As the Americans had discovered, the railways’ sheer size and scope ensured that they were the first industry whose very existence was inevitably bound up with politics, politicians, governments, legislatures. Because of their size – and the absence of effective competition from other means of transport – the public interest, itself largely defined by their impact, demanded that politicians provide protection against the over-mighty railway companies.

In one of the most significant demonstrations that technical changes do not, in themselves, obliterate the differences between national cultures, but merely heighten them, the response, the patterns of investment, of construction and control varied from country to country. Every government faced similar problems in controlling these enormous, octopoidal intruders, and every government reacted differently. The railways’ existence did not impose any uniform international pattern, did not lead to any convergence of national habits.

There was, however, one fundamental divergence, between Anglo-Saxons and the ‘rest’. Almost instinctively, Britons and Americans left the shape of their railwork to market forces, to individual promoters. In Britain this relatively unregulated competition led merely to the duplication of a few lines. In the United States duplication ran riot. Even after the rationalisation of the 1890s there were twenty-one different routes between New York and Chicago, varying in length between 912 and 1376 miles, and no fewer than ninety ‘all-rail’ routes between New York and New Orleans.

By contrast the Continental Europeans adopted the orderly ‘Belgian’ pattern, by which railways were planned and regimented, because they were deemed to be of crucial national interest. The government would ensure that the promoters received a ‘normal’ rate of return during construction. In return, the state ensured that the railways’ assets would revert to public ownership at the end of a specific period.

The French went the furthest. They had planned a coherent rail system before a single mile of main-line track had been laid. As a result there is only one line between any two major towns: but because the network radiates from Paris connections between some major provincial centres – most obviously Lyons and Bordeaux – have ranged from the poor to the disgraceful.

Planning did not preclude political conflict even before any main lines had been built. By 1848 the railways represented symbols of bourgeois capitalism powerful enough for the French revolutionaries of that year to call for their nationalisation. In the event their relationship to the state was worked out only during the reign of the Emperor Napoleon III, most notably by those dedicated Saint-Simonians the Pereire brothers, whose career is covered in a note here.

Following the Crimean War, Haussmann’s enormously expensive reconstruction of Paris and a financial crisis in 1857, the French railway companies were forced to ask for financial help. The next year the system was divided into two, the 7,774 kilometres already built and the 8,578 kilometres of lines being promoted at the time. In a typically French carve-up the network was divided between six great companies. The state guaranteed the interest due on loans required to build the new network, receiving a small percentage on the revenues of the railway companies, which, effectively, became the state’s partners. As usual the capital required was underestimated and the agreement had to be revised, but it provided France with a coherent network and allowed the state to intervene if it thought rates were too high.

However, the politicians would not let well alone. By the mid-1860s the opposition was demanding the construction of socially useful but economically marginal local lines, and the railway companies, with their close links to the Emperor, became symbols of his over-centralised regime and its grasping supporters. After the 1870 war the opposition’s views prevailed and an elaborate network of smaller, local lines was built, largely for electoral reasons. This ‘Freycinet network’ was much abused at the time, although it made an enormous contribution to the unity of rural France.16 But the unfortunate Chemins de Fer de l’Ouest, which included a high proportion of branch lines running through thinly-populated rural areas, got into terrible financial trouble and had to be nationalised. The first lines to be taken over were in a poor financial and operational condition, so their nationalisation inevitably led to perfectly justified accusations of incompetence and over-manning. Nevertheless the French state gradually increased its influence until a unified network was formed under national control just before World War II.*

In Germany the individual states had originally perceived the railways as a further opportunity to assert their identity. In most cases, even when private money was involved, there seems to have been a tacit understanding that eventually the state would take over. To build the line between Cologne and Minden the government provided a guarantee that the bonds would pay 3½ per cent interest. The state would also buy a seventh of the original share capital, which was arranged so that eventually the government would own the whole lot.†

But arrangements varied. Baden modelled its system on that of Belgium. In the neighbouring state of the Pfalz, private enterprise held sway. One bemused observer17 points out that ‘both of these systems involved serious time losses and periods of indecision at the start and both slowly created a viable and profitable railroad system in the end.’ What mattered more than the system was ‘the basic determination to decisively and energetically develop the railroad through one system or another.’

