7

Civilization and beyond

For most of our species’ existence, we lived as hunter-gatherers – often in small groups that we might nowadays label ‘tribes’. Then, around 10,000 years ago, something changed. We began living in densely populated villages, towns and eventually cities. We worked out how to read and write, make machinery, erect towering buildings and monuments, and we started fighting wars. In short, we invented civilization.

The real first farmers

In February 1910 British botanist Lilian Gibbs walked across North Borneo and climbed Mount Kinabalu, a lone white woman among 400 locals. She later wrote: ‘The “untrodden jungle” of fiction seems to be non-existent in this country. Everywhere the forest is well worked and has been so for generations.’

What Gibbs saw was a seemingly curated tropical forest, regularly set alight by local tribes and with space carefully cleared around selected wild fruit trees, to give them room to flourish. The forest appeared to be partitioned and managed to get the most rattan canes, fibre for basketry, medicinal plants and other products. Generation after generation of people had cared for the trees, gradually shaping the forest they lived in. This was not agriculture as we know it today but a more ancient form of cultivation, stretching back more than 10,000 years. Half a world away from the ‘Fertile Crescent’, the region of the Middle East once thought to be the site of the first settled agricultural communities, Gibbs was witnessing a living relic of the earliest human farming.

In recent years, archaeologists have found signs of this ‘proto-farming’ on nearly every continent, transforming our picture of the dawn of agriculture. Gone is the simple story of a sudden agricultural revolution in the Fertile Crescent that produced benefits so great that it rapidly spread around the world. It turns out that farming was invented many times, in many places, and was rarely an instant success. In short, there was no agricultural revolution.

Farming is seen as a pivotal invention in the history of humanity. Previously, our ancestors had roamed the landscape gathering edible fruits, seeds and plants and hunting whatever game they could find. They lived in small mobile groups that usually set up temporary homes according to the movement of their prey. Then one fine day in the Fertile Crescent, around 8,000 to 10,000 years ago – or so the story goes – someone noticed sprouts growing out of seeds they had accidentally left on the ground. Over time, people learned how to grow and care for plants to get the most out of them. Doing this for generations gradually transformed the wild plants into rich domestic varieties, most of which we still eat today.

This series of events is credited with irreversibly shaping the course of humanity. As fields began to appear on the landscape, more people could be fed. Human populations – already on the rise and stretching the resources available to hunter-gatherers – exploded. At the same time, our ancestors swapped their migratory habits for sedentary settlements: these were the first villages, with adjoining fields and pastures. A steadier food supply freed up time for new tasks. Craftspeople were born – the first specialized toolmakers, farmers and carers. Complex societies began to develop, as did trade networks between villages. The rest, as they say, is history.

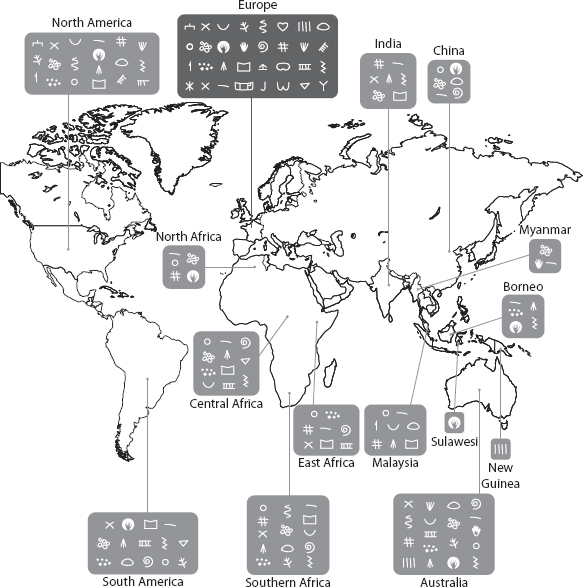

The enormous impact of farming is widely accepted, but in recent decades the story of how it all began has been completely turned on its head. We now know that, while the inhabitants of the Fertile Crescent were undoubtedly some of the earliest farmers, they were not the only ones. Archaeologists now agree that farming was independently ‘invented’ in at least 11 regions, from Central America all the way to China (see Figure 7.1). Decades of digging have exposed numerous instances of ancient proto-farming, similar to what Gibbs saw in Borneo.

FIGURE 7.1 Farming emerged several times around the world and not only in the Fertile Crescent.

Another point archaeologists are rethinking is the notion that our ancestors were forced into farming when their populations outgrew what the land could provide naturally. If humans had turned to crops out of hunger and desperation, you would expect their efforts to have intensified when the climate took a turn for the worse. In fact, archaeological sites in Asia and the Americas show that earliest cultivation happened during periods of relatively stable, warm climates when wild foods would have been plentiful.

Nor is there much evidence that early farming coincided with overpopulation. When crops first appeared in eastern North America, for example, people were living in small, scattered settlements. The earliest South American farmers also lived in the very best habitats, where resource shortages would have been least likely. Similarly, in China and the Middle East, domesticated crops appear well before dense human populations would have made foraging impractical.

Instead, the first farmers may have been pulled into experimenting with cultivation, presumably out of curiosity rather than necessity. That lack of pressure would explain why so many societies kept crops as a low-intensity sideline – a hobby, almost – for so many generations. Only much later in the process would densely populated settlements have forced people to abandon wild foods in favour of a near-exclusive reliance on farming.

Those first experiments probably happened when bands of hunter-gatherers started changing the landscape to encourage the most productive habitats. On the islands of South East Asia, people were burning patches of tropical forest as far back as the last ice age. This created clearings where plants with edible tubers could flourish. In Borneo, evidence of this stretches back 53,000 years; in New Guinea it is 20,000 years. We know that the burns were deliberate because the charcoal they left behind peaked during wet periods, when natural fires would be less common and people would be fighting forest encroachment.

