Keping Yu’s phrase “Democracy is a good thing” is already well known at home and abroad, though not everyone who reflects on China’s future would necessarily agree.1 In today’s China, Jiang Qing is somebody who is not afraid to stand alone and refuse to follow the herd. Jiang Qing may not have actually used those words, but he would surely agree that the politics of Way of the Humane Authority is a good thing.

Over the past twenty years or so, Jiang has devoted himself to establishing the structure and theory of political Confucianism.2 He started with a study of the Gongyang school,3 and has now moved on to say that “the Way of the Humane Authority is the direction in which contemporary Chinese politics is heading.”4 Most recently he has been promoting Confucian constitutionalism with the Way of the Humane Authority at its center.5 His untiring efforts and dedication to this one cause are said to be so as to resolve the question of legitimacy. He sees the fundamental problem of political power as one of legitimacy, or of “legitimizing the Way.” He believes that this question has not been properly handled either in China or in the West, which some people take as the model. Furthermore, it could even lead to a serious crisis. The Way of the Humane Authority is his prescription for resolving this problem of legitimacy.

China’s problem is said to be its lack of legitimacy. The reason for this, according to Jiang, is that over the past hundred years “China’s own culture has collapsed and its leading role in the formation of culture has been completely taken over by foreign culture—liberal or socialist cultures. This has displaced Confucian culture from its orthodox status as a guide in politics and society and led to a falling away from the path of development of Chinese culture.”6

In the West the problem is that legitimacy is unbalanced. Jiang thinks that “the politics in the West is colored by its cultural one-sided tendency. Thus, when dealing with the issue of legitimacy, the West has often gone from one extreme to another. While it exclusively focused on the divine source of legitimacy throughout the Middle Ages, now the excessive weight is given to the will of the people as the sole guarantor of legitimacy in the modern time.” Due to its bias toward the will of the people, Western democracy has become “excessively secularized, vulgarized, flatten, and full of human desires.”7

Jiang thinks that it is possible to resolve the problem of legitimacy both for China and the West and the solution is his idea of the Way of the Humane Authority. Of course, the Way of the Humane Authority is not the ideal Confucian solution since it would not be required once we have entered into the world of great harmony.8 But in the imperfect world of today, the Way of the Humane Authority is the best possible choice. It should be accepted both in China and the West as the direction in which politics develops.9

The key term in the Way of the Humane Authority is “royal.” Confucian classics explain the term according to either sound or form. The Discussions in the White Tiger Hall (Baihu tongde lun) explains “royal” (wang) as “coming towards (wang), that towards which all under heaven come.” Confucius notes that the character wang ( ) is composed of three horizontal lines united by one vertical line. Dong Zhongshu explains further, “[T]he three horizontal lines represent heaven, earth and the human realms and the one vertical line which unites them stands for the Way.”10

) is composed of three horizontal lines united by one vertical line. Dong Zhongshu explains further, “[T]he three horizontal lines represent heaven, earth and the human realms and the one vertical line which unites them stands for the Way.”10

On the basis of the Confucian classics, Jiang argues that legitimacy must be threefold. The popular legitimacy is the easiest to understand since Jiang defines it as based on the will of the people. The legitimacy of earth is that the political order of each state should be in conformity with its own culture. In China that means conforming to Confucian culture and the Confucian way. It is much more difficult to understand the legitimacy of the way of heaven. Feng Youlan noted that the term “heaven” had five meanings in ancient China: a material heaven, a ruling heaven, a fatalistic heaven, a naturalistic heaven, an ethical heaven.11 In writing Political Confucianism (Zhengzhi Ruxue), Jiang would appear to agree with Feng, but he draws attention only to the latter four meanings. Whether we read five or four meanings is not important though; in both cases the term “heaven” is unclear and can give rise to misunderstanding. It is perhaps to avoid such misinterpretations that in his most recent writings Jiang speaks of sacred legitimacy as “morality” or “applied morality.”12

In his Political Confucianism, published in 2003, Jiang put the legitimacy of the human way in first place, calling it “the first principle of the Way of the Humane Authority.”13 In his more recent writings he has moved the legitimacy of the way of heaven into first place. His reason is that heaven is “ ‘the first among the many things’ and ‘the great prince of the hundred spirits.’ It is the sovereign and so the three forms are not equal or on the same plane.”14

The Way of the Humane Authority at the level of legitimization must be realized at the level of the implementation. Otherwise, it will remain somewhat abstract. Jiang recommends a tricameral parliamentary system at this level; each of the houses represents one form of legitimacy.15

Jiang’s theory is such as to create a school apart. He throws out a challenge to all those who discuss Chinese politics to reflect over many theoretical and practical issues as well as historical and contemporary issues. Given that Jiang’s study of political Confucianism and his advocacy of the Way of the Humane Authority and Confucian constitutionalism are not on academic grounds alone, but to provide a remedy for enduring political ills and “a theoretic alternative for China’s future political reform,”16 and to resolve the political difficulties faced by all human societies, this critical essay focuses on his identification of those ills and the remedy he proposes with such single-minded dedication.

Jiang focuses on the issue of legitimacy because he believes that both China and the West are facing a crisis of legitimacy.

