In March 1938, as Nazi troops stormed into Austria, Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, issued his annual report, a corporate press release that, along with the usual unctuous blather, hinted that even the imperturbable Hoosier hearkened to the clack of goosesteps in Europe. “In a period in which propaganda has largely reduced the artistic and entertainment validity of the screen in many other countries, it is pleasant to report that American motion pictures continue to be free from any but the highest possible entertainment purpose,” he intoned. “The industry has resisted and must continue to resist the lure of propaganda in the sinister sense persistently urged upon it by extremist groups.” Barely pausing for breath, Hays recited the Hollywood mantra. “Propaganda disguised as entertainment” had no place on the American screen.1

The first line of defense against the lure of propaganda in the sinister—that is, overtly political—sense was the Production Code Administration, whose vigilance was typified by the narrow eye cast by regulator-in-chief Joseph I. Breen on a screen treatment entitled Personal History. Based on a best-selling memoir by New York Herald Tribune foreign correspondent Vincent Sheean and submitted for vetting in 1938 by independent producer and outspoken liberal Walter Wanger, the project dared to broach two headline happenings on the European continent—the Spanish Civil War and the Nazi persecution of the Jews. Breen predicted “enormous difficulties from the standpoint of political censorship, both here and abroad” because the scenario “raises, and takes sides in, such controversial racial, political, and religious questions as the civil war in Spain, and the treatment of Jews in Germany.” Smelling “a definite flavor of pro-Loyalist propaganda in the Spanish war sequences, and of pro-Jewish and anti-Nazi propaganda, in the sequences laid in Germany,” Breen suggested a wall-to-wall fumigation. “Such a flavor, it seems to us, will inevitably cause you enormous difficulties, when you come to release the picture.”2

Heeding the caution lights, Wanger shelved Personal History. “Although this book has had a terrific sale and is widely read, it is going to take the work of magicians or soothsayers to get it to the screen,” he groused.3 Breen did not issue a definitive thumbs-down; he simply signaled his displeasure, which was usually sufficient to change a producer’s mind.

Nonetheless, despite the best efforts of the executive ranks of the MPPDA and the regulators at the Breen office, “propaganda disguised as entertainment” was burrowing into Hollywood cinema. Personal History may not have made the cut, but the Spanish Civil War was too close to the hearts of Hollywood’s Popular Front not to infuse screenplays and inspire finished films. Besides, Spain was already a motion picture attraction of sorts—the first of the twentieth-century wars to be covered in all its street-level carnage and battlefield brutality by the newsreels.

The Spanish Civil War erupted on July 1936, when forces in North Africa led by Gen. Francisco Franco rebelled against the duly elected Popular Front coalition governing the Republic of Spain, and raged on until May 1939, when Franco’s triumphant Rebels (also known as the Insurgents) finally routed the fractious Republicans (also known as the Loyalists due to their fidelity to the elected government). A clash of political and religious temperaments as well as armies, the conflict pitted the aristocracy, the military, and the Catholic Church against liberal democrats, socialists, anarchists, and communists; Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy backed the Rebels; the Soviet Union and communist parties from around the world supported the Republicans. Each side poured supplies, advisors, and warriors into the cauldron. Recruits from far beyond the borders of Spain marched in to fight a war that was at once civil and symbolic. The fate of Spain itself might have been an afterthought.

Perceived then, and portrayed ever since, as a dress rehearsal for the main event on the horizon, the Spanish Civil War played out as foreshadowing even at the time. “This squalid brawl in a distant city is more important than might appear at first sight,” warned George Orwell in his 1938 war memoir Homage to Catalonia, speaking not only of the battle for the besieged city of Barcelona. When Barcelona, and more, was lost, he returned to London and wandered around Trafalgar Square, filled with dread and dismay. As Spain smoldered in ruins, the bobbies, the pedestrians, and the passengers on the double-decker buses were “all sleeping the deep, deep sleep of England, from which I sometimes fear that we shall never wake till we are jerked out of it by the roar of bombs.”4

The backfire from the Spanish Civil War was also cinematic. For the first time in motion picture history, the sights and sounds of mechanized warfare on European soil were captured by newsreel cameras. In terms of sheer visceral impact, the spectacle beggared the mock-heroics of the Hollywood feature film. Unlike the geographically distant and racially alien vistas of Ethiopia, invaded and conquered by Mussolini in 1935, or China, terrain for Japanese aggression since 1931, Spain was a blood relative on the map of Europe. The full-court press of the modern media of the day—wire service reporting, photography, radio broadcasts, and sound newsreels—brought the slaughter home to civilians who might be heartsick, horrified, and, if planted safely in a theater seat, perhaps a little thrilled.

Nonetheless, in any gallery of the visual arts documenting the Spanish Civil War, the motion picture medium warrants minimal wall space. From a century drenched in bloody images of war, Spain bequeathed two indelible tableaux, both of them stationary—Picasso’s mural Guernica, the wall-sized painting depicting the surreal horror of aerial bombardment on a civilian population, first displayed at the Spanish pavilion at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1937; and Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier, a photograph of a Loyalist militiaman freeze-framed at the moment of death, published in Life magazine on July 12, 1937. The art of cinema left behind no pictures of comparable resonance.

The poor finish was not for lack of effort by a dedicated cadre of motion-picture-minded artists, activists, and journalists. In 1937, galvanized by the threat to the cause of Spain, and encouraged by the work of a resourceful band of radical filmmakers (notably the social realist wallop of photographer Paul Strand’s Redes [The Wave, 1936], a homage to a fisherman’s strike in Mexico, and The World Today, a March of Time-like screen magazine that covered news the March of Time deemed unfit to screen), a group of seventy-five writers and filmmakers banded together to form Frontier Films, a production company dedicated to repudiating “the notion that independent films of valid social import cannot be produced in this country.” If the city whose name was synonymous with the movies refused to engage “the subject matter that needs to be dramatized in America’s most popular medium,” then the pioneers of Frontier Films (“a group of forward looking professional scenarists, directors, dramatists, and cameramen”) would assume the responsibility of harnessing “the most popular medium of entertainment.” Only then could films be created “that truthfully reflect the life and drama of contemporary America.” The like-minded Popular Front media review New Theatre and Film praised the outfit as “a step of incomparable importance to be welcomed and supported by all who resent the distortion of American life by the products of Hollywood.”5 Less credulous, Variety’s brief notice about the self-styled “Group Theatre of motion pictures” dedicated to “expressing an ‘enlightened’ social and economic philosophy” described the agenda as “frankly propaganda.”6

Along with Frontier Films, natural allies such as the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, the Motion Picture Artists Committee, and the Theatre Arts Committee worked to create an American home front for Republican Spain, with many of the artist-activists holding dual, triple, or quadruple memberships in the various wings of the movement. They raised money for medical supplies; recruited volunteers for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the American unit mustered to fight for the Spanish Republic; and worked to end the boycott of goods and guns mandated by the Embargo Act of 1937, the noninterference directive passed by an isolationist U.S. Congress in thrall to a powerful Catholic lobby. “I have been in Spain and I have seen what the people of that democracy, the people who elected that democracy, are doing there to protect it,” wrote Dorothy Parker in Hollywood Now, with no witticisms or smirks. “I don’t know when that war will end—but I know how it will. Democracy—and therefore civilization—is not going to be wiped out there.”7 In 1937, overcome by emotion while speaking to reporters upon her return from Spain, Parker wept.

The cause that brought the decade’s most quotable cynic to tears was taken to heart throughout the ranks of left-leaning Hollywood. Stars wrote checks, spoke at rallies, and signed their names to ambulances slated for shipment to the Republicans. “Joan Crawford is the sweetheart of democratic Spain,” boasted Hollywood Now, in fan magazine mode, gushing over the activism of MGM’s screen queen. “On the arrival of the famous Hollywood ambulance in Spain, the sight of Joan’s name inscribed on its side caused more comment than the other names.”8 Even Errol Flynn, Warner Bros.’ swashbuckling action star and an actor not known for political idealism, traveled to Spain in 1937 to file reports as “a sort of war correspondent.” (When Flynn was erroneously reported to have been wounded in Madrid, a panicked Jack L. Warner ordered the star of his stable back to safety.) “Professional Hollywood has been in a flutter over the European political situation for several years,” Variety noted in 1938. “Some of the leading stars and writers have participated at open forums and as contributors to warring factions in Spain. Latter is a Hollywood cause célèbre, and Hollywood hostesses long ago forbade mention of Spain at Hollywood dinner tables.”9

Dinner parties were not the only gatherings broken up by the Spanish Civil War. The death match between Catholics and communists in Spain created fissures in the Popular Front alliance between Catholics and progressives in Hollywood. For the Catholic actors, writers, and directors who attended Sunday mass at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Beverly Hills, rallying to the anticlerical Republicans backed by Joseph Stalin qualified as matter for confession. On May 28, 1937, in a meeting in Shrine Auditorium, twelve Popular Front organizations, banding together as the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, held a rally to raise funds for the Republican cause. The usual Hollywood suspects came out in force, not only to support Republican Spain but to sign on to a resolution, drawn up by the screenwriter Herbert J. Biberman, a zealous communist foot soldier, expressing outrage over “being called Communists, reds, and other names.” Variety’s report on the meeting included a telling comment. “Many Catholics in the picture biz gave the resolution their moral support, but said they couldn’t join the blast at this time.”10

A Hollywood cause célèbre: actresses Luise Rainer (left) and Gale Sondergaard (right) host a cocktail party for dancer Angna Enters (center), in Hollywood for a recital sponsored by the Motion Picture Artists Committee on behalf of the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, November 16, 1937.

