4

Can, and Should, Educational Inquiry Be Scientific?

Throughout much of its history the basic question in the philosophy of social science has been: is social science scientific, or can it be? Social scientists have historically sought to claim the mantle of science and have modeled their studies on the natural sciences.... However, although this approach yielded important insights into the study of human beings, it no longer grips philosophers or practitioners of social science. Some new approach more in touch with current intellectual and cultural concerns is required.

Brian Fay

Near the end of chapter 3 we raised the educational form of Fay’s “basic question,” namely, how far can we go in studying human affairs (including educational phenomena) using the methods of natural science? In the following discussion we adopt a position nearly diametrically opposed to that of Fay quoted above (Fay 1996, 1). Postpositivists (and many practitioners of social science and educational research) hold that much educational research can be, and ought to be, “scientific.” But we add the vital proviso that this position is reasonable only if the positivistic account of the nature of science prevalent in earlier times is replaced by a more up-to-date postpositivist account. Contra Fay, this new account of the nature of science is in touch with what is valid in “current intellectual” concerns. (For a detailed critique of Fay’s views, see Wight 1998.)

Arguments for the disjunction of natural science and social science have often rested on an unrealistic account of the nature of the natural sciences. If they are viewed according to the positivist model as based on foundationalist assumptions about evidence, proof, and truth, then social science does seem to be quite different. But when science is viewed according to the postpositivist model—in which observations are theory-laden, facts underdetermine conclusions, values affect choice of problems, and communities of researchers must examine methods and conclusions for bias—then the perceived gap between social and natural sciences begins to disappear.

Proponents of some currently popular views will not find the line of argument developed here very palatable; following Koertge and others (1998), a postpositivist is likely to regard these “contemporary cultural concerns” (especially many forms of postmodernism and social constructivism) as being “a house built on sand.”

Why do some philosophers and others doubt that social and educational inquiry is (or should be or can be) scientific? Why is the naturalistic ideal for social science and related fields such as educational research (i.e., the ideal that research here can be, in vital respects, similar to research in the natural sciences) rejected? In the end, we shall argue that this rejection is mistaken, but there is undoubtedly much to learn from the points raised by the opponents of naturalistic social research.

One reason for the opposition to this ideal has already been discussed. Until a couple of decades ago the dominant account of social science was positivistic, and this rightfully was seen to be a most unpromising approach to building an effective and comprehensive account of human social phenomena. For that matter, it was also a most unpromising approach to understand even the physical and biological worlds! This is not to deny that behaviorism (in its time the most widely influential form of positivism in the social sciences and education) made a useful contribution, and it was certainly pursued with vigor. (Skinner’s novel, Walden Two, was a brave attempt to show what an ideal society constructed on behaviorist principles could be like; see Skinner 1948.) But positivism, being an unsatisfactory philosophy of science, led to an unsatisfactory account of the roots of human action:

We can follow the path taken by physics and biology by turning directly to the relation between behavior and the environment and neglecting supposed mediating states of mind. Physics did not advance by looking at the jubilance of a falling body, or biology by looking at the nature of vital spirits, and we do not need to discover what personalities, states of mind, feelings, traits of character, plans, purposes, intentions, or other perquisites of autonomous man really are in order to get on with a scientific analysis of behavior. (Skinner 1972, 15)

Here, in one fell swoop, Skinner has been able to get rid of much that is of interest and relevance in human life; we severely limit the scope of educational research if we abandon interest in the states of mind, feelings, plans, purposes, and intentions of students and teachers, of parents and children, of educational policy makers and curriculum developers. No wonder Fay and many others have been turned off to a “scientific approach” if this is what is understood by the phrase! But that is the wrong reaction. What we need is an account of science that does not limit the understanding of human nature so severely, and postpositivism turns out to fill this bill admirably.

Fay incorrectly states that the choice is between two lternatives—an inadequate positivistic science or an adequate nonnaturalistic approach (which he calls “perspectivism”). But in fact there are three alternatives at least: the two above, plus a third that Fay does not consider—a postpositivistic science that gives a more adequate account of the nature of the physical sciences and that applies, inter alia, to the social sciences and educational research. Karl Popper made a point similar to ours by commenting that when the critics of his position “denounce a view like mine as ‘positivistic’ or ‘scientistic,’ then I may perhaps answer that they themselves seem to accept, implicitly and uncritically, that positivism or scientism is the only philosophy appropriate to the natural sciences” (Popper 1972, 185). Like Popper, we follow the third path and adopt postpositivism as a philosophy of science adequate for understanding competent research in the natural sciences as well as in the social sciences and educational research.

Skinner’s error, illustrated in the various passages from his works that we have quoted in this book, was that he started with a philosophy of science—the positivism that was prevalent when he was a student in graduate school—that he used to screen or select phenomena suitable for study. Unfortunately, the philosophy he used led him to regard unobservable entities as being unreal (or sometimes as being “prescientific” speculations; see the lengthier discussion of this in Phillips 1996)—a consequence that is as damaging to physical science as it is to psychological and educational research, for it means that subatomic particles, quantum phenomena, and black holes are as lacking in scientific merit as are the intentions, states of mind, feelings, and purposes of individuals. There is a better alternative to Skinner’s procedure. The phenomena that are of interest and relevance can be selected, and then great efforts can be made to develop methods by which they can be studied rigorously and “competently.” Our problems and interests can drive the development of our scientific methods, rather than vice versa.

The opponents of the naturalistic ideal in social science and educational research are apt to point out that the phenomena that are the objects of study in these fields are grossly misconceived when studied in terms of the “Cartesian-Newtonian paradigm” taken from the natural sciences. From what we have said above, it can be seen that we go some distance with them on this matter. But we do not think the answer is to abandon the naturalistic approach completely; rather, it is to grasp a more adequate account of the nature of science. To see what is at issue here, we must now turn to look at the kinds of human social phenomena that are the focus of attention in this literature and why some argue that they require a nonnaturalistic mode of explanation. (The phenomena discussed below do not exhaust the scope of social science and educational research, as some writers infer; we shall return to this issue near the end of the chapter.)

EXPLAINING HUMAN ACTION AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

It is common for philosophers of social science to distinguish between human behavior and human action (different individuals use different terms to label this distinction, but the terms we have chosen to use are perhaps the most common). Physical objects also exhibit behavior, but only humans can act (this latter statement might be too strong, for it could be argued that some animals can perform a limited range of actions).

A behavior is a physically (including chemically and biologically) induced and described movement or change or event: a rock can slide down a mountain in an avalanche, a comet might collide with a planet, a piece of metal will dissolve in an acid, a piece of food can be digested in an animal’s stomach, a soft drink can placed in a freezer will eventually burst, a newborn baby will begin to suck. Insofar as humans are physical objects (they are made up of molecules, they occupy space, they are subject to the physical, chemical, and biological forces and processes found in nature), they also exhibit behavior. Thus, Nick falling over as a result of slipping on a banana skin is behavior, as is Denis developing a fever. Nick’s arm moving up into the air is a behavior (it is a physical movement), as is Denis emitting a loud noise through his mouth. (But as we shall see, both these behaviors might also be actions.)

