‘Who the Hell Are You?’: Aki Kaurismäki’s Cinema

Am I not that dissonant chord in the divine symphony, thanks to the insatiable irony that mauls and savages me? That spitfire irony is in my voice and all my blood is her black poison. I am the sinister glass in which she looks on herself.

I am the wound and the knife, I am the blow and the cheek, the limbs and the rack, the victim and the executioner.

Film critic Andrew Mann relates an anecdote about Aki Kaurismäki in his review of Mies vailla menneisyyttä (The Man Without a Past, 2002) for the LA Weekly. He tells of an incident that occurred at the Cannes International Film Festival in May 2002. It makes evident four stories that are ever present in Kaurismäki’s filmmaking and films, as well as in the discourse that comprises the filmmaker as a public figure – Kaurismäki the auteur, Kaurismäki the bohemian, Kaurismäki the nostalgic, and Kaurismäki the Finn.

When Kaurismäki took the stage at Cannes in May to receive his Grand Jury Prize, aka ‘second place’, he stopped first by jury president David Lynch and whispered something that put a look of alarm on the director’s face. The most consistent story is that Kaurismäki muttered, ‘As Hitchcock said, “Who the hell are you?”’ Many, apparently Kaurismäki included, thought he would be taking the Palme d’Or. (Mann 2003)

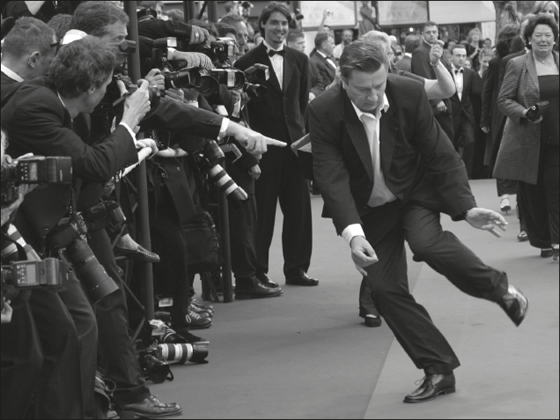

Apocryphal or not, this anecdote helps us see the four stories. While Kaurismäki is often thought to be a retiring and quiet personality (a stereotypical Finn), in this story he plays the brash auteur performing for the media at the most important and heavily covered film festival in the world (see Valck 2007). Yet such a performance contrasts with the bookish, nostalgic remark about Alfred Hitchcock, a key figure in the history of Hollywood cinema and auteurism. Taken from another angle, we may see the incident as a case of Kaurismäki playing the bohemian, true to the art, disdainful of convention and the bourgeois aspiration to sophistication. Another incident at Cannes in 2002 provides further material for the bohemian story: Kaurismäki spontaneously twisted down the red carpet and into the theatre at the gala screening of The Man Without a Past, embarrassing Finnish Minister of Culture Suvi Lindén and her entourage, who were accompanying the director. The next day, Lindén was quoted as saying that public drunkenness was not appropriate for a representative of Finland on the international stage (see Tainola 2002).2 Lindén rebuked Kaurismäki with an invocation of national culture. And yet Kaurismäki has long responded ambivalently to national culture, as he made evident in one interview:

This nation is so insecure that it’s just the greatest thing ever if some foreigner says something nice about Finland, or some Finn jumps or hops or bounces farther than anybody else. In that sense, when you have some success internationally, then that success is accepted here, too. Before that, my films were part of the freak show. (In Nestingen 2007)3

Kaurismäki twisting on the red carpet as he arrives at the Palais des festivals to attend the screening of The Man Without a Past during the 55th Cannes Film Festival, 22 May 2002 (photo: Anne-Christine Poujoulat/AFP/Getty Images)

The small nation sees Kaurismäki’s success as Finnish success, but Kaurismäki criticises such national enthusiasm. In the events at Cannes, paradoxes are clear when we analyse the anecdote in such terms as art and commerce, bohemianism and conservatism, nostalgia and scepticism, nation and cosmopolitanism. Tensions among these terms figure throughout Kaurismäki’s cinema, and indeed in the art film as a worldwide phenomenon.

Anecdotes like these play an indispensable role in any critical analysis of auteur cinema. Critical writing, biographical narratives, interviews, and anecdotes – authorship discourse – shape our expectations, responses to, and understanding of a filmmaker and his body of work. By approaching Kaurismäki through analysis of the discourse around the films and filmmaker, along with analysis of the films, this volume seeks to offer a rich and variegated perspective on the director’s films and career. No accessible English-language study of this noteworthy filmmaker’s work is available.4

This study’s methodology also seeks to extend revisionist authorship studies (see Koskinen 2002, 2009; Gerstner and Staiger 2003; Wexman 2003). Such studies have fruitfully built upon star studies’ theories and methods (see Dyer 1979; Gledhill 1991), and also on earlier poststructuralist studies of authorship, which approached authorship as a textual effect (see Wollen 1998 [1969]; Wood (2008 [1977]). In this theoretical context, when we look at Kaurismäki’s films at the same time as we turn his question to Lynch upon him – ‘Who the hell are you?’ – we are able to see the ways the films and authorship fit into a conjuncture defined by the rise of the film festival circuit, the globalisation of cinema and popular culture, the end of the Cold War, and the crisis of national welfare-state.