Even without all of the Catholics on board—and many, including actor James Cagney and director John Ford broke with their church on this matter of faith—Hollywood’s Popular Front maneuvered to get their medium into the fight. As the Spanish Civil War raged, its stateside reserves fought their own war to bring the battle to American screens.

In late 1936, Twentieth Century-Fox chieftain Darryl F. Zanuck was mulling a motion picture project called The Siege of the Alcazar, to be supervised by H. R. Knickerbocker, the foreign-affairs correspondent for the Hearst newspaper syndicate, a media outlet notorious in Popular Front circles as a shill for the rebellion led by General Franco. Alcazar, a historical citadel and military academy in Toledo, was seized, defended, and ultimately won by Rebel forces in a dramatic siege that lasted from July through September 1936, a military action that was either a demonstration of “stoical bravery and deathless chivalry” or the invasion of a mercenary army made up of “Moors, the riff-raff of the foreign legion, Nazis, and Italians.” Paramount and Fox Movietone crews on site captured riveting footage of the siege and the defense of the fortress, the dynamiting of the fortress by the Loyalists, and the exodus of the defenders after Franco’s forces relieved the garrison.11

Getting word of the proposed film, anti-Fascist activists flooded Fox with angry protests. From London, the critic-screenwriter-producer Ivor Montagu, an upper-crust communist whose auteur network stretched from Sergei Eisenstein to Alfred Hitchcock, composed an “open letter to Darryl F. Zanuck” laced with invective and threats. If “you are thinking of telling, not a true story, but a fairy version of this tale—then, Mr. Zanuck, let me whisper just this little warning in your ear: there are men and women and children in every corner of the world, Mr. Zanuck, who will remember it, Mr. Zanuck, as long as they remember the real heroes of the Alcazar. And one day, Mr. Zanuck, you might come to regret it.”12

Under siege himself, Zanuck scrapped the project.13 The battleground of Spain, it seemed, was a real-world location no more suitable for Hollywood than Italy or Germany.

Unlike Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, however, the legally elected and diplomatically credentialed Republican government of Spain voiced no objections to motion pictures about the Spanish Civil War, at least those with the correct sympathies. The objections to Hollywood’s depictions of the Spanish Civil War came closer to home, from the MPPDA, which, as ever, was against politically inclined motion pictures on general principles and especially politically inclined motion pictures that leaned leftward. Yet without a diplomatic protest from a foreign embassy to provide cover and justification, the MPPDA might frown but it could not forbid. As a result, two Hollywood films brought the war in Spain closer to American screens than either the Fascism in Italy or the Nazism in Germany. One was a modestly budgeted and little noticed programmer that tilted mildly toward the Rebels; the other was a prestigious and high-profile A-picture that stood staunchly with the Republicans.

Paramount’s The Last Train from Madrid (1937) was first out of the gate. In late 1936, early on in the production process, anti-Fascist groups were reported to be “keenly interested” in the project. Paramount, said Variety, “has always been regarded as the least offensive, to the antis’ way of thinking, in both its newsreels and feature productions of all the major filmers.”14 Perhaps some of the sympathy for the victims of Rebel bombing seen in the newsreels might seep into the studio’s feature film.

To assure otherwise, the Breen office pruned the early versions of the script with its customary care. John Hammell, Paramount’s in-house liaison with the Breen office, was advised to take great pains “not to inject any material into your picture which might be offensive to either of the sides now fighting in Spain.” Breen tagged two sequences for deletion: in one, a Loyalist soldier’s foot stomps on a hand holding a crucifix; in the other, Loyalist soldiers stage a mass execution of Rebel prisoners of war.15 Playing an even hand in its commitment to bland neutrality, the Breen office judged the depiction of the Loyalists as anti-Catholic war criminals no more acceptable than the depiction of the Rebels as heroic crusaders for Christian civilization.

On April 6, 1937, Variety announced that “after long deliberation, the Hays office has finally okayed the script for Paramount’s The Last Train from Madrid.”16 Using his standard phrasing, Breen informed Hays that Paramount “has exercised great care to avoid taking sides.”17

Doubtless The Last Train from Madrid passed muster with relative ease because the plot leaned—not egregiously but perceptibly—toward the Rebels, or at least the atmosphere was not suffused with the romance of Spanish Republicanism swirling through the Popular Front. Directed by James Hogan, a high-yield studio journeyman, and written by Louis Stevens and Robert Wyler, the film was conceived as a hybrid of Grand Hotel (1932) and Shanghai Express (1932), with the Spanish Civil War providing background scenery and plot motivation. While artillery shells rumble offscreen, a cross-section of humanity scrambles to escape the war-torn city, trading lives and virtue for a ticket out of the combat zone.

A pre-credit crawl scrolling over newsreel footage of the fighting in Spain takes pains, as per Breen’s suggestion, to stress the impartiality of the forthcoming “account of fictional characters caught in beleaguered Madrid, fired with one common desire—Escape.” In Paramount’s version of the Spanish Civil War, no one is fired with a militant fervor either to defend or overthrow the Republic. “We neither uphold nor condemn either faction of the Spanish conflict,” a title crawl insists. “This is a story of people—not of causes.”

The people’s stories criss-cross promiscuously. Two old army friends, one a Republican (Anthony Quinn), the other a Rebel (Gilbert Roland), are in love with the same woman (Dorothy Lamour); a chatterbox American newspaperman (Lew Ayres) is hijacked by a female Republican soldier (Olympe Bradna) whose romantic yearnings sweep aside her military training; a Republican soldier (Robert Cummings) deserts because he can no longer serve on a firing squad; a Baroness (Karen Morley) will literally kill to get her ticket out. In the film’s climactic sequence, set at the Madrid train station, the loose threads are sewn together—the fortunate riders take their precious berths, the luckless are left on the platform or arrested. In the curtain-closer, Hollywood makes love not war. Cozy and cuddly in a compartment in the last train from Madrid, the male lead and female ingénue embrace for the sign-off clinch.

Below the radar of the Popular Front: American newspaperman (Lew Ayres) and a Loyalist soldier (Olympe Bradna) in Paramount’s The Last Train from Madrid (1937), set during the Spanish Civil War.

As a talking point in the partisan debate over Spain, The Last Train from Madrid performed little service to either side. Like so many interwar films with a war backdrop, it keeps a tone amorphously antiwar and blithely oblivious of the stakes in this particular war. Still, the geographical and historical specificity of the story—this is Spain at war, the setting is Madrid, the refuge is Valencia, the dreaded front is Cardoza—meant that the stern military command structure controlling movement out of Madrid can only represent the Republican forces, though perhaps only a well-informed partisan of either side would discern the contestants from all the background noise.

War being hell all around, neither Rebel nor Loyalist is conspicuously noble or morally culpable. Authentic Paramount newsreel footage is interspliced into the drama, showing scenes of civilians scattering in the streets and cradling infants, victims who can only be innocent Republican civilians attacked by Nazi war planes in league with the Rebels. Yet the Republicans also have blood on their hands. When a Republican colonel orders the execution of Rebel political prisoners, his subordinate is shocked. “Their only crime was to differ with us,” he objects. “In revolution, that’s treason,” snaps a true believer. In the end, the film does not so much take an evenhanded approach to the war in Spain as shrug its shoulders. The larger meaning of the Spanish Civil War is immaterial; only the interpersonal conflicts matter. Friendship is a cause “greater than patriotism,” says the Republican officer who throws away his cause, his career, and his life for a blood brother. “It keeps carefully away from the political issues,” the Hollywood Reporter noted with relief.18 “Strictly uncolored melodrama,” was the verdict from the disappointed Popular Front.19

Lacking big stars, lavish budget, and an overt political agenda, The Last Train from Madrid slipped under the radar. A film with a loftier pedigree and a double-edged title would be credited with—and blamed for—running Hollywood’s long-standing embargo against “propaganda disguised as entertainment.”

