Paul Wilson: Caveman

Paul Wilson was a powerful man, over six feet two inches and spare build, but

weighed 225 pounds. I have seen him more than once walking over the dunes from

the highway with two ten gallon cans of gasoline for his boat, one in each hand.

This means a walk of over a mile and a half.118

—Samuel Reck

Giant in stature, an eye like an eagle with revolver or gun, he was a man to

be feared.119

—the Evening Messenger, 1923

Paul Wilson was a man of remarkably tall stature, taller tales and a short, fiery temper. Like Alice, he shunned societal constraints and rules—an attitude that no doubt made them kindred spirits. Eleven years her junior, he was not as well educated as Alice, although his imagination was keen. Words often used at the time to describe the sand hills region—trackless, wild, untamed—also seemed to define Paul. His attraction to the dunes appeared to be driven by a sense of its lawlessness rather than any poetic interest in studying its environmental wonders. He was a local drifter who finally found among those wild sand hills a reason to stop wandering: Alice Gray.

During the seven years Alice and Paul lived together, they relied on each other, complemented each other’s survival skills and remained consistently loyal in difficult, sometimes dire, circumstances. For his part, Paul dedicated himself to protecting Alice from outside intrusions and met their needs any way he saw fit—whether that meant through honest trades such as fishing, furniture making and building boats, or by petty thievery. The press often referred to him as Alice’s Caveman. By most accounts, he adored her. That she welcomed him into her private enclave—and let him stay—took the eavesdropping public by surprise at every turn.

Paul Wilson. This version of his photo was found at the Westchester Township History Museum; the original publication and publication date are unknown.

Written stories and oral histories describe Paul as an offensive individual with unusual strength, prone to disputes and outbursts involving neighboring beach dwellers and fishermen, local sheriffs and deputies and reporters. Paul waxed on about a Texas childhood made tragic by the death of his parents, causing him eventually to leave their home in San Antonio and take up the life of a drifter. In reality, his father, Otto Eisenblatter, was very much alive and living in Michigan City, although his mother, Caroline, had died on March 18, 1918, just a few months before he met Alice. After her death, he became estranged from his family, which included two brothers and two sisters. The youngest child, Alfred, was just thirteen years old when Paul met Alice; two other siblings, Otto and Margaret, were nineteen-year-old twins, and his sister, Esther, was twenty-six.

The childhood home of Paul Wilson, located in Michigan City, Indiana, as it appears in modern times. Courtesy of the author.

All of the children, except Paul, still lived with their father at the time of the 1920 U.S. census.

Paul was born on June 25, 1892, and baptized the following August as Paul George Eisenblatter in the German Methodist Episcopal Church of Michigan City. He was reared for a time in a small frame house on Douglas Street that still stands today. Somewhere along the line and for reasons unknown, he dropped his family’s last name.

At age seventeen, Paul was still living in Michigan City. Both he and his father worked at the Haskell and Barker Car Company, Paul as a “stenciler” and his father as a “riveter.”

It’s difficult to follow his path from that point, but a Michigan City native later said he served in the army with Paul in Texas.120 Paul said he also lived for a while in Pennsylvania. When a newspaper reported in 1922 that his family had confirmed he had spent time in jail there, his father was compelled to write a letter to the editor denying that anything of the sort was said. “Such statements are unwarranted as none of our family have been informed as to Paul’s whereabouts since his mother’s death several years ago and we do not know of him being in prison at any time....As far as I know, such statements are mere neighborhood talk. Very truly yours, Otto Eisenblatter.”121

Paul once claimed he was a rattlesnake hunter in Texas and another time said he was a prizefighter there.

In any case, Paul was twenty-six years old by the time he found himself back in Indiana. He might have heard about the strange woman called Diana of the Dunes, and, as a man who liked to spin far-fetched stories about his own history, Paul may have sought Alice based on the local gossip, admiring her odd independence. In a 1922 interview with a reporter,122 he spoke of meeting her by chance, but at the time they first encountered each other he was roaming the beach near Alice’s cabin—nearly ten miles from Michigan City, the place he once called home.

