In the waning days of 1937, Martin J. Quigley, publisher and editor in chief of Motion Picture Herald and coauthor of the Production Code, sensed a danger looming over the industry that was more his vocation than business. “There remains in the eyes of the radical propagandists one medium of expression and one influence upon public opinion which thus far vainly excites their envy,” he warned. “That medium is the motion picture.” Fortunately, Hollywood had “escaped the blight of radical propaganda,” but the message mongers were lurking just outside the studio gates, ready “to muscle in, gain an influence over the production of the motion picture, and then use it for the propagation of their own notions of world reform.”1

Quigley was right to detect deviations from the path of fair-weather entertainment. On screen, Hollywood was inching toward the creation of narratives more in tune with the sentiments of the directors, screenwriters, and actors who packed the meetings of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League and the Motion Picture Artists Committee. After years of turning a blind eye, the major studios were facing up to the threat from Nazism—fitfully, allegorically, with concessions and compromises, but unmistakably and undeniably.

The ominous news from overseas was a bracing inspiration. An unbroken string of victories lent a frightening momentum to the forward march of the European dictatorships—the invasion of Ethiopia by mechanized Italy, the victories of the fascist-backed Rebels in the Spanish Civil War, and the territorial acquisitions that, without firing a shot, had extended Nazi hegemony from the Saar to the Sudetenland. To read the headlines or watch the newsreels was to see American-style democracy on the wrong side of history.

In January 1938, William E. Dodd, retiring after four and a half years as U.S. Ambassador to Germany, went before the newsreel cameras upon his return to America and spoke with a freedom that the language of diplomacy had heretofore constrained. “Living in Europe these days is profoundly discouraging,” he said. “Nazism and fascism are gaining ground everywhere. This is a world crisis, the greatest crisis since Napoleon.” Dodd kept up his warnings, on radio (including broadcasts over Warner Bros.’ KFWB), and in speeches to the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League and any other group that would listen.

But if some in Hollywood wanted to shout out a warning, commercial and political constraints conspired to keep the medium tongue-tied. In 1936, reviewing Fires in May, an anti-Nazi novel by exiled German writer Ruth Feiner, Wolfe Kaufman, Variety’s former Berlin correspondent, now safely situated at the paper’s New York office, measured the spinelessness of an industry always on the lookout for box office material but prone to flinch at the first sign of controversy. “Too closely related to politics to be picture material,” he judged, “but interesting reading for the thinkers.”2 By mutual consent, the thinkers were not interested in Hollywood and Hollywood was not interested in thinking.

Besides the tug of commerce, the bludgeon of what Hollywood called “political censorship” stifled creative options. The phrase referred to the onerous deletions in film content mandated by city and state censorship boards, as distinct from the salutary “self-regulation” performed by the Production Code Administration on behalf of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. Studio filmmakers accepted the notion of censorship per se and acceded to the moral policing of the Breen office, but they chafed at the suppression of morally sound motion pictures on purely partisan grounds. “I am definitely against filth and vulgarity on the screen, and I am 100% in favor of keeping that sort of thing off the screen,” said producer Walter Wanger, a center of gravity for liberal Hollywood opinion, “but I am also 100% against people who try to censor screen entertainment for their own interests.”3

Of course, some of the people Wanger berated worked for the MPPDA. Spooked by Blockade (1938), Wanger’s intervention into the Spanish Civil War, and concerned that it might embolden imitators, the MPPDA was reported to be considering the adoption of an amendment to the Production Code prohibiting films “containing controversial subject matter of a political or propaganda nature,” a charge the association denied. “The Hays office will never attempt such a ban,” an MPPDA official insisted. “The Code doesn’t have anything to do with politics or propaganda and an amendment to it ruling out such films hasn’t even reached the conversation stages.”4

Nonetheless, the Hays office had always discouraged the production of politically sensitive motion pictures, not needing the authority of the Code to act on what it considered “the good of the industry as a whole.” In 1936, when MGM contemplated a screen version of Sinclair Lewis’s novel It Can’t Happen Here, a dystopic vision of a fascist takeover of America, the Breen office, acting on behalf of headquarters, squashed the notion before the cameras rolled. Likewise, in 1937, despite the enthusiasm of Irving Thalberg for the project, MGM dropped plans to adapt Franz Werfel’s best seller The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, a searing indictment of the Armenian genocide, after protests from the Turkish and French governments. Unlike city and state boards, who suppressed films after completion, the Hays office strangled projects in the crib.

Outside Hollywood, however, the popular arts were lining up solidly behind the Popular Front. While Hitler blackened the headlines, the theatrical world regularly mounted anti-Nazi stage productions—indeed, sometimes at government expense under the auspices of the Federal Theatre Project. On the radio airwaves, editorial commentary and news reporting sent out anti-Nazi alarms that grew louder and louder as the decade went on. Even the tone of the newsreels became more cautionary and condemnatory when covering Nazi Germany. Only big-screen entertainment seemed oblivious to the grim tidings in the news of the day.

Yet even Hollywood was changing incrementally, pushed along by a personal reason the major studios had for getting into the anti-Nazi business. In pace with its territorial gains, Nazi antipathy toward the American motion picture industry had intensified. From 1933 on, Hollywood had endured an escalating series of bizarre censorship edicts and confiscatory trade policies. By 1937 “the suppression in Germany of American box office hit pictures on unknown pretexts” combined with Nazi consul Dr. Georg Gyssling’s meddling in Hollywood production “had aroused American film interests to a high state of resentment against Nazi policies,” noted the Hollywood Reporter decrying the “Hitler fist” pummeling the industry.5 On January 1, 1939, the door to Italy was closed completely when the Fascist government took drastic protectionist measures that effectively shut out all Hollywood imports. With more to resent and less to lose, Hollywood’s backbone stiffened—or maybe the motion picture industry just shrugged its collective shoulders, figuring that with no percentage in placating the Italians and the Nazis, why not bait them?

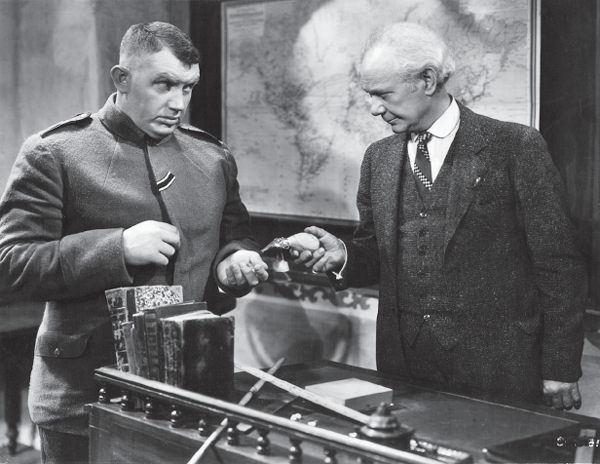

The Popular Front takes center stage: a scene from Friedrich Wolf’s anti-Nazi play Professor Mamlock, produced by the Federal Theatre Project of the Works Progress Administration, at Daly’s Theater in New York, April 13, 1937.

