It is an affront to the civilized members of the human race to say that at sentencing in a capital case, a parade of witnesses may praise the background, character and good deeds of the Defendant (as was done in this case) without limitation as to relevancy, but nothing may be said that bears upon the character of, or the harm imposed upon the victims.

—Justice William H. D. Fones, Tennessee Supreme Court, 791 S.W.2d 10 at 28 (criticizing the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Booth v. Maryland)

Irwin and Rose Bronstein were a loving couple, and all who knew them seemed to be most favorably impressed. He was seventy-eight; she, seventy-five. They had been married for fifty-three years. Irwin had worked hard all his life and was now happily retired. Rose was young at heart and had just taught herself to play bridge. It was Friday, May 18, 1984, and spring was busting out all over. The lawn was manicured and the azaleas were in full bloom at their tidy home in Northwest Baltimore. And that's not all that was in full bloom. Their granddaughter was to be married in four days. Life was good—beautiful, one might even say. The Bronsteins had much to look forward to.

The events that would change everything began with a knock on the door. Irwin answered to find a familiar, friendly face, that of twelve-year-old Daryl Brooks who lived two doors down the street and had occasionally done chores for the Bronsteins. Daryl asked if his uncle could use the phone because their phone was out of order. The uncle, John “Ace” Booth, had been living with Daryl and his mother for several weeks. As Irwin let them in, Willie “Sweetsie” Reid—who had been standing off to the side—burst into the house followed by Booth. Once inside, Booth and Reid tied up the couple and gagged them. The child was left outside. The intent was robbery, but it would become far worse.

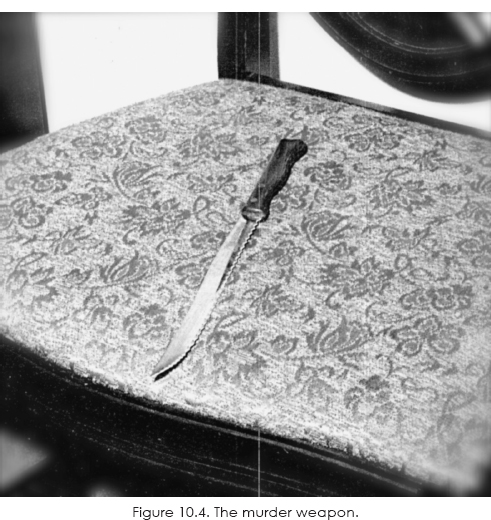

A police report indicates that there was no sign of a struggle, and investigators concluded that the Bronsteins did everything they were told to do. Even so, Booth knew the couple could identify them through Daryl. Armed with twelve-inch serrated kitchen knives, Booth and Reid went to work on the elderly couple, stabbing each of them a dozen times in the neck, chest, and side until dead. They took some cash and a few items from the house. They then went back to the apartment of Reid's's girlfriend, Veronda Mazyck, exchanged some of the cash and goods for heroin, and proceeded to “fire up” on the drugs with some friends. Booth invited his girlfriend, Judy Edwards, over to join the party.

During the course of the evening and out of earshot of other guests, Reid confided to one his friends, Eddie Smith, that he “had just killed a couple of mother fuckers.”1 After their visitors had left, Booth and Reid realized that they didn't get everything from the house that they could have, including the Bronstein's Impala, and thought about going back. They would take their lady friends with them. It was late at night on May 18 or early morning on May 19. When Ms. Edwards arrived at the Mazyck apartment, Booth lied and told her he wanted her to drive the car of a friend of his, that he needed someone who had a driver's license in the event the car was stopped by the police. With that, the four of them piled into a taxi and headed over to the Bronstein's home.

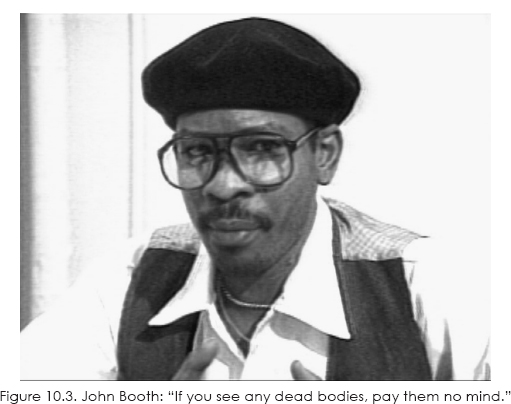

Before they entered the house, Booth had a friendly admonition for the ladies: “If you see any dead bodies, pay them no mind.”2 They then entered the house through the rear door, and the two women saw the bound and gagged corpses of Mr. and Mrs. Bronstein in the living room. The group, with large, green plastic trash bags in hand, immediately proceeded to loot everything in sight. They walked out with jewelry, silverware, and two television sets, among other things; loaded it all into the Bronsteins’ car; and, with Edwards at the wheel, drove off into the night.

Back at the Mazyck apartment, they took some heroin and went to bed, Booth and Edwards sleeping on the sofa in the living room. Edwards later recalled that before dozing off, she repeatedly questioned Booth about the couple at the house. Were they really dead? And who had killed them? “I kept asking him over and over to tell me the truth. Then he said, ‘Yeah, sure. Sweetsie killed the woman and I killed the man. I took care of the man.’ He told me I should have known better than to ask.”

As her parents lay dead in their living room, the Bronsteins’ daughter, Phyllis Bricker, and husband, Bill, were getting ready for their own daughter's wedding. Phyllis had called her parents the night before, but there was no answer. Her brother, Barry Bronstein, had also called his parents on the night of the murders with the same result. Barry and his father were to be ushers at the wedding, and he had been with both his parents earlier in the day. They had a tentative plan for Barry to pick his father up on May 20 so that they might get fitted for their tuxedos. All seemed to be proceeding as planned, however, and there was little concern.

