CHAPTER 21

WATERGATE

UNDER FIRE

ON THE early morning of Thursday, December 20, 1973, a DC-9 left London bound for the Bahamas, carrying Howard Hughes, six of his aides, and two of his doctors. Although Hughes owned or leased a fleet of aircraft maintained in readiness at airports in Great Britain and the United States, the DC-9 was not his. It belonged to Adnan M. Khashoggi, the Middle East arms merchant who had made his millions by serving as middleman between American manufacturers of military hardware, such as Lockheed and Northrop—his Lockheed commissions alone eventually exceeded $100 million—and the Arab countries, especially Saudi Arabia, where the princes were his personal friends. It was natural that Khashoggi, the flamboyant Stanford-educated son of a Saudi palace doctor, had made his private plane available for the Hughes flight. The DC-9 had become a familiar sight at McCarran Airport in Las Vegas. Khashoggi parked it at the Hughes ground facilities on frequent trips to his favorite hotel and casino, the Hughes-owned Sands. Khashoggi, highest of the high-rollers, often ran gaming tabs into seven figures and sometimes, when he lacked ready cash to cover his losses, he arranged for the money to be transferred from the Key Biscayne Bank of his friend Bebe Rebozo.1

The DC-9 arrived at Freeport on Grand Bahama Island shortly after 4 A.M., and Hughes was moved into the Xanadu Princess Hotel. Because he had refused to walk since summer, after breaking his hip, he was carried to his suite at the northeast corner of the hotel, owned by Daniel K. Ludwig, the wealthy shipping magnate who was even more secretive and more publicity-shy than Hughes. Hughes’s entourage had reserved the penthouse floor and the floor below it. His aides and doctors—some now being paid close to a hundred thousand dollars a year—had grown accustomed to life in splendid surroundings. They settled easily into suites with living rooms and dining rooms and kitchens, at an annual cost of a third of a million dollars.

It is uncertain who made the decision, and why, to transfer Hughes from London, where he had been living for a year, back to the Bahamas, which he had so recently fled by boat, hounded out by a hostile government. The efficiency of the move and the efficacy of its timing are plain however. The Bahamian government, displaying a remarkable change in attitude, welcomed Hughes by guaranteeing him complete privacy and assuring him that he would not be troubled again by government officials, or anyone else.

Earlier that month a Bahamian magistrate had issued an order effectively nullifying the Bahamas’ extradition treaty with the United States that dated back to the 1930s. The order blocked efforts by the United States attorney’s office in New York to extradite Robert L. Vesco, the fugitive financier under indictment on stock-fraud charges. Hughes would also be safe from American law-enforcement authorities—and he would need to be. One week after his arrival in Freeport, he was indicted by a federal grand jury in Las Vegas on stock-fraud charges stemming from his 1970 takeover of Air West.2 Mysteriousties were emerging between Hughes and the unfolding Watergate scandal, and government investigators were displaying interest in his business affairs. By January of 1974, the Hughes empire was being scrutinized as never before.

The nine-count Air West indictment named as defendants Chester Davis, who had become Hughes’s principal attorney; Robert Maheu; David Charnay, a Hollywood producer; and James H. Nail, a longtime Hughes employee. Two others, George Crockett, a Las Vegas businessman who had known Hughes since the 1940s, and Hank Greenspun, of the Las Vegas Sun, were named as unindicted co-conspirators.3

The indictment was largely the work of a tedious, painstaking investigation conducted by one Securities and Exchange Commission attorney, William C. Turner. It charged Hughes and his associates with engaging in a scheme “to unlawfully manipulate the market price of Air West, Inc., common stock and to instigate lawsuits against the opposing directors of Air West, Inc., to pressure the board of directors into approving Hughes’ acquisition offer,” and to “defraud and to obtain money and property by means of false and fraudulent pretenses and representations from shareholders of Air West.”4

This was not the only federal inquiry Hughes faced. The Internal Revenue Service was conducting at least two investigations. One team of tax men sought to learn whether a band of former government espionage agents, who operated under the code name of the Elissa Group, had given cash to Hughes during his TWA financing difficulties in an effort to help him maintain control of the airline. According to reports by IRS informants, these operatives had raised the funds from narcotics traffic, and the money had been channeled through “certain Swiss, British, and Portuguese bank accounts.”5 Involved in one way or another, it was said, were a Wall Street brokerage house, a Far East construction company, and a Japanese bank.

Another team of IRS agents had opened a more traditional investigation, auditing Hughes’s income-tax returns. At issue were some large cash contributions made in Hughes’s name to various political candidates beginning in 1968, including the now-famous $100,000 that Richard Danner had delivered to Bebe Rebozo. IRS agents were also trying to trace the millions funneled into Bahamian and Swiss bank accounts by John Meier. The former Hughes executive, who had supervised acquisition of the worthless mining claims and enriched himself in the process, claimed that the cash had been sent abroad on Hughes’s personal instructions.

Finally, there was the inquiry being conducted by the United States Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, better known as the Senate Watergate Committee. On January 16, 1974, Terry Lenzner, the committee’s assistant chief counsel, wrote to Chester Davis:

As you must be aware, our investigation has now reached the stage where it is necessary to question your client, Howard R. Hughes.

Accordingly, I would appreciate it if you would speak with Mr. Hughes and make arrangements so that he will be available for questioning by the Senate Select Committee.

Please be advised that every effort will be made to accommodate Mr. Hughes with regard to the time and place where the session is to be conducted.

If you have any questions with regard to the foregoing, please do not hesitate to call.

Thank you for your prompt attention to this matter.6

Did the Senate Watergate Committee seriously expect to question Hughes? It is unclear whether the letter to Chester Davis was merely a formality to complete the public record, giving the appearance that the committee was pursuing all investigative leads, or whether Senator Sam J. Ervin, Jr., and his staff were truly unaware of Howard Hughes’s physical and mental state at the time. What is clear is that certain government agencies, including the Central Intelligence Agency, were well aware of Hughes’s condition, that he had not been in control of his empire for some time, and that he was not responsible for many acts performed in his name. They also were aware that Hughes had developed an addiction to narcotics and a dependence on tranquilizers.

Hughes, of course, seldom left his bed now, and then only to be carried to the bathroom. He spent most of his waking hours watching motion pictures over and over again or just lying in bed staring blankly upward. Confused and disoriented, he had given up all hope of returning to the United States because he had been told by those around him that IRS agents were lying in wait to question and harass him.

