Walking through Bryce Canyon along Queens Garden Trail

When explorer John Wesley Powell successfully navigated the Green and Colorado Rivers on his 1869 expedition, he solidified the American fascination with the Wild West. Today many consider the Grand Canyon, core of one of 11 parks in the Southwest, an emblem of American heritage and a natural wonder of the world.

Yet the allure of the Southwest extends far beyond Arizona’s Grand Canyon to ten other national parks. The sandstone spires, hoodoos, and fins of Utah’s Bryce Canyon create a surreal spectacle of color and shape. Eons of wind, rain, and elements have built and broken the swooping arches of Utah’s Arches National Park, and will continue to do so. Millions upon millions of years are quite literally on display in the multicolored sedimentary rock of Utah’s Capitol Reef’s untrammeled canyons.

Ancient humans left an indelible mark on these lands. Ancestral Puebloans inhabited the mesa tops of Colorado’s Mesa Verde for hundreds of years before constructing their famous cliff dwellings, including the 150-room Cliff Palace. The haunting figures of the Great Gallery, a 300-foot panel of rock art found in Utah’s Canyonlands, offer clues to what early life was like in these desert climes.

In even the harshest of Southwest environments, life manages to thrive. In Utah’s most visited and celebrated park, Zion, “hanging gardens” cling precariously to bald-faced rock walls. Likewise, seemingly inhospitable cliffs along Colorado’s Black Canyon of the Gunnison teem with flora and fauna that have adapted to the vertiginous landscape. The wind-snarled bristlecone pines of Nevada’s Great Basin rank among the oldest tree specimens on Earth, a boon for scientists studying tree-ring data. In Arizona’s Saguaro, prickly saguaro cacti can live up to 200 years.

Then there are the long-dead trees of Arizona’s Petrified Forest, which have evolved postmortem. Like a firsthand lesson in cell biology, the plant fossils reveal over 200 million years of chemical reactions that have resulted in a palette of eye-popping colors.

Delicate Arch

Utah

Established November 12, 1971

76,679 acres

As the ancient Romans knew, there’s something commanding about an arch, something that raises us up. Imagine more than 2,000 of them, hewn of stone, defiantly standing in the face of the erosional forces that created them. The 240 square miles of Arches National Park encompass the world’s most concentrated display of these natural formations. While most arches lie hidden in the park’s deepest recesses, several, such as Delicate Arch, have become icons.

Most of the park’s namesake arches are made up of ancient beaches and Sahara-esque sand dunes that edged an inland sea 140 to 180 million years ago. This coral-hued Entrada layer was buried a mile deep by later sediment, whose weight cemented it into sandstone. The 300-million-year-old salt beds below shifted under the growing weight, buckling the Entrada sandstone into long accordionlike joints. After erosion carried away the sediment above, rainwater fell into these joints, widening them until they formed freestanding slabs of stone called fins. Rainwater continues to erode the sandstone, forming cavities in the fins and sometimes resulting in freestanding arches.

Just as arches continue to be created, so they fall, as did Wall Arch, the park’s 12th largest span, in 2008. Landscape Arch is so close to falling that no one is allowed near it. As timeless and enduring as the park appears to be, this is a surprisingly fragile environment.

It doesn’t take much to upset the land’s delicate balance. A misplaced footstep off-trail, where the park’s soil crust is knit in knobby clumps of moss, lichen, and bacteria, can destroy decades of growth, leaving soils vulnerable to erosion.

As this small park receives more than a million visitors each year, its delicate nature is put to the test. A healthy respect for the natural forces at work only enhances appreciation of the park’s awe-inspiring sights.

► HOW TO VISIT

Parking lots often overflow. Visit the most crowded sites—Devils Garden, The Windows, and Delicate Arch—early in the morning or late in the day. If you only have several hours, you can stroll along the 1-mile Park Avenue Trail, stop at Balanced Rock, and walk through some of the park’s largest arches at the Windows.

A half day or longer allows time to add on Landscape Arch in Devils Garden, with time left over for a sunset pilgrimage to Delicate Arch. Depending on park schedules, all-day visitors could get the chance to experience a ranger-led guided walk through Fiery Furnace or the entire Devils Garden Trail.

Arches Scenic Highway

Beginning just past the visitor center, this 18-mile-long paved road strings together the park’s most prominent sights. The road climbs from the floor of Moab Canyon to Devils Garden, passing through the heart of the park, with spur roads leading to The Windows, Wolfe Ranch, and the Delicate Arch area. Numerous pull-offs along the way allow for leisurely viewing of the park’s major features.

Switchbacking up the steep road through the white Navajo and pinkish Entrada sandstone, you’ll top out on a surreal expanse of monolithic buttes, arches, and hoodoos (natural columns of rock).

Your first stop is Park Avenue, a narrow canyon lined with skyscraping fins and spires. Stone monuments Nefertiti, the Three Gossips, and the Organ can be seen along the 1-mile Park Avenue Trail, which slopes down through sage, rice grass, and twisted juniper. If you’re going to hike it, having a driver designated to pick you up at the Courthouse Towers parking area saves having to hike back the way you came, an uphill slog.

Continue, driving across Court-house Wash (the park’s only year-round stream) and past the Petrified Dunes to gravity-defying Balanced Rock, one of the park’s most recognizable sights. A 0.3-mile trail loops around this teardrop knob of Entrada sandstone balanced, at least for now, on a crumbling pedestal.

Turn on the spur road to The Windows, passing the spires and grottoes of the Garden of Eden along the way as you make your way up to Elephant Butte, the park’s highest peak at 5,653 feet.

At The Windows, two trailheads link four of the park’s largest arches, all within sight of each other. One gently sloping trail leads 0.25 miles to twinned Double Arch, the park’s highest arch, with a vertical light opening of 112 feet. The other trail is the park’s busiest thoroughfare: The Windows is a 1-mile gravel loop that takes in Turret Arch, North Window, and South Window. Returning via this primitive trail, you get a backside view of the two Windows framing a nose-shaped rock, aptly called the Spectacles.

From Balanced Rock, head to the Delicate Arch turnoff, a 2.5 mile-long spur road offering two opportunities to see the famous arch. Park at the Delicate Arch trailhead at Wolfe Ranch and hike 1.5 miles to the arch itself. (The hike is strenuous and can take an hour in and another hour back out.) Otherwise, drive another mile and cross, conditions permitting, flash-flood-prone Salt Wash to the Delicate Arch Viewpoint for a view of the arch, a mile away.

Four miles past the Delicate Arch turnoff, the scenic highway passes Fiery Furnace, a reddish pink labyrinth of narrow fins, arches, bridges, and slots that require hikers to squeeze, wriggle, and jump their way through, with no trail or cairns (stone piles) to help guide them. A permit, available at the visitor center, is required.

Unless you know the Furnace well, try to book one of the three-hour tours guided by rangers who point out what could be easily overlooked: hidden arches; potholes teeming with micro-life; and rare canyonlands biscuitroot, which grows only in sandy soil between fins of Entrada sandstone. Check the tour schedule on the park website; you also can ask at the visitor center for guided-tour information.

Four miles farther down the scenic highway from Fiery Furnace lies a short trail to Sand Dune Arch and a half-mile trail across a wildflower-speckled meadow to Broken Arch. These walks, however, are best left for another day if they keep you from driving 4 more miles to the end of the road to hike the 0.75-mile-long trail to Landscape Arch, at 291 feet one of the world’s longest natural spans, a dramatic don’t-miss park sight.

Heading through the park at sunset or during twilight, watch out for the park’s furry residents, inactive during the day and now stirring to life: coyotes, black-tailed jackrabbits, and kangaroo rats.

Hikers at Deadhorse Point

Delicate Arch

The strenuous 1.5-mile-long March to the Arch (the arch formation stands on the edge of natural amphitheater backdropped by La Sal Mountains) should be on everyone’s must-do list. Give yourself two to three hours round-trip. Better yet, plan half a day.

The trail begins at Wolfe Ranch, a shale-chinked cabin built at the turn of the 20th century by a disabled Civil War veteran. It is the park’s only evidence of ongoing human habitation. (Upon first seeing her future home, the war veteran’s daughter broke into tears—and not from joy.)

A signed spur trail loops 100 yards to a Ute petroglyph panel that gives away its age: The etched figures on horseback postdate the Spanish arrival. The trail switchbacks up a steep hillside, then levels out though a field of chert boulders, a crystalline rock from which Native Americans once knapped arrowheads.

Follow the cairns up the shadeless slickrock, through pockets of piñon and juniper, and climb the 200-yard-long ramp that blasted out of a cliff. The sudden, dramatic appearance of Delicate Arch will stop you in your tracks. The 60-foot-high arch of Jurassic-era sandstone is capped by more erosion-resistant rock.

The most popular time to visit Delicate Arch is right before sunset, when the arch performs for the gathered crowd by reflecting the sun’s glow in varied hues. Bring a flashlight or headlamp for the return journey.

If you can time an evening hike to coincide with a full moon, you may have the thrill of seeing the moon rise up over the arch.

Devils Garden Trail

The park’s longest trail, Devils Garden Trail is a 7.2-mile loop that weaves through, around, and atop soaring fins with what might be the world’s largest stockpile of natural arches. (Don’t let the crowded parking area fool you. Many folks are here solely for the stroll to Landscape Arch.) From the trailhead, a groomed trail threads between fins, breaking out at 0.3 miles where a short side trail heads to Tunnel and Pine Tree arches (save these minor spans for the return trip). Pick up the pace another half mile to Landscape Arch, which is doomed to collapse in the near future (as did Wall Arch in 2008; it’s now an unsigned heap of rubble 200 yards farther down the trail). Landscape Arch is a narrow ribbon of stone 306 feet long, seemingly defying gravity as it floats in a graceful span above the dunes. Beyond Landscape Arch, the trail is marked by stacked-stone cairns. (Hikers should not consider creating new cairns, which could confuse others on the trail.)

