1: Setting the Goals

When your children leave home to go out into the world on their own, what home skills will they be able to perform? If you could give each child fifty thousand dollars as he or she departs, would that be as valuable as if they had mastered some basic skills in preparation for adult life: The little things that have to be done every day even if they live to be 103? If young adults know how to clean a house and keep it that way, how to select and cook good food, or how to budget money, then they are released from the extra time it takes to learn these things when time is needed to concentrate on studies, career, or other areas of living.

Consider the case of a twenty-one-year-old girl named Annie who moved to Colorado hoping the dry climate would help clear up a health problem. When she drove up to her new apartment in her little compact car, she had her clothes and six thousand dollars’ worth of debts. Her own parents had advised her to buy not a used but a brand-new car, a new sewing machine (she is learning to sew), a new piano (someday she hopes to play), and correspondence art lessons; all of these when her job paid minimum wage. Annie’s lack of understanding of nutrition and how to cook soon affected her health. She struggled to read a city map. She had had so little experience in the world that it was easy for someone to take advantage of her. A friend called her from overseas, collect, and talked for twenty minutes. You guessed it! She did not know that collect meant she would pay for the call. All of these problems and a lack of preparation made her very discouraged. Is it possible that many of us are raising Annies?

As parents, if we do not have goals for our children an Annie is possible, and we cannot help them set goals if we have only a vague idea of what we wish them to achieve. You may ask, “Do we as parents have the right to decide on the goals our children should achieve?” Our answer is yes, because once the parent establishes the parameters in which the child can safely act and develop skills for successfully meeting life’s challenges, then the child’s right to choose comes into play. The child usually does not have the maturity to set goals without these limits. Unfortunately, we usually give more careful planning to a two-week vacation than we do to the training of our children in the basic home living skills. As a parent, there are ways to prepare your child for the Big World whether they are two or twenty-two. During the eighteen years or so a child is in your home, you will be doing lots of things and going many places, so why not get full value from these experiences through goal setting, and plan your activities to provide the maximum instructional benefit for your children? The child’s accomplishment of skills will improve self-image and give the confidence on which to build even more skills. Independent children can bounce back from crises and move forward while dependent children are more vulnerable to problems that can ruin their lives. You, the parent, will enjoy many rewards too; your sense of success develops, the workload is shared, and the child will be working with you rather than against you. Setting these goals will create more time for the parent and child to enjoy other things in life.

It is interesting to note that in a survey we took, asking 250 children about working at home, ninety-seven per cent felt they should help. Listen to the reasons they gave.

Children said they should help at home because:

“Then parents won’t go nuts trying to do all the work by themselves.”

“They make a lot or half of the mess in the house. They also are going to have a house someday, and they need to know how to clean and cook.”

“It will be easier to get a job and support yourself.”

“It gives you experience, gets you organized, prepares you for later life.”

“Children have to learn responsibilities, because if they don’t, when they grow up they will be lazy bums.”

“Then we get all the work done so we can do the fun things.”

“My mom and dad are divorced and my mom has always had a full-time job. Therefore, she needs our help. My sister and I (seventeen and twelve) don’t expect her to do both.”

“I think it forms good habits when the child becomes an adult.”

“It helps Mom and Dad out because they are putting food on your plate.”

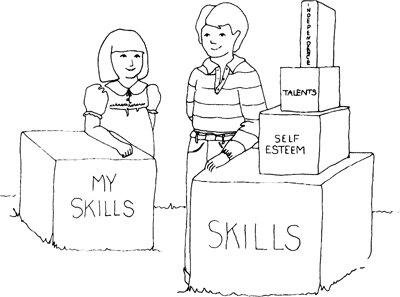

As parents, we can become aware of methods that help the child see both what needs to be done and ways that create independence. For example, one youthful volleyball captain was so anxious for her team to win, that she began issuing constant commands. When a girl made a mistake, she told that girl exactly what should have been done. “You should hit it with your fist. Move up, you’re back too far!” Within ten minutes this novice captain had every girl looking toward her, waiting for instructions before making a move. Some parents do this at home, telling the child each move to make. But we want the child to develop independence as well as obedience. There are seven steps in training independent children and getting them to work at home:

The first four are the groundwork done before telling the child to “get to work.” The real fun is in teaching the child how to do a task and making up incentives that motivate. The rewards come regularly as the child learns skills and develops self-confidence. Before actually starting to teach, you need to decide where you and your child are going.

