6

Global conquerors

Today, humans are found on every continent on Earth. But it was not always thus. Although not everyone agrees, our species seems to have had its origins in Africa, and to have spread from there. But even the date of our species’ origin is tricky to pin down, and the tale of how we went global is more puzzling still.

The origin of our species

For much of the twentieth century, Homo sapiens was thought to have evolved just 100,000 years ago. However, since the 1990s a consensus has grown that anatomically modern humans emerged in Africa at least 200,000 years ago.

This shift in thinking began in 1987. Using genetic analysis to construct an evolutionary tree of mitochondrial DNA – genetic material we inherit solely from our mothers – researchers found that we can all trace our ancestry back to a single woman who lived in East Africa some 200,000 to 150,000 years ago – the so-called ‘mitochondrial Eve’.

The case for such early origins has since been boosted by fossil evidence. In 2003 researchers dated fossil remains of H. sapiens from Herto in Ethiopia at about 160,000 years old. Two years later another team pushed our origins even further back, dating fossil remains found at Omo Kibish, Ethiopia, to 195,000 years ago.

But some researchers have long suspected that the roots of our species are even deeper, given that H. sapiens-like fossils in South Africa have been tentatively dated to 260,000 years ago. Fossils found in Morocco in 2017 suggest that the H. sapiens lineage became distinct as early as 350,000 years ago – adding as much as 150,000 years to our species’ history.

This new evidence came from a site called Jebel Irhoud, where hominin remains had been found in the 1960s, although nobody then could make sense of them. So scientists returned to Jebel Irhoud to try to solve the puzzle. In fresh excavations, they found stone tools and more fragmentary hominin remains, including pieces from an adult skull. An analysis of the new fossils, and of those found at the site in the 1960s, confirmed that the hominins had a primitive, elongated braincase. But the new adult skull showed that the hominins combined this ancient feature with a small, lightly built ‘modern’ face – one virtually indistinguishable from that of H. sapiens (see Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 A reconstruction of the earliest known Homo sapiens fossils

Another study examined the stone tools. Many of them had been baked – probably because they were discarded after use and then heated when the hominins set fires on the ground nearby.

This heating ‘resets’ the tools’ response to natural radiation in the environment. By assessing the levels of radiation at the site and measuring the radiation response in the tools, researchers established that the tools were heated between 280,000 and 350,000 years ago. They also redated one of the hominin fossils found in the 1960s and concluded that it is 250,000 to 320,000 years old.

Armed with these dates, the Moroccan hominins seem easier to understand. The researchers suggested that H. sapiens had begun to emerge – literally face-first – between about 250,000 and 350,000 years ago.

Going global

Long before the Nike logo and McDonald’s golden arches straddled the planet, our own species had penetrated every corner of the globe. But it took a while. It seems that our species remained in Africa for tens of thousands of years before going global: ‘all dressed up and going nowhere’, as one archaeologist put it.

Skeletal remains from Skhul and Qafzeh in Israel dating from 120,000 to 90,000 years ago are the oldest confirmed traces of modern humans outside Africa. Discovered in the 1930s, these were once thought to represent the leading edge of a successful wave of colonization that would take our newly evolved species north and west into Europe and, eventually, eastward across the globe.

However, all evidence of human habitation beyond Africa disappears around 90,000 years ago, only to emerge again much later. The finds in Israel are widely believed to represent a precocious but short-lived surge of humanity into the wider world. Yet the crucial questions remain: why did humans leave Africa when they did, and what enabled them to achieve world domination this time, where previous migrations had petered out?

Richard Klein, an anthropologist at Stanford University in California, has championed the idea that fully modern behaviour appeared in a relatively sudden burst around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. Such behaviours encompass the manufacture and use of complex bone and stone tools, efficient and intensive exploitation of local food resources and, perhaps most significantly, symbolic ornamentation and artistic expression. This ‘cultural great leap forward’ tipped humans over into modernity and equipped them with the creativity, the skills and the tools they needed to conquer the rest of the world.

