1

What Is Postpositivism?

When I find myself in the company of scientists, I feel like a shabby curate who has strayed by mistake into a drawing-room full of dukes.

W. H. Auden

Poet W. H. Auden penned these words almost four decades ago, in an age that is long gone. Physicists and other natural scientists may still be regarded with awe, but there can be little doubt that social scientists have fallen from their pedestal—if ever they occupied one! For the intervening decades have seen the rise to popularity of philosophical views that challenge the status of science as a knowledge-producing enterprise, and social scientists and educational researchers have been particularly vulnerable to these attacks. Scientists—according to these views—are no less human, and no less biased and lacking in objectivity, than anyone else; they work within frameworks that are just that: frameworks. And, these critics suggest, none of these frames or paradigms, considered as a whole unit, is more justified from the outside than any other. Philosopher Paul Feyerabend even argued that the modern scientific worldview is no more externally validated than medieval witchcraft, and the prophet of postmodernism, Jean-Francois Lyotard, held that we should be “incredulous” about the story that is told to justify science as a knowledge-making frame (its justificatory “metanarrative,” as he termed it). If this general line of criticism is true of physics or medicine, it certainly should be true of social science, in which the values and cultural background of the researcher seem to play a more pervasive role. Thus a key question arises: Can this line of criticism, particularly in the case of educational research, be met? The present book is dedicated, if not to restoring social scientists and educational researchers to their pedestal, then at least to raising them above the mire. They may never be members of the nobility, but perhaps they can be located in the ranks of those with a modicum of respectability!

Educational researchers constitute a community of inquirers. Doing the best they can and (at their best) ever alert to improving their efforts, they seek enlightenment or understanding on issues and problems that are of great social significance. Other things being equal, does lowering class size for students in the lower elementary grades improve their learning of math and reading? Does it have an effect on their development of a positive self-image? Does bilingual education enable “language minority” students (or at least a significant number of them) to master English while maintaining their progress in other subjects such as science, math, and history? What are the features of successful bilingual programs? Are whole language approaches to the teaching of reading more successful than the phonics approach (and if so, in what respects)? Does either of these approaches have serious, unintended side effects? What effects do single-sex schools have on the math and science attainment of female students? Do they have other effects of which policy makers (and parents and teachers) ought to be aware? Does the TV program Sesame Street successfully teach young viewers such things as the alphabet, counting skills, and color concepts? Is it more successful than the instruction children can get from parents who, say, read books to them regularly? Does this program have an impact on the so-called achievement gap that opens up at an early age between many children from impoverished inner-city backgrounds and those from well-off middle-class suburban homes? Do Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development apply to girls as well as to the boys whom Kohlberg studied? (Do they even hold true of boys?) Are multi-ability classrooms less or more effective in promoting learning of academic content than “streamed” classrooms? (And do they have positive or negative “social” and “psychological” effects on the students?) Are individual memories of childhood abuse (sexual or other), which are “recovered” many years later, to be trusted? Society generally, and educational practitioners and policy makers in particular, want to be guided by reliable answers to these and many other questions.

Many of us may have strong opinions about some of these issues; indeed, beliefs may be so strongly or fervently held that it seems inappropriate to call them merely “opinions”—we are convinced that our views are right. It is crucial for the theme of this book, however, to recognize that beliefs can be false beliefs. What appears to be enlightenment can be false enlightenment. Understanding can be misunderstanding. A position that one fervently believes to be true—even to be obviously true—may in fact be false. Oliver Cromwell, the leader of the Roundheads in Britain (who executed King Charles I) and himself something of a fanatic, put this thought in memorable language: “My brethren, by the bowels of Christ I beseech you, bethink that you might be mistaken” (cited in Curtis and Greenslet 1962, 42). But unfortunately he apparently did not apply this moral to himself! Humorist H. L. Mencken put it a little less solemnly: “The most costly of all follies is to believe passionately in the palpably not true. It is the chief occupation of mankind” (cited in Winokur 1987, 31).

If researchers are to contribute to the improvement of education—to the improvement of educational policies and educational practices—they need to raise their sights a little higher than expressing their fervent beliefs or feelings of personal enlightenment, no matter how compelling these beliefs are felt to be. They need to aspire to something a little stronger, seeking beliefs that (1) have been generated through rigorous inquiry and (2) are likely to be true; in short, they need to seek knowledge. This aim is what the philosopher Karl Popper and others have called a “regulative ideal” for it is an aim that should govern or regulate our inquiries—even though we all know that knowledge is elusive and that we might sometimes end up wrongly accepting some doctrine or finding as true when it is not. The fact that we are fallible is no criticism of the validity of the ideal because even failing to find an answer, or finding that an answer we have accepted in the past is mistaken, is itself an advance in knowledge. Questing for truth and knowledge about important matters may end in failure, but to give up the quest is knowingly to settle for beliefs that will almost certainly be defective. And there is this strong incentive to keep the quest alive: if we keep trying, we will eventually discover whether or not the beliefs we have accepted are defective, for the quest for knowledge is to a considerable extent “self-corrective.” (Do many of us doubt that present-day theories about the causal agents in infectious diseases are an advance over the theories of 50 or 150 years ago, or that many of the errors in these past views have been eliminated? Does the failure of a particular medical “discovery” or treatment, at a given point in time, invalidate the longer-term process of exploration and experimentation?)

Accepting this pursuit of knowledge does not necessitate a commitment to a claim of “absolute truth” or its attainability. Popper, for one, believed that “absolute truth” was never going to be attained by human beings, and John Dewey put it well when, in his book Logic: The Theory of Inquiry (1938), he suggested substituting the expression “warranted assertibility” for “truth.” (The notion of a “warrant” has its home in the legal sphere, where a warrant is an authorization to take some action, e.g., to conduct a search; to obtain a warrant the investigator has to convince a judge that there is sufficient evidence to make the search reasonable. If the investigator needed to have “absolute” evidence in order to get a warrant, there would be no need for him or her to conduct a further search at all!) Dewey’s point was that we must seek beliefs that are well warranted (in more conventional language, beliefs that are strongly enough supported to be confidently acted on), for of course false beliefs are likely to let us down when we act on them to solve the problems that face us! It serves no useful purpose for an education or social science researcher to convey his or her “understandings” of the causes of a problem (say, the failure of students in a pilot program to learn what they were expected to have learned) to a policy maker or an educational reformer or a school principal, if indeed those understandings are faulty. The crucial question, of course, is how researchers are to provide the necessary warrant to support the claim that their understandings can reasonably be taken to constitute knowledge rather than false belief. Dewey gave us a clue, but it is only that—his answer needs substantial fleshing out: Authorized conviction (i.e., well-warranted belief), he stated, comes from “competent inquiries” (Dewey 1966, 8-9). And he wrote:

We know that some methods of inquiry are better than others in just the same way in which we know that some methods of surgery, farming, road-making, navigating, or what-not are better than others. It does not follow in any of these cases that the “better” methods are ideally perfect.... we ascertain how and why certain means and agencies have provided warrantably assertible conclusions, while others have not and cannot do so. (p. 104)

It is the purpose of this present volume to develop, at least in outline, the case that postpositivistic philosophy of science is the theoretical framework that offers the best hope for achieving Dewey’s goal, which is—or should be—the goal of all members of the educational research community. For, after all, who among us wants to aspire to unauthorized conviction? Who wants to knowingly carry out incompetent inquiries? Who wants to hold unwarranted beliefs? Who wants to adopt methods and approaches that cannot achieve the degree of reliable belief to which we aspire as we try to improve education? And if we want to criticize particular research findings or claims as being biased, untrue, or misleading, how is that to be done in the absence of some notion of competent, reliable, evidence-based research?

What, then, is postpositivism? Clearly, as the prefix “post” suggests, it is a position that arose historically after positivism and replaced it. Understanding the significance of this requires an appreciation of what positivism was and why it was (and deserved to be) replaced. “Postpositivism” is not a happy label (it is never a good idea to use a label that incorporates an older and defective viewpoint) but it does mark the fact that out of the ruins of the collapsed positivistic approach, a new (if diverse and less unified) approach has developed. It is to the elucidation of these matters that the discussion must now turn.