Philosophers give different accounts of the nature of explanation. We favor the view that to explain a behavior is to show that it was produced by some causal structure or process that exists in nature; in general this is to show that the phenomenon falls under the domain of one or more natural laws. Carl Hempel developed an earlier view that was dominant for many years, which (for expository purposes) we shall adhere to in the following (in the limit it comes close to the view we favor). The event to be explained is shown to be of the kind that the laws are applicable to, and the laws together with the specifics of the situation (the so-called initial conditions) are sufficient to account precisely for that event happening the way it did. Thus, the laws of motion, conservation of energy, and so forth, together with the details of the mass of the comet and its velocity, are sufficient to explain the behavior (the complex event) that occurs when the comet plunges into the earth. Similarly, information about Nick’s muscle and bone structure, the laws of gravity, and so forth, explain what happens when he slips and falls or raises an arm. If some unexpected physical event occurs—a heavy picture falls from the wall, to use an example that recently occurred in the presence of one of the authors—then one looks to the laws that were likely to have been operating for an explanation of the picture’s behavior; in this case, the weight of the picture was greater than the force of friction holding the picture hook into the soft plaster wall.

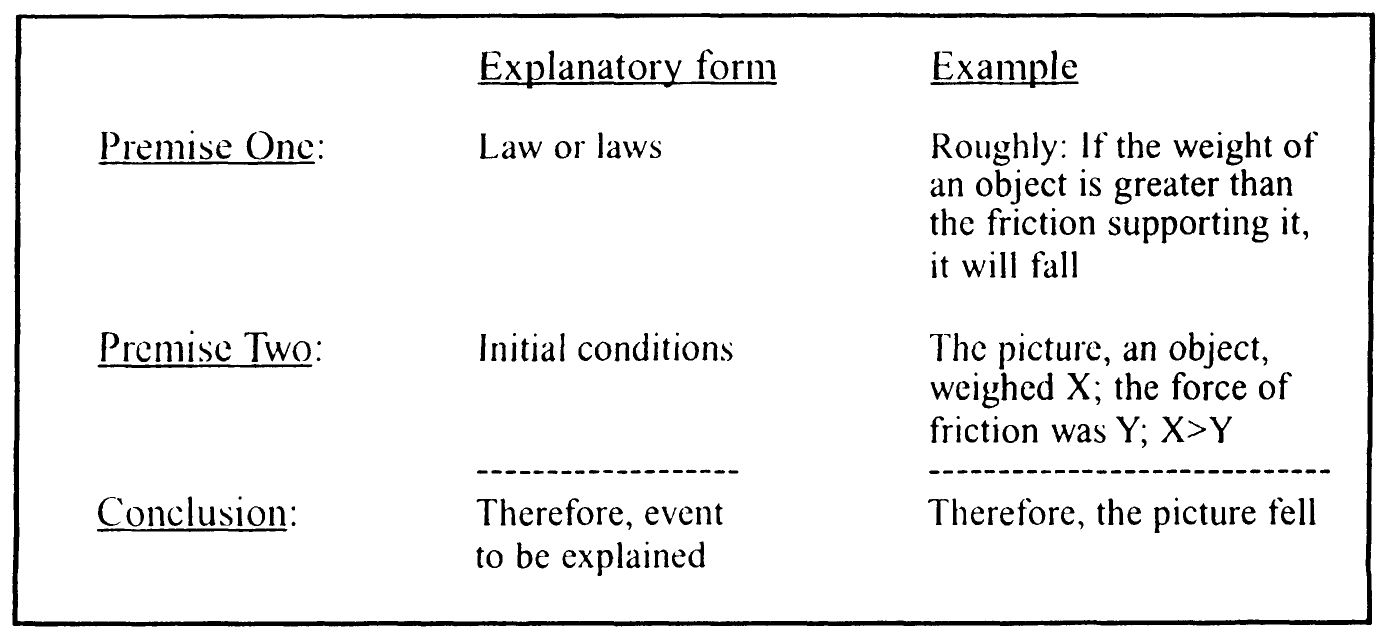

Hempel called this a “deductive nomological explanation,” for it can be cast into the form of a deduction with a law (hence the “nomological”) as one premise, the initial conditions as other premises, and the event or behavior that is being explained as the conclusion of the deduction. (This aspect of Hempel’s theory has spawned a great deal of philosophical discussion but can serve here as the prototype of the explanation of a behavior without undue damage occurring. For a readable exposition, see Hempel 1966.) Schematically, “Why did the picture fall?” (See Figure 4.1.)

This example raises, in a very direct way, the key issue for social scientists and educational researchers: Does this pattern of explanation (or something roughly like it if Hempel’s account is regarded as oversimple) work with respect to human and social phenomena? The crux of the matter (for our purposes) is whether or not there are causal structures that exist (or lawlike generalizations that apply) in these domains in the same way that they evidently do in physical nature. And this brings us to the other half of the behavior/action distinction.

Actions are things like voting, asking permission to leave the room, asking a question, shouting abuse, doing a pratfall to amuse one’s grandchildren, putting down an opponent, impeaching a president, running to keep an appointment, cashing a bank check, solving an algebra problem, designing a proof for the untenability of postpositivism, going to class, cleaning the chalkboard, stopping at a red light. Actions are carried out via the medium of the physical universe—the body of a person performing an action moves, as when Nick’s arm moves into the air when the chairperson of his academic department “calls the question” at a meeting or when Denis’s vocal chords vibrate as he utters a loud noise (shouts) at an opponent at a meeting. (Sometimes an action is performed by a body ceasing to move, as when a pedestrian stops at a red traffic light.) But it should be apparent from these examples that the mere description of the physical events does not capture the actions as actions. Nick’s arm moving through the air could be a nervous twitch of some kind, and more is needed to describe it as an action; Denis emitting a loud noise could be involuntary coughing, and to regard it as an action would require more into the account.

Figure 4.1. Explanation of Why the Picture Fell

What is this extra ingredient that allows us to describe as an action what might at first appear to be solely a behavior? Several actions might involve exactly the same behavior-the person’s arm moves up into the air. In one case Nick was voting by raising his arm, in another case he was seeking recognition to ask a question, and in the third case he was seeking permission to leave the room. In another type of case his arm moved into the air because of a nervous disorder that had struck him. This last case is a behavior because it was not something that Nick consciously performed—it was a movement induced physiologically and was not performed voluntarily. In the case of the three actions, what constituted the same behaviors (movement of the arm) as being different actions was the differing meanings or purposes that were being conveyed in each case (and, we might suppose, for the sake of which Nick was performing each of them).

Some philosophers have expressed this, somewhat crudely to be sure, in a type of equation: action = behavior + meaning. (The term “meaning” is meant to be a placeholder for some item such as the meaning, intention, reason, goal, or idea that was being expressed by the actor or the purpose that the actor hoped to achieve. A lot of ink has been spilled by philosophers debating the technical details of this account, but we hope that the general sense of the distinction has been conveyed.)

We are now in a position to discuss some important issues that arise here for the social scientist and educational researcher. Again, nothing important hangs on our choice of the particular terms “behavior” and “action”—what is important is the distinction, not the words in which it is expressed. (Colloquially we often describe actions as behaviors—even when we are not Skinnerians!—as when we praise children for “good behavior”; conversely, scientists may talk about the “action” of water in a whirlpool.)

First, it is important to note that although natural scientists might be solely interested in behaviors (in their professional role) and in the laws or theories that can explain or predict them, the social scientist and educational researcher are rarely interested in mere physico-chemical changes (or lack thereof). What is of special concern to them are the actions performed by students, parents, teachers, administrators, policy makers, and others, as well as the sociocultural contexts that provide the framework of meanings and goals and purposes and values in which these actions are located. As educational researchers, we are concerned (among other things) with what students do and don’t do in classrooms, with the things that teachers do (and their reasons for so doing), the compromises that policy makers craft with each other (and what they hope to achieve by means of such compromises), and so on. The doings of students and of teachers, and the compromises reached by policy folk, all are actions, not behaviors (in the sense of the term defined above). We are also interested in the things or goals that are prized and in the values that are held—all of which are intimately related to the sociocultural settings in which the actors are located. Of course, as educational researchers we are not solely interested in actions; for example, we might be interested in the long-term effects of certain policies or in evaluating the effectiveness of specific educational programs and practices, or in the types of classroom organizational arrangements that are both educationally effective and cost-effective, or in the myriad factors that positively (or negatively) affect learning and motivation to learn. We shall return to these other foci of educational research at the end of the chapter. But it should be clear that human actions have a prominent place among the things that are of special concern to us because these topics—policies, programs, practices, organizations, and learning—rest on and grow out of individual and group actions.

