CHAPTER 8

SEEDS OF DISASTER

THE RISE OF THE MORMONS

IN October of 1954, Hughes asked a favor of an old acquaintance, Spyros Skouras, the onetime head of Twentieth Century Fox. Confiding that he planned to sell his vast holdings to devote more time and money to medical research, Hughes asked Skouras to find a buyer. The gravel-voiced Greek was soon on the telephone to New York with real-estate promoter William Zeckendorf. Who would have the resources to handle such a transaction, Skouras wondered. Zeckendorf had but one answer: “It sounds like a Rockefeller proposition.”1

Zeckendorf, who eight years earlier had sold the Rockefellers a seventeenacre tract of land along the East River in Manhattan that became the United Nations’ site, met with Laurance Rockefeller, the family’s venture capitalist. Although skeptical about Hughes’s intentions, Rockefeller’s curiosity was greatly piqued and he flew west with Zeckendorf in anticipation of a meeting with the elusive industrialist.

After lunch in the dining room of the Beverly Hills Hotel, the two found themselves, Zeckendorf later recalled, “programmed into a script” that only a CIA agent would take seriously.2 At 1:50 P.M., following Hughes’s orders, they drove from the hotel to a nearby intersection, parked their car, and were met by a man wearing a red shirt open at the neck. “Follow me,” he instructed, walking toward an aged sedan, “something the Okies might have used on the trek west twenty years ago.”3

The jalopy took them to a “seedy section of town,” and stopped in front of a rundown dwelling that looked to the urbane Zeckendorf like a “flophouse.”4 It was patrolled by a silent cadre of Hughes’s guards, “neatly dressed, rather good-looking men, all with crew cuts.”5 Zeckendorf and Rockefeller were led to the fourth floor, then down a long hallway, where their guide paused and rapped on a door “with a distinct pattern of knocks.”6 Hughes himself opened the door. His three-day growth of beard, soiled trousers, and dirty canvas shoes were something of a surprise to the impeccably dressed visitors. Inviting Rockefeller and Zeckendorf into his clandestine conference room, Hughes, always slightly nervous around others, slouched on the edge of the couch, sometimes crossing his legs, then leaning forward to shift his weight, but never changing his “facial expression.”7 He directed a hearing aid at the visitors. Zeckendorf recited the inventory of the Hughes holdings, summing up his presentation by offering Hughes $350 million for everything. “You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Hughes answered bluntly, adding that the offer was just “not enough.”8

“What is enough?” asked Zeckendorf.

“I won’t tell you.”

“Do you want to sell?”

“Under certain circumstances.”

“What circumstances?”

“If the price is right.”

“What price?”

“The price you might offer me. If it is enough, I’ll sell.”

It was obvious to Zeckendorf, a wily negotiator himself, that Hughes was playing the “original coy mistress,” yet he persisted.

“I am offering you four hundred and fifty million; will you take it?” demanded Zeckendorf.

“No…”

“Howard, just exactly what do you want?”

“I won’t tell you.”

“Howard, take it or leave it, five hundred million.”

“I leave it.”9

Rockefeller and Zeckendorf had of course been drawn into an old Hughes game. For years, he had amused himself thusly, and eager money men invariably flocked to his door, checkbook in hand. While they got nothing for their trouble other than the rare experience of actually meeting him, Hughes obtained an up-to-date estimate of his empire’s worth. Down deep, Hughes shrank from the idea of selling any of his companies, even of diluting his control by giving stock options to top executives. “Howard,” one of his former executives said, “was a very possessive man.”10

By the mid-1950s, Hughes controlled an extraordinary empire. Hardly a corner of the world escaped his touch. There was the Hughes Tool Company in Houston, manufacturing its indispensable drill bits for oilmen around the globe. There was Hughes Aircraft Company in Culver City designing and building sophisticated electronics gear and weaponry, carving out a niche in the nation’s growing military-industrial complex. There was Hughes Productions in Hollywood, and although it had not made a movie in years, it was still signing up potential female stars, giving them expensive drama and singing lessons, and looking out for scripts that could bring about Hughes’s return to active movie production. Last, there was Trans World Airlines, whose airplanes flew to cities all over the United States and carried the American flag into dozens of capitals in Europe and Asia. The Hughes empire employed nearly fifty thousand people and generated revenues of $1.4 million a day.*

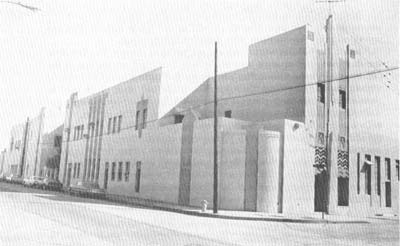

At the heart of this empire was an inconspicuous, two-story, buff-colored building at 7000 Romaine Street in Hollywood. “Romaine,” as it was known, looked more like the bakery it had been in the 1920s than the command post for one of America’s richest and most powerful men. No sign identified the building. Its exterior did nothing to set it apart from the neighborhood. More or less rectangular in shape, it fronted on Romaine Street and took up the entire block between Orange Drive and Sycamore Avenue. On the Romaine side, the facade was marked by two rows of plain windows on the first and second floors. Except for a touch of art-deco ornamentation above the doorways, Romaine Street blended perfectly with the neighboring film laboratories, motion-picture supply houses, and squat warehouses.

