Dunefield at Stovepipe Wells, Death Valley National Park

Visitors to the nine national parks of the Pacific Southwest can bask on a tropical isle or climb a snow-clad peak. They can witness the vegetation going from tropical to subalpine in a single scenic drive, observe plants and animals that make their home in only one place in the world, and actually see the Earth build itself.

The island parks, all of them located on volcanoes except for Channel Islands, are microcosms of evolution and laboratories of the effects of humans on the land. At Hawai‘i Volcanoes and Haleakalā, preservation efforts seek to stem the damage done over centuries to the native plants, about 90 percent of which are found nowhere else. Some 2,600 miles southwest of Hawai‘i, the National Park of American Samoa shelters fragments of tropical rain forest and coral reef as well as an endangered 3,000-year-old human culture. Off the coast of California, the Channel Islands safeguard threatened seals, sea lions, and seabirds. They also harbor some 70 different species of endemic plants.

On the mainland, California’s Sequoia & Kings Canyon and Yosemite provide haven for a multitude of plant and animal communities in what John Muir called “the range of light”—the Sierra Nevada. Chaparral and wild oats robe the foothills; cathedral-like groves of conifers embellish slopes; wildflowers overrun alpine meadows. Marmots and pikas scurry on the glacier-carved heights. Thanks to a comprehensive recovery program, California condors once again soar the skies and scavenge the rugged terrain of the newest national park in the United States, Pinnacles.

To the south, Joshua Tree National Park preserves the unique high Mojave Desert habitat of the giant branching yucca. The 140-mile-long, erosion-sculptured basin that is Death Valley National Park—the continent’s hottest spot (134°F)—shelters more than 900 plant varieties, as well as bobcats and desert bighorn sheep.

Ofu island

American Samoa

Established October 31, 1988

13,500 acres—9,500 land, 4,000 marine

The only national park entirely south of the Equator and one that the U.S. government leases rather than owns, the National Park of American Samoa is a South Pacific Polynesian paradise. The small archipelago boasts deep blue waters, coral reefs (teeming with fish), secluded beaches, and what just might be the most pristine air in the world.

T his park is a place that seems to occupy its own world. The islands of Tutuila, Ta’u, Ofu, and Olosega are some 2,600 miles southwest of Hawai‘i. Because the national park is leased, local villages have a large stake in the success and management of the park. Villagers who’d had plantations before the park was established continue to work them. No construction is permitted without an agreement between park management and village chiefs.

► HOW TO VISIT

American Samoa is reached by air. Except for a few villages and the scenic drive that skirts the Pago Pago Harbor and the southern coastline there is little level ground on the park’s main island of Tutuila. For a bird’s-eye view, climb the 3.7-mile trail that leads to the 1,610-foot volcanic summit of Mount Alava. Along the way, possible bird sightings include white-collared kingfishers, cardinal honeyeaters, and purple-capped fruit doves.

The smaller islands of Ofu and Olosega have excellent coral reefs and the best snorkeling and scuba diving in the area. Ofu also has what many consider to be the prettiest beach in American Samoa.

Tutuila

The portion of Tutuila that falls within park boundaries is home to the capital, Pago Pago (pronounced “PAHNG-oh, PAHNG-oh,” though the locals opt for a single PAHNG-oh).

For a sense of timeless majesty, look north from the beach edging the village of Vatia. The beach is tiny, but the views of sweeping mountains and crashing waves are enormous—and unspoiled. (Outside the park, at the east end of the island, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration maintains an air quality station; indeed, the local air serves as the world’s baseline for air purity.)

From Vatia, hike the 1.1-mile Tuafauna Trail, which leads through one of the park’s three rain forest environments. The flora along the trail is a mix of trees, bushes, and ferns. Unlike many islands in Polynesia, Tutuila is not overrun with invasive, non-native plants.

Above fly fruit bats (flying foxes), which can have wingspans of three feet. The protection of these animals falls under the park’s charter. At the trail peak along the ridge, look out over the ocean. From the ridge, it’s a short drop to a small, protected beach.

Ta’u and Ofu

The second unit of the park is on the island of Ta’u, about 60 miles due east of Tutuila. Ta’u, where most residents of American Samoa live, is famous for two things: first, it’s where Margaret Mead did her Samoan-culture fieldwork; second, according to Samoan tradition, it’s where the first humans were created, by Tagaloa.

At the eastern edge of Ta’u, the park protects lowland and montane rain forest, which makes it a birder’s paradise. The 5.7-mile Si’u Point trail follows an old road through coastal forest. Fine coastline views are part of the experience.

The most remote area of the park is the island of Ofu. Just getting there is an adventure: fly to Ta’u, hitchhike (you’ll probably be offered a ride at the airport) to the harbor, and take a small boat out into the open waters to Ofu. (Ofu is actually two islands, Ofu and Olosega, connected by a short bridge.) Get the overview on the Oge Beach Trail, 2.7 miles along the ridge of Tumutumu, the mountain that runs the length of the island. The trail ends at Oge, a coral beach.

In winter, from the island’s south side there’s a chance of spotting humpback whales. But the real glory of the park is Ofu Beach, a marvel of powdery sand and turquoise water.

Information

|

How to Get There The park is accessed through Pago Pago International Airport. Here you can rent a car as well as arrange for charter flights or boat trips to other islands. Taxis serve Pago Pago, as do buses. (Note: It’s okay to sit on someone’s lap if the seats are all taken.) Hitchhiking is a way of life on the islands. When to Go American Samoa lies around 14 degrees south of the Equator. The islands are pretty much always hot and humid. The hot/wet season runs Oct. through May; the slightly cooler season, from June through Sept. Visitor Centers The visitor center and park headquarters are in Pago Pago, open year-round. This is the best resource for finding routes to the more remote park areas. |

Headquarters National Park of American Samoa Camping Camping is allowed with prior permission from the park superintendent. However, there are no designated camping areas in the park. Lodging American Samoa has everything from classic colonial hotels to chain hotel–style lodging (americansamoa.travel). On Ta’u, you’ll need a homestay; Ofu has one lodging, Vaoto Lodge (vaotolodge.com). Ask for a room that is catching the wind; the ones that don’t can be very hot. |

Western Anacapa Island from Inspiration Point

California

Established March 5, 1980

249,500 acres

A throwback to bygone California, the Channel Islands lie off the coast between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. These are secluded gathering places for both wildlife and humans who cherish invigorating escapes from big-city life. Their hacienda days long gone, the five isles have devolved back into nature. Here, paddlers share waters with humpback whales, and campers fall asleep to the sound of crashing waves.

Well into the 20th century the Channel Islands were a real-life version of a John Steinbeck novel, the domain of hearty ranchers, crusty abalone collectors, and eccentric scientists who came to study its natural wonders in splendid isolation. But after the archipelago became a national park, other sorts of people began flocking to the islands: nature lovers and outdoor sports enthusiasts bent on discovering a slice of Southern California that hasn’t been paved over or subdivided.

Often called the American Galápagos, the islands and the marine sanctuaries that surround them are an oasis of West Coast flora and fauna. Humpback, gray, blue, and killer whales share the offshore waters with great white sharks and 26 species of marine mammals. Elephant seals and sea lions gather in numbers that reach into the tens of thousands. Nearly 400 avian species have been recorded on the islands, which provide a nesting place for millions of shorebirds. There are endemic species of fox, skunk, mouse, snake, salamander, and lizard. The discovery of mammoth bones in 1994 revealed that island terrestrial life was even more diverse (and much larger) in ancient times.

But the Channel Islands also have their human side. Archaeological evidence proves the islands were occupied as early as 13,500 years ago—the oldest human remains found anywhere in North America were found here. Thousands of Chumash Indians called the islands home when the Spanish arrived; the last native inhabitants were forcibly relocated to mainland missions in the 1820s.

Hacienda life flourished after that, and the tradition lasted until the cusp of the 21st century (see here). Paddlers and photographers, backpackers and scuba divers are today’s denizens, although never in numbers that overwhelm this wild side of southern California.

► HOW TO VISIT

One of the few offshore national parks in the U.S., the Channel Islands are reached by water or air. The water crossing from Ventura, 60 miles north of Los Angeles, is an adventure all its own, with the morning sun breaking up the fog banks that often shroud the islands, and passengers on the lookout for migrating whales and dolphin pods. Most people visit the islands on day trips, with hiking, kayaking, scuba diving, and snorkeling the main activities. Some visitors overnight at one of 60 campsites; others make the long trek to backcountry camps.

Slender Anacapa (one hour by boat), with its historic lighthouse, attracts many visitors, while giant Santa Cruz (one hour by boat), with its spectacular sea caves, surf breaks, and secluded beaches, is the main water-sports hub. Santa Rosa (3 hours by boat; 30 minutes by air) is the most handsome, a wilderness of rare trees, white-sand strands, and rocky canyons. Far-off San Miguel (four hours by boat) is renowned for its copious wildlife, while tiny Santa Barbara (three hours by boat) packs a remarkable amount of nature into just 1 square mile.

Long, thin Anacapa is actually three islands separated by narrow channels. East Anacapa is the primary destination open to the public; the draw for Middle Anacapa is wildlife; while the entire West Anacapa is a wildlife reserve that protects the largest breeding colony of the California brown pelican. Despite its diminutive size (it is 5 miles long and a quarter-mile wide), Anacapa is rich in both flora and fauna, home to 265 plant species, the endemic Anacapa deer mouse, and colonies of harbor seals and California sea lions.

After landing at the cove on East Anacapa, visitors quickly ascend 150 stairs to the summit of the mesa-like island and its short hiking routes. A 0.5-mile trail ends at the Anacapa Light Station (built in 1932) and its half dozen outbuildings.

A slightly more challenging hiking hike (1.5 miles) heads in the other direction, to Inspiration Point and its fine vistas of the other islands. With its crystal-clear water, kelp beds, and three sunken shipwrecks, Anacapa is an especially important popular diving destination.

As the largest island in both the park and the state of California, Santa Cruz sprawls across an area about the size of New York’s Staten Island. Although the isle falls entirely within the national park, the Nature Conservancy owns and manages the western and central portions (76 percent of the land area), while the Park Service oversees the eastern end. Towering sea cliffs frame much of Santa Cruz; those on the north shore are punctured by some of the world’s largest sea caves. The island’s rugged interior is dominated by parallel mountain ranges separated by a deep central valley that actually is an earthquake fault.

Most of the concessioner boats from the mainland call on Scorpion Anchorage, jumping-off point for hiking, kayaking, and the island’s largest campground. A strenuous 7-mile trail leads over the mountains to Smugglers Cove, where there is an old adobe ranch house, an olive grove, and a lovely beach. Hiking is not allowed in the Nature Conservancy zone without a permit. Boaters can visit sunken caverns along the north coast, in particular Painted Cave, more than 100 feet wide and a quarter-mile deep.

Santa Rosa Island

With many of its major attractions a relative short walk from the pier, Santa Rosa is user-friendly, with a blend of natural and human history and some of the park’s most scenic trails. Beyond the pier is Vail & Vickers Ranch (see here), which includes a bunkhouse and barn, corrals, a tiny schoolhouse, and an attractive 19th-century ranch house that is shaded by large cypress trees and can be visited with a guide.

