Napoleon was in the saddle by three o’clock in the morning, and rode over to the Shevardino redoubt. The troops were already moving up to their positions, cheering as they passed their Emperor. ‘It’s the enthusiasm of Austerlitz!’ Napoleon observed to Rapp. By half past five, all the units were in their designated positions, drawn up as if on parade. ‘Never has there been a finer force than the French army on that day,’ recalled Colonel Seruzier of the artillery of Montbrun’s Cavalry Corps, ‘and, despite all the privations it had suffered since Vilna, its turnout on that day was as smart as it ever was in Paris when it paraded for the Emperor at the Tuileries.’1 The commanding officers of every unit then read out a proclamation penned by Napoleon the night before:

Soldiers! This is the battle that you have looked forward to so much! Now victory depends on you: we need it. It will give us abundance, good winter quarters and a prompt return to our motherland! Conduct yourselves as you did at Austerlitz, at Friedland, at Vitebsk, at Smolensk, and may the most distant generations cite your conduct on this day with pride; let it be said of you: ‘He was at that great battle under the walls of Moscow!’2

‘This short and bold proclamation galvanised the army,’ according to Auguste Thirion. ‘In a few words it touched on all its concerns, all its passions, all its needs, it said it all.’ By alluding to the legendary battle it also reminded them who was in now command of the Russian army – the man they knew as ‘le fuyard d’Austerlitz’, the runner of Austerlitz. Napoleon never missed an opportunity to allude to his most famous victory, and when the sun broke through the morning mist, as it had on that glorious day, he turned to those around him and exclaimed: ‘Voila le soleil d’Austerlitz!’3

He had taken up position on the rise at the back of the Shevardino redoubt, from where he could see the entire battlefield. The Imperial Guard was drawn up alongside and behind him. He was brought a folding camp chair, which he turned back to front and sat astride, leaning his arms on its back. Behind him stood Berthier and Bessières, and behind them a swarm of aides-de-camp and duty officers. Before him he could see a formidable sight.

The reeds and bushes along the Kolocha were alive with Russian jaegers. Behind them, on the rising ground, were the Russian infantry and cavalry drawn up in massed ranks in front of the redoubts, on the parapets of which gleamed brightly polished bronze cannon. Behind the redoubts could be seen more massed bodies of men. Kutuzov had put all his cards on the table, probably in order to provoke Napoleon into concentrating on a frontal assault.

He had set up his command post in front of the village of Gorki. A cossack brought him his folding chair, and Kutuzov sat down on it heavily, dressed in his usual frock-coat and flat round white cap. He could not see the battlefield from where he was, but his mere presence was enough. ‘It was as though some kind of power emanated from the venerable commander, inspiring all those around him,’ in the words of Lieutenant Nikolai Mitarevsky. The fifteen-year-old Lieutenant Dushenkevich had been thrilled when the commander had driven past the bivouac of his Simbirsk Infantry regiment. ‘Boys, today it will fall on you to defend your native land; you must serve faithfully and truly to the last drop of blood,’ he had exhorted them. ‘I am counting on you. God will help us! Say your prayers!’4

At six o’clock, the French guns opened up, the Russians answered, and as nearly a thousand cannon spewed out their charges, to those present, even those who had been in battle before, it seemed as though all hell had been let loose. The sound brought a sense of relief to many. ‘There was great joy throughout the army when we heard the sound of the cannon,’ according to Sergeant Bourgogne of the Vélites of the Guard.5 He was lucky, as the Guard were out of range, and from where he stood he had a fine view of the bombardment. The battlefield was so compact that it was possible for most of the men to observe the action. The French guns pounded the Russian positions, particularly the earthworks, throwing up clouds of dust which mixed with the smoke from the defending guns to create the impression of a vast swirling sea. The Raevsky redoubt, whose eighteen guns were firing as fast as they could, looked like an erupting volcano to some of the spectators, and poetic comparisons were made with Vesuvius.

There was nothing poetic about the bombardment to those who had to endure it. Most of the troops, Russian and French, were positioned within range of the enemy’s guns, and they found themselves under fire as they waited to go into battle. There were three types of projectile raining down on them: ball, shell and canister. Ball shot was a solid iron ball weighing anything between three and twenty pounds. Shells consisted of a thick steel casing filled with explosive which was detonated by a fuse. The shell might explode after it had landed among the enemy ranks, or above their heads, in both cases scattering jagged fragments of the casing in all directions. Canister, also known as grape or case shot, was like a giant shotgun cartridge, which shot out of the cannon’s mouth in a hail of iron balls a couple of centimetres in diameter.

The old soldiers stood impassively as they watched the cannonballs fly through the air or bounce along the ground towards them. To lift their spirits, the Russians laughed at the militiamen, who tried to dodge the projectiles – old soldiers’ wisdom had it that there was no point, as each one had somebody’s name on it anyway. Veterans also had to remind recruits not to put out their foot to try to stop what seemed to be spent cannonballs as they rolled by, for the harmless-looking objects could still tear off a leg. The tension and the fear could be terrible as they watched men standing next to them cut in two. When the order was given to move off, the sense of relief was such that many soldiers experienced an urgent need to defecate, producing a comic rush to squat beside the columns as they lumbered forward.6

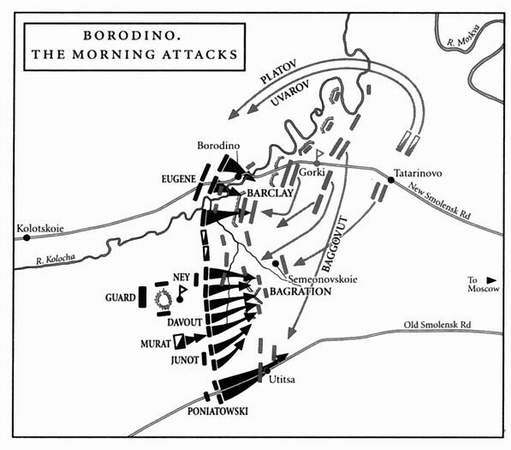

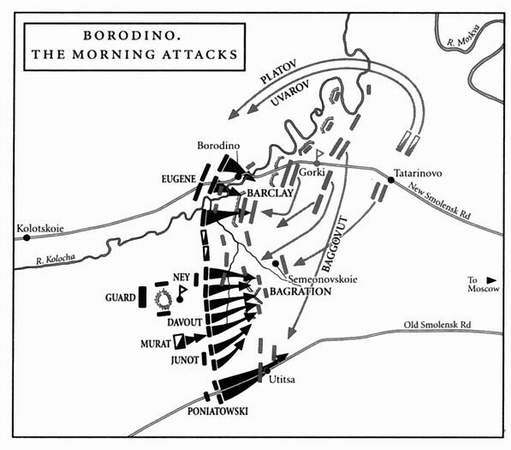

The Delzons division from Prince Eugène’s corps, made up of French and Croat infantry, opened the action by sweeping away the advanced Life Guard jaegers, who lost half of their men in the short action, and occupying the village of Borodino. Two more of Eugène’s divisions crossed the Kolocha, pushing back the Russian infantry with shouts of ‘Viva Italia!’ coming from the Tuscans and the Piedmontese as well as ‘Vive l’Empereur!’, but they got so carried away that they were caught in a counterattack and thrown back across the river. They then began to prepare a fresh attack.