THE POSITIVISTIC ACCOUNT OF SCIENCE

Recently, one of the authors of this book was in deep discussion with a friend from another university—a professor of psychology who frequently writes on methodological matters. The quotation from Auden was mentioned, and the discussion turned to why scientists have fallen from their pedestal. “Surely it has something to do with the rise of postmodernism,” our intrepid coauthor suggested. “Perhaps,” responded the psychologist, “but I think it is simpler than that. I believe the average person identifies science, especially in the social and educational spheres, with positivism. And because the news has gotten out that positivism is seriously flawed, the reputation of social science has suffered!”

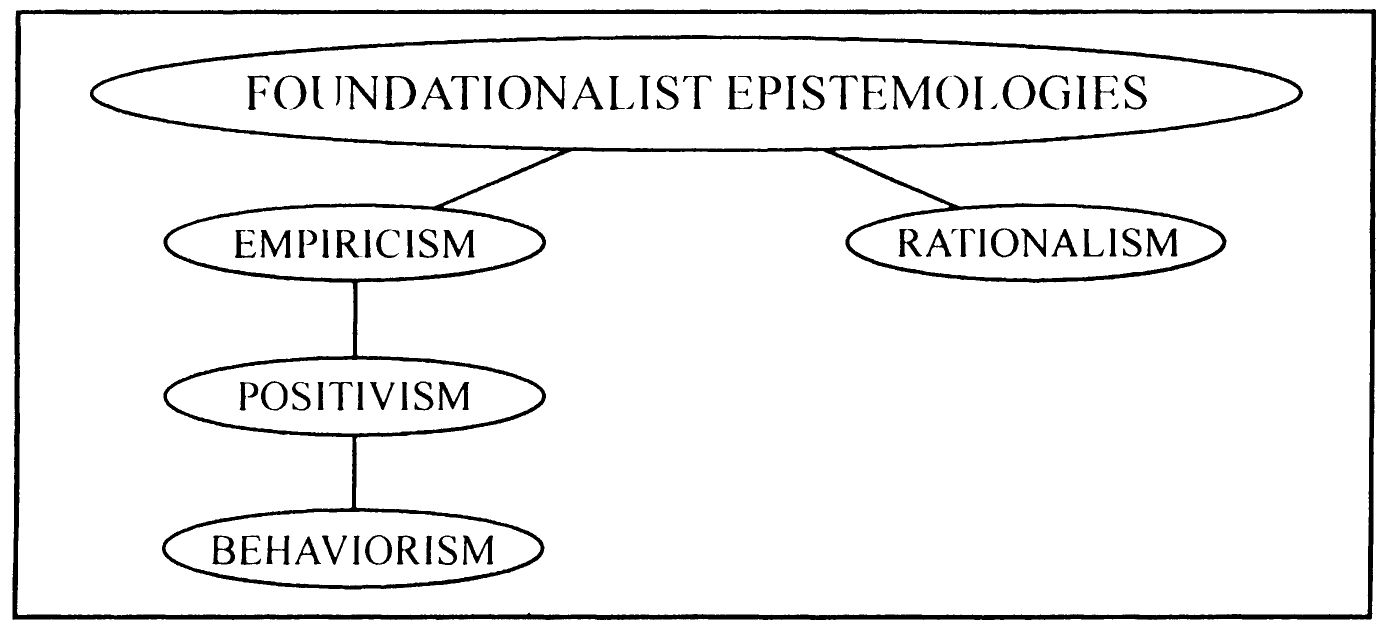

Figure 1.1. Foundationalist Epistemologies

Perhaps the psychologist was right. Certainly the image of research that has been presented in social science textbooks over the past four or more decades has been predominantly positivistic in orientation (the vast majority of texts on educational and psychological research have had—almost by mandate—a chapter addressing the nature of “scientific inquiry”). They have maintained this orientation in spite of the fact that for about the same period the philosophical flaws of this position were well known to (and widely discussed by) philosophers and others. The spread of positivism among researchers, and those who trained them, was facilitated by the influence of perhaps the best-known researcher in education-related areas for several decades, the behaviorist psychologist B. F. Skinner. His orientation was in all essential details straightforwardly positivistic. (In graduate school Skinner had read—and was influenced by—the philosophers who founded positivism.)

To philosophers, positivism (including behaviorism) is a form of empiricism; and empiricism in turn is one of two forms of foundationalist philosophy. The problems faced by positivism are merely variants of the problems that have surfaced with respect to foundationalism. The following schematic should make the relationships clear.

Foundationalism

Until the end of the nineteenth century, all major Western philosophical theories of knowledge (“epistemologies”) were foundationalist. It seemed obvious that to be labeled as “knowledge,” an item had to be securely established, and it seemed equally obvious that this was to be done by showing that the item (the belief or knowledge claim) had a secure foundation. The great French philosopher René Descartes reflected this common orientation (and also, incidentally, recognized that many of the beliefs we hold actually are false beliefs) when he wrote in the opening lines of his famous Meditations (1641):

Several years have now elapsed since I first became aware that I had accepted, even from my youth, many false opinions for true, and that consequently what I afterwards based on such principles was highly doubtful; and from that time I was convinced of the necessity of undertaking once in my life to rid myself of all the opinions I had adopted, and of commencing anew the work of building front the foundation, if I desired to establish a firm and abiding superstructure of the sciences. (Descartes 1953, 79; emphasis added)

But in order to “rebuild,” he first had to identify the “foundation”; so he closeted himself in a small room with a fireplace and spent the winter examining his beliefs using “the light of reason,” until he identified one that seemed absolutely secure and indubitable—the famous “cogito, ergo sum” (I think, therefore I am). Descartes, then, was a foundationalist and a member of its rationalist division, for he identified the foundation using his rational faculties (what [1] could not possibly be rationally doubted and [2] seemed indubitably true should be accepted as true).

The other branch of foundationalist epistemology—the empiricist camp—is represented well by a thinker from across the Channel, John Locke. After an evening of deep conversation with some friends that had quickly mired down, he attributed the failure to make progress in discussing important matters to the fact that our ideas are often not well founded and that the human ability to reach knowledge was not very well understood. Somewhat like Descartes, he started on an exercise of self-examination but reached a conclusion that differed from the one that the French philosopher had reached; in An Essay Concerning the Human Understanding (1690) he wrote:

Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper void of all characters, without any ideas. How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE. In that all our knowledge is founded; and from that it ultimately derives itself. (Locke 1959, 26; last emphasis added)

To the empiricist, the secure foundation of knowledge is experience, which of course comes via the human senses of sight, hearing, touch, and so on. (Descartes had rejected sensory experiences as the secure foundation for knowledge because such experiences could be mistaken or illusory.)

For complex historical and cultural reasons, the primary philosophical home of empiricism for several centuries was the English-speaking world, and the primary home of rationalism was the Continent of Europe (although, as we shall see, there are important exceptions to this generalization). Despite their clear difference of opinion about the nature of the “secure foundation” for knowledge, however, they were both obviously foundationalist epistemologies. Empiricists did not deny that human rationality played some role in knowledge construction (see Phillips 1998); Locke (to stay with him as a key historical figure) certainly emphasized that the mind can manipulate and combine ideas. But the point was that the basic ideas (the units, or “simple ideas,” as he called them) all came from experience. We cannot imagine the color blue, for example, if we have never experienced it (although we can be familiar with the word “blue” from reading or hearing it); but after we have a stock of simple ideas, we can combine and contrast them and build up complex ideas. Similarly, the rationalists do not deny that experience plays a role in knowledge construction, but it is subsidiary to the power of reason. As we shall see shortly, in the twentieth century there has been a recognition that although both reason and experience are important, neither is foundational in the sense of being the secure basis upon which knowledge is built. Much of contemporary epistemology is nonfoundationalist.

