12.

Serpent Skin

I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids.

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

A man without tattoos is invisible to the gods.

—Iban Proverb

Bleed in your own light

Dream of your own life

I miss me

I miss everything I’ll never be

—Smashing Pumpkins, “Rocket”

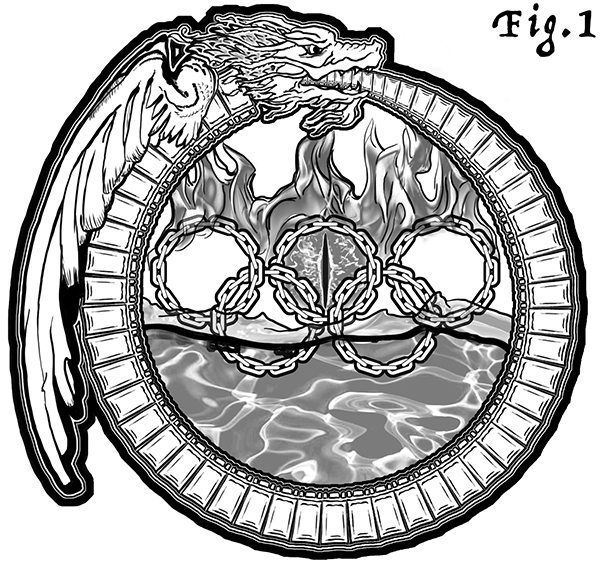

Many first-time Olympians head to a tattoo parlor right after they’re done competing to get inked with the ceremonial Olympic logo. For once, Ervin chose to go with the flow. The day after swimming ended at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, he rallied a few guys on the national team and they went and got the five interlocking rings of blue, yellow, black, green, and red. Although he wouldn’t stop at just that single tattoo, as so many Olympians do, for years it would remain his only one. That ink was about camaraderie, a badge of membership. Situated on the left side of his upper back, his Olympic rings are now the smallest and least striking of his tattoos, although they also happen to reflect the experience for which he’s most famous. They would later be rendered practically invisible by a canvas of tattoos that had nothing to do with competitive swimming. But that would not come for another three years, not until after the 2003 Barcelona World Champs.

Every time I travel I move as if in an army, with managers, teammates, trainers. So after Barcelona World Champs I say to hell with it and change my flight to spend some days alone in Catalonia and then Amsterdam. It’s my first time traveling solo. I take the train from the airport to Amsterdam Centraal, which from the outside looks like a royal palace, although the surroundings are seedy. A homeless-looking guy approaches me, probably in his midtwenties. He’s acting relieved to meet me because, he claims, no one speaks English in Amsterdam. Then he says he’s just been robbed and has nowhere to stay and asks me if he can stay with me for one night. When I say sorry, he tells me to fuck off under his breath and slinks away.

I walk toward the center. Everyone is tall, attractive, and riding vintage bicycles. As I soon find out, almost everyone speaks English. I get a bunk in a hostel. Across the street is a coffee shop called Grasshopper. It serves alcohol, coffee, and weed. And there are computer games. The essentials of life. I hunker down there for the rest of the afternoon, smoking weed and playing DotA. I could open a place like this.

The next morning I walk to a tattoo shop. I tell the guy I want a star within a star on my left elbow. I got the idea in Barcelona a few days ago from a backpacker. She was walking away from me, so I couldn’t see her face, but on her elbow was a tattoo of a star. I’d known I wanted tattoo sleeves for a long time, but I didn’t know where to start. Something about the star caught my eye, drew me in. That’s me, I thought, a traveler. I don’t know who she is and I don’t need to. And people don’t need to know who I am. I’d start there and let the other tattoos follow. To make the tattoo my own, I decided on the star within a star.

The tattoo artist doesn’t come in until noon and it’s only nine so I book the first free slot and head out. After a few hours I wander into a head shop. There are mushrooms on sale, listed by strength. The most potent are tiny ones called Rambo. I tell the guy I want those. He eyes me, sussing me out.

“Where are you from?” he asks.

“USA.”

“These are really strong. Sure you want them? Have you had mushrooms before?”

I nod and give him cash.

“Well, just don’t eat them all,” he says, handing them to me.

He thinks because I’m American I can’t handle strong mushrooms. So I open the pack right there at the counter and eat them all. He’s just looking at me, shaking his head. Then I walk out.