After he was moved to the Bahamas, Hughes expressed less interest in his business affairs, less interest in the world at large, than at any other time of his life. Where he once had devoured reports or memoranda from his lawyers and executives, he now hardly looked at them. Where he once had at least scanned the weekly news magazines, he now ignored them. Where he once would go on a “television binge,” he now gave up watching TV because the reception in Freeport was so poor.7 Even the aircraft technical manuals, his beloved plans and specifications, held little interest. “It’s safe to say,” George Francom understated, “that he was not aware of current events to a great extent.”8 Among the events that swirled past him largely unrecognized was Watergate. Yet it had penetrated even his hazy consciousness that he was somehow supposed to be involved. And so, while the Senate Watergate Committee sought to establish Hughes’s role in Watergate, Hughes sought to determine the meaning of the word. He asked one of the aides to have Chester Davis prepare a Watergate report, setting out those activities that had been attributed to him.

On March 3, 1974, Davis dictated to an aide a memorandum recounting the more publicized connections. “We are involved in the Watergate affair to this extent,” Davis said:

1. E. Howard Hunt, convicted for the Watergate break-in and in the subsequent efforts of a cover-up, was employed by Bob Bennett and his firm (our current Washington representative). In addition, Bennett was maintaining liaison with the White House through Colson, who was deeply involved in the Watergate cover-up.

2. Bennett, Ralph Winte (employed by us re: security matters) and Hunt are involved in plans to burglerize [sic] Greenspun’s safe, and even though those plans were rejected and never carried out, the Government investigators see political motivation related to Watergate.

3. The political contribution by Danner to Rebozo and visits by Danner to Mitchell are claimed to be an effort for influencing Governmental decisions, including an alleged change in rulings of the Department of Justice in connection with a contemplated Dunes acquisition.

4. Payments made to Larry O’Brien and his employment has [sic] been claimed to have been a part of the possible motivation for the Watergate break-in because of White House interest in that arrangement as a possible means of embarrassing O’Brien and the Democrats.

5. The massive political contributions supposedly made by Maheu, particularly those made in cash, and as to some of which there is [sic] conflicting statements (as for example, Hubert Humphreys [sic] denial that he received $50,000 from Maheu), is part of the overall Watergate investigation dealing with the need for reform.9

While Davis’s report was a fair, if elliptical, summation of those Hughesties to Watergate that had received widespread attention, it did not fully report the true extent of the empire’s involvement in the runaway scandal that would end with the first resignation of a president in the nation’s history. In the beginning, Watergate had signified merely the break-in on June 17, 1972, at the Democratic National Committee offices and the attempted White House cover-up that followed. But by 1974 the term had taken on a much broader meaning. Now it was being applied to a wide range of unlawful and unethical political activities. For the most part, the Senate Watergate Committee, the Watergate special prosecutor’s office, and the news media focused on those misdeeds that could be traced directly to President Nixon and his staff. In the process, evidence that failed to fit the pattern was discarded. So it was with an abundance of unexplained relationships involving the Hughes empire.

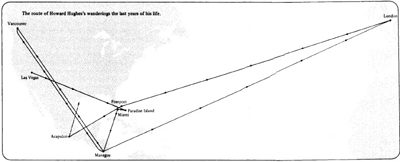

THE RESIDENCES OF HOWARD HUGHES, 1966-1976

The Desert Inn, Las Vegas, Nov. 1966 to Nov. 1970. United Press International

The Britannia Beach Hotel, Paradise Island, the Bahamas, Nov. 1970 to Feb. 1972. United Press International

The Intercontinental Managua, Managua, Nicaragua, Feb. 1972 to March 1972, and Aug. 1972 to Dec. 1972. Wide World Photos

The Bayshore Inn, Vancouver, Canada, March 1972 to Aug. 1972. United Press International

The Inn on the Park, London, Dec. 1972 to Dec. 1974. Wide World Photos

The Xanadu Princess, Freeport, the Bahamas, Dec. 1974 to Feb. 1976. Wide World Photos

The Acapulco Princess, Acapulco, Feb. 1976 to April 1976. Wide World Photos

THE HUGHES CONNECTION

From the beginning of Watergate, lurking in the background of one incident after another was Hughes’s man in Washington, Robert F. Bennett, and behind Bennett, E. Howard Hunt and Hunt’s former employer the Central Intelligence Agency. It was Bennett’s public-relations firm, Robert R. Mullen and Company, which served as a CIA front and provided employment for Hunt, the retired spy. Hunt had been working for Bennett’s firm a little more than a year when, on July 6, 1971, he was hired as a $100-a-day consultant to the White House through his friend from the Brown University Club, Charles W. Colson, special counsel to the president. Hunt was placed on Colson’s staff and given Room 338 in the Executive Office Building. He would divide his time between White House and Mullen Company duties. Pleased by Hunt’s appointment, Bennett raised his Mullen Company salary from $100 to $125 a day.

The day after Hunt went to work for Colson, Bennett told him that Clifton DeMotte, who once had worked for Bennett at the Department of Transportation and now worked in Rhode Island, claimed to have damaging information about Senator Edward M. Kennedy, who then appeared to be the likely candidate for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination. As Hunt recalled, Bennett told him “that if anybody was knowledgable of ‘dirt’ in the Kennedy background, it was Mr. DeMotte.”10

Hunt passed along the information to Colson, who suggested that Hunt interview DeMotte, but under an assumed name so as to keep secret his White House connection. Working through General Robert E. Cushman, Jr., the CIA’s deputy director, Hunt obtained from the intelligence agency a speech alteration device, a red wig, specially ground thick eyeglasses, and a Social Security card, a New York driver’s license, a birth certificate, and various club memberships, all in the name of Edward Joseph Warren. Hunt met DeMotte in a motel near the Providence, Rhode Island, airport. Most of DeMotte’s information about Kennedy drinking and Kennedy women was dated, but when DeMotte offered to look into events surrounding the drowning of Mary Jo Kopechne at Chappaquiddick, Hunt offered encouragement and expense money.

