After what he had experienced in Moscow, Alexander found the mood of St Petersburg depressingly defeatist when he returned there at the beginning of August. There were some at court who were calling for peace, and even those who were against treating with Napoleon showed little of the exalted courage of the Muscovites. Many, including Alexander’s mother the Dowager Empress, had been packing up and sending away valuables, others had theirs crated up in readiness for a quick evacuation, and most people had horses and carriages waiting. They were all living, as one wit put it, on axle grease.

The only manifestations of patriotism were the beards and Russian clothes sported by some nationalists, and the public’s boycott of the French theatre, where the celebrated Mademoiselle Georges played to empty houses. Performances of Dmitry Donskoi, by contrast, were packed out, but according to one witness took place in an atmosphere more redolent of a church than a theatre, with half of the audience in tears.1

Alexander had retired to his summer residence on Kamenny Island and buried himself in work. He saw less of his mistress and more of the Tsarina, and did not show himself much in public. But he could not ignore the stream of letters from his brother Constantine telling him Barclay was an incompetent coward and a traitor, those from Bagration to Arakcheev, which he saw, saying much the same thing, and the gossip at court – everyone was getting letters from someone in the army, all of them complaining and accusing. There was, in the words of the American ambassador John Quincy Adams, ‘an extraordinary clamour’ against Barclay.2

Alexander stood by his commander as long as he could. He was desperately hoping for some good news, and after hearing that Barclay had abandoned Vitebsk he hoped he would make a stand before Smolensk, and would later express his profound disappointment that he did not. ‘The ardour of the soldiers would have been extreme, for it would have been the entry into the first really Russian city that they would have been defending,’ he wrote to him.3 With the fall of Smolensk, he could no longer go on supporting the despised general without exposing himself to similar feelings. Particularly as public opinion had already selected Barclay’s successor – Kutuzov.

‘Everyone is of the same mind; everyone says the same thing; indignant women, old men, children, in a word all conditions and all ages see in him the saviour of the fatherland,’ wrote Varvara Ivanovna Bakunina to a friend.4 Alexander hated Kutuzov for his immorality, his slovenly manner and his attitude, as well as for the memories of Austerlitz and his father’s murder. He also had a low opinion of his competence. He had rewarded him for making a rapid peace with Turkey by making him a prince, but had then given him an insignificant post. A delegation of St Petersburg nobles came to Kutuzov begging him to accept command of the militia the city was raising, which he did, having obtained Alexander’s approval. This brought him to the capital and back into the limelight.

On the evening of 17 August, just as the battle for Smolensk was beginning, Alexander convened a meeting of senior generals, presided over by Arakcheev, to advise him on the choice of a successor to Barclay. After three and a half hours’ deliberation, they settled on Kutuzov. But Alexander did not act on their advice, prevaricating for a full three days, during which he considered nominating Bennigsen, and even of inviting Bernadotte over from Sweden. His sister urged him to bow to the inevitable. ‘If things go on like this, the enemy will be in Moscow in ten days’ time,’ she wrote, adding that he must under no circumstances even think of assuming command himself. Rostopchin wrote declaring that Moscow was clamouring for Kutuzov. There was nothing for it but to go along with the general mood. ‘In bowing to their opinion, I had to impose silence on my feelings,’ Alexander later wrote to Barclay. ‘The public wanted him, so I appointed him, but as far as I am concerned, I wash my hands of it,’ he said to one of his aides-de-camp.5

Immediately after nominating Kutuzov, Alexander set off for Finland, where he had arranged to meet Bernadotte. According to the agreement their foreign ministers had negotiated in April, Russia was to indemnify Sweden for the loss of Finland (seized by Russia) by permitting her to conquer Norway from Denmark and annex that. Russia was also to support a Swedish invasion of Pomerania to reclaim it from the French. But with Napoleon now advancing into the heart of Russia, there was a distinct possibility that Sweden might seize the opportunity of taking back Finland.