Empiricism and Positivism

We need to return to the development of empiricism as an approach to epistemology, for positivism is best regarded as a “fundamentalist” version of this. Essentially there were two somewhat different points embedded in the important passage from Locke quoted above, which were teased out over the years: (1) our ideas originate in experience (we can trace the genealogy, as it were, of any set of complex ideas back to simple ideas that originated in sense experience), and (2) our ideas or knowledge claims have to be justified or warranted in terms of experience (observational data or measurements, for example). The second of these points is particularly significant; to make a claim for which no evidence (in particular, no observational evidence) is available, is (in the eyes of an empiricist) to speculate. And no matter how enticing this speculation may be, we can only accept such a claim as knowledge after the relevant warranting observations or measurements have been made. Thus, the claim that there is life elsewhere in the universe is merely a claim and is not knowledge until warranting observations have been made, and likewise the claim that girls undergo a different pattern of moral development than boys.

Consider another example: Suppose that while “channel-surfing” one night you find yourself watching a war movie. Suddenly it occurs to you that there might be a relationship between the number of battle movies that are made in any given period and the suicide rate in society. The more you reflect on this, the more convinced you become—war movies foster a certain callousness or at least casualness toward violent death and injury, and it seems likely to you (to your “light of reason”) that this might render suicidal individuals more likely to commit this desperate act. Your hypothesis—“there is a positive correlation between the number of war movies and the suicide rate”—is not knowledge but is simply a hypothesis. No matter how much it appeals to the light of reason, it is an empirical/factual claim that can only be accepted as knowledge after the relevant warranting evidence has been examined (in this case, the data would be something like the numbers of war movies made per year over a longish period, say, from the late 1940s to the 1980s, with the suicide rates for those same years). It turns out that there is a relationship, but it is inverse—the more war movies that were made and released, in general the lower the suicide rate!

This example also illustrates several other points. In the first place, the example is phrased in terms of a correlation between war movies and suicide, but normally what interests us more is whether there is a causal relationship—whether the increased number of war movies caused the decrease in the suicide rate. Although the finding about the correlation mentioned above might be accurate and trustworthy, it certainly does not give one any grounds for thinking that there is a causal relationship—too many other factors were at work in society during those decades (access to television sharply increased and so the frequency of reruns of war movies on television needs to be considered; the popularity of other violent types of movies and television programs grew; and there were many sociocultural, religious, and economic changes in society that may well have affected both what kinds of movies were made and attitudes toward suicide). Second, the example illustrates that not only must empirical evidence be available but it must also be accepted by the appropriate research community as actually warranting the claim in question. (Actually, the point is stronger than the way it was just expressed: just as a pitch in baseball is not a strike until the umpire “calls” it, so tables of numbers or readings from instruments or records of observations or whatever are not evidence until the scientific community agrees to count them as such.) Most researchers would not accept the correlational data as evidence warranting belief in a causal relationship; some would regard the information about rates of production of war movies as quite irrelevant (as not being “data” at all, so far as suicide rates are concerned). Of course, these too can become matters of dispute within the relevant research community.

To return to the development of positivism, nineteenth-century philosopher Auguste Comte (who did not fit the generalization about empiricists made earlier, for he was French) seems to have accepted both of the aspects of empiricism foreshadowed in Locke’s work, and he argued strongly that the method of science (the “positive” method) was the method of arriving at knowledge. Scientific knowledge, he said, “gives up the search after the origin and hidden causes of the universe and a knowledge of the final causes of phenomena” (Comte 1970, 2) and instead focuses on observations and what can be learned by strict reasoning about observed phenomena. His work was the origin of positivism. (For further discussion, see Phillips 1992, chap. 7; Phillips 1994.)

But what if no observational evidence or data could conceivably be collected? (What if our claim was about the interior of black holes or about the human soul or about unconscious mental events that are not accessible to scientific data-gathering techniques?) A small group of philosophers, physical scientists, social scientists, and mathematicians working in and around Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s (another exception to our generalization about the Continent being inhospitable toward empiricism)—a group that became known as the logical positivists—took an extremely hard line on this matter, asserting that speculation about such things was nonscientific as well as nonsensical. They devised a criterion of meaning whereby it was literally meaningless to make statements about things that could not be verified in terms of possible sense experience—a criterion that renders all theological issues, for example, and Freud’s theories, as strictly meaningless. They labeled such meaningless discourse “metaphysics,” much to the chagrin of many other philosophers!

The work of the logical positivists became known in the English-speaking world through the writings of A. J. Ayer and others, and it was the source of B. F. Skinner’s view that psychology should restrict itself to the study of behavior, for only behavior is observable. He attacked the view that there were “inner” and “psychic” causes of behavior:

A common practice is to explain behavior in terms of an inner agent which lacks physical dimensions and is called “mental” or “psychic.” ... The inner man is regarded as driving the body very much as the man at the steering wheel drives a car. The inner man wills an action, the outer executes it. The inner loses his appetite, the outer stops eating.... It is not the layman alone who resorts to these practices, for many reputable psychologists use a similar dualistic system of explanation.... Direct observation of the mind comparable with the observation of the nervous system has not proved feasible. (Skinner 1953, 29)

All such “mental events,” and the “inner person” who harbors them, are strictly inferential, and Skinner labels them as “fictional” (Skinner 1953, 30); if “no dimensions are assigned” which “would make direct observation possible,” such things cannot “serve as an explanation” and can play no role “in a science of behavior” (Skinner 1953, 33). In a later book he took up again his critique of the “inner man” or “homunculus” or “the possessing demon” (which he also called the inner “autonomous man”):

His abolition has long been overdue. Autonomous man is a device used to explain what we cannot explain in any other way. He has been constructed from our ignorance, and as our understanding increases, the very stuff of which he is composed vanishes. Science does not dehumanize man, it de-homunculizes him.... Only by dispossessing him can we turn to the real causes of human behavior. Only then can we turn from the inferred to the observed, from the miraculous to the natural, from the inaccessible to the manipulable. (Skinner 1972, 200–201; emphasis added)

In these books Skinner stopped just short of claiming that references to such inferred inner entities or events are meaningless, but clearly he was close to holding this logical positivist view.

Another example of the influence of positivism in education-related research fields is the wide acceptance of the need for operational definitions of concepts that are being investigated (such things as “intelligence,” “creativity,” “ability,” or “empathy”). Operational definitions were first brought to prominence by physicist Percy Bridgman, a Nobel laureate, but they never caught on in the physical sciences to the extent that they became popular in psychological and educational research. (Perhaps physicists realized how much their field depended on entities that were “inferential” and not directly observable, such as quarks, black holes, and cosmological “super strings,” to use contemporary examples.) Bridgman’s idea was simple enough: A concept is meaningless unless the researcher can specify how it is to be measured or assessed (or how disputes about it are to be settled), and this specification has to be phrased in terms of the precise operations or procedures that are to be used to make the relevant measurements. Furthermore, if there are several different sets of operations that can be used, it can be doubted whether the same concept is involved. If a concept is defined in terms of a specific set of (measuring) operations, then if the operations are different it follows that the concepts are different (even if the same word is used in both cases to label the concepts). Bridgman made use of the simple example of length: We could define this in terms of the operations involved in using a measuring rod (laying the top end of the rod precisely alongside the top end of the object whose length is to be determined, then marking off the position of the bottom end of the measuring rod, then moving the top end of the rod down to this point and counting “one unit,” etc.); but we could also measure the length in terms of the number of wavelengths of a beam of monochromatic light, and so forth. It becomes an empirical matter to be determined by experiment (and perhaps by the application of theory), whether these various methods generate the same value and whether they could be said to both measure the same “length.”

