The Auspicious House: Materials, Design and Orientation

‘The practical application of Vastu is yantric in nature.’

D. N. Shukla, Vastu Sastra: Hindu Science of Architecture

At its fullest elaboration, vastu architecture is modernist, particularly in the highly reflexive use of the vastu purusha mandala as a totalising master plan for all aspects of a house—from the major architectural features of exterior form and interior layout down to the smallest detail of the use of colour and the placement of furniture—as ‘a machine for living in’ (Le Corbusier) harmony with the cosmos; and remember the term ‘yantra’ means machine. The problem with modernist architecture is that it assumes a one-way relation between design and use and ‘precise congruence between activities and architecture’ (Rapoport 1990:18).1 Kholagaun Chhetris are not modernist in this sense. They do not deliberately plan, consciously conceptualize, or verbally describe their houses as mandalas. Instead they are ‘vastu architects’ by conventional practice rather than by intentional design, building both their lifeworld and the spaces for it through the everyday use of their houses. They produce their houses as mandalas in the way they orient them auspiciously in terms of the cardinal directions and organize them into a series of concentric zones of increasing purity and vulnerability to the dangers outside their compounds.

In turning now to the ethnographic dimensions of how Kholagaun Chhetris praxically build their houses as mandalas over this and the following chapters, I draw upon the results of the previous chapter where I identified two configurations of space immanent in the complex mandala form and described how each is a way of conceptualising space and iterating cosmological themes. One is the yantric four-sided polygon. Its diacritical feature is its orientation to the cardinal directions of Hindu sacred geography—including their presiding deities and realms of power—that anticipates auspiciousness and harmony between the human and cosmic orders of reality as a condition for worldly prosperity. The other is the mandalic configuration of dynamic concentric spaces around a centre point in which corporeal movement is essential and productive: the movement inward of knowledge of the fundamental and transcendent unity of the cosmos and liberation or release (moksha) from rebirth into the world; movement outward of worldly creation, illusion (maya) and rebirth into the world (samsara). Its diacritical feature is its orientation to the centre that anticipates knowledge of the fundamental unity of the cosmos and the liberation that ensues.

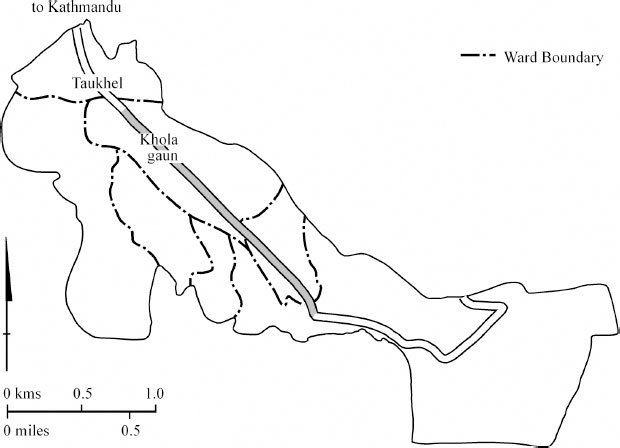

Map 2 Banaspati VDC (shaded strip marks area of Figure 2.1)

I have identified what I call the diacritical features of each spatial mode of the mandala because in looking at the building and use of houses in everyday life it is important to differentiate between the precise geometry of the designs and the geometric relations that are their essence: that is, to distinguish between the absolute geometric locations of design elements as determined by systems of exact measurement and the abstract, culturally emphasized geometric relations between elements expressed through such precise quantitative measuring. For conventional practitioners of vastu, it is the latter that are active in conveying cosmological meanings. In this respect, every architectural space is not and need not be consciously oriented toward specific cardinal directions for the Kholagaun Chhetri house to be a yantra. Instead, a principal architectural feature—for houses in Kholagaun it is the main entrance—is the only one that needs to be oriented explicitly by the sacred geography of the mandala; other spaces in the house and compound are located relative to the main entrance so that the whole takes on the yantric orientation toward the geographic directions. Similarly, as I show in Chapter 4, the centre of a house does not have to be located in the precisely-measured, absolute geometric centre of the physical structure. Instead, the centre of a Kholagaun Chhetri house—the kitchen where food is prepared and eaten—is determined culturally and relationally in terms of its vulnerability to the dangerous character of people and things that are deemed by Kholagaun Chhetris to inhabit the concentric zones surrounding it.

The Hamlet of Kholagaun

The hamlet (gāun) of Kholagaun is a recognized and named residential area within the government village (VDC) of Banaspati. Banaspati is situated in the southern area of the Kathmandu Valley approximately 15 km from the capital. Most of the houses comprising Kholagaun are situated on a plateau of higher ground along a 1.25 km stretch of the main road from Kathmandu which in this part of the village runs in a north-west to south-east direction (see Map 2 and Figure 2.1). A short distance away from both sides of the road, the land drops off sharply into the terraced rice fields.

Figure 2.1 Banaspati VDC (looking towards the northwest)

Kholagaun is a hamlet of about approximately 100 household groups (pariwār).2 Two-thirds of these are members of a single named Chhetri agnatic lineage, Silwal; the other households in Kholagaun are from a variety of castes (jāt)—Brahmin, Chhetri, Khatri, Newar, Magar, Gharti, Sunar. Silwal Chhetri household groups vary in size and composition from single person households (2), to nuclear households of a husband, wife and unmarried children that may also include a widowed parent or sister of the household head (39), to complex joint-family households consisting of a man, his wife, married sons and/or brothers, sons’ and/or brothers’ wives and children and unmarried daughters (24). In most cases each household group occupies a separate house structure; but there is a number of instances in which a joint family has split to form two or more nuclear households groups that continue to occupy a single house even though they have separate land holdings and finances.3 In such cases, internal renovations have been carried out so that each household group has at least its own kitchen and cooking fire (chulā) in the house defining its separate status.

Before proceeding with a description of Kholagaun Chhetri houses, their yantric orientation, room layout and everyday domestic activities that take place within them, I introduce the notion of auspiciousness, both temporal and spatial, since this is a condition they seek to promote in their domestic mandalas.

Temporal and Spatial Auspiciousness

Auspiciousness (subha) is a condition of events that facilitates beneficial outcomes in everyday life. Events are auspicious when the time and place in which they occur are in harmonious relations with the cosmos; and harmonious relations with the cosmos promote favourable consequences—well-being, happiness and prosperity (samriddhi) in its widest sense—of people’s actions in those events. Kholagaun Chhetri houses exist in time and space and the harmonious relations between the cosmos and each of these dimensions of the house constitute distinct conditions for promoting the well-being and prosperity of its inhabitants.

