5

Memory Management

All objects used in computations must be placed somewhere in computer memory. We touched on memory management when discussing variables, as well as arrays and pointers (Section 3.1). The two most important concepts related to objects and memory are these:

- Object visibility (scope) – The rules telling which parts of the code an object can be accessed from. The scope of an object that is not a member of a class starts at a point of its declaration.

- Object lifetime – How long an object is “alive†in memory, and which components are responsible for its creation and deletion.

Knowing these is essential for proper code organization. However, although object visibility is an easy concept, understanding object lifetime and responsibility for an object’s creation and deletion is much more demanding. Violating these guidelines can result in serious programming errors, such as accessing deleted objects, and in memory leaks . These problems, as well as methods to remedy them, are discussed in this chapter.

5.1 Types of Data Storage

C++ programs use various data structures to store different types of objects (variables and constants); see Appendix A.3 Also, depending on the storage type, there are different rules for object creation and deletion. These are discussed in Table 5.1.

5.2 Dynamic Memory Allocation – How to Avoid Memory Leaks

As alluded to previously, the C++ language has two underground data structures for storing objects: the stack, associated with each block of a function or a statement; and the heap, used for dynamic memory allocation . The stack is created when program execution steps into a function or statement and is automatically destroyed, along with all of its contents, after execution steps out of it. On the other hand, objects allocated on the heap with the new operator (GROUP 4, Table 3.15) persist until the corresponding delete is encountered. If this delete is omitted, memory is usually allocated until the end of the process or even until the next computer reboot. This situation is a serious software error called a memory leak that should be always avoided. It is dangerous Âespecially in systems like web servers that repeatedly call a faulty software component. The separation of new and delete is a feature of the C++ language and allows for deterministic control over memory allocation and deallocation events. Some languages have built-in automatic removal of memory that is allocated for objects that are no longer referenced by other objects; this is called a garbage collector mechanism. However, it is also not free from problems and can add significant computational overhead during program execution.

Table 5.1 Rules for creating and deleting objects.

| Object allocation and/or access type | Lifetime and accessibility | Memory area | Example |

| Automatic (local) | Automatic objects (variables) are created within functions. Unless suitable constructors are provided, they are not automatically initialized, so explicit initialization is necessary. They are automatically killed when control leaves the function where a given automatic variable was defined. Each new block {} defines a separate scope for its local variable s. These exist only when control is in this block or statement . |

The stack – a local memory data structure associated with a function or a block {}.The stack is automatically created when code execution enters the block, and it is automatically deleted on its exit. However, local stacks allow for relatively small objects, so for large allocations (e.g. matrices), the heap should be used. |

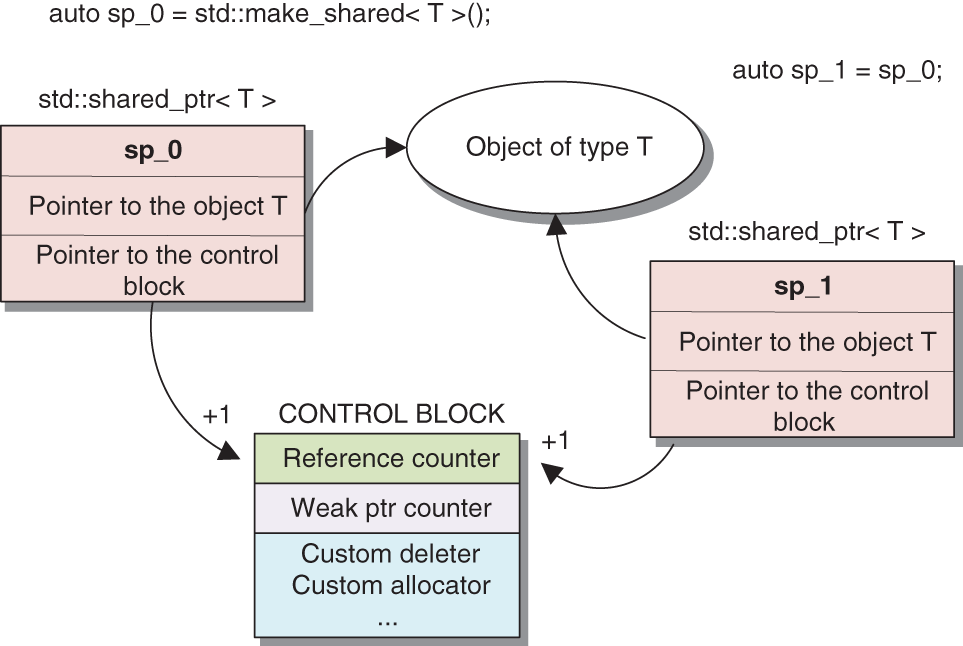

The following code snippet defines three objects named var. One has global scope, and the other two are automatic variables defined in the function and its inner block, respectively.