By contrast, other researchers believe that the behavioural modernity that underpins the human success story evolved much earlier. They point to a growing array of artefacts that date back to 80,000 years ago (see Chapter 8). It is possible, however, that such finds might simply reflect a gradual accumulation of more modern behavioural patterns rather than the appearance of fully modern minds. If you look at the archaeological record between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago, you find occasional artefacts that seem to be indicative of modern behaviour, but they remain rare.

In 2006 Paul Mellars of the University of Cambridge proposed a new model to explain the out-of-Africa diaspora that aimed to tie together these controversial archaeological remains with recent genetic findings. The key pieces of the puzzle were genetic studies that pointed to a series of population explosions, first in Africa and later in Asia and then Europe.

Rapid population growth leaves a telltale signature in the number of differences in mitochondrial DNA between pairs of individuals within a specific population: as the time since the population explosion increases, so do the DNA mismatches. This analysis shows that African populations were increasing rapidly 80,000 to 60,000 years ago, neatly matching the evidence for an early flowering of behavioural modernity.

According to Mellars’s model, human behaviour was altering between 80,000 and 70,000 years ago in ways that led to major technological and social changes in southern and eastern Africa. Key innovations, including improved weaponry for hunting, new use of starchy wild plants for eating, the expansion of trading networks, and possibly the discovery of how to catch fish, enabled modern humans to make a better living off the land and sea. Mellars argued that all this led to a massive and rapid population expansion, perhaps in just a small source region in Africa, between 70,000 and 60,000 years ago. This growing population, equipped with more complex technology, was finally able to push out of Africa and into southern Asia from around 65,000 years ago.

The human story has always been hotly contested. Now, at last, a basic plot is finally taking shape. But none of the plot points has been settled for good, beginning with a seemingly simple question: what route did we take out of Africa?

Out of Africa – but how?

The route that our ancestors took out of Africa has been repeatedly re-evaluated and is still not firmly agreed.

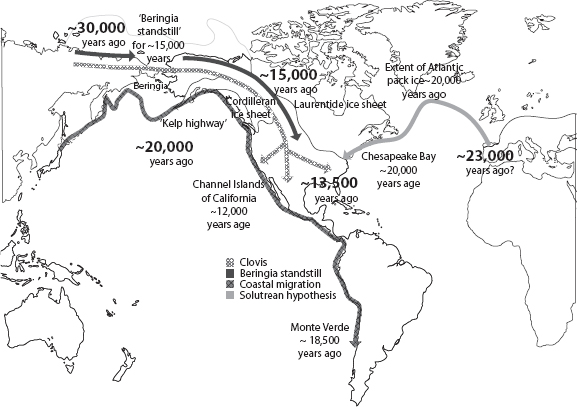

Based on the evidence of the early occupation of the Middle East, the idea took hold that when early modern humans eventually began their global migration, they took a ‘northern route’ through the Levant (essentially, the land immediately east of the Mediterranean) and up into Europe. But this has been challenged: other discoveries point to early and widespread occupation of South East Asia and Australasia, with migration to the north and then west into Europe happening later (see Figure 6.2).

FIGURE 6.2 The migration routes out of Africa of anatomically modern humans. Evidence from fossils, ancient artefacts and genetic analysis combines to tell a compelling story.

For example, in 2007 skeletal remains found in Niah Cave in Sarawak, on the island of Borneo, were dated to between 45,000 and 40,000 years old. Added to these are some fossils from Tianyuan Cave, near Beijing, China, also described in 2007, which are 40,000 years of age.

While some of our ancestors explored the far east of Asia, other groups were beginning to enter Europe. Skeletal remains from Peștera cu Oase, a cave in Romania, also date to about 40,000 years old. The oldest fossils in Western Europe are slightly younger, between 37,000 and 36,000 years old. Only the Americas seem to have been colonized much later, towards the end of the last ice age.

