From the USNO to Germany

If the monotony of computing was difficult for other bright women, it must have

been especially difficult on Alice Gray, for she was, to say the least, a free spirit.

—The Contributions of Women to the

United States Naval Observatory

At the age of twenty-two, seven months after receiving her degree, Alice left Chicago to work in Washington, D.C., at the U.S. Naval Observatory (USNO). For the next two years, she worked as a “computer,” one of the earliest group of women hired in this capacity.

To apply for the position, common practice meant taking the Civil Service Examination. Job applicants competed in a standardized hiring system, which did not reference gender at the time of application. The exams were graded, and applicants with the highest scores landed at the top of the hiring list. Successful candidates learned of their acceptance via telegram.

Alice forged ahead with her career despite prevailing societal attitudes about women and work. In 1903, the same year she was hired by the USNO, John T. Doyle, then secretary of the United States Civil Service Commission, had this to say about the future of women in government employ:

It is too early to pass judgment on what she can do in competition with men in the higher fields of business endeavor. She needs a generation or two in which to get to her enfranchisement, to practice her untried powers and to rise out of centuries of self-effacement, repression and insufficient equipment. She needs time to perfect her gradual approach to man’s powers in mental work. She has done well in the ordinary clerical grades.31

Doyle noted that women were welcome to apply for a list of particular government jobs, all requiring passage of the Civil Service Exam: piecework, computer (not only for the naval observatory but also in the Nautical Almanac Office), architectural designer, photographic assistant, chemical clerk, department assistant in the Philippines (bookkeeping, finance and chemistry) and “preparator” or “modeler” in the National Museum.

The government, Doyle wrote, could provide women with a golden opportunity to move up in the work world. “In the government service she is finding a career and opportunity for the development of her powers. Uncle Sam, with all his faults, is the best-natured and most generous of employers. He does not cut wages to a starvation basis nor unfeelingly dismiss dependent women like an unscrupulous sweater or contractor.”32

Alice began her job at the USNO on October 22, 1903. According to employee records, she was “attached to the Division of Meridian Instrument under the direction of William S. Eichelberger for a period of seven months as a computer engaged in general reductions under the direction of the committee on editing and printing.” In this capacity, she might have edited tables of numbers for correctness and looked over page proofs before they were published.

Women computers working at their desks in the main building of the United States Naval Observatory, much as Alice would have done. Courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

Following this stint, Alice worked as a “miscellaneous computer.”

Merri Sue Carter, USNO astronomer and historian, describes the work performed by Alice as “incredibly tedious, monotonous.” Computers had second-class status as workers, Carter says; the observatory referenced them as “subprofessionals.” Work shifts lasted ten hours per day. Alice spent these hours working on an almanac; she figured routine equations to help chart the location of stars. At the time, hand calculations were the only means to a result. One part of the overall calculation fell to each computer, the same part for each equation. The daily task played out something like this: Alice would work ten steps of a logarithmic equation, pass her calculations on to the next computer and then work the same ten steps again, using new sets of numbers each time.

Alice’s pay remained constant during her job term, about $1,200 annually. The pay scale was firm, with little hope of a raise; it was set in 1892, twelve years prior to Alice’s hiring.

Most USNO computers were women. Because of strict nepotism rules, all men and women were single or married to people working elsewhere.

Despite their mathematical abilities, female computers could not hope to win more challenging opportunities within the observatory. Several limitations prevented this, Carter notes. Senior positions required a navy commission—which, by law, women could not obtain. Also, admission to scientific societies often depended upon the extent of one’s publishing in academic journals, but articles emanating from the observatory staff routinely carried the name of the author’s supervisor, rather than crediting the author directly.

Furthermore, because the observatory insisted that all research must directly relate to navy operations, the most exciting and progressive projects landed at the doorsteps of private and university observatories, rather than the USNO.

Carter writes:

When evaluating the success of the women employees prior to 1920 one must be aware that the most successful career path at the Observatory at this time required a person to be able to observe with one of the many telescopes on the grounds. However not a single observation at the Naval Observatory was made by a woman until after World War I...there was a general policy of discrimination against women as observers.33

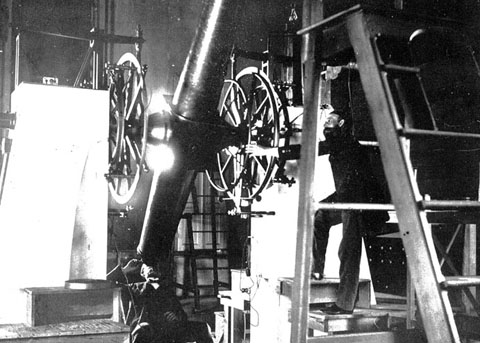

William Eichelberger (right) is shown working on the nine-inch transit telescope in 1901. Alice worked for Eichelberger as a computer at the USNO. Courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

Carter points to the oral history of Alfred Mikesell34 for further clarification: “Women were not allowed to observe because ‘It would be immoral for women to be alone amongst the equipment at night,’ and ‘Women did not have the abilities that would be required to observe nights.’”

