On the evening of April 26, 1936, in the swank dining room of the Victor Hugo Café in Hollywood, a mixed congregation of Jews, Catholics, and Popular Fronters paid upwards of $100 a plate to hear Prince Hubertus zu Löwenstein deliver a lecture entitled “Hitler’s War on Civilization.” A blueblood exile from Nazism, Prince Löwenstein had fled Germany one step ahead of a Gestapo hit squad. On a lecture tour of America to raise funds and consciousness, the Old World aristocrat was guaranteed a friendly reception from the local version of royalty.

As if drawn to the searchlights of a gala premiere, an A-list lineup of screen stars and studio power brokers converged to hear the fearless Catholic intellectual decry an ongoing terror and prophesy a future nightmare. “Reservations for the Lowenstein dinner-lecture avalanched the headquarters at late hour last night,” reported Daily Variety. “Many of the picture executives placed orders on a wholesale scale asking for tables of 12 and upwards.”1 Putting aside doctrinal differences and personal animosities, the town’s Irish Catholic elite (director John Ford, producer Winfield Sheehan, screenwriter Marc Connolly, Production Code head Joseph I. Breen, actors Pat O’ Brien and James Cagney, and, on the dais serving as honorary chairman, the Most Rev. John J. Cantwell, Bishop of Los Angeles) and a phalanx of name-brand Jewish moguls (Jack L. Warner, David O. Selznick, Irving Thalberg, and B. P. Schulberg) broke bread with a cadre of brazenly leftist artist-activists (including the organizers of the soiree, the agnostic wits Dorothy Parker and Donald Ogden Stewart, late of the Algonquin Round Table, currently prowling the gilded cage of the screenwriters stable).2 Dr. A. H. Giannini, founder of the Bank of America, was treasurer for the event. The diversity of the turnout testified to the consensus coalescing in Hollywood—that Nazism was not a distant menace but a clear and present danger, a realization that was not to dawn on the rest of America until the very eve of World War II.

The Nazis, said Löwenstein, had annihilated all that was good in German culture. “Everything that had made for the glory of Germany has been destroyed in the past three years,” he told the gathering. “The best actors and artists have been expelled. Approximately 1100 scholars and scientists have had to leave, only because they believed in the freedom of art, of thought, and of religion.” Jews were forbidden to buy milk for their children, and Catholics were jailed for keeping the faith. The jackboot crushing the Jews and the Catholics, he predicted, was but a preview of oppressions to come.3

Also speaking that night were Otto Katz, a communist agent operating in Hollywood under the nom de guerre Rudolf Breda; the actor Fredric March, winner of the Academy Award for Best Actor for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932); Bishop Cantwell; and screenwriter Stewart, who served as master of ceremonies. All urged a united front against Hitler. “We must organize to fight the Nazi invasion before Americans lose their constitutional liberties,” warned Stewart.4

The next week a blind item in Variety’s gossipy “Inside Stuff” column (doubtless fed to the paper by Stewart or Parker) flattered the diners with reports of just how far the voices in the Victor Hugo Café had echoed. In hush-hush tones devoid of definite articles, the trade paper confided:

Info around Hollywood studios is that Adolf Hitler is perturbed over tenor of speeches delivered at dinner to Prince zu Lowenstein of Bavaria in film colony a week ago, and that ban against American films into Germany may be ordered in retaliation. Undercover word that has reached various lots is that Hitler regime has been given transcript of the speeches and that drastic action may be expected. Major producing-distributing organizations are little disturbed, as under present German setup prohibiting money being taken out of country, American films are getting little or nothing as is.5

Actually, Hitler was busy presiding over the festivities attendant to the Reich’s annual labor celebration, a massive propaganda bash staged under the slogan “let’s enjoy life and make merry,” but the notion that in distant Berlin the all-powerful führer was piqued by a Hollywood confab must have delighted the organizers.

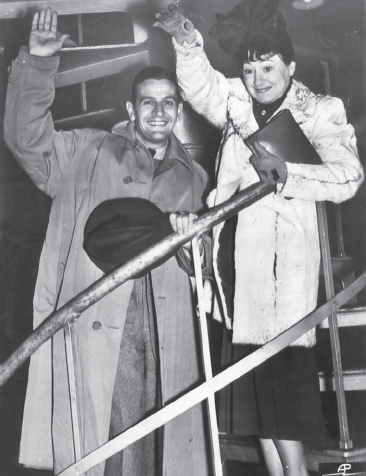

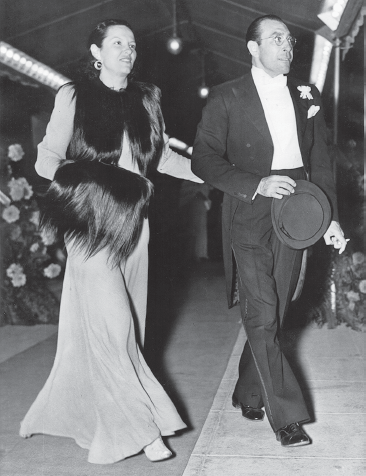

The catalyst for the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League: the Catholic nobleman and fearless anti-Nazi activist Hubertus zu Löwenstein and his wife Princess Helga Maria, arriving in New York for a lecture tour in 1938.

A hot ticket for stouthearted antifascists, the banquet for Prince Löwenstein was the first ripple in a wave of anti-Nazi activism that swept Hollywood in the late 1930s—a movement spearheaded by the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League for the Defense of American Democracy. From 1936 to 1939, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL) galvanized a stellar cast of mediagenic artists and media-savvy activists to oppose the rise of fascism overseas and advance the cause of social justice at home. Distinguished by star power in the ranks and proximity to the industrial plants of the major studios, HANL was a classic, if uniquely glamorous and auspiciously located, Popular Front group born of the Great Depression.

The Popular Front was the umbrella name for a broad coalition of New Deal Democrats, liberals without portfolio, socialists, and party-line communists, the last doing most of the drudge work of street-level organizing and office management. Bound together by a shared hatred of Nazism, it was an alliance of convenience made by strange bedfellows, a shotgun marriage of reformers and revolutionaries. Like dozens of other groups marching under the banner of anti-Nazism in the 1930s, HANL also agitated for the causes that warmed the hearts of a generation of militant men and women “of the Left,” as the phrase went: labor solidarity, civil rights, and, the best of all the good fights of the 1930s, the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War.

