Driftwood

The highest bravery in the world is loyalty to one’s trust. It may be simply

withholding the world, refusing to stoop to court, or to compromise, letting the

world and its glory pass by without a regret or a thought, willing to be thought

nothing, but in reality, in one’s self possessing one’s own desire.56

—Alice Gray

Finding shelter was an immediate concern for Alice, especially since she arrived in the dunes country just before winter. She told a reporter that she had moved into an abandoned fisherman’s shack after four days spent sleeping outdoors. It was “ten feet square and without windows,” as one news account described it; that same article provided its location, which had been discovered coincidentally by county surveyors working in the area. “The cabin is just behind the last bridge toward the hike...and only an arrow trail leads to it from this way after entering the dunes about half way between Baillytown and Dune Park.”57

It was speculated that her shack at one time belonged to George “Sandhill” Blagge, a well-known dunes dweller who had died during the winter of 1914. Thought to be a Civil War veteran, Blagge was a gentle loner with whom neighbors gladly shared an occasional supper. That Alice took over his sandy turf was of no public concern—and fortunately, no one else laid claim to it.

As if to announce the transfer of property, she gave her sand-floored, crudely constructed shack a name: Driftwood. “Everything I have here, this chair, this cap I wear, these tins, are driftwood, drifted in from the lake—I, too, am driftwood.”58

A photo of Alice’s shack, which she named Driftwood. The photographer made a notation on the back that reads, in part: “I made the picture in the winter. She was inside.” Courtesy of the Westchester Township History Museum.

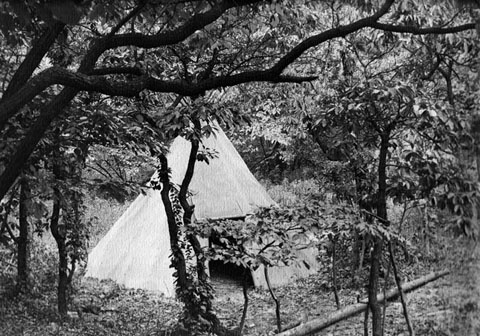

But in that first winter, Alice made use of another encampment whenever she could. Known as Sassafras Lodge, it was a teepee, owned by naturalists Flora and William D. Richardson, located in a deep hollow of what is now the community of Dune Acres.59

In a memoir written by a friend of the Richardsons, Alice is mentioned—not in a kindly way—as a frequent visitor to their campsite. They discovered her much earlier than the newspaper reporters (although writing about her later, the author adopted the same colorful language of the press):

One day we discovered an unkempt, raggedly dressed, snarled hair subterfuge of a young woman had appropriated Sassafras Lodge as her permanent abode. Later a Chicago Tribune reporter publicized her in a series of articles as “Diana of the Dunes.”...(We) permitted her to stay provided that on the days we were there she left it to us. This she usually did. We seldom saw her but saw signs of her but we could not understand the filth she left. It was a golden rule with us to always leave the Dunes as you found them....We finally had to ask her to leave because the camp was so filthy and she herself so unkempt.60

Naturalist William Richardson took many photographs during his visits from Chicago to the Indiana dunes. His property in Dune Acres is now known as the Richardson Wildlife Sanctuary. Courtesy of the Westchester Township History Museum.

A fall view of the teepee owned by naturalists Flora and William Richardson of Chicago. Early on, Alice often used the teepee when the Richardsons were away. Courtesy of the Westchester Township History Museum.

On the other hand, during the same general time period, Mathilda Burton, a fisherman’s wife who claimed to be her nearest neighbor, noted that Alice kept her shack “scrupulously clean.”61

Life in the dunes meant learning new approaches to ineffectual city ways: avoiding sunburn in constant exposure, staying warm during a winter storm, obtaining and storing food and supplies and finding stray materials to furnish a rough-hewn hut. Basic needs—including food and, for Alice, library books—forced her to walk into towns such as Chesterton, Miller, Porter, Baillytown, Furnessville and Michigan City.