Putting to one side the question as to whether legitimacy is the root problem of politics, we first must note that any political setup will have to face the question of legitimacy because no political arrangement can win the minds and hearts of every single person. For instance, when the Republic of China replaced the monarchy in 1911 there were some Qing loyalists who doubted the legitimacy of the Republic. The People’s Republic of China was founded sixty years ago, but there are still those who think it is illegitimate. But that some people question the legitimacy of a political arrangement does not mean that there is a crisis of legitimacy. We need to ask what exactly Jiang understands as the crisis of legitimacy faced both by China and the West.

Legitimacy can be explained in two ways: At the level of norms, legitimacy involves asking if the origins of political power are rightful or justifiable.17 At the practical level, legitimacy is a matter of whether or not the political setup is able to make people believe that the current polity is the best feasible alternative for their country.18 It is clear that the latter is a political matter. When people in general hold that the present political arrangement is not best suited to their country, then legitimacy faces a crisis. Legitimacy at the level of norms is a matter of moral philosophy. If the questioning of legitimacy of moral philosophers, or politicians under the guise of moral philosophers, has no influence on the thought or behavior of the people who live in the country, then it is of purely academic interest and does not constitute a problem of legitimacy. To sum up, then, whether or not a political system faces a crisis of legitimacy depends on whether the people who live there doubt the rightness of its power, and whether they consider it the appropriate system for their country. In Confucian terminology, the key to determining whether or not there is a crisis of legitimacy lies in whether or not “all under heaven” “turn toward” the system. By this criterion, does China face a crisis of legitimacy?

Jiang thinks that Chinese politics have lacked legitimacy for a long time. It so happens that mainstream Western theorists say much the same thing. Having been said time and again over the last few decades it would seem to have become an unshakeable truth. Many articles, newspapers reports, and speeches by politicians in the West, Hong Kong, and Taiwan all take China’s supposed lack of legitimacy as the basis for their theories. In time some people in China have begun to share the same view.

If we first use normative legitimacy as our standard, Jiang is quite right to assert that China’s lack of legitimacy is a very serious problem because the Way of the Humane Authority and three forms of legitimacy are quite absent in the present time. The problem is that Jiang himself acknowledges that the Way of the Humane Authority is an ideal model developed from the rule of the three sage kings as known in legends. Since the time of the three dynasties this ideal has never been able to be put into practice. In other words, China’s problem of legitimacy in this sense has a long history, of at least over two thousand years. Likewise, if we use the Western standard of legitimacy at the normative level, then China certainly has a problem of legitimacy because, without competitive elections, China’s political system does not match Schumpeterian criteria for electoral democracy.19

However, if we consider things from whether or not all under heaven turns toward the authorities, then the situation is very different. Since the 1990s Western scholars (or scholars born in China and working in the West) have carried out many large-scale surveys into the legitimacy of Chinese political power. Initially the high degree of acceptance of the regime was interpreted by the Western scholars as a result of the persons questioned being afraid to tell the truth. As a result, later surveys added various mechanisms to prevent the people being questioned from telling lies (such as providing the options “don’t know” or “no response”). But the results of each survey were always the same.20 There was a time when articles with this conclusion had great difficulty in being published in Western academic journals because the anonymous assessors used their own subjective opinion to cruelly shoot down such results.21 However, iron-fast facts are hard to denounce. By now scholars familiar with the field have virtually all arrived at a consensus: the degree of legitimacy of the Chinese political system is very high.22

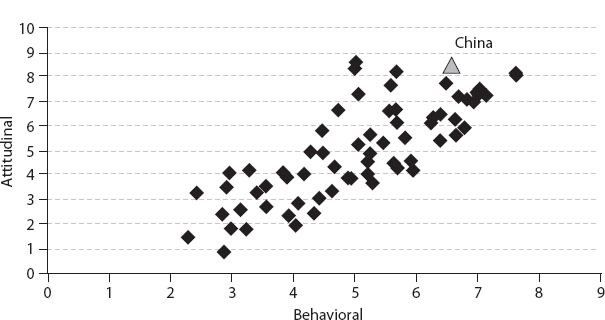

FIGURE 7.1. The Ranking of Legitimacy in Seventy-Two States

At the turn of the century, Bruce Gilley made a chart of legitimacy ratings in seventy-two countries (Figure 7.1). The total population of the countries is 5.1 billion, or 83 percent of the world population. Gilley’s chart has two axes: attitudinal and behavioral. The data for people’s attitude to their government come from the World Value Survey. The data on how much people’s behavior indicates support for their government are derived from three indicators: rate of participation in elections, frequency of violence in popular opposition to officials, and proportion of revenue from income tax, capital gains tax, and real estate tax in the total revenue of the central government. In terms of attitude, the chart shows clearly that China comes in second place at 8.5, a long way above the United States (7.12) and India (5.89). Gilley’s axis on behavior is not quite fair to China since China has only recently brought in income tax, and it is shared equally between the central and local governments. Also, China has no real estate tax yet. Moreover, these systems of taxation have nothing to do with whether the ordinary people support the government or not. Nonetheless, Gilley’s chart still places China in thirteenth place, well above many supposedly democratic countries.23