Before turning to the four stories, it is helpful to clarify what story means here. Story designates the organisation of events into a linked series. This correlates with narratologist Gerard Genette’s notion of narrative as ‘discourse which seeks to relate an event or a series of events’ (1980: 25). Story or narrative are relative and vague terms, because their meaning depends on the institutional contexts in which they function, as Marie-Laure Ryan has argued (2007). Story and narrative here – as well as the term scenario, which refers to a rough amalgamation of story material – presume the argument that a scholarly study of an authorship discourse can intervene in the authorship discourse to make evident recurrent patterns of commentary and interpretation that organise relevant events into meaningful combinations. These overlap with the films, in many cases, attributing meaning to the films and the authorship. In examining the archive of material compiled on Kaurismäki and his films at the Finnish Audio Visual Archives, as well as the abundant popular and critical literature, it is plain that narratives have formed and are in circulation about his life and work. These inflect assumptions, expectations, and responses to his films. Closer analysis of these narratives allows us to see Kaurismäki’s work in a more nuanced and plural way than we would if we were to bracket or ignore the authorship narratives, and focus only on the texts, understood as autonomous objects. In some contexts it certainly makes sense to adhere to a narrow, formalist definition of narrative as a cause-and-effect chain that is specific to cinematic or literary fiction, as some theorists of narrative do (see Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson 1985; Bordwell 1985; Bacon 2004). Yet the broader notion of narrative invoked here has provided enormous analytical value to cultural analysis. An example of such a narrative, highly relevant to Kaurismäki, is the national narrative, compellingly and critically theorised by Benedict Anderson (1991) and Homi Bhabha (1990).5 Narrow and broad notions of narrative and story can coexist in cultural analysis, and do not threaten to erode concepts of narrative. Let us turn then to the predominant stories in Aki Kaurismäki’s cinema, after which we will examine Kaurismäki’s career in a brief overview.

The Auteur

The Cannes anecdote is at its most obvious the story of a professional clash, a contest of auteurs. A jilted Kaurismäki snubs Lynch by asserting a superior knowledge of film history. The insult’s power comes from a cinephilic source, Kaurismäki’s knowledge of Hitchcock’s biography and films, but also his implicit familiarity with Lynch’s cinema. Lynch’s best known films – Blue Velvet (1986), Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001) – are arguably a postmodernist interpretation of Hitchcock’s auteur legacy. Hitchcock and Lynch share a fascination with psychoanalytically derived character psychology, which they use to create narrative suspense. To the auteur Lynch, Hitchcock’s aspirant heir, Kaurismäki growls, ‘you don’t know your Hitchcock’.

Such a remark stings because Kaurismäki claims a proprietary relationship to Hitchcock, a central figure in the politique des auteurs elaborated by Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, André Bazin, and other Cahiers du cinéma figures who argued that Hitchcock and some other prolific directors in the Hollywood studio system of the 1930s–50s fashioned their industrial products into personal expressions, meriting their recognition as the authors of their work. They also found auteurs in the European cinema, arguing that personal expression was also salient in the work of Jean Renoir, Fritz Lang, Roberto Rossellini, Ingmar Bergman, and others. As a consequence, auteur film since the politique des auteurs has meant both a canon of Hollywood and European films and bodies of work, as well as films displaying a definitive personal element. Kaurismäki asserts his own status as an auteur by reclaiming the Hollywood side, in Hitchcock, and the European side, in his learned self-assertion.

There is another dimension of this contestation of authorship in Mann’s account of Kaurismäki’s insult, however, which is the story of a Hollywood outsider affirming his status as an outsider by thumbing his nose at the American pretender. This dimension correlates with the tried-and-true account of auteurism as an aesthetic discourse of modernist art, in contrast to the culture industry in southern California. In this view, the European auteur’s cinephilia is understood in terms of modernism and the autonomous art object, which locate him in the high-cultural tradition of film art and distinguish him from the American auteur’s financial concerns, which are relegated to the low end of the cultural continuum. This dimension of the auteur story tacitly places Kaurismäki in such a modernist account of European auteur cinema. Yet at the same time, the haunting presence of Theodor Adorno’s culture industry argument and its many accompanying ghosts warn us of the paucity such binary accounts of auteurism can entail.

At the same time as Kaurismäki derides cinema as commerce, his films have embraced elements of the same commercial cinema, with their B-movie look, sentimental themes and expressions, and many allusions to popular music and culture – which resonate with a notion of personal taste in authorship like that popularised by Andrew Sarris in 1962. The ‘rock-n-roll’ music and motif are in every film. Ariel (1988), Leningrad Cowboys Go America (1989), Leningrad Cowboys Meet Moses (1994) and Kaurismäki’s music-video shorts are pastiches including plenty of Hollywood cliché. What is more, Kaurismäki has also proven himself a deft hand in the black arts of commerce, an owner not only of the rights to all his films, but also an operator of bars, restaurants, distribution companies and production companies, and also a sometime hotelier.

Kaurismäki’s cinema prods us to rethink the fundamental categories and binary oppositions that often structure popular and scholarly discussions of film authorship. In this way, his work is highly relevant to revisionist approaches to European cinema (see Elsaesser 2005; Hjort 2005; Hjort and Petrie 2008), the art film and auteur cinema (see Galt and Schoonover 2010), world cinema (see Ďurovičová and Newman 2009), and authorship (see Gerstner and Staiger 2003; Wexman 2003). At the same time, an introduction to his cinema requires an approach that makes evident the problems raised by his films. Chapter one of this volume takes such an approach by understanding his cinema as an engagement with ‘the archive’. It surveys Kaurismäki’s feature production, suggesting that an important theme in his body of work is a tactics of disruption, in which the films inject alterity into familiar systems to suggest the relevance of a divergent socio-political ethos. This survey also works to provide an introduction to Kaurismäki’s filmmaking, to place it in Finnish, European, and world-cinema contexts, as well as to sketch out some of the key interpretive frameworks within which it can be understood. In doing so the chapter also provides a background and set of references for the book.

