The Revelatory House: Dwelling in the Domestic Mandala

‘Philosophers, when confronted with inside and outside, think in terms of being and non-being. Thus profound metaphysics is rooted in an implicit geometry…confers spatiality on thought.’

G. Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

In Kholagaun Chhetri houses, the yantric and mandalic are two ever-present, mutually-entailed configurations of the domestic mandala, like figure and ground, each always implying the other. In the previous two chapters, the yantric configuration, with its emphasis on the demarcation of terrestrial space and harmonious alignment to the cardinal directions, was in the analytic foreground as I described how it is built into houses through the orientation of the main entrance, the location of the worship room and the rituals accompanying construction. Now it becomes the auspicious background against which mundane activities of domestic life—preparing and eating food, performing household rituals, entertaining relatives and other guests, supervising people working within the compound, and processing grains and other foodstuff for storage—are in the foreground. Through these engagements with people and things that for Heidegger are the essence of human existence, world-building and knowledge, Kholagaun Chhetris dwell in their houses. Their dwelling is practical: in domestic activities, ideas about the cosmos are transfigured into everyday concepts and activities about purity, impurity and danger and incorporated into their lifeworld. Their dwelling is spatial and world-building: through inclusions and exclusions from specific areas of the domestic compound based upon purity, impurity and/or danger, people and things are brought into particular spatial relations that configure the domestic compound into a mandala consisting of concentric spaces around a centre, a map of the cosmos and a coherent world. Finally, their dwelling is revelatory: through these practical engagements and spatial inclusions and exclusions within the domestic mandala, Kholagaun Chhetris gain tacit and embodied knowledge of the cosmological foundations of their lifeworld as Householders.

The Centre of the Domestic Mandala

The first issue in describing Kholagaun Chhetri houses in the concentric mandalic configuration is locating the centre. This is not as straightforward as it seems because the centre of a mandala is a complex phenomenon. It is both literal and figurative as well as both absolute and relative. In the two forms of the mandala analysed in the first chapter (see Figure 1.1), the centre—bindhu—is spatially literal. It is located at the geometric centre of the drawings. But as I pointed out in that chapter, this literal presentation of the bindhu in the geometric centre is itself a figurative representation that uses its location as a spatial metaphor and microcosmic iteration of a basic idea of Hindu [tantric] cosmology: the fundamental and essential unity from which the diversity of all worldly phenomena and attachment to it are created and into which, upon enlightenment and detachment, they are dissolved.

In figuratively expressing this idea, the centre of a mandala is also both absolute and relative. It is absolute in the sense that the meaning of unity it represents is unconditional, beyond the flow of time, the expanse of space, the effects of causation and the diversity of people and things that characterize the everyday life of humans-in-the-world. The transcendent unity the centre point iterates is not dependent upon human action and cannot be affected by it. Yet, to represent in worldly form this absolute and transcendent reality, the centre of a mandala is conditional and relative. In all mandalas, there is a periphery surrounding the centre point as a series of concentric girdles of pictures or geometric elements. Like the centre point they surround, these concentric zones have a figurative function. Their position relative to the centre of the mandala and the position of the centre relative to them together are spatial renderings of the dynamism of the cosmos: the creation of space, time, causation and worldly diversity expressed in centrifugal movement from the centre; the dissolution of space, time, causation and worldly diversity is expressed in centripetal movement towards the centre. For the Householder, this dynamism of the cosmos, represented by the juxtaposition of centre and periphery and the movement between them, is manifest in the paradox of attachment and detachment that characterizes their life-in-the-world. On the one hand, there is a moral duty for the Householder to create and become attached to the diversity of people, things and to life itself; such attachment conceals the fundamental unity of the cosmos and entraps the Householder in the round of death and re-birth. On the other hand, there is a moral duty for the Householder to adopt an attitude of detachment; such detachment dispels the illusion veiling the fundamental unity and liberates the Householder from the round of death and re-birth.

If in the mandala the geometric centre and the surrounding concentric girdles form a figurative map of the cosmos, then in looking for the centre of Kholagaun Chhetris’ domestic mandala, we are looking not for its geometric centre but for its figurative centre, that is, the space or room whose character, as constituted by the activities that take place in it and movement in relation to it, reiterates the concepts of detachment; simultaneously, we are looking for domestic spaces surrounding the centre whose character, as constituted by the activities that take place in it, expresses the idea of attachment. This provides a basis for tackling the observation with which I ended Chapter 2: in almost all Kholagaun Chhetri houses, the kitchen is not located in the southeast quadrant as would be expected according to the ‘vastu rules’. Instead it is positioned away from the main door, either in a room or corner of the ground floor furthest from the main entrance (see Figures 2.4 and 2.6) or in a room on an upper floor. In both locations the kitchen is inaccessible to outsiders by line of sight or physical access. These characteristics of the kitchen’s location place it in the centre of the domestic mandala, even though it is not in the geometric centre of the house structure or compound. To understand why its inaccessible location makes the kitchen the centre of the house, I first need to show how in domestic activities Kholagaun Chhetris transfigure the cosmological ideas of passionate attachment to worldly diversity and ascetic detachment from it into everyday concepts of impurity and danger and, in turn, configure their domestic compounds into maps of the cosmos.