To Bismarck it was essential that the railways, the most potent symbol of German unity, should be in public hands. In 1873 he insisted on the creation of a new Imperial railway agency for the newly-united German Empire, ostensibly to work towards greater uniformity in rates, in fact to promote eventual nationalisation of the few lines in Prussia not already in the state’s hands.

It took even the supposedly all-powerful Bismarck several years to create a Ministry of Public Works designed to take charge of the nationalisation process. Meanwhile his friend and banker, Gerson Bleichroder, was busy buying shares in lines he expected to be nationalised. In 1863 Bleichroder had enabled Bismarck to acquire cheap options on shares in a couple of railways, but his later investments were on a much larger scale. Fritz Stern, in Gold and Iron reckons that ‘at some points, roughly half of his liquid capital was invested in these shares.’ For Stern the investment represented ‘the clearest commitment to his own policy of nationalization, because failure or even undue delay in nationalizing could have cost him money.’ The commitment ‘sustained his intense interest in the nationalization of railroads.’ Less sympathetic commentators would simply have labelled Bismarck an ‘insider trader’.

The truly enthusiastic railway politician, like Cavour, was less interested in the relationship between them and the state than simply in getting them built. ‘His methods were eclectic,’ wrote P.M. Kalla-Bishop in Italian Railways ‘there was a state plan and a state railway system, yes; but should a private company wish to build a railway it was encouraged, and, as well, there were railways jointly owned by a company and the state. The object was to get railways built by any means.’

Even the knowledgeable Cavour assumed that politically-motivated lines – in his case those running down the Italian peninsula, specifically designed to encourage national unity – would also prove economically viable. They didn’t. Similar mistakes were made in Spain and Austria-Hungary, which both ‘constructed “star” systems, centring inappropriately upon their capital cities’.18 In Austria-Hungary like Italy, a state with more ambitions than capital, government policy was often dictated by the financial needs of the Emperor. As a result the railways changed from private ownership with state guarantees, into state ownership; then, in 1885, the state lines were leased to private companies in three networks, the Mediterranean, the Adriatic, and the Sicilian. Although these corresponded to France’s six great companies, they were far less economically successful, and nationalisation was required a mere twenty years later.

The smaller, and generally even poorer, European countries often suffered from the depredations of British promoters. Portugal had some especially unhappy experiences, while the Swedes, after experiencing the misdeeds of the unscrupulous John Sadleir,* reverted to an earlier pattern by which the Gota canal had been built as a private monopoly under strict state supervision, using government-guaranteed funds.

The pendulum swung the same way outside Europe. In Japan the Meiji Emperor was so anxious to encourage railway construction that the government’s own Railway Bureau actually surveyed and built the first lines, while the company received a guaranteed eight per cent yield on its capital. In India the first railways were built under a system which combined profit-sharing and a generous state guarantee. In 1869 an increasingly self-confident Imperial administration decided to take over the task of construction itself. The task proved too burdensome so private enterprise was allowed to enjoy the rewards from profitable lines, albeit with a smaller guarantee, while the state took on the burden of unprofitable routes. The government investment proved immensely worthwhile: by 1914 the government-owned railways were providing a fifth of India’s total government revenue, more than customs and excise combined.

In the absence of such a firm imperial hand the whole messy process of construction, operation and attempted regulation of such natural monopolies provided innumerable opportunities for politicians to sell the valuable gifts they had in their power: construction rights, permission for compulsory land purchase, government backing for their loans, preventing competition once the lines were built. Individual politicians, or fleeting pro-railway majorities in Parliament or Congress, are sometimes denounced as corrupt, but, somewhat unfairly, the railway promoters have borne most of the blame. But the moralising was, and is, largely confined to Britain, Canada and the United States. In non-Anglo-Saxon countries people have lower expectations of honesty from their politicians.

Time and again politicians everywhere proved themselves eager to be corrupted. Their underlying corruption is probably best seen during the construction of the first American transcontinental railroad. The correspondence of Collis Huntingdon, the Washington representative of the Central Pacific, which was building the Western half of the railroad, is filled with the grasping demands of politicians whom he was exceedingly anxious not to have to pay, if only because his railroad was, effectively, bankrupt at the time.