If time is short, bypass the spur trail to Partition Arch (0.2 mile) in favor of the trail to Navajo Arch (0.3 miles), whose span suggests a cave opening to an inner sanctum domed by sky.

Back on the main trail, you’ll be walking atop a 10-foot-wide vertical slab with 100-foot drop-offs before coming to a short side trail to the Black Arch Overlook, which offers vertiginous views. Though primitive, the trail continues on another mile to Double O Arch, a small arch topped by a much larger one, like a double rainbow caught in stone. Here you have three options: return the way you came; continue another half mile to the 150-foot spire called Dark Angel; or return via the longer Primitive Trail, heading down Fin Canyon, which can add an extra hour of hiking time.

Elsewhere in the Park

Tower Arch, a massive 101-foot-across span wedded to a minaret-like tower, inspired the park’s founding father, Alex Ringhoffer, to lobby for creation of a national monument in 1929. Yet it’s the park’s least visited major attraction, thanks to a remote location reached via 8.3 miles of dirt road up Salt Valley (ask at the visitor center for information on road conditions) and a 1.7-mile-long primitive trail that heads into remote Klondike Bluffs. The trail winds through an intricate landscape of sandstone formations, cresting ridge tops that offer outstanding vistas of Fiery Furnace, La Sal Mountains, and Book Cliffs.

Alongside a trail edged with claret cup cactus and leafless Mormon tea, you will see three soaring sandstone spires, nicknamed the Marching Men.

Perfect for a summer scorcher, the 6.2-mile Courthouse Wash Trail offers a wade-worthy stream under the broad-leafed shade of cottonwood trees. Pack a picnic lunch, park at the bridge along Arches Scenic Highway (11 miles from the visitor center), and head downstream (south) for lunch.

Information

|

How to Get There The park entrance is 5 miles north of Moab on US 191, which continues 25 miles to the Crescent Junction exit of I-70. When to Go Snowfall can glaze the slickrock from late Nov. through Feb., yet trails remain open. Blustery spring storms bring April and May wildflowers, while monsoon thunderstorms moderate scorching summer temps in July and Aug., resulting in a second wildflower bloom in early fall. Visitor Centers The Arches Visitor Center is open every day; hours vary by season. |

Headquarters 2282 SW Resource Blvd. Camping From March through Oct., plan on making reservations to secure a spot at the 50-site Devils Garden Campground. (recreation.com; 877-444-6777 or 518-885-3639). In winter, sites are available on a first-come, first-served basis. Lodging While there are is no lodging in the park, nearby Moab (discovermoab.com) offers a full roster of B&Bs, condo rentals, motels, hotels, and riverside resorts. |

Sheer canyon walls of the South Rim of Black Canyon

Colorado

Established October 21, 1999

30,750 acres

To hear roaring rapids while peering down 2,000 feet into an abyss of dark rock is a weak-in-the-knees experience. From the canyon rim, early settlers claimed you could see “halfway to hell.” Maybe not, but at Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park you will see two billion years of Earth history on a scale that puts human life into humble perspective.

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park protects the most spectacular 14 miles of a 53-mile-long gorge carved by the Gunnison River, whose headwaters lie high in the Rocky Mountains. About two million years ago, after the “Gunny” had washed away the softer volcanic breccia, the river hit the dense basement rock of gneiss and schist. Trapped in a groove of its own making, the river has been carving deeper ever since, especially during the last ice age, when glacier meltwater sliced through the rock, leaving sheer cliffs in its wake.

Still one of the country’s wildest canyons, it shows no evidence of human habitation. Flora and fauna, on the other hand, have adapted well to the vertical geography. Ancient piñon pine groves shade the top, while Douglas fir, aspen, and blue spruce clutch the steep slopes, where “hanging gardens” flourish.

Since the 1970s, when dams were put in place to tame seasonal flooding, cottonwoods, willows, and reedy box elders have taken root along the river bottom. They are having a tough time of it now: The National Park Service won the right to flood the canyon every spring to restore the river to its pre-dam wildness.

And wild it is. Otters play, and legendary trout—rainbow, brown, and native cutthroat—lure fishermen down the steep rocky routes where yellow-bellied marmots bask on ledges. Mule deer are a common sight, elk and reclusive black bears less so. Raptors rule the skies—golden and bald eagles, prairie and peregrine falcons—while other birds keep to the brush. Inadvertently flush one of the park’s blue grouse from the sage flats and you’ll know why it’s called the heart-attack bird.

► HOW TO VISIT

You can spend the better part of a day driving the 7-mile (one way) South Rim, with its numerous canyon overlooks, interpretive trails, and visitor center. If you have more time, consider driving two hours to the lonesome North Rim, where steeper cliffs and superior river views put the canyon in full dramatic context. Only strong hikers should tred the inner-canyon routes that head to the river from the rims.

South Rim

The 7-mile South Rim Drive weaves through Gambel oak, serviceberry, and shrubby stands of sage (beware of roadside-grazing mule deer) before treating drivers to the first real glimpse of Black Canyon at Tomichi Point, one mile from the entrance.

For better views, continue 0.25 miles to the visitor center at Gunnison Point, where you can gather information before strolling out back for a grandstand view of the Gunny coursing below the snaggletoothed crags.

Consider hiking one of two trails here, either the 0.5-mile Rim Rock Trail, contouring the canyon’s edge, or, better yet, the 2-mile Oak Flat Loop, which offers more biodiversity as it dips 300 feet below the rim through aspen glades and Douglas fir. This damp, shady microenvironment is more prone than the North Rim to the frost-freeze cycle. This is one reason that the South Rim has eroded farther back from the river than the sun-struck cliffs of the North Rim.

For fine upstream views, drive another 1.75 miles to Pulpit Rock, a precipitous rock parapet crafted by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. The real drama, however, lies farther downstream, as the river drops 480 feet in 2 miles through the Narrows, one of the steepest river descents in North America. From the next three viewpoints—Cross Fissures, Rock Point, and Devils Lookout—you are likelier to hear the river than actually see it. Continue on to the Chasm, which is as close as most visitors get to the North Rim, 330 yards across the river. This is where the river makes a 90-degree bend to the southwest, bringing the canyon’s star attraction, Painted Wall, into view. At 2,250 feet, this is Colorado’s tallest cliff, where magma seeping into cracks in the dark gray basement rock has since hardened into pinkish pegmatite veins sparkling with crystal and mica.

Farther down the road, take the 300-yard interpretive trail to Cedar Point for a closer look at Painted Wall. You might spy world-class rock climbers inching up its face, though not from April through July, when the cliff is closed to allow peregrine falcons to nest undisturbed. The fastest creatures on Earth, they prey on other birds, colliding into them mid-air at 200 mph.

Sunset Point is a convenient place to watch the sun drop behind distant Grand and Monument mesas, but if you have time, head another mile to road’s end at High Point Overlook. This is one of the park’s highest elevations, at 8,289 feet, and trailhead for the 1.5-mile Warner Point Nature Trail. The gently descending path offers a vantage of luminous views of the San Juan Mountains and Uncompahgre Valley farmland to the south and the West Elk Mountains to the north. In autumn, piñon jays and Clark’s nutcrackers flit among 800-year-old piñon trees, taking seeds. Spring-flowering serviceberry develops purple berries in summer, a black bear staple. Trail’s end reveals views of the Gunnison winding out of the canyon and onto the Colorado Plateau.

North Rim

The North Rim receives far fewer visitors. Its gravel roads, intermittently closed visitor center, and remoteness also contribute to the pristine solitude. While it takes two hours to drive here from the South Rim, once here you can hit the highlights in an afternoon.

Start at the campground, with Chasm View Nature Trail. The 0.3-mile loop, through a piñon-juniper forest, leads to two lookouts poised at the canyon’s narrowest, with views of Painted Wall and upstream to the Narrows, where the roiling river cleaves a 40-foot-wide passage through 1,725-foot-high vertical walls.

For a closer look at this dark heart of the park—sunlight illuminates the abyss less than an hour a day—continue by car to the Narrows View. Make brief stops at the remaining overlooks: gravity-defying Balanced Rock, Big Island View, and Island Peaks. (“Island” refers to the pine-topped pinnacles rising from the river bottom.) The last stop looks out on the anthropomorphic Kneeling Camel formation.

Deadhorse Trail, 2.5 miles, begins at Kneeling Camel; the easier 1.5-mile North Vista Trail to Exclamation Point offers more diversity, with intermittent oh-wow views. Depart from the visitor center through sagebrush flats, then piñon and junipers. Don’t miss the signed turn-off to Exclamation Point. A riveting inner-canyon panorama awaits from atop sheer 2,000-foot-high cliffs. Picnic on a natural stone bench as white-throated swifts and swallows patrol the rim, nabbing bugs. Listen for the “kee-r-r-r” of red-tailed hawks above the river’s roar.

Elsewhere in the Park

Not for the faint-hearted, half a dozen routes drop to the river bottom from both rims. Figure on four hours down and back. You’ll need a wilderness permit (only 15 are issued a day) for the mile-long Gunnison Route, leaving from Oak Flat Trail near the South Rim visitor center. Steep switchbacks give way to a straight shot down loose rock, assisted by an 80-foot chain along one daunting chute. On all routes, wear long pants to protect against poison ivy and ticks. Forget swimming. Even in summer, this rushing river is hypothermic. But you can comfort aching feet in an icy pool, and bask in the pristine inner-canyon solitude as you contemplate the climb back up.

