CHAPTER 3

HERO

YOUNG MAN IN A HURRY

Fired by the success of Scarface, Hughes toyed with the idea of making another aerial film, one based on the exploits of a First World War German dirigible. The Hell’s Angels sequence in which a zeppelin bombed London had been most popular, and the huge blimps were still very much in the news; the Graf Zeppelin had just set a record, crossing the Atlantic in sixty-seven and a half hours. Hughes gave his projected film the title of Zeppelin L-27, but that was as far as it got, for Hughes had a new toy. It would be typical of Hughes throughout his life to focus all his attention and energy in one field only to abandon it suddenly in favor of another. So it was in 1932.

The new obsession was an airplane, a sleek little racer Hughes had bought months before and now housed in an oily, squat hangar in the San Fernando Valley. Through the spring and summer of 1932, Hughes took every opportunity to slip into his Deusenberg roadster and speed toward Burbank to look in on the work of streamlining the plane.

Hughes already owned a small air force. But the racer was special. Built by Boeing for the U.S. Army Air Corps as a military pursuit plane, it was supposedly restricted to air force use, but Hughes had gotten one through “special arrangements” with the Department of Commerce.1 He was the only civilian in the United States to have that privilege. To remodel it along speedier lines, he leased a corner of a Lockheed Aircraft Corporation hangar and hired a crew of mechanics and designers. As expenses rose, and with them a need for better accounting, Hughes established the Hughes Aircraft Company as a new division of the Hughes Tool Company. In the beginning nothing more than a glorified machine shop and a set of books, in time it would become one of the nation’s largest and most powerful defense contractors.

For years, airplanes had provided Hughes with a leisurely escape from pressures on earth. He loved nothing more than rising in the clean air above Los Angeles, flying north over the San Gabriel Mountains, then out across the high deserts toward Palm Springs, and finally back up the coast to the city. At night, he would head far out over the ocean, circle for the return, and watch with growing excitement as the lights of Los Angeles flickered brighter and brighter near land. Hughes was a different man in the air. No longer the shy, tense, highly nervous man people saw on the ground, aloft he was at ease behind a dizzying array of toggle switches and gauges, integrated with the sound of the engine, the feel of the controls, the magnificent view of the earth.

By the summer of 1932, however, aviation was no longer simply a hobby. It had supplanted all the activities he formerly directed from his second-floor office at 7000 Romaine Street, the stucco Hollywood building he had purchased in 1930 as a catchall headquarters for both his motion-picture company and Hughes Tool’s West Coast offices. Although he had never kept regular hours, and often did not appear at Romaine for days on end, now he almost never came in. Instead, he could be found in the Lockheed hangar in Burbank, talking to mechanics and experimenting with aircraft engines.

For all his individuality, Hughes was a child of the age. Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 flight across the Atlantic had launched a new era in American aviation, and Hughes was caught up in it. Americans were obsessed with conquering time and distance. Pilots and aircraft engineers worked feverishly to make planes go faster. Hardly a month went by but some member of this glamorous fraternity mounted a daring assault on the air, and races were the craze of aviation. With his love of machines, it was natural that Hughes would be drawn into this new frontier. Where once he had flown solely for pleasure, Hughes now flew to learn, jotting down observations on wind velocity, air speed, altitude, engine performance, and fuel consumption. He practiced his skills as a pilot, looping, turning and banking, rolling. Also, as a measure of his ripening ego and concern with status symbols, Hughes badgered the Aeronautic Branch of the Department of Commerce to give his pilot’s license a lower number. Charles Lindbergh’s license number was 69, Hughes’s was 4223. In the fall of 1932, the Commerce Department awarded him number 374, and in the spring of 1933 he received number 80, which he kept for the rest of his flying days. To gain experience as a pilot, he signed on under the name of Charles W. Howard as a copilot for American Airways at a salary of $250 a month. As a junior pilot, he made one trip at the controls of a Fokker F-10 from Los Angeles to New York before his identity was discovered and he resigned from the only outside job he ever held.

When the Boeing was remodeled to his satisfaction, Hughes took it up for a test flight. Powered by a 580-horsepower Wasp engine, the plane performed beautifully, averaging 225 miles an hour, a remarkable speed for the time. Hughes decided to enter a race scheduled for Miami in January of 1934.

On his way to Florida, he stopped off in Houston to visit his aunts, Annette Lummis and Martha Houstoun, whom he had not seen in years. Both were much involved in raising four children each. Howard stayed with Annette at the family home, now pleasantly revitalized by Annette’s two sons and two daughters. Dudley Sharp and his wife Tina, whom Howard had also known while growing up in Houston, dropped over one night for dinner. After they had all finished eating, Hughes whispered to Tina: “I’ve got something for you.”2 He bounded upstairs to his room and returned shortly with a photograph of Dudley as a boy that he wanted her to have.

The Boeing pursuit plane obtained from the U.S. Army, 1932.

Philadelphia Inquirer: Charles Bullock

Hughes visited with his young cousins, some of whom he was seeing for the first time. He was especially taken with Annette’s oldest son, four-year-old William Rice Lummis, or Willie as he was called, who was a carbon copy of Howard at the same age. In a letter to Annette, one of only two letters he ever wrote her, Hughes said he thought Willie was “adorable.”3

For the All-American Air Meet in Miami, Hughes entered a category called the sportsman pilot free-for-all. On January 14, 1934, the swift Boeing lived up to his hopes. Averaging 185.7 miles per hour over a twenty-mile course, Hughes nearly lapped his nearest competitor to win his first aviation prize. In the closing ceremonies, he was warmly congratulated and given an impressive trophy by General Rafael Trujillo, the Dominican Republic dictator who presided over the meet.

The Miami victory whetted Hughes’s appetite. The Boeing had performed well, but already he was thinking beyond it. He quietly studied the technical data flowing out of the aviation industry on proposed mechanical innovations and aircraft designs to improve speed. It only remained for some enterprising airplane manufacturer to put all these ideas together into a single plane. His course seemed clear. Why not build his own plane—and while he was at it, make it the fastest land plane the world had ever seen?

Any airplane builder would have constructed a plane to Hughes’s specifications. But Hughes did not want the world to know what he was up to; nor did he want to share any of his ideas with a potential rival. As soon as he returned to Los Angeles, he began pulling together his own team of designers, engineers, and craftsmen.

The young men he selected shared Hughes’s enthusiasm for aviation. It was the Depression and many were thankful just to have a job, much less such an interesting one. To head the team, Hughes hired Richard W. Palmer, a recent graduate of California Institute of Technology and a quiet, reflective man who seemed older than he was. Palmer was already known for his radical ideas about aircraft design when he met Hughes in 1934; a group of his fellow Cal Tech colleagues eagerly followed him to the Hughes job.

To supervise construction, Hughes turned to Glenn Odekirk, a cheerful, thoroughly competent mechanic and pilot Hughes had met during the filming of Hell’s Angels. Hughes gave his team no specific instructions. He just told them in “broad terms” what he wanted: to build a land plane that would fly higher and faster than any other in the world.4

Early in 1934, the Palmer-Odekirk team conducted a series of tests with miniature hardwood models in the wind tunnel at Cal Tech’s aeronautical lab. As each model was readied for testing, Hughes drove out from Hollywood to take a look. Weeks passed as new models were carved, tested, and rejected or modified, until one day the team called Hughes out to Pasadena for an inspection. Bending down to a small window of the wind tunnel, he saw a futuristiclooking model of a racer and watched approvingly as “swiftly moving vapor flowed smoothly over the highly polished hardwood surfaces.”5

To build the plane, Hughes leased a corner of the Babb Hangar at Grand Central Airport in Glendale and ordered his section walled off and sealed to inquisitive visitors. With the eighteen men who made up the team laboring daily in the inner sanctum, the outside world grew curious. Soon the undertaking became known as the Hughes mystery ship. Hughes’s team had another word for it: the H-1. Under the gifted eye of Dick Palmer, a fascinating airplane was taking shape.

Like most racers, it was a single-seater with an open cockpit. It was small, only twenty-seven feet from nose to tail, and twenty-five feet in wingspan. Beyond those mundane features lay a series of innovations that made the H-1 the most advanced plane of its time. Rivets were placed flush with the fuselage to reduce drag. The wings were shortened to increase speed. The single most revolutionary feature was its unique landing gear which did not remain permanently in place during flight, but retracted neatly after takeoff into a snug compartment under the wings. Some of the aircraft’s advanced touches had previously been tested on other planes or written about in technical journals, but no single plane of the time incorporated so many of them.