Everyday Forms of the Cosmological

Bourdieu developed the concept of ‘bodily hexis’ (1977:93) to describe the way in which the knowledge and dispositions through which we conduct our everyday lives have not just a reflexive form in ideas and concepts that we may be able to verbalize but also a tacit form (see Polanyi 1962, 1966) in the gestures and movements of the body. This duality of the verbal/reflexive and tacit/corporeal characterizes the forms in which Kholagaun Chhetris experience cosmological ideas, build them into their houses, and their houses into mandalas. To paraphrase Bourdieu: ‘Bodily hexis is [cosmology] realized, em-bodied, turned into a permanent disposition, a durable manner of standing, speaking, and thereby of feeling and thinking (1977:93-94, brackets added, italics original). I would add here something more general that is implied by Bourdieu: bodily hexis entails moving in space. Such bodily movement or motility is central to Merleau-Ponty’s concept of ‘body image’ (1962:113ff) and its three constituent themes. First, space is a primary condition of our embodied being-in-the-world (Merleau-Ponty 1962: 112ff; Langer 1989:39). Second, the body, its spatiality and the world emerge together and are internally related in and through corporeal movement, that is, ‘motility as basic intentionality’ (1962:158-1599). As Merleau-Ponty writes: ‘it is clearly in action that the spatiality of our body is brought into being … By considering the body in movement, we can see better how it inhabits space (and moreover, time) because movement is not limited to submitting passively to space and time, it actively assumes them …’ (1962:117); space ‘is already built into my bodily structure, and is its inseparable correlative’ (1962:164). Third, and following, movement creates space generally and culturally. Here I am making use of Munn’s analysis of how space ‘extends from the actor … as a culturally defined, corporeal-sensual field of significant distances stretching out from the body in a particular stance or action at a given locale or as it moves through locales’ (2003 [1996]:94) and how Warlpiri actors produce cultural spaces of inclusion and exclusion through movement over their territory. Likewise, as I describe throughout the rest of the chapter, in the durable patterns of household activities and movement in their compounds, Kholagaun Chhetris create concentric spaces of inclusion and exclusion. This creation is mediated by an ensemble of concepts and symbols that Kholagaun Chhetris constantly used to talk about the dangers of impurity of lower caste people, curses of witches and attacks of disembodied ghosts that transfigure the ideas of attachment and detachment, illusion and revelation into everyday concepts and activities.

There are two dimensions to this transfiguration. Both derive from Kholagaun Chhetris’ self-identification as Householders whose way of life is defined by ‘grihastha dharma’. First, dharma is a general scheme for the relation between worldly action and embodied being. It specifies the code of sacred duties and moral conduct for individuals of different stages of life and different caste affiliations. Further, dharma is inherent in people. A person is born with it so that a particular mode of moral action in the world—whether it be that of the Householder or the Renouncer or that of a Brahman, Chhetri or Untouchable—is immanent in the body. In this sense, dharma is the transfiguration of the moral actions of a person’s past life into present corporeality through the operation of karma. Humans literally embody the consequences of their actions through karma. Here the notion of karma resonates with Langer’s incisive summation of Merleau-Ponty: ‘We are our body’ (1989:39). Conversely, embodied being is constitutive of action. As both physical and moral, the body is the medium of the moral actions that constitute life-in-the-world. Here dharma resonates with Gill’s précis of Polanyi: ‘Our bodies are both in the world as physical objects and the means by which we come to know the world through interaction with it’ (2000:45). Dharma and karma express the transitive relation between human action and embodied being in Nepali thought, a relation that is manifest in the way Kholagaun Chhetris understand the nature and operation of purity and impurity.

Second, the specific dharma of the Householder is defined by the three sacred duties: begetting children, feeding the ascetics and worshipping the deities. In fulfilling their dharma, Kholagaun Chhetris’ daily life is filled with the passion for and joy of attachments to the diversity of people and things in their world as they marry and raise a family, own and cultivate land for subsistence, and perform worship rituals to a variety of gods (see Gray 1995).1 While these passions and attachments are necessary for the Householder to fulfil dharma and live a prosperous life in the world, they are ultimately an illusion that conceals the fundamental unity of the cosmos. Kholagaun Chhetris told me that they should have an attitude of ‘ascetic detachment’ (birakta) to the people and things of their lifeworld so that they do not deem them to be the true nature of existence.2 It is this enigma of the Householder’s body-mediated attachments to and moral detachment from the world (see also Madan 1987) that is transfigured into everyday domestic activities concerning purity and impurity, good and evil, benign deities and malign ghosts.3

Purity and Impurity

For Kholagaun Chhetris, being Householders means that there are no more important media for living in the world than their bodies and the food they eat to sustain them. Purity (chokho) and impurity (juṭho) are conditions of what Kholagaun Chhetris called the ‘physical’ or ‘material’ body (bhautik sarir), meaning the organic body that people have because of and in order to live in the material world (sansār).4 Further, the body is a microcosm of the material world of the Householder. One of the more religiously strict men of Kholagaun told me that he eats only five mouthfuls of food at each meal—one for each element of the body which he said is composed of five basic material elements—earth, air, water, sky or ether, and light. These are the same elements that make up the material world; upon death and cremation, the body breaks down into these elements and merges with it.

Kholagaun Chhetris, like Hindus throughout South Asia, identify substances produced by the body—saliva, perspiration, urine, excrement, blood, semen and mucus—as the primary sources of impurity as well as the product and signs of embodied life-in-the-Householder’s-world.5 Eating is paradigmatic of actions that cause impurity. When people eat, the food they touch as well as the hand which conveys the food to their mouths become polluted with their own saliva.6 Likewise, defecating, urinating, sexual intercourse, menstruation, sleeping (during which people perspire), and blowing one’s nose are all everyday and necessary acts in which a person’s own body becomes impure. These sources of impurity have the common characteristics of being substances that flow from the inside to the outside of the body and the impurity they produce is the result of transgressing its boundary.7 This means that the vital, life-maintaining organic activities of everyday life-in-the-world—eating, sleeping, defecation, urination, menstruation, sexual intercourse—inherently ‘produce’ impurity. Kholagaun Chhetris cannot avoid them as part of their physical being-in-the-world just as they cannot avoid the passions and attachments of their moral (dharma) being-in-the-world as Householders. This parallel necessity of, on the one hand, corporeal life and the impurity it entails and, on the other hand, the dharma of the Householder and the attachments it entails suggests that for Kholagaun Chhetris impurity is the everyday bodily transfiguration of attachment and by implication that purity is the everyday bodily transfiguration of detachment.

Purity as Detachment

Purity is understood as a state of perfection characterized by a completeness, wholeness and integrity that has not been corrupted by human action (see Madan 1987:58ff) or by breaching the boundary between inside and outside. A virgin (kanya), paddy (dhān), husked rice carefully milled so that the kernels are unbroken (achheta), and unpeeled fruit are all considered pure because their wholeness and integrity have not been corrupted (bigreko) by human action. Purity makes these people and things appropriate as ritual offerings: virgins are given as gifts (dān) to their husbands in nuptial rites; paddy is used as the pure seat for deities; and unbroken rice kernels and unpeeled fruits are offered to them in pujas.