Romaine housed the offices of Noah Dietrich, Nadine Henley, and Hughes’s talent scouts, and served as a collecting point for various drivers, male secretaries, messengers, and assorted helpers who made up Hughes’s peculiar personal staff. Most of them were fiercely loyal young Mormons hired by Bill Gay, who functioned as Hughes’s chief of staff and also worked out of Romaine. Hughes had once kept an office at the building, but now he never came to Romaine. He worked instead from various houses and hotel suites—Marion Davies’s Ocean House in Santa Monica, the scene of glittering parties in his youth; Howard Hawks’s place in Bel Air; an imposing house on Bellagio Road across from the Bel Air Country Club; a leased house in Palm Springs; and a suite at the Bel Air Hotel. Mostly, however, he lived at the Beverly Hills Hotel, in one of the small, exquisite bungalows that have always given that hotel a special charm. The two bungalows he used most often were 19 and 19A.

Hughes had originally bought Romaine Street in 1930 to house an abortive experiment to produce color films. When the effort failed, the building remained as the site of his motion-picture operations and became a kind of catch-all West Coast headquarters. By the mid-1950s, Romaine had become central to his life in every way. It was the conduit through which he transmitted orders to each branch of his empire, and those who worked there also leased his houses and hotel suites, provided him with drivers and guards, hired his cooks and servants, paid his bills, and answered his personal letters. Centering as it did almost exclusively on Hughes, Romaine Street was tightly controlled, and access to it limited. Locks requiring both a key and a combination secured each outside door. Guards allowed no one inside without prior approval, and very few outsiders were accorded that privilege.

7000 Romaine Street, the Hughes command post in Hollywood. United Press International

Frank William (Bill) Gay, Hughes’s personal staff director at Romaine. Wide World Photos

Inside, the building was as drab and spartan as its exterior. The first floor was dark and eerie. Along a concrete hallway running from one end to the other was a series of unused film laboratories and cutting rooms and several walk-in vaults dating from the 1930s. The vaults had come to be used as repositories for Hughes’s personal memorabilia. In one air-conditioned, humidity-controlled vault were all the negatives and prints of his movies, as well as thousands of feet of outtakes. In the remaining vaults were Hughes mementos and relics—hundreds of still photographs of him; thousands of feet of newsreel film recording him at historic moments in his career; the flight jacket he had worn the day he flew the flying boat in 1947; models of airplanes used in his motion pictures; pilot logs accounting for his every minute behind the controls of an airplane; aviation trophies, plaques, and medals; some unopened Christmas presents; and even a cache of whiskey and wine dating from the estate of his father, dead more than thirty years.

The only continuing operation on the ground floor was the drivers’ room, an around-the-clock motor pool. There were usually about fifteen drivers on the payroll, most of them young Mormons, conservative dressers who drove Chevrolet sedans, which Hughes had chosen as a kind of official Romaine Street vehicle in keeping with the inconspicuous nature of his command post. The drivers picked up visitors at the airport, chauffeured starlets about town, transported Hughes’s executives to and from their houses, and ran errands for Hughes.

A flight of metal steps led to the second floor. On both sides of a long, plain hallway running the length of the building were doors opening onto the unpretentious executive offices of Dietrich, Miss Henley, Gay, and the bookkeepers, accountants, talent scouts, and functionaries Hughes had accumulated over thirty years in Southern California. Farther along the hall were a couple of conference rooms and an old screening room with its own projection booth. At the far end of the hall, in a large room overlooking Romaine Street, was the nerve center of the empire itself.

The room was known throughout the Hughes organization as “Operations.” If Romaine had a military hue, then Operations was the general staff headquarters—minus, of course, the general. It was largely the creation of Bill Gay, the military-minded chief of staff who had long since given up any idea of pursuing his academic career. Like any good soldier and bureaucrat, Gay had staffed Operations and lesser enclaves at Romaine with men loyal to him, notably fellow members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The nondrinking, nonsmoking Mormons had become so intertwined with Romaine Street that when a job opening occurred notices went up on Mormon church bulletin boards all over Los Angeles.

All decisions, however important or trivial, passed through Operations, from an authorization to spend millions of dollars to a request that a staff assistant awaiting orders from Hughes be allowed to leave his hotel room. Anyone who wanted to talk to Hughes first called Operations, OL 4-2500. The room was manned twenty-four hours a day, usually by two of Gay’s young Mormons. When a call came into Operations from a banker, a Hughes executive, a newspaper reporter, a financier, or anyone else trying to reach the industrialist, one of the polite male message clerks, called “staff men,” recorded in shorthand the caller’s name, telephone number, and the reason for the call. The message then was typed in a log—referred to as a “call sheet”—kept chronologically by minute, hour, day, and year. Technical messages were taped and transcribed. Each memorandum, no matter how insignificant, was assigned an operating number and filed at day’s end. For special people there was a special drill. For example, if Louella Parsons or Hedda Hopper, two of Hollywood’s leading gossip columnists, called, there were standing orders for the staff men:

Whenever either of these people call, we are not to hold them on the line while trying to reach HRH. Find out where they are going to be and then make every effort to locate HRH and give him the call.11

Under most circumstances, Hughes did not want to be awakened, no matter how important the message, and he did not want to be bothered “during the first two hours of being awake unless a real emergency.”12

