The Northern Beaches area of Sydney is an idyllic part of the world. Golden sands stretch for miles alongside national parks teeming with wildlife. The Pacific Ocean is on one side, beautiful bays looking into the city of Sydney on the other, making it possible to go for a swim or a surf in the morning before hopping on the ferry to work. But while this vision is a reality for many, for some of its residents it is a distant dream. Or at least that’s how it felt for Brad, who dropped out of school when he was sixteen and ended up in a series of jobs that paid the bills for a while but offered nothing in the way of long-term prospects. He spent two years moving through a series of short-term jobs. He worked in a DVD store, spent time as an assistant in a surf shop and had a series of bar and waiting jobs in the cafes and restaurants that line the most popular beachfronts.

It was waiting tables that lit something of a fire in Brad. He became interested in the food he was serving to customers; the flavour of the dishes, the aromas they gave off. He became especially interested in meat – in the grilled steaks, the cuts of lamb and pork chops he’d regularly serve up to satisfied customers. So, by the time he was eighteen, he decided that his next role wasn’t going to be another short-term job. He was going to pursue his passion, even if it meant starting again and taking a cut in wages.

The trouble for Brad was that he had no idea where to start. Then, after several weeks of soul-searching, he noticed a sign in a local butcher’s shop advertising for a new apprentice. Glen, the owner of the shop, was at his wits’ end after the last two apprentices had walked away only a few months into the four-year programme. This time, Glen had resolved, he was going to do things differently, so when Brad asked about the opening, Glen decided to conduct the opposite of a hard sell. He lay bare what being a butcher’s apprentice was going to be like. There would be early mornings, long hours and days and days of menial tasks – chopping up endless cuts of the cheapest meats, and lots of sweeping and cleaning. To cap it all, after four years he’d still be bottom of the butchers’ hierarchy. Glen believed that many young people like Brad had unrealistic expectations about what their apprenticeship was likely to entail, which helps to explain why 40 per cent of apprentices do not complete their course, and almost half of these drop-outs occur in the first year of the four-year apprenticeship.

Glen wanted to make it clear to Brad, then, that it was going to be a hard graft from day one. However, once he realized that Brad was serious, and had begun to recognize his genuine passion for meat, Glen’s tone began to change. He explained that the hours spent practising his meat cuts would stand him in good stead in the long term, and that he would be able to move slowly up from the lower-quality meats to the prime steaks. Glen also emphasized that, if Brad stuck at it and gave it his all, he would teach him everything that he knew and would help him to become a qualified butcher. He would give him time and space to develop his skills, to reflect on what he was learning and to think about the areas that he was most interested in learning even more about. Glen’s words had a strange effect on Brad. The years spent moving from one dead-end job to another had enabled him to understand better why it was worth putting in the hours for something that you have a passion for. So when Glen offered Brad the apprenticeship, he was determined to make it work.

Brad set himself a long-term, stretching goal, well aware that it was going to be tough. Over the years he spent hour after hour honing his skills, by chopping meat, preparing sausages and joints, and cleaning floors and fridges. But he found that the focused and effortful practice began to pay off, and he felt all the better for it. With time, Glen gave him space to try new things and even to test his own ideas and recipes in the area he enjoyed the most, which was preparing the shop’s cured meats.

When Brad spoke to Rory and Edwina from the New South Wales government’s own Behavioural Insights Unit, he explained that it felt as though all the hard graft was starting to pay off, and that this had encouraged him to set his sights even higher than they had been before. The lessons to Brad seemed clear. If you want to stick at a long-term goal, you have to be prepared to put in the hours; to undertake effortful practice; and to be prepared to learn from your successes and failures along the way.

The previous chapters have all focused on the tools and techniques we can put in place to help achieve our goals. This chapter is a bit different. It is about how we can make sure that we draw on these tools to help us stay with a long-term goal, particularly one that requires us to keep learning over time. The three golden rules to sticking at a goal are:

Practice with focus and effort. If your goal requires you to improve your performance over time, you should remember that the quality of practice is as important as the amount of time you spend doing it.

Practice with focus and effort. If your goal requires you to improve your performance over time, you should remember that the quality of practice is as important as the amount of time you spend doing it.

