On the Taggart Lake Trail, Grand Teton National Park

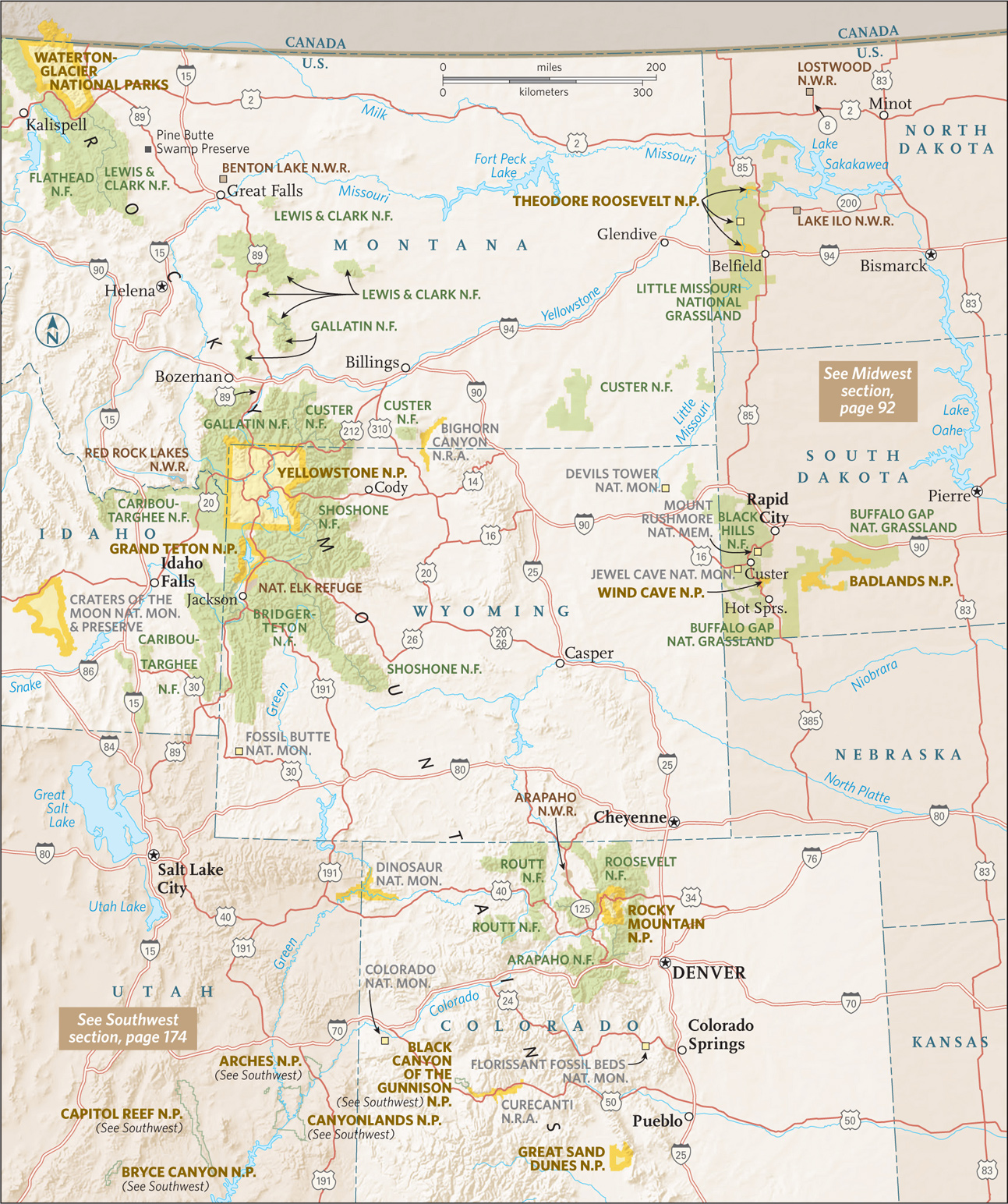

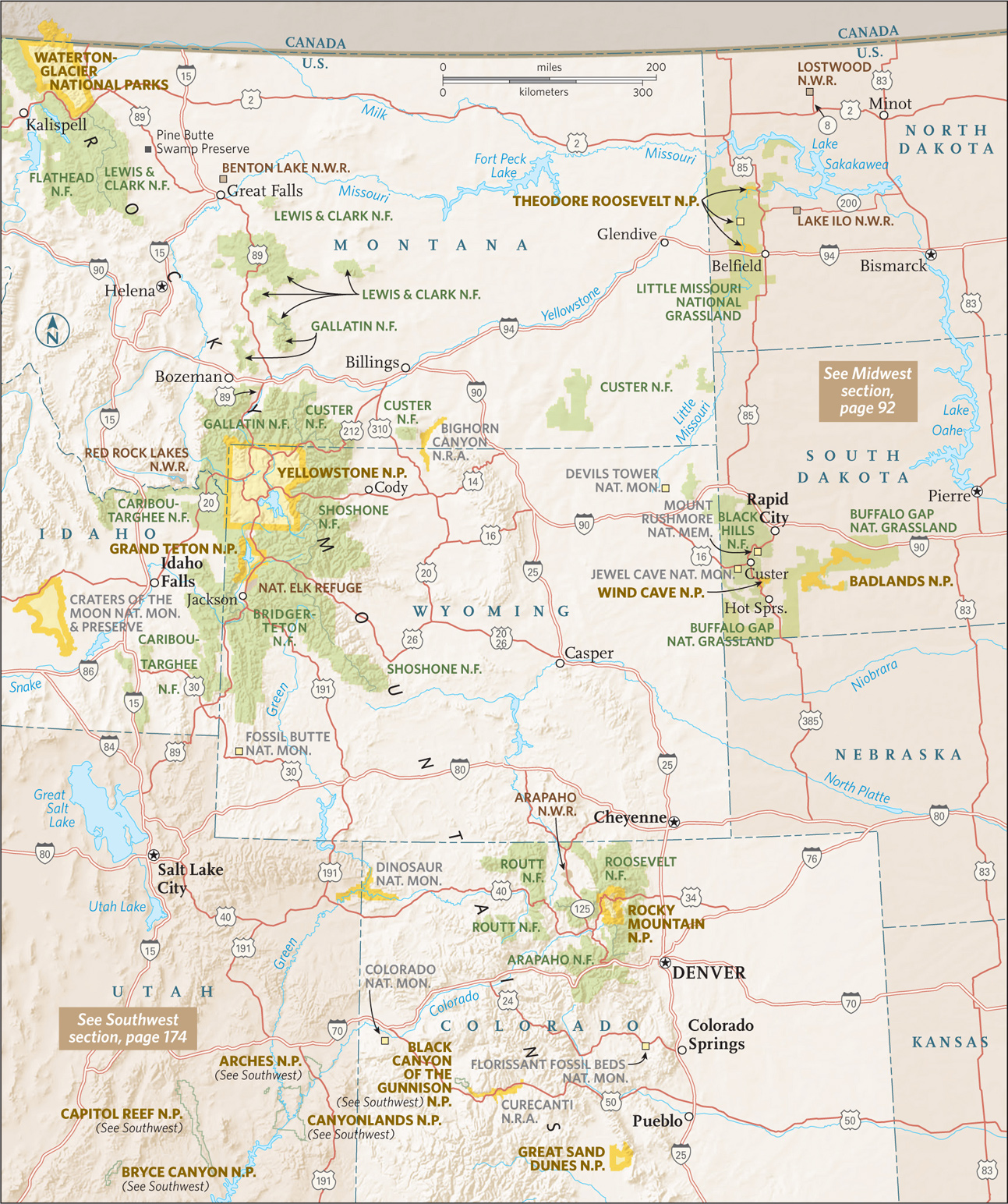

Craggy peaks capped by glimmering glaciers, fields run riot with wildflowers, lakes as smooth and blue as a summer sky—these images from the four Rocky Mountains parks epitomize for many just what a national park should look like.

High alpine landscapes are the common denominator. These five parks—Great Sand Dunes included—soar.

Rocky Mountain National Park’s riches are best viewed along Colorado’s Trail Ridge Road, a 48-mile passage that snakes through the park, ascending among subalpine forests before reaching the alpine tundra, where shrubs and rock-hugging lichen endure the extreme wind and cold.

Yet this region offers more than mountains. The forces that created the peaks further contoured neighboring landscapes. As wind eroded the mountain peaks, dust settled in the San Luis Valley and formed the dunes—some up to 750 feet tall—in southern Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes National Park (where Tijeras Peak tops out at 13,604 feet).

The Rocky Mountain national parks preserve the spirit of America’s frontier, its history, rugged landscapes, and abundance of wildlife. Wyoming’s Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and Montana’s Glacier/Waterton—together with surrounding public lands—remain strongholds for the grizzly bear. In some parks visitors can watch elk, bighorn sheep, mule deer, and remnants of the great bison herds that once thundered across the plains.

These parks provide case studies in how wilderness manages itself. In Yellowstone, for instance, the visitor can get a real sense of natural recovery in the wake of historic forest fires. Less encouraging are the real estate developments and plans for industry on the fringes of some parks. Such activities can shrink the habitats of wide-roaming animals, though in some instances parks are adjusting. The formerly threatened elk around Grand Teton and Yellowstone, for example, now congregate in winter to feed in the nearby National Elk Refuge.

St. Mary Lake

Montana & Alberta, Canada

Established May 11, 1910

1.1 million acres

Ice Age glaciers carved the foundation of a wonderland of soaring cliffs, misty valleys, long lakes, wildflower meadows, and deep forest. Melted snow and ice pour from the heights; cascades and waterfalls appear at nearly every turn. It feels like a landscape freshly minted. And so it is. The glaciers melted scarcely 12,000 years ago. Note: Glacier/Waterton National Park is actually two parks in two countries, joined in 1932 as a symbol of peace and friendship.