Bernadotte and Alexander met on the island of Åbo, and took an immediate liking to each other. Alexander was relieved to discover that Bernadotte hated Napoleon as much as he did. Bernadotte, it appeared, was taking a longer view, and for good measure Alexander encouraged him in this and at the same time wove him into his own plans for the future by suggesting that when Napoleon was finally defeated and the French throne became vacant, the Crown Prince of Sweden might become the King of France. They parted as friends, and Alexander could safely withdraw the three divisions protecting Finland and redeploy them against Napoleon.6

On his return to St Petersburg, Alexander found that even more people and valuables had left, and those who remained were in despondent mood. They had received news of the fall of Smolensk a few days before, and this confirmed many in the conviction that it was time to open negotiations with Napoleon. Grand Duke Constantine, sent away from headquarters by Barclay after Smolensk, was persuading people that the situation was hopeless. Another who had arrived from Smolensk was the British ‘commissioner’ General Robert Wilson. He brought news of dissension and strife at headquarters which confirmed that Alexander had been right to replace Barclay. He had also appointed himself spokesman for an indeterminate group of patriotic senior officers who, according to him, demanded that the Tsar sack his Foreign Minister Rumiantsev and others tainted with sympathy for France. In the politest terms, Alexander brushed off this preposterous meddling.7

When Kutuzov had walked out of Alexander’s palace on Kamenny Island on the evening of 20 August after receiving his nomination, he had himself driven straight to the cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan. There, taking off his uniform coat and all his decorations, he lowered his great bulk to his knees and began to pray, with tears pouring down his face. On the next day he went, this time accompanied by his wife, to pray in the church of St Vladimir. Two days later, on 23 August, he set off for the front. His carriage could hardly move, such was the throng of people cheering and wishing him well. He stopped at the cathedral once again, to attend a religious service, and knelt throughout. Afterwards, he was presented with a small medallion of Our Lady of Kazan, which was blessed with holy water. ‘Pray for me, as I am being sent forth to achieve great things,’ he is alleged to have said as he left the church.

At a posting station along the way, he encountered Bennigsen travelling in the opposite direction. Alexander had insisted that Kutuzov appoint Bennigsen as his chief of staff, as a safety measure against the new commander-in-chief’s possible treachery as well as his imputed incompetence. Bennigsen was far from pleased when he heard of this, as he had been on his way to St Petersburg hoping to prevail upon Alexander to give him overall command. ‘It was not pleasant for me to serve under another general, after I had commanded armies against Napoleon and the very best of his marshals,’ he later wrote. But when Kutuzov handed him Alexander’s letter begging him to accept, he could not do otherwise.

Another who was far from happy was Barclay. He wrote to Alexander, saying that he was prepared to serve under the new commander, but begging to be relieved of the post of Minister of War, as this would place him in an anomalous and difficult situation. Within a few days of Kutuzov’s arrival at headquarters he wrote again, this time asking to be relieved of command altogether, without success.8

Kutuzov’s arrival in the Russian camp at Tsarevo-Zaimishche was greeted with an explosion of joy in the ranks. ‘The day was cloudy, but our hearts filled with light,’ noted A.A. Shcherbinin. ‘Everyone who could rushed to meet the venerable commander, looking to him for the salvation of Russia,’ according to Radozhitsky. Kutuzov was idolised by junior officers, on whom he lavished a garrulous charm and an avuncular concern. The rank and file trusted the old man, whom they called their ‘batiushka’, their little father. They perked up instantly, carrying out even the most humdrum tasks at the double, as though they were about to go into action, and that evening there was singing around the campfires for the first time in weeks. Old soldiers reminisced about Kutuzov’s feats in the Turkish wars, and assured their younger comrades that henceforth everything would be different.9

Their confidence was not shared by many of the senior officers, who had serious reservations about Kutuzov’s competence and his fitness for the task in hand at his advanced age of sixty-five. This certainly aggravated a natural laziness. ‘For Kutuzov to write ten words was more difficult than for another to cover a hundred pages in writing,’ recorded his duty officer Captain Maievsky. ‘A pronounced gout, age and lack of habit were all enemies of his pen.’ Bagration actually wrote to Rostopchin that replacing Barclay with Kutuzov was like exchanging the frying pan for the fire, or, as he put it, ‘a deacon for a priest’, and referred to the new commander-in-chief as a ‘goose’. But the situation had got so bad that any change was welcome. ‘Many Russians who did not attribute treachery to foreigners, yet believed that the household gods of their country might be indignant at their employment, and that it was therefore unlucky,’ wrote Clausewitz, adding that ‘the evil genius of the foreigners was exorcised by a true Russian’.10