In her diary, Alice described some of the immediate challenges she faced in her new life. Because she feared strangers would steal her meager belongings, she kept close watch on them. She collected pine boughs and added them to her oil cloth and blanket bedding to help block the cold from her mattress of sand, and she knocked on farmhouse doors hoping to buy bread, milk and eggs from homeowners. One evening, she was reminded of a fundamental lesson regarding her most plentiful resource, sand:

I remembered that it had rained a little the night before, and my blankets were a little damp. So I built a fire in the iron box I had found ready at hand, which makes cooking so unexpectedly convenient, and spread out my possessions on the ground around it....Feeling very happy and domestic and much pleased with myself and the world, my world, large and small—when, the fire dying down, and my towels being not quite dry, I moved the iron firebox with the idea that the sand under it would be the best means of finishing the drying, and deliberately put my hand—my right hand—caressingly on the sand to see if it was warm enough to do the towel much good, I suppose. My God—how it hurt! The shame of having done such a fool thing was hardly second to the pain of the burn.62

The next day, she inventoried her “pre-breakfast” food supply. “My stores are now reduced to three eggs, half a slice of bread, a little oatmeal, coffee and salt, a bacon rind and some grease, a cabbage and a very few apples and radishes.”63

A 1916 newspaper article asserts that Alice, in pursuit of food, became quite a huntress, based on the number of trophies hung on a line outside her cabin. The reporter described her deft marksmanship: “During all the bright nights the wild ducks remain out on Lake Michigan. At dawn they come flying in to seek the little marshes as their feeding ground. Miss Gray is ready at the last ridge and as the birds come over she pops them right and left.”64

However, in a letter written in 1954 by Olga Schiemann,65 it was noted that the “revolver” Alice brought with her to the dunes “rusted immediately and was never shot off.” In a second letter, Schiemann refers to the same worthless weapon as a “shot gun.”

Schiemann befriended Alice after stumbling upon her shanty in the dunes. Her family often fed Alice during those first few years of dunes living. “It happened she chose a spot very close to where we were staying and we adopted her when we were there over the weekends.”66

The Schiemanns weren’t the only family to share food and conversation with Alice. The late Margaret Larson, lifetime resident of the area, wrote about Alice in her memoirs:

One day when I returned home from school my mother happily said, “I had company today! You know people have been talking about a woman who seems to be in the dunes just like George Blagg.” Well, this woman came to the door and had been told that mother had known all about the Bailly family. She introduced herself as “Alice Mabel Gray” of Chicago but was living in the dunes. My mother invited her to come in, although she said she was perturbed since her visitor was dressed in men’s clothing and had a “deep voice.” As it turned out they visited several hours and when Alice got ready to leave mother loaned her our copy of Frances Howe’s French Homestead in the Old Northwest. Alice noticed the rows of books in the bookcase and said, “I’ll be back, please.”67

Larson recalled that Alice visited “many” families in Baillytown—on Saturdays to pick up someone’s molasses cookies, once to get help from another neighbor in laying a pattern on material for a skirt or occasionally to visit with Agnes Larson, Margaret’s mother, for coffee or a taste of Swedish rye bread.68

Hazel Blythe, another longtime resident, said her family lore relates that Alice bought baked goods from her grandmother, Anna Larson. Her aunt, Ethel Larson, a librarian in nearby Miller, used to say that Alice “was a very intelligent lady, read a lot, and checked out large armloads of books.” Blythe noted that her family consensus was simply this: “A lot of things written about ‘Diana’ were not true.”

Accounts of Alice’s personal appearance also vary, mostly relative to the seasons. In her first years in the dunes, it can be gleaned from newspaper accounts and from those who met her that she typically wore simple skirts with middy tops or rumpled dresses; it was reported that she favored wearing black, but likely it was one black outfit that she wore time and again.

The home of Margaret Larson, which now serves as the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore Learning Center. Courtesy of the Westchester Township History Museum.

By all accounts, Alice wore her dark hair short, or “bobbed,” a style consistent throughout her dunes years. During her interview with the reporter, Burton, the fisherman’s wife, said that Alice cut her own hair, judging its desirable length and shape by the shadow she saw of herself in the sand.69

Although possessing a mirror might have seemed an extravagance to Alice, or at least difficult to come by, without one she was unaware of how she appeared to others. She apparently offended the Richardson camping group with her looks, but they weren’t the only ones—and sometimes, she even frightened herself:

I wonder if this life is really as good for me as I thought. I stopped in cheerily on my way back to see Mrs. B. Combing her hair, she referred to her looks, and that reminded me to look in the glass. What a sight! I looked like a delirious Indian. Nose red from a little cold and much wiping—eyes pale and staring in the general smoky red, teeth pearly by contrast, and, oh, what a forlorn, unwashed, gaunt face!

