Harold Eugene Roach, known around town and above the title as Hal, was there, in Hollywood, at the creation. A founding father of the motion picture industry and name-brand producer since 1916, the former muleskinner, prospector, trucker, movie extra, and gag writer was presiding kingpin of the Hal Roach Studios, the Culver City funhouse from which he mined the golden vein of slapstick screen comedy. With his friendly rival Mack Sennett, another Irish American macher among the Jewish American moguls, he churned out hundreds of picaresque one-and-two reelers crammed with cartwheeling flivvers, spritzing seltzer bottles, and aerodynamic custard pies.

In 1919, Roach put a pair of black-framed glasses on a pallid Chaplin imitator named Harold Lloyd and helped create, dollar for dollar, the most bankable marquee attraction of the 1920s. That same year, he corralled Will Rogers, the rope-twirling superstar of the vaudeville stage, for a hitch in motion pictures that somehow transferred the cowboy’s free-ranging wit into the silent medium. He also teamed a brilliant pantomime artist from British music hall theater and a rotund bit player to create the immortal ectomorph-endomorph duo of Laurel and Hardy.

Unlike Sennett, a talent tethered to the madcap chaos of the silent screen, or Harold Lloyd, a go-getter too enmeshed in the discredited Jazz Age to prosper in the Great Depression, Roach not only survived the transition to sound but thrived after the sonic boom. Without missing a beat, he guided Laurel and Hardy into verbal byplay and secured first-place prominence for his second-billed two-reelers on the motion picture program.

Roach’s trademark franchise and cash cow was his “Our Gang” short subjects, a monthly series featuring a multiethnic stock company of ragamuffin moppets whose membership was recast whenever puberty threatened to adulterate the kid stuff. Launched in 1920, it was the oldest continuous production unit in Hollywood.1 It was also his ticket to a lucrative long-term deal with MGM, the Tiffany studio, which in 1925 contracted to distribute the shorts.

By the mid-1930s, Roach’s child labor was working like a well-oiled machine. Built around the antics of cherubic everyman Spanky, cow-licked soprano Alfalfa, cutie-pie heartbreaker Darla, and saucer-eyed, coal-black Buckwheat, his litter of pint-sized scamps inhabited a prelapsarian world uncontaminated by grown-up worries and bigotries. “As spry a troupe of youngsters as ever gathered under the Klieg lights,” bragged the taglines, accurate for once. By then, the underage ensemble had undergone four complete turnovers, with Pete the Pup, at six years in harness, the longest-serving gang member.

The Irish American macher: producer Hal Roach in his office with an iteration of his “Our Gang” ensemble in 1933. The children (left to right): Carl “Alfalfa” Switzer, Bobby “Wheezer” Hutchins, Darla Hood, George “Spanky” McFarland, and Matthew “Stymie” Beard. (Courtesy of the Collections of the Margaret Herrick Library)

In 1937 Roach was at the top of his game. He was bathing in the glow of an Academy Award for Best Short, Bored of Education (1936), a ten-minute “Our Gang” charmer, and his first A-feature hit, the supernatural screwball comedy Topper (1937). “When a studio steeped in tradition of more than 20 years standing for turning out custard-pie cantatas and prat-fall fantasies suddenly goes dignified, severs all connections with the past, and brings in a picture of the caliber of Topper, that studio and the people connected with it bear watching,” noted an impressed Billy Wilkerson at the Hollywood Reporter.2 Also impressed, MGM sweetened Roach’s deal for the production of twelve “Our Gang” shorts per year and agreed to launch Laurel and Hardy into top-drawer feature-length attractions.

Flush with cultural cachet and reserve capital, Roach aspired to graduate not only from shorts to features but from mini-mogul to industry titan. On August 7, 1937, the stocky, debonair entrepreneur sauntered up the gangplank of the Italian luxury liner the S.S. Rex, bound for Genoa, Italy, and sailed into the treacherous shoals of international finance and big-power geopolitics. Undeterred by or just plain oblivious of the minefield he was cruising into, Roach planned to negotiate a coproduction deal that would link his name with a marquee performer not known for his comic timing—Benito Mussolini.

