5.

Experiments

What in water did Bloom, waterlover, drawer of water, watercarrier returning to the range, admire?

—James Joyce, Ulysses

There was something very queer about the water, she thought . . .

—Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Anthony had no problem getting into college: he was one of the fastest sprinters in the country who also, thanks to AP and honors classes, had a 4.2 GPA. He wanted to attend Stanford, as he thought it would be the best place for him to pursue a degree in computer science or electrical engineering (which was mostly related to his love of video games). As much as he liked Berkeley and the coaches there, he planned to quit swimming after his first year, so Berkeley wasn’t his top choice. But though Anthony was admitted everywhere he applied, Mike Bottom was the only one who secured him a full ride. A full scholarship at a top-tier school was, for his mother, the clincher: he was going to Berkeley. The decision may well have sealed his future as a swimmer. At another school like Stanford, where the coach wouldn’t have accommodated him or supported him as much as Bottom did, Ervin would have probably, in his own words, “had a mediocre season and washed out,” or, more likely, been tossed off the team.

Upon accepting Berkeley’s offer, senioritis set in. Anthony’s grades slipped, his GPA for the first time dropping below 4.0. After passing one of his AP tests in the spring, he ditched the class in the final weeks to play StarCraft in the computer lab with his friends, which led to a brief suspension. Another teacher threatened to try to revoke his college scholarship because he kept sleeping in class. His high school coach remembers receiving calls from other teachers about Anthony’s lack of effort and, according to one teacher, insolence.

His senior year, Anthony had a car, as handy for skipping practice as for getting to it. Recognizing her son’s propensity for evasion, Sherry would drive by the pool on her way to work to make sure his car was parked there. It always was. What she didn’t know was that sometimes he’d be sprawled out in the backseat, asleep. But even slacking off, he still got best times in the 50 and 100. By the end of his senior year, he was the fastest high school freestyle sprinter in the country.

After spending the summer in a suit and tie selling sportswear at Robinsons-May to yachting types, Anthony showed up at Berkeley as out of shape as he’d ever been. It was his first extended period away from home without supervision. During Welcome Week he drank continuously, smoked marijuana for the first time, and, more momentously, lost his virginity.

I can’t believe I just met A the other day and now we’re lying here in my bed. Naked in my bed. The light from my alarm clock makes her hair shine blue. She’s running her fingertips along my head, playing with my hair on the sides where it’s been buzzed short. I remember at that party how she was looking at me from across the room, tapping her blue flats to the music. And then how she glanced away when I made eye contact, hiding behind her black hair. She’s not glancing away now.

“Have you done this before?” she asks.

I’m about to make a dumb joke, like, What, talked to a girl? But she interrupts me.

“Sex, I mean.”

Is she hoping I have or haven’t? I can’t read her. If I say no, I’ll look pathetic. Everyone has had sex by now.

“Sure, I’ve done it.”

“Oh,” she says, and looks down. “I haven’t.”

It’s too late now to tell her the truth. Now I have to keep up the lie.

She smiles, a little forced. “I still want to do it.”

“That’s cool,” I say. “We should. It’s no big deal. It’ll be fun.” Fun? I actually like this girl and here I am sounding like a frat guy who just wants to get laid.

But she doesn’t seem to mind. Or not enough for us not to do it.

A few nights later we come back to my room, but this time my roommate is there. He looks asleep. A and I get in bed and start kissing. After a while, he rolls over in his bed and adjusts his pillow.

“We can’t do it here,” she whispers. “He’ll hear us.”

“He won’t. We’ll be quiet.”

And that’s two more lies to pile onto my first one.

Even if the relationship lacked elegance in its origins, it was more than a Welcome Week fling: they dated exclusively for the rest of the year. They would often stay up late, fooling around and laughing in bed, much to the chagrin of Ervin’s roommate, a quiet and reserved engineering student, who would be trying to sleep a few feet away. And when A wasn’t over, Anthony would be up late playing video games. He’d set three alarms for morning practice, often sleeping through all of them. “I’d steal my roommate’s protein shakes too,” he recalls, shaking his head. “I was the worst roommate ever.” He regularly stole food from the dining court that first year. He’d order a sandwich or burrito in one part of the food court, and then stroll past the cashiers by the exit, pretending he’d already paid.