Second, if you are performing an observational study in some educational setting, and you notice the teacher doing something that puzzles you—you can see her behavior but do not know what to make of it—the puzzle is resolved (or moves a long way toward resolution) at the same instant that you identify what the action is that the teacher is performing. Once you understand the meaning or goal or intention, you have identified what action it is that is being performed. (The teacher might be shouting and ranting in an apparently incoherent manner, and this puzzles you—what is happening? Then you discover that this is a unit on Roman history, and the teacher is trying to “set the class up” to understand the sense of confusion and discomfort that Romans felt when they were confronted with a mad authority figure, the emperor Caligula. Once you have identified the teacher’s actions as being a “teaching illustration,” the puzzle—or at least, that particular puzzle—disappears.)

Third, and crucially, there is a sense in which identifying the meaning (or purpose or intention or goal, etc.), and hence identifying the action, actually serves to explain it. Why is Nick’s arm moving up into the air? Ah, it is because he is voting for a motion before the faculty in his department; that explains it! Of course, it does not explain why he voted for the motion—he might well have kept his arm down and only raised it when the chairperson asked, “All those against?” But that is a different question. However, even to answer why he voted the way he did—why he performed that specific action—you again need to discover his reasons or motives or purposes or values.

What is being revealed here is a marked difference in the way in wkich an action and a behavior are explained. A behavior is explained by identifying the law or theory, or the causal structures in nature, that produced the behavior; an action is explained by discovering the reasons or ideas or motives, or so forth, that constitute it to be an action. Once we have identified that an object of a certain mass and velocity is in a gravitational field, we have explained why it is moving the way it is; once we have discovered Nick’s reasons for being in favor of the resolution that has been put forward in his faculty meeting, we have explained why he has voted for it.

The considerations, as well as the distinction, above have led some writers to argue that the study (and the explanation) of human action is nonnaturalistic; the natural science approach simply does not seem to work when human action is our focus. The argument, in outline, is this: Determining an actor’s reasons or motives or so forth is an interpretive or hermeneutical activity akin to what a humanist does when he or she, say, tries to understand the actions of a character in a novel or a play (see essays in Martin and McIntyre 1994, and also those in Connolly and Keutner 1988). But before we explore this line of argument further, we offer a more detailed educational example.

AN EXAMPLE: BENNY’S MATHEMATICS

Some years ago researcher S. H. Erlwanger (Erlwanger 1973) was out in schools studying a mathematics program called Individually Prescribed Instruction (IPI). His attention was drawn to a student identified by the teacher as perhaps slightly above average in ability whose behavior was puzzling. This young man, whom Erlwanger named “Benny,” was working quietly and confidently on problems concerning fractions and decimals. Notice that even here we have departed from describing the situation strictly in terms of behavior, for we have used an interpretive process and identified that Benny was “solving problems.” We have further identified these problems as involving “fractions and decimals” and thus have already started to talk in “action” terms and not strictly in “behavioral” terms. To identify ink marks on paper as being decimals, we have to understand the meaning of those marks, and “solving math problems” is an activity that has meaning in some cultural contexts but not in others. If we were to stick with behavior, we would simply have to say that Benny was sitting at a desk engaged in “writing behavior” or, more accurately still, engaged in “making black marks on paper”—a singularly unhelpful description of an educational situation! At any rate, what puzzled Erlwanger was that Benny often raised his hand when the teacher asked who had obtained the right answer to a problem, or he identified his answers as right when he looked them up in the textbook. Yet it was apparent to Erlwanger that Benny often had the wrong answer! Why was Benny doing this?

A person who was naively following the “physical science approach” would perhaps try to explain Benny’s behavior by finding the natural law that was operating that caused Benny’s hand to rise (often but not always) when the teacher emitted a certain noise. (Notice that we cannot say, within this framework, “when Benny raised his hand,” for this would be a conscious action on Benny’s part, and we are trying to explain his behavior; similarly, we cannot say “when the teacher asked a question,” for this would be to identify the teacher’s action and not the teacher’s behavior.) To put it mildly, this seems to be a most unpromising route to take! Alternatively, if our researcher were a behaviorist, he or she might try to determine the “schedules of reinforcement” that Benny had been subjected to, that had conditioned him so that upon delivery of an appropriate stimulus (a verbal stimulus from the teacher) he would automatically react by having his hand raised. This seems equally unpromising as a way of explaining what was going on.

Erlwanger seems to have made the reasonable assumption that whatever Benny was doing, he was doing on purpose—he was acting, not merely behaving. To understand and hence to explain what Benny was doing, he started to investigate not the laws of nature that might be operating but what the boy’s reasons were for claiming that his wrong answers were correct. The researcher asked Benny to explain how he was solving the math problems, and the payoff was startling! It seems that for whatever reason (perhaps he had been absent during a crucial lesson), Benny had missed out on some fundamental facts about the multiplication and division of fractions and decimals; confronted with this situation, he had attempted to make this area of mathematics meaningful to himself by inventing his own rules, ones that, as it turned out, occasionally produced the right answers. According to his own system, 2/1 + 1/2 was equal to 1, and both 1/9 and 4/6 were also equal to 1. Erlwanger was able to record the entire system that Benny had constructed and thus was able to explain the answers that Benny obtained to problems. But why did Benny claim that his (often) wrong answers were right? Erlwanger asked Benny about this, and the young mathematician explained (correctly) that answers could be stated in various mathematically equivalent forms (our language, not Benny’s), and he said that the textbook or the teacher was merely stating the same answer that Benny had obtained but was stating it in a different form!

In short, then, Benny’s actions—his arriving at puzzling answers to math problems and his marking them as being correct—were explained by revealing the beliefs that Benny had (the various meanings and reasons he had developed that bore upon decimals and fractions). His mathematical reasoning was wrong, of course, but Benny did not realize this; he was acting according to his understandings, and his actions were explainable (and only explainable) in terms of these (mistaken) beliefs and reasonings. Understanding Benny’s reasonings—understanding his actions rather than his bodily behaviors—was educationally productive, as it gave Erlwanger insight about what needed to be achieved to remediate the youngster’s work with fractions; sadly, however, Benny’s false beliefs had become so embedded by the time Erlwanger understood them that attempts to remove them were unsuccessful. The point here is that the agent’s reasons and beliefs, even if they are mistaken, are typically the only way to make sense of and explain his or her actions; and knowledge of the agent’s reasons is crucial if one is to plan an educational intervention. It should be clear that the level of insight we have achieved in Benny’s case would not have been attained had we used, for example, a positivistic behaviorist approach—which is not to deny that using rewards and punishments, which are typical parts of the behaviorist repertoire, might be useful in working with a student like Benny. The point, however, is that in order to get the right answers consistently to the math problems, Benny’s beliefs about the relevant mathematical rules had to change. Whatever methods were used to induce this, correct answers cannot be attained merely by making random marks on paper!