Processing Hughes’s telephone calls was therefore a demanding task, requiring staff familiarity with a code of programmed responses. When Hughes himself called in—his telephone had a distinctive ring—the staff man read out his calls and messages.13 Hughes might dictate a series of replies, return the calls himself, refer them to others, or ignore them. In other cases, he might call and dictate a message for transmittal, either by telephone or written communication. If the message was to be relayed by telephone, Hughes would suggest the “temper” it was to be delivered in. Again, there were standing orders on how to read messages:

The message should be given slowly and clearly with natural pauses. If the insertion of a few of your own words will make it more casual and more natural sounding, don’t hesitate to do this. However, all of HRH’s points must be covered exactly as instructed.14

Written communications were handled in a variety of ways—“the form of a letter for his signature, informal note, memo, or an important communication,” known as an “IC.”15

To assist in keeping track of Hughes’s multiple interests, the staff men maintained half a dozen lists of matters pending in his different companies. The lists were assigned designations such as the “priority list,” “top priority list,” and even “very top priority list.” Items that fell into none of those categories were assigned to the “special list.”16 Another was the “alert list,” containing the names of people who had been alerted ahead of time that Hughes would call.17 To receive a call from him was generally no spur-of-the-moment affair. Usually, an aide would first call the person Hughes intended to telephone, explaining that Hughes would call at a specified time, perhaps five minutes or five hours from then. And Hughes would indeed call, although sometimes the procedure was even more complicated, as Governor LeRoy Collins of Florida once found out:

Somebody would call my office and tell them that Mr. Hughes would like to speak to me and wanted to know if I could take a call direct from him at 2:37 that afternoon… And so my secretary would check it out with me and I said, “Yes, I’ll be right here and I’ll talk to him at 2:37.” So she would call out there [Los Angeles] and give them that information. And then about 2:30, our office would get another telephone call. And they just wanted to verify the fact that I was actually in the office, and I could actually take the call. And then there’d come a call at 2:37, still from somebody else, wanting me to get on the telephone, wanting to know if I could be on the telephone in one minute, and then he’d call and I’d be there.18

To remind Hughes of important deadlines or telephone calls he should make, Operations kept “reminder lists.”19 Even these were subdivided into “master reminder list” and “special reminder list.”20 To keep track of all the lawyers, executives, staff aides, financiers, and others Hughes might want to talk to by phone at any time, Operations kept “locate books,” which gave the names, addresses, and current business and home telephone numbers of persons he called most often.21 All of his executives and lawyers were expected to leave a number with Operations where they could be reached at all times. Operations had also assigned code names to persons Hughes communicated with regularly. Jean Peters’s code name was “Major Bertrandez.”22 Another girlfriend, Yvonne Shubert, was known as “The Party.”23

Finally, there was the classification system that was used to protect the innermost workings and secrets of the Hughes empire, a system more encompassing than that used by the Defense Department. The ultimate authority for classifying Romaine Street files rested with Bill Gay or someone he designated. There were three categories. The highest, or “Secret” classification, was given to that “information and material, the security aspect of which is paramount and the disclosure of which would cause exceptionally grave damage to the interests and prestige of Mr. Hughes or his executive office.”24 Such material, marked “A” and kept in the custody of Gay, was not to be “discussed or referred to except in official meetings of the staff behind closed doors.”25

The second-highest classification, “Confidential,” was given to “information or material the disclosure of which would cause serious injury to the interests and prestige of Mr. Hughes or the executive office and would be of great advantage to competitors.”26 A typical “Confidential” communication—marked “B” and kept in the custody of section heads—was a two-page memorandum on how to arrange transportation on TWA for William Randolph Hearst, Jr., his wife and friends, or others in the Hearst newspaper chain. The memorandum, headed “Special Instruction,” directed the Hughes staff to “roll out the super red carpet all the way” on TWA for Hearst, his family and friends.27 Specifically, “the captain on each leg of their flight should come back and invite the party concerned up front and explain to them those things of interest and importance in the flying of the ship. In this respect the captain should always make certain that he explains he has received instructions from Mr. Hughes to extend every courtesy to the party concerned. The hostesses should be instructed to take very special care of them. The party concerned should be met at the airport by the top man at each point along the route and there should be transportation available at the points of origin and destination.”28

All communications that did not fall into the “Secret” or “Confidential” categories were classified “Restricted.” Such information and material, marked “C,” was read and initialed by members of his staff and then returned to a “designated file for safe keeping.”29 A six-page memorandum establishing the security classification system itself was labeled “Restricted.” In addition to spelling out the classification of printed matter, the memorandum set forth guidelines on how employees were to conduct themselves:

Do not fraternize with persons outside the office. Do not engage in long, unnecessary conversations with secretaries. Be sure that all confidential and secret material from wastepaper baskets is properly destroyed and burned. Tell your wife as little as possible.30

Classified material to be delivered from one office to another had to be placed in an envelope and sealed with wax, “the official seal of the office” imprinted in the wax.31

It was a unique, byzantine way of doing business that Hughes had contrived, but one that suited him perfectly. It insulated him from unwanted intrusions, afforded a maximum amount of freedom and flexibility, and cloaked all his activities and movements in absolute secrecy. It enabled him to manipulate his enemies and position his men, even to the point of absurdity, as when an engineer, camped out in a Seattle hotel room awaiting further orders on a pending aircraft deal, was given the following message from Hughes late one night by way of Operations: “I will call you real early in the morning. I hope that you will sleep until I call, that is I hope you will not leave a call with the switchboard girl to awaken you in preparation for my call. I will call you very early and awaken you when I call.”32 Operations also worked to Hughes’s advantage by separating the various branches of his empire from one another, allowing him control of each. As a result, one executive rarely knew what another was doing.

