Oconaluftee River, Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Not until well into the 20th century did park planners turn their attention from the West’s grand vistas to the more subtle beauties of eastern scenery. Between 1919 and 1926, Congress authorized the area’s first three parks in the Appalachian Mountains. Today these parks—Acadia, Great Smoky Mountains, and Shenandoah—rank among the most visited in the nation. Six other parks round out the roster of the region’s protected places.

Plants and animals that inhabit the mountains, islands, sea, and tide pools along a stretch of wild Maine coast are protected at Acadia National Park. The hardwood forests and flowering meadows of Virginia’s Shenandoah, on land that had been logged, farmed, and grazed for 250 years, are studies in nature’s power of recuperation. Great Smoky preserves large stands of virgin forest on 6,000-foot slopes along the Tennessee–North Carolina border.

Since the 1920s, the U.S. Congress has moved to safeguard other distinctive eastern biomes. The world’s longest known cave network, Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, has some 400 miles of mapped passages. One of the newer parks in the system, South Carolina’s Congaree nourishes 11,000 acres of old-growth bottomland forest.

Underwater wilderness awaits visitors to Florida’s Biscayne National Park, home of the northernmost living coral reef in the continental United States. West of Biscayne lies Everglades National Park, established in 1947 to safeguard the unique ecosystem created by a slow-moving river, inches deep and some 50 miles wide. Endangered due to climate change and rising sea levels, Everglades provides habitat for an enormous variety of wildlife.

Off the coast of Florida and about 70 nautical miles west of Key West, on a 7-mile-long archipelago rich with birds and marine creatures, Dry Tortugas National Park maintains an abandoned 19th-century brick fortress, the largest in America at the time. And far to the southeast, Virgin Islands National Park protects much of St. John, where hillsides thick with bay, mango, and trumpet trees slope to crescent beaches rimmed by coral reefs.

Along Park Loop Road, near Thunder Hole

Maine

Established February 26, 1919

50,000 acres

Acadia National Park provides proof that a park doesn’t need vast wilderness to offer gorgeous scenery and the chance for immersion in the natural world. Small for a national park, composed of a patchwork of public land surrounded by towns and villages, Acadia preserves a glacier-carved landscape of rugged mountains, pristine lakes, lush forests, and long stretches of Maine’s famous rocky shore. It ranks among America’s most visited national parks. No one who sees it wonders why.

Most of Acadia is located on Mount Desert Island, just off the central Maine coast. Separate areas of the park lie on the Schoodic Peninsula, on the mainland to the east, and on Isle au Haut, a small island to the southwest. The Wabanaki Indians called Mount Desert Pemetic, “the sloping land,” and it’s true that flat places are scarce here. Glaciers, which retreated around 17,000 years ago, cut narrow valleys now filled with lakes and arms of the Atlantic Ocean and carved steep cliffs.

Glaciers also scoured granite mountaintops, leaving little soil to support forest. The lack of trees caused French explorer Samuel de Champlain, who sailed past in 1604, to call the island Monts Desert (barren mountains).

In the 19th century, Mount Desert Island’s beauty and remoteness began attracting wealthy visitors looking for a retreat from bustling cities. Vanderbilts, Astors, Carnegies, and other illustrious families built magnificent mansions (which they called “cottages”) on the island’s northeast coast. The area became known as Millionaires’ Row. As the 20th century arrived, the town of Bar Harbor had dozens of hotels, and people began to worry that Mount Desert was losing the qualities that had made it so attractive.

Some of the wealthy part-time residents began using their influence to push for a national park on the island. Among them was oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who donated nearly 11,000 acres to what was first called Lafayette National Park. (The name was changed to Acadia in 1929.) The first national park in the East, Acadia grew bit by bit over the years, and now it occupies 50,000 acres, including about 60 percent of Mount Desert Island.

A massive fire in 1947 destroyed Millionaires’ Row and also brought about a major change in the island’s ecology. Spruce-fir coniferous forest once dominated Mount Desert, but the fire created open areas that were colonized by faster-growing hardwood trees, such as birch, aspen, and maple. In fall, the many-hued foliage of these hardwoods blaze brightly, recalling the “year that Maine burned.”

► HOW TO VISIT

The Hulls Cove Visitor Center, in the town of Hulls Cove—in the northernmost part of the park—marks the start of Acadia’s famed Park Loop Road. This 27-mile scenic drive (closed in winter) passes many popular sites, including Otter Cliffs and Jordan Pond. A side road a quarter mile from the start of the road and another road 3.5 miles in leads to the top of Cadillac Mountain, with its splendid panorama of Mount Desert Island. Hike or bike a section of the park’s unique and historic carriage roads, which offer short, easy jaunts and longer options.

If you have time, explore the park’s western side, with its less-traveled trails and fascinating tide pools. To see many more miles of beautiful rocky shore, return to the mainland and head east to Schoodic Peninsula, about an hour’s drive from Bar Harbor.

How best to move through the park in peak season? Don’t drive into the park in July or August. Traffic can hinder your enjoyment of Acadia’s beauty, so get a map to locate trailheads and attractions, and use the free Island Explorer bus (late June to mid-October; exploreacadia.com; 207-667-5796).

Eastern Side of the Park

A leisurely drive around the Park Loop Road is Acadia’s must-do experience. It’s most pleasant in the off-season or early in the morning any time of the year. No matter when you go, you’ll see some of the finest scenery in the park.

Leaving the Hulls Cove Visitor Center, you soon reach overlooks with expansive views of Frenchman Bay. At the Sieur de Monts Spring, the Abbe Museum (abbemuseum.org; 207-288-3519) focuses on the Wabanaki Native American culture. The small Wild Gardens of Acadia (friendsofacadia.org) provides a good introduction to the flora of Mount Desert Island.

A bit farther along the road is the trailhead for one of the park’s most popular, strenuous, and potentially dangerous trails. The Precipice Trail ascends the near vertical face of Champlain Mountain, so steep in places that iron ladders and rungs have been set into the rock to help climbers. Less than a mile long, Precipice presents a challenge that’s irresistible to many Acadia visitors. The park stresses that it’s more of a “non-technical climbing route” than a trail, and anyone who attempts it should be physically fit, wear sturdy hiking boots, and have no fear of heights. (The trail is often closed in spring and summer to protect nesting peregrine falcons.)

Continue to Sand Beach, where the water is always cold. Even in summer, the water temperature rises to only 55°F. A lifeguard is on duty here Memorial Day through Labor Day.

Watch for the small parking area at popular Thunder Hole. Here, a small cave roars like thunder when the tide is just right and a large wave hits the shore, compressing the air inside the cave opening. When a powerful surge hits, water can shoot some 40 feet into the air.

Ahead lies one of Acadia’s iconic sights: the 110-foot-high rock wall known as Otter Cliffs. The landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who helped design the Loop Road in the 1930s, referred to this scenery as having “a certain bigness of sweep.” His quirky phrase seems apt here; you’ll certainly want to stop and admire the grand terrain. Park and maybe walk the 2-mile Ocean Path to Otter Point, find a rock, sit down, and take it all in.

About 1.5 miles past the causeway at Otter Cove, watch for a small, unmarked parking area. Take the stairs down to Little Hunters Beach, a picture-perfect spot. The shore is covered in the small, rounded rocks called cobblestones. When waves come in, the cobbles make a faint tapping sound. Thousands of rocks have been taken over the years by visitors. But it’s illegal to take rocks (or any other natural feature) from a national park.

The Loop Road continues inland to reach lovely Jordan Pond, one of the park’s most popular spots, in part because of the restaurant, which is operated by a private concessioner May to late October (acadiajordanpondhouse.com; 207-276-3316). The view from the lawn takes in the pond and, in the distance, the twin rounded hills called The Bubbles. A glacier carved this valley, pushing rock debris as it moved. When it melted, the glacier left a wall of rock, called a moraine, as a natural dam. The Jordan Pond area is a great place to explore carriage roads, as several radiate out from this point.

A rewarding hiking trail, the 3.3-mile Jordan Pond Shore Path circles the pond, crossing wetlands and brooks along the way. As you pass South Bubble, near the northern end of the pond, watch for rock climbers scaling the cliff face. As the Loop Road skirts Eagle Lake and completes its circuit, a side road leads to perhaps Acadia’s most celebrated destination. At 1,530 feet, Cadillac Mountain is the highest point along the North Atlantic seaboard. The vista from the pink granite summit deserves the oft-used term “breathtaking.” Below, islands dot Frenchman Bay like green stepping-stones leading to the Schoodic Peninsula.

The blocky red-and-white Egg Rock lighthouse sits in the mouth of the bay. To the south, broad, low islands—Baker, Sutton, and Great and Little Cranberry—seem to float in the Atlantic like jigsaw puzzle pieces uncoupled from the ragged shore.