Kutuzov’s distinguishing characteristic was slyness. He had built up an extraordinary reputation, and had managed to convince many that his quirks and eccentricities were marks of genius. One of these quirks was a total disregard for form. He dressed sloppily, preferring a voluminous green frock-coat and round white cap to the uniform of his rank. He addressed generals and subalterns by familiar nicknames, and occasionally struck a populist note by lapsing into foul language. But he always wore all his decorations, and was prone to displays of arrogance. And while writers and film-makers have relentlessly portrayed him as some kind of son of the Russian soil, he was cultivated and refined in his tastes, and gave all his orders in impeccable French.

Unfortunately, his disregard for form extended to the way he gave these. He disdained the proper channels, issuing orders through whoever came to hand. He was secretive and mistrustful, and avoided writing them down if possible. He was not beyond instructing a given unit to carry out some operation without informing the commander of the division or corps of which it formed part, so that generals not infrequently found a section of their command moving off in a different direction as they prepared to go into action. He had an unfortunate habit of assenting to some suggestion without considering its implications for other measures he had taken. He changed his mind often, and did not always inform all the relevant people of the change of plan.

Some of this may have been the result of senility – Clausewitz certainly thought so. But some of the confusion was the result of Bennigsen’s tendency to overstep his prerogatives and of Kutuzov’s entourage, which included his impetuous son-in-law Prince Nikolai Kudashev and the busybody Colonel Kaisarov, who, in Barclay’s words, ‘thought that, being both confidant and pimp, he had no less right to command the army’. All three issued orders in Kutuzov’s name, sometimes failing to notify him.11

‘In the army, people were attempting to work out who was the person who was really in command,’ wrote Barclay. ‘For it was evident to all that Prince Kutuzov was only the cypher under which all his associates acted. This state of affairs gave birth to parties, and parties to intrigues.’12 This was particularly galling to Barclay, who had put so much work into laying down correct procedure. But he continued to serve as commander of the First Army, although he found the situation intolerable.

‘The spirit of the army is magnificent, there are plenty of good generals, and I am full of hope,’ Kutuzov wrote to his wife just after his arrival in camp. But to Alexander he wrote that he had found the army disorganised and tired, and complained about the large numbers of deserters. He liked the position Barclay had chosen at Tsarevo-Zaimishche and his first intention was to give battle there. ‘My present objective is to save Moscow itself,’ he wrote to Chichagov.13

But after assessing the state of his army he felt he could not face Napoleon, whose strength he gauged at 165,000. There were 17,000 reinforcements on their way under General Miloradovich, and Kutuzov decided to fall back and incorporate these into his army, hoping to find a good position to give battle somewhere near Mozhaisk. ‘If the Most High blesses our arms with success, then it will be necessary to pursue the enemy,’ he wrote to Rostopchin, asking him to send supplies and to prepare hundreds of wagons to take away the wounded. He also asked Rostopchin to send him the death-wreaking aerostat he had heard about.14

Barclay suggested a position outside Gzhatsk, but Bennigsen did not like it, and Kutuzov decided to gain more time for reinforcements to be brought up by falling back further. He sent Toll ahead to find another position. He wanted a strong defensive one, as he knew that the Russian soldier was at his most firm when given a rampart or a ditch to defend, and because he believed himself to be seriously outnumbered by Napoleon.

On 3 September Kutuzov rode out to inspect the positions Toll had selected near the village of Borodino. They met with his approval, and soon militiamen were clearing woods, digging earthworks and dismantling entire villages which impeded the field of fire. That evening he established his headquarters at Tatarinovo, some two kilometres east of Borodino, and stayed up late into the night writing. His exhausted men had been arriving all day long, and as they reached their prescribed positions they stacked their muskets in the regulation pyramids and fell asleep.

