Improving Your Conversations

This chapter will prepare you for the key relationship-building conversations you need in order to escape the feature factory: the Trust Conversation, the Fear Conversation, the Why Conversation, the Commitment Conversation, and the Accountability Conversation. Before you tackle the specific conversations, however, it is important to learn how to analyze and build your conversational skills generally. You will learn about why conversations are humanity’s unique superpower and how to harness this power effectively through study and practice.

This chapter will also describe the core challenge to improving our conversations, which is that our behavior doesn’t match our beliefs, and we are unaware of the gap. To combat this problem, we will provide a process to help you become aware: the Four Rs. We will show you how to Record your conversations, how to Reflect on them to find problems, how to Revise them to produce better alternatives, and how to Role Play to gain fluency. Finally, we will provide some sample conversations that will allow you to see the process in action.

Once you have the foundation of the Four Rs, you’ll be ready for Part II of the book, where you will learn how to have each of the specific conversations.

Conversations: Humanity’s Secret Weapon

Our Special Power

In his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari explores what has allowed humans to become the dominant species on the planet. His answer is that we have a special kind of communication, unique among animals.1

Many animals can communicate the idea “Run away from the lion!” through barks, chirps, or movement. Building on top of that, the development of human and animal communication seems to have been driven by the need to share information about others of the same species—the need to gossip. Gossiping allowed us, as social animals, to understand each other and have established reputations; and this, in turn, allowed us to collaborate in larger groups and to develop more sophisticated collaboration. In fact, understanding other humans, developing a “theory of mind,” is so important that philosopher Daniel Dennett, in From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds, makes the case that our own consciousness arose as a byproduct of understanding the minds of others.2

Though our ability to gossip surpasses that of other species, Harari says that what is really unique about human language is our ability to discuss nonexistent things.3 With this special power, we are able to create and believe shared fictions. These fictions allow us to collaborate at tremendous scales and across groups of people who have never met. In this way, a community’s belief in a crocodile-headed god can create flood control works on the Nile, as described by Harari in another of his books, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow.4 And a shared belief in continuous improvement can allow us to create a learning environment and a performance-oriented culture rather than a power-oriented or rule-oriented culture, as described in Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations by Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim.5

Why Our Power Is Flawed

Conversation makes collaboration possible but not inevitable. We don’t live in a world of universal acceptance, peace, and understanding. Earnest and well-intentioned people can disagree, and even come to view another person as an enemy, as “the other.” Along with our amazing powers of conversation, we also come equipped with pre-existing, built-in flaws—our so-called cognitive biases (see Table 2.1 for a sampling of our favorite biases, and Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, for many more). These are biases that seem to be built into the functioning of our brains. And these cognitive biases inhibit the sort of collaboration our language makes possible.

Name |

Distortion |

Egocentric bias |

Give self undue credit for positive outcomes |

False consensus effect |

Believe that personal views are commonly held |

Gambler’s fallacy |

Believe that a random event is influenced by previous outcomes |

Illusion of control |

Overestimate control over external events |

Loss aversion |

Value keeping a possession over gaining something of greater value |

Naïve realism |

Believe personal view of reality is accurate and without bias |

Negativity bias |

Recall unpleasant events more readily than positive ones |

Normalcy bias |

Refuse to plan for a novel catastrophe |

Outcome bias |

Judge decisions by their results instead of by the quality of the decision-making process |

Table 2.1: A Sampling of Cognitive Biases

Our cognitive biases pose a threat to any adoption of Agile, Lean, or DevOps methods because they can seriously damage collaboration, relationships, and team productivity.

In the previous sections, we described how transparency and curiosity are woven into the fabric of people-centric practices, but these are undermined by a host of cognitive biases. An example is the false-consensus effect, where we believe our own views to be commonly held. This bias makes us less likely to either share our reasoning or to ask about the reasoning of others. What’s the point when we believe we already agree? Naïve realism, the belief that we see reality as it is, without bias, is yet more corrosive to team dynamics in that we see any disagreement as a sign that the other party is uninformed, irrational, lazy, biased, or perhaps all of those! Under the influence of these and other cognitive biases, Agile, Lean, and DevOps practices can fail to deliver the promised benefits.

Learning from Conversations

Conversations as an Investigative Tool

Social scientist Chris Argyris studied organizational behavior, particularly in businesses, in a long and illustrious academic career at the business schools of Yale and Harvard. His areas of research included individual and organizational learning, and effective interventions that “promote learning at the level of norms and values.”6 The humble conversation was the central tool Argyris used for investigating group effectiveness and for improving organizational performance. What Argyris found was that conversations, together with the unexpressed thoughts of the participants in those conversations, revealed everything he needed to know about the “theories of action” of the people and organizations he studied.

Argyris and collaborator Donald Schön use the term “theory of action” to describe the logic—the “master program”—behind our actions.7 According to Argyris and Schön, we all have outcomes we want to achieve, and we use our theory of action to choose which steps to take. If my theory of action has a focus on learning, then I will take actions that generate information, like sharing everything I know that is relevant to the situation and asking others about what they know. If my theory of action is centered on getting my own way, then I will only share information that supports my position, and I won’t ask questions to which I don’t know the answer.

In general we don’t explicitly think about our theories of action; however, as with the two examples we just provided, we can understand them after the fact by examining our choice of action. One of the findings of Argyris and Schön is that there is often a gap between what we say we would do in a situation (espoused theory) and what we actually do (theory-in-use).8

Defensive versus Productive Reasoning:

What We Do and What We Say We Do

Before reading on, consider this question: If you had an important choice to make as a group, how would you recommend the group go about making the decision?