The example of operational definitions illustrates that the legacy of logical positivism is a “mixed bag” instead of being entirely negative. On one hand, operationalism seems too narrow; for example, it certainly seems rash to say that it is meaningless to argue that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was more creative than Paul McCartney, simply because we might not be able to specify how to measure this (it might be a pointless or frustrating argument to have, but would it literally be “meaningless”?). On the other hand, it seems important for researchers, in most if not all cases, to be able to specify how they propose to measure or collect data bearing on some hypothesis that embodies a vague or poorly defined concept. Logical positivists were enamored of precision, which they saw as a key to the advancement of our knowledge, and if this was a failing when taken to dogmatic extremes, overall it was not too bad a failing to have! The following passage from the logical positivist Hans Reichenbach nicely embodies this spirit and also clearly displays the central tenets of this branch of empiricism:

Now consider a scientist trained to use his words in such a way that every sentence has a meaning. His statements are so phrased that he is always able to prove their truth. He does not mind if long chains of thought are involved in the proof; he is not afraid of abstract reasoning. But he demands that somehow the abstract thought be connected with what his eyes see and his ears hear and his fingers feel. (Reichenbach 1953, 4)

As we shall see in a later section of this chapter, Reichenbach and his colleagues underestimated the difficulty of “proving the truth” of scientific statements, but the emphasis on clarity and the grounding of our beliefs on observations still stand as ideals we ought not to dismiss too lightly.

Another commentator’s words can stand as a final summary:

The logical positivists contributed a great deal toward the understanding of the nature of philosophical questions, and in their approach to philosophy they set an example from which many have still to learn. They brought to philosophy an interest in cooperation.... They adopted high standards of rigor.... And they tried to formulate methods of inquiry that would lead to commonly accepted results. (Ashby 1964, 508)

Mistaken Accounts of Positivism

It is clear that positivists—those following in the tradition of Comte as well as those of logical positivist persuasion—all prize the methods of scientific inquiry as being the way of attaining knowledge. (This was clear enough in the passages quoted from Skinner, for example.) But a vital issue arises in consequence: Just what account is to be given of those methods? It is, as we shall see, a viable criticism of the positivists that they had much too narrow a view of the nature of science, and there are, of course, other problems with their general position. Despite the avenues that exist for valid criticism, it is common nevertheless to find that several mistaken charges are brought against them; labeling a person or position as “positivist” has become a favorite term of abuse in the educational research community, but it is a form of abuse that has itself become much abused!

In the first place, there is an obvious logical blunder: just because a point is made or a distinction is drawn by a positivist, it does not follow that this is a positivist point! Individuals of other persuasions might well be able to make the same point or draw the same distinction (for the same or for different reasons). Consider the following analogy. Biologist Stephen Jay Gould and certain fundamentalist Christian groups share some doubts about evolution as an explanatory theory, but it would be a mistake to consider them allies of one another! An example of this blunder involves the distinction that has been drawn between the so-called context of discovery and the context of justification, which was probably first recorded in the early work of logical positivist Hans Reichenbach. Others (including a vehement nonpositivist, Karl Popper) also make use of it, yet the distinction is sometimes regarded as being the hallmark of a positivist. In brief, the context of discovery is the context in which discoveries in science are first made, and the context of justification is the context in which these discoveries are justified or warranted as indeed being valid discoveries. Popper uses the distinction in large part to make the point that there is, in his view, no logic of discovery, that is, there is no set of algorithms or procedures by which one can reliably make scientific discoveries. But he believes that there is a logic of justification; namely, we establish that the discoveries are genuine by whether or not they survive severe tests aimed at refuting them. In the view of the present authors, the distinction is sometimes useful as a crude tool but in fact oversimplifies matters; discovery and justificatory processes take place together and cannot be meaningfully separated—a researcher is always evaluating data, evaluating his or her procedures, deciding what to keep and what to abandon, and so forth. In short, discovery and justification rarely occur sequentially.

Second, it is not the case that positivists must always advocate the use of the experimental method (as opposed to observational case studies, for example); and conversely, it is not the case that anyone who advocates conducting experiments thereby is a positivist. Experiments are unsurpassed for disentangling factors that might be causally involved in producing some effect and for establishing that some factor is indeed acting as a cause. Any researchers—of whatever philosophical or epistemological conviction, and not just positivists—might find themselves embroiled in a problem that would benefit from their obtaining insight into the causal factors at work in that context; but it is also the case that there are many research situations in which an experiment is not appropriate, for a positivist or anyone else. Thus, an experiment would not be appropriate if you wanted to determine what beliefs a teacher held about a particular classroom incident that you had observed; but an experiment might be relevant if you wanted to determine which factors were causally responsible for a two-minute skit on the television program Sesame Street producing the high degree of focused concentration that you had noticed in young viewers. Without an experiment, you could not say definitively what was responsible for their interest—the shortness of the skit, the content, the number and nature of the characters involved (puppets, or a puppet and a person, for instance), the voices, the type of humor involved (slapstick versus verbal), the presence of you as an observer, the characteristics of the particular children who were viewing the skit, or an interaction among several of these factors. But a series of studies in which these factors were systematically altered might settle the matter and yield information that was useful for individuals planning to produce other educational programs for that particular age-group. There is nothing particularly positivistic about the use of the experimental method here. (In fact it is a method we use in a rough-and-ready way in ordinary contexts all the time; for instance, when we pull out and then replace, one by one, the cables at the back of our stereo system to find out which one is causing a buzzing sound.) As Donald Campbell and Julian Stanley put it in their authoritative handbook on experimental designs, they were “committed to the experiment: as the only means for settling disputes regarding educational practice, as the only way of verifying educational improvements, and as the only way of establishing a cumulative tradition in which improvements can be introduced without the danger of a faddish discard of old wisdom in favor of inferior novelties” (Campbell and Stanley 1966, 2). It should be noted that in addition to being a psychologist, Campbell was an able philosopher who strongly opposed positivism.

A third, and somewhat related, misconception is that positivists can be recognized by their adherence to the use of quantitative data and statistical analyses. A positivist believes, as Skinner put it, that researchers must avoid the “inferred” and move instead to the “observed” (or observable) and in general must avoid using terms that in the long run cannot be defined by expressions that refer only to observables or to physical operations or manipulations. It should be evident that there is nothing here that identifies positivists with the use of quantitative data and statistics. And, as before, neither is the converse true—nonpositivists are free to use quantitative data and statistical analyses if their research problems call for these methods. In fact, many statistical models rely on probabilistic relations (relations of tendencies and likelihoods) and not on the mechanistic conception of reality that some early positivists held.

There is a fourth charge that at first might seem a little abstract but is nevertheless of some interest given recent debates in the research community. Positivists are often charged with being realists (another general term of abuse) in that they are said to believe that there is an “ultimate reality,” not only in the physical realm but also in the world of human affairs; it is the aim of science to describe and explain this one “reality” accurately and objectively. Yet a number of people these days believe that what is accepted as real depends on the theoretical or cultural framework in which the investigator is located; there are thus multiple “realities,” not one ultimate or absolute reality. We shall have more to say about this matter later; sensible people have different views on this, and indeed the coauthors of this volume have some disagreements over the various issues that arise here. (For an overview of the issues, see Phillips 1992, chap. 5.)

The problem is that this account of positivism is just about the opposite of the truth. If there is an ultimate reality, it is clear that (at least in the view of the positivists) we do not have direct observational contact with it, which is highlighted by the fact that philosophers often call the belief in an ultimate reality “metaphysical realism” (see, for example, Searle 1995). And, as should be clear again from the passages by Skinner that were quoted, positivists (especially those at the logical positivist end of the spectrum) are far from embracing metaphysical theories such as this. For most positivists, the only thing that matters is what we are in contact with, namely, our sense experience, and they accept that it is meaningless to make independent claims about the “reality” to which these experiences “refer” or “correspond.” (Technically, most positivists are more accurately described as adherents of phenomenalism or sensationalism rather than realism.)