According to Paul’s loose-knit story, he found his way to Indiana for the first time when he and another man traveled to Gary from Pennsylvania to find work in the steel mills, having done similar work in the East. When Paul somehow lost track of his companion, he disembarked the train in what he thought was Gary (Paul encountered another misstep getting off the South Shore train years later, one that landed him a jail sentence) but in retrospect decided it was actually the outskirts—probably the Wilson stop.

Seeing the lake and feeling tired and dirty, Paul opted to swim (noting to the reporter that he was a “good swimmer”). He dropped his “bundle,” including the clothes he wore, on the beach and enjoyed a refreshing nighttime dip in the water, only to discover afterward that someone had stolen his clothes.

(Was it just coincidence that Paul surfaced in much the same way Alice did—swimming naked in Lake Michigan? Or did he fashion yet another tale, this time using bits of Alice’s well-worn story?)

In the darkness, Paul said, he thought he had tracked the thief who nabbed his bundle, but he had mistakenly pounced on Diana while she was entering her shack. After a hasty explanation, they walked back to the beach and shared a long talk. He worked for a while at the nearby steel mill and then moved in with Alice just about the time he was arrested.

It was the couple’s first separation—and likely their only one—when Paul began serving a six-month jail sentence late in 1918 for stealing from a handful of cottages nearby. Along with food and guns, he nabbed articles of women’s clothing, including a winter coat. The path of his footprints, visible in rainsoaked sand, marked the trail from the scene of his last theft directly to Alice’s shack, resulting in his arrest. Although the case against him was compelling, Alice vehemently declared his innocence in a later recounting of the incident. “When those two men charged him with stealing, with only a bit of a wrist movement he could have laid them both away, but he knew that would prejudice the neighbors against me. So he took the punishment for my sake.”123

In the course of the manhunt, Paul was shot in his right leg by Elmer Johnson, whose cottage had been burglarized. It was not the last time he would feel the searing pain of a bullet, although several years would separate the incidents.

Paul began serving his sentence at the penal farm in Putnamville, Indiana, in December of 1918. The previous winter had been the coldest on record for the region, but January through March of 1919 were comparatively mild, except for a brief period of drifting snow and high winds. Perhaps because Alice had experienced the harsh winter the year before—a frigid season of blizzard conditions that completely shut down lake commerce, as well as services in local communities—she sought temporary refuge sometime in the early months of 1919 at the home of Charles and Hulda Johnson. They lived along the Old Chicago Road, now known as Route 12, about a mile south of her shack.124

Just before she died at the age of ninety-four, the couple’s daughter, Irene Nelson, spoke about living with Alice that winter. Nelson was ten years old when Alice became her family’s house guest for about six weeks; Paul was incarcerated during this same time. The children always referred to Alice as Miss Gray, Nelson said, although her brothers teasingly referred to Paul as the Jailbird, rather than Mr. Wilson. He wrote letters to Alice from prison, which she received at the Johnson home. This would not have been unusual; throughout her first years in the dunes, Alice had her mail sent care of the Johnson address, according to Nelson.

For the most part, the family found Alice entertaining and pleasant.

“My brothers and I always said she made the best hot cocoa we’d ever tasted,” Nelson said. Alice also amused the children by creating wonderful hand shadow pictures and plays on the wall. She might have stayed longer with theJohnsons, but a surprising behavior—one seemingly out of character for the Alice they knew—caused her premature, abrupt departure.

One late afternoon, Alice, Nelson and her mother were in the kitchen, Irene Nelson recalled. While Mrs. Johnson was busy at the stove, Alice began reading a personal letter just arrived in the day’s mail. Suddenly, Alice let out an agonizing shriek and cried, “And I thought he believed in free love!”

The outburst disturbed Hulda Johnson, a devout Swedish Lutheran. She was appalled by the very idea and upset by the lack of discretion, as well as the intensity, of Alice’s mournful wail.

With little hesitation, Nelson recalled, her mother turned from the stove and said, “Miss Gray, I believe it’s time for you to return to your own home.”