Past the airstrip, the coastal road curves around the edge of Bechers Bay to marshy Water Canyon, with a stream that spills down onto a white-sand beach backed by ocher cliffs. Continuing along the road, you soon reach a grove of Torrey pines. Found in only two places (here and San Diego), the tree is one of the rarest native pines in the United States and the last remnant of a Pleistocene forest that may have once blanketed the entire island.

A nearby spur trail leads to Black Rock, an ancient lava flow poised above the sea. Half a mile past the pines, another spur shoots off to a beach where the Jane L. Sanford ran aground in 1929, one of more than 140 recorded ships that wrecked in the islands.

The narrow shoreline trail continues east to the rolling sand dunes of Skunk Point and its snowy plover nesting area. Energetic hikers can tackle Black Mountain, a strenuous 8-mile round-trip from the pier that is well worth the effort for the summit’s cloud forest of dwarf trees and stunning views east toward Santa Cruz Island.

Other Islands

Farthest west and least visited are two islands. San Miguel is a paradise for pinnipeds (seals and sea lions). As many as 30,000 animals from five different species gather at beaches on the island’s westernmost extreme to breed, give birth, and generally lay about. Explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo may have died on San Miguel in 1542, during his milestone cruise up the California coast. His grave has never been found, but the Cabrillo Monument overlooking Cuyler Harbor honors the memory of the skipper who led the first European voyage into these waters.

A mesa formed by underwater volcanic activity, Santa Barbara Island, with 5 miles of hiking trails harbors several rare, endemic species, such as the night lizard and live-forever plant.

Information

|

How to Get There The only way to reach the islands is via concessioner boat, private boat, or small aircraft. From Los Angeles, CA (about 70 miles away), take US 101 north to the Victoria Ave. exit in Ventura, then follow the signs to Channel Islands National Park. Island Packers (islandpackers.com; 805-642-1393) operates boats to five islands from Ventura and Oxnard. Several companies organize guided kayak trips (details available on the park website). Channel Islands Aviation in Camarillo, CA (flycia.com; 805-987-1301), offers charter flights to Santa Rosa. When to Go The park is open year-round, but boats from Ventura Harbor are run less frequently run between late Nov. and early April. Summer offers ideal camping weather, but spring is best for wildflowers, and fall days can be simply glorious for boating and hiking. |

Visitor Centers Robert J. Lagomarsino, 1901 Spinnaker Dr., Ventura, CA, 4.5 miles from the Victoria Ave. exit on US 101. Open year-round. Headquarters 1901 Spinnaker Dr. Ventura, CA 93001 Camping Each of the five islands has a campground (72 sites total) that is open year-round. Backcountry camping is allowed on Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa islands. All camping requires advance reservations (recreation.gov; 877-444-6777). Lodging None of the islands offer overnight lodging. Hotels are plentiful in Ventura, (visitventura.com), Oxnard (visitoxnard.com), and Santa Barbara (santabarbara.com). |

Badwater Basin

California & Nevada

Established October 31, 1994

3.4 million acres

Hottest, driest, lowest, largest … Death Valley dazzles, even intimidates, with superlatives. The largest national park in the Lower 48 has indeed recorded the world’s highest temperature (134° F), nets less than two inches of rain a year, and contains the lowest spot in North America. But those extremes can add up to fascination. Death Valley National Park is nothing short of spellbinding.

Death Valley is geology laid bare—a scarred, gashed, dissected place where striated canyons gouge forbidding mountains, and where a vast salt-pan floor shimmers under a fierce sun. Ferocity reigns here. Yet Death Valley’s 300-plus miles of paved roads and a smattering of oasis-style facilities make it surprisingly easy to visit, though that doesn’t diminish at all the park’s overpowering impact.

No one has ever taken Death Valley lightly. The native Timbisha Shoshone people understood its hidden generosity—they knew how to harvest its pine nuts and mesquite beans, to hunt its bighorn sheep and mule deer, and to use arrowweed to craft naturally ventilated homes. But they also knew that summer was no time to linger on a valley floor that bakes at 120 degrees or more for months at a time. They retreated to the same high country that welcomes visitors today.

Gold seekers, prospectors, and borax miners largely displaced the Timbisha people. Mining ruins are among the park’s fascinations, as is the possibility of seeing wildlife (coyotes, roadrunners, and perhaps the nocturnal kit fox).

► HOW TO VISIT

Death Valley is huge and has multiple entry points. However you approach, make your way to its core, Furnace Creek, where you’ll find the main visitor center, food, and lodging. Although it’s possible to simply drive through the park in a day, you’d have little time to stop. With two full days, you can radiate out and back from Furnace Creek and visit attractions such as Ubehebe Crater, Scotty’s Castle, and Badwater, the lowest place in North America. With three days, you can include a day in the high country, and an even longer visit gives you time to explore remote terrain (a high-clearance vehicle is needed).

Badwater Road

If you enter Death Valley from the south, you’ll cut through the Black Mountains and make your way north on Badwater Road. This byway traces the sub-sea-level floor of Death Valley, flanked by towering mountain ranges to the east and west. If you choose a different entrance, be sure to allot at least a portion of a day to Badwater Road, which links some of the top geological marvels in the park.

This southern approach cuts through two mountain passes on Calif. 178, from which you can glimpse the shimmering salt-pan floor in the distance. And be ready to marvel at the rugged Black Mountains and the multicolored region geologists call the Amargosa Chaos. Once you’re on the valley floor, it’s evident that it was once a vast lake—look for water-level marks on Shoreline Butte, which you can see from the roadside adobe ruins of Ashford Mill.

At Badwater, you hit bottom, 282 feet below sea level. It’s named for a salty pool of water you can see from a short boardwalk. But be sure also to walk out onto the salt-pan floor of the valley and look up into the mountains for a sign, impressively high, that reads “Sea Level.”

A few miles farther is a dirt-road side trip that leads 1.3 miles to Devils Golf Course, a broad fairway of crusty pinnacles. Five miles farther is Artists Drive, a paved road that climbs into some of the most colorful terrain in the Amargosa Range. Four miles north is Golden Canyon, with perhaps the best 1-mile hike in Death Valley.

Furnace Creek & Beyond

Furnace Creek, the park’s commercial center, is a natural oasis shaded by date palm trees that has always been the heart of Death Valley—for natives, borax miners, and the earliest park visitors, who began flocking here when Pacific Coast Borax Company developed Furnace Creek Inn in 1927. The modern Furnace Creek Visitor Center has fine exhibits and offers ranger programs.

Just outside the park, the Borax Works tells the story of mining in Death Valley. Nearby is an 18-hole golf course—at 214 feet below sea level, perhaps the lowest in the world.

Calif. 190 east of Furnace Creek is all about vistas. Just 4.5 miles from Furnace Creek Ranch is Zabriskie Point, where an early sun casts a gentle glow on hills of mudstone, clay, and siltstone just below. Steep Dante’s View Road, 11 miles from Furnace Creek, leads past mining ruins to the park’s most accessible high viewpoint, a breathtaking mile above Badwater and the salt-pan floor of Death Valley.

Allow a full day to make the 54-mile drive north from Furnace Creek to Scotty’s Castle and Ubehebe Crater and back, as the road offers worthwhile sights along the way. About 2 miles north of Furnace Creek is the Harmony Borax Works, where you can see one of the 20-mule-team wagons that transported borax as far as 165 miles to the town of Mojave.

At Salt Creek, a dirt road leads about a mile to the start of a boardwalk alongside a saline creek that harbors an inch-long fish species—the Salt Creek pupfish—that exists nowhere else in the world.

After Calif. 190 veers west toward Stovepipe Wells, Scotty’s Castle Road continues north 36 miles to Scotty’s Castle—well worth a visit, and reservations are a good idea (recreation.gov). Scotty’s Castle is the Spanish-Mediterranean mansion built as a retreat by wealthy midwesterner Albert Johnson, and properly called Death Valley Ranch—an impressive, ahead-of-its-time spread that cost more than $2 million in 1920s dollars. Ubehebe Crater is just 8 miles from Scotty’s Castle. It’s worth the side trip to see a landscape that looks like the surface of Mars.

From an intersection 17 miles north of Furnace Creek, Calif. 190 leads west through the outpost of Stovepipe Wells and leads into the often-overlooked Panamint Mountains.Traveling west from the intersection, you shortly come to Mesquite Flats Sand Dunes, where you can park and explore a vast set of towering dunes.

Past Wildrose Campground, the road turns to dirt and leads to a remarkable sight: a line of 10 stone charcoal kilns that date back to the 1870s. The charcoal fueled silver-mine smelters. From the kilns, a 4.2-mile trail leads to 9,064-foot Wildrose Peak and a stunning view of Death Valley.

The only way you can get hiking access to the park’s high point, 11,049-foot Telescope Peak, farther along the road, is via a high-clearance 4×4 vehicle.

Information

|

How to Get There From the south (I-15), follow Calif. 127 north to either Calif. 178 or 190 west into the park. From Las Vegas, take Calif. 160 west to Pahrump, Nevada, then Bell Vista Rd. west to Calif. 127 to Calif. 190. From the Lone Pine on US 395, take Calif. 136 east to Calif. 190. From the southwest, take Calif. 14 north to Inyokern, then Calif. 178 east to Calif. 190. Camping Park campgrounds, with more than 750 sites, are first come, first served, except for Furnace Creek (recreation.gov; 877-444-6777). High-country campgrounds are occasionally unreachable in winter. Stovepipe Wells offers 14 RV sites (deathvalleyhotels.com; 760-786-2387). Visitor Centers Furnace Creek (park headquarters) on Calif. 190 in the heart of the park, and a small visitor center at Scotty’s Castle in the north part of the park on Scotty’s Castle Road. |

When to Go Late spring and late fall are the most pleasant seasons, but visitation is fairly steady year-round. Lodging Concessioner properties include Furnace Creek Inn and the Ranch at Furnace Creek (furnacecreekresort.com; 800-236-7916). For lodging outside the park, visit the park website (nps.gov/deva/planyourvisit/lodging.htm). Safety The park service recommends that visitors drink at least a gallon of water per day. Distances between services can be great in the park, so begin your day with all the gas, water, and snacks you’ll need. Headquarters P.O. Box 579 |