The Italian dictator had been Italy’s iron-fisted, vainglorious ruler since 1922, stepping into the international spotlight with a personality so charismatic and an agenda so transformative he brought new words into the American vocabulary—fascist, for the ideology; blackshirt, for his paramilitary followers; and Il Duce (“The Leader”), for himself. A shameless camera hog and publicity hound, Mussolini posed frequently for the American newsreels and, upon the arrival of sound, obediently recited English to secure face time on screen, his eyes scanning cue cards held just out of frame. A feature-length documentary entitled Mussolini Speaks (1933) further inflated his outsized presence on the American screen. Narrated by Lowell Thomas, the laudatory biopic toyed with the notion that Italian-style fascism might be just the thing to solve the American economic crisis. Bald as a cueball, arms folded across his chest, chin out and head bobbing, Mussolini on screen was a made-to-caricature personification of the puffed-up dictator with imperial delusions—until 1935, when the brutal invasion of primitive Ethiopia by the mechanized forces of Italy transformed his persona from strutting buffoon to ruthless warmonger.

Like his partner in Germany, Mussolini fancied himself a patron of the newest of the arts. He inspected foreign films as censor-in-chief and meddled with the scripts and casting decisions of Italian-made feature films. His most enduring cinematic legacy was architectural. Inspired by an earlier line of Caesars, he oversaw the design and construction of a modern Colosseum—Cinecittà, a massive 120-acre motion picture plant built on the outskirts of Rome. Boasting nine soundstages linked by six miles of macadamized roads flanked by towering pine trees, the “Roman Hollywood” was a monument to his grandiose ambitions and a testament to the central role of cinema in the totalitarian playbook.3

The first American producer to set his sights on Cinecittà was, ironically enough, Walter Wanger, Hollywood’s most urbane and unabashed liberal. In 1936, while in London on business, Wanger flew to Rome to meet with Mussolini and angle for a bilateral alliance. Encouraged by the discussion, Wanger formed an outfit known as Société Anonyme Cinematografie Italiano Walter Wanger, with Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sydney slated to star in the first joint venture.4 Spellbound by his glimpse of the Fascist future, Wanger hailed the glory that was Mussolini’s Italy. “A new Europe is definitely emerging” and “youth is at the helm,” he enthused to Cecelia Ager, Variety’s lady reporter, who passed along Wanger’s musings about a woefully misunderstood nation. “Italy has been hurt that we have an unfair attitude toward Fascism, that we don’t understand that Italy wants to help the Ethiopians, that the Ethiopians welcomed the Italian armies and went over gladly to their side,” said Wanger, spouting the Fascist line on the African carnage. “We only hear the other side of the picture over here.” Provincial folks in Hollywood would do well to think more globally. “Our America-made pictures will have to be less nationalistic, in order to interest the foreign market,” he advised.5 As late as July 1937, even as Roach was edging him out, Wanger insisted that his deal with Mussolini was “more alive than ever,” that transatlantic coproduction was a marvelous way to “help to cement friendly relations between film leaders in Italy and the United States.”6 The deal fell apart when Warner Bros., Wanger’s unlikely partner in the scheme, balked and pulled the plug.

With the field clear, Roach moved in. Upon arriving in Italy, he was ushered into the presence of the self-styled “Iron Man of Europe,” an audience that held little fear for a man who had gone nose to nose with MGM chieftain Louis B. Mayer. Being an old Hollywood hand, Roach also knew how to puff up an inflated ego. He tapped into both the dictator’s aspirations as a motion picture impresario and his paternal affections with an irresistible proposition: he would go into business with Mussolini’s 20-year-old son, Vittorio, in a company called RAM, an acronym combining Roach’s and Mussolini’s initials. The senior man would be the junior partner, the young Vittorio would be president.