Blockade was the brainchild of producer, pundit, and bon vivant Walter Wanger. In class if not ethnic roots, Wanger was a Hollywood anomaly: born to privilege, Ivy League educated, and unabashedly liberal. The son of a wealthy San Francisco clothing manufacturer who came west with the great wave of German Jewish migration in the mid-nineteenth century, Wanger enjoyed the perquisites of a patrician upbringing and a Dartmouth education. (The family’s original name was Feuchwanger, and Wanger was related to Lion Feuchtwanger, author of The Jew Suss.) It was at Dartmouth that an encounter with the theater department derailed a planned career in the diplomatic service. In 1918, after a hitch in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during the Great War, Wanger signed on with Famous Players-Lasky and quickly moved up the ranks with the company that became Paramount Pictures.

In 1928, Wanger left Paramount, first for Columbia, and then MGM, where he hit his stride with the edgy political satire Washington Merry-Go-Round (1932) and the lavish costume drama Queen Christina (1933), the pairing being an apt expression of his dueling political and commercial sensibilities. In 1937 he signed a distribution deal with United Artists and went fully independent. A frequent commentator on the motion picture industry at public forums, in magazine articles, and on radio, Wanger was a press darling inevitably referred to as “urbane” and “erudite,” adjectives seldom applied to his fellow producers. Though considered a bit high-hat by Hollywood standards, he was also deemed capable of checking “his brains and aesthetic taste at the studio gates,” which was meant as a compliment.20 Even as Wanger was guiding Blockade through the Breen office, the “canny showman instinct” of a producer prominent enough to have his name not just above but in the title was on display in Walter Wanger’s Vogues of 1938 (1937), a garish Technicolor fashion parade worlds away from rag-tag, war-torn Spain.21

Blockade meandered through preproduction for over a year, the shifting titles of the many early drafts of the screenplay a sign of its troubled gestation: Castles in Spain, The Loves of Jeanne Ney, The River Is Blue, The Adventuress, The Rising Tide. “Castles in Spain (Wanger) is the first picture to use the Spanish Revolution as a background,” Breen informed Hays in February 1937 when the project first appeared on his desk. “The studio has taken great pains not to take sides in the matter.”22

Hollywood’s urbane, progressive independent: Walter Wanger with fiancée Joan Bennett at the banquet for the Academy Awards ceremony at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles, March 10, 1938.

Actually, Breen had taken great pains to see that the studio would not take sides. Knowing Wanger had lobbed a grenade in his lap, he personally shepherded the project through the Code’s bureaucracy, assisted by his number two man Geoffrey Shurlock and Code staffer E. R. O’Neil. “Any material involved with, or played against, the background of the present Civil War in Spain, is, in our judgment, highly dangerous, at the present time, from a practical standpoint, as well as [regards] distribution in Europe,” Breen told Wanger after looking at thirty pages of the first script, a collaboration between Clifford Odets, author of the ur-Popular Front play Waiting for Lefty (1935), and Lewis Milestone, director of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and member of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. “I take it that your plan is to steer a middle course and to play no ‘favorites’ in the present Civil War in Spain,” Breen queried, or suggested to, Wanger. Even so, “grave danger” awaited any picture “played against the background of the Spanish Civil War.” Merely to pinpoint the location was a risky gambit that would “be pretty generally booted about in Europe by those governments which may be ‘for’ or ‘against’ the parties engaged in the war.”23

A year later, with Spain still in flames, a second continuity draft by John Howard Lawson, now titled The River Is Blue, finally cleared both the moral and political hurdles put up by the Breen office. A playwright and screenwriter who had come West from Broadway in 1931, Lawson was the Communist Party’s commissar in Hollywood, a committed Stalinist tasked with whipping the freer literary spirits into the party line. Still, Lawson knew enough to keep his Marxism in check and to shade the picture with enough Catholic devotion from the Spanish peasantry to mute the pro-Loyalist coloring.

Breen judged the Lawson rewrite “reasonably free from danger from the standpoint of political censorship,” but warned Wanger “not to identify, at any time, the uniforms of the soldiers shown throughout the story” and to scrupulously avoid “‘taking sides’ in the present unfortunate Spanish Civil War.” The PCA chief underscored that last point: “It is imperative that you do not, at any time, identify any of the warring factions.”24 Of course, along the corridors of the Breen office, the staff was wise to Wanger. “This is a story of the present Spanish Civil War, in which neither of the warring factions are identified,” stated E. R. O’Neil in an internal memo.25

Uniform distortion: Henry Fonda (backframe, with Madeleine Carroll to his left) and Leo Carrillo (second in line) in Blockade (1938), Walter Wanger’s compromised depiction of the Spanish Civil War.

Besides military outfits, Breen insisted on further obfuscations to prevent viewers from connecting the dots. “You should assure yourselves that none of the incidents, or locations, in your story could possibly be tied in with the actual events that have occurred, or are occurring in Spain,” he instructed.26 Not that Breen’s fixation on military uniforms blinded him to other fashion risks. “The statue of the nude nymph should not be too pointedly ‘nude,’” he warned, before dispatching two staffers to the set to eyeball the risqué statuary.27

Satisfied that both the war and the wardrobe in Blockade were sufficiently opaque, Breen took off for Rome, to receive an honor that recognized his service as Defender of the Faith in a pagan realm: a Knighthood of St. Gregory, a coveted papal decoration for Catholic laymen, personally bestowed by Pope Pius XI.

Meanwhile, Wanger’s plans to bring aid and comfort to the Spanish Republic leaked out to precincts far beyond Hollywood. The more optimistic members of the Popular Front in America dared hope that a cinematic indictment of Fascist depredations in Spain might arouse Americans to petition Congress to repeal the Embargo Act and to intervene on the side of Spanish democracy. With no other marquee attraction to hold to its bosom, stateside partisans of the Spanish Republic invested great emotional resources in Blockade.

According to Wanger, the enemy’s forces were also monitoring his shooting schedule. Suspicious Spanish-looking strangers skulked outside the studio gates and trespassed onto the premises. Wanger complained to Secretary of State Cordell Hull that “spies” or other “mysterious persons” had infiltrated the lot during filming.28 “The fact that I have dared to use a civil war now going on in Europe as the background for a motion picture really caused all the discussion,” he told a radio audience. “I think that you will agree with me that I would be an unworthy American if I gave up my dramatic subject for fear it might offend some foreign nation.” He vowed to soldier on.

Wanger was as good as his word. To direct, he hired William Dieterle who, as a German Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, possessed firsthand experience with the subject matter. Ironically, Henry Fonda, the top-draw star of the anti-Fascist Blockade, was originally slated to adorn the premiere production for the Société Anonyme Cinematografie Italiano Walter Wanger, Wanger’s ill-considered flirtation with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini for a coproduction deal at Cinecittà. He also tapped novelist James M. Cain to punch up Lawson’s preachy dialogue. (At the time, screen adaptations of Cain’s own pulpy novels were themselves under blockade by the Breen office, a prohibition not lifted until Double Indemnity [1944].)

Set in spring 1936, Blockade opens in a landscape of rolling hills and fertile fields. This is a pastoral nation at peace, idyllic, Edenic, basking in the natural light of a friendly sun. Flute-playing shepherd Luis (scenery-chewing character actor Leo Carrillo) dotes on his flock while the gentle farmer Marco (Henry Fonda) waxes eloquent on the good earth. “The secret of life is in the ground,” he tells his companion, rubbing the dirt reverently in his hands. “Man must learn that secret and use it wisely. People have wasted the richness of the soil.”

The action moves from the agrarian fetishism of a Soviet five-year plan into a patented Hollywood “meet cute.” Norma, a beautiful, mysterious antiques dealer (Madeleine Carroll), zooms by in her roadster and crashes into Marco’s cart. After the symbolic collision of nineteenth- and twentieth-century horsepower, the oxen are hooked up to the battered vehicle and the couple is pulled slowly to the sleepy port town of Castelmare. He recites Byron, she gives him a flower.

The distant thunder of artillery blasts Spain out of paradise and interrupts the budding romance. As shells rain down, the terrified peasants of the valley flee in panic until Marco steadies their nerves and fires their patriotism. “This valley—it belongs to us!” he shouts. “Turn back and fight!” Morphing into a cohesive military unit, the peasants shoulder their weapons, take up defensive positions, and repulse the invading rebels.