From October 7 to March 6, the top of Cadillac Mountain is the first place in the United States to see the sunrise. Year-round, visitors rise before dawn to drive to the summit and greet the new day. The Blue Hill overlook makes a great place from which to watch the sunset. In peak season, try to avoid driving up Cadillac at midday, when finding parking can be difficult.

Of course, you can also hike to the top of Cadillac. The North Ridge Trail (2.2 miles) and the more strenuous South Ridge Trail (3.5 miles) are popular ways to the summit.

Lodge built by John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

The Carriage Roads

Park donor John D. Rockefeller, Jr., loved Mount Desert Island. He had a distaste for the “garish advances of civilization,” and that included motor vehicles. In 1913 Rockefeller began planning a network of what he called carriage roads through some of the island’s loveliest areas. Walkers, horses with riders, bicyclists, and of course carriages were welcome; automobiles were (and remain) banned.

More than 50 miles of broad, broken-stone carriage roads were built; 45 miles are inside the park boundaries. Rockefeller also financed 16 of the 17 imposing stone bridges along carriage roads, built by local stoneworkers. As the story goes, over the years they got so good at it that Rockefeller had to remind them that he wanted a rustic look, not smoothly finished rock. (The bridges are actually steel-reinforced concrete with rock exterior.)

Carriage roads offer a wonderful way to explore the park on foot, by bike, and, in winter, by cross-country ski. Among the places with quick access to the road system are Jordan Pond, Bubble Pond, the north end of Eagle Lake, the Brown Mountain Gatehouse, and the Hulls Cove Visitor Center. You can choose routes ranging from short and easy to all-day excursions. Signposts at all intersections make navigation simple. Remember that bicycles are not allowed on carriage roads outside the park boundary, in the area south of Jordan Pond, and between Seal Harbor and Northeast Harbor.

If it’s your first visit to Acadia, consider the 3.3-mile Witch Hole Pond Loop, beginning at an impressive bridge beside Duck Brook Road. This route passes several wetlands areas and is great for wildflowers in late spring and summer.

Bass Harbor Head Lighthouse, Mount Desert Island

Somes Sound carves a long sea inlet into the heart of Mount Desert Island. To its west, the “quiet side” of Acadia National Park rewards visitors with trails that are less known, and so less crowded, than those closer to Bar Harbor.

Beech Mountain offers a fine view of Long Pond in return for 1.2 miles of moderate effort. For a challenge and another perspective on Long Pond, walk the 1.2-mile Perpendicular Trail, with its rock stairs, up Mansell Mountain. Make a 2.4-mile loop by following the Mansell Mountain and Cold Brook trails back to the trailhead. A trail with good views of Somes Sound leads to the top of Acadia Mountain.

The pools of water on rocky shore ledges host a fascinating array of creatures visible at low tide, from barnacles to periwinkle snails, crabs to sea anemones. Sites such as Ship Harbor, Wonderland, and Seawall offer fine opportunities to sit quietly and observe life in the intertidal zone. If the tide is out, you might want to consider tide-pooling: walking around and exploring the pools without stepping inside them. Be careful on slippery rocks, watch for the incoming tide, and leave sea creatures in place.

Sign up for a ranger-led program such as Life Between the Tides (fee) to learn about this diverse life zone. Make your way to or call the Hulls Cove Visitor Center (207-288-3338) for schedules and tickets.

While you’re in the area, don’t miss the famous Bass Harbor Head Lighthouse, reached by taking Lighthouse Road south from Maine 102A. The 1858 brick structure is on the National Register of Historic Places and has been featured on countless postcards and calendars. Stay on marked paths. The lighthouse itself is private.

Continue north on Maine 102A and Maine 102, passing through several villages, to reach Pretty Marsh, a somewhat remote part of the national park that’s also one of its nicest and most scenic picnic spots. A stairway makes it easy to descend to explore the shore of Pretty Marsh Harbor.

If it’s a warm summer day and you feel like taking a dip, head to Echo Lake, the most popular swimming site on the island. A lifeguard is on duty from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

(Many Mount Desert lakes function as water suppliers and are closed to swimming.)

This disjunct section of the park is reached by following Maine 3 to Ellsworth and heading east on US 1 and south on Maine 186. The trip is well worth the effort: A 6-mile road hugs the shore of the peninsula, offering views of some of the park’s best coastal scenery. On a day when the waves are big, the sight of water crashing and foaming against the rocks can be spectacular, especially at Schoodic Point.

Several pullouts provide places from which to enjoy the views. Interpretive roadside signs lend insight on the area’s wildlife, history, and geology. In places it’s easy to see where black veins of magma were squeezed up into fractures in huge pink granite boulders during long-ago volcanic events.

From Schoodic viewpoints you can see Mount Desert Island to the west, as well as a variety of islands and waterbirds. Take the short, unpaved side road to the top of 440-foot Schoodic Head for an even better panoramic vista.

Relatively few people visit this special spot, which was given its name, High Island, by Samuel de Champlain in 1604. To reach it requires a drive of about 1.5 hours from Bar Harbor to the town of Stonington and then a ride on a private boat (isleauhaut.com; 207-367-5193) that takes passengers on a first-come, first-served basis.

Isle au Haut is about 6 miles long by 2 miles wide. Around 2,700 acres of the island belong to the national park; the rest is private property. A small year-round community grows to several hundred when the summer-only residents arrive.

Limited seasonal camping is allowed only by prior reservation, made by mail application to the park. Private lodging is also available. The number of day-trippers is limited. What this means is that visitors find wonderful solitude on the 18 miles of hiking trails that meander around the southern part of the island.

Bird-watching, picking wild blueberries, picnicking, biking, and simply reveling in the rocky coast scenery are among the favorite activities on little Isle au Haut. Walking Western Head Road, the Cliff Trail, and the Western Head Trail adds up to a pleasant loop of 3.7 miles.

White-tailed deer

|

How to Get There From Portland, ME (about 160 miles southwest), take I-95 to Bangor and then go south on I-395, US 1A, and Maine 3. When to Go Many park facilities are closed from around late Oct. through April or May. July and Aug. see heavy visitation and high traffic. Late June and Sept. offer pleasant temperatures and less crowding. Expect peak foliage in mid-Oct. Lodging In the park, run by a concessioner, are Keeper’s House Inn and Cottage Rental Robinson Point Lighthouse (keepershouse.com; 207-335-2990). Lodging is plentiful in Bar Harbor and nearby towns. The Mount Desert Chamber of Commerce (mountdesertchamber.org) can provide information. Another good source is the Bar Harbor Chamber of Commerce (barharborinfo.com; 207-288-5103). |

Camping Blackwoods Campground (275 campsites), 5 miles south of Bar Harbor, is open May though Oct. as well as April and Nov., depending on weather conditions. Seawall Campground (198 campsites), 4 miles south of Southwest Harbor, is open late May through Sept. For reservations: recreation.gov; 877-444-6777. There is no backcountry camping in the park. Visitor Center Information is available year-round at park headquarters on Maine 233. On Rte. 3, the Hulls Cove Visitor Center is open daily mid-April through late Oct. Headquarters

20 McFarland Hill Dr. |

Elkhorn coral

Florida

Established June 28, 1980

172,900 acres

Biscayne National Park serves as a popular playground for boat owners in the Miami metropolitan area, and for good reason: The beautiful blue waters of Biscayne Bay, within sight of the city skyline, offer a wealth of opportunities for cruising, fishing, and picnicking along the shore.

Yes, there are activities galore, but the park is much more than simply a sunny, fun weekend playground. Visitors who explore the park’s diverse attractions discover a watery world encompassing wildlife, historic shipwrecks, and peaceful lagoons where the loudest sound is the splash of kayak paddles.

The park’s colorful human history begins with the Native American Glades Culture, which left shell mounds in the area that date back more than 2,500 years. In the 19th century, farmers grew pineapples and limes on the Florida Keys; later, Adams Key was home to the Cocolobo Club, a private getaway that hosted several U.S. presidents.

There’s a colorful story behind the establishment of the national park. Conservationists and developers were locked in a bitter, years-long battle in the 1960s (see here).

Ninety-five percent of the park area is made up of the waters of Biscayne Bay and the nearby Atlantic Ocean. The park encompasses four ecosystems:

• a narrow strip of mangrove forest bordering the shore of Biscayne Bay

• a large part of the bay itself

• the northernmost islands of the Florida Keys

• the northernmost section of the world’s third largest coral reef, in the Atlantic, just beyond the Keys

Of the park’s lures, what’s most fascinating to many visitors is the array of colorful fish and other animal life that populates the coral reef, from sharks to sea turtles to the coral itself. In 2014 the concessioner authorized to operate boat tours in the park ceased operations, making it difficult for most visitors to access the bay, the Keys, and the reef. At this writing, the park is going through the process required to authorize a new concessioner and resume park boat tours. Trips could start up again in 2016.

► HOW TO VISIT

At Biscayne National Park, exploration focuses on the water. Take in the exhibits at the Dante Fascell Visitor Center on the mainland and check the schedule for ranger-led paddling trips (usually December through April; 786-335-3612) along the longest mangrove forest on Florida’s east coast. A snorkeling trip to the reef—another water-based activity—is a truly memorable experience.