As the major studios made tentative incursions into foreign affairs, the actions were cheered or denounced by the interested parties watching from opposite sides of the stands. In a sense, two fifth columns operated behind the scenes in Hollywood—the anti-Nazi activists who sought to inject democratic ideals into Hollywood cinema and the pro-Nazi axis, foreign and domestic, who sought to deflect any criticism, implied or explicit, of Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany. However, not all of the opposition to antifascist moviemaking came from overseas. A third party of native-born opponents staged their protests from the hearing rooms of the United States Congress. When Hollywood fought back against “the Hitler fist” with a few gentle jabs, it was hit with counterpunches from Rome, Berlin, and—in a shot very much below the belt—Washington, D.C.

On March 24, 1936, in what looked liked a press agent’s plant but was not, the front pages of the New York dailies were filled with the alarming news that Benito Mussolini had nationalized the key defense industries in Italy in preparation for war. “This plan is dominated by one premise,” the Italian dictator bellowed, “the inevitability of the nation’s being called to war. When? How? Nobody can tell. But the wheels of destiny run fast. This dramatic eventuality must guide all our actions.”6

That same night, a sold-out crowd packed the Shubert Theater on Broadway for the New York premiere of a new play by Robert E. Sherwood, former film critic, famed playwright, and A-list screenwriter. Mounted by the Theatre Guild, and featuring the first couple of the American stage, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontaine, the production was a hot ticket sizzling with advance buzz. Along with Lunt stretching his chops as a music hall hoofer and Fontaine flouncing about in a blonde wig, the playbill promised song, dance, laughter, chorus girls, and social satire literally as timely as the day’s headlines. A semi-backstage musical, the plot centered on a theatrical troupe detained by the Italian government in the cocktail lounge of an Alpine hotel. Musical interludes, romance, wisecracks, war profiteering, and international chicanery ensue. “It is definitely anti-Fascist, anti-Nazi, and anti-war, and the audience had an extra thrill because of the prevailing headlines over European news in the papers of the day,” noted the New York Times.7

At the Hollywood office of the Production Code Administration, Joseph Breen’s antennae were already tingling. “Please endeavor to see as soon as possible the new Hunt-Fontaine play titled Idiot’s Delight and telephone me your reaction especially from a policy angle,” Breen telegrammed Carl E. Milliken, the New York–based troubleshooter for the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America.8 Perhaps Millikin might combine a bit of business with an evening on the town, Breen suggested, and get back to him with an informal review?

Millikin’s review is not recorded in the files of the Breen office, but elsewhere the production met with universal praise. It played for 300 performances on Broadway and enjoyed huge success on the road. It won the Pulitzer Prize for the year’s best drama. Naturally, it also attracted the attention of Hollywood producers hungry for a presold property with motion picture potential. Thinking the play a perfect vehicle for Clark Gable and Greta Garbo, MGM scooped up the screen rights and hired Sherwood for the adaptation.

Representatives of the Italian government had also followed the fortunes of Idiot’s Delight from opening night onward. Upon hearing of the MGM deal, Fulvio Suvich, the Italian ambassador to Washington, immediately contacted Frederick L. Herron, the MPPDA’s foreign manager, to communicate his government’s displeasure. “Needless to say, if it is made in anything like the form of the stage play, the company producing it will have all their pictures banned in Italy and France, and there will be trouble all over the rest of the world,” Herron fretted to Breen. “I imagine that if Metro are going to make it that they will clean it up from the international standpoint, but I think you ought to keep your eyes on the production if and when it occurs because it is full of dynamite.”9 Having already smelled trouble, Breen didn’t need Herron to warn him about a possible detonation.

The pressure from foreign governments, continued Herron, was “unfair and ridiculous, but the wall is there and if we expect to sell in those markets we must meet the conditions of such markets. It is their country and they have, of course, a perfect right to say what shall be brought in.” After all, U.S. Customs officers and censors in the United States had clamped down on Ecstasy (1933), the scandalous German-Czech import that had unveiled Hedy Lamarr dashing au natural through nature, “a film acclaimed throughout Europe as a great work of art.” Herron poured out his woes to Breen, who was all too familiar with the hyper-sensitivities of foreign nationals:

I had a long talk with the Italian Ambassador in Washington yesterday over many things, among them the trouble over using Bob Sherwood on the scenario of Marco Polo.…a The Ambassador had correspondence from his Foreign Office in Rome stating that should Bob Sherwood’s name appear on that picture, as Marco Polo is considered in Italy one of their great historical characters, the press of Italy would take the matter up and the picture if it were shown there be hissed in the theater and there would be a vicious press campaign that could spread all over Italy and Italian possessions.

Herron lamented the injustice of the decision, but the Italian ambassador remained unmoved, saying “that Bob Sherwood’s name was poison to the Italians due to the fact that he wrote the stage play Idiot’s Delight.”10

Meanwhile, Breen was having problems of his own with the Italian diplomatic corps on the West Coast. On May 12, 1937, he had lunch with the Italian consul, Duke Roberto Caracciolo di San Vito, who reiterated that “his people had been seriously offended” by Sherwood’s play, especially the depiction of the Italian officers, and that a screen version would be “violently opposed” by the Italian government. A former consular officer himself, Breen tried to negotiate with the duke on behalf of MGM. “After considerable discussion back and forth, the consul authorized me to state to Metro that if the Company would change the title, and if the finished picture was inoffensive to Italians, and if, further, as little mention as possible was made of Mr. Sherwood, he felt that he could persuade his government to interpose no further objections to the filming of this story.”

Breen phoned MGM producer Hunt Stromberg and passed on the Italian’s terms. Stromberg refused to sign on, arguing that the title and playwright were presold assets in the American marketplace and had to be retained. However, in the spirit of compromise, MGM would be willing to change the title of the film for the Italian release. Moreover, Stromberg promised to make the screen version “thoroughly acceptable to the Italians and in the [prints] going to Italy, he is willing to delete Mr. Sherwood’s name.”11 Practicing a kind of crosstown shuttle diplomacy, Breen scurried back to the Italian consul with MGM’s counterproposal. Both parties then signed off on the deal.

For Breen and MGM, the pact over Idiot’s Delight was a job well done. “Thanks a million for your customarily prompt and marvelous cooperation … and if you and I are responsible, via this story, for taking a few pokes at gentlemen who profit from battle, we’ll take time out one these days to celebrate,” Stromberg wrote Breen, expressing gratitude for his diplomatic initiatives.12 Having again proven himself Hollywood’s indispensible man, Breen must have glowed.

Despite the amicable outcome, however, the near international incident over Idiot’s Delight was hard to keep secret. “Probably no other subject which has engaged Hollywood attention of late has aroused as much discussion as Robert E. Sherwood’s Idiot’s Delight,” reported Motion Picture Herald, after noting the all-clear signal from the Breen office. “For a time the planned production threatened international complications. However, all matters have been settled.”13 As usual, the belief was that Hollywood had caved to foreign pressure and defanged the bite of the original. “After much international palavering, Idiot’s Delight will be filmed with a few slight alterations, such as a new title, a new locale, and a new story,” smirked Daily Variety. “Outside of that, it will be screened in all its pristine glory.”14

Just as Blockade had to avoid Spanish uniforms, Idiot’s Delight had to erase any vestiges of Italy, including the Italian language. Rather than resort to gibberish for the dialogue of the soldiers, director Clarence Brown and screenwriter Sherwood hit upon a suitably non-nationspecific lingo to avoid ruffling Italian feathers: Esperanto, with the president of the Esperanto League of America serving as technical advisor.15 (As with all dialogue on the American screen in whatever language, the Esperanto was then vetted for vulgarity by the PCA.)