Born in 1916, Vittorio was Mussolini’s second son, and a decorated veteran of the Ethiopian invasion, where he had flown bombing and strafing missions. Besides lineage, Vittorio’s qualifications as a Hollywood mogul included his irregular byline as the screen columnist for his father’s paper, Il Popolo d’Italia, published in Milan, and his contributions to the Italian film magazine Cinema. As a film critic, he hewed to the Fascist line and slammed the Hollywood studio system for its lack of virility and surplus of feminine flesh. In contrast to most of his countrymen, he expressed the fervent hope “never again to see the ears of Clark Gable, or Dietrich’s legs, or Garbo’s feet, or Joan Crawford’s mouth, or Katharine Hepburn’s nose, or Luise Rainer’s eyes, or Goldwyn’s and Ziegfeld’s ballet girls.”7

The younger Mussolini listed another literary achievement among his credits. In 1936 he had published a memoir of his service as a pilot in the Ethiopian campaign entitled Voli Sulle Ambe, known in America as Wings Over Ambe. In purple prose whose bloody hue was not lost in translation, he exulted over the joys of low-altitude bombardment and the pyromaniacal rush gained from incinerating straw-hutted villages. Modern warfare, he rhapsodized, was “the most beautiful and complete of all sports.”8

Being groomed for bigger things, Vittorio was appointed assistant director on Goffredo Alessandrini’s aerial melodrama Luciano Serra, Pilot, released in 1938. “If he shows any talent, he will be packed off to Hollywood with his new bride to study American technique,” Variety reported. “Idea is to train Vittorio as a sort of Will Hays for the Italian cinema and get Americans interested in playing ball with the Big Boy’s favorite son.”9 On April 21, 1937, while his father beamed and Fascist dignitaries stood at attention, Vittorio presided over the elaborate ceremonies marking the opening of Cinecittà.10

The son was thus a natural conduit for the Hollywood producer to insinuate his way into the father’s graces. Roach left his audience with Mussolini with a coproduction deal in his pocket and an anecdote too juicy not to repeat. According to Roach, during his pitch meeting with Mussolini, neither the cost overruns at Cinecittà nor the punctuality of the Italian rail system preoccupied the dictator’s mind. A devoted fan of Laurel and Hardy, he was distraught over the reported breakup of Roach’s perennially squabbling duo. Regretfully, Roach confided that the news was true. Already depressed by setbacks on the diplomatic front, Mussolini blurted out, “and just at a time like this, I learn that my very good friends have quarreled!”11 Surely, Vittorio and Hal would prove more amicable partners.a

On September 16, 1937, with his young ward in tow, Roach boarded the S.S. Rex for the return trip to America. No sooner had the ship lifted anchor than Roach spied a familiar figure strolling the decks—Charles C. Pettijohn, general counsel for the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. Happily met, the trio sunbathed, shuffleboarded, and dined together on the voyage home. They also posed for pictures fore and aft, a cozy scrapbook that gave the impression the MPPDA was also on board for the RAM deal. Moreover, while still at sea, Roach moderated a radio show broadcast over a nationwide hookup in which Pettijohn interviewed Mussolini.

Back in America, news of the Roach-Rome axis and wirephotos of the smiling threesome had preceded the Rex. On the morning of September 23, 1937, when the ship docked in New York Harbor, a horde of reporters, photographers, and newsreel cameramen waited at the pier to document the merger of Italian Fascism and Hollywood filmmaking.

To duck the flashbulbs, the trio boarded a Coast Guard cutter and raced for shore, leaving the howling press corps in their wake. “It was a beautiful day for sailing up the Hudson yesterday but 50 reporters, newsreel men, and photographers didn’t seem to enjoy it,” groused a stranded reporter.12 The journalists were not the only pesky greeters best avoided. Popular Front protesters, with the communists in the vanguard, had organized a shore party of placard-waving demonstrators. As soon as the tug hit dry land, Roach and Mussolini were rushed away under police guard to the Ritz Tower Hotel, a getaway arranged by the State Department at the behest of the MPPDA.13 By then, sensing the impolitic blowback, Pettijohn had ditched the pair en route and gone his own way.