The Bohemian

Another way to comprehend the remarks and twisting at Cannes is to understand them as part of a performance of bohemian identity. In this view, Kaurismäki’s clash with Lynch and twist down the red carpet look like efforts to distinguish the artist symbolically from the commercial festival and state agendas, which would seek to stage-manage Kaurismäki’s participation. The bohemian ridicules the commercial agendas that are part of the Cannes Festival and the state agendas that drive the attendance of Ministry of Culture officials. Kaurismäki has long presented himself as a bohemian filmmaker, and indeed his abiding interest in the theme is indicated as clearly as can be by his 1992 La vie de Bohème (The Bohemian Life), an adaptation of Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de bohème (The Bohemians of the Latin Quarter, 2004 [1852]), the basis for Puccini’s La Bohème. From the beginning of his career, Kaurismäki’s work has exhibited fascination with bohemian characters, whether the absurd author Ville Alfa in his screenplay for Valehtelija (The Liar, 1981), the unconventional artists of Calamari Union (1985), the criminals that surround Taisto in Ariel, Henri in I Hired a Contract Killer (1990), or the homeless characters in The Man Without a Past. What is more, Kaurismäki has often told the story of his entry into filmmaking and his subsequent career with bohemian tropes: kicked out of the army, homeless, scores of jobs, poor, devoted to his art, an underground filmmaker, micro-budgeted productions, and so on (see von Bagh 2006: 18).6

The term bohemianism has its roots in 1830’s Paris, in which the modern bohemians defined themselves against an arriviste bourgeoisie who embraced conservative aesthetic tastes (see Seigel 1986; Gluck 2005). Naming themselves after the Roma people, or ‘gypsies’, whose home was reputedly in Bohemia, the bohemians adopted outlandish historical dress, theatrical modes of protest, and heightened rhetoric to make clear their distinction from the bourgeoisie, of whom they were in many ways also a part and upon whom the artists and writers among them depended for their market.

Bohemian in this book draws on historical scholarship concerning bohemianism that came down from Parisian bohemia of the 1830s and 1840s, rather than the myth of the rebellious, hungry, greasy-haired artist who lives only for his art and wholly rejects the middle classes and their values. Scholars have defined bohemianism as an ambivalent, self-reflexive relationship of the bourgeoisie to itself. Describing nineteenth-century Paris, intellectual historian Jerrold Seigel writes: ‘Bohemia was not a realm outside bourgeois life but the expression of a conflict that arose at its very heart … It was the appropriation of marginal lifestyles among the young and not-so-young bourgeois, for the dramatisation of their ambivalence toward their social identities and destinies’ (1986: 11–12). Building on Seigel’s study, historian Mary Gluck has expanded a point about the cultural economics of bohemianism. Artists and intellectuals associated with bohemianism, emerged within post-revolutionary France, in which the patronage system had given way to an art market, making the constraints and excesses of both evident. Bohemian artists sought to link social, aesthetic, and economic contexts in dissent against the art market of what they saw as an insipid middle class, whose conservative aesthetic tastes and economic power they resented (see Gluck 2005). Yet these same bohemians’ literature, theatre, and style also addressed the middle class, and depended upon it economically. The ambivalence Seigel and Gluck identify derives from the conflicted requirements and attitudes towards the economy of an art market, which opened up the arts to the historically new figure of the autonomous artist, at the same time as that artist was compelled to distinguish his art in an art market in which many others offered their work.

Kaurismäki’s conflicted relationship to the middle class concerns both the art market and the political economy of the Finnish welfare state since the 1970s. Mainstream cinema is a commercial form, says Kaurismäki: ‘I love the old Hollywood, but the modern one is just a dead rattlesnake … I am like a dog always barking about Hollywood because with its power, it could make some really good films. Instead, sixty-year-old men are creating boy-scout level – and boring – violence; crass commercialisation is killing the cinema’ (in Cardullo 2006: 8). Today ‘there’s no sense in mixing up Hollywood and cinema. They’re two different things. Hollywood is business, the entertainment business’ (in Nestingen 2007). Consequently, Kaurismäki must distinguish his work in non-economic terms in a market dominated by ‘Global Hollywood’ (see Miller et al. 2001). The national audience offers no succour, for the Finnish welfare state since the 1980s has come to equate consumerism and citizenship; this discourse is part of a longer post-war history, in which the Finnish welfare state sought to define itself around a middle-class consensus, in which labour is productive, capital grows, and the nation enriches itself (see Alasuutari 1996). Kaurismäki’s symbolic distinction is in part evident in the absence of promulgators of this discourse: officials, the wealthy, and the middle classes in general figure little in the films. ‘They’re completely irrelevant; at most they’re caricatures who play the fool for a maximum of thirty seconds … they’re just such dull characters, all of them’ (in Nestingen 2007). And yet, just as Kaurismäki’s cinema must distinguish itself in the context of Global Hollywood (see Miller et al. 2001) and a national context, so too his films belong to the period of the mature European welfare state, defined around the same middle-class perspective that is part of the Finnish welfare state, many differences between political systems notwithstanding. The ambivalence identified in nineteenth-century bohemians by Seigel and Gluck finds an equivalent in Kaurismäki’s filmmaking and autobiography, as he has struggled to distinguish his films at the same time as he depends on the economy and perspectives he assails. It should be no surprise that bohemian ambivalence figures in the anecdotes at Cannes, and Kaurismäki’s career.

Bohemianism ties into a broader problem in auteur cinema, for it too occupies a position of symbolic opposition to the mainstream, yet is also historically, institutionally, and economically entangled with it. The relevance of Seigel and Gluck’s analysis of bohemianism is evident in the collection Global Art Cinema, which departs from the claim that art cinema as a discourse ‘has provided an essential model for audiences, filmmakers, and critics to imagine cinema outside Hollywood’ (Galt and Schoonover 2010: 3). Art cinema’s identity also depends on non-economic distinctions on the cultural market. Yet as the editors point out, ‘outside’ does not entail a neat division, but many criss-crossing connections and dependencies, precisely the conflicting identifications that animated the bohemians.

Chapter two further develops a historical contextualisation of bohemianism in Kaurismäki’s cinema, while at the same time critically tracing the use of the bohemianism trope in the Kaurismäki discourse. The analysis also serves to introduce the director’s biographical narrative by tracing bohemianism as a trope within it.

