Bond-labor was not new; in surplus-producing societies, in England and elsewhere, lifetime bondage had been the common condition of labor prior to capitalism. But the social structure of those times was based on production relationships in which each person was socially, occupationally and domestically fixed in place. Pre-capitalist bond-labor was tied by a two-way bond: the workers could not go away, but equally the master could not send them away. However, this relationship, which was essential to feudalism for instance, was inimical to capitalism. The historical mission of the bourgeoisie was to replace the two-way bondage of feudalism with the two-way freedom of the capitalist relation of production. The capitalist was free to fire the workers, and the workers were free to quit the job. The political corollary was that the bourgeoisie was the only propertied class ever to find advantage in proclaiming freedom as a human right.

Capitalism is a system whose normal operation is necessarily predicated upon the continuing presence of a mass of unattached labor-power of sufficient proportions that each capitalist can have access to exploitable labor-power, in season and out, in city or in countryside, and at a minimum labor cost. In newly settled territories, such a necessary reserve army of labor, though at first absent, would eventually be created1 in the normal process of capitalist development, as a result of: immigration induced by higher wages caused by the shortage of wage labor; increased productivity of labor, resulting from the use of improved techniques and instruments of labor; the normal process of squeezing out the small or less efficient owners and making wage laborers of them by force of circumstance; and the natural increase of the dependent laboring population.2

But the situation in which the Anglo-American plantation bourgeoisie found itself in the 1620s, seeking to preserve its profitable tobacco monoculture in the face of the declining price of tobacco, did not permit – so far as its narrow class objectives were concerned – waiting for longer-term solutions.

Since the freedom of the capitalist to fire the workers is predicated on the freedom of the worker to leave the employer, the plantation bourgeoisie created a peculiar contradiction with respect to the free flow of capital within its system by reducing plantation laborers to bondage. The plantations, being capitalist enterprises, were subject to the normal crises of overproduction. As capitalist monocultural enterprises, they were furthermore subject in an extraordinary degree to the vagaries of the world market. Even in times of a generally satisfactory market, natural calamities, wars, or inimical governmental administration inevitably brought business failures and the abandonment or dissolution of individual enterprises in their wake. In the normal course of capitalist events, individual reverses of fortune require liquidation of enterprises, and the normal procedure in such circumstances is to “let the workers go,” that is, to discharge them. But the very purpose of bond-servitude is to see to it that the workers are not “let go”; and a system of laws, courts, prosecutions, constabulary, punishments, etcetera, is instituted to enforce that principle. The plantation bourgeoisie dealt with this contradiction by establishing a one-way bondage, in which the laborer could not end the tie to the capitalist simply by his own volition; but the capitalist could end the tie with the worker. In the solution imposed by the plantation bourgeoisie, the unpaid aspect was designed to meet the need to lower labor costs, the long-term bondage was the surrogate for the nonexistent unemployed labor reserve, and the chattel aspect of the new system of labor relations made it operable by satisfying the functional necessity for the free flow of capital.

An Ominous New Word Appears – “Assign”

In attempting to fix the point in time at which the unambiguous commitment to chattelization began, it is helpful to take note of the first appearance of the term “assign” in relation to laborers. To “assign” means, in law, “to make over to another; to transfer a claim, right or property.” The appearance of this term in relation to the change of a laborer from the service of one employer, or master, to another betokens the chattel status of the laborer. No longer is the contract for labor an agreement entered into between the laborer and the employer; it is rather a transacation between two employers, in which the laborer transferred, “assigned,” has no more participation than would be had by an ear-cropped hog, or a hundredweight of tobacco, sold by one owner to another.

Between January and June 1622, the Virginia Company established a standard patent form.3 The form carried a provision that the laborers transported under the patent could not be appropriated by the colony authorities for any purpose except the armed defense of the colony. What is significant in the context of the present discussion is that the Company guaranteed this protection not only to the original patentee but to his “heires and Assigns.” Implicit here, and as would become explicit within less than four years, is the formal establishment of the legal right of masters to “assign” laborers, or to bequeath them. Already, of course, as early as 1616, a system had been established under which any private investor was entitled to fifty acres of Virginia land for himself for every worker whose transportation costs the investor paid.4

The case of Robert Coopy’s indenture, dated September 1619, is the first recorded instance of a worker being obligated to work for a specified length of time without wages in order to pay off the cost of his transportation to Virginia.5 Two years later, Miles Pricket, a skilled English tradesman, while still in England agreed with the Virginia Company to work at his salt-making trade in Virginia for one year “without any reward at all, which is here before paid him by his passage and apparell given him.”6 The one-year term was normal for England, but the worker’s paying for his own passage was innovative. Prickett did come to Virginia, and in March 1625 was the holder of a 150-acre land patent in Elizabeth City.7

Retrospectively, these early incidents appear as preconditioning the reduction of laborers to chattels. But it was not until 1622 and 1623 that this portentous custom was established as the general condition for immigrant workers, formalizing their status as chattels. An analysis of a score of entries in the records of the time shows how the chattel aspect of bond-servitude was designed to adapt that contradictory form to capitalist categories of commodity exchange and free flow of capital.