“The Railroad States of America”: how the railways bought the US Senate.

As we saw with Bismarck, contemporary attitudes were very different from those imposed by later historians. William Cobden, the apostle of Free Trade in Britain, speculated up to his neck in the shares of the Illinois Central.19 He had received the equivalent of $400,000 from grateful British manufacturers after the repeal of the Corn Laws and put most of it into the railway’s stock, then a pure speculation. When he was unable to meet calls for further capital, his friends had to rally round. In 1859 he paid a quick visit to the railway and wrote some enthusiastic letters which were widely publicised by a grateful chairman, but at the time no-one seems to have worried about this attempt by a man regarded as more of a prophet than a mere politician to salvage his personal fortune in this way.

The two protagonists in the great debates which dominated the American presidential election a year later had both speculated in the increased land values which accompanied even the rumour of a new railway. Stephen Douglas had enhanced the value of his real estate holdings in Chicago by securing a federal land grant for a railroad from that city to Mobile. His opponent, Abraham Lincoln, made a more modest return on his investment in land in Omaha, presumed to be the terminus for a projected railway west to the Pacific. By today’s standards, of course, Lincoln would have been perceived as a mere tool of the railroad lobby, for his fame as a formidable national figure sprang not from his few short years in Congress but as advocate for the Illinois Central. His biggest coup had been in showing how the destruction of his clients’ bridge across the Mississippi was due to deliberate action by ferrymen afraid of railroad competition and was not, as they had claimed, a mere accident.

Canada and the United States both felt that their very existence as coherent countries depended on the construction of transcontinental railroads, but they followed dramatically different paths. The Canadians started with a major political scandal, and triumphantly produced a splendidly honest railroad. The Americans started with high hopes and ended, a mere seven years after the passage of the act authorising the building of the railroad, with a traumatic scandal following the discovery that a construction company, the Credit Mobilier, controlled by the railroad’s promoters, was siphoning off most of the considerable profits available from building the railroad. The original Credit Mobilier was a French bank, promoted by the Pereires, designed to widen the investment possibilities open to the petit bourgeoisie. It often invested in railways, but did not otherwise resemble its American namesake, which was a conspiracy of insiders, the opposite of the French original.

At the time the ‘Big Four’* who had pledged their credit to achieve the Western section of the railroad, were more successful in escaping public odium than their Eastern counterparts. But their exploitation of the Central Pacific’s monopoly position created a radical strain in Californian politics which lasted for several generations.

Canadian politicians were as bad as their American equivalents. In the late 1840s a British businessman, Sir Edmund Hornby, crossed the Atlantic to lobby for the Grand Trunk railway and found that ‘some twenty-five members, contractors, etc were simply waiting to be squared either by promises of contracts or money, and as I had no authority to bribe they simply abstained from voting and the Bill was thrown out. Twenty-five thousand pounds would have bought the lot, but I would rather someone else had the job than myself … As usual it was a psalm-singing Protestant Dissenter who, holding seven or eight votes in the palm of his hand, volunteered to do the greasing job for a consideration.’ (Autobiography)

The inter-provincial balancing act, complete with politically-inspired payments and subsidies, continued in full flood even after the provinces had received their railroad mileage in return for adherence to the Federation. The same atmosphere hung over the first attempt at a Canadian transcontinental railroad. This ended in the disgrace of the Prime Minister, Sir John Macdonald, after smashing attacks on him for being in the hands (and the pay) of Sir Hugh Allan, the financier behind the scheme.

In the United States, General Grant was re-elected President even after the Credit Mobilier scandal, but the Canadians took their principles seriously enough to get rid of the politicians they believed to be guilty. In fact, Macdonald and his colleagues had merely been indiscreet, but a verdict of not proven did not satisfy the electorate at the time. The government’s own attempts to survey the route were no more successful. In 1880 a Royal Commission found that the work ‘was carried on as a Public Work at a sacrifice of money, time and efficiency’, largely because everyone involved had been selected because of their political allegiances, not their qualifications for the job.

