “Absolutely. You have to consider what is best for this nation. . . . When you take the good of this nation, the upside and the downside, reasonable people can disagree on what we should do.”23

It was a reasonable answer, but devastating for the case against Clinton. For one thing, it was a hard sell that it is “best for the nation” to remove a president against the will of the people, who not only elected him twice but clearly (as reflected in public opinion polls) did not want him removed. For another, the very idea that “reasonable people can disagree” about whether to remove the president could be seen as good reason not to remove him. It was like the prosecutor in a criminal case telling the jury that reasonable people could disagree about whether the defendant is guilty. If so, how could the jury find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt? Since conviction and removal of a president is a last resort, undoing a democratic election, it arguably should be reserved for cases—like Nixon’s—where pretty much all people of good will agree that it is necessary. Clinton’s lawyers pounced on Graham’s candid concession and brought it up periodically for the duration of the trial.

On January 27, the Senate voted on Byrd’s motion to dismiss. It fell 56–44, a near party-line vote, with only Wisconsin Democrat Russ Feingold crossing party lines and voting against dismissal. It was a pyrrhic victory for the Republicans, insofar as it signaled that Clinton had at least 44 votes, 10 more than needed for acquittal.

That same day the Senate finally resolved key procedural issues that had been deferred: whether witnesses would be called and, if so, how many. The managers had pared down their wish list from 16 to three: Lewinsky, Vernon Jordan, and Sidney Blumenthal, the latter a White House aide who supposedly led a campaign to claim that Lewinsky stalked Clinton. By the same 56–44 vote, the Senate agreed to hear the testimony of the three witnesses.

But now Clinton’s team insisted that if witnesses were called, they would need additional discovery and might call witnesses of their own for rebuttal. After much wrangling, it was agreed that the three witnesses would be deposed. If their depositions produced any surprising new evidence, the Clinton side would, by agreement of the two Senate leaders (Republican majority leader Trent Lott and Democrat minority leader Tom Daschle), be given additional time to prepare and/or call witnesses of their own.

Lewinsky was deposed on February 1 but gave the House managers nothing useful. Indeed, she so easily fended off her questioner, manager Edward Bryant from Tennessee, that Clinton’s lawyers didn’t bother to question her. Manager Asa Hutchinson from Arkansas deposed Jordan the next day. Here too, nothing significant emerged. Clinton’s lawyers asked just a few questions, softballs eliciting from Jordan that the assistance he gave Lewinsky in finding a job was routine, something he did for many young people, and had nothing to do with influencing her behavior with respect to the Paula Jones lawsuit. Finally, Graham and Californian Representative James Rogan questioned Sidney Blumenthal on February 3. Blumenthal denied participating in any efforts (much less efforts spearheaded by Clinton) to smear Lewinsky.

Behind the scenes, much maneuvering now occurred. Republicans knew they did not have the votes for conviction, so they pondered lesser moves. Might they finally agree to censure the president (something some Democrats supported all along)? Or settle for “findings of fact” of his guilt by majority vote? Simply adjourn without any vote? And did they want to call the three deposed witnesses to give live testimony?

As it turned out, they could not garner sufficient support for any of those options. Instead, the managers pressed ahead with the case and showed select clips from the videotaped testimony of Lewinsky, Jordan, and Blumenthal. Clinton’s defense team, for its part, also showed select clips of Lewinsky’s and Jordan’s depositions.

On February 8, closing arguments began. After six House managers reiterated the case for conviction, Charles Ruff alone gave the White House response. The remaining seven managers spoke in rebuttal. Unsurprisingly at this point, neither side presented anything new or different. But Henry Hyde did score a clean hit in response to Ruff’s charge that the managers “wanted to win too much.” He replied that “none of the managers has committed perjury nor obstructed justice . . . nor encouraged false testimony before the grand jury. That is what you do if you want to win too badly.”24

Beginning February 9, the Senate deliberated behind closed doors for three days. On February 12, they met in open session. Each senator made a brief statement, and then the roll was called. The Senate acquitted the president (on Lincoln’s birthday, for whatever that’s worth), which by this point was a foregone conclusion. The vote to convict was 45–55 on perjury and 50–50 on obstruction. Zero Democrats supported either article. Five Republicans voted to acquit Clinton of obstruction and 10 voted to acquit him of perjury. (Arlen Specter, an iconoclastic Republican from Pennsylvania, wanted to vote “not proved”—an option, he noted, available under the law of Scotland. He ended up declaring “not proven, therefore not guilty” on both articles.)

In a sense, the key question throughout the Clinton impeachment saga was whether the case more closely resembled that of Andrew Johnson or Richard Nixon. But, in a different sense, the most salient aspect of the Clinton case distinguished it from both the Johnson and Nixon cases: There was never a realistic chance that Clinton would be removed from office. Therefore, the national ordeal was ultimately pointless.

On the eve of the House vote on impeachment, Henry Hyde had proposed a compromise. If the Democrats dropped resistance to impeachment, he would get the Senate to agree to censure rather than convict the president. At least at that moment, Hyde was conceding that he saw impeachment as symbolic: He and his fellow Republicans would feel vindicated by a bipartisan impeachment even if it did not result in Clinton’s removal from office.

One could understand Hyde’s temptation. The entire Clinton case was dogged by its partisan nature. Hyde’s compromise would flip the switch—suddenly, everything (the work of both the House and Senate) would seem bipartisan.