Saving harmless the creditors of decedent. William Nuce, brother of Thomas Nuce and member of the Colony Council, died in late 1623. His estate was encumbered with debts, including one of £50 owed to George Sandys, and another of £30 to William Capps. Both debts were settled by the assignment of bond-laborers to the creditors.8

Disposal of unclaimed estate. William Nuce left eleven destitute laborers who had been in his charge as company employees, “some bound for 3 yeares, and few for 5, and most upon wages.”9 They were sold for two hundred pounds of tobacco each (not counting those four with whom George Sandys reported having such bad luck).10

Avoidance of bankruptcy. Mr Atkins, in order to relieve his straitened circumstances, sold all his bond-laborers.11

Option to buy. Thomas Flower was assigned to Henry Horner for three years. But it was stipulated by the Virginia General Court that if Horner decided to sell the man, John Procter would have first refusal.12

Capital market operations. In the prelude to the case cited immediately above, John Procter assured Henry Horner that he, Procter, would procure a servant for Horner, saying that “[H]ee [Procter] had daly Choice of men offered him.” (Procter told Horner not to let the servant know he had been sold until they were embarked from England.)13

In January 1625, three servants of William Gauntlett were sold to Captain Tucker. The sale was recorded in the Minutes of the Virginia General Court.14

Velocity of circulation. Abraham Pelterre, sixteen-year-old apprentice, arrived in Virginia in 1624; within two years he had been sold hand to hand four times.15

Contract for delivery; penalty for failure to perform. Humphrey Rastill, merchant of London, contracted to deliver “one boye aged about fowerteene yeers … To serve [Captain] Basse [in Virginia] or his assignes seaven Years,” and bound himself “in the penaltye of forfeiture of five hundred pownd of Tobacco.” On 3 January 1626, six weeks after the order had been due for delivery, on Basse’s petition the Court ordered Rastill to make delivery by 31 January or pay the forfeit.16

Property loss: damages assessed. Thomas Savage, a young servant, was drowned in consequence of negligence on the part of a man who had use of him but was not his owner. The culprit was ordered to pay the owner three hundred pounds of tobacco as indemnity.17

Exploiting sudden entrepreneurial opportunities. John Robinson sailed from England in the winter of 1622–23, bringing bond-laborers with him, to settle in Virginia. He died en route. The ship’s captain seized Robinson’s property, including the bond-laborers, with the intention of selling all for his own account.18

The Privy Council in England in 1623 confirmed the gift to Governor Yeardley, of twenty tenants and twelve boys that had been left by the Company at its liquidation. Yeardley was authorized to “dispose of the said tenants and boys to his best advantage and benefit.”19

The Colony Council in January 1627 divided up former Company tenants among the Council members themselves: eighteen to Yeardley; three each to five others; two to another; one to each of two others (including the Surveyor, Mr Claiborne, who was given William Joyce and two hundred pounds of tobacco).20

Liquidation of an estate. George Yeardley died in November 1627; at the time he was one of the richest men in the country, if not the very richest.21 He left a will providing that, aside from his house and its contents, which was to go to his wife as it stood,

the rest of my estate consisting of debts, servants [and African and African-American bond-laborers], cattle, or any other thing or things, commodities or profits whatsoever to me belonging or appertaining … together with my plantation of one thousand acres of land at Warwicke River … all and every part and parcell thereof [to be] sold to the best advantage for tobacco and the same to be transported as soon as may be … into England, and there to be sold or turned into money.22

History’s False Apologetics for Chattel Bond-servitude

The bourgeoisie, of whom the investors of capital in colonial schemes were a representative section,23 could have had no more real hope of imposing in England the kind of chattel bond-servitude they were to impose on English workers in Virginia than they had of finding the China Sea by sailing up the Potomac River.24 The matter of labor relations was a settled question before the landing at Jamestown. But the Anglo-American plantation bourgeoisie seized on the devastation brought about by the Powhatan attack of 22 March 1622 to execute a plan for the chattelization of labor in Virginia Colony. There had been dark prophecy, indeed, in the London Company’s response to the news of the 22 March assault on the colony. “[T]he shedding of this blood,” the Company said, “wilbe the Seed of the Plantation,” and it pledged “for the future … instead of Tenants[,] sending you servants.”25 For from that seeding came the plantation of bondage, in the form known to history as “indentured servitude.”

Early in Chapter 4, it was argued from authority that the monstrous social mutation in English class relations instituted in that tiny cell of Anglo-American society was a precondition for the subsequent variation of hereditary chattel bond-servitude imposed on African-Americans in Virginia.26 Historical interpretations of the institution of “indentured servitude” in the Virginia Company period generally anticipate Winthrop D. Jordan’s “unthinking decision” theory of the origin of racial slavery.27 The initial imposition of chattel bond-servitude in continental Anglo-America is justified by its apologists using three propositions:

First proposition: There was a shortage of poor laborers in Virginia, and an abundance of them in England, so that between English laborers, who wanted employment, and plantation investors, who wanted to get rid of prohibitively costly tenantry and wage labor, a quid pro quo was agreed, according to which the employer paid the £6 cost of transportation from England and in exchange the worker agreed to be a chattel bond-laborer for a term of five years or so.28

Second proposition: This form of labor relations was not a sharp disjuncture, but was merely an unreflecting adaptation of some pre-existing form of master-servant relations prevailing in England.

