Wrangell Mountains, Wrangell–St. Elias National Park

In 1867 Secretary of State William Seward bought Alaska from Russia for two cents an acre—and the public labeled the vast empty land Seward’s Folly. Today, more than 17 billion barrels of oil have gushed through the Prudhoe Bay pipeline, while Alaska’s protected wilderness and wildlife attract visitors by the thousands.

Picture Alaska in your mind, and a number of scenes materialize: huge brown bears fishing for salmon; rugged coastline where glaciers calve icebergs into the sea; Denali, the highest peak in North America; herds of caribou migrating across tundra; broad rivers where rafters float for days, far from signs of civilization; and even a field of sand dunes north of the Arctic Circle.

Eight national parks protect more than 41 million acres of these natural treasures. Katmai and Lake Clark lie along the Pacific Ring of Fire—a region of active volcanoes, earthquakes, giant brown bears, and salmon. Whales, sea lions, and flocks of seabirds seek out the cold, food-laden waters of Glacier Bay and Kenai Fjords. Wrangell–St. Elias is a jumble of mountains and glaciers so rugged that many remain untrodden by humans. Above the Arctic Circle, Gates of the Arctic and Kobuk Valley protect the tundra and migrant herds of caribou. By comparison, Denali seems “civilized,” with its nearby railroad and hotels; yet here the wildlife is so abundant and so visible that the park is referred to as a “subarctic Serengeti.”

Alaska parks include national preserves that allow hunting, vast wilderness areas that prohibit buildings and roads, and native-owned lands still used for subsistence in a tradition thousands of years old.

While parks work to protect what’s wild, man’s hand doesn’t always help matters. The Exxon Valdez accident in 1989 underscores the potential for long-term consequences for the habitat.

Denali (20,310 feet)

Alaska

Established February 26, 1917

6,075,029 acres

There’s no best way to take on Denali National Park. It’s miles and miles of possibilities. Of all of Alaska’s parks, Denali offers the widest range of experiences—from simple nature walks and guided bus tours deep into the park to backpacking trips across the tundra, and, for winter travelers, multiday backcountry dog-mushing trips. And for the most adventurous? An expedition on “The High One.”

It often surprises people to find that Denali—originally called Mount McKinley National Park—wasn’t created in honor of the park’s namesake mountain. Actually, it all started with the Dall sheep. Hunter-naturalist Charles Sheldon visited the land during the summer of 1906 and became extraordinarily interested in the animals, writing that he was “determined to return and devote a year to their study.” On that return visit, just a year later, he became ever more entranced with the wildlife and the landscapes. His experiences in the park and his conversations with a guide, Harry Karstens, gave way to ideas about preservation.

Denali offers surprises at every turn. The sun may catch Polychrome Pass just so, exploding the colors of the volcanic rock and plants that grow low on the tundra. A golden eagle may take flight from a ridgeline, or one of the park’s blond Toklat grizzlies may amble through a valley. Or you might hear the whistling of a hoary marmot as it warns family members of a predator in the area.

► HOW TO VISIT

The park grabs the attention of some 500,000 people a year. Its only thoroughfare is the 92-mile Denali Park Road. With private vehicles restricted to the first 15 miles of the road, the way farther in is by bus, foot, bicycle (bring your own), snowshoe, or dog sled.

First-time visitors shouldn’t shortchange themselves: Denali is not the kind of place that you can “do” in a day. Or a month, really. Give yourself at least two days (camping out if you can), so you have enough time to travel by both bus and foot, and take in a ranger-led program or two. No matter how you take on Denali, book as much of your adventure ahead of time as possible. Lodging in and around the park can fill up quickly for the peak season of July and August.

Denali Park Road: Bus Options

The Denali Park Road’s 92 miles wend through splendid landscapes—past rivers, through mountain passes painted with wildflowers, and—fingers crossed—by Dall sheep and grizzlies. If you don’t win a spot in the annual road lottery, you can’t make the drive on your own unless you have a camping reservation at the Teklanika River Campground at Mile 29.

Limiting vehicle traffic helps preserve wildlife-viewing opportunities near the road. Park visitors have to take a tour bus or shuttle bus if they want to go beyond the Savage River Check Station. The Park Road drive can be a nail-biter, so leaving it to the professionals isn’t a bad idea.

The park offers three narrated tour bus trips, running from 4.5 to 12 hours, with bus drivers constantly on the lookout for wildlife. For those short on time, the Denali Natural History Tour is an easy choice. Traveling just 17 miles along the road to Primrose Ridge, the tour focuses on people who have used this land stretching back thousands of years.

Photography buffs—and others who want to focus on the animals and plants of Denali—should take the seven- to eight-hour Tundra Wilderness Tour. The bus turns around at Toklat River (Mile 53) and Stony Overlook (Mile 62), both known for spectacular mountain views.

Though it makes for a long day (it’s not unusual to see people napping on the way back), the best way to get an overview of the park is through the 11- to 12-hour Kantishna Experience. The tour runs the full length of the road out to the historic mining community of Kantishna. Given that there’s usually snow at the end of the road into late May, this tour isn’t offered until early June.

If hiking or backcountry camping is in your plans, skip the tour bus in favor of one of the park shuttle buses or a camper bus. There’s no narration on these buses, though most of the drivers are happy to answer questions (try to hold off as they’re making some of the more head-spinning turns along the road). And of course, the drivers stop for wildlife.

The shuttle buses offer a good deal of flexibility. You can hop off at any time to embark on a hike or simply take a stroll. When you’re ready to continue along or head back, just flag down a bus. On busy days you may have to wait a while before a bus with an empty seat shows up. Camper buses, which run June to September, have room for gear and bikes.

Scenic Stops Along the Way

The Savage River Bridge (Mile 14.8) marks the farthest advance of a glacier that flowed north out of the Alaska Range and across the valley thousands of years ago. A short way on, the road winds below Primrose Ridge before dropping into a marshy flat with spruce trees leaning every which way—the result of permafrost thaws that cause the land to slump.

Before crossing the Teklanika River Bridge, get your camera so you can photograph the river below. For an even better vantage, continue on to the Tek Rest Area, about a mile east of the bridge at Mile 30. At Mile 34, you’ll pass Igloo Mountain and Cathedral Mountain—favorite hangouts of Dall sheep. One of the best spots to watch for grizzly bears is Sable Pass (Mile 39). This is the only portion of the park closed to foot traffic. Sable Pass is richly endowed with the various roots and berries that grizzlies favor.

After the pass, the road climbs to what should be a mandatory stop: Plains of Murie, which overlooks Polychrome Pass. From this vantage point, Denali can appear as though it was painted onto the sky. The colors can be so vivid that it all looks unreal.

It was in the area of Mile 53 that Charles Sheldon wintered in 1907 and fell in love with the land and the animals. He would spend the next nine years lobbying for the creation of a national park.

Shortly beyond, bicyclists should remember to keep breathing as the road climbs to its highest point, Highway Pass (3,980 feet). The next climb, to Stony Hill Overlook, may, weather permitting, bring on oohs and aahs as Denali—just under 40 miles away—comes into view. This high ground is favored by the park’s caribou herd.

At Mile 66, take a break to explore the Eielson Visitor Center, where (once again, weather permitting) the viewing areas put Denali in the spotlight. For another take on the landscape around Eielson (and one that rivals Polychrome for color), step inside to see artist Ree Nancarrow’s “Seasons of Denali” quilt.

Some of the best photography spots beyond Eielson include Wonder Lake and along the moderate 1.5-mile trail from the Wonder Lake Campground Reflection Pond (Mile 85).

Biking the park road with the Alaska Range in the background

Hiking & Biking the Park Road

One of the best times to bike the Denali Park Road is late spring, just before the buses begin running. Secure a spot at Riley Creek Campground—no reservations are necessary before the peak season begins—and pedal or drive your bike to the Teklanika River. Bring plenty of food and water; there’s none available along the way.

