Introduction

The World Bank has defined structural adjustment lending as ‘non-project lending to support programmes of policy and institutional change necessary to modify the structure of the economy so that it can maintain both its growth rate and the viability of its balance of payments in the medium term’ (Stern1993). In 1988, the World Bank argued that the structural adjustment lending programme had been initiated as a response to fundamental disequilibrium resulting from domestic policy weakness and the effects of the second oil shock (World Bank 1988). However, it has been argued that attempts by the BWIs to promote economic recovery and economic growth have been flawed by their inappropriate approach and the mix of policies required under structural adjust-ment and conditionality. As such, external resources required to close balance-of-payments gaps and increase financial inflows have not in general increased as a result of the policy requirements of the World Bank and IMF (cf. Griesgraber and Gunter 1996b). This chapter examines these broad economic impacts of SAPs and tracks through the major policy areas identified in the previous chapter. We do this by examining aggregate trends across regions in the first section while in the second we disaggregate by policy reform area.

General trends in economic performance

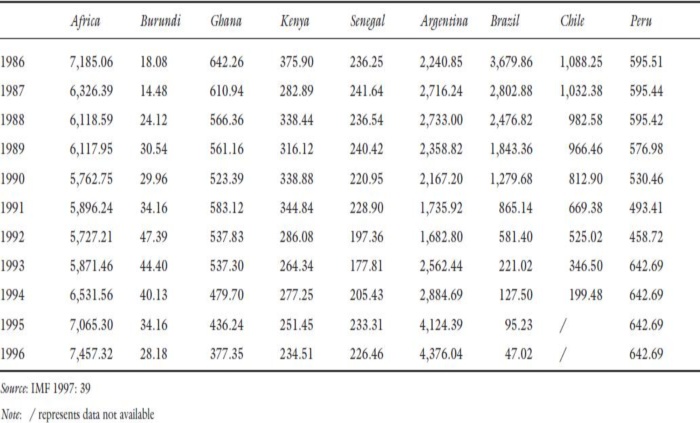

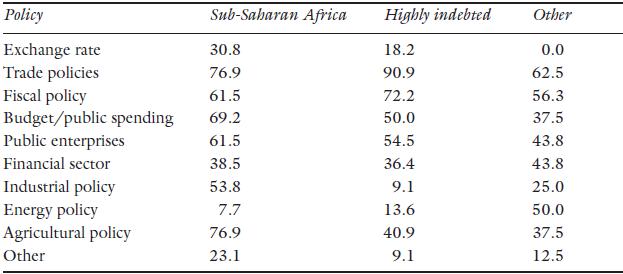

This section provides an analysis of the performance of a sample of key adjusting countries in Africa and Latin America. Table 3.1 illustrates those policy areas where conditions have been most often applied in terms of structural adjust-ment loans and Greenaway and Morrissey (1993) point out that exchange rate policy has a relatively low subjection to conditionality here because this is the policy variable most associated with the IMF, and as many countries in receipt of structural adjustment lending are also recipients of stabilisation loans from the IMF, the exchange rate is targeted there.