Test and learn. Once you’ve broken your goal down into discrete steps, you can improve your performance through experimentation – by testing the small changes, to see what works and what doesn’t.

Test and learn. Once you’ve broken your goal down into discrete steps, you can improve your performance through experimentation – by testing the small changes, to see what works and what doesn’t.

Reflect and celebrate success. Take some time to reflect on what has worked well (and not so well), and make sure you celebrate what you have achieved before moving on to the next goal.

Reflect and celebrate success. Take some time to reflect on what has worked well (and not so well), and make sure you celebrate what you have achieved before moving on to the next goal.

Rule 1: Practice with focus and effort

It is the final of the 2006 National Spelling Bee in America. Almost three hundred competitors, each of them a champion speller in their own right, has been eliminated after round-upon-round of increasingly difficult words. The pressure on the last couple of young contestants to perform in the contest, which is broadcast live on primetime American television, was immense. Up steps Finola Hackett, a fourteen-year-old Canadian who is asked to spell the word weltschmerz, a term used to describe a kind of depression brought about by comparing the world as it really is with an ideal state. So it was perhaps somewhat ironic that, after nineteen rounds of flawless spelling, it was this one that let Finola down. Up steps Katharine Close, a thirteen-year-old from New Jersey, who is trying to win the Spelling Bee at her fifth attempt. She is given the word Ursprache, meaning a hypothetical ‘parent’ language – and spells it correctly. Katharine is understandably delighted and steps up to collect her enormous, golden trophy and to be interviewed in a manner more befitting of a superstar footballer than a teenage wordsmith. ‘I couldn’t believe it,’ she said. ‘I knew [that] I knew how to spell the word and I was just in shock.’ Many of the people watching the Spelling Bee that evening were also in shock at the abilities of these young people, who seemed capable of spelling words that most people twice or three times their age had not even heard of. Most of us would be forgiven for coming to the conclusion that raw, superhuman talent was behind Katharine’s victory. She was, in other words, a born genius.

But unlike most people, behavioural scientists interested in how people do extraordinary things do not make assumptions of this kind. One person who was particularly interested in Katharine’s victory was Angela Duckworth, a professor of psychology from the University of Pennsylvania. Duckworth was an appropriate person to be asking this question. She famously describes being told by her father during her childhood that she was ‘no genius’, and then, years later, of having the pleasant irony of being awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, also known as the ‘Genius Grant’, because it takes the form of a $625,000 no-strings-attached stipend paid to its recipients. Duckworth has spent her life trying to understand what drives success and goal achievement, and concludes that though talent does exist, it will only get you so far. What often sets apart normal people from those who go on to achieve great things is a special blend of passion and perseverance that she calls ‘grit’. Might this, she wondered, also help to explain the success of Katharine and her Spelling Bee peers? So she and a group of colleagues set out to find out what the qualities of those who succeeded in the Spelling Bee might be by making contact with all of the finalists, before the final round took place. She wanted to know how much they practised, whether those who practised more were also more successful, and whether the kind of practice that they did made any difference.

The results of these kind of studies help to challenge beliefs that some people just have raw, innate gifts for a sport, musical instrument or ability to spell words. What Angela and her colleagues found, perhaps unsurprisingly, is that the kids who practised more, went further in the competition. Angela already knew that this was likely to be the case. So her second question interested her more. She wanted to know whether the kind of practice the kids were undertaking helped to explain their success. The researchers had identified three broad categories of practice into which most of the learning undertaken by the kids could be categorized. The first category of practice was verbal leisure activities, like reading for pleasure or playing word games. The second was being quizzed by another person or a computer. And the third was the solitary study of word spellings and their origins. This third category was what interested Angela and her colleagues the most, because it met the definition of ‘deliberate practice’, which has been described as a regime of effortful activities designed to improve performance.1 Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Spelling Bee finalists identified deliberate practice as the least enjoyable, most effortful activity that they had undertaken, in contrast to the verbal leisure activities, which were considered to be fun and much less effortful. But when Angela ran the numbers, she found that those who engaged in deliberate practice were more likely to progress in the competition. In turn, it was those children who were most prepared to persevere with the less enjoyable, but more successful, spelling strategies, that were more likely to win.

