Hasia Diner

It was one of these letters from America, in fact, which put the notion of emigrating to the New World definitely in my mind. An illiterate woman brought it to the synagogue to have it read to her, and I happened to be the one to whom she addressed her request. The concrete details of that letter gave New York tangible form in my imagination. It haunted me ever after.

The United States lured me not merely as a land of milk and honey, but also, and perhaps chiefly, as one of mystery, of fantastic experiences, of marvelous transformations. To leave my native place and to seek my fortune in that distant, weird world seemed to be just the kind of sensational adventure my heart was hankering for.

When I unburdened myself of my project to Reb Sender he was thunderstruck.

“To America!” he said. “Lord of the World! But one becomes a Gentile there.”

“Not at all,” I sought to reassure him. “There are lots of good Jews there, and they don’t neglect their Talmud, either.”

Abraham Cahan, The Rise of David Levinsky (1917)1

Jews from Europe began to flock to New York City in the 1870s. The single most significant piece of New York real estate for the immigrant Jews could be found below Houston Street and north of Division, bounded on the east by the East River and on the west by Allen Street. Variously referred to as “the East Side,” “the Hebrew Quarter,” or “the ghetto,” the Lower East Side, in fact a multiethnic neighborhood, served as the epicenter of Jewish immigrant life, persisting in importance well into the 1920s. Between 1880 and 1890, three quarters of all New York Jews lived there. Their number reached about 60,000 when reformer Jacob Riis, author of the 1890 exposé How the Other Half Lives, declared the neighborhood the most densely inhabited spot on earth, more heavily populated than Calcutta or Bombay.

In the following decades, the number of Jewish immigrants in the city grew exponentially, and by 1910 it was home to about 1.2 million Jews, who constituted fully one–quarter of the city’s total population. This number reached 1,649,000 by 1930, nearly 30% of the population, and in 1940, nearly two million. Despite the post–World War II suburbanization movement that pulled Jews out of the city and into New Jersey, to other adjacent counties of New York State, and to faraway places like Los Angeles and Miami, the words “New York” and “Jewish” had become almost synonymous.

Thalia Theatre, c. 1904.

In many ways, the Jewish newcomers resembled their Irish, Italian, Slavic, and German co–immigrants in the years of the great Jewish migration, a period that lasted until the passage of the National Origins Act in 1924, which imposed an immigration quota system. Newcomers usually lived in crammed tenement dwellings on the Lower East Side and over time moved out to somewhat better, less–crowded neighborhoods. With the opening of the Williamsburg Bridge in 1903, linking the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn, the overall population of the Lower East Side and the number of Jews who lived there began to decline, as new neighborhoods cropped up in Brooklyn. By the next decade, Jews had mostly left the Lower East Side—or new immigrants merely sidestepped it—instead opting for Harlem and emerging sections of the Bronx. But immigrant Jews and their children kept coming back to the Lower East Side neighborhood for meetings, shopping, and leisure activities. It retained its Jewish aura well into the postwar era despite the paucity of Jews still living there.

In the heyday of the Lower East Side, the mostly Yiddish–speaking immigrants built a phalanx of social, cultural, political, and religious institutions that reflected their shared values and often reflected the hometowns and regions from which they hailed. They formed landsmanshaftn, local societies established for the purposes of mutual benefit, health care, and, just as importantly, socializing with friends and family from back home. Like all immigrants, they sought to maintain connections with those places and participated in transnational networks that linked both sides of the Atlantic.

Jewish immigrants, like those from other lands, wanted to keep alive elements of their culture, be it language, religion, foodways, or art forms, though articulated in increasingly American tones and terms. They invested in schools that taught Hebrew to enculturate their sons into the dictates of Judaism. By the early 20th century, as Eastern Europe receded further and further into the background, they created schools like the Sholem Aleichem Folk Shules and those operated by the Arbeiter Ring (the Workmen’s Circle) to teach the Yiddish language and foster a connection to the world of their parents and grandparents.

Immigrants at Ellis Island, postcard by Detroit Publishing Co., 1908.

Ellis Island was America’s busiest immigrant inspection station from 1892 until 1954. During its first year, almost 450,000 immigrants were processed there; that number reached one million at its peak in 1907. Overall, more than 12 million people entered the country through Ellis Island.

Chicken market at 55 Hester Street, between Ludlow and Essex Streets.

Photograph by Berenice Abbott, 1937.

The sign, written in Yiddish characters, reads, “Strictly kosher chicken market.” This is a direct transliteration from English.

Pretzel woman, Hester Street.

Photo by Alta Ruth Hahn., n.d.

