CHAPTER 2

“This Is Not What I Expected”

Parenting Complex Kids Is Different

“A good environment allows the best things in us to manifest. A toxic environment can bring out the worst things in us.” —THICH NHAT HANH

Common (but Unhelpful) Parenting Reactions

When life throws you curveballs, don’t keep swinging at the problem without changing your approach. Although there is no single “right” way to parent, there are definitely some approaches that aren’t optimal and can even make things more difficult for everyone, including you.

Here are some less than optimal ways that parents typically respond when raising complex kids. Sometimes these approaches work, which is seductive; over time, though, they usually create friction. If you’ve already put a lot of effort into trying to help your kid—by reading books, going to doctors, maybe even taking a parenting class—this section can give you an understanding of why things haven’t worked yet. (You can also try the Parenting Style Quiz at impactparents.com/help-for-parents/parenting-style-quiz/.) The rest of this chapter will offer ways to shift to a new approach.

Angry Ann and Angry Andy: You get angry and lose your temper all too often, even though you don’t want to. It’s all so frustrating. Whatever you do, it never seems to be enough. You feel like you can’t get a break. You say, “I feel like I’m always yelling, but it’s not my style.”

Angry Ann and

Super-Parent Sue: You keep the balls in the air. You look like you have things under control, but you’re doing too much and it’s not sustainable. You want others to step up and do their fair share, but you don’t make the time or help them learn how. Secretly, you’d rather do it yourself, though you still complain, “I’m doing it all, but this is just too much!”

Super-Parent Sue

Lost Lois: You feel alone, surrounded by people who don’t understand what you’re going through. You’re doing all you can to support your kids, keep your house running smoothly, and manage everyone’s needs. You’ve lost any direction for yourself and feel like you’re running in circles. You say, “I don’t know what to do. I feel lost and lonely.”

Lost Lois

Maxed-Out Maxine: You’re overwhelmed and don’t know how to handle it anymore. Nothing seems to work, and honestly, you’re tired of trying. You want to be a good parent, but sometimes you feel like giving up. You want to do something—anything—to make things different! You say, “I’m exhausted. How long can I keep this up?”

Maxed-Out Maxine

Fix-It Fran: You’ve tried everything imaginable to help your child. You ping-pong from one thing to another, determined to find a solution that works. You see what needs to be done and frequently give your child systems to use (though they rarely do). You say, “I’ll do whatever it takes to help my child.”

Fix-It Fran

Nagging Nan: You’re constantly reminding your kids to do everything they’re responsible for and finding things for them to do, just to make sure they’re doing something. Your kids are frequently annoyed with you and want you to leave them alone. You say, “If I don’t remind them, it won’t get done.”

Nagging Nan

Anxious Ava: You’re always worried about what isn’t getting done or what might go wrong. You catastrophize and fret that you or your coparent are not doing enough as parents. You manage your anxiety by planning and trying to get everyone to follow every little structure you put in place. You say, “I’m worried about what might happen.”

Anxious Ava

Pushover Pat: You’re kind and caring. You don’t set limits, but when you do, you don’t usually follow through with them. You don’t like the way family members talk to you, but you don’t know how to change it. You just want the family to get along and feel safe, but someone’s always upset. You say, “I just want everyone to be happy.”

Pushover Pat

Denying Dale: You have a wait-and-see attitude. You believe that if your child would apply themselves, things would be fine. You’re waiting for them to grow out of this stage. You don’t want them evaluated because you’re concerned about “stigma.” You resist a diagnosis because you don’t want it used as an excuse for poor behavior. You say, “He must learn to do what he’s told.”

Denying Dale

Playful Dave: You love to play with your kids and are the fun parent. When your spouse (or ex) tries to talk about problems, you don’t have much to say—things aren’t really that bad. You’re glad you don’t have to do the “heavy lifting” of parenting, but don’t think you get enough credit for keeping things light. You say, “I don’t know what you’re so worried about.”

Playful Dave

Distant Dan: You want to be positive, but you’re constantly disappointed and you don’t feel like you have much say in the matter, anyway. You didn’t expect parenting to require so much from you, and sometimes you feel like throwing in the towel. You say, “Why can’t they just do what’s expected of them?”

Distant Dan

Demanding Randy: You have high expectations of your children, setting the bar high so they can’t reach their full potential. You accept that your child has challenges but don’t want them used as an excuse. You think your coparent is coddling, despite kids needing to overcome challenges to be successful. You say, “You need to do what’s expected of you.”