It was inevitable, as it had been with Hell’s Angels, that Hughes would get far more credit for the H-1 than he deserved. In truth, Hughes was not an aircraft designer nor an especially seminal thinker in aeronautics. He was, however, an excellent brain-picker. “He knew how to get answers,” recalled Robert W. Rummel, an engineer who worked on the H-1 and later worked closely with Hughes at TWA. “He had a habit which I did not really discover until years later. He would call me up and talk about something like wing efficiency. He would want to know my opinion. I’d tell him. Then he would often call back later and say what about this or that, referring to our earlier conversation. Years later I learned he was doing the same thing with five or six guys.”6 By picking brains, Hughes narrowed his options, arrived at the right decision time after time, and wrote aviation history with the H-1. For eighteen months, the work progressed as the plane was assembled, taken apart, then reassembled. Money was no object although the Depression was at its deepest. The old reliable Hughes Tool Company drill bit was still bankrolling Hughes’s dreams.

Hughes’s growing fame in aviation was in fact making him a folk hero to his workers back in Houston. In the past, they had resented him for squandering the profits generated by their labor in frivolous Hollywood movies. But his entry into aviation was viewed much more positively. Hughes was now spending his money for science and for the advancement of aviation. As Hughes recorded one aerial triumph after another, workers proudly clipped the news stories and pasted the mementos in black-bound notebooks.7

As for the tool company’s brass, they wished that Howard had stayed with movies. Colonel R. C. Kuldell, the president and general manager of Hughes Tool since Hughes Sr.’s time, was worried that Hughes was going to kill himself flying airplanes and thus destroy the company that Kuldell and his lieutenants had spent a generation building. If Hughes should die without leaving a valid will, the company would be dismembered to pay federal estate taxes.

Early in August of 1935, Kuldell learned that Hughes intended personally to test-fly the H-1. He could no longer keep silent. On August 12, 1935, he wrote Hughes and his Houston lawyer, Frank Andrews, admitting that he was bringing up an “embarrassing subject,” but one he felt should be discussed “by those of us interested in the continuity of the institution we know as the Hughes Tool Company.”8 Then he got to the heart of his message:

Two events of immediate and impending importance are before us, which lead me to bring this matter to your attention, at this time. I understand that Howard is about to undertake a most dangerous aviation flight, which may not seem dangerous to him, but certainly in the risks which we know are involved in testing new planes, appear to me to be very considerable. The second event is the pending passage of the new inheritance tax bill, which, if not provided against, would leave the Hughes Tool Company almost entirely to the Federal Government.9

Kuldell said he did not know what Howard’s “present will contemplates,” but suggested that he “immediately rewrite it,” leaving a portion of “his estate to his employes and associates.” In this way, the company would not be “disintegrated at [Howard’s] death” by a 75-percent inheritance tax. “While we all fervently hope Howard will be successful in his airplane endeavors or rather that he will not undertake dangerous flights, still the possibility is there, and we would be negligent if we did not strongly urge him to take the necessary precaution.”10

Hughes was just twenty-nine, but already he was finding out what a double-edged sword wealth could be. The money that enabled him to indulge himself in motion pictures, women, airplanes—anything he wanted—was also a constant reminder of his own mortality. Noah Dietrich, Hughes’s financial adviser in Los Angeles, sent Kuldell a reassuring letter saying that Hughes had revised his will and that it “generously” provided for all his top executives.11 In fact, there is no evidence that Hughes executed a will at this time. More likely, Hughes told Dietrich he had inserted a provision in his will giving tool company officers a share in his estate when actually he had done no such thing. Over the years, Hughes raised this stratagem to a high art, thinking that the lucky “beneficiaries” would remain loyal.

If Hughes was outwardly making an overture to placate Kuldell, privately he was displeased with the man who was almost a Hughes family fixture. It was Kuldell who had administered his father’s estate, negotiated with Howard’s relatives to acquire their minority interest in Hughes Tool, and successfully guided the tool company through the Depression’s darkest hours. The company was hard hit in the 1930s, but would have been hurt even more had not Kuldell opened a brewery on the tool company grounds at the close of Prohibition. Cashing in on the wet era, the Gulf Brewing Company rushed into business with a product called Grand Prize Beer, and for a time it was the largest-selling beer in Texas. But now Hughes was turning against the colonel.

The reason was Noah Dietrich. Ever since he had gone to work for Hughes in 1925, Dietrich had been skillfully consolidating his power in the Hughes organization. By 1936, he had only one rival—Colonel Kuldell. As Dietrich’s influence with Hughes grew—aided by his proximity to the millionaire in California—he became increasingly critical of the Hughes Tool Company management in Houston. Gradually, Hughes paid more attention to Dietrich’s persistent complaints. A few months after Kuldell indiscreetly raised the will issue, Hughes sent Dietrich to live in Houston, with orders to keep a close watch over the tool company’s balance sheet. Not surprisingly, Dietrich’s arrival in Houston set off a corporate power struggle. With Hughes firmly behind Dietrich, the outcome was never in doubt. In less than two years, Kuldell was forced out.

RECORD BREAKER

Even though his concern for Hughes’s welfare stemmed in part from selfinterest, Kuldell had not exaggerated the danger Hughes would face if he test-flew the H-1. Everyone around him was uneasy about that. For all its safety features, the H-1 was an experimental plane. No one knew how it would perform in the air. Palmer and Odekirk pleaded with Hughes to let someone else test it. He ignored them. It was his airplane—he would fly it. To allow otherwise would have “shot his pride.”12

On August 18, 1935, at Mines Field, Hughes slipped his long frame into the racer’s cockpit and started the Wasp engine. Motioning that he was ready, he waited for a ground crewman to remove the wheel chocks, then gunned the engine and gave it full throttle. In a few seconds the H-1 was flying. For fifteen minutes it purred over Los Angeles, accelerating up to 300 miles an hour. When word of the flight spread, the aviation world speculated that Hughes would enter the National Air Races over Labor Day and carry off the top prize. Instead, he mysteriously passed up the meet. Ten days later it was clear why.

The racer had performed so well that Hughes was convinced he could easily set a world speed record for a plane flying over land. The existing mark of 314 miles an hour was held by the French pilot Raymond Delmotte. To contest it, a challenger had to fly over an official three-kilometer race course supervised by the National Aeronautic Association. The test was scheduled for September 12, 1935, at Martin Field, a few ramshackle hangars bordering a crude landing strip near Santa Ana, California, now the site of Orange County Airport.

The day was perfect for flying—bright, sunny, and cloudless, with little wind. If Martin Field was an unlikely setting in which to rewrite aviation history, the terrain was at least ideal for the event at hand. All around, the land was monotonously flat with wide-open spaces well suited to the speed runs Hughes had in mind.

Hughes showed up early that morning with his crew and retreated to a hangar to give the H-1 a final tuning. Technicians from the NAA measured off the three-kilometer course, running north to south over a bean field next to the airstrip. A chronograph was installed at each end to photograph and clock Hughes’s plane as it entered and left the course. He would be required to make four consecutive passes at speeds of more than 314 miles an hour to set a new record.

Hughes shook hands with the judges: Amelia Earhart, fresh from her triumph as the first person to fly solo from Mexico City to Newark; Paul Mantz, a Hollywood pilot who had stunted for Hughes in Hell’s Angels and also served as Miss Earhart’s technical adviser; and Lawrence Therkelson, an official of the NAA. Mantz and Therkelson took off in one plane and Miss Earhart followed in another to observe Hughes’s performance from the air. NAA rules required that he could not go higher than 1,500 feet during the record attempt.

Fueled and ready, the H-1 waited for Hughes on the runway, its compact silver body glistening in the sun. Hughes would always be enraptured by the “beautiful little thing”13 he had created, and clad in an odd flying outfit—a rumpled dark suit, soiled white shirt, and tie—he vaulted into the cockpit, fastened his leather cap, and adjusted his goggles. Gunning the engine, he stirred up a cloud of dust, taxied into position, then gave it full throttle and felt the power take over. As the plane lifted off, he leaned forward, flicked a switch on the sponge-rubber-padded dashboard to retract the landing gear, and headed north toward the mountains.

He flew first across the course from north to south, then circled over the ocean and zoomed back across from the opposite direction. In all, he made four lightning runs and easily topped Delmotte’s speed. But by the time of the last run, it was so dark that the cameras could not photograph the H-1 and so Hughes’s bid failed. He would try again the next day.