An easier way to experience the Gunny is by car. At the park’s South Rim entrance, turn on East Portal Drive, a 5.5-mile brake-burner wheeling down to a diversion dam, where river water is channeled through the 5.8-mile Gunnison Tunnel. Built from 1905 to 1909, it was the longest irrigation tunnel in the world when inaugurated by President Taft. Park downstream and hike along the river’s rocky bank, watching for rising trout and gray American dippers bobbing on the rocks.

Information

|

How to Get There The park’s South Rim lies 15 miles east of Montrose, CO, via US 50 and Colo. 347. The North Rim is 80 miles away via US 50 north to Colo. 92; you head south at Crawford, following park signs. When to Go At 8,000 feet above sea level, evenings cool off rapidly. High water makes for spectacular river viewing in May. Wildflowers peak in June. Brief thunderstorms add afternoon drama in July and Aug. By early fall, hiking is superb. Winter snow—possible Nov. to March—closes down both rim roads (which become cross-country ski trails). The road is plowed to the South Rim Visitor Center. Visitor Centers The South Rim Visitor Center is open year-round. The North Rim ranger station closes in winter and intermittently at other times. |

Headquarters 102 Elk Creek Camping The South Rim Campground (88 sites; 23 with electric hookups), sequestered amid the scrub oak, can be reserved up to three days in advance. The North Rim provides 13 sites with vault toilets on a first-come, first-served basis. Lodging There is no lodging in the park. The gateway towns of Gunnison (visitmontrose.com), Crawford, and Delta (deltacountycolorado.com/lodging) offer numerous hotels and B&B options. |

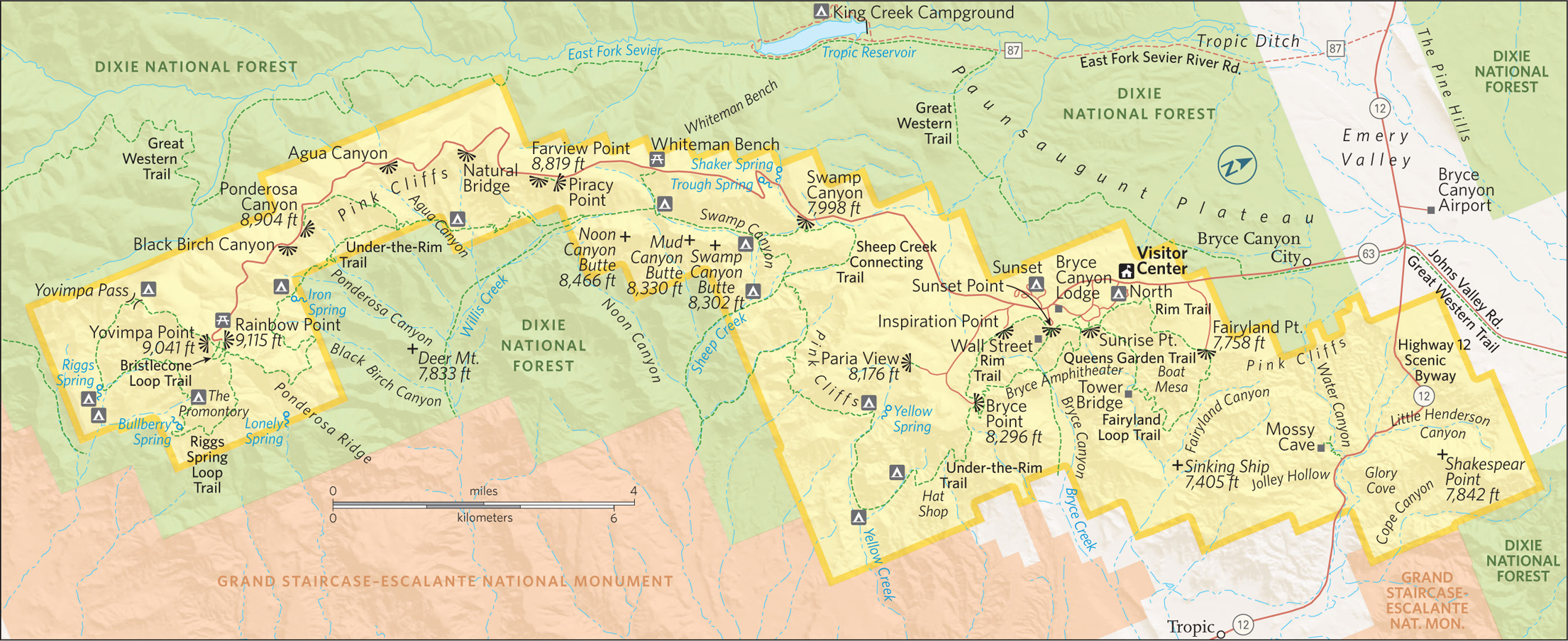

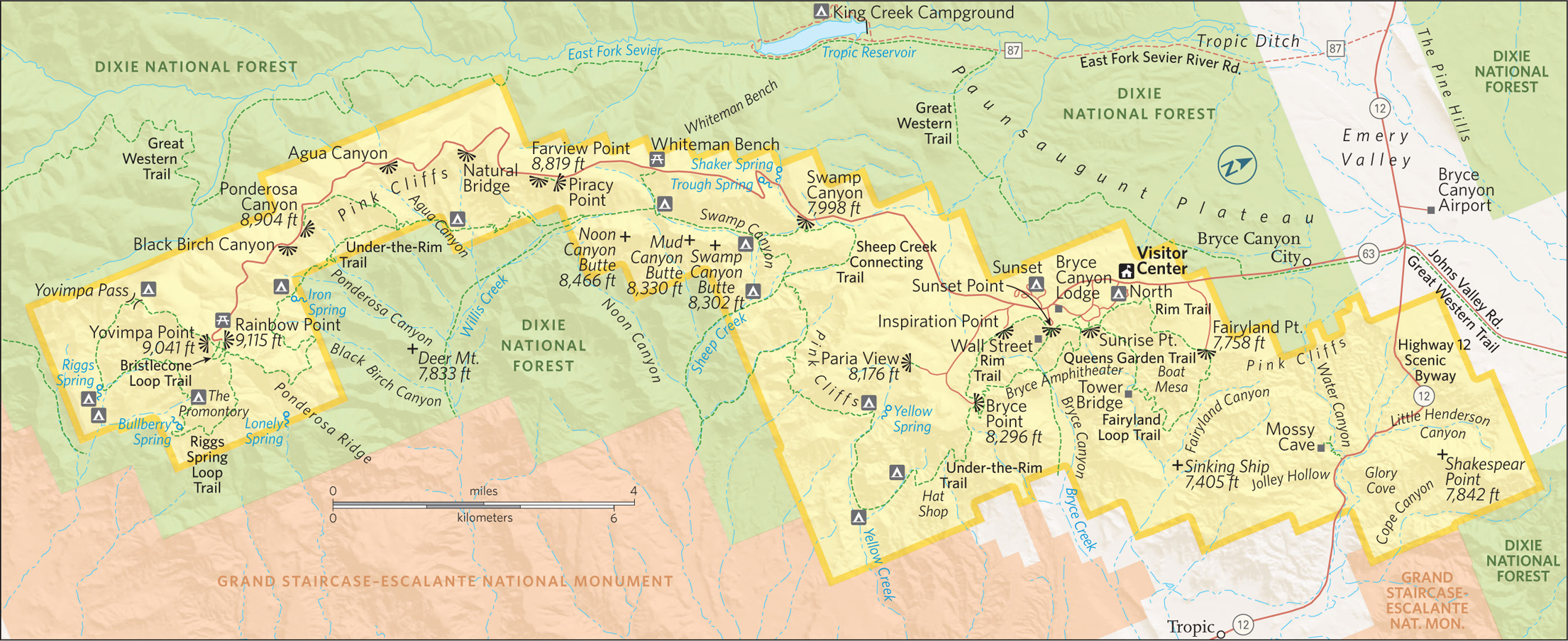

Hoodoos (odd-shaped pillars of rock) near Sunrise Point

Utah

Established September 15, 1928

35,835 acres

Mormon pioneer Ebenezer Bryce described the canyon as “a hell of a place to lose a cow.” These days, the cows may be gone, but it’s still a hell of a place to lose yourself. To gaze down on Bryce Canyon National Park’s surreal amphitheaters or to hike among the sunstruck hoodoos blurs the boundary between fantasy and reality. Just like the Paiute Indians who saw the faces of their ancestors frozen in stone, here you can let your imagination roam.

Bryce Canyon is not a true canyon created by river or stream. Instead, pelting rain, melting snow, and frost wedging have eroded the eastern escarpment of the Paunsaugunt Plateau into horseshoe-shaped amphitheaters crenelated with hoodoos, fins, and spires. Bryce Amphitheater—the park’s scenic heart—is the largest and most stunning of the park’s 14 amphitheaters, and the reason for Bryce Canyon’s national park designation.

The park was enlarged in 1931 to extend 24 miles along the plateau’s eastern edge, which provides lofty views of another world-class wonder: the Grand Staircase. This sedimentary series of benches and cliffs begins at Bryce and descends in colorful steps —Pink Cliffs, Grey Cliffs, White Cliffs, Vermilion Cliffs, Chocolate Cliffs—all the way to the Grand Canyon, exposing 240 million years of geologic history along the way. (The oldest rocks at the bottom of the canyon date back nearly 2 billion years.)

The park’s high altitude (8,000 to 9,000 feet) and pristine air allow for views of up to 200 miles. On a moonless night, the stars shine so bright they create their own shadows.

Closer at hand, endangered Utah prairie dogs keep watch over roadside meadows, where pronghorn antelope, reintroduced to the region, are commonly spotted from spring to fall. Ponderosa pines shade the northern plateau, while Douglas fir, blue spruce, and even some bristlecone pines forest the higher southern end of the national park. Rare plants, such as Red Canyon penstemon and Bryce Canyon paintbrush, stand out like jewels alongside hiking trails that weave through the “breaks” under the plateau rim.