Demanding Randy

Defensive Drew: You care about being a good parent and want others to see you that way. You see kids’ respect and obedience as a reflection on you, so you tend to take things personally. If you feel disrespected, you may lash out in blame; if ashamed, you may avoid conflict or embarrassment. You say, “You can’t talk to me that way” or, “It’s not my fault.”

Defensive Drew

Bootstrap Bill: You didn’t have an easy path as a child, but you turned out okay. The school of hard knocks worked for you, and you believe it’ll work for your kids too. They need to learn to suck it up and do what’s expected of them. Sure, it’s hard, but they have to push through and live with disappointment. You say, “Kids have to learn that life isn’t fair.”

Bootstrap Bill

Coach’s Reframe: Up Until Now

A number of years ago, I lost a lot of weight. I never went on a diet. I didn’t read any books. In fact, after three kids, I had decided to accept my middle-aged body for what it was—about 25 pounds overweight. I decided to stop worrying about my weight.

Instead, I focused on getting healthy, one minor change at a time. After all, what we pay attention to grows (or shrinks, in this case). I lost more than 30 pounds simply by focusing on making healthy choices and choosing to start fresh each day.

Lasting change happens when we shift our perspective and face forward toward the future, focusing on what lies ahead of us, instead of what has happened in the past—up until now. This is true of all kinds of parents.

If you’re a neurotypical parent with your executive function skills intact, it can seem mind boggling that others don’t approach things as clearly, methodically, or efficiently as you do. You do research, consult experts, and create systems to get things under control; or maybe you double down on discipline.

If you’re a complex parent yourself, you’ve likely been struggling through years of strife, trying to manage everything. It’s seriously daunting as you’re called upon to make complex medical decisions surrounded by stigma and misinformation (see Chapter 5). Parenting feels like a Jenga game of waiting, expecting all the pieces to come tumbling down.

Either way, when you focus only on what’s wrong, it’s hard to find a path to something that feels right. It’s almost impossible to make sustainable change in life without shifting your underlying thoughts or mindset. And that brings us back to three key words: Up Until Now.

There is nothing you can change about anything that has happened in your life up until now. School issues. Relationship dynamics. Arguments. Embarrassing moments. Choices you regret. You can’t change anything from the past.

The beauty of this moment is that you have the power to change what happens from here forward. Up until now, you did the best you could with what was available to you. Maybe you tried to get support for your family. Maybe you followed advice from friends, family, and professionals, even if it didn’t always get results.

From here, you have an opportunity to start fresh. Armed with the peaceful arsenal of tools and strategies in this book, you can take on a new perspective. You have a chance to try again.

Making choices is what life is all about. Fundamentally, everything is a choice, even when it feels like you don’t have one. Every action, every inaction, every conversation started, and every talk avoided is a choice.

Creating change is not just about finding the next action. It’s about becoming aware of the choices you’re making every day, choices that are influenced by your thoughts and the words you tell yourself.

The beauty of this moment is that you have the power to change what happens … from here forward.

Because you are making choices every moment of every day, the up-until-now perspective can free you up to make decisions that lead to genuine and lasting change. It’s based on awareness of the choices you’re making, a shift in perspective about what’s possible, and the belief that you can influence the circumstances that are causing challenges in your life.

Up until now, change may not have seemed possible; now it’s up to you.

Strategy: Consciously Manage Triggers (Four Steps to Escaping the Stress Cycle)

Do you struggle to stay calm when you or someone around you makes a simple (albeit significant) mistake? Is it hard to keep your cool when your kids lose theirs?

We all lose it sometimes. It’s human nature to surrender to a meltdown or explosion when pushed past our limit. Sometimes it works to get people’s attention, but it’s counterproductive, long term.

Overreacting only teaches kids that it’s okay to go all drama-queen when things don’t go their way. When you’re upset, how you respond sets the stage for how kids learn to handle upsetting situations. Yelling might get them to do chores, but it won’t teach them to take responsibility or manage big emotions. And it definitely makes it harder for them to focus on homework.

When you’re at the brink of breaking, it takes Herculean effort to model self-control, to be the “grown-up” when things get triggered. As you learn to keep cool and focus on calming down, it shifts the pattern for everyone in the household.