Sprawled across the Continental Divide, Glacier has two sides. The west reflects a Pacific Northwest maritime climate, with abundant moisture, big narrow lakes, and lush forest. On the drier east side, where mountains stand like fortress walls above the great plains, the landscape is more open; lodgepole pine, grassy meadows, and aspen trees are common. The Going-to-the-Sun Road cuts a spectacular transect over Logan Pass, going from one side of Glacier to the other.

When the Rockies lifted up about 75 million years ago, a giant slab broke loose and slid toward the east—an event called the Lewis Overthrust. That grand block is the mountainous core of the park.

There are glaciers to be seen, but possibly not for long. Models predict that the glaciers might be gone by 2030 (see here). Yet Glacier was named not so much for living ice as for the tracks of it, the work of Ice Age glaciers over the last two million years. Moraines, hanging valleys, arêtes, cirques, eskers, drumlins, and kames—this is a perfect place to see these glacial landforms.

And the creatures that call this place home? Bighorn sheep, mountain goats, elk, grizzly bears, wolves, and eagles flourish here.

► HOW TO VISIT

Allow plenty of time, a full day if you can, for the 50-mile Going-to-the-Sun Road, considered by many to be one of the world’s most spectacular highways. Ride the free shuttle to avoid fighting traffic and searching for a place to park. Get off at one stop, hike a distance, then get back on at another.

On a second day, travel the Chief Mountain International Highway north to Waterton Lakes to enjoy the contrast of peak and prairie.

With more time, sample one or both sides of Glacier/Waterton. West-side highlights include Lake McDonald, water-sculpted McDonald Creek, and ancient forests of hemlock and red cedar. On the east side, don’t miss Many Glacier, with stunning scenery and the park’s best trails. To the north, Waterton Lakes, in Canada, offers more mountain majesty with fewer visitors.

Want off the beaten path? Go north from Apgar to remote Kintla and Bowman Lakes, or south from St. Mary to Cutbank and Two Medicine Lake.

You can take a wilderness trip on horseback or foot. Sign up for guided horseback rides at the Many Glacier, Lake McDonald, or Apgar visitor centers.

Refurbished vintage White Motor Company park touring bus

Going-to-the-Sun Road

Starting on the west side of the park, get oriented at the Apgar Visitor Center. Note restrictions on vehicle size and bicycle use on higher sections of the road. During peak season (June through September), when traffic is heavy and space at turnouts is limited, the free shuttle is a good option.

The road skirts Lake McDonald, the biggest lake in the park. Its long, narrow bed was gouged out by the bulldozing action of a glacier. Stop at a turnout to admire the view and, lakeside, test your skills with some of the world’s best skipping stones.

Although snowy peaks beckon, linger a while along McDonald Creek. From a turnout just beyond the lake, cross a footbridge and turn upstream to Sacred Dancing Cascade, a quarter mile of tumbling water and polished rock. Several miles farther, stop at Avalanche Creek. Follow Trail of the Cedars (0.7 mile), a boardwalk suitable for wheelchairs that winds through an old forest of towering hemlocks, black cottonwoods, and red cedars, some of them more than 500 years old.

Even during busy times, these extensive, cool, fern-filled spaces convey a sense of timeless peace. Trail of the Cedars leads to Avalanche Gorge, an exquisite natural creation of red rock, turquoise water, and the intoxicating smell of cold mountain mist. The water comes from Avalanche Lake, perched in a cirque 500 feet above.

Soon the road begins to climb and great peaks heave into view. Pause at The Loop, a tight switchback, for views of Heaven Peak and to learn about the Trapper Fire, one of six major fires that burned 135,000 acres in 2003.

A 4-mile trail leads stiffly uphill from here, gaining 2,200 vertical feet before reaching Granite Park Chalet (graniteparkchalet.com; 888-345-2649), one of two back-country lodges remaining from a network built by the Great Northern Railway a century ago.

Another way to get to this part of the park is via the Highline Trail from Logan Pass, which starts high and stays high, leading through meadows that range below a long glacier-sharpened ridge called the Garden Wall. It’s 7.6 miles to Granite Park; from there it’s a short downhill walk back to The Loop.

For the next few miles, the road seems nailed to the cliffs. It bores through tunnels, edges fearlessly around promontories, and passes beneath wispy waterfalls. One of the most famous is across the valley. Bird Woman Falls drops in a long ribbon from a classic hanging valley.

Logan Pass is a place to revel in alpine splendor. Snowcapped peaks rise on all sides. Summer wildflowers are abundant. Mountain goats are usually visible, sometimes at close range. (Keep your distance, as with all wildlife.) Pick up a self-guiding pamphlet at the Logan Pass Visitor Center and follow the 1.5-mile trail to Hidden Lake Overlook, where the ground drops away suddenly to a gorgeous gem of a lake. Or go the other way, along the Highline Trail. Going for even a short walk is rewarding, but note that it involves walking a narrow, exposed ledge that can be disconcerting.

Descending eastward, the road cuts though dark gray rock containing the cabbage-shaped whorls of fossilized algae called stromatolites, The algae lived as slimy colonies along an ocean coast almost a billion years ago. Pull in at Siyeh Bend, a sharp turn close to timberline, to scan the meadows for wildlife.

Grizzly sightings are possible here, beneath sharp-spired Going-to-the-Sun Mountain. Legends attributed to the Blackfeet people describe the mountain as a spirit pathway to the sun; others say the name came from the flowery imagination of an early tourist.

Stop at the Gunsight Pass Trailhead for a fine view of Jackson Glacier. Among the park’s larger glaciers, it’s also one of the few visible from a road. Farther along, waterfall lovers should consider walking to St. Mary and Virginia Falls, near the head of St. Mary Lake, and everyone should stop at Sun Point, for the panoramic vista and a stroll along the self-guided nature trail. Farther down the lake, just west of Rising Sun, pull in at Wild Goose Island Overlook for an iconic view, perhaps the most recognized place in all of Glacier.

The road continues 6 miles along the lakeshore, ending at the St. Mary Visitor Center and entrance. The road climbs gently into what many feel is the heart of the park. A cluster of turquoise lakes lies at the meeting place of three valleys beneath towering peaks. As you arrive at Swiftcurrent Lake, the grandeur can stop you in your tracks. When you’re ready to move on, check out the rustically gracious Many Glacier Hotel, built in 1915 (glaciernationalparklodges.com; 855-733-4622).

More than anything, Many Glacier is a place for hiking. Warm up on the easy 2.5-mile nature trail around the lake, or go beyond it, past Lake Josephine, onto a nearly level trail to Grinnell Lake, gleaming turquoise at the base of massive Mount Gould. Waterfalls pouring off these formidable cliffs are fed by Grinnell Glacier. Strong hikers can join a ranger for an all-day hike to the glacier overlook.

Other places in the hiker’s Many Glacier treasure kit include Iceberg Lake, dotted with floes, high against the Garden Wall (a 4-mile hike, 1,200 feet up); for a nearly level valley-bottom walk, consider Red Rock Falls (3.6 miles, 100 feet up).

Chief Mountain Highway & Beyond

From the town of Babb, the 29-mile Chief Mountain International Highway climbs over rolling hills toward Chief Mountain (9,080 feet), a distinctive monolith marking the easternmost push of the Lewis Overthrust. Shoved into position on top of younger strata, the mountain is older than the rocks beneath it. Chief Mountain has long been sacred to the Blackfeet people.

U.S. and Canada customs stations flank the international border. (All travelers must present passports or other documents compliant with the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative.) A few miles north, sweeping views of the Waterton Valley open up. Prominent is Mount Crandell, embraced by the park’s two major valleys, Blakiston and Cameron. Ahead and eastward, the open plains stretch seemingly forever. The scenic climax, Upper Waterton Lake, waits in the wings, stage left.

It’s a good idea to stop at the Waterton Lakes National Park Visitor Centre for maps and park information. From here, a short steep hike climbs Bear’s Hump for a grand overview of Waterton Lake.

There’s an easier-to-access viewing area just across the road at the imposing Prince of Wales Hotel (glacierparkinc.com; 406-892-2525). Perched boldly on a treeless knob at the end of the lake, the hotel is famous for strong winds, period design, afternoon tea Victorian style, and jaw-dropping scenery.

To see more of the lake, take a boat ride to Goat Haunt, a ranger station on the American side of the border (glacierparkinc.com; 406-892-2525). Otherwise, drive the Red Rock Parkway through Blakiston Valley. Stop at the first oil well in western Canada, where drillers struck oil in 1902. Fortunately for the future national park, the oil soon played out and the area returned to its wild state. The road ends at a narrow redrock gorge that has been beautifully sculpted by mountain water.

The Akamina Parkway begins at Waterton Townsite and follows a glacial valley through woods and meadow for 10 miles to Cameron Lake, cupped high among snowcapped peaks near timberline. Rent a canoe, walk the lakeshore trail, or mosey through the forest to moose-frequented Akamina Lake. Robust hikers have numerous options. The trail to Summit Lake climbs 1,000 feet in 4 miles. Make a full day in the high country by continuing all the way back to Waterton Townsite via Carthew and Alderson Lakes, a total distance of 12 miles.