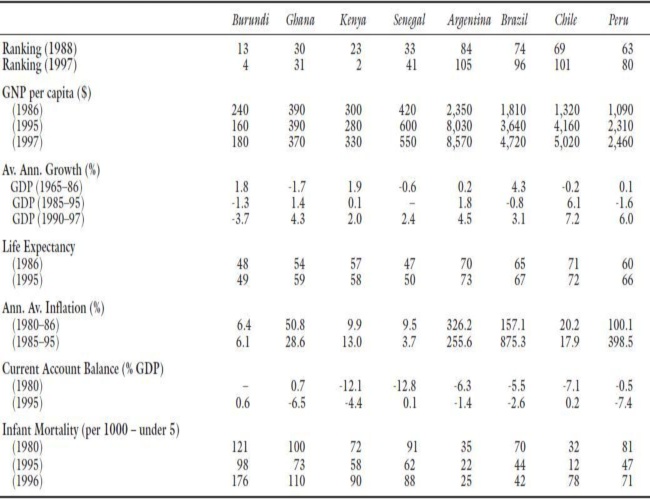

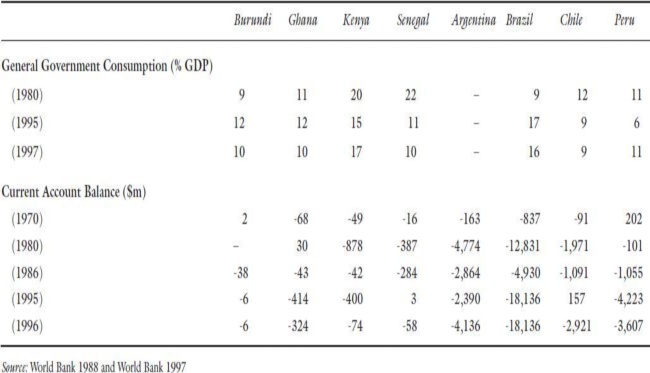

From tables 3.2 and 3.3 it is evident that the performance of these economies has varied widely during the period of structural adjustment and conditionality. The Latin American economies appear to have fared much better in terms of the internal indicators with large increases in per capita income, particularly in Argentina and Chile, and reductions in infant mortality. However, these economies continue to suffer from high levels of inflation and with current account deficits, with the exception of Chile. They also remain highly indebted despite the reforms that have been undertaken. The African economies here have not progressed over the period and indeed it would appear that Burundi and Kenya have actually regressed, with Ghana standing still. Senegal has increased its per capita GDP, but not to any great extent. It would appear that those economies of Latin America that required external adjustment have not had these problems addressed and continue, in the main, to have balance-of-payments problems with highly inflationary economies and the African economies have neither internal nor external equilibrium, but both Latin America and Africa are highly indebted. This would suggest that for the most part the neo-classical solutions have not worked and indeed in many cases have made the situation worse.

Table 3.1 The conditionality content of structural adjustment loans (percentage of total loans with conditions in various policy areas)

Source: Greenaway and Morrissey 1993: 244

Policy reforms and outcomes

This section disaggregates the impact of SAPs by those policy areas outlined in chapter 2. We do this through selected case studies since this permits attention to the unique circumstances operating in each country and, therefore, the ways in which relatively standardised adjustment packages unravelled in different ways.

Fiscal policy and management

The use of fiscal policy in the neo-classical paradigm suggests that a system of taxation and subsidy is inefficient, and as such the approach preferred in a structural adjustment package is that of lowering taxes to increase individual incentives and of eliminating subsidies to raise efficiency through greater competition. In addition, it is argued that state investment programmes, funded out of taxation, are a highly inefficient use of scarce resources.

For example, Burundi faced unstable coffee prices which had a direct effect as coffee is of major importance to government revenue. Given a high level of state spending on higher education and hospitals and a high degree of military expenditure, reductions in revenue from coffee had a large impact on the state budget. In addition, the government in Burundi was giving direct and indirect subsidies to the public enterprises, which compounded the problems of ineffi-ciency in the investments in public projects.

The reform package consisted of three main public expenditure policies. First, the government agreed to reduce the size of the public investment programme and to produce an investment plan that was compatible with the availability of resources. Second, budgetary reform involving the introduction of a unified budget system which would identify and separate current revenue, current expenditure and capital expenditure and the preparation of a three-year rolling programme for public expenditure. Third, the strengthening of the agencies responsible for preparation of the annual budget at the ministry of finance and to establish a system for the monitoring of project implementation.

In the early 1990s, under phase III of the reform programme, the govern-ment was attempting to increase the funding of investment-related recurrent costs and to promote quality-based services, thus improving the composition of public expenditure. The public investment programme has scaled down the size of projects and promoted more realistic sectoral objectives that take account of resource and debt service constraints. Approximately 75 per cent of capital expenditure in the public sector expenditure programmes goes to the economic infrastructure, of which 30 per cent goes to roads, 30–40 per cent to the rural sector, whereas social infrastructure receives 10–13 per cent, primarily for health and education (Englebert and Hoffman 1996). However, this represents a substantial problem for several sectors: agriculture accounts for 60 per cent of the underfinancing with large items being neglected, including the maintenance of livestock, infrastructure, forestry and irrigation facilities. Shortfalls in the health sector represent approximately 14 per cent of total underfinancing and include medicines, equipment and vehicles. The underfinancing of road mainte-nance represents 16 per cent and the remaining 10 per cent is spread across other sectors (Englebert and Hoffman 1996). The previously relatively large public investment projects in the productive sectors of the economy have gradually shifted towards smaller investments that are targeted primarily at improving the quality of the social services. Government expenditures were insufficiently restructured however, which has tended to reveal a weak commitment to the reduction of public expenditure. The wage bill has been excessive in relation to expenditures on goods and services and the accumulation of large counterpart funds by the public sector has tended to undermine the principal goal of the programme, to reduce the role of the state in the economy.

