Surfacing in the Dunes

It is a country for the dreamer and the poet, who would cherish its secrets, open

enchanted locks, and explore hidden vistas, which the Spirit of the Dunes has kept

for those who understand.81

—Earl H. Reed

July today emulated the drive of allies and swept the city with liquid fire.82

—the Gary Tribune, 1916

Mysterious, gravitational swings in behaviors and temperaments swept through the Indiana summer of 1916. Odd things were happening; some explainable, others strange enough to put folks on edge. Local newspaper stories, published just during the weeks of July, show just how crazy the world had gone.

Perhaps the mystique of the spectacular solar eclipse that month inspired some cosmic sense of change and rebellion.83

Or maybe it was fueled by grief. James Whitcomb Riley, the state’s beloved poet, “the children’s friend,” died that July. As his body lay in state, thousands lined the streets around the Indianapolis State House, waiting to pay their last respects. There was talk of naming a proposed national park in the Indiana dunes region in honor of the bard.

Political battles brewed, too. The cry for a Sand Dunes National Park stirred individuals, groups and cities all along the southern edge of Lake Michigan. Editors splashed headlines across the pages of their local newspapers touting articles and editorials that left little doubt where their allegiances lay. A rally designed to raise awareness and stir the souls of supporters was staged at the foot of Mount Tom, the region’s tallest dune. The event received plenty of coverage, much of it echoing the same sentiment: preserve the exquisite beauty and rare ecological wonders of the dunes for the sake of posterity.84 Besides, organizers argued, the Midwest was sorely in need of a convenient vacation destination.

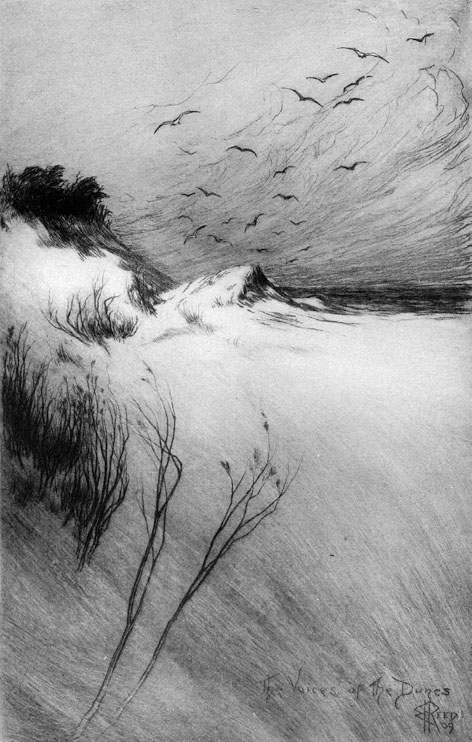

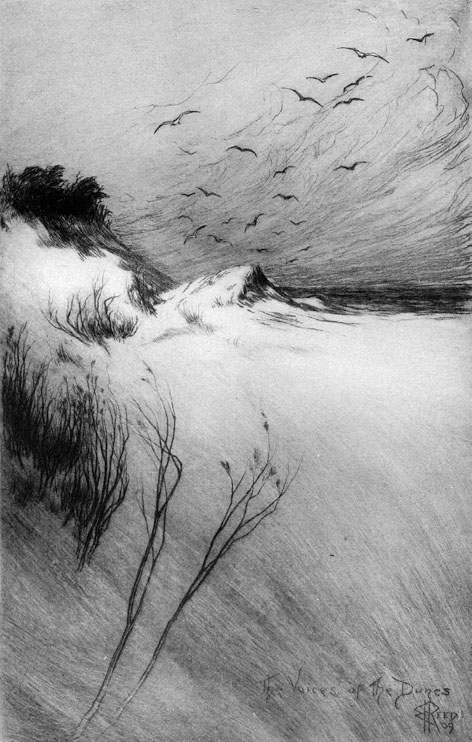

Voices of the Dunes, etching made by Earl H. Reed, author of the book by the same name. Courtesy of the Westchester Township History Museum.

Some estimates placed the number of people attending the rally at several thousand; however, most participants opted to cool off in the lake rather than listen to speeches given in a blowout of the dunes. It was a hot day after all, and many had traveled some distance by car or train to attend. Why not enjoy the surroundings they had gathered to protect?