Though small for a national park, Bryce packs a lot into its 56 square miles, including the 1924 Bryce Canyon Lodge. This masterpiece of American national park architecture—a National Historic Landmark—is the work of architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood, who designed the lodge in National Park Service rustic style to harmonize with its surroundings. It sits between Sunrise and Sunset Points and was built by the Union Pacific Railroad.

Although it’s been renovated several times, the lodge maintains its 1920s style. It consists of a large main building with a distinctive green roof (check out the handsome moiré pattern of its shingles) and log cabins set along the canyon edge.

And from here, it’s just a short stroll to the world’s most stunning sunrise. A dawn light washing over the hoodoos is a soul-stirring spectacle never forgotten.

► HOW TO VISIT

Any visit to Bryce should be a combination of two activities: visiting Bryce Amphitheater and taking the Scenic Drive to Rainbow Point. You can do both in five to six hours. If time is limited, forgo the scenic drive in favor of Bryce Amphitheater. Begin or end your day here for front-row views of the sunbaked hoodoos. Be sure to take some time to stroll the Rim Trail. For a lasting impression, hike below the rim for up close encounters with the hoodoos.

If you don’t want to hike, perhaps join a two-hour or half-day horseback riding trip through the hoodoos. From early May to mid-October, ride the free shuttle to help avoid parking-area congestion at Bryce Amphitheater. Inquire about ranger-led moonlit hikes and telescope stargazing.

While it might seem counterintuitive, given its iconic desertlike landscapes, a cold-weather visit should be considered. Bryce Canyon can transform into a frozen wonderland between November and April, when the plateau often is shrouded in snow.

Bryce Amphitheater

For sweeping vistas of the park’s marquee attraction, begin your visit at Bryce Point, the highest viewpoint (8,296 feet) overlooking Bryce Amphitheater. At sunrise, the low-angled light animates thousands of sherbet-colored hoodoos.

Look due north for the conspicuous Alligator, an eroded fin capped by white dolomite, and northeast to the Wall of Windows, a thin ridge punctuated by natural arches. To the east lies the town of Tropic (pop. 520), backed by distant Table Cliff Plateau. At 10,000 feet, this tectonic uplift is the highest plateau in North America.

Now drive back 2 miles to Inspiration Point. The short but steep trail to the highest of the three viewpoints, Upper Inspiration Point is well worth the muscle burn for its more expansive panorama of Bryce Amphitheater. On the trail back down from the point, take notice of the bristlecone pines holding fast to the retreating edge of the plateau, which erodes 1 to 4 feet every 100 years.

Consider a 15-minute stroll on the Rim Trail from Inspiration Point to Sunset Point instead of driving there. Along the way, you might see violet-green swallows and white-throated swifts darting along the cliffs above the dense deeply shadowed hoodoos of Silent City.

While you’re at it, carefully scan the skies for a rare condor sighting. And ignore the Uinta chipmunks cadging handouts.

Sunset Point provides the park’s most theatrical views, whether looking down on Queens Garden, the casbah-like Silent City, or the park’s most illustrious hoodoo, Thor’s Hammer, a solitary 150-foot-high limestone pinnacle brandishing a mallet-shaped capstone. Though the views are to the east, the setting sun sometimes casts a cloud-refracted glow across the amphitheater, as luminescent colors slowly coalesce into darkening shadows.

If you only do one hike in the park, begin at Sunset Point, allowing yourself two to three hours for the moderately strenuous 3-mile round-trip trek through the heart of this hoodoo fairyland. Begin on the Navajo Loop Trail through Wall Street. It’s the Lombard Street of national park trails, with 36 steep switchbacks cutting through towering stone fins that narrow into a deep slot where centuries-old Douglas firs look like giant matchsticks caught in a bench vise.

Continue to the trail’s junction with Queens Garden Trail, which winds through a spectacular hoodoo garden. In spring and summer, look for fuchsia-colored Bryce Canyon paintbrush, a rare plant growing only in Bryce Canyon.

Take the short spur trail to pay tribute to Queen Victoria, the most prominent spire, which stands in company of her stone-faced court. Continue on through a few stone passageways and ascend a ridge to Sunrise Point, where a half-mile stroll on the paved Rim Trail gets you back to Sunset Point. (When it is icy or slippery, it’s best to do the hike in reverse.)

Among the embarrassment of riches in Bryce Canyon National Park, a full-moon hike through Queens Garden qualifies as a life list experience.

Sunrise Point

Bryce Canyon Scenic Drive

This 18-mile scenic drive edges the eastern escarpment of Paunsaugunt Plateau, offering bird’s-eye panoramas from nine lofty viewpoints amid a Douglas fir and blue spruce forest. Drive directly south to the end of the road at Rainbow Point so you can more safely pull into the overlooks on the return trip.

Rainbow Point, the park’s highest elevation at 9,115 feet, provides the perfect leg-stretcher: a brisk lap on the 1-mile Bristlecone Loop, taking in deep lungfuls of the thin pine-scented air. The trail breaks out onto the plateau’s south rim, where a few bristlecone pines have endured a thousand years or more in windswept grace.

As you make your way around the loop, detour 200 yards to Yovimpa Point, where most days you can see dome-shaped Navajo Mountain 90 miles to the southeast. At 10,388 feet, the mountain is the highest point in the Navajo Nation. It is a sacred peak known as Naat’tsis’aan, Head of the Earth.

Heading back north on the Scenic Drive, the first three overlooks—Black Birch, Ponderosa Canyon, Agua Canyon—offer views of neighboring Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Agua Canyon is the most photogenic of the three, with two distinctive hoodoos, the Hunter and the Rabbit, poised on opposite sides of a steep ravine. Beyond, drifting clouds mottle an endless expanse of canyons, cliffs, and plateaus.

The next pull-off, Natural Bridge, provides a close-up view of the imposing natural arch, its reddish iron-oxide-rich rock in rich contrast to the deep green forest seen through its 85-foot-wide aperture.

Continue on to Farview Point, where you can see three of the five geologic “stairs” making up the Grand Staircase: the Pink Cliffs of the Aquarius Plateau, the Gray Cliffs of Kaiparowits Plateau, and the White Cliffs revealed on distinctive Molly’s Nipple. From the parking area, a 300-yard hike continues to Piracy Point. Without the crowds or roadside noise, a more fitting name would be Privacy Point.

The next two pull-outs, Whiteman Bench and Swamp Canyon, are used by hikers to connect with Under-the-Rim Trail, which runs 23 miles from Rainbow Point to Bryce Amphitheater. This is the backpacker’s version of the Scenic Drive.

If it’s near sunset, end your drive at Paria View Point, reached via the Bryce Point Road. This is the best place to watch the last rays of the setting sun bathe the hoodoos in dramatic golden light. (Bryce Amphitheater hoodoos lose the sun illumination much earlier.) In spring and summer, there’s a chance of spotting peregrine falcons here as well.

Elsewhere in the Park

Fairyland Point is often overlooked due to its approach via a mile-long spur road off Utah 63, 0.75 mile north of the park’s fee station. Nor does the shuttle go here. Here you will find intimate eye-level views of some of the park’s most dramatic hoodoos, and there’s a good chance you’ll spot wildlife, especially along the arduous 8-mile Fairyland Loop Trail.

Likewise, Mossy Cave, off Utah 12 4 miles east of Utah 63, sees fewer visitors though it’s an easy half-mile stroll to reach the grotto cave. The stream riffling alongside this trail is part of a 10-mile ditch dug by Mormon pioneers across the Paunsaugunt Plateau in the 1890s, and still provides life-giving water to Bryce Valley before draining into the Colorado River.

Diverted from the East Fork of the Sevier River, this is the only water to escape the geographical sump of the Great Basin.

Information

|

How to Get There From St. George, take Utah 9 east through Zion National Park, turning north on Utah 89. Turn right on Utah 12 and follow to Utah 63, the park entrance road (about 2.5 hours driving time). From Capital Reef National Park, follow Utah 12 west for 116 miles to Utah 63. When to Go From May to Sept., daytime temperatures are 64−80°F, cooling at night. Overlooks are crowded July and Aug. (also a time of occasional thunderstorms). In fall and spring, cooler temperatures (45–65°F) accompany fall foliage and wildflower displays. The Scenic Drive and overlooks are plowed and sanded in winter. Park rangers lead occasional snowshoe hikes through the surreal terrain. Roads are closed during and right after snowstorms. Visitor Center The Visitor Center is across from the fee station. It is open year-round. |

Headquarters P.O. Box 640201, Bryce Camping Two campgrounds nestle in Ponderosa pines near Bryce Amphitheater: North (open year-round, near the park’s general store) and Sunset (closed winter; close to hiking trails), each with 100 tent and RV sites, available first come, first served, or by reservation, 877-444-6777. Lodging Within the park, Bryce Canyon Lodge, on the National Register of Historic Places, provides 114 rooms, suites, and historic cabins close to the canyon’s rim (brycecanyonforever.com; 435-834-8700 or 877-386-4383). Just outside the park, five hotels, a few restaurants, and three campgrounds make up Bryce Canyon City (brycecanyoncityut.gov), while the nearby town of Tropic offers modest lodgings (brycecanyoncountry.com). |

Mesa Arch, in the Island in the Sky district

Utah

Established September 12, 1964

337,598 acres

The Green and Colorado Rivers—the original architects of Canyonlands National Park—have carved the park into three distinct districts: Island in the Sky, The Maze, and The Needles. Each could be a national park in its own right, yet the three sections combine to form something even greater: the wild red-rock heart of the American West.