PROBLEMS WITH FOUNDATIONALIST EPISTEMOLOGIES

A strong argument can be made that during the second half of the twentieth century the long reign of the foundationalist epistemologies (including positivism) came to an end (although the surviving adherents of empiricism and rationalism of course would not agree). It is important to realize, however, that experience and reason have not been shown to be irrelevant to the production of human knowledge; rather, the realization has grown that there are severe problems facing anyone who would still maintain that these are the solid or indubitable foundations of our knowledge. Before turning to an exposition of the new nonfoundationalist epistemology, and in particular the form of it that has traditionally been labeled as “postpositivism,” we need to give an account of the difficulties (findings and arguments) that led to this dethronement. In so doing we shall be “debunking” some traditional shibboleths about the nature of science and laying the foundation for the claim we shall make later that a more open and less doctrinaire account of the nature of science needs to be given.

There are six main issues that are extremely troublesome for foundationalists: the relativity of “the light of reason,” the theory-laden nature of perception, the underdetermination of theory by evidence, the “Duhem-Quine” thesis and the role of auxiliary assumptions in scientific reasoning, the problem of induction, and the growing recognition of the fact that scientific inquiry is a social activity. These will be discussed in turn.

The Relativity of the “Light of Reason”

This issue need not detain us for very long, because it is pretty obvious (!) that what is obvious to one person may not be obvious to another. What is indubitable and self-evident depends on one’s background and intellectual proclivities and is hardly a solid basis on which to build a whole edifice about knowledge. In the ancient world, Scipio evidently thought the following argument was self-evidently true, whereas we think it is obviously deficient: “Animals, which move, have limbs and muscles. The earth does not have limbs and muscles; therefore it does not move.” The ancient mathematician Euclid formalized geometry by setting it out as a series of deductions (proofs) starting from a few premises (assumptions or postulates) that he took to be self-evident or themselves needing no proof; but the history of the field in the past two centuries has been one in which questions have been raised about some of these premises—leading to the development of non-Euclidean geometries and also to new discussions of the nature of mathematical proof itself. Even Descartes’s famous premise “I think, therefore I am” has been shown to be more involved than he believed. Where, for example, does the notion of an “I” or self come from? (In fact, the important term “cogito” that he used, in which the verb form implies that there is an actor, is only true of the conjugations in certain languages. In other languages it is not even possible to say “I think.” Descartes tried to doubt everything, but he forgot to doubt his own language!) Hans Reichenbach makes a similar point about Descartes and then adds

It was the search for certainty which made this excellent mathematician drift into such muddled logic. It seems that the search for certainty can make a man blind to the postulates of logic, that the attempt to base knowledge on reason alone can make him abandon the principles of cogent reasoning. (Reichenbach 1953, 36)

None of these examples is meant to suggest that we should not use our rational faculties; rather, they show that caution and modesty are called for. Sometimes our reason is defective or the premises upon which our faculty of reason operates are not so strong and indubitable as we suppose.

Theory-Laden Perception

It is crucial for the empiricist (including positivist) branch of foundationalism that perception or observation be the solid, indubitable basis on which knowledge claims are erected and that it also serves as the neutral or disinterested court of appeal that adjudicates between rival claims. It has become clear, however, that observation is not “neutral” in the requisite sense.

Earlier this century a number of prominent philosophers, including Ludwig Wittgenstein, Karl Popper, and N. R. Hanson, argued that observation is theory-laden: What an observer sees, and also what he or she does not see, and the form that the observation takes, is influenced by the background knowledge of the observer—the theories, hypotheses, assumptions, or conceptual schemes that the observer harbors. A simple example or two should make this clear. One of the coauthors of this book had rarely seen a game of basketball played until after his migration to the United States from Australia in his mid-thirties. When one of his graduate students took him to his first professional game, all that he could see were tall men racing up and down the court bouncing and throwing the ball. Remarks from his companion like “Did you see that terrific move?” were met with a blank stare. To notice a few selected movements on court out of all the movements taking place there and to see them as constituting a “terrific move” requires some prior knowledge of basketball—enough, at least, to be able to know what constitutes a skilled “move” and what doesn’t, and enough to be able to disregard the irrelevant actions taking place on the court at that moment. To restore the ego of our coauthor, however, it should be noted that he has been a conjuror since childhood, and at a professional magic performance or when watching magicians on television he can see “moves” that other members of the audience do not notice! Similarly, someone who has had classroom experience can often see things happening that another observer without that background cannot or does not. “There is,” as Hanson put it, “more to seeing than meets the eyeball” (Hanson 1958, 7).

It is worth clarifying that the coauthor was not suffering from poor eyesight. His brain was probably registering (if only briefly) the complex plays happening on the basketball court (although we must be careful here, for human perception is not quite like a mental video recording). But he did not notice certain things, and so he described what was happening differently from his student, who knew the significance of certain things and so saw and described the events differently (a description that also drew heavily on basketball “jargon,” or terminology). But our hero knows, from long experience, that anyone watching a magic show has to be alert to the magician’s stratagem of “misdirection”—a technique whereby the magician, either through words or actions or the use of interesting props such as bright silk scarves or attractive assistants, leads members of the audience to expect a certain thing to happen; they focus their attention on what they expect, and they don’t notice where the really significant action is taking place (the magician’s left hand retrieving a pigeon from a holder under the bottom of his jacket, for example).

Another case might be helpful. One of us was conducting a class in which the teaching assistant was a dedicated Freudian who had worked in a school for schizophrenic children; a student taking the class was an advanced doctoral student with a strong background in behaviorist psychology. The topic of autism came up, and the instructor decided to show a short film that featured a young autistic woman who had been treated and apparently “cured.” The behaviorist and the Freudian had held opposing theories about the nature of autism, and hence they also strongly disagreed about the efficacy of the treatment described in the film. The class viewed the film with the sound track turned down as the two of them stood on either side of the screen and gave rival commentaries. There was an amazing disparity—they noticed quite different things (often ignoring events and features that the other pointed to as being significant), and of course they used quite different terminology to speak about what they were seeing. What they were seeing, how they described it, and also what they didn’t see or pay attention to, all seemed to be directly influenced by the different theories and assumptions they were bringing with them. There was no “theory neutral” observational “court of appeal” that could be appealed to in order to settle beyond all possibility of argument the differences between them.

The Underdetermination of Theory by Evidence

This difficulty to some extent overlaps the one described above; it is another “nail in the coffin” of all forms of empiricist foundationalism. Put starkly, we cannot claim that observational or other evidence unequivocally supports a particular theory or fully warrants the claim that it is true because there are many other (indeed, a potentially infinite number of other) theories that also are compatible with this same body of evidence (and can thereby claim to be warranted by it). More pithily, theory is underdetermined by evidence—which is a severe blow to the view that our knowledge is “founded” on sense experience.

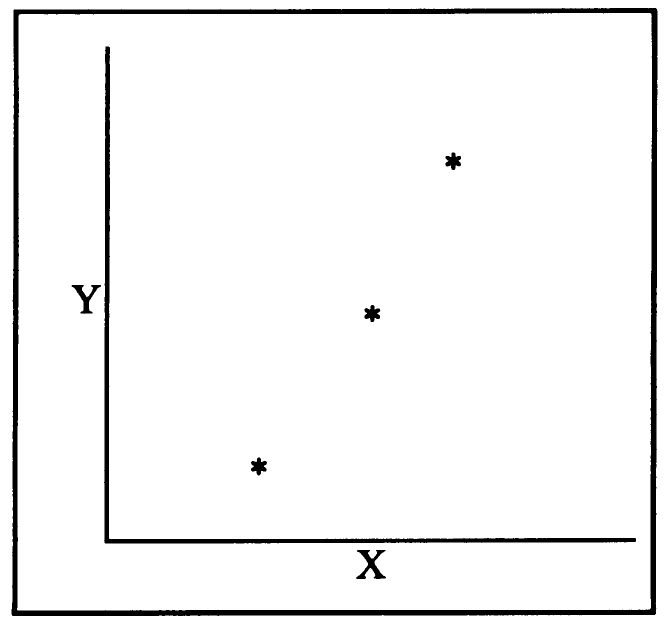

This can be demonstrated most simply by means of a couple of diagrams. Suppose that we have performed a study and have collected some data points that can be graphed as follows (let us use X and Y as the axes representing the two factors in which we are interested). (See Figure 1.2.)