Marco is rewarded with a medal for valor, the rank of lieutenant, and an assignment as a counterintelligence officer. “Spies and traitors are spreading false rumors, sending out information, betraying every move we make,” explains his commandant. “Our greatest danger is from the enemies among our own people. We must find them and clean them out!” Marco is soon papering home-front walls with signs reading: “WARNING! DO NOT DISCUSS MILITARY MATTERS WITH STRANGERS. BEWARE OF SPIES.”

Lawson’s screenplay is of the same mind. As the plot lurches forward, the trope of enemy infiltration is writ in capital letters. Blockade is not a combat film, a political screed, or a melodrama of lovers caught in the crossfire of war, but an espionage thriller in which the main threat is not the army across the battlefield but the spies behind the lines. “I have agents all over the country,” boasts a Germanic advisor to a treasonous military officer. “Every soldier in this place is one of my men.” Mirroring the fratricidal infighting that helped doom the real Republican forces, and perhaps already preparing a fallback, stab-in-the-back explanation for the looming defeat of the Republican forces the next year, Lawson’s screenplay imagines a nest of spies on the home front and traitors at the highest levels of military authority. The phrase is not used in the dialogue, but fifth columnists are everywhere.a

Despite the traitors in the ranks, a relief ship bringing aid to the starving and sickly civilians breaks through the blockade. Peasants give thanks at the altar, children cheer, and babies drink milk. Yet Marco feels no sense of victory. Tormented by the plight of his people and enraged at an uncaring world, he delivers an impassioned speech that was as close as Hollywood’s Popular Front ever came to launching a full-throated anti-Fascist broadside via American cinema during the 1930s.

Beginning in plaintive bewilderment, the peroration builds to a crescendo of righteous anger, the camera moving in for a close-up of Marco and then pivoting so his eyes look straight into the lens, beseeching the spectator.

Marco: Our country’s been turned into a battlefield. There’s no safety for old people and children. Women can’t keep their families safe in their houses. They can’t be safe in their own fields. Churches, schools, and hospitals are targets.

By now, this is no longer Marco speaking, but a screenwriter, a director, and a producer going eye-to-eye with moviegoers in a rare instance of direct address in classical Hollywood cinema.

Marco: It’s not war—war’s between soldiers! It’s murder—murder of innocent people. There’s no sense to it. The world can stop it! Where’s the conscience of the world?

The question hangs in the air as the film fades to black and the credits roll.

Blockade was given a send-off commensurate with the hopes riding with it. On June 3, 1938, at the Village Theatre in the tony Los Angeles district of Westwood, the film premiered to a packed house of pumped-up Popular Fronters. Arriving late, Wanger could find no seat at the standing-room-only screening and had to sit on the floor of the foyer, a good vantage from which to appreciate the rapturous reception his production engendered in its target demographic. “The audience cheered it to the echo, rising to its feet as a close-up of Fonda thundered direct to the audience the final line: Where is the conscience of the world?” reported the delighted critic for the Daily Worker, who had wangled a ticket.29

Not all moviegoers were to cheer so wildly. Despite Wanger’s disclaimers, the Code’s cleansing, and an advertising campaign that obscured the allegory (“Tense, unforgettable drama—compelling, youthful romance—welded into magnificent entertainment!”), Blockade was received by friend and foe alike as a brief in defense of the Soviet-backed Loyalists. On that, the Catholics and the communists agreed. Audiences “not sympathetic to the Red Cause in the Spanish Revolution will not be pleased with Blockade,” said a displeased notice in Motion Picture Herald, in synch with the house ethos. “Although somewhat cloudy and besmoked, [the film] will have satisfactions in abundance for the Left Wing.”30

“Where’s the conscience of the world?” Norma (Madeleine Carroll) and Marco (Henry Fonda) sift through the ruins of what can only be Spain in Blockade (1938).

Cloudy allegory or not, the Left Wing did indeed pronounce itself abundantly satisfied. Whatever its compromises, “Blockade cannot be regarded as impartial,” insisted Hollywood Now. “The world will understand, as it sees Blockade, that the film is arguing the cause of the Loyalists.… It’s so emotionally stirring that if only a collection could be taken after every performance, enough money would be handed in for us to buy up Franco outright and send him as a present to Hitler.”31 Agreed the Daily Worker: “It makes the position of the Spanish people so clear that the naming of names is superfluous. Coupled with today’s headlines, there can be no question as to the meaning of the film.”32

American Catholics certainly got the message. Having assumed Hollywood was a wholly owned and operated theological subsidiary, they were astonished to discover so heretical a deviation. The Catholics at the Breen office may have been mollified by Wanger’s compromises, but the Catholics in the pews were livid. “The Trojan horse is dragged within the walls!” cried the Catholic News. “It is a plea for peace, but peace at the Reds’ price!”33 What for the Popular Front was a dress rehearsal for the inevitable clash between Fascism and democracy was for Catholics a chapter in the long twilight struggle between Holy Mother the Church and godless Bolshevism. Little wonder that Blockade incited the most acrimonious case of doctrinal difference among movie-minded Catholics in the history of the Breen office.34

The shock troops for Catholic action against Hollywood were commanded by the National Legion of Decency. Formed in 1934, the Legion was far and away the most formidable and feared of all the private groups monitoring motion picture morality. Its mission was to assure Hollywood’s fidelity to the Production Code, a document that was, after all, a fair summation of Roman Catholic doctrine, having been written by a Jesuit priest, Daniel A. Lord of St. Louis, and Martin J. Quigley, the devoutly Catholic editor of Motion Picture Herald.

The Legion put the screws to Hollywood in two ways—first, through its trademark “Legion pledge,” in which Catholics raised their right hand to God and promised, on pain of sin, not to attend immoral movies; and second, by a letter-grade system that judged films by the light of Catholic teaching: Class A-1 (Unobjectionable for General Patronage), Class A-2 (Unobjectionable for Adults), and Class C (Condemned). The C was the mark of Cain, a brand that forbade Catholics from attending the blaspheming film without risk to their immortal soul. Catholics recited the Legion pledge at Sunday masses, at parochial school assemblies, and at Knights of Columbus and Ladies Sodality gatherings. The grades were printed in Catholic newspapers, distributed in parish newsletters, and read out from the pulpit by priests. Practically speaking, American Catholics exerted prior censorship over Hollywood cinema in two ways—through the in-house self-regulation of the Catholic-minded Breen office and through the ex officio pressures of the Legion. The two-pronged pincer movement gave American Catholics a virtual veto power over motion picture content throughout the classical studio era.

After 1934, with the antics of Mae West securely corseted and the tommy-gunfire of the gangsters muzzled by the enforcement of the Code, the watchful eye of the Legion fell increasingly on any glimmer of communist influence in Hollywood cinema. No less than smut peddlers, “those who would make motion pictures an agency for the dissemination of the false, the atheistic, and immoral doctrines repeatedly condemned by all accepted moral teachers” needed to be exposed and opposed. “Films which portray, approvingly, concepts rooted in philosophies attacking the Christian moral order and the supernatural destiny of man serve not to ennoble but, rather to debase humanity and, as such, these films are an affront to right thinking men and women,” declared the Most Reverend John T. McNicholas, archbishop of Cincinnati, in a statement on behalf of the Legion in 1938. “The Legion of Decency, with every resource at its command, shall challenge any program using the popular theatre screen to exploit such insidious doctrines.”35

Blockade seemed to fit the archbishop’s bill of particulars, but, like the Breen office, the Legion was unable to condemn Blockade on moral grounds. Also like the Breen office, it was unwilling to admit that a political agenda skewed its letter grades. Caught between religious loyalties and intellectual dishonesty, reluctant either to pass the film or flunk it, the Legion judges devised a “Special Classification” category for Blockade, appending an explanation warning that “many people will regard this picture as containing foreign political propaganda in favor of one side in the present unfortunate struggle in Spain.”36

For less literal-minded Catholics, neither the Breen office nor the Legion of Decency properly understood the transcendent values in play. Not constrained by the Code contract or the Legion’s letter grades, Catholic newspapers and fraternal organizations met the enemy head-on when Blockade premiered at Radio City Music Hall in New York. “Let the Reds, the anti-Christian forces, those who like to poison the wells, patronize United Artists and Radio City,” seethed Patrick Scanlon, the editor of the Brooklyn Tablet, taking aim at Wanger’s distributor and the venue across the bridge. “They do not want our support or our presence and they shall not have it.”37 The Knights of Columbus fired off a telegram to Will Hays decrying the “historically false and intellectually dishonest” portrait of the Spanish Civil War smuggled into the nation’s theaters “under pretense of entertainment.”38 More effective than the prose was the action on the street. The Knights manned picket lines in front of theaters daring to book Blockade, a tactic that terrified exhibitors. Rare was the Catholic moviegoer who would cross that picket line.