Also consider discovering the park’s watery world on your own. Rent a kayak from an outfitter outside the park and paddle around the quiet mangrove shoreline of the mainland, right near the visitor center. Beginners welcome.

Visitors who take private boats into the park should be aware of regulations applying to both personal safety and protection of the environment. It’s imperative to have nautical charts and to know tide schedules to avoid running aground in shallow water. Coral reefs and other areas of the sea floor are easily damaged by anchors and boat hulls.

Boca Chita Key and the Miami skyline

Mainland, Biscayne Bay, & the Keys

Begin your visit with an overview of the the park. The interpretive videos and exhibits at the Dante Fascell Visitor Center at Convoy Point will help orient you.

A canoe or kayak trip along the shoreline could include sightings of wildlife, including manatees, the huge, gentle marine mammals that feed on underwater grasses. Manatee sightings are most likely in winter.

Birds found here include brown pelicans, gulls, terns, herons, egrets, magnificent frigatebirds, and sometimes southern Florida specialties such as mangrove cuckoos and white-crowned pigeons. You can also snorkel near the shore, although the underwater life here is not as varied and colorful as that on the coral reefs, 10 miles out to sea.

There’s a short Jetty Trail along the shore from which visitors occasionally spot manatees, as well as a variety of birds. Rarely, an American crocodile makes an appearance.

Visitors with their own boats or those who sign up with an independent outfitter begin their trips in the shallows (4 to 10 feet deep) of Biscayne Bay. Turtle grass, shoal grass, and similar vegetation covers the bay floor, providing protection for breeding crabs, lobsters, shrimp, and other creatures. The occasional sea turtle or barracuda may appear below, and dolphins often accompany the boat.

The portion of the Florida Keys that includes the national park has islands large and tiny, with histories just as widely varied. At 7 miles long, Elliott Key is the largest of the park’s keys; primitive camping is allowed in designated areas; cold-water showers and drinking water are available.

A trail runs the length of Elliott Key, through a subtropical forest that is home to rare butterflies, including the Bahama swallowtail, and distinctive plants. (Biscayne National Park boasts several national champion trees. Indeed, many of the park’s tree species are found in the United States exclusively in southern Florida.) Elliott Key was heavily homesteaded in the 19th and early 20th centuries, though most evidence of that era has disappeared.

It will require a bit of planning, but if you can arrange to take a canoe or kayak trip into Jones Lagoon, south of Caesar Creek, your efforts will be well repaid. (Ranger-led trips are offered here on occasion; check with the visitor center.) This quiet site, too shallow for motorboat traffic, truly is a different world. In the mangrove-ringed lagoon you may see Cassiopea jellyfish (also referred to as upside-down jellyfish), along with sharks, rays, sea stars, and spiny lobsters

Boca Chita Key, smaller and lacking drinking water, is the park’s most popular island, with camping permitted. The island was once owned by businessman Mark Honeywell, who built several structures that still stand, including a 65-foot-high ornamental lighthouse. Visitors can climb the lighthouse when a park staffer or volunteer is present.

The Reefs

The coral reefs that stretch beyond the Keys are part of the world’s third longest coral reef system, following behind Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and the Mesoamerican Reef in the Caribbean Sea. Tours to the reef, which runs the length of the park’s eastern edge, offer the chance for snorkelers and certified scuba divers to enjoy the diverse and colorful life of this undersea ecosystem.

Fish are the indisputable stars of the marine show. Included are such species as butterflyfish, parrotfish, damselfish, pipefish, and barracudas. Nurse sharks and loggerhead sea turtles also can be spotted. Equally colorful, other creatures of the reef include sea cucumbers, Christmas tree worms, sponges, and of course the coral itself in an array of forms such as elkhorn, brain, sea whip, and sea fan. As beautiful as the reef is, it was the nemesis of the many ships that have run aground here. Biscayne National Park’s Maritime Heritage Trail, the only underwater archaeological trail administered by the National Park Service, includes six of the dozens of shipwrecks within the park. Mooring buoys and brochures interpret such wrecks as the Mandalay, which sank in 1966; the Alicia, which sank in 1905; and the massive Lugano, which went down in 1913.

Family Fun Fest is a free park program held on the second Sunday of the month from December through April.

Information

|

How to Get There From Miami, FL (about 35 miles north), take Fla. 821 (Florida’s turnpike) south to Homestead and go east on SW 328 St. to Convoy Point. When to Go Dec. through April is the most popular season, with moderate temperatures and fewer mosquitoes. Water is calmer and clearer for snorkeling in summer, however. Visitor Center The Dante Fascell Visitor Center at Convoy Point is open year-round. Visitors should contact the Visitor Center before arrival for the latest information on available tours and operators. |

Camping The park’s two campgrounds, on Elliott Key and Boca Chita Key, are accessible only by boat. Elliott has toilets, showers, and drinking water; Boca Chita has only toilets. Each camping area offers some 20 sites. Lodging Lodging is available in the towns of Homestead and Florida City, both 9 miles west. For more information, contact the Tropical Everglades Visitor Association (tropicaleverglades.com; 305-245-9180). Headquarters 9700 SW 328 St. |

Bald cypress trees

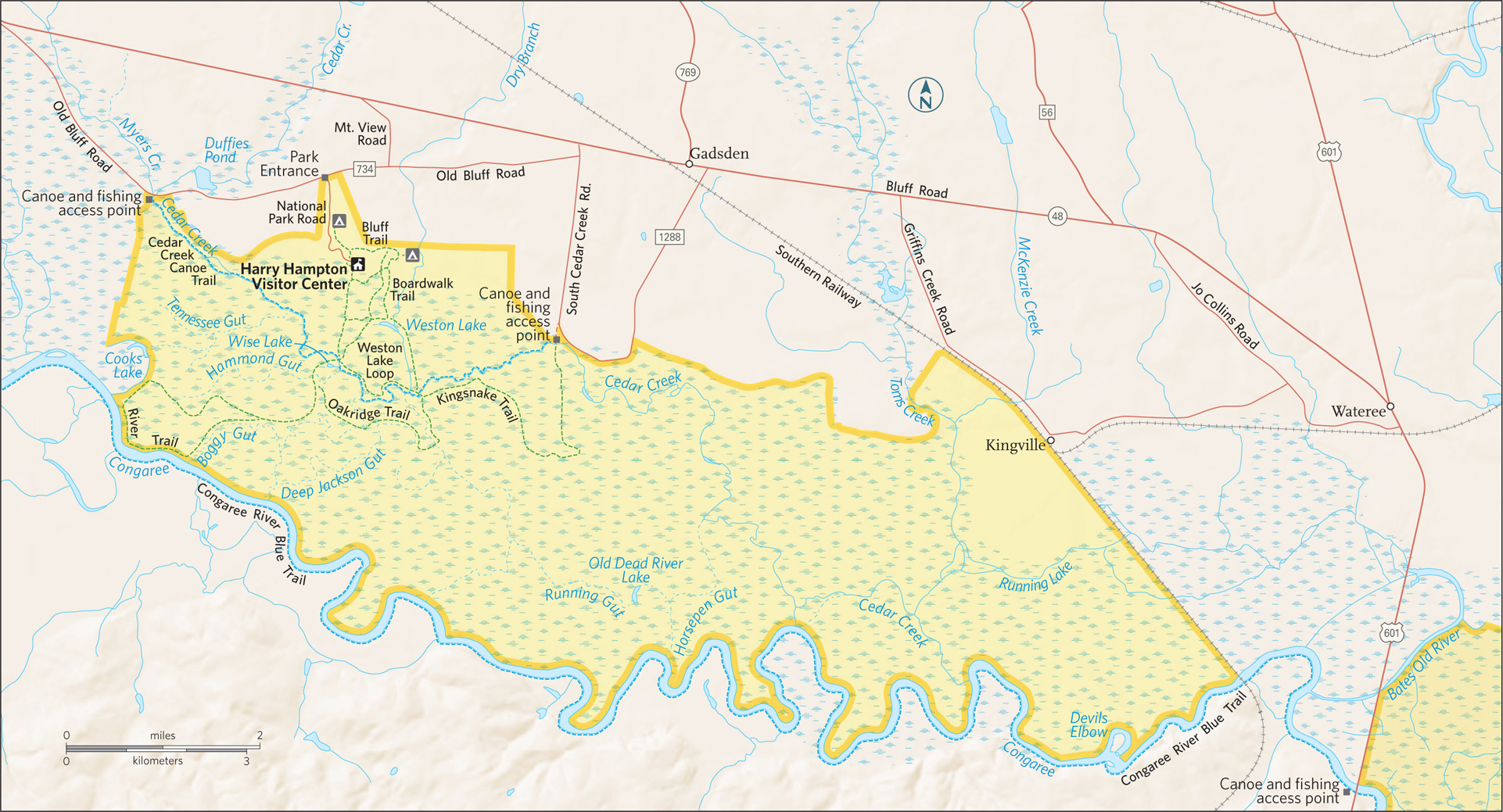

South Carolina

Established November 10, 2003

26,000 acres

In the early 21st century, the largest intact old-growth bottomland hardwood forest in the United States became Congaree National Park—literally shedding its ecologically inaccurate swamp designation in the process. It’s among the country’s least crowded parks, with just 110,000 or so annual visitors. Folks mostly stick to the northwestern corner of the park, near the visitor center, thus missing out on the moss-draped tangle of primeval floodplain forest that captivated European explorers in the 16th century.