During this period Hunt also fabricated State Department cables intended to prove that President John F. Kennedy had been responsible for the overthrow and murder of South Vietnamese prime minister Ngo Dinh Diem, studied the Pentagon Papers, and planned for the burglary at the Beverly Hills office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis J. Fielding. Working now with G. Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent who was general counsel to the Committee for the Re-election of the President, Hunt obtained additional equipment from the CIA, a Tessina—a camera smaller than a package of cigarettes—another (black) wig, and a heel-lift device to create a limp, all of which was given to Liddy. Late in August, Hunt and Liddy flew to the West Coast to case Dr. Fielding’s office, where they hoped to find information damaging to Ellsberg.

To carry out the burglary, Hunt recruited Bernard L. Barker, another onetime CIA operative living in Miami, who had worked with Hunt on the Bay of Pigs invasion. Barker recruited two Cubans, Eugenio Martinez, who had been active in the anti-Castro movement and also was on a CIA retainer, and Felipe DeDiego.* Financing for the Fielding burglary was provided by Colson—$5,000 in cash, part of the political contributions from the Associated Milk Producers, which Bennett was funneling into dummy campaign committees. On September 3, Barker and the two Cubans entered Dr. Fielding’s office while Liddy stood guard outside and Hunt maintained a surveillance at the psychiatrist’s apartment. But the effort was wasted. Barker and his colleagues could find no files containing Ellsberg’s name.

As Hunt was tending to White House duties, Bennett called on him to do work for Hughes. One assignment: how much would it cost to have someone examine the garbage at the Westport, Connecticut, house of Clifford Irving. The novelist was rumored to be writing yet another book about Hughes, Bennett explained. There was, however, a far more likely explanation for the interest in Irving’s trash. Hughes executives were obsessed with the idea that arch-enemy Robert Maheu, who was suing Hughes, was somehow behind the fraudulent Hughes book. It was a belief they had little trouble persuading Hughes himself to accept. Even after Irving and his wife pleaded guilty to the hoax, Hughes executives continued to search, without success, for evidence to link Maheu and Irving.

On another occasion, Bennett asked Hunt to find out from his CIA contacts whether Maheu had ever worked for the intelligence agency, as he had often claimed. Bennett and other Hughes lieutenants were looking into many of the stories Maheu had told Hughes, hoping to trap the former chief of Nevada operations in lies that could be used against him in the raging Maheu-Hughes legal wars. As the proprietor of a CIA front, Bennett felt sure that Maheu had never had such an association. After listening to various Hughes executives recall Maheu’s tales of intelligence derring-do, Bennett was more convinced than ever. The accounts of Maheu’s work “did not make much sense.”11 Hunt confirmed Bennett’s instincts. He reported back that “there was no trace of Maheu having ever done anything for the CIA.”12 Bennett and Hunt were both wrong. The CIA had covered its tracks. Not only had Maheu been a freelance CIA agent since the 1950s, he had participated in at least one mission that paralleled Hunt’s activities. While Hunt had been working on the Bay of Pigs project, Maheu tried to arrange the assassination of Fidel Castro.

Late in January of 1972, Bennett called Hunt into his office and told him that Hank Greenspun of the Las Vegas Sun “had enough information on Muskie to blow Muskie out of the water.”13 Since the Maine senator was then the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, Hunt felt the White House would be interested, and indeed it was. Gordon Liddy “quickly returned to me in a euphoric state,” Hunt said, “indicating that the information had been well received by his superiors” and that he had been instructed “to proceed with the investigation.”14 Bennett moved with dispatch. Several days later, at another meeting in his Washington office, he introduced Hunt to Ralph Winte, a former FBI agent who was the Hughes security chief in Las Vegas. Bennett indicated that the two might have a “commonality of interest.”15 In the meeting that followed, Winte told Hunt that Greenspun probably had information in his safe at the Sun that would aid the Hughes Tool Company in its litigation with Maheu, as well as information damaging to Muskie’s candidacy. Hunt asked Winte to obtain a diagram of Greenspun’s office. He had “a team in being” that was capable of breaking into the office but would like the Hughes Tool Company to supply manpower “for lookouts, mobile surveillance and that sort of thing.”16 This seemed reasonable to Winte, who assured Hunt that he “could count on whatever assets” he might want from the Hughes organization.17 The two men laid plans to meet later on the West Coast for another strategy session.

Late on a Friday night in February of 1972, Hunt and Liddy flew to Los Angeles and checked into the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, where the Hughes Tool Company had reserved them a suite. Winte joined them the next morning, bringing with him a diagram of the Sun plant. The three agreed that rather than try to photograph the documents, they would simply clean out Greenspun’s safe and then board a waiting plane—to be provided by the Hughes Tool Company—and fly to some predetermined location, possibly in Baja California, where the contents of the safe would be divided. Hunt wanted to use the same team that had broken into Dr. Fielding’s office, but because none of the members of that team was an experienced safe man, he had asked Barker “to locate a competent locksmith in the Miami area.”18 The next planning session was to take place in Las Vegas. In the weeks that followed, however, Hunt and Liddy were drawn into other projects. Before the burglary could be carried out, the Muskie campaign floundered. The two men lost interest and abandoned the operation.

The next project promoted by Bennett and executed by Hunt was far more successful. On February 29, 1972, the columnist Jack Anderson reported that the Nixon administration had agreed to settle an antitrust lawsuit against ITT—under terms most favorable to the company—in exchange for a $400,000 pledge to help bankroll the upcoming Republican convention. Anderson based the charge on a secret memorandum written by Dita Beard, an ITT lobbyist, and addressed to William R. Merriam, an ITT vice-president in charge of the company’s Washington office. Labeled “Personal and Confidential,” the memorandum, dated June 25, 1971, and typed on ITT stationery, stated, in part:

I thought you and I had agreed very thoroughly that under no circumstances would anyone in this office discuss with anyone our participation in the Convention, including me. Other than permitting John Mitchell, Ed Reinecke, Bob Haldeman and Nixon (besides Wilson, of course) no one has known from whom that 400 thousand committment [sic] had come….

I am convinced, because of several conversations with Louie re Mitchell, that our noble committment [sic] has gone a long way toward our negotiations on the mergers eventually coming out as Hal wants them. Certainly the President has told Mitchell to see that things are worked out fairly…. If it [the convention commitment] gets too much publicity, you can believe our negotiations with Justice will wind up shot down. Mitchell is definitely helping us, but cannot let it be known.19*

Certain ITT officials issued an angry denial of Anderson’s charges, while privately feeding lobbyist Dita Beard’s memoranda and other internal documents of an embarrassing nature through a shredder. The president’s staff was equally firm in its public denial, while privately scurrying from one government office to another, impounding all letters and reports dealing with the ITT case, including one document that linked Nixon to it directly.