There is also genetic evidence for the later spread into Europe. Spencer Wells of the University of Texas at Austin has charted the geographic distribution of genetic markers on the Y chromosome of men now living in Eurasia. He found that about 40,000 years ago populations started to diverge in the Middle East, some moving south into India and others moving north through the Caucasus and then splitting into a westward arm that led across northern Europe and an eastward arm reaching across Russia and into Siberia.

These later migrations would have taken people into the heart of Eurasia, but it seems likely that the first migrants skirted the coast – perhaps leaving the continent from the Horn of Africa, crossing a then-narrower Bab el-Mandeb Strait, swinging around the Arabian Peninsula, past Iraq, and then following the coast of Iran to the east – a single dispersal along the ‘southern route’. This coastal route makes perfect ecological sense. Early modern humans were clearly able to exploit the resources of the sea, as attested to by dumps of clam and oyster shells found in Eritrea in East Africa, dating from around 125,000 years ago. Sticking with what they knew, beachcombing H. sapiens would have been able to move rapidly along the coastline without having to invent new ways of making a living or adapting to unfamiliar ecological conditions.

Archaeological traces of migration along the southern coastal route are patchy but consistent with this picture. But there is also plenty of evidence to support the traditional idea of the northern route. For instance, ancient rivers, whose remains are now lying beneath the Sahara Desert, once formed green corridors at the surface, which our ancestors could have followed on their great trek out of Africa.

Similarly, a 2015 genomic analysis of hundreds of people from the area suggests that we took the northern route through Egypt into Eurasia. This conclusion fits well with other evidence. In particular, Eurasians interbred with Neanderthals soon after they left Africa – and while we know that Neanderthals lingered in the Levant at about the time of the out-of-Africa migration, there is no evidence that they lived further south.

At this point you might be wondering whether, given that there seems to be evidence to support both routes out of Africa, early humans might not simply have followed both. This might accord with the archaeology, but three genetic analyses published in 2016 all suggest that there was only one wave of migration. It seems that all non-Africans living today can trace the vast majority of their ancestry to one group of pioneers who left Africa in a single wave.

An earlier exodus?

Even the date of our departure from Africa is not entirely agreed upon. Our direct ancestors may have found their way out of Africa much earlier than we think.

Jin Changzhu and colleagues of the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology in Beijing announced in 2009 that they had uncovered a 110,000-year-old putative Homo sapiens jawbone from a cave in southern China’s Guangxi Province. The mandible has a protruding chin like that of Homo sapiens but the thickness of the jaw is indicative of more primitive hominins, suggesting that the fossil could derive from interbreeding. Other anthropologists questioned whether the find was a true Homo sapiens.

The global spread of modern humans

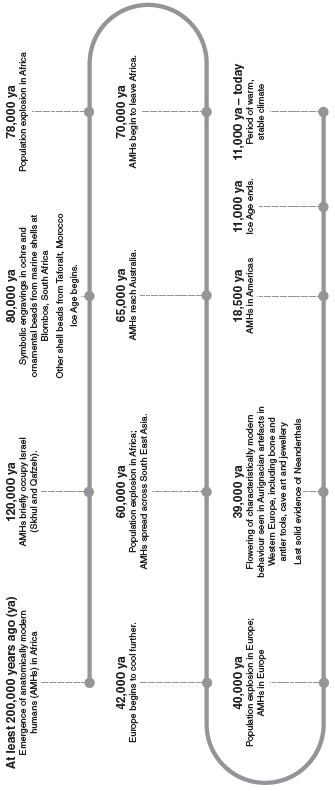

As always, dates for these events are fluid. There is now evidence of human artefacts in Australia 65,000 years ago, which is older than anything yet found in Asia. That discrepancy has still to be resolved.

In 2014 another research group described two teeth from the Luna Cave in China’s Guangxi Zhuang region. Based on the proportions of the teeth, the group argued that at least one of them must have belonged to an early Homo sapiens. The teeth were clearly old. Calcite crystals, which formed as water flowed over the teeth and the cave floor, date them to between 70,000 and 125,000 years ago. Again, it is not clear that the teeth belong to modern humans.