Even when the Canadians found themselves with an honestly-built transcontinental railroad, the politicians would not let well alone. The CPR’s monopoly provided a splendid excuse for Sir Wilfred Laurier to promote his idea of a rival road, a dream naturally exploited by two ambitious financiers, Mackenzie and Mann.

The eventual result, the Canadian National, involved decades of political shenanigans. When Mackenzie and Mann asked for federal guarantees to build the line between Saskatoon and Calgary, the Canadian Conservative politicians ‘failed to oppose the scheme in Parliament, probably because Tory insiders were shown the route of the proposed line, a piece of information that allowed a favoured few to buy up land close to the right of way.’20 Almost inevitably the CNR was always struggling and was duly nationalised just after World War I.

Even privately-owned railways were subject to government supervision. In Britain the railways division of the British Board of Trade dates back to 1841. However it was subject not only to politicians’ whims but also to the prevailing mood of the day, and thus swung between allowing the railways to regulate their own affairs and – a mood particularly prevalent after a major crash – a determination to assert the primacy of the public interest.

The companies became adept at delaying or evading regulations. For instance the 1844 Regulating Act provided that every company had to run at least one train every day to serve all the inhabitants along its route. The train had to stop at every station, cheap fares would be available, and the train had to average at least 12 mph. These ‘Parliamentary trains’ became a long-standing joke, famous for their inconvenience, discomfort and snail-like pace.

The companies’ long-term rear-guard action against regulation was helped by the ‘railway interest’, the first major, organised, feared – and overrated – industrial lobby. Opponents alleged that the legislature was dominated by members dedicated more to the railways than to the common good.

On the face of it the critics seemed to have a case. For a generation after the great influx resulting from the railway boom of the 1840s there were never fewer than a hundred Members of Parliament with some railway connections. Nevertheless, as Geoffrey Alderman has shown,21 there was a gulf between appearance and reality. Most of the members of the ‘interest’ were directors of local railways; they were not tied to the major companies most likely to come into conflict with government. However, they were powerful enough to block much legislation for the twenty years after 1846, a period when Parliament was dominated by interest groups rather than parties. In this atmosphere political pressure for effective control or eventual nationalisation naturally evaporated. It was only after the Reform Bill of 1867, and the resulting reinforcement of party discipline, that Parliament started to act, albeit mainly on settlements of railway disputes. Earlier regulations had assumed that the railways would play fair, would reduce their charges in return for protection from competition. Of course they didn’t.

Yet even after a series of crashes in the early 1870s, even after the companies had refused to accept government-imposed brakes (partly because they could not agree on the type they would fit) the Board of Trade’s inspectors were still divided as to whether legislation was needed or whether they could rely on ‘the persuasive power of public opinion as a means of securing the adoption of safety devices’. Not surprisingly by 1884 even The Times was calling for government regulation of railways on behalf of the public.

The laissez-faire attitude was still far more powerful than it was in Continental Europe. The British companies, for instance, waged a long campaign to avoid granting automatic protection to workmen injured at work, whereas in France railway companies were bound to provide compensation even if they were in no way to blame.

Even in Britain, however, nationalisation had had its advocates from the very beginning. John Ruskin, for one, had always believed that ‘all means of public transport should be provided at public expense, by public determination where such means are needed, and the public should be its own “shareholder”.’ During the debates of the early 1840s many pioneers, including the great contractor Thomas Brassey and, more surprisingly, George Hudson, the Railway King, testified that a controlled monopoly was the best form of railway management. Competition, Hudson pointed out – and later experience in the United States proved his point – led to ruinous undercutting of rates, inevitably succeeded by agreements not to compete, what the Americans called ‘pools’. In the United States, freight railroads are still privately owned and in Britain it took until 1923 to group the companies into four giant concerns, and a further quarter of a century before Britain followed the rest of Europe and nationalised its lines.

Government ownership provided ample opportunity for direct electoral profit. The Canadians soon saw the possibilities. In the Maritime Provinces, particularly, ‘railway employees were not allowed to vote as they pleased but “were driven to the polls like sheep”.’22 Such behaviour naturally provided considerable opportunities for the opposition. ‘Government management of the Inter-colonial is monstrous. The next thing that Ottawa will try to manage will be the weather.’