|

| Global | Global variables are created in the special memory area reserved for the program. They are initialized by special code before the main function is called. They are destroyed automatically after exiting from main. They can be accessed from any place in the translation unit (a compiled file with all of its includes), and in other translation units after being introduced with the extern directive . |

Global memory area | The first var, defined on line [2], has global scope . It is placed in a special global memory region created when a program starts (the code is generated by the compiler; see Appendix A.3). It can be accessed in the var_test_fun function and in all other functions of the program.The second var, defined on line [7], is a local variable . It is placed on a local stack associated with the var_test_fun function. Then a third var is created on line [12]. It is created within an inner block, which also has a second associated local stack. This third var hides access to the second var because it has the same name. There is no way to access the second var in the inner block. When the block is ended on line [14], the second local stack is destroyed, along with all the local variables from that block.On line [16], a first local var is initialized with the global var. To access the global var, we use the global scope operator :: (GROUP 1, Table 3.15).The function ends on line [19], which entails deleting the second local stack, containing the second var. |

| Static | Static objects (variables, constants) reside in special memory associated with the C/C++ program. They are automatically initialized to their default (zero) values, after the program starts and before entering the main function, and they are automatically destroyed when the program ends.

However, unlike global variables, they can be defined within functions. In this case, a static variable is alive between consecutive calls to that function and is accessible only in the function. |

Static memory area | In this example, we show how to use a static variable, defined in a function, to control the number of executions of a block of code in that function:

The function do_action:times takes two parameters. The first, N, is used to initialize the inner static variable n_counter, defined on line [9]. The second, to_display, is simply passed to be streamed out to the screen. n_counter has three interesting aspects: (i) it will be initialized at the first (and only the first) execution of the do_action_N_times function; (ii) because n_counter is a static object, it will survive calls to do_action_N_times. N and to_display are automatic and will be destroyed whenever they encounter line [18], whereas n_counter will be untouched; (iii) if do_action_N_times is called from multiple threads, then each call will have different variables N and to_display, since these are private to the function, but only one n_counter throughout all threads, since it is shared (and access should be synchronized in such a case; see Chapter 8).

At each function call,

In a separate translation unit, say a file named file_b.cpp, using a global object

Using static objects in one translation unit makes other translation units free to use their own objects named y. The static specifier can be assigned to the functions and to the class members (see Table 4.3).There is also a construction extern "C" { } that lets us call C-type functions from within C++ code (see Appendix A.2.7). |

| Heap-allocated | The heap is a separate and usually large memory region used for object allocations performed with the new operator (GROUP 4, Table 3.15), or the malloc function in C (Appendix A.2.6). Such an allocation is not automatically freed and requires an explicit call to the delete operator (or the free function in C).In order to avoid memory leaks, using smart pointers is recommended when working with heap allocations (Section 5.2). |

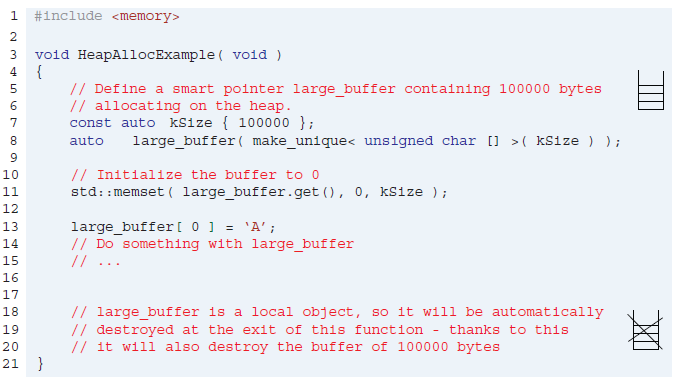

The heap – usually a large memory area reserved by the operating system on behalf of the running program. | In the following example, a large memory area of 100 000 bytes is allocated on the heap . However, to avoid using new and delete explicitly – which can be easily mismatched, leading to memory leaks – we use the make_unique function. It returns the unique_ptr object (a smart pointer ), which on line [8] is assigned to large_buffer. For simplicity, we declared the large_buffer declared with the auto keyword .

The memory block can be initialized to 0, as on line [11], and accessed as an ordinary large array, as on line [13]. The interesting action happens when we exit the HeapAllocExample function on line [21]. Since large_buffer is a local object, it is automatically destroyed on exit from this function. In its destructor, it calls delete [] to free the entire buffer of heap -allocated memory. As a result, the memory-disposal process is automated, which greatly helps avoid memory leaks . Smart pointers are discussed further in upcoming sections. |