Burning forest would have paid off for hunters, too, as game is easier to spot at forest edges. At Niah Cave on the northern coast of Borneo, researchers have found hundreds of orang-utan bones among the remains of early hunters, suggesting that forest regrowth after a burn brought the apes low enough to catch, even before the invention of blowpipes. Burning probably intensified as the last ice age gave way to the warmer, wetter Holocene beginning about 13,000 years ago. Rainfall in Borneo doubled, producing a denser forest that would have been much harder to forage without fire.

This wasn’t happening only in South East Asia. Changing climates also pushed hunter-gatherers into landscape management in Central and South America. At the end of the last ice age, the perfect open hunting grounds of the savannahs began to give way to closed forest. By 13,000 years ago people were burning forests during the dry season when fires would carry. Researchers are now turning up evidence of similar management activities in Africa, Brazil and North America.

From burning, it is just a short step to actively nurturing favoured wild species, something that also happened soon after the end of the last ice age in some places. Weeds that thrive in cultivated fields appear in the Fertile Crescent at least 13,000 years ago, for example, and New Guinea highlanders were building mounds on swampy ground to grow bananas, yams and taro about 7,000 years ago. In parts of South America, traces of cultivated crops such as gourds, squash, arrowroot and avocado appear as early as 11,000 years ago.

Evidence suggests that these people lived in small groups, often sheltering under rock overhangs or in shallow caves, and that they tended small plots along the banks of seasonal streams in addition to foraging for wild plants. Their early efforts would not have looked much like farming today. They were more like gardens: small, intensively managed plots on riverbanks and alluvial fans that probably did not provide many calories. Instead, they may have provided high-value foods, such as rice, for special occasions.

Archaeologists have long assumed that this proto-farming was a short-lived predecessor to fully domesticated crops. They believed that the first farmers quickly transformed the plants’ genetic make-up by selecting traits like larger seeds and easier harvesting to produce modern domestic varieties. After all, similar selection has produced great changes in dogs within just the past few hundred years.

But new archaeological sites and better techniques for recognizing ancient plant remains have made it clear that crop domestication was often very slow. Through much of the Middle East, Asia and New Guinea, at least a thousand – and often several thousand – years of proto-farming preceded the first genetic hints of domestication.

And in China people began cultivating wild forms of rice on a small scale about 10,000 years ago. But physical traits associated with domesticated rice, such as larger grains that stay in the seed head instead of falling off to seed the next generation, did not appear until about two-and-a-half millennia later. Fully domesticated rice did not appear until 6,000 years ago.

Even after crops were domesticated, there was often a lag, sometimes of thousands of years, before people began to rely on them for most of their calories. During this prolonged transition period people often acted as though they had not decided how much to trust the new-fangled agricultural technology.

The record also shows a long period of overlap in other regions, with cultures using both wild foods and domesticated crops. We know from the type of starch grains found on their teeth that people living in southern Mexico 8,700 years ago were eating domesticated maize, yet large-scale slash-and-burn agriculture did not begin until nearly a millennium later. In several cases – Scandinavia, for example – societies began to rely on domesticated crops and then switched back to wild foods when they could not make a success of farming. And in eastern North America, Native Americans had domesticated squash, sunflowers and several other plants by about 3,800 years ago, but only truly committed to agriculture about 1,100 years ago.

The story of agriculture, in short, is not the sudden agricultural revolution of textbooks but, rather, an agricultural evolution. It was a long, drawn-out process.

How we lived as hunter-gatherers: an interview with Jared Diamond

Jared Diamond is Professor of Geography at the University of California, Los Angeles. Here he discusses his research into today’s tribal communities to see how we all once lived, for his 2012 book The World Until Yesterday.

What distinguishes tribal communities’ way of child-rearing?

Outside observers are universally struck by the precocious social skills of children in tribal societies. In most traditional cultures, kids have the right to make their own decisions. Sometimes this horrifies us because a two-year-old can decide to play next to a fire and burn itself. But the attitude is that children have got to learn from their own experience.

What are the roles of family and community in these traditional societies?

Children sleep with their parents so they have absolute security, and are nursed whenever they want. They live in multi-age playgroups, so, by the time they are teenagers, they have spent ten years bringing up little siblings.

Are there any negative aspects?

There are many things that these societies do that are wonderful, and there are some things that they do that, to us, seem terrible – like occasionally killing their old people or infants, or persistently making war.

In what context would elderly people be killed?

In most traditional societies that live in permanent villages, old people have happier and more satisfying lives than those in Western society. They spend their lives with their relatives, children and lifelong friends. And in a society without writing, old people are valued for their insight and knowledge. But in a nomadic society, the cool reality is that, if you have to move and you are already carrying your baby and your stuff, you can’t carry the old person. There’s no alternative.

What happens to old people in nomadic tribes?

There’s a sequence of choices that all end up with them being abandoned or killed. The gentlest thing to do is to abandon them, leaving food and water in case they regain strength and can catch up. In some societies, old people take it upon themselves to ask to be killed. In other societies, they are killed actively. Among the Aché people of Paraguay, for example, there are young men whose job it is to kill the older people.

The first civilizations

Many archaeologists also suspect that farming was not, as long believed, the first step on the road to civilization.

Steven Mithen at the University of Reading, UK, spent years digging for Stone Age ruins in south Jordan. He found the remains of a primitive village. As the team dug through what they thought was a rubbish dump, a student came upon a polished, solid floor – hardly the kind of craftsmanship to waste on a communal tip. Then came a series of platforms engraved with wavy symbols. It was clearly not the local dump.