Third proposition: Quid pro quo and English precedents aside, the imposition of chattel bond-servitude was “indispensable” for the “Colony’s progress,” a step opposed only by the “delicate-minded.”29

The “quid pro quo” rationale

The argument for shifting the cost of immigrant transportation from the employer to the worker was in some ways analogous to the rationale advanced by the English ruling classes in the late fourteenth century.30 Because of the plague-induced labor shortage, labor costs rose, and the ruling feudal class and the nascent bourgeoisie sought to recoup as much as possible of the increased cost by introducing a poll tax and increasing feudal dues exacted from the laboring people. Their rationale was that laborers “will not serve unless they receive excessive wages,” and that as a result “[t]he wealth of the nation is in the hands of the workmen and labourers.”31 As rationales go, this was fully as valid as that advanced for indebting the laborers themselves for the cost of their delivery to Virginia. The English feudal lords in the fourteenth century used similar “logic” in trying to persuade “their people” of the impossibility of organizing production if the serf were freed. The great difference in the two cases was that the English laboring classes by the Great Rebellion of 1381 showed that the “impossible arrangement” was, after all, not impossible, while in Virgina rebellion, when it came, would fail.

Given the state of English economic and social development as it was at the beginning of the seventeenth century, under the Elizabethan Statute of Artificers (5 Eliz. 4), the “inevitable” thing would have been to employ free labor – tenants and wage laborers – in the continental colonies, not chattel bond-servitude. If the “inevitable” did not happen in Virginia Colony, it was because the ruling class was favored in the seventeenth-century Chesapeake tobacco colonies by a balance of class forces enabling them to promote their interests in a way they could not have done in England. And they could do so in spite of, rather than because of, the shortage of labor in the colonies. The “payment of passage” was simply a convenient excuse for a policy aimed at reducing labor costs and doing so in a way that was consistent with the free flow of capital. Incidentally, as Abbot Smith concluded, the “four or five years bondage was far more than they [the laborers] justly owed for the privilege of transport.”32 Indeed, producing at the average rate of around 712 pounds of tobacco a year, priced at 18d. per pound, even if the laborer survived only one year, he or she would have repaid more than seven times his or her £6 transportation cost.33 The real consideration was therefore not the recovery by the employer of the cost of the laborer’s transportation, but rather the fastening of a multi-year unpaid bondage on the worker by the fiction of the “debt” for passage.

The contrast of labor-supply situations in Holland and England has been discussed in Chapter 1. There appears to be an instructive corresponding contrast in the Dutch attitude toward binding immigrant workers to long periods of unpaid servitude for the cost of their transportation. On 10 July 1638, Hans Hansen Norman and Andreis Hudde entered into a partnership to raise tobacco “upon the flatland of the Island of Manhates” in New Amsterdam. Hudde was to return to Holland and from there to send to Hudde in New Amsterdam “six or eight persons with implements required” for their plantation. It was agreed that the partners would share the expense of “transportation and engaging them” and of providing them with dwellings and victuals.34 Dutch ship’s captain David Pieterzoon de Vries, who was engaged in the American trade at that same time, despised the bond-labor trade of the English, “a villainous people … [who] would sell their own fathers for servants in the Islands.”35

Bond-servitude was not an adaptation of English practice

The imposition of chattel bondage cannot be regarded as an unreflecting adaptation of English precedents. The oppressiveness of the social and legal conditions of the English workers was outlined in Chapter 2 of this volume.36 But laborers were not to be made unpaid chattels. Except for vagabonds, they had the legal presumption of liberty, a point they themselves had made by rebellion. Except for apprentices and the parish poor, workers were presumed to be self-supporting and bound by yearly contracts, with the provision for three months’ notice of non-renewal. The contract was legally enforceable by civil sanctions, including the requirement of posting bond.37

Under the bond-labor system of Virginia Colony, the worker was presumed to be non-self-supporting; if taken up outside his or her owner’s plantation without the owner’s permission, the laborer, already bound to four or five years of unpaid bondage, was returned to that master and subjected to a further extension of his or her servitude. Above all, the Virginia labor system repudiated the English master-servant law by reducing laborers to chattels.

Nor can the origin of plantation chattel bond-servitude be explained by reference to English apprenticeship.38 Confirmation on this point is to be found in a opinion (citing precedents) written in 1769 by George Mason as a member of the Virginia General Court: “[W]herever there was a trust it could not be transferred … [as in] the case of an apprentice.”39 Under English law, “The binding was to the man, to learn his art, and serve him” and therefore the apprentice was not assignable to a third party, not even the executor of the will of a master who had died.40

Rather than being “a natural outgrowth”41 of English tradition, chattel bond-servitude in Virginia Colony was as strange to the social order in England after the middle of the sixteenth century as Nicotiniana tabacum was to the soil of England before that time;42 and as inimical to democratic development in continental Anglo-America as smoking tobacco is to the healthy human organism.