SOME BACKGROUND ON HERMENEUTICS

The mode of explanation illustrated in the case of Benny, which involved interpretive or hermeneutical activity on the part of the researcher, needs further discussion. In particular we need to grapple with the issue of whether or not such explanations can be scientific. (In the following discussion we shall use the terms “hermeneutical” and “interpretive” and their cognates interchangeably; one term has a Greek root and the other comes from Latin, but for our purposes they can be treated as synonyms.) But first, some background will be useful.

Historically, hermeneutics developed as the science of interpreting, or ascertaining the meaning of, sacred and legal texts (hence the reference to Hermes, the messenger and interpreter of the gods). Even in the ancient world there was some recognition that laws and sacred documents were written in earlier times and for earlier audiences, and that such things as the pronouncements of the Delphic Oracle had several layers of meaning. And so the issue arose of how the meaning of these important texts was to be determined for readers and communities studying them at a later date. During the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, the philosophical and methodological issues surrounding the interpretation of written texts were pursued with vigor and sophistication, and some of the conclusions reached continue to have ramifications for our own times (for a readable and brief history, see Odman and Kerdeman 1994).

To give a “gloss” on what is a much more complex story, in this latter period a theoretical move occurred that had great epistemological significance. It was argued that human voluntary action was a type of text, albeit a non-written form. Human action is laden with meaning (and meaning, of course, is a function of a sociocultural system). It is purposeful, and often it is symbolic and influenced by cultural beliefs and practices. When a researcher tries to understand what it is that a student has done, as when Erlwanger tried to identify or categorize Benny’s actions, the researcher necessarily has to engage in interpretive or hermeneutical activity even when, as is perhaps usually the case, such interpretation is undertaken without specific awareness that this is what is involved (it is to be doubted that Erlwanger was consciously aware that he was engaged in a hermeneutical activity with Benny). To express this point in terms that English-language philosophers of social science prefer, an action cannot even be characterized or identified (e.g., as defiance, as an expression of illness or mental disturbance, as grandstanding, etc.) until its meaning or purpose has been ascertained.

Paul Ricoeur (Ricoeur 1977) has suggested that face-to-face oral communication and human action directly observed are easier to interpret than written texts. In the former case the “author” or “actor” is usually present in front of the interpreter and can give nonverbal cues to amplify the meaning of the verbal ones as well as provide specific correction if the interpreter seems to have made a mistake—just as Benny did when he explained to Erlwanger how he “solved” problems involving fractions. There seems to be general agreement, however, that even in the case of observed action it is far from easy to determine how an adequate interpretation can be recognized. Taking only the easiest case—that of interpreting the meaning of a single, simple gesture—considerable difficulties arise, for (as we saw earlier in the example of Nick’s arm rising into the air) the fact is that all physical movements are ambiguous and could be described as constituting many different actions. (Note how parallel this is to the argument from chapter 1 that a set of data can be accommodated by more than one hypothesis.) The case of Nick’s arm is in fact a form of the classic example most frequently used by philosophers, and it nicely illustrates the issues. His arm rises; but is this action the asking of a question, the seeking of permission to leave the room, voting, the greeting of a friend or the saluting of a leader, or just a muscle twitch? Even in so simple a case, interpretation is required, guided by contextual factors and so forth. How are we to go about deciding which interpretation of the arm raising is the most adequate? What, specifically, are the relevant criteria by which interpretations are to be judged? And how much guidance is it reasonable to expect from the voluminous literature on textual interpretation when what we are dealing with is the interpretation of human actions (and actions much more complex than a simple gesture)?

To the uninitiated (or even, it must be admitted, to some of the cognoscenti) the issues that arise here are mind-boggling. Are the intentions of the author or actor important or can they be ignored? Are the agent’s espoused reasons always the best explanation for his or her actions? Is it sensible to suggest that there is an objective, “true” meaning or interpretation for every action? Are there as many valid interpretations as there are interpreters (as some have suggested)? Can any one individual, located as he or she is in a specific sociohistorical setting and armed with a specific set of theoretical understandings and interests, ever hope to “understand” the actions (including the spoken or written utterances) of another and almost certainly differently situated individual? (This problem is especially pertinent when the observer is from a different sociocultural group from the person observed.) Can inquiries or research projects that are at bottom interpretive in nature (and in educational research, many certainly are) meaningfully aspire to be “scientific”? Or are they more adequately thought of as humanistic endeavors? In the latter case, what features allow an interpretation to be judged as valid? Different writers give different answers to these questions; some even reject questions such as these on the grounds that they are misguided or are based on incorrect or outmoded assumptions. (See Connolly and Keutner 1988; Hiley, Bohman, and Shusterman 1991.) But now we need to turn to our own conjectures on at least some of these interrelated matters.

INTERPRETING HUMAN ACTION AND INTERPRETING TEXTS

There are some important similarities, but also some important differences, between the constraints on educational researchers and those on scholars who interpret literature. The discussion shall proceed in a more or less orderly way, point by point; gradually there should emerge a number of considerations bearing on the issue of whether interpretive work can be scientific (in a nonpositivistic sense of this term).

First, in the field of literary hermeneutics, it may well be the case that the concept of “truth” is inapplicable. Is there a truth (one truth) about the meaning of Hamlet’s famous soliloquy (“to be or not to be”)? Is it the musing of a grief-stricken individual or the raving of a man losing his mind? Should it be read as indicating a certain morbidity of spirit? Does Hamlet have what we now might call an Oedipal fixation? Do Hamlet’s words merely reflect the difficulties that individuals in Elizabethan England (including Shakespeare) had in dealing with death? There may be many “true” ways to interpret Hamlet’s soliloquy (just as there may be false ways), just as there are many ways to “truly” read it out loud (one of the present authors has, in his aging record collection, Sir John Gielgud, Sir Lawrence Olivier, and John Barrymore reading the speech, with surprising differences).

This matter has to be treated with care; at the very least, we would insist that if there are no true and false interpretations, there certainly are better and worse ones—just as Gielgud’s and Olivier’s oral interpretations of the passage arguably are better than Barrymore’s. (The complication here, of course, is that Barrymore belongs to a now distant age, and our strong distaste may well be subjective and simply display our own spatio-temporal location. It may indeed be a matter of taste rather than judgment! Despite this important complication, however, strong grounds can be presented for or against specific interpretations.)

But what about the situations commonly met by educational researchers, such as the problem of interpreting a classroom interaction between a teacher and a student in which (for example) the teacher appears to be severely criticizing the student? Is “truth” also an irrelevancy here? Something actually happened in the classroom, and we can give a true or false description of it. Furthermore, it might matter a great deal that we give a true account (the teacher might be sued for professional misconduct or fired for incompetence if we present one interpretation rather than another; or perhaps the teacher was using an experimental “push students to their limits” approach that, if judged a success, will be recommended to all teachers in that school district). In short, practical consequences often follow from the findings of educational research, and it behooves the researcher or evaluator to be certain that his or her account is not fiction and is not merely “one reading” of many that are theoretically possible concerning the situation under investigation. It should be a good reading, a true reading. To revisit the case of Benny, it seems clear that Erlwanger was trying to give a true account of what Benny believed the rules about manipulation of fractions and decimals to be, even if the youngster’s rules were not valid. Benny of course believed these rules to be true and was acting on them (recall the discussion of the issues about true and false belief in chapter 2). What would have been the point of Erlwanger giving a false account? He wanted to understand the real reasons for Benny’s acting the way he did; he also wanted to understand properly in order to be able to help the student improve. (His account was clearly superior to one suggesting that Benny was acting arbitrarily or out of total ignorance of mathematics.)

Second, many confusions and red herrings can appear at this stage of the discussion, one of which was discussed briefly in chapter 2: those who believe (as we do) that researchers should aim to discover the truth are often accused of thinking that there is one (“absolute”) truth.