If exploring the park in winter appeals to you, you’re in luck. During the winter months, snowshoers and cross-country skiers pretty much have the road to themselves.

No matter how you travel the road, on clear days you can get a glimpse of Denali, the mountain once known as Mount McKinley, starting at Mile 9. But even if the mountain is hiding in the clouds during your visit, the road offers a near-endless supply of delights.

Off Road

Few spots in Denali are off-limits to hikers. Unless you have experience with backcountry hiking, however, ask the rangers at the visitor center to help you match a hike with your skill set. Be sure to bring maps, water, food, and extra clothing with you. The park has a small number of maintained trails, ranging from simple nature walks (many of these close to the visitor center) to the challenging Mount Healy Overlook Trail, a 9-mile out-and-back hike that climbs some 1,700 feet in less than 4.5 miles.

Whether on trail or off, pack out everything you bring in. And, when off-trail, make sure you and your fellow hikers spread out. This helps ensure that your touch on the land is light.

Another worthwhile hike takes you to Primrose Ridge, which gets its name from a purple flower that grows only in the park. Primrose Ridge Trail is favored by birders. Start your hike from the west side of Savage River Canyon or one of the ridges west of Savage River (Mile 17 to 20). The new 4-mile Savage Alpine Trail is a good alternative to Primrose Ridge that gets you above tree line.

Sled Dog Kennels

For dependable animal sighting, there’s no better stop than the sled dog kennels. The dogs are used to patrolling the wilderness core of the park, which is closed to snowmobiles. During summer months, three times a day, rangers share information on the importance of dog teams in the national park—and demonstrate the power and speed of the resident huskies. (Buses leave the Denali Visitor Center for the kennel programs.) The kennels are also open to visitors during the winter months, though there’s no guarantee the dogs will be home—that’s their working season.

Information

|

How to Get There From the Anchorage area, proceed north on the George Parks Hwy. From Fairbanks, drive south on the George Parks Hwy. The Alaska Railroad offers daily service from Anchorage and Fairbanks from mid-May to mid-Sept.; in winter, weekends only. Visitor Centers Denali Visitor Center, Mile 1.5 on the Park Road; Wilderness Access Center (for park buses and campground reservations), Mile 1; Eielson Visitor Center, Mile 66 (accessible by park bus); Murie Science and Learning Center, Mile 1.4, serves as the winter visitor center. Climbers must stop at the Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station, 100 miles south of the entrance, for permits. Headquarters Mile 3 on the Park Road |

When to Go Summer solstice (June 20 or 21) brings 21 hours of sunlight to Denali. July usually offers the best weather. Open year-round, the park offers the most services from late May to mid-Sept. The park explodes with fall color late Aug. or early Sept. Camping The park’s six campgrounds offer a total of 274 campsites; for details, reservedenali.com. For backcountry camping, permits are available at the Backcountry Information Center (Mile 1 on the Park Road), open mid-May to mid-Sept. Lodging Lodging within the park is found at four private lodges (on private land): Camp Denali & North Face Lodge (campdenali.com); Denali Backcountry Lodge (alaskadenalitravel.com); Kantishna Roadhouse (kantishnaroadhouse.com); and (katair.com/skyline.html). Outside the park, there are many lodging options in the towns of Cantwell and Healy (denalichamber.com). |

Hikers in Thunder Valley

Alaska

Established December 2, 1980

8,400,000 acres

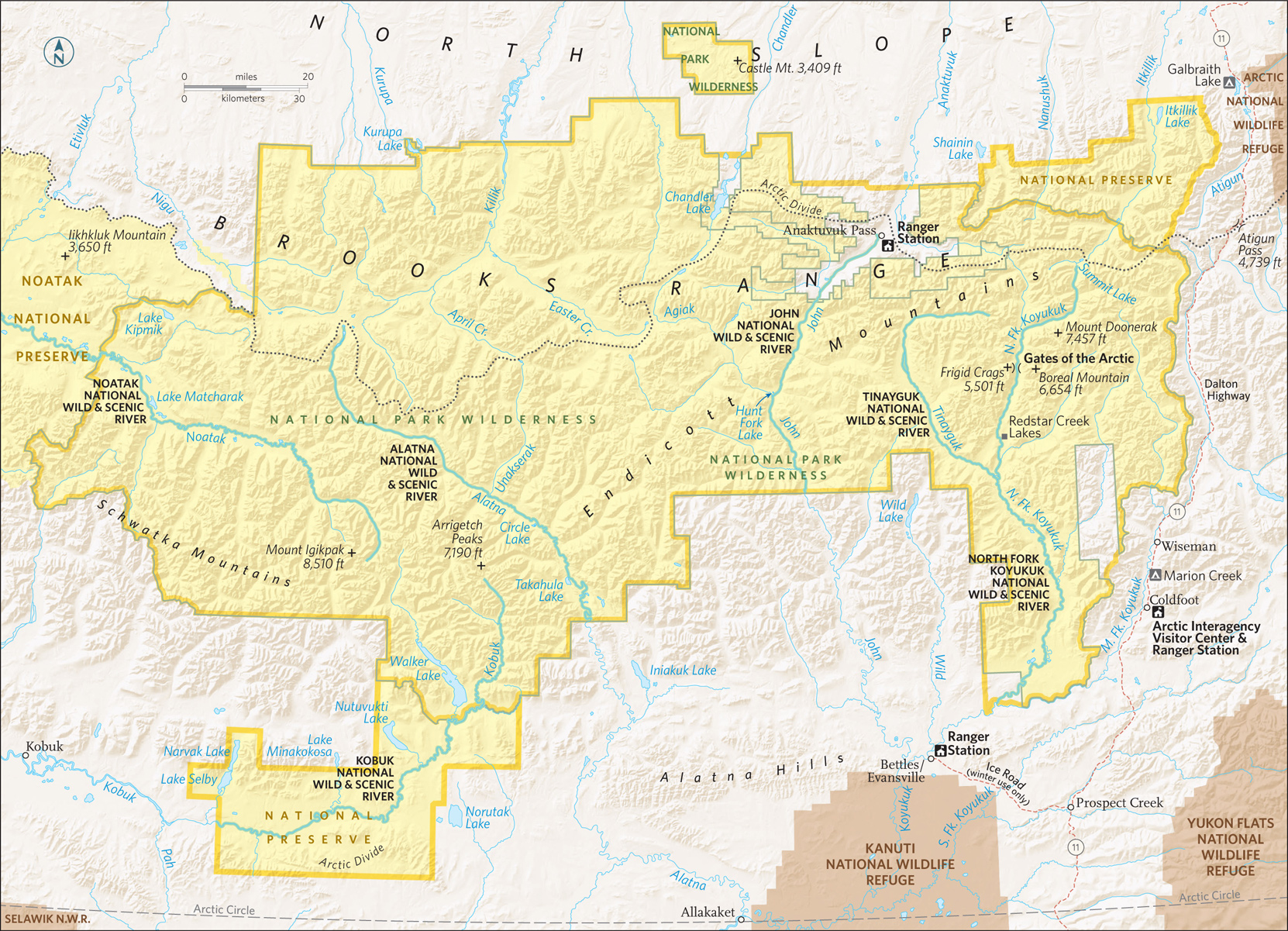

The northernmost national park in the United States, entirely north of the Arctic Circle, Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve is a wilderness landscape of plains between mountains that rise in jagged majesty. It is a rich land populated by Porcupine caribou, musk ox, Dall sheep, grizzlies, black bears, moose, wolves, and waterfowl. Gates of the Arctic is a dramatic reminder of an ancient world.

