I have yet to see any problem, however complicated, which, when you looked at it in the right way, did not become still more complicated.—Poul Anderson

By now you should feel assured that the vast continent of mathematics is yours for the exploring: nothing more nor less than being human qualifies you for the adventure. And yet, between our humanity and the abstraction of mathematics lies a Barrier Reef more formidable than Australia’s. It is edged with an endless variety of off-putting symbols that, further in, harden into equations. Their desolate expanse is often drained of what little color it has by the impersonal exposition, which some people think suits universal truths. But say you make it past these outer defenses. The shore looks inviting—yet making your way inland proves far harder than you thought. The natives seem unfriendly; the interior is hardly visible—no wonder you succumb to Explorer’s Malaise: that weary dismissal of the unreached as the unsought.

√, the square root sign, says it all. Angular, awkward, uncouth, it snarls from the page at us, daring us to come nearer. With so many whimsical and graceful forms among its antecedents,

![]()

has this one survived just to remind us of how off-putting mathematical symbols can be? In order to lead your thought on, they pull your eye up to exponents and down to subscripts, and even at times backward as well as forward, as in nCk. And it isn’t just their shapes and the way they proliferate into a grotesque forest:

not just how they stand, but what they stand for. You know it will cost you hours of deliberation to feel at home with just one of them, and by the time you’ve mastered the next, you’ll have almost forgotten the implications of the first. Take square roots again: the other arithmetic operations you were brought up on turn pairs of numbers into a single number. This one produces two numbers for every one. Slip a small 3 into the crook of its elbow, and you have to absorb why the number its arm rests on has three different cube roots.

The intention wasn’t to bring thought to a standstill but to hasten it on. Just as chess players, musicians, or meteorologists turn movements into squiggles so that anyone interested can read through them to the ideas they bear, so mathematicians reduce to no more than symbols the shunts that will carry a train of thought to the right station. How irritating it would be to have to read at length what you needed to know in and for an instant! How painful to repeat in full what you’ve already done a hundred times! And not just painful: you could actually lose your way in the tangle of words and fail to see the context with its hints of insight, from having to crawl so slowly from noun to verb.7

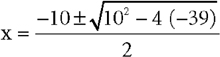

As an example, let’s go back to the quadratic formula—but way back, to the ninth century, when al-Khwarizmi wrote his algebra text:

What must be the square which, when increased by ten of its own roots, amounts to thirty-nine? The solution is this: you halve the number of roots, which in the present instance yields five. This you multiply by itself; the product is twenty-five. Add this to the thirty-nine; the sum is sixty-four. Now take the root of this which is eight, and subtract from it half the number of the roots, which is five; the remainder is three. This is the root of the square which you sought for.

Don’t your fingers itch to translate this into symbols?

x2 + 10x = 39, so x = (10/2)2 + 39 – 10/2,

or, as we now say:

hence x = 3 (and also –13; we have come to allow negative solutions, since al-Khwarizmi’s time).

The ten thousand symbols that fill up every crevice of mathematics are meant to act as ratchets do on a cog railway, keeping your thought from slipping back on the steeper ascents. When best used, they allow words to keep pace with thoughts, and each off-handedly stores an aperçu to delight in retrospectively. Each commemorates a victory of technique over the inertia of things. Why then do they so often grate on our nerves? For several reasons.

You’re not angered and frustrated by picking up a newspaper printed in a script you don’t know: you don’t expect to be able to read it. But wodges of mathematical symbols occur in the midst of your own language, for all the world as if you were supposed to take them in as easily as words. You’re wrong-footed even as you approach them. Practicing mathematicians are very familiar with this sort of thing, as when an overly general setting disguises the beauty of an insight (“This theorem,” wrote the reviewer of a book on number theory, “is often in the context of a slightly stronger result, causing the simple and elegant ideas to get lost in mere notation.”) If you ever had the misfortune of thinking you would learn mathematical logic from Russell and Whitehead’s monumental Principia Mathematica, you know what he meant.

And yet the importance, if not the meaning, can glimmer through, as it did for the historian R. G. Collingwood when, as a child, he came on a book of Kant’s.

And as I began reading it, my small form wedged between the bookcase and the table, I was attacked by a strange succession of emotions. First came an intense excitement. I felt that things of the highest importance were being said about matters of the utmost urgency: things which at all costs I must understand. Then, with a wave of indignation, came the discovery that I could not understand them. Disgraceful to confess, here was a book whose words were English and whose sentences were grammatical, but whose meaning baffled me. Then, third and last, came the strangest emotion of all. I felt that the contents of this book, although I could not understand it, were somehow my business: a matter personal to myself, or rather to some future self of my own. … There came upon me by degrees, after this, a sense of being burdened with a task whose nature I could not define except by saying, “I must think.”

In mathematics, the sheer unattractiveness of so many symbols doesn’t help. Gawky alone, contorted in clusters, it is almost as if the begetters had no consideration for their audience. What seemed like a good idea at the time often sweeps them away: ∪ might come from the U of Union, and ∩ looks enough like the A of And to stand for intersection, while ⊃ looks like an arrow, ![]() , of implication, so is a good candidate for if-then, with ⊂ for the inverse implication—so that (with ~ as negation) we can turn a law of De Morgan’s into a riddle out of Conan Doyle’s “The Dancing Men”:

, of implication, so is a good candidate for if-then, with ⊂ for the inverse implication—so that (with ~ as negation) we can turn a law of De Morgan’s into a riddle out of Conan Doyle’s “The Dancing Men”:

![]()

It has to be said, though, that all those letters from the beginning of the alphabet used as coefficients, and those from the end as variables, with subscripts chosen from the middle, lets you make quite general statements precisely and concisely, once the conventions are mastered. There are many things to say, for example, about polynomials in general, that would suffer in the saying, were they to be said instead when particularized to this one and that, or even this kind and that; so the general polynomial looks like this:

f(x) = axn + bxn–1 + cxn–2 + … + px + q,

or (so that you won’t think they go on for at most seventeen terms),

![]()

What’s happened here? We’ve done away with the arbitrariness of a twenty-six-letter alphabet by introducing subscripts that pair up with the exponents, letting us talk easily about polynomials with any number of terms (the notation alone suggests that we might go on to talk about polynomials with infinitely many terms: a telling instance of language paying back some of its debt to thought). You can see why you might want to condense even this, at the cost of a few more conventions, to:

![]()

There’s the glory and despair of symbolizing, in a nutshell. But as Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, “We are mere operatives, empirics and egotists, until we learn to think in letters instead of figures.”

Another reason some symbols halt thought rather than help it, is the point of view they embody. Consider counting. “Take computation away from the world,” said Isidore of Seville, some 1,500 years ago, “and all would be left in blind ignorance.” But try computing with Roman rather than Arabic numerals, and you might soon prefer ignorance. Exponents, on the other hand, are a brilliant invention: they not only save mental effort but suggest, by their very presence, ways to extend their use: if xm means x multiplied by itself m times, so that xm/xn would, after simplifying, just naturally be written as xm–n, why might not the “number of times” be negative too, or some non-integral rational, or in fact any real—and then even complex—number?

All the while, of course, as we draft rules for manipulating these abstract symbols, those which were just as abstract to begin with, such as 1, 2, 3, come to seem not symbols at all but parts of the familiar world. Again, the responsibility for choosing what to symbolize, and how, lies more heavily on practitioners than they sometimes realize. We’ve heard that the physicist Wolfgang Pauli flew into a rage when a student of his, at the blackboard, chose to replace a long expression, which would need to be repeated several times, by a letter. “Your expression by itself makes no physical sense,” exclaimed Pauli. “You have cut up reality wrongly. Don’t you know that signs are not harmless?”