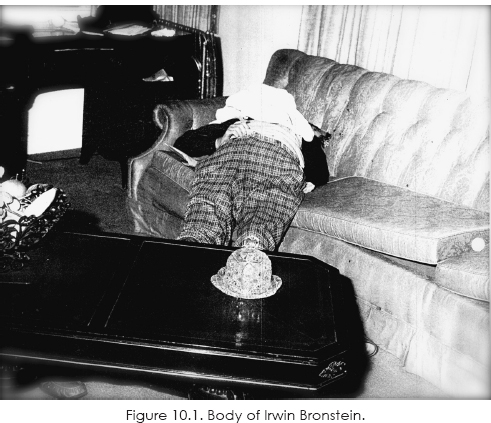

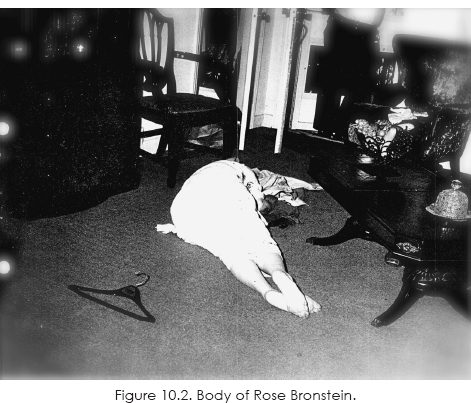

Barry Bronstein showed up dutifully at 4:00 p.m. on May 20 as planned and noticed that the car was gone and the front door was unlocked. The younger Bronstein sensed something was wrong, but nothing could have prepared him for what he saw when he entered his parents’ home. His mother, with hands tied together and a scarf over her face, was lying on the floor in a pool of blood; his father, who was also tied up and gagged, was slouched over the sofa with a plastic bag over his head. His clothing was drenched in blood. They had been dead for two days.

Bronstein called 9-1-1, wept, and then called Phyllis. He told her to come to the house at once, that something terrible had occurred. When Mrs. Bricker got there, she found her parents’ home surrounded by police and television camera crews. She called her daughter to share the news. Surely it must have entered her mind: What about the wedding? It was just two days away. Barry's children, on the other hand, first learned of their grandparents’ death from news bulletins on Baltimore television stations.

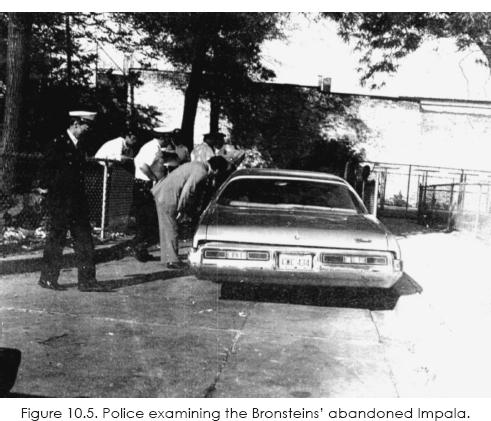

The case was a top priority for Baltimore police. The elder Bronstein's 1972 Impala turned up partially stripped in the parking lot of a public housing project in East Baltimore about three weeks later. Police were able to link Booth with the abandoned car and arrested him on June 7, 1983. Booth had married Judy Edwards only five days earlier. They would never be together again.

The case against both Ace Booth and Sweetsie Reid was strong. The women, Veronda Mazyck and Judy Edwards, had also been charged as “accessories after the fact.” Both testified for the prosecution in exchange for reduced charges. In Booth's case, the jury deliberated for only seven and a half hours before finding him guilty. Prosecutors had made it clear all along that they would be seeking the death penalty, given the brutality of the murders, but that still would take time. There would have to be a presentence investigation. Convicted in April of 1984, the sentencing hearing would not begin until October.

A “victims’ rights” movement had been sweeping the country in the early eighties, and Maryland responded by amending its laws to require juries to consider the impact that murders have on the loved ones of the victims.3 The impact on Barry Bronstein; his sister, Phyllis; and their respective children would be devastating. The jury deciding Booth's fate would learn about it in excruciating detail.

Since the Jewish religion dictates that birth and marriage are more important than death, the wedding of the Bronsteins’ granddaughter had to proceed as planned on May 22. She had been eagerly looking forward to the wedding, but it turned out to be a morbid occasion of exceptional sorrow. Everyone was crying. The reception, which ordinarily would have been a celebration of several hours, was very brief. And the next day, instead of going on their honeymoon, she and her new husband attended her grandparents’ funeral. She later described the events of these few days as a “completely devastating and life-altering experience.”4

The victims’ son, Barry Bronstein, said he was haunted by how he found his parents that afternoon, that he continues to feel their horror and fear. He said he was unable to drive through his parents’ neighborhood or by his father's favorite restaurant or by the supermarket where his parents shopped. His parents weren't just killed, he said. “They were butchered like animals.”

Phyllis Bricker said she was unable to eat for days and that she cried every day for months following the murders. The jury heard how a part of Phyllis had also died along with her parents. The job of cleaning out her parents’ home had fallen to her, and it took weeks. She saw the bloody carpet, knowing that her parents had been there, had died there, and she felt like getting down on the rug and holding them close to her.

The defense objected to this recitation but was overruled, given that such statements are not only allowed but even required under Maryland law. The Bronsteins’ victim impact statement had been used in the trial of Willie “Sweetsie” Reid as well as that of John “Ace” Booth. And it appears to have been effective. Although the Maryland statute expressly prohibits those left behind from recommending the punishment, the jury got the message. Both defendants were sentenced to die in Maryland's seldom-used gas chamber.5

In Maryland, as in most states since the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Gregg v. Georgia, death sentences are automatically reviewed by the state's highest court, which in Maryland is the Court of Appeals. Booth's court-appointed lawyers had raised nineteen different issues on which they claimed the conviction, death sentence, or both should be overturned, ranging from jury selection to jury instructions, from the sufficiency of the evidence to the allegedly inflammatory closing arguments by the prosecutor. The court rejected all nineteen claims in a thirty-page opinion, dismissing the defense's challenge to the victim impact statement in a few simple paragraphs.