If you don’t decide on your goals, you’ll become like Alice in Wonderland, who was asked by the Cheshire Cat where she wanted “to get to.” When Alice answered that she didn’t “much care where,” he said, “Then it doesn’t much matter which way you go.”

WHERE ARE YOU GOING?

It does matter which way we are going with our children. To help in goal setting, think how a school system might do it. Many schools have punch-out progress cards that move with the child from grade to grade, showing which skills in math and language arts the child has studied and passed. The list could look very discouraging to a first-grader, but as the child works day after day, concept upon concept, a great many things are learned. Wouldn’t it be interesting to see what level your child would be on in “Home Living Skills”?

The following Home Progress Chart has been designed to help define what you hope your own children will have learned before leaving home. The chart is a beginning point and a recording sheet; reduce or expand it to meet your circumstances. Remember that, without being conscious of it, we often forget to teach the youngest child what we taught the older children out of necessity. Also, we neglect to teach boys some household jobs and girls some repair skills, assuming they will have a spouse to handle those omitted areas. But we suggest boys and girls will benefit from learning about both areas. Handicapped children should also learn as many skills as they can possibly master.

Although the chart basically includes household responsibilities, full support should be given to the child’s school studies. You might also want to include some marketable skills and provide outside help from other teachers for typing, upholstering, electrical repairs, and the like.

Now go through the chart, deciding which skills you want your children to develop. There are many entries provided, but it may be more beneficial to choose three categories, look those over carefully, and decide on one skill that you would like to teach your child from each category; or you could choose three skills from only one category. If you have several children who are close in age you might work with them as a group, or you can teach one child now and the other children later. Some skills you will only introduce at this point and expect mastery later. Your children are introduced to a skill when they have direct participation in the job through observing others doing it, asking questions about it, or helping with part of it. They have mastery when they can independently complete the task at least three times with success. Remember that the Home Progress Chart is only a guide (not a test) to help you set goals for your family. Some items listed may be unimportant to you and there may be other skills you wish to add. Be flexible and have fun evaluating and dreaming.

HOME PROGRESS CHART

1. Write the child’s initials next to the skill you want to teach. There is room for the initials of several children.

2. When the child has mastered the job, place a slash through the initials. [![]() Clean own drawers(6–14)]

Clean own drawers(6–14)]

3. The numbers printed after each skill represent the earliest age to introduce the skill and the age at which you can expect mastery. Of course, every child is different and you must be flexible with the ages, judging from your own experience, the facilities available, examples of friends and siblings, and the child’s confidence and maturity.

4. Use the same chart for both girls and boys because we cannot insure the skills will be needed by only one gender.

Example:

Phyllis and her daughter (age ten) looked at the Home Progress Chart together and chose one skill from each of three different categories.

Category |

|

Skill |

Money Skills |

|

Make a checking account deposit |

Cooking |

|

Select and prepare fresh fruits and vegetables |

Navigation and Auto |

|

Ride the city bus |

By choosing only three skills to develop, they were not overwhelmed, and could begin meeting the goals immediately. Later in this chapter, we will explain the Three Teaching Elements to help you be very specific about reaching your goals.