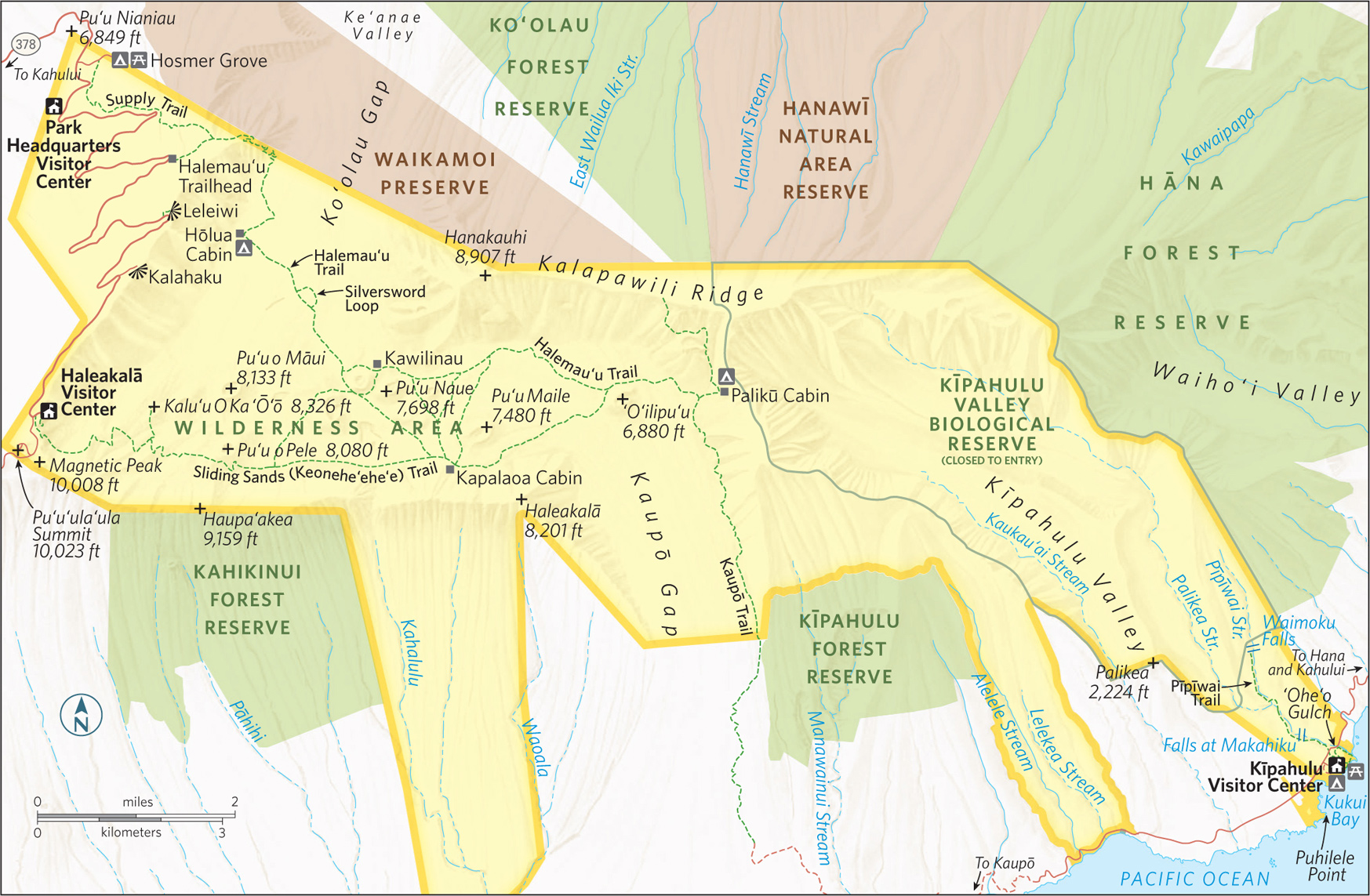

Haleakalā crater

One of the world’s most otherworldly landscapes awaits at the summit of the volcano at the core of this spectacular national park on the island of Maui. Named for the volcano (now dormant) that helped shape the land, Haleakalā National Park dominates the island skyline. The park encompasses the basin and portions of the volcano’s dramatic flanks. Protected here are some of the most endangered species on Earth.

When first established—in the same year as the National Park Service—only the summit and crater of Haleakalā were protected. They were part of a larger entity called Hawai‘i National Park, which also included the summits of Kīlauea and Mauna Loa on Hawai‘i Island. In 1961, Kīlauea and Mauna Loa became part of Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, while Haleakalā was re-designated as Haleakalā National Park.

Visitors reach the lower valley of the Kīpahulu District via the spectacular Hana Highway. The drive is an adventure with a progression of hairpin curves, bridges, and turnouts. It’s a byway rich in intensity—azure sea, black rock, silver waterfalls, and green forest and meadow. The coastal area of Maui was first farmed in early Polynesian times, more than 1,200 years ago.

About two-thirds of the park is federally designated Wilderness. One of the park’s main missions is to preserve and protect unique and fragile ecosystems, from sea level to summit, that include rare and endangered plants and forest birds. Much of this flora and fauna are found nowhere else on Earth. In fact, the park provides critical habitat to more endangered species than almost any other in the national park system.

Though commonly referred to as “the crater,” the summit of Haleakalā is actually a valley carved by erosion. Most visitors (more than a million a year) head to the summit, which is easily accessible by car. Others sign up for organized tours, some with hikes to watch the sunrise followed by a downhill bicycle ride outside the park boundary to the town of Kula for breakfast. Though popular at sunrise, the park is beautiful throughout the day, and sunset is just as compelling as daybreak.

► HOW TO VISIT

There are no highways or trails connecting the upper and lower areas of the national park. Both districts are truly remote, with medical and emergency assistance at least a 45-minute drive away.

Haleakalā National Park has two access points. The more heavily traveled of the two leads to the Summit District from the tourism-heavy side of the island, between the resort areas of Wailea and Kahului; the other access point is the community of Kīpahulu, on the remote eastern shore, near the town of Hana.

First stop: Park Headquarters Visitor Center at 7,000 feet, in the Summit District. Here, get information on trail conditions, permits, interpretive programs, and sightseeing. For all hikes, visitors should be prepared with water, snacks, sunscreen, and proper footwear, and share hiking plans with friends or family outside the park. Due to ever changing conditions, hikers should dress in layers and be prepared for all types of weather.

Several trailheads are located near the Park Headquarters Visitor Center, including Hosmer Grove and Halemau‘u Trail, along with two overlook points—Leleiwi and Kalahaku—that offer spectacular views into the crater. Kalahaku is only accessible from the downhill lane, so it’s best to head there on your way back down.

Indeed, a more in-depth exploration of the park can be had by embarking on any of the hiking trails that start at the Hosmer Grove, Halemau‘u trailhead, Haleakalā Visitor Center on the crater rim, and the Kīpahulu Visitor Center on the coast, near Hana.

Several miles up the road from the Park Headquarters Visitor Center is the Haleakalā Visitor Center (at 9,740 feet) and just beyond that is the summit (at 10,023 feet).

From Haleakalā Visitor Center, housed in a historic stone building, you can head out for a day hike or longer. More than 35 miles of trails lead through the crater’s Wilderness area, ranging from easy ten-minute walks to trails that require overnight stays.

Keonehe‘ehe‘e (Sliding Sands) Trailhead, adjacent to Haleakalā Visitor Center, leads down into the crater itself, traversing fascinating, lunar-like terrain. Hawai‘i’s state bird, the nēnē, is commonly spotted in this vicinity of the park.

Just outside park boundaries but clearly visible from the summit is Haleakalā Observatory, also known as Science City. Closed to the public, the astrophysical complex is operated by the University of Hawaii, the U.S. Air Force, and others.

Summit District

Hosmer Grove Loop is an easy, rewarding hike that starts 1 mile below the Park Headquarters Visitor Center. Next to the small campground, a short trail leads through native ‘ohi‘a lehua trees and native subalpine shrubland.

In addition to unique flora, Hosmer Grove is a very good area for bird-watching, with native forest birds, including Hawai‘i’s colorful, endangered honeycreepers, routinely spotted. Come nightfall, Hawaiian hoary bats sometimes make an appearance.

The parking lot at Hosmer Grove is where groups meet for 3.5-hour staff-led hikes through Waikomoi Preserve, off-limits except with a guide (inquire at the Park Headquarters Visitor Center for schedule and reservations).

The preserve, located on private land owned by Haleakalā Ranch and managed by the Nature Conservancy of Hawai‘i, offers visitors a glimpse into a threatened native Hawaiian rain and cloud forest that a number of endangered birds and insects call home.

Offering both easy and more moderate hiking options is the Halemau‘u Trail, which begins at 8,000 feet (3.5 miles upslope from the Park Headquarters Visitor Center) and leads 1.1 miles through native shrubland to the rim of Ko‘olau Gap. Here, the cliffs drop off 1,000 feet, and extraordinary views extend across the upper reaches of the park. This is one of Haleakalā’s best short walking experiences.

Pressing forward from the rim, a longer and less traveled trail descends 1,400 feet down a sometimes steep and narrow series of switchbacks to the valley floor. The views along this portion of the trail are remarkable. Across the valley, the landscape is rendered in various shades of muted rust and brown, punctuated by lava flows and lava cones. In many places, cinder ash covers the the valley floor.

At the 3.7 mile mark of the trail is Hōlua Cabin and campground for overnight stays (by permit). Less than a mile beyond the cabin, a short jaunt off the Halemau‘u Trail, the 1-mile Silversword Loop leads through an area displaying one of the greatest concentrations of ‘āhinahina (silversword plants) in the park. A mature ‘āhinahina can stand eight feet tall, with misty silver fingers emanating from a spiny center stalk. If you spot one of these unique plants with a large stalk abloom with purple flowers, you will know that plant is getting near to the end of its several-decade life cycle.

The Halemau‘u Trail is one of the primary hikes in the park. From the trailhead it extends 10.3 miles to the Palikū Cabin and the Kaupō Trail. The Halemau‘u Trail also branches off to Keonehe‘ehe‘e (Sliding Sands) Trail. A hearty, 10-mile route follows Halemau‘u Trail out, then loops back to the Haleakalā Visitor Center via Keonehe‘ehe‘e.

Pu‘u‘ula‘ula Summit

A short drive from the Haleakalā Visitor Center leads to the 10,023-foot summit of the mountain. Exhilarating 360-degree views are had from here; on clear days you can see the peaks of Hawai‘i Island.

An enclosed viewing area protects against the wind, and also makes a cozy spot for stargazing at night. Given the clear skies and absence of light pollution, nighttime can be quite amazing at the summit of Haleakalā.

The Keonehe‘ehe‘e Trail starts at the Haleakalā Visitor Center and descends 2,500 feet through a cinder desert to the crater floor. The trail’s Hawaiian name refers to how a he‘e—octopus—moves across the reef. In the trail’s soft cinders, hikers experience terrain that moves octopuslike underfoot. The footing is safe but challenging, especially for the hike back up the steep trail to the visitor center. (It takes twice as long to hike uphill and out of the crater than it does going down into the crater.)

The first portion of the Keonehe‘ehe‘e Trail is beautifully desolate, with little shrubbery and no trees or greenery of any sort. The red-hued cinder ash is otherworldly, particularly as you pass the frequent pu‘u (cinder cones) along the way.

Several offshoots of the main trail lead through the surreal terrain and hook up with the Halemau‘u Trail, or loop back to Keonehe‘ehe‘e. Kapalaoa Cabin is 5.6 miles from the trailhead, and Palikū Cabin is 10.3 miles from the trailhead. Permits are required at both cabins for overnight stays.

One of the less traveled and most spectacular trails in the upper regions of the national park is Kaupō Trail, one of the premier hikes in Hawai‘i. The upper trailhead is near Palikū Cabin (9.2 miles from the Visitor Center). The annual average of 30 inches of rain at the summit pales against Kaupō Gap’s 420 inches per year. The precipitation is responsible for the lush scenery. Numerous waterfalls can be seen from the trail.