For humans, maintaining or restoring purity as wholeness, integrity and perfection that is uncorrupted by human action entails bodily deeds of detachment and asceticism. Bodily-produced impurity is personal and temporary. It is personal in the sense that only the individual whose body produces the impure substance necessarily becomes impure. It is temporary in the sense that a state of purity is easily restored. It can be rehabilitated by two kinds of activities—cleansing and abstinence. In the act of cleansing, the impurity of corporeal life is removed and the integrity of the body’s boundary restored by bathing with running water that courses over the body and flows away. Such purifying bathing occurs frequently throughout the day. For their morning bath, Kholagaun Chhetris pour water over their bodies to wash away the impurity of perspiration produced during sleeping; after eating, they pour water over the hands and rinse their mouths with water to cleanse the impurity of the saliva produced while eating; they use water from a vessel (lotā) to wash away the impurity produced in urination and defecation. Bathing is an effective act of purification because water has the property of absorbing the quality of the object with which in comes into contact. For this reason, bathing always involves actions to ensure that the water flows over the impure part of the body. The flowing water takes the impurity it has absorbed away from the body, re-establishing its wholeness by creating a separation from the organic substances which breached its boundary. The physical separation from polluting organic substances effected by bathing is a practice of detachment from the corporeal life of the Householder and the worldly attachments it necessarily entails and from which it is impossible—like organic life itself—to abstain. So, by bathing after coming into contact with effluvia inevitably produced by the processes of the body, Kholagaun Chhetris perform and experience their detachment from these processes.

The other method of purification is ascetic practice, usually consisting of abstinence from eating and copulation, activities which produce impurity. For example, dietary restrictions upon favoured foods (salt, garlic, onions, meat, and black lentils) offset the temporary impurity incurred by death and birth of close kin; celibacy before important rituals ensures the celebrant is in a pure state to interact with the gods. These abstinences involve Kholagaun Chhetris’ avoidance or non-involvement with things of worldly enjoyment—good-tasting food and the physical pleasure of sexual intercourse. They are metonymic of a Householder’s lifeworld and the necessary attachment to and/or passion for people and things—food, kinship relations and sexual relations. The purity achieved by abstinence from such passions and pleasures is another corporeal experience of detachment in the midst of the attachments of everyday life.

Impurity as Attachment

Impurity also has a permanent and collective form associated with castes whose members are affiliated through current or presumed historical practice with occupations that require contact with the impure substances or actions of others’ bodies. For example, in Banaspati, villagers explain that occupations associated with the Washerman (dhobi) caste entails contact with other people’s sweat in the clothes they wash, the Tailor (Damai) caste with the skin of dead animals used in the drum they traditionally play at weddings and other celebrations, and the Leatherworker (Sarki) caste with the skin of dead animals in making shoes. In all these castes, the occupation involves not just physical contact with pollution but also a permanent attachment to it in the sense that the activity is understood to have traditionally provided the means of subsistence. People engaging in these occupations embody such impurity and pass it on genealogically so that collectively the pollution defining them as a distinct caste group is part of their corporeal substance. Even if a particular person in one of these castes does not engage in the traditional occupation, Kholagaun Chhetris still insisted that he or she still embodies the collective impurity of the caste through genealogical transmission.

If the body is the source and locus of impurity as the everyday transfiguration of attachment, food and water are its main conductors. Throughout Banaspati, the exchange of boiled rice (bhāt) and water is a way of practically constituting by word and deed hierarchical social relations among castes that are differentiated in terms of relative purity/impurity. Caste groups in Banaspati are characterized as ‘pāni chalcha jāt’ and ‘pāni nachalcha jāt’, that is ‘caste groups from whom drinking water is accepted for consumption’ and ‘caste groups from whom drinking water is not accepted for consumption’. Within the category of water acceptable castes groups there is a further division between ‘bhāt chalcha jāt’ and ‘bhāt nachalcha jāt’, that is, ‘castes from whom boiled rice is accepted for consumption’ and ‘castes from whom boiled rice is not accepted for consumption’. This categorization of caste groups in terms of water and food exchange tends to reflect Kholagaun Chhetris’ everyday practice with a high degree of accuracy. They accept boiled rice only from Chhetris and Brahmins, castes which they consider to be of purity equal to or greater than their own; they do not accept boiled rice from the Magar, Gurung, Tamang and Newar castes which they consider to be of less purity; and they do not accept drinking water from Untouchable caste groups—Washerman, Tailor, Blacksmith, Leatherworker—which they consider to be even less pure, largely because of their association with impure occupations.

For Kholagaun Chhetris, impurity is dangerous because it is transferable through food, water or contact with bodily effluvia and this has consequences for social relations (see Höfer 1979:52). A recurrent theme of their everyday interactions with people from outside their domestic compounds is the social and spatial restrictions upon whom one can eat with, whom one can marry, whom one can touch, whose house one is allowed to enter, who can cook and eat in one’s kitchen, and from whom one can accept water and cooked rice.

The Curse of Witches (Boksi)

The evil of witches is a second way in which attachment is experienced and known in everyday life. Boksis are people who have chosen to learn the knowledge (bidya)8 of cursing and causing harm (bigar pārne), usually from another witch. A boksi can be male or female but in my discussions with Kholagaun Chhetris about specific cases of illness and harm that they thought were caused by them, the boksi identified or suspected was always a woman. I can give a personal example. Early on in my fieldwork, I became very ill with a high fever. A Chhetri from next door came to my bedroom to see how I was. After hearing my description of the symptoms, he took hold of my wrist to feel my pulse. After a moment he shook his head with concern and muttered, ‘It’s a boksi [that caused your illness] … remember a couple of days ago, you sheltered from the rain in Mahila’s house and took some tea’ [implying that it was Mahila’s wife who was the boksi that cursed me while I was there drinking tea].

This example is typical of the pattern that it is not just women but in-marrying wives who are the usual suspects. It is one of the ways in which the dualistic Hindu [tantric] cosmology—the female principle in the form of the goddess Devi or the female form of cosmic power (shakti) is the active and creative dynamic of the universe that animates the male principle in which all existence is potential but un-manifested—informs everyday life. For Kholagaun Chhetris, and Chhetris more generally (see Bennett 1983 and Kondos 2004), women embody this shakti ambiguously in their procreativity and sexuality. As procreative power, shakti can be used beneficially by a faithful wife of selfless sexuality to bear children for her husband and thereby contribute to the continuance of his patriline. Kholagaun Chhetris usually mentioned the divine Sita, wife of Lord Ram, as exemplary of the beautiful, pious and loyal wife of controlled sexuality. She typifies the disciplined good life of the Householder combining procreative plenitude in the birth of sons with detachment from excessive sexual passion (Madan 1987:3). But when shakti is uncontrolled or undisciplined, it can also be used maliciously to cause disruptions in social relations, sickness and death.