From the other side, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League and the Motion Picture Artists Committee rallied their overlapping memberships against the “Fascist boycotts” and “reactionary censorship” afflicting Blockade.39 Hollywood’s Popular Front understood that the argument was about more than a single film daring to wade into the political turmoil surrounding the Spanish Civil War. As left-wing standard-bearer the Nation put it, the attacks on Blockade were “fundamentally an attack not so much on an inferentially pro-Loyalist film as on the whole idea of making films on serious social and political themes.”40 Frank S. Nugent, film critic for the New York Times, was of the same mind. “Considering the customary insipidity of our pictures, we think the public would be grateful now and then for one with the power to stir indignation and controversy. We argue about books, plays, speeches, essays and editorials. A rousing fight over a movie should be a treat.”41

With no rooting interest in Blockade except their own, exhibitors gauged what the local market would bear. Very much wanting Catholic business, the Loew’s chain purchased an ad in the Brooklyn Tablet replying to editor Scanlon’s blast. “We leased this picture without feeling that it might be out of harmony with our policy of presenting only sheer non-propaganda entertainment,” Loew’s insisted by way of apology.42 By contrast, in San Francisco, the 1,200-seat United Artists Theatre wore its politics and studio pride on its advertising sleeve. “Censor be hanged!” screamed the copy. “The only Hollywood studio that dared make this picture!”43

No fool, Wanger tried to ride the publicity wave. Fueling the headlines to heat up a tepid melodrama, he declared that Blockade was imbued with the deeply American message “that ruthless bombing of noncombatants, no matter which government does it, is something that is horrible and should not be tolerated.”44 Whatever the Catholics felt and whatever the cost, he would not be intimidated. “I’m going to release this Spanish picture, as is, and if it’s banned in Europe, I’ll have to take my loss.”45

The response that mattered most—the box office tally—was not encouraging. Buoyed by sympathetic reviews (“the loudest explosion of praise in years!” bragged Wanger’s ads) and patronage from every stalwart Popular Fronter in New York, Blockade enjoyed a good first week at Radio City Music Hall, but faded thereafter. “It is too depressing, too heart-rending to be classified as entertainment,” Pete Harrison told exhibitors. “It may arouse the spectators, but it will leave them restless and unhappy, and, in the face of conditions today, it seems that such a picture is not what the masses want. Enough is said in newsreels and shown in newsreels to enlighten those who are interested in what is going on in Spain.” Worse: “The romance is in the end left hanging in the air.”46 Wanger and Lawson’s “preachment against war” sounded like a sure thing, Variety lectured after the limp returns came in, but “they learned too late that John Public dishes out coin for its entertainment rather than for sermonizing.”47

Back from Rome, the newly dubbed papal knight Breen, who had managed to duck the controversy during his absence, put things in perspective. “While I was in Europe on vacation the boys approved a picture called Blockade,” he wrote his friend Father Lord, the Jesuit priest and Production Code coauthor. “Shortly after it was released, the Knights of Columbus set up a howl, charging that it was ‘communist propaganda.’” To that, Breen observed, “there seems to be considerable differences of opinion.… I myself have seen the picture twice, and I do not believe that the charge made by the Knights is a fair one, and I am confident that there was no intent to propagandize. I have also heard from a large number of Catholics, many of them priests, who write and ask, ‘What is all the shouting about?’”48 To Breen, Blockade was nothing special. “The fact is that it is an ordinary spy picture of a kind that has been done many times before.”49 Of course, Breen and his staff had worked overtime to make certain Blockade would be nothing but an ordinary spy picture.

For that, the MPPDA was duly appreciative. “I want to say bravo to you for what you did about Blockade,” Arthur E. DeBra, research director for the MPPDA, wrote Breen, after the firestorm had died down and the film was safely out of the headlines.50 Soon, Spain too was a lost cause and the hopes for politically minded cinema from Hollywood nearly as defeated.

In a rueful postmortem written for Liberty magazine, Wanger reflected on his tangle with international politics and internecine Catholicism. Touting his capitalist credentials (“I believe in bigger, wetter swimming pools and more polo ponies”), he assailed the double standard applied to political speech when it happened to be expressed on celluloid. “Just because it has a timely setting and is a film, it is regarded as radical! The uniforms worn were confused in order to establish that the picture didn’t take sides. Yet each side called it propaganda for the other side!” Fed up, Wanger spat out a two-word description for Hollywood’s craven product line: “Censored pap!”51 In his heart, he must have known the epithet applied to Blockade.

Shut down by the MPPDA and the Breen office, Hollywood cinema depicted but two veiled versions of the Spanish Civil War. Independent cinema, however, a subterranean current that either snubbed a Production Code seal or was refused one, might intervene directly into the conflict. Spurred mainly by the Spanish Civil War, the second half of the 1930s witnessed the creation of a homegrown variation on the ideologically laced cinema that its practitioners in the Soviet Union called agitprop—the deployment of the motion picture medium to inspire militant action, the very impulse that Will H. Hays and Joseph I. Breen worked overtime to suppress. A spate of partisan manifestoes on film aspired to do in documentary what Hollywood refused to do in fiction.

The newsreel coverage of the Spanish Civil War laid the groundwork and provided much of the raw material for the documentary cinema of the 1930s. The images of war that began to flow out of Spain after the outbreak of hostilities in July 1936 projected a new order of raw intensity and visual explicitness. Though the worst of the carnage was self-censored by a medium whose editors well knew the limits of audience tolerance, the pictures of combat brought home by the mobile sound camera jarred moviegoers heretofore sheltered from blood and brutality. Most unsettling was the sight of dead and wounded civilians—women and children—in a total war where neither side placed noncombatants off limits. Vistas of ruined cities, tearful mothers, traumatized children, wailing babies, and corpses littering streets shocked spectators whose notions of cinematic war were shaped by the sanitized images—whether from the battlefield or the studio lots—of the Great War.

The aesthetics of combat photography emphasized the rupture. Breaking with the steady line of sight and privileged perspectives that defined the “invisible style” of classical Hollywood cinema, the jagged angles and jiggly motions of the camera seemed a visual correlative for the frantic zigzagging of frightened civilians scattering for shelter while the streets exploded around them. So much newsreel photography of the 1930s is static and monotonous, a drowsy slide show of plodding parades and droning speeches. The combat photography from the Spanish Civil War was fast-moving, explosive, and horrifying.

For newsreel cameramen—closer to the action—the war was a trial by fire. “Up until even a year ago, I’d say, the average newsreel cameraman, as regards his war experience with a tripod, was just a rookie in a class with a shavetail on West Point graduation day,” figured Paramount News cameraman John Dored, reporting from Madrid in the early days of the war. A former White Russian, Dored had earned his stripes covering the Russian Civil War and by the time he reached Spain had become a seasoned veteran. “During the past year, the Italo-Ethiopian matter [Fascist Italy’s brutal invasion of primitive Ethiopia in 1935] gave many of the newsreel boys an opportunity for post-graduate courses which brought them within sound range of rifles and exploding bombs. Now this Spanish trouble is ripening them for anything that may happen.” A confirmed adrenaline junkie, Dored sounded eager about the prospect of better and bigger battles to come. “Be it a European fracas or a catastrophe involving the entire world, American cameramen will be numbered among the most competent.”52

On the home front, American audiences were more solemn before the first sounds and sights of modern war in the newsreels. “Spanish unpleasantness is just as grim and bloodthirsty as in previous weeks,” reported Variety’s Robert Landry from a seat at the Embassy Newsreel Theater. “Fascist reinforcements arriving at the Alcazar reveal Toledo as a shambles and the survivors scarred and suffering. Paramount unspools some excellent stuff. Its boasts of escaping censorship seems plausible on the evidence.” In a flash, though, the solemnity turned to anger. “Embassy audience roundly hissed General Franco, adding his mugg to the gallery of hootables.”53 Landry’s description—both the impact of the imagery and the Loyalist sympathies of the audience—seems a fair reading of the crowd: terror before the up-close exposure to combat carnage, pity for the civilian victims, and fury at Franco.