The admissibility of the victim impact statement, however, would be the one and only question that would get the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court five months later on October 16, 1986, when it agreed to review the Booth case. The debate would focus less on arcane nuances of constitutional law than on simple issues of accountability and blame that could divide brother and sister around the breakfast table just as it would the Supreme Court.

Booth's attorneys had argued in the Maryland Court of Appeals that victim-impact evidence injects an arbitrary factor into the death-penalty decision and that it has no bearing on the defendant's culpability. His new team of lawyers tried to press that same point in the U.S. Supreme Court.6

Booth was represented by attorney George E. Burns, who specialized in appellate practice in the Baltimore Public Defender's Office: “The state argues that this [the impact of a murder on loved ones] is still part of the circumstances of the crime. The argument really comes down to no more than saying, ‘If I cast a pebble into the ocean, the ripples just go on forever.’…The problem with that, I think, is not only has it never been used as a basis for criminal sentencing, it's probably not even a good basis for tort law…. The implications are simply staggering, because I think it's fair to say that each and every one of us is offended by violent crime. That being the case, there's no reason every citizen who is offended by this shouldn't come in and express that view. Indeed, we might have an 800-number linked up to the courtroom. People can call in.”

Justice Sandra Day O'Connor appeared skeptical.

O'Connor: Mr. Burns, do you suppose that it's possible for a State to make it an aggravating circumstance to murder someone who is a policeman?

Burns: I think it is, Justice O'Connor, if I may add one thing. I think it would have to be that you would have to have reason to know it is a policeman as opposed to not.

O'Connor: Maybe, maybe not.

Most states do allow the judge or jury—whoever is doing the sentencing—to consider the impact of the crime on victims in non-capital cases. Burns's argument was that in cases where the punishment is death, the risk that the decision may be based on passion or sympathy for the victims may be too great. Burns emphasized that the punishment should be based on the defendant's “evil heart,” that which he knew he was doing, and not based on some unforeseeable consequence, such as the impact on loved ones unknown to the perpetrator.

Justice Scalia wasn't buying, pointing out that unintended consequences are routinely a factor in sentencing.

Scalia: Let's assume I'm pulling a bank robbery and I aim at a guard intending to kill him. If I happen to kill him, I'm liable for much graver punishment than if my aim is bad and he's only wounded, correct?

Burns: I'm not sure, Your Honor, because in one case you have murder, and in one, attempted murder…. You have, in Maryland, at least life in each case.

Scalia: Well, I think you certainly would not deny that a State can have different punishments, and considerably different, for a murder that goes awry, and one that is actually committed.

Burns: I agree, Your Honor.

Scalia: Although the evil of the person who pulls the trigger, the blackness of his soul, is exactly the same, right? He's just as bad a person.

Burns: I agree, Your Honor.

The distinguished Supreme Court jurist, Oliver Wendell Holmes, has been famously quoted as saying that “the life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.”7 Maybe Holmes had it wrong. This victim-impact issue does not turn on experience or any abstract nuances of constitutional law. Here, logical thinking may be more helpful than any deep understanding of what the framers said, or meant to say, when they drafted the Bill of Rights. This case, like many, is all about logic and illustrates—perhaps more than most—that sound logic can often lie on both sides of an issue.

The case split the Court 5–4,8 with Justice Lewis Powell writing for the majority and departing from his conservative allies to throw out Booth's death sentence. Powell had already announced his retirement; he would be gone from the Court in two weeks. He was having growing doubts about capital punishment and deep concerns about what he considered irrelevant factors that seep into death-penalty sentencing. One of those factors was the role that race played and his own decision in McCleskey v. Kemp that he eventually would repudiate (see chap. 4). Another was the role of victim impact statements. Powell was joined by Justices Thurgood Marshall and William Brennan (whose votes were predictable given their opposition to capital punishment in all cases) as well as Justices John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun. Powell wrote that the impact on loved ones of the murder victim simply isn't relevant in determining whether the perpetrator should get a death sentence:

While the full range of foreseeable consequences of a defendant's actions may be relevant in other criminal and civil contexts, we cannot agree that it is relevant in the unique circumstance of a capital [death penalty] sentencing hearing. When carrying out this task the jury is required to focus on the defendant as a “uniquely individual human being.” The focus of a VIS [victim impact statement], however, is not on the defendant, but on the character and reputation of the victim and the effect on his family. These factors may be wholly unrelated to the blameworthiness of a particular defendant. As our cases have shown, the defendant often will not know the victim, and therefore will have no knowledge about the existence or characteristics of the victim's family. Moreover, defendants rarely select their victims based on whether the murder will have an effect on anyone other than the person murdered. Allowing the jury to rely on a VIS therefore could result in imposing the death sentence because of factors about which the defendant was unaware, and that were irrelevant to the decision to kill. This evidence thus could divert the jury's attention away from the defendant's background and record, and the circumstances of the crime.

Powell also expressed concerns that the sentencing hearing could degenerate into a mini-trial on the victim's character, the prospect of which “is more than simply unappealing; it could well distract the sentencing jury from its constitutionally required task—determining whether the death penalty is appropriate in light of the background and record of the accused and the particular circumstances of the crime.”

Powell also observed that the Bronstein family was “articulate and persuasive in expressing their grief and the extent of their loss. But in some cases the victim will not leave behind a family, or the family members may be less articulate in describing their feelings even though their sense of loss is equally severe. The fact that the imposition of the death sentence may turn on such distinctions illustrates the danger of allowing juries to consider this information. Certainly the degree to which a family is willing and able to express its grief is irrelevant to the decision whether a defendant, who may merit the death penalty, should live or die.”

Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Justice Byron White, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, and Justice Antonin Scalia dissented. After reviving his bank-robbery hypothetical from the oral argument three months earlier, Scalia wrote:

It seems to me, however—and I think to most of mankind—that the amount of harm one causes does bear upon the extent of his personal responsibility. We may take away the license of a driver who goes 60 miles an hour on a residential street; but we will put him in jail for manslaughter if though his moral guilt is no greater, he is unlucky enough to kill someone during the escapade.

And, added Scalia, it should make no difference in capital cases, drawing on the Tison brothers’ case regarding non-triggermen (Chapter 8):

Less than two months ago, we held that two brothers who planned and assisted in their father's escape from prison could be sentenced to death because in the course of the escape, their father and an accomplice murdered a married couple and two children. Had their father allowed the victims to live, the brothers could not be put to death; but because he decided to kill, the brothers may. The difference between life and death for these two defendants was thus a matter “wholly unrelated to their blameworthiness.” But it was related to their personal responsibility, i.e., to the degree of harm that they had caused. In sum, the principle upon which the Court's opinion rests—that the imposition of capital punishment is to be determined solely on the basis of moral guilt—does not exist, neither in the text of the Constitution, nor in the historic practices of our society, nor even in the opinions of this Court.”

|

For a video report on the Booth Supreme Court case, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/booth |

The Court's decision was announced on June 15, 1987. Eleven days later, Powell's tenure on the Court was over. Might the conservative, law-and-order minded president Ronald Reagan appoint someone more sensitive to the rights of victims (and, by extension, less sensitive to the rights of criminal defendants)? Robert Bork, an academic who, only five years earlier, had been named to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, was just such a candidate. The stage was set for a nasty confirmation fight, less perhaps because of the characteristics of the nominee than of the justice he would replace. For years, the Court had had a delicate ideological balance. Replacing a moderate like Lewis Powell with a conservative heavyweight like Robert Bork could shift the direction of the Court on victim impact statements and a whole lot more. The opposition was formidable, and successful. Bork's nomination was rejected by the full U.S. Senate by a vote of 58–42.

Powell's seat eventually went to Anthony Kennedy, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, who was not as well-known as Bork but was still widely considered a reliable conservative, particularly on matters of criminal justice. Kennedy took his seat on the Court on February 18, 1988. The decision in Booth was only nine months old, and some felt, given the departure of its author, it was already ripe for the graveyard.

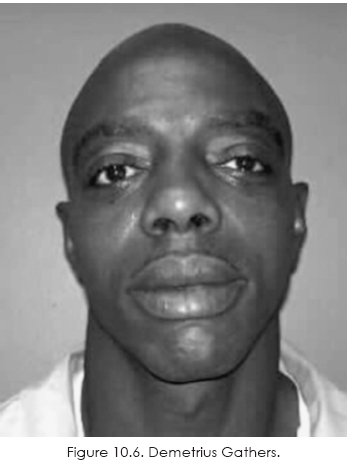

The first test would come soon enough. The following October, in Anthony Kennedy's first full term, the Court agreed to consider the case of South Carolina v. Gathers.9 Demetrius Gathers was convicted of murder and sentenced to death for the killing of Richard Haynes, an unemployed thirty-one-year-old with a history of mental disorder.

The principle issue in Booth v. Maryland involved the impact of a murder on loved ones of the victim and only peripherally involved the characteristics of the victims themselves. In the Gathers case, the focus was exclusively on the victims and whether juries should be permitted to consider the personal characteristics of the victim in deciding the fate of his or her murderer. The Court's reasoning in the Booth case would come into play, giving the reconstituted Court an opportunity for an about-face. All eyes would be on Justice Kennedy (as they would be for the next twenty-five years, during which Kennedy has demonstrated a remarkable ability to almost always be on the winning side in cases decided 5–4, and often he would author the majority opinion).

The facts of the case were every bit as brutal as they were in the Booth case. Gathers and three companions were convicted of assaulting Haynes, beating and kicking him severely, and smashing a bottle over his head. They went through all his belongings, looking for something worth taking, apparently in vain. Before leaving the scene, Gathers beat Haynes with an umbrella, which he then stuffed into the victim's rectum. Sometime later, he apparently returned to the scene and stabbed Haynes with a knife, making sure he was dead.

Although he had no formal religious training, Haynes considered himself a preacher and referred to himself as “Reverend Minister”; his mother testified that he would “talk to people all the time about the Lord.” He generally carried with him several bags containing articles of religious significance, including two Bibles, rosary beads, plastic statues, olive oil, and religious tracts. Among these items, on the evening of his murder, was a tract titled “The Game Guy's Prayer.” Relying on football and boxing metaphors, it extolled the virtues of the good sport. He also carried a voter registration card.

Prosecutors offered no new evidence at the sentencing phase of Gathers's trial, but in their closing arguments, seeking the death penalty, they did comment on the victim's belongings recovered from the crime scene.

We know from the proof that Reverend Minister Haynes was a religious person. He had his religious items out there. This defendant strewn [sic] them across the bike path, thinking nothing of that.

Among the many cards that Reverend Haynes had among his belongings was this card. It's in evidence. Think about it when you go back there. He had this [sic] religious items, his beads. He had a plastic angel. Of course, he is with the angels now, but this defendant Demetrius Gathers could care little about the fact that he is a religious person. Cared little of the pain and agony he inflicted upon a person who is trying to enjoy one of our public parks.

