2

Symbolic Constructs of the Cosmology

Many would say that the defining statement of ancient cosmology is expressed by the words “as above, so below,” a phrase that is often interpreted to imply that the processes of the macrocosmic universe are in some way fundamentally similar to the microcosmic processes that create matter. Simple observation suggests that the two are similar; even a middle-school science student can see obvious similarities between an electron that orbits the nucleus of an atom and a planet that revolves around a star. Many of the symbolic themes of the various traditions we are studying can be seen as metaphors for this same defining phrase. For example, the earliest creator-deities of ancient China are pictured holding tools of measurement in their hands; the mother goddess Nu-wa holds a compass, which she uses to measure the circularity of the heavens, and the creator-god Fu-xi holds a carpenter’s square, with which to measure the squareness of the Earth. These ancient Chinese images imply that a fundamental relationship exists between the macrocosm and the microcosm, which calls out for reconciliation. Within that same mindset, symbolic constructs of the cosmology are often given from each of these two perspectives: one that is macrocosmic, and another that is microcosmic.

Mythic definitions that relate to the macrocosm begin with a cosmogonic egg that is described as containing all of the future “seeds” of the universe. In reference to their creator-god Amma, the Dogon refer to this structure as Amma’s egg. The Dogon priests say that this egg was the product of two inward-facing “thorns,” likely correlates to two black holes in the terminology of modern astrophysics. For astronomers, a black hole is a point in space-time, such as a collapsed star, that has become so very massive that it draws in virtually everything that comes within its field of gravitational pull. The Dogon say that for a long period of time, these two “thorns” were able to hold the primordial matter they contained in stasis, but that this matter began to spin ever more quickly until a point was reached when it simply could no longer be contained. At that stage, the egg ruptured, scattering “pellets of clay”—correlates to astronomical bodies—to all corners of the universe. Using images that seem intentionally symbolic, the Dogon myth of the creation of the universe (see here) compares the sun to a clay pot that has been raised to a high heat and the moon to dry, dead clay.

Dogon descriptions of matter in its microcosmic wavelike state also begin with an egg, one that is conceptualized as the heart of a symbolic fish called the nummo fish. Like the Dogon and Egyptian terms bummo and bu maa, this Dogon word nummo also can be compared to an Egyptian term, nu maa. The Dogon, like modern astrophysicists, believe that matter begins as waves and is transformed by an act of perception into particles. The Dogon/Egyptian term nu refers to waves or water, and the term ma or maa implies the concept “to examine” or “perceive.” The Dogon priests create a drawing of the nummo fish that serves as a diagram to illustrate the kinds of transformations that are said to occur just after matter in its wavelike state has been perceived.

Figure 2.1. Dogon thorns held in stasis

(from Scranton, Cosmological Origins, 98)

Figure 2.2. Dogon nummo fish drawing

(from Scranton, Cosmological Origins, 112)

From this perspective on creation, the egg, which is located where we would expect the heart of the fish to be, represents the point of perception of a wave. The notion of matter in its wavelike state is conveyed by the lines that define the tail of the fish. The collarbones (the Dogon say “clavicles”) of the fish depict the wave as it draws up in response to this act of perception, creating a shape that the Dogon compare to a tent cloth that has been pulled upward from the center. From there, the waves on either side of the peak of this “tent” begin to vibrate and encircle, creating a series of primordial “bubbles.” The first six of these “bubbles” ultimately collapse under their own weight, then after the seventh cycle they produce a sustainable bundle that the Dogon describe as the egg of the world. The Dogon conceive of this bundle as seven rays of a star of increasing length and characterize it by the spiral shape that can be drawn to inscribe the endpoints of the rays. This egg is a conceptual counterpart to the Calabi-Yau space in string theory, which is conceived of similarly as a bundle of collapsed dimensions that is said to exist at every point in space-time.

Inherent in these definitions, from the point just after the perceived wave rises up, are the cosmological concepts of duality and of the pairing of opposites. In fact, the Dogon priests define these two attributes as fundamental principles of the universe. As a reflection of these principles, many of the symbolic definitions of the cosmology are given in opposing pairs, through concepts that can be expressed symbolically in numerous ways. In some cases these principles are reflected in the pairing of male and female deities. In other cases, such as the Chinese concept of yin and yang, they are depicted as complementary shapes defined in opposing colors (traditionally black and white in the case of the yin/yang symbol). When describing the primordial elements of water, fire, wind, and earth, these principles are expressed as opposing aspects of each element.