Meanwhile, Davout had launched two divisions on the southernmost of Bagration’s flèches, which had been subjected to half an hour’s softening up by artillery bombardment. General Compans was wounded as he led his division towards the earthwork, but his men nevertheless occupied it and General Desaix led his division up in support. Further south, Poniatowski pushed back Tuchkov’s division and occupied the village of Utitsa.

A Russian counterattack soon expelled the French from the southern flèche. But a second French assault was mounted, with General Rapp now leading the Compans division, supported by Desaix and Junot, while General Ledru’s division from Ney’s corps attacked the next one along. Both earthworks were taken after fierce hand-to-hand fighting, in which both Rapp and Desaix fell, and in which Prince M.S. Vorontsov, commanding the Grenadier division which held them, was himself wounded. ‘Resistance could not be long,’ he explained, ‘but it only came to an end, so to speak, with the existence of my division.’7 By eight o’clock he and his division were out of action, having lost 3700 of its four thousand men and all but three of its officers in the space of two hours.

The flèches were in fact traps for the victors. They were no more than V-shaped earthworks, open at the back, so once the French had taken them, they found themselves having to face the next line of Russians while stuck in a funnel with a wall at their backs. And it was only after they had taken the second flèche that they realised there was a third. While the Russian guns poured a murderous fire into the confused ranks of the French, General Neverovsky mounted a counterattack that expelled them from the earthworks once again. Undeterred, the French rallied for a new assault.

Over the next three hours, these earthworks were to be stormed, captured and retaken no fewer than seven times as both sides poured reinforcements into the fray. At seven o’clock Kutuzov had three Guards regiments, three cuirassier regiments, eight battalions of grenadiers and thirty-six guns moved from his reserves to support Bagration. An hour later he sent another hundred guns and, shortly afterwards, a brigade of infantry. At nine o’clock he sent in General Miloradovich with the 4th Infantry and 2nd Cavalry corps. Thus the 18,000 men originally dedicated to the defence of this sector rose to over 30,000, supported by three hundred guns. On the French side, Davout’s corps was joined by Ney’s, Junot’s and part of Murat’s, bringing some 40,000 men and over two hundred guns to bear. The fighting was so intense that the infantry had no time to reload their muskets, which had by now become fouled with powder anyway, and the bayonet became their principal weapon. But the air was thick with canister shot flying in both directions. ‘I had never seen such carnage before,’ noted Rapp.8

Each time the French were evicted from the flèches, they would reform and launch another assault. Their bearing and discipline were so magnificent that Bagration applauded, shouting ‘Bravo!’ as the columns advanced towards his positions for the fourth or fifth time. Ney, who complained bitterly about being made to ‘take the bull by the horns’, was in the forefront, clearly visible on his white horse. Davout, who had been wounded and carried off the field during the first attack, was back in the saddle, encouraging his men. Murat was everywhere, drawing eyes and bullets by his theatrical costume. The attacks and counterattacks succeeded each other like a tidal ebb and flow which left thousands strewn across the field at every turn. This dogged slogging-match over a line of earthworks and the carnage it involved were entirely novel elements in European warfare, in which outnumbered or outmanoeuvred units had hitherto tended to fall back rather than fight to the last drop of blood.

At about ten o’clock the French had once again captured all three flèches, but Bagration rallied his troops for one final effort and led them into the attack once more. It was successful, but at the moment of triumph Bagration was hit in the leg. He tried to carry on as though nothing had happened, but he had no strength in his shattered leg and after a moment slid from his horse. He wanted to remain on the scene, but was carried away, still protesting. Barclay’s aide-de-camp Löwenstern spotted him and came over. ‘Tell the General that the fate of the army and its preservation is in his hands,’ Bagration said, in a belated, grudging admission of respect for Barclay’s competence. ‘So far all is going well, but let him look after my army, and may God help us all.’9

News quickly spread among the Russian troops that their beloved commander had been killed, and although Konovnitsin tried to steady them, they could not resist the next French assault, which finally cleared them from the flèches and pushed them back across the ravine of the Semeonovka all the way to the ruins of the village of Semeonovskoie, whose houses were collapsing ‘like theatrical stage-sets’ under the French artillery’s bombardment. ‘There are no words to describe the bitter despair with which our soldiers threw themselves into the fray,’ wrote Captain Lubenkov. ‘It was a fight between ferocious tigers, not men, and once both sides had determined to win or die where they stood, they did not stop fighting when their muskets broke, but carried on, using butts and swords in terrible hand-to-hand combat, and the killing went on for about half an hour.’10

Semeonovskoie was in French hands. Ney and Murat, who could see into the rear of the entire Russian army through the gap they had created, glimpsed victory lying within their grasp, but they could not forge ahead and seize it with the tattered units at their disposal. They sent urgent requests to Napoleon for reinforcements.11

But Napoleon did not respond. Although he had a good view of the whole battlefield, from where he sat he could not make out clearly what was really happening on the ground, and he did not, as usual, mount his horse to take a look. He sat very still most of the time, showing little emotion, even when listening to the reports of panting officers who, without dismounting, retailed news from the front line. He would dismiss them without a word, and then go back to surveying the battlefield through his telescope. He had a glass of punch at ten o’clock, but brusquely refused all offers of food. He seemed very absorbed, but his concentration did not yield any results.

‘Previously it was above all on the battlefield that his talents had shone with the greatest éclat; it was there that he seemed to master fortune herself,’ wrote Georges de Chambray, who could not recognise in the tired old man of that day the god of war who had galloped about the field of so many battles, spotting the right moment and the weak point at which to launch the decisive attack.

Many observed that Napoleon was not his usual active self that day. ‘We did not have the pleasure of seeing him, as in the old days, go to electrify with his presence those points where a too vigorous resistance was prolonging the fighting and called success into question,’ Louis Lejeune, an officer on Berthier’s staff, noted in his diary that evening. ‘We were all surprised not to see the active man of Marengo, Austerlitz, etc. We did not know that Napoleon was ill, and that this state of discomfort rendered it impossible for him to take an active part in the great events taking place before him, exclusively for the sake of his glory.’ People from all over Europe and half of Asia were fighting under his gaze, the blood of 80,000 French and Russian troops was flowing in a struggle to affirm or destroy his power, and all he did was sit and watch calmly, Lejeune reflected. ‘We did not feel satisfied; our judgements were severe.’12

There was, as Davout complained to one staff officer, no unified superior direction to the operations. While Ney and Davout were engaged in their battle over the flèches, Napoleon had launched further attacks against the Russian centre in the Raevsky redoubt. The first, by two of Eugène’s infantry divisions, was repulsed, but a second, by Morand’s division, would prove more successful. It was a fine display of French military prowess.