But look at Reverend Minister Haynes’ prayer. It's called the Game Guy's Prayer. “Dear God, help me to be a sport in this little game of life. I don't ask for any easy place in this lineup. Play me anywhere you need me. I only ask you for the stuff to give you one hundred percent of what I have got. If all the hard drives seem to come my way, I thank you for the compliment. Help me to remember that you won't ever let anything come my way that you and I together can't handle. And help me to take the bad break as part of the game. Help me to understand that the game is full of knots and knocks and trouble, and make me thankful for them. Help me to be brave so that the harder they come the better I like it. And, oh God, help me to always play on the square. No matter what the other players do, help me to come clean. Help me to study the book so that I'll know the rules, to study and think a lot about the greatest player that ever lived and other players that are portrayed in the book. If they ever found out the best part of the game was helping other guys who are out of luck, help me to find it out, too. Help me to be regular, and also an inspiration with the other players. Finally, oh God, if fate seems to uppercut me with both hands, and I am laid on the shelf in sickness or old age or something, help me to take that as part of the game, too. Help me not to whimper or squeal that the game was a frame-up or that I had a raw deal. When in the falling dusk I get the final bell, I ask for no lying, complimentary tombstones. I'd only like to know that you feel that I have been a good guy, a good game guy, a saint in the game of life.”…

You will find some other exhibits in this case that tell you more about a just verdict. Again this is not easy. No one takes any pleasure from it, but the proof cries out from the grave in this case. Among the personal effects that this defendant could care little about when he went through it is something that we all treasure. Speaks a lot about Reverend Minister Haynes. Very simple yet very profound. Voting. A voter's registration card.

Reverend Haynes believed in this community. He took part. And he believed that in Charleston County, in the United States of America, that in this country you could go to a public park and sit on a public bench and not be attacked by the likes of Demetrius Gathers.

Was all this relevant in determining whether Gathers should get a death sentence? The Court said no, adhering to its decision in Booth v. Maryland. The Court again was divided 5–4, with Justice Brennan, the Court's premiere death-penalty opponent, writing the majority opinion. Justice Kennedy did as expected, voting to allow the jury to consider all the characteristics of the victim in deciding the fate of his killer. The surprise was Justice White, who had dissented in Booth and argued strongly that it was wrongly decided. White joined the majority opinion in the Gathers case, however, and explained why in a separate, two-sentence concurrence: “Unless Booth v. Maryland, 482 U.S. 496 (1987), is to be overruled, the judgment below must be affirmed. Hence, I join Justice Brennan's opinion for the Court.” White's colleagues were not prepared to go so far as to overrule Booth, at least not in this case.

The Court has historically been loath to overrule itself, in part because doing so creates inconsistency in the law, which is generally thought undesirable. The principle is well known to students of the law as stare decisis, the policy of the Court to stand by precedent (the body of prior rulings that make up the core of the Court's history). The Latin term is actually short for stare decisis et quieta non movere—“to stand by and adhere to decisions and not disturb what is settled.” Or, in the oft-quoted words of Justice Louis Brandeis, “In most matters, it is more important that the applicable rule of law be settled than that it be settled right.”10 The fact that a case has merely been determined to have been wrongly decided is seldom sufficient to overrule it. The justices may also ask whether the decision has turned out to be unworkable, whether it has won acceptance, whether overruling a decision would create more chaos than it resolves, and, as we have seen, whether the decision conflicts with “the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”11 The fact that a decision has endured for many years may also work in its favor, as in Roe v. Wade (1973), the well-known ruling that legalized abortion. The fact that Booth was of such recent vintage, only two years old, made it more vulnerable.

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote separately in the Gathers case to say he would overrule Booth in a heartbeat: “I would think it a violation of my oath to adhere to what I consider a plainly unjustified intrusion upon the democratic process in order that the Court might save face.” But three other justices who had dissented in Booth felt that Gathers was not the right case. Justice O'Connor, joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Kennedy, said she was “ready to overrule” but that it was not necessary in the Gathers case and that reaching out to answer a question not presently before them might violate time-honored principles of judicial restraint. It wouldn't take long, however, for the “right” case to reach the Court's marbled doorstep.

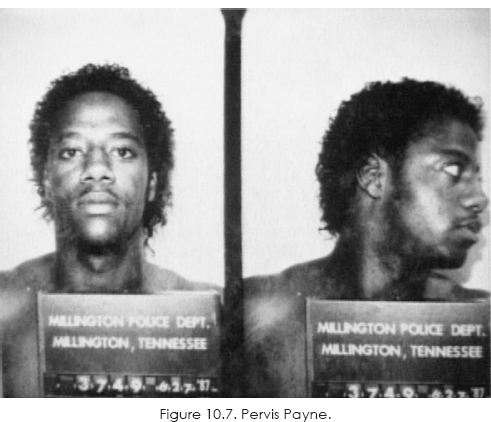

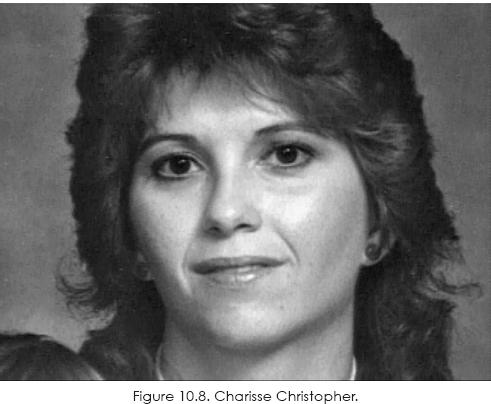

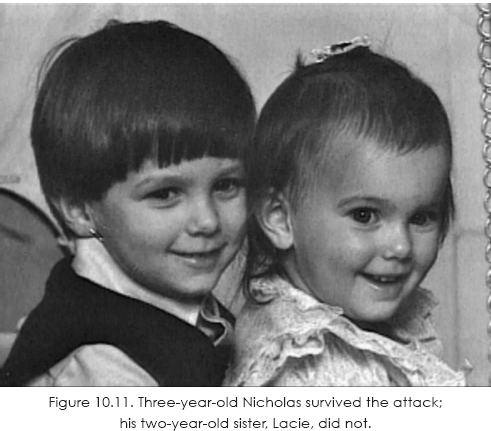

The day after Justice Lewis Powell said good-bye to his colleagues at the Supreme Court, events would unfold in the small town of Millington, Tennessee, about fifteen miles north of Memphis, that would test the opinion of the Court in Booth v. Maryland.12 It was Saturday, June 27, 1987. Pervis Payne was visiting his girlfriend, Bobbie Thomas, with hopes of perhaps spending the weekend there. But she was not at home. So he spent the time waiting around, drinking malt liquor, using cocaine, and driving around town with a friend, each taking turns reading a pornographic magazine. It was now 3:00 p.m. and there was still no sign of his girlfriend. So Payne entered the unlocked apartment across the hall where twenty-eight-year-old Charisse Christopher lived with her two-year-old daughter, Lacie, and her three-year-old son, Nicholas.

