Barbara Henry

Jacob Gordin (1853–1909), a Jewish–Russian writer deeply grounded in the culture of his homeland, came to America in 1891, where he established himself as the first literary playwright staged in the Yiddish language. His often daring plays became one of the cornerstones of the Yiddish dramatic repertoire, including his 1902 The Kreutzer Sonata, which became the first Yiddish play to be translated and produced in English. Notably, within the world of Jewish New York, Gordin was a pivotal figure in the maturation of Yiddish theater from its early, haphazard ethos into an influential art form.

The professional Yiddish theater was a mere 15 years old when Jacob Gordin encountered its American iteration in New York in the autumn of 1891. He had some acquaintance with the emerging Yiddish theater of his native Russia and had airily dismissed its repertoire as consisting of little more than “pretentious” Goldfaden operettas and comedies, with titles like Rivke and the Gefilte Fish.1 But what Gordin saw at New York’s Union Theatre defied all his expectations—and lowered the bar yet further. The raucous play involved a blind miller, speechifying in a weird Germanic dialect, arias cribbed from Italian operas, and people running around hitting each other. The audience seemed to enjoy it, though they were at least partly distracted from its ghastliness by their restless young children and the peddlers selling seltzer and apples during the play: “Everything that I heard and saw was far from Jewish life, was vulgar, without aesthetic merit, false, vile, and rotten.”2 Surely Gordin, a Russian writer and journalist, fluent in four languages and well–read in world literature, could come up with something better.

Even his minimal qualifications for the job of Yiddish playwright exceeded those of the existing field of American Yiddish dramatists: Joseph Lateiner (1853–1935), Moyshe “Professor” Hurwitz (1844–1910), and Nokhem Shaykevitsh (Schomer, 1849–1905). These writers catered with varying degrees of proficiency to Yiddish–speaking audiences’ love of romantic, musical, and sentimental plays, churned out rapidly to satisfy a public with little education but a voracious enthusiasm for the theater. The quality of this Yiddish dramaturgy rarely equaled the talents of its actors, a number of whom—Jacob P. Adler, David Kessler, Sigmund Mogulesko, and Sigmund Feinman—met with Gordin shortly after his arrival in New York. Gordin was impressed and wondered, “If Yiddish actors are men like other actors of the world theater, why should the Yiddish theater not be like other theaters?”3

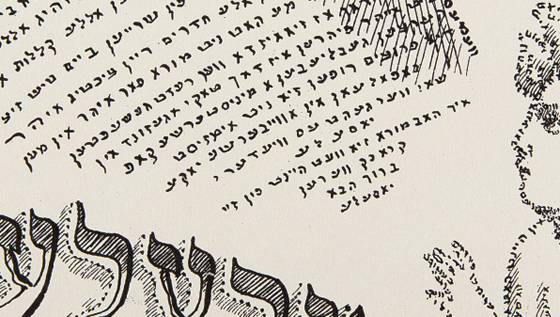

Commemorative micrograph portrait of Jacob Gordin by L. Rotblat, 1909.

This poster of playwright Jacob Gordin employs the traditional Jewish art form of micography, which uses Hebrew letters to create an image. The portrait is made up of the entire text of Gordin’s play Mirele Efros.

The impulse to make the Yiddish theater more like the theaters of Russia, France, and Germany, and less like its vigorous, creative, and occasionally awful self, was typical of Gordin’s belief that whatever was traditionally Jewish was probably in need of correction. That Russia, France, and Germany had popular theaters no less flamboyant than those of the Lower East Side was not seen as evidence of American Jews’ theatrical parity, however. In Europe, the popular theater was balanced by a literary one: puppet shows, slapstick, and Grand Guignol competed with the Moscow Art Theatre, the Meiningen Ensemble, and Antoine’s Théâtre–Libre. Gordin would offer Yiddish–speaking New York a serious drama of its own.

