“That new picture that Amkino has looks interesting,” speculated the pseudonymous Phil M. Daily, the chatty columnist for the Film Daily. “Titled Der Kampf, produced in Russia by German refugees,… it shows the events leading to the rise of Hitler, including the Reichstag fire,a the Leipzig trial of Dimitroff, with actual shots … view of the con centration camps … and of how cells were formed by the Communists and [how] underground work continued.”1

Sure enough, Der Kampf (1936) sounded interesting, but access to a foreign film, especially an anti-Nazi German-language film from the Soviet Union, was severely limited in America during the 1930s, even to that thin slice of the demographic undeterred by didactic melodrama, threadbare production values, and semi-legible subtitles. At fault was a pair of familiar culprints—the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America and its enforcement arm, the Production Code Administration.

The key initial in the MPPDA acronym stood for America: the association existed to maintain the domestic monopoly and global hegemony of the national cinema. In addition to his Presbyterian probity, MPPDA president Will H. Hays was chosen by the moguls for his connections to power brokers in Washington and Wall Street. The office that bore his name sought to restrict the import of foreign cinema while flooding the overseas market with product beyond the budget and skill set of non-American craftsmen.

In assuring that the balance of payments worked to Hollywood’s advantage, the PCA played a vital role. The Code seal was the essential transit visa for entry into America’s showpiece motion picture venues—the big-city emporiums that generated momentum for major attractions and the thousands of small-town neighborhood theaters (“nabes”) contractually obligated to play only films stamped with the Code seal of approval. Conveniently, foreign permissiveness about flesh, language, and ideology—immodest French décolletage, salacious British quips, or seditious Soviet agitprop—affronted provincial American tastes nearly as much as the competition alarmed the MPPDA. While patrolling the moral universe mapped out by the Code, PCA chieftain Joseph I. Breen also helped maintain a quarantine on foreign cinema.

Breen’s opposite number at the New York office of the PCA was, from 1934 to 1937, Vincent G. Hart, a New York attorney who had worked at Fox before becoming a legal advisor for the Hays office, and thence to censorship duties. Serving in the same office was Dr. James Wingate, former head of the New York State Censor Commission, who had been recruited by the MPPDA in 1932 to head the Studio Relations Committee in Hollywood, the weak-kneed predecessor of the PCA. A feckless enforcer incapable of going nose-to-nose with the moguls, Wingate was edged out by Breen in December 1933 and shunted off to the New York office. In 1937, Francis S. Harmon, a lawyer, journalist, and former national executive secretary of the YMCA, took charge of the East Coast office to add heft to a position that was seeing more controversial action on the import front. Hart and Harmon inspected foreign imports from a berth closer to the port of entry, always keeping in close touch via telegram or telephone with Breen on policy matters and tough calls. As a well-known Protestant layman, Harmon also provided a dollop of theological balance to the monolithic Catholicism of the Code’s inner sanctum.

Harmon, however, was not the only agent looking over foreign films. Just as Dr. Georg Gyssling, the Nazi consul in Los Angeles, kept tabs on the Hollywood studio system, German consular officers across America monitored the content, exhibition, and impact of foreign films critical of the Third Reich. Unable to sell pro-Nazi cinema, the Nazis could at least try to block the circulation of anti-Nazi cinema. When Der Kampf, billed as an answer to Hitler’s programmatic memoir Mein Kampf, was booked in St. Louis, the local German consul Reinhold Freytag wrote city Mayor Bernard Dickmann to demand the cancellation of a film that was “communist propaganda for creating hatred against anything German.” The mayor obliged.2

“Hollywood keeps discreetly away from controversial pictures,” Variety noted approvingly in 1938, complaining that “such controversial pictures that do deal with world events, their causes and effects, may be considered good box office for the arty theaters which cater to special audiences who are always on the lookout for pictures that are in [tune] with their thoughts on questions of a social and political nature.”3 With theaters in liege to Hollywood out of the game, the “arty theaters”—also called “arties,” “arty cinema parlors,” and “‘art’ houses”—were the only places in town for moviegoers bent on contributing their entertainment dollars to the anti-Nazi cause.b As a result, some of the fiercest conflicts over Nazism on screen in the 1930s took place away from the main stage of American cinema, on the fringes, around films that did not even speak the native language.

Before January 30, 1933, German cinema was far and away the most popular alternative to the domestic product in American theaters. Though the revenue was chump change compared to the receipts raked in from Hollywood fare screened in the plush first-run houses, German cinema had carved out a solid niche market in the big cities and in German enclaves in the Midwest.4 “Profits derived from these films are much larger than generally believed,” noted George R. Canty, trade commissioner for the U.S. Department of Commerce, in 1932.5 That same year, 67 of the 141 foreign imports released in the United States were made in Germany, a tally that surpassed even the imports from the Anglophone British.6

About 200 theaters specialized in what the trade press dubbed “German tongue talkers,” with twenty of the venues operating in New York City alone, most clustered in the Yorkville district in upper Manhattan, a concentration of German Americans of both Jewish and non-Jewish lineage.7 Whatever the location, almost all the outlets for foreign films were in theaters seating 600 or fewer, often known as “sure-seaters” because of their corner on a small but reliable market. Though a succès d’estime would cross over to an emergent arthouse crowd of urban intellectuals, the core audience for German cinema was German-speaking Jews, estimated to account for 65 to 70 percent of the consumer base.8

The optimal commercial fate for a German import was achieved by Leontine Sagan’s Maedchen in Uniform (1931), a rough Weimar gem that marked the crest of the German wave in the early-sound, pre-Nazi era. Released stateside in September 1932 and imported by veteran foreign-film distributors John Krimsky and Gifford Cochran, the distaff bildungsroman was buoyed by word of mouth insinuating lesbian shenanigans in a girls’ boarding school and perhaps a glimpse of maedchen out of uniform. Like so much late Weimar cinema, Sagan’s tightly corseted melodrama seems to flash forward to the Third Reich: the school is built around brutal authoritarianism and spartan living, a claustrophobic milieu seething with the hormonal energy of repressed adolescence. The film garnered full-throated critical praise and landed on many of the year’s Ten Best lists. “It is vastly different from the run-of-cargo Hollywood diet,” confirmed the New York American, spotlighting the lure of the exotic.9

Maedchen in Uniform was the last of the crossover hits from the Weimar era. After Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor, American moviegoers fled German cinema as if propelled out the doors by Nazi stink bombs. “The sudden hostile Hitler attitude is being reflected pronto at the box office of the German talkers in this country by several of the sure-seaters switching to French product or resuming American subsequent run bookings,” Variety reported less than two months into Hitler’s reign.10 The number of theaters specializing in German imports plummeted to single digits—three in New York, one in Boston, and a few scattered around the Midwest. As Nazi antisemitism flared, stateside exhibitors of German cinema looked out over rows of empty seats.11 They changed marquee fare or went belly up.