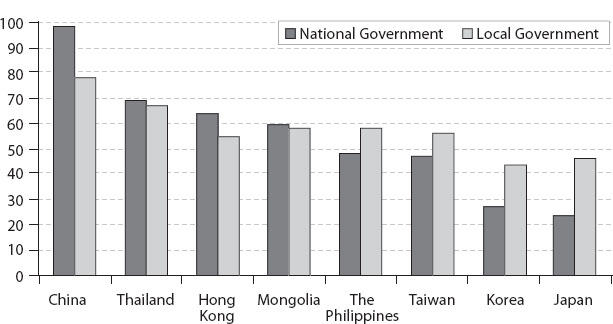

FIGURE 7.2. Trust in National and Local Governments

In 2008 Columbia University Press published a most interesting book: How East Asians View Democracy.24 This book looks at eight countries or regions in East Asia. The case studies in the book are all based on comprehensive, strictly random sample surveys. Among the questions, two are relevant to the legitimacy of the state: people’s level of trust in central and local government. Figure 7.2 is drawn up according to the data in the book and shows that of all the eight countries or regions studied, the Chinese state comes closest to the ideal of all under heaven turning toward it. From the above it would seem that China does not suffer from any lack of legitimacy.

Jiang’s criticism of Western liberal democracy is that its legitimacy relies solely on the people’s will. This criticism seems to imply that Jiang has accepted the mainstream Western view that Western liberal democracy does enjoy the legitimacy of the popular will. What he objects to is that this form of legitimacy is lopsided and unbalanced. But does Western liberal democracy really enjoy popular legitimacy?

Surveys in Europe and America often include the question, “Are you satisfied with the performance of democracy?” The surveys in such countries regularly report that over 70 percent of respondents are “satisfied” or “comparatively satisfied.”25 On the basis of this, many people conclude that American and European countries enjoy the legitimacy of the popular will. But the question itself is too vague. It could be understood as asking (1) if you satisfied with the present government, or (2) satisfied with the present political system, or (3) satisfied with democracy as an ideal form of political arrangement. It could also be understood as any possible combination of the above. In other words, it is a bit like a rubbish bin and is a pretty meaningless question and should not be taken too seriously.26

If instead we ask “What degree of confidence do you have in the government?” the situation is very different. Among ninety countries for which data are available, Vietnam and China come in at the top, with the people having great confidence in the government while most European and American countries are in the bottom half, with the United States at fifty-eight, the United Kingdom at sixty-eight, France at seventy-seven, and Germany at eighty-seven.27 If a large proportion of the citizens have no confidence in the government, how much popular legitimacy does such a political system have?

In Western liberal democracy, the so-called representatives of the people, the national assembly members or parliamentarians, are chosen by election. However, as Fareed Zakaria, the editor of Newsweek, so ironically pointed out that, in many polls, when Americans are asked which public institutions they most trust, there are always three in the lead: the Supreme Court, the army, and the Federal Reserve Bank.28 What all three have in common is that their directors are not chosen by election, and these organizations are not ones that supposedly represent the people. But it is precisely the elected institutions such as the U.S. Congress that most opinion polls show to be placed in the lower ranks. Zakaria said that in 2003. On April 18, 2010, the Pew Research Center published its latest survey, “The People and Their Government: Distrust, Discontent, Anger,” which again proved the same point. Only 24 percent of those polled indicated support for what the U.S. Congress did, and a massive 65 percent indicated disagreement. The reputation of the Congress is only slightly better when compared to the badly discredited banks and financial institutions at the height of the financial crisis.29