The Nostalgic

There is another commonsensical, albeit equally ambivalent, narrative evident in the Cannes anecdote: a nostalgia story. Given the critique of capitalist modernity we identified in sketching Kaurismäki’s bohemianism, it is easy to see why his films might also be understood as the construction of an idealised past. Kaurismäki’s citation of Hitchcock could be seen as an expression of longing for a lost cinematic past and its great auteurs such as Hitchcock, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Fritz Lang, Douglas Sirk, and others. This longing can easily be related to the disenchantment with post-classical Hollywood, which we have also observed. Furthermore, Kaurismäki’s films offer much evidence of nostalgia in their aesthetics, mise-en-scène, and characters’ attitudes. What we have in the insult, then, is also a putative declaration of nostalgia for a bygone film culture.

Commentators have told the nostalgia story about Kaurismäki’s cinema innumerable times. Some have emphasised an emotional register, interpreting the films in terms of subjective melancholia (see Toiviainen 2002). Others have read the nostalgia as a moral critique that attacks winner-takes-all neoliberalism, affirming instead a disinterested solidarity of the past (see Timonen 2005; von Bagh 2006). Some have seen it as an aesthetic critique, Kaurismäki’s films using old objects and visual styles to disrupt the digitally seamless design principles of capitalist modernity’s visual culture (see Koski 2006). Another view understands the nostalgia as an archiving project, which seeks to conserve the past against a planned obsolescence engineered in contemporary objects and attitudes (see Kyösola 2004b). These arguments share the claim that the object of the director’s nostalgia is the Finnish past.

In making Kaurismäki’s nostalgia national, these arguments make him one more competitor for cultural and political power in a national context. In a sense, they argue that Kaurismäki’s cinema is a ‘musealizing’ discourse (see Huyssen 2001), whose importance lies in its access to the reservoir of authority held in the national past.

To put it another way, the nostalgia story likens Kaurismäki and his films to the historical museum. The historical museum as an institution makes an objective claim to authority over the past as curators collect, organise, and display objects that embody the past. In their status as representative, these objects instruct us about the value of the past, as we view them in a cultural context of rapid, broad, and destructive change. The nostalgia story, in contrast, does not make an objective claim, but rather a subjective one. It is not a scholarly, curatorial agenda but Kaurismäki’s sensibility and critics’ interpretations that establish the relationship to the past. The nostalgia story ascribes to Kaurismäki a symbolic opposition to economic and political power, but it also involves an aspiration to cultural power.

Such arguments about Kaurismäki’s nostalgia presume that the nostalgic expression in the films, and in the discourse, is emblematic of a larger cultural whole, for which it stands. The aged jukebox playing rockabilly, the crooner singing Finnish tango: these stand for a national past. But can we take such expressions as typical or paradigmatic? That is to say, should we understand these examples in terms of types, with a universal set of referents? Or are they particular, contingent images with a circumscribed representational scope? This question is raised by the photographer and theorist Allan Sekula in an essay on images of the criminal in mid-nineteenth-century photographic archives; the archive is both ‘abstract paradigmatic entity and concrete institution’, writes Sekula (2006: 73). On the one hand, the archive rests on an assumption of equivalence, in which its holdings can be organised to recognise types; on the other, it is contingency, the collection of a vast number of particulars. For Kaurismäki’s nostalgia, then, we must ask, does the nostalgia that arguably figures in his films conform with the realist logic of type, or with the nominalist logic of contingency?

Chapter three examines the realist varieties of nostalgia adduced to Kaurismäki, while also arguing for the significance of contingency in the nostalgia in his films. This argument draws on the work of Michel de Certeau to suggest that contingency makes evident a tactic of disruptive resistance in Kaurismäki’s cinema and authorship discourse, which introduces an alternative socio-political ethos into the market rationality of late capitalism, as it is a context for Kaurismäki’s career.

The Finn

There is a final story we could tell about Cannes, as we witnessed in Minister Lindén’s remarks: Kaurismäki was drunk. Kaurismäki’s thirst often figures in the story of Kaurismäki the Finn. In this story, the man’s national sensibility not only explains incidents like the one Andrew Mann recounts, but his entire work as a filmmaker. But as with the stories about authorship, bohemianism, and nostalgia, the story of Kaurismäki’s Finnishness conceals ambivalence. For the Finnish story is often an essentialist account, which reduces complexity to the expression of a national stereotype. Chapter four shows that in contrast to such stereotypes, the narrative of nationality in fact involves competing accounts of nation at work within and beyond the borders of Finland. Kaurismäki’s cinema helps us see the ‘multi-local’ and ‘multinational’ composition of a national cinema, that is the geographically and transnationally dispersed participants and audiences involved in the production, distribution, and consumption of Kaurismäki’s cinema. Such parsing helps develop the term small-nation cinema.

Incommensurable constructions of Kaurismäki as a Finnish filmmaker make him many things to many people. This contested status is visible in a comment made by eminent filmmaker, producer, and jack-of-all-trades Jörn Donner, entitled ‘Kännissä Cannesissa’ (‘Sauced at Cannes’):

Aki Kaurismäki is a shy and reticent person, not unlike the characters in his films, quiet but also well spoken. However, liquor makes him wild, as it does some other Finns. Surprising and puzzling sentences start flying, which the lemmings of the international press then collect. (2003)

Donner’s story of Cannes is not actually an explanation of the insult to Lynch, but of Kaurismäki’s twist with Suvi Lindén, and the competing narratives of nation it involves. Donner’s story helps us see the logic of the Kaurismäki the Finn story, and as such is a strand of Mann’s anecdote. The logic here is one of revaluation, in which behaviour that is on the surface transgressive gets recoded as an expression of originality. For Donner, Kaurismäki’s surprising behaviour is not boorish, but actually of a piece with a set of cherished national traits: honesty, terse eloquence, silence, and thirst. Kaurismäki only appears boorish if we align ourselves with the stance taken by the Minster of Culture, that is, the perspective of a governing elite – a group to which Donner also happens to belong, having served in parliament and in political appointments. Donner implies that Lindén and the institutions she represents wish to stage-manage Kaurismäki for the international audience, rather than support his originality. In Donner’s account, Kaurismäki’s drinking and dancing are an expression of rebellious originality, the source of his brilliance.