So acute was the revulsion to the Nazi brand that slates of imported German films that had been produced before Hitler came to power, but which were already in the distribution pipeline, found themselves judged guilty by linguistic association. Importers Cochran and Krimsky pleaded, to no avail, that the lately chic Maedchen in Uniform showed “the failure of institutions and governments founded on the militaristic regime which Chancellor Hitler is said to be trying to restore.”12 No matter: any echo of the German tongue grated on American ears. In 1934, just making its way to the American marketplace, Fritz Lang’s creepy thriller M (1931) was also caught in the cultural lag. At the Mayfair, a landmark sure-seater in New York, the management was forced to withdraw the German-language version of M and substitute the English dubbed version when irate customers asked for refunds “after listening to a few minutes of German dialog.”13 (Lang was getting shut down on both ends: in Germany, the Nazis banned his The Testament of Dr. Mabuse [1933] as “communistic.”)14

One production conceived in the late Weimar era earned its antipathy with a postproduction gesture of solidarity with the successor regime. Tay Garnett and Arnold Fanck’s spectacular Arctic adventure film S.O.S. Iceberg (1933), the last of the big German American coproductions, starred Leni Riefenstahl, still an outdoorsy actress, and Maj. Ernst Udet, the famed Great War flying ace, as intrepid polar pilots. It was Major Udet, not the future Nazi auteur, who undermined the film’s box office while on a promotional tour in America by brandishing a swastika in Hollywood and Chicago.15

Predictably, nabes in Jewish districts were most sensitive to the stain of German origin. In the Jewish enclave of Brighton Beach, New York, the Tuxedo Theater canceled its booking of Erich Washneck’s Zwei Menschen (1931), a faithfully bleak version of Peter Voss’s novel, “in protest of Hitler’s anti-Semitic outrages.” In red typeface, the printed program for the theater declared: “All German films will be boycotted at this theater until Hitlerites cease their brutalities against the Jews.” Other former fans of German cinema made common cause with the Jewish moviegoers in Brighton Beach. Variety pointed out that “a goodly portion of the German American population is figured as being in sympathy with Jewish feelings on the matter and are also laying off the German product.”16

American Jews in the motion picture business warned that any boycott of German imports would only rebound to the grief of their kinsmen overseas. Arthur Ziehm, general manager of the World’s Trade Exchange and a prominent importer of German cinema, reminded boycotters that “by far the larger percentage of German producers, scenario writers, directors, and artists are Jews” and therefore a boycott would “injure the Jews of Germany more than it would affect the Hitlerites.”17 But few Jewish Americans could watch German cinema without seeing Hitler’s face in every frame.

A defiant exception to the embargo against Nazi cinema was the Yorkville Theatre located at 96th Street and Third Avenue in upper Manhattan, a no longer sure-seater notorious as a showcase for Nazi releases. In 1933 the newly refurbished, 550-seat Yorkville opened its doors as an unlikely business proposition “run by two Jewish boys in an Irish neighborhood and showing straight German films,” joshed Wolfe Kaufman, Variety’s former Berlin correspondent, now keeping an eye on Nazi film culture from his desk in New York. The Jewish boys were independent exhibitors Joe Scheinman and Al Schiebar, and the “Irish neighborhood” was a reference to the fact that despite its name, the Yorkville was situated on the outer periphery of German hegemony in New York. It’s “tough enough to sell German pictures right in the thick of the German nabes these days without trying to peddle them in [a] spot that’s composed of about 60% Irish and almost all the rest of them Jews,” puzzled Kaufman.18

The Yorkville hoped to draw crowds with a provocative line of counter-programming. Catering to the estimated 40,000 Nazi sympathizers in and about the city, Scheinman and Schiebar booked what they thought the market would bear. In May 1934, almost a year after its Berlin premiere, S.A.-Mann Brand bowed at the Yorkville. Tagged as the first “100% Nazi propaganda film to get a public showing in the United States,” the original version included newsreel shots of Hitler and antisemitic slurs in the dialogue (“Juda verrecke!” meaning “Perish Jewry!”), phrases deleted by domestic censors. “Pure propaganda for the Nazis,” declared the Film Daily. “Anti-Semitic stuff is avoided.”19

S.A.-Mann Brand tanked, as did a follow-up, Hitlerjunge Quex (1934), the story of a youth, raised in a family of perfidious communists, who converts to clean living with the Hitler youth. By then, even the venue notorious as “America’s only Nazi film house” balked at raising its arm directly to Hitler. Released under the title Our Flags Lead Us Forward to avoid the onus of the surname, Hitlerjunge Quex was publicized with nary an inkling of its Nazi sympathies.20 To expose the subterfuge, a sly anti-Nazi activist handed out handbills in front of the theater outing the owners as Jews, thereby alienating two core audiences: Jews, who refused to patronize a theater showing Nazi cinema, and Nazis, who refused to patronize a theater owned by Jews.21

The first “100% Nazi propaganda film” to play stateside: the titular storm trooper (Heinz Klingenberg) shares a tender moment with his mother (Elise Aulinger) in the Nazi import S.A.-Mann Brand (1933), booked by the Yorkville Theatre in New York in 1934.

With the German logo repellent in the American marketplace, the Nazis tried cloaking devices. A 20-minute Ufa short entitled A Trip Through Germany (1935) attempted to smuggle in Nazi propaganda in the guise of a travelogue. Celebrating the conjoined spirit of old and new Germany in a guided tour of the landscape and architecture, it mixed pastoral scenes of gemütlich peasantry with the vibrant energy of a swastika-bedecked nation. “Unsuited to general audiences,” Variety cautioned exhibitors. “What little entertainment value it might hold is nullified by the bald propaganda for Hitler and the Nazi rule that is its prime purpose.” Snuck into the program at the Embassy Newsreel Theater, the film was greeted with stony silence.22

The Nazis also sought to infiltrate the American market under the cover of a different foreign language. In 1937, Ufa released the French-language production Amphitryon (1935) without the studio logo or other telltale indicators of national origin. Based on the racy play by Jean Giraudoux and directed by Reinhold Schuenzel at the Ufa plant in Neubabelsberg, the film was a sophisticated comedy of manners, human and divine, drawn from the Greek legend of a priapic Zeus attempting to seduce the virtuous Alceme. Booked unknowingly by the 55th Street Playhouse in New York, the imposter was exposed by the most vocal of the anti-Nazi groups in America in the 1930s, the Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League to Champion Human Rights (NSANL).

Based in New York and founded by Samuel Untermyer, a high-powered lawyer and tireless Zionist, NSANL boasted a core membership of 10,000 activists and maintained branches throughout the country. Though less glamorous than the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, the New York outfit was better connected to the American mainstream through a network of churches, synagogues, and community centers. The group forged links with the American Federation of Labor, listed New York mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia on its board of directors, and claimed access to some 2,000,000 sympathetic Americans. Its monthly Anti Nazi Economic Bulletin tracked imported Nazi goods and coordinated boycotts.23

As sites for anti-Nazi consciousness-raising, motion picture theaters offered ideal targets of opportunity. The double signage of a picket line under a theater marquee drew newspaper photographers—and traumatized theater owners. As Nazi attempts at cinematic subterfuge became subtler, NSANL launched regular campaigns of exposure and retaliation. “Although in the past the League has successfully invoked the boycott against Nazi-made films, a more emphatic movement has become necessary because German film interests are releasing pictures through subsidiaries in other countries, often concealing the real Nazi ownership,” the group declared.24

NSANL meant business. On November 13, 1936, it summoned stateside distributors and exhibitors of foreign films to a meeting at its New York headquarters and delivered an ultimatum: stop playing Nazi films or face boycotts and picket lines. The League then force-fed its guests a resolution that none refused to swallow. To wit: “We will not exhibit or release any film unless the same bears upon its face a title descriptive of the country of production of the film and, where the information is available, the producer thereof.” The cross-dressing Amphitryon, the film that had spurred the League to action, was peremptorily canceled by the 55th Street Playhouse.25 Six months later, hoping that memories had faded, the Belmont, an off-Broadway theater, tried to revive the picture for a two-week run. After a week of picketing by the Joint Boycott Committee of the American Jewish Congress and the Jewish Labor Committee, the house bowed to popular demand. “The film,” reported a pleased notice in Box Office, “is headed for oblivion, as far as another attempt at a New York showing is concerned.”26

Foreign film distributors—decidedly small fry in the scheme of the motion picture marketplace—grumbled that NSANL’s anger was selective. What about Loew’s, MGM’s corporate parent, which was distributing Olympic Ski Champions (1936) and Sports on Ice (1936), a pair of short films about the winter Olympics in the Bavarian Alps shot by Nazi filmmakers? Both shorts also boasted commentary by the laconic Pete Smith, the voice of MGM’s popular series of specialty short subjects.

