INTRODUCTION

The idea of impeaching the 45th president surfaced during the 2016 presidential election before we even knew who that president was going to be. Opponents of Hillary Clinton made no bones about their desire to push impeachment should she win, based on her use of a private e-mail server when she was secretary of state. Similarly, opponents of Donald Trump maintained that his extensive personal business holdings disqualified him from faithfully serving in the public interest as mandated by the presidential oath of office. Calls for Trump’s impeachment on this and other bases began almost before he had completed his inaugural address. His impeachment became a more realistic prospect a few months later with the appointment of special counsel to investigate possible criminal activities perpetrated by the Trump campaign.

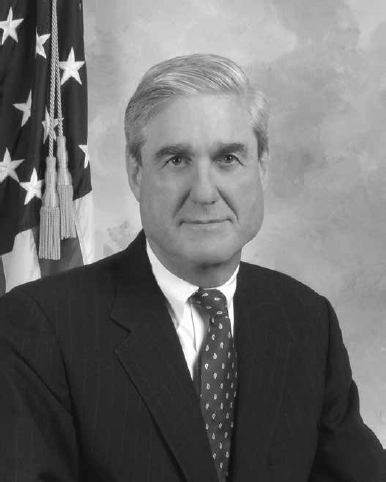

Throughout 2017, as Special Counsel Robert Mueller indicted several high-ranking officials in the Trump campaign and transition, commentators warned that the nation was headed for constitutional crisis. Debates broke out that went to the heart of U.S. democracy. What would happen if President Trump pardoned all those indicted? What if Trump attempted to pardon himself? What if he fired the special counsel before the latter completed his investigation? What was to be made of the claim by President Trump’s personal attorney, John Dowd, that “the president cannot obstruct justice because he is the chief law enforcement officer under [the Constitution]?”1 Critics responded that Dowd’s view puts the president “above the law” and thus contradicts a fundamental premise of the U.S. Constitution. Who was right?

Special Counsel for the U.S. Department of Justice Robert S. Mueller III.

Such questions, once fodder for law school exams and scholarly musings, have immediate relevance for our republic today. Fortunately, in addressing these questions, we do not write on a blank slate. The philosopher George Santayana famously observed that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. The more optimistic version is that, by learning from history, we can shape a better future. We must, therefore, revisit the scope, purpose, and history of presidential impeachment.

This book looks in depth at the impeachment sagas surrounding Andrew Johnson in 1868, Richard Nixon in 1974, and Bill Clinton in 1998, in order to draw lessons for future impeachments. We then apply those lessons to the circumstances surrounding Donald Trump, mindful that we face a constantly evolving situation. First, though, we need to place impeachment within a broader context.

The genius of the U.S. constitutional design lies largely in the numerous interlocking clauses that protect against the tyranny that can result when any person or group obtains too much power. Such protection starts with the division of government into two separate spheres of authority, federal and state, and the division of the former into three separate branches with specific responsibilities.

But the founders knew that even this careful division of power would not establish sufficient protection. Congress only makes laws, but what if it passes laws that suspend elections or instruct the courts how to decide cases? The president has executive power only, but what if he uses such power to harass or intimidate the other branches? The courts only decide cases, but what if they wantonly strike down Congress’s laws and the president’s executive actions? Because limiting the authority of the three branches might not suffice, the founders also gave each branch means of keeping the others from overstepping.

The greatest risk of tyranny comes from the executive branch, in part because the president is a single person. Members of Congress and the Supreme Court cannot accomplish anything unless they persuade a majority of their colleagues to go along. In addition, the president’s authority includes command over law enforcement and the military. For these reasons, maintaining restraints on presidential power is crucial.

Preventing tyranny preoccupied the nation’s founders in part because of oppression by the British monarchy. King George III mistreated not only the colonists, but also his own people. One goal of the Constitutional Convention was to prevent monarchy by another name. In fact, some delegates opposed making one person responsible for executing the nation’s laws. While the Convention eventually decided in favor of a one-person executive, it adopted a series of provisions designed to make the president a temporary public servant, accountable to the laws of the land.

Perhaps most significantly, the president would serve only a four-year term, requiring periodic approval of the voters if he or she wished to remain in office. But recognizing that great damage can be done in four years, the founders also provided a mechanism for quicker replacement of the president if necessary. Specifically, the House of Representatives could “impeach” the president, an accusation of wrongdoing that would initiate a trial in the Senate. The Senate, in turn, could by two-thirds vote convict the president, which would automatically result in removal from office. (Congress can impeach and remove all federal officers, not just the president, but presidential impeachment was the framers’ chief concern.)

Thus, the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the ultimate check on presidential power. At the Constitutional Convention, Virginia delegate George Mason captured the significance of this tool with a pair of rhetorical questions: “Shall any man be above justice? Above all, shall that man be above it, who can commit the most extensive injustice?”2 Alexander Hamilton directly tied the impeachment remedy to the goal of avoiding monarchy: “By making the executive subject to impeachment, the term monarchy cannot apply.”3 A king, after all, could not be impeached.

We should not take the impeachment tool for granted. While not unique to the United States, it is far from universal. When Richard Nixon resigned from office in 1974 under threat of imminent impeachment, many foreign leaders were bewildered. They assumed throughout the Watergate affair that, if he had to, Nixon could use his vast power to secure his position. In many countries, it is difficult if not impossible to remove a leader short of an insurrection or coup.

England invaded the United States and burned down the White House in 1814, but we have never experienced an insurrection or coup against a president. Instead, when the executive is believed to have abused power, we resort to impeachment—a pillar of our democracy and a peaceful means of protecting popular sovereignty. Even the president, this uniquely powerful and privileged person who commands the military and lives in luxury at the public expense, can be brought to heel. Nixon’s downfall, while posing a national crisis, affirmed a transcendent principle. The People exiled from power a man who had won a 49-state electoral landslide less than two years earlier. The notion that no person is above the law, which in ordinary times sounds like a utopian ideal, suddenly seemed very real.

But like any potent tool, impeachment is dangerous if misused. It can be used to subvert the ballot box and to bludgeon a president disliked by Congress. Nixon’s resignation was a victory not for a particular party or ideology, but rather for the American people and our institutions. In contrast, many historians view the two actual presidential impeachments, Andrew Johnson’s in 1868 and Bill Clinton’s in 1998, as partisan disasters in which the abuse of power came less from the impeached president than from his impeachers.

If impeachment can showcase the country at its best or worst, what separates the two? History offers guidance. In the pages ahead we revisit and draw lessons from the three major presidential impeachment episodes. We also address the other means of removing an unfit president: the 25th Amendment, which provides for temporarily removing a president who is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” We begin, though, by seeking to learn from the founders.