THE $400-MILLION ORDER

Of all the companies Hughes controlled through Romaine Street, the most cherished was Trans World Airlines, now one of the world’s largest air carriers with more than twenty thousand employees. The tool company produced the profits that made other enterprises possible, but it was TWA on which Hughes lavished his affectionate attention.

In 1939, Hughes began acquiring TWA stock, either on the open market or in exchange for capital he supplied for TWA to acquire passenger planes. By 1944, he owned 45 percent and a controlling interest, although he continued to acquire stock until he owned 78 percent of TWA’s outstanding shares. TWA had thousands of other stockholders, but Hughes ignored them and looked on TWA as his company. He handpicked most of the directors. He hired and fired presidents. He bypassed the airline’s top officers and dealt directly with the staff, whose loyalty he assured by giving them generous retainers from the tool company in addition to their regular TWA salaries. Hughes held no office in TWA, but he was its undisputed boss and dynamic influence.

Of all his properties, it was TWA where Hughes had made his greatest contributions. In 1939, he and TWA president Jack Frye conceived plans for a revolutionary passenger plane. From their rough sketches, Lockheed designed and built the nation’s first high-speed, piston-driven passenger plane, the Constellation. The sleek, long-range Connies were the most advanced airplanes of their time when they went into service in 1946. During the war, Hughes’s well-placed Washington connections had enabled him to win Civil Aeronautics Board approval, over the opposition of the agency’s own staff, for TWA to fly overseas. The decision made TWA unique among American airlines in its substantial mixture of both domestic and foreign routes. The award was made over the bitter opposition of Pan American Airways, which accused the CAB of “gross favoritism to TWA.”33

Without a doubt, then, Hughes had been instrumental in TWA’s growth. But his positive contributions were often offset by a tendency to meddle. Alone in TWA’s public-relations office in Kansas City one day, Gordon Molesworth, who had been with TWA less than a week, answered the telephone at lunch hour to find that the caller was Howard Hughes. Explaining that he was new on the job and might not be of much help, Molesworth was stunned when Hughes broke in and told him to fly to Hollywood right away. “I’ll have reservations for you, and you are to go to Ciro’s [the Hollywood nightclub] where the head waiter will give you further instructions.”34 The bewildered Molesworth flew west and presented himself at Ciro’s, where the headwaiter supplied him with a stack of magazines and ice water. At the end of the day, he was told that Hughes could not see him and that he should spend the night at a nearby hotel. The next day, Molesworth learned that Hughes had changed his mind. Molesworth’s services were not needed in Hollywood; he was to go back to Kansas City.

Such incidents became almost commonplace at TWA, especially in the public-relations department, one of Hughes’s pet divisions. They were part of Hughes’s general disregard for standard business practices. He often canceled scheduled TWA flights at the last moment and commandeered an airliner for some personal reason, such as flying a group of Hollywood friends to the East Coast or to Europe. These occurrences created havoc for TWA. Despite Hughes’s reputation as a shrewd businessman, he had little regard for TWA’s balance sheet. In the first three years after the Second World War, the airline lost a staggering $19 million. That trend was turned around in the early 1950s, but the reversal owed more to the leadership of a new TWA president, Ralph Damon, than to any efforts by Hughes.

As TWA’s proprietor, Hughes busied himself primarily with two of the airline’s continuing operations—advertising and the purchase of aircraft. As one who had long excelled in Hollywood at extravagant, first-rate promotions for second-rate movies, Hughes naturally took a special interest in extolling TWA’s virtues and in bolstering the airline’s image. In the fall of 1955, he arranged for TWA to sponsor the weekly radio broadcasts of Walter Winchell. Although the airline’s executives were apprehensive about tying TWA’s image to Winchell’s crusty broadcasts, Hughes was convinced that Winchell would be a valuable ally and insisted that the airline sponsor him. The night TWA debuted as the sponsor, Hughes telephoned Winchell at the Stork Club in New York to congratulate him on the program.35

Even more than handing out advertising plums, Hughes delighted in the job of selecting new airplanes for TWA. Of all the airline’s operations, it was the one for which he was most qualified. As the man behind the H-I racer, the Constellation, and the flying boat, Hughes was one of the few airline owners who, in Jack Frye’s words, “did have an understanding of the airplane.”36 Since taking over TWA, he had personally selected and helped design the planes that made up TWA’s worldwide fleet. Thus, it is the height of irony that aircraft selection would precipitate the next crisis of Hughes’s career.

Everybody had known it would happen, but nobody knew when until 1952, when the British, who had pioneered in jet propulsion, inaugurated service on the world’s first passenger jetliner, the de Havilland Comet One. The jet age had begun. It was only a matter of time before the world’s airlines would convert from groaning, piston-driven machines to powerful, smooth-running jets.