Yet viewed from the comfort of a seat at the Embassy, the vicarious encounter with danger might also induce a tingle of excitement. The newsreels certainly ballyhooed the cinematic rush of their thrilling war coverage over its educational value. “American newsreels are hungry for Spanish revolutionary stuff, but so far none is obtainable,” wrote Daily Variety in July 1936, noting how tough the censorship and ground conditions were. “‘Too tough’—eh?” taunted the ads heralding a scoop by Fox Movietone News the next month. “Now on the world’s screens! Exclusive and sensational pictures of Spain’s revolt filmed under fire by Movietone News.”54

“Under fire” was the operative phrase. The peril of the cameraman—struggling to keep focus and framing, ducking for cover, running for dear life—was imbedded in every shot of combat action. For him, the danger was not vicarious. “Reading between the information sheets coming through to all newsreel headquarters in New York with the film from Spain, there is evidence that every time a crew ventures out to make pictures the men’s lives are ventured also,” noted an impressed report from Motion Picture Herald. “Stray bullets are commonplace when a nation is torn by civil strife, and hot-headed commanders, sullen in defeat or flushed with triumph, are wont to regard cameramen as enemy spies or as persons on whom to vent spleen or newly acquired power.”55 Spectators did not have to read between the lines to feel the death defiance in the camerawork: the sickening proximity to combat fatalities, the narrow escapes from bullets and shelling, and the shell-shocked perspective from behind the lens.

Besides mortal danger, a more familiar problem bedeviled the newsreel coverage from Spain. “In Spain today the censor problem—it’s hardly a problem,” said Paramount’s intrepid Dored. “It’s almost a catastrophe.”56 Battlefield commanders—who regarded newsreel cameramen as distracting annoyances and possibly security risks—confiscated cameras and destroyed exposed film. The New York offices felt lucky “if 25% of the negative which their staffs are exposing in Spain escapes seizure or mutilation.”57 To smuggle out the footage, crafty newsreel men hid the film cans in their coats and bribed troops to look the other way.

By common consent, the Republican side showcased itself to better advantage in the newsreels than Franco’s rebel forces—either by providing the newsreel outfits ready-to-screen footage or by guiding American cameramen through the battlefields and street fights. “Spain is treated by Pathé and Paramount with the horror and human stupidity of the whole mess again made manifest,” reported Robert Landry in March 1937, not really bothering to conceal his own loyalties. “Here is emotional heart-tug that has not failed to excite sympathy, applause, and hisses for the past six months or longer in the newsreels.”58

Some of the loudest hissing was aimed at one of the messengers: Hearst-Metrotone News. The newspaper chain owned by William Randolph Hearst tilted brazenly toward General Franco and the rebels. Though the newsreel arm of the mogul’s media empire covered the war more evenhandedly, the reel was held guilty by association. At theaters around Popular Front strongholds, sympathizers for Republican Spain booed, hissed, and catcalled at first sight of the Hearst logo, less because of any slant in the newsreel itself than because of the name on the title card. “Mr. Hearst’s newsreel has in fact, and conspicuously, never been for him a medium of personal expression or concerned with purveying his editorial policies,” insisted Terry Ramsaye at Motion Picture Herald. “His newsreel has been marked by its neutrality and general conformity to the conventions of newsreel production.”59 Of course, from a Popular Front standpoint, neutrality was the moral equivalent of lending aid and comfort to the enemy.

Hearst-Metrotone News was distributed by MGM through the Loew’s chain, and neither company wanted any audience agitation under its imprint. In November 1936 the reel changed its name and logo to News of the Day and underscored the rebranding by replacing longtime commentator Edwin C. Hill with NBC radio announcer Jean Paul King, a voice with no prior Hearst callback. Undeceived by the switch, Popular Front moviegoers continued to hiss. “These uprisings and expressions came from Communists and committed leftists,” muttered Ramsaye.60

Cathartic though it might be, hissing at a Hearst newsreel contributed nothing to the Republican cause on screen. To truly get in the fight, supporters of Spain needed to seize the means of motion picture production, not simply jeer or applaud at what the Hollywood-backed newsreels happened to unspool. No matter how heart-tugging the footage, its full potential as pro-Republican propaganda could only come with the directional guidance of a partisan narration (anathema to the newsreels) and a broader documentary canvas (anathema to the exhibitor locked in to tight running times for each item in the balanced program). With a confidence born of revolutionary fervor, Popular Front filmmakers took matters into their own hands.

In 1936 the Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens voiced the do-it-yourself credo of the radical filmmakers of the 1930s. Having looked around Hollywood and seen nothing to encourage a revolution from within, he declared, “the days of merely cursing or deploring Hollywood are over.”61 Quit griping and get into the action, he told his filmmaking comrades. Drawing on the raw footage culled from the commercial newsreels, and the talents of cameraman-activists on site who shouldered their cameras as weapons of war, the Popular Front sponsored or produced a slate of shorts and feature films that gave the Republican cause a visible place on the motion picture marquee—or at least on the marquees not affiliated with the major Hollywood studios. Edited for maximum punch, sweetened with music tracks, and given exhortative voice-overs, the films sought both to buck up the faithful and to mobilize recruits for the beleaguered Republic. With running times averaging twenty to thirty minutes, the shorts would have fit snugly into the top of a balanced program had a studio-affiliated theater been a viable outlet for exhibition.

Cobbling together newsreel footage and just-above-amateur footage by filmmakers at the front, the shorts were earnest, emotional, and makeshift endeavors. Entries included Madrid Document (1937), a chronicle of the resistance of the Republican defenders of the capital; America’s Lafayettes (1938), a homage to the volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade; Behind the Lines in Spain (1938), a British import by Ivor Montagu; and The Will of the People (1939), a survey of the resistance in Barcelona. By far, the two best-known and widely circulated of the group were a matched pair focused on the care of the sick and wounded, Heart of Spain (1937) and Return to Life (1938).62

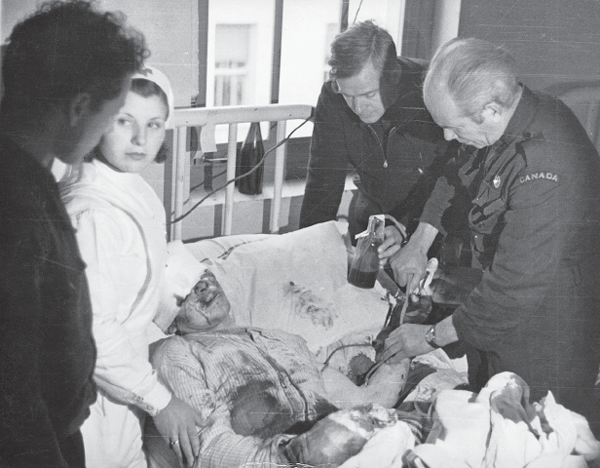

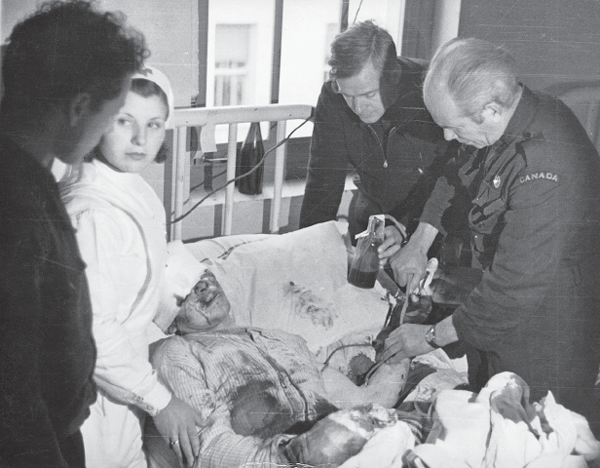

Both Heart of Spain and Return to Life were the work of Herbert Kline, editor of New Theatre and Film, the Popular Front must-read monthly. A dedicated partisan of the Republic and, at the time, a totally inexperienced filmmaker, Kline itched to trade his typewriter for more direct action. In December 1936, disgusted by the political backbiting at the magazine, he resigned his post and headed for the Spanish battlefield. Soon he was in the thick of the fight for Madrid “with Franco’s forces 150 yards away” and “scattered exchanges of rifle, machine gun, and artillery fire exploding nearby,” as he later recalled. Kline was doing radio broadcasts for the Republicans when the Hungarian photographer Geza Karpathi approached him to write a script for a documentary chronicling the medical work of Dr. Norman Bethune, a Canadian doctor and founder of the Hispano-Canadian Blood Transfusion Institute, an outfit dedicated to tending Republic soldiers and civilians. Bethune had developed a new technique for preserving blood. Kline and Karpathi were such novices at the craft that neither knew how to load a 16mm Eyemo: they brought it to a camera store, pretended it was broken, and watched carefully as the owner inserted the film in the sprockets.63

Kline and Karpathi were quick studies. Dr. Bethune was featured front and center as a dedicated caregiver ministering to frightfully wounded heroes, emerging as a motion picture hero in the tradition of the self-sacrificing physicians who labored for the good of humanity in the medicinal melodramas Hollywood favored in the 1930s. Taking the raw footage back to New York, the pair entrusted the final cut to the more experienced hands at Frontier Films. Pegged to the story of a mother and her wounded son, it was edited into an inspirational tale of the role of medicine in the fight against Fascism.