Taking the point, NSANL telegrammed Nicholas M. Schenck, president of Loew’s. “We understand the Pete Smith shorts on the Olympic Games were produced by the Nazi German Government and sold to your organization for exclusive distribution,” the League informed Schenk. “As we boycott all German goods and services sold in this country, we should be interested in a statement by you in this regard before we take definitive action against your organization and theaters booking these shorts throughout the country.” MGM responded with the immediate withdrawal of the two films—but only in New York, the hub of anti-Nazi activism.27

Stymied by boycotts and bad films, Nazi attempts to penetrate the American motion picture market hit an ever-hardening wall after 1933.28 Though the Nazis offered the films to exhibitors on an advantageous rental agreement (a straight percentage basis, with no minimum cash guarantees), outside of the handful of houses in Yorkville and German enclaves in the Midwest, exhibitors shunned the titles on principle or to avoid negative publicity. Even at the venues that played German fare, the flashpoint signs of Nazi origin were nowhere in sight. The Ufa logo disappeared from the title cards, and Hitlerite imagery—swastikas, eagles, and the face of the man himself—vanished from theater fronts. Tellingly too, overtly antisemitic and pro-Nazi productions stayed in Germany. Historical pageants and musicals set far away from the Third Reich were the designated representatives of German cinema abroad.29

A typical entry was the nondescript Der Katzensteg (1938), a costume drama set during Napoleon’s invasion of Prussia, which played at the Casino in New York. “Title is meaningless and best so,” commented Variety, unable to figure out why the film was called The Catwalk in German. “It won’t drive away anti-Nazis.”30 Nor would it drive in non-Germans: like many of the German films that managed to secure a stateside play-date, Der Katzensteg was screened without English subtitles. Why waste money on translating, subtitling, and duping special prints for a nonexistent crossover audience? “Without [sub]titles, it is a hopeless jumble of words for any but those hep to the Nazi jive,” complained Variety’s long-suffering critic on the German beat, referring to the lingo not the message in a by-the-numbers juvenile comedy-drama called Jugend von Heute (1938).31

No sign of a swastika: a still from the Der Katzensteg (1938), a costume drama taking place during the Napoleonic wars and typical of the fare imported into the United States from Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1939.

Given the business and the locality, the odds were good that a Jewish-owned operation would be counted among the few remaining distributors of German films in New York. The irony did not go unremarked. “The Germans in Germany don’t mind Jewish help in trying to scrape some money out of the U.S.; that kind of money is still money to them, not distasteful or tainted,” commented a bitter Wolfe Kaufman. He also suspected a more direct financial subvention by the Nazis in the form of under-the-table bribes to American exhibitors. “The German government helps behind the scenes, apparently, since no money was asked for to speak of,” Kaufman noted of one arrangement.32

In 1939 the U.S. government levied a 25 percent duty against German imports, a move that had little impact on the total number of German films playing in America. “The films are essentially German propaganda,” said an industry insider. “The Nazi government will see to it that they continue to be shown here regardless of the cost.” Observing that German exchanges were “not experiencing any difficulty in bringing over pictures,” Box Office tallied the number of German imports that year at a respectable fifty-five.33

Bringing in paying audiences, however, was another matter. The number of German films clearing American customs may have held steady, but the baseline figure was no gauge of the number of German films that received commercial playdates or made a profit. In 1935, Wolfe Kaufman crunched the numbers and explained how things worked. “German imports still lead imports numerically,” he conceded, but that “means very little.” Getting a film past customs was not the same as getting it in circulation. “More than half of the films brought in and shown were played in only one or two houses. They were modest cheap indies brought in by desperate two-penny exhibs on straight percentage”—that is, with no minimal rental guarantee. “If [there was] any profit, the German producers got paid off in percentages; if not, no one much cared.” Scoffed Kaufman: “If they made coffee money, that was something.” What the Germans got out of the arrangement was a continued foothold in “a once profitable market that might yet reopen. And the German government, of course, approves for propaganda purposes.”34

The German films that filtered into America in the 1930s played almost exclusively to a small clique of German speakers either in sympathy with or agnostic about the nation of origin—with no way to tell who in the crowd were ardent pro-Nazis and who just wanted to hear the native tongue in a period piece. Of the fifty-five German imports registered in 1938, Variety reviewed only seventeen from playdates at two Yorkville theaters, the Garden and the Casino. Harrison’s Reports, the exhibitor’s trade sheet, reviewed none. If any of the films had a discernibly Nazi agenda, the reviews did not mention it. “For what negligible market there is in the U.S. for Naziland-made pics, Eva [1938] will offer more than recent importations,” Variety remarked of an above-par romantic comedy.35

The negligible market for “Naziland-made pics” was not due solely, or even mainly, to boycotts and protests from NSANL. Subtitled or not, the poor quality of the films spoke for itself. Having himself been hounded out of Germany, Wolfe Kaufman was entitled to gloat. “The Third Reich is finding it harder to make films without talent than it had suspected,” he snickered.36 For most American moviegoers, staying clear of Nazi cinema was simply a matter of taste.

With anti-Nazi sentiment strong enough to shut down German cinema in America, an avid market for anti-Nazi cinema might seem to have been ripe for exploitation. Such was not the case. American moviegoers shunned the Nazi imprint and the German tongue, but outside of a small coterie of cinephiles with Popular Front affinities, anti-Nazism on screen was also a losing proposition. Foreign cinema with an anti-Nazi plotline or subtext, usually from the Soviet Union, trickled in to New York City and usually dried up there.

As with German imports in the pre-Hitler 1930s, the venues that welcomed anti-Nazi cinema were the independent “arty theaters,” a circuit of small metropolitan venues that in the postwar era would be dubbed art houses. Occasionally, if a foreign film gained a high enough profile through aesthetic quality (Jean Renoir’s elegant Grand Illusion [1938]) or prurient interest (Gustav Machety’s scandalous Ecstasy [1933]), it might secure a booking in independent theaters that normally avoided subtitled fare. In 1939, Motion Picture Herald estimated that the highest possible number of bookings for a foreign picture—a category exempting the Anglophone British imports—was 3,500, with most imports receiving between 200 and 400 playdates.

By then too, exhibitors were tracking a bellwether shift in the demographic profile of foreign moviegoers—the replacement of linguistic allegiance by artistic taste. “The appeal of foreign pictures is to the American intelligentsia rather than to individual language groups,” asserted Motion Picture Herald, intelligentsia being a code word for highbrow types with left-wing leanings.37 For the Popular Front filmgoer, purchasing a ticket to an anti-Nazi film was the moral equivalent of donating money to the anti-Nazi cause. Patronage meant a comradely night out on the town—applauding on cue, bonding in the lobby, and spreading the news by word of mouth.

The cinematic solidarity was all the stronger when the foreign films that assailed Nazi Germany were exported by its totalitarian rival. Of all the nations with the industrial wherewithal to manufacture world-class (or would-be world-class) cinema, the Soviet Union alone invested major resources in anti-Nazi productions. To the Nazis, international Bolshevism was a threat second only to world Jewry, to which it was invariably linked, and the Bolsheviks returned the loathing in kind. Joseph Stalin, like Hitler a confirmed film buff, personally annotated screenplays and reserved for cinema an honored place as an instrument of the revolution. Ironically, the citadel of anticapitalism held a virtual monopoly on anti-Nazi cinema. In the 1930s, no one else was competing.