In other words, if raw talent doesn’t guarantee success, neither does mindless practice. It is the quality, as well as the quantity of practice that matters (plus a bit of luck and the support of those around you). The reason it is important to make this point is that this view clashes with a hypothesis that was popularized in books like Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers. Such works typically examined a number of extreme examples of over-achievers and came to the conclusion that mastery of more or less any field was possible with 10,000 hours of practice. Gladwell took the argument from a (then) little-known paper, published in 1993 by Anders Ericsson (who collaborated with Angela Duckworth on her study), who had been studying violin students at the West Berlin Academy of Music and had discovered that the most accomplished of these students had put in an average of 10,000 hours of practice by the time they were twenty years old – significantly more than their peers. But this is where the argument starts to break down. Gladwell extrapolated this finding to almost every other field. The Beatles put in 10,000 hours of practice while playing the clubs of Hamburg in their early careers. Bill Gates spent approximately 10,000 hours honing his computer-programming skills before setting up one of the world’s most profitable companies.

The problem with the argument was that, as Anders Ericsson would later point out, it didn’t add up. For starters, the violin students, even after they had averaged 10,000 hours, were still only students. They had many years of practice ahead of them. It was also an average figure – so lots of the students had done well in excess of 10,000 hours, while others were far below that figure. And this isn’t even getting into the debate around whether more or less practice is required to master different fields. It is estimated, for example, that most international piano competitions are won by people who are over thirty years old, by which time most competitors will have racked up between 20,000 and 25,000 hours of solid practice. But Ericsson’s main bone of contention was not focused on how best to calculate averages. It was that Gladwell had focused primarily on the quantity, rather than the quality of the practice.2 Ericsson’s research focuses in particular on ‘deliberate practice’ that requires significant amounts of focused effort, the planning of specific activities, and the receipt of feedback along the way, which enables you to push yourself to the edge of your limits to the point where you are learning most.

This book isn’t about outliers. It is about how all of us can achieve our more everyday goals through a series of small changes. And most of us can probably think of something that we have done for a long period of our lives and which – at some point – we just stopped getting any better at it because we failed to stretch ourselves through deliberate practice. For example, Rory has played football for many years, and when he was at school and university he was considered to be a fairly decent player. Over the years, he estimates he might have spent between 4,000 and 5,000 hours either playing or training. But he is sadly resigned to the fact that he is not on his way to lifting the World Cup. This is because, while he has shown up to hundreds of training sessions at school, university and with his work teams, these have typically focused on some light fitness exercises, a few basic drills and then a practice game. Except in the early years, when he was still finding his feet, Rory never subsequently felt as though he was stretching himself and he was never forced to focus intently on those aspects of his game that needed the most attention – like his inability to pass or shoot accurately with his left foot, or his second-rate close control. Similarly, Owain estimates he has played around 2,000 to 3,000 hours of guitar to date and, in his late teens, became a moderately accomplished classical guitar player, driven largely by his weekly lessons. These forced him to hone skills through an approach that resembled deliberate practice. For example, he’d force himself to learn how to do a ‘tremolo’, which requires you to play a note repeatedly with your three plucking fingers at such high speed that you cannot pick out the single notes. It’s really tough at first, but if you spend time by yourself in between lessons practising, you can gradually pick up speed until you sound reasonably accomplished. But like Rory, Owain found that after the early years of practice, in which he felt as though he made a lot of progress, he started to play ‘for pleasure’, stopped having lessons and found that his playing skills plateaued. They’ve been regressing ever since.

So, we are all capable of improving our performance in relation to a goal. But to do so we need to recognize that it will take effort and focus over a period of time and, to really learn, we need to integrate our deliberate practice into the broader approach to thinking small. It starts with the goals you set yourself. To see improvement over time, you need to be prepared to set yourself a suitably stretching goal – one that will be a challenge to meet. This could be learning a new skill that you know will push you (a language or a new musical instrument), but it might equally mean recalibrating your expectations about what can be achieved. For example, alongside the changes we made in UK Job Centres discussed in the Introduction, we also reset expectations about what level of job-searching activities might be required (from three job searches a week, which was the previous minimum, to a stretch goal of over fifty searches per week). When you then start thinking about how you can break that goal down into its constituent parts, that’s the point at which you can think about the quality of the practice you undertake. For Spelling Bee champions, this might be a new category of words. For football players and musicians, it might be focusing on a specific skill. At work, it might be focusing on your ability to tell compelling narratives in presentations. In our Job Centre work, it meant focusing on the specific things that the individual job searchers could improve – for some it was maths and English skills, for others how to write an appropriate CV. And finally, none of these focused, effortful activities will get you very far if you don’t have a good feedback mechanism in place to enable you to learn from the practice that you’re undertaking. Are your football skills getting better? Can you spell new words? Are your presentation skills improving? Are you getting more invites to interviews?