It has been argued that fiscal policy in Kenya has been the single most critical variable in macro-economic management, and yet, at the heart of its fiscal problem is the inability to control expenditures and not its inability to generate sufficient revenue. The tax to GDP ratio hovered around 22–23 per cent for most of the 1980s, whilst the ratio of recurrent expenditures increased signifi-cantly. The inability to control expenditure was due in part to the structure of expenditure and in part to a general lack of discipline in expenditure allocation and execution. There has been a downward inflexibility characterised by the civil service wage bill that was 6 per cent of GDP during the 1980s. There was also upward pressure from the growing demands of teachers’ salaries and interest payments, particularly on the domestic debt of the government and the parastatals. The government was also thwarted by the absence of clear expendi-ture priorities and the political will to control expenditure. One result was that expenditure ceilings set by the treasury were repeatedly violated. There was also a proliferation of government functions with a sharp increase in the number of departments and divisions, making co-ordination cumbersome. In 1985 the government initiated a budget rationalisation programme designed to introduce better planning and discipline into resource programming and expenditure, seeking greater balance between developmental and current spending, and between wage and non-wage spending. The budget rationalisation programme also sought to target scarce managerial and financial resources on a smaller number of critical ‘core’ investment projects. However, this did not improve resource allocation, and between 1981 and 1986, non-wage operations and maintenance expenditures fell from 36 per cent to 26 per cent of total recurrent expenditure and, after a further budget rationalisation programme, they declined further to 22 per cent (Swamy 1996). The government increasingly relied on the development budget, particularly the donor-financed component, to finance recurrent expenditures. Rather than raise additional revenue relative to GDP, the tax reform programme sought to primarily simplify the tax struc-ture. It lowered the high tax rates that may encourage evasion and discourage investment, strengthened tax administration and increased the use of user charges, particularly in health and education. It focused on import tax and company taxation, with the government reducing company income tax from 52 per cent in 1982 to 37.5 per cent in 1992 and reducing the average unweighted import tariff (Swamy 1996). Tax coverage was also broadened to cover more products and services. In 1990, the government sought to improve tax collection by introducing the tax modernisation programme, which included attempts to computerise the tax system.

In Latin America in the 1980s, most governments implemented policies designed to eliminate their fiscal deficits. By the early 1990s, these large fiscal deficits had disappeared in the major economies and some were running surpluses. In 1976, Argentina entered into a five-year agreement with the IMF which entailed a full-scale neo-classical policy conditionality. The programme consisted of the liberalisation of external trade and capital markets, the devaluation of the nominal exchange rate, the elimination of domestic subsidies, the privatisation of public enterprises and the raising of public sector prices and domestic interest rates. This attempt to stabilise and to adjust the economy in the policy frame-work of freeing up markets and allowing individuals to initiate economic decisions appeared, initially, to be successful in terms of the main economic indicators. Real output grew by more than 12 per cent between 1977 and1981, the rate of inflation fell from 443.2 per cent in 1976 to below 150 per cent on average for 1977–81 and a current account surplus was generated until the final quarter of 1979. However, Argentina entered into a steep recession in1981–82, as external debt increased from $6 billion in 1976 to $14.4 billion in1981, accompanied by capital flight. In addition, the current account deficit reached 3.8 per cent of GDP in 1981. The outcome was a reversal of the real output growth generated in the previous four years. A phase of gradual adjust-ment began in 1983 as the government signed a stand-by agreement with the IMF under similar conditions to the programme of 1976. The outcome of this was a decline in real wages of 32.5 per cent, an increase in the rate of inflation to over 600 per cent and a reduction in output of 4.4 per cent, all by 1985 (Ruccio 1991).

For Argentina, the decade of the 1980s was a period of stagnation and finan-cial crisis in the public sector. The fiscal deficit/M3 ratio1 was 26.2 per cent prior to the crisis and in the years that followed it often exceeded 100 per cent. With a low demand for government bonds and the rationing of foreign credit, the government was forced to monetise a large part of the deficit with a huge increase in inflation tax. However, this led to a fall in the demand for money, contributing to a worsening financial position. Attempts were made to raise government revenues through increases in the overall tax burden, but all failed. Thus, fiscal adjustment fell on public expenditures and in particular on public investment. The public investment GDP ratio fell from 6.5 per cent in 1980 to 3.1 per cent in 1990 (Chisari et al. 1996). The knock-on effect of this was a decline in private sector expenditure on capital. Structural reforms since 1990 have included a law regulating the activities of the central bank which prohib-ited the monetary financing of the fiscal deficit and a large privatisation programme which aided considerably the reduction in the deficit. In addition, the tax burden increased by approximately 5 per cent between 1990 and 1995. This was achieved through a broadening of the tax base and improvements in administration. The fiscal deficit/M3 ratio fell from 136.8 per cent in 1990 to 2.7 per cent in 1992 (Chisari et al. 1996). However, public investment has remained very low indeed and the privatisation programme has had a major role in closing the fiscal gap.

