FIVE

“Unable to Discharge”

When arguing that impeachment does not require a criminal act, commentators give examples they consider obvious. Suppose the president was perpetually drunk or went AWOL for a prolonged period. Such conduct, though not criminal, would clearly warrant removal from office. However, the examples are more problematic than they may seem.

As we have seen, one can effectively commit crimes (as in “high crimes and misdemeanors”) against the Constitution without necessarily violating specific laws. Richard Nixon’s misuse of government agencies provides a perfect example. But drunkenness? It seems at a minimum a stretch—and maybe even a category mistake—to consider that a “crime” by any definition.

And yet, commentators on impeachment always insist that neglecting one’s presidential responsibilities would indeed constitute an impeachable offense. This conclusion has a firm pragmatic basis: A drunken or otherwise obviously unfit president must be replaced, and impeachment was historically the only available vehicle for doing so. Stretching normal language seemed a reasonable price to pay to produce a result necessary for the nation’s well-being. The fault lay in the failure of the original Constitution to provide for removal of a president who is unfit but has committed no grievous offense.

Actually, the original Constitution did address what happens when the president is unable to do the job, but only as part of a broader provision governing what happens when the president is removed. Article I, Section 2, Clause 6 provides: “In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.”

This provision served two purposes: 1) It established that the vice president takes over upon a president’s permanent removal (through conviction, death, or resignation) or temporary removal due to a “disability.” 2) It empowered Congress to establish a further line of succession in case there is no vice president when the president is removed. It left two major gaps, however.

First, while addressing what happens when the presidency is left vacant, and authorizing Congress to address a dual president/vice president vacancy, it failed to address a vacancy of the vice president only. As a result of this omission, the position would remain vacant. Second, while anticipating the situation in which the president is disabled, and providing that the vice president temporarily takes over, Article I, Section 2, Clause 6 said nothing about how this would work. Who determines that the president suffers such a disability? Who determines that he has sufficiently recovered to resume the powers of the office?

It is not as if these questions didn’t occur to the framers. At the Constitutional Convention, Delaware delegate John Dickinson succinctly posed exactly the right questions about the disability clause: “What is the extent of the term ‘disability’ and who is to be the judge of it?”1 But no one had answers, and the delegates elected to let the matter slide.

The oversight with respect to a vice presidential vacancy may have stemmed from the sense that the office lacked importance. Its first occupant, John Adams, called the vice presidency “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.”2 The 32nd vice president, John Nance Garner, more colorfully declared the office “not worth a bucket of warm piss.”3

But the vice president is important, if only because he is a heartbeat away from the presidency. Or, as Adams put it with characteristic shrewdness and uncharacteristic brevity: “I am nothing but I may be everything.”4 With the “everything” in mind, it is strange to think that, throughout U.S. history, the vice presidency frequently stood vacant—on 17 occasions, there was no vice president for an extended period of time. We saw, in connection with Andrew Johnson, the absence of a vice president as problematic: The president pro tempore of the Senate, Ben Wade, Johnson’s political enemy, stood next in line (by virtue of the succession statute passed in 1792) if Johnson were removed. Related problems surfaced throughout U.S. history. There have been many periods of vice presidential vacancy during which the president pro tempore, as well as the Speaker of the House (who was next in line), belonged to a different party than the president.

Johnson’s impeachment dramatized these problems, but he was by no means the first president to be without a vice president. James Madison saw two of his vice presidents die in office and served without an underling for three years. There was a period in Madison’s second term when he fell ill and speculation arose that he might die, to be succeeded by the elderly and frail Vice President Elbridge Gerry. If Gerry then passed away (which in fact he did the following year), the presidency could not have passed to the president pro tempore of the Senate because the latter position was vacant after Madison appointed William Crawford Minister to France. Next in line was House Speaker Henry Clay, who was reviled by many allies of Madison.

Since Madison survived, so did this constitutional infirmity. A few decades later, John C. Calhoun resigned the vice presidency in December 1832 to become a U.S. senator, and President Andrew Jackson finished his term without a vice president. Two decades after that, when John Tyler became president upon the death of William Henry Harrison just 40 days into his term, the vice presidency remained vacant for four years. Ditto from July 1850, when Millard Fillmore assumed the presidency upon the death of Zachary Taylor, until March 1853. Just one month into the term of Fillmore’s successor, Franklin Pierce, Vice President William King passed away, leaving Pierce with no vice president for virtually his entire term.