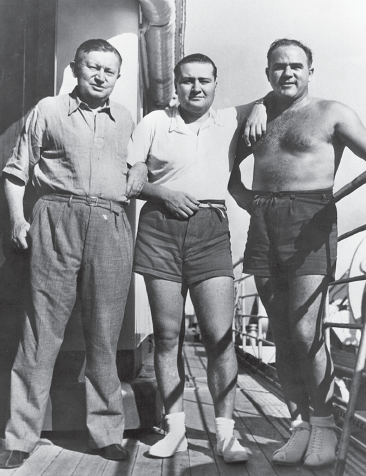

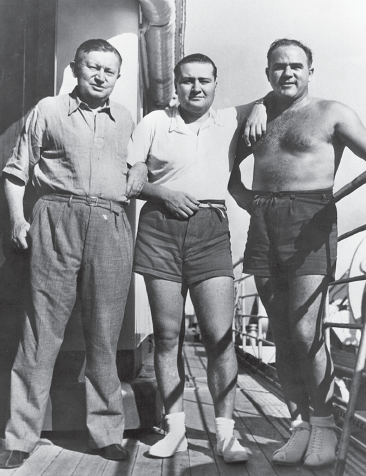

Happily met (left to right): Charles C. Pettijohn, general counsel for the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, Vittorio Mussolini, and Hal Roach aboard the S.S. Rex during their voyage to New York from Italy, September 1938.

That afternoon, at a boisterous, good-humored press conference, Roach and Vittorio made nice to the sulking journalists. Ebullient about the coproduction deal, he praised his partners, pater and fils. “I think [Mussolini] is the only square politician I’ve ever seen,” he said, describing himself as “100% sold on Premiere Mussolini and what he has done for the rich and poor of that country.” The son was a chip off the old block. “Vittorio Mussolini is here on a holiday as far as the kid is concerned,” Roach said, and immediately contradicted himself. “He’s going into the picture business and I’m going in with him.” Modestly, the Hollywood veteran pledged to be but a kindly mentor to the tyro producer. “I’m in sort of an advisory capacity,” he insisted. “Mussolini wants his son to go in to business. Vittorio decided on the film business and I’m sort of a chaperon for him.”14

Despite the smiles all around, a sense of buyer’s remorse already hung in the air. Pressed by skeptical journalists, Roach vehemently denied that Fascist propaganda would infect the two planned coproductions at Cinecittà, film versions of The Passion Play and the opera Rigoletto.15 The epics were to be “filmed with Italian voices and beauty, but with American screen technique.”16 Getting into the cross-cultural spirit, Roach dangled the tantalizing prospect that the RAM Rigoletto would be a parody featuring a reunited Laurel and Hardy.17 Amid the clamor, he also made a nervous request. “Please don’t mention MGM in this deal,” Roach pleaded. “MGM doesn’t want to be mentioned and, if you do, not only will this company be sore but Italy as well.”18 Nicholas M. Schenck, president of Loew’s, MGM’s parent company, was not happy about being linked to Fascist Italy and had told Roach as much when he landed in New York.19

“Il Duce Jr.”: 20-year-old Vittorio Mussolini (far right) meets the press at a convivial news conference at the Ritz Tower Hotel in New York, September 23, 1937.

Like MGM, the MPPDA also sought to keep the RAM pact at arm’s length. The home office in New York denied any official involvement with the transaction, insisting the MPPDA had “absolutely nothing to do with the Roach-Mussolini company,” and that the pictures of Pettijohn, Roach, and Mussolini on the high seas were occasioned by the mere happenstance of Mr. Pettijohn having “met the party aboard the S.S. Rex while returning to New York.”20

Immediately after the New York press conference, Mussolini and Roach headed out to Newark and boarded a TWA flight to Hollywood, the former aviator opting for the speed and novelty of a transcontinental flight when most motion picture executives still preferred the comfort and safety of a first-class berth on the Twentieth Century Limited.

When the pair touched down at the Union Air Terminal in Burbank the next day, the press was waiting on the tarmac. Vittorio strode to the radio and newsreel microphones and ventured a few comments calculated to endear himself to the natives. “Well, here I am in California. I have just arrived in this beautiful country,” he said in tentative but well-pronounced English. “It seems like my Italy. I think California is very beautiful. I know I will enjoy Hollywood.”21 He was then whisked to Roach’s mansion in Beverly Hills, where the police had already set up mounted guards and arranged a three-man, round-the-clock security detail to stand watch throughout Mussolini’s visit.22

Over the next few days, Mussolini toured soundstages, met with local politicians, and smiled for the cameras. At the Hal Roach Studios, he was trotted out for a full-dress press conference. Asked whether his father was disturbed by press reports of “communistic demonstrations” in New York, Vittorio chuckled and replied through his interpreter that his father had “much more important things to worry about than me.”23 Before leaving the Roach plant, he posed for pictures with studio technicians and the “Our Gang” kids.24 Later at Twentieth Century-Fox, he met with Darryl F. Zanuck for a photo op with a far more valuable child property, Shirley Temple.