On March 1, Anderson published another column accusing Richard G. Kleindienst, the law-and-order deputy attorney-general awaiting Senate confirmation as attorney-general, of “an outright lie” in denying that he was in any way involved in the ITT settlement.20 The following day, at Kleindienst’s request, the Senate Judiciary Committee reopened hearings on his nomination. That same day, a distraught Dita Beard, under pressure from ITT executives and about to be subpoenaed by the Senate Judiciary Committee, boarded a plane for Denver. About an hour before arriving, Mrs. Beard became ill. She complained of feeling warm and “started turning gray and blue around the mouth.”21 A stewardess gave her a nitroglycerin tablet and a shot of whisky and administered oxygen for a minute, and she seemed to recover, leaving the plane without any assistance when it landed.

The following day, though, plagued by an unremitting chest pain, Mrs. Beard checked into the Rocky Mountain Osteopathic Hospital in Denver. Heart specialists who examined the heavyset fifty-three-year-old woman concluded that she was suffering from “severe angina pectoris and an impending coronary occlusion.”22 In the days that followed, Mrs. Beard was confined to the hospital’s coronary unit. Her few visitors were carefully screened. Senate Judiciary Committee members, FBI agents, White House aides, and newspaper reporters were barred.

Back in Washington, concern mounted within the Nixon administration over the political consequences of the ITT allegations, which the Democrats were using to good advantage as the Senate hearings droned on. On Monday, March 13, Robert Bennett received a telephone call from Bill Gay, the senior Hughes official now in control of the empire.

“Hey, you know that problem that Kleindienst is having being confirmed because of the Dita Beard memo?” Gay asked.23

“Yes,” Bennett replied.

“How would you like to know that that memo is a forgery,” Gay said.

“That is fascinating. How do you know that?” Bennett asked.

“I found out today that it is forged and nobody believes that any more than they believe us about Irving,” Gay declared.24

It was none too clear why this powerful Hughes executive was concerned about a memorandum involving an ITT political payoff or the failure of the Senate to approve Kleindienst’s nomination as attorney-general. However, since the Anderson story had been published, ITT’s private security firm had been working hard to find evidence to support the conglomerate’s denial of the columnist’s charges, and that security firm was Intertel, the same firm that handled security for Howard Hughes and his Las Vegas hotels and casinos.

Sensing the depth of Gay’s interest in the ITT case as well as the political significance of his report, Bennett passed the information along to Hunt, who in turn prepared a three-paragraph memorandum for his other employer, Charles Colson. Under the heading “ITT Imbroglio,” Hunt wrote:

According to Bill Gay, the Dita Beard letter is a forgery…. To date, the document itself has not been questioned. Since it is the crux of the matter, it should be. Any diversion or clouding of the issue at this time should be useful.25

Colson was ecstatic to have Hunt’s message. He too believed that the Dita Beard memorandum was a forgery. He asked Hunt “to interview Mrs. Beard, to find out if the memo was in fact authentic, to tell her to tell the truth, and to assure her that if she told the truth her many friends back here in Washington would not hold it against her that she had done this thing.”26

The problem was how to gain access to Mrs. Beard, who was still in the coronary care unit of Rocky Mountain Hospital in Denver. Other White House aides were consulted. It was suggested that Hunt should contact Mrs. Beard’s daughter, Edwina McLane (Lane) Beard, who was working for the Republican National Committee. On Wednesday, March 15, Hunt drove to the Washington Monument for a meeting with Lane Beard. Wearing his CIA-issued red wig and thick glasses, Hunt introduced himself as Edward J. Hamilton—another CIA alias—“a friend of friends of her mother’s, a man well placed and in a position to assist her mother out of her current situation.”27 He said that he represented the highest levels of the United States government, that he needed to speak with her mother, and that he wanted Lane to notify the hospital that he was coming. She agreed to call her mother, and Hunt flew to Denver, arriving at the hospital about 9 P.M., a box of red roses tucked under one arm.

As Mrs. Beard sat propped up in her bed, chain-smoking, surrounded by floral bouquets she had been told were bugged, Hunt, peering through his thick glasses, his head crowned with the oddly shaped red wig, began asking questions about the memorandum. She told him that the first paragraph had “a familiar ring,” but that she was reasonably sure the rest was written by someone else.28 Mrs. Beard asked what she could do. Hunt said the most useful thing “would be to have her return to Washington as soon as possible, making a brief statement, denying authorship of the memorandum—if she were able to do so in good faith—and then collapse.”29

She insisted that in her present condition this was not possible. Yet she was sure she could not have written the memorandum and wanted to know how she could prove it. Hunt quickly volunteered “that extensive laboratory tests had determined that the memorandum was not typed last summer,” when it was dated, “but had been typed this year.”30 Mrs. Beard brightened. If Hunt would provide her with the technical analysis of the document, she said, her dilemma would be solved. Hunt demurred. Finding it awkward to explain that the information had come from the Hughes organization, Hunt told her only “that it would not be appropriate for her to have such information or such a report as she would be unable to provide a plausible source for it.”31 When Mrs. Beard began to tire, Hunt left the hospital. He returned the next morning, spoke again with her briefly, then flew back to Washington to file an eightpage, single-spaced, typewritten report.

With the results of Hunt’s furtive interview in the hands of the White House staff, Bennett set to work polishing a statement for Mrs. Beard denouncing the memorandum as a hoax, while Colson readied plans for a Washington press conference. Actually, the original statement was drafted by Mrs. Beard and her attorneys, the Los Angeles law firm of White, Oberhansley & Fleming. The law firm, specially retained for the assignment, also represented Orange Radio, Inc., a company in which Bill Gay was a major stockholder.

When David W. Fleming, a partner in the firm, read the text of Mrs. Beard’s proposed statement over the telephone to Bennett, the Hughes Washington representative was not happy. “The statement does not really do anything for Mr. Kleindienst,” Bennett told Fleming, expressing the same concern for the deputy attorney-general that Gay had exhibited. “It is a lawyer’s statement. It is probably good from Dita Beard’s point of view. If you want impact on the controversy, you will have to reword it.”32 Bennett, an experienced manipulator of public opinion, rewrote the statement, laboring over phrasing designed to arouse sympathy and support for Kleindienst and undermine critics of the Nixon administration and ITT. After both Fleming and Mrs. Beard approved the rewritten version, Bennett delivered it, in accordance with arrangements worked out by Colson, to the office of Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott.