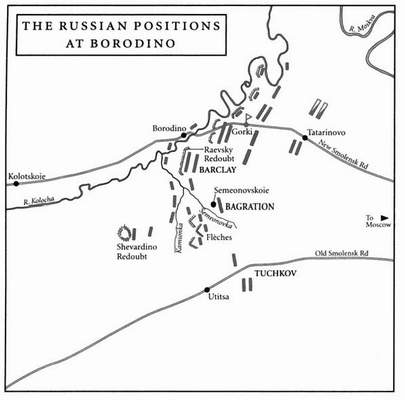

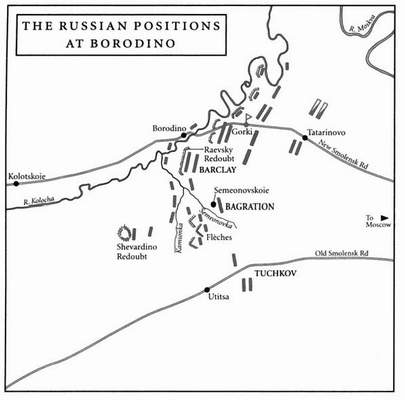

Kutuzov spent much of the following day supervising the preparations. His positions lay along a ridge which ran at an angle to the main road, behind a small tributary of the Moskva river, the Kolocha. In the north, his right wing was anchored in the angle made by the Moskva and the Kolocha, and ran along the high ground behind the Kolocha. He fortified this high ground with four batteries protected by earthworks, and ordered the construction of two redans astride the old Moscow road, in which he positioned twelve heavy guns. The centre of the line was also atop high ground behind the Kolocha, and it was dominated by a hillock which commanded a good field of fire. Kutuzov fortified this with a strong earthwork which was to go down in history as the Raevsky redoubt, about two hundred metres long with embrasures for eighteen cannon. Further along the line, the high ground was cut by the course of a stream, the Semeonovka, and fell away, leaving an expanse of flat ground between the centre and the right wing, which ended on a knoll by the village of Shevardino. Kutuzov closed this gap by constructing three V-shaped redans, or flèches, and had a pentagonal redoubt built on the Shevardino knoll. As the slight depression formed by the bed of the Kamionka stream did not permit the flèches to be built further forward, the Russian positions actually curved backwards at this point, leaving the Shevardino redoubt hanging in a rather exposed position. As a result, nobody was quite sure whether this redoubt was really the tip of the left wing or just an outpost. According to Toll, Kutuzov did not mean it to be part of the line, but only an outpost from which he could ‘observe the enemy’s strength and dispositions’, but he did not bother to inform anyone of this, except for Toll. ‘Kutuzov kept his real intentions on the left wing secret from General Bennigsen,’ according to Toll.15

The lack of clarity probably stemmed from the fact that Kutuzov’s dispositions had to remain fluid. He had taken up a diagonal position athwart the new Smolensk road, which presupposed that the main French thrust would be delivered along that road. ‘I hope that the enemy will attack us in this position, and if he does I have great hopes of victory,’ he wrote to Alexander that evening. ‘But if, finding my position too strong, he starts manoeuvring along other roads leading towards Moscow, I cannot vouch for what might happen.’ The other road which particularly worried him was the old Smolensk road, running past the southern tip of his positions. If Napoleon turned this, he would be forced to fall back on Mozhaisk, ‘but whatever happens, it is essential that Moscow be defended’, he added.16

Early on the morning of 5 September, Murat’s advance guard reached the little monastery at Kolotskoie, from where he could see the Russian army preparing for battle. He immediately notified Napoleon, who appeared at midday. He marched into the monks’ refectory and wished them ‘Bon appétit!’ in bad Polish, then rode out to look at the positions the Russian army had taken up.

He could see that to the north of the new Smolensk road they had occupied high ground whose approaches were made difficult by the river running in front of them, while to the south of the road the flatter ground provided an easier approach. As his own right wing, consisting of Poniatowski’s 5th Corps, was anyway advancing along the old Smolensk road, Napoleon was naturally drawn to aim his principal thrust in this area. Approached from this angle, the tip of the Russian position, the Shevardino redoubt, was a salient that impeded the deployment of his troops. He therefore ordered Davout to liquidate it as a preliminary.