The mushrooms start coming on as I enter the tattoo shop. A guy is getting his arm done. He has an Asian dragon on his shoulder coming down to his elbow. It looks alive. Fresh tattoos really pop, and not just the colors—they literally pop out because of the swelling that the needles cause—so this combined with the mushrooms make his dragon look 3-D and alive. I know something large like this is the next stage for me. Watching him is like seeing myself in the future, like a higher-evolved, tattooed version of me. When I trip, I see myself in everything.

The session is painful, but the mushrooms give me an unexpected calm and confidence. By the time I leave the tattoo parlor I’m really zooming. The mushrooms start to overwhelm me. That guy wasn’t overplaying the power of Rambo. The colorful row houses all jut up weirdly and lean over the canals at crazy angles like crooked discolored teeth. I’m walking through a Van Gogh painting. Standing in a parlor window and suffused in red light, a mannequin in lingerie suddenly comes to life and waves at me. I flinch, recoiling. Next thing I know, there’s a whole row of red parlor windows in which half-naked women leer at me like predatory circus exhibits. But there’s sorrow there too. A woman’s palm against the glass troubles me. I stumble off down bizarre and byzantine side streets. People pass by me, murmuring and babbling in foreign tongues.

Maybe I’m in hell. This rings in my head like a joke, but it feels real too. I need protection. Across the street I see a store called 666. It must be a sign. It’s a sunglasses store. Protection against demonic entities. I buy a pair of rave glasses in a light shade of pink. I walk out in them, feeling much better. Now I’m protected in hell.

I walk until night falls.

Right around when I get that tattoo on my elbow in Amsterdam, I decide I’m done with competitive swimming. The star within a star reflects that desire to leave the sport. Since childhood the night sky has represented escape and freedom. As an adolescent, I wasn’t just taking refuge in the starry heavens when I fled to the treehouse and stared up into them; I was also taking flight, losing myself amidst the glittering constellations.