The film that resulted from Sherwood’s play was not as neutered as Variety feared and Italy hoped. Like so many flashbacks from the 1930s, Idiot’s Delight is haunted by the memory of the Great War, opening with a newsreel montage showing battalions of joyous doughboys marching down Broadway under a shower of ticker tape, a proud nation honoring heroes returning from their gallant crusade Over There. By way of contrast, a ragged army of wounded veterans—amputees on crutches and bandaged men on stretchers, the gristle from the slaughterhouse—disembarks from a troopship to make a less glorious entry into civilian life. As Hollywood tells it, the sequence staged in the studio renders the scarred face of the Great War more realistically than the blithe newsreel record.

Among the walking wounded is Harry Van (Clark Gable), a small-time vaudevillian eager to step back into the spotlight. Versatile though he is—hoofer and huckster, at ease dancing in a chorus line or selling patent medicine on a street corner—his showbiz comeback is not smooth. While working with a drunken mind reader on the vaudeville circuit in Omaha, he hooks up for a memorable one-night stand with the saucy Irene (Norma Shearer, Garbo being better cast in Ninotchka [1939]), a gymnast with a Russian accent that may be fake and a line of patter that certainly is. The couple clicks, but the next morning at the train platform, fate takes them in different directions.

A Slavko Vorkapich montage spins the action two decades forward, tracing the ups and downs of the Jazz Age (for Harry Van, mostly down), the crash of the stock market, and the curse of the Great Depression. Too tenacious to fail for long, Harry lands on his feet fronting a chorus line of six frisky blondes (billed as “les Blondes”) on a European tour.

Taking a counterintuitive turn, the effervescent spirit of what seems to be a backstage musical suddenly fizzles. On a train bound to a gig in Geneva, Harry and les Blondes are hauled off at the border, but exactly where and by whom is uncertain. The stranded passengers are ensconced in a grand Alpine hotel, where they will see their fates and backstories intertwine: a young newlywed couple, a raving pacifist, a German scientist, a military man, and a munitions tycoon with a beautiful lady in tow—namely, Irene, the girl from Harry’s past, now in blonde wig, putting on aristocratic airs and refusing to recognize her long-ago lover.

The romantic comedy and musical interludes that follow, including a game Gable stretching his safety zone as a song-and-dance man, are foregrounded against the background of war—literally so, for situated below the hotel is a military airstrip. In rear screen projection, roaring airplanes fill the sky like birds of prey, lifting off for bombing raids that the hotel will suffer in kind. As air-raid sirens screech, Harry and les Blondes divert the guests with a sprightly musical number, the pacifist decries a world gone mad, and the munitions tycoon licks his lips at the prospect of windfall profits.

Sherwood’s play ended in chaos and death, with Harry and Irene, collateral damage, resigned to their doom, crooning “Onward, Christian Soldiers” as the walls of the hotel cave in around them. (“The din is now terrific,” reads Sherwood’s curtain-closing stage instructions. “Demolition—bombs, gas-bombs, airplanes, shrapnel, machine guns.”) Hedging its bets, MGM concocted two endings for the film, one for domestic consumption, one for international release. The international release is apocalyptic, in tune with the play: as Harry and Irene declare their love, the bombs fall, the hotel crumbles, and the couple are casualties of war. MGM previewed the bleak ending and audiences turned thumbs down: no American wanted to see Gable and Shearer blown to bits. The American ending shows the pair in a passionate clinch, resolved to soldier onward—alive.

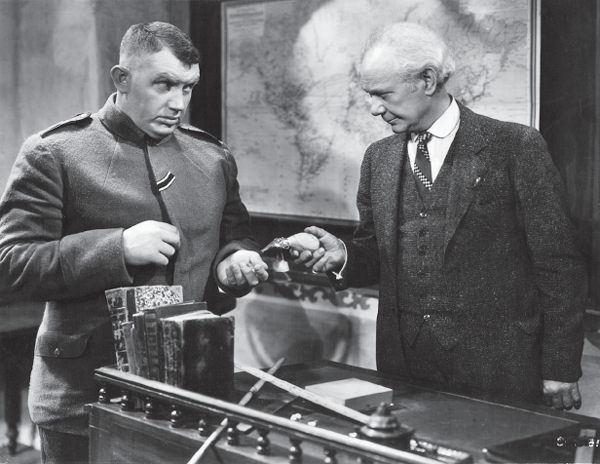

No Italian accents: Clark Gable and Norma Shearer in MGM’s Idiot’s Delight (1939), Clarence Brown’s version of Robert E. Sherwood’s antiwar play.

Idiot’s Delight was a solid hit, but the drawn-out negotiations over Sherwood’s play meant that its release was delayed until January 1939, vitiating whatever edgy topicality it might have had. By then, the Germans not the Italians were the predatory menace hanging over the European continent. Also, with perverse poetic justice, Hollywood had been forced to withdraw totally from the Italian marketplace after Mussolini nationalized film distribution, so all of MGM’s sensitivities to Italian sensitivities were for naught. Besides, the Italians had later decided to preemptively ban Idiot’s Delight, sight unseen, before its release.16

In a postscript to the printed edition of Idiot’s Delight, written a lifetime ago in the spring of 1936, Sherwood surveyed the harrowing war clouds coughed up by the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, the military occupation of the Rhineland by Hitler, and the Japanese incursions into China, and mused, “What will happen before this play reaches print or a New York audience, I do not know. But let me express here the conviction that those who shrug and say ‘War is inevitable,’ are false prophets.”17 Three years later, it was Sherwood’s hopeful prophecy that sounded idiotic.

A sort-of sequel to All Quiet on the Western Front, the film version of which had introduced Hollywood to the ferocity of Nazi film criticism in 1930, Erich Maria Remarque’s The Road Back was published 1931. Like the original, the novel registered the disgust with war in the aftermath of the Great War. It told the story of a shell-shocked squad of German veterans thrust into the political upheavals and economic chaos of postwar Germany. It might be called a veterans’ readjustment story were there a healthy society for the veterans to readjust to.

Although the follow-up did not accrue the sales of All Quiet on the Western Front—almost nothing could have—it earned admiration as a worthy successor to the landmark original. “A book that drops like a plummet in the hearts of men,” rhapsodized the New York Times. “It will be published in twenty-five languages and one must wish that it may be read by every literate man and woman in the world.”18

Universal grabbed up the film rights, but the daunting expense of the project in the midst of the Great Depression—an estimated $400,000 even without the price tag of $150,000 that came with the obvious choice for director, Lewis Milestone—delayed the project for years. Finally, in 1936, with a screenplay by Charles Kenyon, one of the industry’s most reliable script doctors, and British playwright R. C. Sheriff, author of the trench-set deathwatch Journey’s End (1928), Universal moved firmly into production mode. The studio hoped to relive the prestige and profits from All Quiet on the Western Front.19

Unlike 1930, however, Hitler had eyes and ears in Hollywood. Tipped off by the trade press, Dr. Georg Gyssling, the vigilant Nazi consul in Los Angeles, contacted the Breen office to raise objections. “It would beyond all doubts lead to controversies and opposition on the part of the German government, as the story gives an untrue and distorted picture of the German people,” he wrote. Gyssling urged Breen “to use your influence on behalf of correct relations between the American film industry and Germany” and kill the project.20

Having become more than a little sick of Gyssling’s interference, Breen ducked his phone calls and ignored his letters. He also gave Universal a friendly heads up.