At five o’clock in the afternoon, General Compans’ division duly attacked the redoubt, which was held by Neverovsky’s 27th, and took it. But a spirited Russian counterattack, supported by two fresh divisions, threw the French out. The fighting spilled over to the area around the redoubt, which passed from one side to another several times before, at about eleven o’clock that night, the Russians finally gave up trying to recapture it, and fell back, having lost some five thousand men and five guns. But they took with them eight French guns. This allowed Kutuzov to write to Alexander, announcing a first victory over the French.17

The next day was spent in preparations. ‘There was something sad and imposing in the spectacle of these two armies preparing to murder each other,’ recorded Raymond de Fezensac, one of Berthier’s aides-de-camp. ‘All the regiments had received orders to wear full dress as on a holiday. The Imperial Guard in particular seemed to be preparing for a parade rather than for combat. Nothing could be more striking than the sang-froid of these old soldiers; there was no trace of either enthusiasm or anxiety on their faces. A new battle was for them no more than another victory, and in order to share in that noble confidence one only had to gaze on them.’18

A similar confidence could be felt in the Russian camp. That morning Kutuzov rode out on his white charger to inspect his positions, cheered by the troops, and at one point someone noticed an eagle soaring overhead. News of the assumed omen spread through the camp, filling the men with hope for the morrow. But in stark contrast to the quiet confidence felt by the rank and file, the Russian command was engulfed by argument and recrimination provoked by the fall of the Shevardino redoubt and the pointless loss of so many men. The event also raised questions about the Russian dispositions as a whole.

Whatever his original intentions had been, the fall of the redoubt compelled Kutuzov to bend back his left wing so that his now truncated front could not be outflanked. What seems extraordinary is that as he rode about that day surveying the terrain and the enemy positions, he did not notice that Napoleon was not politely positioning himself symmetrically opposite his front. While Kutuzov had stretched his forces out along a front of some six kilometres diagonally on either side of the Smolensk – Moscow road, Napoleon was coming up in a more compact mass south of that road, and at a different angle, in such a way that he threatened the Russian left wing, which was occupying the weakest positions.

Kutuzov’s northern or right wing, up to and including the Raevsky redoubt, was manned by Barclay’s First Army. The entrenched batteries were protected by screens of jaeger light infantry, skirmisher sharpshooters like the French tirailleurs, occupying forward positions in the village of Borodino and dispersed throughout the bushes and brushwood along the banks of the Kolocha, then by massed ranks of infantry drawn up in columns and by units of cavalry, deployed in front of the earthworks. Behind, Barclay had a strong cavalry force in the shape of General Fyodor Uvarov’s corps and Platov’s cossacks, as well as a number of infantry reserves to call on. This sector was thus more than adequately defended.

The same could not be said of the centre and left, occupied by Bagration with his Second Army. Bagration, with no more than about 25,000 men at his immediate disposal, was seriously overstretched, and the positions he was occupying were poor in natural defences. The only obstacles his attackers would face were the marshy ground in the area at the confluence of the Kamionka and Semeonovka streams, the waist-high walls of the dismantled village of Semeonovskoie, and the three hurriedly built flèches. Kutuzov reinforced the southern wing with General Nikolai Alekseievich Tuchkov’s 3rd Corps, consisting of eight thousand regulars, seven thousand Moscow militia and 1500 cossacks, which he positioned in the woods behind the village of Utitsa. They were concealed from the enemy, and were to remain so until the last moment, as their purpose was to suddenly rise up and launch a flank attack at any French force that tried to turn Bagration’s flank.

Both Bennigsen and Barclay, neither of whom had been informed of the Tuchkov ruse, saw the weakness of the left wing and badgered Kutuzov to reinforce it. Characteristically, he listened to them but said and did nothing. In this case, his disdain for his subordinates worked against him. While riding around the positions later that day, Bennigsen stumbled on Tuchkov’s corps and, as its purpose had not been explained to him, proceeded to reposition it, bringing it out into the open further forward and making it close up with Bagration’s left flank. ‘I have resorted to artifice to strengthen the one weak sector in my line, on the left wing,’ Kutuzov wrote to the Tsar that evening, unaware that his ambush had been dismantled. ‘I only hope that the enemy will attack our frontal positions: if he does, then I am confident that we shall win.’ To Rostopchin he wrote assuring him that if he were beaten he would fall back on Moscow and stake everything on a defence of the ancient capital.19

Had Napoleon been in anything approaching his usual form, Kutuzov would undoubtedly have been routed and the Russian army destroyed. Kutuzov had taken up entirely passive positions which did not give him much scope for manoeuvre and were flawed by the weak underbelly to the south of the Raevsky redoubt. He had compounded the problem by overmanning his right wing, which Napoleon was evidently ignoring, and leaving his vulnerable left wing seriously denuded. Luckily for him, Napoleon was to deliver probably the most lacklustre performance of his military career.