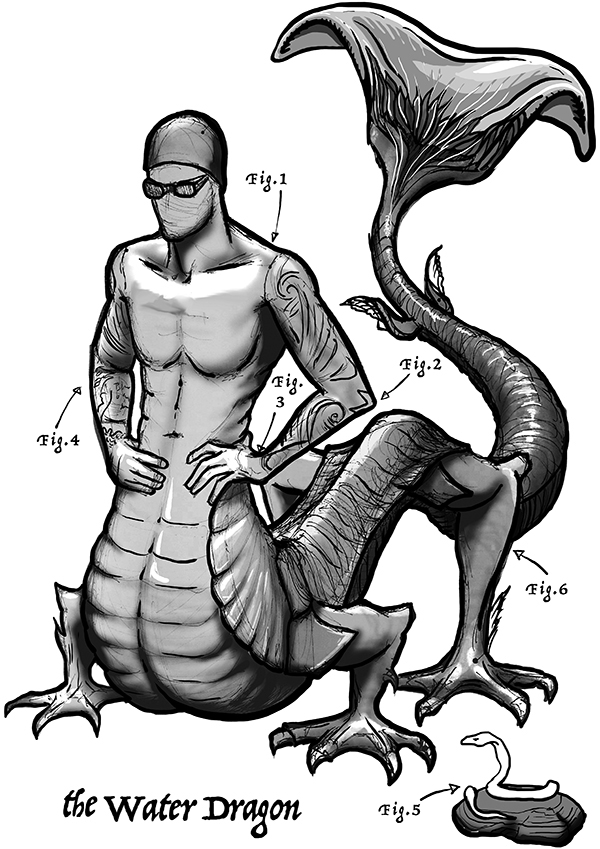

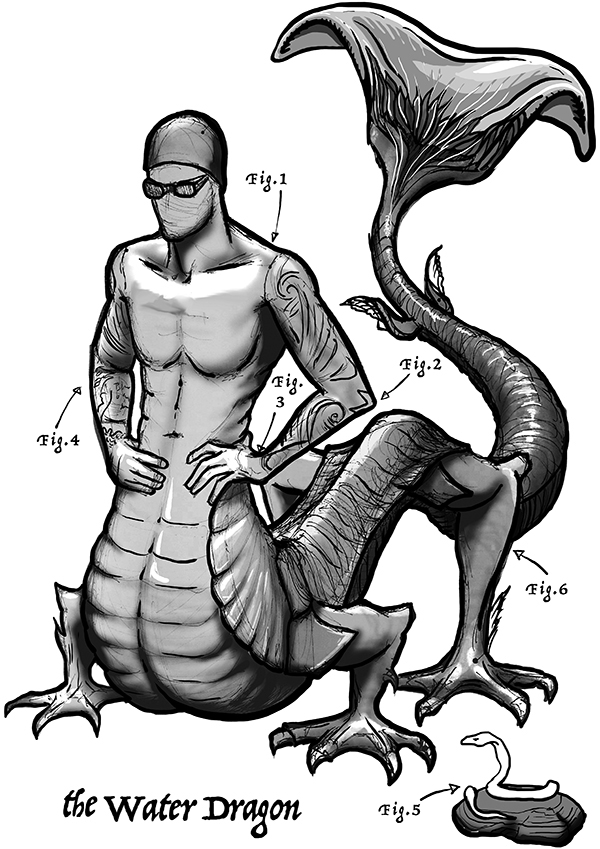

The star within a star isn’t my only tattoo connected to childhood. The tattoo sleeves I will soon have are rooted in a book from my adolescent reading. In Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series, the main character, Rand al’Thor, emerges from a gateway to the past, a profound and transformative experience, to discover that his arms have been branded with dragon tattoos. The literary passage, with its transfigurative symbolism, awed me, later inspiring me to get my own tattoo sleeves.

I’ve been at Cal for four years but still haven’t graduated because I lack direction, hopping from major to major, from computer science to cognitive science to biochemistry to philosophy, among other areas. No longer funded now that my four years of college eligibility are up, I leave school with a hodgepodge of credits that don’t apply to any single major. With the expiration of my eligibility, I’m able to sign professional contracts. I need the money so I sign with Speedo. One day I’m sitting there on the phone, baked out of my mind, as this agent yaps on the other line about the contract. He has the gift of gab. He bowls me over with words. And finally I can’t take it anymore. “Fine, fine,” I say, “I’ll just take the contract.” But four years after my Olympic gold, it’s a paltry sum. And I’ve signed to be a professional exactly when a career in swimming is the last thing I want.

I’ve been growing out my hair since the summer and by winter start twisting it up into dreadlocks. I also have a number of piercings, including ear plugs and eyebrow bars, although the bars mostly just annoy me because the spikes keep catching whenever I take off my shirt. I haven’t officially resigned from swimming, but psychologically I’m done; my piercings, dreadlocks, and tattoos attest to it.

When I return from Amsterdam in the fall of 2003 I start hanging out at Zebra Tattoos & Body Piercing on Telegraph Avenue. I get to know the tattoo artists and their various styles. After several months I ask one of the guys, Les, to start working on my tattoo sleeves. He begins with the left arm, where I have the double star, both because I’m left-handed and because left is the devil’s arm, which seems a fitting place to begin. My tattoos on that arm draw from the designs of the Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger, with the anatomy inversed so that the bones and sinews are on the outside. Greenery and water imagery surrounds and entwines the exoskeleton, as well as around the words Dream of Your Own Life on my forearm. It’s at once an image of torture and torment, in which the body seems destroyed, and an image of strength in the way it conforms to the body like a case of armor.

On the back of my left hand I get a maple leaf, tinged with reds and oranges, as if ready to fall from a tree. But others keep construing the maple as a marijuana leaf. I tire of that pretty quickly so I eventually put a bigger, bolder tattoo next to it of a rose. An ex-girlfriend’s sister, who never liked me, later sneers that it looks like a vagina. I’m bothered at first, but then again, most flowers look like vaginas, so rather than let other people’s opinions steer my tattooing any longer, I leave the rose as is. People will see what they want to see.

Considering how often I hang out at Zebra, I figure I may as well make some money at it. So I get a job there. At first I’m just in the front selling jewelry for piercings, which sucks. Later I’m a receptionist of sorts for the tattoo artists—making appointments, giving estimates, cleaning up the ink, changing needles, sweeping up, that sort of thing. The tattoo artists are good dudes, but they don’t let people mess with them. They tell me about one vagrant who came in, saying, “I’ve got a tattoo, wanna see it?” and then dropped his pants to his knees, with his cock just hanging there. The tattoo was just a little smiley face on his knee. And Reed said, “You motherfucker! Get out of here,” pointing at the door, but instead of heeding him the vagrant went ape shit and started kicking in all the glass jewelry display cases. That was a bad move. The entire staff took him out to Telegraph Avenue and proceeded to beat the senseless man into a new order of senselessness, then hog-tied him with duct tape to await the arrival of the police.