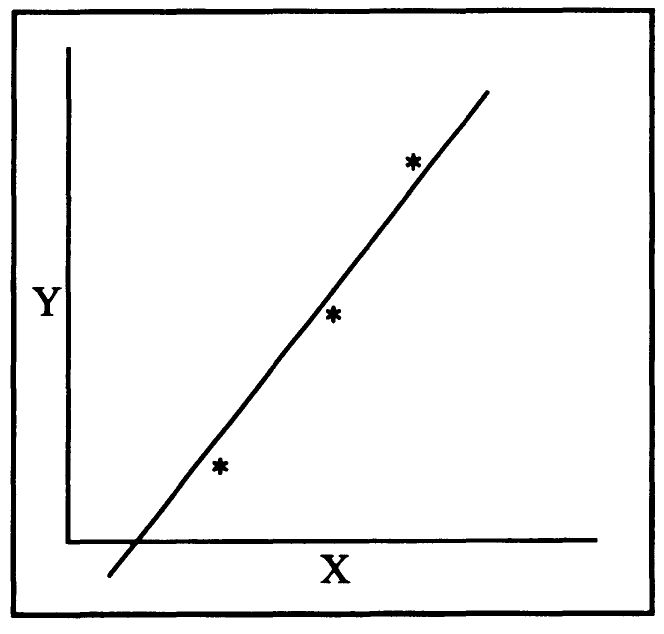

It might be supposed that these points support the “theory” that the relationship between X and Y is a linear one that can be depicted by a straight line. (See Figure 1.3.)

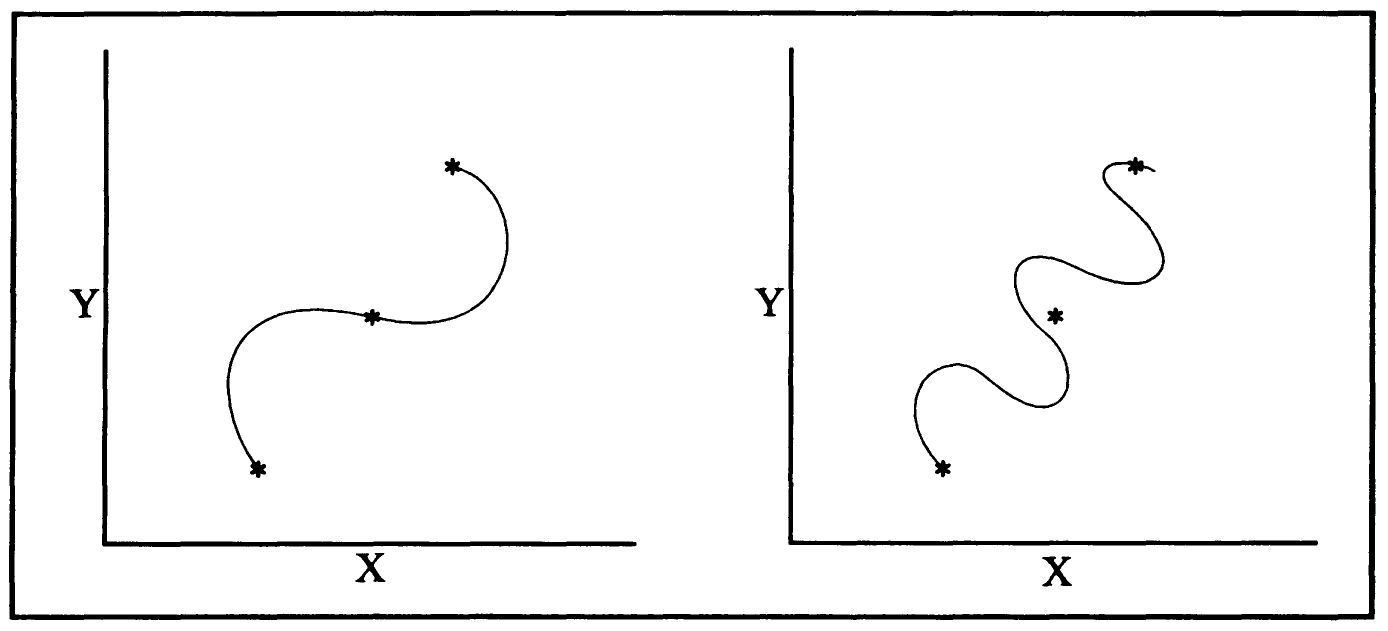

But, in fact, there are infinitely many curves that can be drawn to fit these three data points, just two of which are depicted in Figure 1.4.

The fact of the matter is that the three points underdetermine the shape of the curve/line (i.e., in effect the nature of the theory) that we can hypothesize “fits” them. Nor is the situation helped if a fourth or even a fifth point (or more) is added. Even if these new points happen to fit the straight line, the matter is not settled, for although one or maybe both the curves depicted above will be shown to be incorrect, an infinite group of other more intricate curves will remain compatible with the newly extended set of data points. We might hold beliefs or accept criteria that persuade us that the line is the correct hypothesis, for example; we might have the assumption that nature is simple (although we would also need to make the assumption that lines are geometrically simpler than curves). But then, obviously, it is not the observational data alone that are determining what hypothesis we will accept. (It is worth noting that an issue touched upon earlier is relevant to this example: All the points that are being graphed have to be accepted by the researchers concerned as being genuine data; of course, the new data points might be rejected as “outliers” or simply as erroneous or “artifacts.” When new information does not fit your theory, which do you doubt first: the long-standing theory or the new information?)

Figure 1.2. Data about X and Y

Figure 1.3. One Possible Relationship

The point that there is a gap separating the observation of a phenomenon from the forming of an explanation or theory or hypothesis about it can be made in another way—the gap cannot be bridged without help from outside the observed phenomenon itself! A phenomenon does not have associated with it anything that determines that we must conceptualize or describe it in a particular way—many possible alternative descriptions always exist. In the phraseology favored by philosophers of social science, a phenomenon exists under different descriptions, and it might be easier to explain when placed under one description rather than another. Consider an example that could easily arise during a classroom observation session: A teacher is confronting a student in the class and is pushing her with a relentless series of rather curt questions about the subject matter of last night’s homework. The first thing to note is that even this description of the phenomenon is not theory neutral—why did we describe it in terms of “confronting” and “pushing,” or “curt” and “relentless”? We could also describe what happened in terms of the language of “interaction” or “dialogue”—there was an extended interaction or dialogue in which the teacher asked a series of difficult questions and so on. Perhaps we could describe what happened in terms of the teacher venting her anger or hostility on the student, or we could describe it as the teacher acting out an oppressive power relation, or we could describe it in terms of the teacher trying to motivate the unwilling student by asking her a series of challenging questions about the homework. One of the problems here is that we, the classroom observers, are probably approaching the situation with hypotheses or background theories already in mind that color our observations (for, as we have seen, all observation is theory-laden); perhaps we were told by the principal of the school that the teacher is an unpleasant and unsympathetic person, and the description given above was written from that perspective. The point is that whatever occurred in the classroom took place without labels attached. We, the observers, provide the labels, and we have a wide range from which to choose. And the way we describe the phenomenon is related to the way we will explain it—a teacher being curt and even victimizing a student is explained differently from a teacher challenging a student to “be all that she can be”! (Philosopher Bertrand Russell somewhere used this example, which makes the same general point: “I am firm, you are stubborn, and he is a pig-headed fool.” These are three labels that describe the identical character trait of “sticking to your opinions,” but they are labels that embody quite different theories and evaluations of the trait. The phenomenon itself is “neutral” with respect to these evaluative descriptions. Another example widely used by philosophers is the observation that a person’s arm rises; is this to be described as a twitch, as a salute, or as the asking of a question? The choice of the description will be made by considering more than just the sight of the arm moving; it will involve many other assumptions or judgments about context, intent, and cultural conventions—just the sorts of things Skinner would advise us to ignore!)