On the balmy evening of September 28, Roach and his wife Margaret hosted an extravagant dinner and dance party in honor of their guest. The celebration would commemorate two joyous dates: Vittorio’s twenty-first birthday and the Roach’s twenty-first wedding anniversary.

Roach spared no expense for the lavish blowout, a swellegant soiree that shimmered with all the glitter of Hollywood’s Golden Age. “Undoubtedly this was typical of the party you readers all would like to attend,” teased syndicated columnist Ed Sullivan, regaling the hoi polloi with a peek at the high life. “Champagne, celebrities, commotion, cops, crowds, cakes, cliques, cars, carriages, carnival capers, chagrin, complications.” Under billowing tents set up over the mansion’s grounds, 300 tuxedoed and begowned guests (“the crème de la crème of the celluloid industry”) nibbled on cosmopolitan delicacies spread out over four buffet tables. Each table dished out an ethnic cuisine matched to a Central Casting character actor, dressed in festive native costume: Chinese bit player Chester Gan for the Chinese menu, Spanish singer Stelita for the Spanish dishes, Italian character actor Paul Procasi for the Italian food, and, presiding over the table for Southern-style home cooking, playing a servant once again, the African American actress Hattie McDaniel.25

Two orchestras—one Hawaiian, one Algerian—took turns serenading the stars, who moved to the music on a makeshift dance floor that was usually a tennis court. Flashing a red carnation in his lapel, Vittorio cut a dashing figure, twirling with the Roaches’ daughter Margaret, an aspiring actress whose nom de screen was Diane Rochelle. MPPDA president Will H. Hays honored the fete with a rare night out, but, of course, the abstemious Presbyterian declined the champagne. Among the swarm of guests, a stargazer could spot Cary Grant, Bette Davis, Spencer Tracy, Fred Astaire, and the gorgeous Constance Bennett, swanning by on her way back from the buffet tables “in black satin with skull cap featuring a large black ostrich feather.” The hawk-eyed reporter for Daily Variety also noticed a dolled-up Dolores Del Rio, attired “in a black dress with a hem bordered with silver fox to match her cape and black velvet bag with silver fox pom pom,” conversing in Italian with a smitten Vittorio.26 “He has a grand sense of humor, he’s very modest and thoughtful, and dances divinely,” cooed Del Rio.27

Outside the privileged perimeter, however, the atmosphere was not so bubbly. Fearing more than gate-crashing autograph seekers, a tense squad of L.A.’s finest enforced a tight security check for the shindig. “Uniformed cops halted you at the sidewalk, checked your name against the list in their hands, before you were allowed to proceed into the house and out past the lighted swimming pool to the tennis courts,” reported Ed Sullivan. “At the close of the party, outside as you left, cops examined you closely and accompanied you to your car.” For the giddy Isabel Sheldon, the society reporter for the Los Angeles Times, nothing could dim the splendor of an evening that was “one of the most brilliant social events of the season.”28

Not everyone in Hollywood thought the open-air bash at the Roaches’ was the hottest ticket in town. While motion picture royalty broke bread and clinked glasses with the Fascist prince, a cadre of lesser-known names was determined to spoil the party. Understanding that notoriety could be as useful as fame in furthering a cause, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League mobilized to make Mussolini an object lesson. Mussolini’s “presence here is not an occasion for celebration or social fetes,” lectured the League from its preferred platform, a full-page ad in the trade press. “Those who welcome him are opening their arms to a friend of Hitler and an enemy of democracy.”29 Dancing cheek to cheek with the boy prince the group dubbed “Mussolini Jr.” blemished the face of the entire movie colony.

Before the morning after (right to left): Hal Roach, his daughter Margaret, guest of honor Vittorio Mussolini, Roach’s wife Margaret, and his son Hal Roach, Jr., at the swank Hollywood party celebrating Mussolini’s twenty-first birthday and the Roaches’ twenty-first wedding anniversary, September 28, 1937.