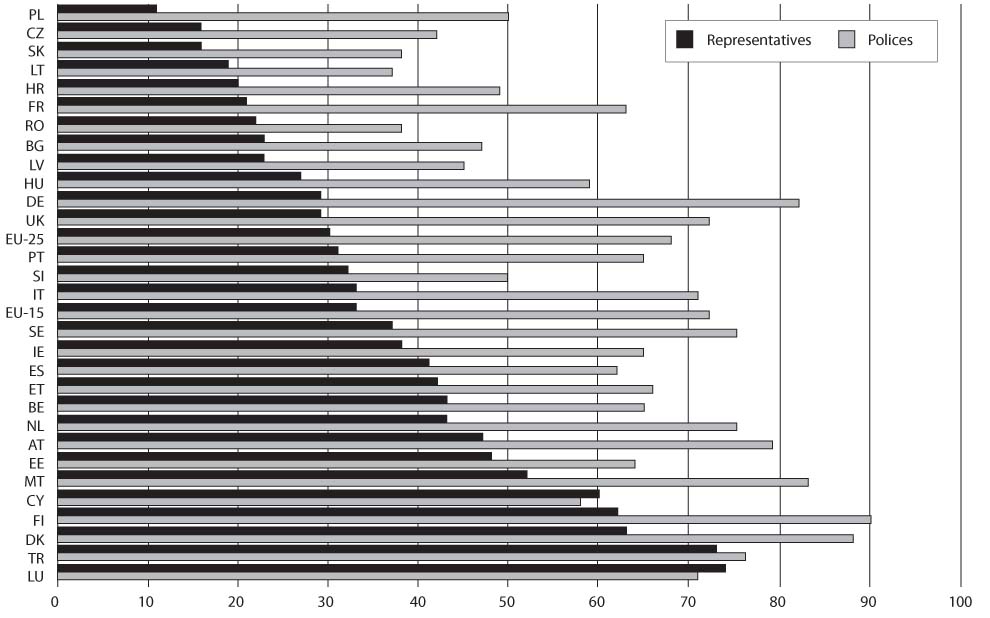

Not only do institutions that are supposed to represent the people have very little popular legitimacy in the United States, even in Europe the situation is much the same. The results of the 2005 European Social Survey (ESS) are shown in Figure 7.3.30 Apart from two tiny countries— Luxembourg with a population of 0.5 million and Cyprus with a population of 1 million—people have more confidence in the police, who are a symbol of violence, than in the members of parliaments who are the supposed representatives of the people. The average rate of trust in the people’s representatives of the twenty-nine countries taken together is 37 percent. While this is better than that in the United States, it is still very low. The gap between trust in the police and in the people’s representatives is 25.9 percent, while in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany it is between 40 percent and 50 percent.

If the people’s representatives chosen by election are held by most people as not representative of the will of the people and do not enjoy the trust of the majority, then Western liberal democracy based on competitive elections would appear to not have much popular legitimacy; still less can it be said that popular legitimacy is monopolized as the only form of legitimacy.

FIGURE 7.3. Trust in Representatives and Polices, 2005

Source: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/areas/qualityoflife/eurlife/checkform.php?idDomain=0&Submit1=List.

Note: AT = Austria; BE = Belgium; BG = Bulgaria; CY = Cyprus; CZ = Czech Republic; DE = Germany; DK = Denmark; EE = Estonia; EL = Greece; ES = Spain; EU-15 = 15 EU member states (before May 2004); EU-25 = 25 EU member states (after May 2004); FI = Finland; FR = France; HR = Croatia; HU = Hungary; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; LT = Lithuania; LU = Luxembourg; LV = Latvia; MT = Malta; NL = Netherlands; PL = Poland; PT = Portugal; RO = Romania; SE = Sweden; SI = Slovenia; SK = Slovakia; TR = Turkey; UK = United Kingdom.

While Jiang thinks that Western liberal democracy is too democratic, I think that its problem is that it is not democratic enough. In recent years the term “democracy” has been preceded by such adjectives as “liberal,” “constitutional,” “representative,” “electoral,” “pluralist.” The aim of all those modifications is to restrict democracy. “Liberal” democracy and “constitutional” democracy bar many important things that involve people’s everyday life (e.g., property ownership, work, family life) from democratic decision making. “Representative” democracy makes democracy a ritual of power endorsement that happens only every few years, between which people hardly play any role in decision making. “Electoral” democracy in practice deprives most people of the right to be elected such that elections result in what Aristotle referred to as oligarchy,31 or Francesco Guicciardini (1483– 1540) called aristocracy.32 “Pluralist” democracy papers over the serious inequalities in the distribution of economic, social, and political resources among social classes and the effects of this. In each case the addition of the adjective leads to a defective form of democracy, a powerless democracy, a democracy less dangerous to the ruling class, a democracy that represents the interests of powerful social groups rather than the will of the people.33

Clearly, it is a misjudgment to say that China lacks legitimacy or that the legitimacy of the Western democracy relies solely on the will of the people.

When you see the doctor, he needs to make a correct diagnosis in order to provide the right prescription. If the diagnosis is mistaken, then it is hard to prevent the prescribed medicine from having little effect. What is at stake here is a matter both of reasoning and of practicability.

In terms of reasoning, if China’s problem is not a lack of legitimacy and the West does not suffer from the supremacy of popular will, do we need the Way of the Humane Authority as the option for improving China’s politics in the future? Could it also serve as the political ideal for the whole world?

An ideal is worth pursuing only if it is possible to realize it in practice. This is what Rawls calls a practical utopia. If the ideal is altogether unrealizable, then it is merely a pipe dream. We have already mentioned that the Way of the Humane Authority vaunted by the ancient Confucian worthies is an ideal model based on the governance of the sage kings of the three dynasties. The term “three dynasties” was coined in the Eastern Zhou era to refer to an ancient golden age. Archaeological evidence cannot yet confirm the existence of the Xia dynasty. Up to now, it is purely the stuff of legends.34 Jiang himself admits that after the three dynasties this ideal was no longer practiced. However good it was as an ideal, if it has not been put into practice for over several thousand years, one has good reason to wonder if it is not a mere pipe dream. There is even more reason to wonder if something that could not be achieved when society was under hierarchical leadership could possibly be implemented in China today after a socialist revolution and the acceptance of the idea of equality.

Even through Jiang’s reinterpretation, his idea of the Way of the Humane Authority or Confucian constitutionalism based on threefold legitimacy is not necessarily a practical utopia worth pursuing. In a nutshell, Jiang’s Confucian constitutionalism is an elitist blueprint, not an ordinary kind of elitism but a Confucian elitism or an elitism in which Confucian scholars are the elite.35 Propagation of this kind of elitism is based on two presuppositions: (1) the political structures of both China and the West are insufficiently elitist and (2) only elitism by Confucian scholars is able to understand the way of legitimizing politics and also comprehend its implementation, representing the way both of heaven and of earth. The vast mass of the people cannot understand either legitimization or implementation, nor can they represent heaven or earth.