In fact, Canyonlands is as wild today as when John Wesley Powell made the first documented journey down the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1869. Its 527 square miles remain the “most arid, most hostile, most lonesome, most grim, bleak, barren, desolate, and savage quarter of the state of Utah—the best part by far,” according to writer Edward Abbey.

When the Colorado Plateau began uplifting 20 million years ago, its streams carved ever deeper into the sedimentary layers, creating a vast branching network of canyons feeding into the rivers.

Island in the Sky, the most visited park district, hovers 2,200 feet above the Green and Colorado Rivers. As seen from its vertigo-inducing viewpoints, immense red-rock canyons stretch as far as the eye can see, with no evidence of people except the lonely track of the White Rim trail winding along the bench rock.

Ruins and rock paintings of ancestral Puebloans haunt the canyons of The Needles, where Organ rock shale and cedar mesa sandstone have eroded into colorful banded spires.

The lonely Maze district sees the fewest visitors, and not because it is any less alluring. This sandstone labyrinth of look-alike box canyons and impassable cliffs poses a supreme challenge even to veteran hikers.

The Colorado and Green Rivers join forces at the Confluence, the fluid center of the park. Their combined volume rushes into Cataract Canyon, through which churns the most intimidating white water in North America. Yet the river is lulled into submission some 14 miles downstream, beyond the park boundary, by Lake Powell and the Glen Canyon Dam. Other products of human effort are pressing in on park borders. Oil and gas wells springing up near the park have spurred controversial proposals of a Greater Canyonlands National Monument to keep this wild heartland intact.

► HOW TO VISIT

Each of the park’s three districts must be visited separately. As the entrances to The Needles and Island in the Sky are 110 miles apart, visitors with only a half to full day usually prefer Island in the Sky for its car-friendly viewpoints and easier access to both the town of Moab and Arches National Park.

On a second day, head to The Needles for more diverse trails and fewer visitors, or get an early start en route to Horseshoe Canyon; hike in to view the Great Barrier pictographs. Exploring the rugged Maze section is more of an multiday expedition than an excursion, requiring a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle.

Island in the Sky

Known as Isky within the park, this immense mesa brims with vast panoramas of the wild Colorado Plateau. Make sure your visit includes Mesa Arch at sunrise or Grand View Point for sunset—ideally, both.

Before dawn, make a beeline 6 miles past the visitor center to the Mesa Arch parking area and hike the groomed half-mile loop trail to the arch, which rises from the sheer edge of a 500-foot cliff. If the light is right, you’ll witness phenomenal orange colors reflecting off the 90-foot-long arch. In the basin beyond, Washer Woman Arch bends to its task, drawing photographers.

Trails dropping down to the White Rim bench or rivers below are brutal day-long affairs. There are easier plateau-top alternatives for stretching your legs. One mile from Mesa Arch, along the Upheaval Dome Road, the mile-long Aztec Butte trail lures you through a sandy wash and up a steep slickrock butte in search of 800-year-old granaries left by the ancient Puebloans. (Look for them under the caprock.)

A real kid-pleaser is Whale Rock, 3 miles farther down the same road. Reached via a half-mile trail, this 100-foot-high humpbacked dome begs to be climbed.

For a look at Upheaval Dome, continue to road’s end and hike the rocky half-mile trail. Take some time to ponder this mysterious crater ringed with jagged spires of polychromatic rock. Geologists still argue whether this is a collapsed salt dome or rock exposed by erosion after a meteor strike some 60 million years ago.

Return the way you came, and if time permits, take the turnoff to Green River Overlook for austere vistas of treeless Soda Springs Basin. Edged with White Rim sandstone, the basin looks like a salt-rimmed margarita. You can glimpse the Green River deep in the canyon’s cup. Originating in Wyoming’s Wind River Range, the slow-moving Green River meets up with the muddy Colorado River at the Confluence, 47 miles from the park’s northern boundary. Once back on the main road, head to its southernmost terminus at Grand View Point, 12 miles from the visitor center. Sync your arrival to an hour before sunset and ramble along the mile-long trail for spellbinding views of Junction Butte, Monument Basin, the Murphy Hogback, and The Needles and Maze districts. (Be sure to bring a flashlight for the return trip.)

Settle into a rocky nook and watch the rays of the setting sun splinter off the distant mesas.

Prickly pear fruit

The Needles

The Needles’ best attribute is a network of diverse trails designed for day-long hiking and backpacking. If you’re short on time, these four self-guided mini-hikes provide an educational sampler of the park.

Just 0.3 mile from the visitor center, park at Roadside Ruin and grab a trailhead pamphlet identifying native plants and how the Indians used them, as well as how they ground meal from rice grass, turned peppergrass into spice, and plucked nuts from piñon pines. The 0.3-mile trail ends at a small ancestral Puebloan granary where this precious bounty was stored.

Continue another 0.3 mile down the road, turn left, and follow signs to Cave Spring Trail. The spring itself is a rarity in canyon country: a year-round water hole that has sustained life for centuries.

The crudely furnished cowboy camp occupying the first alcove above the trail served as a makeshift park headquarters in the early days. Ancestral Puebloan paintings decorate the fire-blackened grotto next to the camp, where delicate maidenhair ferns line a mossy seep of life-giving water. Farther down the trail, ancient painted handprints on the rock seem to be reaching across the centuries.

Continue clockwise on the 0.6-mile loop trail, climbing two wooden ladders to reach the slickrock above. You’ll be compensated with fine views of the banded spires of The Needles to the west.

Back on the Big Spring Overlook Road, stop at the Pothole Point Trail, where water-filled depressions dapple the slickrock. After a rain, these ephemeral pools burst with micro-life: horsehair worms, snails, tadpoles, and fairy shrimp hatch from drought-resistant eggs. Be careful not to touch the water. The pristine potholes react immediately to chemical imbalances, in effect poisoning them.

Even if the potholes are dry, this 0.6-mile loop trail offers reward with far-reaching views of The Needles formations. Plus it is a shorter, easier version of the Slickrock Trail just down the road.

The 2.4-mile Slickrock Trail keeps to the high ground between Big and Little Spring Canyons, with four viewpoints serving up the park’s most distant panoramas as well as your best shot at spying elusive bighorn sheep. Look for their giveaway: white rump patches.

Report all bighorn sightings to a park ranger. Because of fluctuations in the sheep population, the park tracks sightings and locations of these animals.

If you don’t have two hours for the Slickrock Trail, continue on to road’s end at Big Spring Canyon Overlook for an up-close view of steep canyons crenellated by towering buttes.

This overlook is also the trailhead for a popular day trip on the Confluence Overlook Trail, a shadeless 5.5-mile trudge across Big Spring and Elephant Canyons and along a jeep trail to the unfenced edge of a 1,000-foot gorge where the Green and Colorado Rivers join forces.

To experience the essence of The Needles, bypass any of the above attractions to allow a half-day hike into ultrascenic Chesler Park, a 1,000-acre grassland meadow edged by the park’s most spectacular display of these namesake spires. The 2.7-mile trail leaves from the Elephant Hill picnic area at the end of a 3-mile graded gravel road, and weaves through a narrow slot to a saddle overlooking Chesler Park. Take some time to meander through the meadow, inhaling sprigs of crushed sage, but don’t get lost on the network of trails luring you deeper into Needles backcountry.

Count on a full day to visit Horseshoe Canyon, a detached section of the park that preserves a gallery of life-size figures that may have been painted as recently as 1,000 to 2,000 years ago.

The 3.5-mile-long trail (figure on 4 to 6 hours round-trip) drops 780 vertical feet to the canyon bottom and heads up Barrier Creek, past three minor pictograph panels, to the Great Gallery, a 300-foot-long panel displaying more than 20 shamanic effigies in red-ocher paint. Writer Edward Abbey described these ghostly figures as “apparitions out of bad dreams.” Get an early start: It’s a 2.5-hour drive from Moab just to reach the remote trailhead; the last 30 miles are dirt road.

To get from Horseshoe Canyon to Hans Flat Ranger Station, you return the way you came, turn south at the fork, and continue on. The distance from the canyon to the ranger station is 28 miles.

You’ll need two things: a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle and the necessary chutzpah to drive it down the hairpin turns of the Flint Trail to what early cowboys called “Under the Ledge,” a labyrinth of fins, canyons, pinnacles, and buttes called The Maze. It’s virtually trail-less, with some routes marked by cairns. (If you prefer to stay atop the mesa, outside park boundaries, you’ll find the best Maze views at Panorama Point, 12.5 miles from Hans Flat.)

After descending the Orange Cliffs, the Flint Trail splits. One road heads to the Maze Overlook (30 miles on a bumpy road—four-wheel-drive is a must—from Hans Flat). The overlook across this curving labyrinth is a portal for multi-day backpacking adventures. The views—including a maelstrom of sandstone crested by the Organ shale Chocolate Drops, 350-million-year-old formations—are worth the bumpy ride.

A second road goes through the Land of Standing Rocks (more Organ shale formations) to the Doll House, 42 miles from Hans Flat, where you can hike down to the Colorado River at Spanish Bottom. Shuttle-bus pick-up at Spanish Bottom can be arranged. Jet boats connect with Moab by river—the easy way back.