Front pages also captivated the public with some less important, but otherwise adventurous, stories featuring odd twists. Two articles about “woodswomen” were still fresh in their minds when readers first discovered Alice in news pages the following week.

One local paper reported that seven women planned to live for a month as “modern Eves” in the Adirondacks, under the watchful eye of a male naturalist, to prove that “women as well as men can live in the woods by their own devices and with what nature offers.”85 John Knowles planned to find his entourage a camp, leave them for a month to enjoy his own solace and return to fetch the women on his way back to civilization.

The same week, the Porter County Vidette reported that five women hailing from nearby Illinois towns were intent on hiking twenty miles a day through Indiana. Their final destination was a summer camp in Niles, Michigan. Attired in “appropriate costume,” the women wore “short skirts of durable canvas, stockings that look like socks, heavy boots, military capes and broad hats.”86According to the article, they were all looking forward to the exercise.

While voting rights and the opportunity to hold representative seats in Congress were high on the list of priorities for female activists at the time, women across the country were stretching in other political ways as well. Under the headline “What Will These Women Try Next? They Want a Birth Control Exhibit at Duluth Lecture,” readers learned of the radical birth-control philosophies espoused by Mrs. Robert Liggett of Duluth, Minnesota, and the questionable mass mailing tactics of Margaret Sanger of New York, a prominent birth-control advocate and women’s rights activist.87

Closer to home, a fluke incident required the emergency aid of Gary Boy Scouts. They answered the call to hunt with harpoons for a baby shark that escaped from a college professor’s care into Lake Michigan.88 The professor had intended to present the shark as a gift to a local school. The shark, meantime, had already attacked a twelve-year-old boy, mauling his feet. Residents feared worse if the shark adapted to its new freshwater home and grew.89

The month-long blistering heat that nearly broke the back of the Midwest was by far the biggest story. The torrent of hot weather did not spare the Greater Gary region. Records were set for both high temperatures and death rates, while serious ice shortages caused problems, especially for hospitals. The sweltering days created havoc and spawned riots along the beaches of Lake Michigan. In Hammond, Indiana, officials installed a large clock near the beach to encourage bathers to be mindful of each other and voluntarily limit their time in the lake to two hours. Swimming overtime was an issue that went beyond overcrowded conditions, however; in those days, most bathers rented their swimsuits: “By remaining in the water three or four or five hours bathers renting suits monopolized them while a long line waited outside the turnstile last Sunday.”90

Laundering swimsuits in between uses was a general practice. In the oppressive heat, the usual standards fell a few notches: “So great was the demand for bathing suits that they were used again without drying, eager ones getting into ’em wet.”91

Throughout the month, beaches—and the roads used to reach them— were jammed.

With the temperature at the highest point ever reached since Gary started, the shoreof Lake Michigan from Pine east to Tremont, 17 miles away, was alive with human beings seeking the relief to be gained from the cooling waters.

On the beach, thousands of people were splashing in the water at one time. The Carr bath house early in the day hung out the sign that all bathing suits were rented.92

Following are dire headlines in a Chicago newspaper, all published on the same day, July 30, 1916:93

Dwellers in Ghetto Walk All Night to Escape Heat—Firemen Turn Rain Clouds; Cool Streets with Hose—Let Men Remove Coates in CafÉs, Says Coroner—Protests Against Hot Uniforms of Policemen—Mercury at 109 in Gary—County Hospital Centers Efforts on Heat Victims—Thousands Beg Chance to Sleep on Municipal Pier.

The waves of suffocating summer heat rolling through Indiana crashed into the roiling political waves of World War I. Published reports from Europe were long and frequent in local newspapers.

Timing, they say, is everything.

In the midst of this national and international contentiousness, public anxiety over strange phenomena and the intense heat that marked both days and nights, the newspapers hoisted Alice Gray from beneath the swell like a trophy fish caught on the final run—unsuspecting, unwilling and greatly exaggerated. Immediately, she found herself cast as the diversion in a nervous, heat-stricken community, a giddy overture to the more serious business of politics and a vulnerable target for lack of fortified defenses. Alice could not have anticipated the tremendous attention she would attract or the awkward, insensitive rush of celebrity that quickly followed. Her second thoughts about staying in the dunes—and she did have them—must have come fast and furious.