While it is impossible for most of us to become Olympic champions, chess grandmasters, world-class spellers or master storytellers, it is possible for all of us to become better parents, managers, football players or musicians, for example. To improve our performance in relation to a long-term goal we need to set ourselves more stretching goals and then apply ourselves in a more focused way to the elements of that goal that will help us improve our performance over time. As with the rest of the insights in this book, it is the small changes you make that will add up to something bigger. But in this case, small doesn’t mean easy. It requires focus, dedication and effort that, over time, will start to pay off.

Rule 2: Test and learn

Every year around a million people join the NHS organ donor register. This might seem like a lot of people, but despite the huge numbers of registrants, each day three people die in the UK because there aren’t enough organs available. It was this knowledge that led the National Health Service to get in touch with the Behavioural Insights Team, to see if we could come up with any ideas that might encourage more people to join the organ donor register. Hugo Harper and Felicity Algate, who led the work, felt that there was one particularly ripe area in which we could test some new ideas. It was to change the way in which people are encouraged to sign up to the organ donor register when they renew their vehicle tax or register for a driving license. Millions of people use this website every year, so if we could make a small difference to the number of people who say ‘yes’ when they’re prompted to join the register, it could have a huge impact.

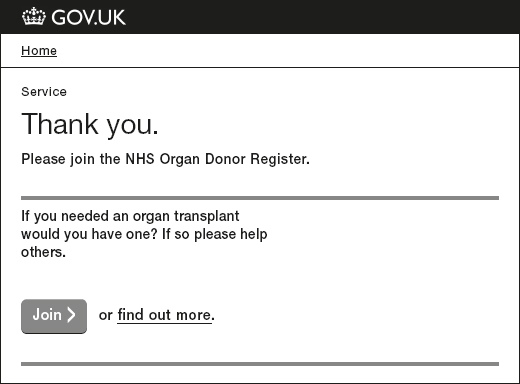

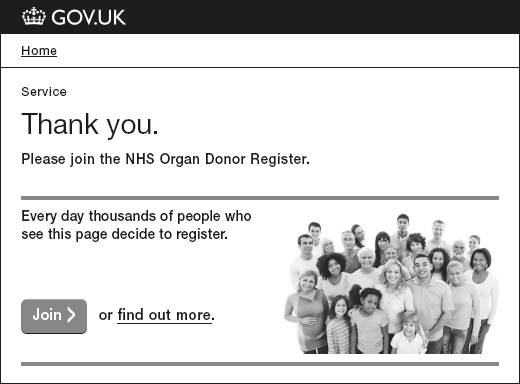

The idea was deceptively simple. We would test eight different ways of encouraging people to sign up, and then see which one worked best. Whichever ‘won’ would become the new message. You can have a go for yourself now if you want by considering which one of these two messages you see is likely to be most effective (see the screenshots here). Before you decide, a little heads up. One of these messages was the most effective of all, and helps to add around 96,000 extra people to the organ donor register every year compared with the standard message. The other is the only message that reduces the number of people who sign up. Before you read on to learn if you were right, have a think about why you think the one you selected might have worked best, and why the other might have failed.