The actions initiated by HANL took a multitude of forms. Exercising skills honed during the bitter fights to organize below-the-line workers on the studio soundstages and the underpaid “schmucks with Underwoods” who banded together in the Screen Writers Guild in 1933, members pamphleteered, picketed, delivered lectures, mounted plays, staged screenings, collected funds, and proselytized at private parties and huge rallies. They published full-page advertisements in the trade press and tacked manifestos to studio bulletin boards. The publication of a newsletter, at first irregularly as the Anti-Nazi News, which later became News of the World, and then biweekly under the title Hollywood Now, spread the word and bucked up the faithful. Through the facilities of KFWB, the house radio station owned and operated by Warner Bros., HANL transmitted ideologically laced satire and strident exhortation to living rooms throughout Southern California. Blending high-society diversions, educational outreach, and street-level activism, the group aspired to be what it eventually became—the hectoring conscience of the motion picture industry on all matters pertaining to Nazism.

Of course, the logical means of production for HANL to seize was the one that employed its membership. Covertly at first, more boldly as the Nazis gobbled up territory and war clouds gathered, the members of the group conspired to inject anti-Nazi sentiments into Hollywood cinema. Given the political conservatism of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America and the moral policing of its censorship arm, the Production Code Administration, the Hollywood studio system proved the hardest medium to crack.

Not least, HANL pioneered the celebrity-centric, pseudo-eventful tactics that have since become commonplace for progressive causes that grip the social conscience of famous entertainers: the deployment of star power to publicize and validate a political agenda, with the body of the celebrity dangled as bait. While flashbulbs popped and cameras whirred, HANL stage-managed events where stars presided over rallies, orated from the podium, pled for donations, and signed petitions. If near enough to a famous face, a placard or slogan might avoid being cropped from a syndicated wirephoto.

In its heyday, HANL attracted a remarkably broad coalition of donors, volunteers, and signatories: not just the usual Popular Front spectrum of FDR New Dealers and Communist Party minions, but also a solid core of conservative Catholics and Jewish businessmen. All had good reason to oppose Nazism, a triple threat to ethnicity, religion, and trade. In 1937, at a celebration marking HANL’s year anniversary—a dinner, dance, and musical-variety show held in the proletarian digs of the Fiesta Room of the Ambassador Hotel—card-carriers and fellow travelers rubbed elbows with devout communicants and cutthroat capitalists. Though its membership roster peaked at around 4,200, HANL exerted an influence far beyond its formal subscription list.a Its rise, dominion, and fall offer a case study in the merging of media and politics, celebrity status and social activism, and the ultimately irreconcilable marriage between starry-eyed liberalism and hard-nosed communism in the 1930s.

The credit line for the idea that grew into the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League was shared by a mismatched pair of high-priced screenwriters, Donald Ogden Stewart and Dorothy Parker. He was a natural charmer, she a shy neurotic. Both spent the 1930s dividing their creative energies between art and activism, churning out screenplays for the studios and working pro bono for the Popular Front. Stewart was better paid; Parker made better copy.

Born in 1894 in Columbus, Ohio, the son of a judge, Donald Ogden Stewart was a blue-blooded red who saw no contradiction in living the good life while plotting the overthrow of his fellow plutocrats. Well-born and well-liked enough to be tapped as a member of Yale’s elite Skull and Bones Society, he deviated from his class trajectory sometime in 1936 to become a member of another secret society, the Communist Party. “Nor did I shed my new dinner jacket and distribute the pieces among the deserving poor,” he later recalled. “I saw no reason to stop dancing and enjoying the play of life.”6 Having written or collaborated on the screenplays for the posh MGM hits Dinner at Eight (1933) and The Barretts of Wimpole St. (1934), and, even while chief executive officer of HANL, burnishing his credentials with frothy soufflés such as The Prisoner of Zenda (1937), Marie Antoinette (1938), and Holiday (1938), Stewart boasted the kind of gold-plated screen credits that made the moguls overlook his pink politics.

By the time Dorothy Parker—née Rothschild—rented her byline to the movies, she was already famous for her whiplash wit and languid dissipation. Parker first came to Hollywood (a place where, she couldn’t resist saying, “the streets are paved with Goldwyn”) in the early sound era, during the great migration of New York wordsmiths drawn by the promise of $2,000-a-week salaries for remedial dialogue.7 In 1933 she married the actor Alan Campbell, and the couple accepted a contract with Paramount to collaborate on screenplays; their most notable shared credit was A Star Is Born (1937), a close-to-home melodrama about a wife whose artistic talent outshines her husband’s. A Jazz Age avatar staggering uncertainly into the harsh glare of the 1930s, she was destined to be remembered as much for the bon mots she uttered as for the words she put to paper. Too quotable for her own good, she used the smart-mouthed dame persona as both a shield for her social anxieties and a weapon in her tireless political activism.

The blue-blooded red: screenwriter Donald Ogden Stewart, cofounder of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, with his wife and comrade-in-arms, Ella Winter, 1939.

Writers with a social conscience and a taste for the high life, Parker and Stewart made an effective tag-team, with the gregarious Stewart assuming duties in the spotlight and the anxiety-ridden Parker closing the deals for donations and commitments one-on-one. Before the dinner at the Victor Hugo, the pair hosted a cocktail party for Löwenstein at Parker and Campbell’s house on Canyon Drive in Beverly Hills. It was there, over drinks, that the idea for a permanent Hollywood-based anti-Nazi action group took shape.

The notion had been bandied about in Hollywood for some time. In New York, the well-funded and well-connected Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League to Champion Human Rights had been operating since 1933 under the dynamic leadership of lawyer Samuel Untermyer. A more direct spur to action—namely, orders from on high—came in 1935, when the Comintern, the Moscow-based bureau tasked with coordinating the activities of Communist Parties worldwide, sent out word to party apparatchiks to cooperate with socialists, liberals, and other left-wing groups in a broad-based “popular front” against fascism.

Artists as activists: screenwriter-wit Dorothy Parker and her husband, screenwriter Alan Campbell, returning from a trip to war-ravaged Spain, October 22, 1937.