In place of crowd–pleasing melodramas with songs (repeated at the request of audiences) and “elegant” daytshmerish (the stage dialect that resembled neither Yiddish nor the German it strenuously strove to imitate), Gordin aimed at a realist, literary Jewish theater. Realist plays of the late 19th century aspired to be case studies, observing human beings in their social environment, examining the forces that made them who they were and helped determine the choices they made. Realism was indelibly associated with progressive politics and compassion for the working man and woman: the faithful reproduction of reality on stage would bear witness to life’s injustices, and by exposing these perhaps lead to their amelioration. This creative stance, predicated not on creating a diverting fantasy but on the observation of empirical reality, would determine the subject matter, staging, and sociopolitical orientation of Gordin’s plays.

This was an ambitious undertaking in 1891, particularly for a novice playwright. In Gordin’s native Russia, realism was a bold artistic mode that would reach its apex at the Moscow Art Theatre, established in 1898. A Yiddish stage based on realist principles such as Gordin envisioned would actually put the Yiddish theater leagues ahead of the English–language American stage’s development of the same principle. But it was going to be a hard sell in New York. Yiddish–speaking audiences were already well aware of injustice. Working for a pittance in factories, in shops, at manual labor, doing piecework while caring for children, would they really want to gaze more closely at reality rather than escape it for a few hours? Did they really want to see crime, exploitation, poverty, and suffering on stage when they could see cheerful comedies, musicals, or matinee idol Boris Thomashefsky on a white horse?

Bust of Jacob Gordin by Julius Butansky. Bronze, 1905.

With the support of the influential journalists of New York’s radical Yiddish newspaper the Arbayter tsaytung (The Workman’s Paper), Gordin forged ahead. His first full–length Yiddish play, Siberia, performed in November of 1891 at the Union Theatre, tells the story of Rubin Cohn, who escapes a transport to a prison camp and starts a new life under a different name. He marries and prospers, but eventually his ruse is discovered and tragedy ensues: his daughter commits suicide, and he is again in chains by the end of the drama. The opening night audience did not know what to make of a play in vernacular Yiddish, and one with no musical numbers and an unhappy ending. As they grew restless, the play’s star, Jacob P. Adler, made an appeal for patience, invoking Gordin’s reputation as a “famous Russian writer” deserving of their respect.4 It worked—that time.

What brought people back to Gordin’s plays was not his reputation or his bearing witness to injustice, but to his unique blend of the real, the musical, and the controversial. Gordin used his extensive knowledge of world literature to adapt and modernize the classics—Shakespeare, Goethe, Ibsen, Tolstoy, and many others—to reflect the anxieties and preoccupations of his Yiddish–speaking audience. The challenges of modern American life, and the wrenching changes it introduced into the lives of traditional Eastern European Jews, in terms of familial authority, sexual mores, work, language, and religious observance, are all explored in Gordin’s plays.

Literary adaptations proved vastly more popular with audiences than Gordin’s more overtly sociopolitical dramas like Siberia. Characteristic of Gordin’s adaptive method are Der yidisher kenig Lir (The Jewish King Lear, 1892) and Di yidishe kenigen Lir oder Mirele Efros (The Jewish Queen Lear, or Mirele Efros, 1898), which point directly to their source and focus on the Shakespearean play’s generational conflicts. But there were significant changes: Gordin shifts his settings to contemporary Eastern Europe to comply with realism’s call for familiar settings and vernacular language. Given the paucity of modern Jewish royalty, Gordin’s Lears are prosperous merchants, a move that then offers a platform for indicting the corrosive effects of capitalism on familial bonds. While his detractors, like the influential critic and novelist Abraham Cahan (1860–1951), were inclined to accuse Gordin of plagiarism, the playwright never concealed his sources. Indeed, Gordin invited audiences to draw direct parallels between the action of his plays and the non–Jewish texts on which his The Jewish King Lear or The Kreutzer Sonata were based.

Gordin, who had ten children to support, was extraordinarily prolific, churning out new works at an astonishing rate. Indeed, he wrote so many plays that it is difficult to estimate exactly how many he may have authored, as some (primarily historical operettas) were written pseudonymously. For all their programmatic politics, the source of the plays’ power and longevity is classically dramatic: age versus youth, duty versus love. But because these are also modern American works, created in a land where one can escape the long, skeletal hand of the old–world past, the protagonists of Gordin’s plays can alter their own tragic Shakespearean dénouement. In both Lear plays, the elderly tyrants, exiled from their families, return chastened but triumphant, as the love between parents and children overcomes the divisive power of economics to create a family unit that is stronger for its having been tested. And no one loses an eye, let alone two.