On Friday, March 17, 1972—just four days after Bill Gay called the memorandum a forgery—Mrs. Beard’s attorney released the statement in Denver while Senator Scott went on national television in Washington to read the document so meticulously prepared by Bennett. Labeling the memorandum cited by Jack Anderson as a “forgery” and a “cruel fraud,” Mrs. Beard said in her statement,

I did not prepare it and could not have since to my knowledge the assertions in it regarding the antitrust cases and former Attorney General Mitchell are untrue. I do not know who did prepare it, who forged my initial to it and how it got into Jack Anderson’s hands or why. But I do know it is not my memo and is a hoax.33

Although the Senate hearings on Kleindienst’s nomination dragged on through April and May, Bennett’s exacting statement on Mrs. Beard’s behalf marked the turning point in the controversy and defused what was becoming a serious political liability for President Nixon’s reelection bid.* A story distributed by one of the national wire services the day after the release of Mrs. Beard’s remarks noted:

The White House, angered by the length and the scope of Senate Judiciary Committee hearings concerning the International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation, is directing a major effort to discredit syndicated columnist Jack Anderson and the ITT memorandum he published which got the hearings started….

The most dramatic success so far came Friday night when Mrs. Beard, through her attorney, released a statement calling the memo a fraud.34

Few seemed to notice that Dita Beard had waited nearly three weeks to call the memorandum a forgery, a claim made only after it was suggested by the Hughes organization. A few days later, it was disclosed that the FBI, following a laboratory analysis of the memorandum, had found no evidence of a forgery, and there were, in fact, some indications it was genuine. Although the examination was inconclusive, the FBI reported that the memorandum may indeed “have been prepared around June 25, 1971,” as it was dated, and not at some later time as part of a hoax.35

As for the role of the Hughes organization in the Dita Beard episode, it remained hidden. In the style befitting a CIA-front operator, Bennett stayed inconspicuously in the background as the controversy swirled, just as he had when he became involved with Hunt in placing a spy in the campaign headquarters first of Senator Edmund S. Muskie and then of Senator George S. McGovern. Early in 1972, Bennett asked Hunt to find a job for his nephew, Robert Fletcher, at the Committee for the Re-election of the President. Hunt said that he and Liddy planned “to place agents in the offices of leading prospective Democratic nominees.”36 Fletcher rejected the offer, but he recommended a friend, Thomas J. Gregory, a senior at Brigham Young University, in Provo, Utah, who had said he was interested. A few days later Gregory received a letter from “Ed Warren,” a Hunt alias, enclosing a round-trip plane ticket to Washington. About February 20, Gregory flew to the capital and met with Hunt, who told him the job would pay $175 a week. Gregory accepted, assuring Hunt that he had no qualms about passing information from the Muskie camp. Before starting work, Gregory, a twenty-five-year-old history major, returned to Provo to arrange to get credit for off-campus study. Enrolled in an “honors program for exceptionally bright and industrious students,” he planned to receive sixteen credits for participating in the election campaign and writing a term paper about his experiences.37*

About March 1, Gregory, masquerading as a Democratic volunteer, joined the Muskie election headquarters in Washington. His assignment, according to Hunt, “was to acquire for us policy papers, working papers, advance schedules of the Muskie party, lists of contributions of contributors, bank statements.”38 Using the code name “Ruby 2,” Gregory called Hunt daily with a report. At least once a week, usually on Friday, they met at a drugstore at 17th and K Streets, N.W., where they exchanged envelopes. Gregory would give Hunt an envelope containing his findings, including summaries of discussions among key Muskie aides that he had overheard. Hunt would hand Gregory an envelope containing $175 in cash. On occasion, Bennett acted as a liaison between Hunt and his student spy, transferring “packages of materials” between them.39

When the Muskie candidacy faltered, Hunt shifted Gregory to the McGovern campaign. There, his duties were essentially the same, with one addition: “to prepare for an electronic surveillance or electronic penetration of McGovern headquarters.”40 Initially, Gregory gave Hunt a floor plan of McGovern’s office building, showing such details as the location of heating ducts and pictures in the offices of Gary Hart and Frank Mankiewicz, the senator’s two chief advisers.41 Next, Hunt introduced Gregory to James W. McCord, Jr., the onetime FBI agent and CIA operative who officially was the security coordinator for the Nixon reelection committee and the Republican National Committee, and who unofficially served as Gordon Liddy’s electronics expert. On May 15, McCord went to the McGovern headquarters, posing as an out-of-town uncle of Gregory’s. The student spy attempted to distract his fellow workers long enough to allow McCord to plant a listening device in Mankiewicz’s office. But McCord felt rushed and the mission was aborted.

When it was decided to break into the McGovern offices to install the eavesdropping equipment, Gregory was introduced to other associates of Hunt—Bernard Barker; Gordon Liddy; Frank Sturgis, born Frank A. Fiorini, an ex-marine and soldier of fortune who participated in the Bay of Pigs invasion; and Virgilio R. Gonzalez, an anti-Castro Cuban who was a locksmith in Miami. Gregory accompanied the others on a nighttime scouting mission during which Liddy, using an air pistol, shot out a streetlight behind the McGovern headquarters. At the time Hunt’s team was planning to break into the McGovern headquarters, they were also casing the Democratic National Committee offices in the Watergate, where they planned a similar bugging operation. On Thursday and Friday, May 25 and 26, two attempts to break into the Democratic National Committee offices failed. A planned break-in at the McGovern headquarters was also called off when Gregory, hiding in the building until everyone left so that he could open the door for McCord, was discovered by a watchman. On Saturday, May 27, Barker, McCord, Gonzalez, Martinez, and Sturgis finally broke into the Democratic National Committee offices. While Martinez photographed documents selected by Barker, McCord installed listening devices on the telephones of the secretary to Lawrence F. O’Brien, the national chairman of the Democratic party, and R. Spencer Oliver, the executive director of the Association of State Democratic Chairmen.