Over cocktails at the Campbell-Parkers’, at the Löwenstein dinner, and in the glow of victory the next morning, the dream of a local anti-Nazi group coalesced into a practical plan of action. The congenial, energetic, and high-profile Stewart was the natural choice for president; he modestly claimed to be merely a figurehead, but he was always a hands-on manager. On June 8, 1936, the group was formally incorporated as the Hollywood League Against Nazism; on September 28, 1936, it became the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League for the Defense of American Democracy.8

Behind the scenes and out of the headlines, a crucial catalyst was Otto Katz, a communist agent who played more parts than any of the actors he circulated among at the Victor Hugo Café. It was he who handled the details for Löwenstein’s visit to Hollywood and he who revolutionized left-wing fund-raising by introducing Moscow agendas to Hollywood checkbooks. Silky smooth and coolly mysterious, Katz had been a well-known actor in both the experimental theater and street politics of Weimar Berlin. He first came to America in 1935 to raise money for the anti-Nazi German underground.

By the time Katz hit Hollywood, he had perfected a line of patter that was a siren call to a community who knew mystery, danger, and espionage only from screenplays. Theodore Draper, the historian of American communism who observed Katz work his magic, described him as “the international Communist huckster par excellence.” Before Katz had his entrepreneurial brainstorm, recalled Draper, “the American Communists had never thought of the movie capital as a party mint.” Katz was proud to have corrected the oversight. “Columbus discovered America,” he bragged, “and I discovered Hollywood.”9 (Katz had the con man’s knack of being different things to different people: on the night of Prince Löwenstein’s talk, Stewart recalled that Katz delivered a communist spiel that so outraged Bishop Cantwell that His Excellency bolted the dais. Löwenstein recalled that, on the contrary, Katz charmed the bishop by genuflecting and solemnly kissing his ring.) “Katz ‘sold’ communism to the wealthy Hollywood magnates by working on their bad social consciences until they were cringing with contrition,” observed a bemused Prince Löwenstein years later. “The complete religious and metaphysical desert in the minds of many in the motion picture colony made [his] game easier.”10

HANL’s first anti-Nazi initiative was a suitably literary gesture, a protest against an article by William Stidger in Liberty magazine posing the counterintuitive question “Hitler Planning to Be Kind to the Jews?” Answering in the negative, the group dictated an angry telegram to the editor:

WE PROTEST THE INSIDIOUS PRO NAZI PROPAGANDA CONTAINED IN YOUR CURRENT ISSUE ENTITLED HITLER PLANNING TO BE KIND TO JEWS STOP THE RECORD OF HITLERS BROKEN PROMISES INDICATES THE COMPLETE UNTRUTH OF THE IMPLICATIONS MADE BY YOUR WILLIAM STIDGER STOP THERE CAN BE NO COMPROMISE WITH THE AMERICAN PRINCIPLES OF RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL FREEDOM (SIGNED) HOLLYWOOD LEAGUE AGAINST NAZISMb

The name of the League had not yet congealed, but the signatories represented some of the core activists: Stewart and Parker; screenwriter Edwin Justus Mayer, a yeoman member of the Screen Writers Guild and emphatically no relation to Louis B.; the actress Gloria Stuart; Charles J. Katz, a prominent labor attorney active in progressive causes; playwright Samson Raphaelson, author of The Jazz Singer (1927); director Frank Tuttle, best known for guiding radio stars like Bing Crosby and Jack Benny through lighthearted musical comedies at Paramount; the husband-and-wife team of screenwriter Herbert J. Biberman and actress Gale Sondergaard, Hollywood’s premiere Communist Party power couple of the 1930s; the gravel-voiced character actor Lionel Stander; Parker’s husband, screenwriter Alan Campbell; the vaudeville and radio performers Ray Mayer and Edith Evans; screenwriters Viola Brothers Shore, Arthur Sheekman, and Hy Kraft; and writer Felice Paramore.11 A chastened Liberty printed the protest telegram in its next issue and published an article attacking Hitler soon afterward.

On July 24, 1936, the group held its first public coming-out party at the Wilshire Ebell Theater in midtown Los Angeles. Some 500 artist-activists gathered to hear Prince Löwenstein, back for a return engagement, and his wife, the Princess Helga Maria. The meeting was presided over by producer Lester Cowan, a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who joked about Hitler’s recent categorization of the Japanese as “honorary Aryans.” The radio and screen star Eddie Cantor decried the distribution of hate-mongering Nazi propaganda smuggled stateside and repeated a comment he made to the press when asked about the banning of his films in Nazi Germany. “I’m glad it happened because I don’t want to make people laugh that make people cry.” The Löwensteins recounted their brushes with death in the new Germany and sounded the alarm for America. Fredric March introduced the Prince; Gloria Stuart introduced the Princess.12

Buoyed by the enthusiastic turnout, the League moved on to bigger things—protesting American participation in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, exposing subversive pro-Nazi outfits such as the Silver Shirts and the German American Bund, and, on October 20, 1936, inaugurating its house organ, the Anti-Nazi News: A Journal in Defense of American Democracy (first headline: “Hollywood Fights Nazism”). The paper’s main beat was the activism of its readership: the lectures, rallies, exhibits, and shows mounted to expose the Nazi threat at home and abroad.

Being the only place in Hollywood where writers called the shots, HANL often made its political points through public rhetoric and literary discourse. It wallowed in talk, telegramming, sloganeering, speechifying, writing, the circulation of petitions, the passing of resolutions, and the issuing of manifestos. A gabfest tailor-made for the group was the motion picture session of the Western Writers Congress, held in San Francisco on November 15, 1936. Convened to ponder the problem of “the writer in relation to contemporary social problems,” the writers workshop-cum-political rally saw Hollywood’s highly paid screenwriters rubbing elbows with hardscrabble scribblers lucky to get piecework from the Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. The writers’ trade not being a classless society, disgruntled scriveners from the floor railed at the pampered Hollywood bourgeoisie as “fascistic, infantile, and anti-social” and attacked guns-for-hire like Stewart and Parker as “literary prostitutes engaged in passing the buck.” For once beating Parker to a punchline, Stewart—a richly rewarded screenwriter who still considered himself underpaid—snapped back, “Passing what buck and to whom?” Parker tried to mollify the crowd by insisting that “whether or not the public got more honest pictures there was no question of the Hollywood writers ever quitting fighting for them.”13

The most popular living-room medium of the day provided the loudest megaphone for HANL rhetoric. On November 16, 1936, the group set up a committee—chaired by radio personality Alfred Leonard and including Lester Cowan, set designer Harry J. Zutto, and songwriter Jay Gorney—to penetrate the radio airwaves. “Hitler and his head propagandist Goebbels … are adepts at the use of radio in their efforts to fool all the people all the time,” HANL reasoned. “We will try to beat them at their own game. We will try to prove that facts can be just as colorful as fraud and fiction over the air.”14

HANL turned to the radio dial “to reach those circles of American society which are most directly exposed to PRO-NAZI PROPAGANDA and who—on the other hand—can not be reached by the primarily intellectual appeal of the printed word.” Given the susceptibility of the bovine masses to Nazi trickery, “all efforts to counter-act the influence of Nazi-propaganda or to make people immune against it must have a dual purpose: first, to gain the individual’s sympathy for what he is about to learn and second, to present the material in a way which reaches his or her personal interest and at the same time supplies the necessary facts to sustain the first emotional reaction.”15 Ironically, or not, HANL’s radio propagandists embraced the same “hypodermic needle” theory of mass communications propounded by Joseph Goebbels: inject the message into mass consciousness through repetition, simplicity, and raw emotion.