His teammates didn’t think too highly of him initially. Even on the recruiting trip, he’d left the impression of being a slightly cocky kid only interested in video games. Still in the virginal wine-cooler phase of his drinking career, he bowed out of all the beery proceedings at freshmen hazing: no Century Club (a shot of beer every minute for one hundred minutes) or Beer Mile (run a lap on the track, pound a beer, repeat three times). The only event he participated in was the one where he had to wear women’s underwear for the day: he borrowed a G-string from a classmate (“It’s like having a wedgie all the time, I don’t know how girls do it.”). Even at a liberal bastion like Berkeley, the fact that he went for the thong-a-thon and opted out of the beer guzzling probably only led to more eyebrow-raising over the new kid from Valencia.

At the first team meeting he didn’t show up. The coach had to send scouts to track him down. Without his mother there to drag him out of bed, he rarely made morning practice. His former teammate Richard Hall was one of the guys who, along with Anthony, was suspended at one point for not making enough practices. Most of those swimmers had around 70 percent attendance. Richard remembers Anthony’s because it set a new record low: 37 percent. Despite the full athletic scholarship, he was making roughly one out of three practices. This didn’t sit well with his teammates.

Four-time Polish Olympian Bartosz Kizierowski, Berkeley’s upperclassman lodestar swimmer who was known for his dynamism and training intensity, remembers Ervin as “one of the laziest people I ever trained with.” At a December team trip to Vegas, they were doing sprint sets from a dive, which involved standing around on deck in the cold air. Bartosz, or Bart as he’s known, remembers standing poolside, shivering, waiting for Anthony: “Then he runs out of the shower all nice and cozy with red skin from a hot shower. I’m just freezing there. And we dive in, for a 50 or a 100, and I get my ass kicked. So you can imagine my frustration.” Another time, during the first round of an acidosis set meant to train athletes in pain tolerance, Ervin curled up in the pool gutter, groaning, until he vomited. He lay there for a while in a fetal position before slinking off to the showers.

But Bart’s initial disdain began to change when he realized that, despite often bailing on training, Anthony swam in a unique way. It was Coach Bottom who insisted that he closely watch Anthony’s stroke. Soon Bart began to realize that this kid was doing something completely different. “It was all very technical and connected,” Bart recalls. “Eventually we all tried to swim more like Tony.”

Ervin’s idiosyncrasy paradoxically was not so unexpected in the swimming world. Eccentrics are found in every sport, but swimming seems to attract, or create, them in abundance. Maybe it’s a product of the medium—complex, dynamic, unpredictable—or all that chlorine seeping into one’s pores, or the countless hours spent suspended in strenuous exertion, staring in virtual isolation at the pool bottom, lap after lap, like a suburban variation on Chinese water torture. Whatever the reason, swimming has an abundance of characters among both competitors and coaches, and not just among its plebeian ranks: it’s wacky all the way up to the elite crème. In fact, it can even be more idiosyncratic up top since iconoclasm and outside-of-the-box thinking is often what it takes to stand out from the overwashed masses. On the other hand, the regimentation of workouts also generates a culture of intolerance in the swimming world toward those who disrupt that structure. Free spirits are tolerated, but only so long as they’re disciplined and compliant free spirits.

Even traditionalist and by-the-book coaches can sound occult on deck in their use of esoteric terms like threshold speed, VO2 max, negative splitting, and let’s not forget lactate profiles, which to the uninitiated might sound like a pregnancy fetish or something out of Mother, Baby & Child magazine. Of course, there are those coaches and trainers who expand the lingo: there’s USC’s swim coach Dave Salo,13 who published the book SprintSalo: A Cerebral Approach to Training for Peak Swimming Performance, which includes a “SaloSlang Glossary” with drills like PeekSwim, where one swims with closed eyes, taking occasional “peeks” for orientation (this comes with advice to “tell those around you what you are doing and have them watch and protect you”); there’s Milton Nelms whom the Australian press dubbed the “horse whisperer of swimming,” also the creator behind the “Nelmsing Code,” which according to a SwimNews article is a “book of incantation from the holistic school of Brainswimming”; and then there’s Mike Bottom.