Many hikers find that going up the rugged and steep Kaupō Trail is considerably easier than hiking downhill. The trail traverses the outer wall of the verdant pali (cliff), with broad views of Hawai‘i Island, and down to the southeastern shore of Maui.

The Kaupō Gap trail actually goes beyond park boundaries, through privately owned lands. Local property owners have granted hikers permission to cross their land, with the stipulation that they not stray from the designated trails.

A park ranger helps a visitor craft a hat of coconut leaves.

To get to the Kīpahulu District from Kahului, you’ll make one of the all-time great drives in the Hawaiian Islands, the Hana Highway. It’s a 68-mile road that runs along the scenic east coast of the island. And it’s a legendary road, with more than 600 hairpin curves, 59 bridges, and numerous scenic turnouts. Figure on stopping for at least a few photo opportunities along the way. All told, it can easily take more than 2.5 hours to get to Hana.

The Kīpahulu District and the coastal area of Haleakalā National Park are far different from the park’s upper reaches. At Kīpahulu the terrain is green with tropical rain forest vegetation and silver with waterfalls. Three miles of trails, parts of which are boardwalk, lead through this lush, inviting landscape.

Hana and Kīpahulu were once densely populated and farmed. The Kīpahulu portion of Haleakalā National Park was added not only to preserve the scenery, but also to allow a glimpse into traditional Hawaiian lifestyles, which are documented at the Kīpahulu Visitor Center. Nearby, traditional agricultural practices, such as the cultivation of taro, are being carried forth at Kapahu Living Farm.

The Visitor Center is a good first stop for cultural exhibits and hiking advice. Short trails branch out from here to the coast and upslope. Follow the Pīpīwai Trail through a bamboo forest to view the Falls at Makahiku (at the 0.5 mile mark) and Waimoku Falls (2 miles). The park is closed to visitors beyond the Waimoku Falls viewpoint due to possible rockslides and flash flooding from the waterfalls. In addition, above Waimoku Falls is the Kīpahulu Valley Biological Reserve, which is closed to visitors to protect critically endangered species.

Though many sources make reference to the Seven Sacred Pools that are supposedly found in the Kīpahulu section of the park, rangers are quick to clarify that no such place exists within the park. The reference is most likely to the freshwater pools found at ‘Ohe‘o Gulch, but in fact there are far more than seven pools at the gulch. Freshwater is considered sacred in Hawai‘i as the source of life.

While it is tempting to swim in the freshwater Pools of ‘Ohe‘o, which are accessed via a trail that begins at the Visitor Center, rangers advise against it. Visitors can easily slip on the smooth rocks or can be swept out to sea without a moment’s notice by “freshets”—flash floods that come without warning as the result of upcountry rains.

Rockfalls also are common. And there is another danger: In modern Hawai‘i, even clear, calm, fresh waters can be home to parasites such as Giardia leptospirosis. A spontaneous thirst-quenching moment could result in months of medical care.

Still, with its lush (non-native) bamboo forest, gushing waterfalls, and access to the beautiful and remote coast of southeastern Maui, Kīpahulu is one of the most scenic areas of the park. There is a wealth of idyllic spots for a picnic, relaxation, and solitude.

Information

|

How to Get There The Summit District’s park headquarters and Haleakalā’s 10,023-foot summit can be reached from Kahului via Hawaii 37 to 377 to 378. Driving time to the summit from Kahului is approximately 1.5 hours. Visitors should drive very cautiously; the road bisects endangered species habitat. The Kīpahulu District is reached via Hawaii 36 to 360 to 31. Driving time from Kahului is approximately 3.5 hours. Fill your gas tank and bring food with you; neither is available in the park. Both districts are remote. Lodging Kula provides the closest lodging to the Summit area; many visitors stay in hotels in Wailea and Kihei (gohawaii.com/maui). The nearest lodging to Kīpahulu is in Hana (hanamaui.com). Headquarters P.O. Box 369 |

When to Go The park is open year-round, 24 hours a day. Temperatures commonly range between 30°F and 65°F. With the wind-chill factor, the summit temperature can drop below freezing. Visitor Centers Park Headquarters Visitor Center, at 7,000 feet; Haleakalā Visitor Center, at 9,740 feet; Kīpahulu Visitor Center, at Mile marker 42 on Hana Hwy. Camping The Kīpahulu District has a drive-in campground (100 sites), as does the Summit District at Hosmer Grove (50 sites). Both accommodate campers on a first come, first served basis. Hiking access to all Wilderness campgrounds and cabins is via the Sliding Sands and Halemau‘u trails or Kaupō Gap. Permits from Park Headquarters Visitor Center are required for backcountry camping. Advance reservations are necessary for backcountry cabins. |

Hana, Maui

▷ Low volcanic cliffs line the rugged coastline of Wai‘ānapanapa State Park and offers a reprieve from the long drive along the Hāna Highway. Features include a native hala forest, legendary cave, heiau (religious temple), natural stone arches, sea stacks, blow holes, and a small black-sand beach. Hike the ancient coastal trail. Camping permit required. Fifteen miles from Haleakalā National Park. dlnr.hawaii.gov/dsp/parks/maui/waianapanapastate-park; 808-984-8109.

Wailuku, Maui

▷ The peaceful ‘Īao Valley, with its emerald peaks and lush valley floor, is home to one of Maui’s most recognizable landmarks, the ‘Īao Needle, an imposing erosional remnant significant for its role in the 1790 battle. Paths lead through a botanical garden, along ‘Īao Stream, and to the ridge-top observation pavilion with views of the needle and surrounding valley. Parking fee. Forty miles northwest of Haleakalā National Park. dlnr.hawaii.gov/dsp/parks/maui/iao-valley-state-monument; 808-984-8109.

Kealia Pond NWR

South Central Maui

▷The Keālia Pond National Wildlife Refuge is home to endangered water-birds, including the Hawaiian black-necked stilt (ae‘o) and Hawaiian coot (‘alae ke‘oke‘o). It is an ideal wintering location for migratory birds coming from Alaska, Canada, and occasionally Asia. Activities include bird-watching, educational programs, and volunteer habitat-restoration projects. Thirty-five miles southwest of Haleakalā National Park. fws.gov/refuge/kealia_pond; 808-875-1582.

Eastern Maui

▷ Part of the Nature Conservancy, Waikamoi Preserve has been set aside to protect hundreds of Hawaii’s native species. This high rain forest on the slopes of Haleakalā Volcano shelters 13 bird species, including the rare ‘akohekohe, the kiwikiu, the scarlet ‘i‘iwi, and the green ‘amakihi. The preserve also protects more than 41 species of rare plants. Access by guided tours only, offered on Thursday morning; reservations required. nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/hawaii/placesweprotect/waikamoi; 808-572-4400.

South Central Maui

▷ Cold, wet, foggy, and somewhat mystical, Polipoli Spring State Recreation Area has a climate similar to that of the Pacific Northwest, plus 10 acres of conifers and towering redwoods. Visitors hike and bike the miles of trails in the park and adjacent forest reserve. Note: There’s hunting within the confines of the park. Thirty-three miles southwest of Haleakalā National Park. dlnr.hawaii.gov/dsp/parks/maui/polipoli-spring-state-recreation-area; 808-984-8109.

Kanaha Pond Wildlife Sanctuary

Kahului, Maui

▷ The 245-acre Kanaha Pond Wildlife Sanctuary, in downtown Kahului, protects endangered waterbirds, including the pink-legged Hawaiian black-neck stilt. More than 909 species of birds can be found here. Kanaha is one of two twin fish ponds ordered built by the King of Maui in the early 1700s. Bird-watching kiosk. Twenty-five miles from Haleakalā National Park, near Kahului Airport. dlnr.hawaii.gov/wildlife; 808-984-8100.

Kīlauea’s Halema‘uma‘u Crater lights the morning sky.

Island of Hawai‘i, the “Big Island”