Captain François of the 30th of the Line was leading his company straight at the redoubt while salvoes from the Russian guns raked the attackers. ‘Nothing could stop us,’ he remembered. ‘We hopped over the roundshot as it bounded through the grass. Whole files and half-platoons fell, leaving great gaps. General Bonamy, who was at the head of the 30th, made us halt in a hail of canister shot in order to rally us, and we then went forward at the pas de charge. A line of Russian troops tried to halt us, but we delivered a regimental volley at thirty paces and walked over them. We then hurled ourselves at the redoubt and climbed in by the embrasures; I myself got in through an embrasure just after its cannon had fired. The Russian gunners tried to beat us back with ramrods and levering spikes. We fought hand-to-hand with them, and they were formidable adversaries.’13

Raevsky, who had been wounded in the leg in an accident a few days before, just managed to hobble away, but the remainder of the redoubt’s defenders were cut down, including General Kutaisov, the able and popular commander of the whole Russian artillery. The French infantry then spilled out into the area behind the redoubt. As Raevsky himself pointed out, if Morand had been properly supported, that would have been the end of the Russian centre, and the battle would have been over by ten o’clock in the morning.14 That it was not owed nothing to the Russian command.

Kutuzov had realised as early as seven o’clock that he must reinforce his left wing, and had begun a progressive transfer of units from his reserves and his idle right wing to the southern sector. A couple of divisions under Baggovut had been sent to reinforce Tuchkov, who was the only thing standing between Poniatowski and the Russian rear. Baggovut took over from Tuchkov, who had been mortally wounded, and stabilised the situation by forcing Poniatowski to fall back a small distance. A number of reinforcements had also been despatched to plug the holes in Bagration’s defences as the French knocked more and more of his units out at the flèches.

None of this was part of a coherent strategy – Kutuzov was simply reacting to appeals for help and alarming reports. A staff officer would gallop up with some unit commander’s request or suggestion, and Kutuzov would wave his hand and say: ‘C’est bon, faites-le!’ Sometimes he would turn to Toll and ask him what he thought, adding: ‘Karl, whatever you say I will do.’ According to Clausewitz, the old General contributed nothing to the proceedings. ‘He appeared destitute of inward activity, of any clear view of surrounding occurrences, of any liveliness of perception, or independence of action,’ he wrote. It never occurred to Kutuzov that, Kutaisov having been killed, someone should take over directing the artillery, and as a result the reserve park stood idle all day and the Russian superiority in this arm was never brought into play.15

On hearing of Bagration’s wound, Kutuzov sent Prince Eugene of Württemberg to the fléches. The Prince tried to stabilise the situation around Semeonovskoie by pulling back a short distance, but Kutuzov would not accept this and heaped insults on him. Yet when Dokhturov, whom he sent to take over, asked for reinforcements, the request was denied, only to be granted later. Kutuzov did at one stage mount his white horse and ride out to have a look at what was going on, but soon returned to Gorki. Later, he seems to have taken up a position even further back, where according to one staff officer he did justice to a fine picnic, assisted by his entourage of elegant officers from the best families. Luckily for him, Bennigsen and Toll kept visiting the battlefield, and a number of his subordinates showed remarkable initiative. At the same time everyone was acting on his own, and there was a great deal of mistrust. When Bagration sent an officer to Konovnitsin with an order, the latter kept the officer as a hostage, suspecting a trick on Bagration’s part.16 In the final analysis what saved Kutuzov’s reputation that day was the stoicism of the Russian soldier, who fought and died – often pointlessly – where he had been ordered to.

When the French occupied the Raevsky redoubt, the situation was saved by a combination of lucky flukes. Barclay had gone to Gorki, but General Löwenstern took the situation in at once, galloped up to a battalion of infantry standing by, and swept it up into a counterattack. At the same time Yermolov, who happened to be riding by with reinforcements for the southern sector, also saw the peril, and on his own initiative deployed them against the French in the redoubt. General Bonamy and his 30th Regiment were thus caught in a counterattack from two quarters, while the troops holding the line on either side of the breach also began to close in. The French infantry retreated into the redoubt and brought a few guns to bear, but without support from their side they could not hold it, and the Russians swarmed in, taking Bonamy prisoner. Only eleven officers and 257 other ranks of the 30th of the Line, which had numbered 4100 men that morning, managed to scurry down the hill to the safety of their own lines.17

It was shortly after the unfortunate Bonamy, weakened by his fifteen wounds, had been brought to Kutuzov that Toll came up to the commander with a request from General Platov. Platov with his 5500 cossacks and Uvarov with 2500 regular horse had been sitting idly on the right wing, and they requested to be allowed to cross the Kolocha and make a raid into the French rear. Kutuzov gave his assent to the suggestion without seemingly giving it much thought, and soon the eight thousand riders with their thirty-six guns were fording the Kolocha. They wreaked predictable havoc in the rear of Prince Eugène’s corps, panicking the Delzons division into flight. But they were soon stopped in their tracks when the French infantry formed squares and fired off a few salvoes of grapeshot in their direction. The cossacks darted out of range, while the regular cavalry fled in disorder, pursued by French dragoons. Platov and Uvarov were given a cool greeting by Kutuzov on their return. As several Russian officers pointed out, the raid had been devoid of any tactical sense, as it could have yielded little but exposed the cavalry to serious loss.18 But it did have some unexpected consequences.

Between eleven and twelve o’clock the French attacks had ground to a standstill, in spite of a number of local victories. In the centre, the Raevsky redoubt was back in Russian hands; further along, the Bagration fléches and then the village of Semeonovskoie had been taken; but new Russian lines of defence sprang up every time, and on the extreme right wing Poniatowski’s attack had been halted. None of the forces engaged in these actions was strong enough to push the advantage home, and that was why Ney, Murat and Davout repeatedly called for reinforcements.

This would have meant sending in the Imperial Guard. Napoleon was loath to commit this, as it constituted his last and surest reserve, not something he wanted to gamble with so far from home. But he was, apparently, prepared to commit part of it. He sent the artillery of the Guard forward to bombard the Russian positions around Semeonovskoie, and ordered the Young Guard, under General Roguet, to move forward.

But at the very moment when he was preparing to throw this force into the scales, Platov and Uvarov appeared on his left flank, and he halted everything while he reassessed the situation.19 Thus at the most critical moment, when the Russian defences had been breached, Napoleon virtually called a halt. Over the next two hours the French armies did not move, and this gave the Russians valuable time to patch their defences and bring up reserves.