Mithen now compares the structure to a small amphitheatre. With benches lining one side of a roughly circular building, it looks purpose built for celebrations or spectacles – perhaps feasting, music, rituals or something more macabre. A series of gullies runs down through the floor, through which sacrificial blood might once have flowed in front of a frenzied crowd. Whatever happened at the place now known as Wadi Faynan, the site could transform our understanding of the past. At 11,600 years old, it predates farming – which means that people were building amphitheatres before they invented agriculture.

It was not supposed to be that way. Archaeologists have long been familiar with the idea of a ‘Neolithic Revolution’ during which humans abandoned the nomadic lifestyle that had served them so well for millennia and settled in permanent agrarian communities. They domesticated plants and animals and invented a new way of life.

By about 8,300 years ago people in the Levant – modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories and parts of southern Anatolia in Turkey – had the full range of Neolithic technologies: settled villages with communal buildings, pottery, domesticated animals, cereals and legumes. Art, politics and astronomy also have their roots in this time. And yet here was a settlement more than 3,000 years older displaying many of those innovations, but lacking the technology that is supposed to have got the whole thing started: farming. The people who built Wadi Faynan were not nomads but neither were they farmers. They probably relied almost exclusively on hunting and gathering.

Instead of agriculture, then, some very different motivations seem to have drawn these people together – things like religion, culture and feasting. Never mind the practical benefits of a steady food supply; the seeds of civilization may have been sown by something much more cerebral.

For much of the twentieth century our view of the Neolithic was seen through the lens of more recent social upheaval: the Industrial Revolution. The idea originated, in part, with Marxist archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe. Seeing the urban societies that had coalesced around factory towers and ‘dark satanic mills’, Childe suspected that the first farms could have been similar hotbeds of rapid social and cultural change.

He proposed that it began in the Levant around 10,000 years ago. As the Ice Age ended, the region became more arid, save for smaller patches of lush land by rivers. With these limited areas to forage, nomadic hunter-gatherers discovered that it was more efficient to cultivate barley and wheat in one place. A baby boom followed. As Childe put it in his 1936 book Man Makes Himself: ‘If there are more mouths to feed, there will also be more hands to till the fields…quite young toddlers can help in weeding fields and scaring off birds.’ And as the farmers’ crops and families blossomed, so, too, did their crafts, including carpentry and pottery, along with greater social complexity. The growing communities would have also been fertile ground for more organized forms of religion to flourish.

At least, that was the theory. Man Makes Himself became a touchstone for many archaeologists – even as cracks began to appear in some of its assumptions. Studies of the climate, for instance, suggest that the changes following the Ice Age were not nearly as radical as Childe believed. Without the environmental spark, there were doubts that agriculture offered any real benefits. Particularly when you have only a few bellies to fill, plundering nature’s larder is just as efficient as the backbreaking business of planting, weeding and harvesting. So why would you change?

By the 1990s those cracks had turned to gaping chasms, following digs in Anatolia. The region was already attracting attention for a site known as Nevali Çori, which was around 10,000 years old. Although it seemed to be a simple settlement of proto-farmers, the archaeologists also uncovered signs of more advanced culture, embodied in a series of communal ‘cult buildings’ full of macabre artwork.

The buildings were remarkably large and complex for something so old. And what they contained was even more revealing. In one sculpture, a snake writhes across a man’s head; another depicts a bird of prey landing on the heads of entwined twins. The most eye-catching feature was a collection of strange, anthropomorphic T-shaped megaliths with faceless, oblong heads and human arms engraved on their sides. As people sat on benches around the walls of the buildings, these monuments must have loomed over them like sentinels.

Sadly, the site was submerged when the Atatürk Dam was built across the Euphrates. But one of the archaeologists, Klaus Schmidt, set about scouring the surrounding countryside for further clues to the origins of this lost society. During this tour he found himself on a mound called Göbekli Tepe. The grassy knoll was already popular with locals visiting its magic ‘wishing tree’, but what really caught Schmidt’s eye was a large piece of limestone that closely resembled those T-shaped megaliths from Nevali Çori (see Figure 7.2).

FIGURE 7.2 Two of the T-shaped monuments of Göbekli Tepe. What were they for?

It did not take him long to realize that he had stumbled on something even more extraordinary. Buried beneath the hill, he found three layers of remains. The oldest and most impressive was more than 11,000 years old, with a labyrinth of circular ‘sanctuaries’ measuring up to 30 metres in diameter. Around the inner walls were magnificent, T-shaped monuments encircling two larger pillars, like worshippers surrounding their idol. Some were engraved with belts and robes and, given their monumental size – around three times the height of a modern man – and abstract appearance, Schmidt interprets them as representing some kind of god-like figure.

If Nevali Çori was a humble parish church, then this was a cathedral. Strangely, each sanctuary seems to have been dismantled and deliberately filled in some time later – perhaps as part of a ritual. Amid the jumble of debris, Schmidt’s team have found many bones, including human remains. His team has also found a lot of rooks and crows – birds known to be drawn to corpses. For this reason, Schmidt’s team believe that some of the buildings’ functions may have centred on death.

We can never know what happened there, but Schmidt has some suspicions. From the outset, he was fascinated by strange door-like ‘porthole stones’, found within the sanctuaries and often decorated with grisly images of predators and prey. Since the holes in the middle are often the size of a human body, Schmidt imagines that visitors may have crawled through to symbolize the passage into the afterlife.