Information

|

How to Get There To reach Island in the Sky from Moab, head north on US 191 for 10 miles to Utah 313, and drive 22 miles to the visitor center. To reach The Needles head south on US 191 to Utah 211, then west 34 miles to the park entrance. The Maze is reached via I-70, then south on Utah 24. Follow for 25 miles to a signed dirt road, which leads 32 miles to Horseshoe Canyon and 46 miles to Hans Flat Ranger Station. When to Go Brisk spring and balmy fall are ideal for hiking, though prepare for a wide range of weather. In summer, temperatures often hit triple digits; monsoons bring needed rain—and flash flooding. Mild winters are not uncommon, but even a light snow can close down dirt roads. Visitor Centers Island in the Sky and Hans Flat/The Maze visitor centers are open all year; Needles closes early Dec. through Feb. |

Headquarters 2282 SW Resource Blvd. Camping There are two campgrounds in the park, the Bates Wilson–designed Squaw Flat Campground (26 sites) in The Needles, and Willow Flat Campground (11 sites) at Island in the Sky. Both are first come, first served and provide vault toilets, fire grates, and tables. To book one of The Needles three group sites (15 to 50 people) or to obtain a permit camping in the backcountry: canypermits.nps.gov. Lodging There are no hotels within the park. Moab (discovermoab.com) is a busy tourist town with numerous campground, lodging, and dining, options. Monticello and Green River, closer to The Needles and The Maze, offer fewer options. |

Scott M. Matheson Wetlands Preserves

Moab, Utah

▷ The Nature Conservancy’s Scott M. Matheson Wetlands Preserve provides a sharp contrast to the surrounding redrock cliffs and arid desert. It’s a bird-watcher paradise, with over 200 species of birds, including spring migrants and summer nesters. Other animals in the area include beavers, muskrats, mule deer, raccoons, and the northern leopard frog. Open year-round, from dawn to dusk. Located east of Canyonlands National Park and south of Arches National Park. nature.org; 435-259-4629.

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Arizona/Utah

▷ Lake Powell, the desert, and the red-rock canyons offer 1.2 million acres of water-based and backcountry recreation activities, primarily in Utah, from hiking to watersports and boating (rentals available). Guided tours of both the dam (from the Carl Hayden Visitor Center, Page, Arizona) and Lake Powell allow visitors to better understand the area. There are numerous campgrounds (permit required in the Orange Cliffs area). nps.gov/glca; 928-608-6200.

Moab, Utah

▷ Dead Horse Point is a rock peninsula located atop a 6,000-foot-high sheer sandstone cliff connected to the mesa solely by a narrow strip of land known as the neck. Stunning vistas of the Colorado River and the surrounding rock strata of canyon country can be seen from the point. Camping (reservation required), hiking, and biking are options. Located next to Canyonlands National Park and 28 miles from Arches National Park. Fee. stateparks.utah.gov/park/dead-horse-point-state-park; 435-259-2614.

Central & Southeastern Utah

▷ Spanning 1.2 million acres, the Manti La Sal National Forest includes three mountain blocks in central and southeastern Utah. The National Forest encompasses historic drawings and ruins as well as beautiful mountains and canyons with places to hike, fish, and camp. Take a drive along the scenic byways, or get around by bicycle or horse. Water sports and winter sports round out the outdoors options. The national forest is south of Canyonlands National Park via US 191. fs.usda.gov/mantilasal; 435-637-2817.

Moab, Utah

▷ Regarded as a public lands treasure, the Sand Flats Recreation Area includes a high plain of slickrock domes, bowls and fins, and in the east it rises in elevation to meet the colorful mesas and nearly 13,000 foot peaks of the La Sal Mountains. Popular among bikers, the area has the popular Slickrock and Porcupine Rim bike trails and three 4×4 trails. Fees apply to day use and camping. Located near Moab, Utah. sandflats.org; 435-259-2444.

Westwater Canyon Wilderness Study Area (BLM)

Moab, Utah

▷ Westwater Canyon is characterized by its great scenery and unique geologic features including black pre-Cambrian rock (the oldest exposed rock in Utah), which forms the inner canyon. Considered by many to be the nation’s best overnight white-water river trip; most recreation users come primarily to experience rapids, such as Skull and Last Chance. Permits are required for all river trips. Located northeast of Canyonlands and Arches National Parks. The wilderness study area is accessible from the interstate via the Cisco and Westwater exits. 435-259-2100.

Along the Scenic Drive

Utah

Established December 18, 1971

241,904 acres

“The Reef” is the least known of Utah’s five national parks. Its defining geographical feature, the nearly 100-mile-long Waterpocket Fold, is an impenetrable sandstone barricade that kept travelers at bay for centuries. In 1962, the first paved road was built across the Reef, unlocking a monumental wilderness of domes, natural bridges, spires, and slot canyons, and presenting a vanished way of life. Capitol Reef National Park park brings travelers back to a bygone era that reveals America’s sturdy pioneer roots.

Capitol Reef’s name, according to local lore, derives from early prospectors who’d sailed great waters and were wary of reefs. Speaking of water, the park’s geologic layers, thrust on edge by primal geologic forces 35 to 75 million years ago, testify to a story of Permian-era seas, Triassic tidal flats and swamps, Jurassic sand dunes, and late-Cretaceous seas.

The ancient Fremont people left their story on these rocks in the form of petroglyphs. Mormon pioneers arrived in the 1880s, planting thousands of fruit trees at the fertile confluence of the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek. In the 1920s, the area’s beauty inspired a local club to envision a state park. Franklin D. Roosevelt responded by creating the Capitol Reef National Monument in 1937. It became a national park 34 years later.

► HOW TO VISIT

On a half-day visit, choose either the roadside attractions of Utah 24, including a 1.8-mile hike to Hickman Bridge, or opt for the park’s Scenic Drive, stopping to explore Grand Wash or Capitol Gorge on foot. (A full day allows you to follow both the Utah 24 and Scenic Drive itineraries.) If you have another day and a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle, plan an off-road loop through desolate Cathedral Valley (64 miles). Or take the southern Notom-Bullfrog Road to the Burr Trail Road to explore slot canyons.

Utah 24

Built in 1962, this two-lane highway winds 14 miles through the park’s mid-section. It is the only paved road to breech the nearly 100-mile-long Waterpocket Fold. Heading east from the town of Torrey, stop at Chimney Rock, a spire crowned by golden-hued Shinarump capstone. Enthusiastic hikers can tackle a steep 3.5-mile loop trail for a bird’s-eye view of the formation and displays of petrified wood.

A half-mile beyond the trailhead is Panorama Point turnoff. Continue to the end of the mile-long dirt spur road, where two trails start at the parking area. One leads 0.1 mile to the Goosenecks Overlook, where, 800 feet down, are the entrenched meanders of Sulphur Creek that cut through Kaibab limestone, among the park’s oldest exposed rock. (Fossil-rich Kaibab limestone forms the North Rim of the Grand Canyon.) The 0.4-mile Sunset Point Trail winds through a garden of weathered piñon pines and leads to a bench that faces one of the park’s most photogenic sights. Framed by brick-red towers, the Fremont River curves through an escarpment topped by monolithic bone-white Navajo sandstone. Thirty miles away, the highest peak of the Henry Mountains, Mount Ellen (11,615 feet), dimples the horizon.

Continue on Utah 24 past the visitor center and Scenic Drive, stopping to peer into the 1896 Fruita Schoolhouse, which until 1941 also served as a dance hall and community center. Look for “Fruita Grade School” carved into the rock behind the school, where generations of school kids left their marks.

For ancient examples of rock art, continue 0.3 mile to the Petroglyph Pullout, where a boardwalk parallels a wall of Wingate sandstone festooned with bighorn sheep and figures sporting headdresses. The Fremont people left the area around A.D. 1300; petrogylphs weren’t all they left behind. The Mormon pioneers reportedly uncovered irrigation ditches in the fields where apple orchards now grow. The Fremont stored their corn and beans in nearby granaries. To see a granary, continue 0.75 mile east on Utah 24 to the Hickman Bridge parking area and embark on a 1-mile hike that takes in Hickman Bridge, a 133-feet-long arch reaching 125 feet over an arroyo (creek). The last stop on Utah 24 is the 1882 Benhunin Cabin. Barely 200 square feet, this sandstone structure housed 13 adults. (The boys bedded in a rock alcove, while the girls slept in a wagon.)

Fruita & the Scenic Drive

Stop at the visitor center to pick up a self-guided brochure of the Scenic Drive, then head to the nearby Fruita Historic District for a glimpse of early pioneer life: mule deer grazing the orchards, a classic barn, and the old blacksmith shop containing Fruita’s first tractor and a scattering of horse-drawn farming equipment. Farther down the road, stop at the Gifford Farmhouse, as much pioneer museum as country bakery (try the apple pie).

Continue on the Scenic Drive, turning on a graded road to Grand Wash. You’ll pass the 1901 Oyler Mine, whose uranium was used in elixirs back when radioactivity was considered a cure rather than a curse. Farther along, a 1.7-mile-long trail leads to Cassidy Arch, named for outlaw Butch Cassidy, who allegedly used Grand Wash to get to Robber’s Roost. The Grand Wash road ends where the real fun begins: Hike the narrowing canyon, at one point 600 feet high and 16 feet wide.

Continue on the Scenic Drive to Capitol Gorge, another narrow passage. (This was only route between Torrey and Hanksville until Utah 24 opened in 1962.) An easy mile-long walk from the parking area takes you past Fremont petroglyphs (A.D. 600 to 1200) to a Pioneer Register etched in stone. A “who’s who” of early pioneers, it includes characters such as Cass Hite, a member of Quantrill’s Civil War Raiders who struck gold in the park’s Glen Canyon and had a town named in his honor (later submerged by Lake Powell). Just beyond lie the Tanks, natural water pockets hosting a multitude of aquatic life, including water striders and fairy shrimp.