Symbols also go bad on us because people, traditions, and eras will each devise their own sign for the same idea, and then the generally poor sense that mathematicians have of history will let this multitude pour indiscriminately down on us. Think of as simple an operation as multiplication. Most of us learn addition first, so that multiplication comes as a shock to the system. But all right, you take the sign + and roll it over on its side, ×, so that 4 × 5 means what 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 used to (and oddly enough, is the same as 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4: something to think about). You no sooner get used to what seems a streamlined sort of addition than you have to give up × for ‧ (because x is about to be used for the dreaded unknown).

Never mind that the old multiplication sign was upper case and the unknown lower: this is one distinction too many for a hand hurrying through a calculation, and a mind struggling not only with tables that flicker in and out of memory but with the profoundly puzzling idea of a letter revealed as a number when put under sufficient pressure.

Two symbols, then, for the same operation (and a further complication in countries that use a raised dot as a decimal point), until the next turn of the screw: indicate multiplication just by juxtaposing two symbols! Thus, 5 × y became 5‧y and is now plain 5y. Does that mean that 5‧6 should now be written 56? Well—no. And should you write (x + 3) ‧ (x – 4) or (x + 3)(x – 4)? That depends—on the traditions of your tribe.

Fine. You’ve been told that you must use dots for multiplying two numbers but not between a number and a letter. What about between two letters, then? Oh, that’s just xy or yx, as you choose. All right—so xx? Er—that’s written x2. Where did that come from? And since 5‧4 is the same as 4‧5, and xy = yx, is x2 the same as 2x? Actually, no.

You have to admire the wonderful flexibility of the mind, and its playfulness with language, that it can eventually master these shifting names for the same thing and the shifting rules of their usage. But then, we learn to read different type fonts, and worse, different handwritings: our capacity to abstract and generalize may be our most distinguishing characteristic, and the one on which our involvement with mathematics rests. Continue for yourself the secret history of the signs for multiplication, into n! and nCk, and beyond—and notice how what at first seemed streamlined addition reveals itself as an independent operation of growing subtlety.

The last way that symbols can mislead us comes, in fact, from this ability of ours to abstract. Things get out of hand so quickly in mathematics (“Do cats eat bats? Do bats eat cats?” asks Alice in Wonderland) that we irrationally pin our hopes on the symbols, trusting them to do our thinking for us. Let’s go back to that Math Circle class of six-year-olds coming to grips with fractions. It was exhilarating to get halves and thirds in the right order on the number-line, and to add fractions all of the same sort (although a perfectly reasonable objection was raised against 3/4 + 2/4: how could 5/4 possibly mean anything, when 4/4 is the whole thing?) But 1/2 + 1/3 was another matter.

If you keep your suggestions to yourself at times like these, you will see Mind wrestling with the intractable world. The most popular surmise (inspired by the form rather than the meaning of the symbols) was that 1/2 + 1/3 = 2/5. The most puzzling—vigorously stated and defended—was that 1/2 + 1/3 = 4 1/2 (the reasoning turned out to be that 1 + 3 = 4, which took care of that annoying second fraction, and then there’s 1/2 to add on). Other candidates included 2/3, 1/5, 1, and (after half an hour of wrestling) that there was no answer.

Symbols exercise an occult pull on the mind, especially when a wholly new idea (such as “common denominator”) is needed to break their spell. No wonder we turn in despair to Kabbalah and childish incantation, hoping for clarity from a misty prism; aversion to thought leads to collusion with language.

If these are some of the reasons for our difficulties with the barrage of symbols in mathematics, what are some of the ways to overcome them? The best is certainly to invent your own symbols, keeping the power relation between you and them clear. In another Math Circle class for the very young, we were engrossed in counting up the number of roads in and out of the various cities on our increasingly complicated map (vertices and edges, to outsiders). We found ourselves faced with problems like “13 minus something is 8, what’s that something?” and “11 plus something else is 19, so that something else is—what?” As their secretaries at the board, we grew tired of writing out “something” and “something else” and asked if they could come up with a symbol to stand for it (expecting “?” or perhaps “s,” for “something”). Cameron raised his hand: “w,” he suggested. “Good … ‘w’ for ‘what’?” “No,” he said, “w, because it looks like ‘I don’t know.’”

None of us ever had any trouble with 13 – w = 8, or 11 + w = 19, after that. Occasionally you need to mention, at the end of a course, that what we’ve called “tent-cities” are known as “points” to the rest of the world, and that “Anna’s Theorem” is elsewhere called Euler’s—but they take these failings of the world in stride.

Invented or come upon, a context of use grows up around symbols, which eventually moves them comfortably into the background of our thought. This context is at first of concepts, then of other symbols, as language takes on its role of place-holding, and its impetus thus gathers firmly behind you. Because students are eager to hurry on to using their symbols, they may be careless at first in making sufficiently expressive choices, and defining with enough precision; but conversation will tailor and conjecture trim to what works (and the admiration of others for a clarifying symbol further enhances the collegial undertaking).

A deep principle of our Math Circle is at work here: if you want students to master something—call it R—and R is a means to S, then work on S; R will slip unobtrusively in under the radar, whether it is a symbol, a technique, a lemma, theorem, theory, or point of view. This happens especially quickly with symbols, as testified to by the ease with which neologisms slip into and out of our speaking. The ripples of slang on the ocean of language delight the adventurer in us, as we roll with and cut across them. But don’t sell short this development of familiarity through invention and use; once you win the battle with symbols, your agility in mathematics bounds sharply upward.

Learning how to make symbols transparent so that we can see through them to the relations they stand for: this has been our theme. But symbols play a yet deeper role. At their best, they become visible again, but now as arrows that point to invisible structure. They aren’t simply pictures of relations, but stand-ins for them: stand-ins we can manipulate when the structures are past our reach. This distinction between pictures and stand-ins underlies a deep division between the geometric and algebraic modes of mathematical thought. It isn’t that diagrams are somehow undignified, or visual proofs inadequate, but we sense that mathematics is really about relationships, which may show up in the visible world but aren’t fundamentally embodied in it. This is our architectural instinct at work. Even numbers aren’t the ultimate referents; they are also pegs to hang relation and structure on. Ideally we want so to use symbols that moving them moves what they stand for and makes them comprehensible to us. This is very different from the obscuring signs of number mysticism. It is a reaching of the mind toward structure itself, which is dazzlingly hard to see.

In Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, Aristotle wisely gestures to the world around him: this is what mind abstracts from, in order to see it with deeper understanding (since the lunge toward abstraction is never for its own sake, but to make the translucent transparent). Plato points up: that’s where the light is. The last barrier to overcome in using symbols is learning to look not at but along them.

Do not imagine that mathematics is hard and crabbed, and repulsive to common sense. It is merely the etherealization of common sense.—Lord Kelvin

If the symbols don’t get you, the equations will. Most people’s blood pressure spikes when an equation leaps out at them, because they assume they’re supposed to understand it as directly as they understand sentences on the same page—and they don’t. But equations are the punch lines you can’t be expected to get until you’ve heard the story.

Take as simple and devastating a case as this formula:

That is, the area of a trapezoid is half the sum of its bases times the height. It isn’t much better when written out like that in words, since a reasonable reaction is “Says who?” Says the teacher or the book, in a tone of finality, and you have one more “fact” to memorize unquestioned.

In a Math Circle class on the Pythagorean Theorem, we knew we would need this formula in order to re-create President Garfield’s clever proof mentioned in chapter 4, but weren’t about to thrust it on our students. Instead we asked them what the area of a rectangle was, and got the answer: base × height, or bh. We now asked them why, and they told us—after some discussion back and forth—that if you thought of area as a sum of little squares, then the rectangle was made up of b × h of them. And the area of a right triangle? They instantly saw that you could complete any right triangle to a rectangle with twice its area,

so the triangle’s area would be bh/2.