But neither of these presuppositions can stand.

Let us consider the first of them. Under Mao Zedong there was probably not much elitism in China because from the late fifties onward, he began to search for a way to wipe out “bourgeois rights,” that is to change the unequal relationships between people. This search was called “combat and prevent revisionism.”36 In 1957 Mao noted that though the socialist transformation of the means of production had been largely complete, the transformation of human mind-sets was not yet complete.37 The next year, in his criticism of Stalin’s The Economic Problem of Soviet Socialism, Mao went on to say,

Following the changes wrought by the socialist transformation, we have basically resolved all the problems with regards to the ownership of the means of production. However, equal relationship between people in the process of production would not emerge automatically. The existence of bourgeois rights will certainly prevent in all ways it can the formation and development of this equality. It is essential to do away with bourgeois rights which still exist between people. Such bourgeois rights manifest themselves in the pyramid of power, condescending attitudes, withdrawing from the masses, not treating people as equals, not relying on work or physical strength to eat but relying on one’s post or power, division between cadres and the masses, hierarchical relations like those of cat and mouse or father and son. These must all be destroyed, utterly destroyed. Once destroyed, they will return so they must be destroyed again.38

At the time the methods Mao used to destroy bourgeois rights involved rectification, encouragement of grassroots experimentations, criticism of hierarchy, sending cadres to work in the countryside, and “two participations and one reform” (the participation of cadres in manual work and the participation of workers in management, and the reform of unreasonable regulations). Later on, the Socialist Education Movement (1963–66) in both town and countryside was also designed to solve this problem. But he still felt that these measures were insufficient to destroy bourgeois rights and prevent the danger of a restoration of capitalism.

On the eve of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), Mao published the ideal of his later days in the May 7th Directive. From this we can see that Mao wanted to gradually abolish division of labor in society and abolish commodities and that he was looking for a completely equal society in which the three great inequalities of workers and peasants, town and country, physical labor and mental labor would be destroyed. He wanted complete equality in work, culture, education, politics, and material conditions of life.39

The first part of the Cultural Revolution (1966–68) focused on criticism of so-called “capitalist roaders,” while the later part of the Revolution (1969–76) shifted to nurture so-called “socialist new things” (e.g., May 7th cadre schools; educated youth going up to mountains and down to the countryside; revolutionary model operas; workers, peasants, and soldiers going to university and running universities; workers’ propaganda team; poor peasants’ propaganda team; barefoot doctors; cooperative medicine; three-way union of the elderly, middle aged, and youth; and three-way union of workers, cadres, and intellectuals). All these things can be seen as Mao’s ways of realizing his ideal.

However, after eight years of the Cultural Revolution, Mao realized that one revolution alone could not achieve his goals. In a speech on theory in 1974, he revealed his true feeling:

China is a socialist country. It resembled capitalism in many ways before Liberation (1949). Even now we still have eight grades of pay, distribution of resources according to work, currency exchanges, all of which are not very different from the old society. The main difference is that the ownership of the means of production has changed. China is now implementing a commodity system, the wage system is unequal, there are eight grade wage scales, and so on.40

This became the basis for his theory of continuous revolution. Between October 1975 and January 1976, before he died, Mao spoke many times of the problem of bourgeois rights. His conclusion was that in a hundred years a revolution would still be needed and again in a thousand years.41

In brief, throughout his last years Mao was fully engaged in combating against bourgeois rights and using all means to bring about equality of all (excluding class enemies) in the economy, in society, in politics and culture. Consequently, China did not develop serious class divisions. The pre-Liberation old elite and the post-Liberation new elite all were held down.

The policy of reform and opening up began in opposition to the ideology of leveling everyone to the lowest common denominator. In the thirty years since then, the lives of hundreds of millions of ordinary workers and peasants have been improved, but their political status has plummeted substantially. Meanwhile, with the support of the political elite, the capitalist class and intellectuals, who were at the bottom of politics in Mao’s era, have returned to the upper echelons of society. They have also used the resources and knowledge they have in hand to throw themselves into politics. By now the political elite, economic elite, and intellectual elite have formed a kind of triangular alliance, which is tending to harden.42