So, too, the deaths of the vice president left the office vacant for various stretches during the Hayes, Cleveland, McKinley, and Taft administrations. Three other presidents—Coolidge, Truman, and Lyndon Johnson—assumed the office upon the death of their successor, and thus had no vice president of their own until the next election.

From George Washington’s presidency through Lyndon Johnson’s, there were vice presidential vacancies totaling 38 years—roughly 20 percent of U.S. history up to that point. Fortunately, though, a double vacancy never occurred: No president ever died (or otherwise left office) during the period without a vice president,* despite a few close calls. John Tyler was aboard a warship when an artillery gun exploded, killing six people, including the secretary of state and secretary of the navy. Franklin Pierce suffered a severe bout of malaria that briefly threatened his life.

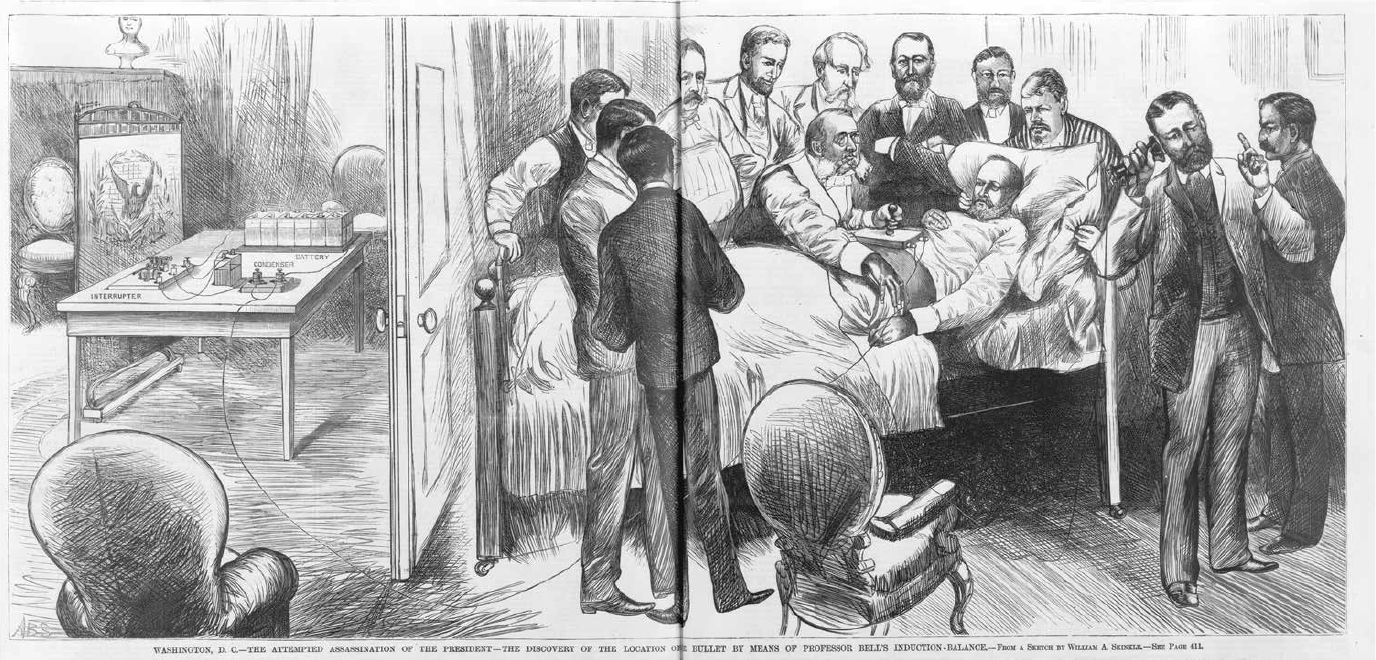

If the absence of a vice president was a problem from the beginning, the other constitutional gap, an incapacitated president, did not surface for almost a century. (A partial exception was James Madison’s illness, a three-week period during which he cancelled meetings and did little but recuperate.) In 1881, however, the constitutional lacuna loomed large. On July 2, President James Garfield was struck by an assassin’s bullet at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington D.C., and clung to life for almost three months before succumbing. Despite intermittent signs of recovery, Garfield was in no condition to work, even apart from his frequent bouts of hallucination. He conducted a single piece of presidential business—signing an extradition paper—during this period before passing away on September 19. During the attempted recovery he was a good distance from the White House, bed-ridden in a home on the New Jersey shore.