Given this ambiguity of women and their shakti, marriage for Kholagaun Chhetris is both joyous and risky. Their marriage rules enjoin them to arrange marriages for their sons with women who are from other Chhetri lineages, with whom they have no existing kinship relations, and who reside outside Banaspati. After marriage the bride usually lives with her husband and his household group. As an outsider, a wife is seen to have the potential to improperly use her shakti as uncontrolled or excessive sexual passion—one of the primary human attributes that causes too much attachment to the world—to drain her husband of his semen and his vigour so that he wastes away. If relations between a man and his father, mother and/or brothers in a joint family household group become strained for whatever reason—the most likely being the distribution of common household resources—his wife may be suspected of using her sexuality to entrap him in an exaggerated attachment to her and the children she bears him so that his devotion is diverted away from his parents and the common good of the household group. If her shakti remains undisciplined and her husband remains loyal to his parents, she may choose to learn the knowledge of a boksi and use her power to curse and kill her husband or her son who is her husband reborn.

Kholagaun Chhetris characterized boksis as thoroughly evil beings, ‘consumed by spite and anger’ with ‘no mercy’ and with ‘desire only to cause harm and loss’. They cause illness and death in a number of ways: by sprinkling ash and saying powerful mantras over food intended for the victim; by saying a mantra over something from the intended victim’s body, such as nail or hair clippings or articles of clothing; by separating their spirit from their bodies during their sleep enabling them to enter a house whose window and doors are securely locked and to possess the sleeping victim (boksi lagyo); or just by looking at (karab najar [evil sight]) someone who is eating or the food they are eating. The danger is one of both visual and physical access to the victim’s body by witches whose evil glance or ritual actions over food that the intended victim will consume or things he or she have discarded from the body can cause harm, loss, sickness and even death.

The Harm of Disembodied Ghosts

Outside the compound wall and lingering at any intersection of two paths or roads (dobāto) are harmful and malevolent ghosts who cause sickness and occasionally death. They are disembodied spirits of deceased humans who remained attached to the world even after death; they wander around the village between dusk and dawn attacking people who happen to be passing by. Many house compounds have short paths from the courtyard gate that meet main path or road; these small junctions are considered crossroads where malevolent ghosts lurk not far outside the domestic mandala.

There are several names for such evil spirits and when pressed by my enquiries people of Kholagaun tended to differentiate them in terms of the manner of their living and dying. Pret, pichas and kāncho bāyu, are spirits of people who died by accident, suicide or witchcraft; bhut are the ghosts of grave sinners—thieves and murderers; kiche kandi are ghosts of women who died in childbirth; and masān are spirits of the graveyard where the un-cremated are buried. What is common to all of these ghosts, and why they are lumped together in the common binomial, ‘bhut-pret’, is that they are spirits of people who died inauspicious deaths. They did not die of old age after the contentment of fulfilling their lives as Householders. Instead their deaths were caused by drowning, suffocation, suicide, childbirth, punishment for crimes and sins, or witchcraft. As a result, villagers said that such people’s spirits are embittered by the premature curtailment of their earthly lives; they do not accept death because they were not ready to give up their attachment to worldly things and relations and they continue that attachment by lingering in the world of humans. This is how Kholagaun Chhetris explain why these disembodied spirits become ghosts and why they continue to exist in the world wandering around the village, forming dangerous attachments to people that cause diarrhoea, vomiting, loss of appetite, dizziness, worms, headaches, fever and sharp pains. The mode of attack is usually through possession, that is, becoming re-embodied in the victim’s body and people in a state of impurity are more vulnerable to possession by them.

The bitterness of these ghosts is exacerbated by the fact that cremation and other mortuary rites are not usually performed for those who died inauspiciously; and even if they are performed they are usually not effective in transforming the deceased into an ancestor spirit (pitṛ). For those who die naturally, cremation is a process of disembodiment that releases the person’s spirit. The mourning rites (kriya and śrāddha) performed toward the spirit by close kin remove the pollution and inauspiciousness caused by death and re-embody the spirit in sacred rice ball (pinda) offerings. In this re-embodied state, the spirit becomes an ancestor who lives in the realm of the ancestors (pitrilok). Each year, adult men perform a rite called Solah Shraddha in which they make offerings of rice balls to ‘all their deceased relatives’9 both as a act of remembrance and as a means of maintaining their embodied state. This is why one of the most common cures for illnesses caused by bhut-pret is an offering of food as a form of embodiment and attachment to the world. The danger here is the location of human actions to avoid attacks by these disembodied ghosts of moral disorder lurking on the public thoroughfares just outside the domestic mandala.

Purity and Danger

Despite the apparent differences between the dangers of impurity, the curses of witches and the attacks of disembodied ghosts, they all are similar in two respects. First, the dangers they pose to humans are the result of bodily corruption indicative of excessive or abnormal attachment to the world. For lower castes, it is their traditional and genealogically transmitted (if not actual) occupational contact with, and necessary attachment to, products of body processes that causes their permanent and collective impurity. For boksi, it is their uncontrolled shakti, manifest is their undisciplined sexuality and exaggerated attachment to their children, that provides the power to curse, cause illness, misfortune and sometimes death. For ghosts, it is their lingering attachment to the world and their disembodied interstitial state between an embodied human and an embodied ancestor that motivates them to attack people by possessing their bodies in the hope of re-embodiment through food offerings. Second, their dangers are wrought upon people’s bodies and cause disruption of social relations through the media of food consumed by the victim and/or through contact with the body of the victim. The impurity of lower caste people is contagious by touch so that either bodily contact or contact with food during preparation or consumption pollutes the body of higher caste people. The curses of witches are effected through sight in the form of the evil eye, access to the victim’s body in the form of possession or evil rituals performed over the leaving of the victim’s body or food to be consumed by the victim. Disembodied ghosts attack their victims through possessing their bodies during times when (dusk and dawn) and places where (crossing paths or roads) they roam.