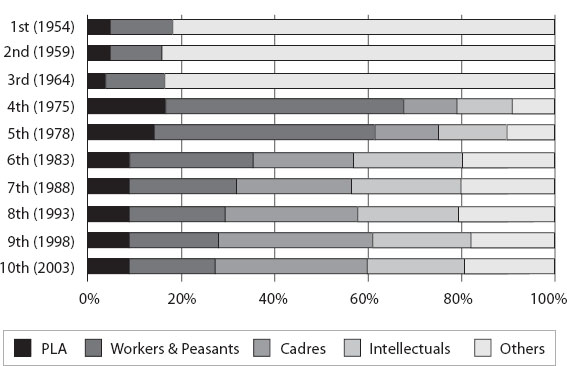

Changes in the political standing of each class are reflected in the composition of the National People’s Congress (see Figure 7.4). In the period when Mao sought to eradicate bourgeois rights in the later part of the Cultural Revolution, workers, soldiers, and peasants were the mainstay of the Congress, with over two-thirds of the seats, of which workers and peasants accounted for more than one-half. This proportion fell after the Cultural Revolution from 51.1 percent in the Fourth Congress in 1975 to 18.46 percent in the Tenth Congress in 2003. In the Eleventh Congress convened in 2008, it was said that “numbers of frontline workers and peasants have greatly increased,” but the exact figure is unknown. We do know, however, that currently the mainstay of the Congress is cadres of all levels and intellectuals, who together compose two-thirds of the total.43 Meanwhile the National Political Consultative Conference is a veritable elite club, whose 2,237 members represent thirty-four fields of work. While this body also contains representatives from the All-China Federation of Trade Unions and the agricultural field, who are mostly union officials or agronomists, there are practically no ordinary workers or peasants.44

Western liberal (capitalist) democracy was elitist from the start. When, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the theory of majority rule was beginning to be widely accepted, Gaetano Mosca advanced the theory of the ruling class, while Vilfredo Pareto advocated an elitist theory.45 They thought that universal suffrage would give rise to the illusion that the people had become the ruling class but in fact society would still be run by elite, and these elite would be composed almost entirely of members of the bourgeoisie.46 Whatever motive they had for advancing elitism, the development of European and American states in the last century or so has proved their prediction to be correct.

FIGURE 7.4. The Composition of the National People’s Congress

Source: http://www.people.com.cn/GB/14576/15117/2350775.html and http://www.people.com.cn/GB/shizheng/1026/2369476.html.

In a liberal democracy, the main form of participation by the mass of people is in elections. The degree to which people with varying social resources participate in elections shows a huge discrepancy. Data gathered in various countries throughout the years confirm that the more resources one has, the more one is likely to vote, and the less resources one has, the less one will go to the polls. In other words, social elites have a higher turnout than people lower down the social ladder.47

Not only are social elites more ready to vote, they also make up by far the largest proportion of persons elected. Research into the background of political elites in European and American countries was relatively large in number in the 1950s and 1960s, because at the time the influence of Marxist analysis was more marked. After the sixties this type of studies gradually disappeared, and by now they are exceedingly rare. But the presence of social elites in state apparatus is beyond any doubt. In the U.S. Congress, the House of Representatives has 435 members, of whom at least 123 are millionaires, which amounts to one-third. In the Senate, among its 100 members, at least 50 are millionaires, which is one-half of the total.48 In fact, it is not quite true to say that they are just millionaires because some of them are billionaires. For instance, one candidate in the 2004 presidential election, John Kerry, had a household wealth of US$340 million. Perhaps some people will say that the high proportion of millionaires in the U.S. Congress indicates that there are more millionaires in the United States. In truth, there are quite a lot of millionaires in the United States, but their total number certainly does not exceed 1 percent of the population. Clearly, they have a large stake on the American political scene. A researcher of the U.S. Congress, Thomas Mann, sums it up well: the members of the U.S. Congress are certainly not chosen from among the ranks of the ordinary people. They are an elite band through and through.49

Besides actively taking part in elections and influencing the choice of policy makers or themselves taking public office, the social elite will unsparingly lobby to influence the process of decision making. Mainstream Western pluralism would seem to have won most people to believe that anyone can form their own group to present their own demands. According this theory, the existence of innumerable groups means not only that they can keep an effective check on government but also that they can keep a check on each other and ensure that no one group becomes dominant, and so together they make up the pluralist playing board. But the actual situation is very different. The power of groups that represent the particular interests of elite circles is vastly superior to that of groups that represent ordinary people.50

Unequal participation in politics results in serious inequality in political influence: the influence of elites on the government far surpasses that of the masses. In the heat of the 2008 American presidential election, Professor Larry M. Bartels of Princeton University published a book with the title Unequal Democracy.51 It was reported at the time that Obama read the book.52 This book analyzed the response of the Senate’s responsiveness to the demands of groups with different incomes in the period of the 101st to 103rd Congresses. He found that the response of the Senate to groups with high income was the strongest, to those in the middle income bracket it was less, while to those with the lowest income it was the weakest, to the point of even being negative and contrary to their interests. This rate of responsiveness was roughly the same throughout the whole period of the three Congresses. There are those who will say that the United States has two main parties and that if one party neglects the poor and favors the rich, the other will bring things back into balance. Facts prove that this way of thinking is illusory. Is there a difference between the Republicans and the Democrats? Yes. The Republicans tend to favor the rich more, but the Democrats are also unfair to the poor. Both parties react negatively to the poor. Clearly there is a difference between the parties, but it is negligible since both are dedicated to representing the interests of the elite.53

Western liberal (capitalist) democracy is excessively elitist. This is perhaps why its popular legitimacy is not high at all.

If the political systems of China and the West already have a highly elitist tendency, one might well ask, is Jiang’s championing of elitism an asset in establishing a balanced political system, or will it lead to the very lack of balance he so fears?