But impeachment is too blunt a weapon to be used to make a statement, and Hyde’s proposed solution would have been short-sighted. To see why, we need to dip back to August 20, a few months before the proposed compromise. On that day, three days after his grand jury testimony, Clinton ordered the bombing of suspected terrorist sites in Afghanistan and Sudan. Immediately came accusations of “Wag the Dog”—a reference to the 1997 movie in which a president wages war to distract the nation from a scandal. Ditto when Clinton bombed Iraq on the eve of impeachment hearings. Concern that the commander-in-chief engaged in military action for purely personal gain is terrible for the nation. Such suspicions will arise when impeachment is pursued. Suddenly, everything the president does gets seen through the impeachment lens. In addition, bitter division throughout the country is inevitable.

These things have long-term consequences. Calls to impeach Clinton’s successor, George W. Bush, and his successor, Barack Obama, became commonplace (as discussed in chapter six). Payback begets payback begets payback. When a weapon of last resort becomes a weapon of first resort, the prospect of bipartisanship disappears and our entire political process suffers. Among other things, impeachment itself becomes seen as a partisan weapon rather than a constitutional safeguard. Rare cases of clearly justified impeachment will meet a stiff knee-jerk resistance.

The Clinton impeachment itself suffered from the kind of severe partisanship that has increasingly afflicted Congress over the last several decades. Henry Hyde wanted to avoid that. He studied the work of the Rodino Committee during Watergate and modeled as much as possible after the Watergate proceedings, including the format of the articles of impeachment. But despite Hyde’s efforts, in one key respect the Clinton impeachment broke with precedent.

In 1973, the House Judiciary Committee employed both majority and minority staffers in drafting reports. In 1998, that did not happen, because the Republicans thought Democratic staffers would impede committee work.

In the end, the Clinton impeachment resembled the Andrew Johnson impeachment more than the Nixon case in two crucial respects: 1) the desire to remove the president came almost exclusively from the opposition party, and 2) Clinton did not commit clearly impeachable offenses.

But there was also a critical difference between the Johnson and Clinton cases, one that made the latter a tougher case. Complaints with Andrew Johnson revolved almost completely around his resistance to Reconstruction. In other words, he was impeached over moral and political differences—an improper use of impeachment.

By contrast, those favoring Clinton’s impeachment could make a conceptually tidy argument in good faith: Perjury and obstruction of justice undercut the ability of the courts to function, and are thus intolerable from the person constitutionally responsible for executing the laws of the land. If the president can break laws when it serves his purposes, what kind of message is sent? Since he enforces laws for everyone else, exempting himself amounts to hypocritical self-dealing.

The context surrounding the Clinton impeachment, however, muddied the matter. That context starts with the lawsuit by Paula Jones, which was, to put it charitably, thin. No credible evidence suggested retaliation by Clinton for whatever took place between Jones and him in a hotel room. Moreover, the underlying conduct, if any, took place years before Clinton was president—and Jones never came forward until he was president and she was encouraged to do so by his political enemies.

The immediate trigger was a magazine article in which unnamed Arkansas state troopers said that Clinton had a girlfriend named Paula. Jones claimed to have brought legal action because she felt harmed by that false allegation. However, Clinton had nothing to do with the article. Quite the contrary, the article defamed him as well as her. Yet Jones did not seek recourse against American Spectator magazine or the state troopers who maligned her. She took action against Clinton, who had zero to do with the allegations that infuriated her.

Moreover, Jones received financial and public relations support from organizations dedicated to destroying Clinton. (Her lawsuit was so weak that she might have had difficulty finding an attorney under normal circumstances.) In that context, Clinton found himself subject to a fishing expedition concerning women he may have been involved with, even though those relationships were at best peripherally related to Jones’s allegation. Indeed, Judge Wright later ruled that everything about Monica Lewinsky was inadmissible because “not essential to the core issues” in the case. Judge Wright, a Republican appointed to the bench by George H.W. Bush, eventually dismissed the lawsuit as lacking a legal basis.

Thus, Clinton faced irrelevant questions in a baseless lawsuit that appeared politically motivated, where honest answers threatened not just his presidency but also his marriage. In that extreme situation, he engaged in evasion and a few outright lies.

Potentially more troubling was his treatment of Betty Currie, an innocent person whom he arguably encouraged to lie—albeit, again, to defend himself from a baseless and ill-motivated lawsuit that threatened his presidency and marriage. But if he wronged Currie, it was not a wrong against the nation, certainly not in Clinton’s capacity as president.

Clinton told lie upon lie, some under oath. Judge Wright, despite dismissing Jones’s lawsuit, fined him $90,000 for contempt of court, and both the Arkansas Bar Association and United States Supreme Court suspended his license to practice law. These punishments were just. One can disapprove of Clinton’s impeachment without condoning his actions.

The case for impeaching Clinton, while not frivolous, was not compelling. It represents a middle ground in between the Johnson and Nixon cases. Taken as a trio, the three cases offer valuable lessons to which we turn in chapter six. First, we consider one other vehicle besides impeachment for removing an unfit president.

* The Starr Report mentioned the Whitewater land deal, which Starr was initially hired to investigate, only in passing. Robert Ray, who succeeded Starr as independent counsel when Starr stepped down in 1998, later concluded that there was insufficient evidence to proceed against Clinton with respect to Whitewater.