Monetary policy

Neo-classical theory suggests that monetary policy should be used to address the problem of inflation through control of the monetary base and involves reform of the control that is exercised by the central bank over all financial intermedi-aries. The idea is basically that of the so-called ‘monetarists’, whereby reductions in the rate of growth of the money supply result in reductions in the rate of growth of the price level. This theory was adopted by many developed economies in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but was quickly abandoned as a major economic strategy due to the effects of reductions in aggregate demand and the subsequent appearance of mass unemployment. However, it has remained as an important policy instrument of structural adjustment programmes.

In Ghana, monetary policy appeared to become more manageable with improved fiscal discipline. As the economic recovery programme was imple-mented, the monetary base began to stabilise and the rate of inflation fell slightly. However, the initial success of the stabilisation programme complicated monetary management in new ways. External financial support rose dramati-cally, allowing a replenishment of depleted foreign exchange reserves. Although the build-up of reserves was partly a policy choice, it was also necessitated by the government’s financing of local expenditures. For example, in 1988 and1989, domestic spending in excess of domestic revenue was financed by the conversion of foreign aid. Thus, foreign assets held by the Bank of Ghana became an important source of monetary growth, replacing the fiscal deficits of a few years earlier. However, since 1989, domestic credit policy has been used aggressively to offset the growth of foreign assets. Initially the policy generated a small surplus which was used to repay the government’s debt to the Bank of Ghana to offset monetary growth and in subsequent years repayments were increased and domestic credit extended by the Bank of Ghana was reduced. One outcome of this was that inflation fell to single figures by the end of 1991.

Monetary reform in Senegal was threefold: first, managing overall demand to correct external imbalances; second, gaining a competitive advantage by keeping the level of inflation below that of its major trading partners; and third, strength-ening the management of liquidity and the supervision of the banks. The government addressed the first two of these objectives primarily by pursuing restrictive credit policies and it implemented a more comprehensive set of measures in the banking sector, including the introduction of market-determined interest rates. In September 1989 Senegal, and other members of the West African Monetary Union, adopted a comprehensive reform of mone-tary policy instruments that replaced the administrative controls over money and credit with an indirect and market-oriented system of monetary instruments. In particular, the preferential rediscount rate was abolished and the central banks’ rediscount rate was set above money market rates, whilst banks were given more flexibility in determining their rates on deposits and loans. In addition, rigorous controls were placed on state guarantees for borrowing by public and private enterprises with the system of sectoral credit being eliminated. Restrictive monetary policy has helped Senegal’s external account but has severely con-strained domestic credit. From 1986 to 1991 credit to the non-government sector increased by an average of only 0.7 per cent per annum and in real terms it declined substantially. The money supply followed a similar trend, although the decline was less severe. One result of monetary reform has been the liberali-sation of the interest rate structure. By eliminating the preferential discount rate, which formerly applied to the agricultural sector, the export sector and residen-tial construction, the government has kept lending rates for prime borrowers at16–18 per cent while maintaining official inflation at less than 3 per cent. Thus, the measures have kept inflation low, curtailed overall domestic demand and restricted government intervention in the allocation of credit. Yet this has not created a foundation for sustainable growth.

The average rate of inflation in Latin America increased 26 times between1981 and 1990, with those most affected being Argentina and Peru, who suffered hyper-inflation, but also Uruguay and Mexico with high levels of infla-tion. By 1993 the rate of inflation had been reduced, but was still relatively high in Uruguay and Peru (Mesa-Lago 1997). In Brazil, the rate of inflation fell from 228 per cent in 1985 to 58 per cent in 1986, but was at nearly 1,000 per cent in 1988 (Green 1995).

The Economic Solidarity Pact in Mexico, introduced in December 1987, was designed to quickly reduce the rate of inflation and relied on multiple economic instruments, including a fixed exchange rate and an incomes policy. In addition, domestic interest rates were set above international rates and a restrictive mone-tary policy was adopted. The money supply contracted between 1988 and 1989 as real interest rates rose sharply. However, the rate of inflation continued to rise faster than nominal wages (Nazmi 1997).

Trade policy

As we observed in chapter 2, neo-classical trade policy involves the elimination of restrictions on trade, including tariff and non-tariff barriers, to achieve the optimum level of production and consumption. In addition, an outward, rather than inward, orientation of production is required under structural adjustment to achieve greater competition to enable increases in the efficiency of local output.