Personal Care Skills

_____ Put pajamas away (2–4)

_____ Pick up toys (2–6)

_____ Undress self (2–4)

_____ Comb hair (2–5)

_____ Wash face, hands (2–5)

_____ Brush teeth (2–5)

_____ Tidy up bedroom (2–8)

_____ Dress self (3–6)

_____ Make own bed (3–7)

_____ Clean, trim nails (5–10)

_____ Leave bathroom neat after use (6–10)

_____ Wash and dry own hair (7–10)

_____ Arrange for own haircuts (10–16)

_____ Purchase own grooming supplies (11–18)

Clothing Care Skills

_____ Empty hamper, put dirty clothes in wash area (4–8)

_____ Put away clean clothes (5–9)

_____ Clean own drawers (6–14)

_____ Clean own closet (6–16)

_____ Fold, separate clean laundry (8–16)

_____ Hang clothes for sun drying (8–16)

_____ Fold clothes neatly, without wrinkles (8–16)

_____ Polish shoes (8–18)

_____ Wash clothes in machine (9–16)

_____ Operate electric clothes dryer (9–16)

_____ Clean lint trap and washer filter (10–16)

_____ Shop for clothing (11–18)

_____ Basic spot removal—blood, oil, coffee, tea, soda, etc. (12–18)

_____ Waterproof shoes/boots (12–18)

_____ Iron clothing (12–18)

_____ Hand-wash lingerie or woolens (12–18)

_____ Simple mending—buttons and holes (12–17)

_____ Sort clothes by color, dirt, fabric content (8–18)

_____ Take clothes for dry cleaning

_____ Simple sewing (12–18)

Household Skills

_____ Clear off own place at table (2–5)

_____ Wipe up a spill (3–10)

_____ Dust furniture (3–12)

_____ Set table (3–7)

_____ Clear table (3–13)

_____ Pick up trash in yard (4–10)

_____ Shake area rugs (4–8)

_____ Spot-clean walls (4–12)

_____ Wipe off door frames (4–12)

_____ Clean TV screen and mirrors (4–8)

_____ Feed pets (5–10)

_____ Clean toilet (5–8)

_____ Scour sink and tub (5–12)

_____ Empty wastebaskets (4–10)

_____ Sweep porches, patios, walks (4–10)

_____ Wipe off chairs (6–11)

_____ Know differences and uses of various household cleaners (6–14)

_____ Load and turn on dishwasher (6–12)

_____ Empty dishwasher and put dishes away (6–12)

_____ Wash and dry dishes by hand (6–12)

_____ Clean combs, brushes (6–8)

_____ Clean bathroom (total) (6–12)

_____ Scrub or mop floor (6–13)

_____ Use vacuum cleaner (7–12)

_____ Clean pet cages and bowls (7–13)

_____ Take written telephone messages (7–12)

_____ Use broom, dustpan (8–12)

_____ Vacuum upholstery and drapes (8–14)

_____ Water house plants (8–14)

_____ Water grass (8–14)

_____ Fold blankets neatly (8–14)

_____ Wash car (8–16)

_____ Weed garden (9–13)

_____ Change bed linens (10–13)

_____ Replace light bulbs, understand wattage (10–15)

_____ Clean fireplace (10–15)

_____ Polish silverware (11–15)

_____ Replace fuse or know where breakers are (11–18)

_____ Oil squeaky door (12–18)

_____ Change vacuum belt and bag (12–15)

_____ Trim trees, shrubs (12–18)

_____ Mow lawn (12–16)

_____ Polish wood furniture (14–18)

_____ Wash windows (13–18)

_____ Place long distance calls (13–17)

_____ Place collect calls (13–18)

_____ Unstop a drain with chemicals or plunger (13–18)

_____ Install a lock (14–18)

_____ Change plug on electric cord (14–18)

_____ Scrub down walls (14–18)

_____ Wax a floor (14–18)

_____ Clean bathroom tile (14–18)

_____ Replace faucet washer (15–18)

_____ Use weather and all-purpose caulking (16–18)

_____ Know what to look for in home appliances (16–18)

Cooking Skills