But while the fighting subsided, the cannonade did not, and since most of the troops were massed within range of the enemy’s guns the carnage continued. The most vulnerable were the massed ranks of Murat’s cavalry, which had been positioned in the centre, under the guns of the Raevsky redoubt.

Roth von Schreckenstein of the Saxon cavalry pointed out that to be made to stand still under fire ‘must be one of the most unpleasant things cavalry can be called on to do … There can have been scarcely a man in those ranks and files whose neighbour did not crash to earth with his horse, or die from terrible wounds while screaming for help.’ Jean Bréaut des Marlots, a captain of cuirassiers, rode down the line of his squadron to keep his men steady under the withering fire. He congratulated one of his subalterns, by the name of Grammont, on his bearing. ‘Just as he was telling me that he lacked for nothing, except perhaps a glass of water, a cannonball tore him in two,’ wrote the Captain. ‘I turned to another officer to tell him how sorry I was to have lost this M. de Grammont. But before he could answer me, his horse was hit by a cannonball which killed him. And a hundred other incidents of this sort. I gave my horse to a trooper to hold for half a minute, and the man was promptly killed.’ The inaction was unbearable, and the young Captain could only stop himself from running away, as he explained in a letter to his sister Manette, by telling himself: ‘It’s a lottery, and if you do survive it you will still have to die; and would it be better to live dishonoured or to die with honour?’20

Auguste Thirion, another cuirassier, experienced similar emotions. ‘In a charge, which in any case never lasts very long, everyone is excited, everyone slashes and parries if he can; there is action, movement, man-to-man combat; but here our position was quite different. Standing still opposite the Russian cannons, we could see them being loaded with the projectiles which they would direct at us, we could distinguish the eye of the gunner who was aiming at us, and it required a certain dose of sang-froid to remain still.’ One of his men lost his nerve and was about to run, so Thirion comforted him and offered to share a small crust of bread he had been saving. But at the moment he took it out of his pocket the man was hit in the head by a ball. Thirion brushed the brains from his crust, and ate it himself.21

One cannot be surprised at such apparent callousness. All the officers and men were undernourished and ravenously hungry. They suffered cruelly from thirst, as the tension and the smoke dried their throats. They were surrounded by death. Many of them were unwell, and the length of the battle magnified every kind of discomfort. ‘At Dorogobuzh I again fell victim to the terrible diarrhoea which had afflicted me so cruelly at Smolensk, and in the course of this day I endured the most awful agony imaginable, as I was unable to quit my post or dismount,’ wrote Lieutenant Louis Planat de la Faye, aide-de-camp to General Lariboisière. ‘I will not describe exactly how I managed to dispose of that which was tormenting me, suffice it to say that in the process I lost two kerchiefs which I disposed of as discreetly as I could by throwing them into the trench of the earthworks we passed.’22

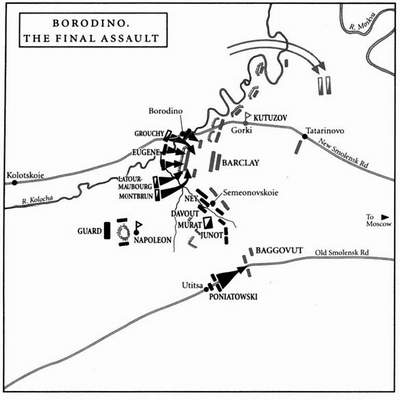

It was not until shortly after two o’clock in the afternoon that the French began massing for a general assault on the Raevsky redoubt. As some two hundred cannon pounded the earthwork and the gunners inside, Prince Eugène drew up three divisions of infantry – Gérard’s, Broussier’s, and Morand’s from Ney’s corps. Shortly before three o’clock the dense columns of French infantry, a great sea of blue but for the white uniforms of a battalion of Spaniards from the Joseph Napoleon regiment, lumbered forward up the incline. They were joined by two masses of heavy cavalry moving up on either side, Grouchy’s 3rd Corps on the left, Latour-Maubourg’s 4th and Montbrun’s 2nd (now under the command of General Auguste de Caulaincourt, younger brother of the diplomat) on the right. These two, moving at a trot, overtook the advancing columns of infantry and made for the left flank of the redoubt and the area in its rear.

To Colonel Franz von Meerheimb of the Saxon Zastrow regiment, the handsome Latour-Maubourg looked absurdly boyish in his resplendent uniform, and far too young to lead the mass of horsemen. But as they approached the redoubt he drew them into a charge with great aplomb and, sweeping round the earthworks, they poured into it, some through the openings at the rear, some over the ditches already filled with French and Russian corpses and the pulverised earthen parapets strewn with debris. The first in were the Saxons and Poles of General Lorge’s cuirassier division, followed by Caulaincourt’s cuirassiers, whose gallant young leader fell dead as he rode up to the redoubt. When they came over the breastworks, the horsemen were met by a volley of musketry and plunged into a mass of bayonets. As they fell dead or wounded, their comrades followed, trampling over a writhing mass of wounded men and horses, and the defenders struggled in vain to keep them out.23

Colonel Griois of Grouchy’s artillery, watching the scene from the rear, could hardly contain himself when he saw the glinting helmets of the cuirassiers inside the redoubt. ‘It would be difficult to convey our feelings as we watched this brilliant feat of arms, perhaps without equal in the military annals of nations. Every one of us accompanied with his wishes and would have liked to give a helping hand to that cavalry which we saw leaping over ditches and scrambling up ramparts under a hail of canister shot, and a roar of joy resounded on all sides as they became masters of the redoubt.’24

‘Inside the redoubt, horsemen and footsoldiers, gripped by a frenzy of slaughter, were butchering each other without any semblance of order,’ wrote Meerheimb.25 As the horsemen hacked away at the infantry and gunners defending the redoubt, the French infantry poured over the breastworks, and all resistance was quickly extinguished. It was half past three. Grouchy’s cavalry had swept into the area behind the redoubt, where they were followed by other French units, only to find that Barclay had formed up a second line of defence, about eight hundred metres behind the redoubt. The cavalry found itself powerless against the Russian infantry, which had formed squares.

Barclay himself was directing the defence of this sector, cool and collected as always, appearing to one staff officer like a beacon in a storm. But he was also displaying a recklessness which suggested to some that he was seeking a glorious death. He had ordered up his cavalry reserve, only to discover that Kutuzov had sent it elsewhere without informing him. He was nevertheless able to muster enough cavalry to launch a counter-charge, and the whole area was soon a swirling mêlée of horsemen, thrusting and hacking at each other at close quarters. The French fell back to the line of the redoubt, and Barclay’s artillery kept them from venturing forth again as it raked the area in front.26

According to Clausewitz, the battle was now ‘on its last legs’ as far as the Russians were concerned, and all that was needed for complete victory was for the French to deliver the coup de grâce.27 But none came. The cannonade continued, the cavalry of both sides clashed once more in the centre, and in the south Poniatowski made one final thrust, pushing the Russians back beyond Utitsa. The sky had become overcast and a cold drizzle started to fall. At about six o’clock the guns fell silent as the Russians withdrew about a kilometre. Napoleon painfully mounted his horse and set off to survey the results.