But this is of course nonsense. Even in the literary example, several of the supposedly rival interpretations of the soliloquy actually can be true at the same time—they are not all mutually incompatible. In the classroom example involving the teacher criticizing a student, the teacher might be exercising legitimate authority, might be trying to encourage the student or set higher standards for performance, or might be expressing ethnic or sexist bias—or doing all at the same time! But whichever of these accounts of the teacher is put forward, it ought to be shown (as far as possible) to be true—for it is either true or not true that the teacher was trying to encourage the student (whether or not the actions actually achieved this) or that the teacher was ethnically biased, and so on.

Another red herring (also discussed earlier) is the argument that as the truth can never be known by mere mortals, there is no truth; as we cannot know for certain which interpretation is true, in many cases, then the notion of truth has to be abandoned. If we follow this line, we quickly arrive in the murky realm of multiple but incompatible beliefs (and even multiple incompatible realities; see Guba and Lincoln 1982; Manke 1996) about situations, all of which have to be accepted. We can do no better here than refer anyone who accepts this strange argument to philosopher John Searle’s book The Construction of Social Reality (1995). Searle shows that the inability to decide which of several views is the correct one does not establish either that there is no correct answer or that a relativistic theory of “multiple realities” is credible. Belief in reality and in truth is not undermined by epistemological uncertainty about which account of reality is warranted.

Third, in the field of literary hermeneutics there has been a longstanding debate about the importance of authorial intent—about whether or not it is part of the interpreter’s role (or a necessary part of developing an interpretation) to decipher the intent of the text’s author; currently it is quite modish to hold that the purposes of the author are irrelevant (see Connolly and Keutner 1988; Fish 1980). In interpretive educational research, we suggest, the intention of the actor (the act’s “author”) is nearly always one important factor that needs to be considered.

Consider the two examples introduced earlier: An interpreter trying to understand the meaning of Hamlet’s famous soliloquy and a researcher trying to understand the meaning of a teacher’s puzzling interaction with a young student of a different ethnic background. In the literary case, it is at least coherent to argue that whatever Shakespeare had in mind is quite irrelevant; the meaning of the passage is not constituted by whatever intentions Shakespeare might have had. The words of the soliloquy are there and are “open”—we might see meanings in them that Shakespeare did not consciously intend to put there, for of course Shakespeare himself was writing under sociocultural influences of which he might not have been aware but might have influenced what he wrote—how he depicted the character of the prince of Denmark, for instance. Furthermore, we are reading the passage from our own sociotemporal location; we have several hundred more years of human history under our belts, and we have new insights into human nature available that the Bard didn’t (e.g., Freudian theory which we can bring to bear upon Hamlet’s musings). In light of all this, it certainly is not foolish to maintain that literary interpretation is open-ended. It might well be misguided (as was suggested in the preceding point) to seek “the true interpretation.” We are free—according to this line of thought—to impose or overlay our meanings on the soliloquy (just as Stanley Fish famously asked his students to provide interpretations of a “poem” on the chalkboard that was actually scribbling from a previous lecture to a different class). In short, it is credible to maintain that the soliloquy has the meaning that we, individually, give it; its meaning is imposed or constructed and not found (see Fish 1980).

Whatever the merits of this position in the sphere of literary interpretation, it appears to be quite misguided in many educational research settings. In the example foreshadowed earlier—a teacher acting in a certain way toward a student—understanding what has transpired is not a matter of imposing our own meaning or interpretation on the situation. The problem for us researchers (assuming we are doing educational research and not gathering ideas for a novel) is, first, to comprehend what the teacher thought she was doing (after all, it was the teacher’s action, and unless we understand her reasons and intentions, we do not even know what sort of action it was) and, second, to understand how the recipient, the student, interpreted the situation (for the student will react not to our interpretation of the situation but to his or her own interpretation of what the teacher was doing). In neither case are we free to impose any interpretation that we fancy, for we were not the actors involved in this situation; any account we develop as researchers has to be strongly constrained by the truth about those events in the classroom. Putting it in terms of the first major point made above, there is a “truth of the matter” here that (depending on the purpose of our research) it is our job to uncover if we can. The teacher meant something, and the student took it in some way or other; we can get these things right or we can get them wrong! To cling to this insight is to take the first step, not to the rigor mortis of relativism but to the rigor that is needed in a competent inquiry.

Fourth, the complexities of the sort of case we have just outlined are not always clearly teased apart by interpretivists. To make matters worse, there might be a third thing for us to do here. As researchers, we might wish to gain deeper theoretical insight into how and why situations of this type arise (e.g., why teachers of one or another ethnicity sometimes act in this way toward students of different backgrounds). It is tempting but quite misleading to describe this task as being an interpretive one. It is more accurately described as one involving theoretical explanation or analysis; having correctly interpreted the actions in the classroom, we might want to push to the level of theoretical explication. (The word “interpretation” is often used colloquially in this loose way, as when a television commentator offers an “interpretation” of some political or economic news, when what the person really is offering is a tentative hypothesis or explanation of the event in question; or perhaps it is a prognosis of what later events might unfold as a consequence of this one.) We believe it is wise to recognize that not every task that we undertake in research involves interpretation, and those who think that it does will be found to be using this term (or its cognate forms) in several different ways. (See Phillips 1992, chap.1, which distinguishes strong and weak senses of “interpretation.”)

Fifth, we can now address the issue of whether interpretive work aimed at elucidating human actions can be scientific (in the broad sense of “scientific” accepted by postpositivists). The most fundamental point is this: In both the literary and educational cases discussed above, the interpreter or researcher must have some competently gathered evidence—some warrant—to back up the interpretation (or “reading of the situation”) that is being given. In the case of Hamlet, the interpreter will appeal to the language of the soliloquy and perhaps to the usages and linguistic forms of the Elizabethan period. Appeal might also be made to other incidents and speeches in the play that illuminate Hamlet’s character and state of mind or have significance in the light of such things as modern psychological theories that the interpreter might be disposed to use. Philosopher Dagfinn Follesdal has shown, through careful detailed analysis of a similar literary example, that the logic used in such cases is the so-called hypothetico-deductive method commonly found in the sciences (see Follesdal 1979). As we saw earlier, this is the method of forming some hypothesis, deducing its consequences, and “testing” it by looking to see if these consequences actually occur. If they do not, or if evidence that is not compatible with the hypothesis is found, then the hypothesis must be rejected as it stands.

In the education example we have been using, the researcher developing the interpretation will refer to the words (and other actions) that actually passed between the teacher and the student in the classroom but may also note the manner in which they were spoken and the body language accompanying them. But the broader context of the classroom and its makeup, and the history of the relations between teacher and student earlier in the school year, can also be sources of evidence that support the interpretation. The act of culling through this material might yield theoretical insights from various social sciences that can also be used. Finally, the educational researcher can have recourse to interviews with the teacher and the student, in which they are each asked to give an account of what happened in the classroom and what their thoughts were at the time. In collecting this evidence, the researcher will be alert for data that challenges the interpretations given by the teacher and the student and may even challenge his or her own favored view of what had happened in that particular incident.

Sixth, several points can be made that further develop the ways in which interpretive research can be expected to meet the canons of postpositivistic science:

- Both the interpreter of the soliloquy and the educational researcher are expected, by their peers and in accordance with the canons of their respective professions, to offer evidence (or warrants) to underwrite the interpretations that they put forward. Here “underwrite” means something like “indicate that the interpretation is likely to be true.” An unwarranted interpretation is merely a speculation.