_____ Know basic food groups and nutrition (5–14)

_____ Put groceries away (6–16)

_____ Make punch (6–9)

_____ Make a sandwich (6–12)

_____ Cook canned soup (7–12)

_____ Read a recipe (7–12)

_____ Measure properly (7–14)

_____ Make gelatin (7–12)

_____ Pack a cold lunch (7–12)

_____ Boil eggs (7–13)

_____ Scramble eggs (9–13)

_____ Distinguish between good and spoiled foods (10–18)

_____ Bake a cake from a mix (10–14)

_____ Cook frozen, canned vegetables (10–13)

_____ Mix pancakes (10–17)

_____ Read ingredient labels wisely (10–15)

_____ Plan balanced meal (10–15)

_____ Select and prepare fresh fruits and vegetables (10–18)

_____ Bake cookies (10–16)

_____ Bake muffins, biscuits (11–17)

_____ Make tossed salad (11–15)

_____ Make hot beverages (12–16)

_____ Fry hamburger (12–16)

_____ Broil a steak (12–16)

_____ Bake bread (12–17)

_____ Make fruit salad (13–15)

_____ Clean frost-free refrigerator (12–18)

_____ Make casserole (14–18)

_____ Clean oven and stove (15–18)

_____ Carve meat (15–18)

_____ Plan and shop for groceries for a week (15–18)

_____ Defrost refrigerator or freezer (15–18)

_____ Cook a roast (15–18)

_____ Fry a chicken (16–18)

Money Skills

_____ Know monetary denominations; penny, dime, etc. (5–12)

_____ Freedom to use small allowance (5–12)

_____ Make change and count your change (8–11)

_____ Compare quality and prices (8–12)

_____ Make savings or checking account deposit (10–18)

_____ Use a simple budget (12–18)

_____ Return item to store properly (14–18)

_____ Write a check (14–18)

_____ Balance checkbook (14–18)

_____ Understand what household bills must be paid; rent, electricity, water, telephone, etc. (15–18)

_____ Know how to properly use credit card (16–18)

Navigation and Auto Skills

_____ Know address (4–6)

_____ Know phone number (4–6)

_____ Clean interior of car (8–14)

_____ Ride bus or taxi (8–16)

_____ Oil a bicycle (9–14)

_____ Repair bicycle tire (10–15)

_____ Wash car properly (10–17)

_____ Read a map (7–14)

_____ Polish car (12–17)

_____ Fill car with gas (15–18)

_____ Check oil (15–18)

_____ Fill radiator (16–18)

_____ Change flat tire (16–18)

_____ Fill tires with air (16–18)

_____ Drive car (16–18)

Other Skills

_____ Make emergency call such as ambulance, police, fire department (5–12)

_____ Learn to swim (5–14)

_____ Check book out of library (6–10)

_____ Know emergency first-aid procedures (10–18)

_____ Understand uses of medicine and seriousness of overuse (10–18)

_____ Plan a small party (12–18)

_____ Properly hang something on wall (12–18)

_____ Know differences between latex, enamel paint, wood stains, and polyurethane (12–18)

_____ Paint a room (12–18)

_____ Type (14–18)

_____ Change furnace or air conditioner filter (14–18)

_____ Contact landlord with problem and follow through (14–18)

_____ Organize spring house cleaning (15–18)

_____ Clean water heater and if gas, light it (16–18)

_____ Repair wall holes with putty (16–18)

_____ Shampoo carpets (16–18)

_____ Arrange for services such as trash removal or extermination

Additional Skills

_______

_______

_______

_______

_______

_______

_______

_______

MAKE PLANS TO REACH YOUR GOALS

Filling out the Home Progress Chart will clarify the skills your child has mastered, the skills that need strengthening, and other skills you want your child to have. Now that you know where to begin, it is time to set goals. Consider the child’s level of maturity: Can my child handle this skill physically, mentally, and emotionally? Consider the time demands: Is my child too busy for this with a heavy school schedule, dance or music recitals? Think about parental stress: Am I too tied up with overtime at work and the church social to organize? Remain flexible with the plans as circumstances change.