This is archetypal Alaska, with its towering mountains and wealth of wildlife—to see and hear. Night after night, the haunted howl of wolves fill the air. Gates of the Arctic National Park (and Preserve;) occupies the heart of Alaska. The park is primarily boreal forest, which consists of spruce, birch, willow, and aspen, all stunted by permafrost. Millions of ponds dot the valleys, home to a world of waterfowl.

The park includes the Endicott Mountains to the east and the Schwatka Mountains in the southwest, both sub-ranges of the grand Brooks Range, which stretches more than 700 miles across Alaska and Canada.

Gates of the Arctic is truly remote. The only way to access the park is to fly or hike in, unless you’re really good with sled dogs and extreme winter weather. But charter planes make the entire park accessible to visitors.

The park has no trails; visitors can hike anywhere, though it is important to know that river crossings are cold and dangerous, and that tussocks (clumps of sedge grasses growing in mounds from ground that’s often boggy) can really slow you down.

No matter where you choose to hike, prepare to be challenged. That said, there are few feelings as satisfying as hiking into an arctic valley, looking at a landscape very few ever get to see, and knowing you got there under your own power. Guide services out of Bettles and, to a lesser extent, Coldfoot offer a range of exploration options. Commercial operators offer trips on the Noatak and Alatna Rivers.

Bettles & Flight-Seeing

For most people coming to the park, Bettles is the hub. At first glance, the town looks like little more than a runway and a bar. A few people live here, but a lot more work hereabouts, guiding fishermen out for sheefish, arctic char, and trout; taking hunters to areas outside the park; and guiding campers to the best corners of the park. A stop at park headquarters here is highly recommended for general orientation and for the lecture on bears and safety.

Flight-seeing Gates of the Arctic out of Bettles puts visitors in a position to grasp the park’s diverse landscapes. There are rivers that squeeze through tiny passes between mountains, tundra that looks like a finger-painted garden, and mountains that stretch on seemingly forever.

The Arrigetch Peaks, granite spires topping out at 4,000 feet, rise from the Endicott Mountains. The peaks’ name means “fingers of the outstretched hand” in the Inupiat dialect, but these are more like claws, sharp and jagged.

Anaktuvuk Pass

Several operators in Fairbanks offer day trips to Anaktuvuk Pass, a village surrounded by jagged mountains. The population of the village hovers around 300, and people here live in much as their ancestors did. The villagers remains dependent upon understanding the land: knowing when the caribou are coming; reading weather in the colors of the mountains. Villagers meet flights that are coming in from Fairbanks if they are expecting freight deliveries. At the airport, the villagers sell handsome hand-crafted masks and other traditional objects.

Quite a few rivers in the park make for good canoeing and river-floating (most visitors use collapsible boats). A week on the Alatna River gives visitors a chance to see the diversity of the park, from tundra to forest. Put in at Walker Lake for the Kobuk River, which can be paddled from Gates of the Arctic all the way down to Kobuk Valley National Park. But the glory waterway is the Noatak River, which offers the best way to see the park on a multi-day trip. The Noatak, only a portion of which is in the park, flows east-west, cutting through the park amid rolling mountains and the occasional glacier erratic. On the hills above the river, caribou and musk ox browse the tundra, while grizzly bears seek out caribou and musk ox.

On its journey to the coast from the Brooks Range, the Noatak River travels nearly 400 miles through the largest intact river basin ringed by mountains. Deep wilderness, Noatak Basin is one of the least disturbed natural ecosystems in the world. It was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1976.

The views from the water are spectacular. The Schwatka Mountains form a wall to the south; to the north, lower hills sweep into passes favored by caribou. Beaches are covered in moose tracks. Wolves yip in the middle of the night (which, in summer, is never fully dark).

Jackdaws fly out of willows that hug the river, seeking water to grow. Every now and then the river runs past a pingo (a mound of earth covered by ice). Pingos can be 200 feet high, and when the sun hits them just right, it seems as if they’re glowing.

The river itself is an easy paddle, rarely more than Class I. Paddling experience, though, is recommended for trips in spring, when runoff increases the speed of the water. A number of outfitters run multi-day float trips on the Noatak, usually taking out at Lake Matcharak, which is large enough to accommodate floatplanes.

Information

|

How to Get There Air taxis connect the park with Bettles; it’s easy (although expensive) to get to Bettles or Anaktuvuk Pass from Fairbanks. More remote destinations require additional advance planning. You can drive to Coldfoot, on the Dalton Highway, 280 miles north of Fairbanks, and hike into the park—or charter a plane. In winter, an ice road, built primarily of snow, connects Bettles and Dalton, crossing rivers with no bridges. When to Go The park is open year-round. A winter visit is a challenging and potentially dangerous proposition. July and Aug. are nearly perfect. After the summer, the tundra is washed with autumn color. Visitor Center The park’s visitor center (907-692-5494), in Bettles, is open year-round, daily in summer and weekday afternoons in winter. |

Headquarters Bettles Visitor Center Camping You can camp anywhere in the park; no permit is needed. It is wise, however, to register your itinerary with park officials. Observe all bear precautions, including using bear-resistant food canisters. Take enough extra food and water to allow for being weathered in for a few days—a not uncommon occurrence. Lodging Operated by concessioners, Iniakuk Lake Wilderness Lodge (gofarnorth.com; 877-479-6354) and Peace of Selby Wilderness Lodge (alaskawilderness.net; 907-672-3206) offer cabins in the park. There is one lodging option in Bettles, the concessioner-run Bettles Lodge (bettleslodge.com; 907-692-5111). |

Steller sea lions on South Marble Island

Alaska

Established December 2, 1980

3,280,198 acres

When John Muir came into Glacier Bay for the first time, in 1890, “sunshine streamed through the luminous fringes of the clouds and fell on the green waters of the fiord, the glittering bergs, the crystal bluffs of the vast glacier, the intensely white, far-spreading fields of ice … making a picture of icy wildness unspeakably pure and sublime.” Glacier Bay National Park retains that magic, offering everything you want to see in Alaska, viewable in a single day.

George Vancouver, a British naval officer, sailed this way in 1794 to map the region. There was no bay then, just a 5-mile inlet; all around were mountains and glaciers.

Before Vancouver’s explorations, local Tlingit people, who had called the area home for centuries, were forced to flee 20 miles south when the glaciers suddenly advanced.

Since Vancouver’s time, the ice has retreated some 60 miles, leaving a deep glacial fjord now populated by plants and animals. Today, of all the tidewater glaciers in the park, 13 reach to the Gulf of Alaska.

Most people see Glacier Bay from the deck of a ship. Many cruise companies have itineraries that include the bay, and a park concessioner runs a day boat. Some craft go all the way up to the West Arm.

The eastern arm, Muir Inlet, is the domain of small private boats and kayaks. The only developed hiking trail starts at Bartlett Cove, near headquarters. But you can hike just about anywhere you’d like in the park. The only limits: ice and impassable thickets of alder.

Main Channel

What attracts most visitors is the wildlife, including sea otters, humpback whales, harbor porpoises, and Steller sea lions. A popular spot for the sea lions, which can grow to more than 1,000 pounds, is Marble Islands. It’s not uncommon here to see well more than a hundred sea lions barking and pushing at each other, trying to get the best spots on the sun-warmed rocks.

South Marble Island and other nearby islands are a wonderland for bird-watching—not just southeast Alaska’s usual suspects, bald eagles and ravens, but also cormorants, pigeon guillemots, murres—and the birds that cause everybody to stop and notice: tufted and horned puffins, with their brightly colored beaks. More than 274 species of bird have been spotted in the park.

Past the Marble Islands, the channel divides at Tlingit Point. During the glacial retreat, the ice split around this point, carving out the two arms of Glacier Bay. What was once a single huge river of ice became the Grand Pacific Glacier to the west, Muir Glacier to the east. The point remains a favorite camping spot for kayakers.