In the Kaurismäki the Finn story, we once again see competing claims to authority. A state representative asserts a normative definition of national culture, while another commentator maintains that such a claim suppresses originality. Because figures like Lindén cannot recognise Kaurismäki’s art, Donner implies they deserve precisely the kind of critique and correction that Kaurismäki provides.

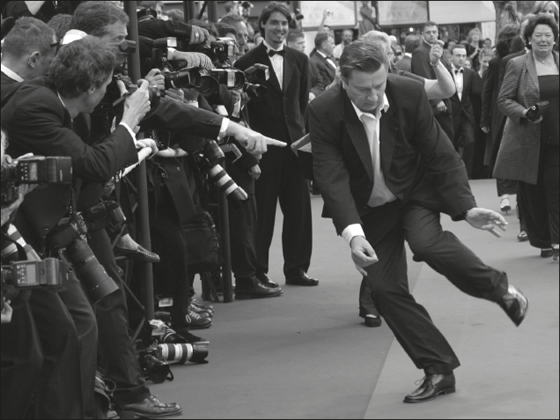

Kaurismäki and his entourage at the Cannes Film Festival, including Finnish Minster of Culture Suvi Lindén (second from the right), 22 May 2002 (photo: Pool Benainous/Duclos/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images)

The ambivalence arises from the transgressive performances that are required to make such claims to authority. Donner and Kaurismäki know very well that one of the obsessively repeated debates in the discourse of Finnish national identity has to do with alcohol. In making a case for Kaurismäki’s originality, Donner revalues qualities often deemed shameful and in need of amelioration. As the folklorist Satu Apo has shown, alcohol is seminal in Finnish history within a discourse of self-stigmatisation, in which elites have used drinking practices to criticise the masses for their many alleged lacks, thereby justifying elite agendas, institutions, and action concerned with national improvement (see Apo 2001). But many, mostly on the left like Donner and Kaurismäki, have revalued what elites construct as a low-status position defined by lack, attributing to it romantic vitality, energy, humour, and life force. The literary scholar Pirjo Lyytikäinen has called this the ‘transgression tradition’, evident from such canonical writers as Rosa Liksom to Hannu Salama to Väinö Linna to Aleksis Kivi, the last commonly regarded as the father of Finnish literature (see Lyytikäinen 2004). The transgression tradition’s claim to authority lies to some degree in contesting elites’ construction of the nation, while at the same time asserting a moral claim by casting itself as the righteous victim of these same elites.

Another way to contextualise the national dimensions of Kaurismäki’s cinema is to analyse it as an instance of small-nation cinema circulating in the realms of a transnational, world cinema. Small-nation cinema is a term elaborated by Mette Hjort (2005) and later in a collection of articles edited by Hjort and Duncan Petrie (2008). Hjort emphasises the way film production is enhanced and broadened by way of institutional innovation, creative leadership, ‘gift culture’, and other savvy collaboration. While such features figure in Kaurismäki’s cinema, it is not so much production as distribution that is a key feature. Kaurismäki has used the film festival to advance Finnish cinema as a small-nation cinema, not only through the construction of his own reputation at the taste-making festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, Toronto, and Venice, but also through his work and development of the Midnight Sun Festival, which he founded with his brother, Mika, their collaborator Peter von Bagh, and the municipality of Sodankylä in the far north of Finland. Through invitations to many prominent figures in auteur cinema, Kaurismäki has created a consistent cultural input into his own cinema and Finnish cinema, developed a widespread professional network, and developed a reputation as a figure distinct for his exotic cultural background in the land of the midnight sun. Yet this reputation, as we saw in the conflicting dimensions of nationality in his cinema, is at once useful and an obscuring façade. Layers of small nation clash, but in their dissonance with each other help us see the way that Kaurismäki’s cinema is an example that is interesting in its own right, but also helps develop further theories of national and small-nation cinema. Chapter four argues that the dimensions of national cinema in the Kaurismäki discourse are highly relevant to the films, but also misleading, inasmuch as Kaurismäki’s cinema is a small-nation cinema that has grown through the transnational festival circuit and circulation as world cinema.

The criticism on Kaurismäki’s films and career calls to mind commentary on the American humourist Garrison Keillor, a heuristic comparison that helps make clear this book’s argument about Kaurismäki’s cinema. Keillor is celebrated for his National Public Radio broadcast A Prairie Home Companion, which began in 1974. The two-hour variety show includes skits by a regular cast, performances by musical guests, and a twenty-minute monologue by Keillor about the fictional rural town of Lake Wobegon, Minnesota. The monologues relate stories about a stock set of characters, gently playing on ethnic stereotypes about their Scandinavian-American identities, Lutheranism, modesty, culinary habits, and other features of their everyday lives. Keillor tends to affirm stereotypes, often with a sentimental tone. Many commentators argue that Kaurismäki’s characters express a similar affirmation, embracing and endorsing stereotypes of Finnish identity. From this view, the films’ characters are modest, industrious, self-restrained, solidarity-minded, and silent, because Finns are. (As Bertolt Brecht famously quipped in reference to Finland’s official bilingualism, Finns are the only people in the world who are silent in two languages.) Yet from another view, Kaurismäki’s films are also ironic, the irony working to highlight the ambivalence of identities, representing as they do a period of rapid and tumultuous economic, political, and cultural change. The main critical paradigms for Kaurismäki’s films – the auteur, bohemian, nostalgic, and Finn – entail clashing and contradictory elements, which seen together put the lie to readings that align Kaurismäki with the kind of stereotypes we find in Keillor.