We have shown these screenshots to thousands of people over the past few years at various conferences, seminars and workshops and the majority of those we ask go for one of these two messages – either the highest performing message, or the one that actually reduces the number of people who sign up. The highest performing message is the one that reads ‘If you needed an organ transplant would you have one? If so please help others.’ Engendering a sense of reciprocity, in line with the principles set out in the ‘Share’ chapter, seems to have a very powerful effect in this context. The one that decreases the sign-ups is the message with the picture of the group of people with the message telling you that ‘every day thousands of people who see this page decide to register’. It seems that the generic image of a group of people turns a serious message into a depersonalized piece of social marketing in the minds of those who see it. We know this because the exact same message without the image was also tested, and this increased sign-up rates. We find that when we tell people what the results are first and ask them to explain why one outperforms the other, it’s pretty easy to generate reasons. In hindsight, this is an easy job – there’s even a name for it: hindsight bias. But in the absence of this knowledge, it’s a much trickier task. You probably felt this yourself – not knowing the answer before being asked to predict which would outperform the other.

Over the past six years, the Behavioural Insights Team has pioneered the use of trials to help us understand which aspects of government policy are most effective. It is an approach which goes hand-in-hand with ‘chunking’ – breaking down your goal into smaller, discrete steps, so that each can be tested to see which changes are driving improvements in performance. Many of these experiments are referred to throughout this book and each involves asking a simple question: does it work? If I change the first line of a letter to people who’ve failed to pay their tax on time by telling them how many other people have paid, will it result in more people paying on time? (Answer: yes.) If I send people a message with an infrared picture attached of their home, showing how much energy they are wasting, and compare that to the same message without the infrared image, will it get more people to insulate their homes? (Answer: no, it decreases the number of people who do so, possibly because the image shows a glowing home, which some might interpret as lovely and cosy.)

If you think this experimental approach is limited to niche parts of the UK government, you’d be wrong. We saw in the ‘Set’ chapter how these same principles have been used by the British Olympic cycling team. They have also underpinned the success of Formula 1 teams seeking to make small improvements on their opponents; they are used by the Education Endowment Foundation to find out what works in school settings; and they even explain why tech companies like Google choose particular layouts and colour schemes. Google, like lots of other internet companies, is constantly testing small changes against existing practices to see which is best, and recently found that they were able to boost advertising revenue by some $200 million by making a small change to the shade of blue they used for the Google toolbar.3

What each of these tests had in common was the same recognition that comes to those who try and guess which of the organ donation messages might work best: an admission that they did not know what was going to work best. And that is, in many ways, the biggest barrier for all of us to overcome. As the Freakonomics authors Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt have argued, the hardest three words in the English language are not ‘I am sorry’ or ‘I love you’; they are: ‘I don’t know.’4 The problem is that, in almost all areas of work, life and play, we fail to accept that we don’t really know what works and what doesn’t. As the chief executive of the Behavioural Insights Team, David Halpern, has argued, it is the dirty secret of governments around the world that we do not know conclusively whether we are doing the right thing or not; whether a programme we have invested huge amounts of resources in – a new curriculum, employment support package, judicial sentence or so forth – is actually working.

It is only when we go and trial these programmes in a way that enables us to see what would have happened if we did nothing (by testing the new intervention against a control), that we can be certain that the programme is having the effect we expected it to have.5 The best illustrations of this are in those unfortunate instances where trials show that a programme we assumed was having a positive impact was actually having very little impact, or indeed a negative one. One such programme was called Scared Straight. It was developed in the US to deter young people from falling into a life of crime. The idea was simple. The kids would typically visit an adult prison, where they would hear about the reality of prison life from the inmates themselves.6 It might also include living the life of a prisoner for the day or receiving a deliberatively aggressive presentation by prisoners.7 Scared Straight was picked across the USA and copied by other justice systems around the world. Some early evaluations seemed to show that the programme was achieving great results and there was even a documentary made about the programme in 1978, which went on to win the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. The trouble was, the programme didn’t work. In fact, it was worse than that. A major evaluation of nine Scared Straight programmes found that they actually increased crime rates among those who’d made the prison visits. By 1997 a report to the US Congress, which reviewed 500 crime prevention evaluations, placed it on the ‘what does not work’ category. That’s why it’s so important to test new ideas before you introduce them at scale.