The Emperor had also been busy reconnoitring the field. He was in the saddle at two o’clock in the morning. Accompanied by a suite of staff officers, he had gone to see the redoubt captured the night before, and then rode along the whole line, dismounting several times to observe various points along the Russian line through his telescope. He could not get a clear enough view, and, as it later turned out, made some mistaken assumptions about the terrain. He did not get back to his tent until nine o’clock that morning, and spent the next few hours poring over maps and figures.

He was feeling ill. He had caught a cold, and this had precipitated an attack of dysuria, a condition affecting the bladder from which he suffered periodically. On the previous night he had summoned his personal physician, Dr Mestivier, who had noted that Napoleon had a bad cough and was breathing with difficulty. He could only pass water with great pain, and the urine came in drops, thick with sediment. His legs had swollen and his pulse was feverish. The Emperor’s valet, Constant, recorded that his master had shivering fits and complained of feeling sick. Others noted similar complaints, and all those around him could see that he was unwell over the three vital days of 5, 6 and 7 September.20

At two o’clock that afternoon Napoleon rode out once more for a final survey of the enemy’s positions, during which he explained to his marshals his plan for the morrow. He had spotted the weakness of the Russian left wing, and meant to exploit it. Davout and Ney were to attack the flèches (Napoleon had only spotted two of them through his telescope) while Poniatowski turned the Russian left wing, and then all three, supported by Junot, were to roll up the whole Russian army in a northerly direction, pinning it against the Moskva river and annihilating it completely. Davout suggested an even deeper flanking move, to be delivered by himself and Poniatowski while Ney tied down the Russians, which would have achieved even more spectacular results with greater economy.

But Napoleon was uncharacteristically cautious. He feared that a force sent into the Russian rear might get lost in the unfamiliar terrain. Also, the Russians might retreat the moment they saw their flank threatened, cheating him once more of a chance to annihilate them. He would deliver a strong frontal attack that would suck in Kutuzov’s main forces and defeat them, and in order to deliver this, he actually weakened Davout’s 1st Corps by transferring two of his best divisions, Morand’s and Gérard’s, to the command of Prince Eugène on the left wing, who was to launch the main attack on the Russian centre.

Napoleon’s caution was dictated in part by the number and condition of troops under his command. On 2 September, at Gzhatsk, he had ordered a roll call, and this had yielded a figure of 128,000 men, with another six thousand capable of rejoining the ranks within a couple of days, giving a total of 134,000. It is questionable whether this was an accurate figure, given the well-known tendency of unit commanders to inflate their numbers. Anecdotal evidence supplied by officers who had no interest in magnifying or diminishing the figures would suggest that the official ones are on the high side, particularly where the cavalry was concerned. One officer noted that his squadron of Chasseurs à Cheval was down from an initial strength of 108 men at the outset to no more than thirty-four; several regiments, with an original strength of 1600, were down to no more than 250; one cavalry division had dwindled from 7500 to one thousand. Russian historians currently estimate the French forces at no more than 126,000.21

Either way, the French were outnumbered. While earlier accounts by Russian historians rated Kutuzov’s forces at no more than 112,000, current estimates vary between 154,800 and 157,000. It is true that these include about 10,000 cossacks and 30,000 militia, whose role in the battle would be limited. But if one discounts these, one Russian historian has recently argued, then one must exclude from the French tally the 25,000 or so men of the Imperial Guard, who never fired a shot all day.22

In the event, apart from taking an active part in the fighting, the militia performed the vital task of carrying away the wounded, which meant that regular soldiers could not use this as an excuse to leave the front line – often never to return. The militia also made a cordon behind the front line, which prevented anyone, even senior officers, who were not obviously wounded from leaving it. ‘This measure too was highly salutary, and many soldiers, and, I am sorry to have to say it, even officers, were thus forced to rejoin their colours,’ wrote Löwenstern.23

More significant than the disparity in numbers was the condition of the two armies facing each other. The French units were depleted and disorganised by the need to keep themselves fed, and although they put on their fine parade uniforms and pipeclayed their crossbelts, a great many went into battle virtually barefoot, as their shoes had long since fallen apart. They had not been properly fed for days, and, as one officer in the Grenadiers of the Old Guard pointed out, ‘If General Kutuzov had been able to put off the battle for several days, there is no doubt that he would have vanquished us without a fight, for an enemy mightier than all the arms of the world had laid siege to our camp: that enemy was a vicious hunger which was destroying us.’24 The Russians, on the other hand, were relatively well fed and supplied by a flow of carts coming out of Moscow.