Analyses of auspiciousness have usually been associated only with the harmonious or compatible timing of events. One of the major themes in Madan’s (1987) penetrating analysis of auspiciousness is that ‘the passage of time becomes significant through the conjunction or intersection of the trajectories of human lives and/or of such trajectories and the course of cosmic forces’ (1987:52). Pugh has linked the meaning of auspiciousness to the Hindu calendrical system and different annual cycles embedded in it. Like Madan, she sees auspiciousness ‘constituted in the junctures of times and actions which share a set of compatible features’ (1983:48). Yet, in building and living in a house, Kholagaun Chhetris are just as concerned with establishing harmonious relation with the sweep of cosmic space as they are with the flow of cosmic time.

Temporal Auspiciousness

One of the constant themes of everyday life in Kholagaun is determining auspicious times (sāyat) for engaging in major activities, beginning projects such as the stages of building a house, embarking on journeys, and performing important rituals so that beneficial outcomes are realized and no harm is experienced. Kholagaun Chhetris explain the occurrence of good and bad fortune in their lives in relation to the movement of the astral bodies or planets (graha). For example:

If something bad happens to you, it is because it is a bad day (din bigriyo or dasā lāgyo); throughout a person’s life, days may be auspicious or inauspicious, good (rāmro) or bad (narāmro), according to the position of the planets relative to their position at the time of birth.

This planetary effect provides each villager with a sense of his or her own individuality as a person with a unique life. When a child is born, the household priest constructs an astrological chart based upon the position of the planets at the precise moment of birth. This chart uniquely places the child within the flow of time in the cosmos and this is the basis of his or her unique personal characteristics and trajectory of life. The child’s name is derived from the position of the planets at the time of birth as represented in the horoscope. Through their own names, then, Kholagaun Chhetris establish a direct link between the individuality of a person’s character and fate—their social being in the world—and the cosmos through their unique place in the flow of cosmic time as measured by movement of the planets.

Table 2.1 Association of planets with human attributes (Pugh 1983b: 141)

Planet |

Day of the week |

Human quality |

Sun |

Aitabar (Sunday) |

fame, success, health |

Moon |

Sombar (Monday) |

love, pleasure, fertility |

Mars |

Manglebar (Tuesday) |

conflict, persistence |

Mercury |

Budhibar (Wednesday) |

intelligence, flexibility |

Venus |

Sukrabar (Friday) |

beauty, passion |

Jupiter |

Brihaspatibar/Bihibar (Thursday) |

wisdom, devoutness |

Saturn |

Sānibar (Saturday) |

sadness, destruction |

By itself, a person’s cosmically-influenced personality and life trajectory is not auspicious or inauspicious. As Madan and Pugh emphasize, auspiciousness and inauspiciousness are about the quality of the juncture of events. Since the nature of events is that they occur in time, the condition of auspiciousness derives from the relation between events mediated by the flow of time. The flow of time is given a substantive character by being measured and represented by the movement of the nine astral bodies (nau-graha). Seven of these are planets: sun (Surya), moon (Chandra/Som), Jupiter (Brihaspati), Venus (Sukra), Saturn (Sāni), Mercury (Budha), and Mars (Scanda/Mangal); two are the ascending (Rāhu) and descending (Ketu) modes of the moon and are associated with eclipses and inauspiciousness (Freed and Freed 1998:20-21).4 The planets objectify the cosmos. They materialize the forces of nature and the attributes of humans (see Table 2.1) which imbue and mark the flows of time: the seasons, lunar months, days of the week. The planets’ association with and influence upon the flow of time is particularly evident in the days of the week; each is named and presided over by one of the planets. Because events occur in time, they are infused with the character of the time of their occurrence which is determined by the position of the planets. In Nepal, astrological books (patra) are published monthly; they set out the position of the planets and provide guidelines for interpreting the influence of the planets upon the everyday life of individuals.

Events are a complex configuration of actors, the actions they engage in, the particular time and place of the actions and the products of the actions, both social and material. Like the events themselves, these constituents of events are infused with the character of the encompassing events as determined by position of the planets at the time of their occurrence. One such event is birth. People in the world are a product of the event of birth. As we have just seen, a person’s unique character, qualities and trajectory of life is determined by the time of the event of birth and represented in a horoscope (kuṇḍali). Again, the event of birth and the influence of the planets on the person are not in themselves auspicious or inauspicious. It is the temporal conjunction of this event, including its influence on the person’s life trajectory, with other events that create the condition of auspiciousness or inauspiciousness. When planning a significant event—a journey, business venture, or important ritual—timing is everything for its auspiciousness in promoting well-being, happiness and prosperity. The character and life trajectory of the person mainly responsible for the event (derived from the position of the planets at the time and place of the event of birth) and position of the planets at the time and place of the planned event are compared to see if they are harmonious. If so, the planned event can proceed with the prospect of beneficial outcomes.

Another example of ensuring temporal auspiciousness is building houses. Throughout the building process, the timing various of the stages of construction is determined by concerns for auspiciousness. In Kholagaun, people consult their household priests who have the sufficient knowledge of Hindu astrology to calculate an auspicious time for beginning the digging of the foundation, when the house is born in cosmic time, for commencing laying the foundation, for first entering the completed house, and for living in the house. The priest interprets the astrological guide to gauge the compatibility of features (see Pugh 1983:48) between the horoscope of the person, based upon the planetary conditions at the time of birth, and the planetary conditions at the time of proposed house-construction events. If they are compatible, this is an auspicious condition indicating a harmonious relation between the particular juncture of person, the event and the cosmos that is conducive to the house having beneficial consequences for the person who will live in it. If they are incompatible, this is an inauspicious condition indicating a disharmonious relation between the particular juncture of person, the construction of the house and the cosmos. In such cases, the construction event will be rescheduled for another time.

What is evident in this brief discussion of auspiciousness is that it appears to be only a temporal phenomenon. It concerns the relation between humans and the cosmos mediated by the intersection of events in cosmic time. Since for Kholagaun Chhetris the flow of time is something that humans cannot control, people cannot engage in actions to make some thing auspicious as this would mean that auspiciousness is a quality of a thing or event rather the quality of its conjuncture with cosmic time. The only action humans can take in relation to auspiciousness is manipulating the timing of events, that is, their relation to cosmic time, so that the consequences are beneficial for them.

Spatial Auspiciousness

While Madan and Pugh have emphasized the temporal dimension of auspiciousness, I suggest it also has a parallel spatial dimension that is particularly evident with respect to buildings. As I have already mentioned, in Kholagaun the process of house building takes place according to calculations of auspicious times for various stages of construction. Yet, each of these auspiciously-timed stages is accompanied by the performance of rituals—the subject of the following chapter—concerned with establishing harmonious relations with the house’s spatial milieu that is being created by the construction. Some of these rituals are directed toward pleasing the deities associated with various dimensions of the house’s locale—the site, the ground, the cosmos—and they are crucial to building the house as an auspicious yantra. They are evidence of a spatial dimension of auspiciousness that concerns the relation between humans and the cosmos mediated by orientation in space.