Payne began making sexual advances toward Charisse. When she resisted, Payne became violent. A neighbor who lived in the apartment directly beneath the Christophers heard Charisse screaming, “‘Get out, get out,’ as if she were telling the children to leave.” The noise briefly subsided and then began again, “horribly loud.” The neighbor called the police after she heard a “blood-curdling scream” from the Christophers’ apartment.

When the first police officer arrived at the scene, he immediately encountered Payne, who was leaving the apartment building, so covered with blood that he appeared to be “sweating blood.”13 The officer confronted Payne, who responded, “I'm the complainant.” When the officer asked, “What's going on up there?” Payne struck the officer with his overnight bag and fled.

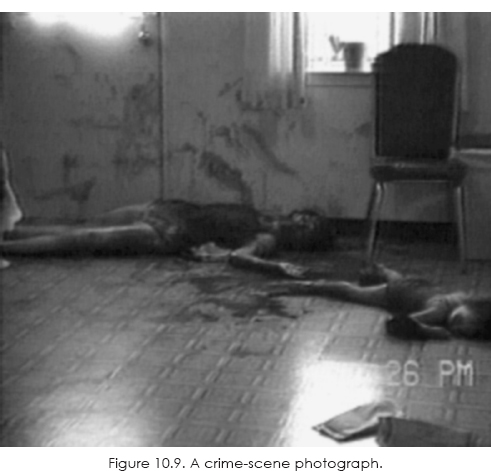

Inside the apartment, the police encountered a horrifying scene. Blood covered the walls and floor throughout the unit. Charisse and her children were lying on the floor in the kitchen. Nicholas, despite several wounds inflicted by a butcher knife that completely penetrated his body from front to back, was still breathing. Miraculously, he survived, but only after undergoing seven hours of surgery and a transfusion of 1,700 cc's of blood—400 to 500 cc's more than his estimated normal blood volume. Charisse and Lacie were dead.

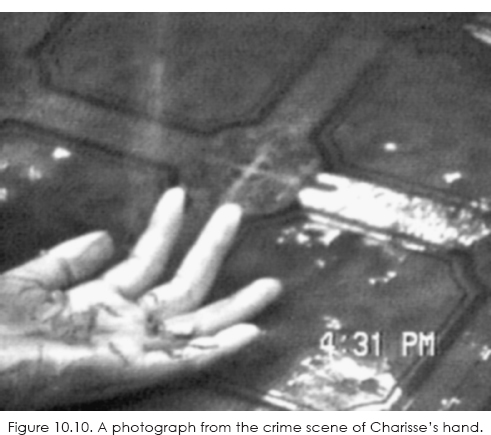

Charisse's body was found on the kitchen floor; she was on her back. She had sustained forty-two direct knife wounds and forty-two defensive wounds on her arms and hands. The wounds were caused by forty-one separate thrusts of a butcher knife. None of the eighty-four wounds inflicted by Payne was individually fatal; rather, the cause of death was most likely bleeding from all of the wounds.

Lacie's body was on the kitchen floor near her mother. She had suffered stab wounds to the chest, abdomen, back, and head. The murder weapon, the same butcher knife used on Charisse, was found at her feet. Payne's baseball cap was snapped on her arm near her elbow. Three cans of malt liquor bearing Payne's fingerprints were found on a table near her body, and a fourth empty one was on the landing outside the apartment door.

Payne was apprehended later that day, hiding in the attic of the home of a former girlfriend. As he descended the stairs of the attic, he stated to the arresting officers, “Man, I ain't killed no woman.” He had blood on his body and clothes and several scratches across his chest. It was later determined that the blood stains matched the victims’ blood types. A search of his pockets revealed a packet containing cocaine residue, a hypodermic syringe wrapper, and a cap from a hypodermic syringe. His overnight bag, containing a bloody white shirt, was found in a nearby dumpster. Payne was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder and one count of assault with intent to commit murder.14

Charisse's mother, Mary Zvolanek, was permitted to testify about how the murders had affected the surviving child, Nicholas, but she didn't say very much: “He cries for his mom. He doesn't seem to understand why she doesn't come home. And he cries for his sister, Lacie.”

“He comes to me many times during the week and asks me, ‘Grandmama, do you miss my Lacie?’ And I tell him yes. He says, ‘I'm worried about my Lacie.’”

In urging the jury to return a death sentence, the prosecutor amplified the grandmother's testimony:

We do know that Nicholas was alive. And Nicholas was in the same room. Nicholas was still conscious. His eyes were open. He responded to the paramedics. He was able to follow their directions. He was able to hold his intestines in as he was carried to the ambulance. So he knew what happened to his mother and baby sister….

Somewhere down the road Nicholas is going to grow up, hopefully. He's going to want to know what happened. And he is going to know what happened to his baby sister and his mother. He is going to want to know what type of justice was done. He is going to want to know what happened. With your verdict, you will provide the answer.

You saw the videotape this morning. You saw what Nicholas Christopher will carry in his mind forever. When you talk about cruel, when you talk about atrocious, and when you talk about heinous, that picture will always come into your mind, probably throughout the rest of your lives….