In one of those curious coincidences, both Oliver and O’Brien had Hughes connections. Oliver’s father, Robert Oliver, had been the Mullen Company’s “Washington lobbyist for Hughes Tool Company.” O’Brien, of course, had been on the Hughes payroll until shortly after the firing of Maheu, collecting about $300,000 for his work on various Washington projects for the Hughes empire.42

After the burglary, a day or two went by before McCord realized that the bug on O’Brien’s telephone was not working. But for the next two weeks, Oliver’s phone conversations were monitored and daily logs prepared. It was then decided to enter the Watergate a second time to place another bug on O’Brien’s telephone. About this time, Gregory, after more than three months of service as a political espionage agent, apparently became concerned about what he was doing. On Wednesday, June 14, he met with Bennett to talk about quitting. As Bennett recalled, Gregory told him that “they want me to bug Frank Mankiewicz’s office. They want me to help them.” Bennett said he replied, “Tommy, you cannot do that. You have to get out.”43*

Gregory had already provided an office diagram to assist in the bugging; he had worked with McCord in one unsuccessful attempt to plant a bug, and had met all the Watergate burglars. Why he was suddenly uneasy is not clear. In any event, that Friday, June 16, Gregory met with Hunt and McCord at the Roger Smith Hotel and told them he was quitting. They parted on friendly terms. Hunt told Gregory that he would pay him through the end of the month.

What happened next is history. Twelve hours after Gregory resigned, Bernard Barker, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, James McCord, and Frank Sturgis were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee offices and charged with burglary and wiretapping. Later, Hunt and Liddy were arrested for their part in the break-in. Within eight months, all seven Watergate defendants either pleaded guilty or were convicted and sentenced to prison. Within thirty months, nine members of the president’s staff, including former Attorney-General John Mitchell, either pleaded guilty or were convicted of offenses growing out of the break-in, and the president himself resigned.

THE WELL-WIRED SOURCE

Throughout these months, there was widespread speculation about the involvement of Howard Hughes in Watergate. As Newsweek observed, “Almost from the beginning of the Watergate scandal, rumors have swirled around Washington that billionaire recluse Howard Hughes was somehow linked to it.”44 In his later years, however, Hughes was often improperly credited with many activities carried out in his name, and so it was with Watergate. By now, Hughes had little notion of the world outside his bedroom. His days and nights blended as he watched old movies, chewed tranquilizers, and injected himself with narcotics procured for him through illegal prescriptions.

For Hughes, then living at the Bayshore Inn in Vancouver, the week following the Watergate break-in was typical. That Sunday, June 18, 1972, he began his day at 2:15 A.M., watching television. At 2:55 A.M. an aide showed the motion picture Captain Newman. At 4 A.M. he began eating a piece of chicken, a chore that consumed forty-five minutes. At 5 A.M. he sat in his chair and watched a movie he had seen time and again—Shanghai Express, a 1932 melodrama about the adventures of a Chinese warlord, a prostitute, and an English army officer. At 5:55 A.M. Hughes began the hour-long process of eating his dessert. At 7 A.M. he went to the bathroom. At 7:25 A.M. he returned to his chair, this time to watch The World of Suzie Wong. At 10:20 A.M. he went to the bathroom, and at 10:35 A.M. he got into bed, where he spent the next fifteen hours sleeping or resting.45

During that week, Hughes would watch sixteen different motion pictures—one of them half a dozen times. And that did not count the movies he would watch on television. On Monday, it was Unconquered, Foxfire (a Jane Russell film), The Night Digger, The World of Suzie Wong, and Shanghai Express. On Tuesday, Hughes watched only one film, The Wooden Horse, as he spent most of the day sleeping after taking seven Blue Bombers—the ten-milligram Valium tablets so named by his aides because of their blue color—within less than eight hours, a quantity twenty-eight times greater than the recommended daily dose for a patient of Hughes’s age and debilitated physical condition. On Wednesday, it was more movies—VIP, Hotel Paradisio, Pleasure Seekers, Two Weeks in Another Town, Of Love and Desire, and, once again, Shanghai Express. On Thursday came The Cincinnati Kid and, again, Shanghai Express, followed by television. On Friday, The Guns of Navarone, Two Weeks in Another Town, and Shanghai Express. On Saturday, Two Weeks in Another Town, Cafe Royal, Firecreek, and the familiar Shanghai Express. On Sunday, June 25, he spent much of the day in bed after taking six Blue Bombers at 7:20 A.M., and watched only one motion picture, Inside Daisy Clover.46

An excerpt from the log of Hughes’s daily activities in a five-day period in July of 1972. “B/R” stands for bathroom; “bbs” means Blue Bombers, the ten-milligram Valium capsules which Hughes took in abundance; “8 E” refers to eight Empirin Compound No. 4s, a prescription drug containing codeine which he also took regularly; and “Big E” was the term Hughes’s aides used for his enemas.

And on Monday, June 26, it was more Blue Bombers, more movies. At 1:15 A.M. he began the hour-and-fifteen-minute process of eating a piece of chicken and his dessert. At 2:55 A.M. he was in the bathroom. At 3:55 A.M he was sitting in his chair watching Inside Daisy Clover. At 6:20 A.M. he returned to the bathroom, and at 6:55 A.M. he was back in his chair. An aide began showing a new film, The Grasshopper, followed by Shanghai Lillie, followed by The Guns of Navarone. At 2:50 P.M., in the heart of the afternoon, Hughes gulped four Blue Bombers. Two hours and ten minutes later he took five more Blue Bombers. At 6 P.M. he fell asleep. When he awoke at 2:45 A.M. on Tuesday, he swallowed eight more Blue Bombers.47 In one twelve-hour period, Hughes had taken 170 milligrams of Valium-sixty-eight times the recommended dosage.

If one thing is certain in Hughes’s last years, it is that he personally had nothing whatsoever to do with Watergate. In fact, he had precious little to do with anything, notwithstanding his public image. But if Hughes himself had nothing to do with Watergate, the same could not be said for his empire, which was entangled in the scandal from its inception, beginning with the $100,000 in cash that Richard Danner delivered to Bebe Rebozo, and continuing through Bennett with an assortment of activities—the creation of phony campaign committees, the ITT matter, and the planned burglary of Hank Greenspun’s safe.

Perhaps the most mysterious of the Hughes empire’s ties to Watergate—one that went unnoticed throughout—was the role that Bennett played in the unraveling of the story itself, and the curious relationship that he and other Hughes lieutenants had with those authorities in charge of investigating Watergate.