Such an extended and elaborate ensemble of beings, whose dangers derive from excessive attachment to the world and are transmitted through food and physical contact, renders the preparations and consumption of food not just nutritionally essential but also socially sensitive and cosmologically significant. As I describe in the following section, it is through the patterns of including and excluding people from the various locations where food is prepared and eaten that Kholagaun Chhetris protect themselves and their food from the dangers of low caste people, the curses of witches and attacks of disembodied ghosts and, at the same time, build the domestic compound into a configuration of concentric zones around the kitchen as the centre of a mandala.

Dwelling, Mapping, Building

Up to this point in the chapter, I have identified four aspects of Kholagaun Chhetris’ dwelling in their houses and surrounding compounds. First, the bodily corruption that causes the impurity of lower castes, enables evil witches to curse and motivates the attacks of disembodied ghosts is, in each case, an everyday transfiguration of excessive and illusory attachment to the diversity of beings and things in the world. Second, the media through which these dangers are inflicted upon victims are food and body. In this sense, when they feel impure through contact with or consuming food prepared by people of lower castes, when they become ill through the curse of witches who have seen them eat or cursed their food, or when they suffer from attacks of disembodied ghosts possessing them, it is a moment when excessive attachment is embodied and turned into a permanent and tacit disposition of feeling, thinking and acting towards people and things in their world (Bourdieu 1977:93-94). Third, these dangerous beings originate, live and/or exist outside the domestic compound; but there are contexts in which they enter it: people of Damai (Tailor) and Kami (Blacksmith) castes come into the compound to make clothes and repair utensils; women from other villages and clans marry into the household group, become members and have access to the most vulnerable places in the house; and ghosts linger at the crossings of roads and paths outside the compound but they can also slip through the cracks in windows and doors to possess people in their sleep. Fourth and consequently, food, its preparation and consumption needs to be surrounded by spatial and social prohibitions that protect people from these impure and dangerous beings.

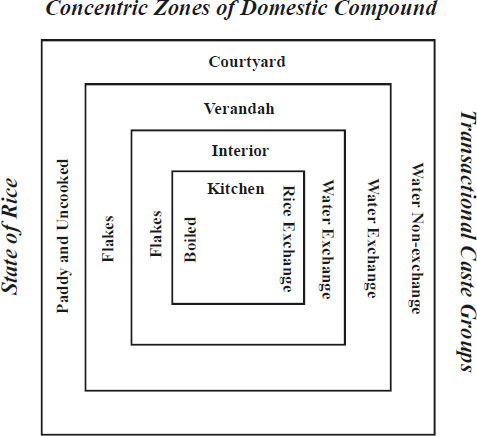

We are now in the position to understand how Kholagaun Chhetris map the cosmos onto their domestic compounds and build them into concentric mandalas with the kitchen at the centre. Unlike the mapping of cartographers using pictures, words and symbols to represent a place (Casey 2002:131ff), the kind of mapping that I am referring to here involves objects, actions and their locations. In the following I will illustrated this dwelling, mapping, and building by Kholagaun Chhetris through analysing the locations within the compound where they prepare and consume rice in its different states from raw to cooked and the patterns of inclusion and exclusion of people from these locations (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 The domestic mandala in the concentric configuration

Courtyard (Āgan)10

A common sight in autumn after the harvest of rice and maize is a man sitting on the ground in the middle of the courtyard with his portable sewing machine making new clothes for the members of the resident Kholagaun Chhetri household group to wear for the upcoming celebration of Dassain, the most important festival in Nepal. Tailoring is associated with a particular occupational caste, Damai, whose members are considered impure and untouchable (water unacceptable castes) by Chhetris and other high castes. Kholagaun Chhetris do not allow Tailors inside the house. So, while the Tailor is in the courtyard making clothes, he beckons several family members to come out of the house into the courtyard for measurements. Near the verandah, maize is drying in the sun on straw mats (sukul) and an adult woman of the household group is sitting on the ground winnowing the remaining chaff from rice that will be stored in large vessels in the house for use in cooking over the next week.

This vignette constructed from my fieldnotes displays the major activities that take place in the courtyard and that configure it as the outermost concentric zone of the domestic mandala. It is the space most visible from outside the low boundary wall and most vulnerable to the impurity and dangers of people and beings from outside the compound. The courtyard is the place where raw grains are dried or processed. When rice is harvested in autumn, it is threshed in the fields and brought to the house as unhusked paddy, a distinct state of rice which in Nepali is separately designated by the word dhan. Paddy is dried in the sun for a least one day before milling, otherwise it would be difficult to cook. Once milled to remove the chaff, rice is in the next stage of its transformation into food. The white rice grains are called chāmal and rice in this state is still considered raw because it is uncooked. The courtyard is the place where it is winnowed to remove the remaining chaff before cooking. (The same happens with wheat grown over the winter; in spring it is winnowed and dried in the courtyard.) While drying in the sun or being winnowed, the grains are considered raw because they have not been subjected to human actions which corrupt their wholeness by transgressing their boundary. It is in the process of cooking that the grains become vulnerable to the impurity of lower castes and the curses of witches and attractive to disembodied ghosts. Since there is no cooking process, raw or uncooked food is least vulnerable to impurity and danger and thus is the most socially exchangeable.

Because raw grain is immune from impurity and danger, there are few, if any, protective spatial exclusions. The courtyard is the place where anyone is allowed to enter relatively freely. In this respect the courtyard is the only place where members of untouchable castes can enter, as the case of the Tailor making clothes for Dassain illustrates. The reverse is also the case: Kholagaun Chhetris do not fear becoming impure by entering the courtyard of low caste people. There was one Tailor from another hamlet in Banaspati who made and repaired clothes for many Kholagaun Chhetris. When he came to a Kholagaun Chhetri house to pick up clothes for repair or cloth for making new garments or to work on new clothes, the interaction took place only in the courtyard. This Tailor, however, was a popular person; he was an entertaining conversationalist and humorist. On those occasions when a Kholagaun Chhetri brought clothes or cloth to the Tailor’s house, the interaction took place only in his courtyard. If another Chhetri happened by, he too would enter his courtyard and join the conversation. Kholagaun Chhetri men spent many pleasant hours there without becoming defiled by the Tailor; they ensured this by not accepting water or anything to eat.