When we ask this question of our audiences, we get remarkably consistent answers. The typical response is something like, “I’d have everyone share all the information they have, explain their ideas and reasoning, and then see if we can agree on the best way to proceed.”

If your answer sounded like this, congratulations! You have espoused what Argyris and his colleagues call the Model II Theory of Action,9 or “productive reasoning.”10 You claim to value transparency, sharing your reasoning and information. You also claim to value curiosity, hearing everyone’s thoughts to learn their reasoning and what information they have that you don’t. Finally, you claim to value collaboration and jointly designing how to proceed. While you might have used different words, these are commonly understood and accepted practices to increase learning and make better decisions. In fact, you likely do behave this way in nonthreatening situations, where nothing important is at stake. Unfortunately, if you are like the more than 10,000 people that Argyris studied across all ages and cultures11 (and those we’ve met!), your behavior won’t match your words when the topic is something important—like introducing a company strategy or leading a cultural transformation.

Argyris and colleagues found that although almost everyone claims to adopt the approaches and behaviors of productive reasoning, things change when the situation is potentially threatening or embarrassing. In those cases, what people actually do closely matches a very different theory-in-use that Argyris terms the Model I Theory of Action, or “defensive reasoning.”12

We contrast these two theories of action in Table 2.2. When using a defensive reasoning mind-set, people act to remove the threat or potential embarrassment. To do so, they tend to act unilaterally and without sharing their reasoning, they think in terms of winning and losing, they avoid expressing negative feelings, and they attempt to be seen as acting rationally.

Model I |

Model II |

|

Governing Values |

Define and achieve the goal Win; do not lose Suppress negative feelings Be rational |

Valid information Free and informed choice Internal commitment |

Strategies |

Act unilaterally Own the task Protect self Unilaterally protect others |

Share control Design tasks jointly Test theories publicly |

Useful When ... |

Data is easily observed Situation is well understood |

Data is conflicting or hidden Situation is complex |

Based on Argyris, Putnam, and McLain Smith13

Table 2.2: Model I and Model II Theories of Action Compared

This gap between our espoused theory and our theory-in-use gets at the heart of a paradox of team productivity. In theory, we value diverse teams because we understand that diversity can be a strength. A diversity of experiences, a diversity of knowledge, and even a diversity of modes of thought—in theory, these all make a team stronger, because every new element gives the team more information and more ideas, and therefore, more options to make better choices.

What we should be seeking from our diversity is productive conflict, through which we harness our differences to create new ideas and better options. In practice, we tend to see differences of opinion as threatening and potentially embarrassing, so we react defensively. Our defensive reasoning leads us to suppress the diversity we claimed to value and to avoid the productive exchange of ideas that we claimed to seek!

What does this defensive reasoning look like in practice? We will illustrate many flavors of defensive reasoning with examples throughout the book, but to paraphrase Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, each productive conversation is alike, and each defensive conversation is defensive in its own way. That said, there are common elements; and defensive reasoning in conversations will tend to feature hidden motives, undiscussable issues, and reacting to, rather than relating to, what is said—all characteristics that inhibit learning and corrode relationships.

Transforming Conversations

So, why do people choose these counterproductive, defensive behaviors rather than the behaviors we all agree would produce better results? The answer is that we don’t consciously choose. In everyday activities, this gap between the theories we espouse and the theories we use is invisible to us. We effortlessly produce the defensive behavior through years of practice—so effortlessly, in fact, that we aren’t aware of what we are doing, no matter how counterproductive it is for us or how much it contradicts our espoused theory of productive reasoning. Even worse, we are so unaware of our defensive reasoning that we will deny we are acting defensively if someone else tries to bring it to our attention.

The good news is that Argyris found that reflecting on conversations allowed participants to become aware of and then change their behavior.14 Through regular effort and practice, you can learn the behaviors of transparency and curiosity that will promote joint design and learning; the sharing of knowledge across organizational boundaries; and the sharing of and resolution of difficult, previously taboo issues. The bad news is that this takes substantial effort, and worse, this effort involves difficult emotional work.

The difficulty comes because it requires recognizing that your behaviors are contributing to the problem. Are you willing to consider that you might be contributing to unproductive meetings and defensive relationships? This is not a price everyone is willing to pay. Finally, even if you are willing to be humble and put in the effort, developing these new skills takes time. Argyris and colleagues describe overcoming our routine behaviors as taking about as much practice “as to play a not-so-decent game of tennis.”15 If this seems daunting, it may help to remember that you get the opportunity to practice every day as you work to solve real problems in your organization. We can give you the skills to practice if you have the drive to improve.

Later in this chapter, we will show you how to practice productive reasoning by learning from the conversations you are having today. In addition to providing the core technique for learning from conversations (the Four Rs), we will provide examples for you to practice your analysis. Through the remainder of the book, you’ll be using this same Four Rs approach again and again to learn the specifics of the Trust, Fear, Why, Commitment, and Accountability Conversations. These five conversations address the common pitfalls that prevent us from using the productive reasoning we espouse. These pitfalls are:

1.We won’t be transparent and curious when we lack Trust.

2.We will, consciously or not, act defensively when we have unspoken Fear.

3.We will be unable to generate productive conflict when we lack a shared Why.

4.We will avoid definite Commitments as long as the situation feels threatening or embarrassing.

5.We will fail to learn from our experiences if we are unwilling to be Accountable.

It is only after we have overcome each of these challenges that we can really have the productive learning conversations required for a high-performing organization.

Sidebar: Types of Conversations

From cover to cover, this book is about conversations, so it is worth taking a moment to explain the range of conversation types where this material is applicable.