Debuting on February 20, 1937, and transmitted over KFWB every Saturday evening from 7:30 to 8:00, HANL’s “professionally planned and produced program” of anti-Nazi agitprop took possession of a small piece of the dial, “radiating from the Hollywood broadcast towers of KFWB into hundreds of thousands of homes, enlightening, educating, warning.” Donald Ogden Stewart served as moderator-host for the premiere episode, a series of dramatic monologues from a diverse range of Americans united in their opposition to Hitler: projectionist Don Thomas Freiling spoke for the American Catholic; the African American actor-activist Jay Moss for the American Negro; screenwriter Viola Brothers Shore for the American woman; and the exiled author Erich Rix for the German anti-Nazi. A regular segment featured a pair of popular characters created by Stewart and transplanted to the Reich, “Mr. and Mrs. Haddock in Germany,” played by Ray and Edith Mayer. HANL’s sympathetic patrons at Warner Bros. also made the facilities of KFWB available for screenwriter Hy Kraft to put an anti-Nazi spin to the news of the day, Thursdays from 9:15 to 9:30 p.m. PST.

Making the agitprop easier to digest was the peppy tonic of commercial radio-speak. “So remember Saturdays 7:30 to 8:00, a good day, a good hour, and the best possible cause—the cause of genuine democracy against its one real enemy, Nazi fascism,” chirped the advertising. “Tune in on the liveliest trend of the times. We’ll be with you at 95 on the dial, 7:30 on the clock, every Saturday—and our slogan is ‘Unheil Hitler!’”16

Besides spreading the anti-Nazi word, the radio shows were a boon to recruitment. “Have you noticed all those new faces around Hollywood Anti-Nazi League meetings lately?” asked Hollywood Now. “They are there largely because of the League’s radio programs, which are bringing in more new members than any other series the League has ever offered.”17

On the morning of April 16, 1937, HANL awoke to the first concrete evidence that its agitation had struck a nerve—the trashing and burglarizing of its offices at 6912 Hollywood Blvd. “It is apparent, as a result of this latest indication of Nazi vandalism, that the followers of Adolf Hitler are desperately trying to cover their activities in our country,” reported Hollywood Now, trying not to sound too thrilled about the publicity windfall. “It becomes increasingly necessary, therefore, to intensify the work—of anti Nazis toward ridding the American scene of the evil influence of these swastika-branded anti-democratic leaders and their vandal gangs.”18

The local police did not leap into action to run the perpetrators to ground. Captain J. J. Jones of the Hollywood Detective Bureau refused to fret over what he considered an intramural squabble. “You are a political organization,” Jones told HANL, “and if another political organization doesn’t like you—so what?”19

Six months later, no thanks to Captain Jones, the culprit was caught, and he had a familiar Hollywood surname—Leopold McLaglen, brother of the actor Victor McLaglen, winner of the Academy Award for Best Actor in John Ford’s The Informer (1935).c McLaglen was arrested in connection with an extortion plot targeting millionaire socialite Philip M. Chancellor, who had employed him as his jujitsu instructor. According to court testimony by Chancellor’s “chauffeur-secretary,” McLaglen had vandalized the offices at the behest of Chancellor and then tried to blackmail Chancellor with the threat of exposure. Asked on the stand if he had anything to do with the crime, McLaglen toyed with his monocle, looked at his shoes, and played coy. “Well, now, I want you to understand, anything I did against anyone was at the direction of Mr. Chancellor.”20 In lieu of jail time, McLaglen was deported to England. Brother Victor paid for the boat ticket.21

The trashing of its headquarters only accelerated the forward momentum of the group—confirming its influence, increasing its membership. In April 1938, HANL moved to more commodious quarters at 6513 Hollywood Blvd., a suite of four rooms “where the multiplying activities of the League will be carried on with greater efficiency.”22 On June 4, 1938, when HANL marked its second anniversary, the news was all upbeat. “Launched by scarcely more than a dozen Hollywood artists, it has had a phenomenal growth,” boasted a self-promotion. “Its membership is now at its highest point—5000 men and women united in a movement to stop Nazism and protect American democracy. The activities of the League have been manifold—a constant stream of meetings, rallies, radio broadcasts, benefits, educational campaigns.”23

The talent on stage and the executives sitting at the tables during HANL’s banquets and benefit performances confirmed the group’s status as the premier political action committee in Hollywood, a wired network of insiders, membership in which conferred social cachet and political influence. To commemorate the second anniversary, KFWB provided air-time for a special program featuring Parker, Campbell, and other HANL stalwarts. “There can be no doubt that the League is more active than any other local organization in opposition to the doctrines and persecutive practices of power-crazed European dictators and in its stand against the spread of these Nazi principles in democratic America,” wrote Ivan Spear in the trade weekly Box Office. “In fact, it is doubtful that there is another organization anywhere in the nation which can point to a more impressive record of activity.”24