It is clear that Göbekli Tepe was the creation of a sophisticated society, capable of marshalling the labour of perhaps hundreds of people. That degree of social complexity was not expected in emerging early Neolithic cultures. Along with the complex artwork and intricate ideology, this kind of development was supposed to come long after agriculture. Yet Schmidt failed to find any signs of farming. Domesticated corn can be distinguished from its wild ancestor by its plumper ears, but there was no trace of it. Stranger still, there is no sure evidence of any kind of permanent settlement at Göbekli Tepe. It was too far away from water supplies and Schmidt found little evidence of the hearths, fire pits or tools you might expect in a dwelling.

Schmidt’s conclusions were radical. He proposed that Göbekli Tepe was a dedicated site of pilgrimage, perhaps the culmination of a long tradition of gatherings and celebrations. Importantly, it was ideology rather than farming that was pulling these people together to form a larger society. Indeed, it may have been the need to feed people at these kinds of gatherings that eventually led to agriculture – which turns the original idea of the Neolithic revolution on its head. Tellingly, recent genetic work pinpoints the origin of domestic wheat to a spot very close to Göbekli Tepe.

Schmidt’s finds astonished archaeologists and captivated the wider world. The ‘first temple’ soon began attracting a new swarm of pilgrims, with filmmakers, archaeologists and tourists flocking to visit.

Other researchers are dubious. The original people’s habit of periodically burying their sanctuaries means that there is always the possibility that old remains rather than contemporary debris were dug up to dump on the monuments. That would shave hundreds or thousands of years off the age of the temple, making it much less revolutionary. Others doubt Schmidt’s claims that Göbekli Tepe was the site of pilgrimage rather than a permanent settlement.

Such concerns do not necessarily derail Schmidt’s broader theory that culture, rather than farming, propelled our march to civilization. But it was clear that, to expand the theory, archaeologists needed to look further afield. Fortunately, they were on the trail almost as soon as Göbekli Tepe was discovered. A little down the Euphrates, across the border into Syria, French researchers have found a trio of early Neolithic villages called Dja’De, Tell’Abr and Jerf el-Ahmar. Although they are clearly permanent settlements rather than sites of pilgrimage, they all house large, highly decorated communal buildings that seem to have been the product of the same complex, ritualistic culture as Göbekli Tepe (see Figure 7.3).

FIGURE 7.3 Recent findings in the Levant suggest that people were living in large settlements and building temples before they invented agriculture.

With Syria’s civil war raging, these settlements are now off limits, but charred remains of seeds caught in cooking pots and house fires at Jerf el-Ahmar revealed that the first inhabitants were still gathering a wide variety of wild cereals and lentils. Later on, however, in the upper layers, a few species begin to dominate – ones that would later be domesticated. There is also evidence of imported crops that would not naturally grow in the region. So the people of Jerf el-Ahmar were probably cultivating plants by the latter stages of its occupation. The main point, though, is that they had begun to build their complex society long before they had domestic crops.

The ‘amphitheatre’ at Wadi Faynan, Jordan, which Mithen first excavated in 2010, tells a similar story much further south. With a floor area of nearly 400 square metres – about the same as two tennis courts – it is one of the largest ancient structures to have been found after Göbekli Tepe. It was also surrounded by a ‘honeycomb’ of other rooms, which Mithen suspects may have been workshops. Importantly, the remains are neatly layered, allowing archaeologists to pin a firm date on the site – 11,600 years ago, right at the dawn of the Neolithic. Again, it seems that the first inhabitants were hunter-gatherers.

The first writing

One of the particular accomplishments of human civilization is the invention of written language. It has enabled us to accumulate knowledge and wisdom, and pass them on to later generations, in far greater quantities than was ever possible before. But the origins of the written word may be far more ancient than we ever suspected.

Genevieve von Petzinger, a palaeoanthropologist from the University of Victoria in Canada, is leading an unusual study of cave art. Her interest lies not in the breathtaking paintings of bulls, horses and bison that usually spring to mind, but in the smaller, geometric symbols frequently found alongside them. Her work has convinced her that, far from being random doodles, the simple shapes represent a fundamental shift in our ancestors’ mental skills.

The first formal writing system that we know of is the 5,000-year-old cuneiform script of the ancient city of Uruk in what is now Iraq. But it and other systems like it – such as Egyptian hieroglyphs – are complex and did not emerge from a vacuum. There must have been an earlier time when people first started playing with simple abstract signs. For years, von Petzinger has wondered whether the circles, triangles and squiggles that humans began leaving on cave walls 40,000 years ago represent that special time in our history – the creation of the first human code.

If so, the marks are highly significant. Our ability to represent a concept with an abstract sign is something no other animal, not even our closest cousins the chimpanzees, can do. It is arguably also the foundation for our advanced, global culture.

Between 2013 and 2014 von Petzinger visited 52 caves in France, Spain, Italy and Portugal. The symbols she found ranged from dots, lines, triangles, squares and zigzags to more complex forms like ladder shapes, hand stencils, something called a tectiform that looks a bit like a post with a roof, and feather shapes called penniforms. In some places, the signs were part of bigger paintings. Elsewhere, they were on their own, like the row of bell shapes found in El Castillo in northern Spain or the panel of 15 penniforms in Santian, also in Spain.

Thanks to von Petzinger’s meticulous logging, it is now possible to see trends – new signs appearing in one region and remaining common for a while before falling out of fashion. The research also reveals that modern humans were using two-thirds of these signs when they first settled in Europe, which creates another intriguing possibility. ‘This does not look like the start-up phase of a brand-new invention’, von Petzinger wrote in her book The First Signs (2016). In other words, when modern humans first started moving into Europe from Africa, they must have brought a mental dictionary of symbols with them.