On Friday, September 13, 1935, Hughes posted speeds of 355, 339, 351, 340, 350, 354, and 351 miles an hour. This time, the cameras recorded his triumph. Even so, the victory was almost pyrrhic. After the last run, Hughes flew on, oblivious to his falling gas gauge. North of the course, the H-1’s engine suddenly conked out before Hughes could switch to an auxiliary tank. As the ship began to lose altitude fast, Hughes thought of bailing out. But that would have meant the end of the H-1, so he decided to ride it down. The plane drifted into a beet field and bounced to a stop. Hughes climbed out unhurt; the racer suffered only minor damage. When he was told that he had set a land-speed record of 352 miles an hour, he coolly surveyed the H-1’s crumpled landing gear and muttered: “It’ll go faster.”14

If Hughes was unimpressed by his first great air record, the aviation world was captivated. No longer just a movie producer who flew as a hobby, Hughes was obviously serious about advancing aviation. Whatever his reasons, no one could deny the superiority of his plane. The H-1 was magnificent, far advanced over all other planes of the time. As usual, Hughes took no credit; he owed it to the plane, he said, and “the boys who worked with me getting the plane ready for the flight. I only flew a perfect machine.”15 But the fame was his.

That fall, Hughes thought about flying the “perfect machine” on to greater glory. The most tempting target was the transcontinental record of ten hours, two minutes, and fifty-seven seconds, then held by Colonel Roscoe Turner, who had worked for Hughes on Hell’s Angels. A simple calculation showed that the H-1, capable of speeds up to 350 miles an hour, could easily eclipse Turner’s time.

While Hughes decided what to do, he spent much of his time in the air, experimenting and testing theories. He was especially interested in high-altitude flying, as a way both to elude bad weather and to increase speed. He had a theory that the instruments used to register speed at high altitudes were inaccurate, and one day he set up an experiment to find out if he was right.

On a map, he laid out a seventy-two-mile-long course from Mount Wilson Observatory, north of Los Angeles, to San Jacinto Peak, to the southeast near Palm Springs. Placing several of his Hughes Aircraft workers at specified points along the route, Hughes flew over the course at fifteen thousand feet. Later, by comparing the readings on his airspeed indicator with the timing of his observers posted on land, Hughes discovered that he had been right.16 His airspeed indicator, calibrated at sea level rather than at high altitude, read fifteen miles an hour slower than he was actually traveling.

In the beet field near Santa Ana, California, with the damaged H-1, minutes after establishing new world speed record for land planes, September 13, 1935.

Wide World Photos

This helped him to another conclusion. “I realized,” he said later, “that by climbing up to the substratosphere, and taking advantage of the westerly wind created by the motion of the earth, I could reduce the time of crossing the continent.”17

It followed that airplanes traveling at high altitudes could fly faster and farther on less fuel, and therefore at less cost, than other planes. Clearly, high-altitude flying was going to mean much to aviation. And to Hughes. But first, there was the transcontinental flight. Plans for that were moving forward, but not plans that included the H-1. The racer was not designed to fly long distances. The search for a plane suitable for the cross-country hop soon turned up the perfect candidate at nearby Mines Field in Inglewood, a single-seat, high-powered Northrop Gamma. There was, however, a large hitch. The plane was owned by a pilot who also aspired to break the coast-to-coast record.

Hughes was a wallflower at Hollywood parties, but he knew how to talk to fellow pilots, most of whom were tough-talking, hard-living men used to facing danger. This pilot, however, was nothing like the others. She was a slim, twenty-six-year-old blonde named Jacqueline Cochran, then quietly on her way to becoming one of the great fliers of her era.

If Hughes imagined Miss Cochran to be an easy mark, he soon found out differently. Unlike Hughes, she had come up the hard way. Born in an impoverished Florida sawmill town, she left home at fourteen to become a beautician before being gripped by a passion for flying that would carry her to international fame. Hughes saw her putting the Northrop through a series of fuel-consumption tests at Mines Field, and then called her late one night just before she went to bed.

“Jackie,” said a voice on the other end of the telephone, “this is Howard.”

“Howard who?” she asked.

“Howard Hughes.”18

Jackie Cochran was certain the caller was a crank. She had never met Hughes, but like other pilots at Mines she admired his “fabulous” racer, which was guarded by a “great army of police.”19 She had seen Hughes from a distance start up the H-1 and “run it up and down the runways” at Mines to give it a workout.20 Hughes had a distinctive voice, high-pitched, nasal, with an unmistakable southern accent. But Miss Cochran had never heard him say a word. For fifteen minutes she insisted that the caller was not Hughes while he sought to convince her that he was. Finally, he succeeded.

“I want to buy your airplane,” Hughes told her.

“Well, it isn’t for sale,” she answered. “I’m going to fly it in the Bendix”—a national race.

“I don’t want to fly it in the Bendix,” Hughes tried to reassure her. “I want to fly it cross-continental.”

“So do I,” Miss Cochran replied, with a firmness that might well have ended the discussion right there if the caller had been anyone other than Hughes.21

But Hughes kept calling—for weeks he pestered Miss Cochran to sell the Northrop. She continued to refuse, but she was short on funds and almost against her will found herself listening to Hughes’s tempting monetary offers. During the negotiations, Hughes invited her to the airport and let her sit in the H-1, although he would not let her fly it. Within four weeks, he had won. Jackie Cochran agreed to lease him the Northrop for nearly as much money as she had invested in the plane. Also, with the greatest reluctance, she gave him an option to buy it. Surveying her finances, she had felt that she “just couldn’t afford to do otherwise.”22

Hughes flew the Northrop to Union Air Terminal in Burbank where Hughes Aircraft personnel, now housed in their own hangar at one end of the field, immediately set about converting the plane for its long flight. The most significant change was in the engine. Once again, Hughes received what he called “special permission” from the U.S. Army Air Corps to use equipment that had been developed exclusively for military use.23 It was a 925-horsepower Wright Cyclone engine capable of generating great power at takeoff and high altitude. By late 1935, the Northrop was refitted and tested, and Hughes waited only for proper weather.

Takeoff was finally set for January 13, 1936. Shortly after noon, with no public announcement, Hughes taxied the heavily fueled Northrop into position on a runway at the Burbank airport. At 12:15 P.M., the plane rolled down the runway, gathered speed, and lifted off for the east. Although the start could not have been smoother, a freak accident—the antenna snapped at liftoff—cost Hughes his radio. He would be out of contact with the ground for the entire trip. Climbing to fifteen thousand feet through “thick” weather, he flew “blind” for two hours.24 He did not see the ground again until Santa Fe. To test his high-altitude theories, he went up three thousand feet more, inhaling oxygen to ward off drowsiness. At eighteen thousand feet, he throttled back the engine, reducing horsepower, and found, as he had theorized, that his speed was not reduced at that rarified altitude.

North of Wichita, Kansas, Hughes ran into rough weather again, this time in the form of turbulent winds. One gust buffeted the plane so strongly that the needle of his compass was knocked off its point. With neither radio nor compass intact, Hughes was forced to fly by sight, and spreading the map on his knees, he charted the remaining twelve hundred miles visually. Luckily, it was a clear night and he was able to make out the cities by their lights. At 12:42 A.M.—nine hours, twenty-seven minutes, and ten seconds after leaving Burbank—Hughes touched down in the darkness at Newark. His lone welcomer was an official timekeeper.

It was a transcontinental record to be sure, but hardly a spectacular victory. He had shaved only thirty-six minutes off Roscoe Turner’s time, and Turner had actually stopped once along the way to refuel. Nevertheless, Hughes’s feat depressed Jacqueline Cochran; she said later that it broke her heart.25 As she had feared when she leased it to Hughes, her plane had enabled him to take her place in breaking the record. Within weeks Hughes set two more records, cutting the flying time from Miami to New York and from Chicago to Los Angeles, and when his lease on Miss Cochran’s Northrop expired, he exercised his option to buy and sent her a check. But a few days later, fickle as ever, Hughes abruptly changed his mind, offering to sell it back to her for much less than he paid, and she readily agreed, baffled by the whole affair. Miss Cochran never did understand why Hughes behaved as he did. He had, she later remarked, a “very interesting streak.”26

As soon as he returned to Los Angeles Hughes set to work remodeling the H-1. The racer was towed into the Hughes Aircraft hangar at Burbank to be made over for long-distance flying so Hughes could try to break his own cross-country record. Larger wings were added, fuel capacity was expanded, a hydraulic mechanism was installed to increase visibility by raising and lowering the pilot’s seat at takeoff and landing. A sleek transparent hatch was placed over the once-open cockpit. So many gauges, instruments, and controls were jammed into the tiny cockpit that mechanics could not install the oxygen tank until they found a niche in the right wing above the landing gear, and ran a tube into the cockpit.