He rode down the slope from which he had been watching the action all day. At the bottom he found the ground covered in spent musket-balls and grapeshot lying as thick as hailstones after a storm. As his horse picked its way between the debris of men, horses and equipment, he saw what one general called ‘the most disgusting sight’ he had ever seen. Since most of the carnage had been performed by artillery fire, the ground was covered in mangled corpses with exposed entrails and severed limbs. Wounded men struggled to free themselves from under dead men and horses, or dragged themselves in the direction of some perceived succour. Wounded horses crushed them as they themselves attempted to get to their feet. ‘One could see some which, horribly disembowelled, nevertheless kept standing, their heads hung low, drenching the soil with their blood, or, hobbling painfully in search of some pasture, dragged beneath them shreds of harness, sagging intestines or a fractured member, or else, lying flat on their sides, lifted their heads from time to time to gaze on their gaping wounds,’ recalled an appalled Belgian lancer.28

The Raevsky redoubt presented a gruesome sight. ‘The redoubt and the area around it offered an aspect which exceeded the worst horrors one could ever dream of,’ according to an officer of the Legion of the Vistula, which had come up in support of the attacking force. ‘The approaches, the ditches and the earthwork itself had disappeared under a mound of dead and dying, of an average depth of six to eight men, heaped one upon the other.’ Inside, the Russian defenders, who had died in their ranks, looked as though they had been scythed down.29

The Russian wounded lay stoically waiting for death or tried to drag themselves free, the French called for help or implored to be put out of their agony with a bullet. ‘They lay one on top of the other, swimming in pools of their own blood, moaning and cursing as they begged for death,’ according to Captain von Kurz. Some were able to drag themselves along the ground, hoping to find help or at least a drink of water. ‘Others just sought to get away, hoping to escape death by fleeing from the place where she reigned in all her horror,’ in the words of Raymond Faure, the doctor attached to the 1st Cavalry Corps.30

Single soldiers wandered about rifling through the haversacks and pouches of the dead in search of a crust of bread or a drop of liquor. Others stood or sat, grouped in their units, dazed and uncertain of what to do next. ‘Around the eagles one could see the remaining officers and non-commissioned officers along with a few soldiers, hardly enough to guard the flag,’ recalled the Comte de Ségur. ‘Their uniforms were torn by the ferocity of the struggle, blackened by powder and sullied with blood; and yet, in the midst of these tatters, of this misery, of this disaster, they maintained a proud look and even managed, at the sight of the Emperor, a few cheers; but they were rare and contrived, for in that army, which was capable of clear-sightedness as well as enthusiasm, each one was assessing the overall position.’ Officers and men were struck by how few prisoners had been taken, and they knew that it was by the number of prisoners, guns and standards captured that one could gauge the scale of a victory. ‘The number of dead testified to the courage of the vanquished rather than to the scale of the victory.’31

Napoleon rode back to his tent, which had been brought forward and pitched on the battlefield near the spot from which he had commanded. He wrote to Marie-Louise telling her he had beaten the Russians and sent instructions to the bishops of France to sing Te Deums in thanks for the victory. He was joined for dinner by Berthier and Davout, but he ate little and looked ill. They all agreed that they had won a decisive victory, but there was none of the usual sense of elation. Napoleon spent a sleepless night, according to his valet Constant, who heard him sigh, ‘Quelle journée! Quelle journée!’32

There were no songs around the bivouacs that night, no enthusiastic exchange of experiences and tales of glory. The men settled down where the end of the action had found them, huddling round fires made out of broken musket stocks and gunlimbers, piling corpses one on top of the other to sit on. It was the third day they had received no food, and whatever private supplies they had, as well as the cantinières, were behind in the bivouacs of the previous night. They had to make do with whatever they could scavenge, making gruel with the buckwheat found in the knapsacks of the Russian dead, with water from one of the streams criss-crossing the battlefield, already thick with blood. One who ate better than most was a voltigeur who had managed to shoot a hare which found itself in the path of his advance at the beginning of the battle, and which he now skinned and cooked. As the men sat around their mean fires, wounded comrades came crawling or dragging themselves towards them, begging to be allowed to share their meagre rations. The Russian wounded had to content themselves with chewing on the carcase of some dead horse. ‘The night of [7 September] was terrible,’ in the words of an officer of the Grenadiers of the Old Guard. ‘We spent it in the mud, without fires, surrounded by dead and wounded, whose plaintive cries broke one’s heart.’33

The wounded had been evacuated from the field of battle during the fighting by special details of soldiers with stretchers – and also by malingerers who would take the opportunity of carrying back a wounded comrade in the hope of then hanging about the dressing station and avoiding a return to the front line. But when night fell the evacuation of the wounded ceased, because of the dark and also because the dressing stations were swamped.

As most of them had been inflicted by cannon or musket at extremely close range, there were unusually few light wounds of the sort that could be dressed – a straightforward procedure which involved washing the wound, strapping on a piece of lint, binding it up and letting nature take its course. There was a severe shortage of surgeons, particularly on the French side, as so many had been left in hospitals along the way. Those remaining had been busy all day, carrying out operations and amputations in improvised conditions, washing their hands and instruments, as Dr Heinrich Roos remembered, in a nearby stream. Due to the shortage of draught animals, the ambulances and much of the medical equipment had been left behind in Vilna. When they ran out of bandages they had to tear up the shirts of the wounded.

As they had so little time to spend on each man, the simplest treatment for any wound to an arm or a leg was to amputate. The men were tied or held down on a table, given a lead bullet or a piece of wood or leather to bite on, and, if they were lucky, a shot of spirits to drink. Some struggled and screamed, cursing fate or calling their mothers, but many showed unimaginable stoicism. After the operation they would be set down on the ground, where they lay untended while the severed limbs piled up.