What about the area of a parallelogram? This took more time, and eventually an insight: slice off a right triangle from one side of the parallelogram, slide it over and paste it onto the other side, and you’ve got

a rectangle again, with area bh, so that’s the area of the parallelogram too. Well, so what’s the area of any triangle, not just one with a right angle? And almost at once: any triangle is half of a parallelogram, just as a right triangle was half of a rectangle, so its area is also bh/2.

Now came what we were aiming at. What about the area of this awkward figure?

Since they had been engrossed in cutting up shapes and moving them around, drawing the diagonal BC was by now second nature to them—and there were two triangles, with bases a and b and the common height h—so the total area was ah/2 + bh/2, or—the punch line:

![]()

Equations come at the end of stories.

If you’re not in a Math Circle class but reading a book and lurch suddenly into a formula or equation, what works well is to skirt it gingerly and let the context explain where it came from. The advice Roger Penrose gives (in his article on “The Rediscovery of Gravity” in Graham Farmelo’s It Must Be Beautiful) is very good:

If you find [equations] intimidating, then I recommend a procedure that I normally adopt myself when I come across such an offending line. This is, more or less, to ignore that line and skip over to the next line of actual text. Well, perhaps one should spare the equation a glance, and then press onwards. After a while, armed with new confidence, one may return to that neglected equation and try to pick out its salient features. The text itself should be helpful in telling us what is important about it and what can be safely ignored. If not, then do not be afraid to leave an equation behind altogether.

The formula we gave as an example hasn’t the added dimension of fear that a full-blown equation has: namely, saying that two expressions, which look very different, are the same. A little equality sign is never innocent. It confronts more than two expressions: two lines of thought, really, giving the depth of a stereoptical view where before there was nothing to see. No wonder it takes some effort to look over and then beyond it. Here is a monument to past work that ended with insight, saving you the trouble of reinventing that wheel, at least. And it is a pointer toward future discoveries, since its very form allows you to shift parts from one side to the other: adjustments that can bring into the open what was otherwise hidden (so in trying to find integers that satisfy the Pythagorean relation, a2 + b2 = c2, nothing more than rewriting this as b2 = c2 – a2 lets you factor the right-hand side into (c + a)(c – a), and this—with evens and odds in mind—funnels you toward the answer.

An equation is, as Shakespeare said about poets, of imagination all compact—and that compactness, that condensation, is what scares us off. It is, say Ellen and Michael Kaplan in Chances Are:

a kind of bouillon cube, the result of intense, progressive evaporation of a larger, diffuse mix of thought. Like the cube, it can be very useful—but it isn’t intended to be consumed raw.

You’re trying, after all, to put someone else’s construction into your mind, and this takes both a kind of passive conforming of your thought to his (as an amoeba flows its shape and substance around what it would swallow), and an active, exhaustive, and often exhausting analysis that makes it, in the end, your own. You know you’ve mastered an equation when you no longer struggle to remember it. In fact, it then begins to do your remembering for you.

What makes the analysis of equations so trying is that since they are condensates, their parts, like the molecules in a crystal, vibrate within very narrow limits. No conversational leeway here, none of the fuzziness, of the more and the less, that lets us get on easily with people unlike us. Each term, each symbol, each relation is defined with a precision that takes getting used to, as builders of balsa-wood models learn to up the tolerance ante when they graduate to hardwood. Take an equation most of us feel comfortable with: in Δ ABC,

∠A + ∠B + ∠C = 180°.

In words, as people in the Middle Ages would have encountered it:

The interior angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles.

In the eleventh century the learned Ralph of Liége wrote to his friend, Reginbald of Cologne (“a man of powerful mind, who taught Latin to the barbarians of the Rhine”), that he had come on this sentence in a commentary of Boethius on Aristotle and had no idea what it meant. “Two right angles” is clear—but they could not be in a single triangle—and what were a triangle’s “interior angles”? The very meaning of “are equal” becomes opaque. Both men were baffled. Reginbald eventually concluded that these were the angles formed when a line dropped from one of the angles met the opposite side. Once (he wrote), when passing through Chartres, he had revisited their old teacher, the distinguished Fulbert, and after many talks had convinced him that this view was correct.

The deepest cause of our awe, when faced with equations, is their very depth. The great laws of physics are conservation laws: they tell us that matter, or energy, or charge, or momentum, may never be created or destroyed, only transformed. Equations demonstrate the conservation of structure: what seemed immutably one thing is disguised as something quite different. And the beauty of these equations is that the disguises they deal in don’t obscure, but reveal.

![]() , for example, is irrational, hence its decimal form must be chaotic: 1.41421356 … with no repeating pattern to those digits. But here is an equation that unveils a pattern for the

, for example, is irrational, hence its decimal form must be chaotic: 1.41421356 … with no repeating pattern to those digits. But here is an equation that unveils a pattern for the ![]() as simply intricate and infinitely extensible as anything decorating the Alhambra:

as simply intricate and infinitely extensible as anything decorating the Alhambra:

An infinite series, which should be ungraspable in its immensity, is just playing a simple game, over and over.

But just because something can be described doesn’t always mean it can be grasped: look, for example, at

1 – x + x2 – x3 + x4 – x5 + …

Easy to see how this series is formed. But how possibly guess or even estimate what this endless sum will be for a given x, even when you’re told that x is between –1 and 1?

But suppose the lights dim, and when they go up you see that this ungainly expression is simply equal to 1 / (1 + x):

![]()

as astonishing a transformation as any in pantomime. Yet there it is, an infinite series returned in a finite avatar—and to convince yourself of their equality, you need only multiply each by 1 + x (as long as x is between –1 and 1: not an arbitrary restriction, but one which signals, as so often in mathematics, “Here be monsters”).

If an equation marks the moment when Mind unites in one expression a rabble of different forms, how much more impressive are those equations that summarize, describe, and predict natural phenomena. Think, for example, of the December 2004 tsunami. Its violent chaos can be modeled mathematically. “The resulting equations,” says Gordon Woo, “yield a special combination of elastic, sound and gravity waves, which depict in mathematical symbols a scene of frightful terror.”

Of the differential equation

mx″ + rx′ + k2x = 0,

Courant and Robbins say: “Many types of vibrating mechanical and electrical systems can be described by exactly this differential equation. Here we have a typical instance where an abstract mathematical formulation bares with one stroke the innermost structure of many apparently quite different and unconnected individual phenomena.”

If these are the trials and rewards of equations “given,” what about those we are obliged to invent ourselves? We usually encounter this obligation first in that peculiar literary form, The Word Problem. If you read

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

you’re all at once there. But read instead:

A and B set out on two roads,

walking at 3 and 4 miles per hour respectively

and where are you? Suspended in abstract space with never a crossroads in sight or even a season of the year. What are you supposed to do now?

As the problem continues, with more information about when they left, and how far they were going, is some sort of relation among all these data supposed to dawn on you? Reason would piece it all together were it not stunned into silence by this barrage of numbers. You see why math teachers usually succumb to the temptation of telling you in advance that this is a “rate times time equals distance” problem; otherwise how would you know? It’s enough to make you lose faith in form underlying appearance, not just because these apparitions are improbable stick-figure formalisms too, but because the order of understanding is all wrong: an equation like d = rt has been told to you and is then imposed on reality, rather than showing through at the end like the ribs of rock that make sense of a landscape.

Mathematics is usually delivered to its audience with Spartan concision, Athenian elegance, and Olympian disdain. Intimidation follows and, more subtly, everything is made to seem on a par: the definition of a new term, the statement of an insight, its proof—so that you feel again that you are supposed to take it all in easily (when in fact years of effort may have gone into smoothing serious controversy into a phrase, or years of frustration into an innocent-seeming remark). The causes of this impersonal style lie in philosophy, psychology, sociology, pedagogy, linguistics, history, and even economics. The effect by and large is disheartening: gods tend to cut you no slack.