Encouraged, Kline and Frontier Films undertook a follow-up, Return to Life, a like-minded documentary on the medical mission in Spain. Working with the French photographer Henri Cartier and expert cameraman Jacques Lemare, Kline shot in Madrid and then edited the film in Paris, where it was released under the title Victorie de la Vie, before being Americanized by Frontier Films with a commentary by Ben Maddow and a new soundtrack.64 Of course, the focus on medical aid and the treatment of the wounded was calculated to tug at the heartstrings and disarm critics of Popular Front interventionism. Return to Life was billed as “the moving and poignant story of the work done by the International Medical Aid in connection with the plight of refugee children and the wounded soldiers who hope to fight again for the life of Spanish Democracy.”65 Few Americans could begrudge ambulances and medical supplies—as opposed to guns and ammunition—to a besieged civilian population.

Medicinal melodrama: a scene from Herbert Kline and Geza Karpathi’s pro-Loyalist short Heart of Spain (1937). (Courtesy of Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections, Brandeis University)

Yet no matter how wide the net cast by the Spanish Civil War shorts, they received scant commercial exhibition. Documentaries, especially documentaries with a left-wing slant, played in a few New York independent houses specializing in foreign and political fare, and in arthouse sure-seaters in limited engagements. They also circulated in 16mm at political clubs and in Popular Front gatherings to raise money and fortify the faithful. Celluloid rallying points, the shorts were ritual occasions for comradely solidarity and fund-raising, mainly for medical supplies, as when the Friends of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade used America’s Lafayettes to raise money for volunteers wounded in Spain.

To spread word of the good fight, the idealists of the Popular Front were not averse to borrowing a page from Hollywood’s ad-pub hucksters. The Spanish Civil War shorts were the unlikely objects of studio-style publicity stunts, endorsements, and gimmicks. To draw attention to Heart of Spain, the Motion Picture Artists Committee outfitted two special ambulances for a coast-to-coast tour in conjunction with screenings of the film.

Glitzier screenings and fund-raisers were also built around the shorts. At the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, the Motion Picture Artists Committee sponsored a fund-raising screening of Heart of Spain with co-director Geza Karpathi speaking before the film and actress Nancy Carroll and director Irving Pichel asking for funds in filmed appeals. Screenwriter Herbert J. Biberman and the tireless Donald Ogden Stewart chaired the proceeding.66 For the world premiere of Return of Life, the film division of the Theatre Arts Committee commandeered the Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York.

The shorts could count on sympathetic reviews from Hollywood Now, the Daily Worker, and other organs of the Popular Front. America’s Lafayettes was “a fine documentary showing everyday scenes of life in the Brigade, in the trenches, going in and out of the lines, with close-ups of Spanish heroes who are dead today.”67 Return to Life was awash “in humorous and touching scenes [of] front line battles, the care of the wounded, their convalescence in American hospitals, and their return to life and the battlefield once more.”68 The Will of the People was a powerful tale “of the heroic perseverance of the Spanish people in their efforts to fight off Fascist domination.”69 No reviewer with a Popular Front masthead dared pan an anthem to the cause.

By definition, however, shorts were second-class cinematic formats. Attention, prestige, and money for the Republican cause could only come with the expansion of the agitprop to feature length. To promote the shorts to the top of the marquee, a group of high-profile writers—John Dos Passos, Lillian Hellman, Ernest Hemingway, Archibald MacLeish, Clifford Odets, and Herman Shumlin—organized themselves into Contemporary Historians, Inc., to bankroll that most commercially unrewarding of motion picture genres, the political documentary.

The first of the feature-length pro-Loyalist documentaries was Spain in Flames, released in February 1937 by Amkino, the distributor for Soviet cinema in the United States. A program note dedicated the film “to the heroism of those who today are giving their lives that Spain may be free,” but the provenance of the production was obscure: no credits were included in the original release, and the only identifiable personalities on screen were Fernando de los Rios, Spanish ambassador to the United States, who spoke in a prologue introduction, and Dolores Ibárruri, the female firebrand known as La Pasionaria, the face of revolutionary Spain, who delivered a stirring call to arms. Amkino failed to respond to trade press inquiries about the identity of the narrators. Possessing better contacts in left-wing film circles, the Nation revealed that the editing was done in the United States under the sponsorship of the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy and the narration was written by novelist John Dos Passos and poet Archibald MacLeish. Dos Passos recited the narration and the actual editing was done by Helen von Dongen, an unheralded worker bee for Frontier Films.70 Its 63-minute running time took dead aim at a target audience Variety sized up as “the communistically-minded fans, the laboring element, and the Spaniards.”71

Spain in Flames sutured together two distinct parts, the first entitled “The Fight for Freedom,” filmed by Spanish Loyalists, the second entitled “No Pasaran” (“They Shall Not Pass”), filmed by Soviet cameramen in Spain.

The first section reviewed the harsh feudal history of Spain before its deliverance by the Republicans in 1935. The reign, oppression, and overthrow of King Alphonso, the medieval pomp of a tyrannical priesthood, and the strutting pageantry of an oppressive army pass in newsreel review. Never resigned to the overthrow of their lordly power, the aristocracy, the church, and the military collude in Franco’s coup d’état. As illustrated maps show the strategic designs of Italy and Germany in Spain, the narration asserts that without outside aid from the Nazis and the Fascists the rebellion would have folded overnight. To beat back the onslaught from the foreign Fascists, “Spain needs men of military experience to officer its armies.”

The second section records the arrival of a Soviet relief ship at the port of Alicante, one revolutionary socialist republic extending the hand of fellowship to another. Spanish workers surround the ship, raising their hands in the “clenched fist” salute of communist solidarity. Under the able command of José Diaz, leader of the Spanish Communist Party, the 5th Battalion trains and turns raw recruits—young boys and old men—into soldiers. In a big finish, La Pasionaria urges the defenders onward.72

Spain in Flames premiered at the Cameo Theatre, located on 42nd Street in New York, “where Union Square, the Red Square of Moscow, and Times Square overlap on one corner,” sniped Motion Picture Herald.73 Truth be told, the Cameo worked hard to live up to its subversive reputation. For 25 cents for daytime matinees and 40 cents for evening shows, a typical program bill at the Popular Front hangout consisted of the “only complete newsreels!” of the May Day parade in Moscow (“the greatest military demonstration in Soviet history”); the latest in Soviet news (“industry-arts-culture-education, etc.”); and With the Lincoln Battalion in Spain (1938).74 During screenings of Spain in Flames, reported the Herald’s reviewer, who doubtless sat on his hands, “applause for scenes of Loyalist heroism was counterpointed by booing and hissing of Sig. Mussolini and Herr Hitler when their faces appeared upon the screen.”75

Fully understanding that a box office mandate was the only measure that mattered to exhibitors, the Popular Front rallied around its first feature-length fusillade at Franco. “Let us rally the widest possible support in favor of a real anti-fascist film,” the Daily Worker urged. “With proper support today Spain in Flames can be held another week at the Cameo Theatre. If there is a big turnout in the next few days, dozens of neighborhood theaters will be influenced to show it. And if it can obtain mass support in New York and elsewhere, it will make all the more possible the production of more films from the point of view of the audience.”76 New Theatre and Film was equally emphatic. “Must be seen,” it ordered.77

Actually, it was the next film that had to be seen. The sole documentary classic to emerge from the motion picture activism inspired by the Spanish Civil War, and by far the highest profile of the cinematic calls to arms for the Republican cause, was The Spanish Earth (1937), directed by Joris Ivens, practicing what he preached; scored by Marc Blitzstein, the Popular Front’s favorite soundtrack composer; and written and narrated by Ernest Hemingway, the avatar of terse masculine prose. The cinematic, musical, and literary pedigrees guaranteed coverage in the press and playdates at the sure-seaters. The quality of the film guaranteed its place in the history of documentary cinema.