Kaurismäki’s cinema finds much more in common with writers like Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Jonathan Franzen, writers who, like Keillor, take up the legacy of immigrant identities and culture in the midwest of the United States. Such characters as Carol Millford in Main Street (1920), Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby (1925), and Walter and Patty Berglund in Freedom (2010) struggle against the confining identities and social mores of the American Midwest – and in particular Scandinavian-American identities for Lewis and Franzen – seeking to distance themselves from their families and the region through professional, social, and personal transformation. Their efforts critique and divulge such identities’ combination of emptiness and resilience, that is, their foundation in vacuous stereotypes, which the novels seek to analyse and criticise. They also analyse the grip of such stereotypes on their lives, influencing their characters’ notions of themselves and others’ perceptions of them. These novels stand in contrast to Keillor’s sentimental affirmation of such stereotypes, which in his rendering disclose notions of authenticity, community, and intimacy. Novels such as Main Street, The Great Gatsby, and Freedom do not find authenticity, community, or intimacy, because their characters can identify with those in their social worlds in only conflicted and qualified ways. Kaurismäki’s films share this quality, for his characters are invariably aliens in their social worlds, inhabiting the lower depths of society, cut off from family, unable to connect with romantic partners, and able to find redemption only in apparently ephemeral moments of solidarity, cooperation, and love. These experiences are those of subjects living in economic and political transition, destabilised by larger forces. In this world, static and essentialising stereotypes provide little footing. The novels of Lewis, Fitzgerald, and Franzen of course differ in any number of ways from Kaurismäki’s films, yet they share some key themes, which help point us away from the conventional accounts of Kaurismäki’s filmmaking and towards a richer account of it. Recontextualisation of Kaurismäki allows us to see a richer set of relationships to European cinema, world cinema, and the globalisation of cinema, but doing so first requires a brief introduction to the director.

Aki Kaurismäki

Aki Kaurismäki was born on 4 April 1957 in the town of Orimattila in south-central Finland, the third of four children. Kaurismäki’s father worked for a variety of textile companies in sales and management. The family lived in seven different towns before Kaurismäki left home, after completing secondary school.7 Kaurismäki left his compulsory military service in Finland’s army incomplete, and applied to Finland’s film school in 1977. The school denied him admission. Kaurismäki studied journalism for several years at the University of Tampere, but did not complete the degree. Between 1978 and 1981 his older brother Mika studied filmmaking at Munich’s University of Film and Television. Mika’s final project furnished Aki with an entry into filmmaking. Aki co-authored the screenplay for The Liar, in which he also played the protagonist. The film won the Risto Jarva Prize at Tampere’s short film festival in 1981. Although the film sold only some five hundred tickets in its theatrical run, it made an impact on Finland’s intelligentsia (see Hyvönen 1990). The Liar signalled the Kaurismäki brothers’ distinct style. They parlayed the prize money and prestige of their prize into financing for three further projects during 1981 and 1982. Aki Kaurismäki made his directorial debut in 1983 with an adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. He followed up at a prolific pace, writing, directing, editing, and producing four more shorts and six more features by the end of the 1980s. His third feature, Varjoja paratiisissa (Shadows in Paradise, 1986), was selected for the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in the spring of 1987 as well as for the Toronto International Film Festival later in the year. Subsequent films were selected for prestigious festivals, and since 1992 all of Kaurismäki’s features have screened at the Toronto, Berlin, or Cannes film festivals. Nominations and awards received for The Man Without a Past secured the director’s status as a leading figure in contemporary auteur cinema. At the time of writing, Kaurismäki has made seventeen feature films and eleven shorts.

The auteur categorisation fits Kaurismäki easily, as viewers, critics, and scholars have identified a consistency of style, theme, and vision across his body of work. He has exercised authorial control over all aspects of his film production from the beginning of his directorial career, and as the producer of his films, Kaurismäki has exercised total control over the films, including control of copyright. For example, he has used his control of his films’ rights to refuse distribution of them in the People’s Republic of China, protesting against China’s record on human rights (see Latomaa 2010). His auteurship has also meant that Kaurismäki himself makes all aesthetic and budget decisions about production.

For many critics and scholars both in Finland and beyond her borders Kaurismäki is not only a European auteur, but also a Finnish one. Their interpretations find support in the films’ silent, plain anti-heroes and old-fashioned aesthetics, which critics contrast to the determined achievers, acrobatic camera movements, and glossy look of mainstream cinema produced in Europe and the US. Kaurismäki’s auteur identity is also the result of specific publications’ enthusiasm for his work. Kaurismäki’s films have received much attention on the pages of Cahiers du cinéma, Positif, Sight and Sound, Filmihullu, and other auteurist magazines. Critics at influential dailies, such as Die Zeit, Parisien, the New York Times, Dagens Nyheter, and Helsingin Sanomat have also favoured his films. Critics writing on these pages have often interpreted his films’ idiosyncrasies as an expression of exotic Finnishness. High visibility on the international festival circuit, prestigious nominations and awards, and broad theatrical distribution have consolidated Kaurismäki’s critical reputation as Finland’s greatest filmmaker and one of the bearer’s of the Scandinavian auteur legacy.