Let us turn to Jiang’s second hypothesis now. Could the elite or great Confucian scholars represent what he calls “transcendent, sacred legitimacy”? The answer of course depends on the meaning of the “transcendent, sacred legitimacy.” If it means “practical morality,” is such “practical morality” a universal value? Yet Jiang would seem not to recognize any universal morality or global ethics, so it can only be a native Chinese ethics.54 The problem is that if we use Jiang’s argument in denial of a global ethics, people could also argue in the same way that Confucian ethics is merely one strand of China’s native ethics and that it should not monopolize the entire field of ethics, especially in China today, or else it will commit the same error as the Western-centered theory in proposing a Confucian-centered theory. If Confucianism cannot monopolize ethics in China, then to form a House of Ru to represent transcendent, sacred legitimacy would seem to be lacking in legitimacy itself.

Even if it is not from a fear of equating Confucian ethics with Chinese ethics, people will still question whether great Confucian scholars can represent this transcendental legitimacy on the basis of the history of Confucianism in China. Jiang himself separates political Confucianism, moral Confucianism (New Confucianism), and politicized Confucianism. In his view, New Confucianism that fails to develop a new theory of political authority presents nothing more than an “eye-catching but meaningless scene” with many serious negative consequences.55 He is even more critical of politicized Confucianism, saying that

it has completely given up any ultimate concern for an ideal of higher values or hope for future harmony in society. It has lost its ability to criticize the present system and engage in self-criticism. It has integrated itself wholly to the existing political order and has become transformed into a pure ideology, descending to the level of a political tool to defend the interests of the present system and the rulers.56

In the history of Confucianism, Han Confucians turned Confucianism into a theology lost in the smoke of corruption and ghost stories. In the Wei-Jin period, the scholar-officials pursued abstruse studies and made Confucianism into abstruse metaphysics. Under the Sui the system of state examinations was established. In the following thirteen centuries, Confucianism essentially became a stepping stone for one generation after another of clueless scholars to pursue a career in officialdom. Popular sayings in Chinese—“A mouth full of virtue and morality; a stomach full of burglary and concubinage,” “hypocritical Confucian scholars”—are the result of observations that the words and deeds of Confucians did not match. Were the corrupt officials in Chinese history not also Confucians who had applied themselves wholeheartedly to reading the books of sages and worthies? A book like the Anecdotal History of the Scholars lets us see how many Confucians were lazy loiterers, yes-men, in search of petty gains.57 In fact even great Confucians were not necessarily better. The colorful tittle-tattle about the great Zhu Xi’s private life in unofficial historic records is not entirely unfounded.58

During the Japanese invasion of China, a great master of Confucianism, Wang Jitang (1877–1948), became one of three most notorious traitors serving the puppet North China Political Council (1940–43). A leading academician thoroughly acquainted with the classics, he cooperated with the Japanese in north China in the Strengthening Security Movement, which led to the slaughter and harassment of Chinese people opposed to Japanese rule. He also opened an Academy of Confucianism and ran training in Confucian studies for youngsters, using these as a means of turning the people into slaves. He was executed for treason in 1948. The former director of the Chinese Philosophy Research Centre of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Zheng Jiadong, was famed for his study of Confucius and could probably be counted as a great Confucian of the present time, but in 2005 he was arrested for smuggling six women into the United States.59 Some would argue that Zheng’s crime had nothing to do with Confucianism. Perhaps, but the problem is how people can distinguish genuine Confucians from insincere Confucians.

If Jiang’s criticism of moral Confucianism and politicized Confucianism is correct, if Confucianism has gone off the rails for a very long time, if many contemporary Confucians are hypocrites, then what reason do we have for believing that simply be reading the Four Books and Five Classics Confucians will be able to represent transcendent, sacred legitimacy? Will we have to sort our Confucians into true and false ones, as previously we had to distinguish true and false Marxists? Who is qualified to make this kind of assessment?

If undifferentiated Confucians are incapable of representing sacred legitimacy, can they represent historical, cultural legitimacy along with other elite persons? To answer this question, it is necessary to spell out the meaning of “historical culture.” “Culture” is very difficult to define. Back in 1952 two researchers gathered 164 different definitions of culture.60 Jiang’s “historical-cultural” must refer to the historical-cultural tradition, that is, the total sum of the system of social values that are transmitted over time. If this is indeed his understanding, then this tradition must include the great tradition of what is recorded in the classics and transmitted by the social elite, and the little tradition formed by the daily life and oral tradition of the masses.61 Here we do not need to worry about whether the great tradition determines the little one or vice versa. Yet we must acknowledge that both are alive and both change and evolve with the times. They are mutually interrelated. But Jiang would seem to tend to essentialize historical-cultural tradition, as if it were some “heavenly book” written a long time ago by the sages, whose code can be read only by Confucians and the cultural elite. If the historical-cultural tradition is a living synthesis of the great and little traditions, then ordinary people ought to have a say in interpreting it. It should not become the exclusive preserve of Confucians and the cultural elite.

In the above, I have addressed the desirability of what Jiang calls the Way of the Humane Authority; let us now turn to the practical aspects and ask if it is feasible.