Other Sights & Trails

The quiet northwest corner of Glacier features several lakes that rival Lake McDonald for splendor. The bonus is that they receive very few visitors. Follow the North Fork Flathead River through forest and meadow. The river occupies a rift torn open when the mountains slid eastward on the Lewis Overthrust. At Polebridge, drop in at the Mercantile, a century-old general store outside the park. Continue to Bowman Lake or Kintla Lake, fine places to pitch a tent. Indeed, this is a place to linger, especially if you have a canoe or kayak.

The opposite corner of the park, the southeast, is also less traveled. Follow US 89 from St. Mary, then Mont. 49 to Two Medicine. A boat shuttle crosses Two Medicine Lake, another long glacial trough. From the far end, a 2.2-mile trail skirts a distinctive spire called Pumpelly Pillar and ends at Upper Two Medicine Lake surrounded by colorful cliffs.

Information

|

How to Get There US 89 connects to east-side Many Glacier and St. Mary. US 2 cuts around the south end of the park and is the main approach from the west. In Canada, Alberta 6 and 5 approach from the north and east. When to Go June through September is best. Access to the park is reduced in early spring and late fall due to weather. Main roads are open year-round. Logan Pass is usually not clear until mid-June. Chief Mountain Highway is open early May–Sept. Lodging Xanterra (glaciernationalparklodges.com; 855-733-4522) runs five hotels, including Many Glacier and Lake McDonald; lodging is also available from Glacier Park Inc. (glacierparkinc.com, 406-892-2525). For backcountry lodges contact Belton Chalets (graniteparkchalet.com, 888-345-2649). Waterton Townsite offers a variety of options (mywaterton.ca/stay, 403-859-2224). |

Headquarters Glacier National Park Waterton Lakes National Park Camping Most of Glacier’s 13 campgrounds open late May or early June. Reservations available for limited sites at St. Mary and Fish Creek (recreation.gov). Waterton Lakes has three campgrounds (pccamping.ca). Visitor Centers Glacier’s three visitor centers (at Apgar, St. Mary, and Logan Pass) have varying schedules but are generally open May to mid-Sept. On the Canada side the Waterton Lakes Visitor Centre is open mid-May–mid.-Oct. |

Snake River and the Teton Range

Wyoming

Established February 26, 1929

310,000 acres

If we imagine what mountains should look like, these are the ones. Snowcapped crags sharpened by glaciers rise abruptly above the sage-covered plain of Grand Teton National Park. A chain of alpine lakes filled with trout sparkles at their feet, while the Snake River winds smooth and fast through tree-lined channels. A gentler range stands to the east; together with the Tetons it encloses the valley called Jackson Hole.

Grand Teton National Park is named for a single mountain, the Grand Teton, 13,770 feet high and the central summit of the Teton Range. It forms, with its immediate neighbors to the south, a sort of alpine triumvirate, the Three Tetons. These mountains and others in the range were called Pilot Knobs by fur trappers some 200 years ago because they could be seen from miles away, in all directions. Other notable peaks include Teewinot, an elegantly descriptive Shoshone term that means “many pinnacles.”

Beyond spectacular scenery, the Tetons possess everything a mountain landscape should have. Abundant wildlife includes moose, elk, bison, deer, antelope, bighorn sheep, grizzly and black bears, beavers, otters, eagles, and osprey. Vegetation varies with altitude. Sagebrush and cottonwoods thrive on the valley floor. Spruce, pine, and aspen trees climb the mountain slopes. Alpine meadows strewn with wildflowers like spilled treasure occupy the heights. Waterfalls, glacial lakes, a dozen glaciers, and numerous mountain creeks complete the scene.

► HOW TO VISIT

If you have one day, drive the Teton Park Road. Start with the visitor center at Moose, then drive north to the Jenny Lake area, stopping for short walks and to pause at scenic viewpoints. Make a loop of it by continuing to Jackson Lake and returning to Moose via Moran Junction.

On a second day, hike to one of the morainal lakes—Bradley, Taggart, Leigh, or Phelps. For longer hikes, consider the canyons—Cascade, Death, Granite, and others. Float the Snake River, or rent a canoe at Colter Bay and explore the islands in Jackson Lake.

Two Ocean Lake

Teton Park Road & Jenny Lake

Driving north from the town of Jackson, turn off US 89/191/26 at Moose Junction. Drive slowly across the Snake River Bridge, checking the riverside willow thicket for moose. Stop at the visitor center at Moose for general information, a bookstore, a theater, and exhibits on park history and nature. The entrance station is just ahead; from there, the Teton Park Road climbs up from the river bottom to emerge on a wide, sage-covered expanse. Suddenly the whole range rockets into view, seeming impossibly steep and high. The mountains will stay close for the rest of the drive, with each mile bringing a new and perhaps even more spectacular perspective.

At Taggart Lake Trailhead, a popular 3-mile trail leads to Taggart Lake and, beyond it, Bradley Lake. The route passes over a glacial moraine. This is typical of lakes at the base of the Tetons. Glaciers, pushing down from the mountains, gouged out the lake basins and left piles of debris that held back the waters. This moraine, visible from the road, burned in a 1985 wildfire. You can see how long it takes for a forest to recover in this slow-growing mountain setting.

Pause at Teton Glacier Turnout for a neck-craning view of the central peaks. The Grand Teton (13,770 feet) is the highest in the range and second highest in Wyoming (behind Gannett Peak in the Wind River Range). Shouldering against it on the left (south) is the Middle Teton. The South Teton, third of what French trappers called Les Trois Tétons, can’t be seen from this angle. A foreground peak, Nez Perce, blocks it from view.

To the right of the Grand [Teton] are sharp-pointed Mount Owen and Teewinot Mountain. Of the many climbing routes up the Grand, not one is easy; the main route follows the left-hand skyline. Before noon, hikers might be visible on the summit, which is more than 7,000 vertical feet above.

Glacier Gulch is a smooth stone trench plowed by large tongues of ice that spilled from the mountains during glacial periods, when ice covered the mountains and parts of the valley to depths of several thousand feet. (The most recent glaciation ended some 14,000 years ago.)

The small Teton Glacier shelters in the cold shade of the Grand Teton’s formidable east face. How can you tell glaciers from the numerous snowfields scattered over the Tetons? Snowfields are generally whiter. Glaciers might be covered by fresh snowpack from last winter’s snowfall, but the ice can be centuries old. The ice shows its age; it is gray, like elephant hide, broken by crevasses as the snowpack melts under the summer sun.

Across the road to the east stands Timbered Island, a moraine that demonstrates why plants grow in some areas here and not others. Moraines form at the feet of glaciers and contain a jumbled mix of silt, gravel, and rock. The silt holds moisture, which in turn supports dense forest. In contrast, much of the valley floor is an outwash plain: gravel and rock deposited by glacial meltwater, with not as much silt. Water sinks beneath the plain, and trees don’t survive in this arid environment. Instead, deeply rooted sagebrush covers the ground.

Driving north, look for pronghorn on the sage slats east and north of Timbered Island. Resembling African antelope but actually a separate family, pronghorn are North America’s fastest land animals. Elk, deer, and coyote sightings also are possible.

Just south of Jenny Lake, a road cuts off to Lupine Meadows and a popular trailhead. Climbers headed for the standard routes up the Grand start here. Hikers branch off to Amphitheater Lake, a stiff climb of 3,000 feet, and just about the closest you can get to the Grand without climbing it. Put that on the day-hike list, and for now continue past South Jenny Lake for 3 miles to North Jenny Lake Junction.

The Cathedral Group Turnout might slow you down with its view of crags piled upon crags. From here, Teewinot seems a more fitting name than Teton (French for breast or nipple).

If you are inclined to do some easy walking, you can’t beat the trail along narrow String Lake, with its beaches, shady rest stops, water sometimes warm enough for swimming, and stupendous views.

The nearly level trail continues to Leigh Lake. Deep blue, under the soaring walls of Mount Moran, it was named for “Beaver Dick” Leigh, a British fur trapper who arrived in the area with his Shoshone wife, Jenny, in the 1860s. He lost her and their children to smallpox in 1876. She is remembered by the lake that bears her name.

Continue south on the one-way road along the shore of Jenny Lake. The South Jenny Lake area (visitor center, store, and ranger station) is the place to park for shuttle boats that provide transport to the half-mile, often crowded trail to Hidden Falls. That trail continues to Inspiration Point, offering a fine view of the lake before entering the delightful gorge of Cascade Canyon, one of the park’s premier hiking routes. Add that to the growing day-hike list.

Jackson Lake & North

Start at North Jenny Lake Junction on the Teton Park Road. Well-placed turnouts offer splendid views, with Mount Moran becoming more center stage as you head north. Two prominent glaciers cling to its precipitous flanks, Falling Ice Glacier, on the left, and Skillet, on the right. Skillet’s summit looks flat, like a plateau, but it drops off steeply on the back side.

In the right light, you can see a reddish patch of sandstone on the very top of Skillet, a small remnant of the sedimentary layers that once overlay the entire range. The remnant corresponds to a layer of the same stone now some 24,000 feet beneath the valley floor. Those two layers tell the story of the Teton uplift. Two giant blocks of stone shifted along the Teton Fault. The valley block tilted downward as the mountain block rose, for a total displacement of some 30,000 vertical feet, all in 13 million years or less.

If you’re not driving an RV or pulling a trailer, take the turn for Signal Mountain. A narrow road winds to the summit. Because it stands by itself, the mountain provides unmatched views of the entire Teton Range, the valley, and the gentler Gros Ventre Range, which bounds Jackson Hole on the east. This is a fine place to appreciate the big picture of Grand Teton’s dramatic geology.

Returning to the Teton Park Road, continue along the shore of Jackson Lake and across the Jackson Lake Dam. Constructed in 1907, 22 years before the park was established, and rebuilt several times after, the dam raised the natural lake level by 39 feet. The stored water irrigates farm fields in Idaho.