This morning I washed in hot water and plenty of soap—I had only a rub off before since the day by the fire in the wigwam—and looked civilized except—as the glass revealed—for a grimy underchin and neck.70

In a second diary entry, she wrote:

Friday I walked to Oak Hill and while waiting for Mrs. Larson to come home with my groceries I had the first good look I have had of myself insome time. To tell the truth, I was rather shocked. My eyes seemed to have a rather wild, strained look as if the life I was leading were very wearing on me. I said to myself that I would be afraid if I met myself alone at the crossroad in the moonlight. However, I was not so bad with my hat and coat on.71

The idea of Alice walking great distances is a popular one. She was reported to have walked for miles at a time—among the dunes, from the dunes into one town or another and all along the beach, including from Driftwood to her sister’s home in Michigan City, Indiana. Marion LaRocco, Alice’s great-niece, said her family was often amazed by how far Alice traversed on foot—she sometimes journeyed from the University of Chicago campus to the home of a niece who lived on the north side of the city. LaRocco heard such stories about Alice from her mother, Dorothy Dunn Noble, and her aunt, Marion Dunn, twin daughters of Alice’s sister, Leonora. They were in high school during the time Alice lived in the dunes region.

When Alice walked to Michigan City, LaRocco said, she was not just out for the exercise: “My mother said Alice once in a while appeared without warning late in the morning. She would have the worst attire on—men’s trousers and a gunny sack for a shirt.” Knowing that Marion and Dorothy came home from school for lunch, Alice arrived early so she could be sure to talk with them. “She wanted to go to school with them, too. But the girls would slide out the back door and get back to school without her,” LaRocco said. They loved their Aunt Alice—the entire family thought she was “brilliant” and interesting—but the twins were simply too embarrassed by her clothing.

The Gary Evening Post72 reported that Alice never wore shoes or stockings in the summer but wore big boots in the winter. In warmer weather, she wore a light dress with a “ragged waist” over it and, in winter, the same ragged waist over a short, coarse skirt and a “little cap”—probably the same cap Alice mentioned as part of her “driftwood” possessions.

The home of Alice Gray’s sister, Leonora (Gray) Dunn, in Michigan City, Indiana, as it appears in modern times. Courtesy of the author.

A deep winter snow blankets the teepee, known as Sassafras Lodge, owned by Flora and William Richardson. Alice was known to use the teepee when the Richardsons were not visiting the dunes. Courtesy of the Westchester Township History Museum.

Burton described Alice’s winter attire as “heavy mackinaw socks, such as lumberjacks wear,” a man’s cap, a gray wool skirt and a knee-length coat.

Her appearance, notable due to its plainness, was generally tolerated in deference to her way of life.

Those who knew Alice found her not only sane and friendly but also fascinating because of the wide range of topics she could discuss. Perhaps, too, her voice—which had some remarkable quality—added an element of wonder to conversations. Although Larson’s mother described it as deep, it has also been called pleasant73 and lilting.74 LaRocco said that Alice loved to listen to her niece, Dorothy, play the piano. “Alice didn’t seem to be musical herself, except for her voice. My mother used to say her speaking voice was beautiful.”

Schiemann described Alice in a letter written to an acquaintance in 1952:

Several years of sun and wind on her hair and skin didn’t make it look any better. She had no iron to iron the clothes which the sun soon bleached out, so she didn’t look like the ordinary person, but I grew very fond of her and we often spent long hours together around the fire after the others had gone to bed while she told me about the stars in the heavens, etc. She was a freak or eccentric to most people then and yet, but I stood up in a couple of meetings of Duneland [Historical Society] defending her as best I could.75

During an oral history project, two longtime residents of Chesterton, whose families knew Alice, spoke of their early experiences.76 Margaret Larson was one of them, along with Evelyn Shrock, now deceased.

For many years, the city of Chesterton, Indiana, held a Diana of the Dunes festival. The Duneland Chamber of Commerce ended the tradition in 1999 because of dwindling attendance, but not before many annual contests for young women had proclaimed the winner as Diana of the Dunes. Larson found a touch of irony in this: “People couldn’t figure (Alice Gray) out, you know. To the people who do the pageant now, she is just an imaginary thing. These girls who are so anxious to be named ‘Diana of the Dunes’ don’t know what they’re doing, because she was not very glamorous.”

Evelyn Shrock remembered her mother enjoying Alice’s company. “She used to come to our house and my mother would fix her a cup of coffee and a slice of homemade bread, maybe made into a sandwich. She would sit and talk to her. She was as interesting as she could be.”

The late Mrytle Isbey, who was along time Porter resident and part of the same oral history project, recalled Alice’s unusual appearance: “I remember when she roamed the beach, dressed in a gunny sack with that little bitty hat. That was in 1915. I knew her. She was a very smart woman, but boys he was quaint.”

Dorothy Johnson Higgins, deceased, used to speak of her younger half sister, Helen Mentzer, swimming as a child with Alice in Lake Michigan.