West Arm

Ships continue up the West Arm, following the path of the Grand Pacific Glacier and offering misty glimpses of the highest range of coastal mountains in North America, topping out at over 15,300 feet on Mount Fairweather.

From here up to the end of the bay, the water becomes less the usual silver of southeast Alaska and more aquamarine, the result of glacial silt from melt and runoff. Harbor seals gravitate to silt areas, coming here to have pups. In the mountains around the channel there’s still a good chance you could spot mountain goats and maybe even bears.

Mile-wide Margerie Glacier is about 55 miles from Bartlett Cove. Only a mile from the Canadian border, Margerie calves regularly: Huge chunks of ice break off the face of the glacier and crash into the sea. And not only do glacier chunks break off above the waterline, they can do so underneath as well.

A few hundred yards away is Grand Pacific Glacier. Maybe it’s not as grand as it was when it covered the entire bay, but it still stretches back more than 25 miles. Not long before Muir was here, scientists say, Grand Pacific retreated some 10 miles in a ten-year span. It is not retreating now, but it is thinning. Between Grand Pacific and Margerie glaciers, it seems almost as if the world ends here in a wall of sapphire blue ice.

East Arm

The eastern arm of Glacier Bay, Muir Inlet, is a lot quieter and less trafficked than the West Arm. From Tlingit Point, the inlet passes the Plateau Glacier. Most kayakers head to McBride and Burroughs glaciers. Others stick to the main channel, out of Rowless Point, for views of Burroughs and Casement glaciers (west and east, respectively) dramatically framed by jagged crevasses.

The inlet dead-ends at Muir Glacier, about 30 feet tall, 0.5 mile wide, and 12.5 miles long, Muir is retreating quickly: Since 1941, the glacier has moved back more than 7 miles, and has thinned by more than 2,000 feet at its thickest points. The odds are you’ll have the bay just about to yourself here, nothing but you and the masssive, waning glaciers.

Information

|

How to Get There In summer, Alaska Airlines (alaskaair.com) offers daily flights between Juneau and Gustavus, the closest airport to the park (9 miles away); a number of small carriers fly floatplanes and single-engine craft, including Wings of Alaska (wingsofalaska.com) and Alaska Seaplanes (alaskaseaplanes.com). The Alaska Marine Highway (dot.state.ak.us/amhs), the state’s ferry system, runs boats between Juneau and Gustavus twice a week in summer. Private boat and charter planes are the only way to access the park off-season. When to Go Open year-round, the park is most visited between mid-May and mid-Sept. Most services close down the rest of the year. Visitor Centers Glacier Bay Visitor Center and Headquarters are located in Bartlett Cove. For private boat and camping permits, contact the Visitor Information Center (open May through Sept.; 907-697-2627), across from the dock. |

Headquarters P.O. Box 140 Camping The only campground (33 sites) in the national park is in Bartlett Cove, about a quarter mile from headquarters. For backcountry camping, widely available throughout the park, a free permit is required May through Sept., as is attendance at an orientation session, which includes information on dealing with tides and bears. Bear-proof food containers are required. The entire park is bear country (remember, bears can swim). Lodging Concessioner-operated Glacier Bay Lodge (visitglacierbay.com; 888-229-8687), open late May to early Sept, is in Bartlett Cove, along with park headquarters. Nine miles from the park, the town of Gustavus (gustavusak.com) has a wide variety of accommodations. |

Misty Fiords National Monument

Ketchikan, Alaska, area

▷ A natural collage of 3,000-foot sea granite cliffs, steep fjords, and thick rain forests accessible only by boat or small plane. Ketchikan, 22 miles away, serves as the gateway to the Misty Fiords. Visitors can either rent kayaks or arrange to be dropped off and picked up by tour boat to take advantage of the few designated trails for trout and salmon fishing. Guides can be hired. Cabins available. Located 300 miles southeast of Glacier Bay National Park. fs.usda.gov/attmain/tongass/specialplaces; 907-225-2148.

Admiralty Island National Monument

Juneau, Alaska, area

▷ This one-million-acre monument is home to one of the highest concentration of brown bears in the world. Pack Creek, preserved as the Stan Price State Wildlife Sanctuary, offers the best viewing points. Advance reservations required July to late August. Located 15 miles from Juneau, the monument can be accessed by boat or floatplane from Juneau. Located south of Glacier Bay National Park. fs.usda.gov/detail/tongass/recreation/natureviewing/?cid=stelprdb5401890; 907-586-8790.

Near Juneau, Alaska

▷ Thirteen miles long, the Mendenhall Glacier covers the space between the Juneau Icefield and Mendenhall Lake. One of the best views of the expanse comes from the Mendenhall Visitor Center (closed April). From here, several trails branch off and allow visitors alternative views of the glacier, as well as black bears, coyotes, porcupines, snowshoe hares, and mountain goats. Located 14 miles northwest of Glacier Bay National Park via plane or boat. www.fs.usda.gov/detail/tongass/about-forest/offices/?cid=stelprdb5400800; 907-789-0097.

Alaska Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve

Haines, Alaska

▷ Home to the world’s largest concentration of bald eagles, the preserve offers visitors the opportunity to view these majestic birds in their natural environment. The best area from which to view them is from the Haines Highway pullouts between Miles 18 and 22, around the Chilkat River salmon runs. Spotting scopes, interpretive displays, and viewing platforms can be found at the pullouts. Peak eagle-spotting season is October to February. Located 110 miles northeast of Glacier Bay National Park. nr.alaska.gov/parks/units/eagleprv; 907-465-4563.

Chilkat State Park

Haines, Alaska

▷ Visitors can observe bears, moose, whales, seals, sea lions, eagles, blue herons, and a wide variety of shorebirds. Many of these animals as well as the Rainbow and Davidson glaciers can be seen from the log cabin visitor center in the park. Activities include hiking, camping, fishing, and boating. Open mid-May to mid-September. Located 7 miles south of Haines and 100 miles northwest of Glacier Bay National Park. dnr.alaska.gov/parks/aspunits/southeast/chilkatsp; 907-766-2234.

Near Yakutat, Alaska

▷ Russell Fjord Wilderness is home to wolves, mountain goats, brown bears, and black bears including the rare black bears of “blue” coloring that live only near glaciers. The park’s most dramatic geologic features are the Hubbard Glacier and the Russell and Nunatak fjords. The rugged interior can be accessed only via floatplane or boat from Yakutat (12 miles west) or by floatplane from Juneau (200 miles southeast). Located northwest of Glacier Bay National Park. wilderness.net/NWPS/wildView?WID=506; 907-784-3359.

A bear and its quarry

Alaska

Established December 2, 1980

4,093,077 acres

Remote yet easily accessed by floatplane, Katmai National Park hooks visitors from the very start—whether on a day trip to the bear-viewing stations at Brooks Camp, on a float trip down the Alagnak River, or camping in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. The park’s 4 million acres provide a lifetime’s worth of return trips, each one a chance to explore this wild world on a deeper level.

With no roads into the park, every trip to Katmai starts with an adventure of travel by boat or float-plane, over sparkling lakes and powerful rivers, with bear on the shores.

The park got its start in 1918, when President Woodrow Wilson established Katmai National Monument to protect the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, a landscape formed in 1912 when Novarupta Volcano was birthed. The stunning eruption—which went on for 60 hours—was so powerful that more than 100 miles away, skies were darkened with ash.

The bears and the valley are the obvious lures. Opportunities abound for fishing, hiking, kayaking, canoeing, and photography. It’s all just a floatplane ride away.

► HOW TO VISIT

From day trips to weeks-long backcountry adventures, Katmai is a land of outstanding options. If time is short, take a bear-viewing trip on a floatplane out of Kodiak or Homer. For a longer trip that offers a good variety of outdoor experiences—and a great fireplace where you can swap tales with other travelers—head to Brooks Camp.