The economic reasons are straightforward. With thousands of intricate proofs published yearly in professional journals, space is at a premium, so the contents are freeze-dried. You are expected to rehydrate them at your leisure, paying for the saving of public space with your private time. The constraints of journal publication reinforce deeper impulses to condensation.

The most benign of these is pedagogical. “It is left to the reader to show …,” because the reader learns best by active engagement, and here is a push-up, a jumping jack, to tone the muscles. It is when the reading turns into one of those Swedish training circuits, with new calisthenics to do every twenty paces, that you begin to wish you were back by the fire, being read to.

A kind of authorial impatience tends to creep in as well. There’s the point you’re eager to get to, and here is a half-imagined reader slowing you down with needless questions. As a ninth-grade teacher once said to our son, “You don’t see that? I see it!” And besides, you were leisurely, tolerant, and explicit at the beginning, when you spelled out your intentions and even defined the terms that needed no defining. Now you can pick up the tempo or, like the pilot of a giant jet, sharpen the angle of attack after takeoff. Those who should will keep pace: we’re not in grade school now, as Hilbert said to a foot-dragging student.

Some people undeniably relish dashing at top speed through their exposition (a leftover from whiz-kid days and calculating wonders) in the belief that brilliance is shown by taking the shortest way in these mountains: from peak to peak. A solid history is there to support them, back to Descartes, and before him, Aristotle. Descartes held that the cogency of your view was shown by the smoothness with which you expressed it (which is why our ums and ers become prolonged syllables in French). Aristotle said that wit consisted in detecting the missing middle term in syllogistic reasoning; twice witty, therefore, he who, with brevity in his soul, omits them for his audience to discover.

“Il est aisé à voir,” the eighteenth-century mathematician Pierre Simon de Laplace writes again and again in his Mécanique céleste: “It is easy to see.”8 His American translator, Nathaniel Bowditch—no slouch himself as a mathematician and astronomer—said that he never read this phrase “without feeling sure that I have hours of hard work before me to fill up the chasm.” Impatience or pride on Laplace’s part? What should we make of Laplace himself (according to his assistant, J. B. Biot) wrestling for an hour to understand what he had dismissed with an “easy to see”? Think of your IKEA filing cabinet finally assembled. Those plans lying in tatters of rage on the floor are self-evident, aren’t they—in retrospect? And it is from this long view that math is written: now that you see it, how could anyone ever not have?

These winks and nods also serve to cement the fellowship in an exclusive club. But clubland plays another role in the genesis of a style both allusive and laconic. Published work grows in a conversational matrix, where ideas and language fitfully evolve. If you are in on this conversation you will have little trouble reading what amount to the polished minutes; if it took place in your absence, the minutes are from Mars. Even the art of writing minutes, however, can contribute to problems of understanding for the initiates. “No argument,” says Alf van der Poorten, “tries to dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t.’ Even correct arguments will contain gaps. But the trouble is that we may have conquered the apparent obstruction without realizing that we have now brought a real difficulty to light. It’s that kind of thing that causes such admissions as ‘my proof developed a gap, and that gap became a chasm that swallowed the proof.’”

We’ve noticed, in some, an interesting side effect of these difficulties. Writers of fiction and essays strive to say much in little, hoping the reader will be led by allusion to complete brief touches to a rich whole. We spoke of mathematical style as allusive and laconic too—but the allusions are of a very different sort (canonical rather than impressionistic) and the brevity comes not from understatement but portmanteau symbols. “Mathematicians have developed habits of communication that are often dysfunctional,” writes William Thurston. “Most of the audience at an average colloquium talk gets little value from it. Perhaps they are lost in the first five minutes, yet sit silently through the remaining fifty-five minutes. Or perhaps they quickly lose interest because the speaker plunges into technical details without presenting any reason to investigate them. At the end of the talk, the few mathematicians who are close to the field of the speaker ask a question or two to avoid embarrassment. … Outsiders are amazed at the phenomenon, but within the mathematical community, we dismiss it with shrugs.”

Less savory are the uses of this way of speaking to keep clarity at bay. In 1895 the biologist W. F. R. Weldon wrote to Francis Galton about an attack on his conclusion by the statistician Karl Pearson: “Here, as always when he emerges from his cloud of mathematical symbols, Pearson seems to me to reason loosely, and not to take any care to understand his data. … Can we not get some mathematician on our committee? The position now seems to be that Pearson, whom I do not trust as a clear thinker when he writes without symbols, has to be trusted implicitly when he hides in a table of Γ–functions, whatever they may be.”

The Code Napoleon has much to answer for here, as it does in so many aspects of life. For once you understand that law precedes practice—that there is a correcte way to deal with contingencies before there are any contingencies at all (there was a right way to make a sauce béarnaise before a cook ever set foot in a kitchen)—you understand too that form and the correcte are twins. Since the stuff of mathematics is form, it follows that it is the home as well of correctness, which is three parts elegance shaken with two parts élan. Oh yes, there’s having insights and devising proofs—but as a mathematician we know was told in his student days, after proudly demonstrating a page-and-a-half-long proof, “Your proof is certainly not wrong. But elegance will come.” These are some of the psychological components in the quality of distance that mathematical exposition features.

As the psychological turns to the pathological, we move from those who care that their audience can’t follow, to those careless of it, to those past caring. Careless, out of an unexamined assumption that whoever wants to read on must be able to tell the strategic steps from the tactical (even though they are just numbered consecutively)—and, of course, math’s ancestry in magic and mystery encourages a tendency to pull rabbits out of hats. Careless, also, because with natural or acquired autism they assume that their not understanding others means that others understand them perfectly well (a proposition not as irrational as it sounds at first, if you take it as a generalization of “you know what I mean,” implying that since it is so obviously true, it would be embarrassing to spell it all out). Those past caring whether anyone follows are delivering an exposition to eternity—which brings us to the first serious defense of mathematics as presented in the third person remote. We will put this defense in the form of a little essay.

Mathematics contemplates what is. None of the trimmings that are part of becoming therefore matter: who discovered its theorems, or how. Even the proofs devised by humans are no more than columns that raise up their architraves of truth into the still sky. If the proofs are to partake of Being too, it is only by stripping them of time’s accidents and the idiosyncrasies of place.

How could we ever reach such conclusions as these? Instincts are the mind’s equivalent of axioms, and interpretations of the world follow from them as surely as do theorems. From the architectural instinct, at any rate, derives this view of the world as form. It accounts for so much: the set theoretic language of mathematics, in which even functions are frozen to objects; the aesthetic, more Scandinavian than Victorian, that seeks out the spare, the blanched, the unupholstered; the medieval modesty of its craftsmen, who wouldn’t spoil the lines of their constructions with maker’s marks.

“Virgil shows me clearly what I fled from,” Einstein once said, “when I sold myself body and soul to Science—the flight from the I and WE to the IT.”

Having once glimpsed the a priori explains indifference to the synthetic. This is why mathematicians so notably lack curiosity about the historical, biographical, or even heuristic sides of their calling. This is why Gauss spoke for so many of his colleagues when he insisted on removing the last scrap of scaffolding from his monuments—freeing the Work from the trappings of work. This is why mathematics is typically praised by its practitioners for its chilling elegance, its impersonal attraction, its austere beauty.

The recursive character we spoke of earlier, the role of symbols as pointing beyond themselves, are at once symptoms, causes, and effects of this thinking about structure untainted by matter, this speaking in understatement untinged by irony.

“For a mathematical theory,” said Arthur Cayley, “beauty can be perceived but not explained.”