Throughout this period of Garfield’s incapacity, the United States effectively had no president. Vice President Chester Arthur did immediately come to Washington after Garfield’s shooting; he stayed there for 10 days and held meetings with the cabinet. But when Garfield’s condition stabilized, Arthur returned home to New York, where he remained in relative seclusion and conducted no official business. He neither visited nor communicated with the president.

Garfield’s cabinet members attended to their business, keeping the government going, but obviously lacked the power to take many official actions, including conducting foreign policy. Concerned by this situation, in August Secretary of State James Blaine drafted a memorandum arguing that Arthur should come to the capital and assume the powers of the presidency. Only a few cabinet members agreed. Arthur himself, who was from the opposite wing of the Republican Party as Garfield, feared being accused of usurpation. It was an understandable concern, given that Garfield’s assassin had shouted, “Arthur is president now!”

Garfield’s death mooted the issue, and during Arthur’s presidency the nation again went without a vice president. Three months into his administration, Arthur sent a message to Congress raising the relevant issues concerning an incapacitated president:

Is the inability [referred to in the Constitution] limited in its nature to long-continued intellectual capacity or has it a broader import? What must be its extent and duration? How must its existence be established? Has the President whose inability is the subject of inquiry any voice in determining whether or not it exists, or is the decision of that momentous and delicate question confided to the Vice-President, or is it contemplated by the Constitution that Congress should provide by law precisely what constitutes inability and how and by what tribunal or authority it should be ascertained? If the inability proves to be temporary in its nature, and during its continuance the Vice President lawfully exercises the functions of the Executive, by what tenure does he hold his office? Does he continue as President for the remainder of the four years’ term? Or would the elected President, if his inability should cease in the interval, be empowered to resume his office?5

Arthur’s interest in these questions stemmed not only from his experience as vice president during Garfield’s incapacitation, but also from his own health issues: He suffered from a usually fatal kidney condition. However, despite occasional bouts of nausea and depression, Arthur served out his term in passable health and the issue of an incapacitated president receded.

Just eight years after Arthur left office, in May 1893, President Grover Cleveland was diagnosed with a malignant tumor in his mouth. During what was presented to the public as a vacation cruise on a yacht, Cleveland in fact had his tumor removed by a team of surgeons in a tiny, poorly lit room. Only one cabinet member even knew about the surgery. Vice President Adlai Stevenson was also kept in the dark. In July, Cleveland took another cruise for the purpose of follow-up surgery. This time, though, word leaked out, and in August a Philadelphia newspaper reported Cleveland’s medical operations. Most of the press denounced the story as fake news.

The incapacitation problem next surfaced on October 2, 1919, when Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke that left him largely disabled for the last 16 months of his term. His condition was kept secret from the press and public. Secretary of State Robert Lansing privately suggested that Vice President Thomas Marshall be called in to execute presidential powers, but the idea was vetoed by Wilson’s right-hand man, Joseph Tumulty. Lansing also raised the issue at a cabinet meeting, but received little support. His proposal went nowhere, and Marshall, who like Chester Arthur wished to avoid any suggestion that he usurped the president’s power, took no initiative. Tumulty and Wilson’s wife Edith effectively ran the country for the duration of Wilson’s term. Lansing did call periodic cabinet meetings until Wilson (who recovered somewhat and was sentient) fired him for overreaching in February 1920.

During and in the immediate aftermath of Wilson’s presidency, members of Congress introduced various pieces of legislation to deal with the incapacity problem, which would have given the Supreme Court, Congress, or the cabinet the power to declare a president disabled and temporarily replace him (with the vice president or someone else). The House Judiciary Committee considered these options but never reached a consensus. As was the case when James Blaine and Chester Arthur raised the issue in the wake of the Garfield shooting, the matter eventually faded without any action taken.

The issue again surfaced when Dwight D. Eisenhower suffered a heart attack on September 24, 1955, and doctors prescribed a month of complete rest. Vice President Nixon, Chief of Staff Sherman Adams, and the cabinet adopted a “committee system” which more or less maintained business as usual at the White House, and fortunately, no crisis arose requiring presidential action. Nixon later described the problematic situation: “Aside from the President, I was the only person in government elected by all the people; they had a right to expect leadership, if it were needed, rather than a vacuum. But any move on my part which could be interpreted, even incorrectly, as an attempt to usurp the powers of the presidency, would disrupt the Eisenhower team.”6

The problem resurfaced twice more during Eisenhower’s presidency. On June 9, 1956, he underwent relatively minor surgery to remove an obstruction of the small intestine. For two hours the president was anesthetized and unconscious. Eisenhower lamented that, for those two hours, the nation—a nuclear superpower engaged in a cold war with another nuclear superpower—lacked a commander-in-chief. He asked the Department of Justice to study the problem and recommend a solution, and asked his cabinet for their input in a meeting in February 1957. The cabinet kicked around various ways of handling a president’s incapacity, but reached no consensus. On November 25, 1957, Eisenhower suffered a stroke. Though he recovered quickly, the episode revived concern about the incapacitation problem.