The first image that comes to mind when we say “conversation” is probably a face-to-face encounter with two or more people in the same room. However, most of us have a number of other types of communication channels we use regularly. Email is ubiquitous. Chat systems such as Slack, Microsoft Teams, and IRC (internet relay chat) are being adopted right and left. Distributed meetings with video are increasingly common, a big step up from the voice-only conference call.

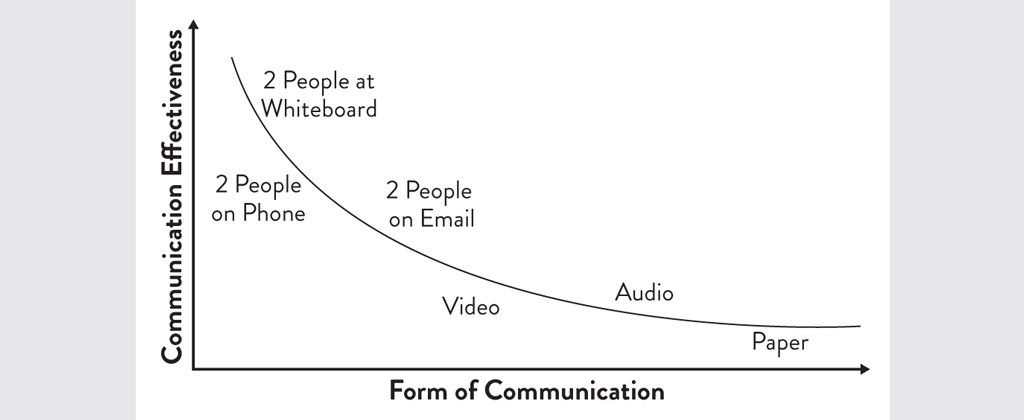

We believe the material in this book is useful across all these conversation modes, though it is worth considering the trade-offs inherent in the different options. Figure 2.1 provides a useful visual reference for these trade-offs based on a model by Alistair Cockburn.16

Figure 2.1: Effectiveness of Different Modes of Communication

As Cockburn says, “the most effective communication is person-to-person, face-to-face, as with two people at the whiteboard.”17 This scenario is the most effective, because, among other attributes, it offers the maximum possible nonverbal information to the two participants, and the fastest response rate. However, these same attributes can make it more difficult when you are learning to have difficult conversations and one or both parties are feeling strong emotions. A red face is additional information, but it can also be intimidating and distracting.

As an opportunity for learning, asynchronous channels can offer some benefits. One is that you’ll likely have a better record of what each party actually said, which can be a big help in performing a later conversational analysis.* Even better, an asynchronous channel allows us to make multiple drafts before responding. As an example, we’ve applied the Four Rs to draft emails, allowing us to use a technique we are learning and to incorporate the insights into the email we finally sent.

Ultimately the skill you are after is the ability to apply these techniques face to face and in real time; making good use of the learning opportunities of asynchronous communication can help you gain that ability.

The Four Rs

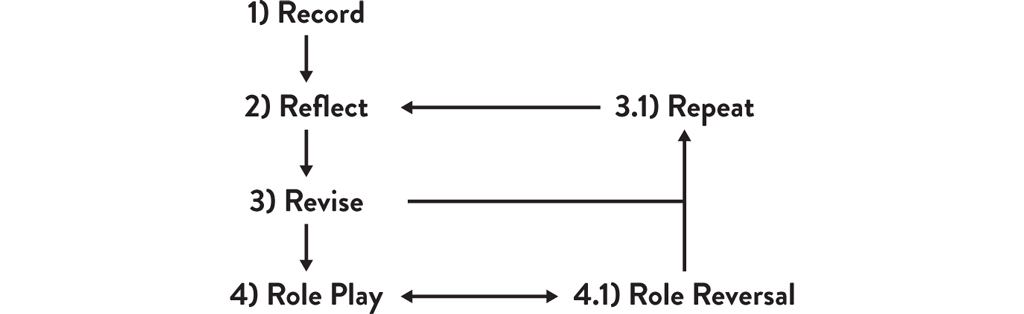

Experiences give us the opportunity to learn, but most people don’t take the time to actually learn from them. We apply the Four Rs—Record, Reflect, Revise, and Role Play—as our preferred way of learning from conversations. (As you can see in Figure 2.2, there are two additional Rs that can sneak in along the way: Repeat and Role Reversal.)

Figure 2.2: The Four Rs

To start using the Four Rs, you will need to Record a conversation in writing. In the next section, we describe our preferred method for this, the Two-Column Conversational Analysis. It may be tempting to avoid pen and paper and just think about the conversation “in your mind’s eye,” or talk about it with a friend. Do not do this! The act of writing down the words on paper is an inherent part of the process because it forces your brain to think about the conversation at arm’s length, as if it were happening to someone else. This distance is vital to gaining insights through reflection and revision, as we’ll see later.**

After you have Recorded the conversation, it’s time to Reflect on it, paying attention to the tool or technique you are trying to use at the time. For each of the Five Conversations, we will suggest particular tools. With time and practice, you will move between them as the conversation requires, but to start with, we recommend you use one tool or technique at a time. We will give you guidelines on how to score your conversation using the tool, and that reflection will lead you to possible improvements.

Having scored the conversation, Revise your conversation to try and produce a better result. How will you know if you’ve improved? Repeat: take your revised dialogue and Reflect again. Did you improve your score from the first time around? You may be surprised to find that your revised version in fact shows no better scores than your original! Don’t be discouraged—this is very common, especially as you are learning a new skill. It might take you half a dozen or more attempts to produce a revision that checks all the boxes of the technique.