The Buddha view is from beyond the limit that converging series approach. With such retrospective looking it is, of course, “easy to see.” Finding ourselves this side of those limits, however—uncertain which lines of our thought converge, and to what conclusions—we need any help we can get. If it is from those who have seen less darkly and have returned to instruct us, we shouldn’t be surprised if they speak in tongues. Their language contracts as it draws away, and is meant to draw us with it.

When you approach an unfamiliar subject, you hope to work from whole to part, catching the shape of the thing so you can always sense where you are as you move into its details. But it is just this whole that mathematical style and language so often veil from our intuition, asking us instead to grant one thing and define another while creeping through deductive gates.

“Intuitive minds,” Pascal wrote in 1660, at the beginning of his Pensées, “being accustomed to judge at a single glance, are so astonished when they are presented with propositions of which they understand nothing, and the way to which is through definitions and axioms so sterile, and which they are not accustomed to see thus in detail, that they are repelled and disheartened.”

Still, a thoughtful mentor might reason that it is a different kind, a new way, of seeing that we must master, and one that can’t be acquired gradually: you blink, you stare, your focus shortens and blurs—and all at once you simply see. There is nothing for it but to begin.

Think of the old joke about the child who comes home to tell his parents proudly what he learned in school: two apples plus five apples is seven apples. “Good,” says his mother, “and how much is two bananas and five bananas?” “Oh,” says the boy, “we haven’t done bananas yet.”

He hasn’t a clue, you think: he hasn’t abstracted to 2 and 5, from numbers as adjectives to numbers as nouns. When will it happen, and how, that he comes eventually to know (almost without knowing) that you can divide eight apples by 2, but not by two apples? That five apples minus two apples makes sense, and so (with a stretching of sense) does five apples minus six apples—but five apples minus 2 makes no sense at all? If you’ve forgotten how puzzling these abstractions can be, and how subtle their grammar, open a text in some branch of mathematics you don’t know (“An Eff object (X, = x) in Hyland’s sense gives an assembly (A) with X as ambient, where each caucus An contains all x such that n realizes x = xx.”)

A mentor who is sympathetic as well as thoughtful might let it be guessed that the structure built with this language has no shims: it is perfectly mitered, finished with emery paper. So the old cathedral builders, they say, fitted even the inner facings that would never be seen to the highest standards, for the greater glory of the structure and what it stood for—which, with the recursive cast of mathematics, might well be itself.

He might let on that language, left unadorned, becomes transparent: we are led to look through it—so that we see with new clarity the intuition we had abandoned. And he might so position you with respect to this remote vista that you came to see it as the supple vessel for your imagination, since its impersonality means that none is imposed on yours. What is almost the defining quality of mathematics—its recurrent generalizing that subsumes each latest breadth under a new expanse—follows from the very abstraction with which it is put. Mathematics is freedom.

The tree under which the Buddha found enlightenment was even more remote from human affairs than he became. Mathematics grows like a tree from its central core of number and shape, sending out ever finer ramifications that disappear in the higher air. We may scurry under its bark or twitter awhile like birds in its branches, but it outlives us all in its grander rhythm. The beauty of this shape against the sky, and the beauty at its finest buddings are what we so love.

Yet for all that its branches are in the air, a tree has its roots in the ground, and those of mathematics spread out toward our common thought. We would delight in its forms no less were the access to them made easier. Is concision really the best way in? “One should strive above all else to avoid [an exaggerated desire for conciseness],” said the mathematician Liouville, “when treating the abstract and mysterious matters of pure algebra. Clarity is, indeed, all the more necessary when one tries to lead the reader farther from the beaten path and into wilder territory. As Descartes said, ‘When transcendental questions are under discussion be transcendentally clear.’” Or as Poincaré put it: “Every time I tried to be concise I found that I became obscure, and decided I would rather be thought of as being a bit garrulous.”

The ideal (beginning to be approached here and there on the Internet) would be to display mathematics fully, as a tree in cyberspace, so that you could find whatever you wanted to know about it and be led back, link by link, to the level that at last made intuitive sense. So the adult Hobbes saw a copy of Euclid lying open to the Pythagorean Theorem.

He read the proposition. By G_, says he, (he would now and then sweare an emphaticall Oath by way of emphasis) this is impossible! So he reads the Demonstration of it, which referred him back to such a Proposition; which proposition he read. That referred him back to another, which he also read, and so on that at last he was demonstratively convinced of that truth. This made him in love with geometry.

This tree would not only have every statement that had ever been proven linked to each of its proofs, and each step in each one of them similarly proven, down and down (a vast Borges-like library in the only space large enough to house it), but conjectures, as they arise, like frail buds from each of the tree’s extremes, along with false conjectures and mistaken proofs that had yet proven fruitful; and the whole continuum, from idle speculation to serious thoughts about these statements and about the growing tree itself, alighting and nesting and flying from it, moment by moment, back and forth to the neighboring trees of physics and philosophy, and all the contending progeny of Mind.

We could range over this tree in whatever way our different styles of learning took us, lingering here, leaping there, zooming out or in, and then climbing higher—or out of that tree remote from us in cyberspace, and into its developing likeness in our minds, summed of personalities and now at last fused with ours.

In The Revelations of Dr. Modesto, a cult-novel of the late 1960s, Alan Harrington describes Mirko, the Human Fly. A man of invincible will, Mirko plans to walk in a straight line across America, no matter what heights or depths stand in his way. Special suction-cup shoes will let him walk up the tallest buildings.

What would Mirko have done had mathematics been one of them? For as William Thurston remarks, mathematics is a tall subject, with concepts built on previous concepts:

It is possible to build conceptual structures [in it] which are at once very tall, very reliable, and extremely powerful. The structure is not like a tree, but more like a scaffolding, with many interconnected supports. Once the scaffolding is solidly in place, it is not hard to build it higher, but it is impossible to build a layer before previous layers are in place.

Willpower and suction cups aren’t enough for scaling it, and the temptation to skip, or just touch and go, past the lower levels is very great. If you can slide past an equation, why not a chapter or a whole topic? The learner has no intuition of what is central, what parenthetical, what is structure and what illustration. There are no equivalents here of the toothpick bridges that young engineers delight in stress-testing; no toy or game resembles the upper reaches of mathematics even as closely as Monopoly does the arbitraging of adulthood.

Very well, Mirko shouldn’t be walking up the outside and peering through the windows; he should be in where the action is. And once inside, won’t there be express elevators? To paraphrase Euclid, there are no express elevators in mathematics. A little bit of darkness left behind—an ambiguity, a false assumption, a technique skimped, a concept misconstrued or overlooked—will rot the foundations out from under you.

You see it all in a wonderfully comic scene from Nicolas Philibert’s film Etre et Avoir, about life in a rural French school. A twelve-year-old is trying, with his mother’s help, to multiply two numbers together.

“3 × 6, 18, put down the 8, carry the 1—”

“Go on.”

“I’ve finished.”

“What? Isn’t that a 5?”

“5 × 6—25?”

“Recite the 5 times table.”

Now the father sits in. “All right, I’m waiting. Where does it fit in?”

“There—no, there.”

The father: “What’s after the point?”

“And before it?”

“Another three.”

“Get your uncle to help you.”

Soon the whole family—mother and father, older brother, uncle—are bending over the tortured piece of paper.

“How much is 6 x 2?”

“12.”

“He’s peeking in his book!”

“Don’t forget to carry!”

“ … plus 4—I’m lost.”

“I’m lost too.”

“There’s a mistake there.”

“He hasn’t shifted it.”

“You forgot this thingummy. It should go here.”

“Here?”

“Yes. There’s something wrong now.”

“Where am I?”

“I don’t get it.”