At Universal, Charles R. Rogers, executive vice president in charge of production, told Breen “the company was not very much concerned about German protests because it was almost impossible for the company to operate in Germany at the present time, and that any business worthwhile worrying about was not being done in Universal in Germany now.”21

Getting no satisfaction from either Breen or Universal, Gyssling took matters into his own hands and sent out a warning in the form of an epistolary threat to sixty actors signed up to work on the film. To wit:

April 1, 1937

DEUTSCHES CONSULATE

117 West Ninth Street, L.A.

To: (Name of actor)

Universal City, California

Dear Sir:

With reference to the picture, The Road Back, in which you are said to play a part, I have been instructed by my government to issue you a warning, in accordance with Article 15 of the German decree of June 28, 1932 regulating the exhibit of foreign motion picture films.

Copy and translation of this article are enclosed herewith.

You will note that the allocation of permits may be refused for films with which persons are connected who have already participated in the production of pictures detrimental to German prestige in tendency or effect in spite of the warning issued by the competent German authorities.

Truly yours,

(signed) Georg Gyssling

Consul

Gyssling had pulled the same stunt the year before with his threatening letter to Isobel Steele, screenwriter-star of I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany (1936). However, I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany was an obscure knockoff from an independent producer. The Road Back was a prestige literary adaptation from a major studio. Moreover, Gyssling’s letter had been sent to the entire cast of The Road Back, which guaranteed that shock waves would reverberate throughout Hollywood’s talent pool.

Reproduced first in the Hollywood trade press and the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League’s News of the World, and then in newspapers around the country, Gyssling’s letter ignited a furious backlash. Targeting sixty individual actors on stationery embossed with the Nazi eagle was a far more provocative act than applying behind-the-scenes pressure to a no-name independent production. The consul’s threat, said the Hollywood Reporter, had “aroused American film interests to a high state of resentment against Nazi policies.”22 Actually, not just film interests were aroused. “This isn’t a Nazi country, and there’s no reason to adopt Nazi standards,” huffed the New York World-Telegram.23 The Nazis might bark streng verboten at American film people in Berlin, but not in Hollywood—at least not any longer.

At Motion Picture Daily, editor Red Kahn, the most reliably anti-Nazi of the trade reporters, hit back hard at Gyssling and his government. Given that “no yardstick can adequately measure the psychopathic vagaries of the Nazi mentality,” Kahn wondered “just where is this to end if a crackpot and irrational government, riding the seat of power though ruthlessness and oppression, is to be permitted to waive international and diplomatic courtesy by its unwarranted interference in matters which are none of its business?” Kahn gave credit for the pushback where it was due. “While Universal determined to do the ostrich stunt and preferred a hush-hush policy, certain Hollywood organizations with liberality sprinkled though their backbones, did not.”24

Of course, the unnamed organization with the stiff backbone was the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, which, characteristically, had taken point position in the counterattack. Trying hard to conceal its delight beneath its high dudgeon, HANL labeled Gyssling’s letter “one of the most insidious examples of Nazi interference in the lives of American citizens.” It also sent a telegram to Secretary of State Cordell Hull condemning Gyssling’s intimidation tactics and demanding the consul be deported. “This action constituting an infringement on American diplomatic hospitality, we request that you take immediate action toward the removal of the consul and prevention of future occurrences.”25

Goaded into action, the normally quiescent State Department responded with a formal protest to the German foreign office. It got immediate results: the Nazis backed off. “The German ambassador has instructed the German consul at Los Angeles to refrain from issuing further warnings to American citizens in connection with the production of plays,” the State Department informed HANL.26 Hans-Heinrich Dieckhoff the new Nazi ambassador in Washington, sweetened the diplomatic victory by issuing a formal apology. He promised that Gyssling’s strong-arm tactics would not be repeated. The consul, he said, was merely following orders from former ambassador Hans Luther, who was himself acting on instructions from the Reich Ministry—which Reich Ministry, Dieckhoff did not say.

In truth, Gyssling seems to have been caught in the labyrinthine and sometimes lethal web of Nazi bureaucracy, pinned between Goebbels’ Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, the supreme arbiter of all Nazi media matters, and Baron Konstantin von Neurath’s Foreign Ministry, nominally in charge of foreign affairs. “I did just what I was advised to do in an order originating in Berlin,” Gyssling asserted, denying reports of a rebuke as “just fiction and fabrications not based on any facts.”27

The threatening letters from the German consul also got Breen’s Irish up: it was he not the Nazi who laid down the law in Hollywood. While Gyssling flailed, Breen gave Harry Zehner, Universal’s liaison with the PCA, the welcome news that “we take pleasure in enclosing Production Code certificate of Approval No. 3137” to The Road Back.28 In a report to Will Hays, he emphasized his personal stamp of approval on the project. “The Road Back is an excellent picture. A follow up to All Quiet on the Western Front.”29

As the controversy swirled, production went into high gear. Envisioning another All Quiet on the Western Front, and hoping to tap into antiwar sentiment aroused by the turmoil in Europe, Universal spent lavishly but not carelessly on its second Remarque project. Director Lewis Milestone having priced himself out of the running, the studio entrusted the project to its mad doctor of the horror genre, James Whale, the florid director of Frankenstein (1932) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), and himself a traumatized survivor of the Great War. Whale ordered three acres of trenches dug on a huge outdoor location and commissioned a 50 by 250–foot matte background, the largest yet built, to simulate the bombed-out moonscapes of no-man’s-land. A 120-man technical crew wrangled lights and rigged explosives.30

Even with Gyssling muzzled, however, controversy continued to dog the project. Soon after Universal announced completion of the film, Daily Variety published a sensational report (“by cable from London”) alleging that the print of The Road Back slated for release in Germany had been edited to Nazi specifications. J. Cheever Cowdin, chairman of the Universal board, and Gus Schaeffer, the studio’s foreign head, were reported to have returned to London from Germany, after a private consultation with Joseph Goebbels. “Following the talk, Goebbels agreed to [a] license [permitting] showing of The Road Back on condition that Universal change the ending to glorify Hitler, which it is understood will be done,” said the report.