Bottom is known as one of the world’s finest sprint coaches—in the 2004 Athens Olympics, for example, two out of the three 50 free medalists were swimmers he’d coached—with an uncanny motivational ability to enter the minds of his athletes and inspire them to believe they can do things they didn’t dare consider before. One way he does this is by first articulating their fears. For example, after a narrow relay defeat at the 2012 NCAA Championships, he reviewed the race with his swimmers: “What happens in the last lap or in the third turn when the field is right there and the splash is big and there’s maybe one guy that’s way ahead, is you get fear in your heart. You get fear in your heart . . . ” And while saying this he’s leaning in and stabbing at his own heart with his fingertips, and you can tell by the way the guys are gnawing at their fingernails and staring off with haunted looks that it’s sinking in, that he’s found a way into their private emotional space, that they’re listening. It’s not that these athletes have never before heard a you-can-do-great-things voice urging them from within: it’s just that, as with most people, that inner voice gets sidelined due to fear or insecurity or laziness or sheer distraction. Bottom excels at getting athletes to find that voice again. Swim journalists call him a “mind guru” and “ultimate mind coach,” and no doubt his master’s degree in counseling helps with that. But it’s more than education. There’s something about his manner of speaking—his deep, measured voice, his way of finishing sentences with “right?” as if gently luring you into affirmation, his pensive pauses, his penetrating gaze through thick black-rimmed glasses that seems to be figuring out something about you at the same time that he’s telling you something—something that gives a charge to his words, as if they’re more than just accurate, they’re somehow essential. You get the sense that, had his life taken a different turn, he could have easily been a hypnotist—not the stage entertainer sort, but one who uses hypnosis for a therapeutic and transformational reprogramming of the mind.

It didn’t take long for Bottom to see that if he pushed Ervin too hard, he’d lose him. Anthony required persuasion: “It was just a matter of talking to him every day, seeing where he was, giving him reasons to be there.” Mike Bottom understood the fickle intricacies of Ervin’s character and knew that if too many demands were made of him, he’d drop out. So he adapted, appealing instead to Ervin’s desire to learn: if Anthony arrived too late to workout, as he often did, Bottom would usher him into his office to watch race videos of swimming greats instead of sending him off in anger.

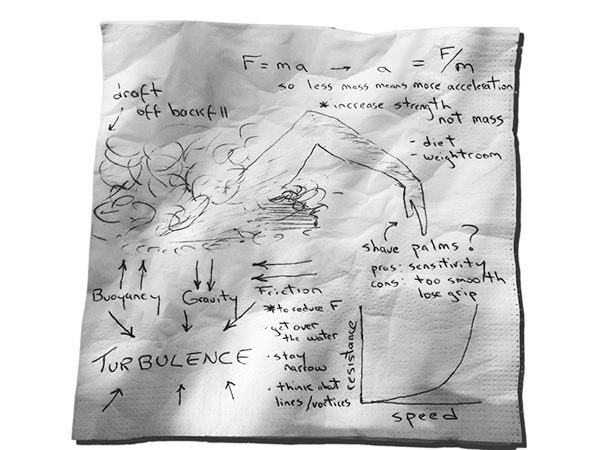

Before Berkeley, Ervin’s swim training had been fairly conventional: the usual back-and-forth slog focusing on yards and intervals that is the de facto foundation of precollegiate competitive swimmers. But with Bottom he was discussing technique, breaking down and analyzing his stroke, and exploring ways of “connecting” with and “catching” the water,14 concepts Anthony had never even considered or heard of before. It was all new and stimulating and kept him engaged. It allowed him to apply his understanding of calculus to swimming, analyzing it as a problem set with lines and coordinates, limits and changing variables. Before, swimming was about yards, effort, and times. But now it was research, study, and exploration.

* * *

Even missing as many practices as he did, Ervin was learning more about swimming than ever before. When he did make practice, he was methodical, experimenting with different ways of catching water, reducing turbulence, increasing efficiency. Bottom remembers one of Ervin’s eureka moments, when he abruptly stopped during a set to tell him he’d found a new way of connecting with the water. “I don’t want to call it joy,” Bottom recalls, “but it was excitement. Like a hunter that just shot the deer.”

Berkeley was ideal for Ervin: competitive but fun, a place where you could miss practices and screw up on occasion so long as you kept the course. Only when it came to taking supplements did Berkeley run a tight ship. Most people assume that cheating in athletics is a clear-cut act (the Hollywood trope of a baggy-eyed trainer grimly injecting steroids into his athlete behind closed doors comes to mind), but often athletes get busted simply from taking rogue supplements that claim to be legit but aren’t. To prevent that, Bottom obtained all supplements from a single, trusted supplier. But when it came to training approaches, Bottom experimented with the gamut of them, no matter how outlandish.

“Mike used to come up with so much weird stuff,” Bart Kizierowski recalls. “I remember walking on the bottom of the pool [carrying] twenty-kilo iron blocks. Just walking fifty meters, no-breath work.” And it got weirder. One of the volunteer coaches, Karl Mohr, had been researching alternative wellness and recovery practices and would forward the articles to the head coaches. Bottom’s philosophy was, “As long as it’s legal and can’t hurt you, we may as well try it.” Co–head coach Nort Thornton, Cal Swimming’s venerated veteran and technical wizard, was also open to it. Few established coaches would have been.