There is also little question but that the concept of the aligned ritual shrine stands as the foremost symbolic construct of the creation tradition. Both the Dogon and the Buddhists assert this to be true, and each treats these structures as a kind of grand mnemonic symbol for the entire tradition. Stupa shrines are readily found all across India and Asia, and comparable structures take many variant forms in other widespread regions of the world. These forms begin with the simplest stone cairn and end with the Great Pyramid of Giza. A host of shared symbolic attributes argue that this class of aligned shrine includes such diverse types as the Mongolian yurt, Navajo roundhouse, Native American tepee, and even the traditional Jewish huppah. Again, for the sake of convenient terminology within this study, our choice will be to refer to these structures under the heading of stupas or aligned ritual shrines.

So pivotal is the symbolism of the stupa to the cosmological tradition that, by strictest interpretation, the shrine is assigned the role of a purely symbolic structure, one that is actually prohibited in some cultures from being put to any practical use. In fact, the dimensions that are given by the Dogon priests as measurements for their aligned granary include an internal contradiction in math, such that the shrine simply cannot be built precisely as defined. Everyday Dogon agricultural granaries that are actually used to store grain bear only a modest resemblance to the symbolic structure that is outlined in their cosmological tradition.

As the Dogon explain it, alignment of the ritual shrine was one of the first instructed exercises presented by their ancestor-teachers, but specific details about how the shrine was to be aligned are perhaps best explained in the Buddhist tradition. The practical requirements for accomplishing this alignment make good sense, when looked at from the perspective of a group of knowledgeable teachers faced with the task of implementing them in an environment where basic tools and materials for construction might not have been readily available. Alignment of the base plan of the stupa begins as a rudimentary exercise in geometry, where the first task is simply to draw a circle around a defined center or point.

It is important to understand that the alignment method for a stupa rests on proportional relationships that hold true for geometric figures of any size and so did not require a standardized unit of measure or a refined set of tools for precisely measuring them. Appropriate to that requirement, the ancient teachers apparently established the concept of a cubit, a unit of measure that could be marked out in relation to a person’s own body. Like other concepts that are put forth in our cosmological plan, the cubit was assigned two distinct definitions: By one definition, the cubit represented the distance from a person’s elbow to the tip of the middle finger. By another, it represented the average step or pace of a person as he or she walked.

As support for the view that the cubit was seen as a relative unit of measure as opposed to a precise one, we cite A. E. Berriman’s classic book Historical Metrology: A New Analysis of the Archaeological and the Historical Evidence Relating to Weights and Measures, where Berriman provides a long list of ancient cultures known to have used cubits, alongside the many variant unit lengths that were applied to the measure.1 Likewise, we know that within a given culture such as ancient Egypt, different cubit lengths seem to have coexisted, perhaps defined for different purposes or in relation to different symbolic concepts. One should also keep in mind that each two-dimensional geometric figure that appears within the cosmology was also likely to have a three-dimensional correlate. This means, for example, that any symbolism that is assigned to a circle would also apply similarly to a sphere.

The center of the circular base plan of the stupa was defined by a stick that was placed vertically in the ground. In some cultures, an additional step was taken that involved using a plumb line to assure that the stick was actually set vertically. Next, a simple line of radius was marked out from the stick, measured at twice the length of the stick itself, and a circle was then drawn around it. Using the shadows cast by the stick (or gnomon) in the sun, this base plan of the aligned stupa shrine served as a functional sundial by which an initiate could effectively track the hours of a day. The need for accurate timekeeping constituted one of the prerequisites for a working system of agriculture.

As the next step in aligning the shrine, the initiate marked the two longest of the stick’s shadows of the day (one in the morning and one in the evening) at the points where they crossed the circle. These two points were then connected with a line that, because the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, automatically took on an east-west orientation and so defined an east-west axis for the circle. With the geometry of this added line, the sundial now became a tool capable of tracking the apparent motions of the sun throughout the year, and so gave visibility both to the concepts of a season and a year. Furthermore, if an initiate were to plot the east-west line every day with regularity, he or she would see that it passed through the stick on only two days of the year, on the dates of the two equinoxes. After that, the line would move progressively farther away from the stick until the next solstice, at which point the line would reverse its direction of motion.

In the next stage of the alignment of the shrine, the initiate drew two additional circles of a slightly larger radius than the first, each centered on one of the two endpoints of the east-west line. The larger radius caused these circles to overlap one another, intersecting at two new points. These points defined a second line that was perpendicular to the first, which served as a north-south axis for the circle. Taken together, the two intersecting axes divided the original circle (the circular base plan of the shrine) into four equal quadrants. This base plan, founded on a figure that the Dogon refer to as the egg in a ball, egg of the world, or the picture of Amma, would later be understood to be one of the central symbolic shapes of the cosmology.