Established August 1, 1916

333,086 acres

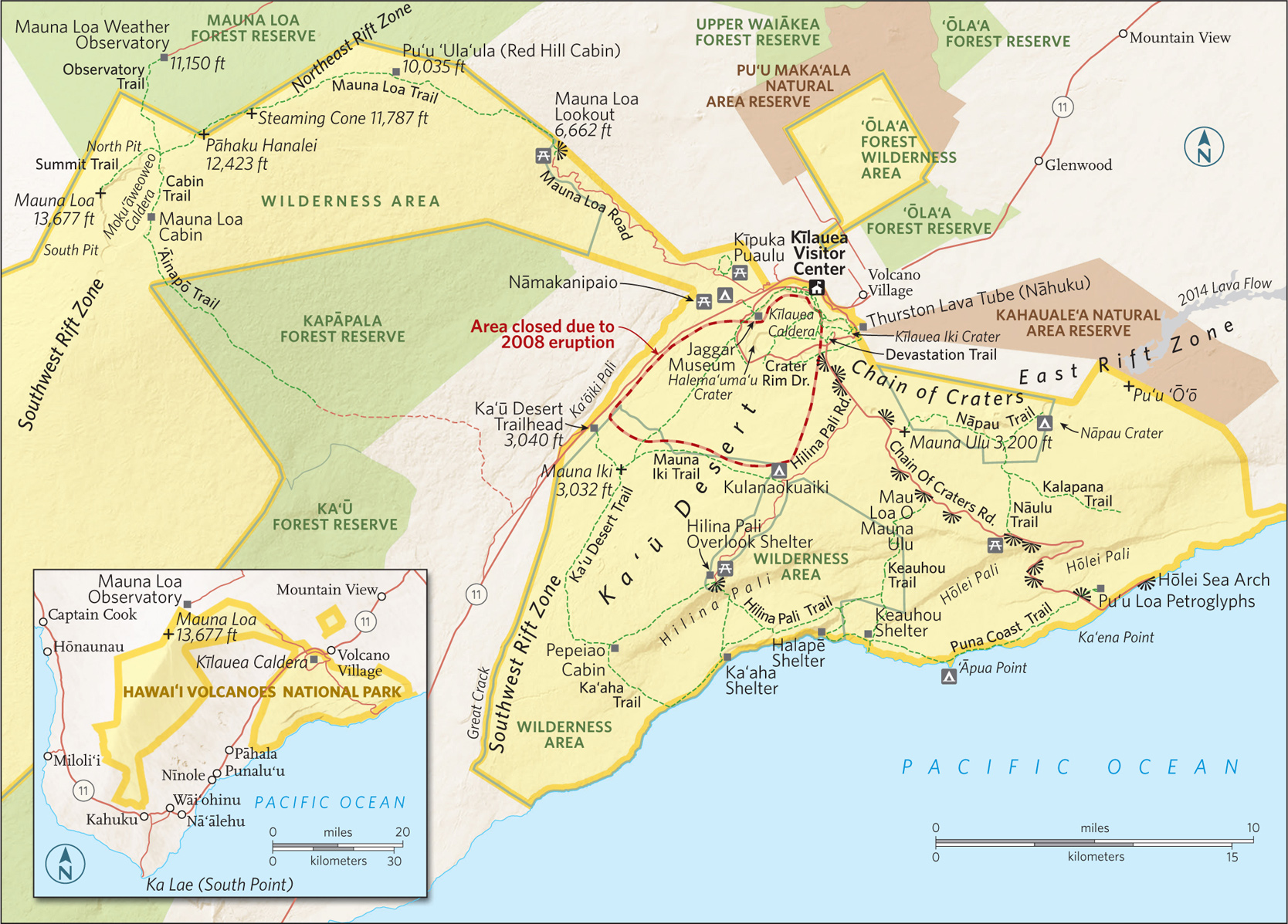

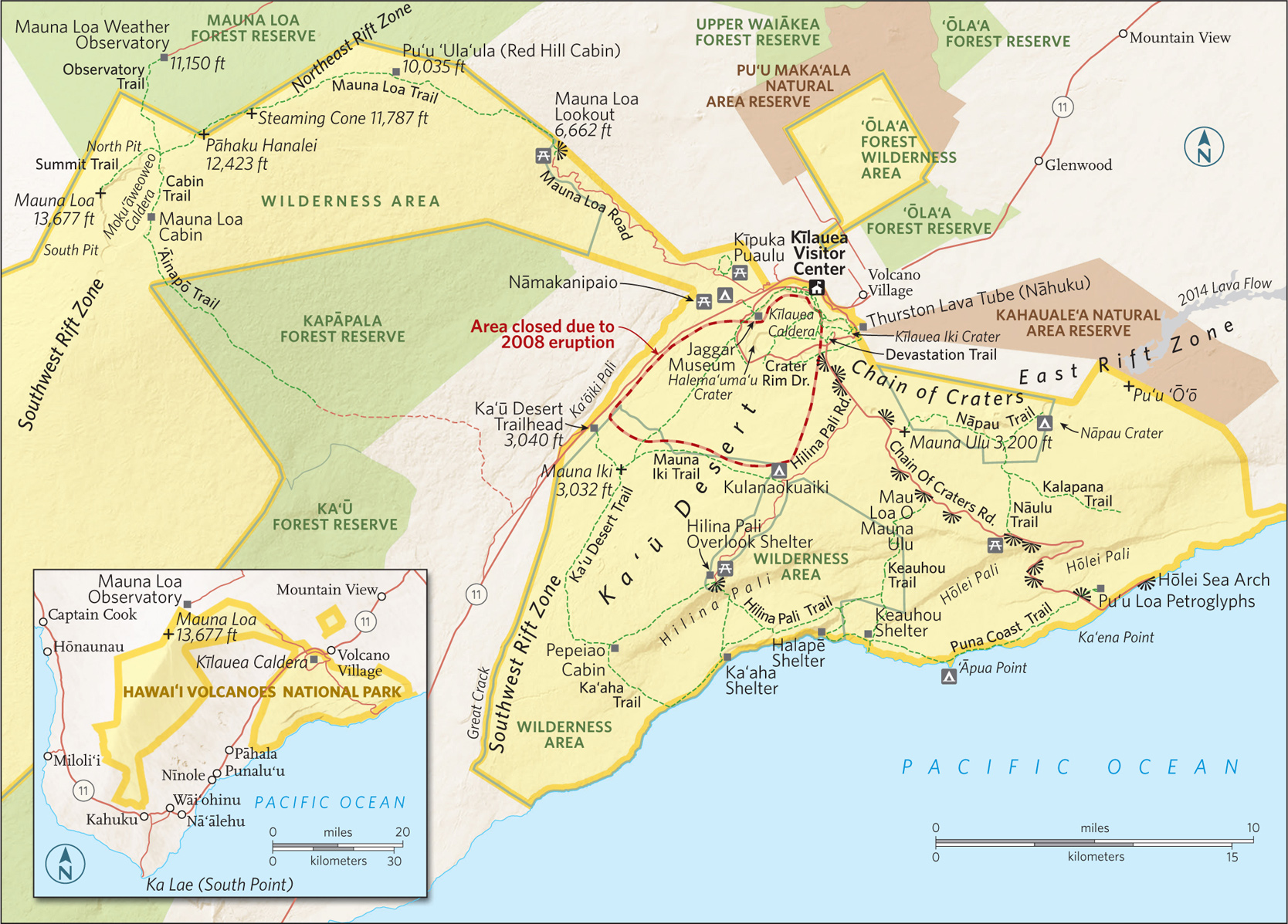

Stretching from the Pacific shoreline to the 13,677-foot summit of Mauna Loa, on the Big Island, Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park encompasses two major active volcanoes, Kīlauea and Mauna Loa. The park’s seven ecosystems showcase aspects of Hawai‘i that go far beyond the beach. A visit to Hawai‘i Volcanoes is an up close lesson in volcanic geology, Hawaiian culture, rare species of flora and fauna, and Polynesian mythology.

Volcanoes have their own language. Here in the park, visitors discover the difference between ‘a‘ā and pāhoehoe lava; peer at pu‘u formations; look and listen for pueo, ‘amakihi, and ‘apapane birds; and photograph the amazing sight of a lone ‘ōhi‘a bush emerging defiantly from a thin crack in a solid sheet of black lava.

The park’s seven major ecological zones range from rain forest to upland forest, sea coast to alpine, and lowland to woodland and subalpine. The two major volcanoes that lie mostly within the park’s boundaries, Kīlauea and Mauna Loa—in fact, the entire island—sit atop the underwater “hot spot” in the 3,600-mile-long Hawaiian Island–Emperor Seamount chain. This hot spot is responsible for the flow of bright red magma that issues from rifts on the sides of Kīlauea (and occasionally Mauna Loa), creating the newest land on Earth.

► HOW TO VISIT

Visitors can get a good sense of the park—and the 70-million-year-old volcanic dynamism of Hawai‘i—in as little as three hours by visiting the Kīlauea Visitor Center and Jaggar Museum, and driving down Chain of Craters Road to the ocean, where signs point out the many lava flows that have shaped the landscape over the years. Even a half-day visit to the park’s busiest areas reveals dramatic destruction, hard-fought renewal, and the creation of new land. But driving through the park or spending a day or more walking some of the park’s more than 150 miles of trails, and maybe camping out fosters a much deeper appreciation of the park’s many geologic subtleties, its rare wildlife, and the ancient Hawaiian culture that still holds this land sacred.

More than 1.5 million people a year visit Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. Most want to see the active lava flow. And while the most recent surface lava flows have occurred outside park boundaries, don’t be dissuaded. The park is a treasure trove for both casual visitors and avid volcano enthusiasts. To be sure, the erupting summit of Kīlauea is a must-see.

Start at Kīlauea Visitor Center, just inside the park’s main entrance. Here, rangers answer questions about what to see and do, and informative displays provide a basic history and lay of the land.

About 2 miles from the visitor center on Crater Rim Drive is the Jaggar Museum and an overlook that provides a view of Kīlauea Caldera. This is as close as visitors can get to the caldera (a large crater typically formed by a major collapse of the volcano’s mouth). An easy hike along Crater Rim Trail, which links the visitor center and the Jaggar Museum, leads past several steam vents and provides spectacular views into the crater.

The last summit eruption started on March 18, 2008, when rocks and lava blew from the Halema‘uma‘u Crater and spread across 65 acres, creating a vent and a boiling lava lake. As this book goes to press, that eruption was ongoing, and geologists think it might continue for another century.

Vents in the caldera are continuously issuing steam and volcanic fumes that can be seen any time of day. But it is at night (the park is open 24 hours) that the lava lake inside Halema‘uma‘u Crater gives off an eerie red glow stretching to the sky, dark and brimming with stars. Come at sunrise (you could have it all to yourself).

Hiking in Kīlauea Iki Crater

Crater Rim Drive & Beyond

An 11-mile loop, Crater Rim Drive encircles the summit caldera, passing through lush rain forest and desert (closed between the Jaggar Museum and Chain of Craters Road). The two most popular day hikes in the park start just off Crater Rim Drive. Thurston Lava Tube (Nāhuku) is the shorter of the two (2 miles) and most family friendly. It is named after one of the park’s greatest advocates, Honolulu businessman Lorrin Thurston, who discovered the tube in 1913. The trail leads to a lush fern forest and through a massive, moist lava tube that once had a river of yellow lava running through it. Thurston Lava Tube is where the tour buses stop; it is one of the busiest spots in the park. If you come before 9 a.m., before the crowds, you might see Hawaiian honeycreepers and hear their sweet songs.

A more strenuous adventure can be found along 4-mile Kīlauea Iki, which starts in a rain forest on the crater rim and descends 400 feet to the crater floor. As you pass through the rain forest on your way down the trail, keep an ear to the tree canopy, where the calls of a brilliant crimson ‘apapane bird, whose only known habitat is Hawai‘i, can often be heard. And keep an eye to the sky, where white-tailed tropicbirds and Hawaiian hawks often soar.

The trail offers ample evidence of the challenges faced by park rangers and volunteers as they attempt to eradicate the non-native plants—particularly Himalayan yellow ginger, a weed with lovely, fragrantly scented yellow blooms—that in many cases are crowding out endemic species.

The crater floor is the site of the last major eruption of Kīlauea Iki (1959). Lava erupted from a vent in the crater wall for five weeks, with one geyser of lava spewing 1,900 feet in the air, setting a record for the highest lava fountain ever measured in Hawai‘i.

The black rock that forms the crater floor across which hikers traverse is actually the hardened surface of the 400-foot-deep lava lake that formed when the eruption occurred. The experience is eerie and unforgettable.

This is the park’s main byway, which begins at the park entrance and heads along the East Rift of Kīlauea before continuing down to the coast, The road drops 3,700 feet in 19 miles before reaching the water. Along the way, signs are posted showing where various eruptions issued forth—a history in lava flows: 1969, 1972, 1979—and scenic overlooks where the devastation and the eventual rebirth of the landscape can be viewed.

About halfway down the road, a turn in the road opens onto a vast panoramic view of the Pacific Ocean. From there, Chain of Craters Road descends quickly to sea level, ending at a natural roadblock, where lava covered the coastal part of the road in 1986. Turn around at Hōlei Sea Arch. Take the short walk to the cliff’s edge to view the sheer drop-off to the crashing waves.

Hilina Pali Road

Turn off Chain of Craters Road onto the 11-mile, one-lane Hilina Pali Road to reach Hilina Pali Overlook. The views from this vantage point are expansive—extending over the 2,000-foot cliff and down to the vast Pacific. From here, you can take the Ka‘ū Desert Trail. This less-traveled 4.8-mile wilderness trail, in one of the park’s most remote areas, skirts the rim of Hilina Pali, offering panoramic ocean views.

The trail is distinctive for the wide, black pāhoehoe lava flows through which it crosses. This is a transition area where water flows in during heavy rains, creating erosion gullies and rivers.

Plants such as Pele’s hair and Pele’s tears, as well as ash, mineral rock, and lava terrain add up to a remarkable tableau as unforgettable as the panoramic views down to the unusual ash dunes near the coast.

Coastal Trails

There are more than 32 miles of Pacific coastline in Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, with more than 20 miles of well-marked trails on or near the water. The trails can be accessed from several points, including Hilina Pali Overlook; the Mau Loa o Mauna Ulu pullout on the Chain of Craters Road; and the Pu‘u Loa parking area, also off Chain of Craters Road.