A documentary precursor and companion piece to Blockade (Wanger’s Hollywood film, released a year after The Spanish Earth, also bows before the revolutionary spirit of the peasant stock), Ivens’ contribution to the Republican cause was financed by donations from prominent writers and Hollywood luminaries with deep pockets. The fund-raising campaign was overseen by Archibald MacLeish, who, with John Dos Passos and the playwright-screenwriter Lillian Hellman, sketched out the original scenario. All felt that “no more effective defense against fascist propaganda in this country could be raised” than “to have made in Spain and distributed in America a documentary film giving the background of the Civil War and the true facts of its development.”78

In January 1937, Ivens went to Spain (“at the very real risk of his neck” as MacLeish put it) to yoke documentary cinema to the Republican cause. He was accompanied for part of the filming by Hemingway, who was reporting on the war as a special correspondent for the New York Times and who, self-deprecatingly for once, cast himself as mere “grip” on the crew. Besides adding to the luster of his own legend and gaining material for For Whom the Bell Tolls, his novel of the war published in 1940, Hemingway’s dispatches served as a prepublicity tease for the film. “I had gone with Joris Ivens to film infantry and tanks in action, operating behind infantry and filming the tanks as they ground like ships up the steep hills and deployed into action,” he wrote in a report datelined Madrid. The novelist-journalist painted a vivid portrait of combat photography under the gun:

All night the heaviest Insurgent artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire seemed close enough to be outside the window. At 5:40 A.M. the machine guns were hammering so that sleep was impossible. Ivens came in to the room and we decided to wake up the sound-sleeping John Ferno, film operator, and Henry Gorrell, United Press correspondent, and start out on foot.

While Republican forces “in the gray, olive studded, broken hills of the Morata de Tajuna sector” shelled an enemy stronghold, Ivens, Hemingway, and Ferno scrambled for good vantage on the action:

We decided to set up the big telephoto camera. Ferno had gone back to find a healthier position and he chose the third floor of a ruined house. There, in the shade of a balcony, with the camera camouflaged with the old clothes found in the house, we worked all afternoon and watched the battle.

Hemingway confirmed MacLeish’s comment about the very real risk to Ivens’ neck. “Just as we were congratulating ourselves on having such a splendid observation post out of the reach of danger a bullet smacked against a corner of a brick wall beside Ivens’s head.”79

In May 1937, Ivens returned to New York for postproduction work. With editor Helen von Dongen, he labored feverishly to complete the film, under pressure not from a studio deadline but the deteriorating position of the Republican forces in Spain. At the suggestion of Archibald MacLeish, the radio star Orson Welles was brought on board to narrate the film in his mellifluous baritone, but Ivens ultimately preferred the unvarnished timbre of Hemingway. By July 1937, with editing and Hemingway’s narration wrapped, The Spanish Earth was ready for its rollout. Ivens estimated the total cost at $18,000—a pittance.80

The Spanish Earth pits Republican civilization against Rebel savagery, with the opening images seeming to presage an Iberian version of a glacial Soviet homage to the sturdy Russian folk. Peasant women sweep village streets and men knead bread, scenes that might have been shot in the Middle Ages were it not for the Republican propaganda posters hanging in backframe. No element of Republican life is too mundane for reverence, including baked goods. “It is good bread, stamped with the union label,” says Hemingway, as the loaves, imprinted with the UGT acronym (Unión General de Trabajadores, the General Union of Workers), are delivered from a bakery. Republicans live not by bread alone, however. Despite the turmoil of war, they preserve the treasures of Spanish civilization from the rapacious Rebel bombing and rescue from the rubble ancient portraits, religious icons, and first editions of Don Quixote.

At the very real risk of their necks: Joris Ivens, with camera, and Ernest Hemingway to his right, on location filming The Spanish Earth (1937). (Courtesy of European Foundation, Joris Ivens)

Fortunately, the Soviet-style social realism gives way to a more poetic portrait of the face of war. Eschewing the hallucinatory surrealism of Picasso’s Guernica for the stark photorealism of 35mm, Ivens lingers over the aftermath of aerial bombardment on the civilian population, namely corpses on the street—a gruesome tableau of adults and children alike. Though mainly out of camera range, the perpetrators of the war crimes—Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany no less than Franco’s Rebels—are featured players. “I can’t read German either,” snarls Hemingway, as the camera looks over the wreckage of a downed plane with made-in-Germany markings. As further evidence, the camera pans—not without satisfaction—the corpses of Italian fighters. “Without the aid of Germany and Italy, the revolt would have ended six weeks after it began,” says Hemingway.

Though the politically unsophisticated viewer would not learn that the Soviet Union intervened on the side of the Republicans or that Spanish communists were in the vanguard of the battle, clued-in Popular Fronters could read the signs. Communists leaders are valorized with close-ups and extended selections from their radio speeches, while the charismatic La Pasionaria is framed for movie-star treatment.

On the evening of July 7, 1937, Ivens and Hemingway debuted The Spanish Earth to the most exclusive of preview audiences—a private screening at the White House. The gesture was classic FDR, showing sympathy for the Republican cause, shoring up his left wing, and not lifting a finger for tangible help. After a sumptuous dinner, the director and writer screened the film for the president, his wife Eleanor, and a small party of guests. Impressed with FDR’s “expert appreciation” of cinema aesthetics, Ivens reported that the president admired the “fine continuity” of the film. FDR was also said to be annoyed by a less attentive member of the audience who “disturbed him during the screening.”81

The next week, Hemingway and Ivens arrived in Hollywood to unveil The Spanish Earth to its donor base. A crowd of 200 specially invited guests attended a swank screening in the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel. An even more exclusive group got a sneak preview at the home of actor Fredric March, where fifteen members of the audience donated $1,000 each.82

On the night of July 16, 1937, at the Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles, the rollout for The Spanish Earth continued with a Popular Front version of a gala Hollywood premiere. Politically-culturally speaking, it was the hottest ticket of the year and the auditorium was packed. With admission priced at 25 cents to $1.10, the film grossed $2,000 with an additional $2,500 taken in by donations. “At least 2500 persons were turned away and the place was a madhouse of congestion,” blurbed Frank Scully in Variety. “The picture seems sure to make an army of converts for the Loyalist cause.”83

In truth, the converted were more like a platoon whose members had already enlisted for the duration. The Spanish Earth faced the familiar problems—limited bookings and sparse audiences. Like the rest of the Spanish Civil War documentaries, it was less a recruiting device for new converts than a ritual exhibition for true believers. “Ivens pushed his camera into the thickest part of the fight, and came out with enough footage to satisfy the exacting tastes of the ‘art cinema’ customers,” observed Box Office, the most sympathetic of the trade weeklies to the Republican cause, all too aware of the narrow market niche for the documentary. It urged exhibitors to link up with “labor unions, farmer’s cooperatives, peace societies, etc.” likely to “canvass their membership by mail in behalf of the film.”84

Critical reaction fell along predictable fault lines. “It is humanly impossible for any warm-blooded man or woman to sit through the film without feeling a burning need now, here, at once, this very minute, to do something to support the epic, Homeric battle of the Spanish people for the right to live like human beings,” proclaimed the choked-up notice in the Daily Worker.85 Nonetheless, warm-blooded American Catholics remained unmoved and unconverted. “There is not a scene in the entire film of a desecrated church, a butchered nun, or a murdered priest,” complained Motion Picture Herald. “Reference is made to the foreign support given to the rebel forces by Germany and Italy. However, there are some soldiers in the Loyalist ranks who look suspiciously non-Iberian.”86

Short and feature-length alike, the Spanish Civil War documentaries faced opposition on another front. American censor boards harassed the pro-Republican programming with special fervor. Lacking the protection of a Code shield, the films were blocked by city and state boards, especially in regions inhabited by a solid bloc of registered Catholic voters. The Chicago Board of Censors took one look at Spain in Flames and cut every reference to the Nazi interventions in Spain. The Ohio Board of Film Censors banned it outright for exuding “harmful effects,” explaining that “it was not in accord with the policy of neutrality adopted by this country to allow exhibition of a film which takes one side or another in a civil war in another nation.”87

The state of Pennsylvania went to great lengths to enforce cinematic neutrality.88 In Philadelphia, as 300 people waited in line to see Spain in Flames, an agent for the Pennsylvania State Board of Censors walked in with a constable, arrested the theater manager and his secretary, and shut down the screening.89 “Pure communist propaganda, dressed up as a plea for democracy,” decreed Pennsylvania governor George Earle.90

The filmmakers fought back with lawyers and won the case in state court. “Spain in Flames is a film containing current and timely news and thus is not within provision of censor law,” ruled Judge Louis E. Levinthal. “The pictorial part of the film is certainly news and the current events of today are the history of tomorrow.” The judge further held that the soundtrack, narration, and titles were also protected news and hence not subject to the censorship laws.91