Was it inevitable? Was it progress?

Just as historians of the eighteenth century have chosen to see the hereditary chattel bondage of African-Americans as a paradoxical requisite for the emergence of the United States Constitutional liberties,43 historians of seventeenth-century Virginia almost unanimously, so far as I have discovered, regard the “innovation” of “indentured servitude” as an indispensable condition for the progressive development of that first Anglo-American colony. It is most remarkable that of the interpreters of seventeenth-century Virginian history only one – Philip Alexander Bruce – has ever undertaken a systematic substantiation of that concept.

Here is a summary of Bruce’s argument:44

The survival of the colony depended upon its being able to supply exports for the English market of sufficient value to pay for the colony’s needs for English goods. The economy of the colony was necessarily shaped by its immediate economic interests. Tobacco alone would serve both of those purposes. Since maize – Indian corn – was not then appealing to the European palate, wheat was the nearest possible export rival to tobacco. But wheat required more land for the employment of a given amount of labor for the production of equal exchange-value in tobacco, and much more labor for clearing of the forested land for its profitable exploitation; furthermore, wheat in storage was much more vulnerable to rat and other infestation and required much larger ship tonnage for delivery than did tobacco of equal value.

In order to make profitable use of land acquired by multiple headrights or the equivalent by other means, the owner had to employ more labor than that of his immediate family. Tenantry was not adaptable for this purpose because landowners were not eager to rent out newly cleared land whose fertility would be exhausted in three years, and tenants were not willing to lease land that was already overworked when they could take out patents on land of their own at a nominal quit-rent of two shillings per hundred acres.45 Labor being in short supply, wage laborers commanded such high wages that they too would have good prospects of acquiring land of their own, and thus of ceasing to be available for proletarian service.

Chattel bondage as the basic general form of production relations was therefore indispensable for the progress of the colony of Virginia.

It seems reasonable to believe that Bruce was aware that tenantry became a significant part of the agricultural economy in eighteenth-century Chesapeake. Allan Kulikoff’s study indicates that in southern Maryland and the Northern Neck and Fairfax County in Virginia one-third to half of the land was occupied by tenants.46 In Virginia, on new ground the first tenant was excused from paying rent for the first two years of the lease. This exemption for payment of fees and rent was “a most advantageous arrangement,” writes Willard Bliss, so that, far from being unfeasible, “tenancy was a logical solution” to planters’ problems.47 The rise of tenancy that began in Virginia early in the eighteenth century, particularly in the Northern Neck, was a function of plantation capitalism, which was by then recruiting its main productive labor from African and African-American bond-laborers.48 The most directly profitable exploitation of their labor was in the production of tobacco, not in clearing new ground, pulling stumps, ditching, fencing, etcetera. For that work, rent-paying tenants were to be employed.

In Maryland, English and other European laborers who survived their servitude were formally entitled to a fifty-acre headright, but to acquire the promised land was “simply impracticable.”49 They generally became tenants of landlords who needed to have their land cleared and otherwise improved for use as tobacco plantation land, or to build up their equity for speculative purposes.50 In Prince George’s County one-third of the householders were tenants by 1705.51

These facts would seem to cast doubt on Bruce’s argument that the clearing of land could not have been done on the basis of tenancy. The key in both the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was neither technical difficulty nor any economic impossibility of getting tenants to clear the land, but the owners’ calculation of the rate of profit. In the seventeenth century the cheapest way to clear land was not by using tenants, but by using bond-laborers; in the eighteenth century, the cheapest way to clear land was not by using bond-laborers, but by using tenants. It was the work of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,”52 and, in today’s popular phrase, the logic of the “bottom line.”

But what was the “bottom line” to the people on the bottom, who were being degraded from tenants and wage laborers to chattels? What good to them was an “invisible hand” systematically dealing from the bottom of the deck against the laboring class? Bruce answers with one word, “progress”; yet even as he does so, he concedes that after all bond-servitude was not inevitable, although he contends the alternative would have been undesirable. Without chattel bondage, he says:

[t]he surface of the colony would have been covered with a succession of small estates, many of which would have fallen into a condition of absolute neglect as soon as their fertility had disappeared, their owners having sued out patents to virgin lands in other localities as likely to yield large returns to the cultivator.… [The] Colony’s progress would have been slow. Virginia without [chattel bond-] laborers from England and without slaves would have become a community of peasant proprietors, each clearing and working his ground with his own hands and with the aid of his immediate family.53

However unpalatable such an alternative may have seemed to Bruce, there were others who showed by word and deed over a span of two and a half centuries in Virginia that they would have assessed the matter differently, had they been given the choice between the life of peasant proprietors and that of unpaid chattel bond-laborers.54 In New England an alternative practice was followed, as will be discussed in Chapter 9.

