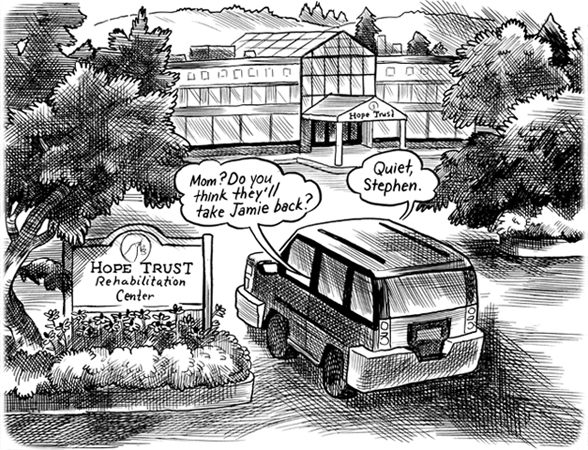

On Sunday the Smileys take me and Cool Girl upstate to visit the place I called home right before I moved to Smileyville.

The Hope Trust Children’s Rehabilitation Center.

What we patients all called the Hopeless Hotel.

It’s a special hospital for kids who’ve been in horrible accidents or have other kinds of super-serious medical conditions. It’s where I spent nearly a year recovering from the “severe trauma” of the car wreck. Hope Trust is totally supported by private money. I don’t think anyone hosts a telethon for it, but someone should. Maybe someday I will.

As we cruise the corridors, I see some of my old friends.

Like Carly. She has myotubular myopathy. It makes her muscles weak. A lot of kids who have it die before they’re one. Carly is eight. She’s what you might call a “fighter.”

She’s been checking in and out of Hope Trust her whole life. This is where she learned how to walk.

“You’ll get there, too, Jamie,” she says.

“Thanks.”

“Jamie?”

I can’t believe it. When I was at Hope Trust, Derek, who’s seventeen, couldn’t walk or talk. Heck, he could barely breathe. I remember he had so many tubes coming out of his body, some of the other kids called him Scuba Dude. Derek had been tossed out of a car, just like me. But while I landed on my butt, Derek landed on his head. As a result, he more or less sprained his brain and ended up with all sorts of neurological damage.

Now he’s walking with a cane and talking.

“Good to see you, man,” says Derek.

“You too.”

“Remember when I was, like, totally zonked out, and all you kids called me Scuba Dude?”

“Um, yeah?”

“I heard that, man. I heard every word.” He winks and smiles. We knock knuckles. “I’m late for PT.”

“En-joy.”

“Yeah, like that’s gonna happen….”

I remember PT. Physical therapy. It’s like gym class, but with a little medieval torture action tossed in.

Hey, I can’t complain. PT is what got me out of that bed and into this chair.

Okay. I guess we shouldn’t have called this place the Hopeless Hotel. But we all did. Mostly because we all thought we were hopeless cases until someone, usually a doctor or a nurse or a physical therapist, showed us we weren’t.

“I want you to see something,” I say to Cool Girl.

I take her to the hospital’s patient library. One whole section of the bookshelves is crammed with joke books.

“The doctors and nurses up here always said, ‘Laughter is the best medicine.’ So they’d bring me a couple of these books, and every day I’d read all I could about comedians and jokes and comedy sketches. Even when nobody thought I’d live, I kept reading joke books. And you know what?”

“I think all that laughing is what kept me alive.”