However, other fossils are more convincing. Bones found in Israel, including an upper jaw from Misliya Cave, could be 150,000 years old. In China, a jawbone and two molars were found in Zhirendong, a cave in Guizhou Province. Although the bone is over 100,000 years old, the shape of its chin is suggestive of modern humans.

Similarly, in 2015 María Martinón-Torres of University College London and her team found 47 teeth, belonging to at least 13 H. sapiens individuals, in Fuyan Cave in Daoxian, Hunan Province, south-east China. The teeth were found under a layer of stalagmites that formed after the teeth were deposited there. The stalagmites are at least 80,000 years old, so the teeth seem to be at least that old. Investigation of animal bones at the same site puts their upper age limit at 120,000 years old.

A closer look at the genetics also suggests that there was an earlier migration. In 2014 Katerina Harvati of the University of Tübingen in Germany and her colleagues tested the classic ‘out of Africa at 60,000 years ago’ story against the earlier-exodus idea. They plugged the genomes of indigenous populations from South East Asia into a migration model. They found that the genetic data was best explained by an early exodus that left Africa 130,000 years ago, taking a coastal route along the Arabian Peninsula, India and into Australia, followed by a later wave along the classic northern route through Egypt.

The conquest of Europe

When the first modern humans entered Europe, they found the Neanderthals already there. What happened next?

Not too long ago, that story appeared beguilingly simple. Our species arrived 45,000 years ago from the Middle East, outcompeted the Neanderthals, and that was that. But since 2010 scientists have used fragments of DNA pulled out of ancient bones to probe Europe’s genetic make-up. Together they tell a more detailed, colourful tale: three waves of H. sapiens shaped the continent. Each came with its own skills and traits. Together they would lay the foundations for a new civilization.

Our distant ancestors – probably Homo erectus – first settled in Europe at least 1.2 million years ago. By 200,000 years ago they had become Neanderthals. We know from their DNA that at least some of them had pale skin and red hair. They lived in caves, had basic stone tools, and hunted and fished along European shorelines. Some probably wore forms of decoration such as shell necklaces and might even have etched simple signs in the rocks of the Iberian Peninsula.

All told, they were relatively sophisticated, but they were no match for a group of dark-skinned hunter-gatherers who arrived from the Middle East around 45,000 years ago. By 39,000 years ago the Neanderthals were history. The newcomers flourished in Europe’s forests, hunting the woolly rhinoceros and bison that lived there. Long before farmers tamed cows and sheep, these early Europeans made friends with wolves. Like the Neanderthals, some of them lived at the mouths of caves – sometimes the very same caves – which they lit and heated with roaring fires. Like them, they ate berries, nuts, fish and game.

For 30,000 years the hunter-gatherers had Europe largely to themselves. Then, about 9,000 years ago, Neolithic farmers arrived from the Middle East and began spreading through southern and central Europe. They brought their understanding of how to collect and sow seeds, as well as the staples of modern European diets. The basic livestock of Europe today, with a few exceptions such as chickens, arrived then.

With farming came a more sedentary and recognizably modern lifestyle. Villages became a much more common fixture. Some archaeological sites have distinct rows of houses. A settled lifestyle made it harder to relocate if conflicts arose between neighbouring tribes, so they would often be resolved with mass violence. But, fundamentally, life in early Neolithic Europe was still relatively insular. The final, missing ingredient, the one that would truly lay the flagstones for a European civilization, was still a few thousand years off.

Archaeologists have long debated the existence of another great prehistoric migration into Europe – one that brought in a mysterious group from the Eurasian steppe. The Yamnaya, so the argument went, founded some of the late Neolithic and Copper Age cultures, including the vast Corded Ware culture – named after its distinctive style of pottery – that stretched from the Netherlands to central Russia.

The weight of archaeological opinion had been against this idea, but that may be about to change. A 2014 study of ancient DNA offered the first compelling evidence that a third ancient population did shape the modern European gene pool, and that it originated in northern Eurasia. With the curious exception of the blond hunter-gatherers from Sweden, there were no signs of this population in the genes of early farmers or hunter-gatherers. So the people carrying the genes must have become common in Europe some time after most farmers arrived.