New York’s Eastern European Jewish immigrants consumed Yiddish newspapers on a daily basis, and one of them in particular: the socialist–leaning Forverts, founded in 1897, known in English as the Jewish Daily Forward. By 1916, it sold more copies than any other foreign–language daily in the United States. In 1914, the combined circulation of the four Yiddish dailies—the Forward, the Warheit, the Morgn Journal, and the Yiddishe Tageblatt—exceeded 455,000.2 The communist daily Freiheit, established in 1922, reported a circulation of 64,500 in 1930, about a third of that of its archenemy, the Forward (at 175,000). In addition to promoting their respective political and social ideologies, these newspapers were instrumental in shaping cultural tastes and functioned as an important platform for practically all the major Yiddish writers, whose work they printed and often serialized well before they appeared in book form. The city was also home to scores of Yiddish weeklies and monthlies devoted to politics, literature, theater, drama, music, and humor. The world of Yiddish culture in New York extended to book publishing, which included Yiddish–to–English dictionaries and manuals, encyclopedias, popular literature, poetry, and major literary works—both originals and translations. It was a bustling cultural scene: newspapers, bookstores, publishing houses, cafés, restaurants, and theaters provided news, ideas, and entertainment to a population standing between their premigration antecedents and the America into which their children would integrate.

Eastern European Jewish immigrants made the journey to America largely for economic reasons, a force that pulled in all newcomers regardless of place of origin or religion. Jews found New York particularly attractive and, unlike others, opted for New York more than any other city. Most Irish, Italian, Polish, and other immigrants spread out over many American cities; while they formed solid enclaves in Gotham, New York did not dominate their American experience. Comparatively fewer Jews ventured beyond the metropolitan area, so that more than half of American Jews lived in the city by the early 20th century.

The economic profiles of the city and of the Jews explain the New York–centric dynamic of their migration and settlement. The city had emerged as the center of American garment making in the 1860s and 1870s. The garment industry, the city’s largest employer by 1930, served as the Jews’ economic niche. In the early decades of the migration, most work took place in tenement apartments, labeled pejoratively by progressives as “sweatshops.” Each day, Jewish families transformed their tenement dwelling spaces into shops, employing women and men, other Jews, who sat down in front of sewing machines and stitched together garments, brought in unsewn and brought back finished to contractors. Sweatshops gave way to more modern factories by the 1910s, like the infamous Triangle Waist Company, which in 1911 was the site of the worst industrial accident in American history.

Waiting for the “Forward.”

Photograph by Lewis W. Hine, 1913.

Newboys gather on the steps of the Forward Building. Some of the boys are holding copies of the daily Di Varheit (The Truth), a liberal paper that tried to compete with the Forward.

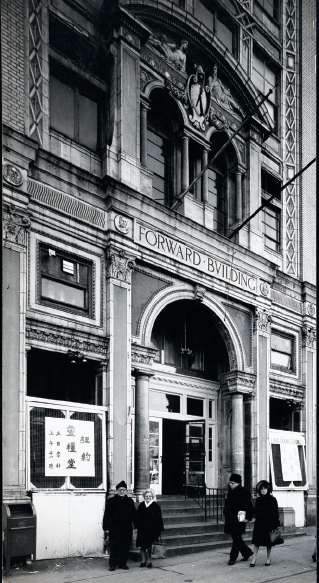

Forward Building.

Photograph by Edmund V. Gillon, c. 1979.

The Forward Building, built in 1912 and located at 173–175 East Broadway, across from Seward Park, was home to the Forverts (Forward) the most important Yiddish newspaper in America, edited by Abraham Cahan from 1903–46. Portraits of Socialist icons, including Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, were carved onto the facade. The building also housed other Socialist organizations, notably the offices of the Arbeter Ring (Workmen’s Circle). When this picture was taken, the building served as the Ling Liang Church. It was later converted into luxury condominiums.

Jewish laborers in the garment industry worked for Jewish bosses, most of whom had started out as workers themselves. Given the low level of capital needed to get started, sweatshop workers could imagine that they might well end up becoming employers. The industry employed men and women (usually young, unmarried women) alike, and, while Italians also worked in this field, Jews predominated. Their preponderance played a role in the unionization of the needle trades. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), founded in 1900, brought Jewish unionists into confrontation with Jewish employers, as did other predominantly Jewish unions like the International Fur and Leather Workers’ Union, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union (1914), and the International Cloth Hat, Cap, and Millinery Workers’ Union (1934). These unions demanded the right to engage in collective bargaining for purposes of improving wages and work conditions, and there was a lengthy history of brutal strikes and shutdowns. They built cooperative housing for their mostly Jewish members, established healthcare facilities, opened up summer resorts like Unity House (1919), which provided vacations for ILGWU members in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania, and invested in cultural programs—all in the name of union solidarity. In 1937, the ILGWU opened a highly popular and intensely political musical, Pins and Needles, in which union members—sewing machine operators, cutters, pressers, basters, and buttonhole makers—sang and danced their vision of Jewish–inflected class consciousness.