From the break-in to the president’s resignation, the news media, most notably the Washington Post, played a critical part in bringing the scandal to light and then in arousing and sustaining public interest. They did so most often through the publication of fresh disclosures of wrongdoing based on information supplied by anonymous sources. The two sources most anonymous of all were Bennett and the Washington Post’s still unidentified Deep Throat. Some have even suggested that Bennett was Deep Throat, a suggestion that Bennett has vigorously denied.

A lanky, garrulous, Ichabod Crane sort, Bennett enjoyed talking with newsmen, always with the understanding that he would not be identified in their articles. In the process, he pointed reporters in certain directions, steered them away from others, dropped hints of dark misdeeds by some, and neglected to mention the dark misdeeds of others, all the while helping to shape and mold the Watergate story in newspapers and magazines, on radio and television.

Like others, Bennett read about the arrest at the Democratic National Committee offices in the Sunday, June 18,1972, Post. But unlike others, Bennett had every reason to believe that his colleague Howard Hunt, and quite probably the Committee for the Re-election of the President, were involved, even though the newspaper account made no mention of Hunt or Liddy. After all, Gregory had told him of the plan to bug Frank Mankiewicz’s office, Gregory had met all those arrested, and Bennett had brought Hunt and Ralph Winte together to discuss burglarizing Hank Greenspun’s safe. Yet Bennett made no effort to give that information to law-enforcement authorities. Instead, when he arrived at the Mullen Company on Monday morning, he went directly to Hunt’s office. According to Bennett, there was only a brief conversation.

I said, “Howard, what is going on?” He said, “I don’t want to talk about it. Don’t say anything because the girls will hear us,” meaning the girls in the secretarial pool outside his door.

I said, “What happened?” Quite obviously, his response told me that he knew what had happened. He said, “No, don’t talk about it. Everything is under control. Everything will be taken care of. Those people will say nothing. There will be no damage done to the campaign. I just don’t want to talk about it.”

… At lunch time we left the office at the same time. We rode on the elevator. He said, “I may not be back. I have to get my glasses fixed. The optometrist is out in Rockville. I will be gone a long time. I may or I may not get back to the office.” I said, “Fine.”48

When Bennett returned from lunch, two FBI agents were waiting to talk with Hunt. Bennett told them that Hunt had gone to get his glasses fixed and that he might not return. They asked Bennett to have Hunt get in touch with them. He agreed, but did not question them about the purpose of the inquiry or volunteer any information about the Watergate break-in. Later in the afternoon, Hunt returned and had a longer conversation with Bennett. Bennett recalled later:

He told me that the purpose of the team was to photograph documents. He said that this was not the first time they had been in the Democratic National Committee, that they, the ubiquitous term, and he never gave me names, but that they were so titillated by what the team had found the first time, they had sent them back for more. That is what they were doing in there, he said, photographing documents.49

Finally, Bennett said, Hunt confided in a low tone,

“The White House wants me to get out.” I don’t remember if he said the country or out of town, I think that he said out of the country. He said that they wanted him to get out of the country until all of this blows over. He said, “I am leaving now….John Dean will be in touch with you with some money for my wife. Will you please see that she gets it?”50

Bennett promised Hunt that he would pass the money along to his wife. Shortly after Hunt left, Bennett received a telephone call from Gordon Liddy.

“Where is Howard?” Liddy asked.

“I assume he is home packing,” Bennett said.

“Can you get in touch with him?” Liddy asked.

“Yes, I think I can,” Bennett said.

“[Tell him] the powers that be… are to examine the entrails one more time. They decided that he should stay put. Now, call him and tell him to stay where he is until he gets further instructions,” Liddy said.51

Bennett called Hunt and gave him Liddy’s message. “I wish that they would make up their minds,” Hunt said.52

In the days that followed, Bennett spoke with Bob Woodward, the Washington Post reporter who with his colleague Carl Bernstein was responsible for breaking the Watergate story. He also talked with reporters from the Washington Star, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and Newsweek, among others. He spoke with Assistant United States Attorney Earl J. Silbert, who was directing the Watergate grand-jury investigation, and with Hobart Taylor, Jr., a former Johnson administration official. Taylor was serving as a conduit to Edward Bennett Williams, the Washington lawyer representing the Democratic National Committee in a million-dollar civil lawsuit filed against Nixon’s reelection committee a few days after the break-in. With some, Bennett spoke more candidly than with others. For example, the information funneled to Williams, the Democrats’ lawyer, “was more extensive than the information Bennett had previously provided the grand jury.”53

What Bennett told each is uncertain, but on July 10 he gave a detailed rundown of the Watergate incident—not to law-enforcement authorities or the news media, but to Martin Lukasky, his case officer at the CIA. “We had lunch at the Marriott Hot Shoppes Cafeteria on H Street,” Bennett said later. “I briefed him on what I had told the prosecutor and what I had told the newspapers also. Then we had a general conversation about the whole situation on which, or in which, he asked me what my speculation was. I told him, that based on what I knew and felt, that I thought the chances were very good that Howard Hunt was involved in the Watergate break-in, that he would probably be charged with a crime or the crime.”54 Lukasky congratulated Bennett on his handling of the news media, indicating that “a number of people out at Langley,” the CIA headquarters, were “very pleased.”55*

In early 1973, as reporters were attempting to establish the existence of a White House cover-up of the Watergate break-in, Bennett was still manipulating Watergate reporting. A CIA memorandum noted that “Bennett was feeding stories to Bob Woodward who was ‘suitably grateful’ that he was making no attribution to Bennett; and that he was protecting Bennett and the Mullen Company.” The same memorandum suggested that “Bennett took relish in implicating Colson in Hunt’s activities in the press while protecting the Agency at the same time.”56 According to the CIA’s summaries of meetings with the Mullen Company proprietor, “Mr. Bennett rather proudly related that he is responsible for the article ‘Whispers About Colson’ in the March 5, 1973, issue of Newsweek.”57

The Newsweek story speculated about the possibility of tracing to the senior White House staff—in particular to Charles Colson—“the political espionage and sabotage operation that came to grief in last year’s Watergate bugging fiasco.” To support this speculation, the magazine stated that “well-wired Republican sources told Newsweek’s Nicholas Horrock last week that it was Colson who directed Hunt that year to work up a dossier on Senator Edward M. Kennedy, with special attention to the 1969 Chappaquiddick tragedy.” The “well-wired” unnamed source was Robert Bennett, as he acknowledged later. While it was true that Colson had told Hunt to interview Clifton DeMotte about Kennedy, Bennett had provided Hunt with DeMotte’s name and made the original suggestion.