Francis Bacon’s Alternative Vision: “Of Plantations”

Bruce takes note of Sir Francis Bacon’s essay “Of Plantations,” dated 1625, the year after the dissolution of the Virginia Company;55 but while he does not attempt to discuss it in detail, he obviously does not find it persuasive.56

Planting of countries is like planting of woods [wrote Sir Francis]; for you must take into account to lose almost twenty years profit, and expect your recompense in the end; for the principal thing that hath been the destruction of most plantations, has been the hasty drawing of profit in the first years. It is true, speedy profit is not to be neglected, as may stand with the good of the plantation, but not farther.

To this end, it was essential, Bacon said, to keep control out of the hands of the merchants, the most typical form of bourgeois life at that time, “for they look ever to the present gain.”57 The labor of the colonists should be first turned to the cultivation of native plants (among other things, Bacon mentions maize) in order to assure the colony’s food supply. Bacon further advised, “Let the main part of the ground employed to gardens or corn be a common stock; and to be laid in and stored up, and then delivered out in proportions.” Next, native products should be developed as commodities to be exchanged for goods that must be imported by the colony – but not, Bacon warned, “to the untimely prejudice of the main business; as it hath fared with tobacco in Virginia.”58

Bacon’s thesis seems to have anticipated Bruce’s argument, and to refute in advance any attempt to justify the dominance of “immediate needs” and the plantation monocultural base of colonial development.

The record itself – the public and private correspondence, the Company and colony policy statements, laws and regulations, the court proceedings and decrees – presents much evidence of contradictory views within the ruling councils during the Company period. The Company and colony officials inveigh against the inordinate attention given to tobacco growing, while presiding over the ineradicable establishment of the tobacco monoculture, using tobacco for money, squabbling over its exchange-value, staking all on the “tobacco contract.” The Company expresses concern over the abuse of the rights of servants while pressing helpless young people in England for service in the plantation. The Company in London continues to send boatloads of emigrants to Virginia without the proper complement of supplies to tide them over till their first crops can be harvested, while the Colony Council in Virginia demands that settlers not be sent without provisions. The colony officials complain that too many ill-provisioned laborers are being sent, and yet at the same time, they deplore the scarcity of “servants … our principal wealth,” and the high wages due to that scarcity.

In puzzling out such apparent antinomies of sentiment, one must make due allowance for the effect of partisan conflicts within the Virginia Company. But as Craven points out, indictments of the treatment of laborers and tenants, or criticism of the tobacco contract with the king,59 may have been to some extent inspired by factional interests, but that does not invalidate them.60 When the dust had settled, the transformation of production relations by “changing tenants to servants” had developed from a proposal by the Virginia Colony Council into the prevailing policy of the Anglo-American plantation bourgeoisie as a whole, London “adventurers” as well as Virginia “planters.” In all the documents involved in the transfer of the affairs of the colony to royal control, no trace remains of the urgent concern with registration of contracts, abuse of servants, etcetera, ideas that the worried friends and kindred of those gone to Virginia had pressed on the Company Court.

Nevertheless, the substantial opposition within the Company to the chattelization of labor provides strong evidence that the options for monoculture and bond-servitude were not “unthinking decisions.” The “quid pro quo” rationale for chattel bond-servitude was denounced as repugnant to English constitutional liberties and common law,61 and to the explicit terms of the Royal Charter for the Virginia colony.62 This concern was reflected in the “exceeding discontent and griefe [of] divers persons coming daylie from the farthest partes of England to enquire of friends and Kindred gonn to Virginia.”63 In October 1622, the Virginia Company established a Committee on Petitions, one of whose tasks was to consider wrongs done to “servants” sent to Virginia,64

It beinge observed here that divers old Planters and others did allure and beguile divers younge persons and others (ignorant and unskillfull in such matters) to serve them upon intollerable and unchristianlike conditions upon promises of such rewardes and recompense, as they were in no wayes able to performe nor ever meant.

First among the “abuses in Carriing over of Servants into Virginia” was the following:65

divers ungodly people that have onely respect of their owne profitt do allure and entice younge and simple people to be at the whole charge of transportinge themselves and yet for divers years to binde themselves Servants to them …

The remedy was not to be found at that time by strict regulation and control of emigration to Virginia, with a written contract for every worker of which a copy would be kept in Company files.66 If, in those famine years, 1622–23, laborers had come to Virginia with a contract sealed with seven seals, they would still have surely starved if they could not pay twenty shillings for a bushel of corn, unless they were able to find a master who would let them work for mere corn diet and, perhaps, a place to sleep.

It was not the way it was supposed to be. Even those who had never heard of the Statute of Artificers knew as much. “Sold … like a damd slave!” raged Thomas Best, cursing his lot.67 Henry Brigg had come to Virginia having Mr Atkins’s promise that Brigg would never serve any other master. But now, in the spring of 1623, he wrote his brother, who had been witness to the promise, “my Master Atkins hath sold me & the rest of my Fellowes.”68

Young Abraham Pelterre was favored to have a mother in England with some influence with her aldermen. They protested with some effect when they learned that Abraham was being sold from hand to hand in Virginia contrary to the proper conditions of apprenticeship.69 They knew it was wrong.