Here’s how you can get started:

FOUR STEPS TO ESCAPING THE STRESS CYCLE

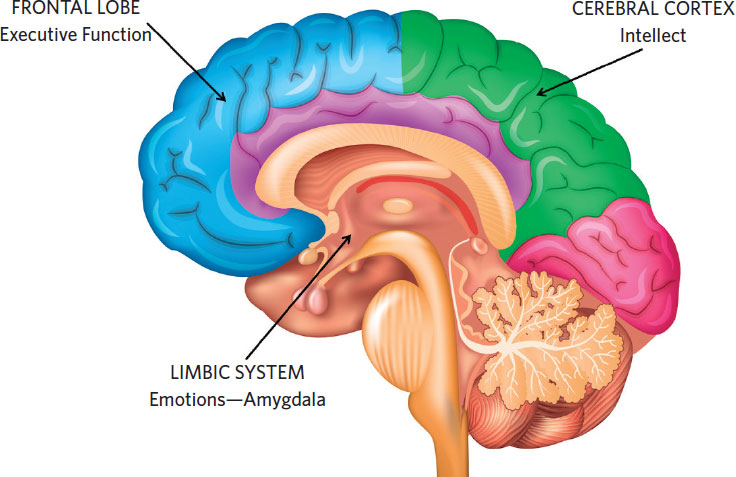

1. Recognize when someone’s brain is triggered. According to the American Institute of Stress, more than 70 percent of people say they “regularly experience” symptoms “caused by stress,” so you likely know what stress feels like. During stress, the primitive brain operates as if there’s a sabretooth tiger at the cave, taking over the frontal lobe with amygdala hijack, a term that describes a “fight, flight, or freeze” response, coined by Daniel Goleman in his 1995 book Emotional Intelligence. This is helpful when avoiding a car accident by hitting the brakes, but not helpful if you get triggered whenever a teacher sends an email. When things get heated, notice if someone’s getting triggered (arguing or defensive).

2. Reclaim the brain from amygdala hijack. Immediately focus on calming things down and avoid pushing anyone over the edge. Like turning off sirens when you know there’s been a false alarm, reclaim the brain by taking deep breaths, taking walks, sipping water, going for a run, watching a funny video, petting the dog, etc. (Yes, sipping water! It sends a message to the primitive brain, as if you were at a watering hole, that it’s safe.) This may take time, so beware of “fake calm” (such as three shallow breaths followed by, “Okay, I’m calm now.”) Take time to really calm down with humor and patience.

3. Make up a new story that works for you. The stories we tell ourselves can be harmful or helpful; set us up for failure or success; freak us out or calm us down. Make up a helpful story that you can believe. For example, thinking “this 7-year-old is a brat,” will lead you to treat him like he’s purposefully obnoxious. But telling yourself “he’s embarrassed” or “this scared little boy needs encouragement” can lead to compassion.

A client’s extremely anxious 11-year-old daughter begged to play hockey with the boys, but then resisted going to practice. Her mom felt manipulated; but when asked, “what else is true?” she realized, “The fear is real for her. She’s not trying to be difficult. She wants to play, but she’s terrified.” The new story paved a path to better understanding, connection, and outcomes.

4. Take action based on the new story. Once that mom saw a reasonable explanation for her daughter’s behavior, they worked together to negotiate attendance at hockey practices, slowly helping her daughter find ways to participate. It was a huge breakthrough.

Escaping the stress cycle can take time to learn to manage, so give yourself some grace in the process. I recall one afternoon when unloading the dishwasher became a huge fight. I was trying to help my child calm down and my husband thought I was letting them off the hook. He struggled with my approach, arguing “It’s their job and it needs to get done now.” I was between a rock and a hard place. I knew that keeping them from going over the edge was more important than getting the dishes put away, but it was hard to articulate that in a way he could accept. Quietly and calmly I explained, “please trust me; they need to calm down first,” removing myself until we could all allow calmer heads to prevail.

Say No to Denial

We knew my eldest was complex starting at two weeks (cholic), then at two years (allergies), then four (learning), then six (emotional). We addressed each health development individually. But to be honest, they were eight (with a list of about 8 diagnoses) before I accepted that they had “special needs.” I didn’t begin to understand the full impact of what that meant until they were 10 years old.