Relative isolation has always been among Congaree’s assets. Though less than 20 miles south of urban Columbia, South Carolina, the park immerses visitors in otherworldly landscapes. Park officials manage Congaree as a federally designated Wilderness, emphasizing preservation and scientific research and minimizing development. In the wilds of Congaree, beams of sunlight stream in through perforations in the dense tree canopy, giant hardwood tree trunks look like dinosaur legs, and armies of conical “knees” rise from the bald cypress tree roots like stalagmites poking up through ferns and fungi. One park ranger described them as the clenched knuckles of a vast community of trees “holding hands” underground to hold each other up.

There are bald cypress trees deep in the woods that died more than a century ago, mostly the result of logging. The stumps that remain provide refuge for prothonotary warblers as well as for insects and fungi.

Before the days of federal protection, Congaree’s swamplike conditions literally protected many of its hardwood trees from ax-wielding outsiders. Still, by 1915 most of the original cypress tree population had been decimated; 500-year-old trees routinely were sent off to the sawmill. Starting in the early 1950s, conservationists led a charge to prevent further logging. The U.S. Congress established Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976 to preserve an “outstanding example of a near-virgin southern hardwood forest.” This was the first step in Congaree’s journey to becoming a national park.

With its seasonal flooding, Congaree may look like a swamp and feel like one, but it is characterized as a floodplain forest. Some 11,000 acres of hardwood forest thrive on the nutrient-rich alluvial soils where the Congaree and Wateree Rivers merge and frequently flood.

And what of the park’s name? It refers to the native inhabitants who lived along the Congaree River. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Congaree were sold as slaves, fell victim to disease (smallpox) brought by Europeans, and were killed fighting in wars with British colonists and other native peoples.

During the Revolutionary War, deep southern woods such as Congaree earned stealthy General Francis Marion the nickname “Swamp Fox.” The wilderness provided him and his men a strategic and safe haven from which to outwit British troops.

► HOW TO VISIT

Allow a full day for hiking—and an extra day if you want to fish or paddle. Leave your car at the parking lot; there are no roadways within the park. Named for the South Carolina outdoorsman and newspaper editor who kicked off the drive to save Congaree in the early 1950s, the Harry Hampton Visitor Center is the park’s gateway. Inside, a video and exhibits reveal the history and ecology of the park.

A synthetic bald cypress holds court in the exhibit hall, soaring through the ceiling and flaring 14 feet wide, with a hollow base for kids to explore. A framed map illustrated by conservationist John Cely chronicles the lay of the land in meticulous detail. (Maps are available for sale.)

From the visitor center, more than 20 miles of established hiking trails issue from the Boardwalk Trail, a wheelchair- and stroller-friendly loop that links some of the park’s most impressive loblolly pines and hardwoods.

Other trails that branch off from the boardwalk include the Weston Lake Loop (4.4 miles), Oakridge Trail (6.6 miles), River Trail (10 miles), and the more remote Kingsnake Trail (11.7 miles). The flat terrain makes miles pass quickly.

Anglers cast for bass and yellow perch in Weston Lake, while paddlers explore the park on the marked Cedar Creek Canoe Trail or the Congaree River Blue Trail, a 50-mile paddling trail. Whether by land or water vessel, exploration of Congaree depends entirely on the water levels, which can fluctuate by 10 or more feet throughout the year.

A boardwalk through the woods

Boardwalk Loop

This 2.4-mile loop begins on a short boardwalk that connects the visitor center to the Low Boardwalk (1.1 miles), which rests on the forest floor. As the path crosses a primeval swampy flat, upland pines and hardwoods transition to the old-growth loblolly pines and mixed hardwoods of the swamp.

On this walk, visitors see water tupelos, with their smooth, swollen bases, and bald cypress trees, with fluted trunks surrounded by protruding knees. Wild grapevines drape across the path and hug the trees, many of which are covered with Spanish moss and poison ivy. Congaree’s most iconic photographs are taken along this mesmerizing stretch of boardwalk. A self-guided brochure available at the visitor center interprets numbered sites along the route, including a moonshine still.

On this loop it’s easy to understand why the park has picked up nicknames such as “Redwoods of the East” and “Home of Champions.” The 130-foot-high tree canopy of massive oaks, cypress, tupelos, and more is impressive. Indeed, this is one of the world’s tallest forests.

Among Congaree’s champion trees is a loblolly pine that’s as tall as a 17-story high-rise; its girth is 15 feet. There’s also the tallest recorded standing sweetgum, cherrybark oak, American elm, swamp chestnut oak, overcup oak, common persimmon, and laurel oak trees. According to one contemporary biologist, Congaree harbors “acre for acre, more record trees than any other place.”

But a walk through Congaree National Park is about so much more than the trees. As an international biosphere reserve and federally designated Wilderness area, Congaree supports a complex ecosystem. The daytime sounds of songbirds and woodpeckers give way to the nighttime screeches of owls and the distant squeals and grunts of wild boars.

Congaree floods several times each year, typically in winter and early spring. Floodwaters frequently cover nearly 80 percent of the sprawling parkland, sometimes submerging the wooden walkways.

Sweet gums, cherrybark oaks, water oaks, and hollies thrive in the higher, drier soil to the west. Cypresses, water tupelos, red maples, and water ashes soak up the lowlands’ standing water.

Some 159 types of beetles dive, burrow, and scavenge in these waters, which also teem with bass, sunfish, perch, catfish, crayfish, and snails. Congaree is also a breeding ground for 21 kinds of mosquitoes, which may feel like a conservative count during a muggy summer day. Also crawling and slithering through the park are 20 snake species, from brown water snakes to copperheads, as well as box and snapping turtles, several species of salamanders, and a disharmonious population of frogs and toads.

At Weston Lake, the Low Boardwalk connects to the 0.7-mile Elevated Boardwalk, lofted some eight feet above ground as it courses through bottomland hardwoods and upland pines. Every four or five years, floodwaters cover the walkway, and storm damage sometimes renders this segment of the park off limits. In 1989, Hurricane Hugo made a major mark here, striking gaps in the tree canopy; this portion of the park now provides a glimpse into forest regeneration.

Elsewhere in the Park

Beyond the boardwalks, an easy-to-follow network of numbered dirt trails delves deeper into old-growth forest. Connected to the boardwalk, Weston Lake Loop (4.4 miles) traces the edge of the oxbow lake, actually a channel of the Congaree River. The trail follows a channel of cypress and tupelo trees down to Cedar Creek, the park’s largest creek. It is a nesting grounds for great blue herons and kingfishers. River otters frolic in the dark waters of Weston Lake, and an observation deck is equipped with benches that allow you to take advantage of a lake view that just might reward you with an alligator sighting.

A popular choice for those in search of a moderate hike is the Oakridge Trail (6.6 miles), which connects to the Weston Lake Loop and is named for the large oaks that populate the old-growth forest. The trail crosses several guts that bring floodwaters in and out of the park.

The River Trail (10 miles), which branches off from the Western Lake Loop, is the only hiking trail that takes in the Congaree River, the area’s lifeblood. A trip through this section of the park is a walk through ecological succession.

The vegetation varies dramatically from west to east. A cypress pond on the north side of the trail appears cast in a sepia tone, with a lush jungle of vines. At the farthest point, where the trail meets the river, hikers can walk onto an exposed sandbar when waters are low.

As the most remote hike in Congaree National Park, the out-and-back Kingsnake Trail (11.1 miles), accessed from the Weston Lake Loop (after crossing Cedar Creek), is favored for its bird-watching and wildlife-spotting opportunities. White-tailed deer, marsh rabbits, opossums, and raccoons scamper in this backcountry where giant cherrybark oaks line the trail. The final 1.2 miles before hikers turn back follows an old logging road to a canoe put-in spot and parking area along Cedar Creek.

On the other side of the visitor center, the Bluff Trail makes a 0.7-mile arc north along a slight rise on the edge of the floodplain. The trail, which passes through a young forest of primarily loblolly pines and hardwoods, provides access to a primitive campground, after-hours parking area, and the boardwalk.

More Highlights

To see many of Congaree’s state and national champion trees, visitors are required to leave the comfort of the marked trails—and make sure to bring along a good compass. Throughout the year, park rangers lead GPS-enhanced hikes devoted to seeing these big trees. Other free park experiences include walks that focus on bird-watching, history, the skulls and furs of resident mammals, and examples of ecological adaptations (see here).