Mussolini being technically a Fascist not a Nazi, the Motion Picture Artists Committee (MPAC) took point position from the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, but the byline on the protest ads and handbills hardly mattered: membership in the two groups overlapped promiscuously. Full-page ads in Daily Variety and the Hollywood Reporter denounced Mussolini, Roach, and the knaves who associated with them. “Hollywood is on record throughout the country as having welcomed Signor Vittorio Mussolini with open arms,” read the copy. “We feel that Hollywood does not deserve this reputation.”b

By 1937, Italy’s war crimes in Ethiopia were a moot point and the African nation a lost cause. Moreover, it was a battlefield out of the sphere of Soviet interest. Mussolini’s arrival in Hollywood provided a consciousness- and fund-raising opportunity for a crusade closer to the heart of the Popular Front. As the Spanish Civil War raged into its second bloody year, some 40,000 Italian troops were fighting alongside Franco’s Rebels on land, sea, and air. “We can best show the world what Hollywood really does feel about Vittorio Mussolini by helping to bind the wounds of innocent victims of Signor Mussolini’s favorite sport,” HANL urged. An already iconic photograph of a dead child—a dead white child, from Spain, not a black child from Ethiopia—stared out from the ads and leaflets. The pang of a guilty conscience could be soothed by donating truck-loads of medical supplies to the Loyalist cause in Spain.30

At some point in the time between the acceptance of Roach’s party invitation and the publication of protest ads from MPAC and HANL, the cultural zeitgeist around town had shifted a decimal point to the left. The stars who had dined and danced with Mussolini at Roach’s tennis court-ballroom awoke the next morning to discover that their big night out had left an unexpected hangover. According to Variety, the partygoers “resented the printing of their names as guests, especially when they learned that correspondents were now pasting the list in a convenient place [on studio bulletin boards] as a sort of blacklist.” In a business built on personal relationships and mutual back-scratching, mixing with the wrong crowd could have crippling career consequences. Seemingly overnight, the social pressure applied by HANL exerted a greater force than a potential job with Hal Roach. “Town is seething over the young warrior’s visit, and even those who were invited to Hal Roach’s party, which merged young Vittorio’s 21st birthday party and Roach’s 21st wedding anniversary, were sore at the producer for putting them on the spot.”31

Nor was the intramural Hollywood squabble over Roach-Mussolini merely a local news story. The war between the stars was avidly stoked by the national media. “It is a story inferentially revealed—a tale of ‘snubs’ and ‘cold shoulders’ by some of the swankiest cinema stars who, it would seem, were not of one mind with Il Duce’s son as to Fascism, war, etc.,” reported the New York Daily Mirror.32

The hard-news headlines from overseas ratcheted up the controversy. While the younger Mussolini was dancing with the stars in Hollywood, his father was meeting with Hitler in Munich. As the international press held its collective breath, the two dictators presided over a huge military jamboree strengthening the ties of the Rome-Berlin axis. The Associated Press report on the meeting paused to note that affairs of state did not totally consume a father worried that his son might be the target of anti-Fascist demonstrations. “Mussolini is keeping a watchful eye on the movements of his son, Vittorio, who is in Hollywood to learn something of motion picture production.”33

Red Kahn, the respected columnist for Motion Picture Daily, noted the sinister parallelism in the headlines. “Mussolini and Hitler in Germany, giving the world a renewed case of the ague,” he scowled. “Vittorio and Hal in Hollywood, giving the American film industry what ought to be a sweating bee of its own.” To Kahn, the coproduction deal between Mussolini and Roach was a “reckless lark” that boded ill all around. “No one individual has the right to consort with such a danger for his industry. Yet this is what Roach, unthinkingly or otherwise, has done. He has turned Metro nervous. He is seemingly unaware of the damage he may do to his own product in this market. He has aroused and angered the sensibilities of many liberal-minded men in the business. He has brought over a Mussolini, a product of a freedom destroying despot.”34

A shaken Roach dialed the long-distance operator and called Kahn in New York to respond to what Kahn later characterized as the ugly “vibrations of a number of thinking men in this industry, Jew and Gentile alike, to an arrangement by a prominent American producer with the son of the founder of Fascism and the current consort of the founder and chief trumpeter of Nazism.”