Jane Dickinson knew that it was not a thing that could happen in England, and she asked the General Court to see it her way. She had come to Virginia in 1620 with her husband Ralph, a seven-year tenant-at-halves for Nicholas Hide. Her husband was killed in the attack of 22 March 1622, and she was taken captive by the Indians. After ten months, she and a number of other captives were released for small ransoms. Jane’s master had died in the meantime. Dr John Pott, who paid her ransom, two pounds of glass beads, demanded that she serve him as a bond-laborer for the unexpired time of her husband’s engagement, saying that she was doubly bound to his service by the two pounds of glass laid out for her ransom. The only alternative, he told her, was to buy herself from him with 150 pounds of tobacco70 (at the prevailing price of 18d. per pound, this would have been worth nearly twice the £6 cost of her transportation from England).

John Loyde knew that in England if a master died his apprentice was freed, or, perhaps, remained bound to the master’s widow. After paying his master £30 to be taken on as an apprentice, and receiving his copy of the appropriate papers for the arrangement, Loyde embarked for Virginia with his master, taking with him the terms of his apprenticeship in writing. His master died en route, but the ship’s captain had taken his papers that would have established his free status. Without them, Loyde was subject to being sold by the ship’s captain into chattel bondage. Loyde sued in court to recover the papers.71

William Weston knew it was wrong. In November 1625, he was fined 250 pounds of good merchantable tobacco for failing to bring a servant into Virginia for Robert Thresher. The next month Weston was before the General Court again, and it was testified that, when again asked to bring servants to Virginia

Mr Weston replied he would bring none, if he would give him a hundred pownde. Mr Newman [who wanted to place an order] asked him why. And Mr Weston replied that … servants were sold here upp and down like horses, and therefore he held it not lawfull to carry any.72

John Joyce, bond-laborer, knew in his aching bones that it was not right; and in August 1626 he sought to reestablish by direct action the capitalist principle of two-way freedom of labor relations. He did not take his case to the General Court, however, preferring the mercy of the wilderness. (Captured by the colony authorities, as noted in Chapter 5, he had the distinction of being the first such fugitive bond-laborer who is recorded as being sentenced to an extension of his servitude time as punishment for his offense. He had six months added to his term with his master, and at the completion of that extended term he was to serve five years more as bond-servant to the colony authorities. It was all to begin with a brutal lashing of thirty stripes.)73

And so it came to pass that seventy-five years after the institution of the labor relations principles of the Statute of Artificers, when the good ship Tristram and Jane arrived in Virginia in 1637, all but two of its seventy-six passengers were bond-laborers to be offered for sale.74 The following year, Colony Secretary Richard Kemp reported to the English government, “Of hundreds of people who arrive in the colony yearly, scarce any but are brought in as merchandize for sale.”75

The Problem of Social Control Enters a New Context

There was another side to the coin of the option by the tobacco bourgeoisie for the anomalous system of bond-servitude as the basis of capitalist production in Virginia Colony. In the sixteenth century, as has been discussed, the English governing classes made a deliberate decision to preserve a section of the peasantry from dispossession by enclosures, in order to maintain the yeomanry as a major element in the intermediate social control stratum essential to a society without an expensive large standing army.76 The military regime that the Virginia Company first installed under governors Gates and Dale, for all its severity, proved ultimately ineffective. That particular variant of social control had to be superseded because of defiance of the limitations on tobacco cultivation by laboring-class tenants – Rolfe’s “Farmors” – who represented the potential yeoman-like recruits for an intermediate social control stratum for the colony.77

Following their instinct for “present profit,” the plantation bourgeoisie on the Tobacco Coast forgot or disregarded the lesson taught by the history of the reign of Henry VII and the deliberate decision to preserve a forty-shilling freehold yeomanry.78 Instead, convinced that the tenant class was an “absurdity”79 from the standpoint of profit making in a declining tobacco market, the Adventurers and Planters decided to destroy the tenantry as a luxury they could not afford.

Perhaps there was special significance in the fact that it was a son of the yeoman class, Captain John Smith, who sounded the warning for those who were forsaking the wisdom of insuring the existence of an adequate yeomanry. Condemning the traders in bond-labor, he said, “it were better they were made such merchandize themselves, [than] suffered any longer to use that trade.” That practice, said Smith prophetically, was a defect “sufficient to bring a well setled Common-wealth to misery, much more Virginia.”80

Figure 1 Map of the Chesapeake region, circa 1700

This map of Virginia and Maryland was graciously copied for me by the Map Division of the New York 1629). This engraving of the map by Francis Lamb, although not dated, would seem to represent an “up-abbreviated as “C.”). Virginia was not divided into counties (first called “shires”) until 1634. The New York formed in 1669, and does not mention any of the next three counties, which were formed in 1691, it seems parallel to the lines of almost all of the printed text), it shows details with great clarity. The Atlantic Ocean came to the Chesapeake by sailing north from the West Indies. I myself have labeled West Point, the region slavery” in 1676 (see Chapter 11).