Actually, even before Eisenhower’s heart attack in 1955, House Judiciary chairman Emanuel Cellar of New York asked the committee’s staff to study the presidential disability issue. The staff distributed to judges, academics, and public officials a questionnaire seeking views on all aspects of the question, including whether a constitutional amendment was needed. Respondents offered numerous takes on these questions but no consensus was reached.

In 1957, Attorney General Herbert Brownell proposed to the committee a constitutional amendment: The president could declare his own inability, or, if he was unable to, the vice president and a majority of the cabinet could do so. In either event, a written declaration by the president of his recovery would enable him to resume his authority.

Members of Congress raised potential problems with this approach. For example, what if the president stubbornly and prematurely declared his recovery? Brownell replied that impeachment would be available, but the answer was unsatisfying: Impeachment seemed reserved for cases of wrongdoing, not disability. Meanwhile, in a New York Times op-ed, former President Harry Truman offered a different solution—creation of an elite medical commission that would report to Congress, which by two-thirds vote of both houses could remove the president for the duration of his term.

After another Eisenhower illness in 1958, another subcommittee was formed and held hearings, this time under the auspices of the Senate Judiciary Committee. This subcommittee ended up approving a version of the plan proposed by Attorney General Brownell the previous year, but Congress would not pass it.

Meanwhile, an increasingly alarmed and sickly Eisenhower decided to take unilateral action. He released a letter to the public on March 3, 1958, explaining that he had given Nixon the authority to determine if and when he (Eisenhower) was disabled and he (Nixon) would need to take over. Eisenhower reserved for himself the right to determine when he had recovered sufficiently to reclaim the powers of the office. His successors Kennedy and Johnson informally maintained the same understanding with their vice presidents.

This solution made good sense but lacked the force of law. If the unofficial but de facto president gave orders, must anyone obey them? Not really. Would his signature on a bill make it law? No.

At least in retrospect, it is surprising that the dual problems of vice presidential vacancy and presidential incapacity went unsolved for so long. Irreversible momentum toward a solution was finally created by the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, who had a history of heart trouble, served the duration of Kennedy’s term without a vice president. The assassination not only reminded everyone of that recurring situation but also refocused attention on the problem of presidential incapacity. The next day, in the New York Times, James Reston observed that “for an all too brief hour today it was not clear again what would have happened if the young President, instead of being mortally wounded, had lingered for a long time between life and death, strong enough to survive but too weak to govern.”7

The new president himself shared the newspaper’s concerns. Just a month after he took the oath of office, Johnson wrote a letter to Speaker of the House John McCormack codifying an oral agreement the two apparently had reached in which, should Johnson become incapacitated, McCormack would resign as Speaker and become acting president. Johnson would resume the powers of the office upon his own determination that he was able to do so.

The problem of potential disability was again compounded by the absence of a vice president. Though Johnson designated McCormack as his temporary replacement-in-waiting, the Speaker was 72 years old and generally not regarded as presidential timber. Next in line, president pro tempore of the Senate Carl Hayden, was 86.

The problems of presidential disability and vice presidential vacancy again took center stage, and assorted constitutional amendments were proposed. The ensuing Senate hearings produced the usual disagreement about how to handle the incapacity situation, but there was an emerging consensus that provision must be made to fill vice presidential vacancies. Everyone felt there should be someone who sees himself and is seen by others as waiting in the wings in case the president dies or otherwise leaves office—ideally someone who, like the president, was elected by the entire country. In other words, the nation needs a vice president at all times: The frequent vacancies were intolerable.