They’ve seen crazy shit working there. And they’re full of stories and tattoo tall tales. Like when that white trash kid from the back country of California came in spouting choice words of his dislike for “niggers” and “beaners.” No one took kindly to that, so when this racist hillbilly declared that he wanted BAD ASS WHITE BOY tattooed on his triceps, they obliged by overcharging him, asking for all the money up front, and carving the letters repeatedly. He whined about the pain the entire time as BAD ASS went onto his left triceps and WHITE BOY onto his right in Old English–inspired cursive letters. Exhausted, the guy looked at the finished product in the mirror and mumbled, “Fuck yeah,” before preparing to walk out. But when he put his T-shirt on, the sleeves covered the first word of each arm, so it just read ASS BOY as he walked out of the store, laughter following him.

I only work at Zebra a few months but they are influential ones. The tattoo artists have really lived. Reed has been shot, stabbed, and kidnapped, witnessed murders, and worked for Dustin Hoffman and other Hollywood elite. He’s lived around the world and toured the US in various rock bands, one of which, while he worked for Bob Dylan, was the Wallflowers. I grow closest to Reed, for I see him as my rock ’n’ roll mentor.

I’m still partying too much and unable to get my sleep schedule under control. Twice in one week I sleep through my alarm. The first time it’s a weekday and I show up an hour late. I’m warned. Then a few days later, Saturday of all days, I wake up at three p.m., and I was supposed to be at the shop at noon. When I finally arrive, Reed is just shaking his head, silently saying with his eyes, What the fuck, dude? He is punk rock and all, but when a man has to work he isn’t going to appreciate it when some irresponsible kid unexpectedly leaves him with a bunch of bullshit to do on the busiest day of the week. The owner tells me he likes me but can’t have me showing up late, so he fires me. But I keep hanging out at Zebra, and I’m still friends with the guys who, once the event has washed over, perhaps respect me more for getting fired.

I’m still learning about tattoos and getting inked. And just as nearly everyone in the shop has a chemical dependency problem, whether its uppers or downers, pills or powders, booze or weed, or all of the above, I continue to explore getting tattooed as I started: under the influence.

One time I get tattooed while stoned, which is the worst. All the physical and psychological pain is heightened by the same mechanism of cannabis that turns an ordinary light chuckle into a belly laugh, and the brief moment of personal introspection into a paranoid gyre. But perhaps that is more the effect of the permanent psychedelic stacking that is activated when I am high on marijuana. I’ve been tattooed on painkillers like Percocet, which I found didn’t numb the pain at all and instead made me really irritated. On psychedelics it’s intense in a different way, a full and unique experience, whether it is psilocybin mushrooms, LSD, or 2-CB. It’s easiest when I’m drunk since the intoxication of the alcohol and the conversation with the artist overpower the pain.

Before Les can complete my left arm, Olmy begins work on my right: a large Japanese-style tattoo of a phoenix, the mythical firebird of self-destruction and rebirth. It coils around the phrase Bleed in Your Own Light. I like the element of deviance in getting an Irezumi tattoo—it’s associated with the yakuza, the Japanese mafia. It is also a nod to Olmy, a guy raised in a hippie commune who in the nineties, after art school, began tattooing in Boston, a city where tattooing was still illegal. Half the time spent tattooing the phoenix takes place in San Francisco at the Hell’s Angels shop where Olmy also works. A piece of that shop also went into my skin.

Each tattoo is a time capsule. But what it was yesterday and what it is today and what it will be tomorrow aren’t the same thing. When I first got the tattoo of the leaf on my left hand, it was tied into the H.R. Gieger imagery and into a bad pun about songwriting (“the things I leave behind will come from my left hand”). But its meaning changed after I went down to my brother’s wedding in Hawaii. The sunset ceremony took place beneath a huge tropical tree on the Maui shore. As their kiss consummated the union, a strong wind blew in from the Pacific, raining leaves upon us all. My leaf tattoo is now bound up with that memory too, with, I’m sure, more to come.