Two separate studies link the arrival of these genes to a massive Yamnaya migration into Europe about 4,500 years ago. They found that 75 per cent of the genetic markers of skeletons associated with Corded Ware artefacts unearthed in Germany could be traced to Yamnaya bones previously unearthed in Russia. In other words, the genetic testimony provides tantalizing evidence that there really was a massive influx of Yamnaya people into Europe around 4,500 years ago.

The Yamnaya were cattle herders. Until about 5,500 years ago their settlements clung to the river valleys of the Eurasian steppes – the only places where they had easy access to the water they and their livestock needed. The invention of a single, revolutionary technology changed everything. We know from linguistic studies that the Yamnaya rode horses and, crucially, had fully embraced the freedom that came with the wheel.

With wagons, they could take water and food wherever they wanted, and the archaeological record shows that they began to occupy vast territories. This change may have led to fundamental shifts in how Yamnaya society was structured before they left the steppes. Groups roamed into one another’s territories, so a political framework emerged that obliged tribal leaders to offer wanderers safe passage and protection. If this is correct, then it is easy to imagine that the Yamnaya brought this new political framework with them as they ventured west.

The land of Oz

How and when people first reached Australia is still being worked out. Until 2017 the oldest known human remains from Australia belonged to a skeleton dubbed Mungo Man, discovered at Lake Mungo in south-eastern Australia in 1974. Experts argued for decades about the age of the skeleton. But in 2003 it was confirmed that Mungo Man lived 40,000 years ago.

That fits with the out-of-Africa story. It also supports the idea that early humans drove Australia’s large mammals to extinction. Evidence that people spread rapidly across Australia around 50,000 years ago would support the ‘blitzkrieg’ theory of the extinction of the continent’s large mammals soon after humans arrived. In line with this, a 2016 study suggested that the first humans to reach Australia quickly migrated into its hot, dry interior, and developed tools to adapt to the tough environment and exploit its giant beasts.

However, the story was turned upside down in July 2017, when Chris Clarkson of the University of Queensland in Australia and his colleagues published the results of their excavation of a rock shelter in northern Australia called Madjedbebe. Artefacts from the shelter had previously been dated to 60,000 years ago, but those dates had proved controversial. Clarkson excavated further into Madjedbebe and found artefacts that he could reliably date to 65,000 years ago. As well as simply pushing back the date of Australia’s colonization, this called into question the idea that humans were responsible for the extinction of the megafauna – as it now appeared that the two had coexisted for many thousands of years. It also appears that Australia was colonized before the onset of the main migration from Africa 60,000 years ago. It is not clear how that apparent discrepancy will be resolved.

It would be tempting to dismiss Clarkson’s findings as a fluke, but a study published just one month later also seems to confound the classic out-of-Africa story. Researchers investigated a cave called Lida Ajer on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, which had previously yielded fossil human teeth. They were able to confirm that the teeth belonged to modern humans, and that they were between 63,000 and 73,000 years old. This is further evidence that modern humans reached Indonesia ahead of schedule – and Australia was then not far away.

There is one other peculiarity about the migration into Australia. The people who first entered the continent seem to have bred with an unknown hominin species. In a 2016 study, researchers analysed the genomes of living indigenous Australians, Papuans, people from the Andaman Islands near India, and from mainland India. They found sections of DNA that did not match any known hominin species.

The New World

The Americas were the last leg of humanity’s trek around the globe (if you don’t count Antarctica). Not so long ago there was a simple and seemingly incontrovertible answer to the question of how and when the first settlers made it to the Americas. This was that, some 13,000 years ago, a group of people from Asia walked across a land bridge that connected Siberia to Alaska and headed south. These people, known as the Clovis, were accomplished toolmakers and hunters. Subsisting largely on big game killed with their trademark fluted spear points, they prospered and spread out across the continent.