Australia probably had the greediest politicians in the English-speaking world. As The Times reported in May, 1913: ‘not only were railways constructed so as to maintain a Ministry’s majority in Parliament, but ministerialists obtained contracts for supplies, and even jobbed their constituents into places and procured the adoption of their own inferior inventions on the lines.’

Not unexpectedly the battle between the companies and the ‘public interest’ was waged most fiercely in the United States, where public support had never implied public ownership but, equally, private ownership did not imply public approval. Popular opinion was first mobilised by two scandals which erupted almost as soon as the Transcontinental railroad had been completed: the Credit Mobilier and the uproar on Wall Street known as the Erie Scandal.* To the average American it seemed that railway construction was inevitably crooked, a corruption matched only by that of politicians benefiting from dealing in the stocks of railroad companies.

The railroads represented a frightening new phenomenon, an industrial monster which dictated its terms to politicians, farmers, businessmen, as well as its employees. By their arrogance, their greed, they had alienated almost everyone not directly in their pay. During the 1870s the only power strong enough to face them was John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, a trust more unified, more sophisticated, and thus more powerful than any combination of railroads. Popular opposition was only patchily effective until it was reinforced by the commercial interest, the manufacturers and merchants who also suffered from railway power.

The first effective opposition movement brought mid-Western farmers together in the famous ‘Grange movement’. Their official name was the Patrons of Husbandry, their leader, Oliver Hudson Kelley, a clerk in the Agricultural Bureau in Washington. Their organisation echoed that of the Masons, but was open to both sexes. Women were Gleaners and Shepherdesses, their menfolk Harvesters and Husbandmen. Their objective was simple, ‘protection from the intolerable wrongs now inflicted on us by the railroads’.

Their strength grew after 1873 as the effects of a major financial crisis spread to the western plains. By early 1875 the Grange’s 21,000 branches had 700,000 members concentrated in the Mid-West. They were not political activists but a single-issue pressure group, forcing politicians to pledge their opposition to the railroads, above all the crippling freight rates they charged small farmers. Within a few years several states had passed ‘Granger Laws’ prohibiting free passes, establishing state railroad commissions, ensuring that railroads did not discriminate against short-haul traffic and even laying down detailed freight rates aimed at the infamous ‘pools’ by which major companies removed any competition.

The Grangers were joined by manufacturers in the Eastern states, mostly too small to benefit from the rebates granted to the likes of Standard Oil. Indeed it was one Mr Sterne, a member of the ultra-respectable New York Board of Trade and Transportation, who complained that23 ‘railroading can never be considered a private business’. Not only did ‘the roads exercise the right of eminent domain’. More importantly ‘they had abandoned even the pretence of competition between themselves, and have cast aside the whole basis of American legislation which proceeded on the principle of competition’. The railroads had ‘outgrown all state limits’. They were licensed bandits, comparable to the ‘fermiers généraux’ of 18th-century France, able to tax the people at will. Only federal legislation would suffice to control them.* In Britain the same type of opposition from businessmen confronted by the railways’ power meant that in the last two decades of the century the normally conservative Chambers of Commerce anticipated later Socialist demands for railway nationalisation.

The sea change in attitudes was summed up by the history of the free passes granted by railways to anyone of influence. In Britain they were largely tokens of the passenger’s importance. In later life George Stephenson took a childish pleasure in flourishing his free pass and being led deferentially to a first-class compartment. The last politician to possess one was also British, the late Earl of Stockton, better known as Harold Macmillan. But this was the result, not of his political activities, but of his directorship of the Great Western Railway before World War II. In the United States they became a sort of currency, which soon became a substantial burden on the railways, who were forced to buy goodwill from all sides of every legislative body with which they came into contact. Politicians came to assume that the pass was theirs as of right, not because the railroads expected their services in return. Ignatius Donnelly, a future populist leader, actually wrote to a railroad president asking for a pass. A few years later he declared passes an abomination.