Having created the dialogue for an alternative conversation, there’s still an important step remaining: Role Play. Find a friend who is willing to help, and try saying your dialogue aloud, with your friend taking the part of your conversation partner. How does it feel to say the words out loud? Often what seems okay in writing feels unnatural coming out of your mouth. Perhaps the words need to change, or perhaps you just need practice talking in a different way.

Another good check on your progress is the other hidden R: Role Reversal. Trade places in your dialogue and have your friend say your words. How does it feel to be in the other person’s shoes and to hear your revised language? Frequently, hearing your own words will give you clues as to how you can further tune the dialogue to feel more natural while keeping in place the skills you are trying to practice.

Following all of the Four Rs for a single conversation will offer the most learning from that single experience. Following them for a series of conversations will dramatically increase the volume and pace of your learning overall, and should quickly give you and your team substantial practical gains.

Conversational Analysis

The first step of the Four Rs is, as we just explained, is to Record the conversations you want to improve. We’re about to show you a remarkable technique invented and used by Chris Argyris for capturing the key elements of a conversation. We particularly like this method for two reasons: first, it is clearly specified and mechanical, which appeals to our engineering brains; and second, it very naturally lends itself to the other three Rs: Reflect, Revise, and Role Play.

At first, conversational analysis may seem too simple to be valuable. But it is the fastest route to gaining significant insights and improved conversations. We use it throughout the book to illustrate how to make each of the Five Conversations successful.

You Will Need

1.A single sheet of ordinary writing paper (Don’t get more than a single sheet, for a reason we’ll explain shortly.).

2.A pen, pencil, or other writing implement.

That’s it, really. (We told you it was simple!) Again, don’t let yourself skip the task of writing by saying you’ll imagine or remember the content—write it down on a real piece of paper. You’ll be glad you did when your distance helps you with a crucial insight.

Step 1: Record Your Conversation

Think of a conversation you would like to improve. This can be one you had recently, but it doesn’t have to be: you can analyze a conversation that occurred long ago or (this is a favorite of ours) one that hasn’t happened yet that you’re worried about.

Next, fold the paper down the middle the long way, creating two columns. In the right-hand column, write down what each person in the conversation said. Don’t worry about getting every word right; you’re aiming for the sound and flavor of the conversation, not exact quotes. On the other hand, try hard not to editorialize or add anything to the words. You’re trying to record what a neutral listener or mechanical audio recorder would hear.

In the left-hand column, after you have written the dialogue, write what you thought at the time as the words were spoken. Don’t hold back here; often in a difficult conversation, your thoughts will be very different from what you said, so include everything that crossed your mind, no matter how irrelevant or unfair it may seem. Important warning: you must not write anything that the other person thought.***

Tip: Keep It Short

We find that newcomers to the conversational analysis method often write far more than they need to, trying to capture every word of what might be a lengthy conversation. This is almost certainly unnecessary. If you concentrate on the most emotionally charged part of the conversation for you, it is very likely that you will be able to fit that key section onto just one side of your piece of paper, which is exactly why we told you to prepare only one sheet.

Keeping the case very focused like this probably means that you’ll need to start in the middle of the conversation rather than at the beginning. Don’t worry about this; it’s safe to assume that the reader knows the context of the conversation and what the participants said earlier, since the chief reader is going to be you!

If you find it hard to keep your case this short, try making it even shorter, just half the page.**** The restriction to a very limited length will help you create a more valuable, analysis-friendly case.

An Example Two-Column Conversational Analysis

Let’s look at a real conversation between the authors using the two-column analysis technique. This example concisely illustrates all the key characteristics of a conversational analysis: it’s short, the thoughts and the actual words are both included, and there are rich opportunities for learning by looking at the differences between the two columns.

When you read someone else’s recorded conversation, read the columns in the order they are recorded: read the right column first so that you understand the spoken dialogue, then go back and read the columns together so that you understand the inner dialogue that is happening along with the outer one. If you just jump in and read left to right and top to bottom, as is natural in English, you will hear that Squirrel is concerned about Jeffrey’s absence before Jeffrey announces that he’ll be away. If you’re reading out loud, you might add a reminder of the distinction between thoughts and speech: “Jeffrey says, ‘I’ll be out of the country for our next scheduled online training.’” Squirrel thinks, Ouch! Jeffrey usually sets up the phone and software connection, and so on. We aren’t usually aware of the distinction between the inner and outer dialogue, which makes this format helpful but sometimes tricky to grasp at first. Be patient: analyses become much easier to follow after you’ve recorded your own conversations a few times.

Jeffrey and Squirrel’s Conversation

What Squirrel thought and felt |

What Jeffrey and Squirrel said |

Ouch! Jeffrey usually sets up the phone and software connection. What do we do now? |

Jeffrey: I’ll be out of the country for our next scheduled online training. |

Seems doomed. I think we’ll just have to give up. |

Squirrel: Okay, that means we can’t do it at your office, I guess. Should we cancel? |

Sure, but how will I get the technology to work? It always seems fiddly when Jeffrey does it. |

Jeffrey: Oh no, I’m sure I can dial in. Then you can stay at home and won’t have to come to the office. |

That’s a good point—I’ll save on the commute stress. |

Squirrel: Yes, I guess you can join on the phone, and that would mean less travel for me. But I’ve never done the software and phone setup. |

I’m far less confident than Jeffrey is about this. |

Jeffrey: Don’t worry. The organizer sent us a link to a very helpful tutorial. You won’t have any trouble. |

What will I do if I screw it up? Hundreds of attendees will be furious with me for delaying the session they’ve paid for. I suppose I’ll just have to give it a go. |

Squirrel: Well, I guess I can give it a try. |

If you read just the right-hand column, you see a relatively calm conversation, with Squirrel expressing only mild doubts. That is indeed what you would have observed if you’d been in the room with us. But the left-hand column reveals far more about Squirrel’s inner fears and worries, with words like “doomed” and “furious” illustrating his depth of feeling. These unexpressed and perhaps undiscussable thoughts and feelings are exactly what we are going to concentrate on when we analyze cases using the techniques we are about to show you.