As Hughes waited for work on the H-1 to end, he passed the time by playing a familiar role, that of Hollywood’s most eligible bachelor. He had not made a movie in five years, yet he was still thought of in Hollywood as a movie producer temporarily pursuing other interests. The romance with Billie Dove had long since cooled, but a string of other attractive actresses followed her: Marian Marsh, Ida Lupino, Lillian Bond, and Mary Rogers, among others.

Hughes had also begun cultivating young socialites, some of whose families would have been appalled had they ever seen their daughters’ names in lights. On the night of July 11, 1936, while Hughes was driving one blue-blooded companion home, he struck and killed a fifty-nine-year-old department-store salesman, Gabe Meyer, who was standing in a streetcar safety zone at Third Street and Lorraine Boulevard, a few blocks from Hughes’s Hancock Park home. Because he did not want to “drag her name into the affair unnecessarily,” Hughes told the girl to flee the scene.27 She slipped away and boarded a streetcar. After being temporarily held by police, Hughes was forced by a coroner’s jury to divulge the girl’s name—Nancy Belle Bayly, of a prominent Pasadena family. After hearing Hughes’s description of the accident, in which he said he had swerved to avoid striking another car, the jury cleared him of any blame for Meyer’s death.

Of all the women linked to Hughes at the time, however, only one, Katherine Hepburn, bridged the worlds of society and film in which he moved. Born into an aristocratic Connecticut family, she was already a great actress, and was having trouble getting parts because many male actors shied away in fear of the competition. Hughes and Miss Hepburn, both lanky and angular, both golfers and pilots, made a handsome pair, and pursued her diligently, even clearing a stretch of beach suitable for landing a plane near the Hepburn family summer home in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. When she flew to the Midwest to star in a road production, Hughes followed in his own plane, and never missed a performance. They were hounded, of course, much to their annoyance, by the press and autograph seekers.

Again, rumors flourished, as they had with Billie Dove, yet like almost all of Hughes’s romantic attachments, this one advanced only so far. Although Hughes could be charming, he did not always endear himself to the independent-minded Kate Hepburn. She had, for instance, little taste for luxury, but even so Hughes constantly sent her expensive jewelry, and she in turn, a friend remembered, “was always trying to send it back.”28 When Hughes came to the Hepburn family home in Connecticut, he “was not a very convenient guest, preferring to eat after everyone else had left the table.” Miss Hepburn more than once grew exasperated at Hughes’s behavior, but eventually despaired of getting angry at him because “he couldn’t hear what she was saying anyhow.”29 In time it would end between them because, as one of Miss Hepburn’s friends believed, Kate “got very bored.”30

Anyway, Hughes was concentrating on preparations for his next recordsetting effort. In line with its silvery image, he renamed the H-1 the Winged Bullet, and he flew back and forth several times between California and New York in another plane, plotting the route he intended to take, occasionally stopping over at the Long Island estate of aircraft builder Sherman Fairchild. But flying in those days entailed many risks. On November 15, 1936, while attempting to land a seaplane at North Beach Airport on Long Island, Hughes was caught by a tail wind and crashed.31 It was his third plane accident, but not his last. Hughes escaped uninjured, soon returning to California to begin final planning for the cross-country hop.

On January 18, 1937, the lights in the Hughes Aircraft hangar in Burbank blazed far into the night. Mechanics tested the rebuilt racer while Hughes studied weather reports. He could not have been completely satisfied with what he read. Dense clouds covered most of the country. But the winds were favorable, blowing strongly toward the east. Shortly after 2 A.M., the Winged Bullet nosed onto the runway and taxied into position. Weighed down by 280 gallons of aviation fuel, it roared past an official timekeeper at 2:15 A.M. and soared off into the night.

As in 1936, Hughes ran into unfavorable weather from the start. Climbing to fifteen thousand feet, he leveled off above the clouds and throttled back, only to find conditions still choppy and rough. Adjusting his oxygen mask, he accelerated and began a steep climb to twenty thousand feet.

An hour and a half outside Burbank, he caught a fleeting glimpse of Arizona through a hole in the clouds. Cruising at 330 miles an hour, he settled in for the long flight. Then, with no warning, his oxygen mask failed and the grim effects of oxygen deprivation spread through his body. His “arms and legs were practically paralyzed.”32 He could not even raise his hand to his face. Hughes was gripped by a “helpless, hopeless feeling” that within a few minutes he would doze off to sleep.33 With all his remaining strength, he nosed the ship down, shouting in the cockpit to “equalize the pressure from within his head.”34 It was a solitary performance; his radio had malfunctioned again, but when he dropped down several thousand feet “full consciousness” returned.35 Hughes had escaped from the only “real jam” he had ever faced as a pilot.36

Somewhere over the Midwest, he picked up a lusty tail wind and bolted east into the new day. As he approached the Appalachians, the clouds began to break up and Hughes caught sight of the rolling Pennsylvania countryside as he began the long descent to Newark. At 12:42 P.M., he streaked over Newark Airport for an official coast-to-coast record of seven hours, twenty-eight minutes, and twenty-five seconds. This was an achievement indeed. Averaging 332 miles an hour, Hughes had convincingly beaten his old record and established a time that would hold up for seven years.

“A bit shaky,” he climbed out of the cockpit, weary and splattered with oil.37 This time reporters were waiting, and Hughes smiled as he unbuttoned his flight jacket and jumped to the tarmac. He told of his oxygen problems, then downplayed the flight in his self-deprecating way. The only reason he had made it, he joked, was that he had heard someone was about to try to beat his 1936 record and he wanted to “give them something better than that mark to shoot at.”38 There followed a lot of questions from reporters who knew nothing about airplanes. These Hughes patiently answered, wanting desperately all the while to get away from the crowd. This ambivalence would torment Hughes all his life. He was forever doing things that made him an object of intense public curiosity, only to be repelled by the attention itself.

The 1937 flight made Hughes the undisputed pilot of the year. As winner of the Harmon International Trophy denoting the world’s outstanding aviator, the first of many such awards, he was honored by President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House. On receiving the trophy, Hughes was his usual shy self in contrast to the president, who effervesced about his First World War days when he had flown in navy planes and blimps over wartorn France. Someday, Roosevelt said, looking wistfully at the lanky honoree, he would like to fly with Hughes.

Hughes was not so shy that he was reluctant to try to capitalize on his fame. He felt the Winged Bullet would make an ideal military pursuit plane, and hoped to sell the design to the army air force and begin manufacturing the plane en masse. But the air force declined to buy. Years later, Hughes told a Senate committee that his plane was turned down because of its advanced design, that the air force “did not think that a cantilever monoplane… was suitable for a pursuit ship.”39 In fact, cantilever monoplanes (planes whose wings were supported without external metal braces) were already in use by the government when Hughes made his pitch to the air force. The real reason the authorities rejected Hughes’s plane was that they did not believe it was suitable for combat.

Nor did Hughes’s behavior help matters. After arranging to fly the plane to Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio, where he was to show it off to a delegation of interested air force brass headed by Major General Oliver P. Echols, Hughes failed to keep the appointment. The general and his staff were left fuming on the runway.

RACE AROUND THE WORLD

Whatever his faults, Hughes’s achievements at this time were remarkable. In less than two years, he had flown his way into the record books, establishing every land-speed record of consequence. His fame as a pilot and an aircraft builder was firmly set. But he was also finding that he had succumbed to an unwritten rule which drives all achievers: each new triumph only compels another, greater achievement. For Hughes, that meant he now had to fly around the world.

If Hughes raced planes for glory, he concealed the fact well. Yet it was also true that America reserved its wildest acclaim for pilots who hopped over water, not land. Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic had made him a hero for all time. In 1931, Wiley Post and Harold Gatty had electrified America by circling the globe in eight and a half days. Two years later, the amazing Post flew the same route alone and cut a day off the time. In 1935, Post and the comedian Will Rogers were killed in Alaska at the start of yet another attempt to circle the world.

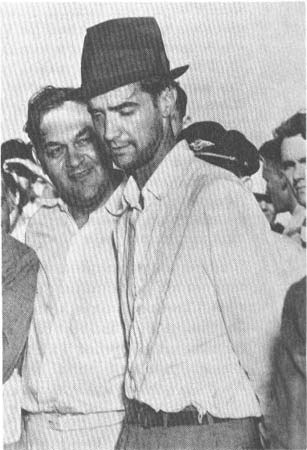

Hughes receives congratulations from Dick Palmer in Newark after establishing cross-country speed record of seven hours, twenty-eight minutes on January 19, 1937.