So Mohr started bringing stuff in, stuff you’d expect to find at a Berkeley Holism conference but not on deck at a top college sports team. Stuff like liquid oxygen drops and colloidal silver water and altered “clustered water.” Stuff like a conductive electric glass orb in front of which the swimmers would sit for five minutes on an insulated chair with their feet on a grounded pad and palms on the orb as its electric tendrils danced about, in effect charging themselves with electric currents to stimulate recovery. They once set it up at one of the meets, which must have been quite a sight for the opposing team. Another time they had twelve guys hold hands, with the last guy standing on a grounded pad, while the first one dipped his finger into a canister of electrically charged water, causing a jolting electrical current to course through all twelve of them—sort of like a more intricate and communal version of the farmhand stunt of pissing on an electric fence. But probably the most Out There thing they did, albeit the simplest, was writing positive words on their water bottles—words like Love, Team, Attraction—based on the premise that water organizes itself around feelings. It’s easy to shake your head and snort at that sort of thing and you wouldn’t be the first. In his Restoration comedy The Virtuoso, the seventeenth-century writer Thomas Shadwell satirized the sports science of his day in describing a young man’s effort to learn the breaststroke: He has a frog in a bowl of water, tied with a packthread by the loins, which packthread Sir Nicholas holds in his teeth, lying upon his belly on a table; as the frog strikes, he strikes, and his swimming master stands by to tell him whether he does well or ill. But even something as spectacularly eccentric as writing positive words on water bottles reflects the spirit of unabashed exploration and tolerance that pervaded the team, the conviction that one should try things, no matter how bizarre or kooky, because it’s the only way to find out what sticks.

It was in this experimental culture that Ervin found himself that first year. It was also the first year that was truly his own. Untethered, no longer under his mother’s panopticon, he was alone and ungoverned, free to do what he wanted, as he wanted.

So he experimented.

HYPOTHESIS 1.0

Situating a digital alarm clock at least two meters from subject’s bed will, upon initiation of electronic sound, compel the newly and begrudgingly awakened subject to move from a sheltered recumbent state to an exposed ambulatory bipedal one in order to disable, either indefinitely or for an eight-minute increment, the plangent object of his discontent, thereby enabling him to realize his goal of standing poolside, seminaked in the crisp dawn air, ready for wet vigorous activity, at 0600 hours.

CONCLUSION

Negative. Subject awakens, confused, at four minutes before 1200 hours.

HYPOTHESIS 1.1

Identical to previous experiment except for a changed variable. The rectangular digital alarm clock is replaced by a round manual wind-up alarm clock, advertised in stores as “retro” to increase profit margin, with an inverted brass-colored hemispheric bell on both the left and right side of its apex, designed and duplicated for maximum acoustic resonance and reverberation, all of which when viewed from a haze of somnolent languor sometimes takes on the visage of the anthropomorphic rodent mascot of the Walt Disney Company.

CONCLUSION

Again, negative. Subject’s eyes don’t open until 1121 hours. They close at 1122 hours, then open again at 1123 hours. At 1152 hours subject sits up. At 1153 hours subject’s roommate asks if subject could abstain from using wind-up alarm bells in the future, his request both preceded and followed by the word please, its second iteration articulated with greater emphasis. Subject responds by pressing the distal phalanxes of his right hand’s thumb and forefinger against his temples and emitting a groan.

HYPOTHESIS 2.0

Inviting subject’s teammates to watch favorite movie, Army of Darkness, may prove beneficial for building consensual nonsexual relationships, thereby having the effect for the subject of relieving, in ascending order of magnitude of distress induced, his sense of disconnectedness, loneliness, friendlessness, purposelessness, and for the teammates of mitigating, again in ascending potency as reflecting the subject’s anxieties, their sense of misgiving, annoyance, resentment, rejection.

CONCLUSION

Find new favorite movie.

HYPOTHESIS 3.0

Since a dropped elbow results in an ineffective pull, swimming with a locked elbow and straight arm prevents dropping of the elbow.

CONCLUSION

Affirmative but inadvisable. Subject mashes the water, dispersing it instead of holding it. Furthermore, the potential for shoulder injury is high. Appreciating that deltoid mass and density may be the limiting factor, further assessment and analysis on bulkier, hulkier swimmers is recommended.

HYPOTHESIS 3.1

If a collapsed elbow pull is the problem, the focus should not be on the pull but on the entry and catch. By arriving at the pull in a different way, the problem is preempted.

CONCLUSION

Affirmative.