From New York, Universal president R. H. Cochrane angrily denied the meeting with Goebbels or any editing done under the Nazi gun. “A complete falsehood from start to finish,” he fumed. “Nothing but malice could have created it.” In a cablegram from Europe, Cowdon was equally adamant. “Neither Schaeffer nor I ever met Dr. Goebbels in the first place, and in the second place we have never discussed The Road Back with any official in Germany at any time.” Cochrane elaborated: “The simple truth is that after showing the picture to the public we decided to add several romantic scenes. Those who have seen both versions say the new one is immeasurably better. Politics and fear had nothing to do with it.”31 Cochrane blamed the report on a disgruntled former employee who had been fired.32

Remarque's authorship notwithstanding, Gyssling and the Nazis had little to fear from The Road Back. Where All Quiet on the Western Front was elegiac and epic, The Road Back was toothless and tired. Even so, the Nazis were unhappy with the final cut. For the gala screening held in Washington, D.C., on July 22, 1937, Universal’s publicity department (in an obvious setup) sent out special invitations to German ambassador Dieckhoff and his staff. “Members of the goose-stepping embassy staff stayed away in droves,” grinned Variety, with nary “a single Nazi in the house.”33

The film the Nazi diplomatic corps shunned opens in the early morning hours of Armistice Day. For a squad of mud-caked, war-weary German soldiers, life in the trenches is grubby and vulgar, full of spit, sweat, grime, bad food, and fear. After years of grueling combat, the men are at the end of their ropes. “It’s gotta stop!” wails a psychic wreck. It doesn’t, at least not quite then. In the only battle scene in the film, a long tracking shot follows the men over the top, through the concertina wires of no-man’s-land, into the mouth of hell.

When news of the Armistice arrives, a montage sequence shows Germans, French, British, and Americans alike celebrating the end of hostilities. To punctuate the utter insanity of war, when the Germans first encounter their former enemy in the persons of a company of fresh-faced, well-provisioned Americans, the first gesture of the Yanks is to offer the Germans cigarettes and chewing gum. “What’s the use of fighting decent fellahs like that?” asks a German soldier. “Darn fools we were.” Adds a comrade: “And so were they.”

Mustered out, the troops enter a politically volatile Germany that has not yet seen the rise of the Nazis, but is certainly being roiled by a group of violent subversives Hollywood is not afraid to indict. “Are you comrades or not?” demands a homefront rabble rouser, marking his band of street thugs not as nascent brownshirts but as communist agitators. Still, the real danger to the well-being of the veterans is the backfire from the past, the psychic meltdown of shell-shocked troops in the grip of what today would be called post-traumatic stress disorder. Warped by four years of killing, the boys are unfit for reentry into civilian life. They wander the streets at night, seeking out each other’s company, unable to connect with family, friends, or fiancées. “I must find myself and no one can help me,” a shattered survivor tells his girlfriend. Those who did not die on the battlefield have died inside. One crazed veteran is confined in an insane asylum; another, enraged that his unfaithful girlfriend has taken up with a bloated civilian, shoots the man in cold blood. At his trial, the defense pleads mitigating circumstances. “You can’t wash four years of killing off the brain with one word—peace!”

In the film’s final movement, a newsreel montage tracks the postwar denouement: all the former belligerents are feverishly rearming, all equally culpable, all preparing for a sequel, heedless of the lessons of All Quiet on the Western Front and The Road Back.

Artistically and commercially, The Road Back was no All Quiet on the Western Front. Critics strained to find something good to say about the well-meaning, self-serious drama, but they could not deny the tepid response from the crowds. “There is much that is deep and beautiful in The Road Back, especially at the present time when banner headlines daily promise the outbreak of another war in Europe in the not too distant future,” allowed Motion Picture Herald, impressed with Universal’s good intentions but little else.b Attending a matinee at the Globe Theater in New York during its opening week, the reviewer was duty bound to deliver the bad news. “The theater was approximately half filled and the audience was predominantly men, all of whom sat silently as the film unwound, apparently unimpressed at those scenes intended as comic relief, and remained silent as they filed out upon the picture’s completion.”34

Weimar set melodrama I: confronting a clueless home front, a combat veteran (Andy Devine) is forced to surrender his water pistol to his former high school instructor (Al Sheen) in The Road Back (1937), James Whale’s version of the novel by Erich Maria Remarque.

Another big-screen version of a well-regarded Remarque novel caused far less of a stir, perhaps because its concern with the backfire from the Great War was subordinate to its wallowing in the passions from a romantic triangle, or quadrangle. Written in 1936, by which time Remarque was in exile, and published in English in 1937, Three Comrades was another psycho-political drama of the residue from the Great War, but the addition of a beautiful girl into the mix put the Hollywood rendering on firmer footing. While the novel was still in galleys, MGM won a fierce bidding war for the film rights only to have second thoughts as it monitored the decline of Universal’s The Road Back. “Three Comrades has political production problems fully as critical, from the showman’s angle, as had The Road Back,” observed Daily Variety, by which it meant that overt political reverberations were as problematic for American audiences as for German diplomats.35 Even so, chastened by his reprimand over The Road Back, Gyssling kept mum about the Hollywood version of the subsequent Remarque novel.

Directed by Frank Borzage, Three Comrades (1938) is a gauzy period piece, set in Germany after the Armistice but before the uprising of the Nazi Party in Munich in 1923. Like so many interwar flashbacks, it opens precisely on November 11, 1918, Armistice Day, the date scrawled in vapor trails in a skyline establishing shot. In a smoky rathskeller, weary but blissful survivors are toasting the end of the war, raising their glasses to fallen comrades on all sides. The three titular friends—big brotherly Otto (Franchot Tone), idealistic firebrand Gottfried (Robert Young), and strong silent type Erich (matinee idol Robert Taylor) pledge lifelong fidelity on the strength of a bond forged in the crucible of combat. Expert airplane mechanics, they retool for civilian life by opening an automobile repair shop to eke out a living in an economically crippled, spiritually traumatized nation.

One day, taking their beloved souped-up convertible “Baby” out for a cruise in the countryside, a horn-blowing road hog tries to outrace them. The speed demons easily beat out the overweight, arrogant businessman behind the wheel, but his fetching passenger Patricia (a radiant Margaret Sullavan) stops them cold. Defying expectations, the entry of the girl does not break up the male triad, but solidifies it: Otto and Gottfried guide the romantically maladroit Erich through his courtship and protectively embrace Patricia as a sister. Throughout, the usual Code-mandated obscurity falls over the Remarque clarity: Gottfried is an idealist (read: communist) while Patricia’s friend (read: sugar daddy) is a Nazi-in-waiting.

In the background of the romantic harmony, the social wreckage of postwar Germany creates a powder keg just waiting for someone to strike the match. Wounded veterans mark time in cafes, roving bands of angry men prowl the streets, and the precious “Baby” is vandalized by thugs. While trying to save his elderly mentor from a howling mob, Gottfried is shot in the back. Patricia—by now an embodiment of all that was best in bygone Germany—succumbs to that most romantic of terminal illnesses, tuberculosis. In the final image, as fighting again breaks out in their city, Otto and Erich leave Germany for a new life in South America, accompanied by the ectoplasmic forms of Gottfried and Patricia.

Three Comrades was hardly didactic and barely historical, but even three-hankie hokum, if set in Germany, could spark a minor controversy. In reviewing the film, Time charged that the PCA had compelled the deletion of many anti-Nazi scenes written into the original script by F. Scott Fitzgerald and Edward E. Paramore Jr.—specifically, a scene in which “a poor Jew proclaimed his love for Germany; another in which a rich Jew refrained from cheating three young gentiles; [and] “a scene in which famed books, including Remarque’s, were burned by the Nazis.” All, claimed Time, were deleted.36

Weimar set melodrama II: Robert Young, Robert Taylor, Margaret Sullavan, and Franchot Tone form a star-crossed romantic quadrangle in MGM’s Three Comrades (1938), Frank Borzage’s version of the novel by Erich Maria Remarque.