Hughes, who avidly followed each aviation development, was tempted to buy the De Havillands. But he was urged to pass up the opportunity by TWA’s chief engineer, Robert W. Rummel, who was convinced that American jets would eventually surpass the British.37 Hughes had long relied on Rummel’s judgment. Their association dated from 1935 when Rummel, then a nineteen-year-old engineering student, had performed the stress analysis on the landing gear and wing skin of the H-I racer in which Hughes established the land-speed record. Later, Rummel joined TWA at the same time that Hughes was buying control. Their consuming interest in airplanes drew them into a close relationship.

Rummel was an ideal confidant for Hughes, a man to talk with for hours at a time about the most minute and technical aspects of aviation and aircraft design. To review secret plans for proposed aircraft, they often drove into the hills above Los Angeles or met in heavily guarded hotel rooms in Beverly Hills. Mostly, however, they talked on the telephone. Rummel would call Operations and request that Hughes call him. Invariably, one of Bill Gay’s polite male secretaries, whom Rummel referred to privately as the “boys in the back room,” would ask him to state his business.38 Knowing Hughes’s passion for secrecy in aircraft matters, Rummel would politely refuse to do so. Hughes would always return the call, usually late at night. The tall, mild-mannered Rummel often wound up with no sleep at all.39 Hughes insisted that a special telephone be installed in Rummel’s Kansas City home so that he would not have to compete for the line with the family’s five children. Rummel’s wife Marjorie grew so tired of the incessant nocturnal chatter that she piled pillows and blankets on the phone one night to muffle the ringing. The next morning, as Rummel passed the stairwell where the phone was housed, he heard a faint ring and reached for the receiver. “Where in the hell were you last night?” Hughes drawled.40 Working for Hughes was not easy, but for Rummel there was “always excitement about trying to do something new.”41

Hughes and Rummel sometimes disagreed on what was best for TWA, but Hughes wisely followed his engineer’s advice on the de Havilland Comets. Rummel’s prediction that American jets would surpass the British soon came true. Early in 1954, Boeing began to design a long-range jet, the 707, and, in a remarkable feat of engineering and production, completed a prototype that spring. It was time to woo the major airlines, including TWA.

Hughes, who prided himself on introducing a number of innovations at TWA, from the Constellation to all-sleeper service to Europe, desperately wanted TWA to be the first airline to introduce jets in the United States.42 If, however, only Boeing were producing jets, he would not have much leverage in dictating the design features that he felt had long given TWA’s planes an individual touch. Further, any features he might suggest would also benefit TWA’s competitors. Hughes wanted, as Rummel recalled, to “do the competition one better.”43

Late in 1954, in nearby San Diego, where a chapter was closing on one of the great success stories in American commercial aviation, Hughes found a solution. At the Convair plant near San Diego Bay, production was winding down on the twin-engine, piston-driven planes of the 240, 340, and 440 series which had made Convair world-famous as a builder of medium-range aircraft. Recently absorbed by the defense conglomerate General Dynamics, Convair was eager to gain a foothold in the emerging jet field. At the suggestion of Hughes, who promised to be the company’s first customer, the company began drawing up plans for a long-range jet to rival the Boeing 707.

Convair well knew the risk of doing business with Hughes. Only four years earlier, the company had wasted plenty of time and money trying to sell Hughes a fleet of transports for TWA. Hughes had been so difficult that one Convair executive ruefully joked of negotiations “conducted by flashlight during the small hours of the night, out in the middle of the Palm Springs municipal dump.”44 At the point of contract, Hughes had backed off because TWA’s president, Ralph Damon, had committed the airline to another plane. Nevertheless, if Convair wanted a share of the jet field, Hughes appeared to be the company’s best hope.

Within a few months, Convair came up with plans for two long-range jets, one a huge plane with six engines, a forerunner of the jumbo jets, and another four-engine model similar to the 707. As the drawings developed in San Diego, they were whisked north to Hughes in Los Angeles. Fascinated by both designs, Hughes succumbed to indecision. He could not make up his mind, and his vacillation proved fatal to the project. In 1955, both Boeing and Douglas Aircraft unveiled mockups of long-range jets, the 707 and the DC-8. That race was over and Convair quickly abandoned its plans for a big jet.

The Boeing and Douglas planes would revolutionize aviation, not only technically, but also financially. With spare parts and engines, each plane cost $4.5 to $6 million. Even so, no airline could afford to stand still while its competitors converted to jets. By the fall of 1955, knowing that TWA had to commit itself to a jet fleet, Rummel recommended to Hughes that TWA order jets so that it would have them at least as soon as its competitors.45 But Hughes could never be pressured into making a decision. He stolidly refused to act. Fear mounted at TWA that the airline would be outdistanced as commercial air travel entered the jet age.

The fear became reality in October of 1955, when Pan Am ordered a fleet of 707s and DC-8s. Within weeks, United and American followed suit. Now all of Hughes’s major rivals would get preferred delivery on the new planes and would therefore introduce jet service months before TWA. As if in a trance, Hughes still did nothing.

Ralph Damon, the airline’s president, was under a severe strain, his carefully engineered recovery of TWA jeopardized by Hughes’s inaction. Damon warned in December of 1955 that unless the airline moved swiftly to acquire jets it would find itself in “splendid isolation” in the industry, hopelessly “outclassed in speed, comfort, passenger acceptability and economics.”46 A month later, Damon, bitter and frustrated, died of a heart attack.