For decades this was the received wisdom. But nowadays the identity of the first Americans is an open question again. According to the Clovis First theory, it was around 13,500 years ago, near the end of the last ice age, that a brief window of opportunity opened up for humans to finally enter North America. With vast amounts of water locked up in ice caps, the sea level was lower than it is today and Siberia and Alaska were connected by a now-submerged land bridge called Beringia, now under the Bering Strait. As the world began to warm, the huge ice sheets that had blocked this way into North America began to retreat, parting to create an ice-free corridor all the way to the east of the Rockies. The Clovis walked right in.

The presence of distinctive stone tools throughout the US and northern Mexico supports the idea that the Clovis lived there 13,000 years ago, as does the timing of an extinction that wiped out more than 30 groups of large mammals including mammoths, camels and sabre-toothed cats. This coincides neatly with the arrival of Clovis hunters, and could have been their handiwork.

But over the years inconvenient bits of evidence have piled up. In 1997 a delegation of 12 eminent archaeologists visited Monte Verde, a site of human habitation in southern Chile that was first excavated in the 1970s. It was originally claimed to be 14,800 years old. That, of course, contradicted the Clovis First theory. The trip was a pivotal moment: most of the visiting archaeologists changed their minds, and prehistory started to be rewritten. Many other pre-Clovis sites have also been found, and in 2015 it emerged that Monte Verde might actually be more than 18,000 years old.

Recent DNA studies also contradict the old orthodoxy. By comparing the genomes of modern Asian and Native American people and estimating the amount of time it would take for the genetic differences to accumulate, geneticists estimate that people entered the Americas at least 16,000 years ago – 3,000 years earlier than in the Clovis model.

So if Clovis First is wrong, how and when were the Americas colonized? Despite the shift, some things stay the same. Most researchers still think that the first Americans migrated from Asia, a conclusion based largely on DNA research. For example, a 2012 study led by Harvard’s David Reich compared DNA from Native American populations scattered from the Bering Strait to Tierra del Fuego with DNA from native Siberians. The team concluded controversially that the first Americans were descended from Siberians who arrived in at least three waves (see Figure 6.3).

FIGURE 6.3 Alternative migration routes from the Old World to the New are now being considered to explain genetic and archaeological findings.

That might not sound too different from Clovis First. But other research tells another story. The DNA of Native Americans is sufficiently different from the Siberians’ DNA to suggest that the populations went their separate ways around 30,000 years ago. This could indicate a much earlier entry. Some archaeologists claim that they have found evidence of human habitation in the Americas as far back as 50,000 years ago, but these claims are contentious.

A more likely scenario is that the settlers did not come directly from Asia but from a population that settled in Beringia 30,000 years ago and stayed put for 15,000 years before pressing on to Alaska. This group would have become isolated from the ancestral population in north-eastern Asia, perhaps by ice, and built up 15,000 years’ worth of genetic differences. This scenario is dubbed the ‘Beringia standstill’.

Not everybody, however, clings to the idea that the first Americans arrived from Siberia. The 18,000-year-old Monte Verde site does not fit the story, particularly given that it is about 12,000 kilometres from the supposed entry point into the Americas. There are also animal bones marked by stone tools from Bluefish Caves in Yukon, Canada, which have been dated to 24,000 years ago.

A second alternative to Clovis First is coastal migration. Some researchers have suggested that, instead of walking across Beringia, the first Americans hopped on boats and sailed along the Pacific coast. However, it is extremely difficult to test this scenario. The melting of the glaciers approximately 10,000 years ago submerged the ancient coast, along with any archaeological evidence it holds.

Nonetheless, some evidence does exist. Reich’s DNA study suggests that the first wave of colonists moved south along the Pacific coast. And we know that ancient East Asians were accomplished seafarers, reaching the isolated Ryukyu Islands between Japan and Taiwan roughly 35,000 years ago. There are also archaeological finds that lend credence to the idea. University of Oregon archaeologist Jon Erlandson has worked on the Channel Islands, west of what is now Los Angeles, for decades and has uncovered evidence of an advanced 12,000-year-old culture there. The remains of 13,000-year-old Arlington Springs Man were also found on the Channel Islands.