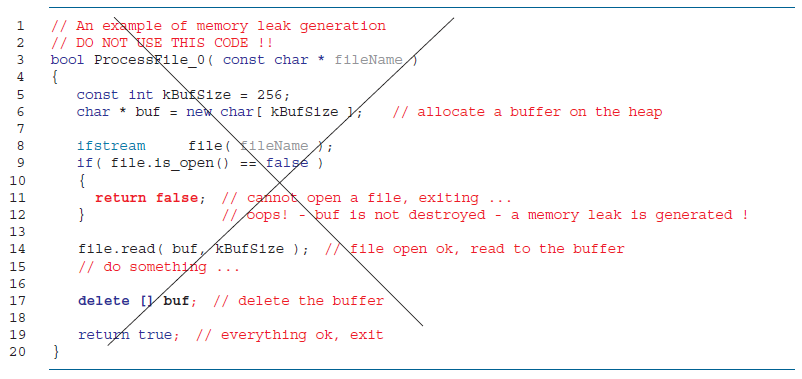

This problem is quite common, so let’s take a look at how it can arise in practice:

On line [6], a buffer of 1024 bytes is allocated on the heap . No problem – it can be used as a buffer to read bytes from a successfully opened file. Then, it can be deleted at the end of the function, as indeed happens on line [17]. However, in practice, a file with that name may not exist, so there is another path of execution that terminates the function if the file cannot be opened. Thus, on line [11], the function returns false to indicate an error. But we forgot to free memory that is allocated on line [6] and pointed to by buf. And because buf is a local variable, it will be lost after the function exits. Such situations frequently arise in practice, especially in large functions with many internal calls and alternative execution paths.

So, how can we avoid pitfalls like this? Without changing the function much, we can use a couple of C++ features. The first one is to use an object that is allocated as a local and automatic variable and that will safely allocate and deallocate memory for us. This is the vector object (Section 3.2). A version of the file-reading function looks like this:

This time, on line [5], a local automatic object buf of type std::vector< char > is created. In its constructor, it is allocated 256 bytes on the heap . Its destructor deallocates that buffer. But since it is an automatic local variable of the ProcessFile_1 function, no matter what execution path is followed, it will be automatically destroyed: its destructor will be called and the memory deallocated. That’s the point – using an automatic local variable and harnessing the automatic object-disposal mechanism! There is also no delete.

To use this version of the function, two minor changes were necessary. First, to use a vector, on line [13], we had to change the access to the memory buffer – we use the address of its first element. Second, we changed the input parameter from const char * to const string &. Unlike calling by a pointer, calling by a constant reference is safe since a reference must point to an object – in this case, a file name.

The second option to avoid the risk of generating memory leaks is to use a smart pointer . Its operation will be explained later, so first, let’s take a look at the third version of the function:

This time, on line [5], a buf object is created via a call to the make_unique helper function. Hence, its type is unique_ptr< char [] >, which we avoid writing explicitly thanks to the auto keyword . unique_ptr is an object that behaves like a pointer to an array . But once again, since it is a local automatic object in the ProcessFile_2 function, no matter what the execution path is, unique_ptr will be automatically destroyed. This entails a call to the destructor of the unique_ptr object and deallocation of the buffer to which it holds a pointer. To access the pointer to the memory buffer, we had to change line [14] and call the buf.get() function. In other regards, unique_ptr behaves like an ordinary pointer.

Summarizing, when heap memory allocation is required, then the simplest and safest method is to use an SL container, such as the vector. But remember that in addition to the memory allocation it is also zero initialized, as well as the vector object itself is created. If this is not desired (e.g. if there are thousands of such objects), then unique_ptr is a lighter-weight option.

Allocating blocks of memory through SL containers or smart pointers is the only way to avoid memory leaks, especially if the code throws an exception. This is another point advocating for refactoring the old code that calls new directly.

5.2.1 Introduction to Smart Pointers and Resource Management

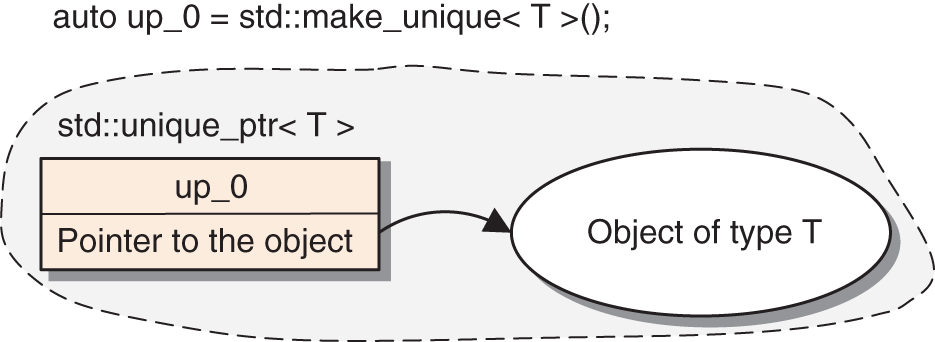

As we mentioned earlier, the main idea behind the smart pointers is to harness the mechanism of automatic disposal of the automatic objects to the deallocation of the memory blocks from the heap . Let’s take a look at what mechanism is actually used in smart pointers. For this purpose a template class a_p of “advanced pointers†may look like follows:

In the a_p constructor on line [10], a pointer to an object of type T is passed and stored in local data pointer fPtr. When a_p is destroyed, its destructor on line [13] is called, which in turn destroys the object pointed to by fPtr. To be useful in the role of a pointer, a_p must overload the dereferencing operator (line [18]) and define a few more member functions that we omit here. The following function shows a_p guarding an object of type double, allocated on the heap :

An object apd of type a_p< double > is created on line [5] and initialized with a pointer returned by new double. Then, apd is used on lines [8–10] as if it were an ordinary pointer to double. However, since apd is a local variable, after reaching the end of the function on line [14] or at any other exit point, it is automatically deleted (the code is generated by the compiler). This, in turn, invokes the apd destructor, which simply destroys the double object from the heap . This is just a glimpse – in reality, a smart pointer needs to define a few more functions. Fortunately, such classes have been written for us – they are presented in the next section.

An in-depth treatment of smart pointers and contexts for using them can be found in the excellent book by Scott Meyers: Meyers 2014. Also, the following Internet websites provide the newest information with examples: Stack Overflow 2020; Cppreference.com 2019a, b.

5.2.1.1 RAII and Stack Unwinding

The aforementioned mechanism belongs to the principal paradigm of C++: resource acquisition is initialization (RAII), discussed at the beginning of Chapter 4. In the previous example, we saw RAII in operation. It is strictly connected to the concept of an automatic call to a constructor when an object is created, and an automatic call to the destructor when that object is deleted. The object’s constructor can initialize whatever resources the object needs, and the destructor can release them. Both mechanisms make RAII attractive and functional – thanks to the automation of the constructor/destructor calls, the processes of resource allocation/deallocation are also automated.

Note that in addition to memory, other resources such as opening/closing files, locking/unlocking parallel synchronization objects, etc. need to be managed the same way. Not surprisingly, in these cases the RAII principle is recommended (Stroustrup

2013). For example, in Table 3.9, the outFile object of the std::ofstream type is created. Implicitly, its constructor tries to open the file Log.txt. This requires few calls to system functions, which are handled by the std::ofstream class. If they succeed, as verified with the outFile.is_open() condition, we can safely write to that file. But what happens next? Do we explicitly close the Log.txt file so other components can use it? No: we do not have to do this explicitly, since when outFile goes out of the scope, its destructor is called automatically and, in turn, safely closes the file for us. No matter what would happen if, for example, an exception was thrown, if outFile is entirely constructed (i.e. its constructor finishes its job), it is guaranteed that the outFile destructor will also finish its job (i.e. free the resources). A similar constructor is used in many other examples in this book; For instance, the CreateCurExchanger function in Listing 3.36 creates the inFile object, which opens an initialization file; when inFile is automatically deleted at the end of this function, that file is also closed. The acquisition of a resource (such as a file, in this case) is achieved by the initialization of the local object embodying that resource. This also guarantees that a resource does not outlive its embodying object. In addition, the RAII mechanism ensures that resources are released in the reverse order of their acquisition, which is a desirable feature.

Closely related to RAII is the exception-handling mechanism. An exception object of any type can be thrown with the throw operator (GROUP 15, Table 3.15). This exception object is then passed from the point where it was thrown up the stack to the closest try-catch handler that can process the exception (Section 3.13.2.5). When crossing borders of consecutive scopes, the destructors of all fully constructed objects are guaranteed to be executed. This means all stack-allocated objects will be properly destroyed and their allocated resources freed. This process is called stack unwinding . But what happens to objects that are not fully constructed – for example, if an exception is thrown in the constructor? If members of this class are properly RAII designed, then any members that have been created and allocated resources will also be properly destroyed, and their resources will be released.

Smart pointers, discussed in the next section, realize the RAII principle for managing computer memory resources.

5.3 Smart Pointers – An Overview with Examples

In this section, we will discuss the three smart pointers unique_ptr, shared_ptr, and weak_ptr, as well as the ways they are created and used.