If the planets and their movements represent the temporal dimension of the cosmos, then the cardinal directions represent its spatial dimension. Unlike Chakrabarti who described schemes in the Vastu Shastras for aligning the planets with the cardinal directions (1999:108),5 Kholagaun Chhetris and their household priests made no direct parallels and alignments between the nine planets and the eight cardinal directions. In this sense, they did not articulate an explicit and systematic way of moving from conceptions of auspicious timing of events to conceptions of auspicious spatializing of events. However, there are three aspects of Kholagaun Chhetris’ everyday practice of space and time allowing for auspiciousness to be constituted by temporal and spatial harmonious conjunctions of people and events. First, deities mediate time and space. Both the planets and the directions are conceived of as deities. The names of the planets, the astral bodies manifesting the cosmic flow of time, are also used by Kholagaun Chhetris as the names of deities so that the planets are themselves deities. Likewise, as we have seen in the previous chapter, each of the eight directions, the manifestation of the cosmic space, is associated with a particular deity so that the directions are themselves deities. As an example, in the ritual Satya Narayan puja, which many household groups conduct annually ‘for the auspiciousness and welfare of the house and its occupants’, one of the stages of the ritual involves building the pavilion (mandap) in the shape of an eight-pointed design (astadal) in the centre of which the god to be worshipped, Satya Narayan, will be installed. One important part of ritually building the pavilion is the make a clockwise circuit of offerings to each of the points of the astadal. Each point is explicitly associated with a direction and when making the offerings the name of a subsidiary deity is chanted, installing it as the guardian of that direction. This circuit is made twice: the first installing male deities, the second installing female deities at each of the eight points.6 In both cases, then, the abstract dimensions of time and space are given substantive form in deities; and in turn these deities give concrete expression to the nature and forces of the cosmos.

Second, in everyday life, people combine time and space in their consideration of auspiciousness for journeys. Some common rules are: ‘don’t go east on Monday and Saturday; don’t go south on Thursday; don’t go west on Friday and Sunday; and don’t go north on Tuesday and Wednesday’. Here we see a concern with harmonious conjunctions of an action with a moment in time and with a movement or position in space.

Third, in ritual procedures at the beginning of rites of passage, a sacrificial rite called hom is performed. Part of this rite is worship of the nine planets (nau-graha puja). On several occasions when I observed this ritual, worship was done to more than the nine planets; the additional ‘planets’ were named after the cardinal directions. In this extension of the number of planets—the bodies that mark the flow of time—to include extra planets associated with the cardinal directions that demarcate the sweep of space, Kholagaun Chhetris practised a link between the planets and the directions, again mediated by deities. While the planets and their movement refer to time and its effects on events whose primary character as events is their happening at particular moments in the flow of time, the identification of additional planets with deities that are in turn associated with directions refers to cosmic space and its effects on the constituents of events—actors and products of their action—as happening in particular places in space. And just as the harmonious quality of the temporal conjunctures between humans and the cosmos, mediated and expressed by the movement of planets, promotes the beneficence of events for humans, so the harmonious quality of the spatial conjunctures between humans and the cosmos, mediated and expressed by reigning deities of the cardinal directions, promotes the beneficence of things in those places for humans.7

Figure 2.2 Traditional houses

House as Yantra

The orientation and room layout of Kholagaun Chhetri houses in a yantric configuration oriented by Hindu sacred geography primarily concerns establishing an auspicious spatial medium for the activities and social relations that take place within it. Orienting the house and compound according to the geographical directions, their presiding deities and realms of powers establishes a harmonious conjunction between the domestic mandala and the cosmos as two parallel orders of reality. For Kholagaun Chhetris, such harmony increases the likelihood of beneficial outcomes of domestic activities for the prosperity of those who live in the house. I now turn the a description of Chhetri houses in Kholagaun, including their physical features and a schematic rendering of interior layouts emphasising the relations between rooms or functional spaces that constitute their domestic compounds. My aim is to highlight how and to what extent Kholagaun Chhetri houses are configured as auspicious yantras.

There are two types of houses in Kholagaun. One type I will call ‘traditional’ and the other ‘modern’ (see Figures 2.2 and 2.3). When I began fieldwork in 1973, all the houses in Kholagaun were of the traditional type. By 2001, traditional houses were in the minority (31 of 69), as over the intervening years a significant number of Kholagaun Chhetris had built modern ones. Most of these new houses were built by young men after their marriages as part of the process of separating from their joint families and establishing separate household groups. Both types are two- or three-storey structures. Although they are distinguished by the building materials and some aspects of interior room layout, which I will describe in more detail shortly, there are three design continuities in the relations between spaces of the domestic compound that I wish to highlight: first, the location of the house within the site; second, the placement of the main entrance and the consequent orientation of the house in relation to the geographic directions; and third, the internal layout, especially the locations of the kitchen and worship room in relation to the cardinal directions.

Siting the House and the Definition of Domestic Spaces in the Compound

As I argued at the beginning of the chapter, the configuration of Kholagaun Chhetri houses as a mandala is not based upon the precise geometry, absolute location and exact measurement of spaces themselves. Instead, the mandala configuration is to be found in the nature of the relations between domestic spaces built by the intentional and conventional everyday activities of Kholagaun Chhetris. A consequence of this approach is that it is not necessary to provide exact architectural drawings and elevations of houses. It is for this reason that I use sketch diagrams of Chhetri houses (Figures 2.4 and 2.6) to illustrate their mandala configuration. Still, it is important to provide some indication of the size and scale of Kholagaun Chhetri houses. I do so in terms of the house footprint. The footprints of houses in Kholagaun range in size from 30 square metres to 120 square metres. Traditional houses tend to be smaller than modern houses, though the sizeable traditional house pictured in Figure 2.2 has a larger footprint than the modern house picture in Figure 2.3, one of the more smaller of the recently constructed houses. The traditional house pictured in Figure 4.2 (Chapter 4), which is about median size, is approximately 8.2 metres across the front and 6.5 metres deep; it sits near the back of the site with about 6 metres of courtyard space from verandah to the boundary fence. The modern house pictured in Figure 2.3 is approximately 6.2 metres wide and 4.5 metres deep, again located toward the back of the site with a courtyard extending about 4 metres in front of the main entrance.

Chhetri houses are built on rectangular sites. The site is surrounded by a low wall that defines the boundary of the domestic compound without blocking its visibility from the public road and paths beyond it.8 In respect, then, to the location of the house structure in relation to the boundaries of the site, both traditional and modern houses follow the same pattern: they are located towards one edge of the site away from approaching public roads or paths, leaving space for a courtyard. This results in a configuration of nested domestic spaces—boundary, courtyard, verandah, main entrance and interior of house (see Figures 2.4 and 2.6).

The house is oriented with the main entrance opening out onto the courtyard allowing household members a clear view of it and anyone who may be approaching the house from the public path or roadway. This positioning of the house within the compound defines the courtyard itself as a distinct space and one of its important architectural functions is mediating between public thoroughfares and the house itself. As I will describe in a later chapter, public roads and paths outside the boundary of house compounds are potentially dangerous places where impure people of lower castes (jāt), malign witches (boksi) and malevolent ghosts and other spirits (bhut, pret, pichas) linger.