That fits well with the discovery of a 70,000-year-old block of ochre etched with cross-hatching in Blombos Cave in South Africa. And when von Petzinger looked through archaeology papers for mentions or illustrations of symbols in cave art outside Europe, she found that many of her 32 signs were used around the world (see Figure 7.4). There is even tantalizing evidence that an earlier human, Homo erectus, deliberately etched a zigzag on a shell on Java some 500,000 years ago.

FIGURE 7.4 Symbols found on relics from Stone Age Europe are also found in caves across the rest of the world. Their similarities suggest that they were more than just random squiggles.

Nonetheless, something quite special seems to have happened in Ice Age Europe. In various caves, von Petzinger frequently found certain symbols used together. For instance, starting 40,000 years ago, hand stencils are often found alongside dots. Later, between 28,000 and 22,000 years ago, they are joined by thumb stencils and finger fluting – parallel lines created by dragging fingers through soft cave deposits.

These kinds of combinations are particularly interesting if you are looking for the deep origins of writing systems. Nowadays, we effortlessly combine letters to make words and words to make sentences, but this is a sophisticated skill. Von Petzinger wonders whether the people of the Upper Palaeolithic, which began 40,000 years ago, started experimenting with more complex ways of encoding information using deliberate, repeated sequences of symbols. Unfortunately, it is hard to say from signs painted on cave walls, where arrangements could be deliberate or completely random.

Whether or not the symbols are actually writing depends on what you mean by ‘writing’. Strictly speaking, a full system must encode all of human speech, ruling the Stone Age signs out. But if you take it to mean a system to encode and transmit information, then it is possible to see the symbols as early steps in the development of writing.

Von Petzinger has another reason to believe that the symbols are special: they are easy to draw. In a sense, the humble nature of such shapes makes them more universally accessible – an important feature for an effective communication system. More than anything, she believes that the invention of the first code represents a complete shift in how our ancestors shared information. For the first time, they no longer had to be in the same place at the same time to communicate with one another, and information could survive its owners.

Did palaeo-porn exist? An interview with April Nowell

April Nowell is a Palaeolithic archaeologist. In 2014 she published a paper, co-authored with Melanie Chang, exploring whether certain prehistoric figurines might have been pornographic.

Which Palaeolithic images and artefacts have been described as pornography?

The Venus figurines of women, some with exaggerated anatomical features, and ancient rock art, like the image from the Abri Castanet site in France that is supposedly of female genitalia.

You take issue with this interpretation. Who is responsible for spreading it, journalists or scientists?

People are fascinated by prehistory, and the media want to write stories that attract readers – and, to use a cliché, sex sells. But when a New York Times headline reads ‘A Precursor to Playboy: Graphic Images in Rock’ and Discover magazine asserts that man’s obsession with pornography dates back to ‘Cro-Magnon days’ based on ‘the famous 26,000-year-old Venus of Willendorf statuette…[with] GG-cup breasts and a hippopotamal butt’, I think a line is crossed. To be fair, archaeologists are partially responsible – we need to choose our words carefully.

Aren’t other interpretations of palaeo-art just as speculative as calling them pornographic?

Yes, but when we interpret Palaeolithic art more broadly, we talk about ‘hunting magic’ or ‘religion’ or ‘fertility magic’. I don’t think these interpretations have the same social ramifications as pornography. When respected journals – Nature, for example – use terms such as ‘prehistoric pin-up’ and ‘35,000-year-old sex object’, and a German museum proclaims that a figurine is either an ‘earth mother or pin-up girl’ (as if no other roles for women could have existed in prehistory), they carry weight and authority. This allows journalists and researchers, evolutionary psychologists in particular, to legitimize and naturalize contemporary Western values and behaviours by tracing them back to the ‘mist of prehistory’.

Shaped by war

War has bedevilled human societies throughout recorded history. The accounts of the earliest civilizations, such as the Sumerians and Mycenaean Greeks, are replete with battles – and archaeologists have uncovered evidence of battles and massacres going back even further. All of this raises the question: why do we go to war? The cost to human society is enormous and yet, for all our intellectual development, we continue to wage war well into the twenty-first century.

Since the early 2000s a new theory has emerged that challenges the prevailing view that warfare is a product of human culture and thus a relatively recent phenomenon. For the first time, anthropologists, archaeologists, primatologists, psychologists and political scientists have approached a consensus. Not only is war as ancient as humankind, they say, but it has also played an integral role in our evolution. The theory helps explain the evolution of familiar aspects of warlike behaviour such as gang warfare. It even suggests that the cooperative skills we have had to develop to be effective warriors have turned into the modern ability to work for a common goal.

Mark Van Vugt, an evolutionary psychologist at the Free University Amsterdam in the Netherlands, thinks warfare was already there in the common ancestor we share with chimps, and that it has affected our evolution. Studies suggest that warfare accounts for 10 per cent or more of all male deaths in present-day hunter-gatherers.

Primatologists have known for some time that organized, lethal violence is common between groups of chimpanzees, our closest relatives. Whether between chimps or hunter-gatherers, however, intergroup violence is nothing like modern pitched battles. Instead, it tends to take the form of brief raids using overwhelming force, so that the aggressors run little risk of injury. This opportunistic violence helps the aggressors weaken rival groups and thus expand their territorial holdings.

Such raids are thought to be possible because humans and chimps, unlike most social mammals, often wander away from the main group to forage singly or in smaller groups. Bonobos – which are as closely related to humans as chimps are – have little or no intergroup violence, perhaps because they tend to live in habitats where food is easier to come by, so they need not stray from the group.