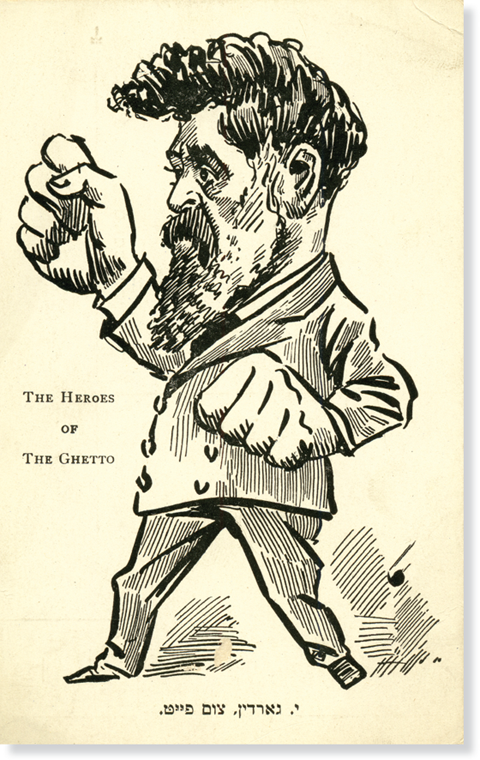

“The Heroes of the Ghetto” postcard with Gordin caricature, n.d.

This image shows a combative Gordin ready to fight for his ideals.

Gordin’s almost neoclassical reticence toward violence in his Lear plays is not carried over to his more controversial works. In Di Kreytser sonata (The Kreutzer Sonata, 1902)—a canny interrogation of Leo Tolstoy’s Kreitserova sonata (Kreutzer Sonata, 1889)—set first in Russia and then in New York City, an abused wife shoots her husband and then turns the gun on his lover—her own sister. The title of Di shkite (The Slaughter, 1899) refers to both the murderous knifing unleashed by another abused wife and the everyday treatment of women as little better than animals and objects of trade.

Indeed, the “woman question” was a perennial topic of Gordin’s plays. In addition to domestic violence, his dramas also treated free love (Di yidishe Safo [The Jewish Sappho], 1900), the repressive hypocrisies of the “respectable” male Orthodox bourgeoisie (Tares hamishpokhe [The Sanctity of Family Life], 1904), prostitution (Dvoyrele meyukheses [Dvoyrele the Aristocrat], 1896), and the unique problems of Jewish women immigrants (On a heym [Homeless], 1907). Many stars—Keni Liptzin, Bertha Kalich, and Sarah Adler in the United States, and Esther–Rokhl Kaminska in Poland—made their careers playing Gordin’s leading female roles.

One of Gordin’s best works, Got, mentsh un tayvl (God, Man, and Devil, 1900), addresses the realist imperative for art that reflects social and political problems but presents them in a form that does not disdain the Yiddish theater’s love for music and the supernatural. The play pointedly draws on Goethe’s Faust (1808), the Book of Job, and one of Gordin’s own Russian–language stories, Syupriz (The Surprise, 1885).5 In a prologue, Satan bets God that a devout Torah scribe and amateur musician, Hershele Dubrovner, can be corrupted by money. Satan takes earthly form as “Uriel Mazik,” a businessman who sells Hershele a winning lottery ticket in order to get the process underway. As Hershele’s wealth grows, he abandons his friends, divorces his wife, and ruins small local businesses that make prayer–shawls by opening a factory that mass–produces the garments. Only when his friend’s son dies violently in the factory does Hershele realize that he has betrayed everyone that he loves. He atones by hanging himself with a blood–stained prayer shawl. Satan loses his bet with God. The play reflects Gordin’s persistent themes: the toxic nature of capitalism, the susceptibility of traditional religious Jews to that toxin, the exploitation of women, and the power of art to save us from ourselves. The play is richly atmospheric, with colorful language, and Gordin skillfully weaves in Hershele’s violin solos to testify to both the depth of his feeling and the survival of his conscience.