Visitors can also join an annual Christmas bird count or sign up for occasional guided canoe tours. Any day of the year when water levels are favorable, the park’s waterways are open to paddlers who bring their own canoes or kayaks (available for rent in nearby Columbia). Call the park visitor center ahead of time to get information on water levels.

Though mosquitoes, wasps, spiders, and snakes lurk around its brown waters, Cedar Creek provides paddlers a rare stillness that could well be described as transcendent.

Information

|

How to Get There From Columbia, SC (about 20 miles north), take US 48. From Charleston (about 115 miles south), take I-26 West to I-77 North. From Charlotte, NC (about 110 miles north), take I-77 South. All routes turn onto S.C. 48/Bluff Road; follow Old Bluff Road; park signs lead the rest of the way. Visitor Centers The Harry Hampton Visitor Center is open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Tues. through Sat. Restrooms and brochures are available around the clock. Upon arrival, check the mosquito meter over the restrooms at the visitor center. Rankings go from “all clear” to “war zone.” Headquartered at Congaree is the Old-Growth Bottomland Forest Research and Education Center, which focuses on riverine and forested landscapes across the Southeast. |

When to Go Most pleasant is spring and fall, which coincide with bird migration seasons. During winter, bare trees afford longer views. Summer is often hot and humid; the tree canopy lends a slight cooling effect. Headquarters 100 National Park Rd. Camping A free permit is required and campers self-register at one of two primitive campgrounds—Longleaf (14 sites) and Bluff (6 sites). Limited backcountry camping. Lodging There is no lodging within Congaree National Park. Hotels are plentiful in Columbia, SC (columbiacvb.com). |

Fort Jefferson

Florida

Established October 26, 1992

64,700 acres

One of America’s most unusual and remote national parks, Dry Tortugas National Park is located 68 miles west of Key West, Florida, in the Gulf of Mexico. Though it encompasses 101 square miles, more than 99 percent of the park surface area is actually the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Seven tiny islands (or six or five, depending on wave action, tides, and hurricane activity) make up the park’s land area. Just getting to the park provides visitors with a feeling of accomplishment: The only way to reach it is by boat or seaplane.

So what’s the attraction? Crystal-clear water abounding in healthy coral reefs and marine life, for one thing. Vast flocks of seabirds in nesting season, spring and fall, for another.

Most significant, though, is Fort Jefferson, the largest all-masonry fort in the United States. The 19th-century fortification rises on one of the park’s tiny islands, Garden Key, and stands as an awe-inspiring example of sweeping military architecture. Its history is as unique as its glorious mid-water setting.

Tortugas is Spanish for “turtles.” Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon came upon these specks of land in 1513 as he was sailing around Florida. He named them for the sea turtles found in the gulf. Sailors, including pirates, used the turtles as food and also took huge quantities of eggs from colonies of terns and other birds. The word “dry” was added to the name as a warning to sailors running low on freshwater that they would find none hereabouts.

The United States took control of the Dry Tortugas when it acquired Florida from Spain in 1822. A lighthouse was built on Garden Key, the largest of the islands, in 1825, to guide ships through the maze of reefs and shoals. (A taller lighthouse was constructed on nearby Loggerhead Key in 1857.) In 1846, the U.S. government began construction of a fort on Garden Key, intending it as a base from which to control ships trying to enter the Gulf of Mexico.

The fort was huge, with room for 1,500 soldiers and the capability to withstand a one-year siege. Construction continued through the Civil War until the U.S. Army abandoned the fort in 1874. Though some 16 million bricks had been assembled for its formidable walls, the fort was never officially finished. Despite its eight-foot-thick walls and sheer sweeping proportions, it had been made vulnerable by advances in artillery.

In addition, the structure had settled into the fine sand more than had been expected, and there were fears that adding more bricks and heavy cannons would cause the mammoth structure to sink.

Was all the effort wasted? Not really. Even though its cannons never fired a shot in conflict, its mere presence helped prevent foreign aggression.

During the Civil War and for nearly a decade after, Fort Jefferson served as a military prison. Its most famous prisoner was Dr. Samuel Mudd, who set the broken leg of John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln. Although Mudd said he had no idea who Booth was when he performed the work, he was convicted of conspiracy and sent to the Dry Tortugas in 1865. Mudd was pardoned in 1869, in part because he had saved many lives during an epidemic of yellow fever at the fort in 1867.

Fort Jefferson was used sporadically for other purposes over the years, including as a refuge to protect nesting birds. In 1935 President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared Dry Tortugas a national monument, and the area was designated a national park 57 years later. Today the most enthusiastic visitors are history buffs, snorkelers, and bird-watchers.

► HOW TO VISIT

Most visitors are day-trippers to main island Garden Key, on either a half-day or full-day seaplane trip or a full-day ferry trip. On a half-day trip (2.5 hours on the island) you have enough time for a quick tour of Fort Jefferson and a quick snorkel around the moat wall, although it might be more satisfying to choose one or the other.

On a longer visit, you can leisurely tour the fort, walking around the terreplein (the “roof”) and the surrounding moat wall. You can do some snorkeling and perhaps visit Bush Key (unless it’s off-limits because of bird nesting, in spring and fall).

If possible, consider an overnight at a very basic campsite (fee). You must bring all your supplies, including drinking water, to the site, but the solitude and chance to fully explore Garden Key offer a fine reward for the effort.

Fort Jefferson’s moat

Garden Key

From the beach where seaplanes land or the dock where the ferry ties up, cross the bridge over the moat that surrounds Fort Jefferson and walk through the sally port (entrance). No doubt you’ll want to simply pause for a few moments to marvel at the huge structure’s immense interior parade ground.

Imagine the scene in the 1860s, when the wife of a surgeon stationed here wrote, “We numbered at that time about four hundred, and represented a busy little town. The fort at night was brilliant with lights, and the place was active with the bustle of many people.”

The nearby visitor center offers a video presentation and exhibits that include historic artifacts. You can take a self-guided tour of the fort; interpretive signs are well placed around its grounds and halls.

The ferry operator offers a guided tour for passengers. Be sure to visit the bastion (the fort’s projecting corner structure) opposite the sally port to see the fort bakery and the chapel. The ceiling of the latter features brickwork so graceful that it draws appreciation even from modern brickmasons. Look closely to find the name of the mason, Jno [John] Nolan, and the date, 1859, when the ceiling was completed.

Climb the stairs leading to the terreplein, as the top of the fort is called, to see restored cannons and enjoy fabulous views of Garden Key, the moat, Bush Key, Loggerhead Key, and the gloriously blue surrounding sea. Take note of the unusual rooftop lighthouse, which was built in 1876 of metal rather than brick.

You can also walk all the way around the fort on the wall that encloses the moat. (Moon jellyfish, barracuda, butterflyfish, grouper, tarpon, and many other sea creatures flourish in these waters.)

Additional Experiences

Snorkeling is usually good around the pilings of the Garden Key’s old docks, especially directly along the fort’s brick moat wall. (Snorkeling is not allowed in the moat itself.) The park has designated a self-guided snorkel route with underwater signs along a portion of the moat wall.

Those who can access nearby Loggerhead Key will find great snorkeling on what’s called the “windjammer wreck,” a sunken steel-hulled sailing ship just south of the island. (There are around 200 wrecks and other remains of “maritime mishaps” in Dry Tortugas waters.) Best time for snorkeling and scuba diving is May through September.

In late March and April, Fort Jef-ferson is filled with bird-watchers who come to experience a grand spectacle. Birds migrating north across the Caribbean Sea or the Gulf of Mexico spot Garden Key and then drop in for a rest. At times, every tree and shrub in the parade ground as well as along the fort walls seems to be covered in birds. Flying in are thrushes, warblers, buntings, orioles, and other species of migrating birds.

From spring through summer, thousands of sooty terns and brown noddies (also a type of tern) nest on Bush Key, adjacent to Garden Key. Visiting Bush Key is prohibited during the nesting season to protect the breeding colonies.

Other seabirds can be seen with some regularity around Garden Key; look out for magnificent frigatebirds, brown pelicans, and brown and masked boobies.