Yet if Kaurismäki has become known as Finland’s greatest filmmaker, his greatness derives in part from the methods and critical agendas of his interpreters. Most critics and scholars have interpreted Kaurismäki’s films by way of close reading and biographical criticism, methods that have come down from Cahiers du cinéma’s ‘great man’ theory of auteurism. Kaurismäki makes evident in his films and in comments that he is a devotee of the French New Wave, and critics have repeatedly emphasised the intertextual connections of his films to those of Jean-Luc Godard, among others. Kaurismäki has encouraged this, suggesting that his intense viewing of films during his twenties was modelled after ‘Jean-Luc Godard during the early 1960s, only I didn’t have a sports car’ (in von Bagh 2006: 18). Close reading and biographical criticism have led to arguments that the director’s brilliance finds expression in his films’ moral themes, intertextual engagement with the ‘high’ tradition of auteur cinema, and humorous yet honest expression of national sentiments. Kaurismäki’s influential interpreter, collaborator, and friend Peter von Bagh, for example, has devoted his career to championing auteur cinema in Finland, not least through his and others’ commentaries on Kaurismäki’s films in the magazine Filmihullu, of which von Bagh was long-time editor. Kaurismäki’s ‘working-class’ films, argues von Bagh, combine a realist depiction of the everyday experiences of average Finns with cinephilic inspiration from the French New Wave as well as Robert Bresson, Mikko Niskanen, Yasujiro Ozu, Douglas Sirk, Teuvo Tulio, and other auteurs. Von Bagh argues that this combination of content and form articulates a moral challenge to a dehumanising Finnish state and the neoliberal economy it has embraced since the 1980s (see von Bagh 2006). The national interpretation of Kaurismäki has proved influential, as Finnish critics have disseminated it and the director himself has given it support through cryptic remarks about Finland in interviews. Commentators outside Finland have also noticed the lower-class characters and cinephilia, and while they give more emphasis to Kaurismäki’s cinephilia and nostalgia for the cinematic past, they have also often construed the films’ Finnish identity in an exoticising manner. Within this critical methodology, Kaurismäki is presented as a national auteur whose original engagement with the history of Western art cinema and culture transcends national identity, at the same time as the films powerfully express a specific ‘Finnish-ness’.

Kaurismäki’s status as a national auteur and example of Finnish national cinema is more complicated than Finnish and international critics usually consider, for his cinema’s many contradictions raise the question, ‘What is national cinema?’ One of the points of reference in most answers to this question is film scholar and theorist of national cinema Andrew Higson’s now-classic study of British cinema, Waving the Flag (1995). He argues that national cinema is not only a matter of traditions of national representation, but also involves economics of production, audience tastes, critical agendas and canons. In situating Kaurismäki within Higson’s matrix, we find that the director draws on representations of the nation that come down from the auteurs within Finland’s studio period: Teuvo Tulio, Valentin Vaala, and Nyrki Tapiovaara, developing their tradition of melodrama. Many critics have argued that Kaurismäki’s characters’ silence and long-suffering optimism represents national attitudes. On the other hand, one can see this silence as an aesthetic rejection of the Hollywood cinema’s reliance upon method acting and dialogue-driven narrative, an affirmation of Robert Bresson’s mute characters, and a distinct style of minimalist direction (see Nestingen 2007). Similar complexities touch production and audience taste. Since the 1980s Kaurismäki has assembled diverse funding arrangements for his films, with important production support coming from Germany, France, and Sweden, and production occurring in the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Mexico, Poland, the UK, and the US, in addition to Finland. And Kaurismäki’s films have never been popular with Finnish audiences – as the freak-show remark cited above makes clear. While successful domestic releases reach audiences of one hundred thousand and blockbusters surpass two hundred thousand in Finland, Kaurismäki’s biggest box-office success in Finland was The Man Without a Past, which sold 176,232 tickets, while total international ticket sales for the same film were 2,050,702.8 Kaurismäki’s critically praised Juha sold only 10,174 tickets in Finland.9 Issues of aesthetics, economics, and audience taste suggest Kaurismäki’s cinema cannot be categorised simply in national terms. Critics’ zeal to identify a Sibelius of the cinema accounts to a significant extent for Kaurismäki’s definition as a Finnish auteur. Von Bagh’s influential stance on Kaurismäki’s cinema is an especially prominent example of this position.

The Finnish state has also supported Kaurismäki’s rise as a filmmaker through the Finnish Film Foundation (Suomen elokuvasäätiö). The Finnish Film Foundation was established in 1969, around the time that similar film institutes and funding programmes were established in other Nordic and European states to sustain the production of quality films. While the Finnish Film Foundation has since undergone many changes in its funding policies, it has annually provided approximately half the funding for film production in Finland – national television providing approximately another quarter. Kaurismäki’s film career has received substantial support over the years. During the 1990s, for example, he was the single biggest recipient of support, receiving 13.4 million Finnish Marks (FIM) of the total 81.4 million FIM disbursed: ‘Aki Kaurismäki is the only European-level director [in Finland] … and so he is treated as something of a special case in funding decisions’, said Erkki Astala in 1999, while serving as director of production support at the Finnish Film Foundation (quoted in Arolainen 1999).10 In addition to receiving funding, Kaurismäki has also played a seminal role as a model of international distribution for Finnish Films. His films have been widely distributed internationally since the late-1980s, when World Sales Christa Saredi began representing him. These distribution networks have made Kaurismäki a model for Finnish producers and filmmakers seeking to reach an international audience. He provides an example of how a small nation cinema can reach across and beyond borders. But such a cinema largely plays to a deterritorialised transnational audience in large cities.

What then is Kaurismäki’s cinema? His films display a continuity of narrative, style, and mode. They are largely built on the same narrative structure: typically, the protagonist is displaced and isolated by a trip, a conflict, or other unexpected but not unusual events; the character struggles unsuccessfully in this new context to establish him- or herself; finally, the character experiences a weak, secular redemption. Stylistically, the films draw eclectically on the art-film tradition, but also borrow music and mise-en-scène from the history of cinema and post-war popular culture. Kaurismäki’s Tulitikkutehtaan tyttö (The Match Factory Girl, 1990) is modelled on Bresson’s Mouchette (1965), for example. Intertextual links to Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Jean-Luc Godard, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Yasujiru Ozu, and others are recurrent. Stylistic consistency is also evident in the films’ static camera, anachronistic mise-en-scène, colour design, lighting, and darkly ironic humour. While the films are realist in a sense, depicting quotidian problems of working and family life, they also exaggerate their realist details into melodramatic revelations about the moral underpinnings of everyday struggles and problems. In this sense, the films share more than a little with the nineteenth-century literature that combines realism and melodrama, and which has fascinated Kaurismäki. Indeed, adaptations of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Henri Murger, Juhani Aho, and an earlier interrogator of moral conflicts, William Shakespeare, figure in Kaurismäki’s oeuvre. Kaurismäki’s characters are misfits, his style is an amalgam of postmodernist eclecticism, and he is a deeply, if oddly, political filmmaker.