Analyzing a Conversation:

Reflect, Revise, and Role Play

Once you have your conversation down on paper, it’s time to take it apart, understand how it works, and look for ways to improve it—the Reflect, Revise, and Role Play steps of the Four Rs. As you are critiquing your conversation, you’ll want to test yourself against standards. We suggest examining conversations for evidence of transparency and curiosity, as these are fundamental elements of collaboration. Also attempt to notice patterns of behavior that apply across conversations.

As we Reflect on the conversation, we will be marking up the dialogue to help guide our later revision (see Figure 2.3 on page 44). Consider changing to a red pen (or other color) to make your markings obvious.

Figure 2.3: Norbert’s Annotated Conversation

We’re going to start with a conversation analyzed by Norbert, a system administrator for a midsize organization. He and his boss, Quinn, are trying to decide which virtualization software will be the best to use in a new project.

Norbert and Quinn’s Actual Conversation

Reminder: read the right-hand column first, then go back and read right to left.

What Norbert thought and felt |

What Norbert and Quinn said |

Open source is obviously the way to go. |

Norbert: I think we should go with KVM here. It’s the most flexible and fits our needs best. |

Only if you count “waiting on hold for support” as an efficient use of my time. |

Quinn: It’s not our standard, though. Virt-App is working efficiently on all our existing projects. |

Why are you always pushing closed-source solutions? |

Norbert: Okay, but we wait for fixes from them all the time, and it’s awful. Wouldn’t you rather be in control, so we can address problems ourselves? |

Nonsense! They all know KVM already, at least the basics. |

Quinn: Yes, but think about the retraining costs. I don’t think I could get additional budget for everyone to learn a new tool. |

Not much training needed in fact—everyone’s already using it on their side projects. |

Norbert: Why don’t we ask the team? I’m sure they’d be willing to self-train. |

Weren’t you just saying you wanted us to have more autonomy?? What a hypocrite you are! |

Quinn: Unfortunately I can’t leave budget-critical decisions like this up to the team. |

Typical manager, not willing to take any risks. There’s no point arguing against a decision that you’ve already made. |

Norbert: Okay, but I think you’re missing a real opportunity here. |

“I wasn’t too pleased with this conversation,” Norbert said afterward. “Quinn shot down my preferred solution, and what’s worse, I felt I was manipulated into agreeing to use Virt-App, Quinn’s favorite.” We can see this negative view developing in the left-hand column of Norbert’s conversation record, which starts with sarcasm and ends with fatalism.

How could Norbert have changed this conversation to achieve a different result? Below, we describe how he analyzed the conversation to discover more effective options. These are basic analysis steps you can use with any conversation. As you learn more techniques throughout the book, we’ll suggest further ways to score and learn from conversations, where you are employing a particular technique.

Reflect on Curiosity: The Question Fraction

The first principle of productive reasoning we are looking for is curiosity; and to assess how curious we are being, we start with the Question Fraction. To find the Question Fraction for this conversation, Norbert first looked at his right-hand column and circled all the question marks, finding two. He wrote this down at the top of the right-hand column as the bottom half of a fraction:

Now the hard part: Norbert asked himself, “Were each of my questions genuine?” A genuine question has these characteristics:18

•You really want to know the answer.

•It’s reasonable to expect that the answer might surprise you.

•You are willing to change your views or behavior as a result of the answer you get.

By contrast, nongenuine questions are used to make a point rather than learn something new. They are often statements in disguise, or attempts to lead the other person to a conclusion. Lawyers are particularly good at leading questions, designed to force specific answers out of an unwilling witness: “Did you drive to Bob’s house at noon? The neighbors saw you pounding on the door and shouting angrily, isn’t that right? And when he answered the door, you pulled out your gun, didn’t you?”

Crucially, you can’t distinguish between genuine and nongenuine questions simply by listening to them. The same words may be genuine in one context and nongenuine in another. The key to the distinction is the thoughts, often unexpressed, of the person asking the question. For example, if I ask you, “Have you fixed that critical bug yet?” I may genuinely want to know the status of the fix, or I may be trying to pressure you to work on it, or I may be subtly complaining that you haven’t started on a feature that I view as of the highest importance. Only my left-hand column (my thoughts) will reveal my true motives.

Reflecting on the genuineness of his questions, Norbert said, “It’s hard to admit, but I can see from my left-hand column that neither of my questions were genuine. I asked the first one, about being in control, because I wanted to push Quinn to use open source. And when I suggested we ask the team, I was leading the witness—I knew they would favor KVM, and this was a way to get more evidence on my side.”

Since none of his questions were genuine, Norbert places a zero in the numerator of his fraction:

To reiterate, as you analyze your conversation, add up the number of questions you asked; this is your denominator. Then analyze how many of your questions were genuine; this is your numerator:

The Question Fraction helps you understand how much curiosity you are demonstrating in your conversation. You might believe you held the conversation with an open mind, but if you weren’t asking genuine questions, you weren’t demonstrating that curiosity. This will be valuable input as you move on to the Revise step.