Support for coastal migration also comes from Michael Waters, director of Texas A&M University’s Center for the Study of the First Americans. He has led the excavation of Friedkin, a pre-Clovis site in central Texas. Since digging began in 2006, over 15,000 artefacts have been uncovered – more than at all other pre-Clovis sites combined – dating from 15,500 to 13,200 years ago. The great majority are offcuts from toolmaking, but there are also choppers, scrapers, hand axes, blades and bladelets. In Waters’s opinion, these could be the precursors of Clovis technology. If the dating is right, then these people arrived before the ice sheets retreated and needed some other route south. This adds further credence to a coastal migration.

The Anzick Child

In 2014 geneticists studied the genes of an American boy, known as the Anzick Child, who died 12,600 years ago. He was the earliest ancient American to have their genome sequenced. Incredibly, he turned out to be a direct ancestor of many peoples across the Americas. The find offered the first genetic evidence for what Native Americans have claimed all along: that they are directly descended from the first Americans. It also confirmed that those first Americans can be traced back at least 24,000 years, to a group of early Asians and a group of Europeans who mated near Lake Baikal in Siberia.

We may never know who the Anzick Child was – why he died, at just three years old, in the foothills of the American Rockies; why he was buried, 12,600 years ago, beneath a huge cache of sharpened flints; or why his kin left him with a bone tool that had been passed down the generations for 150 years.

Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and his colleagues were able to extract enough viable DNA from the boy’s badly preserved bones to sequence his entire genome. They then compared this with DNA samples from 143 modern non-African populations, including 52 South American, Central American and Canadian tribes.

The comparison revealed a map of ancestry. The Anzick Child is most closely related to modern tribes in Central and South America, and is equally close to all of them – suggesting that his family were common ancestors. To the north, Canadian tribes were very close cousins. DNA comparisons with Siberians, Asians and Europeans show that the further west populations are from Alaska, the less related they are to the boy.

An even earlier entry?

The date of the first entry to the Americas is clearly still in doubt. A few scientists have even claimed evidence for much earlier peopling. In 2003, for instance, 40,000-year-old human footprints were found in volcanic ash near Puebla in Mexico. According to Silvia Gonzalez of Liverpool John Moores University in the UK, this suggested that the New World was colonized far earlier than anyone thought. But later work showed that the ash solidified 1.3 million years ago, long before our species even evolved. Everyone, including Gonzalez, now agrees that the footprints were not really footprints.

Similarly, in 2013 researchers claimed to have found 22,000-year-old stone tools at a site in Brazil. This would imply that humans lived in South America at the height of the last ice age – not as extreme a claim as Gonzalez’s, but still a long way from the consensus. But not everyone agrees that the purported tools are real.

The most startling claim of all was published in 2017. Finds at a site in California suggested that the New World might have first been reached at least 130,000 years ago – more than 100,000 years earlier than conventionally thought. If the evidence stacks up, the earliest people to reach the Americas may have been Neanderthals or Denisovans rather than modern humans.

The evidence came from a coastal site in San Diego County. In the early 1990s routine highway excavations exposed fossil bones belonging to a mastodon, an extinct relative of the elephant. Many of the bones and teeth were fragmented. Alongside these remains, the researchers found stone cobbles that had evidence of impact marks on their surfaces, suggesting that humans used stone tools to break the bones. But a dating study indicates that the remains are 131,000 years old.

There were no human fossils at the site. But both Neanderthals and Denisovans were probably present in Siberia more than 130,000 years ago. Since sea levels were low and a land bridge existed between Siberia and North America just before that time, either group could in theory have wandered across. Alternatively, it might have been modern humans – Homo sapiens – that made it to the New World 130,000 years ago.

For now, this is all speculation, because most anthropologists do not believe the results. The supposed stone hammers and anvils are a particular weak point because, once again, they might not really be tools.