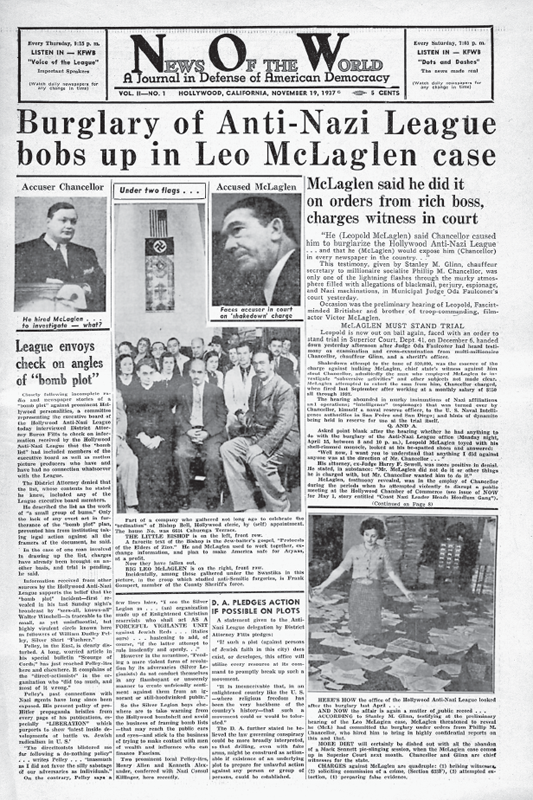

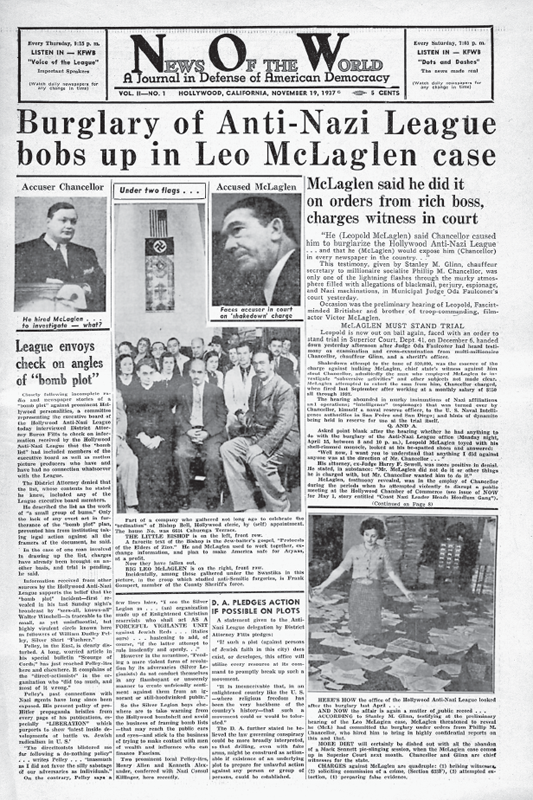

Rallying the faithful: a front page from News of the World, later renamed Hollywood Now, the biweekly call-to-arms published by the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University).

President Roosevelt, if not Hitler, was taking notice of HANL’s New Deal–friendly work. On October 19, 1938, Harold L. Ickes, FDR’s Secretary of the Interior, arrived in Hollywood to speak at a mass meeting in the Shrine Auditorium, sponsored by HANL, the Hollywood Council for Democracy, and the Motion Picture Democratic Committee (left-wing Hollywood shared the Popular Front penchant for generating like-minded political groups with overlapping memberships). Before the main event, Ickes was honored at a luncheon at Twentieth Century-Fox. Flanked by Fox’s Darryl F. Zanuck and MGM’s Louis B. Mayer, FDR’s emissary played to the crowd with a fervent defense of freedom of speech and screen. “There are two industries in the U.S. that every day and every night must work for, stand for, and fight for our liberties,” Ickes declared. “They are the movie industry and the newspapers. Once we let anyone dictate to the newspapers or the film industry what they can or can’t do, we are licked.”25

At the Shrine Auditorium that night, speaking on “The Crisis of Democracy,” Ickes singled out the members of the motion picture industry for their fight against the “spirit of intolerance and oppression that is now a threatening storm on the far horizon.” As Hollywood’s liberal elite beamed, the audience adopted a resolution calling upon FDR to lift the embargo against Loyalist Spain and to convene “a genuine peace conference to plan for collective defense of democracy throughout the world.” Afterward, Donald Ogden Stewart called the evening “one of the happiest and proudest moments in the Hollywood liberal movement.”26

But if conferences, rallies, and radio shows kept the ranks busy and made everyone feel good, HANL could not boast of a single motion picture that bore, undeniably, the imprint of anti-Nazism. Screenwriter and HANL fixture John Bright resigned himself to the fact that while “Hollywood is not a factory for Fascism,” as long as the public demanded films that “dilute and distort life, Hollywood will continue to do just that.”27 Bright was speaking from personal experience: with his partner Robert Trasker he had spent the last year laboring on barely-above-B-picture froth such as Here Comes Trouble (1936) and Girl of the Ozarks (1936). From the evidence on screen, the “Hollywood” in the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League stood only for the location of the office. Unable to harness the power of the Hollywood feature film, the group concentrated on what powered the entertainment machine—the motion picture star.

The body of the Hollywood star had first been drafted into national service during the Great War. Attracting crowds, selling war bonds, and lending legitimacy to the crusade against the bloodthirsty Kaiser and the bestial Hun, the celestial trio of Charles Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford marched at the head of the martial parade orchestrated by the Committee for Public Information, the first federal propaganda agency in American history. In film clips, the Little Tramp bonked the Kaiser on the noggin with a wooden mallet and Doug and Little Mary, America’s heartthrob and America’s sweetheart, implored moviegoers, in intertitles, to enlist in the great crusade Over There.

Yet except for shilling for the War to End All Wars, the Hollywood star was too valuable a commodity to squander on idealistic ventures with no return on investment. Republicans and Democrats—for that matter, Ku Klux Klansman and communists—all went to the movies. To alienate any portion of the moviegoing public, no matter how small or eccentric, was to shorten the line at the ticket window. The controversial issues and causes célèbres of the 1920s—immigration restriction, labor strikes, the execution of the anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti—were disputed without Hollywood stars manning the picket lines. It was as if the silent screen had muted the exercise of free speech.

Of course, celebrity endorsement of commercial products had been an ancillary gold mine since the first screen face was recognizable from a billboard. Also, a heartfelt solicitation for a charitable cause made from the stage or in a newsreel clip was an unassailable way to trade on stardom. The March of Dimes, the campaign founded in 1938 to eradicate the blight of polio, presided over by its most famous victim, FDR, attracted perhaps the biggest cast of entertainers performing gratis on the side of the angels. HANL stalwart Eddie Cantor coined the name for the charity, a pun on the popular screen magazine, the March of Time.