Information

|

How to Get There Unless you have your own boat, transportation to Garden Key is by concession-operated seaplane (keywestseaplanecharters.com; 305-293-9300) or ferry from Key West (drytortugas.com; 800-634-0939). Private charter boats can be booked in Key West. When to Go The park can be visited year-round. Nov. through April can see cooler temperatures and rough seas with poor visibility for snorkeling and diving. May through Oct. brings calmer water and hot weather. Hurricanes, though rare, can strike June through Nov. Lodging There is no lodging in the park other than the campground sites. Lodging is plentiful in Key West (keywestchamber.org; 305-294-2587). |

Visitor Centers There is a small visitor center within Fort Jefferson. Information is also available at the Florida Keys Eco-Discovery Center (floridakeys.noaa.gov; 305-809-4750), where a national park ranger is sometimes on duty. Headquarters P.O. Box 6208 Camping Primitive camping (10 sites) is allowed on the small beach at Garden Key. The site has grills, picnic tables, and toilets. Campers must be completely self-sufficient; water, food, shower facilities, and supplies are not available at the park. All trash must be packed out. |

Canoeing Nine Mile Pond

Florida

Established December 6, 1947

1,500,000 acres

Unlike many western parks with their scenic mountains and canyons, Everglades National Park was set aside to preserve an ecosystem comprising a web of animals and plants found nowhere else. The largest wilderness in the eastern United States, Everglades shelters the endangered manatee, the Florida panther, the threatened crocodile, and others.

Drive to Everglades National Park from Florida City, along Fla. 9336, as most visitors do, and get a graphic lesson in conservation along the way. From residential and commercial areas, the highway passes by fields of squash, cucumbers, tomatoes, and strawberries, crossing canals that are part of south Florida’s complex water management program.

The park welcome sign marks a sudden and stark change in the environment, with a succession of natural habitats lying to the west. The 38-mile main park road winds through subtropical hardwood hammocks, pinelands, groves of bald cypress, mangrove forest, and the great “River of Grass,” the sheet of fresh water that originally flowed from the southern shores of Lake Okeechobee through sawgrass across central Florida and out to Florida Bay.

As expansive as the park is, it represents only about one-fifth of the original Everglades ecosystem. Much of the rest has been destroyed or greatly altered for agriculture, urban and suburban growth, and water supply for some six million area residents. People need places to live, food, and water, but the development of southern Florida has come at a great price.

Once, water flowed seasonally from the headwaters of the Kissimmee River, 200 miles north, down through Lake Okeechobee and the greater Everglades, continuing to Florida Bay. Water-management systems designed to protect from flooding during hurricanes disrupted this eons-old pattern, resulting in the degradation of large areas of natural landscape and the decline of wildlife populations. In addition, changes in water flow have threatened the underground aquifer that provides drinking water for Miami and other cities and towns. Concern over these issues led to the massive Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), a decades-long, multibillion-dollar project to address water problems over an 18,000-square-mile area commonly called “the Everglades.”

CERP has given new hope to conservationists and planners who have long worked to preserve the Everglades and protect the natural resources of the national park. Water flow has been improved, and there are signs that populations of wading birds such as wood storks are making a comeback. In 2014 the species was upgraded from endangered to threatened.

There are new threats to the greater Everglades ecosystem in the form of introduced non-native species of plants and animals. The Brazilian pepper tree, for instance, has taken over large areas to the exclusion of native vegetation, and an influx of huge, predatory Burmese pythons has caused a dismaying loss of raccoons, rabbits, and foxes. Oscars, tilapia, and other alien fish displace native species in many areas.

Despite problems, the park remains one of America’s great nature experiences. From crocodiles to butterflies, palms to orchids, the subtropical Everglades environment offers rewards unique in North America.

Visitors explore on foot, by bicycle, or via canoe or kayak. Also available are guided tram and boat tours. The park’s vastness may tempt you to rush through in an attempt to see as much as you can. Resist the urge.

Most visitors arrive sometime during December to April, when heat, humidity, and insect activity are down. Birds, alligators, and other animals are concentrated in smaller, dry-season wetlands and thus are easier to see.

Despite its huge size, the park has only three main hubs for visitation, and two of them have limited activities. If you have only a short time, you may need to choose one area to explore. The best one-day tour begins at the Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center, west of Homestead, and follows the main park road to Flamingo, where you’ll find another visitor center and a roster of ranger-led activities.

Everglades National Park is a little more subtle than most parks. To get a sense of it takes time. Go to the park at dawn or stay until dusk to enjoy the best wildlife activity. Stop for a while on a quiet trail or backcountry waterway, watching and listening.

Ranger-led programs reveal aspects of life here that might otherwise be overlooked. Learn about this rich and intricate ecosystem and you’ll understand why the park has been officially designated an international biosphere reserve, a World Heritage site, and a wetland of international importance. Everglades National Park has taken its place among the planet’s greatest natural areas.

Stop along the way to walk one or more of the interpretive trails. The Anhinga Trail at Royal Palm is deservedly famous for wildlife viewing. With more time, take a boat tour at Flamingo or rent a kayak and paddle around Florida Bay.

If you have more time, consider a tram tour or bicycle ride through Shark Valley, in the northern section of the park (25 miles west of the Florida Turnpike in Miami, on US 41 on the Tamiami Trail). Activities offered at the Gulf Coast Visitor Center in Everglades City, in the far western part of the park, focus on the water, with guided boat tours and canoe and kayak rental for day trips or camping out in the Ten Thousand Islands area.

Ten Thousand Islands mangrove trees

Eastern Entrance to Flamingo

The Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center provides the usual amenities, including interpretive exhibits, an information desk, a bookstore, and an introductory video. The hiking trails that issue from here offer a great way to see the park but lack the variety found at most parks. Most of the more varied backcountry is accessible only by water.

The main park road travels 38 miles to the Flamingo area on Florida Bay, providing access to several hiking trails along the way, as well as put-in spots for canoe/kayak trails. The road is out-and-back, not a loop.

Nearly everyone turns off the main park road to visit the Royal Palm area, and for good reason. The 0.8-mile Anhinga Trail, part paved and part boardwalk, offers some of the best wildlife viewing in the park. Wading birds such as herons and egrets (and, yes, anhingas) feed in wetlands where alligators and turtles swim. Wildlife here is so accustomed to humans that it’s easy to take close-up photos. Rangers lead regular nature walks here, well worth joining.

The adjacent 0.4-mile Gumbo Limbo Trail winds through a hardwood hammock—the local name for a dense woodland growing on a natural rise in the surrounding marsh. The trail passes among trees such as royal palm, gumbo limbo (with its distinctive peeling red bark), mahogany, and live-oak. Ferns and strangler figs, whose exposed roots dangle after seedlings take hold in tree branches, contribute to the lushness of the vegetation. Black-and-yellow zebra longwing butterflies flit gracefully through the undergrowth, and bird-watching can be excellent.

Though not as well known as some other ecosystems, slash pine woodland is one of the most endangered environments in southern Florida. Slash pine forest is found on higher ground that’s easy to clear and develop; as a result, only 2 percent of the habitat remains standing.

A few miles farther down the main park road, the 0.4-mile Pinelands Trail passes among bald cypress trees hardly taller than a person. These are mature trees, stunted in their growth by shallow, nutrient-poor soil. Here and there stand “domes” of tall bald cypresses crowded into areas with more water. These are favorite destinations for the activity known as “slough slogs.” Join in by donning old sneakers and tromping out through the wet grassland to enjoy the magical habitat, teeming with life—right at your feet. If you’re at all apprehensive about setting out to do this on your own, check for regularly scheduled ranger-led slough slogs.

Pa-hay-okee Overlook and Mahogany Hammock make rewarding stops along the main park road. The former is a raised viewpoint over the great River of Grass in its “vast glittering openness,” as pioneer Everglades conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas described it. At the latter, a boardwalk passes through a dense hardwood hammock where palms, ferns, and epiphytes (“air plants” growing on tree limbs) give visitors the feeling they’ve been transported to a place deep in the tropics.

The road passes several spots for launching canoes and kayaks, offering the opportunity for paddling trips both short and overnight. (Bring your own boat or rent one outside the park or at Flamingo; check with the concessioner there, 239-695-3101.)

The 5-mile loop at Nine Mile Pond combines open marsh and mangrove forest, while the Hells Bay Canoe Trail passes through mangrove tunnels and open ponds en route to camping spots (permit required). For other boating routes, pick up a trail guide at the Flamingo Visitor Center.

The Flamingo area offers several hiking possibilities, although heat, humidity, and especially mosquitoes can make this activity uncomfortable from about May through November.

At West Lake a short boardwalk winds through the stiltlike roots of a mangrove forest to a viewpoint of the bay. The Snake Bight Trail, a 1.6-mile hike from the road to a bight (small bay) on Florida Bay, is famous as one of the best bird-watching walks in southern Florida. Look for rarities such as mangrove cuckoo and white-crowned pigeon; at the bay you could be lucky and see a small flock of flamingos. (It is very easy to confuse flamingos with the more common roseate spoonbill, another large pink bird.)

Eco Pond offers another of the park’s excellent short nature walks, a 0.5-mile loop circling a small pond where waterbirds roost and butterflies abound.

Flamingo, with a small store and a campground, marks the end of the park’s main road, with island-studded Florida Bay stretching to the south and the Florida Keys reaching beyond the horizon. Rangers at the visitor center can offer assistance and advice. You can rent canoes and kayaks here for a spin around Florida Bay. Stick close to shore if you’re unsure of your abilities. Landing is restricted on many of the islands; you can come to shore on Bradley Key.