United Press International

No one admired Wiley Post any more than Hughes. But Hughes had no desire to duplicate the world flight of the colorful, one-eyed Texan. Post had piloted a crude little plane called the Winnie Mae. Hughes planned to fly around the world in a sophisticated machine supported by an expert air and ground crew. No longer should ocean hopping be thought of as the province of daredevils. Hughes wanted to dramatize how a well-conceived, thoroughly planned, and carefully executed flight could be carried out without incident.

As usual, the plane was all-important, and for this flight Hughes chose the Sikorsky S-43, a bulky, twin-engine amphibian. When the plane was delivered in the summer of 1937, Hughes quietly applied to the Bureau of Air Commerce in Washington for permission to circumnavigate the globe. Not convinced that there was any scientific merit in the flight, the bureau turned Hughes down.40

Hughes, of course, was not easily discouraged, and the following spring he reapplied, citing his already elaborate preparations as a reason why the flight should be approved. This time a more receptive bureau was about to issue a permit when an S-43 crashed. The accident made the agency apprehensive about approving a long flight in a similar airplane, and on May 23, 1938, the bureau informed Hughes that approval was being held up until the Sikorsky accident had been thoroughly investigated.41

This threatened to delay Hughes’s world flight for another year. His meteorologists had studied weather patterns along the route and had decided that in early July the least amount of bad weather was likely to be encountered. But if the flight was to be made then, Hughes had to prepare now. With the flight in jeopardy, he moved swiftly to keep his hopes alive.

Lockheed Aircraft had just put the finishing touches on a sleek, twinengine passenger plane—the Lockheed 14—capable of carrying up to twelve people. Hughes conducted hurried talks with Lockheed to acquire one of the new models and in late May requested permission to use the Lockheed for the world flight. While Hughes awaited the government’s decision, Glenn Odekirk and his other mechanics worked day and night to ready the ship.

The Lockheed underwent substantial changes at the Hughes Aircraft hangar in Burbank to make it airworthy for the fifteen-thousand-mile flight. Determined to avoid the radio mishaps of earlier flights, Hughes installed three separate transmitters, the largest a 100-watt unit designed and built by his own technicians. To give it more power and range, the Lockheed was also fitted with two specially supercharged Wright G-102 Cyclone engines.

Nothing reflected aviation’s advances more than the Lockheed’s crowded instrument panel. Lindbergh flew the Atlantic with only a compass to guide him and his two hands to keep the Spirit of St. Louis on course. His instruments consisted of an oil-pressure gauge, an oil-temperature gauge, a turn-and-bank indicator, an earth-inductor compass, an airspeed indicator, an engine crankshaft-speed counter, navigation and landing light switches, an altimeter, and an ignition switch—that was all.

Hughes’s Lockheed had an automatic pilot that could fly the ship on a predetermined course for hours at a time, oil-pressure and oil-temperature gauges for each engine, cylinder-head-temperature gauges for each engine, four fuel-capacity gauges, an airspeed indicator, dual manifold-pressure gauges, dual artificial horizons, a directional gyrocompass, an engine-exhaust analyzer, two sensitive altimeters, a flap-position indicator, a wheel-position indicator, revolution counters for each engine, oil-pressure gauges for the hydraulic system, light switches for the entire ship and instrument panel, radio-control switches, tuning grinders, volume rheostats, propeller-pitch controls, flap controls, landing-gear switches, fuel-mixture controls, carburetorheat controls, trim-tab controls, fuel-tank selector switches, dual magneto switches, wobble pumps for the hydraulic system and fuel tanks, fuel-flow meters, dual controls for engine cowling, cooling grills, and throttles.

While Hughes planned, he also indulged his passion for tinkering with his “Last Will and Testament.” Except for providing a “pension” of $20 a week to a Houston servant, Lily Adams, and monthly pensions of $150 each to two servants at his Muirfield Road house, Beatrice Donner and a male servant he identified only as “Mr. Henry,” this new will was similar to earlier versions.42 The bulk of the estate was left to medical research. His executors were to establish the Howard R. Hughes Medical Research Laboratories in Houston to combat “the most important and dangerous diseases” afflicting that part of Texas.43

The summer before, Amelia Earhart had mysteriously disappeared in the South Pacific near the end of her around-the-world flight. The way she had just vanished made a deep impression on Hughes. He now set down a series of detailed instructions governing the reading of his will “in the event… it should be deemed that I may be dead, but not conclusively so proven….”44 If he were lost, the First National Bank in Houston was to hold his will unopened and not allow his estate to be probated for three years after his “disappearance.”45 Hughes put the instructions in an envelope labeled “No. 1” and the will in another marked “No. 2,” and mailed them on March 3, 1938, to the bank.*

Although he had not yet received government approval for the flight, Hughes was confident he would get it, and on the Fourth of July, 1938, he and a four-man crew flew to Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, the traditional jumping-off point for transatlantic flights. The men he selected were seasoned aviators: Edward Lund, a thirty-two-year-old Montana native, was the flight engineer; Richard Stoddart, a thirty-seven-year-old New Yorker who worked for the National Broadcasting Company, would handle the radio; Lieutenant Thomas L. Thurlow, thirty-three, had been borrowed from the army air corps as navigator; and Harry P.M. Connor, thirty-seven, a Department of Commerce employee who had flown the Atlantic once before, was the copilot and backup navigator.

Before flying to New York, Hughes said only that he planned to try to set a record from New York to Paris. Lindbergh’s thirty-three and a half hours, set on the memorable 1927 flight, was still the best time between the two cities. But speculation preceded Hughes east that the Paris hop was only the start of an around-the-world flight, and Hughes found his life miserable from the moment he landed in New York.

A crowd of several thousand mobbed him and the crew at Floyd Bennett. For the next few days, Hughes spent most of his time dodging reporters and photographers, holing up in a newly finished pavilion of the upcoming New York World’s Fair, reading weather reports, studying the flight plan, and directing last-minute preparations. As a favor to Grover Whalen, the promo-tion-minded chief of the fair, Hughes agreed to call his flight a goodwill mission promoting the international exposition, and he even named the Lockheed the New York World’s Fair 1939. But Hughes’s only real concern was the flight itself, and for days it was actually in doubt. A frustrating series of delays kept postponing takeoff. First, government approval did not arrive until July 8. Then there were mechanical problems with the Lockheed. Finally, by late afternoon July 10, 1938, the last repairs had been made and the crew was satisfied that the ship was ready to fly.

When Hughes arrived at hangar No. 7 at about 6 P.M., he was handed the latest weather reports. New York was miserably hot and there was a threat of rain, but over the Atlantic the weather looked good. Everything had led to this moment. There was no more reason for delay.

Grover Whalen drove Hughes out to the runway so he could choose the direction for takeoff. The wind was no problem, blowing softly from the south. But as Hughes looked down the narrow strip of pavement, he felt a twinge of anxiety. Loaded with 1,500 gallons of aviation fuel, 150 gallons of oil, and a laboratory full of equipment, the Lockheed weighed nearly thirteen tons. It was so heavy, in fact, that Goodrich had fashioned special tires to support it. Would Floyd Bennett’s short thirty-five-hundred-foot runway be long enough? Hughes guessed that he would need every inch of it. After checking both ends, he decided to take off to the south, where the paved runway gave way to a flat, smooth stretch of earth.

Hughes was ready to go, but Whalen had arranged a brief ceremony. The Lockheed was towed to a spot in front of the administration building where five thousand people were waiting to witness the takeoff. When Whalen lined up Hughes and his crew in a half circle beside the plane facing the crowd, Hughes’s companions appeared relaxed and cheerful, as if, one reporter noted, “they were just shoving off for a trip to the beach instead of a flight across the ocean.”46 Hughes, however, looked solemn, nervous, anxious to get under way. Clad in wrinkled gray trousers, a white shirt open at the throat, and a battered brown hat, he stood in silence, hands behind his back, head down, as Whalen’s voice boomed out over the public-address system. Christening the Lockheed in the name of the World’s Fair, Whalen looked up at the plane and called it a “vivid symbol of the possibilities of international cooperation.”47 Then he turned to the five men beside him, wished them good luck, and praised their courage. Thousands of eyes fastened on Hughes, who grew more uncomfortable, seemingly embarrassed at Whalen’s praise.48

When Whalen asked him to say a few words, Hughes nervously pulled a piece of paper from the pocket of his gray trousers. To make sure he was not speechless, he had hurriedly scribbled a brief message. As sweat ran down his back in the early evening heat, Hughes bent forward to speak:

“We hope that our flight may prove a contribution to the cause of friendship between nations and that through their outstanding fliers, for whom the common bond of aviation transcends national boundaries, this cause may be furthered.”49

Putting away his note, Hughes turned to the throng of reporters and photographers who were hanging on his every word and move.