- It is always possible, out of the masses of material available, to select some items that apparently support a given interpretation, and thus the fact that the account is apparently supported by some evidence does not count for much. (As Karl Popper remarked, any fool can always find some evidence to support a favored theory.) What serves as more genuine support is that no evidence can be found to disprove the account that is being given; it is up to the person giving the interpretation to convince the rest of us that such negative evidence has been sought vigorously. In previous chapters we stressed that all of us have beliefs that may be based on some evidence but are nevertheless wrong. (For more discussion of the relevance of this aspect of Popper’s work for educational research methodology, see Phillips 1999.)

- In both the literary and schoolroom cases, the actual interpretations that eventually are produced are themselves literary products (essays, research reports, conference papers, and so forth), but their quality as interpretations is judged by what they tell us about the objects or events under examination; their quality as stories or literary products is epistemically irrelevant. Thus the interpretation of the soliloquy is judged by how well it squares both with the words that Hamlet uttered and with other passages in the play; the account of the classroom incident is judged by the veracity of what it tells us about the words and actions in that classroom. Neither interpretation can be judged by qualities purely internal to it as a literary artifact, such as how well it is written, the seductiveness of the plot of each interpretation, and so forth. The failure to escape the internal confines of the research artifact bedevils so-called narrative research (see Phillips 1994, 1997).

- What we are getting at is found in a paper by Yvonna Lincoln with the engaging title “Emerging Criteria for Quality in Qualitative and Interpretive Research,” which appeared in the journal Qualitative Inquiry (Lincoln 1995).

Unfortunately, by our lights Lincoln does not discuss at all the main criterion for interpretive inquiry in education; she never mentions the requirement that an interpretation should be borne out by the evidence—that it should have withstood the search for negative or refuting evidence. But she is not alone; in her paper she cites a report delivered at the annual conference of the Society for Psychotherapy Research in 1993 that gave nine guidelines for “judging qualitative research that is submitted for publication.” While she has a criticism to offer, she opines that “most of us would agree that these are strong criteria or standards.” In light of our previous comments, it should be clear that one can dispute both the criteria and Lincoln’s generally positive evaluation of them:

(1) Manuscripts [must be] of archival significance. That is . . . [they must] contribute to the building of the discipline’s body of knowledge and understanding. (2) The manuscript specifies where the study fits within the relevant literature and indicates the intended contributions (purposes or questions) of the study. (3) The procedures used are appropriate or responsive to the intended contributions (purposes of questions posed for the study). (4) Procedures are specified clearly so that readers may see how to conduct a similar study themselves and may judge for themselves how well the study followed its stated procedures. (5) The research results are discussed in terms of their contribution to theory, content, method, and/ or practical domains. (6) Limitations of the study are discussed. (7) The manuscript is written clearly, and any necessary technical terms are defined. (8) Any speculation is clearly identified as speculation. (9) The manuscript is acceptable to reviewers familiar with its content area and with its method[s]. (Elliott and colleagues, quoted by Lincoln 1995, 279)

- It might be argued that we have been a little harsh here, for surely the first criterion—being of “archival significance”—covers the point that is of concern to us, as does the third—the methods have to be “appropriate.” But the passage quoted makes no mention of how this “significance” or “appropriateness” is to be determined. At the very least one might expect that somewhere in the long list of criteria the quality of the evidence or warrants that are offered could have been mentioned, together with the appropriateness and logical rigor of the design that was followed, the questions that were asked, the observations that were made, and the steps that were taken to eliminate rival hypotheses or interpretations. The failure to list things like this suggests that they play no important part in judgments of quality of interpretive research; certainly they cannot be assumed to be so obvious or so widely endorsed that they do not need to be stressed! (It is noteworthy that in this set of criteria the only specific point that was made about the procedures used in the study was that they should be clearly enough described for others to follow them if they so desired; the issue of whether the procedures were scientifically appropriate and were likely to produce an epistemically appropriate warrant was ignored.)

- Finally, it seems to us that it behooves all interpretive researchers—whether they labor in literary or educational fields—to borrow a concept from traditional research methodology (that some would erroneously label as “positivistic”), namely, the notion of threats to validity. This notion originated in the fields of experimental and quasi-experimental research, in which conclusions about the effectiveness of treatments are inferred from bodies of data; however, if the experimental studies that produced these data were poorly carried out, then various threats to validity might operate that would affect the soundness of the conclusions that are reached. For example, if unmonitored and nonrandom attrition occurs from the experimental group or from the control, then the validity of the inference that the treatment produced whatever results were obtained is seriously undermined (for the “results” might be a result of the attrition, not of the treatment).

It is extremely fruitful to apply the notion of threats to validity to interpretive work. Even in literary studies, the validity of an interpretation can be undermined by such things as failure to study the language carefully or failure to consider the bearing of other parts of a text on the passage that is under present consideration. In educational field settings, the notion of threats to validity is even more important; misuse of power and the display of status by the researcher (the kinds of things that Yvonna Lincoln and others rightly are concerned about; see Lincoln 1995) can certainly undermine the quality of the data that are obtained and can thus invalidate any conclusions that are reached. But so can allowing a “mental set” to develop that biases the interpreter by blinding him or her to negative evidence (this is a well-known threat to the validity of qualitative research; see Sadler 1982); and so can the adoption of a confirmatory rather than a disconfirming mind-set (i.e., the tendency to look for positive or confirming evidence rather than evidence that disconfirms the researcher’s hypothesis). Too rarely do qualitative researchers (particularly but not solely beginning researchers) think in terms of disciplining themselves to guard against these and other threats. If they were to do so, their work would indeed be more rigorous and more “competent”—and it would be “scientific” in the quite benign postpositivistic sense of the term.

Seventh, our conclusion, then, is that Skinner was wrong: There is nothing unscientific about an educational researcher studying human actions (not merely behaviors) and seeking to understand the reasons, beliefs, motives, purposes, and so forth, that lead individuals to act they way they do in educational and other social settings. Of course, these things can be studied in an unscientific way—when appropriate evidence is not collected, when disconfirming evidence is not sought, when hypotheses favored by the researcher are advanced without competent probing and evaluation, and when threats to the validity of the study are ignored and not countered. We researchers are human beings, and the beliefs we form are liable to be erroneous. The scientific spirit—the postpostivistic scientific spirit—is that, no matter what our inquiries are about, we should do as much as humanly possible to ensure that our beliefs are well-founded, and as Dewey said, this comes via carrying out “competent inquiries.” In the words of one of Dewey’s own teachers, nineteenth-century philosopher and scientist C. S. Peirce:

A hypothesis is something which looks as if it might be true and were true, and which is capable of verification or refutation by comparison with facts. The best hypothesis, in the sense of the one most recommending itself to the inquirer, is the one which can be the most readily refuted if it is false. This far outweighs the trifling merit of being likely. For after all, what is a likely hypothesis? It is one which falls in with our preconceived ideas. But these may be wrong. Their errors are just what the scientific man is gunning for more particularly. (Peirce, n.d., 54)

OTHER FOCI OF EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

The preceding discussion focused on human voluntary actions and the mode of explanation that is appropriate for them in terms of the reasons, purposes, meanings, beliefs, and so forth, of those who are performing those actions. Undoubtedly such actions constitute an important part of what is of interest to us and affects us in our lives as members of human societies and as educationists. But we have erred if we have given the impression that actions form the entire subject matter of educational and social science research.

Some distinctions will prove helpful in structuring the following discussion. Virtually by definition actions have intended consequences, but it is crucial to note that they also have unintended ones; furthermore, actions are affected by a variety of sociocultural and environmental factors. Finally, actions can be considered microlevel phenomena, but there also are many macrolevel phenomena occurring within society. Educational research can focus on any one (or more) of these—and the way they are studied is different from the way in which it is appropriate to study actions themselves.