Aside from charities, however, studio moguls and matinee idols alike minded their show business.28 Stars were clothes horses who did not wear their politics on their sleeves. As far as the public and the fan magazines knew, not a thought occupied their pretty little heads.d

It took the crisis of the Great Depression and the charisma of FDR to push Hollywood out of the wings and onto the political stage. In 1932, publicly and vocally, motion picture stars, top-rank directors, screenwriters, and even studio executives enlisted in the Democratic campaign, including the biggest name of all, the multimedia superstar Will Rogers. If not the first, Rogers was the most prominent of the famous entertainers who ventured from humanitarian causes into political waters. The beloved cowboy-philosopher was unique, however, a partisan commentator who somehow managed to rise above partisanship, whose disarming manner took the edge off his contempt for Herbert Hoover and his advocacy for FDR’s New Deal programs. “I’m not a member of any organized political party,” he famously cracked. “I’m a Democrat.”

In Hollywood, Rogers was not alone. On September 24, 1932, a stellar lineup of Democrat-minded motion picture personnel took over the Olympic Stadium in Los Angeles for a huge pageant, electoral parade, and sports show that drew some 65,000 people to what was both a fund-raiser for the Motion Picture Relief Fund and a pep rally for FDR. Winfield Sheehan of Fox and Jack Warner of Warner Bros. handled the arrangements, with Will Rogers and actor Conrad Nagel on hand to host the event. FDR spoke about his own motion picture experience—in the newsreels—and praised the industry for its generosity to so many worthy causes, leaving his own unspoken. Never before, joked Will Rogers, had so many people paid to see a politician. Hollywood’s minority Republican caucus—Louis B. Mayer and David O. Selznick—stayed away.29

Motion picture artists were also caught up in the rampant politicization of the arts in the 1930s, a polemicist streak crystallized by the social realist movements in literature and the arise-and-sing-alongs presented on the New York stage. Incubated by the Group Theatre in New York, an ensemble of fourth-wall-breaking artist-activists founded in 1935, and the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal make-work program for indigent players, a generation of playwrights and thespians acted out a Popular Front platform before live audiences. After performing in productions that blended the adrenaline rush of putting on a show with the righteous fervor of consciousness-raising, little wonder that many in the cast took their lines to heart and recited the dialogue off stage. When the actors moved west from New York, they brought along more than their elocution and stagecraft.

Locally too, Hollywood actors were finding it hard to keep the destitution beyond the studio gates at bay. In 1936 a bitter strike by lettuce workers in the Salinas Valley in central California attracted the sympathetic support of a wide circle of actors from across the political spectrum (James Cagney, Eddie Cantor, Gary Cooper, and Fredric March) who each donated $1,000 to a cause that most might have seen more as a charitable contribution than a blow for labor solidarity. “Performers and others who contributed in collection to help sufferers from [the] Salinas lettuce strike are plenty burned up because [a] section of [the] press is trying to tag them as red contributors,” reported Daily Variety. “Real dope is that the contributors gave their dough to feed hungry little children and women whose fathers and husbands are unable to buy food or provide shelter because of the strike.”30

The Daily Worker, the official newspaper of the Communist Party USA, noticed the sensibility turnabout and welcomed the new recruits to the ranks. Hollywood communists “will find immediate support in the dynamic progressive movement that has developed on the West Coast, where great numbers of progressives are currently rousing mass sentiment for aid to Spain and China and organizing all liberals into a solid front against Fascism at home and abroad,” wrote the party organ, before blowing the cover of one of its front groups. “The Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, for example, in its fight for democracy and peace, has stirred the imagination of the West Coast progressives.” Not that the working-man’s paper of record was going soft on capitalism. Elsewhere, of course, “the motion picture industry reflects the vicious anti-democratic offensive being conducted by finance capital in every part of the world today.”31

The Hollywood Anti-Nazi League encouraged and exploited the rising political consciousness of the indigenous star power. In casting actors as activists, it was a farsighted pioneer.

Neither puppets nor poseurs, the first stars to stick their necks out and risk career suicide tended to know whereof they spoke. Having worked and hung out with the playwrights and theater directors energized by the ethos of art-for-Marx’s-sake, actors such as Melvyn Douglas, Fredric March, Gale Sondergaard, and John Garfield did not have to read their lines from a script. Before his popular radio show went live over the airwaves, Eddie Cantor warmed up the studio audience with anti-Nazi patter.32 United Artists founder and silent screen superstar Mary Pickford found her voice in broadsides against Nazism—calling on the nation’s women to back a strong national defense program, denouncing Hitler as “mad as a March hare” and predicting, “When he finishes with the Jews he will turn to the Catholic Church, then to the Protestants” and finally “to the country that has the most gold.”33

Then as now, the attraction of rich and beautiful artists to a doctrine of wealth redistribution in a classless society inspired a good deal of psycho-rumination. Did a profession whose practitioners channeled vicarious emotions feel the pain of the poor and dispossessed with special intensity? Had the emotional internalization of the Stanislavsky method wrought a permanent change of heart? Or was it something as simple as guilt for making so much money for so little labor in so bleak an economy?

Perhaps the best explanation for the affinity of motion picture artists—actors and screenwriters especially—to an ideology counter to their economic self-interest was the respectful hearing accorded them by the Communist Party USA. In Leninist doctrine, the artist stood among the vanguard elite, a cadre whose shining example would lead the benighted proletariat into the dawn of revolutionary enlightenment. In the eyes of the Hollywood moguls, actors and writers were hired hands and piecework drones, given their lines to speak and assignments to write, patted on the head if obedient, kicked in the ribs if recalcitrant. The communists and the Popular Front were starstruck, but not like the fans who swooned over the covers of fan magazines. The artist was the antenna of the revolutionary race—so much the better if he or she was a magnet for publicity and a donor with deep pockets.