“I want to apologize to the newspapermen and photographers if I seemed rude and impolite last night,” he said. “I had received favorable weather reports and had only the thought of hopping on my mind. I did not mean to be rude or impolite and I want to apologize now.”50

As Hughes turned away, the newsmen applauded.

Just as the ceremonies were breaking up, a young woman slipped through the cordon of police around the plane and pressed a wad of chewing gum to the tail. She was Mrs. Harry Connor, the wife of the copilot, and she told a reporter, “That’s for good luck. I told Harry to be sure and bring it back to me.”51

The tension so evident in Hughes’s face when he was standing on the apron vanished the moment he was behind the Lockheed’s controls. He slid back the pilot’s window and waved to the crowd. Starting first the right engine and then the left, he quickly warmed them up and, with Ed Lund in the seat beside him, and Thurlow, Stoddart, and Connor in the cabin to the rear, Hughes taxied the plane to the northwest end of the runway shortly after 7 P.M. At thirteen seconds past 7:19 P.M., he pulled both throttles wide open. Spectators heard a thunderous roar and watched a cloud of dust billow up behind the plane, silhouetted in the setting sun.

At first sluggish and slow to respond, the Lockheed gradually picked up speed, the runway rumbling underneath. Its enormous bulk finally set in motion, the Lockheed was screaming by the time it passed the halfway point at the administration building. Concentrating on the runway ahead, Hughes felt the ship quicken as he bore down the course. He was rapidly gaining speed, but he was also rapidly nearing the end of the runway. Would he make it? He was almost out of pavement when he felt the tail go up. There was a slight bump as the wheels left the pavement and grazed the hard earth beyond it.

The crowd gasped when it saw the plane leave the pavement and kick up a cloud of dust. For a moment, the Lockheed’s roar altered, as if the engines had been throttled back. Then their full thunder came echoing out of the distance. When the dust cleared, the spectators could see the ship just barely aloft. Groaning low over the red clover carpeting the south end of the field, the Lockheed began a slow climb. Hughes banked to the left over Jamaica Bay and started across Long Island. He “dipped the wings” over Katherine Hepburn’s Old Saybrook home, pointed the nose toward Boston, and made for the great circle route.

It was 7:20 P.M., July 10, 1938. The world flight had begun.

Hughes’s flight was the most thoroughly planned private aviation endeavor of its time. Despite all the aeronautical progress that had been made since Lindbergh’s solo jaunt to Paris eleven years before, ocean flying was still hazardous. Hughes and his team had spent months studying weather data, flight plans, and technical material about their plane. They had meticulously gone over each leg of the journey on paper, rehearsing the flight so they would know what to expect along the way. An elaborate radio system had been set up, tying them into ships at sea and ground stations around the world to keep them in constant radio contact the entire trip. Spare parts, including the specially made tires, had been stored at cities and towns where they might have to land. Hughes had tried to envision every conceivable problem. But who knew what would happen over the Atlantic? In a few years flying across the ocean would be commonplace, but in 1938 it was still a daring novelty, full of unknowns.

Like Lindbergh, Hughes had chosen to follow the great circle course, the shortest distance between New York and Paris, 3,641 miles. The route would take them over Boston, Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Island, and Newfoundland. From there it would be eighteen hundred miles of open ocean to Ireland. The flight went smoothly at first, as the East Coast glided by below, but near Newfoundland the Lockheed suffered its first mishap. The automatic trailing antenna broke, and the plane was out of radio contact for an hour and a half while the problem was corrected.

At 1:30 A.M., they were over the ocean. Flying at seventy-five hundred feet, Hughes noted his speed—192 miles per hour—in a logbook that was rapidly filling up with his notations about altitude, wind velocity, and engine performance. Below him was the Atlantic, but he never saw it so dense was the cloud cover that separated them from the sea. Off Newfoundland, Hughes began bucking strong winds, and he was forced to turn the engines up to maintain speed. When the foul weather persisted, Hughes realized that he was burning an alarming amount of fuel. For the first time, it occurred to him that he might not make Paris. At 2:30 A.M., he was so concerned that he radioed back to his ground crew in New York:

“I hope we get to Paris before we run out of gas, but I am not so sure. All I can do is to hope we will get there. I hope that we will have enough gas to reach land. I am throttling back the engines as fast as the reducing load permits.”52

In time, they flew out of the squally weather and picked up a strong tail wind. Barring further misfortune, he reckoned they would make Paris. As dawn broke, they caught a glimpse of earth through a hole in the clouds, just barely making out Valencia on the southwestern tip of Ireland. Then the clouds closed in again and they were sealed off from the earth once more. As they approached the French coast, Stoddart talked by radio to the French liner Ile de France below them at sea. The ship radioed Le Bourget Airfield in Paris that it was calculating Hughes’s position and would relay it shortly. But the Lockheed was flying so fast (220 miles an hour on the power dive to the French capital) that by the time the ocean liner reported back, Hughes was already on the ground at Le Bourget.

The speed astonished the French. Sixteen hours and thirty-eight minutes after leaving New York, Hughes was in Paris. No one had thought the trip could be made in less than twenty-four hours. Hughes had cut Lindbergh’s record in half. A light drizzle was falling when he landed, about 4 P.M. Even so, thousands of Parisians flocked to the airport to get a glimpse of the marvelous plane and its mysterious pilot. Looking tired and drawn, Hughes was the first out. American Ambassador William C. Bullitt rushed to shake his hand.

“Congratulations,” he said. “Did you have a good trip?”

“We had a good flight,” was all Hughes could answer.53

Bullitt offered to let Hughes and his crew rest at his Paris home. Hughes thanked him and declined. As expected, Paris was only the first stop. Hughes was in a hurry to get under way on the next leg—to Moscow, 1,675 miles east. But suddenly what was to be only a brief stop became an agonizing delay when it was discovered that a rear landing strut had been damaged on the New York takeoff. The French doubted that the part could be fixed, but through the perseverance of Ed Lund, the gritty flight engineer, it was. Even so, the delay lasted eight hours.

At midnight, the Lockheed was towed on the floodlit runway to the spot where Lindbergh had landed in 1927. The rain had stopped, but crosswinds promised to make takeoff tricky. After receiving a warm sendoff from the French and stuffing his pockets full of congratulatory telegrams from home, Hughes buckled himself into the pilot’s seat, gave both engines full throttle, and the big ship rolled. Slowly, it rose, climbing to fifty feet. Then it leveled off and actually dipped. The crowd gasped. In the cockpit, Hughes was locked in mortal struggle with the wind, his hands straining at the controls. Gradually, the plane gained altitude, and in a few moments disappeared into the night.

At 11:15 the next morning Hughes reached Moscow. The Russians had gone all out to make him feel at home, and had even rounded up a box of Cornflakes for his breakfast. But Hughes was driven now, oblivious to food, wanting only to refuel and get under way. Well-intentioned though they were, the Russians had interfered with his plans, swarming around the Lockheed and showering him with questions and praise. Hughes was grateful when the noted Soviet pilot Mikhail Gromoff sensed his anxiety and pulled Hughes aside.

“I know what long flights mean,” confided Gromoff, who had set a record the previous summer by flying from Moscow to San Jacinto, California, in sixty-two hours, “and so none of us will brother you any more.”54

The Russians replenished the crew’s dwindling stocks of food and water, although Hughes turned down a generous going-away gift of caviar because “every pound counts.”55 After taxiing up and down the runway for fifteen minutes, the five took off for the long haul across Russia.