I thought I was addressing their problems every step of the way. In some ways, I was. There were therapies and doctors and specialists galore. But for many years I was busying myself with the details, missing the big picture. Swimming deep in the waters of denial, lost in the current, I just kept believing that it was enough that I knew how to swim.

To guide your kids to safety and success, acknowledge their challenges (and your own) and tackle them head on.

Ever feel like you’re stuck in the muddy river of denial? On one level, you know something’s going on that needs your attention; on another level, you’d like to pretend it doesn’t exist. Most of us begin that way, to be honest. Ideally we start to snap out of it once we realize our kids need our help.

For me, maybe I wanted to make sure things turned out as I had planned—to hold on to my dreams for my child’s future (and my own). Maybe I was holding tight because I was afraid to lose control completely. But whatever I was doing clearly wasn’t working. It took a decade to understand that to stay true to my larger vision of raising a healthy, independent child, I needed to change my mindset and approach things differently.

SOME SIGNS OF DENIAL

Do you try to protect your kids, thinking things such as

• I don’t want the stigma of a “label.”

• Maybe it’s a phase. I’ll wait, hope, and “normalize” life until they grow out of it.

• I won’t tell them, so they won’t use their diagnosis as an excuse.

• I don’t want them to think anything is wrong with them.

Do you try to protect yourself, thinking things such as

• I’m already overwhelmed. I can’t handle anything else.

• There’s nothing wrong with my child. I’m a good parent.

• I can fix this before it becomes a real problem.

• I’m doing everything the experts suggest, so it will be okay.

To guide your kids to safety and success, it’s best to acknowledge their challenges (and your own) and tackle them head on.

Given the challenges our kids face, it’s hard enough to guide them to follow their path and develop a vision for themselves. It’s nearly impossible when we convince ourselves that there’s nothing fundamental that needs to be addressed.

The greatest gift you can give yourself and your complex child, is to acknowledge that whatever issue your child is facing is one of those bumps on your parenting journey that requires course correction. It’s not a barrier, but it calls for careful navigation.

You do not have to abandon your goals and dreams when you accept that things aren’t going as planned. In fact, hold fast to your dreams! They will serve you and your child extremely well.

But you don’t have to stay stuck in the muddy river of denial either. It’s scary down there in the muck. When you accept and acknowledge that something’s going on that needs your attention, you’ll be able to climb out to safety—and get the help you need to steer clear of the obstacles that threaten your child’s path, so you can navigate to success.

Say Yes to Forgiveness

It was a Monday morning. I was trying to get the kids moving when I heard my husband shout, “Everyone, get shoes on and get outside—NOW!”

He got my attention. He was calm, but I could tell something was urgent. Wait, why was he even still at home? I called out and he responded, “I’ve had an ADHD moment and I need some help, please.” His voice was strained. Wow. I secretly gave him points for keeping cool, though I was definitely getting nervous!

I went outside to assess the situation. It was like a scene from Stephen King’s Christine. Two headlights stared out at me from the woods, taunting me. My husband’s Prius was halfway down the hill, mere inches from a giant oak tree and our neighbor’s wooden fence.

I went back inside to rally the troops. I covered up my white blouse, because things were likely to get messy. I asked everyone to put on closed-toed shoes and long pants—gotta be specific with complex kids. I figured the snakes were already pretty mad.

We came together as a team to push the car out of the woods. It was touch-and-go for a minute, but soon she was out of danger. Within five minutes, the drama was over, everyone was back in their own space, my shirt was clean, and my husband was headed to his meeting. We all handled it like rock stars.

In the world of complex kids, every day feels a little like that Monday morning:

• There is excitement and enthusiasm. Adrenaline is pumping, and we respond to life’s adventures with excessive energy. On a good day, we do it with excellent humor as well.

• With unexpected surprises, there can be a serious need for forgiveness. We make simple mistakes a lot—the natural consequence of the marriage of impulsivity and inattention. I know everyone makes mistakes, but we do it bigger, better, and more often.

Striking the balance between jumping to action and managing the agony of defeat is the art of living well with complex kids.

No matter how many strategies we put into place, we’re going to have those “ADHD moments.” We’re going to miss an appointment, forget a school carpool, or overreact and lose our temper. We’re human. When we do, forgiveness (for ourselves and each other) is just as important as responsiveness. Maybe even more.