Producer Joseph L. Mankiewicz denied the charges: he admitted that the original script contained politically charged material, but pointed out that the 1920–21 setting was prior to the Nazi ascendancy. With the film running long, the studio decided on its own “to delete all sequences which were extraneous to the love story of the film,” said Mankiewicz. Neither Breen nor Gyssling played any part in the decisions.37 Given the primacy of boy-girl stuff in Hollywood melodrama, Mankiewicz offered an all too credible explanation.

A vitriolic review in Variety, a rare occurrence for a handsomely mounted A picture from a major studio, had little patience with Hollywood’s pat defense: the primacy of entertainment over all else. “There must have been some reason for making this picture, but it isn’t in the cause of entertainment,” complained John C. Flinn, the paper’s high-profile critic. “It provides a dull interlude, and despite all the draught of the star names, it’s in for a sharp nosedive at the box office.” Flinn argued that time traveling back to the Germany of yore was jarring and off-putting from the jittery perspective of 1938. “In the light of events of the past five years, the background of 1921 in Germany seems like a century ago,” Flinn continued. “There is developed in the film no relation between the historical events of that period and the Reich of today. The story is dated and lacks showmanship values of current European movements.”38 Of course, any Hollywood filmmaker who tried to inject the “showmanship values” of “current European movements” into a feature film was impeded by the Breen office and razzed by the reporters at Variety. Just ask Walter Wanger.

For all their compromises, however, both The Road Back and Three Comrades kept faith with the most important of the anti-Nazi blasphemies in the source novels: the Germans were not stabbed in the back but, like the other combatants, had cut their own throats. Even so, the author looked askance at the Hollywood rewrites. After viewing Universal’s version of The Road Back, he could only mutter, “Well, in any case, it’s scarcely Remarquable.”39

In 1938, Martin Dies Jr. was a four-term term Texas Congressman, a Democrat, a disenchanted New Dealer, and man on a mission. In the eyes of Martin Dies, two fifth columns from opposite ends of the ideological spectrum were conspiring to subvert the United States of America. One raised its right arm to Hitler and Nazi Germany under the banner of the German American Bund and the Silver Shirts; the other looked to Stalin and the USSR and plotted sedition at meetings of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Both needed to be investigated, exposed, and rooted out of the body politic.

Unlike Joseph McCarthy, a surname forever spat out like a curse, Dies has been largely forgotten to history, but the name of the committee he founded became a permanent part of the lexicon of American culture, the House Committee on Un-American Activities, abbreviated for purposes of pronunciation as HUAC.

Established by Congress in June 1938, HUAC—then called the House Committee for the Investigation of Un-American Activities—was tasked with probing “the extent, character, and objects of un-American propaganda activities” and “all other questions in relation thereto that would aid Congress in any necessary remedial legislation.” Dies was appointed chair, and, armed with subpoena power and a squad of G-men, set about implementing his broad mandate. To preempt criticism, he affirmed a commitment to public hearings—his would be no “star chamber proceedings”—and a tightly focused investigation. “This is not going to be any ‘shooting in the dark’ inquiry,” he promised. However, speaking on NBC radio, he left no doubt about who was in his crosshairs. “I cannot understand why the Nazis in the United States do not move to Germany, the Communists, to Russia, and the Fascists, to Italy. The fact that they believe in communism, fascism, or Nazism demonstrates conclusively they do not believe in Americanism.”40

In point of fact, both the German American Bund and the CPUSA were engaged in deeply un-American activities. The original charge of what quickly became known as the Dies Committee was neither outlandish nor xenophobic. Under the leadership of Fritz Kuhn, a former German machine gunner in the Great War, the German American Bund operated a nationwide network of brownshirt-like paramilitarists who spouted antisemitic venom and agitated for an American Reich. The Bund fit the operative definition of a fifth column, no different, if less brazen and effective, than the Sudeten Deutsch Party that was at that very moment lacerating Czechoslovakia from the inside.

American communists were less enamored of uniforms and regalia, but no less dedicated and far more successful in gaining proximity to the center of American political life. After 1935, under the umbrella of the Popular Front, international communism softened its dogmatic rhetoric and penchant for separatist purity to foster a broader alliance against Nazism. No longer soldiers of an alien ideology emanating from a foreign capital, American communists stressed the native roots of the future revolution. Straining to link the Bolsheviks and the Founding Fathers, Earl Browder, the head of the CPUSA, dreamed up a slick advertising slogan for the brand: “Communism is 20th century Americanism.”

Of course, the true mecca for the CPUSA was Moscow not Philadelphia. The pages of the Daily Worker, the official newspaper of the American party, and statements by the membership bowed before the cradle of the Marxist revolution, a mythic promised land that more than one member of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League called Mother Russia. “America rose up and revolted against the tyranny of Old England,” declared the actor Melvyn Douglas, very much on message. “The Russian people ended the hundred-year-old tyranny of Czarism.”41

Even before the Dies Committee hearings, accusations of communist infiltration, often laced with antisemitism, had permeated criticisms of Hollywood. For nativist bigots, the Jewish landlords in the Sodom on the Pacific doubled as agents in a forward operating base for Moscow. Major Frank Pease, a former Hollywood agent, made a second career out of redbaiting and Jew-hating, firing off slanderous telegrams to Hollywood producers and railing against “the Bolshevik temple” built in Hollywood, a phrase that neatly conjoined the alien ideology and non-Christian religion.42 As prominent actors, screenwriters, and directors moved into the ranks of the Popular Front, their ideological opponents tracked the migration leftward and spouted invective. The Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, the Motion Picture Artists Committee, and kindred celebrity-laden groups found that the magnetic pole that was Hollywood had a minus as well as a plus: the stars attracted attention to the Popular Front cause but attacks on the stars also attracted attention to the attackers. A congressman who went after MGM or Warner Bros. got bigger headlines than a congressman who went after the Farm Security Administration or the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Shortly after its founding in 1936, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League felt obliged to respond to the accusations. “The League is … not surprised that charges of Communist have been directed against it … nor is it concerned,” declared an editorial in the Anti-Nazi News. “We would however regret it if some of our friends and well wishers were to fall into this old Nazi trap. Frightened by the Communist bugbear some of them have rushed to us with the sincerest and best intentions suggesting that we make the league anti-communist as well as anti-Nazi.” But HANL refused to be distracted from its core mission, vowing in capital letters: “THIS LEAGUE IS DEDICATED UNALTERERABLY AND EXCLUSIVELY TO FIGHT NAZISM AND NOTHING WILL DIVERT IT FROM THAT ONE AIM.” It then affirmed what was patently false: “Not one member of the executive committee is a member of the Communist party.”43

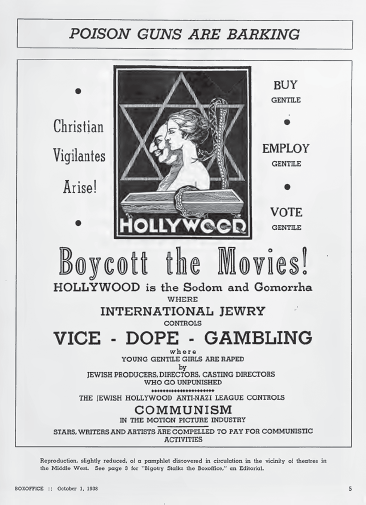

From Berlin to Hollywood: the notorious leaflet dropped from the Garland Building in Los Angeles, September 1938).