No one will ever know about Lacie Jo because she never had the chance to grow up. Her life was taken from her at the age of two years old. So, no there won't be a high school principal to talk about Lacie Jo Christopher, and there won't be anybody to take her to her high school prom. And there won't be anybody there—there won't be her mother there or Nicholas’ mother there to kiss him at night. His mother will never kiss him good night or pat him as he goes off to bed, or hold him and sing him a lullaby.15

At one point during the closing argument, Assistant District Attorney Phyllis Gardner staged a grisly reenactment for the jury.

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, this is the last thing I am going to say to you. But I want you to think about this when you go back into your jury room. We have heard a lot about Charisse Christopher, Lacie Jo and Nicholas, and here they were as they appeared before Pervis Payne came into their lives. And this is what he did to them. Did they deserve it? Are you going to let it go unpunished?16

As Gardner uttered “And this is what he did to them,” she approached one of the exhibits, a large diagram of Nicholas Christopher's body, and stabbed a hole through it with another exhibit, the butcher knife found between the bodies of Charisse and Lacie. Payne was sentenced to death for each of the murders and to thirty years in prison on the charge of assault with intent to murder.

The Tennessee Supreme Court was deeply offended by Gardner's stabbing demonstration during her closing argument, finding it “an improper argument, an improper, unprofessional act and an improper use of exhibits.”17 Given all the other evidence against Payne, however, the court felt it did not affect the outcome and thus was “harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The court also concluded that Mrs. Zvolanek's testimony about the impact of the murders on her grandson was not nearly as inflammatory as the testimony of the Bronsteins’ family in Booth v. Maryland and, even if it were, allowing it would also have been harmless in light of the other evidence produced at the trial. The court concluded that given the “inhuman brutality” of the crime, once the identity of the perpetrator “was established by the jury's verdict, the death penalty was the only rational punishment available.” The Tennessee court also took a parting shot at the U.S. Supreme Court's decisions in Booth and Gathers: “It is an affront to the civilized members of the human race to say that at sentencing in a capital case, a parade of witnesses may praise the background, character and good deeds of the defendant (as was done in this case), without limitation as to relevancy, but nothing may be said that bears upon the character of, or the harm imposed upon the victims.”

Payne's attorneys took their appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, but there was an unexpected new development that would seriously jeopardize their case. Four months after the Tennessee Supreme Court had ruled, Justice Brennan—who had joined the Booth majority and had written the decision of the Court in Gathers—appeared to have suffered a series of minor strokes. He was told by his doctors that he had to slow down, that continuing on the Court would entail enormous personal risk. On July 20, 1990, the word was out: Brennan was stepping down. President George H. W. Bush would choose as Brennan's successor David Souter, who only a few months earlier had been named to the First U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston after having served seven years on the New Hampshire Supreme Court.

Justice Kennedy had already played his hand on victim impact statements, agreeing with the Booth dissenters that such evidence should be allowed. Souter was perceived to be a likely ally for allowing the use of victim impact statements as well. The Booth and Gathers decisions appeared all but doomed. In their petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, Payne's lawyers argued only that the Tennessee Supreme Court had failed to apply the Court's precedents on victim impact statements, a failure that would require a new sentencing hearing. Some of the justices, however, were all but itching to have another look at the victim-impact issue; the time was right, given the new composition of the Court, and so was the case. As a result, the Court took the unusual step of ordering Payne's lawyers to also address whether the Booth and Gathers decisions should be overruled; and the justices took the unusual step of setting the case for “expedited consideration.”18 The hearing would be held in only two months. It was already mid-February and other cases accepted at this time would have their hearings scheduled in the succeeding term, which wouldn't begin until October. Both Booth and Gathers were 5–4 decisions, however, and two of the justices in the majority in each case—Powell and Brennan—were now gone. The three other justices who had prevailed in those cases—Marshall, Stevens, and Blackmun—all dissented from the Court's order expanding the issue and expediting review.

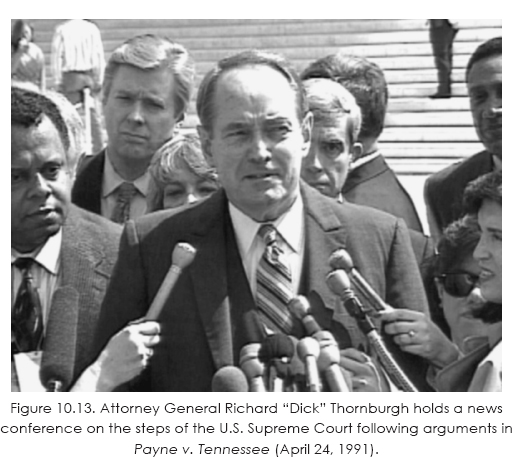

The U.S. Justice Department also had a stake in the outcome of the case because federal sentencing guidelines that had just been enacted could be affected. The department had filed a “friend of the Court” brief in support of Tennessee. Perhaps recognizing the significance of the issue, or perhaps foreseeing a slam dunk for the government, Attorney General Dick Thornburgh announced that he would personally argue for the government in the Supreme Court.

The Court's decision was announced on June 27, 1991, four years to the day after the brutal murders in Millington. To no great surprise, the Court overruled itself on both Booth and Gathers in its 6–3 decision. Given the extraordinary turn of events, Chief Justice Rehnquist assigned the opinion of the Court to himself. Justices Marshall, Stevens, and Blackmun again dissented.

Justice Marshall was particularly passionate in his dissent.