Even upon completion a tattoo remains elusive, in flux, just like a memoir. Its meaning changes with time. Because the I of today is not the I of yesterday. And because you see that I with new eyes.

Usually elite swimmers end their swim careers after the Olympics, but Ervin did the opposite. In February 2004, a mere five months before Olympic Trials for the Athens Games, Ervin submitted paperwork to USA Swimming to withdraw his name from the roster of athletes subject to drug testing—a requirement for USA Swimming competitors. It was now official: Anthony Ervin had retired from swimming. His departure voided his Speedo deal and shocked many in the swimming world, especially those who wanted to believe he was just taking time off or in a temporary slump. But those who knew Anthony well weren’t surprised. This had been a long time coming.

The one person most gutted by his decision was his mother. To this day, Sherry Ervin sees his departure from swimming as a travesty. “I don’t think Anthony realized just what he sacrificed,” she says. “I don’t think he understands it even now.” She feels equally strongly about his tattoos: “I hate them. Hate ’em, hate ’em, hate ’em. He says to me, This arm is for you. No, it isn’t, I’m not owning that!” She sees no beauty in the tattoos, only an “ugly mish-mosh.”34 Body alterations, she points out, are a desecration of the body according to Judaism. For years after he got his tattoo sleeves she would buy him long-sleeved shirts for Christmas. And whenever he came home for the holidays she demanded he wear long sleeves. “I didn’t want to see the tattoos,” she says. “They actually hurt my eyes.” But Sherry does have two dark secrets regarding his tattoos. The first is that she supported him in getting the Olympic rings on his back, something she now agonizes over, as if her assent had enabled a future ink addiction. The second is that she concedes there’s an advantage to his tattoo sleeves. “To be honest,” she confesses to me in a low voice, “when I watch him on TV, that’s how I find him—by his arms.”

By rejecting swimming, Anthony was rebelling against developing his body as an instrument of locomotion. “After being forced to constantly abuse my body with labor, I wasn’t going to do that anymore,” Ervin says. “Years of neglect followed.” But while he neglected his body on matters of fitness and wellness, he didn’t entirely disregard it. He began viewing his body as clay to be manipulated through artistry, a physical objectification, but aesthetic, not sexual. “It was also a reclaiming of my body, with the tattoos and all. I was giving myself a new skin. I wanted to recreate myself.”

During this period he also got a new roommate, who coincidentally knew all about shedding skins. His name was Abraham, after the Old Testament prophet, although he went by Abe. A quiet roommate, Abe mostly kept to himself and was nocturnal like Anthony. He only ate about once a week, although when he did it was an impressive and unsettling sight, as his meals were carnivorous feasts that he preferred not just fresh but alive. An infant when Ervin first got him, the Brazilian rainbow boa initially subsisted on tiny squeaking pink mice whose eyes hadn’t even opened yet. Like a modern-day Medusa, Anthony once even smuggled Abe onto a flight to LA by hiding him in his dreadlocks. But it wasn’t long before Abe was a four-foot adolescent and Ervin was feeding him adult mice or baby rats. Brazilian rainbow boas are among the most attractive of snakes. They’re so named because of the microscopic ridges on their scales, which refract light into rainbows. They’re at their brightest after shedding. Dull and faded, the old skin sloughs off like gossamer netting, revealing a shimmering brilliance beneath.

A much-feared and maligned creature in most cultures, the serpent is nonetheless a mythological icon of recreation and transformation. Think of the Ouroboros, the serpent eating its own tail. Or the two serpents that entwine around the rod of the Caduceus, the transformative staff of Hermes, Greek messenger god and psychopomp who guides the souls of the dead. The staff has been co-opted by many in the medical field, who erroneously confuse it with the staff of the ancient healer Asclepius: his rod has only one snake and is thus less visually dramatic. While understandable from a marketing perspective, it’s an unfortunate mix-up, considering that Hermes, the Greek trickster god, was a protector of thieves, liars, and merchants, and the escort of the dead to their underworld resting place—not the most reassuring connotation for the infirm.