Figure 1.4. Other Possible Relationships

The Duhem-Quine Thesis and Auxiliary Assumptions

The so-called Duhem-Quine thesis, named in honor of the two philosophers who formulated it, also presents a problem for empiricists who believe that evidence (observational data or measurements) serves unproblematically as a solid and indubitable basis for our knowledge. The thesis can best be explained in terms of an analogy. Think of all your knowledge, of all the theories you accept, as being interrelated and as forming one large network; this whole network is present whenever you make observations or collect data. Now suppose that you are carrying out a test of some hypothesis and you find a recalcitrant piece of data that apparently refutes this. Do you have to abandon or at least change the now challenged hypothesis? Not at all; certainly you have to make some accommodating change somewhere, but perhaps the problem is not with your hypothesis but with some other part of your network of beliefs. To test your hypothesis you may have accepted some other data, then made calculations on this, then used instrumentation of some sort to set up the test of the prediction you have made. The error could well have entered somewhere during this complex process. (There is a danger here—an unscrupulous researcher could use this line of argument to protect his or her favorite hypotheses or theories from refutation during tests by always laying the blame on something else.) The point of the Duhem-Quine thesis is that evidence relates to all of the network of beliefs, not just to one isolated part; all of our beliefs are “up for grabs” during the test of any one of them—we can save one assumption or belief if we are willing to jettison another one.

Whenever we carry out a study, test some hypothesis, or explore an issue, we make use of various parts of our background knowledge (the extended network) that we are taking to be unproblematic at least for the purposes of the particular inquiry that we are engaged upon at present. Thus we may make use of measuring devices or tests or interview questions, on the assumption that they are sound; we might use various types of statistical analyses, making the same assumption about these techniques. These (temporarily unproblematic) items of background knowledge or of established techniques have been called “auxiliaries” or “auxiliary assumptions.” Thus, when we test hypotheses and try to extend the domain of our present knowledge, the phenomena do not “speak for themselves”; in fact we are trying to determine what to make of them, using these auxiliaries as tools in the process. So much for the key “foundational” thesis of empiricism!

The use of auxiliaries is particularly relevant for understanding the logic of testing our hypotheses, which is an important way in which we provide warrants for them. Hypotheses that survive strong tests might not be true, but certainly surviving a series of tests is much more to their credit than failing. The traditional account of testing (sometimes called “the hypothetico-deductive method”) is as follows: Suppose that “H” is the hypothesis that we are testing and “P” is the prediction we deduce from this hypothesis. If H is true, we predict P will be found to be true, and we collect data to test this prediction. If P is not found to be borne out, then H must be false. (Extra credit: Logicians call this form of argument “modus tollens”!) We can represent the logical syllogism in this way:

Or in terms of an example:

If this student is at Kohlberg’s stage 5, then she will answer X when interviewed.

She did not answer X.

Therefore she is not at Kohlberg’s stage 5.

However, this account omits the presence of the auxiliaries that were used in carrying out the test; a more accurate description of the situation is the following (using “A” to represent the auxiliary premises or assumptions):

This is a valid piece of reasoning, but unfortunately it is not as helpful as we might have wished. If a test is negative, we cannot conclude that the hypothesis is incorrect, for the error might lie somewhere in the auxiliaries; we can only conclude that there is an error somewhere in the conjunction “H and A.” In terms of the example,

If this student is at Kohlberg’s stage 5, and if the interview questions are an accurate way to measure Kohlberg’s stages, and if the student is answering honestly, and so forth, then she will answer X when interviewed.

She did not answer X.

Therefore, either she is not at Kohlberg’s stage 5, or the interview questions were not an accurate way to determine what stage she was at, or she was not answering honestly, etc.

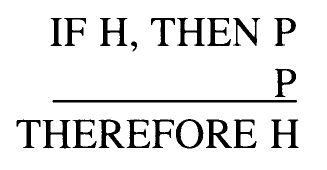

For the record, it should be noted that positive tests never establish that H is true, for the form of argument involved is a fallacy. (More extra credit: Logicians call this “affirming the consequent”!):

Or in terms of the example:

If this student is at Kohlberg’s stage 5, and if (the auxiliaries), then she will answer X when she is interviewed.

She answered X.

Therefore she is at Kohlberg’s stage 5.

It is easy to see that this is invalid; she might have gotten the answer by guessing or by accident, or perhaps people other than those at stage 5 also can give this answer.

Thus no number of positive instances necessarily proves a particular theory or hypothesis because any finite set of data can be accounted for in more than one way; conversely, no number of disconfirming instances necessarily disproves a particular theory or hypothesis because we can modify or reject some other part of our belief system to explain away the apparently disconfirming instances. These points seem to support the relativistic view that there is no way a theory or hypothesis can be either proven or disproven and thus one theory is as good as another! We will argue later that the failure of the hard positivistic account of what constitutes proof does not, however, need to lead us to completely denigrate hypothesis formation and testing; postpositivism simply approaches such matters with a more modest and less foundationalist set of aspirations.

The Problem of Induction

This is the longest-standing issue for empiricists, with a lively history of discussion going back about two and a half centuries to the work of the Scottish philosopher David Hume. Put simply, the problem is this: How do we know that phenomena that we have not experienced will resemble those that we have experienced in the past? Our knowledge would be limited in usefulness if it only applied to cases in which we already have evidence that our claims are true. All of us, empiricists or not, often wish to apply our knowledge to new or prospective cases; we wish to make plans, to order our lives, to make rational predictions, to intervene in social or educational affairs to effect improvements. We wish to use our understanding of gravity, for instance, which is based on our experience observing phenomena on the earth and in the solar system and nearby universe, to understand events that took place in the early life of the universe or are happening at present inside black holes (both these classes of phenomena, of course, being unobservable to us). We expect that airplanes, which have flown in the past, will continue to fly in virtue of the fact that the forces of nature that enabled flight to take place up until now will continue to operate in the same ways. We wish to take treatments of learning disorders that were proven to be efficacious in past studies and use them in cases tomorrow. Or, to use Hume’s more homely example, “The bread which I formerly ate nourished me.... But does it follow that other bread must also nourish me at another time ... ?” (Hume 1955, 48).

What entitles us to be sanguine about our prospects of applying our understandings (our currently warranted understandings) to new cases? What observations have we made that enable us to be certain about as yet unobserved cases? Hume’s skeptical conclusion about these matters has rung out through the years; referring to the question of whether it follows that in future bread will continue to be nourishing to humans, he said tersely, “The consequence seems nowise necessary” (p. 48). And, of course, as an empiricist Hume seems to have been justified in holding this opinion for, if our knowledge is based solely on experience, we cannot have knowledge about things that we have not experienced! Hume concluded that (to use modern terminology) we are more or less conditioned; we get into the habit of expecting that a past regularity or uniformity will hold in the future, simply because it held true in all relevant cases in the past. We have eaten bread so often that we simply expect (as a matter of psychological accustomization) that it will be edible and nutritious in the future. But this expectation is not logically justified.

The logical issue is as follows: Apparently we make inductions in which we extend our knowledge beyond the evidence available, but induction is not a logically compelling form of reasoning, as the following makes clear:

No matter how many cases of “A” we observe to have characteristic X, no matter how large the “N” happens to be, it does not follow logically that all cases of A will have this characteristic; we are making an inductive leap beyond the evidence we have available, and there is no certainty about our conclusion. This is illustrated in logic texts by the classic example that warms the heart of our coauthor from Australia: All the very many swans observed in Europe up until the settlement of Australia were found to be white, so the inductive conclusion had been drawn that all swans were white, and this “obviously true” inductive generalization was often used in textbooks; unfortunately for this induction, when Europeans arrived in western Australia, they discovered black swans on what they came to call, appropriately enough, the Swan River! (We should note here, echoing a previous discussion, that one possible response could have been—and indeed was—that these creatures were not swans; in other words, the previous generalization could have been protected!)