If group violence has been around for a long time in human society, then we ought to have evolved psychological adaptations to a warlike lifestyle. In line with that, there is evidence that males – whose larger and more muscular bodies make them better suited for fighting – have evolved a tendency towards aggression outside the group, but cooperation within it.

Aggression in women, by contrast, tends to take the form of verbal rather than physical violence, and is mostly one-to-one. Gang instincts may have evolved in women, too, but to a much lesser extent. This may be partly because of our evolutionary history, in which men are often stronger and better suited for physical violence. This could explain why female gangs tend to form only in same-sex environments such as prisons or high schools. But women also have more to lose from aggression, since they bear most of the effort of child-rearing.

Not surprisingly, a study has shown that men are more aggressive than women when playing the leader of a fictitious country in a role-playing game. But there were also more subtle responses in group bonding. For example, male undergraduates were more willing than females to contribute money towards a group effort – but only when competing against rival universities. If told instead that the experiment was to test their individual responses to group cooperation, men coughed up less cash than women did. In other words, men’s cooperative behaviour emerged only in the context of intergroup competition.

Some of this behaviour could arguably be attributed to conscious mental strategies, but anthropologist Mark Flinn of the University of Missouri at Columbia has found that group-oriented responses occur on the hormonal level, too. He found that cricket players on the Caribbean island of Dominica experience a testosterone surge after winning against another village. But this hormonal surge, and presumably the dominant behaviour it prompts, was absent when the men beat a team from their own village. Similarly, the testosterone surge a man often has in the presence of a potential mate is muted if the woman is in a relationship with his friend. Again, the effect is to reduce competition within the group.

The net effect of all this is that groups of males take on their own special dynamic. Think of soldiers in a platoon or football fans out on the town: cohesive, confident and aggressive – just the traits a group of warriors needs. Chimpanzees don’t go to war in the way we do because they lack the abstract thought required to see themselves as part of a collective that expands beyond their immediate associates.

However, it may be that the real story of our evolutionary past is not simply that warfare drove the evolution of social behaviour. According to Samuel Bowles, an economist at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico and the University of Siena, Italy, the real driver was ‘some interplay between warfare and the alternative benefits of peace’. Although women seem to help broker harmony within groups, men may be better at peacekeeping between groups.

Our warlike past may have given us other gifts as well. In particular, warfare requires a colossal level of cooperation. And that seems to be a heritage worth hanging on to.

The most peaceful time: an interview with Steven Pinker

Steven Pinker is Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. His 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature argued that humans are less violent now than at any point in history.

Where did you find evidence for how violence has changed over time?

For prehistoric times, the main evidence is from forensic archaeology: the proportion of skeletons that had bashed-in skulls or arrowheads embedded in bones, together with archaeological evidence such as fortifications. For homicide over the last millennia or so, there are records in many parts of Europe that go back to the Middle Ages. And we know from documents of the era that crucifixions and all manner of gory executions took place in the ancient world.

For data about wars, there are many databases that estimate war deaths, and in recent eras governments and social scientists have tracked just about every aspect of life, so we really can get a clear view of things like child abuse, spousal abuse, rape and so on.

How do you explain the decline in violence?

I don’t think there is a single answer. One cause is government, that is, third-party dispute resolution: courts and police with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Everywhere you look for comparisons of life under anarchy and life under government, life under government is less violent. The evidence includes transitions such as the European homicide decline since the Middle Ages, which coincided with the expansion and consolidation of kingdoms and the transition from tribal anarchy to the first states. Watching the movie in reverse, in today’s failed states violence goes through the roof.

Do you think commerce helps, too?

Commerce, trade and exchange make other people more valuable alive than dead, and mean that people try to anticipate what the other guy needs and wants. It engages the mechanisms of reciprocal altruism, as the evolutionary biologists call it, as opposed to raw dominance.

What else has contributed to the decline?

The expansion of literacy, journalism, history, science – all of the ways in which we see the world from the other guy’s point of view. Feminization is another reason for the decline. As women are empowered, violence can come down, for a number of reasons. By all measures men are the more violent gender.

The evolution of religion

The rise of human civilization has been accompanied by another peculiar phenomenon: religious belief, and all the ceremonies, monuments and moral certainties that go with it. How did religion – which, on the face of it, is irrational and costly – survive and even thrive? Let’s start with a thought experiment.

By the time he was five years old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart could play the clavier and had begun to compose his own music. Mozart was a ‘born musician’; he had strong natural talents and required only minimal exposure to music to become fluent. Few of us are quite so lucky. Music usually has to be drummed into us by teaching, repetition and practice. And yet in other domains, such as language or walking, virtually everyone is a natural; we are all ‘born speakers’ and ‘born walkers’.

So what about religion? Is it more like music or language? Evidence from developmental psychology and cognitive anthropology indicates that religion comes to us nearly as naturally as language: we just need minimal exposure and our natural predilections do the rest. The vast majority of humans are ‘born believers’, naturally inclined to find religious claims and explanations attractive and easily acquired, and to attain fluency in using them. This attraction to religion is an evolutionary by-product of our ordinary cognitive equipment and human sociality.

For example, children learn early the difference between objects and ‘agents’ that act on those objects. They learn that agents, even if they cannot be seen, make things happen and that agents often act for a purpose. Experiments with children support the idea that they expect apparent order and design in the world to be brought about by an agent. This makes children naturally receptive to the idea that there may be one or more gods, which helps to account for the world around them.