By the end of the 1870s the American railroads felt beleaguered. With astonishing confidence and political sophistication they turned to the government for protection against their own customers, becoming the leading advocates of federal regulation. In Gabriel Kolko’s words ‘the ogre of government intervention could not have appeared too formidable to men with important political connections’ (Railroads and Regulation).

The result was the Interstate Commerce Commission, the first of many regulatory agencies. Like many of its successors it became a ‘captive’ of the industry it was supposed to regulate within a few years of its establishment in 1887. ‘Well before the end of the century the ICC had reached the stage, described in the writings of political scientists dealing with regulatory commissions in later periods, in which its primary function was to minister to the needs of the industry which it was ostensibly to regulate on behalf of an amorphous, implicitly classless public interest.’24 Even when the ICC took the carriers to court, the railroads’ lawyers ensured that the cases were long-drawn-out (averaging four years) and the judges were generally unfriendly to the regulators. (The Commission won only one of the sixteen cases which reached the Supreme Court between 1887 and 1913.)

But succeeding generations of railwaymen reaped a bitter harvest. A revolt against the cosiness of the early ICC was to lead to sixty years of over-regulation which prevented the railroads from competing effectively with the internal combustion engine.

Only in France did – only in France could – railways become a doctrine. Yet they were the rallying cry of a small but dedicated group, called the Saint-Simonians after their founder, Claude Henri de Saint-Simon. They were firm believers in a creed which placed useful, productive labour above all else, and proposed to organise the political process to reflect economic realities as they saw them. To the Saint-Simonians railways were the supreme example of public industrial utility and they worshipped them accordingly.

The Saint-Simonians believed in a corporate state in which everyone’s interests would be represented for them. So they replaced ordinary democracy with an ideal parliament with three chambers: d’invention for artists, examen, effectively the legislature, and execution, corresponding to the executive branch of government. Their high-minded, albeit patronising and autocratic, political ideals were translated into practice during the 1850s and 1860s, during the reign of the Emperor Napoleon III, who found their undoubted capacities enormously useful.

The Saint-Simonian creed struck a particular chord amongst France’s increasingly important technocrats, the naturally auto-cratic, invariably intelligent, hard-working, logical and supremely well-educated graduates of France’s already-powerful Grandes Ecoles, most notably the Polytechnique. Believers included Paulin Talabot, the brilliant engineer responsible for the line from Paris to Marseilles, the influential Michel Chevalier and that visionary diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps, creator of the Suez Canal.

But even in this distinguished group the Pereires stood out.25 The brothers Emile and Isaac came from a distinguished Jewish family long-established in France – their grandfather was the first doctor to teach the deaf and make a proper study of their problems. As early as 1832 Isaac propounded the theory, which soon became part of the group’s core beliefs, that railways were more than a mere means of transport, that they were instruments of civilisation itself. France, he continued, was an isthmus providing the shortest route by land between two great seas. So routes between the North Sea and the channel to the Mediterranean, from say, Le Havre to Marseilles (naturally via Paris) should take precedence over alien routes (Hamburg to Trieste for example).

For the Saint-Simonians, indeed for all the apostles of centrally-directed progress in France, railways quickly became the outstanding symbol of modernity, of scientific progress, all directed by a small group of high-minded, almost Platonic guardians.

Inevitably their high-mindedness brought them into conflict with almost everyone. The Parisians revolted, successfully, when they planned a station, albeit quite a modest, Italianate affair, on the Place de la Madeleine in the heart of their city. And in their subsequent schemes they came up against the great James Rothschild, at first their ally (for some time Emile even had an office in the Rothschild bank), and then their enemy. For him the profit to be made from railways – or any other venture for that matter – was an end in itself. For the Pereires the railways, not just in France, but all over Europe, in Italy and Austria–Hungary in particular, were a crucial element in their vision of the triumph of the good and the efficient.

The Saint-Simonians’ influence and ideas were not confined to railways. The Pereires’ biggest innovation, indeed, was the Credit Mobilier, the first attempt in France to tap the savings of the mass of the population for productive purposes – like railways.