Now, we know that it’s not going to be possible for you to run hundreds of evaluations of different ways of becoming a better manager, losing weight, quitting smoking, improving your musical skills or learning a foreign language. But it does require you to admit to yourself that you do not always know what works best, demonstrating that it is worth trying out a variety of approaches to help you see which actions are best for helping you to achieve your desired outcomes. Following the framework set out in this book will make it easier to build this experimental approach into the way you set about achieving your goal. By breaking your goal down into a set of manageable steps and seeking feedback against a set of alternative approaches, you can start to identify the small changes you can make that add up to something bigger. For example, if your goal is to burn more calories every day for the next six months, you can try walking to work some days and seeing if that is more effective than getting the bus but always using the stairs to get to your sixth-floor office. On other days, you can do both. By using a Fitbit device or smart phone, you can monitor which of the two is most effective by measuring calories burned, and you can also judge which you are most able to build into your daily routine. If you are trying to save money, you can test a variety of different approaches and then monitor which of these results in you setting most aside. Some months you can try transferring money from your account into an account that cannot be raided (similar to the commitment account we saw in the ‘Commit’ chapter). During other months you can try setting aside a specified amount every time you don’t buy something that you would ordinarily have bought (that latte on the way to work). After several months, you can see which seems to be accumulating the most cash and then test variations of that particular method to see if you can improve it even more. Or as a new parent, you may want to experiment with different routines, times or methods for helping put your child to bed. The experimental approach can also be used to test some of your long-held assumptions in a fun way. When one of our colleagues declared that he thought organic carrots were vastly superior to ordinary carrots, Owain put it to the test with a blind taste challenge. No one could tell the difference. Over the years they subsequently tested orange juices (expensive = superior); wine (cheap is sometimes better) and even gin and tonic (some in-depth research in this area led us to believe the tonic drives the taste more than the gin!).

By testing and learning, we hope that you are able to adopt an approach which accepts you are not going to get it right first time, every time. But if you truly embrace the experimental method, you should see each of those failures as a little extra information that makes it more likely you will ultimately achieve your goal. That’s because you’ll have identified the things that you now know don’t work – like the Scared Straight programme – and you should therefore stop doing. Along the way you will no doubt also start identifying those things that seem to work best for you.

Rule 3: Reflect and celebrate success

Imagine that you are an undergraduate student. Alongside your studies, you have a couple of jobs to help pay for your textbooks and the occasional night out. For one of your jobs, you are a paid fundraiser for your university, which involves calling former alumni to persuade them to part with their cash. The former students are from across the academic spectrum – from music to business – and include people who have donated before, as well as those who haven’t. So you know that some calls are likely to be successful, while others will require a bit more effort. One day you are about to start a shift, when you are asked to gather round to hear a short talk from a graduate student of the university’s anthropology department. You listen intently as she explains the difference the money raised by you and your fellow fundraisers has made to her life. It was as a result of the calls made by you all, she explains, that she was able to travel and collect data for her research. And this research is helping to add to the body of knowledge of anthropology. You ask her questions about her research – where she travelled to, what it was focused on – and you are interested in how she used the money to support her endeavours. Money that you had helped raise. In total, the graduate student’s talk lasts only fifteen minutes, but you remember feeling a rush of warmth about it afterwards, as you pick up the phone for the thousandth time to see if you can collect more donations from alumni to the university’s coffers.

By now, you won’t be surprised to learn that this scene was part of an experiment, conducted by a friend of the Behavioural Insights Team, Adam Grant, who we encountered in the ‘Share’ chapter in relation to his work on people helping one another to succeed.8 Grant, then at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was interested in the fact that those working in public service – whether as a doctor, social worker or police officer – are not solely motivated by money, but also by the potential to make a difference to the communities that they serve. But Grant also realized that public service workers often never get to see the longer-term impact of their work. So his study was therefore designed to see what would happen to students’ fundraising efforts when they got a chance to reflect upon what they had helped to achieve by hearing a motivational talk from a graduate student who’d received funding as a result of their activities.

Grant created two groups of students. One group received the talk from the graduate student, the other group got nothing extra and went about their business as usual. Grant then measured how many financial pledges each person in each group collected on average in the month after the talk had taken place. The students who heard the talk showed a dramatic increase in the number of donations and amount pledged (more than double). By contrast, there was only a modest (and statistically insignificant) increase in the number of pledges and amount of money donated in the group who had not heard the talk. It seemed that being able to see and understand the positive benefits of the work that the fundraisers had been involved in provided a big boost in motivation for those undertaking what can sometimes feel like a challenging task.