The whispered love affair between Moscow and Hollywood was amplified dramatically when, beginning on August 12, 1938, Dies brought his gavel down on a series of public hearings that stretched through the dog days of summer. The investigation cast a wide net—over communism and Nazism, labor unions and theater groups, New Deal agencies and paramilitary outfits. The tumultuous political activity of the 1930s provided the committee with plenty of headline-grabbing material. As usual, however, the glamorous workers on the studio soundstages garnered more copy than the prosaic laborers on the shop floors.

“Radical and communist activities are rampant among the studios of Hollywood”: Martin Dies Jr. (D-TX), first chairman and founding member of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, with his son Bobby, rings down the gavel on hearings in Washington, D.C., August 13, 1938.

The first day of hearings focused on the German American Bund and the revelations of the brothers John and James Metcalfe, who had infiltrated the group and uncovered a “vast spy network” augmented by a “powerful sabotage machine.” The brothers revealed that Fritz Kuhn boasted of his pull with Adolf Hitler, whom he claimed was grooming him as the führer in a future American Reich.

On the communist side, the less disciplined cadres of the Federal Theatre Project offered a tantalizing target. Basically a make-work project for playwrights, directors, and actors willing to stage shows in line with New Deal policies, the FTP favored playbills that smacked of party-line inspiration featuring cast members who subverted American values more sacred than capitalism. The committee heard disturbing testimony about “white girls dancing with colored men” at cast parties and, in one instance, a black man asking a white singer out on a date.

Yet Hollywood, with bigger names and pocketbooks, was the inevitable destination. On August 14, committee investigator Edward F. Sullivan fired the first broadside at the motion picture industry. Though Sullivan devoted most of his testimony to non-Hollywood subversion, notably the activism of firebrand labor organizer Harry Bridges, West Coast leader of the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), the Hollywood angle siphoned off most of the press ink. “Evidence tends to show that all phases of radical and communist activities are rampant among the studios of Hollywood and, although well known, is a matter which the movie moguls desire to keep from the public,” he testified. “A number of film celebrities are using their large salaries to finance communistic activities including groups which were conducting agitation campaigns in agricultural regions in California. I might say in passing that a very large number of motion picture stars are strongly opposed to all this subversive activity but, as one very prominent star told me, if he spoke out loud about the situation, he would soon be ditched by the studios and a campaign of vilification would be started against him.”

Sullivan did not accuse either the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League or the Motion Picture Artists Committee by name but HANL president Donald Ogden Stewart was happy to pick up the gauntlet. “It is ominous that the Dies investigating committee has adopted the practice of making accusations without revealing facts to substantiate them,” he declared in a written statement. “When Hitler is mobilizing a million men at the Czechoslovakian borders, when another investigator of the Dies committee finds that the National Guard is being invaded by the Nazi Bund, and there is an effective German spy ring throughout the country, these charges leveled at an organization devoted to the task of combating Nazism are in themselves a threat to democracy.”44 An indignant statement from MPAC also rejected the “irresponsible attacks” and cheekily demanded “an investigation of the investigation.”45 Hollywood Now went over the Sullivan report line by line and concluded: “On the basis of Sullivan’s own report, he brands himself as a liar, an anti-Semite, a red-baiter, and a pro-Nazi who is trying to divert attention from Nazi activities by smearing the organizations that fight Nazism.”46

Seeing the Dies Committee hearings as a danger to all of Hollywood and not just to its leftmost flank, mainstream voices in the industry also spoke out against Dies and company. “Who is this fellow Sullivan who made such a wild bellow in front of the Dies committee the other day in Washington?” demanded Billy Wilkerson from his forum in the Hollywood Reporter.47 Director Willard S. Van Dyke, president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and vice president of the Screen Directors’ Guild, called Sullivan “a very common liar” for tarring Hollywood as a “hotbed of communism.” MGM producer John W. Considine sardonically welcomed a complete investigation of the backlots by the Dies Committee so that “the world will realize that we are busy making motion pictures here—we haven’t time to act any ‘ism’—Nazi, Fascist, or Red.”48 Speaking of isms, the Dies Committee hearings inspired Dorothy Parker to utter one of her most quotable bon mots: “The only ism Hollywood is interested in is plagiarism.”

Yet as Dies rode to prominence on Hollywood’s back, the official voice of the motion picture industry—the MPPDA—was conspicuously silent. Outraged that the MPPDA was leaving it to HANL to defend the integrity of the industry, Billy Wilkerson asked, “Why should an investigating committee sent out from Washington with preconceived notions brand the industry as COMMUNISTIC without having one or a group of creators answering for the industry’s protection?”49

The answer, besides the fact that wilting at the first sight of political heat was the MPPDA’s default mode, was that the association had far more serious Washington-bred problems to deal with than the Dies Committee. Earlier, on July 20, 1938, the Department of Justice had filed a civil suit in New York against the eight major Hollywood studios, charging the industry with monopolistic practices in restraint of trade and seeking to sever the ties between production and exhibition—a stake into the heart of the vertically integrated business. At the same time, in the U.S. Senate, Matthew M. Neely (D-WV) was proposing legislation to ban “block booking,” a venerable industry practice in which exhibitors were forced to buy a whole slate of films from a studio, often sight unseen, in order to obtain the top attractions. The Dies Committee hearings were held when both the executive and legislative branches of FDR’s New Deal threatened, as an alarmed notice in the Hollywood Reporter warned, to “police the industry from camera to projector.”50 Dies might tar Hollywood’s image, but the rest of the New Deal seemed poised to deliver a lethal body blow.

At this juncture, the Dies Committee committed an unforced error that changed the game. On August 22, 1938, Dr. James B. Matthews, a former communist organizer now working for the other side, testified that “the Communist party relied heavily on the carelessness or indifference of thousands of prominent citizens in lending their names for its propaganda purposes.” In the long-range plans fomented from Moscow, stars were well-meaning dupes with open checkbooks and photogenic faces. “For example, the French newspaper Ce Soir, which is owned outright by the communist party, recently featured hearty greetings from Clark Gable, Robert Taylor, James Cagney, and even Shirley Temple.” That last name was the gaffe that launched a thousand quips. Matthews hastened to add that he was not accusing the named stars (“No one I hope, is going to claim that any one of these persons in particular is a Communist.”), but his disclaimer was lost in the delicious incongruity of the carrot-topped moppet doubling as a red agent for Stalin.