Aghast at the printed venom and personal shunning, Roach portrayed himself as an agent of constructive engagement. “I never made a move in Europe on this matter at any time without the advice and cooperation of some of the most prominent Jews there who told me I was doing the finest thing ever done in their estimation [by] tying up [Mussolini’s] son and taking the boy back to Hollywood.” While trying to explain, Roach only dug himself in deeper. “Particularly I did this on the advice of one of the most prominent Jews abroad” —here Kahn inserted a parenthetical assurance that the name of said prominent Jew would be furnished off the record upon request—“who thought it would do more good for the situation concerning Jews over there than anything that possibly could be done.”c

Roach blundered on. “After all, if a lot of people would get a little closer to this situation and understand that there are hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees now in Italy under the protection of that government, they would stop taking cracks at a guy who is in a position to talk to the guy who is a friend of the worst enemy a Jew ever had.” The envoy without portfolio imagined a situation in which, perhaps over dinner with Mussolini, “maybe I can suggest to him that Hitler is not going quite right about things and maybe Mussolini will write Hitler a note and tell him so.”

Roach’s diplomatic initiative on behalf of the Jews failed to mollify the Popular Fronters, who smelled blood and pressed their advantage. The Hollywood Reporter measured the chill in the air. “Feeling runs so high in some quarters regarding the present visit of young Mussolini, Hal Roach had best keep him off some of the major studio stages as he may be embarrassed by the actions of some of the top stars should he visit their sets.”35 The extras were no more cordial than the top stars. Watching pictures of Mussolini and Roach in the newsreels, Hollywood audiences hissed.

A star bigger than any on the studio rosters delivered the most stinging rebuke. On October 5, 1937, speaking in Chicago, President Roosevelt called for a “quarantine” against the “aggressor nations” that threatened the peace of the world. “The present reign of international lawlessness,” he proclaimed, “has reached a stage where the very foundations of civilization are threatened.” FDR named no names but he didn’t have to: Germany, Italy, and Japan were the aggressor nations cruelly sacrificing innocent people “to a greed for power and supremacy which is devoid of all sense of justice and humane consideration.”36 Roach suddenly found himself not only on the wrong side of Hollywood but of Washington as well. Just two weeks earlier, when the RAM deal was announced, it was seen as a coup. Box Office had praised Roach as “the man who beat all other American producers to the draw and made a deal with Italian interests for production at Cinema City near Rome.”37 Now he was the town pariah. Walter Wanger must have thanked his lucky stars.

Scorched by the press criticism and personal invective, Roach scrambled to untangle himself from the alliance. “Ever since his arrival in Hollywood with Vittorio Mussolini, Roach has been in a dilemma as a result of the plainly evinced antagonism which immediately sprang up in the picture colony for having associated himself with the Italian premiere’s son,” explained Daily Variety. “As the adverse pressure got stronger locally, with reluctance and positive refusal in some instances of important people in the biz to fraternize socially with the young Italian visitor, Roach began to figure out what would be most expedient.”38

What was most expedient was to cut his losses. No more the kindly mentor, Roach hustled Vittorio out of town, unceremoniously bumrushing “the kid” on a plane up to San Francisco under the name “W. J. Willis.” Columnist Ed Sullivan waved a snide farewell. “Vittorio Mussolini leaves Hollywood suffering from frostbite,” he gloated.39

To save face, the Italians told a different story. Taking umbrage at FDR’s Chicago speech, Mussolini senior had telephoned his son that same night, ordering him back home, under the pretense that the insulted prince was leaving Hollywood, in high dudgeon, on his own accord.

No one was buying the cover story. Smirking between the lines, Variety knew whom to credit for the abrupt departure. “A concerted drive of the [Hollywood] Anti-Nazi League against his presence in town made Vittorio Mussolini’s Hollywood visit too much for the 21-year-old boy to support in a style to which diplomacy is accustomed.” While progressives celebrated their “moral victory,” Roach was “incommunicado at his home nursing Public Headache No. 1.”40

In the person of the son of the bald dictator, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League had taken its first scalp. “I went over [to the Italian film industry] on the wrong premise, and got in by mistake,” a whiplashed Roach sputtered afterwards.41 Looking back over the fiasco, Daily Variety tallied up the cost in social capital and hard cash with a snarky headline. “Mussolini Deal Off: Duce’s Son Chilled by Reception.” As for his host: “Roach Out 12 Grand.” He got off cheap.42