Damon’s death and TWA’s obviously worsening competitive position finally moved Hughes to act. In February of 1956, more than three months after other major airlines had ordered jets, he began reserving Boeing 707s, eventually ordering thirty-three planes. Including spare engines and parts, the bill came to $185.9 million, and called for a $39-million down payment. The jets were to be delivered in 1959 and 1960.

Hughes, as usual, was not wholly satisfied with his main solution. In the back of his mind there lurked an old idea, dormant since the Second World War—the design and manufacture of his own planes. A new aircraft plant would require a massive capital expenditure for buildings, land, and equipment—capital which at the moment Hughes lacked. Still, the idea lingered with him, and as a projected site for the new plant, Hughes settled on Florida, a state where he had been spending time the last two years. To those closest to him, Hughes began dropping hints about the new venture.

As usual, Hughes cloaked his scheme in secrecy, advising his trusted confidant Rummel that he did not want anyone at TWA informed.47 Raymond Cook, a partner in Andrews, Kurth, Campbell & Jones in Houston, who served as an all-around troubleshooter and liaison between Hughes and TWA, dubbed the far-off scheme Project Greenland, a code name that stuck with the few who knew of it.48 When Rummel, who eagerly followed jet developments worldwide, asked Hughes what type of plane he planned to manufacture, Hughes was vague, saying only that it would be “markedly superior” to those of Boeing and Douglas.49 Privately, Hughes was stung by the realization that this exciting chapter in aviation was being written without so much as a sentence from him.

On May 10, 1956, Hughes filed an application with the CAB in Washington, seeking permission to build a fleet of jets and to sell twenty-five to TWA and more to other airlines. Special CAB permission was required because the agency’s rules prohibit an aircraft manufacturer from owning an airline. As Hughes hoped, his application set the aviation and business world buzzing. “Does Hughes have a design for a plane that will render obsolete the Douglas and Boeing jets?” asked a mystified Business Week.50 Hughes suggested as much in his vaguely worded CAB application. New developments, the application said, “make it possible to design aircraft at this time that are superior in performance, safety and economy to the commercial aircraft now being constructed, the designs for which were laid down four or five years ago.”51

As one of the seminal forces in aircraft development, Hughes was banking on his reputation to put the planemakers on edge. To some extent he succeeded. There was even speculation that he might be on the road to building a “transonic commercial airliner.”52 With the first generation of jets not yet in production, there was cause for worry by other builders if Hughes had indeed come up with an advanced design.

To those around him, Hughes appeared serious about building his “superior” jet. Options were taken on thousands of acres of land in southern Florida and extensive negotiations were carried on with Governor LeRoy Collins. Early in 1956, Collins, at Hughes’s invitation, had flown to California to talk about Hughes’s medical institute, then in the planning stage, and another unspecified project. Arriving at the Beverly Hills Hotel, the governor and his staff were treated to a pleasant dinner, during which Hughes asked many questions about Florida and potential industrial sites. The next day, after a tour of the flying boat in Long Beach, Hughes flew Collins to Palm Springs for lunch in one of his private planes. As the party flew back to Los Angeles, a weather report came over the radio proclaiming a smog-free day, and Hughes was ecstatic.

“No smog,” he shouted from the pilot’s seat, and asked Collins if he had ever seen the lights of Los Angeles at night from the ocean. The governor told him he had not.

“Well,” Hughes promised, “you’re going to see that.”53

When Hughes headed the plane out to sea, the governor became slightly uneasy and jokingly asked Hughes if he had enough fuel. Collins also was on edge because the constant chatter over the plane’s radio made him feel that the sky was full of airplanes. Only when Hughes steered the plane into an arc above the dark sea and turned back toward land did Collins relax.

“We saw the first lights twinkling and gradually it grew and grew,” Collins recalled. “It really was an exciting sort of thing to see. He was so proud of that.”54

Hughes was at his most charming for Collins. When the governor returned to Florida, he took with him a “tentative commitment” from Hughes to locate two new industries in the state, but he declined to reveal details, saying that a further announcement would come from Hughes.55 That came three months later. At the same press conference where the location of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Florida was announced, the Hughes organization also disclosed that the industrialist intended to “establish in Florida a company which will engage in the design, development and manufacture of airplanes.”56 Hughes spokesmen let it be known that they were searching for a site of up to thirty thousand acres for the aircraft plant, which they predicted would have a work force larger than Hughes Aircraft in Culver City, which then had about twenty thousand employees.

A team of assistants headed by Kay G. Glenn, an assistant to Bill Gay, was dispatched to Miami, presumably as an advance guard for the jet plant. Then, after all the negotiations and the buildup in the press and the grandiose plans, nothing ever came of Project Greenland. At the CAB, the application to build jets languished. Two years later it was withdrawn and Hughes’s Miami office was closed. What was one to make of it all? Perhaps the Florida flurry was only a ploy to extract concessions or lower prices from the jet builders. Perhaps it was to remind the world of Hughes’s reputation as an aviation pioneer. Or perhaps it was just another in a growing number of business actions that had no rational basis.