“He has to shift it after. Otherwise—”

“What’s up? 1 to carry … ”

“12, and 1 to carry—13—”

“There’s a mistake somewhere—”

“It’s not right—”

“It’s right—move your finger.”

“OK, that’s right!”

“No it’s not! Look there! It’s out by two figures!”

“No, that’s normal!”

“No way!”

How could you possibly be fluent if you don’t understand the idea behind the technique? And if you more or less understand it, the less will eventually shake the whole structure to pieces. We had a friend who managed to steer clear of the kitchen until his wife fell ill and he wanted chicken soup with matzo balls.

“All right,” she called out him, “I’ll tell you how to make it. First beat the egg white into the matzo meal.”

Half an hour later he came into the bedroom, exhausted. “I’ve been beating all this time and they won’t mix together!” He had been trying to beat the papery skin inside the shell; it was, after all, white.

Many people, perhaps the majority of those who have run into math, have left it after the ground floor, where they first encounter signs for concepts and struggle to understand what it is that’s being talked about: to understand that the apples were there only for the sake of how many there were; that numbers are things too, and somehow more long-lasting. Many of those who survive this will jump out of the second-floor windows, since it is here that the serious business of adding fractions is going on. Even the Greeks, our mathematical heroes, had trouble granting fractions the status of numbers. And now these have to be of the same sort in order to add them. If you come to terms with the abstraction of common denominators, finding them can still leave permanent scars on minds not yet nimble at division and multiplication.

But say you get through arithmetic with part of your ego intact. Each of us vividly remembers our awe of the big kids, who were up on the next floor doing something mysterious called algebra, and now we were supposed to be doing it too. Yet after all that work getting numbers and the signs for them straight, here was a sign thrown in among them that couldn’t be pinned down at all. It didn’t seem fair.

Algebra: a peculiar science, which takes the quantity sought, whether it be a number or a line, as if it were known or granted, and then by the help of one or more quantities given, proceeds by undeniable consequences, till at length the quantity, at first only supposed to be known, is found to be equal to some quantity or quantities, which are certainly known, and therefore is likewise known.

This definition comes from a mid-eighteenth-century dictionary and expresses its author’s perplexity along with ours. Little wonder that what immediately follows it is

Algema: a pain, a sad troublesome sensation, impressed upon the brain from a smart vexatious irritation of the nerves.

We have barely come to terms with x as the unknown quantity, when it transforms itself into a variable, taking on more shapes than the Old Man of the Sea. Many a child, confronted with y = 3x + 2, has plaintively asked, “Yes, but what is y?”, only to be told that it depends on x. “But what is x?” “That depends.” How can it depend? Does 5 depend on apples or oranges for how much it is? The issue is a deeper one: if you ask children whether 3‧4 = 4‧3, they’ll agree at once. “And does 5‧7 = 7‧5?” Of course. “So ab = ba, for all a and b?” What? What are you talking about? Which a and b? This is a classic example of how readily, once we master an abstraction, we incorporate it into our machine language and forget what it was not to know it.

These are the lowest floors in the endlessly tall, widening building of mathematics. You might think that having climbed successfully this far would mean that your skills with pick and piton would see you through to any height—but calculus lies one level farther on. People who rightly feel proud of mastering arithmetic and algebra give it all up when confronted with having to learn in a year what took more than two centuries to clarify: how to speak about change with fixed but ever diminishing numbers. We smoothly take in the slope of a straight line as the difference in a pair of its y-coordinates over the difference in the x-coordinates of the same two points—but “pair” means two different points. How can we be asked to find the slope as one point becomes the other? How can “approaches” turn into “at”? We are all as atheistic as Bishop Berkeley when it comes to the heathen gods Delta and Epsilon.

At each level in this building we think ourselves near the top—only to find that what seemed a skylight was an air shaft. We tend not to notice until much later that we have become significantly more limber with abstractions, and our imaginations breathe more comfortably at these greater heights. We also begin to sense that the way up involves a way down: not only does the momentum for rising come from repeated recoils, but there are ramps of analogy here and back staircases of models there that let us return to the algebra or the geometry we knew and understand it better—and find that it also now helps us better to understand.

Mathematics has a final surprise for us: from time to time its building folds up like a telescope. How abstraction itself works—compacting the broadest structures we know to objects in structures broader still—begins to dawn on us, and we also catch glimpses of the building itself, reflected in its windows. What you understand on one floor subsumes the floors below.

All those differently inclined straight lines are species of a single equation; those lines, and the radically different shapes of circle, ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola, come from just slicing a cone at different angles, and those slices are themselves unified when seen projectively—and projective geometry lies in the gamut of geometries explained altogether by group theory, and …

This isn’t a wholly benign process: a kind of amnesia sets in when all telescopes to nothing, and you forget the immense energy of imagination that got you there. Yet at these moments the slightest nudge can be enormously significant, lifting you up to the next floor. The chutes and ladders that materialize, as the building becomes surreal, work a change too on our seeing—our structural seeing—of the landscape it lies in: we see that it is all there, all of a piece; the connections belong to how we come to understand it. These paired but opposite insights differently satisfy our architectural instinct.

Redmond O’Hanlon describes this scene, deep in the rain forests of the Amazon: “Jarivanau and a small wiry man tried to re-measure their gifts, by stretching the fishing line diagonally from the big toe of the left leg to the forefinger of the right arm. The calculations, however, soon conjured up that look of blank pain and unfocussed anger that only mathematics can produce, and, with a sudden grin and a shrug, they gave up.”

We’re more than familiar by now with the nature, and many of the sources, of this pain and anger. What we want to focus on here is that sudden grin. For the pain would be pointless if, as in sports, it didn’t lead to pleasures that couldn’t be reached without the training. These are pleasures for all, no matter how little a person will later be involved with math: the pleasures of seeing the sense the world makes; of pride in your kind, for finding out how to uncover this sense; of heightened self-esteem, that you can master what seemed unattainable skills; and the pleasure of hearing this music without sounds, seeing this translucent architecture.

Those who are immersed in mathematics relish these pleasures daily—although this isn’t the reputation mathematicians have in the world at large. Some see them as Oscar Wilde did, in his fairy tale “The Happy Prince”: “The Mathematical Master frowned and looked very severe, for he did not approve of children dreaming.” A century on from Wilde’s day, with more users of mathematics in the general population, this view has moderated, so that they seem less frightening than uncanny, like the patrons at the space bar in Star Wars, bleeping at each other in barely intelligible bytes. This view of mathematical culture puts off many who are otherwise attracted by its content (you may like Pictish designs, but would you have wanted to be a Pict?).

A few outlandish people, it’s true, make their home in mathematics, and engrossment in its pleasures may short-circuit social banter; but while abstraction is a comfortable refuge for people oppressed by personality, geekishness isn’t an entrance requirement. You’ll find as wide a distribution of types here as in any community determined by interest: actors, sports fans, lawyers. What were the masons who built the pyramids like, and what did they talk about?

Now if in fact you can be of any sort, with regard to the rest of our human traits, and still prosper in mathematics—if the mathematical microcosm has well-filled niches corresponding to those of the world at large—then how has it managed to come by and to keep its reputation for being a club of obnoxious and arrogant children? Even some mathematicians seem to think of it so: Gödel reportedly said that “the gist of human genius is the longevity of one’s youth,” and the Russian Kolmogorov held that a mathematician’s psychological development halts at the age that the math bug bites him (he thought of himself as forever twelve, but an eminent colleague of his as arrested at eight: the age at which boys pull the wings off flies).

Of course children needn’t be obnoxious—this is taken to be a quality thrown in for free with the mathematical kit. It is beautifully illustrated both by the content and framing of an anecdote told about one mathematician by another: “Student X would declare in the middle of a talk: ‘All this is trivial.’ Taken out of situational context this may seem impolite, but actually this was quite productive. He pressed lecturers for more competence. Soon he had to emigrate.”