It is important to note that this concept of religion deviates from theological beliefs. Children are born believers, not of Christianity, Islam or any other theology, but of what we might call ‘natural religion’. They have strong natural tendencies towards religion, but these tendencies do not inevitably propel them towards any one religious belief. Instead, the way the human mind solves problems generates a god-shaped conceptual space, waiting to be filled by the details of the culture into which we are born.

Religion could even help explain a deep puzzle of civilization: how did human societies scale up from small, mobile groups of hunter-gatherers to large, sedentary societies? The puzzle is one of cooperation. Up until about 12,000 years ago all humans lived in relatively small bands. Today, virtually everyone lives in vast, cooperative groups of mostly unrelated strangers. How did this happen?

In evolutionary biology, cooperation is usually explained by one of two forms of altruism: cooperation among kin and reciprocal altruism – you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours. But cooperation among strangers is not easily explained by either of these. As group size increases, both forms of altruism break down. With ever-greater chances of encountering strangers, opportunities for cooperation among kin decline. Reciprocal altruism – without extra safeguards such as institutions for punishing freeloaders – also rapidly stops paying off.

This is where religion comes in. Some early cultural variants of religion presumably promoted pro-social behaviours such as cooperation, trust and self-sacrifice, while encouraging displays of religious devotion, such as fasts, food taboos, extravagant rituals and other ‘hard-to-fake’ behaviours that reliably transmitted believers’ sincere faith and signalled their intention to cooperate. Religion thus forged anonymous strangers into moral communities tied together with sacred bonds under a common supernatural jurisdiction.

In turn, such groups would have been larger and more cooperative, and hence more successful in competition for resources and habitats. As these ever-expanding groups grew, they took their religions with them, further increasing social solidarity in a runaway process that softened the limitations on group size imposed by kinship and reciprocity.

From there, it is a short step to the morally concerned ‘Big Gods’ of the major world religions. People steeped in the Abrahamic faiths are so accustomed to seeing a link between religion and morality that it is hard for them to imagine that religion did not start that way. Yet the gods of the smallest hunter-gatherer groups, such as the Hadza of East Africa and the San of the Kalahari, are unconcerned with human morality. In these transparent societies, where face-to-face interaction is the norm, it is hard to escape the social spotlight. Kin altruism and reciprocity are sufficient to maintain social bonds.

However, as groups expand in size, anonymity invades relationships and cooperation breaks down. Studies show that feelings of anonymity – even illusory ones, such as wearing dark glasses – are the friends of selfishness and cheating. Social surveillance, such as being in front of a camera or an audience, has the opposite effect. Even subtle exposure to drawings resembling eyes encourages good behaviour towards strangers. As the saying goes, ‘Watched people are nice people.’

It follows, then, that people play nice when they think a god is watching them, and those around them. The anthropological record supports this idea. In moving from the smallest-scale human societies to the largest and most complex, Big Gods – powerful, omniscient, interventionist watchers – become increasingly common, and morality and religion become increasingly intertwined.

As societies get larger and more complex, rituals become routine and are used to transmit and reinforce doctrines. Similarly, notions of supernatural punishment, karma, damnation and salvation, and heaven and hell are common in modern religions, but relatively infrequent in hunter-gatherer cultures.

Religion, with its belief in watchful gods and extravagant rituals and practices, has been a social glue for most of human history. But recently some societies have succeeded in sustaining cooperation with secular institutions such as courts, police and mechanisms for enforcing contracts. In some parts of the world, especially Scandinavia, these institutions have precipitated religion’s decline by usurping its community-building functions. These societies with atheist majorities – some of the most cooperative, peaceful and prosperous in the world – have climbed religion’s ladder and then kicked it away.

Nine more things that made us human

1 Weapons

Projectile weapons travel faster than even the speediest antelope. A study published in 2013 suggests that H. erectus made use of them, since it was the earliest of our ancestors with a shoulder suitable for powerful and accurate throwing. What’s more, unusual collections of fist-sized rocks at the H. erectus site at Dmanisi, Georgia, give us an idea of their projectile weapon of choice.

But throwing rocks did more than offer a new hunting strategy: it also gave early humans an effective way to kill an adversary. Christopher Boehm at the University of Southern California says that projectile weapons levelled the playing field in early human societies, by allowing even the weakest group member to take down a dominant figure without having to resort to hand-to-hand combat. Weapons, he argues, encouraged early human groups to embrace an egalitarian existence unique among primates – one that is still seen in hunter-gatherer societies today.

2 Jewellery and cosmetics

At the Blombos Cave in South Africa, excavations in the early 2000s revealed collections of shells that had been perforated and stained, then strung together to form necklaces or bracelets. Similar finds have now turned up at other sites in Africa. More recently, work at Blombos has uncovered evidence that ochre was deliberately collected, combined with other ingredients and fashioned into body paint or cosmetics.

At first glance, these inventions seem trivial, but they hint at dramatic revolutions in the nature of human beliefs and communication. Jewellery and cosmetics were probably prestigious, suggesting the existence of people of higher and lower status. More importantly, they are indications of symbolic thought and behaviour, because wearing a particular necklace or form of body paint has meaning beyond the apparent. As well as status, it can signify things like group identity or a shared outlook. That generation after generation adorned themselves in this way indicates that these people had language complex enough to establish traditions.

3 Sewing

What people invented to wear with their jewellery and cosmetics was equally revolutionary. Needle-like objects appear in the archaeological record about 60,000 years ago, providing the first evidence of tailoring, but humans had probably already been wearing simple clothes for thousands of years.

Evidence for this comes from a rather unusual source. Body lice, which live mostly in clothes, evolved from hair lice some time after humans began clothing themselves, and a 2003 study of louse genetics suggests that body lice arose some 70,000 years ago. A 2011 analysis puts their origin as early as 170,000 years ago. Either way, it looks as if we were wearing sewn clothes when we migrated from our African cradle some 60,000 years ago and began spreading across the world.