We can all do more to reflect on the impact of the things we try to achieve in our work and our personal lives. It’s just that we do not routinely create opportunities to do so. As Grant’s study nicely shows, it helps to remind people about the true impact of their work on real people’s lives. You just need to think imaginatively about how you might go about doing this. For example, Elaine, Rory’s wife, is a palliative care doctor and one of the things she finds most rewarding about her job is when a family of the patient she has looked after writes her a thank you note. The problem across the health system generally is that by the time patients and families have returned from hospital, they lose touch with those who have helped them and cannot always find a way to engage with them further down the line. This was exactly what Owain and his wife Sophie experienced a couple of months after getting back from hospital following the birth of their first son. They wanted to send a card to the specific people who had supported them, but realized that they had no names of the individuals or means of contacting them directly beyond hanging out in the hospital wards. Very often all that is required in these instances is a simple mechanism that facilitates contact. A very nice example of how this can be done is to be found at a hospital in Sydney, Australia, which makes a point of writing to patients to ask them how they are getting on a month after they have left hospital. It provides a simple mechanism through which the patients are – usually – able to thank the staff, and to reflect on the care that they have received.

The idea of reflecting on success is a mantra that the Behavioural Insights Team has taken up in a number of different ways. For example, we have run interventions with school pupils to test different ways of encouraging them to go to university and found that just providing pupils or their parents with information – for example about the long-term benefits of attending university – are not effective. What does seem to work is pupils hearing about what it’s like to go to university from former pupils; such pupils inevitably dwelt on the lifestyle benefits as well as future career prospects. Similarly, at the Behavioural Insights Team’s start-the-week meeting, we always set aside time for what we call ‘Whoops of the Week’. These are opportunities for anyone to highlight something positive that someone else has done that helped them out or was particularly impressive. It’s a nice way of saying thanks to someone else, but also provides an opportunity for the whole team to reflect on the things that their colleagues have done that have really made a difference – often to the lives of others, rather than just their own. We want to encourage you to do the same by reflecting upon what you have achieved once you’ve reached your goal, especially if you’ve had an impact upon other people’s lives in getting there.

Of course, it is likely that some of the goals you set yourself will be too personal (climbing a mountain, losing some weight, or finding a new job) to impact significantly upon others. In these instances we would encourage you to take a slightly different strategy: take time out for reflection about what you have learnt along the way. You can do this during the period you spend achieving your goal, and after you have been successful (or not). This is a strand of research being pursued by another friend of the Behavioural Insights Team, Harvard researcher Francesca Gino and her colleagues, who have conducted a number of studies that explicitly encourage people to reflect on what they have learnt before rushing into the next set of challenges.9 The common finding in this research is that spending a small amount of time to reflect on what you have learnt pays dividends in the long term.

Gino shows this in numerous settings, including in a study conducted in the call centre of a global IT, consulting and outsourcing company based in India. The study focused on employees during their initial weeks of training. All the call centre trainees went through the same technical training, but with one crucial difference. One group spent the last fifteen minutes of each day reflecting on and writing about the lessons they had learnt that day, while the other group just kept working for another fifteen minutes. At the final training test at the end of one month, the trainees who reflected on a daily basis for fifteen minutes performed more than 20 per cent better, on average, than those in the control group. Francesca’s argument is that this kind of reflection is not a replacement for the kind of deliberate practice that we discussed earlier in this chapter. Far from it. Rather, it should be seen as a powerful complement to it. The researchers give the example of a cardiac surgeon engaged in effortful practice under the guidance of an instructor. Her aim is to become better at performing surgery as quickly as possible. But there is a limit to how much better she will become through practice alone. Setting aside a small amount of time to reflect on progress alongside the experiential learning will help her to improve more quickly. And you should do the same as you progress, or as you suffer setbacks along the way to achieving your goal. You should think about what you have learnt along the way, and use this to inform what you might try (and test) next. When you have ultimately achieved your goal, it would be beneficial to spend some time reflecting on your achievements before moving on to the next objective.