Back home, the flight was building Hughes into an ever-greater national hero. Americans were eagerly following the flight step by step. It was frontpage news every day and the lead story on radio newscasts. Babies were being named after Hughes. Anyone with the courage to challenge the air and win was automatically a hero, yet there was more to Hughes’s appeal than that. To millions of Americans, Hughes was a romantic, mysterious figure. Was he movie producer or pilot, aircraft designer or playboy, shrewd capitalist or lucky heir? He defied categorization. Whatever he was, Hughes was leading a highly individualistic life. His achievements were enough to give anyone an oversize ego, yet he appeared to be humble, modest and self-effacing. Of all his qualities, the one that earned him the highest marks was his refusal to rest on his father’s money. By putting his fortune to work, Hughes had avoided the most unforgivable sin in work-oriented America: he had “not allowed himself,” as The New Republic put it, “to be spoiled by inherited wealth.”56

On through the Russian night the Lockheed flew, deeper into the heart of central Asia. It was the middle of the night when the crew landed at Omsk, an industrial city in western Siberia whose airport reminded Ed Lund of a cabbage patch. They would soon be flying over some of the world’s most desolate terrain, so Hughes ordered the Lockheed’s fuel tanks filled to capacity for the first time. Loaded with 1,750 gallons of aviation fuel, the plane just barely got off, after struggling down a muddy, slippery, and perilous runway.

Ten and a half hours later, they set down at an even more remote outpost—Yakutsk, in northern Siberia. When an interpreter failed to meet them, the crew luckily found a schoolteacher who could speak English, and with her help the Lockheed was refueled, checked out, and put aloft again, on its way to Fairbanks.

To Lund, every takeoff was a “thrill,” but the one at Yakutsk surpassed all that had gone before.57 First came a magnificent sight: the sun and moon suspended at the same time above the earth, and then the menacing jagged forms of a Siberian mountain range looming up unexpectedly ahead of them. Their maps, supplied by the United States Hydrographic Survey, gave the maximum height of the mountains as sixty-five hundred feet. Hughes’s altimeter showed they were flying at seven thousand, yet they were headed right into the side of a cliff. Hughes jerked the Lockheed into a swift ascent, watching nervously as ice began forming on the wings. At ten thousand feet, with the ice growing heavier and the Lockheed straining to gain altitude, Hughes gently slipped the plane over the ninety-seven-hundred-foot crest of the range. “It’s a damn good thing I didn’t try to fly out of Yakutsk at night,” he said.58

At 3:01 P.M. on Wednesday, July 13, they landed at Fairbanks. Wiley Post’s widow was there and sent them on their way with a tearful farewell. The next morning, they refueled in Minneapolis and chalked up another record of sorts, the shortest pit stop of the flight—thirty-four minutes. They were eager to get going now, hoping for a smooth flight to New York since Hughes had insisted on staying at the Lockheed’s controls for the entire three-day trip. Instead, the plane bucked dirty weather all the way. Hughes was bone-tired, yet he held on to the controls, nosing through one volatile cloud bank after another across the Great Lakes.

At 2 P.M., Hughes passed over Scranton, Pennsylvania, and began the descent to New York. A message flashed over the Lockheed’s radio from Floyd Bennett Field—an orderly reception was planned for the crew’s arrival: “You are in no danger of being mobbed.”59 At 2:33 P.M., the Lockheed broke through a bank of low-hanging clouds west of the airport. Hughes planned to fly over the field, then turn around over Jamaica Bay, come back, and land to the north. As he passed over the administration building, he looked down and shuddered.

A surging mass of people lined streets, sidewalks, and fences bordering the airfield. They were standing on cars, chairs, trucks—anything they could find—waving frantically and cheering as the silver plane swooped by. Police were trying to keep order, but thousands had already spilled over onto the tarmac where Hughes was expected to bring the plane to a stop. By the time he had finally come around and brought the ship in, twenty-five thousand cheering, hysterical people were there to greet him.

It was 2:37 P.M., July 14, 1938. The New York World’s Fair 1939 had set a record for flying around the world—three days, nineteen hours, and seventeen minutes. From now on, Howard Hughes was going to find out what it was like to be one of the most famous men in America.

Grover Whalen had spent a hectic morning putting the finishing touches on the welcoming ceremony. As the man who had welcomed Lindbergh back to New York, Whalen considered himself an experienced hand at the tricky business of controlling the mass hysteria generated by aviation heroes. Hughes was to taxi up to a certain spot on the apron. Then police would cordon off the plane. The flier would step out and place a wreath on the spot where Wiley Post had ended his memorable 1933 world flight. There were to be short speeches by Whalen and Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia and a few remarks by Hughes. It was to be a dignified end to the great flight.

But all of Whalen’s plans went awry. Hughes taxied to the wrong location. The welcoming committee, the press, and even the police who were to guard the plane were all waiting several hundred yards down the field. When the Lockheed stopped and cut its engines, the throng broke into a mad dash for the plane. Meanwhile, hundreds of spectators began streaming through barriers onto the field. By the time Whalen and LaGuardia arrived puffing at the New York World’s Fair 1939, there was pandemonium. Connor, Thurlow, and Stoddart were the first to squeeze their way out. Then Hughes, unshaven and smeared with grease, poked his head out, wearing a look that one writer described as midway between a frown and a blush. When he finally clambered down, he was swallowed up by the enthusiastic crowd about evenly made up of those who wanted to snap his picture and those who wanted to snatch a piece of his clothing.

He was borne along to a makeshift reviewing stand at the Lockheed’s wing tip, where LaGuardia warmly clasped his hand and threw a momentary hush over the crowd.

“Seven million New Yorkers,” said the little mayor, his voice rising emotionally on the scratchy public-address system, “offer congratulations for the greatest record established in the history of aviation. Welcome home.”60

The mayor motioned Hughes to the microphone and stepped back to let the hero speak. Hughes was so tired, his voice so weak, that his words were inaudible. “Louder, Howard,” someone shouted.

“I am ever so much honored,” he finally said. “Thank you very much.”61

With a wedge of police “half dragging them through the galloping crowd,” Hughes and his crew were led to a press tent nearby to give interviews.62 It proved just as chaotic there, with spectators jostling newsmen and departing planes drowning out conversation. Whalen quickly adjourned the session, hustling Hughes into a waiting limousine and whisking him along crowd-lined streets through Brooklyn and Manhattan to Whalen’s home, at 48 Washington Mews in Greenwich Village. Sipping a light scotch and soda, Hughes told newsmen of the flight. He was patient, alert, and cooperative. Then, leaving the crew to answer questions, Whalen ushered Hughes upstairs, where the hero “luxuriated in his first bath in a week.”63

Hughes asked for a clean shirt, and Whalen sent his Filipino valet, Juan, to purchase one. Juan, who was furious the next day when news stories referred to him as “Whalen’s Chinese valet,” returned shortly with a fresh white shirt, size 15 1/2, and Whalen told Hughes to come down and rejoin the rest of the group when he was dressed.64

When half an hour had gone by and Hughes had not returned, LaGuardia became nervous.

“Don’t think he fell asleep, do you, Grover?” the mayor asked.65

Whalen went to check. Upstairs, the room where he had left Hughes was empty. He searched the other second-floor rooms but found no sign of the guest of honor. He went downstairs and checked the back door, which opened onto a central courtyard that led to Eighth Street. The door was unlocked. When Whalen broke the news to LaGuardia, the mayor flew into a rage, and Whalen feared for a moment that his wife’s “treasured antiques would be shattered.”66

Hughes had indeed quietly slipped out, hailed a cab, and given the driver the address of Katherine Hepburn’s Turtle Bay town house. When the cab neared her home, Hughes saw a crowd of reporters and photographers camped out front, and the motioned he driver to go on. Their reunion would have to wait. The driver dropped him off a few minutes later at the Drake Hotel on Park Avenue. Hughes trudged up to his suite, alone, for his first night’s sleep in four days.

The next day, New York went wild. More than a million people lined the sidewalks, roaring as Hughes and his crewmen passed by in open cars. More confetti and streamers rained down on them than New York had showered on Lindbergh eleven years before. About three-quarters of a million people were packed into the short stretch of lower Broadway from the Battery to City Hall. As usual, Hughes had trepidations about subjecting himself to such hysterics. While he sat in an open car waiting for the motorcade to begin at the tip of Manhattan, he was nervous and tense. He kept “biting and licking his dry lips” and taking off and putting on his old hat.67

“He seemed relieved when the signal came for the procession to start up Broadway,” wrote a New York Times reporter:

Led by a detachment of mounted police, the motorcade rolled slowly along Battery Place to Broadway, teeming with ticker-tape and sound. At first reluctant to follow Mr. Whalen’s example, Hughes finally hoisted himself to the top of the back seat and looked up at the towering buildings with their festoons of papers and myriad eyes all peering down at him. For a time he clutched his hat in one hand and then the other, but before Wall Street was reached, he had let it fall, forgotten, to the floor of the car.

As the procession moved slowly up through the canyon of steel and concrete, the paper snowstorm grew in intensity, long strings of ticker-tape floating in the breeze and festooning itself around cornices and even the spire of Old Trinity. In the brief intervals of silence when cheering died, the paper streamers whispered in the breeze.