HYPOTHESIS 4.0

Smoking cannabis confers beneficial attributes for aquatic training and proprioceptive feel for water. (The subject’s motive for undertaking this experiment stems from an unsubstantiated and potentially defamatory rumor that celebrated, decorated, and chlorinated former University of California, Berkeley natator Matthew Nicholas Biondi occasionally refined his freestyle technique after inhaling cannabinoid because he found that it heightened sensation, perception, and technical proficiency.)

CONCLUSION

Negative for training; inconclusive for feel. While subject reported a sense of being “more tuned into his body,” he resisted all physical action with two exceptions: first, blowing concentric bubble rings from the pool bottom, which he performed by pinching his nostrils from a supine position and expelling brief bursts of air upward; and second, roiling the water with air by pushing and pulling his open palms through the water, and then floating facedown and immobile in spread-eagle position over the cavitation zone as the myriad tiny, newly generated air bubbles rose up and expired upon his torso and appendages in a reportedly pleasurable sensation of kismesis. The tetrahydrocannabinol isomer appeared to cause a significant debilitation and enervation of the subject’s will, as he found himself stationary on the wall for long periods of time, too distracted and, to use his colloquialism, “stoned” to undertake the rigors of a training regime. He did, however, report enjoyment.

PROPOSED EXPERIMENT

In the days prior to a big taper meet, the subject weans himself off clonidine, a Tourette’s medication.

ANTICIPATED OUTCOMES

1. Tourette’s symptoms will increase and nervous system will go into overdrive, thereby aiding his race performance.

2. Tourette’s symptoms will increase and nervous system will go into overdrive, thereby hindering his race performance.

Experiment postponed for National Collegiate Championships in March of 2000.

The experimentation kept Ervin interested in swimming, but he was falling behind in school. His days of 4.0+ GPAs were over. Toward the end of the semester, his friend asked to see the syllabus for one of his classes. “Syllabus,” he said, “what’s that?” He didn’t buy the course books until two weeks before the final. He failed a class his second semester, though he was able to stay afloat thanks to his Get Out of Jail Free AP credits from high school. The only A he got, also during his second semester, was in the biology class “Brain, Mind, and Behavior.”

The intersection between mind and substance became Ervin’s main interest that first year. His experience with marijuana during Welcome Week left him feeling like everything he’d been told about recreational drugs was a lie, or at best a naïve and incomplete demonization that lumped all substances—from anodyne cannabis to ruinous meth—under the umbrella of “bad drugs.” It was like pulling the curtain on Oz. He wanted to learn more from a reliable source. How were these various substances different? How did they interact with the brain? What were the consequences? Risks? He became a dedicated reader of Erowid, an online library that offers expansive and comprehensive information about legal and illegal psychoactive plants and substances, as well as about techniques for inducing altered states of consciousness like meditation, fasting, prayer, deep breathing, and lucid dreaming. By his estimation, for every hour he spent studying for class, he spent three hours reading up on the Erowid website about ayahuasca, peyote, DMT, LSD, salvia, psilocybin, and so on. It wasn’t the party drugs that interested him, nor the uppers or downers, nor the street junk, but rather the hallucinogens, which offered a portal to a new dimension of experience, or as he put it, another way of “trying to get to Xanth.” At the time, however, he was purely a researcher, not a “psychonaut.” It was consistent with his desire to understand, to be conscious and self-aware about his behavior and actions, in the same way he sought in the pool to understand the subtle details of his body’s interaction with the water.

Dealing with Tourette’s had given Ervin a foundation in trying to understand the mind and its biochemistry, so exploring the interplay between drugs and mind was a natural next step for him. After years of being at the mercy of his Tourette’s, he found something empowering in the knowledge that the mind could be shaped, altered, and molded. He never ingested anything without researching it extensively beforehand and understanding the risks and adverse effects. Though the plants and substances were consciousness-altering, not performance-enhancing, he was intrigued over any insights they might offer regarding his feel for the water.

During this experimental period Ervin came to a conviction, mostly based on Erowid readings and occasional experiences with marijuana, that consciousness and even “reality” were far more malleable and unstable than he’d assumed. The world wasn’t what he thought it was. As a child he’d sought escape from reality through fantasy books; and there had always been an unambiguous delineation between reality and fantasy. But now that line was blurring. (See Apendix A)

_________________

13 Not to be confused with the linguist and “Tolkien language scholar” Dave Salo, who can be found on YouTube reciting the Ring Verse in his Elvish-language Quenya translation. Return to text

14. “Catch” is the moment when the hand enters the water and applies pressure. It’s basically the grip you get on the water. To nonswimmers it may sound esoteric, as it was for swimmers back in the nineties, but it’s now as universal and frequently invoked as “kick” or “pull.” Return to text