Brooks Camp & Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes

Brooks is an experience that shouldn’t be missed. Though day-trippers are welcome, it’s best to spend some time at Brooks by booking a cabin—though they’re pricey—or, better, a spot at the campground. Overnighters can hike during the day and wait for the daytrippers to fly back out before heading to the bear-viewing platforms.

There’s a good reason for the mandatory 20-minute ranger and video introduction. The bears are everywhere. But for guaranteed sightings, walk 1 mile from Brooks Camp to one of the three viewing platforms, including the most coveted spot at Brooks Falls. There visitors watch brown bears fish for salmon, hang out under the falls, and, most dramatic of all, go head to head to determine dominance.

If planning to stay at Brooks for more than a day, reserve a spot on the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes tour. After a somewhat slow 23-mile drive—which includes three very bumpy (but fun) stream crossings and stops for a first look into the valley and, of course, for wildlife along the way—the bus arrives at the Robert F. Griggs Visitor Center. Those comfortable hiking in bear country on their own should opt to bring their own lunch and immediately set off down the 1.5-mile trail. Otherwise, sign on for lunch and a hike (fee) in the company of a park ranger. Once in the valley, it’s ash and pumice as far as the eye can see.

For a stunning view of Naknek Lake, hike up Dumpling Mountain. The 8-mile out-and-back trail climbs 800 feet in the first 1.5 miles. The last 2.5 miles to the summit weave through a variety of landscapes, including boreal forest and alpine tundra. Be ready to spot everything from bears to wildflowers, including chocolate lilies, lupine, and wild irises, and foliage that colors the landscape with purples, yellows, reds, and more greens than you ever thought existed.

The much shorter Cultural Site Trail, just 0.1 miles, is a walk back in time, with a quick introduction to the area’s human history, ending at a reconstructed semi-subterranean dwelling (pit house) based on archaeological findings about homes that may have been built here as early as A.D. 1200.

Get a bear’s-eye view of Brooks River by hiring a fishing guide for a few hours. Even inexperienced anglers will get a thrill learning to fly-fish in the company of brown bears.

Water & Air Trips

Experienced paddlers find plenty of challenge and delight on the 80-mile Savonoski Loop. Highlights include an overnight stop at Fures Cabin. A one-room house built of spruce logs by trapper and miner Roy Fure in 1916, it’s now available as a public-use cabin (for reservations, recreation.gov). Or you can take a trip down the braided Savonoski River. Prepare for portages, plenty of bugs, and lots of wind along the way. The full trip, which starts and ends at Brooks Camp, takes between four and ten days.

For a shorter boating trip good for less experienced paddlers, hire a guide to take you to the picturesque Bay of Islands on the North Arm Naknek Lake, 22 miles from Brooks Camp.

But for those who are set on bear-viewing, there might be no greater thrill in Katmai than a day trip in a floatplane to view the animals from on high. Bear guides lead trips from Homer, Kodiak, and many other communities. The pilots know which areas are most likely to have bears at different points in the summer.

Once the animals are spotted from the air, the pilots touch down on the water, and guides lead small groups to view bears from a close—but safe—distance, no viewing platform necessary. Watch as the massive males try to show one another up in the battle for a mate or, at times, take a long snooze after getting their fill of salmon. Some top spots for viewing include Geographic Harbor and Hallo Bay. The flights themselves offer quite a thrill, with the water and land below offering up incredible patterns and colors.

Information

|

Visitor Centers King Salmon Visitor Center, next to the King Salmon Airport. Open year-round. Brooks Camp Visitor Center, reachable by charter plane. Open June to mid-Sept. Headquarters 1000 Silver St. Building 603 How to Get There To get to Brooks Camp, take a regularly scheduled flight from Anchorage on to King Salmon. From there, book an air taxi or powerboat ride for the last hop to Brooks. Plan ahead. For day trips or flights to other areas of the park, including the Pacific coast of the park, charters on a floatplane can be booked from places such as Kodiak, Homer, and Anchorage. Check nps.gov/akso/management/ |

When to Go The park is open year-round. For hiking, fishing, and boating, the best time to visit is June to mid-Sept. July, Sept., and Oct. are peak bear-viewing months. Summer brings changeable weather, with temperatures that can dip into the 30s. Camping The park’s only organized campground is at Brooks Camp. Reservations are required and can be made at recreation.gov. For backcountry camping, there’s no limit to available space in the park. Lodging Lodging within the park is managed by concessioners. Katmailand runs Brooks Lodge and Grosvenor Lodge (info@katmailand; 800-544-0551). Several fishing lodges on privately owned land pepper the park. Check with visitbristolbay.org/ for additional information. |

Aialik Bay with Harris Peninsula in the background

Alaska

Established December 2, 1980

669,983 acres

Sandwiched between the Kenai Mountains and the Gulf of Alaska, Kenai Fjords National Park, the smallest of Alaska’s national parks, brings to life what people who have only dreamed of visiting the state might imagine. Here, for both day-trippers and intrepid adventurers to explore, is a vast swath of ice and snow, glaciers, rocky coastline, bands of forest, and, soaring above it all, bald eagles on the hunt for their next meal.

The ice is the main draw—but it’s just the start. (Add to the mix bears, birds, and, on the glaciers, ice worms.) The Harding Icefield and the more than 30 glaciers it feeds extend over 700 square miles. A remnant of the Pleistocene era, Harding Icefield was once part of a massive ice sheet that blanketed most of what is now Alaska. At thousands of feet thick, ice remains an important part of the landscape, covering some 51 percent of the park. The crown, literally, of Kenai Flords, Harding Icefield is the largest icefield situated completely within the United States.

The best bet for those who want a good overview is to take a day cruise or a flight-seeing trip to see the fjords and the glaciers, and then spend a day hiking to the icefield (or, at least, part of a day to get part of the way—the trail can be quite a challenge). But there also are easy hikes that get you great glacier views. Another way to experience the park is by floatplane or helicopter. The bird’s-eye view underscores the enormity of the park’s icy landscapes. For the unabashedly adventurous? Go deep: Sign up for a multi-day paddling trip.

No matter how you decide to enter the park, for safety’s sake keep an eye out for creatures from the start of your adventure.

Kenai is a birder’s delight, with seabirds nesting along the coastline. Watch for puffins speeding by over the water. Up high, train your eye for peregrine falcons or, walking the treeless slopes, mountain goats. And while you are cruising the water, harbor seals could float by on an ice floe, or an orca might, with no warning, leap high into the air, with shouts of “Did you see that?” coming from your fellow passengers on deck.

Exit Glacier & Harding Icefield

The only section of the park accessible by road, the Exit Glacier area provides several hiking trails to appeal to a wide range of comfort levels. No matter which trail you choose to wander down (or, in some cases, up), bring water, layers of clothing, and, to avoid surprising bears and other wildlife, make noise as you hike.

If you’re after a quick-and-easy chance to look at the glacier, turn left at the Exit Glacier Nature Center and head down the 1-mile wheelchair-accessible trail to Glacier View. For a more challenging option that takes you close enough to the glacier to see its electric robin egg’s blue color, continue on to the 1.2-mile trail to Edge of the Glacier.

If a good workout and a goes-on-forever view of the Harding Icefield sounds like a fine day out, consider the 8.2-mile out-and-back Harding Icefield Trail. The trail climbs about 1,000 feet for each mile on the way up. Good spots to stop along the way include Marmot Meadows at Mile 1.4 and Top of the Cliffs Overlook at Mile 2.4. Keep in mind that there’s usually snow at the top of the trail well into the summer (or, some years, all summer long).

Be prepared to hike on mud and snow or to cut the hike short—you’ll still get in plenty of views of the glacier and icefield. The trail is also open throughout the winter but may be extremely challenging because of ice and deep snow.