From Hilina Pali Overlook, the 3.6-mile Hilina Pali Trail to Ka‘aha is a favorite among park visitors. The trail leads down the mountainside via a switchback stone walkway built in the 1930s. The terrain flattens out and traverses a region used for bombing practice during World War II.

At Ka‘aha, broad coastal views reveal numerous sea arches in what is one of the most pristine areas of the park.

From Ka‘aha, you can continue along the Hilina Pali Trail for a 6-mile trek across a magnificent tabletop bluff and then back down to the ocean at Halapē, a favored destination of hearty wilderness hikers.

Though the hike to Halapē can be grueling, the payoff is a small sandy beach where a tent can be pitched (permit required) under palm trees next to the ocean, where rare and endangered Hawaiian hawksbill turtles nest.

The Puna Coast Trail between the Halapē campsite and the Pu‘u Loa trailhead is just over 11 miles; it can be hot many months of the year. The hike leads past ‘Āpua Point, where the ocean is accessible (albeit dangerous: rip tides are common and swimming not recommended), and through vast lava fields.

Across Chain of Craters Road from the Puna Coast Trailhead is the more popular 1-mile Pu‘u Loa Petroglyph Trail, which leads to tens of thousands of ancient Hawaiian rock carvings. It is the largest petroglyph field in Hawai‘i.

Another fascinating, moderately strenuous hike accessed from Chain of Craters Road leads into the Mauna Ulu eruption (1969–1974) area. The Nāpau Trail is a two- to three-hour round-trip.

Be sure to pick up the trail guide that tells the story of one of the most spectacular eruptions in recent memory, described by eyewitness volcanologist Wendell Duffield as “the thrill of a lifetime. The roar of a lava fountain imitates the sound of a full-throttle jet engine in a commercial jetliner. The ground shakes in constant tremor in a primeval form of deep-bass music created by molten rock surging through its tubular eruption pipe on a path to the surface.”

The higher elevations of the park are far less user-friendly and should only be attempted by experienced hikers in extremely good physical condition. It’s more mountaineering than hiking. Conditions can change rapidly near the summit of Mauna Loa, and you have to be ready to bivouac overnight in the wilderness in freezing temperatures and whiteout conditions.

But for those prepared to attain the 13,677-foot-high summit there are rich rewards. The views on a clear day can stretch across the island to sister volcano Mauna Kea (a few feet taller, at 13,803 feet), down to the Kona coast and the Pacific Ocean, and into Moku‘āweoweo Caldera.

The Mauna Loa Trail begins at the Mauna Loa Lookout, a 13.5-mile drive from Hawaii 11 (roughly 15 miles from the Kīlauea Visitor Center), at an elevation of 6,662 feet.

From the lookout, a 7.5-mile trail ascends 3,400 feet through sub-alpine scrubland and above tree line to Red Hill Cabin, with eight bunks (permit required), pit toilets, and a water-catchment tank. Plan on carrying in drinking water.

The trek from Red Hill Cabin to the summit is arduous, and fascinating for its tale of recent geologic history. The trail leads past 1880, 1899, 1942, 1975, and 1984 lava flows. The terrain is a series of fissures leading through the rift zone. There are lava cones where ramparts with lava splatters are seen, and a series of false summits before the real one.

Mauna Loa Cabin is located on the crater rim, a rugged 11.6-mile ascent from Red Hill Cabin. Stays are limited to three nights per cabin site (permit required).

A 4.7-mile trail leads from Mauna Loa Cabin around the rim of Moku‘āweoweo Caldera, to the true summit, with evidence of Mauna Loa’s most recent eruption (three weeks in 1984) clearly visible.

Linger here a while, as it is a memorable accomplishment to arrive at one of the truly grand views in the Pacific.

Information

|

How to Get There From Hilo, drive 30 miles southwest on Hawaii 11 (45 minutes). From Kailua-Kona, drive 96 miles south on Hawaii 11 (2- to 2.5-hour drive). When to Go The park is open year-round. Summer is typically the busiest season, although some of the lower elevation hikes across lava (Ka‘ū Desert Trail, for example) can be hot and dry in summer months. Winter weather can be chilly and wet at mid-level and higher elevations. At the higher elevations of Mauna Loa, blizzards, high winds, and whiteouts are not uncommon any time of year. Visitor Center & Museum Kīlauea Visitor Center is just inside the park’s main entrance; Jaggar Museum is 3 miles farther along on Crater Rim Drive. Both are open year-round. |

Headquarters 1 Crater Rim Drive Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, HI 96718 Camping Operated by concessioner Volcano House (hawaiivolcanohouse.com; 808-756-9625), Nāmakanipaio is a drive-in campground (12 sites and 10 cabins) with restrooms, water, picnic tables, and barbecue pits; Kulanaokuaiki (8 sites) is a walk-in camping area, available on a first-come, first-served basis. Lodging Historic Volcano House (hawaiivolcanohouse.com; 808-756-9625), built in 1846, is across Crater Rim Drive from park headquarters. For places to stay outside the park visit: gohawaii.com/en/big-island. |