A covered and raised verandah spans the entire front of the traditional house and some portion of the front of modern houses; its location makes it another mediating space, now between the courtyard that is visible and the interior of the house that is not visible to those outside the compound. It is constructed as a transitional space between the interior and exterior of the house. The floor level of the verandah is one or more steps above the courtyard ground level and on the same level as the floor of the house interior. Also like the house interior, the verandah is covered by a roof. However, unlike the house interior, but like the courtyard, there is not wall or other structure blocking the visibility of the verandah. In this sense, it is an extension of the courtyard because it is open to view from the public paths and roads.

Figure 2.3 Modern houses

Centring the Yantra

In terms of construction and materials, traditional houses are rectangular. Exterior walls are made with sun-dried mud bricks supported on a foundation of boulders. Floors on the ground level are earthen, floors on the upper levels are wood covered with straw mats, cloth or carpets. Windows, doorframes and supporting pillars are wood. The roofs are pitched with wooden rafters covered with thatch. The ground floor is open-plan punctuated by five wooden pillars—four peripheral supporting pillars forming a rectangle around the main pillar (mul tham or mul stambha)—which we saw in the previous chapter is the number of elements and geometric shape indicative of a yantra.

The configuration of these two kinds of pillars—peripheral and main—have different engineering, architectural and cosmological functions in providing support, demarcating functional spaces, and defining the house as a yantra. In an engineering sense, the four peripheral pillars provide secondary internal structural support in buttressing the floor and walls of the upper storeys of the house. They are not architecturally significant in demarcating internal spaces on the ground floor. Instead, this is accomplished by structures associated with domestic activities: a raised kitchen area with a mud stove for cooking and eating—sometimes set behind a low wall (see Figures 2.4 and 2.9); another raised area adjacent to a fire pit (agena) for warmth in winter (see Figure 2.5), a storage area for kitchen utensils and agricultural tools, and in some cases a separate place for sheltering animals at night.

The main pillar not only has an engineering function but also a social one. As one Kholagaun Chhetri elegantly expressed it: ‘In traditional houses, the main pillar is structurally important because it supports the cross beams.’ He then continued in a way that moved metaphorically between the material and social functions of the main pillar: ‘It carries the weight of the house.’ In the next sentences we can see that he retrospectively means that the main pillar carries the material and social weight of the house: ‘It is like the head of the household [ghar pati].’ Both the material and social meanings of the main pillar and the possibility of their metaphoric relation are captured by the word ‘mul’ which Nepalis use as a adjective with two related meanings. First it means ‘principal’ or ‘main’: a large and well-travelled path linking a number of houses in a hamlet and the main road to Kathmandu running through the entire village are each called ‘mul bato’. From this a second meaning emerges, highlighting the sense of ‘source’, ‘root’ or ‘origin’ and expressing the relation between the main road and the secondary roads or paths (sano bato or just bato) leading from it. In the case of the house of a man whose sons have established separate houses for their own household groups, the father’s house is called the ‘mul ghar’ indicating that it is both the principal house of the core agnatic descent group (santan) and the kinship root from which the sons’ and their houses have branched—just as secondary roads or paths can branch from a main road; it is also the origin of and source from which the sons and their houses originated and to which they return for major rituals.

Figure 2.4 Sketch plan of traditional house (ground floor)

The main pillar of a house is ‘mul’ in both senses. It is the main or principal structural support for the material house, linking to other supports, such as the four peripheral pillars and cross beams that bear the upper floors. Socially, it is the source or origin of auspiciousness for the well-being of the people living in the house. As one Kholagaun Chhetri put it, ‘the main pillar is for the health, happiness and security of the house and those living in it’.9 In addition, as I describe in more detail in Chapter 3, the main pillar can sometime rest on a subterranean serpent deity (nāg) preventing it from wriggling and causing cracks and eventual collapse of the house. The positioning of the main pillar near the geometric centre of the house has as much to do with its synechdocal meaning (see Blier 1987:37) of transposing into architectural form the sacred and social source from which the house emanates outward towards the four peripheral pillars as it does with any architectural function of defining internal space.10 Kholagaun Chhetris worship this main pillar every day as part of their daily ritual activities to ‘please the deity’, enhance the health, happiness and security of the house and its inhabitants and, if one is present, propitiate the subterranean serpent deity upon which the pillar rests.

In terms of their cosmological function, the five pillars are a configuration forming a yantra. The main pillar is usually located in or near the physical centre of the house and the four peripheral pillars complete the yantric design and meaning in their demarcating a four-sided polygon associated with the cardinal directions.

Figure 2.5 Agena in a traditional house

In positioning these pillars during construction, Kholagaun Chhetris told me that they did not strictly align them with specific directions. Instead, for them, it is simply the fact that there are four of them—the number that they say is indexical of the cardinal directions.11

The open plan of the ground floor means that architecturally there are no internal structures determining the location of the main entrance. One of the long sides of the rectangular footprint forms the front of the house where the main door is located to the left of centre.12 This is an architectural feature that distinguishes residential structures for humans from temples for deities where doors are placed in the centre of the outer walls. People in Kholagaun told me that to put a door in the middle of the front wall of a house would be inauspicious for the health and welfare of the residents.13

Modern houses (Figures 2.3 and 2.7) are built of kiln-fired clay brick walls on a concrete foundation. The flat roof, the floors on all levels and the staircase connecting them are all made of reinforced concrete. Walls are rendered in concrete. Windows, door frame and doors are made of wood. A distinctive architectural feature of the interior of modern houses is that the ground floor is divided into separate rooms rather than the open-plan of traditional houses. The structural support for the upper storeys is integrated into the wall construction of these ground floor rooms. As a result, there are no visible pillars or any other structures in an explicit yantric configuration. Despite this, Kholagaun Chhetris build a yantric configuration into their modern houses in two ways. First, at one stage of the construction process, a consecration ritual called Jag Puja (Worshiping the Foundation) is performed. The main part of the Jag Puja involves placing five sacred vessels and deities in the four corners of the foundation—‘one for each direction’, a village priest told me—and in the centre of the house plot for the main pillar. The effect of the rite is to transpose yantric spatiality and its cosmological meaning of spatial auspiciousness onto the architectural form of the foundation and the house built upon it. Second, the house’s main pillar is re-constituted in the daily worship. The clearest example of this is the house of Bala Ram. He built a modern house several years ago. He and his household group, which includes his wife and unmarried daughters, now live on the upper floors; his son and his separated household group live on the ground floor. Bala Ram told me that on each floor of the house there is a place in the central hallway—architecturally, the main path to or root from which the various rooms branch—that is explicitly designated as the main pillar and worship (puja) is done to it every day in the same way as was done to the main pillar in the traditional house he had demolished to build his new one.