Ideas mattered tremendously in this community. Though the majority tended to vote with New York’s Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party machine, socialism fostered communal consciousness. The Forward announced itself as a socialist newspaper, and its founding editor, Abraham Cahan (1860–1951), hoped to convert the Jewish masses, though over the course of time his socialist fervor dampened. Meyer London (1871–1926), running on the Socialist Party ticket, served in Congress from 1915 to 1919 representing the Lower East Side. Baruch Charney Vladek (1886–1938) won election as a Socialist in 1917 to New York City’s Board of Alderman, as did many others. Socialism had to compete not only with Tammany Hall but also with anarchism, Zionism, and eventually communism as an ideology bent on winning over the hearts and minds of New York City’s immigrant Jewish quarter. Like other immigrants here and elsewhere, the Jews of New York saw politics—local, state, national, and even international—as a way to advance their group agenda.

Mr. Goldstein’s sweatshop, 30 Suffolk St.

Photograph by Lewis W. Hine, 1908.

Bodies from Washington Place fire, 1911.

Police and fire officials place victims of the Triangle Waist Company fire in coffins.

The Great Teachers, mural by Abraham Bogdanove. Oil on canvas, wall–mounted, 1930.

“The Great Hall” at Shepard Hall, the centerpiece building of the campus of the City University of New York (CCNY), features (in the Lincoln Hallway) a mural (53 feet long by 8 feet high) entitled “The Great Teachers.” Each of the four divisions of the mural, which spans three arching doorways, contains three figures (from L. to R.): Rama, Confucius, Zoroaster, Krishna, Buddha, Abraham, Hermes, Moses, Paul, Orpheus, Socrates, and Plato. The mural was created in 1930 by Jewish–American artist Abraham Bogdanove (1888–1946), a native of Minsk, Belarus, who immigrated to New York City in 1900. Bogdanove received his artistic education at The Cooper Union, The National Academy of Design, and Columbia University’s School of Architecture. At the time he created the mural 75% of the students at CCNY were Jewish.

MIKE BURSTEIN

remembers a moment with his father,

PESACH BURSTEIN

I made my Yiddish theater debut when I was three years old. My father and mother, Pesach’ke Burstein and Lillian Lux, were starring in one of their musical comedies at New York’s National Theatre on Second Avenue. It was a Christmas matinee, and my father was onstage singing one of his songs. I was watching him from the wings, along with my twin sister, Susan, when several of his fellow actors suggested I join my daddy onstage. They knew I could sing all of my father’s songs. They put a false beard and a top hat on me, and I walked right out onstage and stood there. The audience started laughing and pointing towards me. My father stopped singing, called me over, and asked me who I was. I answered, “I’m Santa Claus.” He asked me what I was doing there and I said, “I want to sing.” “What do you want to sing?” I mentioned one of my father’s most famous songs, “Hotsa Mama Pirba Tsosa,” and proceeded to sing it, accompanied by the orchestra in the pit. I took a Shakespearean bow and ran off. I returned for a second bow to a standing ovation. A man threw a silver dollar onto the stage and yelled, “Someday you will be as great as your father!” I haven’t stopped trying to fulfill that prophecy.

MIKE BURSTYN, ACTOR, LOS ANGELES

Integration into America became the dominant motif for the children of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. They experienced life in the streets and schools of the city, and they moved with relative ease into the English–speaking world that their parents struggled with, as they finished high school and attended Hunter College (for women) and City College (men) in great numbers and entered professions. By the 1940s, Jewish women, the daughters of immigrants, made up the majority of the city’s schoolteachers. Others of their sisters came to dominate the fields of social work and dentistry, among others.

Where the immigration generation shaped a distinctively New York Yiddish stage, second–and third–generation Jews found their way into New York’s artistic world in such undertakings as songwriting, publishing, filmmaking, modern dance, the graphic arts, and theater, to name but a few. Some produced works with Jewish themes, creative works that examined aspects of Jewish history and culture. But whether tackling explicitly Jewish or more universal subjects, they produced a massive outpouring that expressed their collective cultural arrival by appealing to a broad swath of the American public.

May Day strikers in Union Square, 1913.

On May 1, 1913, 50,000 workers demonstrating the solidarity of the working class gathered in Union Square, the radical hub of New York City. The Yiddish sign at the left reads, “We demand union shops and union conditions.”