We can certainly pinpoint one source of this unattractive side of mathematical culture. Just as some people think that children are fundamentally vulgar and need to have simple ideas explained loudly to them by goofy characters, others in charge of their upbringing believe that these little monsters will respond only to appeals to aggression, and—missing the point of mathematics as well—pervert the savoring of beautiful insights into opportunities to put one another down. My triumph (they get across) is all the greater for your defeat. This spirit, which feigns Greek origins but owes more to Leni Riefenstahl, has succeeded in giving what is meant to be a little-boy cast to much of the mathematical world (discouraging not only little girls but many an adult not charmed by the whinnies of success). It accounts for the otherwise anomalous practice of asking that problems be solved under time constraints and contributes, incidentally, one more reason for the in-language being cryptic.

But children are neither fundamentally vulgar nor fundamentally aggressive; they are fundamentally adaptable, and eager to take on the coloring of their surroundings. It is up to their mentors (as we suggested in chapter 3) to make the context of mathematical thought as supple as it is subtle, with the focus on the developing structure rather than on one’s own prowess.

You would think this was especially easy in mathematics, which—by its emphasis on the architectural instinct—will draw to it those who are more comfortable with relations per se than relations among people, and here indeed may lie its attraction for many a preadolescent boy. With mathematical culture as it is presently constituted, this shyness blossoms in those joke categories of nerd, wonk, dweeb, and dork.

We once overheard some young mathematicians intent on getting the definitions of these terms right, as a mathematician should. To an outsider their conversation would have sounded self-ironic, to an insider, self-referential—what mattered was that in either case, “self” became satisfyingly remote. One of the more canonical definitions given was that a nerd was anyone who would engage in such a conversation. A dweeb was defined as someone who owned an automated tie-rack (“What’s a tie?” asked a wonk; “What’s ‘automated’?” asked a dork). Some held that nerds flattened and nasalized their vowels, as a sort of shibboleth; others, that being a nerd meant you weren’t aware of intonations, much less shibboleths. They concluded that in math, nerds can’t help but get things right, dorks can’t help but get them wrong, and dweebs aren’t aware of a difference between right and wrong. This made wonks (said a nerd) the excluded middle.

That conversation gives the flavor of many a math camp and math common room, when problems and conjectures aren’t being traded. How does its lightly self-deprecating tone square with the self-aggrandizement that camouflages the variety of personalities engaged in mathematics? Via the innocence of the egotism such competition brings to the fore. It isn’t that a gene leading to social grace vies with one begetting mathematical agility for the same site on a chromosome, but that the abstractness of mathematics comes to infect what it touches, producing a kind of secondary autism. You see it in the unfocused smile of triumph, so like those on the faces of young chess champions: “It was a beautiful win!” A very shrewd friend of ours, the responsible daughter of a highly dysfunctional family, noticed this. “I wish I could be autistic, like a mathematician,” she once said, “so that I’d no longer feel the strain of caring for my relations.”

Is this, then, a community you’d like to join? Its ills are as superficial as those of any pursuit in its preadolescence. As more people come to dip and then plunge into math, their diversity will smooth away the oddities exaggerated by its small population now. The singular will take its place beside the general, selves will recognize and savor other selves. And when competition goes out of fashion, and collegial enjoyment replaces it, we will all look back on the spoiled children of these early days with the sort of affection that only distance allows.

And of course you hardly need sign up for lifelong membership. Among the many subjects you study, mathematics—rightly approached—will promote a clarity of thinking, a playfulness of imagination, and a freedom of invention that will enhance whatever you choose to turn your mind to.

If math is our other native language, should we not speak it fluently, once all the barriers have been removed? Of course: as fluently as we speak the language we have been brought up with. Still, just as we need at times to search for the right word, the apt phrasing, we’ll have to look now and then for how most elegantly to express a mathematical notion, or how to set up an equation or a deductive argument with the greatest transparency. Some prose, and certainly some poetry, takes careful reading to get the feel of the writer’s style; and so does following someone else’s proof. You don’t read Shakespeare or Gauss with the TV on.

But just as there are thoughts too deep for words, no more than pointed to by language, so there are depths in the mathematical landscape that will take all our art to fathom. A gem of a mathematical idea, rotated the better to find an accessible facet, can be hard as a diamond.

The mathematician father of a young Math Circle student once told us he was sorry his son was enjoying the classes so much. Why? Because it might tempt him to become a mathematician, and that meant signing up for a difficult life. Although Pascal’s father was also apparently discouraging, this parental complaint is very unusual, but anyone who has ever studied math, and everyone who practices it, has had hours or days or months when not superficial discouragements but intrinsic difficulties have made it out-top Everest and plunge deeper than the Marianas Trench. A mistake in math is rarely trivial: it’s not your facts but your way of thinking that you’ve gotten wrong.

Let’s face this squarely. The difficulties begin with trying to learn a piece of established mathematics—in a course, or from reading a text or someone’s paper. For all the feigned impersonality of exposition, the presenter’s choice of style, order, and language is unlikely to be yours, and because the pretense is that the story is telling itself, you feel you have to rejig your mind to the way things are. While this isn’t an intrinsic difficulty—not part of what’s hard in the mathematics—it does lean a psychological weight on your learning: you are a supplicant at the shrine of eternal truth. And you must listen very carefully to the oracle. You have to gather where the stresses fall: here’s an important theorem on the way to the target, such as the Pythagorean Theorem. Without it, we couldn’t navigate through our world or build anything in it. And here’s just a lemma needed to prove the theorem (one, perhaps, about congruent triangles). “Just a lemma”: one step of many, so it shouldn’t be high. Serious problems, however, can lodge in a lemma as well as in the theorem it steps up to.

What sort of difficulties are these? They almost always arise from the problem not being sufficiently in focus (are we talking about geometry or algebra?) and its context not being vivid or accessible enough. This is only made worse by not realizing it. The conditions of a statement, for example, may be subtler, or more (or less) restrictive, than you credited them with (the squares on the sides can face inward as well as outward); or you may have lost track of some (one of the angles has to be a right angle); or they may have consequences or antecedents that should immediately have come to your mind (entering, we often rush past the keepers at the gate with no more than the briefest glance: does this hold in higher dimensions, or generalize to triangles with no right angles?). A careful writer of fiction will choose his words to resonate with others in passages he wishes you to recall when reading this one; mathematical reference isn’t oblique, but the symbol, the equality, the argument before you is to be read with its past occurrences in mind. So too inference plays the role of ellipsis: parts of a chain may be left out if the author expects his reader to fill them in from familiarity.

What we could call the romantic style of exposition will leave it up to the reader to know where he is and where he’s going or—in the spirit of adventure—not to worry about it. This can tax your patience and powers of concentration, as you try to sort out tactic from strategy, and to understand fully where you are while knowing that it isn’t yet where you wish to be. Losing the way can quickly lose you the end: “Who cares?” lies in wait down every blocked alley.

The nature of language requires us to present arguments linearly, even when they aren’t. We spoke before of the awkward symbols that make the eye dart around when it wants most to move forward; this is the complementary problem. Here you need to move around in the problem’s context, seeing how the statement fits into that which you do and don’t know, to remote foundations, and to far-flung implications. This is what’s meant by “getting your mind around it.” And there’s the exposition, marching steadily on. It takes reading and rereading, looking away, thinking sideways, seeing instead of saying, until the parts unexpectedly snap together and you’ve simply got it, and wonder what all the fuss was about.