Poster for Jacob Gordin’s The Jewish King Lear at the Windsor Theatre, October 13, 1898.

The performance, starring Jacob P. Adler, was a benefit for the Hebrew Legal Aid and Protective Association of New York.

Scene from Jacob Gordin’s God, Man, and Devil at Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theatre, 1928.

God, Man, and Devil reveals that Gordin’s realism is almost entirely concentrated in his language and in his fixation on economic problems. These are explored theatrically, however, in highly eclectic ways. Far from abandoning the Yiddish theater’s musicality, Gordin incorporated songs and even dance into most of his plays, always integrated logically into the plot. He even attempted symbolist abstractions à la Maurice Maeterlinck in Der unbekanter (The Unknown, 1904) and verse drama in Oyf di berg (On the Mountains, 1906). While these plays were both critically and commercially unsuccessful, their failures were not out of line with the similar results of avant–garde experiments in symbolist drama in Europe and Russia.

What then, accounts for Gordin’s reputation as a reformer, the author of the Yiddish theater’s turn to realism? What one generation finds “realistic” in the theater is anything that accurately reflects the spirit of their times and the emotional and intellectual needs of their audience. Gordin’s realism may not be ours, but it was for his audience. His innovations shifted expectations about form, language, and subject matter, and they showed younger writers what might be done further. Playwrights like David Pinski (1872–1959) and Peretz Hirshbein (1880–1948) would reject the Gordin repertoire and produce one that was more recognizably realist, but they did so in the wake of Gordin’s pathbreaking introduction of realism to the Yiddish stage. These attributes include vernacular Yiddish, contemporary settings, and a focus on controversial social issues—always in a form that entertained while striving to impart didactic content.

Gordin’s plays were important in their day and enjoyed real popularity as late as the 1940s, but the post–Holocaust era has not been kind to his legacy. Lacking the folkloric and musical dynamism of Goldfaden’s works, the hypnotic symbolism of S. Ansky (1863–1920), or the formal versatility of Pinski’s plays, the majority of Gordin’s works today languish in obscurity. The rapid development and tragically attenuated life of the Yiddish theater meant that playwrights such as Gordin achieved a prominence that they might not otherwise have enjoyed in a theatrical tradition of greater breadth and longevity. But given what has been lost in the life of the Yiddish stage, the very survival of so much of Gordin’s work, in dozens and dozens of texts, in memoirs, and in reviews, surely holds the promise of reevaluation, if not renewal.

Bertha Kalich as Miriam Friedlander in The Kreutzer Sonata, performed on Broadway, 1906.

Jacob Gordin created the lead role in The Kreutzer Sonata for Bertha Kalich. It was a play to which Kalich would return throughout her career, playing it in both Yiddish and English.

Keni Liptzin in the title role of Jacob Gordin’s Mirele Efros, c. 1896.

Skirt and blouse worn by Berta Gersten in the film version of Mirele Efros, 1939.

Gown worn by Berta Gersten in the film version of Mirele Efros, 1939.

Gordin’s play was made into a movie in 1939, directed by Josef Berne and filmed in Yiddish, with English subtitles. Berta Gersten, who played the title role, had made her stage debut as a secondary character in the play three decades earlier.

From Jacob Gordin’s Immortal Gallery, n.d.

Actors in major Gordin plays: Isidor Hollander as Uriel Mazik in God, Man, and Devil; Herman Yablokoff as Lemech in The Wild Man; Jennie Goldstein as Mirele in Mirele Efros. Bottom: Jacob Zilbert as Shloimke in Shloimke Sharlatan; Peter Graff as Kalmen Moishe in The Stranger; Bertha Gutentag as Chasi in The Orphan (Di yesoyme); Extreme right: Tose Goldberg as Mirele Efros.

Four Great Actresses in One Great Part, December 9, 1936.

Mirele Efros was performed at the Folks Theatre as a benefit for the publication Lexicon of the Yiddish Theater. Every act featured another actress as Mirele: (From right to left) Anna Appel in Act I, Berta Gersten in Act II, Dora Weissman in Act III, and Bina Abromowitz in Act IV.