Reflect on Transparency:

Unexpressed Thoughts and Feelings

Next, Norbert turned to his left-hand column. As is usual in difficult conversations, this column has many statements and questions that do not appear in the right-hand column; in other words, it contains unshared ideas that represent unexpressed thoughts and feelings.

Emotions are particularly difficult for people to share in conversations. Not only do we lack practice in doing so but talking about emotions also violates two of the standard principles of the defensive mind-set: avoid expression of negative feelings and be seen as acting rationally.

When reflecting on how we can productively share our emotions, it is worth considering Marshall Rosenberg’s guidelines for sharing feelings from his book Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life:19

•Distinguish feelings from thoughts. We often say “I feel” followed by a thought, as in “I feel like we made the wrong choice.” If we can substitute “I feel” with “I think,” then we aren’t expressing an emotion.

•Distinguish between what we feel and what we think we are. “I feel like a fraud” is sharing a thought about what we think we are, not an emotion.

•Distinguish between what we feel and how we think others react or behave toward us. This is perhaps the most difficult of these guidelines to apply, because when we say “I feel ignored” or “misunderstood” or something similar, we are actually making a statement about other people—that they are ignoring or misunderstanding us. We are not sharing an emotion.

•Build a vocabulary for feelings. Saying “I felt good when that happened” isn’t very specific, nor is “I felt bad when that happened.” English has dozens of words to describe specific emotional states. (See the handy “Feelings Inventory” from the Center for Nonviolent Communication.20) Spend the effort to find the one that most accurately expresses how you feel.

What makes these guidelines difficult is that these statements, though not expressions of emotion directly, all raise strong emotions in us. Because the emotions are strong and clear to us, we assume they are obvious to others as well. This cognitive bias, known as the “Illusion of Transparency,” is one of the barriers to genuine transparency. Why should we share something that is obvious? As we reflect on our conversations, it is important to remember that if we aren’t explicitly sharing our emotions, then we aren’t being transparent.

When we review our unshared thoughts, it is also worth remembering another tip from Rosenberg: distinguish evaluations from observations.21 It is in our nature to instantly and effortlessly assign an intent to the actions we see from other people, as when Norbert brands Quinn as a “hypocrite.” These evaluations arise so quickly, it is easy to mistake them for the truth. Similarly, we read emotions into other people and are inappropriately confident of our judgement (the Illusion of Transparency again). When we notice these attributions of intent, or emotions that haven’t been stated by the other person, they should be a trigger for curiosity—a trigger for us to inquire how the other person is actually thinking and feeling.

With all of this in mind, Norbert underlined each sentence in the left-hand column (his thoughts) that was not expressed, even partially, in the right-hand column.

“I gave myself the benefit of the doubt in the first two rows,” said Norbert. “I did indirectly express support for open source further along in the dialogue, and I did mention waiting when explaining my opposition to Virt-App, though I didn’t quite say how passionately I hated wasting my time on hold with them. My thoughts became increasingly negative and dismissive in the following rows, and I didn’t share any of those feelings, so I underlined everything else. Looking at everything I underlined, I can see I wasn’t very transparent with Quinn. I didn’t share all the facts that I had, and I didn’t share any of the emotions I was feeling at the time.”

Reflect on Patterns: Triggers, Tells, and Twitches

Now Norbert looked for his individual triggers, tells, and twitches in the dialogue. These are personal and, as such, will tend to become apparent when you’ve analyzed several of your conversations and notice repeating patterns of behavior.

•A trigger is a behavior, statement, or other event outside yourself that typically causes you to react strongly. For instance, a less-experienced developer might become depressed and withdraw from the conversation when he hears the term “junior engineer” applied to him, as this makes him feel less valuable to the team.

•A tell (like in poker) is a behavior you exhibit that signals you are not acting with transparency and curiosity. For example, a manager might begin to pace around the meeting room when he’s frustrated and believes his team isn’t accepting his direction.

•A twitch is your instinctive default response, regardless of the details of the situation. For instance, one person may have a bias to get to a decision quickly and adjust later, while another might have a bias toward delaying a decision until all the facts are in.

Learning your triggers, tells, and twitches can help you become more self-aware and give you more choices in how you respond in the moment. We have both benefited from this type of analysis ourselves. Squirrel discovered a trigger by noticing he felt anxious and defensive when a very tall person he was working with would stand over him; he adjusted by standing up when talking with tall colleagues. Jeffrey learned from analyzing his conversations that he would say “obviously” and raise his left hand just before describing something that wasn’t obvious; now, when Jeffrey catches himself doing this, he says, “It isn’t obvious,” and then explains what he’s thinking.

No twitch is wrong; however, no twitch is right in all situations either. When you notice yourself acting in line with your twitch, it can be a useful prompt to consider whether that twitch is a good fit for the scenario of the moment.

“I found one trigger and one tell in this dialogue,” said Norbert. “First, I reacted really strongly to Quinn’s refusal to consult the team, calling him a hypocrite in my left-hand column. I often do this when people flatly refuse what seems like a reasonable request, so it’s a trigger.

“Also, I used ‘okay’ twice, when I definitely wasn’t feeling okay at all. The second time I was blasting Quinn in my left-hand column while agreeing with him in my right-hand column. I want to watch out for this tell in the future by noticing when I say ‘okay’ but don’t feel that way.”

When you identify a trigger, tell, or twitch in your conversation, circle the location and label it. Labeling it in the dialogue will help guide you through the Revise step, and it will also help you to recall it later, both in conversations and in future analysis.