This book studies Kaurismäki’s cinema as a multiply constructed and contested auteur cinema. Kaurismäki’s cinema includes not only the films but also their production history, circulation, reception, and the economic, political, and cultural dimensions these involve. In speaking of Kaurismäki’s auteur cinema as multiply constructed and contested, I mean to stress that diverse elements comprise Kaurismäki’s, which cinema are best studied as parts of ongoing dialogues whose character and significance vary by institutional context and location. This book finds its methodological sources in star studies and revisionist studies of film authorship (see Dyer 1979; Gledhill 1991). Star studies has convincingly shown the extent to which stars are comprised of multiple semantic strata, which cohere and contrast to produce continuities and divergences of meaning. A star can embody excessive heterosexual masculinity on one level, yet a counter discourse can qualify that excess by making the star’s sexuality a riddle. To see these continuities and contrasts, we need to study a broad discursive field rather than a circumscribed set of texts. Revisionist studies of film authorship have suggested that star and authorship discourses share much in common, even if there are significant dissimilarities in their cultural and economic function. Multiple semantic strata connect a broad set of meanings and expectations to a subject and his or her creative work (see Koskinen 2002, 2009; Gerstner and Staiger 2003; Wexman 2003). Further, the subject and the creative activities consist of multiple narratives, affects, and images, which cohere and clash. This has long been evident in biographical film criticism, which in linking two levels of meaning, film narrative and biographical narrative, has often altered our notions of a body of film. By discovering Carl Theodor Dreyer’s adoption by Danish parents and his Swedish mother’s accidental suicide, for example, Martin Drouzy (1982) forever altered the narratives in circulation about Dreyer’s filmmaking. This study is not concerned with creating a biographical narrative of Kaurismäki, however, but rather with interconnecting the many narratives that have circulated about his cinema.

Because Kaurismäki’s cinema presents us with a set of contradictions which involve some of the key issues in film studies scholarship and criticism since the 1970s, including not only authorship but melodrama, national cinema, nostalgia, and the cultural politics of cinema, an account of the multiply constructed and contested characters of Kaurismäki’s cinema gives us not only a richer and more nuanced account of the director as a cultural figure but also a richer account of these categories and their potential for meaning and revision in debates around them.

Notes

1 Ne suis-je pas un faux accord/dans la divine symphonie/Grâce à la vorace Ironie/Qui me secoue et qui me mord?/Elle est dans ma voi, la criarde!/C’est tout mon sang, ce poison noir!/Je suis le sinister miroir/Où la mégère se regarde./Je suis la plaie et le couteau!/Je suis le soufflet et la joue!/Je suis les membres et la roue,/Et la victime et le bourreau!’ (Baudelaire 2006 [1861]: 163–4).

2 Lindén resigned her post as Minister of Culture a few days later, when she was caught up in a scandal of a conflict of interest. The Ministry of Culture’s budget includes amateur sport; the ministry had allocated an unusual amount of funds to Lindén’s golf club.

3 My previously unpublished interview with Aki Kaurismäki is included in the present volume as an appendix. It is listed in the bibliography as Nestingen 2007.

4 Roger Connah’s study K/K: A Couple of Finns and Some Donald Ducks (1991) is the only book-length study of Kaurismäki in English. It only covers the first ten years of Kaurismäki’s thirty-year career and it is not easily available, published by a small Finnish publisher and held by few libraries outside Finland. Its style is also inaccessible.

5 It is difficult to conceptualise the postmodern moment or condition without the concept of ‘grand narrative’ as elaborated and criticised by Jean-François Lyotard in his argument that recurrent foundational stories, such as the ‘narrative of progress’, no longer sustain belief (1979).

6 In his interview with von Bagh (2006: 18), Kaurismäki says: ‘In the fall of 1976 I was removed from the army…’. Kaurismäki’s choice of words implies he was discharged without completing the required compulsory service. The most common way of describing successful completion of compulsory service would be to say ‘kävin armeijan’ (‘I served in the army’) so-and-so years. Kaurismäki is effectively saying, ‘I was kicked out of the army’. Such an outcome was not unusual for musicians, artists and other dissident youth during the 1970s, before civilian service was offered as an option to complete compulsory service.

7 ‘Hyvinkää, Orimattila, Lahti, Toijala, Kuusankoski, Kouvola, Kankaanpää’ (von Bagh 1984: 8).

8 Interestingly, The Man Without a Past arguably reached these sales figures in Finland because of the film’s success at Cannes and a nomination for Best Foreign Film at the 2003 Academy Awards. On 30 June 2002, The Man Without a Past had sold only 72,066 tickets (see Näveri 2002b). Also see an earlier comment on Kaurismäki’s audience by the daily Helsingin Sanomat’s longtime film critic Helena Ylänen (1991).

9 Numbers taken from the Lumiere Database on admissions of films released in Europe, http://lumiere.obs.coe.int/. See Korhonen (1999) for an explicit statement of this argument.

10 Astala had previously worked as a publicity agent and production supervisor for Kaurismäki and his brother Mika at Villealfa Filmproductions. He left the Finnish Film Foundation to work for the Finnish National Television Service’s (YLE) features department. YLE funds about twenty-five percent of Finnish film production.