Past the dam, watch for moose that frequent the willow flats. The Teton Park Road ends just ahead, where it meets Wyo. 26/287. Turning left takes you past Jackson Lake Lodge, on the road to Yellowstone, but even if you’re headed that way, take a short detour to the right.

One mile away is Oxbow Bend, a wide meander of the Snake River flowing gently through marshy flats. In the autumn, bright yellow aspens frame this famous view of Mount Moran across calm water often crowded with ducks, geese, and sometimes American white pelicans.

If headed to Yellowstone, go north. For about 15 miles, the road follows the shore of Jackson Lake, which comes in and out of view through forest and across meadows that in summer become lavish spreads of wildflowers. Stop at Colter Bay to enjoy the waterfront. Long pebble-covered beaches stretch in both directions, with dramatic views of Mount Moran and the remote peaks of the northern Tetons.

Rolling Thunder Mountain, Eagles Rest Peak, and Ranger Peak dominate the wildest section of the park, an area with no roads and no maintained trails, protected on one side by the lake and on the other by miles of wilderness.

Colter Bay is a prime locale for paddling. Along the intricate shoreline, between the marina and Sheffield Island is ideal for exploring in a canoe or small boat.

To close the circle back to Moose, continue east through the Moran Entrance to Moran Junction, then south on Wyo. 89/191/26. A stop at Cunningham Cabin Historic Site offers a glimpse of pioneer life in Jackson Hole.

Here, in 1888, John and Margaret Cunningham started the Bar Flying U Ranch, a beautiful but challenging place to live. Long winters, deep snow, and summer drought prompted the Cunninghams, like many of their neighbors, to sell their land. They left in the 1930s.

Don’t miss Snake River Overlook, where landscape photographer Ansel Adams made perhaps the most famous picture of the Tetons, with the river curving beneath high forested banks toward the central peaks. You might see rafts and small boats on the Snake River, carrying anglers and sightseers. Eagles and osprey are common sights here.

Several more turnouts command attention as you drive south. If there’s time for a short stroll, take the side road to Schwabacher Landing, braided river channels and beaver dams create a wildlife-rich mix of wetlands, reflecting ponds, meadows, and cool cottonwood forest.

Sunset can be lovely here. Sunrise, when first light hits the peaks, often is unforgettable. Four miles south is Moose Junction.

Jackson Lake and the Teton Range

Other Hikes & Activities

Grand Teton is a hiker’s park, and not all the trails are steep. Ambitious hikers might set off from Lupine Meadows for Amphitheater Lake. It’s a 3,000-foot climb through steep wildflower meadows, with views into the cirque that holds Teton Glacier. Or consider a hike in one of the canyons that separate the major peaks. Cascade Canyon is deservedly popular.

Shorten the hike by riding the shuttle boat across Jenny Lake. Lake Solitude (7.4 miles from the shuttle dock), on the back side of the Grand Teton, is the most popular shuttle boat landing.

Death Canyon is far more appealing than its name would suggest. The trail starts off the Moose-Wilson Road. One mile takes you to a fine overlook of Phelps Lake, then down to the lake and up the canyon as far as you wish to go. With overnight gear (backcountry permit required), you can join the Teton Crest Trail, a dazzling high traverse on the other side of the range.

For easier walking, consider one of the lakeside trails around Colter Bay area, which lead to gravel beaches on Jackson Lake. Hermitage Point is about 4.5 miles each way, depending on the route you choose. Or pick a segment of the little-traveled Valley Trail that stretches from Teton Village along the base of the mountains to Jenny Lake.

The Laurance S. Rockefeller Preserve, located on the Moose-Wilson Road, was recently opened to the public after Laurance S. Rockefeller donated the private retreat to the park. The visitor center and trail system were designed to encourage reflective nature appreciation. An easy 3-mile loop follows Lake Creek to a perfect picnic site on Phelps Lake. These trails connect with the Death Canyon Trail.

Floating the Snake River is a relaxing half-day experience. The scenic river, fast-moving but with no white water, offers shifting views of the mountains and a chance to see eagles, osprey, moose, otters, and other wildlife. Guided fishing trips are also popular. Or take to the pedals; a paved multi-use path runs from Jackson to Jenny Lake, along with multiple side-road options throughout the valley.

For a quiet, out-of-the-way driving option, consider the east side of the valley. Drive along the Gros Ventre River to the hamlet of Kelly, then loop north and west, watching for bison and moose, to Mormon Row, once home to 22 Mormon pioneer families. The graceful old Moulton Barn, at sunrise with the mountains in the background, has become a Teton classic for painters and photographers.

Nearby, the Gros Ventre Road climbs rolling foothills eastward to Slide Lake, created in 1925 by an enormous landslide that dammed the river. When the impounded water broke the dam two years later, the sudden flood wiped away the town of Kelly, killing six people.

Information

|

How to Get There From Jackson, drive north on US 89/26/191 to the main visitor center and entrance station at Moose. From Yellowstone, US 89/287 enters the park via John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Pkwy. Jackson Hole Airport is in the park. When to Go July and Aug. see peak visitation. Wildflowers are abundant. Afternoon thunderstorms keep things fresh. Roads are plowed usually by early May, with snow lingering into June. Sept. and Oct. bring lots of sun, frosty nights, and good wildlife viewing. Winter is as beautiful as it is challenging. Snow falls deep and temperatures drop into the sub-zero range. It’s the time for cross-country skiing and snowshoeing. Most of Teton Park Road and Moose-Wilson Road close for the season. Headquarters P.O. Drawer 170 |

Camping The park has five campgrounds; most open early to mid-May and close early to mid Oct. Backcountry camping is also an option; permits are offered on a first-come, first-served basis. Lodging In the park, Grand Teton Lodge Company runs Jackson Lake Lodge, Jenny Lake Lodge, and Colter Bay Cabins (gltc.com; 307-543-2811). Many lodging options exist in and around Jackson (jacksonholechamber.com; 307-733-3316). Visitor Centers There are five visitor centers: Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center, at Moose, open daily March through Oct.; Jenny Lake, mid-May to late Sept.; Colter Bay, mid-May through Sept.; Laurance Rockefeller Preserve, June to late Sept.; Flagg Ranch, June through Aug. |

Jackson, Wyoming

▷ The National Elk Refuge preserves, restores, and manages winter habitat for the Jackson elk herd. It also protects endangered birds. In winter, horse-drawn sleighs take visitors around the refuge. Fishing Aug. through Oct. (Wyoming fishing license required). Located northeast of Jackson, Wyoming, and directly south of Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. US highways 26/191 pass through Jackson and 6 miles into refuge land. fws.gov/nationalelkrefuge; 307-733-9212.

East of Jackson, Wyoming

▷ One of the three wilderness areas located within the Bridger-Teton National Forest, Gros Ventre Wilderness is known for its wildlife—bighorn sheep, elk, deer, black bears, wolves, grizzly bears, mountain lions, and bison—as well as its rocky alpine peaks. It provides excellent chances for both backpacking and horseback trips. Located east of Jackson, Wyoming, and southeast of Grand Teton National Park. fs.usda.gov/recarea/btnf/recreation/ohv/recarea/?recid=71647&actid=30; 307-739–5500.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway

Between Yellowstone and Grand Teton NPs

▷ Linking two of the nations’ greatest national parks, the Parkway runs the 82 miles between Grand Teton and Yellowstone. Set aside as a scenic corridor, this route runs through a gently rolling track of lodgepole pines. Off the sides of the road are elk, moose, and deer. The Snake River crossing provides a chance to both picnic and launch a canoe, while the Grassy Lake Road provides a scenic drive into Idaho. nps.gov/grte/jodr; 307-739-3300.

Jackson National Fish Hatchery

Northeast of Jackson, Wyoming

▷ On the grounds of the National Elk Refuge, the Jackson National Fish Hatchery has been raising fish to mitigate fish losses since the middle of the last century. The fish reared here are native Snake River cutthroat trout, which are reintroduced into the waters of Wyoming and Idaho. Sleeping Indian Pond is open for fishing to those with their own equipment (Wyoming license required). Located northeast of Jackson, Wyoming, and south of Grand Teton National Park. fws.gov/jackson; 307-733-2510.

Dubois, Wyoming

▷ The National Bighorn Sheep Center zooms in on the biology and habitat needs of the wild sheep. The center features dioramas that re-create the habitat of the large wild sheep, interactive exhibits about wildlife management, and wildlife films. In fall and winter, the center offers guided and self-guided tours of the local Whiskey Mountain herd in their natural habitat. Center closed Sun. in winter. Fee. Located in Dubois, Wyoming, 55 miles southeast of Grand Teton National Park via US 26E/US 287. bighorn.org; 307-455-3429.

Fossil Butte National Monument

Kemmer, Wyoming

▷ Fifty-two million years ago, this semi-arid sagebrush country was the site of Fossil Lake, a rich freshwater Eocene deposit that became a place of fossils, exquisitely preserved freshwater fish. More than 300 fossils are on display at the Visitor Center. Summer activities include fossil preparation demonstrations and exhibit tours. Interpretive trails, a scenic drive, winter snowshoeing, and cross-country skiing round things out. Visitor Center open year-round. Located about 180 miles south of Grand Teton National Park off US 30. nps.gov/fobu; 307-877-4455.

Dunes and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains

Colorado

Established September 13, 2004

149,137 acres

Undulating sweeps of sand—the tallest sand dunes in North America—rise precipitously and improbably from the rolling grasslands of the San Luis Valley in mountainous south-central Colorado. Craggy spires of the Sangre de Cristo range soar directly behind the dunes, reaching skyward more than 13,000 feet. A coalescence of grass, sand, water, forest, and rock forms the visually striking ecosystem that is Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve.