First, intended consequences are the ones for which the action was performed; a consequence of Denis’s putting up his umbrella was that he was sheltered from the rain, and he intended this to happen; it was the very reason why he performed the action of opening the umbrella. However, as the umbrella opened it poked Nick in the eye; Denis did not intend this to happen (it was an accident), but nevertheless it was a consequence of the action, and in fact it was a more serious consequence than the one he intended! Karl Popper maintained that it is frequently the case that the unintended consequences of our actions are of more importance and significance than the intended ones; often we remain blissfully ignorant of them even after they have occurred, not realizing that they were consequences of what we have done (and we certainly did not predict that they would happen).

It is almost a platitude in the field of evaluation of educational and social programs that the side effects (i.e., the unintended consequences) of a program are often more important than the effects that the program was designed to produce. Unfortunately, it is frequently the case that the main intended effect does not materialize, but often the program still has major unintended (and unpredicted) consequences, either negative or positive. A school lunch program might not produce the consequence that was intended by the school board—significant improvement in the level of nourishment of students—but it might serve as a jobs program for members of the community and thus indirectly affect the well-being of some students in ways that the members of the board neither realized nor intended. (Unintended consequences can be either positive or negative, of course. A needy student’s parent obtaining a part-time job related to the lunch program is probably positive; the lowered performance of some students after the lunch period, if it occurred, would be negative.) This illustrates the fact that documenting and precisely measuring the consequences of educational policies and actions can be an important aspect of educational research (often with major policy implications), and this might not involve the researcher in hermeneutical work at all (or at least, not the degree of it that is involved in trying to understand the actions of an individual or a committee or a policy-setting board). What it requires is a method of observing consequences and tracing lines of causation back to policies or choices that may not have had these consequences as an aim (see, e.g., the voluminous research on the “hidden curriculum” of schools).

To use another example, documenting the effects of introducing an educational voucher scheme into a state might be an important research activity and might involve determining the types of schools to which families of different socioeconomic status (SES) or ethnicity send their children; this research might even produce generalizations that are rather similar in form to those found in the natural sciences (perhaps something like “the probability of a child from socioeconomic background X remaining in a public school until graduation is Y”). This sort of research is different from research aiming to understand the reasons for a particular family with socioeconomic background X deciding to leave their child in a public school. The latter is unambiguously a project involving interpretive methods whereas the former is not.

Second, the actions of educators and the enactment by individuals of educational policies and practices take place in specific sociocultural settings that affect both the actions and their consequences. Even the physical environment can affect actions and their consequences (a teacher’s action that might pass almost unnoticed by the pupils in cool weather might provoke a riot when the classroom is unbearably hot and humid, and the way the teacher actually acts might be shaped by the temperature or other conditions in the classroom). Once again these things can be the focus of the researcher’s attention, and in many cases interpretive methods will not be appropriate to use. Consider another case: A researcher might be studying the mathematics education of girls in Japan as compared with those in the United States. The educational practices with respect to math will probably be influenced by the differing roles of women in these societies, by the economic opportunities available, by family and societal values, and so forth. Studying these factors, and how they influence the treatment that girls receive, is not necessarily a hermeneutical activity, although aspects of the research could be framed so that they are hermeneutical.

Third, in some respects individuals and their actions can be regarded as the microlevel in society, just as for some purposes atoms or perhaps quarks can be regarded as constituting the microlevel in physical nature. Although at the microlevel in society we have individuals acting, it is important to note that not all microlevel phenomena involving individuals require that we seek their reasons, motives, or beliefs for acting. For example, we could collect test scores (without worrying about the reasons why students answered the tests the way they did) and analyze them, or we could tally which individuals dropped out of high school and relate this to their SES levels or ethnic backgrounds or IQ scores (again without being concerned to discover the reasons that the individuals concerned gave for dropping out).

It will hardly come as a surprise that in addition to the microlevel, there is a “macrolevel” as well or, more accurately, there are several such levels. Thus, in the physical universe there are atoms that are made up of quarks, molecules that are made up of atoms, complex compounds that are composed of different types of molecules, biological organisms that are made up of complex compounds, and ecosystems that are made up of various biological organisms. There are also artifacts or effects produced by organisms or physical objects (landslides, beehives, nests, dung, the destruction of forests or grasslands). Similarly, in the human sphere there are individuals, groups made up of individuals, and complex societies made up of groups, but there also are organizations (the Senate, the Marine Corps, the Ford Motor Company, the local school board), humanly produced artifacts (bridges, freeway systems, schoolrooms), and of course such things as customs, laws, and norms. Of particular interest, as we shall see below, are the macrophenomena that are in some sense the resultants or “sums” of the actions of individuals.

The methods appropriate for investigating phenomena at one level in nature might not be appropriate for working at other levels. The conceptual apparatus might need to be different at each level, and the laws and theories applicable at one might not be applicable at another. Thus, in the physical universe, the subatomic realm is marked by randomness and unpredictability, yet at the macrolevels there are the substantial regularities we call the “laws of nature.” In a sense, these macroregularities result in some way from the randomness at the lowest microlevel. The methods, concepts, and theories used by organic chemists, population geneticists or ecologists are not the same as those used by particle physicists or cosmologists. Paralleling all this, we can think of lawlike regularities that occur in the human realm as a result of the random voluntary actions of large numbers of individuals at the microlevel, and different methods are required for the study of these different phenomena. For example, at the microlevel Nick and Denis and their spouses and friends spend their income in the ways they individually see fit, and these ways may be quite different. Yet at the macro or societal level the disparate spending patterns of individuals may be describable in terms of regularities that are codified in the so-called laws of economics (and the methods appropriate for studying these micro and macro phenomena are quite different). Discovering these macrolevel regularities and the factors that influence them is an important facet of social science and educational research, and it can look remarkably like research in the natural sciences.

Many economists, macrosociologists, organizational theorists, political scientists, and comparative educationists are professionally concerned with the happenings and regularities at the macrolevel in society and also across societies (such things as dropout rates and their relationships with ethnicity or SES; the difference in economic and educational attainment between “voluntary” and “involuntary” migrant groups to a country like the United States; entry rates of women into the science-related professions; societal and economic factors that influence the introduction of compulsory education laws in third world countries). We must not forget, either, the work of many psychologists who focus on aspects of learning, motivation, memory, and so forth, that all humans have in common; much work in psychology is reminiscent of research in areas of biology—one thinks of Piaget and his influential stage theory of cognitive development that he believed applied to all humans in all cultures. There is no reason in principle why such macrolevel educational research cannot be naturalistic, and this is why there is an important place in the training of educational researchers for instruction in descriptive and inferential statistics, sampling theory, experimental and quasi-experimental design, mathematical modeling, the use of observational techniques, the rigorous analysis of qualitative data, the construction of tests and measures, and the rest.

Part of the postpositivist view of research, as we have presented it here, is a certain pluralism of method. It is not the particular type of research that makes it scientific, on this view. One can study individuals or groups; one can study personal actions or patterns that appear at a higher level of social aggregation or organization; one can study intentions or unintended consequences; one can pursue experimental, interview, observational, statistically oriented, or interpretive research—or some combination of these (even if some will say these can’t be combined). The postpositivist approach to research is based on seeking appropriate and adequate warrants for conclusions, on hewing to standards of truth and falsity that subject hypotheses (of whatever type) to test and thus potential disconfirmation, and on being open-minded about criticism.