Figure 2.6 Sketch plan of modern house (ground floor)

There are three main variations in the floor plans of modern houses that affect the location of the main entrance. In one, there is no single entrance to the interior of the house. Instead the door of each ground floor room opens directly to the outside; there is an external stairway to a verandah along the front of the upper floor allowing the room doors to open directly to the outside. The main entrance is usually the door of the middle room of the ground floor which follows the pattern of traditional houses in being located to the left of centre of that room. In a second variation, the room layout consists of a living room with internal doors leading to the other rooms. There is one door from the outside into the central living room; this is clearly the main entrance and, like traditional houses, it is located to the left of centre in the front façade (Figure 2.3). The stairway connecting the floors may be internal or external or a combination, that is, internal from ground to first floor and external from first to second floor. In the third and most common variation, the ground floor plan has a central hallway with separate rooms on each side (Figure 2.6). As a result the main door is located in the centre of the façade. However, one of the front rooms usually extends forward of the plane of the wall where the main door is placed producing an asymmetrical façade; this architectural feature negates the potential inauspiciousness of main door’s placement in the overall centre of the house because it is located off-centre in the plane in which it is built. The stairway configuration is like that of the second type of modern house.

I have spent some time describing how Kholagaun Chhetris ensure an auspicious location for the main entrance because it has two major functions. Architecturally, it is located in and creates the façade of the house. It is in relation to the front that Kholagaun Chhetris orient their houses and this, in turn, effects important aspects of the relations between rooms and spaces of the internal layout, such as the location of the kitchen and worship room. Socially, the main entrance is the threshold to the house mediating between inside and outside.

Orienting the House

Map 3 shows the location and orientation of Chhetri houses in Kholagaun in the mid-1990s. An analysis of the orientation of the houses in Kholagaun reveals a number of patterns. First, the vast majority of houses (nearly 80%) face the southern quadrant. Second, the houses in compounds bordering directly onto the north-eastern side of the main road all face the main road and thus are oriented towards the south-west. However, houses in compounds bordering directly onto the south-western side of the road are sited at right angles to the main road so that the front faces the south-east. Third, houses located on paths away from the main road usually are sited so that the courtyard borders directly onto, and is visible from, the path. Fourth, if close kin have houses in adjacent compounds, they are oriented to each other so that the courtyards are adjoining and mutually visible.

From talking with Kholagaun Chhetris about the orientation of their houses and from observing the activities they perform in the front spaces of their domestic compounds—main doorway, verandah and courtyard—there are three interacting factors which explain these patterns. The first is the orientation to the southern quadrant and the sun. Kholagaun Chhetris were explicit about this as one of the most important considerations in orienting their houses. It was usually the first one they talked about with me. In the winter especially, they wanted their courtyards and verandahs to be in the sun as long as possible. After the cold winter nights, people like to sit in the morning sunlight to warm up. Throughout the day, they dry recently harvested grains and do chores, such as winnowing rice, husking corn, and flattening rice, in the sunny courtyard with the added benefit that they can remain in the house compound while they work and still protect it from intruders and dangers from outside the compound.

Map 3 Kholagaun Hamlet (location and orientation of houses)14

These practical benefits of orienting the house and courtyard towards the sun are linked to the sacred geography of cardinal directions and deities that are diacritical of the house in the yantric configuration. The southern quadrant is the location of two forms of auspicious and beneficial fire. In the south-east the reigning deity is Agni who is associated with the earthly form of fire used in cooking and the ritual form of fire used in sacrifice. For some villagers, Surya, the God of the Sun, is the reigning deity of the south-west co-existing with Nirriti. The sun is also one of the nine astral bodies and is the celestial form of fire with the auspicious qualities of heat and light, the causes of life and knowledge respectively.15 The warmth of the sun is the source of all life that nurtures the growth of crops in the fields. The amount of sun a plot of agricultural land receives affects its price. The light of the sun is both the source and representation of knowledge and enlightenment. In looking at the sun, its light fills the senses in the same way that religious knowledge fills the mind or intellect (buddhi). One ritual goal of Bartaman, a boy’s rite of passage into adulthood and the Householder stage of life, is the acquisition of religious knowledge under the tutelage of a guru. At the beginning of the phase of Bartaman when the initiate becomes a celibate student ‘learning the Vedas’, he performs a rite called ‘surya darśan’ in which he looks at the sun and the presiding priest instructs him: ‘Your goal is the acquisition of religious knowledge (gyan) as luminescent and enlightening as the sun’s light.’ Darshan is a deliberate beholding of a revered person or deity motivated by homage and worship and believed to have auspicious consequences for the beholder. Darshan brings blessings to the beholder since the sight of the deity infuses the beholder with the deity’s qualities and virtues.

In a seeming contradiction to its auspicious qualities, the southern quadrant also includes the cardinal south whose reigning deity is Yama guarding the gates to heaven. It is the direction of the inauspicious and destructive powers of the sun as fire that breaks down earthly forms and is associated with death and ancestors. But the substantive inauspiciousness of the static cardinal south is offset by human movement in relation to it. A household priest explained to me that when a house had its door facing south, its residents are facing north as they entered the house, the auspicious direction of where the gods dwell.16 I was given a similar explanation for why beds should never be oriented with the head to the north: when a person wakes and rises, the first direction that he or she would see is the inauspicious south and this would portend death.17

The second factor in house orientation is the relation to public thoroughfares—the main road and the paths leading off from it. House compounds were sited so that the courtyard borders onto the road or path by which people approached the house. By bordering onto the public thoroughfares, the courtyard mediates between the world outside the compound wall and the intimate, vulnerable place and people inside the house itself. Visibility is a primary form of mediation enabled by the placement of the courtyard: it allows members of the household to see, and be seen by, people approaching and to adopt the appropriate social stance towards the person should they wish to enter the compound.18 Kholagaun Chhetris indicated that this is an important factor explaining the orientation of houses sited to the north-east and bordering directly onto the main road. All of them face the main road so that the courtyard is located between the road and the house. As a consequence of their orientation to the main road, these houses face the south-west.

In the case of houses bordering the main road to the north-east, the confluence of the main road and the sun as factors influencing the orientation of the house is mutually reinforcing: the house facing the southern quadrant is a necessary and recognized auspicious consequence of its orientation to the main road. The interaction between orientations to public thoroughfares and to the southern quadrant of the sun is less straightforward for houses located on paths away from and to the north-east of the road and for those located to the south-west of the main road. Paths running away from the road to the north-east meander among the domestic compounds so that there is no fixed directional orientation in relation to them. Facing a path could mean facing any direction. However, the current siting of houses on paths to the north-east of the road suggests that a combination of orientation to the southern quadrant/sun and to the path had to be actively considered so that the courtyard bordered on the path and faced the southern quadrant. Houses bordering the road on the south-western side are all oriented in the same way—at right angles to the main road and facing south-east. The reason for this orientation is that if the houses faced the road, they would of necessity face the north-east and not the southern quadrant. By auspiciously rotating the orientation clockwise 90 degrees from the road, the houses faced the southern quadrant (SE) and maximized the time the verandah and courtyard were in the sun. Most houses on the south-western side of the road but located off the road on paths also adopted the same orientation pattern: siting the house so that the courtyard bordered on the path and the housed faced the southern quadrant.