The school curriculum year, winter and spring breaks, and the longer summer vacation suggest possible scheduling boundaries and opportunities. During school, when children concentrate on studies, emphasize strengthening regular daily routines and simple one-day projects, like making a tossed salad or checking the oil in the car. Vacation times could be used to teach more complex skills like gardening, map reading, or sewing. In June, goals can be set and plans made for the skills you intend to integrate with summer fun. It helps to write down the plans for each child in the various categories like personal, household, money, and so forth. Use the back pages of this book or a special notebook for family goals.

Being aware of goals will help you take advantage of community organizations such as Scouts, 4-H, and their feeder groups. Jane can take sewing in 4-H. John can complete the Personal Management Merit Badge in Scouts, with its emphasis on money management. The programs of these groups are achievement orientated, so children benefit doubly, learning the skills taught and receiving goal-setting training.

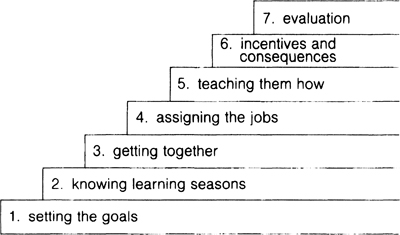

DEVELOP A REACHABLE GOAL

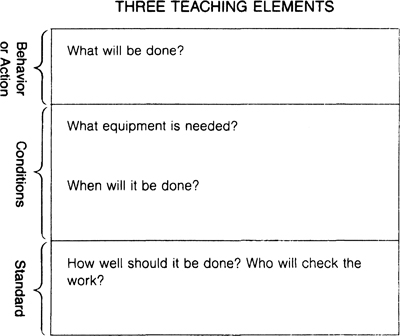

A beginning student teacher often complains about the tedious task of writing objectives for her new students. She soon learns, however, that the objective-writing process clarifies all dimensions of the goal. Later, this once burdensome chore becomes automatic. The new teacher learns that a goal is more attainable if it includes these three teaching elements: (1) desired behavior, (2) needed conditions, and (3) the expected standard. These three ingredients can apply in the home. You don’t have to write out objectives and lesson plans like a teacher, but if you have trouble meeting your goal, it may be helpful to go back over these factors to see if you have missed one.

The actions, conditions, and standards vary with the age of the child and the difficulty of the task. For instance, dusting an open-space room with modern-style furniture does not require the same maturity or skill as dusting a room filled with antiques and knickknacks. Regardless of the job, if the child knows what is expected, has the necessary equipment, understands the specific time when it is to be done, and knows what the end result must be, the success is almost guaranteed. If you say completely what you mean, the child will usually do it.

Using this chart will help you include the three teaching elements in the goals that you set.

GOAL-SETTING EXAMPLES

The following examples will clarify the effective use of the three teaching elements. Vicky decides that for her eight-year-old daughter, Shirley, setting the table, dusting the furniture, and weeding the flower beds are appropriate skills for the next three-month period. Since Vicky works full time, Saturdays will be her best training days. While driving home from a piano lesson Vicky says, “Shirley, you’ve been doing so many helpful things lately and doing them so well, I think you’re ready to learn something new. I have three tasks in mind. Which one do you feel ready to try first? Setting the table for our dinner, maybe with candles and flowers to make it really nice; weeding the flower bed in the front yard, working on a small area each week; or would you rather learn to dust the living room with the pine-scented spray polish?” Vicky makes the jobs sound as attractive as possible, then lets her daughter make the final choice. Because Vicky knew what skills her daughter needed to develop, she could direct the goal, making sure to include the three teaching elements.

Shirley decided to weed the flower beds, so a piece of string was used to section off a four-foot square. When she had pulled the weeds within the string, her job was finished. Mother worked with Shirley for the first two Saturdays, to insure that flowers were not pulled with the weeds. After five weeks, the flower beds looked beautiful and needed only slight weeding each Saturday. Vicky told Shirley how lovely the flowers looked and what a fine job she was doing, occasionally working with her for a few minutes to make the job more enjoyable.