The horses of the French cavalry were in particularly bad condition, and many a charge on the next day would never break into anything more urgent than a trot. The less numerous Russian cavalry were better mounted, and were able to deliver some fierce attacks on the following day.

The greatest discrepancy between the two armies was in the quality of their artillery. The Russians, with 640 pieces, enjoyed outright superiority over the French, who had 584, and a far greater proportion of their guns were heavy-calibre battery pieces, many of them licornes with a longer range than any French gun. Over three-quarters of the 584 French guns were light battalion pieces, useful only in close support of infantry attacks.

Napoleon had a pleasant surprise when he returned from his afternoon reconnaissance. The Prefect of the imperial palace, Louis Jean François de Bausset, had just arrived from Paris with administrative papers. Before his departure, Bausset had gone to François Gérard’s studio to see the painter finish his latest portrait of the King of Rome, lying in his cradle, toying with a miniature orb and sceptre. He had taken the picture in his carriage as he set off on the thirty-seven-day journey to Napoleon’s headquarters. ‘I had thought that being on the eve of fighting the great battle he had so looked forward to, he would put off for a few days opening the case in which the portrait was packed,’ Bausset wrote. ‘I was mistaken: eager to experience the joy of a sight so dear to his heart, he ordered me to have it brought into his tent immediately. I cannot express the pleasure which that sight gave him. Regret at not being able to press his son to his heart was the only thought which troubled such a sweet joy.’25

Like any doting father, Napoleon called in his entourage to have a look, and then had the portrait placed on a folding stool outside his tent, so that everyone could share in his private joy. The troops began to queue up. ‘The soldiers, and above all the veterans, seemed to be deeply moved by this exhibition,’ wrote one staff officer, ‘the officers on the other hand seemed more preoccupied with the fate of the campaign, and one could see anxiety on their faces.’26

‘Ma bonne amie,’ Napoleon scrawled to Marie-Louise that evening, ‘I am very tired. Bausset delivered the portrait of the king. It is a masterpiece. I thank you warmly for thinking of it. It is as beautiful as you are. I will write to you in more detail tomorrow. I am tir[ed]. Adio, mio bene. Nap.’27

Napoleon was not only ill and tired. He was deeply preoccupied. Another who had arrived along with Bausset was Colonel Fabvier, bearing despatches from Spain with details of Wellington’s victory over Marmont at Salamanca. The reverse itself was of no great consequence, but its propaganda value was tremendous, as the Emperor well knew. All his enemies would take heart, as they had after Essling, and this meant that the next day’s battle must be decisive.

He was not the only one who realised this. ‘Many a mind was anxious, many eyes remained open, many reflections were made on the importance of the drama which had been announced for the morrow and whose stage, so far from our motherland, allowed us the choice of either winning or perishing,’ in the words of Julien Combe. Colonel Boulart, of the artillery of the Guard, felt similar forebodings. ‘If we are beaten, what terrible risks will we not run! Can a single one of us expect to return to his native country?’ Captain von Linsingen, who had walked over to where his Westphalians were sleeping or sitting around campfires, wondered how many would be alive the following evening. ‘And suddenly I found myself hoping that this time too the Russians would decamp during the night,’ he noted in his diary. ‘But no, the sufferings of the past days had been too great, it was better to end it all. Let the battle begin, and our success will assure our salvation!’ Raymond de Fezensac put it more succinctly: ‘Both sides realised they had to win or perish: for us, a defeat meant total destruction, for them, it meant the loss of Moscow and the destruction of their main army, the only hope of Russia.’28