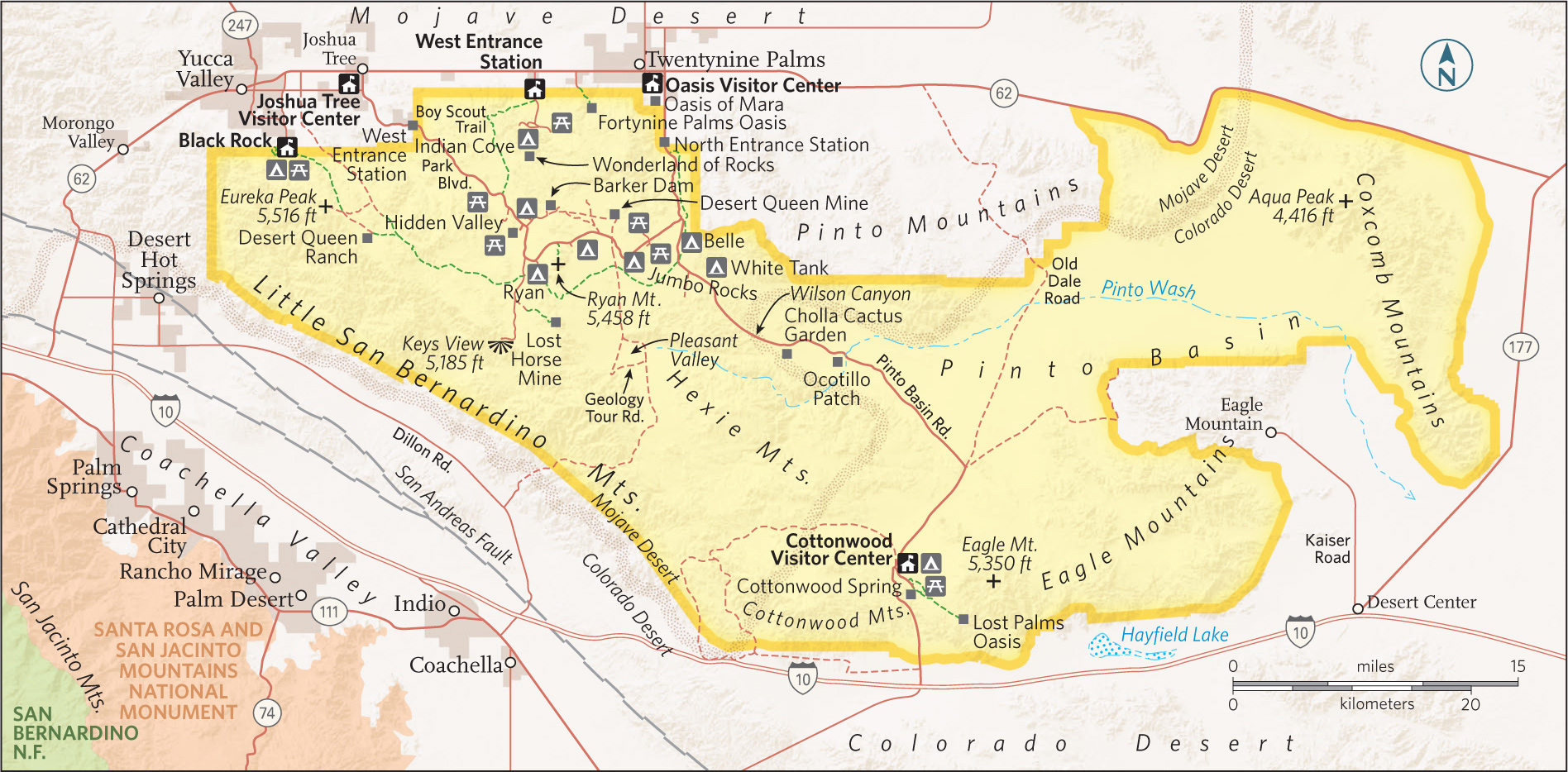

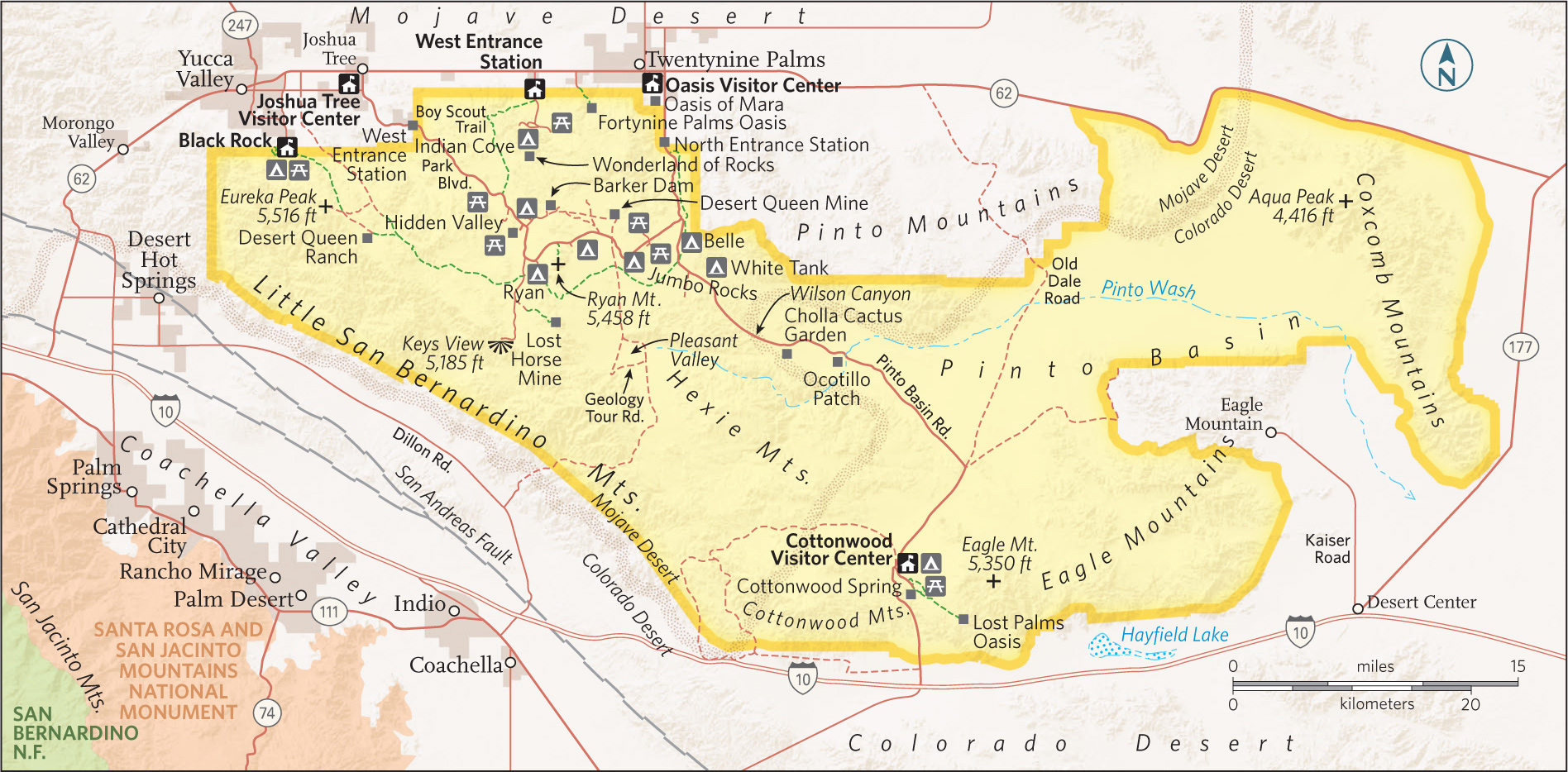

Joshua trees etched against the sky at sunset

California

Established October 31, 1994

794,000 acres

The signature spiny tree with the upturned branches accounts for the park’s name, but the enduring appeal of Joshua Tree National Park derives from its wide-open desert spaces spiced with arid mountain ranges and fantastic boulder formations. The transition from high Mojave Desert to low Colorado desert and echoes of tough old desert prospectors add to the park’s fascinations.

Joshua Tree almost immediately dispels the notion that a desert is an austere, monochromatic place. Abundance prevails here, not only in terms of surprisingly dense and varied vegetation, but also in the textures of the landscape. Every view in every direction in the park takes in at least one rugged mountain range or a massive pile of stacked boulders, to the delight of rock climbers from all over the world.

As for vegetation, Joshua trees dominate the higher elevations (between 2,500 and 4,000 feet) of the park’s northern half. But desert life is extremely sensitive to elevation change. When you drop in elevation, creosote bushes and Mojave yuccas steal the show. Enter or cross a wash and suddenly you’re amid smoke trees and palo verde. Native fan palms rise high in desert oases. Whimsical plants like ocotillo and cholla cactus also vie for attention, and wildflowers put on a dazzling show in spring—and occasionally in fall, after summer thunderstorms. Little wonder that early park advocates wanted to call it Desert Plants National Park.

► HOW TO VISIT

It’s possible to drive all of Joshua Tree’s paved roads in a single, hurried day, but if possible, allow at least a couple of days in the park to appreciate the distinct character of both high and low desert. A swing from west to east along Park Boulevard serves up an excellent cross-section of the park. Adding time for Pinto Basin Road to the south spotlights the transition from Mojave to Colorado Desert. Note: The park has no gas or food.

Park Boulevard West

First-time visitors should consider approaching via the town of Joshua Tree and the park’s West Entrance. Here Park Boulevard threads through a landscape that is classic high Mojave desert, replete with forests of Joshua trees. This approach ensures some time in Hidden Valley, where a 1-mile nature trail leaves from a picnic area and winds among towering boulders; watch for rock climbers belaying one another on formations such as Sports Challenge and Hidden Tower. Interpretive signs point out the variety of cactus, shrubs, and trees. All the while, you can imagine this secluded enclave as the hideout of cattle and horse rustlers who used the valley to stash and rebrand their ill-gotten charges.

A half mile down Barker Dam Road from Park Boulevard and Hidden Valley are the entrances to Keys Ranch and Barker Dam. Both manifest the legacy of Bill Keys, who mastered the art of thriving in the harsh desert environment—from 1907 to 1969. With reservations, you can tour Keys Ranch and see how he managed to tend and water crops and fruit orchards and provide for a family of nine. Even if you miss the tour, you can take the 1.1-mile loop walk to Barker Dam, one of Keys’s chief water sources. Following winter or summer rains, a lake backs up behind the dam and provides the unlikely spectacle of shorebirds wading in the middle of the Mojave. On the same walk is an overhanging boulder decorated with native petroglyphs that are just a bit too vivid—they were shamefully “enhanced” by a Hollywood film crew in the early 1960s. The original work was either Serrano or Chemehuevi; no one is certain. Also from the Barker Dam parking area, a 1.1-mile trail leads to Wall Street Mill, a stamp mill built by Keys to process ore from his Desert Queen Mine. Here ghostly ruins can be inspected up close, including old utility trucks slowly decaying in the desert sand.

A couple of miles south of Hidden Valley is the Ryan area and the intersection with Keys View Road. A 5-mile side trip leads to Keys View, where views stretch to Mount San Jacinto (10,500 feet) rising above the low-desert Coachella Valley. On the way to Keys View is Lost Horse Valley, probably the densest stand of Joshua trees in the park.

Back on Park Boulevard, adjacent to Ryan Campground, take the 0.5-mile walk to the impressive adobe ruins of Ryan Ranch, homesteaded by Jep and Tom Ryan in the 1890s. A bit farther along, just after Park Boulevard. swings east, is the 5,461-foot summit that bears their name. A 1.5-mile trail climbs to the top of Ryan Mountain and serves up a glorious view of all of Joshua Tree.

Park Boulevard Central

Between Ryan Mountain and Pinto Basin Road, a 9-mile stretch of Park Boulevard connects a string of sights including favorite rock-climbing spots such as Hall of Horrors and Oyster Bar. About 5 miles from Ryan Mountain, a side trip down Geology Tour Road, an 18-mile round-trip, takes sights, from washes to dry lakes to granite boulders, that represent the full variety of desert geology. High clearance and four-wheel-drive are required to make the full drive. Just across Park Boulevard is a 1-mile side trip to Desert Queen Mine. A half-mile walk from the trailhead leads to a lookout above the ruins and mine shafts of Mojave’s most productive and longest-running mine.

Back on Park Boulevard, Jumbo Rocks is another renowned climbing site, and a favored campground as well, where sites are framed by towering boulders. About 0.5 miles farther along, Skull Rock stands just beside the road—shaded indentations in a giant boulder make it look like a giant, sunbaked granite cranium. Less than a mile beyond, Skull Rock forms the intersection of two popular picnic areas—Live Oak and Split Rock.

Pinto Basin Road

At the intersection of Park Boulevard and Pinto Basin Road, known as Pinto Wye, you can exit the park to the north or venture south to experience the transition from high Mojave Desert to low Colorado Desert. Park Boulevard leads 8 miles north to the Oasis Visitor Center and the Oasis of Mara, where palm trees signify the site of an old Serrano Indian settlement.

Pinto Basin Road leads south from Pinto Wye, dropping down to the Colorado Desert en route to the Cottonwood Visitor Center. The road passes by two of the park’s smaller campgrounds—Belle (18 sites) and White Tank (15 sites). From White Tank, a 0.3-mile loop walk leads to Arch Rock. The granite arch spans about 35 feet and rises 15 feet high. From White Tank the road descends about 2,000 feet into the broad Pinto Basin, dominated by seemingly endless expanses of creosote.

As you make the transition into the Colorado Desert, framed by the Pinto Mountains to the east and the Hexie Mountains to the west, it feels even more wild and remote than the more lush high desert. Along the way, two stops showcase some of the park’s more unusual plants. In the Cholla Cactus Garden (10 miles from Pinto Wye), a trail winds amid a wide expanse of cholla, a cactus that looks more fuzzy than spiny, but it’s assuredly a look-but-don’t-touch plant. One mile south is Ocotillo Patch. The tall, spindly plant is one of the signatures of the Colorado Desert. Its lanky stems rise some 12 feet high. When moisture is available, ocotillo produce green leaves and sprout orange-red flowers.

Thirty miles south of Pinto Wye is the Cottonwood Visitor Center, a campground, and the trailhead for a short walk into Cottonwood Spring Oasis. You may or may not see water seeping from the spring, but you’ll see evidence of its presence—notably the tall fan-palm and cottonwood trees, which are often filled with songbirds. Like any water source in the desert, these springs attract wildlife, so approach quietly and you might spot a bighorn sheep or a coyote grabbing a drink.

South of Cottonwood, Pinto Basin Road cuts through Cottonwood Canyon, an area frequented by bighorn sheep. The road flirts with a broad, sandy wash whose dominant plant is the distinctive smoke tree, a Colorado Desert denizen whose branches look like puffs of smoke. Seven miles south of Cottonwood, the road exits the park and joins I–10.

Black Rock & Indian Cove

Two areas of the park accessed from the north via Calif. 62 are not connected by road with the rest of the park. In the northwest part of Joshua Tree is Black Rock, a favorite with hikers for its access to trails in the high, rocky hills above the campground. Indian Cove is in the north-central part of Joshua Tree, where campsites are situated on the edge of a vast maze of boulders known as the Wonderland of Rocks. The boulder piles stretch several miles south, clear to the Barker Dam area near Hidden Valley.

Information

|

How to Get There To enter Joshua Tree’s high-desert north, take Calif. 62 west from Palm Springs to park entrances in Yucca Valley (28 miles), Joshua Tree (35 miles), or Twentynine Palms (48 miles). To enter from the south, take I–10 to Cottonwood Springs Rd., 50 miles from Palm Springs. When to Go The park is open year-round. Spring and fall are the most popular times to visit. Spring is particularly nice: Rainy winters bring out showy displays of wildflowers. Winters can be pleasant though chilly. Summers are very hot, and thunderstorms are occasionally fierce. Visitor Centers & Nature Center Oasis Visitor Center at headquarters is three blocks south of Calif. 62 on Utah Trail in Twentynine Palms; Joshua Tree Visitor Center, just south of Calif. 62 on Park Blvd. in Joshua Tree; Cottonwood Visitor Center, 6 miles north of I-10; Black Rock Nature Center is adjacent to the campground in Yucca Valley. |

Headquarters 74485 National Park Dr. Camping The park has eight campgrounds (401 sites). Most camping is first come, first served, but sites at Black Rock and Indian Cove can be reserved Oct.–May (recreation.gov; 877-444-6777). Lodging There is no lodging inside the park. Motels and inns can be found in the towns of Yucca Valley (yuccavalley.org), Joshua Tree (joshuatreechamber.org), and Twentynine Palms (29chamber.org). Safety Temperatures can be extreme—hot summer days and cold winter nights. Beyond visitor centers, water is available only at park campgrounds. Carry at least a gallon of water per person per day. |

The park’s namesakes are the eroded leftovers of an extinct volcano.