The passage of Soviet films into America was arranged by Amkino Corporation, the designated distributor for motion pictures made in the USSR. Formed in 1926 and run by Soviet officials based in New York, Amkino funneled the most commercially viable of Soviet cinema into America to spread the revolutionary word and accrue hard currency. First, Dmitry Vassiliev and, after 1934, Vladimir I. Verlinsky, loyal apparatchiks both, landed the choice stateside assignment of president of Amkino, operating always under the watchful eye of Soyuzkino, the film branch of the Soviet government. Fittingly, the outfit’s breakout venture into the U.S. market was the most momentous of all Soviet imports, Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925). In 1938, after Verlinsky was called back to Moscow, and figuring an American face provided a better front, Nicola Napoli, a reliable New York-born communist and Amkino’s longtime treasurer, became de facto overseer of the marketing of Soviet film culture in America.c

Amkino handled the American release of two to three dozen Soviet imports a year. Few circulated outside of a select number of sure-seaters patronized by coteries of dedicated communist filmgoers. Fewer still rose to the level of a Variety or New York Times review. Yet for the fan base, the arty cinema parlors in and around midtown New York (the 55th Street Playhouse, the Acme, the Waldorf, and the Cameo) offered a welcome relief from Hollywood false consciousness and an imaginative link with the future that was the Soviet Union. The 600-seat Cameo, with its wide aisles, marble lobby, and black-walnut foyer, was especially beloved. If the Embassy Newsreel Theater was the hot spot in town for Manhattan-based news junkies, the Cameo was the mecca for devotees of red-starred foreign cinema. The Cameo was run by the kingpin exhibitor of Soviet cinema in the United States, Matty Radin, sometimes referred to in the press as “Tovarich Matty Radin” (“Tovarich” being Russian for “comrade”). In 1932, while introducing the American premiere of Sergei Yutkevich’s Golden Mountains (1931), a Soviet-made paean to a factory strike in prerevolutionary Russia, the most famous name in Soviet cinema bestowed his personal blessing on the venue. Finding a warmer home at the theater than in the Hollywood studio system, Sergei Eisensteind praised the “the good work that the Cameo is doing in bringing communism to Times Square.”38

To the extent the films became known to the average rung of moviegoers, Amkino could thank the public relations work performed by anti-communist censors across America. Sometimes abetted by local police chiefs with ideological vendettas, city and state censor boards sliced and banned Soviet-made films with a zeal reserved for no other national cinema, especially when the Soviet imports called for workers of the world to unite against Nazism. Technically, Nazi Germany was a “friendly nation”: attacks on it were deemed a controversial intervention in American foreign policy. Censors claimed to be scrupulously neutral in ferreting out propaganda from foreign shores, but the messages from Moscow always received closer scrutiny than the messages from London, Paris, or, for that matter, Berlin.

The anti-Nazi Soviet films that made headway in the American marketplace were a select group. Gustav von Wangenheim’s aforementioned Der Kampf (1936) was the first to edge into awareness. Half Jewish and all communist, von Wangenheim had fled Nazi Germany for the shelter of Moscow, where he had no trouble assembling a German-speaking cast of seasoned actors among the growing refugee community. Der Kampf was a patented coming-of-communist-age story (a callow youth who prefers sports to dialectics ultimately sees the light) told against the background of the Reichstag fire and the heroism of the unjustly accused communist Georgi Dimitroff.

A dedicated Popular Front filmgoer might also have patronized The Oppenheim Family (1939), directed by Grigori Roshal and based on a novel by Lion Feuchtwanger, author of The Jew Suss. It weaves together the tale of a Jewish family in Berlin persecuted by the Nazis (the young son is driven to suicide by the racial theories of his Nazi professor) and the resistance of the unyielding German communist underground. The film was praised by up-and-coming New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther for its portrait of brutishly Neanderthal storm troopers, its “authentic flavor of uniformed mobocracy,” and (in a slap at Hollywood timidity before the likes of Dr. Georg Gyssling) its fearlessness in naming Nazi names “with a fine Soviet disregard for consular protests.”39

Also gaining some traction in the American marketplace, mainly on the strength of an exploitable English-language title, was Concentration Camp (1939). Directed by Aleksandr Macheret, the Soviet version of a Warner Bros. prison movie went behind the gates of the Nazi penal system for an exposé that even at the time seemed too mild. Nazi guards try to break the spirit of communist inmates, to no avail. Outside the camps, undaunted communist workers stage a strike in an airplane factory, rejecting Nazi militarism for people’s solidarity. In all the anti-Nazi Soviet films, ruthless Nazi repression only inspires the indefatigable communist party to redouble its efforts.

Besides the rampant message-mongering endemic to the species, bad subtitling, choppy editing, and technical flaws limited the crossover appeal of Soviet cinema. Placed beside Hollywood’s flashy formalwear, the pallid fare from the USSR looked drab and frumpy. “Photography ranges from topflight to sloppy, badly lighted scenes,” complained Variety of Concentration Camp. “English titles are n.g. [not good].”40 The trade paper found nothing good at all to say about The Oppenheim Family, a film pockmarked with flaws “of the sort that Hollywood solved years ago.” It lambasted the pacing (“the picture takes 97 minutes to put over an idea that Hollywood could punch home in half the footage”), the cardboard-cutout Nazi bad guys (“The Soviets seemingly cannot admit that a villain may look otherwise than villainous”), and even the gams of the leading lady (“the otherwise attractive ingénue G. L. Minovitskaya [has] the thickest ankles that ever distracted an audience’s attention”).41 Prone to clunky plotting and hectoring speechifying, the Soviet style was long on dialectics and short on thrills. New York Times critic Frank S. Nugent’s dry comment on Der Kampf summed up the reactions of moviegoers who might be sympathetic to the message but impatient with the packaging. “If the propaganda film is to be a telling instrument against Hitler, it must be used with the icy precision of a surgeon’s scalpel, not as a butcher’s cleaver.”42

As if made to Nugent’s order, a Soviet film whose plot actually wielded a surgeon’s scalpel would break out beyond its loyal communist fan base to become an authentic hit, at least by “arty house” standards. Far and away the best known and most widely circulated of the anti-Nazi films from the USSR, Professor Mamlock (1938) was the story of a noble but naive surgeon consumed by the flames of Nazi Germany a-borning. Based on a play by Friedrich Wolf, an exiled German communist playwright, and codirected by Herbert Rappaport, an Austrian-born émigré and former assistant to G. W. Pabst, and Soviet filmmaker Adolph Minkin, the film peddled a presold product. Stalwart Popular Fronters would have known Wolf’s play from stage productions by the Federal Theatre Project in New York in 1937 and in Hollywood (in Yiddish) in 1938. As the first explicit anti-Nazi production mounted by the controversial New Deal agency, the stage version of Professor Mamlock put flocks of anti-Nazi activists in theater seats. Among communist moviegoers, the motion picture version—from Leningrad not Hollywood—was highly anticipated.43

Professor Mamlock opens not on January 30, 1933, the day Hitler became chancellor, but on February 27, 1933, the day, as all Soviets and well-versed Popular Fronters would know, of the burning of the Reichstag, the German parliament building, an act blamed on a conspiracy by the Bulgarian communist agitator Georgi Dimitroff and three comrades. Since the action is set during the run-up to the critical Reichstag elections on March 5, 1933, the vote that gave the Nazis their electoral plurality, the communists are still an active, above-ground political party street fighting against the brownshirts in the name of the true proletariat. After its defeat at the polls, the ruthlessly suppressed but unbowed party apparatus is forced underground to continue the battle.

In reviewing the tumult of the early days of the Third Reich, Professor Mamlock is part history lesson and part blueprint for revolutionary action, but the spine of the story is spiritual, a parable of political conversion, communist style. Professor Mamlock (played by Semyon Mezhinsky, an Honored Artist of the Soviet Republic) is a loyal German, an enlightened humanist, and a decorated veteran of the Great War. His brilliance as a surgeon is matched only by his saintly bedside manner. He takes no money from the poor; he comforts crippled children; he keeps long hours. Beloved by his patients, revered by his staff, the kindly old caregiver floats above the upheaval on the streets, oblivious of the world unraveling around him, keeping his gaze fixed on the bacteria under his microscope lens. As if to lend immune protection from the material world, a white surgical gown covers his body, a vestment symbolizing his purity.