5.3.1 ( ) More on

) More on std::unique_ptr

5.3.1.1 Context for Using std:: unique_ptr

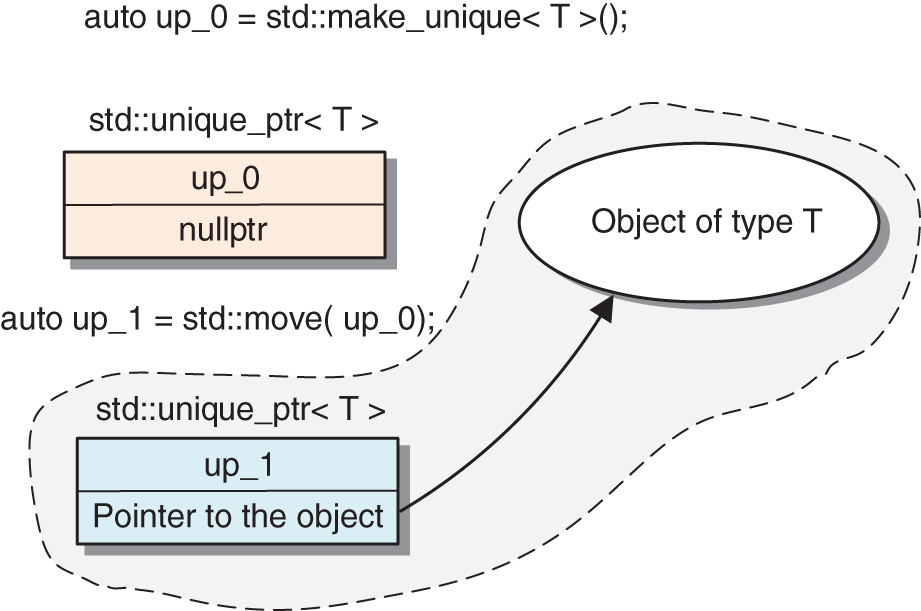

Using unique_ptr is simple, especially if we remember one rule: a unique_ptr cannot be copied, i.e. there should not be two unique_ptr

s holding a pointer to the same object. However, a unique_ptr can be moved: i.e. it can pass its held object to another unique_ptr. To force a move rather than a copy, we can use the std::move function. This rule also says that we should not initialize unique_ptr with a row pointer (see Section

5.3.1.4). Instead, we should use the std::make_unique helper, as discussed earlier (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 Smart pointers explained (in CppBookCode, SmartPointers.cpp).

| Smart pointer | Description | Examples | ||

unique_ptr |

unique_ptr is a template class designed for exclusive ownership of an object or an array of objects, so it automatically deletes its held object(s). A unique_ptr object behaves like a pointer to the held object(s). Its properties are as follows:

A single unique_ptr< T > takes responsibility for the lifetime of a single object T.

It cannot be copied, but it can be moved to other

|

unique_ptr is used to take over an ordinary pointer returned by calling the new operator (GROUP 4, Table 3.15). But in most cases, it is best not to call new at all – instead, the make_unique helper function should be used. It lets us pass value(s) to the constructor of the constructed object, so the objects will be zero-value initialized (i.e. set to their zero state), as for the real_array

_1. On the other hand, elements of an array pointed to by real_array_0 are not initialized. In almost the same way, unique_ptr can be used to control the access and lifetime of arrays of objects allocated on the heap . The creation of an array is indicated by adding [] to the template type of the unique_ptr.Smart pointers have overloaded pointer access operators, so they can be used like any other pointers. We can also check to see whether a unique_ptr contains a valid object. It can also be reset to a new object or nullptr . In this case, the previously held object will be immediately deleted, as shown in the last line.

|

||

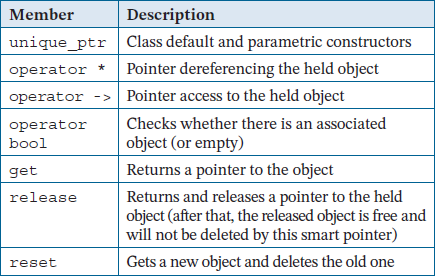

shared_ptr |

shared_ptr is used to share access to a single object among multiple parties. Unlike unique_ptr, there can be many shared_ptr objects pointing at a single object. A special reference counter is maintained to control how many shared_ptr

(s) point at a given object (see the illustrations in this table). If this value falls to 0, the controlled object is destroyed.Basic facts about shared_ptr

:

An example of an object The reference counter is 1; the weak |

In most cases, it is best to use the

It is also possible to create a shared_ptr from the unique_ptr. However, unlike with the family of shared pointers, we need to use the move function since unique_ptr cannot be copied. In the previous example, an object is taken over by the shared_ptr sp_2, whereas up_0 is left empty. There is no problem with copying sp_3 from sp_2, though. After running the previous code, this is displayed:

|

||

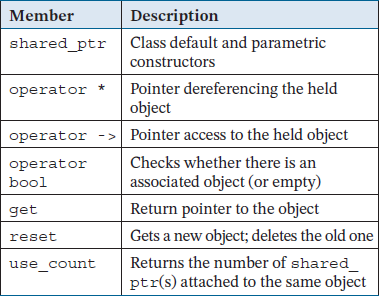

shared_ptr frequently used function members:

|

shared_ptr can also take responsibility for the lifetime of an array of objects. It overloads the subscript operator, so it behaves like an ordinary array pointer. Again, there can be more than one shared_ptr attached to such an array of objects – in the previous example, there are two such shared pointers: sp_4 and sp_5. This time the output is as follows:

Note that at first, sp_4_count is 1. Then all eight empty strings accessed via sp_4 are displayed. After that, sp_4 has been joined with sp_5, which causes the reference counter of each to be increased to 2, as displayed on the next line. Finally, all AClass objects are deleted, as manifested by the messages from the AClass destructor. This happens since all shared_ptr objects went out of scope and have been deleted, which entailed disposal of all their held objects. These are two AClass objects and eight AClass objects from the array. |

|||

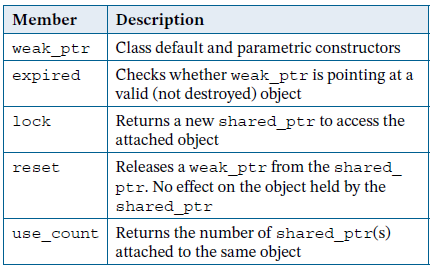

weak_ptr |

weak_ptr usually cooperates with a shared_ptr and contains a non-owning reference to an object, which is managed by an associated shared_ptr

:

weak_ptr frequently used function members:

The reference counter is used to count the number of attached |

|

||

|

In the previous code, first the |

|||

First, let’s create a small TMatrix class; see Listing 5.2. With unique_ptr, we can easily write a function that creates and returns a TMatrix object wrapped up into the smart unique_ptr. Some programmers prefix the names of such “creator†functions with Create_ or Orphan_ to indicate that the function is creating an object but then giving it away to an “acceptor†function.

An example OrphanRandomMatrix is outlined on lines [12–19]. Again, we take advantage of the auto keyword to save on typing the full name unique_ptr< TMatrix >. After calling the make_unique helper on line [14], a smart pointer is created that holds a matrix object of the requested dimensions. Then we are free to do some initializations to the matrix, e.g. with random values. Finally, on line [18], this smart pointer is returned by value. As a result, the matrix object is safely passed out of the OrphanRandomMatrix function.

The subsequent code fragments show how to pass a matrix object with and without using unique_ptr. These can be called consumers, and they accept the matrix object in various ways:

- If we wish to perform an action on a

TMatrixobject, then instead of passingunique_ptr < TMatrix >, a simpler way is to directly use a reference or constant reference toTMatrix, as in the following function: - If we need to pass a pointer to a function in the realm of smart pointers, we pass a constant reference to

unique_ptr< TMatrix >. By doing this, we can access the held object without changing the smart pointer. An example is shown in the second version of theComputeDeterminantfunction:This method can be used if we wish to express the fact than a passed object is optional or might not exist, which is manifested by passing a

nullptr. But in that case,std::optionalprovides a viable alternative (Section 6.2.5). As always when working with pointers, before accessing an object, we need to remember to check whether the pointer is anullptr, as shown on line [39]. - If we need to pass an object to a function that will assume ownership of it, we do this by passing a non-constant reference to the

unique_ptr, such as in the following function. By doing this, we can change the passedunique_ptrand, for instance, take over its held object:On line [50], a new local

unique_ptr< TMatrix >namedmyMatrixis created, which takes over theTMatrixobject provided by thematrixparameter. This is done with thestd::movehelper. Otherwise, the code will not compile since theunique_ptrs cannot be copied to avoid pointing at the same object, as already mentioned. Then, on line [55], the function exits, the local objectmyMatrixis destroyed, the heldTMatrixobject is also destroyed. If not for line [50], the object would not be taken over and would still exist in the code context outside this function.It is also possible to pass a pointer to a smart pointer, as follows:

But in this case, we need to check that the passed pointer is not a

nullptr, and then check that the held object is not anullptr. So, the usefulness of passing a smart pointer via an ordinary pointer is doubtful. - Passing

unique_ptr< TMatrix >by value forces us to take over the object, as in the following function:

Since the matrix is a local object of the AcceptAndProcessMatrix function, it can hold a TMatrix object by itself. However, it can also hold a nullptr, so before using the matrix object, we have to make sure it is valid. If this is an assumed precondition, it can be verified using assert, as on line [70].

Finally, the following function shows some contexts for calling these functions:

Note that before accessing held objects, we always need to make sure the smart pointer is not empty. This is the same strategy used with ordinary pointers (Section 3.12). Also notice that taking over an object with a called function should be used with care since after its execution, the smart pointer will be empty, as on line [95] of Listing 5.2.

Finally, let’s analyze two ways of calling the AcceptAndProcessMatrix function, as shown on lines [103, 107] in Listing 5.2. In the first, we need to use the move helper again to take over an object from matrix_1. But in the second, a temporary unique_ptr< TMatrix > is created, which is then moved to the formal parameter of AcceptAndProcessMatrix by means of the move constructor.