At this point in the process, the alignment geometry of the ritual shrine was complete and produced matching ground plans for the Buddhist and Dogon shrines. However, in the next stage of the process, the circular base of the shrine would be effectively squared. The concept of reconciling two fundamental geometric figures, the circle and the square, is one that is central to ancient cosmology. From some perspectives the circle is symbolic of the creational processes of the universe or macrocosm, while the square relates symbolically to earth and to the microcosm where matter forms. Because of this, reconciling a circle with a square becomes a metaphor for the Hermetic phrase “As above, so below.” In relation to the plan of the ritual shrine, this squaring was implemented in slightly different ways by the Dogon and the Buddhists. In the Dogon plan, the shrine rose ten cubits upward to a square, flat roof (leaving the shrine with a round base), while the Buddhists approach was to actually square the base of their stupa. Overt squaring of the circle in the Dogon system was accomplished by means of a second circle that was inscribed within the square of the roof. The Dogon priests assigned numeric measurements to their shrine that revealed an underlying rationale to their version of the plan: The central stick measured five cubits and the radius of the circle ten cubits, while the square roof of the Dogon granary was defined as eight cubits per side. Mathematically, if we apply 3.2 as an approximate value for pi, this produced a square whose numerical value of area matched the numerical value of the circumference of the circular base—both with a value of sixty-four—and so reflected a self-confirming measurement. Self-confirmation of measurements is an architectural feature that is indicative of deliberate design, and so suggests that the Dogon plan may preserve an original form.

Conceptually, the alignment of the base plan of the shrine was meant to define an ordered space (the Buddhists might say “sacred” or “ritualized” space) marked out from within the comparative disorder of an uncultivated field. In fact, in Dogon culture the act of cultivating land is conceptualized as bringing order to a disordered field. It is understood in both the Dogon and Buddhist traditions that this process of alignment replicates a primordial process of creation. Each component geometric figure evoked by the plan of the shrine carries symbolism that is shared commonly by the Dogon and the Buddhists, and there are multiple symbolic perspectives from which to view the shrine itself. The initial figure of the circle with its defined center is a product of the motions of the sun and is used to measure those motions, so it is understandable that it came to symbolize both the sun and the concept of a day. For similar reasons, it is also easy to understand why the figure came to be associated with concepts relating to time measurement, such as a season or a year. Our contention based on how this same shape is applied in other symbolic contexts such as Egyptian hieroglyphic words is that it could also reasonably represent the motions of the Earth in relation to the sun, such as the daily rotation of the Earth on its axis and the annual revolution of the Earth around the sun.

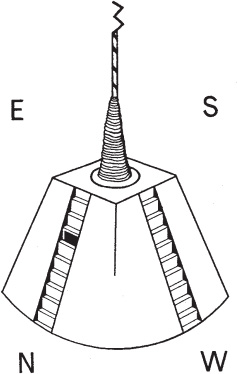

Figure 2.3. Dogon granary

(from Scranton, Cosmological Origins, 8)

For the Dogon, the square, flat roof of the granary represents the concept of “space” as it relates to matter, and the same symbolism applies to the squared base of the Buddhist shrine in its original round configuration, which is seen as “ritualized space.” In both traditions the body of the aligned shrine is equated with a hemisphere, a three-dimensional geometric figure that conceptually reconciles the rounded dome of a circle with the base of a square. For the Dogon this hemisphere signifies “mass or matter,” while for the Buddhists it represents the very similar concepts of “essence” or “substance.”

The two derived axes of the base plan of the shrine are understood to define the cardinal points and were specifically given in reference to the geographic directions of east, west, north, and south. As suggested on here, these axes can be alternately conceived of in three dimensions by imagining that the central stick or gnomon defines a third vertical axis. This three-dimensional figure, which consists of six rays and a seventh central point, mimics the seven rays of the Dogon egg of the world, the essential underlying structure of matter, and so from this perspective the shrine itself can be seen as a symbolic representation of this egg.

The two-dimensional divided circular figure that evolves as the base plan of the aligned ritual shrine is alternately referred to by the Dogon as the egg in a ball or the picture of Amma. According to the Dogon priests, the central point of the figure is actually conceived of as another very small circular space, which is where the Dogon creator-god Amma is found. Although this idea is not spoken of in public, Amma is considered to be so small as to be effectively “hidden” and is understood to be dual in nature (from one perspective, Amma is interpreted to be both male and female). To underscore these points, the plan for the Dogon granary shrine provides that a small cup holding two even smaller grains be placed at the center point of the shrine.