A third factor affecting house orientation is kinship. Kholagaun Chhetri households form around a core agnatic descent group (santan) consisting of a man and his son; in larger joint households the santan may extend to a third or fourth generation. Among Brahmins and Chhetris in Nepal, post-marital residence is patrilocal with wives becoming members of the households of their husbands and sisters moving away to live with their husbands. When joint households divide, a new house is eventually built, often in the same compound or on an adjacent house plot. If the split was amicable, the house compounds are sited so that the separate walled courtyards are mutually visible, making one complex social space for the two households. There were twelve cases involving twenty-five house in which kinship was a factor in house orientation. The most striking case was a complex of three houses on the south-western side of the road. A Chhetri man had three sons, their wives and children living in a joint household. He told me that to avoid the possible acrimony of his household splitting in his old age or after he died, he and his sons had agreed to split the household and build two more houses in the compound. The houses were sited in a U-shape to form a central space for the three courtyards: the main house (mul ghar) where the father lived with one of the sons had its back wall toward the main road so that its front was facing the south-west. The other two houses were positioned at right angles to the main house so that they faced each other, one with the main door toward the north-west and the other with the main door toward the south-east. The entrance to this complex courtyard opened onto a new path that had been made from the main road. This is the only house in Kholagaun with its back to the road. It suggests that orientation to the sun and to the houses of kin was important because a new path was made to the newly sited compounds. A more typical case is two brothers living to the south-west of the road who built their separate houses in parallel so that both faced the preferred southern quadrant with bordering courtyards accessible by a path from the main road. In both these cases, there is an interaction between all three factors of house orientation—cardinal direction, kinship and relation to paths. The importance of kinship as a factor of orientation can be judged from the fact that the four houses in Kholagaun that did not face the southern quadrant were those adjoining and oriented toward the houses of close agnatic kin.19 However, the siting of the other twenty houses had been manipulated so that they faced the southern quadrant and have courtyards with mutual visibility and access to public thoroughfares.

Main Entrance as Threshold

The second function of the main entrance is being the threshold of the house. It is the transition between its invisible interior and the visible exterior. For Kholagaun Chhetris the house and its interior layout are intimately associated with the self of the household head and by extension with the other household members. There are two ways in which this self–house relation is created among Kholagaun Chhetris: horoscopes and everyday activities.20 At the time of construction, a Brahmin household priest (pujāri) is consulted to calculate the horoscopes of the house—the unique conjunction of the birth of the house with the flow of cosmic time—and the household head—the unique conjunction of the birth of the household head with the flow of cosmic time—in order to harmonize the cosmologically-determined attributes and fate of the household head with those of the house, that is, to determine an auspicious relation between the household head and the house. In terms of everyday activities, the interior of the house is the place for the storage and consumption of the household’s material wealth that is produced by those living in it: food is cooked and eaten, grain is stored, jewellery and other valuables are locked away, and procreation of children occurs.21

If the interior of the house is associated with the self as producers and consumers of the household’s prosperity, the exterior is associated with the other and the production of the household’s prosperity. Outside the house are people with whom and the places with which relations are established for the productive activities of household members. Most productive activities they undertake occur outside the house structure: on the verandah, corn and rice are winnowed; during the day in the courtyard animals are kept and fed, blacksmiths and tailors do their work for the household, and important rituals are performed; outside the compound are the fields where agricultural production occurs, the locations where members with paid employment go to their places of work, and the villages where brides are found.

Household members pass through the threshold from interior to exterior and from exterior to interior of the house many times each day. Such passings are not trivial events because the doorway that forms the threshold for both traditional and modern houses (as well as the Royal Palace and commercial hotels) is framed by three deities. The first is Ganesh, the Lord of Obstacles, on the left as one faces the door from the outside of the house. Kholagaun Chhetris offer worship to Ganesh before any undertaking to remove the obstacles which might prevent a person achieving the desired goal of action, including both everyday projects as well as rituals themselves. It is for this reason that Ganesh is worshipped at the beginning of every ritual. Ganesh is oriented to the main entrance so that when a person leaves the house moving from interior to exterior, Ganesh is on his or her auspicious side. Kholagaun Chhetris told me that as a result, ‘Ganesh will help with the success of any business or work the person is leaving the house to accomplish.’

The second is the Goddess Devi in her manifestation as Saraswati or Laxshmi on the right as one faces the door from the outside of the house. The specific deity on the right side (as one faces the main door from the outside) varies from house to house. Some Kholagaun Chhetris installed Laxshmi, Goddess of Wealth, others Saraswati, Goddess of Learning. Both are aspects of the Goddess Devi, the personification of female divinity and cosmic energy (shakti). When I asked a Kholagaun Chhetri about this variation, he explained that in one sense it did not matter which goddess was used since, as manifestations of Devi, each provides protection from evil entering the house. In another sense, he went on to explain, different people choose Laxshmi or Saraswati for personal reasons. Those who choose to install Laxshmi do so because when a family member enters the house moving from exterior to interior, Laxshmi is on his or her auspicious right side and the prosperity over which Laxshmi reigns and which is produced outside the house will flow into the house with every passing of a member into the house. When I asked him why people install Saraswati on the right, he said he was not sure but it was probably for a similar reason: learning and knowledge would flow into the house with every entrance. A household priest who performed worship for several Kholagaun Chhetri households explained that what is important is for Devi in whatever form pleases the household to be located to the right of the door to ensure protection for the occupants.

Third, just above the doorway of the main entrance is an image of a serpent deity (Nāg). The image is either painted on the wall or a rice-paper print is stuck to the wall. Serpent deities, too, can significantly affect the house’s prosperity but in a Janus-faced way. They are associated through various myths with water and rainfall, two natural phenomena that are vital conditions for and metonyms of prosperity that encompasses not just the fertility of land in producing crops but also other forms of prosperity derived from exchanging the crops, such as land, cash, gold and jewels. Accordingly, nags are understood to grant increases in wealth to a household, to give protections for its jewels, gold and other treasures. Locating the nag image over the doorway so that it is above the heads of members as they pass in and out of the house places it in an auspicious and protective position. Perhaps the most graphic illustration of this meaning in Nepal is the way in which the hood of the Shesha Nag forms an auspicious and protective canopy over the head of the King, an avatar of Vishnu. Terrestrial snakes are a manifestation of these serpent deities and, as we will see in the next chapter, houses are positioned on a site and built so as not to disturb them, that is, so that humans and serpent deities can dwell on the same site harmoniously.