Verandah (Pidi)

Another common sight in Kholagaun is the head of a household entertaining a relative, friend or neighbour on the verandah. Host and guest talk about village affairs sitting either on the raised platform at the end of the verandah or on a straw mat brought out especially for the occasion and spread out on the verandah floor.11 Usually, they are served tea and a snack of dry rice flakes (chyura, dry-popped maize, dry-fried soybeans or commercial biscuits by the household head’s wife. During the visit, she, and perhaps her daughter/s (and/or daughters-in-law if it is a large joint family household group), sit nearby on the floor of the verandah sorting, washing and chopping vegetables for the evening meal where they can hear the conversation and interject comments and observations about village life.

In this vignette, again constructed from my fieldnotes, the verandah mediates the visible courtyard and the invisible interior of the house. Since it runs across the front of the house which faces into the courtyard, it is, like the courtyard, visible from outside the boundary. But like the house interior, the verandah is also a raised area above the courtyard on the same level as the house’s ground floor and it is covered by a roof. Its architecturally mediating character is matched by its use as a socially mediating space between the public courtyard and the more secluded house interior. In traditional houses, there is often a raised wooden platform at one end of the verandah that people use for sitting in the sun and entertaining guests (see Figure 4.2) accompanied by snacks; in modern houses, either chairs or a grass mat are brought out for host and guest. In terms of spatial inclusions and exclusions, the visitors and guests entertained by Kholagaun Chhetris on their verandahs are most often people of equivalent purity. They sometimes sit and talk with people of lower castes from whom they will accept water but snacks are not offered. People of untouchable castes (from whom they will not accept water) are usually not allowed on the verandah, particularly when snacks are being served.

Figure 4.2 Verandah of a traditional house (with raised seating platform on far left)

These spatial inclusions and exclusions are imposed because the method of preparing the snacks makes them more susceptible than raw paddy to impurity and danger. Snacks are prepared inside the house where, in the process of converting raw grain into an edible state, the food, the preparer and the cooking process are out of sight and touch of people in courtyard and on the verandah. The most common snack is tea served with a small metal bowl of chyura, raw milled rice (chamal) that has been boiled, then roasted and finally pounded into rice flakes. Chyura is made in large batches once or twice each year and stored; it can also be purchased in the local shops. When offered for snacks, the dry rice flakes are served in a small metal bowl. Alternately, dry-popped maize, dry-roasted soybean or commercially made biscuits are served with tea.

Because of their method of preparation, chyura and other snacks are susceptible to impurity and danger, but less so then other forms of cooked food. When rice or other grains are cooked, they are placed in a medium—either water, oil or air (dry)—and heated over a fire rendering them porous, that is, the boundary of the grain becomes permeable and open to absorbing the qualities of the medium in which it is being cooked. The medium absorbs and conducts to the food the impurities and dangers of anyone who touches or sees the grain with evil intent during its transformation from raw to cooked. Different cooking media have different potentials for absorbing and conducting: water is the most, air the least and oil in between. The snacks served on the verandah are doubly shielded. First, they are cooked inside the house out of touch of low caste people who might be in the courtyard, inaccessible so that substances from the intended victim’s body that witches use for cursing cannot be introduced into the food, and out of sight of any disembodied spirits lurking just outside the boundary wall. Second, they are cooked and served dry (sukha). Chyura, though previously boiled, fried in oil and pounded into dry flakes, is not considered as vulnerable as boiled rice to impurity because it is stored and then served dry to guests without further cooking or preparation. Raw maize and soybean grains are dry-heated in a pan over a fire without any water or oil. This is a method of cooking that does not involve a conductive medium through which impurity and danger can be absorbed. Once cooked, then, chyura, dry-popped maize and dry-roasted soybeans are relatively invulnerable to absorbing impurity or being affected by the evil eye of witches and are less attractive to disembodied spirits outside the compound. Commercial biscuits have similar qualities to chyura: while the original cooking may have involved water or oil as a medium, they are stored out of sight or physical access and have the quality of dryness because they are not boiled in water or cooked in oil just before serving them to guests.

Compared to the courtyard, the verandah is more ‘interior’. By this I am referring to the increasing need to protect the purity of food with spatial exclusions upon people from outside the household group because the rice snack served is cooked and more vulnerable to impurity and danger than the raw grains dried and winnowed in the courtyard.

Inside the House

There are four basic types of rooms or spaces for four basic types of domestic activities that make up the interior layout of both traditional and modern houses: cooking, sleeping, worshipping deities and storing valuables. No matter what variations there are in the architectural locations of these rooms or spaces in Kholagaun Chhetri houses, the interior house space itself is organized into two increasingly central zones that complete the domestic mandala.

Sleeping Rooms

Sleeping rooms serve as indoor entertaining rooms equivalent to the verandah in terms of food served and people allowed to enter (see Figure 4.3). Throughout my fieldwork, Kholagaun Chhetris often invited my and my Nepali friend/assistant into their sleeping room. On one of these occasions, we were in one of the sleeping rooms in the house of Hari, who described its use as follows:

No one sleeps in this room permanently. This is where guests who are not from Kholagaun sleep; I also entertain them in this room during the day. Occasionally, I entertain guests from Kholagaun in this room but usually they [guests from Kholagaun] sit on the verandah with me. Main meals [in which boiled rice is served] are not eaten in this room or any other sleeping room; main meals are eaten only in the kitchen unless someone is too sick to come to the kitchen to eat. While entertaining guests, snacks, usually consisting of tea and rice flakes, are eaten in this room.

Note here that the same snacks are served to guests in the sleeping rooms as guests on the verandah for the same two reasons: they are prepared inside and they are dry-cooked and served so that they are less vulnerable than boiled rice to the impurity of the cook or cursing by witches.

It was during one of my earlier fieldtrips that I spoke with Hari about the layout of his house. I asked who was allowed to enter the sleeping rooms. He said, ‘anyone from the water acceptable castes’; the implied converse of this was that people of the water unacceptable castes—Tailors, Blacksmiths, Leatherworkers and Washermen—are not allowed to enter this zone of the domestic mandala. This was confirmed in 2001 by another Kholagaun Chhetri, Ram, who had recently built a new house. We were invited to his sleeping room for the our conversation about the layout of his house and spatial prohibitions he practiced. I asked him the negative form of the question I had asked Hari many years earlier: ‘Who is not allowed to enter the bedrooms in your house?’ Ram gave an answer that confirmed the one given by Hari: ‘People from the water unacceptable castes.’