The surgeons continued to work through the night by the light of flickering candles. It was extremely hard work, and emotionally draining, even for such an experienced medic as Dr La Flise. ‘It is impossible to imagine what a wounded man feels when the surgeon has to inform him that he will certainly die unless one or two limbs are removed,’ he wrote. ‘He has to come to terms with his lot and prepare himself for terrible suffering. I cannot describe the howls and the grinding of teeth produced by a man whose limb has been shattered by a cannonball, the screams of pain as the surgeon cuts through the skin, slices through the muscles, then the nerves, saws right through the bone, severing arteries from which blood spatters the surgeon himself.’34

As the surgeons could not attend to them immediately, many of the wounded were taken straight to ‘hospitals’ improvised in the Kolotskoie monastery and whatever houses had remained intact in the village of Borodino. But since the cavalry had consumed all the straw for miles around, they lay on the bare ground. Some of them did not have their wounds dressed for days. ‘Eight or ten days after the battle three-quarters of these unfortunates were dead, from lack of attention and food,’ wrote Captain François, who was dumped along with 10,000 others in the Kolotskoie monastery, where he only survived because his servant cleaned his wound and brought him food and water.35

The more fortunate Russian wounded were evacuated to Moscow, but most never made it further than Mozhaisk, where they were packed into any available building and abandoned. When the French marched in two days later they found half of them dead from hunger or lack of water. The streets of the little town were full of corpses and heaps of amputated limbs, some of them still clad with gloves or boots.36

Ironically, spirits on the evening after the battle were higher on the Russian side than on the French. The fact that they had actually stood up to Napoleon and not fled before him gave the soldiers a sense of triumph. ‘Everyone was still in such a rapturous state of mind, they were all such recent witnesses of the bravery of our troops, that the thought of failure, or even only partial failure, would not enter our minds,’ recalled Prince Piotr Viazemsky, adding that nobody felt they had been vanquished. They knew the French had won, but they did not feel they had been beaten.37

Although the Russian front line had been withdrawn that evening some two kilometres back from its positions of the morning, the French did not follow it, and as soon as night fell cossacks, singly or in groups, ranged over the battlefield in search of booty (one party managed to kill two Russian officers who were having a conversation in French). The French did not post forward pickets or fortify their line, as, having beaten and pushed back the Russians, they felt no need to do so. They just camped where they were. For obvious reasons, nobody bedded down in the charnel house of the Raevsky redoubt, and this permitted a small party of Russian troops to ‘reoccupy’ it briefly.38

Ever aware of the power of propaganda, Kutuzov determined to claim victory for himself. When Colonel Ludwig von Wolzogen, one of Barclay’s staff officers, delivered his report on the situation on the front line at the cease of fighting, from which it was evident that the Russians had been forced to abandon all their positions and had suffered crippling losses, Kutuzov rounded on him. ‘Where did you invent such nonsense?’ he spluttered. ‘You must have spent all day getting drunk with some filthy bitch of a suttler-woman! I know better than you do how the battle went! The enemy attacks have been repulsed at every point, and tomorrow I shall place myself at the head of the army and we shall chase him off the holy soil of Russia.’39

He ordered preparations to be made for a general attack in the morning. ‘From all the movements of the enemy I can see that he has been weakened no less than us during this battle, and that is why, having started with him, I have decided this night to draw up the army in order, to supply the artillery with fresh ammunition, and in the morning to renew the battle with the enemy,’ he wrote to Barclay. The news that the battle was to continue on the morrow was received with joy by the rank and file, and the men settled down to rest in an orderly fashion.40

Meanwhile, Toll and Kutuzov’s aide-de-camp Aleksandr Borisovich Galitzine carried out a tour of inspection of the whole army, and came back to inform the commander that he would only be able to muster a maximum of 45,000 men for battle in the morning. ‘Kutuzov knew all this, but he waited for this report, and it was only after listening to it that he gave the order to retreat,’ according to Galitzine, who was convinced that the commander had never intended to give battle on the following day, and only said he would ‘for political reasons’.41

This is highly likely. On the one hand, it would help present the battle as a victory to the outside world, which Kutuzov immediately set about doing. He wrote a long letter to Alexander describing the course of the action, stressing the bravery and tenacity of the Russian troops, declaring that he had inflicted heavy losses on the French and not given an inch of ground. But, he continued, as the position at Borodino was too extended for the number of men at his disposal, and since he was more interested in destroying the French army than merely winning battles, he was going to pull back six versts to Mozhaisk. He wrote a similar letter to Rostopchin, assuring him that he would make a stand there. He also issued a public bulletin describing the battle, saying all French attacks had been unsuccessful. ‘Repulsed at all points, the enemy fell back at nightfall, and we remained masters of the battlefield. On the following day General Platov was sent out in pursuit and chased his rearguard to a distance of eleven versts from Borodino.’ ‘I won a battle against Bonaparte,’ he wrote, more succinctly, to his wife.42

The announcement about fighting the following day might also have been a ploy designed to forestall a rout. It would prevent anyone from anticipating a retreat, and therefore keep the units together. Also, as none of the officers and men knew the overall position, such news would lead them to assume that the army was in better shape than it actually was. Kutuzov’s bluster and confidence certainly had their effect, and, as Clausewitz pointed out, ‘this mountebankism of the old fox was more useful at this moment than Barclay’s honesty’.43 Had the Russians known the full extent of their losses, they might well have given way to despair.

It had been the greatest massacre in recorded history, not to be surpassed until the first day of the Somme in 1916. One does not have to look far to see why. Two huge armies had been massed in a very small area. According to one source, the French artillery fired off 91,000 rounds. According to another they fired only 60,000, while the infantry and cavalry discharged 1,400,000 musket-shots, but even that averages out at a hundred cannon shots and 2300 rounds of musketry per minute.44

The Russians had drawn up their troops in depth, so that a hundred paces or so behind each line there was another line. This undoubtedly saved the day for them, as every time the French broke through they would come up against a fresh wall of troops and therefore fail to achieve a decisive breakthrough. But it did mean that the entire Russian army, including the units being held in reserve, was within range of the French guns throughout the day. Prince Eugene of Württemberg, for instance, recorded that one of his brigades lost 289 men, or nearly 10 per cent of its effectives, in half an hour while standing at ease in reserve.45

For no such good reason, Napoleon also stationed many of his reserves, and almost all of his cavalry, within range of the enemy guns. Captain Hubert Biot’s 11th Chasseurs à Cheval stood under fire for hours, and lost one-third of its men and horses without taking part in any fighting. One regiment of Württemberg cavalry lost twenty-eight officers and 290 men out of 762, over 40 per cent of its complement.46

Calculations of Russian casualties vary from 38,500 to 58,000, but most recent estimates put the figure at around 45,000, including twenty-nine generals, six of them killed, among them Bagration, who died of his leg wound, Tuchkov and Kutaisov. But if Kutuzov’s assertion that he would only be able to muster 45,000 for battle the next day is true, then the losses must have been much higher. French casualties came to 28,000, including forty-eight generals, eleven of whom died. In the spring of 1813, the Russian authorities clearing the field would bury 35,478 horse carcases.47