A last difficulty in following someone else’s mathematics—and one peculiar to the art—is the penchant everything in it has for leaping to the general. This leap often takes us where we want to go (seeing a problem that has filled our point of view now as a locale in a landscape that makes sense of its structure)—but we need to keep hold of where it and we are as the scale of everything slides about. “When we want to think about a mathematical situation,” say Hilton, Holton, and Pedersen in their delightful Mathematical Reflections, “it is usually a good idea to think about examples of this situation which are particular but typical.” Fetching from afar can bring you back, like Rip van Winkle, at a different age from your earthbound self, and the two need to be reconciled.

These are among the intrinsic difficulties in simply reading mathematics. They multiply when we set out to do the exploring ourselves. The situation really is very odd, when you stop to think about it. “We all find ourselves in a world we never made,” says Sherman Stein in the preface to his Mathematics: The Man-Made Universe.

Though we become used to the kitchen sink, we do not understand the atoms that compose it. The kitchen sink, like all the objects surrounding us, is a convenient abstraction. Mathematics, on the other hand, is completely the work of man. Each theorem, each proof, is the product of the human mind. In mathematics all the cards can be put on the table. In this sense, mathematics is concrete, the world is abstract.

Even if you only take the invention and the proving as human work (making congenial to our thought the way things independent of us can’t but be), why should our own inventing be so difficult to understand? For the same reason that self-analysis is notoriously hard.

To begin with, there’s forming an idea of what the problem is: making it sufficiently suggestive without becoming impossibly vague. And now what? Are there any strings hanging down from it to tug on? Our intuition may not even incline us one way or the other about the idea’s likelihood (as with tiling that rectangle … or not). We steep ourselves in the problem, we turn it around this way and that, we prepare the path, but we always find ourselves speaking feebly, in a passive voice, about what happens next—if it happens at all: the revelation appearing to your prepared mind (“Come,” sings the milkmaid to Lord Krishna, in E. M. Forster’s Passage to India, “come, come, come. But he neglects to come.”) This is the hardest part of what is hard about mathematics: having no ultimate control over our insights. It is the price we pay for not being automata, and the clearest evidence available that the order of the world isn’t quite the order of the mind.

Should you have your revelation, however, a problem of a wholly different order begins: proving it. You need to become a specialist in the art of intermediate fictions. There are the axioms, propping up the vast palace; and here is the turret you hope to build out from its upper reaches. You need to panel the interior and seal the surface, but above all shape the struts that will carry this weight down to those foundations. The enterprise has an almost linguistic character: you need to find expressions that will connect these remote extremes. Struts, expressions, connective tissue: what you hope to build are artifices that will allow our collective way of seeing (summed up in those axioms) to look out of your particular window. Think of an insight as a system of mirrors that, once they reveal a pathway, can be replaced by a less angular proof. The number of proofs that accumulate around the average insight testifies to how artificial in character, how ingenious in execution, this process of validating is. And how precarious! Not a few proofs have turned out to have been done just with mirrors, and needed to be revised or even abandoned.

You will find a new challenge when you step back from your theorem to the theory it is now part of and try to understand how the context has altered with this new content in its midst. Consequences reverberate backward and forward through the texture. If they unsettle more than they establish, you may have to rethink even what, by taking it for granted, allowed you to construct your proof. But this is the call. Answering it is the work of mathematics: a process almost indistinguishable from its product.

Go back to that telling passage from Redmond O’Hanlon: “The calculations, however, soon conjured up that look of blank pain and unfocussed anger that only mathematics can produce, and, with a sudden grin and a shrug, they gave up.”

You see that shrug, you hear its vocal equivalent, “Who cares?”, in classroom after classroom the world over, day after day. What are we to make of Weil’s remark about achieving knowledge and indifference at the same time? You could be pardoned for doubting its sincerity when you find Weil also writing: “As for my work, it is going so well … I am very pleased with it, … I am thrilled by the beauty of my theorems.” We know this sort of ambivalence from Don Juan tales of amorous dalliance: no one matters more than Donna Elvira before the conquest; no one matters less after.

But something else is happening here: the peculiar rapidity, in mathematics, with which frontiers turn into suburbs. It is as if insights were just rollers that discovery trundled over. You see it most blatantly in what we could call “algebraic amnesia,” since algebra indifferently stores up results without a trace of what led to them.

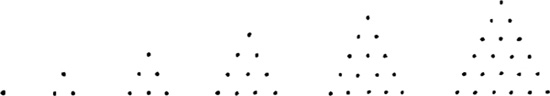

Take, for example, the stunning visual revelation that any square number is the sum of two triangular numbers. A square number, like 9 = 32, looks like this:

while a triangular number is like a two-dimensional pile of cannonballs, with each row having one more dot than the row above:

and counting up all the dots in each triangle gives us the triangular numbers:

How essentially different the two species appear—and yet looking at a square number slantwise shows that it is made up of two triangles. Wonderful! For its skew simplicity, this is an insight right up there with the best.

Now let’s look at this relationship from a differently skew viewpoint: n2, as we know, is a square number, but any triangular number can be represented as half the product of adjacent integers: take the triangle that represents 10, for example, push it over:

and complete the rectangle that contains it:

our 10 is revealed as half the 4 x 5 rectangle.

What about the next triangular number, 15? The same push-over-and-complete-the-rectangle maneuver will give us that 15 is half of a 5 x 6 rectangle.

Rephrasing this algebraically instead of visually and arithmetically, the two successive triangular numbers are:

Add them, simplify, and mechanically find that of course

Where’s the insight, where’s the wonder, now? Who, you might rightly ask, cares?

The loss of meaning and flattening of effect, once a conjecture is incorporated into the formal body of mathematics, is yet another source, as well as an effect, of the “third person remote” style we spoke of earlier. Michael Atiyah called it “The Faustian Offer”:

Algebra is the offer made by the devil to the mathematician. The devil says: “I will give you this powerful machine, and it will answer any question you like. All you need to do is give me your soul: give up geometry and you will have this marvelous machine.” Nowadays you can think of it as a computer. When you pass over into algebraic calculation, essentially you stop thinking; you stop thinking geometrically, you stop thinking about the meaning. Fundamentally the purpose of algebra always was to produce a formula that one could put into a machine, turn a handle and get the answer. You took something that had a meaning; you converted it into a formula; and you got out the answer. In that process you do not need to think any more about what the different stages in the algebra correspond to in the geometry. You lose the insights. …

Most students of mathematics aren’t afflicted by world-weariness after discovery. Their question is why should they care at all about what they’ve been set to master. Does the heart beat faster because 7 × 8 = 56 and not 54? Do the trigonometric laws rival the laws of attraction in shaping our destinies? While any subject can be presented boringly (focusing in a history course on when, rather than why, was the War of the Roses), mathematics is especially vulnerable, because means are mistaken by so many of its purveyors for ends (master these times tables; now these trigonometric formulas), and because the ways to make it life-enhancing rather than life-denying often seem locked away from them. You might almost think that a soulless people were out to induct the rest of us into their seedpod society.

The most pernicious form of indifference, however, surfaces, as it does in O’Hanlon’s anecdote, after our best efforts are frustrated—and by something merely formal, no more than mechanical—something which, once you see it, will be dismissed with a disdainful “Of course!”

Most fortunately it happens [wrote David Hume], that since reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation, and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends, and when after three or fours hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find it in my heart to enter into them any farther.

When you get as tangled up in mathematics as Jarivanau in his string, when it all seems as aimless as a labyrinth, one solution is to do as Jarivanau did—and give it up. But we’re as likely to suppress our architectural instinct as we are to suppress our breathing. The other solution is to find again the thread that leads into the labyrinth and follow it to the center: follow it to why math matters, and why we cannot help but care.

We dismissed in chapter 3 the notion of a calling, but certainly some, for whom mathematics is irresistibly compelling, have thought that the compulsion came from beyond them. So Cantor, the father of set theory, wrote of a secret voice that spoke to and through him.