5.3.1.2 Factory Method Design Pattern

Listing 5.3 shows how to create a simple version of the factory method design pattern, also known as a virtual constructor (Gamma et al. 1994). This is a software component (a class or a function) that, given a class ID, creates and returns a related object. Usually, the factory works for a (larger) hierarchy of related classes, as in the example code.

More on this class hierarchy and overloaded functional operator () with the override specifier will be presented in Section 6.1. In this section, we concentrate on object management. In this respect, a factory function is designed to operate on a class ID, defined with the scoped enumerated type EClassId (Section 3.14.6). With this, each object type can be uniquely identified, as in the following code snippet:

Thanks to the auto keyword, the compiler automatically infers the type of the return value (the same unique_ptr< B >

). Here, only lines [59–61] return valid objects. Nevertheless, all function paths need to return a value, so an empty unique_ptr is left on line [66]. Finally, we can employ our factory in a short task, as follows:

A nice thing about unique_ptr

s is that they can be stored in SL collections, such as the vector on line [70]. Since unique_ptr cannot be copied, the compiler has to invoke a move version of push_back on line [72]. An even better alternative is the direct construction of a unique_ptr object “in place,†which is accomplished by calling emplace:back on lines [74, 76] (Cppreference.com

2018). After exiting, we see the following messages:

Object E was immediately deleted as a result of the replacement with object D on line [78]. Then actions were invoked on all objects in the collection. Finally, the vector theObjects, which is an automatic variable in this context, was destroyed along with its elements. This entailed executing the destructors of the factory objects. An extended version of this project will be presented in Section 6.1.

Because of its behavior, the factory method is sometimes referred to as a virtual constructor (Gamma et al. 1994), although in C++, constructors cannot be declared virtual (Section 4.11). Virtual functions also cannot be called from within a constructor.

5.3.1.3 Custom deleter for unique_ptr

As mentioned earlier, unique_ptr can be endowed with a custom delete function. Although we do not often write our own deleter, this is also an occasion to see some interesting constructions, which we will explain.

A custom deleter can be a function or a functor, i.e. a class with an overloaded function operator (Section 6.1). Lines [84–88] of the previous code snippet define the AClass_delete_fun lambda function (Section 3.14.6). Note that in this context, we need a semicolon after the lambda function definition. Remember that when adding our own deleter, we take over all actions associated with object disposal. That is, the rest of unique_ptr will do nothing. Therefore, AClass_delete_fun has to call delete on the provided pointer, as it does on line [87]. But before or after doing that task, it can e.g. write to a log file or perform another action, as discussed in the next example. The custom deleter for unique_ptr needs to be added to unique_ptr

’s template parameters, just after the class name of the object to be held. To infer the type of the function on line [91], we use the decltype keyword (Section 3.7). Then, in the constructor, since make_unique cannot be used with custom deleter, we need to provide a pointer to the object and a custom deleter.

In the second example, rather than deleting a pointer, we use a custom deleter to automatically invoke the close function on an opened file. We start with the type definition on lines [1–2]. To provide a function pointer to the second type argument of the unique_ptr template, the std::function is used (Section 3.14.9).

The lambda function that closes a FILE object1 through the provided pointer is defined on line [5]. Then, a unique_ptr with this custom function is defined on line [9]. It creates and opens a file object from the disk file myFile.txt in read mode (

"r"

) and serves as a smart pointer to that object. When the file smart pointer is automatically disposed of, file_close_fun is also automatically called, which in turn closes the file object. On the other hand, the default (and also custom) deleter is called only if a held pointer is not nullptr . Hence, if a file has not been opened, fclose will not be called at all.

Remember that a custom deleter adds to the unique_ptr type. Hence, two unique_ptr

s to the same object type but with different deleters are considered different types.2

5.3.1.4 Constructions to Avoid When Using unique_ptr

Finally, let’s discuss a few things to be aware of when using unique_ptr. When defining unique_ptr, we can use auto to automatically infer types and to avoid typing. But this is possible only when using make_unique, as shown here:

If we forget about make_unique and leave only auto, then an ordinary pointer is generated, as on line [2]. It will not be guarded by a unique_ptr, so it must be explicitly destroyed, as on line [4]. On the other hand, a unique_ptr can be created directly by a return of the new operator or as mentioned with make_unique

:

We should also be very careful not to create a unique_ptr from an ordinary pointer since it is possible to create more than one unique_ptr holding a link to a single object. Inevitably this will cause a program error when we try to call delete more than once on the same memory location.

Finally, we must avoid creating a unique_ptr on the heap with the new operator. For some reason, in the SL, the new operator was not forbidden for unique_ptr.