This area of the park is the most likely place to spot a crocodile, the saltwater relative of the far more abundant freshwater alligator. The Everglades is the only place in the world where alligators and crocodiles are found together, where the salt water and fresh water meet. A croc sighting is possible along Buttonwood Canal as well as on a narrated boat tour (239-695-3101).

Snowy egret

US 41, also known as the Tamiami Trail, runs west from Miami to Naples. About 20 miles of its length forms a portion of the northern boundary of the park. The Tamiami Trail provides access to two park gateways.

About 18 miles west of Miami is the entrance to the Shark Valley Visitor Center. The “valley” here is actually that of the Shark River Slough, one of the major slow-flowing sheets of water that comprise the Everglades “river of grass.” The water here, moving at speeds that average about two feet a minute, eventually enters the Gulf of Mexico, some 40 miles to the southwest.

The main attraction at Shark Valley is a 15-mile loop Tram Road, which heads into the heart of the Everglades, mostly through sawgrass marsh. (Touch the edge of a leaf and you’ll quickly understand why it’s called “saw.”) The tram road was in part built by a company exploring for oil before the national park was established. It’s closed to private vehicles but can be traveled on a guided tram tour, by bicycle, or on foot.

The tram ride makes a fine introduction to the Everglades ecosystem, as trained narrators describe sites along the way. They point out, for example, how a rise or fall of just a few inches in elevation can make a difference in the vegetation, with hardwood hammocks on higher ground and cypress swamp in depressions.

Alligators are commonly seen along the road, with a wide variety of wading birds, turtles, and the occasional white-tailed deer or snake.

A highlight might be a sighting of the federally endangered snail kite, a hawk that feeds almost exclusively on large apple snails. Tours stop for a break at a 65-foot-high observation tower, with a rare, elevated 360-degree panorama of the Everglades.

Walking or bicycling the Shark Valley road is a great way to feel a part of this vast marsh environment. Bike rentals are available at the visitor center. Remember, as always, to maintain a safe distance from wildlife, including, of course, alligators. (Though they seem sluggish, they can move quickly on land for short distances.)

Shark Valley has two short trails, the 0.5-mile, wheelchair-accessible Bobcat Boardwalk and the 0.25-mile Otter Cave Hammock Trail. Both provide welcome shade on sunny days.

Gulf Coast Area

For a real “old Florida” feel, take Fla. 29 south from the Tamiami Trail to the town of Everglades City and the park’s Gulf Coast Visitor Center. This facility is the gateway to the Ten Thousand Islands region of the Gulf Coast. Here, mangrove islands and tunnel-like passageways create a maze where land meets sea.

Activities in this area focus on the water; exploration can be rewarding for experienced boaters but sometimes daunting for beginners. Here, it’s important to know your paddling ability and get advice from rangers before choosing an adventure.

Those who want to venture out on their own can bring a canoe or kayak or rent one at Everglades City. Options range from a quick paddle around the islands near the dock to a multiday camping trip into the wilderness.

The 5-mile round trip to Sandfly Island is popular and not too difficult, especially if you time it to take advantage of outgoing and incoming tides. Other day trips include the Halfway Creek, Loop, and Turner River water trails. These can take from four to eight hours.

The ultimate adventure for experienced boaters is the challenging 99-mile-long Wilderness Waterway, which follows a winding route along the coastline, all the way from Everglades City to Flamingo. Those who paddle the entire length usually allow at least eight days for the trip, camping on land, on the beach, and on elevated platforms called “chickees.” Motorized boats can make the trip in one long day.

The most popular activity, however, requires no boating skill: concessioner-operated guided boat tours leave from the dock at the visitor center. One of the two tours travels out to the Gulf of Mexico, winding among islands and offering the chance to see bottlenose dolphins, manatees, bald eagles, ospreys, brown pelicans, and more. The other tour uses a smaller boat to travel among inland mangrove habitat, with common sightings of alligators, small mammals, and a variety of waterbirds.

Information

|

How to Get There To reach the main park entrance from Miami, FL (about 50 miles north), take Fla. 821 (Florida’s Turnpike) south to Florida City and then go west on Fla. 9336 (Palm Dr.). The Shark Valley area is on US 41 about 18 miles west of Miami, and the Gulf Coast visitor center is another 40 miles west; from there, head south 4 miles on Fla. 29. Visitor Centers Three visitor centers (Ernest F. Coe in the east, Shark Valley in the north, and Gulf Coast in the west) are open daily year-round. The Flamingo Visitor Center (southern tip of the park) is staffed intermittently mid-April to mid-Nov. but fully operational the rest of the year. Headquarters

40001 State Road 9336 |

When to Go There are two seasons: a wet summer and a dry winter. May through Nov. the weather is hot and humid; mosquitoes can be extremely bothersome. Ranger-led tours and other activities are limited in summer. Dry-season visits are generally more pleasant (though more crowded), with a March through April visit usually best. Camping Long Pine Key (108 sites) and Flamingo campgrounds (274 sites) are reached via the main park road (recreation.gov; 877-444-6777). The park also offers primitive backcountry camping (permit required). Most backcountry sites can be reached only by boat, but a few are accessible to hikers. Lodging Lodging is plentiful in Homestead and Florida City, just east. Lodging also can be found in Everglades City, just northwest. Tropical Everglades Visitor Association (tropicaleverglades.com; 305-245-9180). |

The Smoky Mountains

North Carolina & Tennessee

Established June 15, 1934

522,000 acres

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated Great Smoky Mountains National Park, he gave his speech with one foot in North Carolina and the other in Tennessee. It was a fitting gesture given the decades-long cooperative effort to establish a park in the southern Appalachians, an endeavor that involved not just officials in the two states but private groups and even schoolchildren, who pledged pennies to help fund land purchases.

Great Smoky Mountains now ranks as America’s most visited national park. It delights millions of annual visitors who come for its ancient mountains, lush forests, diverse flora and fauna, dozens of waterfalls, and engaging history. As part of its overall interpretive mission, the park emphasizes three major themes: biological diversity, the continuum of human presence in the southern Appalachians, and scenic beauty.

The park’s 814 square miles represent the largest federally protected upland area east of the Mississippi River. The elevation range of 875 to 6,643 feet within Great Smoky Mountains creates widely different life zones. Moving from the park’s lowest to highest points is, in effect, like traveling from the Southeast to Maine—from post oaks and wild turkeys to Fraser firs and ravens. Fueled by up to 85 inches of rainfall annually, the park ecosystem boasts a stunning array of plants and animals.

In addition to the ongoing heritage of Cherokee Indians in and near the park, Great Smoky Mountains preserves a nationally significant collection of pioneer-era log buildings as well as structures built during the Depression. Much of the original development of facilities and restoration of early settlers’ buildings was carried out by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), an agency created to provide work and wages for young men during very challenging economic times.

► HOW TO VISIT

If it is beauty you seek on a one-day visit, a drive up Newfound Gap Road, a hike to Ramsey Cascades, or a trip around Cades Cave Loop Road are certain to reveal varied aspects of the park’s scenic splendor, with vast views over rolling ridges to old-growth forest to the pastoral landscapes shaped by settlers’ farms.

First-timers should experience the park’s most popular destinations. Newfound Gap Road (US 441) bisects the park, climbing over a ridge of the Appalachians, and Cades Cove, a valley, once was home to a thriving farming community.

If you have more time, less-traveled roads and hiking trails—including many easy walkways—allow you to experience the subtle features that are the essence of the park: the massive trunks of a century-old tulip trees; the fluting songs of wood thrushes; the tangy scent of a spruce forest.

Indeed, you have to get off the road to really get to know and appreciate the park. There is a wealth of opportunities for intimate discovery.

Forests in the park have suffered in recent years from non-native invasive insects, which have killed firs and hemlocks, altering the natural functions of ecosystems. Park staffers continue to seek solutions, hoping to help control or at least strike a balance with these alien pests.

Dense forests cloak the Appalachians. The moisture they release as a result of evaporation combined with high rainfall often creates fog—the “smoky” mist that gives this mountain range and the park their names.

Winding for 31 miles between the gateway towns of Gatlinburg, Tennessee, and Cherokee, North Carolina, this beautiful drive connects the park’s two main visitor centers: Sugarlands and Oconaluftee. Along the way it passes picnic areas, trailheads, and scenic overlooks as it climbs almost 4,000 feet before descending.

At the Chimneys Picnic Area (Mile 7) you’ll find the Cove Hardwood Nature Trail, one of the park’s best short walks, with old-growth forest. The 2-mile Chimney Tops trail (Mile 9) and the 2.3-mile Alum Cave (Mile 15), both strenuous, also are popular trails here. The former leads to rocky summits with great views; the latter is the shortest route to 6,593-foot Mount Le Conte, third highest peak in the park and the site of the park’s only commercial lodging (see here).