Cathedral Valley

Tackling the 60-mile unpaved Cathedral Valley Loop, which begins 12 miles east of the visitor center on Utah 24, requires a high-clearance vehicle and favorable road and river conditions (for information, 435-425-3791). The drive starts with a fording of the foot-deep Fremont River. The road climbs through the Bentonite Hills, a landscape of pastel colors (one of the area’s nicknames is Land of the Sleeping Rainbow). After Harnet Mesa, the road loops around Upper Cathedral Valley, with fine views of 500-foot-high monoliths and the fluted Walls of Jericho. A 10-minute hike leads to weather-beaten Morrell Cabin. In Lower Cathedral Valley, a short spur road runs to the Temple of the Sun and Temple of the Moon monoliths. The road continues 15 miles before rejoining Utah 24 at Caineville.

Elsewhere in the Park

Paralleling the eastern escarpment of the Waterpocket Fold from its junction with Utah 24, the Notom-Bullfrog Road offers access to remote slot canyons. Continue on to Surprise and Headquarters Canyons, which provide a good introduction to canyoneering. Both are 2-mile round-trips. Upper and Lower Muley Twist canyons offer remote backpacking adventures, though it may be adventure enough just to drive up the precipitous Burr Trail. This 1880s sheep trail was graded into a road during the uranium boom in 1953, courtesy of the Atomic Energy Commission. Stop at the top of the road to admire the switchbacks you’ve just navigated, and take in the immense views of Swap Mesa and the Henry Mountains, the last places to be mapped in the Lower 48.

The Burr Trail returns to pavement at the park’s western boundary, where you can continue to Boulder, 32 miles away, and loop back to Capitol Reef. But before you do, if you have a four-wheel-drive vehicle, consider taking the spur road, following Upper Muley Twist Canyon for 3 miles to the Strike Valley Overlook, with the park’s best view of the curving Waterpocket Fold.

Information

|

How to Get There From Green River (95 miles east) take I-70 west to Utah 24, which leads to the park’s east entrance. From Bryce Canyon National Park (123 miles southwest of Capitol Reef), a more scenic route on Utah 12 loops over Boulder Mountain to Utah 24 and the park’s western entrance. When to Go Orchard blossoms kick off spring, when ideal hiking temps (60–70°F) are punctuated by spells of frost. Summer mercury hovers in the low 90s, but evenings cool nicely. From mid-July through Sept., afternoon rain can unleash flash floods. Oct. ushers in gold cottonwoods and cooler temps. Intermittent snow cover makes for a winter wonderland. Visitor Centers At the junction of Scenic Drive and Utah 24, the year-round visitor center (435-425-3791) has exhibits, a bookstore, and orientation movie. |

Headquarters Capitol Reef National Park Camping Campsites (fee) are first come, first served. The Fruita campground (71 sites) has restrooms but no hookups. Campgrounds with pit toilets and fire grates are found in Upper Cathedral Valley (6 sites) and on the Notom-Bullfrog Road at Cedar Mesa (5 sites). Lodging There is no lodging in the park. Ten miles east of the visitor center, Torrey (torrey utah.org) and nearby Teasdale (capitolreef.org/teasdale) provide lodgings, from motels to the Lodge at Red River (redriverranch.com). Lodging and camping facilities can be found in and near Cainville and Hanksville, also to the east. |

View from Desert View Drive, on the South Rim

Arizona

Established February 26, 1919

1.2 million acres

Like the Statue of Liberty, the Grand Canyon is an American icon. (It’s almost as if the majesty of the American West has been poured into a limestone riverbed.) Theodore Roosevelt considered it his civic duty to urge every American to see it. And around five million people come to Grand Canyon National Park every year, from all over the globe. Indeed, the canyon is considered one of the seven wonders of the natural world.

People come not because this is the deepest, narrowest, or even longest canyon in the world. It’s not. But the sum of these features make it the grandest by far. The park runs for 277 river miles, preserving 1,904 square miles of wilderness. From 258-million-year-old limestone capping the rim to 1.8 billion-year-old Vishnu schist a mile below, from stately ponderosa pine forests to prickly desert scrub, bighorn sheep to Kaibab squirrels, Mother Nature is on full display here.

You can shake the crowds by hitting the trails or visiting the remote North Rim. Seen 10 miles across the chasm from the South Rim, it’s 212 miles away. Ninety percent of park visitors stick to the South Rim, where tourism took hold shortly after John Wesley Powell made the first descent of the Colorado River in 1869. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railways reached the South Rim in 1901, paving the way for concessioner Fred Harvey to shape the Grand Canyon experience with mule rides, luxury lodgings, and rustic Western decor, still part of the scene today.

Looking out over the canyon still feels like it did back in 1897, when travel writer Amelia Holleback described the experience: “As if half the world had fallen away before your feet, and after that, you are no longer on the same old Earth.”

► HOW TO VISIT

On a one-day visit to the South Rim, head straight to Mather Point, behind the visitor center, and make your way along the rim to Grand Canyon Village. Then decide whether to take the shuttle to Hermits Rest (the shuttle doesn’t run in winter) or drive your own vehicle to Desert View. Wherever you end up, stay to watch the sunset. On a second day, explore what you missed the day before on the South Rim, then make the four-hour-plus drive to the North Rim. Arrive in time for a late-afternoon hike to watch the sunset from Cape Royal. An overnight trip requires advance reservations, usually months in advance. In the case of a mule or river trip, it could be a year.

Main lobby of the El Tovar Hotel

Grand Canyon Village

If short on time, park at the visitor center, but skip the orientation video in favor of the real thing at Mather Point, just a 100-yard walk away. The rail-grabbing view extends 10 miles across the chasm, where the forested North Rim descends in monumental ridges, steep canyons, hogbacks, and buttes to the Colorado River, one mile below. You’ll find the chiaroscuro of sunlight and clouds across the chasm more engaging than any video.

Take in the view on a stroll along the Rim Trail to Yavapai Point (0.75 mile). Below you, the Tonto Platform flattens out to the edge of the inner gorge. Beyond, Bright Angel Canyon rises to meet the North Rim, a cross-canyon gorge created by the massive Bright Angel Fault. A grove of Fremont cottonwoods at the foot of Bright Angel Canyon shades the Mary Colter–designed Phantom Ranch, rustic cabins built in 1922 and still reached only by foot, mule, or boat. (Colter designed eight structures in the park.)

The two nearby suspension bridges are the only places that cross the Colorado River for several hun-dred miles.

At Yavapai Point, explore the small museum built in 1928 as an observation station for scientists and visitors. A topographic model, a geologic column of rock layers, and daily ranger talks provide a crash course on two billion years of Earth history.

You can walk the geologic history of the canyon by going west on the Trail of Time, edging the canyon’s rim, where each stop is marked by a bronze medallion signifying a time period of a million years. When you reach Verkamp’s Visitor Center (1.3 miles away), you will have walked 1,840 million years back in time—and straight into the hurly-burly of the Historic District, the park’s epicenter for eating, drinking, and shopping. The historic complex includes the original 1909 log-built train depot, the 1905 El Tovar Hotel, the Mary Colter–designed Lookout Studio and Hopi House, and the Victorian-rustic Kolb Studio. Each interprets the Grand Canyon experience through its unique architecture. And each is worth poking into for the Native American crafts, landscape photography, curio kitsch, and historical exhibits.

Surprisingly, the busy village is also a great place to spot one of the 74 or so California condors inhabiting the region, especially from mid-April through July. Look for them roosting on the north-facing cliffs or in the Douglas fir trees below the Bright Angel Lodge toward sunset or early in the morning.

Just beyond Kolb Studio, watch backpackers make their way down the Bright Angel Trail, a classic 9.5-mile route down to the river. Or try it yourself, at least as far as the first tunnel, 0.2 mile down, where haunting pictographs are a reminder that this once was a prehistoric byway. From the Village, take the blue Village Route shuttle or walk the 2 miles back to the visitor center.

A mule train along the Bright Angel Trail at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon

The only way to explore the area west of the Village and its nine overlooks is via the Hermits Rest shuttle, walking the 7.8-mile Rim Trail that parallels the road, or pedaling a bike. Whatever the method, your first stop is Trailview Overlook, a cliffside pull-out where you can watch the mule trains leave each morning down Bright Angel Trail.

From the second pullout, Maricopa Point, you can spot ruins of the Orphan uranium mine, which closed in 1969. Owners had planned to build a luxury hotel in its place until Congress passed a law to buy the property and terminate mineral rights, preserving the canyon’s integrity. Beyond the site, the road bends back to Powell Point, on the South Rim.

The point is named for John Wesley Powell, the indefatigable one-armed visionary who made the first survey of the Grand Canyon in 1869. He started with nine men in four boats. After three months, six emaciated men and two splintered boats emerged from the canyon. Though Powell went on to become director of the U.S. Geological Survey and the first director of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology, he is best known for his daring river expeditions.

For river views, however, you’ll have to continue on to Hopi Point. No need to wait for the shuttle. You can walk the 0.3 mile in 10 minutes. This promontory juts far into the canyon, providing unobstructed views east and west. It’s one of the best sunset-watching spots on the South Rim.

The white water churning below is Granite Rapids, named by Powell. His place names—Lava Rapids, Marble Canyon, Bright Angel—are descriptive compared to those of his close associate, the geologist Clarence Dutton, who began a more esoteric tradition of labeling landforms with Asian and Egyptian religious names. Thus we have the likes of Shiva Temple.

If time’s an issue, bypass similar views at Mohave Point. Both the road and the trail here skirt the sheer 3,000-foot cliffs at The Abyss and Monument Creek Vista before arriving at Pima Point, where an aerial tram once ran supplies 6,000 feet down to an upscale tent camp built in the 1920s by the Santa Fe Railway. Abandoned in 1930, remains can still be glimpsed.