But there is a dangerous aspect to nags, especially those that live subterraneously. They are seen to be the cause of the destruction of houses. Their underground wriggling can cause the cracking and collapse of house structures—both an event and a representation of the destruction of general household prosperity and the loss of possessions. They are also associated with other dangers to the house, including lightning, fire and poisonous snakes that can enter the house through small openings and attack the inhabitants, especially during the monsoon season. Every year during the monsoon season (July/August), nags in their dangerous aspect are propitiated on Nāg Panchami22 when the image of the nag over the main entrance is renewed and worshipped to propitiate the nags.

In Figure 2.7 there are three photos illustrating this arrangement of deities framing the threshold. The entrance to the modern house in Kholagaun has two elaborately carved wooden doors with three vertical panels reminiscent of the main doors of the Royal Palace. The top panels are carved with images of Ganesh [left] and Saraswati (right). The middles panels are of the Goddesses Yamuna and Ganga. These goddesses are personifications of the sacred rivers Jumna and Ganges and rivers are auspicious places associated with fertility and abundance (Marsh 1968). Among the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley, images of Yamuna and Ganga are placed beside the doorways to temples and are worshiped as Sri and Laxshmi (Slusser 1982:321). Like the doors of the Royal Palace, the lower two panels depict auspicious water vessels that welcome those entering the house. This is the most elaborately decorated doorway in Kholagaun. When I spoke with the owner about it, he explained that, because Newars are historically known for their woodcarving of windows and doors, he had contacted a Newar craftsman to carve the doors. The owner’s design was as follows: top panels: Ganesh and Kumara (God of wealth) in left and right panels respectively; middle panels: Saraswati and Laxshmi in the left and right panels respectively; lower panels: auspicious water vessels. The craftman took some liberties with the owner’s design that reflected his Newar cultural heritage, particularly the inclusion of Yamuna and Ganga in the middle panels. Despite this, the owners were very pleased with the doors and said that the revised configuration of deities was appropriate because it retained the core meanings of main entrances to a house: removal of obstacles, protection from evil, and auspiciousness, well-being and prosperity flowing into the house.

The doors of the main entrance to the Narayanhiti Royal Palace in Kathmandu follow a similar pattern: images of Ganesh and Saraswati in the left and right upper panels respectively; swastika symbols of auspiciousness in the middle panels; auspicious water vessels in the lower panels. The entrance to one of the more upmarket hotels in Kathmandu is framed by statues of Ganesh on the left and Saraswati on the right. The main entrances of traditional houses are not so elaborate and visible from the outside except for an image of a nag which is always placed over the doorway and visible from the outside. In some traditional houses, there are small niches inside the doorway for images of Ganesh and Devi on the left and right respectively; but more often, instead of fixed architectural forms around the entrance, Ganesh and Devi are installed each morning as part of the daily household worship when they are invoked with offerings of coloured pastes, rice and flowers dabbed onto each side of the doorway.

Figure 2.7 Main entrances (clockwise from upper left): modern house, Narayanhiti Royal Palace, traditional house, and hotel

Demarcating the House

In a recent period of fieldwork, sketches of the interior layout of about three-quarters of the Chhetri houses in Kholagaun were drawn on the bases of tours through the houses or from descriptions of the people living in them. In explaining the interior layout of their houses, Kholagaun Chhetris consistently identified four types of rooms or functional spaces in both traditional and modern houses defined according to the major domestic activities carried out in them: kitchen, worship, store, and sleeping.23

As we have seen, the ground floor of traditional houses is open plan punctuated by supporting pillars, a main pillar, a stairway to the upper floor and in some cases a low wall demarcating and visually blocking the view of the kitchen area from the outside. The most important functional space is the kitchen area or chula. In Nepali, the word ‘chula’ refers to the cooking fire as well as to the space where cooking occurs and the food is eaten. It consists of a raised platform and a cooking stove made of mud that can accommodate two vessels (Figure 2.8). When the food is prepared, members of the household eat it within the space defined by the raised platform. The ground floor may also be used for the night-time shelter of any cows, goats and chickens kept by the household. The night byre area is usually located away from the kitchen in the other section of the ground floor defined by the stairway. Other tools and assets of production are also stored on the ground floor—hoes and adzes used for cultivating the soil, baskets and yokes used to transport grain, khukris for cutting wood and sacrificing goats, and in some houses old army rifles used to kill rabid dogs and other dangerous animals.

In traditional houses, there is an internal stairway to the upper floor. It is a place not only for the passage of people to the upstairs rooms but also for the passage of smoke from the cooking fire up and out through a vent in the centre of the thatched roof. The upper floor is more architecturally defined; walls are constructed to create three to five separate rooms opening off a small lobby (matān). Most of these are called ‘sleeping rooms’ (Figure 4.3). During the day, these rooms are used as public spaces for entertaining important guests and kin; at night they are used as sleeping rooms for members of the household. All houses have a place for performing the daily worship for the welfare and prosperity of the house, its members and their ancestors. There may be a separate worship room (puja room) with a raised platform or wooden stand where the images of the deities worshipped are installed (see Figures 2.9 and 2.10); if there is not a separate room, a corner of the store room is often set aside for the daily worship. The store room is usually a separate place for the storage of the household’s wealth—grains from the agricultural fields, jewels, precious metals and other valuables.

Figure 2.8 Kitchen in a traditional house

Figure 2.9 Puja Room in a modern house

Modern houses do not have open-plan spaces. Access to the upper floors is via stairways, most of which are externally accessible, that is, they are accessible without entering the main entrance though many are enclosed; about one-third have internal stairways. The interior of the house is divided into separate rooms on all floors and there is more variability in the location and diversification of rooms compared with traditional houses. Kitchens in modern houses are still mostly on the ground floor, but more are located on the upper floors than in traditional houses. They usually have counters for preparation and for the gas hotplate for cooking and a table with chairs where food is served and eaten (Figure 4.4). Sleeping rooms are not confined to the upper floors but can be located on the ground floor and may be used for entertaining guests during the day if another room has not been dedicated in the design for entertaining guests and/or watching television.

Figure 2.10 Puja room in a traditional house

The interior layout of Kholagaun Chhetri houses manifests the way in which yantric and mandalic spatial modes co-exist in the domestic mandala. The locations of the worship room and kitchen are diacritical of these two different modes of configuring domestic space. According to both the Vastu Shastras and to everyday bastu rules articulated by some Kholagaun Chhetris, the worship room should be located in the north-east. Its actual placement in the north-east in the majority of Kholagaun Chhetri houses (see Figure 2.11) indicates conformity to the bastu rule they articulate and a yantric mode of spatial organization in its concern with alignment with the cardinal directions. If the northern quadrant as a whole is included—remembering that north is the ‘abode of the gods’ and a direction that is compatible with worshipping them—then in about two-thirds of houses the worship room aligns with the appropriate cardinal direction. That the worship room is located on an upper floor in the majority of cases is also important. By establishing the worship room or area on an upper floor, Kholagaun Chhetris did not have to take into account its position relative to the main entrance, which, as we will see next, is a portal for impurity and danger from outside the house. As a result, the bastu rule could be used in an unencumbered way in determining the location of the puja room solely on the basis of the most auspicious and compatible cardinal direction according to the yantric organization of space.