Public Library Research Libraries, whose map catalog identifies the cartographer as John Speed (1542-dated” version of Speed’s work, to judge, for instance, from its identification of counties (“County” being Public Library catalog tentatively assigns “1666?” to this version. But since it includes Middlesex County, that this map should be dated sometime in the 1669–91 period. Despite its orientation (the North arrow is is here called “The North Sea,” the designation presumably given to these waters by the English who first in which “four hundred English and Negroes in Armes” joined in the demand for “freedom from their

Figure 2 List of governors of Colonial Virginia

An attempt has been made to give as nearly as possible the dates of actual service of each of the men who acted as colonial governor in Virginia. The date of commission is usually much earlier.

President of the Council in Virginia

Edward-Maria Wingfield, May 14–September 10, 1607.

John Ratcliffe, September 10, 1607–September 10?, 1608.

John Smith, September 10, 1608–September 10?, 1609.

George Percy, September 10?, 1609–May 23, 1610.

The Virginia Company

Thomas West, Third Lord De La Warr, Governor. February 28, 1610–June 7, 1618.

Sir Thomas Gates, Lieutenant-Governor. May 23–June 10, 1610.

Thomas West, Lord De La Warr, Governor. June 10, 1610–March 28, 1611.

George Percy, Deputy-Governor. March 28–May 19, 1611.

Sir Thomas Dale, Deputy-Governor. May 19–August 2?, 1611.

Sir Thomas Gates, Lieutenant-Governor. August 2?, 1611–c. March 1, 1614.

Sir Thomas Dale, Deputy-Governor, c. March 1, 1614–April?, 1616.

George Yeardley, Deputy-Governor. April?, 1616–May 15, 1617.

Samuel Argall, Present Governor. May 15, 1617–c. April 10, 1619.

Nathaniel Powell, Deputy-Governor. c. April 10–18, 1619.

Sir George Yeardley, Governor. April 18, 1619–November 18, 1621.

Sir Francis Wyatt, Governor. November 18, 1621–c. May 17, 1626.

Royal Province

Sir George Yeardley. May?, 1626–November 13, 1627.

Francis West. November 14, 1627–c. March, 1629.

Doctor John Pott. March 5, 1629–March?, 1630.

Sir John Harvey. March?, 1630–April 28, 1635.

John West. May 7, 1635–January 18, 1637.

Sir John Harvey. January 18, 1637–November?, 1639.

Sir Francis Wyatt. November?, 1639–February, 1642.

Sir William Berkeley. February, 1642–March 12, 1652.

(Richard Kemp, Deputy-Governor. June, 1644–June 7, 1645.)

The Commonwealth

Richard Bennett. April 30, 1652–March 31, 1655.

Edward Digges. March 31, 1655–December, 1656.

Samuel Mathews. December, 1656–January, 1660.

Sir William Berkeley. March, 1660.

Royal Province

Sir William Berkeley. March, 1660–April 27, 1677.

(Francis Moryson, Deputy-Governor. April 30, 1661–November or December, 1662.)

Colonel Herbert Jeffreys, Lieutenant-Governor. April 27, 1677–December 17, 1678.

Thomas Lord Culpeper, Governor. July 20, 1677–August, 1683.

(Sir Henry Chicheley, Deputy-Governor. December 30, 1678–May 10, 1680; August 11, 1680–December 1, 1682.)

(Nicholas Spencer, Deputy-Governor. May 22, 1683–February 21, 1684.)

Francis, Lord Howard, Fifth Baron of Effingham, Governor. February 21, 1684–March 1, 1692.

(Nathaniel Bacon, Sr., Deputy-Governor. June 19–c. September, 1684; July 1,–c. September 1, 1687; February 27?, 1689-June 3, 1690.)

Francis Nicholson, Lieutenant-Governor. June 3, 1690–September 20, 1692.

Sir Edmund Andros, Governor. September 20, 1692–December 9?, 1698.

(Ralph Wormeley, Deputy-Governor. September 25–c. October 6, 1693.)

Francis Nicholson, Governor. December 9, 1698–August 15, 1705.

(William Byrd, Deputy-Governor. September 4–October 24, 1700; April 26–June, 1703; August 9–September 12–28, 1704.)

Lord George Hamilton, Earl of Orkney, Governor. 1704–January 29, 1737.

Edward Nott, Lieutenant-Governor. August 15, 1705–August 23, 1706.

(Edmund Jenings, Deputy-Governor. August 27, 1706–June 23, 1710.)

(Robert Hunter was made Lieutenant-Governor April 22, 1707, but never took his office.)

Alexander Spotswood, Lieutenant-Governor. June 23, 1710–September 25?, 1722.

Hugh Drysdale, Lieutenant-Governor. September 25, 1722–July 22, 1726.

(Robert Carter, Deputy-Governor. July, 1726–September 11, 1727.)

William Gooch, Lieutenant-Governor. September 11, 1727–June 20, 1749.

(Reverend James Blair, Deputy-Governor. October 15, 1740–July?, 1741.)

William Anne Keppel, Second Earl of Albemarle, Governor. October 6, 1737–December 22, 1754.

(John Robinson, Sr., Deputy-Governor. June 20–September 5, 1749.)