Alas, the good doctor is a political naïf in the new Germany, befogged in a false consciousness that estranges him from his wiser son, Rolf (Olge Zhakov), a muscular medical student whose real vocation is fomenting revolution. The two butt heads when the apolitical professor refuses to abide Rolf’s agitation under his roof. “What business have you with politics?” asks the father of his firebrand son. “Isn’t Pasteur and Koch sufficient for you? Science alone will change mankind.” “No,” retorts Rolf. “Pasteur, Koch, Marx, and Lenin!”

The professor soon learns the truth of his son’s words. The burning of the Reichstag (“we won’t allow communists and Jews to undermine our nation!” screams a radio announcer) accelerates the Nazis’ persecution of political enemies and racial minorities. The jackboot comes down hardest on the communists, who, though chased underground, continue to work for the cause—meeting in cafes, passing information, and circulating anti-Hitler leaflets.

No longer a refuge from street politics, Professor Mamlock’s hospital also falls under Nazi control. A Nazi doctor, long jealous of Mamlock and now drunk with power, sets about purging his rival, ordering Mamlock, in the middle of surgery, to stop practicing medicine. “What the Jew Mamlock does any of you can do!” he barks to the stunned operating team.

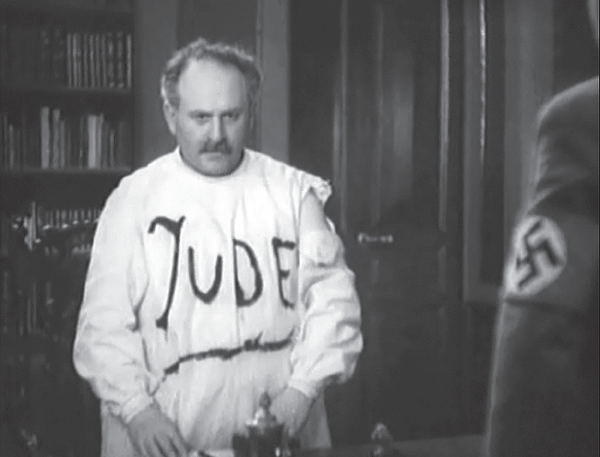

Directors Rappaport and Minkin then perform a neat operation of their own. Outside the hospital, German citizens mill in the streets, distracted by a hubbub of activity just out of sight. The crowd parts to reveal the cause of the commotion: Professor Mamlock, paraded through the street by brownshirts, the word “Jude” scrawled in big black letters across the front of his white surgical gown. It is a haunting image of ignorance defacing wisdom, of a lion of a man set upon by jackals.

Shattered, Mamlock staggers home. Brushing past his horrified wife, he locks himself in his study. From his desk drawer, he takes out a pistol—a gift bestowed on him for courage at the battle of Verdun during the Great War—and begins to write a letter.

Back at the hospital, irony ensues: a big-shot Nazi requires immediate life-saving surgery. Only the Jew Mamlock can perform the necessary procedure. When the Nazis come to implore Mamlock to return, he is still at his desk contemplating suicide, but true to his Hippocratic oath, he agrees to perform the operation. Slowly, he stands up to reveal his desecrated gown, still branded “Jude.” No, he tells his visitors, he does not want to change his clothes.

Reunited with his loyal medical staff, the professor saves the Nazi’s life. The gesture is futile. The hospital still must be “liberated from this Jew Mamlock.” Distraught beyond consolation, Mamlock walks in a daze down the hospital corridor. From offscreen, a shot rings out. Mamlock’s body is found slumped on the floor, but the old man is not dead.

“A surgeon’s scalpel”: Semyon Mezhinsky as the kindly Jewish doctor in the Soviet anti-Nazi film Professor Mamlock (1938), based on the play by Friedrich Wolf.

During Mamlock’s torment, a parallel track of action charts the exploits of the underground communist cell, led by Rolf, still working heroically under the noses of the Nazis. Several sequences play as instructional vignettes for revolutionaries in training: how to hide and distribute anti-Nazi leaflets and (Hollywood’s influence being felt even in Leningrad) how to mount an exciting rescue operation.

The plotlines and the ideological currents converge when Rolf, risking all, sneaks into the hospital and goes to the professor’s bedside. Father and son are reconciled. The old man has seen the light. Pasteur and Koch must be yoked to Marx and Lenin.

Discovered and pursued, Rolf flees, making good his escape when his love interest kills his Nazi nemesis. In the confusion, Mamlock leaves his bed and walks to a balcony overlooking the city street outside. Heedless of the soldiers assembling below, he delivers a scathing anti-Nazi speech to the gathering crowd. “Now I understand what you’re all about,” he shouts to the Nazis. While proclaiming his German patriotism, he curses the Nazis for the torture, tears, and blood they have brought to the nation. Mamlock’s denunciation ends when a Nazi machine gunner cuts him down midsentence. From the crowd, a voice yells “Murderers!”

The coda shows Rolf—still free, still fighting—at an underground cell meeting, exhorting his brave comrades. He clenches his fist in the arm-upright gesture of the Red Front, the universal sign of communist solidarity. If a Hollywood film ends with a romantic clinch, a Soviet film ends with a clenched fist.

Professor Mamlock was stirring stuff, and not just for communists. The stiffness of Soviet agitprop was softened with human touches and comic relief and enlivened with well-paced action sequences shot in the streets of Leningrad. The music track (the rousing theme was by Y. Kochrov and M. Timofeyev) and the sound design (the click-clack steps of the brown-shirts on pavement) came in for special praise from critics.

From a non-Stalinist perspective, however, Professor Mamlock was not without ideological difficulties. The party-line valorization of the German working class makes the Nazis seem more like an invading army than an expression of popular will. In the elaborate underground network operating around Berlin, seemingly every German except those in brown shirts embraces the communist cause. Just where did all those marchers at the Nuremberg rallies come from? According to Professor Mamlock, and contrary to the Nazi slogan, the German Volk are not one with the Reich and the Führer.

The addled class dynamics were clouded over by a coincidence of historical timing. Premiering on November 7, 1938, on home turf at the Cameo Theatre, Professor Mamlock lived up to the hoariest cliché of ad-pub taglines: as timely as today’s headlines. By grim serendipity, the stateside release coincided with the surge of nationwide revulsion over Kristallnacht, the antisemitic orgy of destruction that erupted throughout the greater Reich two days later. “It is Hitler who is conducting a grisly promotion campaign across the world’s press, driving home the film’s call for unity with each terrifying headline,” proclaimed the Daily Worker, the broadsheet of the Communist Party USA. “Audiences coming from the Cameo walk the short half-block to Times Square and look up at the electric news bulletins banding the Times Building and feel no transition from the mood of the picture.” For once too the Cameo was packed with crowds made up of more than the true-believing regulars. Thrilled to support a film that was not just preaching to the converted, the Daily Worker figured that “a large percentage of the nightly audience at the Cameo have never before witnessed a Soviet screenplay.” Mamlock’s hospital-bed conversion and his defiant speech from the balcony seldom failed to inspire cheers and applause.44

Having endured years of stilted agitprop and inept melodrama, critics from across the Popular Front relished the chance to trumpet a film that combined righteous politics and—finally—impressive artistry. The New York Times praised a “great picture,” and the New York World-Telegram lauded “a fierce and shattering indictment of Nazi terrorism.” Even the Hollywood trade press amplified the buzz. “Strong anti-Nazi propaganda dished up with entertainment elements which carry a load of visual sock,” said the Hollywood Reporter. “Gruesome flashes of whippings, mass murders, and various prosecutions leave a lasting memory.”45 It was no surprise that in a year-end survey of the year’s best movies, the Daily Worker hailed Professor Mamlock as “the most significant picture of the year,” but the National Board of Review also ranked it as one of the best foreign films of the year.46

Seizing the momentum, Nicola Napoli, Amkino’s hands-on manager, made a bid to cross over into the American mainstream by doing something the Soviet importer had never done before. Amkino applied for a Code seal for Professor Mamlock.