A study of the protection system in Burundi prior to adjustment identified a wide spread in customs tariffs (68 to 336 per cent), quantitative restrictions (quotas for most products and a ban on imports that competed with locally manufactured products), import regulations, foreign exchange controls and compulsory advance deposits with the central bank. Imports were also subjected to three different kinds of tax: customs duties, a statistics tax and a transactions tax. In addition, all commercial imports required licences. The reforms were sequenced, seeking to liberalise the trade regime. Import licences were to be granted automatically for most products, with the exception of cotton textiles, glass and pharmaceutical products. Regulations on importers were to be eased to facilitate competition. A simplified tariff structure was also proposed to reduce the number of duties from three to two, the number of duty rates from fifty-seven to five and the spread from 50 per cent to 15 per cent in 1986 to40 per cent to 20 per cent in 1989 (Englebert and Hoffman 1996). The second phase of the programme called for a reforming of the tariff structure further, liberalising the import of locally manufactured products, increasing the ceiling on import licences and requiring that the central bank pay interest on the FBu10 million that foreign importers were obliged to deposit as a guarantee against illegal business practices. To promote exports, the programme called for the adoption of a simplified drawback procedure for import taxes and the simpli-fication of administrative procedures for businessmen travelling abroad. Tariff reductions and the liberalisation of import licensing were implemented much slower than anticipated and while quotas were abolished and the tariff structure was simplified, tariffs on luxury goods remained and those on intermediate and capital goods fell more slowly than had been envisaged in the programme. At the same time, the transactions tax rate was increased as part of a revenue enhancement package of the stabilisation progamme and cancelled out some of the impact of lower tariffs. Overall, the adjustment programme reduced effec-tive protection mainly by eliminating non-tariff barriers, but not by as much as had been originally envisaged. Until the mid-1990s, importers continued to complain about administrative harassment and constraints as all commercial imports required licences. Hence, the impact of trade reform has been limited.

Import substitution behind protective barriers through state intervention were the main principles of industrialisation in Kenya. In 1979 it was recognised that the industrialisation strategy would have to move to a more outward-oriented approach. Thus, between 1980 and 1984 it was envisaged that there would be phased replacement of qualitative restrictions with equivalent tariffs and a subsequent tariff rationalisation to provide a more uniform and moderate structure of tariff protection. But the Kenyan government halted the reform and introduced import controls for some items when the balance-of-payments position deteriorated, and during the exchange rate crisis of 1982–84 tariffs increased by 10 per cent across the board. In 1988 yet another attempt was made to liberalise imports through tariff reform as the highest rate was reduced from 135 per cent to 60 per cent and the number of categories fell from twenty-five to twelve, with tariff rates on non-competing imports being lowered (Swamy 1996). During much of the 1980s, Kenya had a significant anti-export bias on non-traditional goods. In 1988, the government introduced the ‘manu-facturing-under-bond scheme’, allowing customs authorities to waive import duties and taxes on imported materials used as inputs for the production of export goods, and in 1990 a more general import duty/value added tax exemp-tion scheme was introduced. This was complemented by a regulatory reform designed to centralise and consolidate several licensing procedures for exports and general trade with simplified procedures for new investments. 1990 saw the construction of an export-processing zone near Nairobi with exemption from tax for ten years, unrestricted foreign ownership and employment of foreigners and complete control over foreign exchange earnings.

Whilst Latin America’s exports doubled from $78 billion in 1986 to $153 billion in 1994, there was an enormous increase in imports following trade liberalisation and generally overvalued exchange rates. The major problem appeared in Mexico which ran a trade deficit of $24 billion in 1994 (Green1995). Free trade has also led to a proliferation of trade agreements of both a regional and global nature in terms of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and of Murcosur, which involves Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay.

Trade reform in Mexico began in 1985 with a reduction in the number of tariff rates to five, and the introduction of a maximum tariff that was set at 20 per cent. The government also reduced direct export subsidies, and by 1991 export incentives in Mexico included a tariff exemption on temporary imports and a programme exempting exports from import licences on inputs (Ros et al. 1996). In the same year only goods and commodities subject to price controls or international agreements required export permits and export tariffs were set at a maximum of 5.5 per cent. Mexico had also become a member of GATT in 1986 and NAFTA was signed in January 1994. As a member of GATT Mexico agreed to bind its tariff schedule to a maximum of 50 per cent ad valorem and also to implement reductions on the tariffs of the majority of its imports to 20–50 per cent (ibid.). However, by 1992 Mexico was generating a trade deficit larger than that of the early 1980s. This has been due in part to increases in imports due to the import liberalisation, and this has been particularly true of consumer goods as nearly 80 per cent of the decline in the non-oil trade balance is associated with the increase in consumer exports after 1987 (ibid.).