Ervin viewed Abe through a similar mythological lens, seeing him as his animal totem during those years. A symbol of the creative force of life sloughing off the past, the Brazilian rainbow boa was his slithering reminder that you can only grow by leaving part of yourself behind.

Rent, food, bills . . . I can only coast on savings for so long. So a few months after they fire me at Zebra, I get a sales gig at Guitar Center. I’m working in accessories, selling pedals, microphones, what have you. I hate it. It’s all about the upsell. They encourage us to profit off people’s passion. The more money you get out of others, the higher your commission. I’m there for four months but I can’t deal with its corporate structure anymore. So one day in November I say to hell with it and don’t go in. After a few days the manager calls me up.

“You haven’t been to work in a couple of days,” he says.

“That’s right,” I say.

“Are you okay?”

“Yeah. I’m just not going to come into work anymore.”

There’s a pause. It’s straight out of Office Space.

“Okay, well, take the rest of the week off and let’s talk after that.”

“Okay,” I say.

At the end of the week he calls me again.

“So, have you thought about it? Christmas is coming up. There’s good money to be made on commissions. Are you coming back to work?”

“No,” I say.

He doesn’t call me again. Guitar Center is desperate, but not that desperate. And neither am I.

The next day I’m out with Amir. We walk by STA Travel and see a sign for two-hundred-dollar roundtrip tickets to London over the Thanksgiving weekend. He just split up with his girlfriend and I just quit my job so—why the hell not?—we buy tickets on the spot. At a Goodwill I buy all my clothes for the trip, including a winter jacket for about five bucks.

We bum all over England. I’m subsisting on coffee, absinthe, and Ritalin. Food? Who needs that? In Cambridge I see a guy pissing off a bridge into the River Cam. So much for the refined British. At Cambridge University admissions I ask the receptionist if they accept transfers. She just glances at my dreads and looks away before curtly responding, “We do not accept transfers.” In Brighton I see the sun for the first time. It’s beautiful by the sea. We celebrate with a bottle of absinthe before stumbling onto a train back to London.

In Camden Town I get a tattoo on my leg of a graffiti-style skull wearing a crown, or maybe I should say a fool’s cap, to remember the trip. It’s a shitty tattoo, which I just whimsically chose off the wall. But it will remind me of this period of being foolish and free of all ties. And like the occasional pain in my shoulder, the skull will remind me of the times the Grip Reaper has hovered over me. A crowned skull. A fool’s tattoo.

Yet again, I’m broke. So when Mike Bottom presents me with a lucrative opportunity that involves running a few swim clinics along with Gary Hall Jr. for the Japan Swimming Federation, I take it. In December 2004, a few weeks after returning from London, I cut off my Sideshow Bob dreadlocks and fly to Japan. I go for the money and to hang out with Mike and Gary. But while in Japan, finding myself back in the role of an athlete, I’m energized by the enthusiasm I inspire in the Japanese swimmers. I feel an unexpected pull to compete again. I think about Gary, who took several years off after the Sydney Olympics and staged a return in time for Olympic Trials. He not only made the team but also won gold at the Athens Olympics, and he did so while I was peddling pedals at Guitar Center.

But if I swim again, I decide it has to be tied to a cause or charity. Others have given so much to me; I now want to give back. I’m not sure how exactly, but I know it has to involve water. As a toddler I was drawn to water, then fenced out of it. As an adolescent I was locked into it. As a young adult I fled from it. And now I’m considering a return to it, but with a different intention. Typhoon Tokage, the deadliest storm to strike Japan in a decade, just happened two months ago. Water’s destructive power has always resonated with me, so I contemplate a charity effort related to flooding. Tying a return to competition to a life-giving effort would be cathartic as well as altruistic. But I still don’t know what exactly I can do.

On the flight back to the US, Bottom invites me to join the Cal Berkeley swim team for winter training camp in Colorado Springs. After some thought, I take him up on it. I’m not committing that I’ll come out of retirement, but I know the physical conditioning will do me good.

I spend Christmas with my family, mulling privately over whether I should return to competition and, if I do, how to link it to flood relief.

And then, the day after Christmas, the Indian Ocean tsunami hits.

_________________

34. Unlike Anthony’s niece Sophia. Her father once found her coloring her arms with markers. “Look, Daddy, I’m like Uncle Tony,” she said, showing Jackie her arms. “I want to live with Uncle Tony.” Return to text