Revise: Creating a Better Alternative

Finally it was time for Norbert to rewrite the dialogue in a way that addressed the issues he’d identified, using his annotated conversation record as a guide.

“I wanted to be more curious and to use more genuine questions,” said Norbert. “And I also thought I should be more transparent by moving some of my challenging thoughts and feelings from the left-hand column to the right, phrasing them in a constructive way. And I wanted to design preplanned actions in response to the trigger and the tell that I’d identified. My goals were to practice the new skills I’ve learned, to discover more about Quinn’s thinking, and to ensure Quinn heard just how much his management style grates on me.”

Here’s how Norbert revised his case:

Norbert and Quinn’s Revised Discussion

What Norbert thought and felt |

What Norbert and Quinn said |

Open source seems like the way to go, but I’d also like to hear Quinn’s ideas. |

Norbert: I think we should go with KVM here because it’s so flexible. What do you think? |

That’s a challenging answer. I don’t count “waiting on hold for support” as an efficient use of my time! |

Quinn: It sure is flexible but isn’t our standard. Virt-App is working efficiently on all our existing projects. |

Caught my tell! Does Quinn agree that we’re overdependent on vendors? |

Norbert: Okay—well, actually, it’s not okay, because Virt-App is so inefficient at responding to our requests. I feel really frustrated by the amount of time I spend on hold for their support. I also worry about our level of vendor dependence; does it concern you? |

Training is something to think about, but we have this covered. |

Quinn: That’s a good point. I didn’t know about their poor response time. But what about the retraining costs? I don’t think I could get additional budget for everyone to learn a new tool. |

Not much training needed in fact—everyone’s already using it on their side projects. |

Norbert: Actually, almost everyone already knows KVM. I can check with them to be sure. Do you think that’s a good next step? |

Weren’t you just saying you wanted us to have more autonomy?? This is one of my triggers, so I’ll try raising the issue of autonomy directly. |

Quinn: It’s certainly good to get the information. But don’t let them think the choice has been made; unfortunately, I can’t leave budget-critical decisions like this up to the team. |

I’m hopeful that we can have a meaningful discussion about increasing self-organization. |

Norbert: You know, that doesn’t sit well with me, because I think we need more autonomy, not less. Can we talk more about how we make decisions? |

“This is by no means a perfect conversation,” Norbert said, reflecting on his revisions. “But I managed to share most of my left-hand-column concerns. I also asked three genuine questions, and I caught my trigger and tell signals.”

Try rescoring this second case yourself with the Question Fraction tool or by underlining for transparency and twitches, tells, and triggers, to see if you agree with Norbert that it’s more effective. When you try this yourself, expect the reflection and revisions to be difficult at first, as the skills you are learning are easy to describe but hard to master. In fact it is quite normal to revise the same case multiple times, reflecting on the revisions and rescoring them. It can take several iterations to come up with a satisfactory alternative.

Role Play: Practice Producing a Better Conversation

Role Playing—the fourth of the Four Rs—helps a lot in making these new skills feel natural, so try reading out your revised dialogue with a friend, colleague, or even the mirror. When you speak the lines, consider how it feels to say them, and adjust the dialogue until it feels natural and comfortable. As a final test, reverse the roles with your friend and consider how it feels to hear those words spoken to you. Our experience is that people gain different insights and make different adjustments in each of these steps: writing, speaking, and listening.

“It was a lot harder than I expected to say the dialogue out loud,” reflected Norbert. “Even in the role play, I could feel myself getting angry at the idea that the team couldn’t be part of this kind of decision. And when we did the role reversal and I heard the dialogue played back to me, I realized that I didn’t really share how frustrated I’ve been with the current situation. I made a final revision to share my feelings explicitly, and that sounded much more effective.”

Example Conversation

You can practice your conversation analysis with the following example. Try scoring as we described above, and then rewrite the conversation to address the issues revealed by the scores. Don’t worry if you find this difficult—everyone does at first, and there will be plenty of techniques to try and chances to practice throughout the rest of the book. We’ll walk you through this first example.

Tanya and Kay: Limiting Work in Progress

Tanya says, “I just took a Lean Startup course and drew a value stream map for our Agile software team, where I’m the product owner. I think we need to start limiting our work in progress (WIP) because we have significant buffering at several steps in our development process. One big obstacle is that we’re always waiting for Kay, our tester, to verify the latest changes before we release. I’m sure it’ll be easy to convince her that we should limit WIP to be more efficient.”

Tanya and Kay’s Actual Conversation

Reminder: read the right-hand column first, then go back and read right to left.

What Tanya thought and felt |

What Tanya and Kay said |

Kay is really going to like this! |

Tanya: I have a solution for you! We can finally stop pressuring you all the time to finish your testing before the sprint release. |

Adding capacity at the bottleneck isn’t scalable, and we don’t have budget anyway. I’ll just explain. |

Kay: Great! Are we hiring another tester? We clearly need one. |

Kay will be able to see the benefit, I’m sure. I just can’t tell where we should set the WIP limit to start. |

Tanya: Well, it’s actually better than hiring. What we’ll do is limit the number of tickets that go into the “Ready for QA” column. Would three be about right? |

Hmm, she needs more explanation. |

Kay: Hang on. Isn’t that just going to annoy the engineers more? They’ll have changes piling up earlier in the process. |

We saw a great diagram in the course that should make it clear. |

Tanya: No, that’s the beauty of it. They’ll do fewer tickets to start with because of this thing called “pull.” Let me show you. |

I’m so disappointed! She’s got the wrong end of the stick. Why won’t she let me explain how much easier her job would be with a WIP limit? |

Kay: I’m very skeptical. The execs keep saying we need to get more done, not less. Maybe you can show me later—I have a test to finish for tomorrow’s release. |

I don’t get it—what went wrong here? |

Tanya: Okay, maybe after tomorrow’s standup? |

For this first example, we’ll provide our scores and a revised conversation, but try not to look at our results until you’ve tried the process yourself. And don’t worry if you get very different scores or a wildly varying revised conversation. There are no right answers here; only improvements that work for you. (Review how to find the Question Fraction, unexpressed thoughts and feelings, and triggers, twitches, and tells on pages 39–43.)