The Russian losses were crippling. The army had not only lost a vast number of men, it had actually lost half of its fighting effectives – the dead and wounded were overwhelmingly from the frontline regiments, not militia or cossacks. A very high proportion of the dead were senior officers. The result was that entire units had been rendered inoperational. The 1300-strong Shirvansk regiment was down to ninety-six men and three junior officers by three o’clock. Of Vorontsov’s division of four thousand men and eighteen senior officers, only three hundred men and three officers answered roll call that evening. Neverovsky’s entire division could muster no more than seven hundred men. Its 50th Jaeger Regiment was down to forty men, in the Odessa Regiment the senior officer left alive was a lieutenant, in the Tarnopol Regiment a sergeant major. ‘My division has all but ceased to exist,’ Neverovsky wrote to his wife the next day.48

The French losses were lighter by comparison, with most units losing no more than 10 to 20 per cent of their strength, and while a number of fine generals and senior officers had perished, the system of promotion meant that there would be no difficulty in replacing them. There were fresh troops on their way from Paris, so there would be no major problem in filling the gaps in the ranks. Yet the French army’s losses were far more important strategically than those of the Russians, for Napoleon had all but destroyed his cavalry.

Kutuzov’s army was in no condition to give battle on any positions, however strong. Unless it was given several weeks’ rest and massive reinforcement it would cease to exist altogether. As it could not possibly hope to defend Moscow, whatever Kutuzov may have written, the logical thing for him to do would have been to veer southward and withdraw towards Kaluga. Such a move would have brought him close to his supply base and forced the French to follow him, thus luring them away from Moscow. But if he did this, he would have to fight again or keep retreating, and in either case the remains of his army would disintegrate. More than anything else, he needed to get Napoleon off his tail, and he could only do that by distracting him with something else. In the only brilliant decision he made during the whole campaign, Kutuzov resolved to sacrifice Moscow in order to save his army. ‘Napoleon is like a torrent which we are still too weak to stem,’ he explained to Toll. ‘Moscow is the sponge which will suck him in.’49

He therefore fell back on Moscow, announcing that he would fight at Mozhaisk, and then at a point closer to the city. Although the retreat was disorderly, the numb resignation which had settled on the troops after the exaltation of battle kept them from dispersing or deserting in large numbers. One of the horses in Nikolai Mitarevsky’s gun team had had its lower jaw shot off by a shell fragment, so the gunners took it out of the traces and let it go, but the animal, which had been with the battery for ten years, merely followed it. Similar instincts inspired many a soldier. On the afternoon of 9 September the retreating units began taking up defensive positions on some heights just outside Moscow. They spent the next day digging in and preparing for battle, and Kutuzov wrote to Rostopchin, affirming that his army was in good shape and ready to repulse the French.50

Rostopchin had prepared Moscow for any eventuality, as he explained in a letter to Balashov on 10 September. He and tens of thousands of the inhabitants were ready to reinforce the army in a stand outside the city walls. ‘The people of Moscow and its environs will fight with desperation in the event of our army drawing near,’ he wrote to Balashov. Following assurances from Kutuzov, he had just declared that the city would be defended ‘to the last drop of blood’. In one of his proclamations to the citizens he assured them that they could use pitchforks on the French, who were so puny that they weighed less than a bale of hay. To all who doubted his determination, he would declare his readiness to defeat the French with a hail of stones if necessary.51

On 13 September, Kutuzov set up headquarters in the village of Fili and gave all the appearances of intending to defend the position he had selected. He asked Yermolov, in front of several generals, what he thought of the position, and when Yermolov replied that he felt it was not very good, enacted a charade of taking his pulse and asking if he was quite well. But Rostopchin, who had driven out from Moscow at Kutuzov’s request, was struck by the atmosphere of uncertainty he found at headquarters. He reported that he had evacuated the city, which could, if necessary, be abandoned to the enemy and then fired, but everyone seemed outraged at the idea of not defending Moscow. It was as though nobody dared admit the unpalatable truth. The only exception was Barclay, who was convinced that a battle fought at the gates of the city would destroy what was left of the army. ‘If they carry out the foolishness of fighting on this spot,’ he told Rostopchin, ‘all I can hope for is that I shall be killed.’52

Rostopchin was by now convinced that there would be no attempt to defend Moscow. But Kutuzov assured him of the contrary, in the course of what Rostopchin termed ‘a curious conversation which reveals all the baseness, the incompetence and the poltroonery of the commander of our armies’. Kutuzov asked him to return on the following morning, with the Metropolitan Archbishop, two miraculous icons of the Virgin, and enough monks and deacons to stage a procession through the Russian camp before the battle.53

After Rostopchin’s departure, Barclay and Yermolov came to see Kutuzov and pointed out that, following a full reconnaissance, they had come to the conclusion that the position was indefensible. ‘Having listened attentively, Prince Kutuzov could not conceal his delight that it would not be him who would bring up the idea of retreat,’ wrote Yermolov, ‘and, wishing to divert from his person any possibility of reproach, ordered that all senior generals be called to a council of war at eight o’clock.’

When this convened, Kutuzov began by stating that in the circumstances it would be impossible to hold the position they had chosen, as it could easily be broken and turned. If they were obliged to disengage and fall back, they would find themselves fleeing through Moscow, which would probably result in confusion and the loss of most of the artillery. ‘As long as the army exists and is in a condition to oppose the enemy we can preserve the possibility of bringing the war to a favourable conclusion,’ he explained, ‘but if the army is destroyed, Moscow and Russia will perish.’

Kutuzov then asked the others to give their opinion, but seemed uninterested in what they had to say. Uvarov and Osterman-Tolstoy agreed with him, but others were incensed. Bennigsen suggested going onto the offensive and delivering a vigorous attack on one of the French corps while they were on the march, in which he was enthusiastically supported by Dokhturov, Yermolov and Konovnitsin. But Barclay pointed out that even if they had the men, they simply lacked enough experienced officers to carry out an offensive manoeuvre. Raevsky agreed that since the army was so weakened, and since the Russian soldier was unsuited to offensive tactics, the only thing to do was to abandon Moscow.

Bennigsen pointed out that nobody would believe they had won the day at Borodino if the only consequence of the victory was retreat and the surrender of Moscow. ‘And would we not then be obliged to admit to ourselves that we had in truth lost it?’ he questioned. After about half an hour of this discussion, Kutuzov broke in, declared that they would be leaving Moscow, and ordered a general retreat.54

Konovnitsin claimed the hair on the back of his neck bristled at the thought of abandoning Moscow, and Dokhturov was unsparing in his indictment of ‘those small-minded people’ who had made the decision. ‘What shame for the Russian people; to abandon one’s cradle without a single shot and without a fight! I am in a fury, but what can I do?’ he wrote to his wife that evening. ‘I am now convinced that all is lost, and since that is so nobody will convince me to remain in service; after all the unpleasantness, the hardships, the insults and the disorders permitted by the weakness of the commanders, after all of that nothing will induce me to serve – I am outraged by all these goings-on! …’55

Another who was outraged was Rostopchin, who at seven o’clock that evening received a note from Kutuzov informing him that he would not be making a stand in defence of Moscow after all. Rostopchin flew into such a fit of despair that it was all his son could do to calm him down. ‘The blood is boiling in my veins,’ he wrote to his wife, who had left the city some time before. ‘I think that I shall die of the pain.’56 He then busied himself with countermanding all the preparations he had made for the defence and hastened the final evacuation of the city.