California

Established January 10, 2013

27,214 acres

Pinnacles—America’s newest national park—is a geologic playground, a rumpled volcanic landscape of protruding lava spires, massive rocky bastions, and crenellated cliffs interlaced with dense, woody chaparral and woodlands of oak and pine. Located in west-central California, in the Gabilan Range (part of the Coast Range), Pinnacles National Park offers 32 miles of hiking trails and an impressive roster of fauna (there are more than 500 species of moths in the park alone).

According to geologists, the jutting volcanic spires that make Pinnacles so uniquely picturesque originated some 23 million years ago in the Neenach Formation of volcanoes and lava flows near present-day Lancaster, California, 195 miles southeast of the park. Formidable tectonic pressures slowly, over millennia, moved part of the Neenach Formation northwest along the San Andreas Fault to the park’s current location. The inexorable forces of water and wind erosion helped sculpt today’s awe-inspiring geologic display. The story, however, is far from over. Geologists estimate that Pinnacles is moving northwest along the San Andreas Fault—in the direction of San Francisco—at an average of two inches a year.

The haunting beauty of this region spurred early conservationists—particularly local homesteader Schuyler Hain—to propose protection for the area in the 1890s and early 1900s. President Theodore Roosevelt designated Pinnacles a national monument on January 16, 1908, protecting 2,060 acres of the region’s most prominent volcanic formations.

Over the years the monument expanded as new acreage was added. By the time Pinnacles National Park was established, nearly half its acreage was designated Wilderness.

Pinnacles is a wonderland of wild plants and animals. Large mammals—mountain lions (elusive and rarely seen), gray foxes, and bobcats—abide along with black-tailed deer, rabbits, songbirds, raptors, and the distinctive California condor. Eight lizard and 13 snake species (including rattlers) also call Pinnacles home. If you stay late, watch and listen for bats: 14 species of bats fly the night sky. The greatest diversity of wildlife, though, is found among smaller species, with 40 species of dragonflies; 70 of butterflies; 400 of bees; and 500+ of moths. Some 80 percent of the park is chaparral—dense, low-growing vegetation that blankets the more arid parts of the park.

Along streambeds and in moister areas, valley oaks, sycamores, cottonwoods, and buckeyes provide welcome shade. And, in spring, plenty of wildflowers splash color across the landscape: goldfields, bush lupine, poppies, paintbrush, and sticky monkeyflower, among others.

► HOW TO VISIT

A reality of visiting Pinnacles is that there is an entrance on the east side of the park and one on the west, but the roads do not connect. The drive from one side to the other requires a 90-minute trip outside the park.

Most visitors come primarily to hike or climb. Park officials caution that the rocks are primarily volcanic rhyolite and tuff, which are often soft and crumbly. Check on conditions with a ranger before climbing.

Both the East Entrance and the West Entrance offer multiple opportunities for easy to strenuous hikes, for exploring talus caves, and for rock climbing, wildflower spotting, wildlife watching, and night-sky viewing. A note of caution: Pinnacles is in an arid climate and, particularly in summer, can be very hot (over 100°F) and dry. And temperatures can swing more than 50 degrees in a given 24-hour period.

East Entrance

The East Entrance to Pinnacles is one of the two park gateways that offer access to hiking trails. About 2 miles into the park, stop at the Pinnacles Visitor Center to view exhibits, find park information, and discuss hikes with a ranger. Limited supplies—including drinking water—are available here. The only campground in the park, Pinnacles Campground, is near the visitor center, and a picnic area is close by.

The moderately easy Bench Trail winds from the campground along Chalone and Bear Creeks. Bench Trail—dotted with California poppies in spring—provides access to numerous other trails, including the moderate 6.5-mile round-trip South Wilderness Trail, which branches off from the Bench Trail. Watch for a trail marker on the right, about a quarter mile from the campground.

Continue driving for a couple of miles and turn left into the Bear Gulch Day Use Area, which includes park headquarters, trailheads, and the Bear Gulch Nature Center. Open seasonally, the nature center has a topographic relief map and displays about the park’s natural features and history. The trailhead for the strenuous 5.3-mile Condor Gulch-High Peaks Loop Trail is located here. This trail takes hikers 1,500 feet into the High Peaks, the heart of Pinnacles.

About a quarter mile farther is a parking area for several trails. The moderate 2.2-mile Moses Spring-Rim Trail Loop winds through woodlands to views of rock formations. Off the Moses Spring Trail is one of the park’s “caves,” with a trail running through it. The Bear Gulch Cave is actually a talus cave, a narrow canyon that has filled in with rockfall; over time, flowing water has eroded a passage that hikers (with large flashlights or headlamps) can pass through. Check with a ranger before hiking here.

At the reservoir at the end of the Moses Spring Trail, the Chalone Peak Trail leads 3.3 miles to the top of North Chalone Peak, at 3,304 feet the highest point in the park.

West Entrance

The Visitor Contact Station, just inside the park boundary, has exhibits, rangers to help with planning, and an excellent brief video on the features and history of Pinnacles.

At the end of Calif. 146 is the Chaparral Trailhead parking area, access point for several trails. The moderate 2.4-mile clockwise Balconies Cliffs–Balconies Cave Loop Trail winds past a precipitous slab of rock called Machete Ridge and into the massive Balconies Cliffs. This russet-hued range soars above. The trail drops into a valley where the 0.4-mile Balconies Cave Trail meanders through another talus cave.

The strenuous 9.3-mile unmaintained North Wilderness Trail climbs among the ridgetops and descends to the Old Pinnacles Trail, which links to the Balconies Trail and back to the parking area. Finally the strenuous 4.3-mile Juniper Canyon Trail loops upward into the High Peaks range. In the springtime, the first half mile of this Juniper Canyon Trail is a riot of resplendent wildflowers, including yellow fiddlenecks.

Information

|

How to Get There To reach the East Entrance, follow Calif. 25 south from Hollister, CA, then turn west on Calif. 146. To reach the East Entrance from the south, follow Calif. 25 north and turn west on Calif. 146. For the West Entrance, head east on Calif. 146 from Soledad, CA. Calif. 46 is a steep, winding road that for much of the way is no wider than one and a half lanes. An automatic gate at the West Entrance opens at 7:30 a.m. and closes at 8:00 p.m. When to Go The park is open year-round. Mid-Feb.–early June is ideal: wildflowers are blooming, and the heat is not yet intense. Summer through early fall can be very hot and dry. Later fall brings colorful foliage. Weekends can be quite crowded. Visitor Center & Visitor Contact Station The Pinnacles Visitor Center at the East Entrance, open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., has exhibits and a small bookstore. |

The West Side Visitor Contact Station offers a short video on the park. Rangers are available at both the visitor center and contact center to provide information and help plan hikes. Headquarters 5000 Highway 146 Camping The park’s only campground (149 sites; showers) is near the Pinnacles Visitor Center at the East Entrance. For reservations: recreation.gov; 877-444-6777. Lodging There is no lodging in the park. Places to stay can be found in Soledad (ci.soledad.ca.us) and Hollister (hollister.ca.gov) or in Salinas (ci.salinas.ca.us), a larger city with opportunities for visiting both sides of the park. |

Horses work the trail.

California

Sequoia

Established September 25, 1890

Kings Canyon

Established March 4, 1940

865,964 acres (total)

The largest tree on earth (by volume). The highest mountain in the contiguous United States. One of the deepest canyons in North America. Some of the most remote wilderness in the Lower 48. It’s all about grand scale in Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks—and yet these adjoining and jointly administered parks also offer a multitude of intimate natural treasures and experiences, in the backcountry as well as closer to the heart of things.

“Going to the woods is going home,” wrote 19th-century naturalist and conservationist John Muir, and few woodlands were as important to him as his “giant forest” of sequoias—the epicenter of Sequoia National Park. Muir and many other like-minded thinkers, decried the wholesale logging of sequoias and other trees throughout the Sierra Nevada and fought to preserve them. Their efforts were rewarded when Sequoia was established as the nation’s second national park. A week after this announcement, the amount of protected lands tripled with the addition of Grant Grove National Park—now part of Kings Canyon. Over the next century, the two parks expanded and now encompass more than 1,300 square miles. More than 93 percent of the parks are designated wilderness land.

More than 826 miles of hiking trails—including the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail—penetrate the High Sierra, a wonderland for backpackers. Mount Whitney, at 14,494 feet the highest peak in the United States outside of Alaska, is a beloved destination.

Casual visitors and day hikers have ample opportunities to explore sequoia groves, marble caves, glacier-carved canyons, rampaging rivers, surging waterfalls, and much more. There are more than 30 distinct sequoia groves in the two parks, including the most visited, Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park and Grant Grove in Kings Canyon. These groves, particularly in the early morning and early evening when the crowds are thinner and the sunlight softer, evoke an aura of solemnity and majesty; people often refer to them as outdoor cathedrals. And the imposing height and girth of the sequoias themselves inspire an enduring sense of awe. Mixed in with the sequoia trees are white fir, sugar pine, yellow pine, and incense cedar.

► HOW TO VISIT

Visitors with limited time should certainly drive Generals Highway, making several short stops between the Giant Forest and Grant Grove, with some of the largest trees on Earth. Relatively easy hiking trails meander through these two sequoia groves and yield a sense of the grandeur of the mammoth trees.

Devoting two to four days will allow for a much fuller appreciation of the diversity of what Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks have to offer: a tour of sparkling Crystal Cave; a Moro Rock climb, with breathtaking views; a spellbinding drive along the Kings Canyon Scenic Byway into the canyon of the South Fork Kings River; and a steep, narrow, and winding drive up to the scenic Mineral King region of Sequoia National Park.

Generals Highway

From Calif. 198 via the Ash Mountain Entrance, drive the Generals High-way for approximately 50 miles through the heart of the developed area of Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks. Just northeast of the entrance is the Foothills Visitor Center, with exhibits on the low-lying chaparral ecosystem of this part of the park. The Wilderness Office, where information and permits relating to overnight backpacking and camping can be obtained, is in a separate building nearby.

Six miles on, stop at Hospital Rock to see outdoor exhibits about Native Americans. Here, members of the Western Mono people lived from prehistoric times to the late 1800s. Their pictographs and bedrock mortars—hollowed-out depressions in the rock for grinding acorns into flour—can be seen here.

The twisting, switchbacking Generals Highway soon leads to the turnoff to Crystal Cave, which is open late May through fall, weather permitting. A tour of the cave must be planned in advance; tickets for the 45-minute tour can be purchased at either the Foothills or Lodgepole Visitor Centers.

Tour participants meet at the parking area, descend a steep half-mile paved path along a canyon wall, and enter the cave, which stays at a constant 50°F. The cave gets its name from its unique geology—it is formed of glistening marble (not the usual limestone of most caves), and the marble formations glimmer and reflect light in stunning displays.

The Generals Highway soon reaches the Giant Forest area. Stop at the excellent Giant Forest Museum to gain an overview of the sequoia ecosystem. The 1-mile paved Big Trees Trail departs from the museum and loops through a spectacular sequoia grove. For a unique perspective on the Giant Forest, climb Moro Rock, the road to which closes with snow. Moro Rock is a towering granite dome that juts to an elevation of 6,725 feet. Some 400 steps carved into the rock (along with occasional rest areas) lead to the top, with exceptional views of the surrounding woodlands and, on clear days, the Coast Range, some 100 miles west.