Power, not reason, is the new currency of this Court's decision-making. Four Terms ago, a five-Justice majority of this Court held that “victim impact” evidence of the type at issue in this case could not constitutionally be introduced during the penalty phase of a capital trial [Booth v. Maryland]. By another 5-4 vote, a majority of this Court rebuffed an attack upon this ruling just two Terms ago [South Carolina v. Gathers]. Nevertheless, having expressly invited respondent to renew the attack, today's majority overrules Booth and Gathers and credits the dissenting views expressed in those cases. Neither the law nor the facts supporting Booth and Gathers underwent any change in the last four years. Only the personnel of this Court did.

In dispatching Booth and Gathers to their graves, today's majority ominously suggests that an even more extensive upheaval of this Court's precedents may be in store. Renouncing this Court's historical commitment to a conception of “the judiciary as a source of impersonal and reasoned judgments,” the majority declares itself free to discard any principle of constitutional liberty which was recognized or reaffirmed over the dissenting votes of four Justices and with which five or more Justices now disagree. The implications of this radical new exception to the doctrine of stare decisis are staggering. The majority today sends a clear signal that scores of established constitutional liberties are now ripe for reconsideration, thereby inviting the very type of open defiance of our precedents that the majority rewards in this case. Because I believe that this Court owes more to its constitutional precedents in general and to Booth and Gathers in particular, I dissent.19

The Payne decision was a triumph for Justice Scalia on an issue that he, too, felt passionately about, and in a concurring opinion, Scalia responded to Marshall's dissent.

The response to Justice Marshall's strenuous defense of the virtues of stare decisis can be found in the writings of Justice Marshall himself. That doctrine, he has reminded us, “is not ‘an imprisonment of reason.’” If there was ever a case that defied reason, it was Booth v. Maryland, imposing a constitutional rule that had absolutely no basis in constitutional text, in historical practice, or in logic. Justice Marshall has also explained that “the jurist concerned with public confidence in, and acceptance of the judicial system might well consider that, however admirable its resolute adherence to the law as it was, a decision contrary to the public sense of justice as it is, operates, so far as it is known, to diminish respect for the courts and for law itself.”…

Today, however, Justice Marshall demands of us some “special justification”—beyond the mere conviction that the rule of Booth significantly harms our criminal justice system and is egregiously wrong—before we can be absolved of exercising “power, not reason.” I do not think that is fair. In fact, quite to the contrary, what would enshrine power as the governing principle of this Court is the notion that an important constitutional decision with plainly inadequate rational support must be left in place for the sole reason that it once attracted five votes.20 (italics in the original)

Justice O'Connor, joined by Justices White and Kennedy, also wrote separately to point out that there is nothing in the decision to compel victim impact statements, and in some cases, they still may be inadmissible.

We do not hold today that victim impact evidence must be admitted, or even that it should be admitted. We hold merely that if a State decides to permit consideration of this evidence, “the Eighth Amendment erects no per se bar.” If, in a particular case, a witness’ testimony or a prosecutor's remark so infects the sentencing proceeding as to render it fundamentally unfair, the defendant may seek appropriate relief under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.21(italics in the original)

|

For a video report on the Payne Supreme Court case, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/payne |

In 1953, Justice Robert Jackson described the authority of the Supreme Court this way: “We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final.”22 As the Booth-Gathers-Payne trilogy of cases amply demonstrates, the decisions of the Supreme Court are not always final. And there are numerous other cases that also amply demonstrate that the Court is hardly infallible. The Court's Dred Scott decision all but ignited the Civil War by declaring slaves to be property23; Plessy v. Ferguson's separate-but-equal ruling stood as a monument to racial segregation in public facilities for almost sixty years.24 Korematsu v. United States,25 upholding the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II solely because of their race, stands as a lasting monument to bigotry and how, in the words of Oliver Wendell Holmes, “hard cases make bad law.”26 Korematsu has never been overruled.

We tend to think of the U.S. Supreme Court as the last word on the Constitution and, as a result, may attribute power to the justices that they really do not enjoy. In some respects, Supreme Court justices have more restraints than any other judge. For one, they cannot pass a difficult question on to a higher court. And if the Supreme Court gets it wrong on an important question of constitutional law, Congress is all but powerless and there is no other court around to correct them. Accordingly, the justices have a unique responsibility to get it right. And there are serious repercussions when they fail. The damage can be enormous, the difference between life or death in the context of the death-penalty debate. Supreme Court justices must answer to their own conscience, future Supreme Courts that can overrule them, and—as Chief Justice Roger Taney would understand were he around today—the long shadow of history. Taney was widely regarded as a great chief justice and, in some quarters, still is. But his standing in history is forever tarnished by his single opinion in Dred Scott, igniting the Civil War.

So did the Supreme Court finally get it right on the victim-impact question? Or did it merely take an ill-advised U-turn? The Court's decision upheld the death sentence for Purvis Payne, but twenty-five years after the double murder, he remains alive on death row in Tennessee with appeals pending. Demetrius Gathers's death sentence was subsequently commuted to life without parole. As for John Booth, whose case started it all, the decision in Booth v. Maryland led to a new sentencing hearing without the victim impact statement. He was resentenced to death again only to have the Maryland Court of Appeals again reverse the sentence because of an improper jury instruction. Booth was sentenced to death a third time, but that also was reversed by the Maryland Court of Appeals because the jury was not allowed to consider that Booth was high on heroin and alcohol on the afternoon of the killings. He has been on death row in Maryland for almost thirty years, longer than any other inmate in the state. There is now a campaign in Maryland to do away with capital punishment, and the state's governor, Martin O'Malley, says there is not enough sodium thiopental in the prison system to carry out executions. O'Malley, a death penalty foe, says the shortage “underscores what a laborious and complicated and time-consuming resource-wasting legal process goes into carrying out the death penalty.”27

Phyllis and William Bricker have traveled to the state capitol in Annapolis and to court in Baltimore many times over the years in support of capital punishment. Booth attended one of the court hearings that seemed to go nowhere. At the end of the day, Phyllis remembers Booth turning from the defense table to look at her and whisper in her direction, “See you next year.”28