The two defined axes of the base plan of the shrine (one with an east-west orientation and the other aligned north-south) symbolize the axis mundi, the “axis of the world.” The concept of the axis mundi is often alternately represented in myth as a world tree, whose significance is taken to apply both to microcosmic matter and to the macrocosmic universe. However, commonalities exist between Dogon and ancient Chinese mythic references that suggest that in the original plan of cosmology, two symbolic trees may have been conceptualized. The first is described as a mulberry tree that is rooted in the primordial waters and grows upward through the conceptual worlds of matter. The second mythical tree, whose associations may have been primarily to the biological-reproductive theme of creation, is commonly referred to as the tree of life and is sometimes interpreted to have been a palm tree. One ancient Egyptian term for this tree is aama,2 a word that calls to mind the name of the Dogon creator-god, Amma. In the Dogon and Egyptian cultures, this dual-tree symbolism seems to have survived in the more generic form of a single world tree or tree of life.

From other perspectives, Adrian Snodgrass relates that the stupa symbolizes a cosmic mountain that stands at the center of the universe.3 The mountain is an important symbolic concept in many of the cosmological traditions we are studying, one that pertains both to the creation tradition and to the civilizing plan. The spire on top of a traditional stupa symbolically represents a “hair tuft” or topknot of hair that stands at the summit of that symbolic mountain.

There is another perspective on the symbolism of the Dogon granary shrine that associates its structural elements with bodies of the solar system. In this view, the circular base represents the sun, the circle that is inscribed within the square of the roof represents the moon, and the shrine itself represents the Earth—the astronomical body that lies conceptually between the sun and the moon.

The plan of the aligned ritual shrine defines its symbolic elements in a way that might be confusing to some researchers and may have caused some to suspect that a reversal in symbolism had occurred at some point in the history of the tradition. Based on the discussion of the primordial Chinese deities in my book China’s Cosmological Prehistory, a circle is symbolic of the heavens, which we associate with the modern term space, while a square is associated with earth, a term that we interpret symbolically to refer to “mass or matter.” But in the plan of the ritual shrine it is the figure of the square that overtly represents space. To my way of thinking, this confusion arises from what may be fundamentally a linguistic problem, which was likely caused by modern-day changes in meanings for the word space. As we proceed, we will see that there are multiple perspectives from which to consider the geometric figures of the circle and the square, and so the symbolism may not always seem to have been entirely clear-cut or consistent.

Important alternate symbolism attaches to the plan of the aligned ritual shrine as it relates to the biological-reproductive theme of the cosmology. From this perspective, the shrine is associated with the expanding womb of a woman, and the center of its circular base plan is considered to represent a navel. From this point of view, the related axis is interpreted as an omphalos munde or umbilicus mundi, essentially the symbolic umbilical cord of the world.

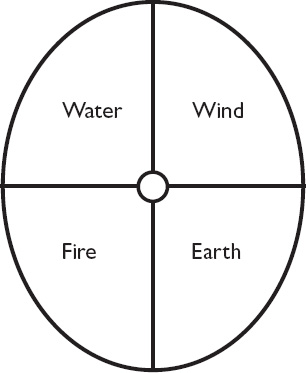

In their context within the Dogon egg-in-a-ball figure, the four defined quadrants of the base plan of the aligned shrine are associated with the four classic elements of water, fire, wind, and earth, and so represent the four progressive stages in the creation of matter, as previously discussed. This association underscores the symbolic relationship of the shrine to the components of matter.

Figure 2.4. Dogon egg-in-a-ball drawing

(from Scranton, Cosmological Origins, 63)

These quadrants define the layout of the four lower compartments of the granary shrine, but the structure is constructed in three dimensions, and the plan also calls for four upper compartments, for a total of eight, symbolizing the eight cultivated grains of Dogon culture. From the standpoint of cosmology, these compartments also represent the eight component stages of the egg of the world, which include the seven collapsed dimensions of matter that initially comprise the egg and an eighth conceptual stage in which the bubble-like egg is ruptured. The rupturing of the egg is also said to initiate the formation of a new egg. Descriptions given by the Dogon priests suggest that these eggs combine together in a series to become counterparts to the membranes of matter that are defined in string theory.

Symbolic constructs of cosmology such as the ones we have been discussing are understood to have preceded written language in ancient cultures. However, as we will see, the suggestion is that they provided a set of ready-made conceptual images that could then be adapted to symbolic written language.