The Dies Committee was drenched in a flood of ridicule. “About everybody in Hollywood except Mickey Mouse, Charlie McCarthy, and Snow White has been signed up for [the] sake of names in some Communist front organization,” crowed Variety.51 Picket lines of communist women dressed in short skirts and licking lollypops carried placards reading “Tut! tut! Mr. Dies. Shirley Temple Is Not Subversive.” Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins chided the congressman for “the preposterous revelations of your committee in regard to this innocent and likable child.”52 Editorial cartoonists, columnists, and radio wisecrackers relished the image of the subpoenaed tyke being hauled before the Dies Committee for a grilling by the cigar-chomping chairman. Even the conservatives at Motion Picture Herald found the notion of America’s ten-year-old sweetheart being a Comintern mouthpiece a bit much. “Little Shirley Temple has been ‘boring from within’ for the Communists, helping the Moscow reds take over the country?” it asked incredulously. “Little Shirley—whose reputation heretofore has been boring from without?”

Humiliated and infuriated, Dies went on radio to set the record straight, angrily comparing Matthews’ actual testimony to the press accounts, but no amount of damage control could beat back the derision. “Without question, the Shirley Temple incident was the most reprehensible of the period,” recalled Dies years later, still steaming. “The treatment can only be explained as ignorance or deliberate falsehood; those who wrote that Dr. Matthews had called Shirley Temple a Communist left no alterative.”53

Riding the momentum, HANL announced a rally and issued a challenge:

Because the Dies committee has abandoned its sworn purpose of investigating subversive activity we intend to carry on the fight by holding a mass meeting August 24 in the Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles and we are challenging the Dies committee to present substantiation of these so-called charges at this public meeting so that they may be answered openly and democratically. Failure to meet our challenge can only be interpreted as a misuse by the Dies committee of public funds to aid reactionary Fascist interests, contrary to the law.54

Dies, Sullivan, and Matthews never showed up, but some 3,000 Hollywood anti-Nazis packed the auditorium to demand the abolition of the Dies Committee. It was a convivial and rowdy affair, punctuated by laughter, jeers, and sing-alongs. “Fellow subversive elements,” began Assemblyman Jack Tenney, president of the musician’s union, “I have just heard that Mickey Mouse is conspiring with Shirley Temple to overthrow the government and that there is a witness who has seen the ‘Red’ card of Donald Duck.” Donald Ogden Stewart took the stage to banter and bait. “Folks, I didn’t mean to be a Red,” he mock-apologized. “I want to tell you how it all happened. Three years ago I was just a good screenwriter—at least I had a three-car garage and a tennis court. Dorothy Parker asked me to join the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. Then I learned a lot of things about Nazism.” Whether carried away by anger at the Dies Committee or the rush of his own rhetoric, Ogden then outed himself ideologically:

I learned that Nazism had to do with civil liberties and the suppression of labor’s rights. The Communist position began to eat into my soul. I found myself questioning editorials in the Times. So here I stand before you tonight—one of those things.

The musical portion of the evening was provided by Ray Mayer, Jack Albertson, and Billy Griffith, who sang a number from the MPAC show Sticks and Stones, “It Can Happen Over There, But It Can’t Happen Here,” accompanied by John Green, pianist and composer. The crowd called the quartet back for four encores.55

Yet for all the laughter and ridicule heaped upon the Dies Committee, the hearings had done their work. Tarred from the halls of Congress as a launching pad for communist subversion, Hollywood was ever more suspect as a Jewish citadel up to no good. Blaming any spike in antisemitism on the excesses of the New Deal, Dies tried to distance himself from the bigots. On the streets of Los Angeles, however, the antisemitism kicked up by the hearings was literally blown into the faces of pedestrians.

In September 1938, a pro-Nazi fanatic scattered antisemitic leaflets from the top of the Garland Building in downtown Los Angeles. Illustrated with the slick graphics of Reich Ministry propaganda (a hooknosed Jew, a Star of David, and a serpent entwining an Aryan female), the leaflets boldfaced the usual slurs. “Hollywood is the Sodom and Gomorrha where International Jewry Controls Vice-Dope-Gambling,” read the copy. “Where Young Gentile Girls are Raped by Jewish Producers, Directors, Casting Directors.” The very skies of Los Angeles were now spewing antisemitic venom.

Red Kahn, who had left his perch at Motion Picture Daily to edit the glossy trade weekly Box Office, devoted several articles and editorials to the incident. Big names from throughout the industry bombarded Box Office with telegrams condemning the rain of Nazi propaganda on the streets of Los Angeles. Pete Harrison suggested that “the vicious propaganda” should be counterattacked from the motion picture screen. “There should be produced a single reel with some of the most prominent moving picture stars delivering a speech to picture audiences, assuring the American people that there is no communism in Hollywood.”56 Yet the fact that the leaflets warranted a refutation was a confirmation of how thickly the air had become permeated with their contents.

On October 3, 1938, NBC gave Donald Ogden Stewart free airtime to respond to the Dies Committee. At 9 p.m., from KECA in Los Angeles, speaking over a nationwide radio hookup in his role as chairman of HANL, Stewart lambasted Dies in what the Hollywood Tribune described as “a stinging coast-to-coast broadcast revealing the falsity of the unspeakable accusations against a small group of Americans who are lawfully opposing the obscene doctrines of Hitlerism. His address was a vigorous and forthright attack against the sworn enemies of democracy.”57

Nonetheless, in the wake of the Dies Committee hearings, some prominent moguls took pains to distance themselves from HANL. “We’ve got Communists in Hollywood drawing down $2500 a week,” claimed MGM chieftain Louis B. Mayer. “Some of them are great writers, who are demanding ‘free expression’ in their work for pictures. The industry knows who they are and knows too that they are financed and supported by the Third Internationale.c The industry has fought them in the past and stopped them from spreading their pernicious propaganda through motion pictures, which are the greatest molder of public opinion that ever existed.”58 Twentieth Century-Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck asserted that of the 30,000–40,000 workers in the motion picture industry, only a few were rotten apples who gave the rest a bad name. “I do not deny that a few in Hollywood get out the pink shirt now and then. They promptly get splattered over the nation’s front pages, and Hollywood is branded communistic,” said a frustrated Zanuck. “But actually these people are in an infinitesimal minority. They no more represent the industry than does one drop of water represent a lake.”59

After finishing the hearings in September the Dies Committee threatened to take its investigation to the scene of the crime—Hollywood—but a lack of funds forestalled the road show.60 However, it soon revived to prove one of Congress’s longest running acts. Throughout 1939 and 1940, despite fierce opposition from the Roosevelt administration, the Dies Committee continued its campaign against un-American activities, left and right, with Hollywood never far from its sights. Chairman Dies kept up the drumbeat in articles for Liberty magazine, with scarifying titles like “The Reds in Hollywood” and “Is Communism Invading the Movies?”

But by then it was Washington not Hollywood that was out of synch with the public mood. As war roiled and then erupted in Europe, subsequent congressional investigations, in either the House or the Senate, inspired more defiance than dread from the investigated. “The Dies witch hunt is on again,” sneered HANL in 1939, unleashing a metaphor from 1692 that would prove repeatedly serviceable. “It is the same old witch hunt of last year, decked out with a new name and a new ‘menace’ to attract new attention. This time the quarry is ‘pressure groups anxious to get America embroiled in Old World feuds and quarrels,’ according to a Dies statement to the press while in Los Angeles.”61 The next year, Variety suggested that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences should grant Dies a special Oscar for his performance. The classification would read: “For Best Original Melodrama by a Non-Professional.”62