Ever mindful of his reputation, Kutuzov sent Yermolov to Miloradovich, who was in command of the rearguard, with orders to ‘honour the venerable capital with the semblance of a battle under its walls’ once the main army had moved through. Miloradovich was indignant. He saw through the ploy: if he were to score some success, Kutuzov could say he had mounted a defence of Moscow; if he was defeated, Kutuzov could blame him. Later that night Kutuzov wrote to the Tsar, explaining that he was abandoning the city to the enemy, declaring that it was an ineluctable fact that the fall of Smolensk had entailed the fall of Moscow, thus deftly shifting the blame from his shoulders to those of Barclay.57

The retreat began at once, and by eleven o’clock that night the artillery was rolling through the streets of the old capital. Staff officers with platoons of cossacks were posted at strategic points to direct the columns and keep order. ‘The march of the army, while being executed with admirable order considering the circumstances, resembled a funeral procession more than a military progress,’ according to Dmitry Petrovich Buturlin. ‘Officers and men wept with rage.’58

But order soon began to break down. As news of the retreat swept through the city, people spilled out into the streets. Over the past weeks Rostopchin had managed to inflame the inhabitants to such a degree with his rabid proclamations that they had reached fever pitch. There had been fights and brawls during the past few days. Some hurled insults at the retreating soldiers, others opened their shops and houses and began handing out their goods so the French would not get them. Rostopchin was busily evacuating everything he could, and setting fire to stores of wheat and other victuals. Tens of thousands more civilians now left the city, taking the same direction as the troops and encumbering their march. Stones as well as abuse were hurled at the carriages of departing nobles, and in some instances wounded men and officers were dragged off wagons and out of carriages to make way for fugitives and their chattels. ‘There was shouting and lamenting everywhere,’ recalled N.M. Muraviov, ‘the streets were full of dead and wounded soldiers.’59

In the midst of this violence and confusion people tried to locate relatives or friends, and officers who were from Moscow went home to at least provide themselves with some necessities and a change of clothes. Captain Sukhanin decided to call on an acquaintance, Count Razumovsky. The Count was not at home, but the servants welcomed him as though nothing was happening. ‘The Count’s cook prepared breakfast for us, they brought wine, the musicians laid out their notes and began to play,’ Sukhanin wrote.60

As the streets became choked with horses and vehicles, the waiting soldiers wandered off to find food and particularly drink. They were soon breaking into wine shops and cellars, helped by the city’s criminals; Rostopchin had opened the gaols and asylums. He had ordered a number of buildings to be set on fire, and the looting added to the fires blazing throughout the city.61

Rostopchin himself narrowly escaped being lynched when a baying mob surrounded his palace, only saving his skin by handing over to them a young man accused of being a French spy, who was promptly butchered as the Governor drove off. As he was leaving the city, he came face to face with Kutuzov. The commander had asked his aide-de-camp Galitzine, a Muscovite, to lead him through back streets so that he should not encounter anyone, so he was particularly annoyed. Galitzine recorded that Rostopchin tried to say something but was cut by Kutuzov, while Rostopchin, more credibly, claims that Kutuzov told him he would be going into action against Napoleon soon, to which he replied nothing, ‘as the reply to a bêtise can only be a sottise’. Either way, the meeting was enjoyable to neither.62

Another altercation took place between the commander of the small Moscow garrison and Miloradovich. The elderly general marched his men out of the Kremlin with their band playing. But as he proceeded through the streets he came across Miloradovich, whose rearguard was now moving through the city. ‘What swine ordered you to play?’ Miloradovich roared at the garrison commander. The latter pointed out that according to regulations laid down by Peter the Great himself, a garrison must always march out of its fortress to the sound of a military band. ‘And what do the regulations of Peter the Great have to say about surrendering Moscow?’ snarled Miloradovich.63

Miloradovich had reason to be tense. As he approached Moscow with the rearguard in order to march through it and out the other side, he discovered that Polish Hussars from Murat’s corps were already riding into the city, and that he and many other small units or groups of soldiers were in effect swamped by the rest of the King of Naples’ corps. Had Murat pressed on, he could have scooped up not only Miloradovich’s rearguard, but also a large portion of the Russian army, which was still straggling through the streets and in no position to defend itself, including a great many officers.

Miloradovich sent an officer to Murat to say that he was willing to hand over Moscow without a fight if Murat would only halt his troops for a few hours and give him time to pass through it. If Murat refused, he threatened to set fire to it as he retreated. Murat, who knew Napoleon wanted Moscow whole, and who, like most of the French, thought the war was to all intents and purposes over, agreed to this. He noticed that the cossacks escorting the officer who had brought him the message looked at him with awe, and positively drooled when he pulled out his watch, so he gave it to one of them and ordered all his aides-de-camp to give theirs as well.64

The truce merely formalised a situation which was already developing naturally. A quartermaster of one of the cossack regiments in the Russian Second Army watched in astonishment as a French cavalry division allowed a Russian brigade to trot through their ranks and out of encirclement. Heinrich Roos, a medical officer with the Württemberg Chasseurs, noted that there were hundreds of Russian stragglers in the streets, and that nobody on the French side bothered to pick them up, as everyone considered the war to be over. He came across some lightly wounded Russian officers, so he dressed their wounds and directed them to their units, which they were able to rejoin. When his Chasseurs met a regiment of Russian dragoons beyond the city, there was amiable fraternisation rather than fighting.65

If the French believed the war was over, the Russians felt that the world had come to an end. ‘The entire army is as though undone,’ wrote Uxküll as he watched the flames shooting up from the city they had evacuated that morning. ‘There is much talk of treachery and traitors. Courage has been undermined, and the soldiers are beginning to revolt.’ They were also now deserting in large numbers. Lieutenant Aleksandr Chicherin felt that ‘the last day of Russia’ had dawned as he marched through Moscow, and he could not accept any of the practical strategic arguments put forward for abandoning the city. ‘Wrapping myself in my greatcoat, I spent the whole day in an unthinking torpor, doing nothing, unsuccessfully trying to repress the waves of indignation which surged over me again and again,’ he wrote in his little diary.

Many now accepted that Alexander would have to make peace with Napoleon, and even the diehards thought this to be inevitable. Some were already talking of going off to fight against the French alongside the English in Spain.66