Similarly in Argentina, a trade account surplus of $8.3 billion in 1990 turned to a deficit of $2.6 billion in 1992 and of $3.7 billion in 1993 as imports increased from $4.1 billion in 1990 to $14.9 billion in 1992 and to approxi-mately $16.4 billion in 1993 (Chisari et al. 1996). Again this was the outcome of the liberalisation of trade that included the elimination of trade restrictions and the reduction in tariffs.

Prices and market deregulation

The deregulation of prices and markets is essentially the crux of the neo-classical paradigm and hence is at the heart of all structural adjustment programmes. It entails the removal of government intervention in all aspects of price determina-tion and, therefore, the forces of supply and demand become the determinants of prices in all markets. This follows the neo-classical theory in which prices that are determined by forces other than those of supply and demand will lead to inefficiency in the allocation of scarce resources.

Prior to the adjustment programme in Burundi, all prices of imported and locally manufactured goods were subject to controls exercised by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Prices were set on a cost-plus basis with the manu-facturer receiving a net profit margin of 10–20 per cent. The government decided to deregulate prices at the outset of the programme and to address both producer and consumer prices. They agreed to let foodcrop producer prices to be market determined and established prices for cash crops at levels sufficient to provide incentives for increased production and quality, taking into account the evolution of international prices. In addition, the government chose to liberalise the consumer price control system. The automatic system for adjusting producer prices was not implemented under the structural adjustment credit I, and although measures to improve the quality of certain export crops and to increase their production were partially successful, progress towards improving international marketing arrangements and maintaining competitive producer prices has not been satisfactory. Measures to liberalise the rice sector and to restructure the sugar complex were implemented as planned. Coffee prices remained below the 1980 level in real terms. Nominal producer prices rose, but decisions about production and producer prices continued to be made administratively and compulsory controls on plantations prevented farmers from shifting to crops with higher returns (Englebert and Hoffman 1996).

Despite attempts at deregulation, markets for most crops remained monopo-listic or quasi-monopolistic as public enterprises continued to dominate the main sectors. Virtually no policy change occurred at the farm gate level and the few changes that did take place were sterilised partly by the monopolistic nature of these markets. However, the boom in non-traditional exports (rice and tobacco) offers a contrast to the lack of success in more visible areas of tea, cotton and coffee. The liberalisation of rice prices and the introduction of private hullers led to price increases of approximately 20 per cent between 1989 and mid-1990, turning Burundi from a net importer to a net exporter of rice. Increases in the production of tobacco also reflect price incentives, as well as the technical and input support offered by the Burundi Tobacco Company to farmers under contract. In May 1992, based on the lessons from these struc-tural adjustment episodes, the conditionality of a further structural adjustment credit included several new measures to address market and price deregulation. The regulatory framework for smallholders was simplified through, among other things, the elimination of government constraints on mandatory crops and the quality and types of inputs to be applied. Also, government-administered producer prices for traditional export crops and agricultural inputs were eliminated. Public enterprise monopoly rights for purchasing, marketing and processing agricultural inputs were abolished. Finally, a moratorium was imposed on all new public investments in tea, rice and palm oil sectors and transparent criteria for allocating available public lands and resolving land owner-ship disputes were established.

The World Bank prepared two sectoral reports for Senegal in 1981 and 1989 to assist the government in formulating an overall framework for reform. In1986, public enterprise reform became part of the government’s medium-term economic and financial rehabilitation programme, supported by three structural adjustment loans, a financial sector adjustment loan and a technical assistance project. The objectives were to restrict government intervention in enterprises that could be more effectively managed by the private sector and to improve the government’s ability to manage those public enterprises that remained under state control. In 1985, the government strategy called for the privatising and liquidating of selected public enterprises, improvement of management and the performance of those that remained in the public sector, simplifying sectoral control procedures and improving portfolio management information. Since1990, the strategy has shifted from attempts to privatise non-performing public enterprises, to efforts to start with profitable enterprises and strengthen the process of privatisation.

Public enterprise reform in Senegal has been plagued by significant delays. Over the entire reform period the government has liquidated twenty-one public enterprises and totally privatised twenty-six others, together representing 42 per cent of the total number of public enterprises in the sector. However, in terms of assets and government equity, they represent only 19 per cent and 11 per cent of the sector respectively. The disproportionate percentages reflect the fact that the three utilities of electricity, water and telephones were not part of the divestiture programme, and they alone account for 33 per cent of the sector’s assets and 46 per cent of government equity (Rouis 1996).

The labour market

Neo-classical theory in the area of labour markets is again concerned with the elimination of regulations that impinge upon the free operation of the forces of supply and demand. In particular it is concerned with any regulations that decrease the incentives of employers to take on workers and therefore have the effect of reducing the demand for labour. The forces of supply and demand, as illustrated in figure 2.2 , operate in the same manner in the labour market as in any other commodity market, but the equilibrium position produces an equilib-rium wage. Hence, interference in this market will distort the outcome and produce a non-equilibrium wage. According to the theory this will be a below-optimum outcome and could lead to unemployment of labour as potential employers either cut back production or introduce more capital-intensive methods of production to reduce their wage bills.