5.3.2 ( ) More on

) More on shared_ptr and weak_ptr

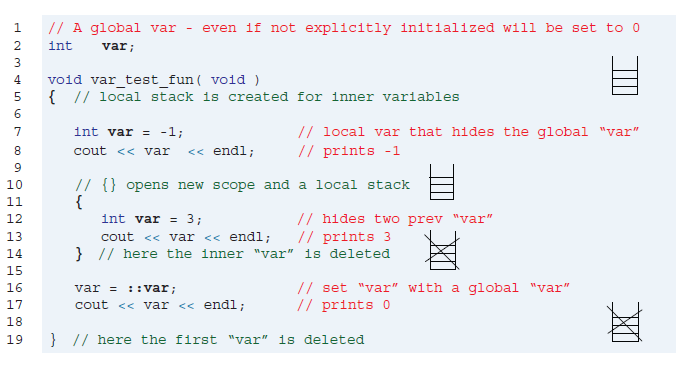

In this section, we show how to use the shared_ptr and weak_ptr smart pointers when creating a doubly connected list, as shown in Figure 5.1. shared_ptr cannot be used in two directions because such a construction would make the two objects dependent on each other. In effect, both objects cannot be deleted, which will result in a memory leak despite using smart pointers . To overcome such mutual dependencies, the weak_ptr comes to play. In our example in Listing 5.4, a backward connection is created by using weak_ptr. Let’s analyze the code: it consists mainly of the N class, which defines a single node, and a function showing the process of creating and using a list.

Figure 5.1 A double-linked list needs two different types of pointers to avoid circular responsibility. Forward links are realized with shared_ptr and backward links with weak_ptr.

The N class implements a node class that stores a string and that can make forward and backward connections. The forward connection is realized by the shared_ptr fNext, defined on line [9]. This also ensures the proper destruction of the subsequent objects. There is also a backward connection to the preceding object, obtained via the fPrev link, which is a weak_ptr [10]. As a result, access in both directions is possible, but object dependency is only in the forward direction, so we avoid a circle. The functional operator defined on lines [23–34] simply returns the concatenation of text from the preceding node, its own text, and text from the successor node. Naturally, a node may not have a predecessor or successor, so each access needs to be carefully checked as on lines [28, 31]. Having defined a node, let’s see how to construct and use a list like the one in Figure 5.1.

The list is created based on an initializer list provided in the for loop on line [45]. Then we have two possibilities: either we are adding the very first node, in which case line [49] is executed; or we are adding new nodes to an existing list, on lines [54–55]. Going into detail, first a new node is created, which is identified by a shared pointer. This is used to initialize the fNext pointer of the current object at the end of the list. Then, we move the end of the list to the just-created object. After the list is ready, the string-composing function is called from each node in the list, as on lines [63–64]. The whole list is traversed, and at each node, the previous, current, and next nodes are accessed to concatenate their strings. A node may be at one end of the list, so each time we access a node, we need to check whether the pointers are pointing at valid objects. The output of our function looks as follows:

Notice that the borderline nodes produce shortened output. After the list is processed, the objects are automatically deleted thanks to the shared pointers, in the order in which were created, from A to F.

Finally, note that the SL offers the std::list class, which implements the list data structure. Therefore, if we need the standard list functionality, we can use a ready and verified solution instead of writing our own code. The std::list class will be used and presented in Section 6.1.

5.4 Summary

Things to Remember

Questions and Exercises

- Explain the main idea behind using smart pointers.

- Explain the main differences between

unique_ptrandsmart_ptr. - A ternary tree is a data structure in which each node can have up to three children (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ternary_tree). Such structures are used, for example, for spell-checking. In such a case, the node also contains a one-letter data member. Implement a ternary tree composed of objects like the

Nclass in Listing 5.4. Each node should haveunique_ptrmembers to link to its three children. - In the following code snippet, identify the object dependency arising on line [25]:

Remove the circular dependency between the objects. Hint: change the type of the smart pointer on line [16].

- Design and implement a simple memory-allocation method for an embedded system. For safety reasons, a single statically allocated memory block can be used from which all partitions resulting from memory requests are created. Hint: read about and then implement the buddy algorithm (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddy_memory_allocation).

- Design and implement a class to represent a submatrix (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matrix_(mathematics)) in a matrix object using the proxy pattern, presented in Section 4.15.5. The proxy has no data of its own but operates on the data of its associated matrix. But it defines its own local coordinate system and behaves like any other matrix. Hint: after making some modifications to the

EMatrixclass in Listing 4.7, derive a proxy class to represent submatrices. Such a proxy should not allocate its own data but should be constructed with a reference to its associated matrix. Accessing an element in the submatrix should result in the data coordinates being transformed to the coordinate system of the associated matrix.

Notes

- 1 FILE is a C-style type that identifies a file stream and contains its control information. We show it here as an example of porting code. In C++, a preferable way of using file streams is with the filesystem library (Section 6.2.7).

- 2 More on smart pointers with custom deleters and cloning operations can be found in Jonathan Boccara, “Expressive code with C++ smart pointers,” Fluent{C++}, www.fluentcpp.com/2018/12/25/free-ebook-smart-pointers.