In the end the brothers overstretched themselves, and it was the canny, practical James Rothschild who in a sense ‘won’; though the Pereires came through their financial embarrassments with their fortune merely dented and their ideals barely scratched at all. And why not? It is largely to the Saint-Simonians that France owes its magnificent railway system.

American railroads were accused of many crimes, but none has entered more vividly into local folklore than the murder of William Goebel, the ‘dark, taciturn figure … considered by some to be the most controversial figure in modern Kentucky history’. To this day it is difficult to find anyone in Kentucky who does not believe that William Smith was responsible for his death.

Kentucky’s martyr to the power of the railroad.

Smith, president of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad from 1884 to 1921 was a ‘curmudgeon for all seasons’ in the words of Maury Klein.26 He was gruff, sardonic, a brilliant railroad manager, but also ‘a symbol of rugged individualism’ in an increasingly corporate era.

He was a man of vision, playing a crucial role in developing Birmingham, Alabama as a major steel centre. Not surprisingly he hated government regulation, which he viewed as a mere preliminary towards public ownership. His hatred focused on the progressive forces which flourished in the depression which hit Kentucky hard in the 1890s. The anti-railroad agitation resulted in a stringent regulatory bill, known as the McChord Bill, which the Republican governor duly vetoed on behalf of the L & N.

In the gubernatorial election of 1898 Goebel led the progressive forces. The L & N naturally fought hard to deny him the Democratic nomination, but succeeded only in splitting the party. In the subsequent election the Republican William S. Taylor gained a narrow victory. The Democrat-controlled legislature immediately cried foul, the L & N carried car-loads of rugged mountaineers ‘equipped with rifles, pistols and an ample supply of corn liquor’ into Frankfurt, the state capital, to support Goebel.

The inevitable explosion came when Goebel was shot, removed to a hotel, where he was sworn in as governor, and, three days later, died from his wounds. His lieutenant-governor was immediately sworn in as his successor. Eventually the Democrats gained the day and the McChord Bill was passed. Although three men, including the Republican Secretary of State, were tried and convicted of Goebel’s murder, no one knows who fired the fatal shot, or whether Smith ordered it.

Politicians found railways convenient from the very outset. In the early 1830s the record for the journey from Manchester to Liverpool was held by an election special which hurled voters between the two cities in a single hour, at a time when the journey normally took two and a half hours.

Naturally politicians employed railways as a means of getting their messages through to more, and more scattered, audiences than ever before. In the United States the idea became a symbol of the whole democratic process, the mobile equivalent of the ‘town meeting’ which had been at the very base of American democracy in New England. But inevitably the politicians going on what became known as ‘whistle-stop tours’ (stopping at even the most insignificant stops) were the outsiders. Until well into the twentieth century, incumbent presidents seeking re-election did not deign to tour the country.

The precedent was set by Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, with what became known as a ‘Swing Around the Circle of the Union’, a tour which took in all the major cities of the North between Washington, New York, Detroit and Chicago in an attempt to preach his gospel of reconciliation after the Civil War. Johnson was heckled by increasingly well-organised crowds of Radicals and his ideas were doomed to failure. Nevertheless the journey set a fashion for those bold enough to take their cause to the country by train which was to last for eighty years.

One of the most famous ‘outsiders’ to specialise in such tours was the silver-tongued William Jennings Bryan, an orator so in love with the sound of his own voice that his special train was always late. According to James Marshall,27 the trainmaster ‘conceived the idea of getting the candidate onto the back platform and letting him talk from there. Then at starting time, Mr Lake [the trainmaster] simply high-balled the engineer and they pulled out, Mr Bryan still talking to the receding crowd … sometimes he was talking when they pulled into the next town’.

President Truman’s ‘give ’em hell’ campaign in the 1948 presidential election was the last burst of populism organised round the country’s railroad system. Since then presidential hopefuls have often posed on the cabooses of trains – as late as 1988 the Reverend Jesse Jackson was photographed on one in the course of the New Hampshire primary – but these have been token appearances, attempts to associate the candidate with the earlier populism of the whistle stop. Yet the symbolism remained powerful even though the private jet had become the effective campaign vehicle.