The labour market in Ghana is segmented, with an informal sector (rural and urban) and an organised modern sector. In the informal sector, wages are deter-mined by market forces, but in the organised sector the government is the wage leader, accounting for approximately two-thirds of total employment. Since the mid-1980s, the government has attempted to restructure the size of the public sector workforce and its remuneration. Some progress towards retrenchment has been made, but a severe shortage of data makes assessment of progress diffi-cult. Despite pervasive overemployment, public sector wages have increased substantially in real terms during the period of adjustment. Between 1983 and1988, average real earnings in the public sector more than tripled. Much of the increase sought to compensate for substantial inflationary erosion that had occurred prior to adjustment. Between 1988 and 1992, the government attempted to link wage increases to a measure of productivity. Average real earnings were held more or less constant, while salary differentials were permitted to widen across grade levels and occupational categories. In 1992, organised wage demands intensified in the months before the elections and in October of that year the government agreed to increase average government service pay by approximately 80 per cent. Average real wages exploded by 500 per cent since adjustment or 20 times the gain in per capita GDP (Leechor1996). Wage rates and the quality of labour represent a major part of business decisions, particularly those of foreign companies. Wage rates in Ghana remain competitive by international standards, but this wage advantage is offset by rela-tively low levels of education and skills of the average worker.

Before the reforms of 1986, the modern labour market in Senegal had been heavily regulated by the government and suffered from a highly antagonistic system of industrial relations. The government regulated all labour practices and wage rates through labour law, which included the labour code, the 1981 collective bargaining system and the civil service statutes. These regulations led to higher production costs, limited investment, low productivity and low levels of job creation. The effect was that the government’s income policy was at odds with its internal adjustment strategy. Modern sector wages in Senegal are largely influenced by the wages that are paid by the state and in 1986 the government employed 68,000 of the modern sector, which employed 131,000 in total. Real wages in the civil service and in the modern sector declined between 1980 and1985, but remained high relative to other countries of the region. However, to compensate for this decline, the government progressively raised benefits and wage supplements, which by 1986 made up 25–30 per cent of the wage bill. Svejnar and Terrell found that for the industrial sector as a whole, total factor productivity declined annually by 5–7 per cent between 1980 and 1985 (Svejnar and Terrell 1988). Employers relied heavily on temporary, rather than permanent, employees due to the regulations concerning the laying-off of workers which required government approval and was time-consuming. In1986 the government established a national employment fund and created an agency to ease the transition of redundant workers and to encourage voluntary departures from the civil service. A World Bank appraisal of this programme concluded that the cost effectiveness of the employment fund had been diverse. Between 1988 and 1991 only 1,500 jobs had been created at a cost of $11,000 each.

The financial sector

Although Burundi’s financial sector is reasonably diversified, the government participation in the equity of the financial institutions is quite pervasive. The government holds a 42 per cent share in the capital of the two largest commer-cial banks. However, financial intermediation remains low, due to the low per capita income of the country, the low monetisation of the economy and a lack of competition among the financial institutions. During the period of the reforms the government attempted to improve its credit and monetary policy in the financial sector to make financial intermediation more efficient and to improve resource mobilisation. The first phase of the adjustment programme proposed raising the authorised credit ceiling of the commercial banks by more than 300 per cent and promoting small and medium-sized enterprises through a reinforcing of the guarantee fund. In addition, an ad hoc committee was formed with the remit to address the discrimination that was implicit in the distinction between discountable and non-discountable credit and the structure of interest rates. In the second phase there was an attempt to liberalise interest rates and to supplant credit rationing with a more indirect way in which to manage credit and liquidity by establishing a simplified interest rate structure with only two discount rates. Implementation was slow and incomplete as overregulation and oligopolistic behaviour limited competition among the financial institutions. The government and the central bank introduced a more flexible interest rate policy through the linking of interest rates to the rates obtained during the treasury certificate auctions. However, interest rates did not become fully liber-alised.

The financial sector in Kenya was fairly well developed in the mid-1980s and the government amended the banking law in 1989 to narrow the regulatory gap between classes of financial institutions by increasing the minimum capital requirements and by attempting to strengthen the central bank’s technical and managerial capacity to examine, monitor and supervise the financial system as a whole. However, the reform measures had a minimal impact as it was estimated that eleven banks and twenty near-bank financial intermediaries were in distress in 1992 and these accounted for approximately 60 per cent of total assets. In addition, interest rate liberalisation failed to reduce the rigidities that existed in the allocation of credit.