(Thomas Lee, Deputy-Governor. September 5, 1749–November 14, 1750.)

(Lewis Burwell, Deputy-Governor. November 14, 1750–November 21, 1751.)

Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-Governor. November 21, 1751–January 2–12, 1758.

(John Blair, Deputy-Governor. January–June 7, 1758.)

John Campbell, Fourth Earl of Loudoun, Governor. March 8, 1756–December 30, 1757.

Sir Jeffrey Amherst, Governor. September 25, 1759–1768.

Francis Fauquier, Lieutenant-Governor. June 7, 1758–March 3, 1768.

(John Blair, Acting-Governor. March 4–October 26, 1768.)

Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt, Governor. October 26, 1768–October 15, 1770.

(William Nelson, Acting-Governor. October 15, 1770–September 25, 1771.)

John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore, Governor. September 25, 1771–May 6, 1776.

The State

Patrick Henry. July 5, 1776–June 1, 1779.

Thomas Jefferson. June 1, 1779–June 12, 1781.

Thomas Nelson. June 12, 1781–November 30, 1781.

Benjamin Harrison. November 30, 1781–November 30, 1784.

Source: William W. Abbot, A Virginia Chronology, 1585–1783, Richmond, 1957, this page–this page

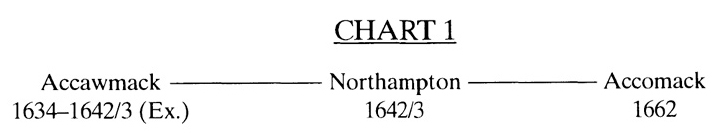

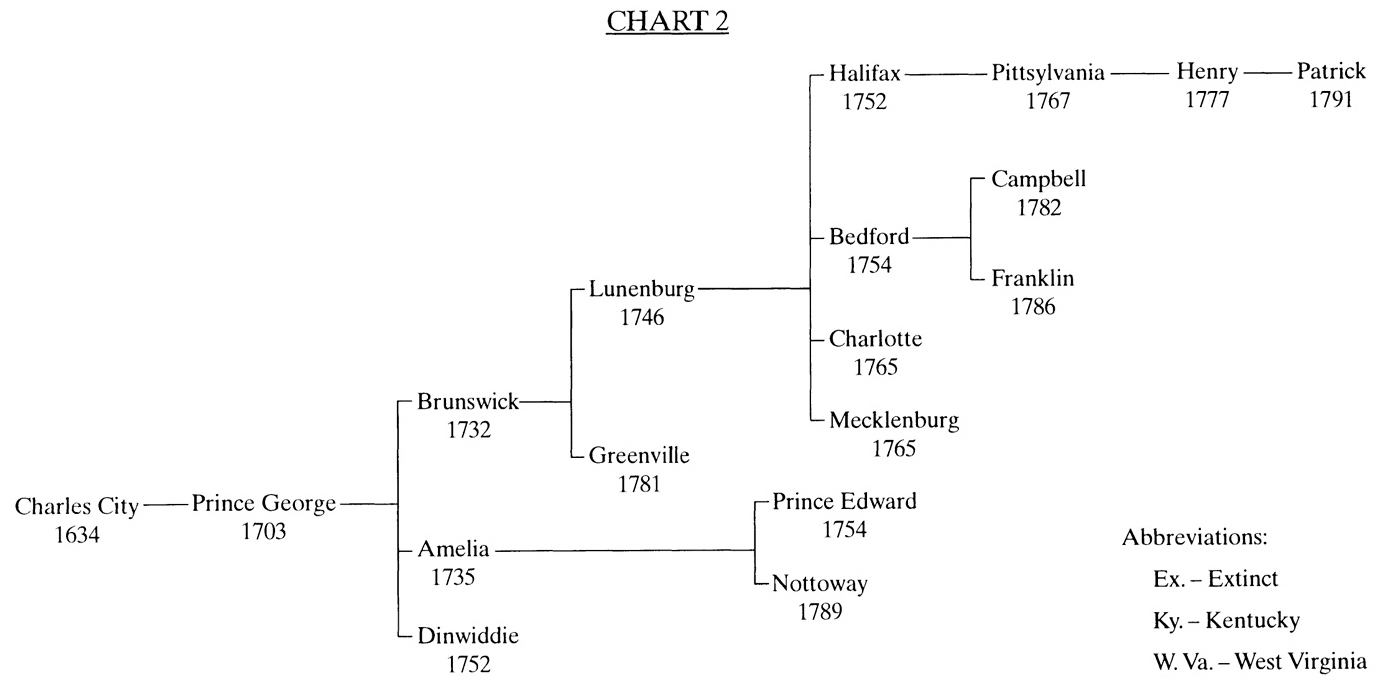

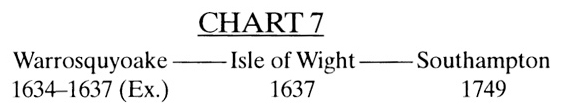

Figure 3 Virginia counties, and dates of their formation

Source: Martha W. Hiden, How Justice Grew: Virginia Counties, Richmond, 1957, this page–this page