What exactly was meant by the words Alice so painfully read aloud remained unclear to Nelson, although she assumed the letter writer was Paul. Or was it? A persistent rumor was that Alice had run to the dunes three years before to escape a failed love affair. Her outcry over the letter occurred in the spring of 1918; the following summer, she would publicly settle the love affair debate once and for all.125

After she moved out, the Johnson family continued a neighborly relationship with Alice. She often bought bread, eggs and blueberries from Mrs. Johnson. “Miss Gray did not like picking blueberries, the bushes were too prickly,” Nelson recalled. Stray folks who came looking for Alice (one would assume most of them were reporters, although Nelson remembered such visitors only as “friends”) knocked on the Johnsons’ door. Young and nimble, Nelson guided them through the woods, over the dunes and past the swamp areas—less than a mile from her house toward the lakeshore—and left her charge within sight of Alice’s dwelling. Nelson never saw the cabin’s interior, noting that Alice never let anyone else inside, either.

It seems unlikely that Alice received much in the way of mail after her first year in the dunes. Initially, she picked up small checks, installments for payment on book-editing work she had done prior to leaving Chicago.126 Along with letters from Paul, written during his six-month jail term, there may have been a few notes from old friends still living in Chicago and perhaps some correspondence with her sister Nannie, who lived in Iowa, or her sister Leonora, who lived nearby in Michigan City, Indiana.

For all his wild ways, Paul was devoted to Alice. It was a mutual admiration. In an interview several years later, he described their relationship to a reporter: “Diana and I have been getting along like two kids. We never quarrel and have many things in common. She is what I call ‘the truth.’ I have the first time yet to catch her in a lie.”127

At some point, Alice and Paul pulled up stakes at Driftwood and moved farther west to an area along Lake Michigan now known as Ogden Dunes. (An exact location of their cabin has not been verified.) Whether they built their own shack or Alice again co-opted an abandoned one is unclear. It seems likely that the move took place during the summer of 1918, soon after Paul finished serving his six-month jail sentence. He claims they took a slight detour before settling down. “Diana stuck to me through it all. After I got back, we took a little trip to Knoxville, Tenn., where we were married. We came back to the beach shortly after that, and have been living here ever since.”128

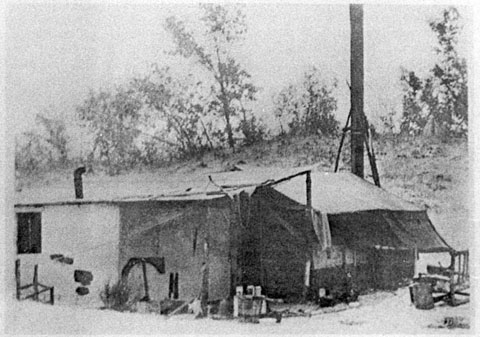

Wren’s Nest, the Ogden Dunes home of Alice and Paul. The cabin was destroyed in 1925, but its smokestack was reportedly present until the early 1930s. This photo is from the Gary Post and Tribune’s June 19, 1922 edition.

The couple never legally married, but later mentions refer to their “common-law” marriage. They named their new abode Wren’s Nest.

A later news account about their relationship describes the chores Paul did for Alice, including catching fish, gathering wood, foraging for the daily menu, repair jobs and “other man-sized duties and burdens which she shouldered.”129The author took care to note that Alice continued to help in these pursuits and mentioned that, on rare occasions, the couple took sightseers out on their fishing boat.130

Paul relied on Alice to make visits into town for food and supplies; he seldom traveled far from the beach.

What he did not know about the dunes, Diana taught him from experience. He soon knew every inch of the dune country, from Ogden Dunes, past Waverly Beach to Michigan City. He was an expert guide and could tramp the dunes with his eyes shut.131

The same year Alice and Paul moved into Ogden Dunes, Camp WinSum—built by the Boy Scouts—rose up a block west of their shack. The campers made use of two sturdy rowboats built for them by Paul, but for the most part interaction was limited. The lack of contact was enforced by a Scout rule barring the boys from visiting Wren’s Nest: “Heavy penalties were inflicted on Scouts who violated the rule, like a week of K.P. duty. However, Diana and Paul didn’t observe the same rule, and often a large supply of food would be reported missing from the camp’s larder.”132

Despite such claims, after the petty theft charge for which he was jailed, Paul steered clear of real trouble—that is, until the summer of 1922 when a violent incident in the dunes showed just how brittle their stake in the sand hills had become.