* * *

Let us suppose that you are setting goals for a ten-year-old boy. He does quite well with personal grooming and is willing to do little jobs, like setting the table and vacuuming, but his bedroom is a mess and he has expressed interest in cooking. The two basic goals are to help him get control of his bedroom and to learn some basic cooking skills. Set two or three short-range, specific goals that can be accomplished in about a month. The trick is to set workable tasks by asking, “What little things can be done to draw closer to these main goals?” The goals might be things like:

Bedroom

• Make a progress chart for bed making and room pick-up.

• Give adult help once a week.

• Paint his bedroom.

• Move the sewing machine and fabrics out of his room.

Kitchen

• Make tuna fish sandwiches together.

• Prepare a lettuce salad with him.

• Direct him in making a cake from a mix.

As you discuss these goals, be sure to include the three teaching elements, so you and he both clearly understand what’s expected, what is needed, and when he will do these things. Remember, this can be done formally on paper or informally in your discussion.

Continue setting goals. Most people set weekly and monthly goals at work, so why not at home? Now that you have a long-range goal of getting your children to work at home, you can set yearly and seasonal goals: “This summer I’ll start teaching my daughter to sew.” Include the child in these decisions. As adults, if we don’t like something, we bag it. If we don’t like singing, we don’t sing in the choir. But children don’t have the same privileges—they have to eat what is fixed for dinner, study the curriculum dictated by the school, and go to bed when parents say. If it’s spelling they don’t like, we tell them they need to work harder at it. These years can be difficult for the child. Whenever possible, allow the child to give as much input as is appropriate for his or her age.

Try to involve the child in setting individual goals. One father asks his children every Friday night, “What are your goals this weekend?” He says it has taken several months, but they have quit watching so much television and now are working on the things they “really” want to do. Talents are “interests” that have been nurtured; goal setting will help talents grow.

As you read this book, don’t feel guilty because your kids aren’t doing all you want them to do. There is no utopia, not even at the Monson or McCullough house. If you think our kids don’t need prompting, don’t procrastinate, or don’t try to get out of work, you have the wrong impression. There is a time to crack down on laziness and carelessness. Sometimes we wonder what other people think when we tell them we’re writing about getting children to work at home. These people have been in our homes when they were not clean, when we had to prompt our children to get busy. That’s why there are so few books on this topic; most of those who write don’t have kids and those who do have kids can’t get them to work. By having a clear set of goals and working on them one at a time, we can stop worrying about everything at once. Goals cut down stress. But there are little moments when our children do things and we can see progress; like the first time Melea made a perfect sunny-side-up egg or when Wes said, “Let me wash the car for you, Mom.” It’s a good feeling when we go to parent-teacher conferences at school and the teachers say our children aren’t afraid to speak in front of the class or that they are not fearful of new projects. Our children have not reached perfection, but they are not Annies either. This process of setting goals is fun and rewarding.

Children need much practice in each skill, sometimes even going back at a later point to relearn. Provide numerous opportunities: “I need to finish this painting before the storm hits, Charlie, so could you please make sandwiches for lunch?” They also need to learn to be consistent about a new responsibility. That’s when a star chart or other means of visual feedback is helpful. Remember, the most important school your child will ever attend is your home. Give praise and encouragement freely, being grateful for small accomplishments. Self-esteem comes through finding a set of competencies. “Shirley, when you weed the flower beds, I feel like I have another woman helping me!” Listen as your child expresses feelings of frustration or success. Build on past successes, as you encourage them to meet future goals.

In a third grade classroom, the teacher taped a sign on the wall: “Hook your wagon to a star, take your seat and there you are.” Goal setting is not quite that simple. Driving the team can be pretty hard work, but at least you have something by which to steer. Goal setting is the first step toward independence and responsibility. It will help make good times better and bad times better, too.