Figure 4.3 Sleeping/entertaining room in a traditional house

I had a personal experience of this prohibition. For one of our stays in Banaspati, we rented a modern house near Kholagaun from a Chhetri man, Ram Prasad. He and his household group (wife, unmarried young children and his wife’s mother) normally lived in this house; they vacated it and moved to their older traditional house nearby so they could collect rent from us. Several times during fieldwork we invited Tailors and Blacksmiths, two of the water unacceptable castes, into one of the interior rooms where we talked with them about their position in and views about the hierarchy of castes in the village. Ram Prasad’s mother-in-law maintained a vegetable garden in small plot adjoining our house; she tended it most days giving her a chance to keep in eye on us and who we allowed in the house. On those occasions when we invited Tailors and Blacksmiths inside, she would work in the garden and grumble under her breath but just loud enough for us to hear her displeasure. At the end fieldwork as we were packing up the truck with our goods and equipment to take us back to Kathmandu, a Brahmin priest hired by Ram Prasad arrived to begin a major purification ceremony upon the house to rid it of the impurity that we had allowed inside.

In relation to the verandah, the sleeping rooms are the next interior zone. Even though it shares with the verandah the type of food served and the people allowed to enter, I have treated the sleeping rooms as a more interior concentric zone because it is inside the house where people, their guests and their activities are not visible from the verandah, courtyard or beyond the boundary wall. Anyone sitting and eating snacks on the verandah is visible to people who have been invited into the courtyard as well as to anyone who is walking along the path outside the courtyard. Second, I have not included the storeroom and worship room in this zone. These spaces are foregrounded in the yantric configuration where their orientation to Hindu sacred geography is crucial for their auspiciousness as a location for activities concerning prosperity and worship within a house. They, like the yantric configuration itself, are in the background when the concentric mandala is in the foreground during domestic activities concerning food and its protection from impurity and danger.

Kitchen (Chula)

Evening and the household group has come together for a meal on the raised mud area that demarcates the kitchen of a traditional house. All are barefoot. The household head, his married son and unmarried grandson are squatting on wooden platforms, each with a separate brass plate of food; they mix some boiled rice, lentil broth and curry in their right hand before putting it in their mouths. The meal is eaten rather quickly with only sporadic conversation about events of the day or requests for more food or water. The wives of the household head and his son do not eat with them as this would put them in an impure state and they would be unable to serve them and refill their plates. Only after the men have finished and removed the impurity of eating by washing their hands and mouth do their wives serve themselves and eat.

Kholagaun Chhetris usually eat two main meals each day, usually consisting of lentil broth (dal), a curry of vegetables and/or meat (tarkari) and rice cooked in water (bhat). Water is the most transitive medium because it readily absorbs the character of any object with which it comes into contact. As a result, it can purify as well as pollute. In purificatory bathing, water flows over the object or person, absorbs the pollution and takes it away into the ground. Conversely, while it is boiling, rice sits in water which conducts the state of the cook or the curse of a witch to the permeable rice.

Because of food’s openness to absorption, cooking and eating in the kitchen are dominated as much by an explicit concern with protecting the purity of the food, the people who eat it and the place where it is cooked and eaten as by the practical tasks of preparing food and consuming it.12 The kitchen in traditional houses consists of an earthen stove in the corner of a raised earthen platform (see Figure 2.9). Women told me that mud is a very absorptive surface that is particularly prone to pollution from eating—bits of food made impure by saliva may fall on the ground—so they must sweep and seal the floor with a purifying mixture of cow dung and water after every meal. In some modern houses, where the kitchen is a separate room with floors of less or non-absorptive concrete, marble or other hard surfaces, the floor need only be washed with water after each meal to remove impurity (see Figure 4.4).

The kitchen has the most exclusive spatial prohibitions. Over the years of my fieldwork in Banaspati, Kholagaun Chhetris consistently told me that only Brahmins and other Chhetris, the castes from whom they will accept cooked rice, were allowed to enter their kitchens when meals were being prepared and eaten. People of the water-acceptable castes were allowed to enter the verandah while Chhetris were eating; they were occasionally allowed to come just inside the main entrance to ask a question but they could not enter the kitchen. I was told that when food was not being prepared or eaten people of water-acceptable castes could enter the kitchen, but I never saw this happen. Untouchables (water-unacceptable castes) could not even enter the house of a Kholagaun Chhetri without causing defilement of all the living spaces, public and private. Thus whenever an Untouchable wanted to interact with a Kholagaun Chhetri, he or she had to remain in the courtyard and call out to the householder.

The threat, however, is not just from people of lower, impure castes. The following is an extract from my discussion with Hari on the danger of the curse of witches:

On Thursday while Hari was eating his meal in the kitchen area on the ground floor, a couple of married Chhetri women from Kholagaun entered his house through the main entrance. Since they did not try to talk to him, he assumed that they had come to visit his wife. For a while they waited near the kitchen area where Hari was eating. The next day while he was working in his office, Hari began to have attacks of diarrhoea. He took some ‘doctor’s medicine straight away and continued the medication on the following day as well, but this did not cure him of the diarrhoea. The diarrhoea continued and two days later he consulted with a lineage, Mohan Bahadur, mate who was reputed to be a ‘very religious man’ who knew about dealing with sickness ‘caused by other people’, that is, witches [boksis]. He called Mohan Bahadur because he became suspicious about the cause of his diarrhoea; he thought it might be connected with the women watching him eat several days earlier. He told me: ‘It’s not good to have people watch you eat when they are not partaking of the meal themselves.’ When Mohan Bahadur arrived, the first thing he did was take Hari’s wrist and feel his pulse [the typical technique for diagnosing sickness caused by witches and the one used on me]. After feeling the pulse for a few minutes, Mohan Bahadur said something was ‘bigreko’ [‘broken’, the word used to indicate that the curse of a witch has caused some malfunction or sickness in the body of the patient]. Mohan Bahadur prescribed some medicine and chants but they too were ineffective in curing the diarrhoea.

Hari’s description of these events indicates the susceptibility to danger people feel while they are eating in the kitchen. It is the time when they are temporarily in an impure state; it is a time and place where they are most vulnerable to the impurity of others and to the evil eye or curses of witches and other people with evil intent brought about by jealousy—all everyday transfigurations of attachment. Such vulnerability is largely through visibility but also through access to the body of the victim.