On the Water

No matter how many times you hear it, it never gets old. Listening to the crack of a calving glacier—and the splash that follows as the ice bombs into the water—is an unforgettable experience. The best chance to hear that crack is via a full-day boat tour, which covers a good 100 miles.

Tours leave from Seward’s small boat harbor and head into Resurrection Bay. You’ll see fjords, wildlife, and tidewater glaciers (sheets of ice that extend to meet the sea).

The boats go by Caines Head—site of a World War II fort—and Callisto Head, before going around Aialik Cape into far calmer Aialik Bay. That’s where you’ll get to see—and maybe even hear—the Holgate and Aialik Glaciers.

For those who prefer to provide the power for their boat, consider a kayaking trip—either a guided day trip or, for experienced paddlers, a multi-day trip. Don’t overestimate your paddling experience—these are not calm waters, and the weather and wind change quickly, making for very challenging paddling.

Less demanding is to hire a water taxi to drop you off at a beach or cove. Some of the best camping coves include Bear Cove, the Coleman Bay Area (near the Aialik Bay Ranger Station), and McMullen Cove.

Favorites of both Alaskans and visitors, the state’s network of public-use cabins offers good (bear-safe) base camps. But don’t head out to a Kenai Fjords cabin without a reservation (907-644-3661) or camping gear—the bunks are wood and require sleeping pads and sleeping bags. And there’s no electricity or running water.

The Aialik cabin, which sits at the head of Aialik Bay, is accessible by boat or floatplane from Seward. (Note: The cabin is on land leased from the Port Graham Native Corporation, so if you want to hike beyond the 5-acre site, you’ll need to get a permit: 907-284-2212. A hike to Abra Cove, well outside the 5-acre area, makes that arrangement well worth the time.)

Check in with park rangers to find out about tide times and how many hours you should allow for a given activity. Spend your days kayaking, hiking, or tidepooling—or, thanks to the long summer days, some of each. During blueberry season, bring containers along and stock up—just watch out for the berry-loving big bears (and maybe even their cubs).

Also accessible from Seward by boat or floatplane is the Holgate cabin. Sitting on a bluff above a beach, the cabin offers stellar views of the Holgate glacier. (Keep that in mind if a giant cracking noise wakes you up in the night, it’s just the glacier shedding some of its ice.) Also part of the scenario: lots of mosquitoes. Be sure to pack bug repellent and a head net.

There’s one established campground. Backcountry camping is allowed through most of the park, including along the Harding Icefield Trail and in coves and beaches throughout the fjords.

Information

|

How to Get There Take the Seward Highway (AK-1, which turns to AK-9) south from Anchorage. Leave extra time to make the 126-mile trip on the National Scenic Byway, brimming with photo ops. (Watch for surfers taking on the bore tide.) During summer, RV traffic can slow the drive down. There is daily bus and Alaska Railroad service between Anchorage and Seward during the summer months. Charter flights are also available from Anchorage and Homer. Camping The park’s established campground (12 sites) is first come, first served. The park also offers two summer-use cabins (see here). There’s also a winter-only cabin: Willow Cabin at Exit Glacier. For cabin reservations, 907-644-3661. Lodging In the park there’s concessioner-operated Kenai Fjords Glacier Lodge (kenaifjordsglacierlodge.com). Seward (seward.com; 907-224-8051) offers lodging options. |

When to Go Though open year-round, most visitors explore the park during the summer months, when boat trips are offered. Flight-seeing companies run trips year-round out of Seward (subject to cancellation because of harsh weather). The road to Exit Glacier usually opens in late spring; it closes to car traffic with the first snowfall. Once there’s enough snow coverage, the 7-mile road opens to those who want to trek, dog-sled, or cross-country ski. Hikers and bicyclists are allowed on the road year-round. Visitor Centers The Kenai Fjords National Park Information Center at Seward’s small harbor is open mid-May to mid-Sept. The Exit Glacier Nature Center is at the Exit Glacier trailhead. Headquarters 500 Adams St., #103 |

A paddler in a folding canoe takes in a Kobuk River view.

Alaska

Established December 2, 1980

1,795,280 acres

In the heart of the Arctic, Kobuk Valley National Park is one of the least visited parks in the system, seeing maybe 5,000 travelers a year. There are neither roads nor entrance gates here. Nearly all is wild. What people miss by passing it by, though, are 100-foot-tall sand dunes, some of the oldest evidence of human settlement in North America, and the chance to experience a quarter-million caribou on the move.

Well above the Arctic Circle, Kobuk Valley is nowhere near the beaten track. Over the course of a busy year, the park will see fewer visitors than Yellowstone’s Old Faithful gets in a single hour on a rainy summer Sunday. Most years, Kobuk Valley is listed as the least visited National Park in the entire system; some years, not even a thousand people make their way here.

Seasonally populating the park is the largest caribou herd in the United States. The majestic animals pass through twice a year, heading north in the spring and south in the fall.

More than a hundred species of birds use the park as a flyway and nesting ground. The very remoteness of the park—the very fact so few people come here—is what makes Kobuk Valley one of the most vital areas protected by the National Park Service. Here, it’s never been anything but business as usual for nature.

Kobuk Valley is a transition zone, with Gates of the Arctic National Park to the east, the Bering Sea to the west, Noatak National Preserve to the north, and the Selawik National Wildlife Refuge to the south. Within Kobuk Valley, the great birch and spruce forests of central Alaska give way to the tundra of the Arctic.

In general, the farther north you go, the shorter the trees are, having a hard time surviving the cold soil to send roots down past the permafrost. A very tall tree in the Arctic is five or six feet high, and those are usually along riverbanks, where the water helps growth and adds to the visual landscape.

The park does not have the high peaks of the central Brooks Range. The highest mountain in the park is Mount Angayukaqsraq, just 4,760 feet high. Still, the mountains are many and imposing, with the Baird Mountains (a subrange of the Brooks) practically cutting the park in half.

► HOW TO VISIT

This is one of the most remote areas of the United States, a place where those familiar with Arctic travel fare best. Some adventurers float in, paddling the Kobuk River (often frozen) or the even more remote Salmon River (only for the extremely hardy; you must carry a pack raft up to the headwaters to access the river).

Use the banks as base camps for hiking and the rivers themselves as roads. Plan well, dress for changing weather, and expect a bear around nearly every corner. Welcome to Alaska’s Garden of Eden.

River Travel

Most visitors see the park from the vantage of its rivers. The Salmon River, designated a Wild River, drops through the park north to south before meeting the Kobuk River. Though only about 2 percent of visitors float the Salmon, it is the best place from which to see the landscape change from tundra in the northern reaches to forest in the south. Up at the headwaters, the river is fast, squeezing through a narrow valley, but for the final third of the way, it’s slow and shallow, with the water forming enchanting turquoise pools.

The Kobuk River cuts across the southern quarter of the park, stretching more than 200 miles in all, 61 of which are inside the park. It’s a slow river, barely a current in most places, and clear (unlike so many northern rivers, it’s fed by glacier). The river is very popular with salmon, which swim upstream more than 100 miles from the coast to spawn here.

Private operators run canoe trips on the Kobuk River, with camping on beaches filigreed with moose and wolf tracks. Most trips are a week long. The trip route runs between Ambler and Kiana.

Onion Portage, in the shadow of the Jade Mountains, on the eastern side of the park, is a handy shortcut point for people paddling the Kobuk River. It cuts about 10 very twisting river miles from a journey. The site, though, is notable for its location.

From here, when the time is right, it’s easy to watch the approaching caribou come down through the white spruce and birch forest on their migration. What’s more, this is an archaeological site with some of the oldest human remains in North America.