Figure 2.11 Orientation of kitchen24 (left) and puja room (right)

The location of the kitchen presents some problems for the house as a yantra in which activities and rooms are aligned with compatible cardinal directions. According to the bastu rules, it should be located in the south-east, the direction of Agni, god of fire, that is in harmony with the activity of cooking. Yet, in most Kholagaun Chhetri houses (thirty-one out of forty-three), they have placed the kitchen in the northern quadrant of the house (see Figure 2.11). The pattern is even more pronounced for the thirty-two houses—both traditional and modern—where the kitchen is on the ground floor; in twenty-four of these houses (nearly 80%), it is in the northern quadrant. This pattern makes sense when we remember that the main entrance is located in the southern quadrant. As a result, placing the kitchen in the northern quadrant of the ground floor means that it is the space or room farthest from the main entrance. When looked at according to the location relative to the main entrance, rather than aligned with a cardinal direction, almost all kitchens in traditional and modern houses are located far away from the main door either by being placed in the farthest corner or room of the ground floor (thirty houses) or on an upper floor (ten houses).

This is a problem I take up in Chapter 4 where I show how locating the kitchen far away from the main entrance in terms of physical distance is placing it culturally in the centre of the domestic mandala in its concentric configuration. Prior to that, in the following chapter I describe the multi-layered process of building a house as an auspicious yantra.

Notes

1 This problem in modernist architecture is specifically explored by Holston (1989), Kent (1990), Rapoport (1969, 1990) and Waterson (1991). De Certeau (1984) makes the more general argument about the subversive, devious, dispersed, invisible consumption of space that undermines the intentions of agents of domination in society—government officials and city planners who design and produce space.

2 Population data is based upon a complete village survey conducted in the mid-1990s.

3 This is often a transitory arrangement while funds are amassed to build separate houses for the separated household groups.

4 Rahu and Ketu are also used to name the more recently discovered planets, Uranus and Neptune respectively.

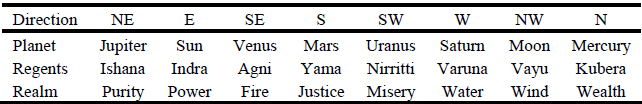

5 Below is the alignment that Chakrabarti derives from various parts of the Vastu Shastras (1999:108)

6 This installation of both a male and a female deity at each point of the astadal is consistent with the male-female dualism of tantrism infusing Kholagaun Chhetri ritual practices.

7 As I described in the previous chapter, this concern with harmonious relations between the house and its spatially-defined milieu is mapped in the vastu purusha mandala in which deities are associated with particular cardinal directions and this sacred geography spatially orients the house and its design.

8 An exception to this is compounds bordering on expanses of agricultural fields toward the outer edges of the hamlet. There are no walls separating the compound from the fields on land that drops off sharply.

9 Note in this quotation how the house and its residents are co-substantial. This is a theme that will be important in later chapters.

10 Later I will suggest that there is another centre in a house that emerges when domestic space is seen in the mandalic or concentric configuration.

11 The spatial configuration of five pillars in traditional houses reiterates the configuration of five sacred vessels and images of deities placed in the four corners of the foundation and in the middle of the house plot in a ritual called Jag Puja described in the next chapter. It is performed just prior to the laying of the foundations.

12 In describing the orientation and architectural features of houses, I will adopt the system of referring to left-right directions relative to a person leaving the house or with his/her back to the plane of the house.

13 While Kholagaun Chhetris said they did not know the reason for the auspiciousness of locating the main door off centre, the Vastu Shastras suggest an architectural reason that reiterates their everyday knowledge of the right-hand side as auspicious. According to Vastu Shastra design prescriptions that use the eighty-one module vastu purusha mandala, the main door of residences should be located in or near the sixth of the nine modules from the right-hand corner of the front of the house. Locating the door towards the left makes the interior space to the right of the door deeper or larger than that to the left. ‘This results in an effective shift of weight of the structure toward the right side, giving it a slight [auspicious] clockwise turn’ (Chakrabarti 1999:115).

14 As mentioned previously, Chhetri houses are rectangular and the front door is usually placed on one of the long walls. I have retained that convention in the map to indicated the orientation of houses.

15 ‘Through his [Surya’s] rays he puts life into food grains and living beings. He is the father of all’ (Mahabharata 3.135).

16 The converse of this was not considered, i.e. a south facing main entrance means that when residents leave the house, they would be facing the inauspicious realm of Yama and this would not portend well for any projects or activities they were intending to do. As we will see shortly, there are other ritual dimensions of the doorway that bring auspiciousness the act of leaving the house.

17 The Royal Palace, Narayanhiti, does not face directly south but slightly to the west of south (SSW).

18 This is a particularly important factor in relation to the house as a concentric mandala where, as I describe in Chapter 4, there is a concern with protecting the house and its inhabitants from forms of impurity and danger that exist outside the compound.

19 In the early 1990s there was a house on the south-western side of the road that, unlike the usual right-angle relation to the road and consequent south-western orientation, faced the road and thus the north-east. This was a newly built modern house. In a recent visit to Kholagaun, I noticed that many of the newly built houses were oriented in this manner suggesting that orientation toward the main road was becoming more important than the sun.

20 There is a possible third but more oblique relation between house and owner in the vastu purusha mandala. As described in the previous chapter, the vastu purusha mandala consists of a grid overlaying the anthropomorphic image of Purusha oriented to the cardinal directions and the deities associated with them. The grid overlaying the image of Purusha is architecturally specific in the sense that it is used as the template only for the design of the layout of built forms to manifest the correlations between the cosmos, the body of the house and the body of the owner (see Chakrabarti 1999:81).

21 I am treating procreation as a consumption activity in the sense of ‘consuming’ the procreative potential of wives in the birth of children and in the sense of rearing of children as one of the most important forms of prosperity, the abundance of which the house’s auspiciousness is supposed to ensure.

22 Pachami refers to the fifth day [tithi] of the lunar half-month. Nag panchami takes place during on the fifth day of the waxing lunar half-month (see Anderson 1971:87).

23 Some of the more wealthy household groups that owned television, identify a ‘TV room’.

24 Numbers in the diagrams indicate the number of houses in which the room is aligned with the particular directions. They are based on sketch diagrams of room layouts of three-quarters of the house structures in Kholagaun. The sketches were drawn from both my direct observation and from descriptions by the occupants. The data about the location of the kitchen (32 cases) are fewer than the 43 houses for which I have sketches because of the hesitancy of some people in providing descriptions of the house I did not enter for this purpose; there are fewer cases of data on the location of the worship room largely because it is often part of another room.