The dunefield of Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve sprawls across more than 30 square miles. At its highest point is Star Dune, towering 755 feet above the surrounding grasslands. Today, visitors from around the world come to visit the magical realm of the dunes.

Some 11,000 years ago, the Clovis people, nomadic hunters and gatherers, roamed the region, hunting the herds of mammoths and prehistoric bison that grazed here. Later, the modern Ute and Jicarilla Apache tribes annually migrated through the area, also hunting and gathering. They collected the inner bark from ponderosa pines for food and medicine; more than 100 ponderosa pines in the park today still show evidence of bark-peeling.

Beginning in the 1600s Spanish explorers from settlements in New Mexico penetrated the region. Legend has it that a dying priest, Francisco Torres, mortally wounded by an arrow, uttered his last words as he looked up at the sunset-burnished mountains above the dunes: “Sangre de Cristo … Sangre de Cristo,” or Blood of Christ, thus giving the name to the mountain range towering above the dunes.

The first American to visit the Great Sand Dunes, it is believed, was Zebulon Pike, who in 1807 crossed the Sangre de Cristo Mountains from the east and was astonished by what he saw; in his journal he wrote of the dunes, “Their appearance was exactly that of a sea in a storm.” By the late 1800s, settlers and miners populated the San Luis Valley and western flank of the Sangre de Cristos. In the 1920s, mining firms contemplated but never acted upon the idea of processing the sands of the Great Sand Dunes for gold.

Concerned about the possible destruction of the dunes, local residents petitioned Congress to protect them. In 1932, President Herbert Hoover signed a bill creating the Great Sand Dunes National Monument.

In 2000, 41,686 acres east and northeast of the dunefield were added, creating the national preserve, and the boundary was also expanded to the west to take in an additional 69,240 acres of sand deposits. By 2004, a large portion of these lands had been acquired by the U.S. government.

Winds that can top 40 miles an hour reshaped the crests of the tall dunes, and smaller dunes may “migrate” several feet in a week.

The region’s geology and biology make Great Sand Dunes a fascinating place, unique among America’s national parks.

► HOW TO VISIT

The Dunefield is the highlight of any visit to Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve. Climbing, sliding, rolling, sandboarding, and sand sledding in the dunes is a unique experience. If your time is very limited, plan on a half-day visit that includes an hour at the visitor center and a few hours in the dunes themselves.

A full day or two, however, allows for a more fulfilling exploration of the park. You’ll have time, for one, to experience Medano Creek area, wonderful for children who enjoy playing in wet sand. Broad and shallow, Medano Creek flows along the east side of the dunes.

Several hiking trails climb high into the forests and peaks of the Sangre de Cristos. The 0.5-mile Montville Nature Trail and 3.5-mile Mosca Pass Trail climb into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and offer a skyscraping counterpoint to navigating the great dunes below.

If you have a high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicle and a strong sense of adventure, consider driving the Medano Pass Primitive Road. It heads to the crest of the Sangre de Cristos at Medano Pass, an elevation of 9,982 feet. The trailhead for the 3.8-mile Medano Lake Trail is along this road.

The Dunefield & Medano Creek

Enter the park and drive a couple of miles to the visitor center, which features a 20-minute video on the region’s geology and history, interactive exhibits, displays, a bookstore, and rangers to answer questions and provide information. In summer, check the schedule of ranger-led hikes and programs; these offer excellent, in-depth perspectives on various aspects of the park.

The 0.25-mile Sand Sheet Loop Trail through the grasslands starts and ends at the visitor center and offers a quick introduction to the park. Note the vegetation, including gooseberry and three-leaf sumac bushes, as well as prickly pear cactus.

A mile north is the Dunes parking lot and picnic area, as well as the gateway to hiking and playing in the dunefield. Before reaching the base of the dunes, cross shallow Medano Creek, which borders the eastern edge of the dunefield. Children love to frolic in the creek, building sand castles and digging in the wet sand that forms the creek’s shifting bottom. Medano Creek, fed by snowmelt from the Sangre de Cristos, reaches its peak flow in late May. Early morning is a particularly good time to look for tracks in the wet sand—mule deer, coyotes, or even a bobcat.

A peculiar characteristic of the creek is the existence of “surge flows,” sudden waves of water that sweep downstream. Medano Creek is one of only three or four waterways in the world that have surge flows; some experts believe that Medano Creek offers the best example. Surge flows are created by “antidunes,” sand that builds up on the creek bottom, making dune-like formations. In time, the force of the current collapses the antidunes, and the previously impeded water surges downstream in a wave. During high water in the spring, these surges can occur every few minutes.

A short walk on a sandy flat brings visitors to the base of the dunefield. A target of many hikers is High Dune, at 650 feet the highest point on the dune front visible from the ground. At 755 feet, Star Dune, nearly a mile west of High Dune, is the highest point in the dunefield.

High Dune looks enticingly close, but beware: Hiking in the dunefield is demanding and frustrating. With each upward step, you plunge into the sand a couple of inches and slide backward, so progress can be maddeningly slow. Also, at 8,053 feet, the air is much thinner than many people are used to, so breathing can be difficult. Finally, what looks like a straight uphill climb from the bottom is actually a series of dunes; you labor up a steep slope of sand, and suddenly it drops precipitously back to almost the level at which you started the climb. But despite these challenges, a climb into the dunefield offers a unique physical experience, and the sweeping views from High Dune and Star Dune are spectacular.

Of course many people simply want to play in the sand: jumping off a dune, rolling to the bottom, and climbing back to do it all again. Sandboarding (the equivalent of snowboarding on sand) and sand sledding down dune slopes are also popular activities. Sandboards and sand sleds can be rented from the Oasis Store (719-378-2222), a mile south, at the park boundary on Colo. 150.

Early mornings and evenings are ideal times to be on the dunes. The temperature is pleasant, the slanting sunlight creates a pageant of ever-changing shadows, and you might see a Great Sand Dunes tiger beetle—or at least its skittery tracks. This beetle is one of seven insects found only in Great Sand Dunes.

Park officials warn that the summer sun can heat the dune sand to 140°F, too hot for bare or sandaled feet (the park recommends wearing ankle boots).

View from the summit of High Dune

East of the Dunes

Just north of the visitor center you’ll find the trailhead for three trails that climb into the foothills and heights of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Here you’ll hike through forests of Douglas fir, juniper, and piñon pine, and possibly see mule deer among the trees and goshawks drifting above on thermals.

The half-mile Montville Nature Trail winds along burbling Mosca Creek and introduces some interesting human history. A few hundred yards up the trail is the site of Montville, a small town with a post office that dates back to the 1880s.

An early settler named Frank Hastigs built a toll road over Mosca Pass, a low point in the Sangre de Cristos that had served as a passageway through the mountains for centuries. A flash flood in 1911 wiped out the town of Montville.

The 3.5-mile Mosca Pass Trail follows Mosca Creek to the top of Mosca Pass, at an elevation of 9,737 feet. The 1-mile Wellington Ditch Trail heads north along an old ditch dug by early settlers to channel water north from Mosca Creek; this trail ends at the Piñon Flats Campground.

From the campground, a rutted one-lane dirt road leads to the Point of No Return, the beginning of the 11-mile Medano Pass Primitive Road. This route requires a high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicle—and some determination. It winds along the edge of the dunefield, crossing stretches of sand that may require deflating tires to 15 psi, then re-inflating them to ford streams and wind uphill on a rocky roadbed to the top of 9,982-foot-high Medano Pass.

Just short of the pass is the trailhead for the Medano Lake Trail that climbs 1,900 feet in 4 miles and ends at sparkling Medano Lake, which lies just below Mount Herard, at 13,297 feet the second highest point in the park. Tijeras Point, 13,604 feet, just north of Medano Lake, is the highest.

Information

|

How to Get There US 160 runs east–west through southern Colorado. From Walsenburg (at the junction with I-25) follow US 160 west for 59 miles to Colo. 150. Head north on Colo. 150 for 16 miles to the park entrance. From Alamosa, follow US 160 east for 14 miles and turn north on Colo. 150. Camping The park has three campgrounds (176 sites total). In addition there are 18 roadside camping sites along the Medano Creek Primitive Road accessible only by high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicles. Backcountry camping is permitted; information and permits can be obtained at the visitor center. Lodging There are no lodging options in the park. The Great Sand Dunes Lodge (gsdlodge.com; 719-378-2900) is a mile south of the park entrance on CO 150. The nearest town is Alamosa (alamosa.org), about 30 miles southwest of the park on Colo. 160. |

When to Go The park is open year-round. Spring weather ranges from mild and sunny to snowy and windy. The flow in Medano Creek peaks in late May. Summer has warm days and cool nights. Late summer can bring afternoon thunderstorms. Fall colors peak in late Sept. or early Oct. Winter days are chilly and often sunny. Snow decks the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and sometime blankets the dunes, creating a stunning landscape. Visitor Center The Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Visitor Center is just a couple of miles inside the park boundary. Headquarters 11500 Highway 150 |

Hallet Peak

Colorado

Established January 26, 1915

265,795 acres

For as long as Earth has been home to people and mountains, we’ve looked up with wonder at the grandeur of distant summits. The peaks of Rocky Mountain National Park offer fine examples of this sort of inspiration, with this exception: Here, wonder is replaced by immersion. Few places make it so easy to traverse a true alpine environment.