Whatever Hughes had in mind for Project Greenland, it was never intended to play any part in TWA’s immediate future. While he was toying with Project Greenland, he continued to negotiate for more jets. The Boeing orders had by no means met all of TWA’s needs. Unlike Pan Am, whose routes were mostly long-range, TWA had to cover lesser distances also. It needed another jetliner capable of operating off shorter runways and carrying fewer passengers than the 707. Ironically, again Convair seemed to offer a solution. Still eager to manufacture jets, the company came up with a preliminary design that spring of 1956 for a medium-range, four-engine jet capable of seating about eighty passengers.

When Convair passed the rough plans along to Hughes, he was privately enthusiastic and publicly cool. Like anyone else who sought to speak with Hughes, Jack Zevely, the Convair vice-president conducting the negotiations, had to call Operations in Hollywood and leave his name and number. On Monday, May 7, 1956, Hughes gave Operations meticulous orders regarding Zevely:

I do not want anybody to call Zevely unless I specifically tell them to. This is very important as I have a very big deal cooking with him and I don’t want to foul it up. Whenever we talk to him, don’t indicate that I’m super anxious to receive the call. Just tell him you’ll take the message—be sure and take it very accurately—and then let me know when I ask for my calls. I DO NOT want it volunteered to me at any time. When he calls, just be courteous—don’t fall all over yourself so he gets the impression that I’m overly anxious to receive the call—and take the message.57

Several days later, Hughes’s orders backfired. On Thursday, May 10, Zevely called Operations and asked that Hughes call him. The next day, Hughes spoke to Operations about noon, but apparently did not ask if Zevely had called. And Operations, obeying Hughes’s orders, did not volunteer the information. Zevely called back on Friday afternoon and left another message, and on Saturday when Hughes did ask Operations if Zevely had called and learned that the Convair executive had been trying to reach him for two days, he exploded, blaming Operations. Certain that he had asked Operations “several times” if Zevely had called, Hughes demanded to know “the full story on why this call was not given him.”58 It was a side of Hughes familiar to Operations. They let the anger pass. But despite the mixup, Hughes was not about to modify his order. “Do not volunteer anything,” he warned Operations again that same night, “just wait until I ask for my list and then tell me.”59

Despite these delays, Hughes and Convair worked out a contract. In June, Hughes agreed to buy thirty of the new jetliners for $126.4 million. Convair knew that doing business with Hughes would, as one official remarked, probably cost the company “a pile of jack.”60 The company was not even sure whether Hughes would pay for the planes on schedule. But at that late date in jet development, it had no choice but to gamble—Hughes was Convair’s only prime customer. And Hughes knew it. He proceeded to extract major concessions from the company, including a provision that after a $26-million down payment, he would not have to pay Convair another cent until the planes were delivered, three years later. Ordinarily, plane builders require progress payments during the manufacturing to defray their enormous capital costs. Such was Convair’s desperation that it agreed to dip into its own resources to finance Hughes’s jets. Hughes was now publicly enthusiastic about the new plane. He wanted to call it the “Golden Arrow,” but Convair eventually decided on a less glamorous name, the Convair 880—in memory, a company executive quipped, of the number of negotiating sessions conducted with Hughes.

With the Convair and Boeing orders and an additional commitment to buy $90 million worth of jet engines from the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company, Hughes had committed his tool company to the largest equipment order in aviation history—more than $400 million. Other airlines, equally short of cash at the dawn of the jet age, had turned to banks and insurance companies for long-term financing. This solution had no appeal for Hughes. Lenders usually imposed conditions, and Hughes would not tolerate any restrictions on his freedom to run TWA. In 1946, the Equitable Life Assurance Society had lent TWA $40 million to help finance a postwar fleet of Constellations, and Hughes had come to regret that loan. The Equitable periodically offered advice on managing TWA. Hughes always ignored it, but he was still rankled that any outsider would attempt to intrude. In addition, one feature of TWA’s jet program was certain to cause the opposition of lenders. Hughes planned to acquire the jets through the tool company and then lease them to TWA for a fee, rather than allowing TWA to own its planes outright, as was the case with other airlines. In this way, Hughes, always looking for accounting devices to reduce his federal taxes, could charge off the jets’ depreciation costs against the profits of the tool company.

WHERE IS THE MONEY?

The question then remained: how would Hughes pay for the jets? He had no clear-cut plan. If he had promptly arranged financing, as other airlines had done, he might have lost some authority at TWA, but he would have retained control. But Hughes could not bear to allow his power to be diluted. Instead, he delayed, hoping that by stalling he would, through his own resources, be able both to raise the capital and to retain complete control of TWA. It was a great miscalculation.

At the Hughes Tool Company in Houston, the fountainhead of Hughes’s fortune, the jet orders created a panic among company officers accustomed to disposing of cash rather than having to raise it. Soon after Hughes placed orders for TWA’s sixty-three jetliners, the tool company’s accountants prepared a “cash forecast” that sent shock waves through the company61—the tool company’s cash position would become “critical” by early the next year.62 In Los Angeles, Noah Dietrich, the executive vice-president of the tool company and Hughes’s chief financial officer, was equally alarmed. Dietrich was hardened to Hughes’s profligate spending on pet projects like the D-2, the flying boat, and various motion pictures, but all past extravagances paled beside the jet orders. Hughes had committed the tool company to a capital program that exceeded the value of the company’s assets.