The Newsweek article pointed out that Colson had been deeply involved in the ITT case. The magazine quoted an “insider” as saying that “Hunt relayed to Colson the theory that the centerpiece in the case—a damaging memo by ITT lobbyist Dita Beard—might have been forged. ‘Hot damn!’ Colson is said to have exclaimed; he decided subsequently that the White House couldn’t go directly to ITT with this proposition, Newsweek’s source said, but with or without his promoting, Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott made the forgery charge public.” Once again, Bennett was the unnamed source for the report, and once again Bennett neglected to mention his own role—that the original source for the forgery claim was Bill Gay, his superior at the Hughes Tool Company, and that he himself had rewritten Dita Beard’s statement denouncing the memo as a forgery and delivered it to Senator Scott.

Clearly, as the Watergate scandal neared the end of its first year, Bennett had, as the CIA so appreciatively noted, “handled” the press well. But in February of 1973 a new element was injected. The Senate created a seven-member Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities to investigate all aspects of the 1972 election campaign, and named as its chairman Senator Sam Ervin. Bennett was not concerned. An internal CIA memorandum, dated March 1, 1973, reported that “Bennett felt he could handle the Ervin Committee if the Agency could handle Hunt. Bennett even stated that he had a friend who had intervened with Ervin on the matter.”58

Bennett lived up superbly to his billing in the CIA memorandum. The Senate Watergate Committee began its hearings at 10 A.M. on May 17, 1973. Setting a proper tone for the proceedings in his opening remarks, Senator Ervin declared that “we believe that the health, if not the survival of our social structure and of our form of government requires the most candid and public investigation of all the evidence and of all the accusations that have been leveled at any persons, at whatever level, who were engaged in the 1972 campaign.”59 From that day forward, the Senate Watergate Committee granted one favor after another to Bennett, conducting all of its investigation that touched on the Hughes empire’s Washington representative in secret.

Although Bennett had been linked to half a dozen Watergate incidents—a committee lawyer acknowledged several years after the hearings that “Bennett was sort of the mystery man of the whole Watergate thing”—he was never called to testify in public before the committee.60 Instead, he was interviewed in what amounted to casual, off-the-record sessions. Those interviews were then sealed from public inspection. One Hughes executive after another was questioned in secret—when interviewed at all. Ralph Winte, the Hughes security chief who had planned with Hunt the burglary of Hank Greenspun’s safe—and who was a sometime CIA operative himself—was never questioned. Robert Maheu, involved in the distribution of hundreds of thousands of dollars in secret campaign contributions—and another CIA operative—was interviewed in private, the interview impounded. Bill Gay, who originally had volunteered that the ITT memorandum was a forgery, was interviewed in secret, and the interview sealed. Incredibly, the committee even arranged to interview in private, and grant immunity to, John Meier—the same “Dr. Meier” who had processed the worthless mining claims peddled to Hughes for millions of dollars and who later circulated bogus Hughes memoranda, some of which were initially accepted as genuine by federal courts. And so it went as more than two dozen people with information relating to ties between the Hughes empire and Watergate were questioned in private, often informally and not under oath.* The practice contrasted starkly with the spectacle in which the Senate Watergate Committee not only interrogated scores of witnesses in public, but also paraded them before television cameras.

By early 1974 only a few of the committee’s staff investigators were looking into the Hughes connection, and their efforts were confined largely to the $100,000 given to Rebozo. Herbert W. Kalmbach, the president’s lawyer, testifying in executive session before the Senate Watergate Committee, said that Bebe Rebozo told him on April 30, 1973, that “he had disbursed part of the funds to Rose Woods, to Don Nixon, to Ed Nixon and to unnamed others during the intervening years.”61 Kalmbach’s testimony contradicted Rebozo’s steadfast contention that he had placed the $100,000 in his safe-deposit box and had never touched the money until he returned it.

Interestingly, as Senate Watergate probers first pursued these leads, Hughes’s attorneys were lobbying strenuously and secretly with Justice Department officials to head off a second indictment of the industrialist. In January of 1974, a month after the Air West charges had been filed, a district court judge in Nevada dismissed the indictment as defective. The SEC and the United States attorney’s office in Las Vegas were preparing another, but highlevel Justice Department officials in Washington had promised Hughes’s lawyers that they would be given an opportunity to argue, in private, against reindictment—a courtesy not generally extended to citizens about to be charged with a federal crime. As Chester Davis, who also was named as a defendant in the original indictment, reviewed the situation for Hughes in a message dictated over the telephone on April 30, 1974, to one of the aides at the Xanadu Princess Hotel: “The Las Vegas United States Attorney is pressing another indictment…. The Justice Department in Washington has scheduled a conference on Thursday. I have to be in Washington tomorrow to organize our presentation, and hopefully forestall further action by the Las Vegas grand jury.”62

This, then, was the situation in the closing days of the spring of 1974. Hughes was safely bedded down in his Bahamian hotel, mentally confused, believing that he could not return to the United States because federal agents were waiting to take him into custody. His billion-dollar empire was under the most intense scrutiny in its history. IRS agents were systematically going through his financial records. The United States attorney’s office in Las Vegas and the SEC were seeking other Hughes records relating to the Air West acquisition. Robert Maheu, engaged in an acrimonious courtroom battle with the Hughes organization in Los Angeles, was seeking Hughes’s records to bolster his defamation lawsuit. Senate Watergate investigators, trying to pin down the Hughes-Rebozo connection, were seeking still other documents. And through it all lurked the CIA, concerned only with protecting its own interests.

Against this background there occurred a gigantic breach in the Hughes security system. In the early morning hours of Wednesday, June 5, 1974, a team of burglars broke into Romaine Street—the Hughes command post in Hollywood so often described as a fortress. They methodically went through the records and personal papers of Hughes and his empire, and carted away thousands of documents, many of them supersensitive. If the Watergate break-in was a “third-rate burglary,” the Romaine Street burglary three thousand miles away was a model of professionalism.