The park’s renowned Trail Ridge Road reaches an elevation of 12,183 feet, crossing the Continental Divide on its 48-mile route across the park. The road climbs from woodlands and meadows to wind for miles through a stark terrain of rock and tundra. Overlooks provide panoramas of some of Colorado’s most spectacular landscapes, with rugged peaks rising above glacier-carved valleys and forested foothills. The park encompasses more than 77 mountains above 12,000 feet, including the park’s highest point, 14,259-foot Longs Peak.

Though some rock formations in the park date back some 1.8 billion years, the current Rocky Mountains began to take shape about 75 million years ago. Movement of tectonic plates pushed up a broad plateau, later eroded by rivers and weathering. Around two million years ago, periods of glaciation carved mountainsides; moving ice created U-shaped valleys and pushed up piles of rock debris. When the ice melted, the rock piles were left behind as long ridges called moraines, which can be seen throughout lower areas of the park.

The first humans entered the area about 11,000 years ago. Later, Ute Indians hunted and camped here, moving with the seasons and blazing trails over the Continental Divide.

By the beginning of the 20th century, as the conservation ethic gained force in the United States, many local residents called for a park designation to protect the Colorado Rockies.

The scenery of the Colorado high country alone—its lakes, waterfalls, and wildflower-spangled meadows—could explain why Rocky Mountain ranks among the most visited national parks, but it’s also one of the finest wildlife-watching areas. Elk, bighorn sheep, moose, and mule deer are easily spotted; mountain lions and black bears are seen by only a lucky few. Nearly 300 species of birds have been spotted within the park.

Every season has its appeal here, but fall is a favorite time for many visitors. On a crisp September day, when the aspens are turning golden and the first snow dusts the highest peaks, it’s hard to imagine a more appealing and rewarding place.

► HOW TO VISIT

A one- or two-day visit should include the 48-mile drive across the park on Trail Ridge Road, stopping at scenic overlooks and the Alpine Visitor Center. Bear Lake Road is another must-travel route; in summer, avoid traffic and parking issues by taking the free shuttle bus. The road provides access to easy strolls around Bear Lake and Sprague Lake and the short hike to Alberta Falls.

A ranger can help you choose a hike along one of dozens of trails, with destinations ranging from waterfalls to mountain peaks. Dream Lake, Mills Lake, and The Loch pack grand scenery into moderately strenuous hikes; the walk to Cub Lake is great for wildlife and wildflowers. In summer, visit Sheep Lakes to see bighorn sheep; elk are usually easier to see in fall.

Horseback riding has long been a popular way to enjoy Rocky Mountain National Park; around 260 miles of trails are open to horses. Two stables are located in the park (sombrero.com), and several outfitters outside the park offer trail rides.

With many popular lakes and trails located near the tourist town of Estes Park, the central section of the park east of the Continental Divide gets the great majority of visitation. Because Rocky Mountain is one of our most popular parks, it’s important in the peak summer season to get out early.

From Estes Park, US 36 and US 34 access the park and later meet; US 34 becomes Trail Ridge Road. Stop at a visitor center—Beaver Meadows (US 36) or Fall River (US 34)—as you enter the park. The US 36 route passes the turn for Bear Lake Road, which leads to campgrounds, waterfalls, lakes, and trails. The US 34 route passes through Horseshoe Park, which sometimes offers a chance in summer to watch the bighorn sheep that congregate at a natural mineral lick. Rangers and volunteers are present seasonally at Sheep Lakes to assist the crowds that arrive to see the animals. In fall, Horseshoe Park is one of several places in the park where elk (and elk-watchers) congregate at dusk.

Nearby is Old Fall River Road, a winding, unpaved, 9.4-mile route with many switchbacks and fabulous vistas. The road was seriously damaged by flooding in 2013 but has since been rebuilt. This is a one-way route, so once you start you’re committed to reaching the top. Old Fall River Road has a speed limit of 15 mph, and vehicles over 25 feet and trailers are not permitted.

US 34 and US 36 meet at Deer Ridge Junction, with US 34 continuing as Trail Ridge Road. Note: The route reaches a challenging elevation of 12,183 feet, and lightning can be a real danger when thunderstorms form on summer afternoons.

As you ascend through forests of ponderosa pine into Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir, overlooks such as Many Parks Curve and Rainbow Curve provide spectacular panoramas of mountains and valleys. Past Rainbow Curve, the road climbs into the alpine world above tree line. At Forest Canyon Overlook you’ll see the way glaciers cut a U-shaped valley as they advanced. Stop at the Rock Cut parking area to walk a short trail that shows how flora survive this harsh environment, covered by snow for eight months of the year.

At the Alpine Visitor Center you’ll learn about the ecology of the tundra, home to animals such as yellow-bellied marmots, pocket gophers, and white-tailed ptarmigans. Past the visitor center, Trail Ridge Road descends beyond the Continental Divide to reach destinations on the park’s west side. (see here).

North American elk

Bear Lake Road winds 12.5 miles south and west from US 36, just beyond the park entrance station. This dead-end route reaches a wonderful array of destinations, and, as a result, it’s extremely popular and sometimes dismayingly crowded. A free park shuttle bus provides a convenient way to reach trailheads along the route. There’s even a bus that picks up passengers in Estes Park and delivers them to bus stops in the national park.

Moraine Park is home to the park’s most popular campground, as well as trailheads for several excellent hikes. The south side of the valley is a good example of a moraine, a long ridge of rock piled up by a moving glacier. This area is great for wildlife-watching, especially at the shallow ponds along the 2.3-mile route to Cub Lake. Learn more about local geology at the Moraine Park Visitor Center.

Farther along Bear Lake Road, Sprague Lake makes a fine picnic spot, but its best feature is a flat, handicapped-accessible, half-mile trail around the lake. This site is especially enjoyable for families with small children and people who might not be able to walk other park trails.

Another 3 miles up Bear Lake Road is Glacier Gorge Trailhead, with some of the national park’s best-loved hikes. It’s only 0.8 mile to thundering Alberta Falls, one of the most impressive cascades in the park. In another 0.4 miles you reach a junction where you can choose to continue to Mills Lake (5.6 miles round-trip from Glacier Gorge Trailhead) or The Loch (6 miles round-trip). Both are among the park’s most spectacular destinations: alpine lakes surrounded by craggy Rocky Mountain summits. If you choose The Loch, consider continuing another 1.4 miles to Timberline Falls, where Icy Brook cascades over a cliff.

Bear Lake Road ends, naturally enough, at Bear Lake, with a large parking area that often fills up by 9 a.m. in season. The peaks of the Continental Divide loom above Bear Lake, and trails lead to fine destinations such as Dream Lake, Lake Haiyaha, and, for the adventurous, those distant mountain summits. If you want to say you’ve climbed a peak on the Continental Divide, the 4.4-mile hike up Flattop Mountain is one of the moderate choices in the park—though still a strenuous undertaking, rising 2,849 feet along the trail.

The Southeastern Corner

Colo. 7 south from Estes Park leads to several rewarding destinations, including the very strenuous 8-mile climb to the top of Longs Peak. Lots of people want to say they’ve reached the 14,259-foot summit, the park’s highest point, and lots of people make it. But don’t underestimate the difficulty of this trek. Fatalities do occur here; dangers include steep trails, bad weather, and lightning. It is a good idea to talk with a park ranger before attempting the climb. An alternative, though still a challenging, option, is the 8.4-mile round-trip hike to Chasm Lake, which sits at the base of Longs Peak’s awesome east face, a sheer cliff towering far, far above.

Farther south, the Wild Basin area has some excellent trails, including the 1.8-mile route to the lengthy series of falls called Calypso Cascades. The waterfalls here are named for the rare calypso orchid, also known as fairy slipper.

It’s another 0.9 miles to Ouzel Falls, one of the park’s most impressive waterfalls. Ouzel Falls is named for the bird called water ouzel or, more accurately, dipper. This small brown bird frequents rocky streams and actually swims underwater to catch prey.

One of the best longer hikes in the Wild Basin area is the strenuous 6-mile (2,478 foot elevation gain) trek to Bluebird Lake. With mountain peaks rising above the water, the alpine scene here embodies the essence of the national park.

Trail Ridge Road—West Side

Driving west on Trail Ridge Road past the Alpine Visitor Center, you soon cross the Continental Divide at 10,758-foot Milner Pass. It’s not a particularly scenic spot, but it marks the place where water flows to the Colorado River instead of the Mississippi. Visitation is lighter on this side of the park, and rainfall is somewhat heavier, giving the forests a lusher look. You’re more likely to see moose in the willows along the river than elsewhere in the park.

As you head south through the Kawuneeche Valley, take time to stop at the Holzwarth Historic Site. Here a German immigrant began a homestead in 1917, eventually expanding it into a small resort catering to trout anglers, horseback riders, and other vacationers. The historic buildings are well preserved, and park rangers offer tours in summer.

Trailheads along US 34 offer access to routes leading east to mountain summits and alpine lakes. For a less-strenuous introduction to the east-side environment, you can make a loop trail by combining parts of the Onahu Creek, Tonahutu Creek, and Green Mountain Trails. This route of around 7 miles passes through woodlands of lodgepole pine and other conifers and along part of Big Meadows, an expansive open area along Tonahutu Creek. Watch for moose on the first part of this loop.

The most popular hike on the park’s west side is the easy 0.3-mile walk to Adams Falls, where a cascade thunders through a gorge in a rocky cliff. Most people turn around here, but by continuing another 1.5 miles you’ll pass through meadows with splendid summer wildflowers and fine views of Rocky Mountain summits to the east. Reach this trailhead by following West Portal Road through Grand Lake, the community that serves as the western gateway to the national park.