In the 1930s, seeing stars selling something besides cosmetics, cigarettes, or themselves was a novel sight. “Actors are entertainers who make their living from the public, and I don’t think the public is interested in their political, racial, or religious affiliation,” harrumphed gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, a reliable mouthpiece for studio opinion.34 Drunken scuffles, moral turpitude, and temper tantrums were familiar foibles that the studio’s publicity departments had long experience covering up by greasing the palms of the local cops and newshounds. Stars who sought out publicity for ambulances for Spain and boycotts of Nazi goods were a new kind of problem children. “The names of 26 Hollywood movie stars, directors, and screenwriters, which usually appear only in bright lights and on movie house billboards, have been painted across the sides of two new ambulances soon to be shipped to Loyalist Spain,” crowed the Daily Worker.35

For the studios that underwrote the careers of the stars and expected a steady return on the investment, the off-the-reservation performances were not just novel but troubling. “Following urgent requests from their foreign departments, major companies will take action soon to prevent players from taking part in political movements, and lending use of their names to campaigns on which national and international opinion is divided,” the Hollywood Reporter announced in 1937. “Open anti-Nazi and anti-fascist stand of Hollywood stars has caused box office losses to their companies, not only in Germany and Italy, but in other countries, where these political principles are bitter issues. Since Hollywood depends on foreign territory for 40 percent of its grosses, the ‘isms’ publicly praised or denounced by film personalities may reach the point of bringing serious loss.” To contain the damage, the studios threatened to insert political clauses into the contracts of uppity actors “similar to the morality clauses now in most deals.” Said one executive: “The players are under contract to us and as such must obey us.”36

Reporters from the trade press tended to agree with the studio bosses that the contract player was an indentured servant. “The Hollywood stars who are so earnest—and so public—in their sympathies for anti-Nazism, anti-fascism and other antis, are doing more harm to themselves than good to the causes they sponsor,” insisted columnist Frank Pope in the Hollywood Reporter. “How long will it be before the unpopularity which they certainly will gather, in some countries, will begin to affect their screen standing and, later perhaps, their salaries?” The prudent course was to shut up and count their blessings. “The private opinions and beliefs held by picture players are their own and no one has the right to say that they shall not hold such opinions,” conceded Pope. “But when they make those opinions public, to the detriment of their own screen value and therefore, to the detriment of the company that employs them, that is something else again. In such cases, we believe, the industry has the right to object.”37 Like the antique furniture and period costumes stored in the studio warehouses, the star was company property, part of the inventory.

Actors were not simply ventriloquist’s dummies, responded the Motion Picture Artists Committee, another glitzy Popular Front group composed exclusively of movie personnel but basically an offshoot of HANL. Neither the studio front office nor the trade press had any right to restrict “the exercise by Hollywood stars of their constitutional right of free speech, because of the possible effect [on motion picture box office] in countries where free speech is denied.” The committee scoffed at a mentality so devoted to commerce it was repulsed by altruism. “It may be that the act of signing one’s name to an ambulance in order to send medical supplies to relieve the agony of Spanish men, women, and children is ‘bad’ publicity—whereas the endorsement of a new kind of lipstick or the ‘reported engagement’ to a famous ‘socialite’ is a blessing greatly to be desired.”38

Whether tagged as useful idiots or ingrates, actors who got the left-wing religion made inviting targets for cynics and red-baiters. Wags delighted in jeering at (variously) the “champagne Communists,” “swimming pool reds,” “white tie and tail anti-Nazi movement,” and “cocktail party activists” who linked arms with the scruffy proletariat to croon a chorus of the “Internationale” before being chauffeured back to the mansion in Beverly Hills. Dunces at best, traitors at worst, the slogan-spouting stars were pretty boys and girls who got fat off the fruits of capitalist America and then bit the hand that fed them. It was one thing for stagehands or electricians to cozy up to the communists, but flush screenwriters and pampered stars?

Beneath the smirks, darker insinuations were muttered: that Hollywood’s political naïfs were being jerked around by Soviet puppeteers. “While we would not for an instant question the sincerity of the members of the anti-Nazi league and of the Motion Picture Artists Committee, there is always the possibility that, somewhere in the background, are clever manipulators who are exploiting the Hollywood names for the value they bring to a cause,” suggested Frank Pope.39 That the actor might be pulling his or her own strings was a notion too absurd to contemplate.

For HANL, the publicity windfalls and $1,000 checks compensated for the snickers and slanders. Besides, life as a Hollywood anti-Nazi wasn’t all Marxist study groups and Soviet newsreels, what with annual summer dances at the Hillcrest Country Club, swimming parties and picnics at the Malibu beach house of the high-powered agent Mrs. Adeline Jaffe Schulberg, and black-tie fund-raisers at the most fashionable place to eat and be seen—Chasen’s. Whether attending the West Coast premiere of the Broadway hit Pins and Needles (1937), a musical revue sponsored by organized labor (sample lyric: “If a radical idea / gives you nervous diarrhea / call it un-American”), or cheering on Joris Ivens’s The Spanish Earth (1937), a documentary paean to the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War, the membership was ready to man the barricades with a night out on the town in the service of uplifting left-wing entertainment.40

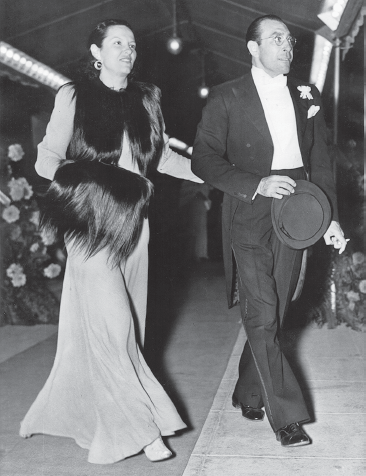

“White tie and tail activism”: the husband-and-wife team of screenwriter Herbert J. Biberman and actress Gale Sondergaard, animating members of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, at the premiere of Warner Bros.’ The Life of Emile Zola (1937) at the Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles, September 9, 1937. “She’s wearing a novel jacket of black monkey fur, with long velvet gloves, and muff of the fur,” noted the original International News Photo caption.

The local anti-Nazi ensemble was also—in good Hollywood-musical fashion—ready to pitch in and put on a show. In 1938 the Motion Picture Artists Committee mounted a madcap “political cabaret” called Sticks and Stones, a series of sketches and blackouts “more or less on the racy and raucous side,” with a deep talent pool of performers (John Garfield, Gale Sondergaard, Milton Berle) and composers (Marc Blitzstein, Ira Gershwin, Johnny Green, Yip Harburg). At $5 a head, “a varied assortment of sophisticates, intellectuals, intelligentsia, and just plain Hollywood folk” laughed at twenty-three rapid-fire sketches lampooning fascism at home and overseas.41 A smash hit—in political-theater terms—the show also generated a pop anthem of sorts, “It Can Happen Over There, But It Can’t Happen Here.”