This story is a classic example: Running late for a meeting, my husband turned on the car in the garage, put it into reverse to back out, and remembered he left something in the house. After running back inside, he returned to find the car halfway across the driveway on its way down the hill. He hadn’t heard the Prius, which started to move when the gas engine kicked in. It was an honest mistake.

You do not have to abandon your goals and dreams when you accept that things aren’t going as planned.

Thankfully, and miraculously, no one was hurt; nothing was really damaged except a few scratches and a little pride.

But not a lot of pride. Instead of beating himself up, my husband handled the situation beautifully. He responded quickly, got the help he needed, stayed calm, kept his sense of humor, and let it go when the crisis was past. I’m sure he got a little red in the face when he arrived late to his meeting, but at least he had a great story to tell. He did a masterful job of modeling self-forgiveness for his colleagues and his family.

When mistakes happen—and they will—try to hold them lightly. Practice radical forgiveness. And remember to keep your sense of humor. Who knows, maybe the next car to lurch independently out of the garage will be yours!

Self-Talk: Put the Stick Down

During one summertime family supper, we were eating late, and it was unusually chaotic:

• My middle child wanted one food at a time on her plate.

• My youngest talked incessantly, eating the crumbly chicken topping with his fingers.

• My eldest cracked jokes, entertaining and riling the rest, shoveling in food so fast we wondered if they breathed at all.

There was lively conversation, some mild bickering about who got to talk first, and an equal amount of laughter and playfulness. And there was an unbelievable amount of movement.

I reflected on my childhood, when we ate proper dinners in the dining room, sat up tall in our chairs, and said, “Yes, ma’am” and “Yes, sir” without reminder. Our fingers did not touch the plate. It was interesting—intelligent humor was rewarded—but not exactly lively fun. Formal family dinners had defined my expectations for parenting success.

I had beaten myself up for years because our family’s dinners were not “respectable” enough and my household was generally chaotic. That night, looking around, I laughed out loud. My son had climbed onto his sister’s back and then returned to his seat for second helpings.

I asked, “Could any of you imagine doing this at Grandpa’s house?” Peals of laughter.

In an instant, I appreciated and reveled in the joyous time my family was having. We were loud, rambunctious, and a little wacky, having a blast making memories that foster a lifetime of connection. And I realized that fun is more important to me than propriety.

It was time to put the stick down. I wanted my adult kids to remember connecting, playing, loving, knowing, and accepting each other during family dinners—and I wanted to give myself permission to fully appreciate it. For me, that was success.

Sometimes we make mistakes. We lose our cool, don’t handle something as well as we’d like, miss a flight, or forget to pack something important for a trip. Sometimes our kids don’t behave as we’d like—bouncing off the walls or melting down. Often, we take these situations personally and beat ourselves up.

But you can reframe self-criticism, bring yourself a little compassion, and practice putting the stick down. Chances are, you’ve been doing the best you can; and although you can’t change the past, your mindset will most assuredly define your future.

Are you going to do everything perfectly from here forward? Nope. But can you imagine how much better you’ll do if you stop beating yourself up for whatever might be less than perfect from the past (that is, about a minute ago)?

When the chaos reaches a crescendo, I still get frustrated and long for the reserve of my youth. But that family dinner was a turning point for me. If my family needs dinnertime to be an aerobic activity, I decided to be okay with that. Although I remain a stickler for “yes, ma’am” (a Southern sign of respect), I’ve let go of the “shoulds” I beat myself up with for years.

Chances are, you’ve been doing the best you can; and although you can’t change the past, your mindset will most assuredly define your future.

We need to give ourselves permission to have moments of imperfection and handle those moments with grace and a little self-love. When my kids are being their boisterous, creative, funny selves, I want them to feel accepted, not scolded. They’re going to need that feeling when they get out there in the big world.

So I want to encourage you to put the stick down. Beating yourself up is not going to help things get any better and it stands in the way of your enjoying the relationships you have. Whenever you notice that life is slipping out of control, that your well-laid-out plans aren’t working, or that you could have handled something better, put the stick down. Dance with whatever’s happening. It turns out, self-forgiveness will help you accept the things you cannot change.

Questions for Self-Discovery

• Which parenting styles do you relate to?

• What stories can you replace with up until now?

• What are signs you’re getting triggered? How do you reclaim your brain?

• Are there ways you’re still in denial?

• What’s important about forgiveness in your story?

• How do you tend to beat yourself up?