Jiang states very clearly that if the Way of the Humane Authority or Confucian constitutionalism is to be realized in China, “at least three conditions must be met . . . : Firstly, there must be a complete revival in society of a Confucian-centered Chinese culture. Secondly, within the country there should be the spontaneous formation of a substantial body of scholars in China who keep to Confucian beliefs and practices. Thirdly, the way of Yao, Shun, Confucius, and Mencius must be added to the constitution.” He also optimistically concludes, “It is not impossible that one day they should all be realized.” Here it might be better to speak in terms of probability rather than possibility. Of course, no one can completely rule out the possibility that the three conditions will be met, but it would appear that the chances of Confucianism returning to its status as China’s orthodoxy and becoming the Palace School again are fairly low. Daniel A. Bell observes that in China there is “hardly anybody really believes that Marxism should provide guidelines for thinking about China’s political future.”62 If Bell is right, then the chances of Confucianism being the guiding principle of the country are even slimmer.

I have used the Baidu Index (http://index.baidu.com) to gather support for my view and show that it is not just my own personal opinion. The Baidu Index is a statistical tool for measuring the volumes of keyword searches, based on Baidu’s web search statistics. It can show how much interest people have in certain keywords.63 Figure 7.5a looks at to what extent Internet users are interested in three key terms: Confucian thought, liberalism, and Mao Zedong thought. It informs us that since 2006 Internet users are much more interested in Confucian thought than in liberalism. However, they are more interested in Mao Zedong thought than in Confucianism. This is reflected in the three curves that respectively indicate the number of searches on each keyword; the three lines are not in the same order of magnitude. Figure 7.5b is based on the names of three persons: Confucius, Hu Shi, and Mao Zedong. Clearly, there is no great difference between 7.5a and 7.5b. Hu Shi, the standard bearer of Chinese liberalism, is always in last place (if the name Li Shenzhi, another representative of Chinese liberalism, were used in place of that of Hu Shi, the line on the graph would be invisible). The venerable founder of Confucianism, Confucius is in second place, and Mao Zedong is in first place. Only at the beginning of 2010 did the search volume of “Confucius” abruptly soar; this was because a movie titled Confucius was released at that time and not because there was any fundamental change in direction. If Google Trends (http://www.google.cn/trends?hl=en), another tool for displaying search trends, were used to carry out the same kind of search, the results would be more or less the same. This shows that Confucianism has indeed enjoyed a restoration, but this does not mean that it will become the sole form of ideology. Hence, implementing the Way of the Humane Authority or Confucian constitutionalism is not a “realistic utopia,” at least not yet.

Jiang advocates elitism in politics, rule by sages, because he remains fundamentally opposed to equality for all. He thinks that “in practical morality the difference between people is very great. There are distinctions between sages and commoners, between gentlemen and small-minded person. Moreover these moral distinctions have significance in politics and government.”64 This implies that he has wholly accepted that “[o]nly the superior savants and inferior fools cannot be changed” (Analects 17.3), “[w]hile the people may be made to obey they cannot be made to understand” (Analects 8.9), and “[t]hose who work by their minds govern others; those who work by their strength are governed by others” (Mencius 3A:6). Probably no reasoning will be able to shake him from his obstinate belief in this matter.

Other supporters of Confucian politics have not necessarily gone as far as Jiang in their views. As an advocate of elite rule, Bai Tongdong, for instance, does not deny the equal capacity of sages and commoners to participate in politics. What he stresses is that most ordinary people (including most “petty bourgeoisie” or “middle class” such as white-collar workers, technicians, engineers, doctors, financial workers, teachers, and the like) simply lack the time, energy, interest, or ability to participate in running the state.65 But if ordinary people do not have the chance to exercise their capacity to participate in politics, then there is no need to press for elitism. It is far more important to create the conditions under which the mass of people can in fact take part in politics.

FIGURE 7.5. Popular Interest in Certain Keywords

In my view, “Chinese socialist democracy” would be a much better alternative than the Way of the Humane Authority, as it would lay institutional foundations for everyone to become equal to Yaos and Shuns (even Mencius admits, “All men may be Yaos and Shuns” [Mencius 6B:2]).66 For want of space, I cannot elaborate my ideas here. I simply want to emphasize what I mean by the three terms of this expression. For me, “socialism” refers to what China has painstakingly developed over the last sixty years through a history of taking a step sometimes to the left, sometimes to the right.67 It is a form of socialism that has been sought by global progressive forces over the past century or so.68 “Democracy” is not merely what I call electocracy. Rather, it should be a new form of democracy that tries to enable everyone to take part in politics through sortition, deliberation, and modern electronic forms of communication and that extends popular participation from the political realm to other areas, including that of the economy.69 More inclusive than Confucianism, “Chinese” refers to the Chinese civilization (not just the Han civilization) that is culturally rooted in a tradition of “unity in diversity” and never-ending self-revitalization. The goal of “Chinese socialist democracy” is to eventually achieve the great harmony instead of merely a moderately prosperous society. In fact, according to Jiang’s own theory, the Way of the Humane Authority is not suitable for a harmonious world.

If we were to borrow Jiang’s terminology, then “socialism” would be the way of heaven (sacred legitimacy), “democracy” the way of humanity (popular legitimacy), “Chinese” the way of earth (cultural and historical legitimacy). Would this model of threefold legitimacy not be a “more realistic utopia” than his model of the Way of the Humane Authority?