Not least, and even without the garnish of political relevance, HANL laid out a sumptuous intellectual feast for its membership. In tandem with the Associated Film Audiences, yet another film-minded Popular Front group, it sponsored talks from industry notables. A series of eight lectures on “How Motion Pictures Are Made” served to tighten solidarity while providing a congenial forum for career networking. The program featured a stellar cast of experts, including actor-director Irving Pichel on “The History of Motion Picture Production,” exiled German director Fritz Lang on “The Influence of Foreign Theater and Technique,” screenwriter Viola Brothers Shore on “The Screen’s Interpretation of Controversial Subjects,” Donald Ogden Stewart on “Censorship,” and Walter Wanger, who would know, on “The Troubles of a Producer.”42

As the 1930s wore on and the menace from Nazism grew more palpable, HANL felt the wind at its back. The rallies got bigger, the soirees more glamorous, and the rush to sit on the dais more competitive. On November 18, 1938, in the wake of Kristallnacht (the Reich-wide wave of antisemitic violence launched on November 9–10) over 3,500 motion picture industry personnel packed a mass “Quarantine Hitler” rally at Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles. Actor John Garfield, director Frank Capra, and Donald Ogden Stewart made impassioned speeches against the pogrom. Bringing the crowd to its feet, Garfield called for a militant campaign to fight “the rising wave of intolerance both in this country and abroad.” Supportive messages were read from exiled German author Thomas Mann, who said that America must be the “strong unswerving protectress of the good and the godlike in man,” and actress Joan Crawford, who “would have considered it an honor to have been present” had not her busy shooting schedule detained her.43 The crowd unanimously voted to send a telegram, signed by dozens of prominent Hollywood personalities, urging President Roosevelt to “quarantine the aggressor nations.”44

The League needed all the celebrity firepower it could muster. With the conspicuous exception of the left-leaning trade weekly Box Office, the mainstream press, both trade and civilian, often buried or ignored HANL’s activities. The Los Angeles newspapers—always eager to cover gala premieres and stars hobnobbing in nightclubs—found HANL news unfit to print. “Certainly the most bigoted editor, and even laymen, must have recognized the news value of such a gathering,” wrote Ivan Spear, of the mysterious silence that greeted the massive, star-studded “Quarantine Hitler” rally. “The metropolitan press completely ignored the assemblage—both before and after.”45 The only attention from another trade press source came in the form of a lecture. “Sincere but mistaken zeal,” responded Variety, editorially, fretting over the siphoning off of even the smallest percentage of pro-German or anti-interventionist moviegoers. “There has been enough talk, enough protest meetings, enough name calling in the press and on the air” and “further concerted agitation can bring on the alienation of the sympathy of this country.”46

In fact, HANL was earning the sympathy rather than the alienation of most of the country. By late 1938, anti-Nazism was far more popular than pro-Nazism, and by saying so, noted the Motion Picture Artists Committee, “the stars are identifying themselves with the great mass of the American people and the democratic peoples throughout the world.”47

Shortly after the Shrine Auditorium rally, some sixty members of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League met at the home of Edward G. Robinson to plan further action. The meeting was presided over by Melvyn Douglas, and the marquee names in attendance gave proof of the group’s wiring into Hollywood’s brightest star voltage: actors Bette Davis, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Paul Muni, Miriam Hopkins, and Robert Montgomery; directors John Ford and Anatole Litvak; producers Jack L. Warner and Walter Wanger; and, the éminence grise, Carl Laemmle. The gathering outlined a petition for an embargo of German goods. Douglas emphasized the “spontaneous” grassroots origins of the idea. “The President cannot order an embargo because this is not a dictatorship. He has done all he can in the matter.” Public opinion, insisted Douglas, was the real force.48

The meeting resulted in HANL’s most elaborate star-studded publicity-political stunt—the Declaration of Democratic Independence, modeled after the American original. “On July 4, 1776, the people of this country determined to submit no longer to an implacable despot,” read the preamble to HANL’s version. “Today, a new tyranny has arisen to challenge democracy’s heritage. The leaders of Nazi Germany openly threaten national security, defy international decency, and proclaim the end of the democratic world.” Adopting the Jeffersonian cadences of the original, the document lists a long train of abuses:

Hitler and his Nazi dictatorship have attacked the religions of the world and substituted paganism in their stead.

They have abolished freedom of speech, press, and assemblage, imposing their will upon 75,000,000 people and preparing a similar imposition of will upon all mankind.

They have brought chaos and disunity into sovereign nations and then seized and dismembered them.

They have degraded women to the function of producing soldiers.

Though the undersigned did not pledge their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor, the petition ends with a call that “all economic connections between the people of the United States and Germany be totally severed until such time as Germany is willing to re-enter the family of nations in accordance with the humane principles of international law and universal freedom.”49

On December 21, 1938, a roster of marquee names dubbed “the Committee of 56” staged a photogenic signing of the petition, “fifty-six” being the number of the signers of the original Declaration of Independence. Seventeen stars and artists posed for the cameras in a variety of different configurations, among them such famous faces as Melvyn Douglas, Henry Fonda, Myrna Loy, Groucho Marx, Paul Muni, Claude Rains, Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, and Gale Sondergaard. The first HANL-sponsored pseudo-event to be covered by the newsreels, the signing was featured in Fox Movietone, Universal Newsreel, and MGM’s News of the Day. Timed with the release of the newsreels, copies of the document were circulated in fifty-six sections of the United States.50 The ever-supportive Box Office lauded the Declaration of Democratic Independence as “a milestone in the progress of Hollywood liberalism” and “perhaps the strongest document ever made public by any group identified with the industry.”51

“A milestone in the progress of Hollywood liberalism”: representatives from the star-studded “Committee of 56” sign the Declaration of Democratic Independence, December 21, 1938. From left to right, standing: Claude Rains, Paul Muni, Edward G. Robinson, Arthur Hornblow Jr., Helen Gahagan, John Garfield, Gloria Stuart, James Cagney, Groucho Marx, Aline MacMahon, Henry Fonda, Gale Sondergaard. Sitting: Myrna Loy, Melvyn Douglas, and Carl Laemmle. (Courtesy Getty Images)

Being experts in the politics of celebrity, HANL’s leadership understood that the publicity machine hummed along on either alternate or direct currents. The flip side of fame was notoriety. The best use of the body of the celebrity for political reeducation was inspired by the appearance in Hollywood of two stars from the enemy camp—one a true son of Fascist Italy, the other a good daughter of Nazi Germany. In October 1937, Vittorio Mussolini, the son of the Italian dictator, came to town to finalize a coproduction deal with producer Hal Roach. In November 1938 the Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl arrived to publicize Olympia (1938), her marathon documentary of the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The HANL-orchestrated protests against “Il Duce Jr.” and “Hitler’s honey” showed that revulsion could be just as ideologically potent as attraction.