Information

|

How to Get There From Denver, CO (70 miles southeast), take US 36 north to Estes Park. When to Go Summer and early fall are the most popular seasons. Although Trail Ridge Road is closed from about mid-Oct. to Memorial Day and snow covers hiking trails, many visitors enjoy snowshoeing, cross-country skiing, and wildlife-watching in winter. Visitor Centers Beaver Meadows and Kawuneeche Visitor Centers are open year-round. Alpine Visitor Center and Moraine Park Visitor Center are open in summer and early fall. Headquarters 1000 Highway 36 |

Camping Five campgrounds—Moraine Park, Glacier Basin, Aspenglen, Longs Peak, and Timber Creek—provide more than 500 sites; recreational vehicles of various lengths are allowed at all locales except for Longs Peak. Check restrictions at nps.gov/romo/planyourvisit/camping.htm. Moraine Park Campground remains partially open all winter, while others are open from about late May through Sept. For reservations, recreation.gov; 877-444-6777. The park has a great variety of backcountry campsites; a permit (fee in peak season) is required. Check nps.gov/romo/planyourvisit/backcountry.htm or call the backcountry office, 970-586-1242. Lodging There are no facilities within the park. Lodging is plentiful in Estes Park, Grand Lake, and other nearby towns. For information, check visitestespark.com or grandlakechamber.com. |

Morning Glory Pool

Wyoming, Idaho, & Montana

Established March 1, 1872

2.2 million acres

The world’s first national park, Yellowstone was established before the states that now surround it became part of the Union. Unknown then to all but Native Americans, Yellowstone soon became a national icon. A great volcano broods beneath the world’s largest concentration of geysers and hot springs. Snowcapped mountains water a landscape of lakes, rivers, canyons, and forest, teeming with the full complement of northern Rockies wildlife.

Yellowstone is a rough rectangle measuring 50 by 60 miles draped across the Continental Divide. Seen from space, the park is a high plateau ringed by mountains. At its center lies the caldera, or collapsed crater, of a single supervolcano (see here). The Yellowstone River flows through from the south, filling the great expanse of Yellowstone Lake before plunging into colorful canyons. Geysers, hot springs, and mud pots, found throughout the park, are concentrated most densely along a small river, the Firehole. The park’s northern section is distinct from the rest. Lower and more open, with milder winters, it is important for wildlife, particularly bison and elk.

In winter, extreme cold, deep snow, and wildlife combine with geyser steam to produce a fantasy landscape of frost crystals and shifting mist. It’s beautiful, but challenging to living creatures. Spring brings renewal, as meadows turn green and newborn animals appear. Summer is the time for growth and the fleeting bloom of wildflowers, while autumn is the season of preparation for the coming cold. In Yellowstone, winter is never far off.

The best tip for seeing wildlife and avoiding crowds is to start early in the day. Because most visitors stay close to their vehicles, you can find solitude by walking even a short distance on almost any trail.

► HOW TO VISIT

Yellowstone’s road system forms a figure 8. Called the Grand Loop, it measures 142 miles, with spurs leading in from five entrances. At least three days are needed to sample the park. First, visit the geyser basins between Old Faithful and Mammoth Hot Springs for a day focused on thermal activity. On the second day, take a drive through the park to see such highlights as Yellowstone Lake, Hayden Valley, and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone for mountains and wildlife. With more time, explore the northern range, where wolves are most likely to be seen.

Join a ranger-led guided walk for a deeper understanding; these are offered throughout the park.

Note that bicycles are permitted on some trails and can be rented in the park (nps.gov/yell/planyourvisit/bicyling).

Old Faithful to Mammoth Hot Springs

Old Faithful Geyser stands at the head of the Upper Geyser Basin, a dish-shaped valley about 2 miles long. The Firehole River runs down the middle, past hot springs and geysers. Check at the Old Faithful Visitor Center for predicted eruption times of the major geysers and to pick up a trail map.

Old Faithful erupts on average every 90 minutes. But it isn’t clockwork. Rangers need to see one eruption to predict the interval for the next. If you have time, you can walk the easy half-mile trail around the geyser site. You’ll see Firehole River, several hot springs, and, from most points along the way, Old Faithful when it erupts.

After the eruption, cross the river on the footbridge and head for Geyser Hill, where practically every square foot is steaming, erupting, bubbling, or flowing with hot water. You’re likely to see at least one geyser erupting, and perhaps a large one. Almost surely, little Anemone will perform; it erupts every few minutes.

At Lion Geyser, you can choose to finish the loop and return to your car, or continue down-basin, all the way to deep, funnel-shaped Morning Glory Pool, named for its startling blue color, reminiscent of its namesake flower.

Back in the car, head north. A quick stop at Black Sand Basin is worthwhile. Here, Cliff Geyser erupts frequently from an unusual creekside pool, and Opalescent Pool has water to match its name. For the next few miles, watch for bison; they like the meadows along the Firehole River. Mature bulls, weighing upward of 2,000 pounds, tend to stay by themselves or with a few comrades. Larger groups consist of cows, calves, and young males.

At Midway Geyser Basin, a boardwalk loop leads past two enormous contrasting hot springs. Excelsior was a huge geyser during the early years of the park. Now it’s a 300-foot-diameter crater filled with steam and vigorously boiling water that sends 4,000 scalding gallons a minute into the river. Beside it, the equally large but placid Grand Prismatic Spring flows gently over tiny stone terraces, supporting brightly colored tendrils of algae and bacteria.

Two miles farther, turn right on Firehole Lake Drive. Great Fountain Geyser erupts spectacularly but only about twice a day, visible from a platform of concentric reflecting pools. Check the prediction board beside the geyser to see estimated eruption times. You have a much better chance of seeing White Dome Geyser erupt, just ahead; its frequent eruptions are wispy sprays, but the cone, which apparently dates from a time when eruptions had greater power, is impressive.

Rejoin the main road at Fountain Paint Pot, best known for its pool of bubbling mud. Children love the mud pots and even adults giggle as blobs splurt into the air.

Nearby, Clepsydra Geyser has erupted virtually nonstop since the 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake, magnitude 7.3, kicked it into action.

The scene changes as you head north. Many miles of meadow, forest, and winding rivers lie ahead—favored haunts of bison, waterfowl, coyotes, and occasional elk. As you drive across Fountain Flats, look ahead. The flat-topped ridge in the distance is the rim of the caldera from Yellowstone’s last great eruption, some 640,000 years ago. This is one of the few places where it’s visible; in general, erosion and small subsequent lava flows have obscured what must have been a distinct crater when it was young. So huge and yet so hidden, it’s no wonder geologists needed years and help from satellite photos to recognize the true scale of the Yellowstone supervolcano.

Just shy of Madison Junction, the river dives into the narrow Firehole River Canyon, a series of cascades and a good waterfall. Take the one-way loop drive (2 miles) to view it. There might be river otters in the canyon. Bald eagles perch on dead snags eyeing the water for trout.

At Madison, the Firehole joins the Gibbon River to form the Madison River. Turning left takes you downstream, 14 miles to the west entrance. Instead, continue toward Norris. The cliffs on your left, rising 1,500 feet, are the volcano’s caldera rim.

One can only imagine how it might have been to stand on that rim just a few years after the eruption, gazing into a vast smoking crater, a 30-by-50-mile scene of pure devastation. Today, the peaceful meadows along the Gibbon are as gentle as the past was violent.

Turning north, the road climbs past graceful Gibbon Falls (84 feet high), leaves the caldera behind, cuts through two large meadows favored by elk and bison, and arrives at Norris.

Take half an hour or so to visit the small Norris Geyser Basin Museum, perched above the basin. Located where major faults intersect the fractured perimeter of the caldera, Norris claims the hottest ground in the park. In places, its surface can approach 200°F.

Things change fast here. Porkchop Geyser blew itself up in 1989 while people watched. No one was hurt but temperatures and activity have increased since then, requiring re-routing of nearby trails. Steamboat Geyser, largest in the park, erupts rarely but with great power, soaring more than 300 feet in the air.

Near the entrance to the Norris Campground, step back in time at the Museum of the National Park Ranger. Here, park visitors can learn about the rich history of rangers in the National Park Service. Exhibits depict the evolution of the profession, from its 19th-century military roots.

Thermal activity continues along the road north. Roaring Mountain is a steaming, hissing pile of white rock. Obsidian Cliff stands where molten lava cooled quickly, forming black volcanic glass. Native people quarried large amounts of it for stone tools, trading it as far away as Ohio and proving, incidentally, that they knew Yellowstone well. Old reports that they feared and avoided the park have no basis in fact.

The drive ends at Mammoth Hot Springs, an ever-changing landscape of travertine terraces, pools, and hot rivulets. Mineral deposits here can grow a foot and more a year. Springs appear, only to dry up and resurface somewhere else. Take the 1-mile loop road to see them, or follow the boardwalks.

Historic Fort Yellowstone, built by the U.S. Army when it ran Yellowstone from 1886 to 1916, now serves as park headquarters.

Canyon to West Thumb

The Canyon Village Visitor Center has some of the best interpretive displays in the park, with an emphasis on geology and the volcano. Begin there, then head for the canyon rims where numerous viewpoints and cliff-edge trails provide stunning views into this brightly colored gorge.

The canyon is an ancient geyser basin. Over millennia, hot water and chemical action weakened the rhyolite bedrock, changing it from its original dark gray to a palette of yellows, reds, and oranges. At the canyon’s heart thunders 308-foot Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, wonderful to see from any angle.