Commercial bank deposits in sub-Saharan Africa average 16 per cent of GDP, but in Ghana this is only 8 per cent and the failure to mobilise resources has restricted the availability of credit and raised the cost of investment funds which has had pervasive repercussions for the economy as a whole. Since the adjustment process began in 1983, there has been a decline in the level of avail-able credit, due in part to the direct control of domestic credit up to 1992 and, as a large part of credit is allocated to the publicly owned enterprises, the private sector has experienced a credit deficiency.

Probably the most successful of the reforms undertaken in Senegal has been the reform of the banking sector. In October 1987 the government consulted with the IMF, the World Bank and its bilateral donors with the aim of restruc-turing its ailing banking sector. The outcome of these discussions was a set of measures that included the closure of the distressed banks, reform of credit policies, the recovery of bad debts and a reduction in abusive practices. In June1989 the government adopted a capacious strategy of restructuring which called for the maintaining of only those banks that could become profitable and of privatising banks such that government interference would be reduced.

Privatisation

The Kenyan government held equity in 250 commercially oriented enterprises producing goods and services for profit. The single largest economic activity of the parastatals was in manufacturing and the parastatals accounted for more than a third of the government’s net lending and equity operations. Several attempts were made to restructure the state sector and in late 1991 the govern-ment announced its intention to divest its interest in 207 enterprises whilst retaining ownership of thirty-three strategic enterprises. However, by 1995 only five of these had been privatised or brought to the point of sale.

Ghana has more public enterprises than all other African countries with the exception of Tanzania and they have a presence in virtually all sectors of the economy. They have substantial commercial advantages over private sector enterprises and the government has continued to be ambivalent about public sector reform. Although the government appeared to have little intention of changing its role in commercial activities in the first few years of adjustment, it did acknowledge the existence of an excessive amount of labour and the poor performance of the public sector per se . Therefore, rather than allowing compe-tition from private companies, the government attempted to improve the efficiency of the public enterprises. However, as the losses of the public enter-prises rose and their burden on the budget increased at the end of the 1980s, the government began to reassess its position. Attempts were made to sell or liquidate minor enterprises and limited participation of private enterprises was allowed. But even by 1992, very few actual measures had been implemented.

Between 1989 and 1992 Argentina and Mexico sold off 173 state companies for $32.5 billion in both cash and debt relief. Generally throughout Latin America, privatisation has been seen as a means of reducing government deficits and of raising funds for current expenditures. However, whilst Mexico may be in the position of demanding competing bids from the international business community for some of its prized assets, the same is not true of other countries in the region such as Peru. Here the government must accept the first serious offer (Orme Jr 1993).

In Mexico, privatisation raised a total of $13.7 billion in the year 1990–91 which represented just less than a tenth of the government’s revenue. Of these the largest sales were of the state telecommunications company (Telemex), which raised $4 billion, and the twelve state banks, which raised $10 billion (Green 1995). Other sales included the two leading airlines, Mexicana and Aeromexico, and the copper mining company CANANEA (Ros et al. 1996).

In Argentina, the government sought to privatise a large number of state companies between 1990 and 1993, and in the first two years privatisation revenue represented approximately a fifth of government spending (Green1995). It has been argued that the most important source of financing for the public sector in Argentina has been the funds from the proceeds of the privatisa-tion programme. Indeed, from the $9.8 billion received by the government, $6.2 billion came from the divestiture of public enterprises and further inflows were generated through the debt-equity swap schemes (Chisari et al. 1996). Argentina has been the only economy of the region to privatise its state oil company (YPF) whilst others have preferred joint ventures with transnational companies. According to Green, however, problems have arisen in many of the former state enterprises post-privatisation. Call charges in the telecom sector rose by 60 per cent after privatisation and the sell-off of the state airline (Aerolineas Argentinas) to Iberia of Spain led to strikes and demonstrations when the new owners attempted to sack a third of the employees and as a consequence ran up losses of $550 million in the first three years post-privatisation.

Conclusion

As is so often the case with evaluating the impacts of SAPs it is impossible to generalise. A recent assessment concluded that ‘Neither the IMF nor the World Bank have been able to demonstrate a convincing connection, in either direc-tion, between SAPs and economic growth’ (Killick 1999: 2). The preceding analysis would bear this out, but what it is unable to do is go beyond the aggre-gate level and look at the distributional effects of SAPs or to assess their unpriced impacts. It is to these matters that we now turn.

Note

1 M3 is a measure of money supply so that the deficit/M3 ratio refers to the size of deficit to amount of money actually available.