Before you reach your goal, however, we want you to think about putting in place one further small change that we think will ensure you look back on your achievements with pride and will help you to move on to even greater things in the future; think of ways of celebrating and capturing the moment when you ultimately achieve your objective. This isn’t just a nice thing to do; there’s also a good psychological reason for doing it, especially if your goal has been tough to achieve and has required you to endure suffering along the way. It relates to a little-known psychological construct known as the ‘peak-end rule’, in which we judge our experiences based on how they felt at their end and at their most intense points, rather than (as we might imagine) on the sum of pleasure or pain that the experience gave us.

Think about going to the dentist, for example. You might think that it would be better to get your teeth drilled as quickly as possible. But the research suggests that what is more important than the duration is how painful the worst moments were, and how the experience felt at the end. In one of the original studies to document the effect,10 Daniel Kahneman and his colleagues subjected trial participants to two very similar, unpleasant experiences, which Kahneman later described as a ‘mild form of torture’.11 The first involved having one hand immersed in cold water at 14°C for thirty seconds. The temperature was designed to be moderately painful, but not excruciatingly so, for the participants. If it sounds too warm to be painful, try it for yourself and see! Seven minutes later, they were subject to a second bout of mild torture. This time their other hand was kept in the water at 14°C for thirty seconds. But after the thirty seconds had elapsed, they had to keep their hand in for another thirty seconds while the temperature was very gradually raised to 15°C (still painful but surprisingly less so than a degree colder).12 When the participants were asked which they wanted to repeat, a significant majority chose the longer trial, implying that they preferred more pain overall. The experiment was designed to create a ‘conflict between the interests of the experiencing and the remembering selves’. The experience was clearly worse in the second form of torture. But experience and memory are different things and what Kahneman and his colleagues found was that our evaluations of experiences are dominated by the pleasures and discomforts we feel at the worst and final moments (hence the peak-end rule).

This means that when we are designing services, or the way we go about achieving our goals, we should think about how we can dampen the moments of unpleasantness; maximize the peaks of pleasure; and make sure that those final moments when we’re about to achieve our ultimate objective are as pleasurable as possible. Ensure, then, that you make the time to celebrate those final moments – by enjoying a glass of brandy at the top of the mountain or celebrating with your team after meeting your annual targets. Better still, try and capture that particular moment in some way, for example with a photograph of yourself crossing the finishing line or celebrating with your children on exam results day. It will help you to remember why you went through the months of effort to get there, as well as make you more resilient for your next challenge.

When we set out to achieve a goal, particularly a long-term goal that requires us to learn a new skill over time, it’s easy for us to charge ahead and to keep doing the same thing time and again. If we do so we will find that, even when we think we are practising, we won’t really be learning, we’ll be going through the motions. If we want to get better at a task over time, we need to think about how we are going to learn, so the best place to start is by thinking about how you are going to practise – by breaking your goal down and engaging yourself in effortful practice focused on making incremental improvements to how you go about tackling the task. If you do this, you’ll find that testing and trialling new ideas and new techniques will start to come naturally. You might not be able to conduct a large-scale randomized evaluation, but you will be able to learn from the feedback you get along the way, and by trying out small changes one at a time to see what effect they have on what you are trying to achieve. Finally, once you start making progress, or even if you have a few setbacks along the way, you need to set some time aside for yourself to reflect on what seems to be working and what is holding you back. If you can do all of these things, you’ll be able to start thinking about how you will celebrate when you finally achieve your goal. Then, of course, with a bit more reflection, you’ll be able to start thinking about what you might want to focus on next.

Practice with focus and effort. If your goal requires you to improve your performance over time, you should remember that the quality of practice is as important as the amount of time you spend doing it.

Practice with focus and effort. If your goal requires you to improve your performance over time, you should remember that the quality of practice is as important as the amount of time you spend doing it. Test and learn. Once you’ve broken your goal down into discrete steps, you can improve your performance through experimentation – by testing the small changes, to see what works and what doesn’t.

Test and learn. Once you’ve broken your goal down into discrete steps, you can improve your performance through experimentation – by testing the small changes, to see what works and what doesn’t. Reflect and celebrate success. Take some time to reflect on what has worked well (and not so well), and make sure you celebrate what you have achieved before moving on to the next goal.

Reflect and celebrate success. Take some time to reflect on what has worked well (and not so well), and make sure you celebrate what you have achieved before moving on to the next goal.