Clothes may have allowed humans to inhabit cold areas that their naked predecessors could not tolerate. Sewing could have been a crucial development, since fitted garments are more effective at retaining body heat than loose animal furs. Even then, the frozen north would have been a challenge for a species that evolved on the African savannah, and recent research indicates that we also took advantage of changes in the climate to move across the world.

4 Containers

When some of our ancestors left Africa, they probably travelled with more than just the clothes on their backs. About 100,000 years ago, people in southern Africa began using ostrich eggs as water bottles. Having containers to transport and store vital resources would have given them huge advantages over other primates. But engravings on these shells are also highly significant: they appear to be a sign that dispersed groups had begun to connect and trade.

Since 1999 Pierre-Jean Texier at the University of Bordeaux in France has been uncovering engraved ostrich egg fragments at the Diepkloof rock shelter, 150 kilometres north of Cape Town in South Africa. The same five basic motifs are used time and again, over thousands of years, implying that they had a meaning that numerous generations could read and understand. Texier and his colleagues think they show that people were visually marking and defining their belongings, maintaining their group identity as they began travelling further and interacting with other groups.

5 Law

As our ancestors began trading, they would have needed to cooperate fairly and peacefully – with not just group members but also strangers from foreign lands. Trade may have provided the impetus to invent law and justice to make everyone follow the same rules.

Hints of how law evolved come from modern human groups, which, like Stone Age hunter-gatherers, live in egalitarian, decentralized societies. The Turkana are nomadic pastoralists in East Africa. Despite having no centralized political power, the men will cooperate with non-family members in a life-threatening venture – stealing livestock from neighbouring peoples, say. While the activity itself may be ethically dubious, the motivation to cooperate reflects ideas that underpin any modern justice system. If men refuse to join these raiding parties, they are judged harshly and punished by other group members. The Turkana display mechanisms of adjudication and punishment akin to a formal judiciary, suggesting that law and justice predate the emergence of centralized societies.

6 Timekeeping

As trade flourished over the millennia that followed, it was not just material goods that were exchanged. Trade in ideas encouraged new ways of thinking, and perhaps the early stirrings of scientific thought. Communities of hunter-gatherers living in what is now Scotland may have been among the first to scientifically observe and measure their environment. Aberdeenshire has many Mesolithic sites dating from about 10,000 years ago, including an odd monument consisting of a dozen pits arranged in a shallow arc roughly from north-east to south-west. When Vincent Gaffney at the University of Bradford and his colleagues noticed that the arc faced a sharp valley on the horizon through which the sun rises on the winter solstice, they realized that it was a cosmological statement. The 12 pits were almost certainly used to keep track of lunar months. The Aberdeenshire lunar ‘calendar’ – or ‘time reckoner’, as they dubbed it – is comfortably twice the age of any previously found.

By establishing a formal concept of time, you know when to expect seasonal events, such as the return of salmon to the local rivers. And such knowledge is power.

7 Ploughing

While Scotland’s hunter-gatherers were measuring time, their contemporaries in the Near East had settled down to farm. Crop cultivation is tough work that inspired the first farmers to invent labour-saving devices. The most iconic of these, the plough, might have influenced society in a surprising way.

In the past, as today, hunter-gatherer societies were probably often divided along gender lines, with men hunting and women gathering. Farming promised greater gender equality, because both sexes could work the land, but the plough – which was heavy and so primarily controlled by men – brought an end to that. So argued Danish agricultural economist Ester Boserup in the 1970s. In 2013 Paola Giuliano at the University of California, Los Angeles, and her colleagues tested the idea by comparing gender equality in societies across the world that either adopted the plough or a different form of agriculture. Not only did they confirm the plough effect, they found that it continues to influence gender perceptions today.

8 Sewerage

Farming has been described as the worst mistake in human history: it is back-breaking work. But it did provide such plentiful food that it allowed the growth of urban centres. City living comes with many advantages, but it also carries a health warning: urbanites are at risk from infectious diseases carried by water.

Almost as long as there have been cities, there have been impressive sewerage systems. Cities in the 5,000-year-old Indus Valley society were built above extensive drains. Lavatory-like systems existed in early Scottish settlements dating from around the same time, and there are 3,500-year-old flush toilets and sewers in Crete. But none of these were really designed with sanitation in mind. They were really just to dispose of waste water, often into the nearest river.

It was only in the 1850s, after physician John Snow linked an outbreak of cholera in London to insanitary water supplies, that people started to clean waste water. Large-scale centralized sewage works date from the early decades of the twentieth century. Effective sewerage was a long time coming, but when it did arrive it revolutionized public health.

9 Writing

The engraved ostrich eggshells of Diepkloof show that modern humans have used graphical symbols to convey meaning for at least 100,000 years. But genuine writing was invented only about 5,000 years ago. Ideas could spread and cultural evolution would never be the same again.

Writing also provided a means to convey hopes and fears, revealing how subsequent innovations had affected the human psyche. Some of the world’s oldest texts, from the Mesopotamian city-state of Lagash, rail against the spiralling taxes exacted by a corrupt ruling class. Soon afterwards, King Urukagina of Lagash wrote what is thought to be the first documented legal code. He has gained a reputation as the earliest social reformer, creating laws to limit the excesses of the rich, for instance. But his decrees also entrench the inferior social position of women. One details penalties for adulterous women, but makes no mention of adulterous men. Despite all our revolutionary changes, humanity still had some way to go.