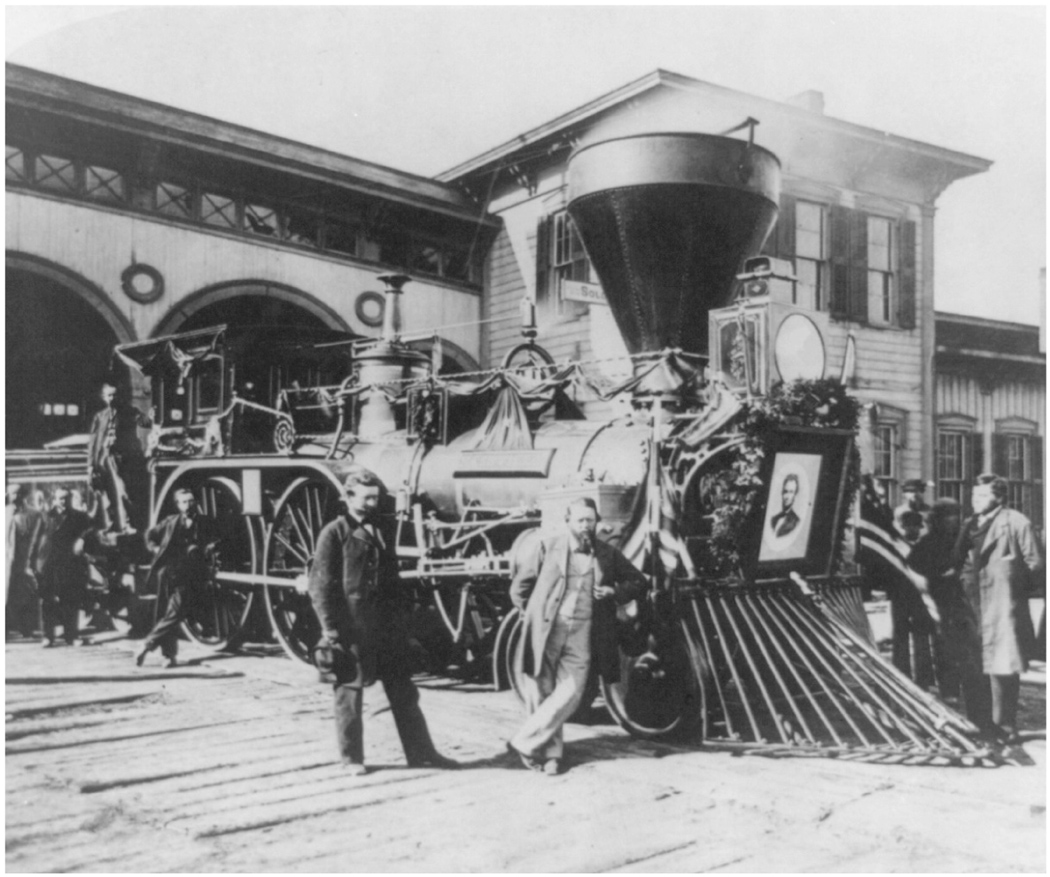

Abe Lincoln’s funeral train, one of several used to carry Lincoln’s body from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Ill.

Trains retained one power: to arouse emotions at the demise of well-loved statesmen. In 1865 the crowds had gathered in their hundreds of thousands to watch President Lincoln’s body being transported from Washington to his final resting-place, Springfield, Illinois. A hundred years later crowds just as large, just as affected, swarmed by the tracks to mourn the passage of the funeral train carrying Robert Kennedy’s body. As Theodore White put it28 ‘one finally understood aboard the train the purpose of an Irish wake: to make a man come alive again in the affection and memory of his friends.’

* The Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer was formed as a private company, albeit one in which the state retained the majority of the shares.

† The railway was so valuable that its gradual sale enabled Bismarck to finance the Prussian war against Austria in 1866.

* The model for Merdle in Dickens’s Little Dorrit.

* Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, Collis Huntingdon and Charles Crocker, names attached to most of California’s most venerable and reputable institutions, from banks and hotels to universities and museums.

* See page 109–10.

* For a striking instance when a railroad allegedly took extreme measures against a determined opponent, see the note at the end of this chapter, ‘Was the Curmudgeon also a Murderer?’