The Question Fraction. There’s one question mark in Tanya’s right-hand column: “Would three be about right?” So we’ll add 1 to the bottom of our question fraction. Is this a genuine question? Only Tanya knows for sure, but we suspect it isn’t. She does want to know where the limit should be (she says so in the left-hand column), but it’s hard to believe she’d accept a surprising answer—imagine what would happen if Kay said zero, one hundred, or “Five, but only if they’re written in German.” And when Kay does give a surprising response, Tanya certainly doesn’t seem interested in changing her beliefs or behavior, instead continuing to explain her ideas more clearly and forcefully. So we decide that she had zero genuine questions, giving us a finished score of

Unexpressed thoughts and feelings. As far as we can see, almost nothing makes it across to the right-hand column, so almost everything in the left-hand column is underlined. Tanya thinks Kay will like the solution, that hiring won’t work, and that Kay just needs a sufficiently clear explanation of WIP limits. At the end of the conversation, Tanya feels disappointed and confused, but she shares none of this with Kay.

Triggers, tells, and twitches. Without more examples, it’s hard to firmly identify signals Tanya could use. But one possible tell is her repeated assertions in the left-hand column that Kay just needs more explanation, which we will circle and label as a possible tell. When she notices herself thinking this way, she may want to substitute another behavior.

Tanya and Kay’s Revised Conversation

Here’s a revised version of the conversation. Try scoring it and then decide whether you think it’s more effective. Or would you approach Tanya’s situation differently?

What Tanya thought and felt |

What Tanya and Kay said |

Let’s see whether Kay is interested in hearing about WIP limits. I think they’d really help her. |

Tanya: I just came back from the Lean Startup course and I have a new idea I think you’ll like. Can I describe it and see what you think? |

Great! |

Kay: Sure. But I do have a test to finish. |

Let’s start slowly. Does she see the problem as I do? |

Tanya: Yes, about that—it actually seems like engineers are always waiting for your tests at the end of the sprint. Do you agree that’s inefficient, or do you see it differently? |

Well, fifty-fifty here. She’s proposing hiring, but we don’t have the budget. |

Kay: Of course. That’s why I keep saying we need another tester. |

I’d like to explain this, but I’m trying to learn not to jump to an explanation. Let’s check first—is she open to another solution? |

Tanya: I understand, but I think there might be a different solution besides hiring. I could explain the new idea—would that be interesting? |

Whoa! I didn’t realize what an emotional issue this is for Kay. |

Kay: Frankly, no. I don’t think any crazy new plan is going to help with the stack of tests I get dumped on me every sprint at the last minute. |

Kay’s emotions are more important than WIP limits. I’d like to talk about those first, if she’s willing. |

Tanya: It sounds like you’re feeling unhappy with your workload and how you get assigned tests to do. That worries me more than the workload itself right now. Would you like to talk about that instead? |

Conclusion: Over to You

Now try analyzing your own difficult conversations using the Four Rs technique you’ve learned in this chapter: Record, Reflect, Revise, and Role Play. These techniques will help you have some distance from the conversation so you can see it as another might.

To help the learning go faster, consider reviewing your conversations with other people—they will definitely see it as others do! If you are feeling very brave, consider sharing your analysis with the other person in the conversation to discover their point of view, and ask their advice on how you might have revised the conversation to communicate with them more effectively.

As you analyze your conversations, keep in mind that you already know the result you are after: you want to have the kind of productive conversations you espouse. As we demonstrated at the start of the chapter, Chris Argyris found that we almost universally know the behaviors that will generate the best decisions—behaviors that show we are transparent in sharing our information and reasoning and we are curious about the information and reasoning of others.22 When we can operate with this theory of action, we can harness the strength of our diversity. However, when faced with the challenge of productive conflict, we instinctively shy away from the opportunity and instead adopt a defensive reasoning mind-set to try to minimize threats and embarrassment.

While this defensive reaction is understandable, it isn’t acceptable for those of us who want the benefits of successful transformation. Transformation requires fundamental shifts in how we behave as an organization. Unless we are content to join the 84% of companies who attempt digital transformation and fail, we need to learn to harness our communication superpowers by first undertaking a conversational transformation.

Recording video of your face-to-face conversations at the whiteboard for later review is a great practice that we’d recommend, though it’s underused in most teams we’ve worked with. | |

An extreme version of this distancing was practiced by our friend and teacher Benjamin Mitchell, who used an audio recorder to capture his conversations. He tells us that when he first listened to himself on tape, when he noticed mistakes he was making, he would shout at the recorder, “Benjamin! Don’t do that!” | |

There are two exceptions: First, you may include the other person’s thoughts if you write the case jointly with them—this can be a very rewarding exercise, as well as a terrifying one (see Chapter 5 for an example). Second, the rule does not apply to you if you have developed telepathy. But if you can really read minds, then frankly, most of this book will not be of much use to you! | |

We have recently had success with even shorter “two row” cases, containing just one sentence by you and one by the other person. Key insights can still be found even in very short exchanges, we assure you! |