AN EXAMPLE OF NONINTERPRETIVE RESEARCH INVOLVING MICROLEVELS AND MACROLEVELS

In 1997, Valerie Lee and Julia Smith published the paper “High-School Size: Which Works Best and for Whom?” (Lee and Smith 1997). They built upon earlier theoretical and empirical work, much of it coming from the “school restructuring” literature, which suggested that students learn more in small high schools and that learning was more equitable in these settings (in the sense that the gap in performance between white and higher SES students, on one hand, and minority and lower SES students, on the other, was narrower in such schools). But the amount of evidence was not great, and there was the unresolved issue of just how small a school had to be to maximize this effect; there also were issues about the precise size of this effect for various social groups.

Lee and Smith made use of a national data set known as NELS:88 (“National Education Longitudinal Study 1988”); these data had been collected on a large number of students across the United States, and these had been collected from the same students when they were in eighth, tenth, and twelfth grades. (The data included information about the schools of the students, their SES and ethnic backgrounds, and their scores on “objective tests” in various subjects including mathematics and reading, the two areas on which the researchers chose to focus.)

The investigators took data from NELS about students who stayed at the same high school until graduation, about whom there was sufficient data to validate the proposed analytic methods. Their sample contained 9,812 students from 789 public, Catholic, and elite private high schools. They then made a number of sophisticated statistical adjustments to deal with certain problems, such as the fact that certain categories of schools and students were “oversampled” by the procedure outlined above, and therefore their initial sample was unrepresentative of the population as a whole. Of course they had to analyze students’ test scores to “capture students’ pattern of performance in terms of number correct on an estimated continuum of items scaled by difficulty level and equated across grades and forms [of the tests]” (Lee and Smith 1997, 209). (Difficulty level is not determined by asking students about their beliefs or judgments, for researchers regard this as too “subjective”; rather, “difficulty” is defined “objectively” in terms of percentages of students who get an item wrong. We have put “scare quotes” around several terms here that some would want to question, but clearly there is something to be said for this widespread research practice, and indeed it has proven to be fruitful.)

Another important methodological aspect of the study was developed in response to the fact that high school enrollments vary. They do not come conveniently divided by nature into groups containing the same number of students but technically constitute what is known as a “continuous variable.” Thus the researchers had to decide on what categories to form, and they settled on “schools with 300 students or less,” “301–600,” “601–900,” “901–1,200,” “1,201–1,500,” “1,501–1,800,” “1,801–2,100,” and “over 2,100.” Finally, Lee and Smith used a technique of statistical analysis known as hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), and their findings were presented in tables and graphs, with accompanying discussions. (Obviously, we cannot reproduce all of them here, but their data, and their analyses, are reported quite fully for the inspection of their scientific peers. As well as the tables and graphs reporting the results, there are almost four and a half pages of technical appendices). They summarized their findings in the abstract to their article:

Results suggest that the ideal high school, defined in terms of effectiveness (i.e., learning), enrolls between 600 and 900 students. In schools smaller than this, students learn less; those in large high schools (especially over 2,100) learn considerably less. Learning is more equitable in very small schools, with equity defined by the relationship between learning and student socioeconomic status (SES). (Lee and Smith 1997, 205)

Lee and Smith were evidently not trying to understand the actions of individual students using hermeneutical methods; rather, they were studying the difference in test scores across a particular category of social institution (i.e., schools), the members of which varied in size. We may say that the study as a whole focused on the relation between macrolevel and microlevel phenomena (between school size and individual performance on tests in certain subjects) and was naturalistic through and through. Compare it with a study in which, say, an agricultural scientist examines the milk production from different types of cows that are feeding in fields having different herd densities. Unflattering as it may seem, there appears to be no significant difference in general logic between the two studies! It is also evident, however, that Lee and Smith documented something that has great relevance for policy: If we are about to construct new schools, we ought to give some thought to limiting their size.

But what are we to make of the suggestion that school size is a causal factor? How can size of the school population cause increased or decreased learning to take place in individuals? Lee and Smith are quite clear about this, and relatively sophisticated:

We suggest that the effects [of size] on learning are probably indirect, mediated by their influence on basic features of the academic and social organization and functioning of schools (variables that were not in our models). Under this explanation, size serves as a facilitating or inhibiting factor for fundamental educational processes in schools. (Lee and Smith 1997, 219)

In other words, Lee and Smith were acknowledging indirectly that learning is an action of students. Their study throws light on an important factor that can influence individuals, but their study does not rule out the possibility that other studies would be fruitful. We can imagine that useful studies could be performed using other methods, such as “shadowing” or interviewing students in different-sized schools, studying the interactions among students in large and small schools, or cataloguing the different range of educational opportunities that exist in schools of different sizes. All these studies would complement each other—they would not be rivals. This underscores the moral that there is no one favored type of study for the postpositivist—what type of study is best depends on the problem or issue that is under investigation; on important matters it is possible that studies of different types can make a contribution. What is crucial is that, whatever methodological approach is adopted, the study be rigorous, or as Dewey would say, “competent.”

A NOTE ON CAUSATION IN THE SOCIAL WORLD

Lee and Smith are to be admired for having realized that their work raised an issue about causation: Can school size be a causal factor influencing something like student achievement? Scholars who see society only as a site for human action and disregard or do not see anything else of importance are likely to believe that it is a serious mistake to adopt a naturalistic view of causation in the social sciences. Their model is much closer to the notion of causation that is to be found in many (but not all) works of literature. Some of the events in the last part of Sean O’Casey’s famous play Juno and the Paycock can serve as a typical example. When the daughter is discovered to be pregnant, her father interprets her pregnancy as an affront to his standing in the community and threatens to throw her out of the house (his reaction is shaped, to some degree, by the fact that this is the only one of his several misfortunes that he can do anything about). His wife says that if he makes good on his threat, she also will leave; he then decides to go to the pub to have a drink with “the few friends he has left.” Here the actions of each individual are interpreted by the others and thus have meaning for them. Each individual then reacts to these perceived meanings by performing actions that in turn are interpreted—and then reacted to—by the other characters. To use a famous expression coined by anthropologist Clifford Geertz, the characters are caught up in webs of meaning that they themselves have constructed—a phenomenon that looks quite unlike the operation of causal chains in the physical domain.

Despite the attractiveness of this analysis, we insist that there are many causal chains operating in the social realm, at both the microlevel and the macrolevel, which can be studied naturalistically. Indeed, a regular causal analysis is not completely out of reach even with the sorts of events depicted in the play, events that clearly involved the actions of individuals at the microlevel. There are several points to be made here.

First, in a straightforward sense, we can say that the father’s actions helped cause the reactions of the other characters, who were part of the causal nexus that was operating. If he had acted differently, a different set of reactions probably would have ensued. Fathers, no less than anyone else, constantly shape the actions of others—and often do it quite deliberately. All of us influence others and find them understandable and predictable, because in general their beliefs and desires and interpretations of their situations are causally related to the ways they act; we influence their actions by changing or “manipulating” these things. This is not to say that if a father act in manner A, his daughter will necessarily act in the manner B that he had predicted. But even if she doesn’t act this way, his doing A still was part of the reason she did what she did do (it was part of the causal nexus, and possibly it played a necessary part in leading to what she did do).

Second, in the paragraph above we used language that was chock-full of references to causation; sometimes this was thinly disguised, but it was causal nonetheless. An action is likely to lead, we constantly shape, and we influence—all these are causal expressions. Family therapists intervene and try to change the ways family members act, for they realize (perhaps only partly consciously) that such changes will produce other changes (will produce is another causal expression). Social life would become impossible if causation of some sort did not exist. Mario Bunge put the point nicely:

Rational action and the rational discussion of it are among the features that distinguish society from nature, and consequently social science from natural science. However, this distinction should not be overdone, for reason is impotent without causation. (Bunge 1996, 36; emphasis added)