Onion Portage features eight distinct layers of stratification—a rarity in the Arctic, where permafrost churns up everything. This piece of land dates back some 10,000 years ago, when there was no such thing as North America (the land was joined to Asia at the Bering Land Bridge;).

The people in the Kobuk Valley at the time of the Woodland Culture of Onion Portage were the ones who came across the Bering Land Bridge and found everything they needed here.

The Onion Portage site, studied by pioneering archaeologist J. Louis Giddings, was a prime hunting grounds for native peoples during times of migration. Tools found at the site attest to the evolution of hunting techniques. At the time of the earliest settlement, this area would have hosted mammoths, scimitar cats, and beavers the size of coffee tables.

The portage remains an important crossing point for such animals as moose, caribou, and black bear. A highlight of any Arctic trip is watching a massive heard of caribou swim a crossing: they’re so well-adapted to the water it’s as if they’re moving along on a conveyor belt, their heads barely moving.

The archaeological site has been allowed to go wild again, so there’s not much to see, except one of the prettiest crossroads in the Arctic.

One of the most unusual features of the park is Great Kobuk Sand Dunes, grainy glacial silt covering an area of about 200,000 acres. Most of this terrain is hidden under plant life now, but three “active” dunes remain (about one-tenth of the dune area in all).

These are classically shaped sand dunes, carved into crescents by the constant wind and standing more than 100 feet high. The dunes are accessible via a hike south from the Kobuk River, near where the Hunt River comes in. There are no trails and no markers, so finding one’s way in from the Kobuk River is a considerable challenge. The hike involves slogging through boggy tundra at least some of the way to the dunes.

Seen from the air, the dunes look like the product of someone having dropped a chunk of the Sahara down into a bog. Taking advantage of the habitat, birds fill the wetlands surrounding the dune area.

Information

|

How to Get There The only way in is by plane. Alaska Airlines (alaskaair.com) flies from Anchorage to the park’s city of Kotzebue. The national park website has a list of pilots who have a permit to fly into the park. Visitors who bring collapsible boats can float from Ambler to Kiana. When to Go The park is open year-round, but only very experienced wilderness adventurers should consider visiting outside summer months. Any time of year, expect sudden weather shifts. Snowmobile access is permitted in winter. Visitor Centers The park’s visitor center (907-422-3890), open year-round, is the Northwest Heritage Center, in Kotzebue. |

Headquarters P.O. Box 1029 Camping There are no developed campgrounds. With a few exceptions, you can camp anywhere in the park. No permit is needed, but for the sake of safety you should register your itinerary with park officials. Observe all bear precautions, and take enough extra food to allow for being weathered-in for a few days—not uncommon. Lodging The nearest lodging is in Kotzebue (cityofkotzebue.com). |

Telaquana Lake

Alaska

Established December 2, 1980

4,030,006 acres

The land of the Dena’ina Athabascan people for 14,000 years is just as notable for the home that one man, Richard Proenneke, made here for 30 years. Lake Clark National Park and Preserve offers a diversity of experiences and landscapes that cause even state residents to swoon. Be prepared to revel in the reflections of volcanoes and remain ever ready for bear-viewing opportunities, all the while dreaming of ways to stay for a while.

Though it’s just 100 miles southwest of Anchorage, the roadless Lake Clark remains one of America’s least visited national parks. But it’s worth chartering a floatplane—the taxis of Alaska—to get there (even if just for a day trip). From wildlife viewing and fishing to cultural history and landscapes so majestic—dense forest, far-sweeping tundra, lakes tinted turquoise by glacial silt—it’s nearly impossible to capture their grandeur with a camera (though, of course, you should definitely give it a try), the park does justice to a wealth of grand outdoor options.

The park protects a giant swath of wilderness in south-central Alaska. The park is just north of Katmai National Park and across Cook Inlet from the Kenai Peninsula. Boats can enter the park via Cook Inlet, but most people arrive by floatplane. Visitors commonly arrange to be dropped off and picked up at the same spot or, in the case of river trips, a spot downstream.

The heart of the park, Lake Clark stretches some 40 miles. Three rivers (of many), the Mulchatna, Chilikadrotna, and Tlikakila, have Wild and/or Scenic designations. The mountains of Lake Clark dominate the views.

Lake Clark’s geography includes the tundra of the Turquoise-Telaquana Plateau, forested areas along the coastline, and the striking Chigmit Mountains, which rise along the park’s center, bridging the Aleutian Range to the south and, to the north, the Alaska Range.

The Chigmit Mountains are home to two active volcanoes, Mount Iliamna and Mount Redoubt. In 2009, Mount Redoubt provided proof that southern Alaska is one of the world’s most tectonically active places.

The park’s diversity of wildlife also astounds. There of 37 species of mammals. Massive brown bears come to feed on sedge in the salt marshes, dig razor clams, and feast on migrating salmon all along the Cook Inlet coastline. It is harder to spot the elusive lynx. Ground squirrels (a favorite food for grizzlies) are plentiful. Add to that 187 species of birds—and fish, plenty of fish.

► HOW TO VISIT

Lake Clark doesn’t have very much in the way of developed areas and park-operated services. There are no boardwalks or shuttle-bus services in the park. If you decide to venture into the park solo, keep in mind that this is Alaska—and that help is not always just a cell phone call away.

The park lacks an extensive trail system, which somehow adds to the wild aspect to the park’s fine opportunities for great-outdoors experiences: paddling, hiking, camping, and climbing. If you aren’t keen on off-trail navigation by yourself, you can take advantage of one of many guide services in the area.

Hiking is best around the lakes—and from lake to lake. Fishing is usually first class. If you have the time, sign up for a guided kayak adventure—or rent a kayak, raft, or canoe from an independent outfitter outside the park so to experience the park at water level.

The Richard Proenneke Cabin at Twin Lakes

After retiring, Richard Proenneke, a mechanic and amateur naturalist, decided to make Upper Twin Lake his home. He spent the summers of 1967 and 1968 building a log cabin by hand, an experience that he wrote about and filmed. This documentation was the basis of books and movies that showcase his craftsmanship and what it takes to live alone in a wild place—something Proenneke did for 30 years. At age 82, he left his cabin and its contents to the National Park Service, then headed to California, where he died at age 86. Now a National Historic Site, the cabin is open to visitors. Guided tours are given throughout much of the summer. During the tour, visitors can sit at his desk and even read his famed journals.

The cabin is accessible by floatplane to Upper Twin Lake. Day-trippers make up the largest portion of the cabin’s visitors, Backpackers consider it an excellent spot to begin—or end—a backcountry foray. Three of the best routes are Hope Creek, which goes from the cabin into the Hope Creek Valley, where you’ll trek over alpine terrain; the Low Pass Route, which skirts the lake before heading through meadows and along some challenging and steep scree slopes; and, for a good day hike, the 10-mile Upper to Lower Twin Lakes Route.

Hike along the south side of the lakes. If possible, bring fishing equipment and some cooking gear. There’s a good chance you’ll catch something for lunch, perhaps lake trout or arctic char.

Carry bug repellent and, better yet, wear a head net—mosquitoes are especially plentiful in June and July.

On the Water

Lake Clark is a standout on the fishing front, but not the only good site. Throughout the summer, the park’s lakes and rivers offer abundant salmon runs as well as rainbow trout, grayling, arctic char, and more. You’ll need a State of Alaska fishing license, which can be purchased at any large outfitter in Anchorage or Port Alsworth. Once you have a license, head to Crescent Lake, in the Chigmit Mountains, along with a guide with a boat. Because of dense brush, park visitors can’t access the lake from the land.

A guide is also helpful when it comes to salmon fishing. Running in the waters here are reds (second half of July) and silvers (mid-August to early September). Several guide companies run day trips to the lake; visitors also have the option of spending several days here by booking a trip to a local fishing lodge. Keep in mind that the fish are also very popular with brown bears.