Such reflections were not lightened by the circumstances. There was no bolstering spirits with a shot of drink and a good pipe. They were in an arid place which had been trampled by two armies. ‘Not a blade of grass or of straw, not a tree; not a village that has not been looted inside out,’ noted Cesare de Laugier. ‘Impossible to find the slightest nourishment for the horses, to find anything for oneself to eat, or even to light a fire.’ The men settled down to a cheerless and cold night. ‘A miserable plateful of bread soup oiled with the stump of a tallow candle was all I had to eat on the eve of the big battle,’ recalled Lieutenant Heinrich Vossler of the Württemberg Chasseurs. ‘But in my famished condition even this revolting dish seemed quite appetising.’29

The Russians were more fortunate, as they had plenty of food, and looked forward to the next day with greater enthusiasm. ‘We all knew that the battle would be a terrible one, but we did not despair,’ recalled Lieutenant Nikolai Mitarevsky of the artillery. ‘My head was full of things remembered from books about war – the “Trojan War” in particular would not leave my thoughts. I was eager to take part in a great battle, to experience all the feelings of being in one, and to be able to say afterwards that I had been in such a battle.’ As they lay beside their campfires gazing up at the stars, they wondered about what it felt like to be dead.30

Several Russian officers were struck by the calm that descended on their camp that day, which was a Sunday, and by the almost spiritual manner in which the soldiers readied themselves for the battle. While the grenadiers of the Old Guard were taking heart from Gérard’s picture of the King of Rome, the Russians were seeking solace from a different image. Kutuzov had ordered the miraculous icon of the Virgin of Smolensk, which had followed the army on a gun carriage, to be taken around the Russian positions in procession. The procession, made up of Kutuzov and his staff and a body of monks with candles and incense, would pause at every regiment’s position, in every battery and every redoubt, and prayers would be said and hymns sung. ‘Placing myself next to the icon, I observed the soldiers who passed by piously,’ wrote one artillery officer. ‘O faith! How vital and wondrous is your force! I saw how soldiers, coming up to the picture of the Most Holy Virgin, unbuttoned their uniforms and taking from their crucifix or icon their last coin, handed it over as an offering for candles. I felt, as I looked at them, that we would not give way to the enemy on the field of battle; it seemed as though after praying for a while each of us gained new strength; the live fire in the eyes of all the men showed the conviction that with God’s help we would vanquish the enemy; each one went away as though inspired and ready for battle, ready to die for his motherland.’31

‘As for us,’ noted General Rapp as he watched from outside Napoleon’s tent while the procession wound its way round the Russian camp, ‘we had neither holy men nor preachers, nor indeed supplies; but we carried the heritage of years of glory; we were going to decide whether it would be the Tatars or us who gave laws to the world; we were at the confines of Asia, further than any European army had ever ventured. Success was not in question: that was why Napoleon watched Kutuzov’s processions with delight. “Good,” he said to me, “they are at their mummeries, they won’t escape me now.”’ He had already decided on an appropriately resonant name for the victory – ‘La Moskowa’, after the name of the river flowing nearby.32

‘Night fell,’ continued Rapp. ‘I was on duty, so I slept in Napoleon’s tent. The place in which he sleeps is usually separated by a canvas wall from that in which the duty aide-de-camp sleeps. This prince slept very little. I woke him several times to hand him reports that came in from the outposts, all of which confirmed that the Russians were preparing to receive an attack. At three o’clock in the morning he called for a valet and had some punch brought, which I had the honour of drinking with him.’ They chatted as they drank, and Napoleon mused that if he had been Alexander, he would have chosen Bennigsen rather than Kutuzov, who was a very passive commander. He asked Rapp what he thought of their chances for the coming day, and, when Rapp replied optimistically, went back to studying his papers. ‘Fortune is a fickle courtesan,’ Napoleon suddenly said. ‘I have always said so, and now I am beginning to experience it.’

Rapp did not like the tone of resignation in his master’s voice. ‘Your Majesty will remember that at Smolensk you did me the honour of telling me that the wine had been poured and it must be drunk. That is now the case more than ever; the moment for retreat has passed. The army is well aware of its position: it knows that it will only find supplies in Moscow, and that there are only thirty more leagues to go.’

‘Poor army, it is much reduced,’ interjected Napoleon, ‘but what is left is good; and my Guard is intact.’33