The road ends at Hermits Rest, a medieval jumble of stone with a cairn-like chimney, designed in 1914 by Mary Colter. “You can’t imagine what it cost to make it look this old,” said Colter, who went so far as to have soot rubbed into the stones above the fireplace. The “hermit” who inspired this creation was Louis Boucher, an eccentric prospector, guide, and campsite operator living alone below the rim, known for his white beard and white mule. The alcove fireplace in this snack and curio shop has warmed generations of hikers returning from the Hermit Trail, a tough 10.8-mile descent to the Colorado River.

Desert View Drive

From the Grand Canyon Visitor Center, Desert View Drive edges the canyon for 23 miles east to Desert View. The only shuttle buses that operate on Desert View Drive provide access to Yaki Point and the South Kaibab trailhead, where cars are prohibited.

To visit Yaki Point, board the shuttle at the visitor center, the earlier the better as this is a prime sunrise viewing spot. Another option is to take the 7-mile South Kaibab Trail (one shuttle stop before Yaki Point). The trail winds down the spine of Cedar Mesa to the river, but you only have to descend 1.8 miles to Ooh Aah Point for a stunning view of Upper Granite Gorge and Zoroaster Temple in the morning light.

Desert View Drive’s first major overlook is Grandview Point. At 7,400 feet, the towering ponderosa pines have replaced the forest of dwarf juniper and piñon pine. The steep 4.5-mile Grandview Trail drops 3,000 feet down to Horseshoe Mesa, where early Indians once gathered blue copper ore to use as paint. Miners later worked the ore at Last Chance mine, but it wasn’t long before one prospector, John Hance, realized the real gold was in tourism. In the 1880s, he led the first sightseeing parties into the Grand Canyon, telling tall tales to match the grand landscapes. He claimed to have dug the Grand Canyon himself, and that the river was so muddy that “to get a drink you have to cut a piece of water off and chew it.”

The steepest and most hazardous section of the Colorado River, Hance Rapids can be glimpsed from the next overlook, Moran Point. This promontory is named after artist Thomas Moran, who joined Powell on his third expedition. This resulted in a 12-foot-long masterpiece, Chasm of the Colorado, which was purchased by the U.S. Congress and hung in the U.S. Capitol. Moran’s work inspired President Theodore Roosevelt to proclaim the canyon a national monument in 1908.

For a change of pace, stop at the Tusayan Ruin and Museum, one of the park’s 4,300 archaeological-recorded sites. The short self-guided trail loops around ancestral Puebloan structures dating to A.D. 1185. Notice the sipapu (hole in the floor) within the circular kiva, the symbolic portal from which ancestors emerged from a previous world. The present-day Hopi believe their ancestors emerged from a similar sipapu at the bottom of the canyon, and still make pilgrimages there.

Upon reaching Lipan Point, you can see all the way to the Vermillion Cliffs and the Painted Desert as the river makes a lazy bend around the Unkar Delta and enters the dark inner gorge.

At Desert View, Mary Colter’s 70-foot Watchtower rises along the Rosetta Stone of the Colorado Plateau. Inside, climb the 85 steps of this cryptic modern-day kiva to ponder paintings by Hopi painter Fred Kabotie, petroglyphs, and re-creations of Native American symbology. From the top of the tower—the South Rim’s highest point—you can see Navajo Mountain, Echo Cliffs, and, 5,000 feet below, the sinuous Colorado River.

Less crowded and 1,000 feet higher than the South Rim, making it cooler, the remote North Rim also has far fewer facilities, which are clustered at canyon’s edge 14 miles south of the entrance station. For an introductory overview, walk right through historic Grand Canyon Lodge and onto the 0.25-mile paved trail, which leads to Bright Angel Point.

This precipitous rock spine divides Transept Canyon from Roaring Springs Canyon, where gushing springs indeed roar from 3,000 feet below. A self-guiding pamphlet points out, among other things, marine fossils and a 600-year-old juniper tree, while trail’s end takes in soul-stirring views of Deva, Brahma, and Zoroaster Temples.

If you want to drop below the rim to the water, take the nearby 14.2-mile North Kaibab Trail, which switchbacks steeply down the colorful rock layers. The top portion of the trail provides an invigorating foray through ponderosa pines and white fir. Coconino Overlook, 0.75 mile down, or Supai Tunnel, 1.7 miles down, are obvious turnaround points.

For the North Rim’s most epic views, drive 10 miles northwest through forests of spruce and fir, past meadows bordered by quaking aspen, to Point Imperial. At 8,803 feet, this is Grand Canyon’s highest overlook, taking in not just the canyon as it widens out of Marble Canyon, but also the Painted Desert and the Navajo Nation lands.

Now backtrack 3 miles to the Cape Royal Road and follow it onto the Walhalla Plateau, surrounded on three sides by the canyon. Picnic tables beckon under ponderosa pines at Vista Encantada. The second overlook, Roosevelt Point, provides a rare glimpse of the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. And 5.5 miles farther down the road lies the trailhead to 4-mile Cape Final, which leads to a spectacular panorama, with distant views of Vishnu and Jupiter Temples. This is your best shot for solitude.

Before reaching road’s end at Cape Royal, consider two short side trips. Walhalla Glade opposite the Walhalla Overlook reveals the rock outlines of a 900-year-old pueblo. And the half-mile Cliff Spring Trail passes an ancestral Puebloan granary before reaching a mossy alcove spring, a natural spa for many of the park’s 373 feathered species.

The grand finale at road’s end, Cape Royal is the southernmost point on the North Rim. The cape’s prow is reached via a half-mile paved path edged in sage and fragrant cliff rose. Detour for an exhilarating skywalk atop the flying buttress framing Angel’s Window, a Kaibab-limestone arch.

At Cape Royal, settle in to watch the lowering sun lacquer the banded escarpments and towers: Wotan’s Throne, Freya Castle, and Vishnu Temple, all in luminous light as shadows deepen across what John Muir called “nature’s own capital city.”

Into the Canyon

Whether by oar, hoof, or boot, there’s no easy way to experience the canyon’s inner sanctum. All hikes hereabouts are strenuous. Most hikers stick to the South Rim’s 9.5-mile Bright Angel Trail for its shade and water. The South Kaibab Trail from Yaki Point (6.2 miles) provides a quicker ridge-line descent, but it is a hot, waterless climb back out. (Most hikers return via Bright Angel.) From the North Rim, the only maintained route to the river is the North Kaibab Trail, an arduous 14.2-miler. All three trails connect via the River Trail at the bottom, where two foot bridges span the river. You can camp at Bright Angel Campground (permit required) or bunk in the dorm or cabins at historic Phantom Ranch, a leafy haven nestled near where Bright Angel Creek enters the Colorado River. Lodging reservations should be made a year in advance.

The classic overnight mule trip to Phantom Ranch also can be challenging—to your nerves and knees. (Mules favor the trail’s outside edge.) Plan in advance; these trips can fill up a year ahead of time. Mule trips from the North Rim dip below the rim but don’t go all the way to Phantom Ranch.

A multi-week raft trip through the arterial heart of the Grand Canyon is for most a life-changing adventure. Along the epic 225-mile float from Lees Ferry to Diamond Creek, the river tumbles through 150 rapids, including infamous Lava Falls and Hance Rapids, in between more placid stretches. The dam-release water is a hypothermic 46°F, even when mercury hits 110, adding to the extreme nature of this trip. Motorized boat trips and half-canyon trips shorten the time commitment.

Information

|

How to Get There To reach the South Rim, take Ariz. 64 (US 180 from Flagstaff) from I-40. A slightly longer, less trafficked option via US 89 from Flagstaff skirts the San Francisco Peaks to Ariz. 64 and enters the park at Desert View. The North Rim, 10 miles away as the bird flies, is a four-hour-plus drive from the South Rim. When to Go Summer and school vacation times are peak seasons. To avoid crowds, visit from Oct. to April. Spring sees moderate weather, wildflowers, and active wildlife. Turning aspen and mild weather make Oct. an ideal month. The North Rim usually closes mid-Oct. through mid-May. The South Rim stays busy all winter. Visitor Centers The South Rim has two visitor centers, the main one near Mather Point and a smaller one at Verkamp, east of the El Tovar Hotel. Both are open year-round. The North Rim Visitor Center is open mid-May to late Oct. |

Headquarters 20 South Entrance Rd. Camping The park has more than 500 campsites. Reservations (recreation.gov; 877-444-6777) can be made at year-round Mather Campground on the South Rim and the North Rim Campground (mid-May through Oct.). The Desert View Campground (May to mid-Oct.) is first come, first served. Lodging Plan ahead. Reservations in the park at historic Hotel El Tovar and Bright Angel Lodge, plus three modern motels (all in Grand Canyon Village), are handled through Xanterra (grandcanyonlodges.com; 888-297-2757), as are reservations for Phantom Ranch, in the inner canyon. Yavapai Lodge, in Grand Canyon Village, is operated by Delaware North (grandcanyon.com; 877-404-4611.) |

Stella Lake

Nevada

Established October 27, 1986

77,180 acres

Carved by glaciers and dominated by Wheeler Peak, more than 13,000 feet high, remote Great Basin National Park protects landscapes of high-altitude desert valleys, salt flats, and rolling ridges. The lakes reflect rocky scenes; the Lehman Caves brim with palaces; and the night skies dazzle with stars.

The park occupies a portion of the South Snake Range that rose up 30 million years ago when plate tectonics stretched the Earth’s crust, cracking it into parallel faults. These fractures uplifted into 160 mountain ranges. In between are flat basins where precipitation collects in playas (lake beds).

A first impression of the park as just another mountain rising from the desert floor gives way in the face of its wonders, including ancient bristlecone pines and an Ice Age cirque that cradles Nevada’s only glacier.

Early trappers called this part of the mountain range “Starvation Country” and steered clear. Ranching and farming brought settlers to the Snake Valley in the mid-1860s. Miners and prospectors followed.