As usual, the Breen office was ahead of the curve. Unbeknownst to Amkino, Francis Harmon, head of the East Coast branch of the Production Code Administration, had already checked out the film with the paying customers at the Cameo. “The film is a powerful anti-Nazi story with some incidental boosts for Communism,” Harmon informed Will Hays in a carefully worded memo copied to Breen on the coast. “In our opinion it conforms to the Code section which provides that ‘the history, institutions, prominent people and citizenry of other nations shall be represented fairly.’” Elaborating, Harmon set off in quotes the distinction that, since I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany (1936), had guided PCA policy toward anti-Nazi cinema:

This section does not state that the people and other nations must always be portrayed sympathetically. It says “fairly” and in our judgment the scenes portrayed are an accurate reflection of what has actually taken place in Nazi Germany. In fact the present German government has boasted of just such incidents as are herein portrayed.

Harmon then broached another topic very much on the mind of the MPPDA:

Refusal to issue [a Code] seal because of dislike of the content of the film subjects us to legal action as constituting “an unreasonable restraint of foreign commerce.”... The Association [the MPPDA], as public relations advisor to member companies, may well continue to advise producers not to make such controversial films, and to advise distributors not to distribute such films, but when such a film made by a foreign, non-member producer, is submitted to us for review, it appears that our responsibility is limited to a determination whether or not the film conforms to the Code.47

Harmon was giving voice to a pressing concern throughout the industry. Being a front for a cartel, the MPPDA was rightly fearful of indictment as a monopoly in restraint of trade. Under FDR, the federal government had begun to cast a jaundiced eye on the practices of Hollywood’s vertically integrated oligopoly. In July 1938 the worst fears of the motion picture industry were realized when the Department of Justice brought suit against the three-tiered system of production, distribution, and exhibition practiced by the major studios.e With government lawyers demanding an end to the lucrative racket, the MPPDA thought it prudent to deflect charges of monopoly by a show of equal treatment to the foreign competition.

The MPPDA-PCA decision makers were also not insensitive to a shift in the cultural ground. By early 1939, as Professor Mamlock wound its way through the Code bureaucracy, Nazi perfidy was a familiar theme in newspaper articles, radio commentary, and even the newsreels. Warner Bros.’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) was nearing completion after a bright green light from the Breen office. Even though the first film to articulate the emerging American consensus on Nazi Germany was from the Soviet Union, official Hollywood could no longer deny expression to so widely held a sentiment.

Partly as a bargaining chip in the ongoing lawsuit brought by the Department of Justice, partly as a sign of the times, Professor Mamlock was granted a Code seal. It was the first Soviet-made film to receive the imprimatur of the Breen office, indeed the first time that Amkino had bothered to apply for a Code seal. None of the political content, either anti-Nazi or pro-communist, was tampered with. The only required deletions involved a mild sexual allusion and a glimpse of cruelty during a “third degree” (that is, interrogation) scene at Nazi police headquarters. MPPDA secretary Carl E. Milliken confirmed the official clearance with the standard qualification: “Professor Mamlock conformed with all the standards of the Production Code and [our decision] has nothing to do with approval or disapproval with the theme of the picture.”48

The hurdle of the Breen office may have been cleared, but Professor Mamlock still needed to run a coast-to-coast gantlet of municipal and state censor boards. Staffed by political hacks and busy-bodies-about-town, the boards were often far more likely to fold under pressure from a foreign consul or local women’s group than was the stiff-necked Breen out in Hollywood. Breen followed codified regulations. Local censors followed their own erratic druthers.

At first sight of the hammer and sickle, many censor boards and police chiefs conspired to impede circulation of Amkino releases. A typical instance involved The Baltic Deputy (1937), a biopic based on the story of Kliment Timiryazev, a botanist and early supporter of the Russian revolution touted as the “Luther Burbank of Russia.” Fearing the Soviet-made paean to “red” propaganda might “incite people to destroy government,” the Pennsylvania State Board of Censors banned it. When Amkino took the board to court and its attorney asked chairwoman Mrs. A. Mitchell Palmer why she had banned the film, Mrs. Palmer replied, “The film contains the most magnificent acting I’ve ever seen, but I don’t like communism.”49 Amkino ultimately won the case.

Living up to its reputation as the nation’s preeminent chamber of blinkered philistines, the Chicago Board of Censors clamped down hard on the anti-Nazi Soviet imports. It banned The Oppenheim Family as propaganda that “exposes to contempt a class of citizens.”50 It banned Concentration Camp for being “a vicious propaganda picture of an inflammatory type which could not fail to provoke hatred, bitterness, and dissension.”51 It banned Professor Mamlock for being likely to incite a “near riot.”52

Another group determined to keep anti-Nazi cinema off American screens was the Nazis. German consular officers across America protested to mayors, Nazi-inspired citizens groups appealed to municipal censors, and German-language newspapers editorialized against Amkino insults to the Reich.

Yet despite the pressure from foreign consuls and homegrown Nazis, the support of sympathetic critics and a widespread reluctance to censor political speech (as opposed to immoral images) lent even the Soviet films a layer of protection. Also, by 1939, the same currents that had lifted Professor Mamlock to arthouse prominence and Code clearance worked to shield the anti-Nazi films from suppression. Initial bannings by boards were often overturned under pressure from the public or a ruling from a judge. As with the newsreels, the editorial pages of the nation’s newspapers rallied to the defense of politically minded films with an alacrity seldom summoned when Hollywood was censored for immorality. Besides, no one could argue that Soviet cinema was too sexy or salacious.

Exiles, refugees, expatriates—the tide of talent that would enliven or, more usually, darken the tone and texture of Hollywood cinema—were the great by-product of the Nazi campaign to cleanse the fatherland of untermenschen, subhumans not fit for life in the new Germany. Few of the motion picture artists who arrived in Hollywood after 1933 were wretched or poor, but many were politically aberrant, communist or leaning so, and almost all were racially unacceptable to the Nazis—Jewish, part Jewish, or married to Jews. Many of the refugees were doubly cursed, being ethnically and ideologically repellent to the Third Reich.

The influx of refugees skilled in the art of moviemaking was a backhanded confirmation of the prestige accorded their profession in Nazi Germany. Unlike the American government, whose policy toward creative expression was mainly benign neglect, the Nazis honored intellectuals and artists as avatars of Aryan culture, none more so than those working in the most valued of propaganda media. Talented filmmakers of good stock and reliable opinion were pampered; the rest were persecuted. Purged from Germany and later Austria, producers, directors, actors, writers, musicians, and craftsmen of all sorts were forced to seek work and find succor elsewhere—Paris, London, and, the promised land, Hollywood. As usual, Variety came up with a glib coinage for the new migrants in town: “Nazi scrammers.”53

Dazzled by the picture-perfect climate of California and the well-oiled machinery of the studio system, the transplanted filmmakers were alternately delighted and disoriented, relieved to have escaped from the terror of Nazi Germany and anxious about adjustment to a new life. In assimilating into Hollywood, each confronted problems peculiar to his or her occupational specialty. Some clung fervently to the politics that forced their exodus, others dropped their party affiliations quicker than their accents.

An impediment shared by all the prominent names was that any Hollywood film employing a well-known German refugee was tagged as contraband and forbidden import into Germany. When submitting a film for German release, the Hollywood studios were required to certify that the production was not made by “Jewish emigrants.” To the Nazis, “a Jewish emigrant” was defined as a “non-Aryan” who had emigrated after January 30, 1933, and who was considered “to have left the country in silent protest to the present regime.”54 To ship films into Germany, the studios either lied outright on the official forms or wiped the offending name from the credits prior to export.