Though nothing was done to fill Lyndon Johnson’s vice presidential vacancy, after his election with running mate Hubert Humphrey in 1964 the cause was again taken up. In his January 1965 State of the Union address, Johnson urged Congress to pass laws “to insure the necessary continuity of leadership should the President become disabled or die.”8 Senator Birch Bayh proposed a constitutional amendment shortly thereafter, and in a statement to Congress on January 28, Johnson endorsed it. The proposed amendment worked its way through each house of Congress, then a conference committee, and in July a final version was adopted and sent to the states, where three-fourths had to ratify it to make it part of the Constitution. On February 10, 1967, Minnesota and Nevada put the 25th Amendment to the Constitution over the top.

The amendment, whose seeds were planted by Eisenhower’s attorney general Brownell a decade earlier, simultaneously resolved the vice presidential vacancy and presidential incapacitation problems. (The amendment’s conformity to Brownell’s approach was no coincidence; he chaired an American Bar Association Committee that drafted an early blueprint of the amendment.) It easily fixed the frequently recurring problem of vice presidential vacancies by providing that “whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.”

It didn’t take long for this provision to pay dividends: Had it not been in place, there would have been no vice president during the impeachment proceedings against Richard Nixon, following Spiro Agnew’s resignation on October 10, 1973. The person next in line, Speaker of the House Carl Albert, was not considered—including by himself—prepared to become president. To make matters worse, he was a Democrat. Had Nixon not nominated and Congress not confirmed Gerald Ford as vice president, Republicans would have been less willing to proceed with impeachment and, later, push for Nixon’s resignation. The 25th Amendment thus paved the way for Nixon’s removal—and for stability in its aftermath, especially since Ford had been overwhelmingly confirmed as next in line, and since he, in turn, immediately nominated Nelson Rockefeller to be the new vice president. Rockefeller, too, was fairly quickly and easily confirmed.

As House Judiciary Chairman Peter Rodino said at the time, “It is unquestionable that without section 2 of the 25th Amendment, this nation might not have endured nearly so well the ordeal of its recent constitutional crisis.”9

Sections Three and Four addressed presidential incapacitation. Section Three stated that the vice president assumes the powers of the president whenever the president gives Congress a written declaration that he cannot discharge the powers and duties of the office. The president reclaims the responsibilities of the office through a similar declaration. This provision has been used successfully several times for short-term transfer of power when presidents have undergone general anesthesia for minor surgical procedures—in 1985 when President Reagan had polyps removed from his colon and in 2002 and 2007 when President Bush underwent colonoscopies.

Section Four addressed the situation in which the president is too incapacitated to write such a letter. In such a situation, the transfer of power to the vice president occurs when he and a majority of the president’s cabinet (“or of such other body as Congress may by law provide”) write to Congress declaring the president’s incapacity. Once again, the temporary transfer lasts until the president issues a written declaration reclaiming his powers, but this time with a wrinkle.

The drafters of the 25th Amendment anticipated the situation in which the vice president and Congress believe the president incapacitated whereas the president believes himself still up to the job. If the president disputes the claim of incapacity, or later claims to have regained capacity, the vice president and Congress have four days to express disagreement. Then Congress has three weeks to decide the issue, with the president keeping or reclaiming power unless two-thirds of both houses agree that he is in fact disabled.

Two points about the 25th Amendment warrant emphasis. First, it envisions that reasonable disputes about the president’s capacity will be resolved in his favor. This is also somewhat true with respect to removal via the impeachment process, insofar as two-thirds of the Senate is required to convict an impeached president. However, only a bare majority of the House is needed to impeach the president. When it comes to a disputed removal via the 25th amendment, two-thirds of both houses are required. Clearly, the drafters of the 25th Amendment did not wish for the vice president and the president’s cabinet to remove the president through a backdoor that circumvented Congress. Instead, they made it more difficult to use the 25th Amendment than impeachment.

Second, the 25th Amendment covers situations involving mental as well as physical inability. The drafters had foremost in mind a situation such as the stroke that befell Woodrow Wilson or the bullets that struck John F. Kennedy—that is, a physically disabled president. But they borrowed Article I, Section 2’s broad language (“unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office”), which covers a wider range of situations. There could be cases, such as the president being perpetually intoxicated or slipping into dementia or mental illness, that require his removal without him having committed a grievous offense. The 25th Amendment speaks to that situation.

This straightforward interpretation of the language is buttressed by the history of the amendment’s adoption. Its architect, Senator Bayh, and other senators, made clear that mental disabilities were also within its scope, that they had in mind any inability to perform the constitutional duties of the office.