Insofar as inductive reasoning has been regarded as fairly central in science, the “problem of induction” has seemed something of a disgrace. Science is a prime example of human knowledge, yet it centrally involves a form of reasoning that is not logically compelling! So philosophers of science and logicians have been much exercised to find a solution. Some, like Karl Popper, have denied that inductive reasoning is important in science; indeed, Popper denied that it exists at all. (He believed that we misdescribe the pattern of reasoning we use and mistakenly suppose it to be inductive, when really we should regard our collecting evidence about A1, A2, and so on as a series of independent tests of the hypothesis that “all A have X”; he rejected the view that our observations concerning A1, A2, and so on were the foundational observations from which we induced the conclusion that “all A have X.”) Others accept the fact that induction is not deductively valid, and so its conclusions are not certain, but argue that inductive reasoning at least makes the conclusions we reach probable. The fact that N cases have been found in which an A has characteristic X (and that no cases observed so far lack X) does not establish that all cases of A have X; but this fact makes the conclusion that “all A have X” to some degree probable. However, there are two problems here: How can this probability be calculated? And does probability provide a strong enough foundation on which empiricists can erect the whole edifice of our scientific knowledge?

Some philosophers and scientists favor a slightly different “Bayesian” approach, in which new evidence that an A has characteristic X reduces the prior uncertainty that we had about all cases of A having X (an approach that uses a theorem of probability theory derived in the eighteenth century by Thomas Bayes). This was the path favored by Hans Reichenbach, who clearly recognized that “Hume’s problem” required a recasting of empiricism, for he wrote that the “classical period of empiricism ... ends with the breakdown of empiricism; for that is what Hume’s analysis of induction amounts to” (Reichenbach 1953, 89). His Bayesian probabilistic approach becomes clear a little later:

A set of observational facts will always fit more than one theory; in other words, there are several theories from which these facts can be derived. The inductive inference is used to confer upon each of these theories a degree of probability, and the most probable theory is then accepted.... The detective tries to determine the most probable explanation. His considerations follow established rules of probability; using all factual clues and all his knowledge of human psychology, he attempts to arrive at conclusions, which in turn are tested by new observations specifically planned for this purpose. Each test, based on new material, increases or decreases the probability of the explanation; but never can the explanation constructed be regarded as absolutely certain. (Reichenbach 1953, 232)

Here Reichenbach is moving from logical positivism to present-day nonfoundationalist postpositivism!

Despite the attractiveness of the position of Reichenbach and others on this matter, it is safe to say that there is no unanimity about how to resolve “Hume’s problem”—even postpositivists disagree amongst themselves over this issue.

The Social Nature of Scientific Research

The classic empiricists (and for that matter rationalists as well) did not make much of the obvious fact that researchers belong to a community; Locke’s account, for example, was phrased in very individualistic terms—the inquirer individually constructs complex ideas from his or her stock of simple ideas, which have their origin and justification in that particular individual’s experience. The empiricist can, of course, acknowledge that an individual scientist interacts with colleagues while on the path to formulating a new item of knowledge, but the decision about the content of the knowledge claim is always, for the empiricist, driven solely by the sense experiences that serve as the foundation for that claim. Since the publication of Thomas S. Kuhn’s important book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Kuhn 1962), however, there has been a growing acknowledgment of the fact that the community to which the scientist belongs (a community that is united around a framework, or paradigm) plays a more central role in determining what evidence is acceptable, what criteria and methods are to be used, what form a theory should take, and so forth. These things are not simply determined by “neutral” sense experience. Kuhn wrote:

The very existence of science depends upon vesting the power to choose between paradigms in the members of a special kind of community.... [The members of this group] may not, however, be drawn at random from society as a whole, but is rather the well-defined community of the scientist’s professional compeers.... What better criterion than the decision of the scientific group could there be? (Kuhn 1962, 166–169)

And it is not only choice between paradigms; choices made within paradigms also are a matter for communal decision. Kuhn states that the solutions to problems within the framework that are put forward by the individual scientist cannot “be merely personal but must instead be accepted as solutions by many” (Kuhn 1962, 167).

The point that subsequent scholars have developed is that decisions made within groups—even professional groups of scientists—are influenced by much more than the “objective facts.” In a broad sense, “political” factors can be seen to play a role, for in a group some people will of necessity have more power or influence than others, some will have their voices repressed, some individuals will have much more at stake than others (their reputations or economic gains, for instance), and some will be powerfully motivated by ideologies or religious convictions. As the editors of the volume Feminist Epistemologies put it, “The work presented here supports the hypothesis that politics intersect traditional epistemology.... [These essays] raise a question about the adequacy of any account of knowledge that ignores the politics involved in knowledge” (Alcoff and Potter 1993, 13). This is a long way from the vision of how scientific knowledge is built up that was held by Locke, Comte, and Bridgman. It remains to be seen to what degree postpositivists can accommodate this social perspective.

CONCLUSION

The new approach of postpositivism was born in an intellectual climate in which these six problems confronting foundational epistemologies had become widely recognized. This new position is an “orientation,” not a unified “school of thought,” for there are many issues on which postpositivists disagree. But they are united in believing that human knowledge is not based on unchallengeable, rock-solid foundations—it is conjectural. We have grounds, or warrants, for asserting the beliefs, or conjectures, that we hold as scientists, often very good grounds, but these grounds are not indubitable. Our warrants for accepting these things can be withdrawn in the light of further investigation. Philosopher of science Karl Popper, a key figure in the development of nonfoundationalist postpositivism, put it well when he wrote, “But what, then, are the sources of our knowledge? The answer, I think, is this: there are all kinds of sources of our knowledge, but none has authority.“ Thus the empiricist’s questions, ‘How do you know? What is the source of your assertion?’, are wrongly put. They are not formulated in an inexact or slovenly manner, but they are entirely misconceived: they are questions that beg for an authoritarian answer” (Popper 1965, 24–25; emphasis in original).

REFERENCES

Alcoff, L., and E. Potter. 1993. Feminist Epistemologies. New York: Routledge.

Ashby, R. W. 1964. “Logical Positivism.” In A Critical History of Western Philosophy. Edited by D. J. O’Connor. New York: Free Press.

Campbell, D., and J. Stanley. 1966. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Comte, A. [1830] 1970. Introduction to Positive Philosophy. Translated by Frederick Ferre. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Curtis, C., and F. Greenslet, eds. 1962. The Practical Cogitator. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Descartes, R. [1641] 1953. Meditations on the First Philosophy. In A Discourse on Method. Edited and translated by Joh Veitch. London: Dent/Everyman Library.

Dewey, J. [1938] 1966. Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Hanson, N. R. 1958. Patterns of Discovery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hume, D. [1748] 1955. An Inquiry concerning Human Understanding. New York: Macmillan.

Kuhn, T. S. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Locke, J. [1690] 1959. An Essay concerning Human Understanding. London: Dent/ Everyman Library.

Phillips, D. C. 1992. The Social Scientist’s Bestiary. Oxford: Pergamon.

Phillips, D. C. 1994. “Positivism, Antipositivism, and Empiricism.” In International Encyclopedia of Education. Edited by T. Husen and N. Postlethwaite. 2d. ed. Oxford: Pergamon.

Phillips, D. C. 1998. “How, Why, What, When, and Where: Perspectives on Constructivism in Psychology and Education.” Issues in Education 3, no. 2: 151–194.

Popper, K. 1965. Conjectures and Refutations. 2d ed. New York: Basic.

Reichenbach, H. 1953. The Rise of Scientific Philosophy. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Searle, J. 1995. The Construction of Social Reality. New York: Free Press.

Skinner, B. F. 1953. Science and Human Behavior. New York: Free Press.

Skinner, B. F. 1972. Beyond Freedom and Dignity. London: Jonathan Cape.

Winokur, J. 1987. The Portable Curmudgeon. New York: New American Library.