On July 1, 1933, when the purging of Jews from the German film industry became official, producer Samuel Goldwyn telegrammed reporters. “I plan to inaugurate a movement here in Hollywood immediately to welcome to our motion picture ranks those artists, producers, writers, and directors who, because of their Jewish heritage, are being deprived of a means of livelihood and an outlet for their talent. We not only invite them here, but what is more important, we need them,” he declared, overlooking restrictive immigration laws that blocked easy entry. “Many of the people who have been engaged in making pictures in Germany are among the most capable in the world, and the German government cannot but suffer a grievous loss because of the steps it has taken.”55 Berlin’s loss would be Hollywood’s gain—and at a bargain price.

Money being good anywhere, financially solvent producers made the smoothest transition to filmmaking outside of Germany. After twenty-six years in the German film industry and sixteen as production head at Ufa, Erich Pommer landed on his feet first in Paris, working for Fox at the Joinville Studio, later in London, and then, for good, in Hollywood.56 “Where else can one find such lovely days?” he enthused during the shooting of his aptly titled debut for Fox, Music in the Air (1934). “The studios are the last word in efficiency. Here are the best brains in the biz, the best technicians and by far the best facilities for turning out super productions.”57

In 1934 the theatrical impresario Max Reinhardt was welcomed with fanfare at Warner Bros., where he was hired to codirect a big-budget all-star production of William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935). To smooth Reinhardt’s transition, a codirector was assigned to shepherd him through the studio system, William (formerly Wilhelm) Dieterle, himself a German import and a former Reinhardt protégé. (A colorful character who wore white gloves on the set and directed in “pig Latin with a German accent,” Dieterle had been under contract at Warner Bros. since 1930.)58 Reportedly, the combined reputations of Shakespeare and Reinhardt gave actors as cocky as James Cagney (as Bottom) and Mickey Rooney (as Puck) a case of the butterflies during rehearsals.59 Reinhardt had his own adjustments to make in the move from Neubabelsberg to Burbank when he glimpsed a scene of unseemly modesty on the set. The diaphanous gowns of the girls playing the wood nymphs in A Midsummer Night’s Dream should be transparent not veiled, he ordered. He was told that not even Shakespeare was exempt from the Production Code.

Fluent in the universal language of music, composers also adapted readily. Franz Waxman was recruited by Erich Pommer to score Music in the Air (1934), secured his reputation with the ethereal strains to Bride of Frankenstein (1935), and became one of the most common credit lines in classical Hollywood cinema, earning twelve Academy Award nominations and two Oscars. Frederick Hollander, who under the name Friedrich Hollaender had written the score for The Blue Angel (1930), followed Marlene Dietrich to Hollywood to provide her with theme music and signature songs. Viennese composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold, a former child prodigy hailed as the new Mozart in his home metropolis, first left Vienna in 1935 to score A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Reinhardt and quickly became a go-to “cleffer” at Warner Bros., earning Oscars for his rousing scores to Anthony Adverse (1936) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). He left Austria for good weeks before its annexation by the Nazis.

Critics had to be pretty tone deaf not to tune in to the new beat in Hollywood cinema. “Invasion of Hollywood by world’s ace composers has gained marked headway in 1936, and some of the most interesting and important musical creations anywhere were composed directly for [the] screen” noted Variety in a year-end wrap-up that never mentioned the words “refugee from Nazism” but included a roster of same among the composers whose scores had proven “memorable for music lovers, agreeable to the popular ear, and inspirational to film producers.”60 The German Jewish composers who conducted the soundtracks to the lush Hollywood melodramas of the 1930s and 1940s lent an (ironically) operatic Wagnerian whoosh to the Tin Pan Alley strains of American pop romance.61

The linguistically dependent ranks of writers and actors found adjustment more difficult. Few possessed the verbal facility of Billy Wilder, who left Germany in 1932 and came to Hollywood by way of Paris in 1933. Wilder’s second-language ear for the lilt of American slang spiced up the dialogue tracks of all his films, though even the witty Wilder always collaborated with a native speaker to fine-tune his screenplays.

Natural chameleons though they were, many actors found the change of habitat wrenching. The screen credits of the marquee stars of Germany and Austria meant nothing to the fan magazines in America. Moreover, as the German voice on radio and in the newsreels came to sound ever more crudely barbaric to the American ear, what had once been a language of husky romance and exotic sophistication took on a guttural and discordant timbre. Refugee actors were caught in a cruel bind. The German-accented character parts they might have been typecast for were also drying up—too sensitive for domestic consumption and too offensive to slip by Nazi censorship. Not until American entry into World War II would a seller’s market for German-accented villains restore the fortunes of German thespians, Jew and non-Jew, who could play to Central Casting type. Conrad Veidt, the somnambulist from the German Expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and the star of The Wandering Jew (1933) and Power (1934), metamorphosed into a reliable Nazi scoundrel, most memorably as the slithery Major Strasser in Casablanca (1942).

Blessed with the mastery of a unique skill set, successful German directors might write their own ticket. The prize catch of all—Ernst Lubitsch—had arrived in 1922, prospered, and showed no desire to return to a nation in perpetual meltdown. In 1932, back in Berlin for a visit, he felt the bad vibrations in the air. Asked by Bella Fromm, the famed diplomatic columnist for the Vossische Zeitung, whether he planned ever again to work in Germany, he shook his head. “That’s finished,” he told her. “Nothing good is going to happen here for a long time. The sun shines every day in California.”62

Several rungs down from Lubitsch were the directors Ludwig Berger and Reinhold Schuenzel. Berger had been commuting back and forth between Berlin and Hollywood, Ufa and Paramount, since 1928. The talkie revolution pushed him back to Germany, where in June 1933 he had the lonely distinction of being “the only Jewish Ufa director at present,” working on one of the last of his Weimar-conceived projects, Walzekrieg.63 When production wrapped, Berger lit out for France, the Netherlands, and Britain, but never found his way back behind the camera in Hollywood. For his part, Schuenzel, the formerly bankable director of Amphitryon (1935), found himself suddenly out of favor for considering a project that took a satirical look at dictators. In 1937 he fled Germany for Hollywood and landed a contract with MGM to helm froth such as Ice Follies of 1939 (1939) and Balalaika (1939). (Both Berger and Schuenzel returned to Germany after the war.)

Director Henry Koster, formerly Herman Kosterlitz, was just getting his career off the ground when the Nazis came to power. He worked in Austria, Hungary, and Italy before Joe Pasternak, Universal’s overseas production chief, brought him to Hollywood in 1936. He hit pay dirt immediately with Three Smart Sisters (1936), where he guided 14-year-old Deanna Durbin to stardom. Koster rode his meal ticket to five more starring vehicles, a franchise that helped keep Universal in the black during the 1930s. A studio workhorse, he enjoyed a 40-picture career in Hollywood.

“The sun shines every day in California”: Ernst Lubitsch and his wife, British actress Vivian Gaye, relaxing in San Bernadino, CA, 1939.

The most prominent director to flee Germany was Austrian-born Fritz Lang, the internationally renowned genius behind the sentimental Nazi favorite Die Nibelungen (1924), the dystopic science fiction fantasy Metropolis (1927), and the crime melodrama M (1931). The story Lang told of his escape from Germany was as nerve-wracking as any of the dark thrillers he made in Hollywood: that soon after the Nazis took power, Joseph Goebbels offered to put him in charge of the German film industry. “But my mother was part Jewish!’ protested Lang. “I decide who’s Jewish and who’s not Jewish,” hissed Goebbels, whereupon Lang went directly from the propaganda minister’s office to the Berlin station and boarded the first train to Paris. (The truth was more prosaic: Lang quietly closed out his affairs, packed up his art collection, and left first class.)64 Monocled, impeccably dressed, an autocrat on the set, Lang might have been sent over from Central Casting after a call for a tyrannical German director type. His first film for MGM, Fury (1936), was a commercial and critical success, a close-to-the-bone social-problem film in which a howling mob tries to lynch a man unjustly accused of kidnapping.