Alice lived within walking distance of the USNO. In her first year, she boarded on U Street in a typical red brick row house that still stands. Sometime during the next year, she moved to Wisconsin Avenue, closer to the observatory.

Perhaps by her own design, relatively little of Alice’s period of employment at the observatory is documented. No “official” photograph exists in her employee folder, although the files of other women who worked there at the time do include photographs. Observatory computers frequently enjoyed luncheons to celebrate one another’s personal news and achievements and to mark anniversaries and holidays. Many snapshots of these luncheons are archived, with all the women clearly identified on the back of each photograph. Alice is not among them; for whatever reason, she completely avoided photographers during her two-year employment.

A notation in Alice’s file illustrates her penchant for adopting habits that others found disconcerting for lack of feminine qualities: “Miss Gray...had cut her hair short. She also worked in pants!” By ignoring both proper and stylish appearances of the time, Alice was clearly out to impress people using nothing more than her intelligence.

Carter calls Alice one of the USNO’s “best and brightest” and lauds her tenacity for sticking with the job of computer for two very long, very flat years:

If the monotony of computing was difficult for other bright women, it must have been especially difficult on Alice Gray, for she was, to say the least, a free spirit. Not much is known of her work here at the Observatory, though she was known to have had an intense interest in astronomy and wanted to pursue her studies in tide research.35

Whether it was boredom, a desire to further her studies or something else that propelled Alice elsewhere is unknown. Perhaps her work at the USNO lasted as long as it did because she was saving money for her next adventure. In any case, her own words, spoken to a friend, indicate that she left the U.S. Naval Observatory bound for study in Germany.36

Records show Alice M. Gray was admitted as a “guest-listener” at the prestigious University of Gottingen from the winter semester of 1906 through the summer semester of 1908.37 The university did not record information about what visiting students studied; furthermore, transcripts of visiting students left the institution when the students did, in their own care. Although there is no official documentation, Alice likely focused on mathematics.38 In a letter dated years later, Chicago historian Olga Schiemann wrote that Alice had “three years of higher mathematics in Germany.”39 Schiemann had become a friend in whom Alice confided various threads of her personal story.

A few months after classes ended in 1908, Alice left Germany. Identifying herself as a “student,” she departed from Liverpool, England, traveling as a second-class passenger on the ship Kensington. She arrived back in North America at Quebec’s Montreal port on September 28.

By October, Alice had already enrolled in graduate studies at the University of Chicago. Of her three classes, two were mathematics seminars. The third was a “physical culture” (physical education) requirement. During the first eight of the next ten quarters, beginning in the winter of 1909, Alice enrolled in nine mathematics courses, including several seminars. She studied the theory of numbers, algebraic theory and foundations of pure mathematics.

In the winter of 1910, Alice took a lecture class in labor and capital issues, along with mathematics. A year later, she studied elementary Italian and enrolled in a “pure mathematics” seminar. That seminar marked her last class devoted to the study of numbers.

Alice enrolled only in beginning Sanskrit in the summer quarter of 1911; she sat out the fall and winter quarters of 1912. When she registered for classes the following spring, Alice’s thoughts were not on mathematics: she was interested in philosophy and signed up for two classes—one focused on Descartes and the other on the “logic of social sciences.” Although Alice did not complete the philosophy work, she received an “A” in her third course, a political science class titled “Population & Standard of Living.” It was her last course.

After four years of graduate studies, Alice discontinued her education at the University of Chicago. In a diary entry she wrote three years later, she expressed some regret about having made that choice. “If I had had faith and gone on energetically with either mathematics, or logic, or ethics, or literature, or politics, or any combination of two or more of the five, or anything else under the sun, doubtless it would have been well with me.”40

During her time as a graduate student, many sources suggest she was an editorial secretary for the University of Chicago’s Astrophysical Journal. (This could not be verified with the University of Chicago.) In another diary excerpt, Alice mentioned editing a book and debated whether she might have edited another one had she stayed in Chicago.41 It would have been one or both of those two positions that she left behind when she settled in the dunes region. She never worked in an office again.

It is not easy to track Alice during the years after she stopped taking classes and before she moved to the Indiana dunes; she is not listed in Chicago city directories. Her great-niece, Marion LaRocco, shed some light on that difficulty: “At that time, when you rented an apartment you got the first month’s rent free. At the end of the month, Alice would move and rent another one.”