Shy and embarrassed at first, Hughes gradually relaxed and seemed to be caught up by the hysteria around him. He waved constantly in response to the cheering and by the time City Hall was reached… he was smiling broadly and seemingly enjoying himself.68

In contrast to the bedlam the day before at Floyd Bennett Field, the ceremony went smoothly at City Hall, where several hundred perspiring fans were packed into the City Council chamber. The only slipup came when Whalen spoke of the hero as “Edward Hughes.” After the usual speechmaking, Jesse H. Jones, chairman of President Roosevelt’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation, rose to introduce the aviator. A fellow Houstonian, Jones had known Hughes Sr. and had watched young Howard grow to manhood. He gave a glowing introduction of the young man he had come to admire.

Then Hughes rose, fumbled with some handwritten notes, and slowly began to speak:

I haven’t a great deal to say about this, because I am afraid I might get a little nervous and not say just what I want to. However, I haven’t it all, because the newspapermen took about half of it away from me. I will just have to do the best I can. At least you may be assured no one has written this for me but myself.

I am not very good at making speeches, and I have consented to make this one only because there is one thing about this flight that I would like everyone to know. It was in no way a stunt. It was the carrying out of a careful plan and it functioned because it was carefully planned.

We who did it are entitled to no particular credit. We are no supermen or anything of that sort. Any one of the airline pilots of this nation, with any of the trained army or navy navigators and competent radio engineers in any one of our modern passenger transports, could have done the same thing. The airline pilots of this country, who in my opinion are the finest fliers in the world, face much worse conditions night after night during every winter of scheduled operations of this country.69

If credit was due anyone, Hughes went on, it should go to the men who designed and perfected the “modern American flying machine and its equipment.” The speed record he had set, Hughes told them, was secondary to the fact that the flight had been carried out as planned with no unscheduled stops. He was especially proud that the flight had reestablished the United States as a leading force in aviation.

“The airplane was invented and originated in the United States,” he said, “yet since then, the countries of Europe have taken from us one by one every record of major importance.” The flight demonstrated to Europeans, he continued, that Americans can build airplanes “just as fine and just as efficient… as any other country.” If the sale of American planes would “increase only a little bit,” Hughes said, he would feel “more than ever that the flight was worthwhile.”70*

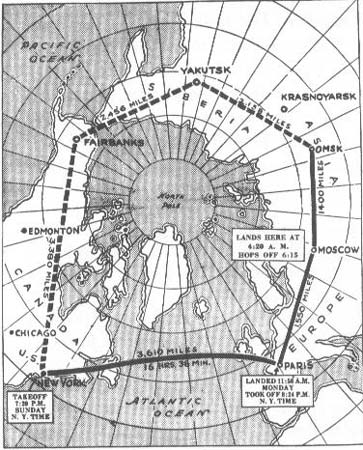

THE AROUND - THE - WORLD FLIGHT

The Lockheed 14 above Manhattan on a test run before the world flight, July 1938. United Press International

Hughes talking to reporters in Minneapolis as the Lockheed was being refueled for the final leg to New York, July 14, 1938. Wide World Photos

The route of Hughes’s 1938 world flight after stops in Paris, Moscow, and Omsk. The Lockheed 14 made additional stops in Yakutsk, Siberia, Fairbanks, Alaska, and Minneapolis, Minnesota (not shown on map) before returning to New York. United Press International

Hughes and his crew on the steps of City Hall in New York. Left to right: Edward Lund, flight engineer; Richard Stoddart, radio engineer; Lt. Thomas L. Thurlow, navigator; Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia; Hughes; Harry P. M. Connor, navigator and copilot; and Grover Whalen behind Connor. Wide World Photos

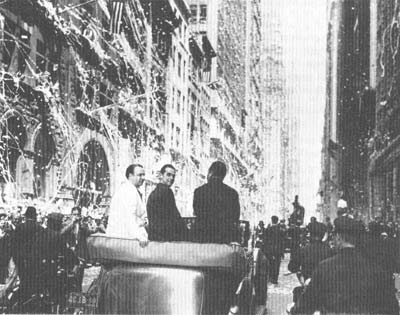

Ticker-tape parade on Broadway in New York, July 15, 1938. At left is Al Lodwick, Hughes’s press agent, and at right is Grover Whalen. United Press International

In the next few days, Hughes went on to more parades and more celebrations in Washington and Chicago. He was now eager to return to California, but Jesse Jones prevailed on him to make one more appearance. His hometown, Houston, wanted to give Hughes a hero’s welcome. Like Lindbergh before him, Hughes was tired of clawing crowds and the mass adulation that accompanied instant fame. Unlike the Lone Eagle, whose disdain for people turned quickly to outright hostility after his epic flight, Hughes hid his feelings, and on July 30, 1938, flew to Houston in the Lockheed for the most tumultuous reception of all.

Ten thousand people had overrun the city’s modest airfield, which had been hastily renamed Howard Hughes Airport by the city fathers. And two hundred fifty thousand persons-three-fourths of the city’s population—lined downtown streets and showered Hughes and his crew with confetti and cheers. That night, at a banquet at the Rice Hotel, with his aunts Annette Lummis and Martha Houstoun next to him, and the eyes of dozens of childhood friends and longtime associates of his father upon him, Hughes bowed his head when Governor James V. Allred of Texas turned to him and said: “All of Texas is proud of your achievement.”71

Hughes rose to acknowledge the applause.

Anything which I have done which you may consider worthwhile has been made possible by the genius of my father and the faithfulness, diligence and enterprise of the men who comprise the various parts of the company he created….

Coming from Texas peculiarly fits a person for flying around the world. There’s nothing you can see anywhere that you can’t see in Texas, and after you’ve flown across Texas two or three times, the distance around the world doesn’t seem so great.

He emphasized that “everyday service” was more important than “spectacular flying.” His audience laughed when he told them, in all seriousness, that he could not get a job as a “first pilot” on any airline in the country.

“Don’t laugh,” he shot back, “for that’s really true. I would have to serve a long apprenticeship as a second pilot before I could hold a first pilot’s job.”72

All in all, though, Hughes seemed genuinely moved by the huge outpouring for him.

“Let me tell you one thing,” he said, in closing, “this day will never be forgotten by me.”73

It was after midnight before Hughes arrived at his family home on Yoakum Boulevard, anxious to get to bed. Much to his surprise, a group of old Houston acquaintances he had not seen in years were waiting on the back porch to say hello. Hughes sat with them for a while, reminiscing and talking about the flight. After they left, he told Annette that he was “shocked” that they had stopped by. “I didn’t think any of my friends would speak to me after Ella and I got a divorce,” he told her.74

He spent the next morning, a Sunday, visiting with more Houstonians and relatives at the Rice Hotel, although there were so many there to see him that he had time to do little more than shake hands and say hello. His tight schedule called for him to fly out around noon for the West Coast. Accompanied by Annette and Martha, he made a quick trip to the sprawling Hughes Tool Company works on Houston’s east side to pay a rare personal visit to the institution whose profits had underwritten his rise to fame.

Even though it was a Sunday, the work force had been called together. It was not every day the thirty-five hundred workers got a chance to see their illustrious proprietor. Hughes was reunited with employees he had not seen in years and introduced to others for the first time. He was led around the plant by crusty Louis Enz, the plant superintendent, who had first shown Howard how to operate a lathe as a boy. There was always a soft spot in Hughes for anyone who introduced him to the wonders of machinery, and he had kept in touch with Enz by sending him personal greetings and gifts at Christmas. One year it was a tailor-made camel’s-hair coat that Enz treasured.

Later, at the airport, a crowd of several hundred broke through police lines and besieged Hughes’s car as it pulled into the hangar where the Lockheed was being readied for takeoff. For twenty minutes, people thrust scraps of paper, dollar bills, and other objects into the car for Hughes to sign. Sitting between Annette and Martha, he appeared in high spirits and patiently signed everything except two-dollar bills.

“No deuce notes,” Hughes told one autograph hound who was waving a two-dollar bill in his face. “I’m afraid I’m too superstitious to sign my name to a $2 bill.”75

Shortly after noon on July 31, 1938, the New York World’s Fair 1939 was refueled and ready. Hughes said good-bye to Annette, Martha, and a host of Gano cousins who were there from Dallas. Roaring down the runway of the airport that now bore his name, Hughes took off at 1:35 P.M. into a nasty cloudbank that quickly blotted out his hometown.