The fresh-off-the-boat immigrants—or, more likely, freshly disembarked from their second-class berths on the Super Chief at Union Station, Los Angeles, the terminal point for the luxury rail liner—rubbed elbows and competed for jobs with the pioneers who had voluntarily left the Weimar Republic in the 1920s and early 1930s. Reportedly, some of the original pilgrims were miffed at being lumped in with the come-latelies. “One of the most remarkable angles on the Hitler thing, as far as filmers are concerned, is the almost unanimous care which former Germans take in pointing out they’re not exiles,” reported Variety in 1933. “Again and again, former German filmers who left the country, complain of being put in the refugee class, pointing out they left of their own volition, they left before the persecution actually started, etc. In some cases it’s a matter of thinking they may get back some day; in most it’s the business of not wanting to be pitied but standing on their own as directors, writers, and actors rather than as refugee talent that needs bucking up.”65

Perhaps—but many of the Weimar expatriates joined together and held out a helping hand to their desperate kinsmen. Ernst Lubitsch, Marlene Dietrich, and Carl Laemmle bankrolled escapes, signed affidavits, and put newly arrived talent on the studio payrolls. In 1938 the personal gestures of charity were made official with the establishment of the European Film Fund, through which solvent refugee artists tithed 1 percent of their salaries to sustain refugees down on their luck.

None was more generous or energetic than Paul Kohner, who with Lubitsch cofounded the European Film Fund. Born in 1902 to wealthy and trade-connected parents in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he met his future in 1920 while interviewing Carl Laemmle. The Universal chieftain was back in his homeland, soaking in the baths at Karlsbad. During the interview, Laemmle offered the 18-year-old a job as his personal assistant. By 1928, Kohner was overseeing Universal coproductions in Germany. When Hitler forced the company to pull up stakes, he fled first to Paris and then returned to Hollywood. In 1938 he opened up the Paul Kohner Agency to broker talent, but his real job in the 1930s was as a one-man refugee relief center for the exiled German community in Hollywood. Wired in to all the casting departments of the majors studios, he procured visas and employment for scores of adrift Germans.66

Many of the refugees who landed in Hollywood had known each other since their salad days in Weimar Germany. Socializing and working together, they bonded in a mutual support network. Ernst Lubitsch personally supervised a screen test for Reinhold Schuenzel’s 17-year-old daughter Annamarie for a bit part in The Shop Around the Corner (1940).67 Helped along by his friends, Schuenzel himself moved from the director’s chair to the other side of the camera. In 1943, doubtless savoring the irony, Lang cast his former colleague and fellow exile as a Gestapo officer in Hangmen Also Die! (1943), a dramatization of the assassination of the notorious S.S. Gen. Reinhard Heydrich by the Czechoslovakian underground.

Not all lived out the Hollywood dream. The former German film star Hans von Twardowski took character parts, bit roles, and extra work. Others changed professions: the actor and director Ulrich Steindorf moved into publicity work. Director Joe May, one of the brightest lights of Weimar cinema, floundered in the Hollywood studio system. Brought over by Pommer to direct Music in the Air, a box office failure, he was soon relegated to B movies at Universal, working with the Dead End Kids and Lon Chaney Jr. For the ill-starred, the demotion from name-above-the-title to has-been was an ignominious fall made tolerable only by considering the alternative back home.

Before too long, even the Nazis recognized that the hemorrhaging of motion picture talent had to be stanched. Perhaps the racially acceptable artists could be lured back? “German government has officially asked these expatriates (except those of Jewish faith) to come back and take their part in the German film biz of today, no matter what their tie-ups elsewhere,” Variety reported in 1933.68 Any artist who failed to return to the Reich was branded the moral equivalent of a Jew. “It is considered unpatriotic—yes, even as treason to the country—if now, in the midst of the great work of rebuilding in the German film world, German artists combine abroad with film companies or film workers who either emigrated from Germany as non-Aryans or who are hostile to Germany or participate in agitation against Germany,” warned the Film-Kurier, once the German film industry’s answer to Variety, now a Goebbels mouthpiece. “Such Aryan German film workers employed abroad against German interests run the risk of being placed beside non-Aryans in the future.”69

A few non-Jewish, non-left-wing German actors—homesick, afraid of being tarnished as non-Aryans, or having run aground under the Hollywood palms—returned to the fold. Beckoned to Hollywood by a five-year contract with Paramount, Dorothea Wieck, star of Maedchen in Uniform (1931), returned in 1934 and enjoyed enormous success in the cinema of the Third Reich. Emil Jannings, who won the very first Academy Award for Best Actor for his work at Paramount in The Last Command (1928) and The Way of All Flesh (1928), repatriated to Germany with the onset of talkies to become a prize show horse for Joseph Goebbels.

While the refugee community soaked up the sun, learned English, and hustled for work, Hollywood in turn absorbed the nervous tics and night terrors of the refugee sensibility—shadowy and off-kilter, alienated and paranoid, foggy and fearful. The denizens of “Weimar on the Pacific” injected a gloomy weltanschauung into Hollywood’s bright horizons and happy endings, a touch of evil that in the postwar era blossomed into what sharp-eyed French critics called film noir.

Back in the Greater Reich, a few motion picture artists paid the ultimate price for being Jewish or anti-Nazi. In October 1936 the German actor Helmuth Klonka was condemned for high treason and executed.70 That same year, Werner Krauss, the Austrian director and financier, despondent that Nazi racial laws blocked his productions from Germany, committed suicide in Vienna. “He had made one big mistake,” the obituary in Variety noted. “He made pictures in Austria with casts which did not get the approval of the German film chamber—that is to say, they were not 100% Aryan.”71 In 1938 the Austrian actor, comedian, and cabaret performer Fritz Grünbaum was arrested and imprisoned in the concentration camp at Dachau, where he died in 1941.

Little wonder that longtime expatriates burned their bridges and pledged new allegiances. “Herr Ernst Lubitsch, one-time Berlin actor, but for years a Paramount director in Hollywood, has finally gotten around, after some eleven years, to the important business of declaring allegiance to the land of opportunity, blue eagles, high salary checks, and double features,” trumpeted Motion Picture Herald in 1933, when the greatest of all Weimar imports applied to become a U.S. citizen.72 Marlene Dietrich waited until the fateful year of 1939 to make it official. “I am doggone glad to be a niece of Uncle Sam,” she told reporters. “The United States is the most glorious and wonderful country in the whole wide world.”73

“Doggone glad to be a niece of Uncle Sam”: Marlene Dietrich signs her final U.S. citizenship papers in Los Angeles, June 9, 1939.

For their part, being all too familiar with the value of identity papers, the newer arrivals wasted no time in officially signing up for an American passport. Fritz Lang took out his naturalization papers within months of arriving in Hollywood. Billy Wilder treasured the moment a sympathetic consular officer in Mexico stamped his passport with a precious entry visa. After fleeing Nazi Germany, Conrad Veidt became a loyal British subject, but died a true citizen of Hollywood, succumbing to a heart attack in 1943 while playing golf at the Riviera Country Club in Pacific Palisades.

Given conditions at home, few of the exiles suffered from true homesickness. The Germany they remembered no longer existed.

In a sense, the film people hounded out of Nazi Germany were lucky. Persecuted from the first days of the Nazi takeover, they got the message early and fled well in advance of the holocaust that consumed their kinsmen. Unlike shopkeepers and businessmen, tied down by inventory and contacts, or medical and legal professionals, with clients and credentials, artists were not rooted to real estate or dependent on loyal customers. Itinerant by profession, mobile by inclination, they were a class of professionals ready to hit the road on short notice, carrying little more than a valise and their native talent. Pack a bag, hop a train, walk up a gangplank, and sail into a new life.