Another spot favored by both fishermen and bears is Silver Salmon Creek. Silvers make their run here from August into September. The creek is also a top spot for birders—watch for seabirds on the cliffs and shorebirds, including the black oystercatcher, with its bright orange beak, dancing around on the mudflats.

The park is also a dream spot for kayaking, rafting, and “pack rafting” (an ideal sport for those who love to combine hiking with a float trip). The best lakes for kayaking include Telaquana, Turquoise, Twin, Lake Clark, Kontrashibuna, and Tazimina. You can rent a kayak in Port Alsworth.

For rafters, the park’s rivers offer take-your-breath-away scenery and, on the broad Tlikakila River, Class II and III rapids. Originating in Lake Clark Pass and fed by a series of glaciers, the brown, fast-moving river runs through the center of the park. In summer, king, coho, and sockeye salmon forge upstream here.

Information

|

How to Get There There are no roads to Lake Clark National Park. Book a flight from Port Alsworth, Anchorage, or Kenai, or charter a floatplane. It’s also possible to get to the park’s eastern boundary by crossing Cook Inlet from the Kenai Peninsula by boat. When to Go Open year-round, the park’s peak season runs June through mid-Sept. June and July are the warmest months, with temperatures between 50°F and 70°F. That’s mosquito time too. Wildflowers are best in late June. Aug. and Sept. are the wettest months. Autumn colors peak at higher elevations in early and mid-Sept. After that, be prepared for anything from sunshine to snow. Visitor Centers Outside the park, the Port Alsworth Visitor Center (907-781-2117) is open June–early Sept. For general visitor information, contact the Homer Field Office (907-235-7903). |

Headquarters 1240 W. Fifth St. Field Headquarters Camping Lake Clark is basically a giant, mostly trail-free, camping site. There’s one primitive campground, on Upper Twin Lakes.Preparation is key when it comes to camping in Lake Clark National Park. The weather can change quickly, sometimes making it difficult for a floatplane pilot to retrieve you. It’s not unusual for a trip to run a few days longer than planned. It’s a good idea to pack extra food. Lodging There are several lodges on private lands within the park’s boundaries. For ideas check out: nps.gov/lacl/planyourvisit/eating-sleeping.htm. |

Wildflowers and Nizina Glacier

Alaska

Established December 2, 1980

13,188,000 acres

By far the largest national park—nearly four times the size of Yellowstone—Wrangell–St. Elias National Park could be the closest thing we’ll ever have to Shangri-La. It’s a landscape protected by mountains, where glaciers flow through streaks of earth, where nature’s work—the click of a mountain goat’s hoof, the sniff of a bear checking the wind—goes on with almost no one to hear or see it.

O ne of the park’s glaciers, the Malaspina, is larger than Rhode Island. The gigantic park contains four mountain ranges, with nine of the highest peaks in North America, including Mount St. Elias, at 18,009 feet. Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Glacier Bay National Park, Canada’s Kluane National Park, and the trans-border Tatshenshini-Alsek parks, make up a 24,300,000-acre UNESCO Heritage Reserve site.

► HOW TO VISIT

The best way to see the park depends on time, experience, and budget. The easy way in is on the McCarthy Road or the Nabesna Road. Both go a little ways into the park. To see the deeper country, you’ll need a horse, a guide, or a pilot. Flight-seeing here is one of the great Alaska experiences.

Skookum Volcano Trail, Wrangell–St. Elias National Park

McCarthy & Nabesna Roads

Most people enter the park via the McCarthy Road, which comes into the park at Chitina. A few trails split off from the road, including the Nugget Creek Trail, which leads 15 miles to the foot of Mount Blackburn. A more challenging trail is the 14-mile Dixie Pass, with a steep climb to panoramic views.

The McCarthy Road ends at the Kennicott River; just across is McCarthy, which looks like a set from a backwoods-Alaska movie, with buildings in every state of repair, antler decor, dogs that seem to own the streets, and people who have chosen to live a long way from “civilization” and are willing to fight to keep things that way.

The old Kennecott Mine is 5 miles deeper into the park. Hike, or rent a bike in McCarthy. The Kennecott Mines were once one of the richest digs in the world. In just over 30 years of operation, nearly 600,000 tons of copper and close to a million ounces of silver were brought out. What’s truly amazing is the sheer size of the operation: The main building is 14 stories high. Until they got their railway working, every single bit of equipment either had to be made on site, floated downriver, or brought in by horses. The mine is a National Historic Site.

A 2-mile trail leads from McCarthy to beautiful views of the Kennicott Glacier—feeder of the Kennicott River—and the Root Glacier. For a more challenging hike, keep going past the Root to the 9-mile Erie Lake/Stairway Icefall trail. This hike takes you back to the Stairway Icefall and may be the only chance you’ll ever have to see a 7,000-foot vertical wall of ice shining its glacier blues.

The other main route into the park is the Nabesna Road, which goes back 42 miles into the Wrangell Mountains. Check road conditions before heading out; this is not a place to get stuck. The biggest draw here is simply going where few others go. On view is the spine of Alaska, along the divide between two rivers, the Copper and Nabesna, which ends at the Bering Sea, on the far end of Alaska.

Glaciers get all the publicity in Wrangell–St. Elias, but glaciers turn into rivers, and this corner of Alaska has some of the state’s best. In the park, rafting companies work the Nabesna, Kennicott, Chitina, and Nizina rivers, as well as the granddaddy of them all, the Copper (see sidebar at left). These rivers are truly wild—cold and full of glacial silt that can weigh down a person’s clothes so fast there’s no swimming out. Park offices can help by providing a list of river guides.

Getting still deeper into the park requires an airplane. Flight-seeing the park is like looking into a hole in time. From high above it isn’t hard to get a sense of what the landscape looked like during the last Ice Age, the jagged, scraped-bare peaks of the high mountains thrusting through thousands of feet of ice.

To get closer to the mountains, charter a flight out of McCarthy and try the Bremmer Basecamp hike, which leads from a gravel landing strip deep in the park through four or five days of relatively easy-to-walk countryside (Once there were mines tucked away in this part of the park, and traces remain.)

For something more ambitious, fly to the Goat Trail, a strenuous route with scree scrambles and cold river crossings. A true wilderness experience, plan on a week to get in and back. Here, as elsewhere in the park, obey all bear-safety precautions.

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve is so big that one could travel it over a lifetime and still see only a corner. That’s okay. Even the tiniest corner is a wonder of the American park system.

Information

|

How to Get There Wrangell–St. Elias has two road access points: the main one, the McCarthy Road, is outside Copper Center. The road is rough but passable. Rougher still though passable in a passenger vehicle, Nabesna Road, the other road access point, can be picked up at the Slana Ranger Station, 75 miles northeast of Copper Center. When to Go The park is open year-round; outside summer months, though, it’s a destination only experienced winter campers should try. Be prepared for abrupt temperature changes any time of year. Lodging The park’s only full-service lodgings, including several concessioner-run B&Bs and the Kennicott Glacier Lodge (kennicottlodge.com; 800-582-5128), are in McCarthy. Around the edges of the park, the towns of Glennallen and Copper Center offer motels. Visit nps.gov/wrst/planyourvisit/lodging.htm for information. |

Headquarters P.O. Box 439 Camping You can camp almost anywhere in the park except around McCarthy. No permit needed, but it is wise to register your itinerary with park officials. The park’s 14 very basic cabins, scattered around the park, are hike- or fly-in. Visitor Centers The main visitor center and park headquarters is in Copper Center, about 200 scenic miles from Anchorage and 250 less scenic miles from Fairbanks. The visitor center (907-822-7250) is open April through Oct. A second visitor center (907-554-1105), in McCarthy, is open Memorial Day to Labor Day. Both visitor centers are intermittently staffed. |