Dr. Richard Whitney, now a resident of California, spent many summers of his childhood roaming the sand hills of Indiana and the beach along Lake Michigan. Landmarks and roads were few back then, but he believes his family’s cottage was somewhere between what is now Dune Acres and Miller Beach. In a 2005 interview, he recalled playing hide-and-seek with other children in the woods. “Never a day went by that Diana of the Dunes was not part of our pretend games,” he said, noting that one of the boys would inevitably ask, “What if we run into her?” Although they did not regard Alice as a fearful creature, the thought of her did conjure up a witch-like character—“but a good witch,” Whitney remembered. To their extreme disappointment, the encounter never happened.

But they did see her elsewhere. As children, Whitney and his pals walked barefoot to a general store with pennies in their pockets to buy a Mary Jane or a Tootsie Roll. Occasionally, Alice would be in the store and there would be some commotion about her. He also recalled that every so often his neighbors would spread the word that Alice was out in public buying supplies. Some then dashed into town, hoping to catch a glimpse of her.

In this photo, the woman seated to the far right of the picnic-goers is assumed to be Alice Gray. The photo, published in the Gary Post-Tribune on December 29, 1963, was discovered by the late Arthur Johnson of Porter, Indiana, among his family albums.

Such vivid oral histories about Alice are valuable and few. In Alice’s case, the primary sources used to develop her story are newspaper articles, a good many of which featured bad reporting and the sometimes tall tales of local townspeople. These are mingled with truer stories told by those who met her or whose families pass their original Diana stories to the next generation. Often, it is difficult to sift fact from fiction. In reading over the body of news stories from the time, however, certain consistencies rise to the top, while obvious distortions sink from the added weight of their falseness.

Reading those many articles in context with other sources—such as the oral histories from people who knew Alice or whose families had knowledge of Alice, personal letters or comments written by her contemporaries and published excerpts from Alice’s diary—some underlying assumptions become more certain.

In those early years, she did not live the life of a hermit, but neither did she seek attention. Her actions seemed to be guided by the necessities of survival; her quietude was devoted to discovering herself, as well as her environs:

I have been—for me—just a little depressed the last few days—ever since I came up here, perhaps; but think it has been due entirely to physical causes—food and thin clothing. How glorious this outdoor life is—how good life feels and tastes and smells down close to the great elemental things; this blazing fire, with the white brilliance in the west, just one star (Venus or Jupiter?) high up in the southeast, the dull white snow patches in the hollow and on the southern slopes, and the snow-flecks brown of the western slope, and the light gone for writing and the time come for supper.77

It does not seem far-fetched that as one of those necessary activities, Alice swam naked in Lake Michigan. Although legend has it that she did so at the first sign of ice melting on the lake and continued to do so until ice returned the following season, she discounted reports of brave winter plunges. “Just don’t imagine that I spend my days and nights up here going in bathing (I did go in yesterday, but I’d like to see myself going in just now with the frost still in the air), climbing hills to gaze at views and wiggling my toes before the fire. Far from it.”78

It’s a matter of practicality that Alice bathed in the lake (twice daily, morning and early evening, so the rumor went) when temperatures allowed for it. (To some, it would be a wonder if she didn’t swim five times a day during the blazing heat of an Indiana summer.) And if she did so without clothing, as fishermen claimed, she was keeping clean and dry what few clothes she owned. Bearing in mind that Alice lived in an area that was generally uninhabited and not commonly visited by townspeople or vacationers, her behavior does not seem so suspect. Only after Alice was discovered did fishermen put her on their regular route, and even then it was often with sightseers aboard who were hoping to see the “mermaid.” Later accounts assert that she did don a bathing suit, no doubt because the encroachment of civilization spoiled the notion that her location could be considered remote.

Once she arrived in the dunes, it did not take Alice long to begin contemplating her new life. While she was satisfied, she was not immediately comfortable with her solitary existence. She had been away from Chicago less than a month when she wrote the following:

Generally, especially when I write, or walk, or sing, or read, or recite my favorite poems—I am very, very happy and contented with my lot and my course. Then once in a while I wonder if I am childish, futile, foolish, a “skulker” as someone called Thoreau—anonentity, a shirker and deserter and coward and egoist. Yesterday was one of the days of such doubt of myself.79

A Message from the Sea, etching by Earl H. Reed and published in his book, Voices of the Dunes. Courtesy of the Westchester Township History Museum.

While she fought off self-doubt, she also wrestled with the rhythm of solitude and the inevitable rising of imponderables: “Yesterday I longed for society—the companionship of some big, clear-eyed, single-hearted, frank soul, who would talk to me...about life and love, about God, freedom, immortality.”80

It would be several years before Alice found a constant companion with whom to share her dunes life.