Dietrich was often at odds with other tool company executives in Houston, but in 1956 they were fully united on the threat their leader’s latest caper posed to the empire. Both Dietrich and Houston began to press Hughes to arrange financing quickly so as to get the best possible terms. Within the organization, Raymond Cook began a quiet campaign aimed at encouraging Hughes to act. The Houston lawyer suggested to Dietrich that they should “attempt to get Mr. Hughes to focus on this problem so that our bargaining position will not be jeopardized.”63 To make matters worse, as Cook and Dietrich no doubt recognized, Hughes had antagonized many of the eastern money sources he would need to tap for funds. Since Ralph Damon’s death in January of that year, Hughes had shown no interest in naming a new president for TWA. The airline was limping along, mismanaged by hostile cliques, and the organizational chaos showed in the balance sheet: TWA lost $2.3 million in 1956. Such casual disregard for the airline was a disquieting note to the financiers, especially the Equitable, one of TWA’s creditors.

Within the Hughes empire, there was no way to generate enough cash to pay for the jets. Still, Hughes ignored the pleas of Dietrich and Cook to seek outside financing. In fact, he gave strict orders to Cook that no one was even to discuss financing with potential lenders, for he believed that “a rumor had already started on Wall Street that Hughes Tool Company could not finance this program.”64

Instead of thinking about money, Hughes concentrated his energies on the color scheme of the Convair 880s. Always intent on giving TWA’s aircraft a distinctive appearance, he now was considering having the 880s manufactured in gold-colored aluminum. Hughes asked Jack Zevely to determine the feasibility of gold aluminum. After contacting three aluminum companies and his own experts at Convair, Zevely reported that gold-colored planes could be produced but that no one could guarantee a consistent color match from one section of an airplane’s exterior to another.65 Reluctantly, Hughes gave up on the idea.

Late in 1956, nearly a year after Damon’s death, Hughes finally selected another TWA president, Carter L. Burgess, a highly respected thirty-nine-year-old assistant secretary of defense. Known for his hard-driving, aggressive management style, Burgess was an odd choice for Hughes, who liked to bully TWA’s presidents. Burgess was as strong-willed as Hughes; he had demonstrated that many times in his Pentagon job. When Defense Secretary Charles E. Wilson was asked how Burgess would get along with Hughes, he turned the question around: “You mean how is Hughes going to get along with Burgess?”66

Hughes wasted no time in showing his new president who was boss by embarrassing TWA’s chief engineer, Bob Rummel. Shortly before Burgess took office, Rummel had arranged a tour of the Convair plant in San Diego for Burgess to check progress on the 880s. It was to be a ceremonial affair with many Convair and TWA executives in attendance. At 9 A.M., just as Rummel was about to lead Burgess and his delegation into the plant, a messenger rushed up and informed Rummel that Romaine Street had called. Rummel was to go to his motel room and wait. Embarrassed by the untimely interruption, Rummel apologized to Burgess, who was technically his superior, and hurried off to his room. The telephone was ringing when he entered. It was Hughes. When he put down the phone, Rummel’s watch read 7 P.M.67 He had talked nonstop with Hughes for ten hours. The tour was long since over.

At the time Burgess was hired, Hughes and Dietrich were still going “round and round,” as Dietrich put it later, over the jet financing.68 By the end of 1956, tension had built up between them. Hughes’s continuing refusal to arrange financing struck Dietrich as irresponsible and potentially catastrophic. Bad feeling had also been mounting between them over an unrelated disagreement. For years, Dietrich had wanted a stock option in one of Hughes’s companies. Although he earned a salary of about $500,000 a year, Dietrich paid much of that in federal income taxes. A stock option would be taxed at a lower capital-gains rate. At sixty-seven, Dietrich had done well for himself with Hughes, but he wanted to do better.

As usual, Hughes was not receptive. He was willing to pay almost any salary, grant almost any fringe benefit, but he would not allow anyone the right to acquire stock. Like his father, he disliked partners and minority stockholders. Also, Hughes may very well have felt that he had already provided generously enough for Dietrich over the years. In addition to his substantial salary, Dietrich and his family had free use of tool company houses, cars, and credit cards, and an unlimited expense account. At the time his two sons reached driving age, Dietrich had as many as five Hughes Tool Company Cadillacs assigned to his use.69 Another source of contention was Dietrich’s investments in outside businesses, including some oil leases off Long Beach, despite the fact that Hughes liked all his executives to devote themselves exclusively to him.70

With business and financial pressures rising and relations between him and his chief lieutenant increasingly strained, Hughes stepped back and assessed the direction of his life. It was a rare moment of introspection for him. Dispiritedly, he called his boyhood friend, Dudley C. Sharp, whom he had not spoken to in years. Then an assistant secretary of the air force, Sharp was in Tucson inspecting a military plant. To the man who had once been his only friend while growing up in Houston, Hughes poured out his anxieties.

“I’ve just messed up my life,” he told Sharp. “I’m miserable.”71

Sharp, who was outgoing, optimistic, self-confident—everything Howard had never been—told Hughes there was no reason for his life to continue in the same vein, he could do something about it if he wanted to. But Hughes was in no mood for a pep talk.

“No,” he answered, a touch of finality in his voice. “I have just messed it up so much there is nothing I can do about it now.”72 It was the last time Sharp ever heard from his friend.