Figure 4.4 Kitchen in a modern house

Compared with the courtyard, verandah, and sleeping rooms, the kitchen is the most interior of domestic spaces. For Kholagaun Chhetris, it is the room where their food and their bodies are most vulnerable to impurity and danger so they do their utmost to ensure it is pure by locating it in the most inaccessible place, purifying it before and after eating and imposing the most exclusive spatial prohibitions on people entering it. Taken together, courtyard, verandah, sleeping rooms and kitchen form a concentric series of increasingly exclusive interior spaces where rice and the people eating it are increasingly vulnerable to impurity and danger, and where maintaining and protecting purity is increasingly important.

Everyday Practice, Cognitive Knowledge and Embodied Revelation

What I have tried to illustrate thus far is that among Kholagaun Chhetris, the Hindu [tantric] concern with equivalences between various planes of existence means that the activities of everyday domestic life and the places where they take place are multifaceted—corporeal, social and cosmological. Eating nourishes the organic body, pollutes the social person, and is an embodied experience of a Householder’s attachment, illusion and the entrapments of life-in-the-world; washing after eating cleans the body, cleanses the social persona of impurity and is the embodied experience of detachment and renunciation so central to balancing the attachments of the Householder’s life-in-the-world. Concomitantly, in carrying out these activities Kholagaun Chhetris define distinct multifaceted concentric spaces in their house—at once functional, social and cosmological—that form a mandala. Their houses likewise are multifaceted: they are places to live their daily lives, they are maps of the cosmos, and they are machines for revelatory knowledge.

The wall surrounding the compound demarcates the interior of the domestic mandala from its dangerous exterior. Inside and outside of the mandala are mutually constituting so that the nature of these exterior dangers simultaneously produces the interior of the domestic compound, its spaces and the people who reside in it and vice-versa. As we have seen, outside the wall of the compound is a zone of danger of three kinds: the impurity of people of lower castes who pollute through physical contact, the evil of witches who curse through visible or physical access to the victim’s food or body, and the harm of disembodied ghosts who attack through possessing the body of the victim. Each of these dangers and the spatial prohibitions that Kholagaun Chhetris impose to limit physical and visual access to outsiders constitutes the series of interiors culminating in the kitchen as the most vulnerable in the house. Each of these is an everyday transfiguration of the danger of excessive attachment to the world and the resulting illusion that entraps people in the round of death and rebirth. The actions Kholagaun Chhetris take to protect them from such externally-located dangers reciprocally define the kitchen as the pure interior of the house as well the place for the experience of detachment that makes it the centre of a mandala.

Not just a map of the cosmos, the domestic mandala is also an instrument for gaining knowledge of its fundamental principles, ‘a machine to stimulate inner visualization’ (Zimmer 1972:141). As I argued in the opening chapter, both contemplation of and action in a mandala can be revelatory of the transcendent truths of the cosmos through inward and outward movements of the eye or the body in relation to the centre. Likewise, Kholagaun Chhetris’ dwelling entails moving in the domestic mandala, from inside out and from outside in, as they carry out their everyday projects of processing grain, entertaining guests, cooking food, eating meals. Through these movements and the spatial inclusions and exclusions that accompany them, the enigma of their Householder way of life—the simultaneous contradiction and complementarity of attachment and detachment (Madan 1987:10)—is ‘realized, embodied, turned into a permanent disposition, a durable manner…of feeling and thinking’ (Bourdieu 1977:93-94) and, I might add following Polanyi (1962), of tacitly knowing.

Notes

1 One of the common blessings received from gods in return is a prosperous life.

2 As I described in Chapter 1, this enigma is an explicit part of a boy’s rite of passage (Bartaman) when he enacts detachment in the life of the celibate student (Brahamachārya)—learning the religious texts from a guru, abstaining from sex and begging for food—just prior to and as a condition for entering the Householder’s life of attachment to family, land and deities.

3 This same enigma is reiterated in the four stages of life. The Householder stage (grihastha) with its passions and attachments is chronologically bracketed and morally encompassed by the other three stages of life—the Brahmacharya stage preceding it and the Vanaprastha and Sannyasin stages following it—characterized by asceticism, detachment and renunciation

4 People in Kholagaun used the Nepali term ‘sansar’ to refer to the material world and this was distinguished from the Nepali term ‘lok’ which, while translatable as world, refers more to a realm of existence that includes beings as well as their media and mode of being in it. Thus, after death, ancestors (pitri) reside in another realm of existence (pitrilok) until they are reborn into the human realm (martyalok).

5 In formal ritual contexts, Kholagaun Chhetris mimic their household priests in using the more sankritized words of ‘shuddha’ for purity and ‘ashuddha’ for impurity.

6 As a left-handed person, I was constantly getting myself into impurity trouble during meals. Kholagaun Chhetris, like most Nepalis, eat with their auspicious right hand; during a meal when the right hand is polluted, the left hand remains unpolluted and can be used to pass food to another without transferring impurity. I would usually try to adopt the right handedness of eating; but as the meal progressed and conversation flowed, I would usually unknowingly switch to using my left hand and for eating, thus making both hands impure and socially immobilising me from passing food.

7 In being about substances that flow from inside the body to outside, these sources of pollution are a physical manifestation of Merleau-Ponty’s main premise about ‘bodily space’ (1962:115): the incarnate intentionality of the body, that is, body and world are internally related, they are two dimensions of a single phenomenon.

8 Note the use of the term bidya rather than gyan (religious knowledge).

9 Bennett (1983:119) provides a list of the extensive categories of kin who may be remembered in Solah Shraddhya.

10 As we will see in Chapter 5, a number of rituals—rites of passage—take place in the courtyard involving sacrificial offerings to a fire (hom). At some point during these rituals, an offering is taken outside and placed on the path leading to the courtyard. This offering is for the disembodied ghosts lurking outside the courtyard. The offering is meant to satisfy the ghosts so they are not drawn into the courtyard by the food offerings being made to the gods in the sacrifice or other rituals.

11 Sometimes if it is raining, they will slip inside the house and sit in a bedroom or around the agena fire pit to keep warm.

12 Daryn found that ‘the process of cooking and consuming Thamghar’s main staple [boiled rice] is deemed highly perilous. This is the reason why it must be confined to the dim and hidden interior of the ground floor of the house, away from the potentially malignant gaze of fellow villagers…’ (Daryn 2002: 30-1).