The issue received renewed attention when the New York Times published Ross Douthat’s column “The 25th Amendment Solution for Removing Trump” on May 16, 2017, suggesting that the 25th Amendment, not impeachment, offers the best vehicle for dealing with concerns about President Trump’s unfitness. Douthat began by making a general observation of attributes that any president needs: “a reasonable level of intellectual curiosity, a certain seriousness of purpose, a basic level of managerial competence, a decent attention span, a functional moral compass, a measure of restraint and self-control.” Douthat suggested that deficiency in any of these areas could render a president unfit, then applied his analysis to the current president, beginning with the assertion that President Trump is childish.

It is a child who blurts out classified information in order to impress distinguished visitors. It is a child who asks the head of the F.B.I. why the rules cannot be suspended for his friend and ally. It is a child who does not understand the obvious consequences of his more vindictive actions—like firing the very same man whom you had asked to potentially obstruct justice on your say-so.

A child cannot be president. I love my children; they cannot have the nuclear codes. But a child also cannot really commit “high crimes and misdemeanors” in any usual meaning of the term. . . .

Which is not an argument for allowing him to occupy that office. It is an argument, instead, for using a constitutional mechanism more appropriate to this strange situation than impeachment: the 25th Amendment to the Constitution. . . .

The Trump situation is not exactly the sort that the amendment’s Cold War–era designers were envisioning. He has not endured an assassination attempt or suffered a stroke or fallen prey to Alzheimer’s. But his incapacity to really govern, to truly execute the serious duties that fall to him to carry out, is nevertheless testified to daily—not by his enemies or external critics, but by precisely the men and women whom the Constitution asks to stand in judgment on him, the men and women who serve around him in the White House and the cabinet.

Read the things that these people, members of his inner circle, his personally selected appointees, say daily through anonymous quotations to the press. (And I assure you they say worse off the record.) They have no respect for him, indeed they seem to palpitate with contempt for him, and to regard their mission as equivalent to being stewards for a syphilitic emperor.

. . .

This will not get better. It could easily get worse. And as hard and controversial as a 25th Amendment remedy would be, there are ways in which Trump’s removal today should be less painful for conservatives than abandoning him in the campaign would have been—since Hillary Clinton will not be retroactively elected if Trump is removed, nor will Neil Gorsuch be unseated. . . .

Meanwhile, from the perspective of the Republican leadership’s duty to their country, and indeed to the world that our imperium bestrides, leaving a man this witless and unmastered in an office with these powers and responsibilities is an act of gross negligence, which no objective on the near-term political horizon seems remotely significant enough to justify.10

Unsurprisingly, Douthat’s column met with major resistance, and not just from supporters of the president. Rather, many people thought Douthat mischaracterized the role of the 25th Amendment, which cannot be brought into play to remove a president who is wholly sentient and whose capacities are no different from when he was elected.

But while the 25th Amendment may indeed be unrealistic under such circumstances, Douthat made several important points. First, the president’s incapacity may not manifest in high crimes and misdemeanors. Second, a president may not be up to the job for reasons unrelated to a stroke or other physical infirmity. Third, the president’s unfitness may be worse when it involves an ongoing condition than if he committed a particular crime. It may make him a frightening steward of the nation’s nuclear arsenal, where there is little room for error. For all of these reasons, if we find ourselves with such a president, the 25th Amendment does seem to be the most proper—indeed the only—vehicle for his removal.

It may seem inconceivable that a president’s own vice president and cabinet would remove him under any circumstance short of a major physical infirmity. After all, even when Presidents Garfield and Wilson were physically disabled, their vice presidents avoided filling the vacuum for fear of being tagged usurpers. However, that was before the 25th Amendment constitutionalized such “usurpation” to safeguard our national well-being. Yes, the vice president and cabinet will be reluctant to invoke the 25th Amendment absent physical disability, but that very fact legitimizes the amendment’s usage: Surely, if the president’s own cabinet asserted his or her inability, the circumstance would be so dire that the public would likely accept the judgment.

As with impeachment, only more so, the Constitution provides built-in safeguards, especially the requirement of support for removal by two-thirds of both houses if the president contests the initiative. This, too, would supply legitimacy, since it virtually guarantees that members of the president’s own party in Congress (along with a majority of his own cabinet) concur that he or she cannot be allowed to stay in power.

* The line of succession after the vice president was established by statute, beginning in 1792, and changed in 1886 and 1947. Currently, in the event of double vacancy the Speaker of the House becomes president, followed by the president pro tempore of the Senate, then the secretary of state and other cabinet heads.