At Mile 15 is 5,048-foot Newfound Gap, the road’s crest. Before this road was built in the 1930s, people used a wagon road at nearby Indian Gap to cross the mountains. The Appalachian Trail intersects the road here, and many people like to walk a bit of this historic route that runs some 2,180 miles from Georgia to Maine.

The 4-mile, moderately strenuous hike to Charlies Bunion (a rocky knob with fine vistas) follows the Appalachian Trail and the Tennessee–North Carolina state line.

Nearby is the 8-mile road to famed Clingmans Dome, usually closed from December through March. With an observation tower reached by a 0.5-mile paved trail, the site offers a grand panorama of the Appalachians on clear days. The “view” is just gray clouds when fog shrouds the peaks at this 6,643-foot elevation, the highest in the Smokies.

Temperatures here average more than 20°F cooler than at Gatlinburg. Spruce-fir forest, red squirrels, and dark-eyed juncos make the environment seem more like Canada than the Southeast.

As the Newfound Gap Road descends, it passes overlooks with especially outstanding views of the Oconaluftee River and Deep Creek valleys. At Kephart Prong (Mile 23) and Smokemont Campground (Mile 27), trails traverse forests regrown after intensive logging in the early 20th century.

Stop at Mingus Mill (Mile 30) to see a restored 1886 grist mill that uses a turbine rather than a waterwheel to turn the millstones—advanced technology for its day. A miller is on site to explain the operation.

A half-mile farther on, the Oconaluftee Visitor Center offers maps, books, brochures, and advice from rangers. It also includes the small but excellent Cultural History Museum that highlights the relationship between people and the land, from the native Cherokees and their forced removal in the 19th century up through the establishment of the national park.

Just outside, the open-air Mountain Farm Museum showcases a collection of historic log structures, including a farmhouse, huge barn, smokehouse, blacksmith shop, and corn crib. The easy, 1.5-mile Oconaluftee River Trail features displays highlighting Native American history.

Visitors along Deep Creek Trail

Located in the western part of the Tennessee side of the park, this broad, 2,400-acre valley was home to more than 130 families in the mid-19th century. Many of their homes, barns, churches, and other buildings still dot the landscape, adding to the appeal of this portion of the park. What once were farm fields (largely corn) are now open grasslands, a boon for wildlife watchers.

So popular is Cades Cove that in summer and the “leaf-peeping” foliage season of October, it can take hours to drive the 11-mile one-way loop road. A “bear jam” could cause a lengthy traffic backup. Visitors can help ease congestion by using pull-offs to view wildlife. Consider walking or biking the loop when it’s closed to motor vehicles, Wednesday and Saturday mornings from early May to late September.

Among Cades Cove highlights is the 1820s John Oliver Place, the oldest log house in the area, built of hand-hewn logs and split-wood shingles. About a mile farther along is the turn to the Primitive Baptist Church, built in 1887 to replace an earlier log cabin.

About halfway around the loop is the short trail to the Elijah Oliver Place, a homestead that includes a log house, smokehouse, corn crib, spring house, and chicken coop. Note the “stranger room” added to the porch to accommodate visitors.

A 2.5-mile trail leads to striking Abrams Falls—certainly not the tallest waterfall in the park but the largest by water volume. Carry plenty of drinking water, wear sturdy shoes, and take your time on this moderately strenuous hike.

The Cable Mill area is a must stop, encompassing a small visitor center, an operating water-powered grist mill, a striking “cantilever” barn (with a large roof overhang), a sorghum mill, an 1887 frame house, as well as several other buildings.

The last portion of the loop passes several historic structures, including the Carter Shields Cabin, one of the most captivating photo opportunities in the park, especially in spring when the dogwoods are in full bloom.

Elsewhere in the Park

The Roaring Fork Motor Nature Trail, a 6-mile loop reached from downtown Gatlinburg (turn south at traffic light 8), provides a wonderful way for people with limited mobility to experience a Great Smokies forest.

You’ll pass rocky streams and several log cabins and other historic structures, as well as the trailhead for the 1.3-mile walk to Grotto Falls, a waterfall that provides considerable scenic reward for moderate effort.

A few miles east of Gatlinburg, off US 321, a side road follows the Little Pigeon River to the Greenbrier area. Here you’ll find the trailhead for the strenuous 4-mile hike to Ramsey Cascades, at 100 feet high the tallest waterfall in the park. The last two miles of this trail pass through splendid old-growth forest.

A less strenuous option is the nearby 3.6-mile Porters Creek Trail, which heads upstream to an old cemetery, an 1875 barn, and a healthy grove of tall hemlocks. Spring wildflowers are a special seasonal attraction on Porters Creek Trail.

The North Carolina side of the park generally sees fewer crowds than the Tennessee side, and features several appealing destinations in addition to those along Newfound Gap Road. The Deep Creek site near Bryson City offers three waterfalls along a loop hike of just 2.4 miles. Longer jaunts take hikers into some of the park’s old-growth forest, untouched by 20th-century loggers.

Reached by winding mountain roads off either US 276 in North Carolina or Tenn. 32, the Cataloochee area was once home to the largest community in what is now the national park. Families totaling around 1,200 people farmed and raised livestock, and even developed an early tourism industry based on trout fishing. One resident said life here “was more like livin’ in the Garden of Eden than anything else I can think of.”

Today the Big and Little Cata-loochee valleys preserve several historic structures, including houses, barns, churches, and a schoolhouse. Cataloochee increased in popularity after 2001, when elk were reintroduced. It remains an excellent place to spot these animals as well as black bear and deer.

Information

|

How to Get There From Knoxville, TN (about 25 miles north), take I-40 to Tenn. 66, then US 441 to the park’s Gatlinburg entrance. From Asheville, NC (about 40 miles east), take I-40 to US 19, then US 441 to the Cherokee entrance. Less traveled routes include the Foothills Parkway (Exit 443 from I-40), US 321 in Tennessee, and the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina. When to Go The park offers year-round attractions, though the Clingmans Dome Road and some minor unpaved roads are closed in winter. Summer and Oct. weekends are the most crowded times. Winter weather occasionally closes Newfound Gap Road (US 441). Visitor Centers Sugarlands, on US 441 south of Gatlinburg, TN; Oconaluftee, on US 441 north of Cherokee, NC.; Cades Cove, on the scenic loop off Laurel Creek Rd. in the northwestern section of the park. All open year-round. |

Headquarters

107 Park Headquarters Rd. Lodging The only lodging within the park is the historic LeConte Lodge (lecontelodge.com; 865-429-5704), reached by a hike of about 5 miles. Seven cabins, three multiroom lodges, no electricity, shared bathrooms. Hotels are plentiful in Gatlinburg, TN (gatlinburg.com; 865-436-4178 or 800-588-1817), Cherokee, NC (cherokeesmokies.com; 828-788-0034), and other nearby communities. |

A Mammoth Cave lantern tour

Kentucky

Established July 1, 1941

52,830 acres

One of the world’s great natural wonders, Mammoth Cave National Park sits beneath Kentucky hills and hollows. It earned its grandiose designation in the early 19th century, when tourists marveled at the enormity of its underground chambers. With more than 400 miles of mapped passageways, Mammoth Cave National Park encompasses the planet’s longest known cave system, with five levels and caves yet to be discovered.

Some 12 miles of Mammoth Cave are open to the public, with tour routes offering a diversity of experiences, from strolls that focus on spectacular formations to more challenging walks that center on cave history. For the latter, visitors don protective gear and crawl through tight passageways.

Mammoth Cave’s vast rooms and winding tunnels exist today because of a coincidence of geologic events. More than 300 million years ago, what is now central Kentucky was covered by a shallow tropical sea, where organic matter formed layers of limestone hundreds of feet thick. Fifty million years later, a river system deposited sand and mud that transformed to sandstone and shale.

Over time, underground rivers cut passages through the relatively soft limestone. As the water level dropped, the cave rivers sank deeper, exposing higher channels as dry caverns. Meanwhile, the harder overlying sandstone layer served as protection for the cave system, preventing it from eroding and collapsing into sinkholes and valleys.

Cave formations are created when water seeps through limestone, dissolving minerals and redepositing them on passage ceilings, walls, and floors. Mammoth Cave’s sandstone “roof” keeps this process from happening in much of the cave, so visitors who want to enjoy stalactites, stalagmites, columns, draperies, and other subterranean features should study tour descriptions and choose from the cave’s scenic routes.

There’s more to the national park than just the cave, of course. Mammoth Cave’s 82 square miles encompass lush forests that teem with wildlife, as well as 27 miles of the Green River, one of North America’s most biologically diverse waterways. Biking, hiking, horseback riding, boating, and fishing are active options—before or after experiencing the world belowground.

► HOW TO VISIT

Every visit should include at least one cave tour and, if you have more time, exploration above ground. Read descriptions on the park website or speak to a ranger at the visitor center when you arrive to determine which tours (fee) best match your interests and level of fitness. Try to make advance reservations for tours (recreation.gov; 877-444-6777), especially for summer and weekend visits.