From North Rim Drive you can access Lookout Point, with its classic view of the Lower Falls. Below Lookout Point and visible from it, a trail to Red Rock Point leads below the canyon rim for a closer view, looking up at the falls. Or consider the strenuous 400-foot descent to the Brink of the Lower Falls platform, one of the most thrilling places to stand in the park. Where the green river turns to white froth and plunges into mists far below, you can almost feel the rocks shake. At 308 feet, Lower Falls is the tallest waterfall in the park.

Two miles upstream, the 109-foot Upper Falls puts on a show nearly as powerful. The trail to its dizzying brink is short and easy.

A little farther south, turn left and cross the river to the south rim. Artist Falls is named for Thomas Moran, whose paintings of Yellowstone helped convince Congress to make it a park and to buy his famous 1872 painting of the canyon. You can see a reproduction in the visitor center for comparison with the real thing.

Above the canyon, the river flows peacefully through wildlife-rich Hayden Valley. Plan to stop several times to scan the water for trumpeter swans, white pelicans, Canada geese, and river otters. Watch the rolling grass-covered hills for bison, coyotes, and perhaps bears. Grizzlies prefer open areas like this. In spring, they are drawn to the remains of winter-killed bison and elk; in summer, they dig for rodents and tubers.

You might have no choice but to stop. Traffic moves slowly if animals are near the road. Park regulations require you to keep your distance—at least 100 yards from bears and wolves and 25 yards from other large animals.

Mud Volcano is the dark side of thermal areas. You’ll find no jets of clear water here. Rather, this is a primal, sulfur-smelling collection of churning mud pools. Sulfur Caldron has a pH similar to the acid in a car battery. Dragon’s Mouth Spring belches loudly from a hillside cavern. It’s an easy place to imagine a real-life dragon emerging through a shadowy curtain of steam.

Continue upriver through forest and meadow to Fishing Bridge, at the outlet of Yellowstone Lake. Fishing, once popular here, is no longer permitted. Here, native cutthroat trout feed among clumps of river vegetation. There are far fewer trout in recent years. Predatory lake trout, illegally introduced to the lake in the 1990s, have decimated the native fish population, with far-ranging impact on the lake-based ecosystem.

At the nearby marina, you can book a boat on Yellowstone Lake (nps.gov/yell/planyourvisit/boating.htm).

Driving east a few miles takes you to Pelican Valley, open and lush; look for moose along the winding creek. Stretch your legs on the Pelican Creek Nature Trail, an easy 1-mile loop through forest to a fine pebble beach.

Consider driving farther along the lakeshore past Steamboat Point and Sedge Bay to Lake Butte Overlook. The panoramic view from here is the best in the area. On a clear day, the Teton Range, more than 60 miles away, is plainly visible.

Back on the road, drive 21 miles along the forested shore of Yellowstone Lake, North America’s biggest alpine lake—136 square miles of surface area with 110 miles of shoreline. The waters are icy despite the numerous hot springs, thermal formations, and even some erupting geysers that scientists have located on the lake bottom.

On the far side of the lake, the Absaroka Mountains stand snowcapped, marking the east boundary of the park.

West Thumb Geyser Basin is unusual for being on the shore of the lake. Some of its thermal features, like Fishing Cone, are actually in the lake. It’s worth walking the short boardwalk loop just to see Black Pool. Hypnotically blue, it is one of the park’s most beautiful hot springs.

Lower Falls of the Yellowstone

Bison in the Lamar Valley

The Northern Range gets its name for a simple reason. This is good grazing range in the northern section of the park. In contrast to the higher central and southern sections, the land here is open, with fewer trees, more grass, and less snow in winter. Conditions are good for many animals, especially the big herbivores—bison, elk, mule deer, and pronghorn—all of which are commonly seen here. Behind them come predators, notably gray wolves that, since their reintroduction in 1995, have become a major attraction for wildlife watchers. This is the most likely place to see them.

Begin at Mammoth Hot Springs and drive east. After crossing a high bridge over the Gardiner River, the road climbs across forested slopes. Black bears prefer this sort of country, a mix of woods and meadows. Grizzlies are more comfortable in open spaces. If you see a bear, don’t judge by color. Only about half the park’s black bears are black. The rest are blond, brown, or cinnamon.

Soon the road enters the wide-open spaces of Blacktail Deer Plateau. A line of mountains on the southern horizon shows the effects of the great 1988 fires, when an unusually dry early summer led to tinderbox conditions. Despite what was then the largest wildfire-fighting effort in U.S. history—25,000 in personnel and $120 million spent—more than a third of the park was affected. Wildfire is a natural force in Yellowstone, which it proved in spectacular fashion that summer. The blaze that burned this area was called the North Fork Fire. It began outside the west boundary of the park and ran nearly 60 miles before autumn snow, not fire crews, finally put it out.

At Tower Junction, go straight to 132-foot Tower Fall, then beyond, up a long climb over Dunraven Pass to Canyon Village. Turn left across the Yellowstone River. The next few miles are good for bison and boulders. The bison are there for the grazing. The boulders are glacial erratics, carried here by glaciers that flowed from mountains to the northeast. Scattered by the thousand in this area, many of them are paired with mature Douglas fir trees, as if each rock has adopted a tree. In fact, the rocks provided an extra bit of shelter and moisture when the trees were seedlings, helping them grow. Children like to say the trees have pet rocks.

Head back to the main road. Where it meets the Lamar River, it pushes upstream through a narrow canyon into Lamar Valley, made famous in recent years as a place to see wolves. Park policy in early years called for removal of predators, including coyotes, mountain lions, wolves, even raptors. Of those, wolves were the only ones exterminated. In 1995, after some 70 years without them, gray wolves were brought back. They have thrived, and their impact runs deep. A healthy ecosystem needs all its players. Yellowstone’s cast of characters is once again complete. The best way to spot wolves is to watch for groups of people with long scopes on tripods.

The cluster of log buildings called Buffalo Ranch is the site of another conservation success. In 1907, 28 bison were brought here and ranched like cattle. That effort lasted into the 1950s when the herd was judged large enough to successfully roam free. Today the park supports 4,000 or more of the large mammals. Ahead, mountains close in as the road climbs toward the northeast entrance, the town of Cooke City, and (open in summer only) the jaw-dropping high route over Beartooth Pass.

Hiking the Mount Washburn Trail

Other Hikes & Activities

The park’s highest road runs from Canyon Village to Tower over Dunraven Pass. About 3 miles north of Canyon, stop at Washburn Hot Springs Overlook for sweeping views to the south. From here you can truly grasp the scale of the caldera, as explained by an interpretive sign. To get even higher, consider the 2.7-mile hike to the summit of Mount Washburn on the old Chittenden Road. The views are unmatched, summer wildflowers are lush, and bighorn sheep are commonly seen.

A few side roads are open to bicycles but not cars. Bunsen Peak Road (6 miles) curves around a large open meadow and down a steep canyon, ending at Mammoth Hot Springs. Near Old Faithful, Lone Star Geyser is an easy 3-mile trail along the Firehole River. In the Lower Geyser Basin, Fountain Freight Road (5.5 miles) passes Goose Lake, a fine picnic spot. Park your bicycle and hike to Fairy Falls and Imperial Geyser.

Take a guided boat trip on Yellowstone Lake or explore by canoe or kayak. Experienced paddlers might consider the lake’s remote southern section for wilderness trips; only hand-powered craft are allowed there and on Shoshone Lake. Permits are required for private boats. Backcountry camping also requires a permit.

To deepen your understanding of Yellowstone, join a ranger-led interpretive program. Offered throughout the park from Memorial Day to Labor Day, program subjects cover the full spectrum of geology, biology, astronomy, history, wildlife management, and more. Activities include guided walks through the geyser basins, along canyon rims and lakeshores, and on backcountry trails. Some take in places unknown and unseen by most visitors. Others are short talks at points of interest. Quite a few are geared toward families and children.

Evening programs, some illustrated with visuals, continue the time-honored tradition of national park campfire talks. All of them are worth doing, and except for the boat cruise on Yellowstone Lake, there is never a charge; it’s just a matter of choosing which aspects of Yellowstone you’d like to learn more about. For a schedule, check the park newspaper, free at all entrance stations and visitor centers. The information is also posted on the park website.

Information

|

How to Get There Yellowstone has five entrances. US 20 and US 191/287 lead to the west entrance. For the north entrance, follow US 89 to Mammoth Hot Springs. The south entrance is reached on US 89/191/287 through Grand Teton National Park. From the east, US 14/16/20 follows the North Fork Shoshone River. The most spectacular route is open summer only. US 212 climbs over 10,947-foot Beartooth Pass, to the northeast entrance. Lodging Lodging is available within the park at Canyon Lodge & Cabins, Grant Village, Lake Lodge Cabins, Lake Yellowstone Hotel & Cabins, Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel & Cabins, Old Faithful Inn, Old Faithful Lodge Cabins, Old Faithful Snow Lodge & Cabins, and Roosevelt Lodge Cabins (yellowstonenationalparklodges.com; 307-344-7311). All are seasonal; winter lodging is limited to Mammoth and Old Faithful. Lodgings can fill up a year in advance. |

Headquarters P.O. Box 168 Camping The Park Service operates seven relatively small campgrounds (first come, first served) and five large reservation campgrounds. More than 1,700 sites; check nps.gov/yell/planyourvisit/campgrounds.htm. When to Go Mid-June to Labor Day is peak season. Spring comes in gradually, with few visitors. Autumn can be spectacular, with cool nights and warm days. In mid-Dec., the park opens for winter; over-snow vehicles only. The northern road from Gardiner to Cooke City stays open all year. Most roads open around mid-April and close at the end of Oct. Visitor Centers Of Yellowstone’s six visitor centers, only Old Faithful and Mammoth are open year-round. |