Once a featured attraction, the March of Time (1935–1951) is remembered today, if remembered at all, as the template for the first mockumentary in American film history, the sly send-up that jump-starts Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) scant seconds after the title character gasps his last word. A faux précis of the life of the fictional media baron Charles Foster Kane, the mini-biopic cops a style once instantly recognizable, now a joke lost on the unhip. Truth to tell, a member of the first-run audience who sauntered in a few minutes late might have taken the phony for the original. The fake archival footage doctored to type (Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland stomped on the raw film stock to mar the celluloid with the scratches and glitches that betoken age), the stentorian bombast of a narrator addressing mere mortals from the clouds of Mount Olympus (voiced by Mercury Player William Allard doing a pitch-perfect imitation of Westbrook Van Voorhis, the March of Time’s pompous orator), and the circuitous ass-backwards syntax of Time magazine-speak (“For forty years appeared in Kane newsprint …”) created a note-for-note counterfeit of awesome mimesis. “News—on the March!” blares the voice-over in basso profoundo, echoing the signature sign-off of the original: “Time—marches on!”

Debuting on February 1, 1935, distributed monthly by RKO to some 11,000 theaters worldwide, the March of Time newsreel, as it was often mislabeled, presented a ripe target for parody: stuffed with its own importance, strutting its print-based lineage, and lording its superior intelligence over the comedy shorts and travelogues it bid to supplant on the motion picture program. Modesty never became the house of publisher Henry R. Luce, the nonfictional media baron who launched an authentic revolution in screen journalism when he adapted Time magazine and the March of Time radio series for the motion picture theater.1 One reason was in the title: time. The other was in the journalistic ethos: the March of Time embraced the controversial news of the day that the newsreels shunned.

The twice-weekly issues of the five commercial newsreels clocked in at ten minutes or so, barely enough running time for a moviegoer to read the intertitles as a dizzying cascade of images flashed by in rapid-fire review, a smorgasbord of political headlines, photogenic disasters, royal pageantry, glamorous celebrities, adorable critters, sports highlights, fashion tips, and amateur performers with dubious musical talents. On occasion, when the inherent drama or eye-popping spectacle warranted, the newsreel companies expanded from one to two reels with the release of a longer-form “special issue” devoted exclusively to a single momentous event—the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, the kidnapper and murderer of the Lindbergh baby; the explosion of the zeppelin Hindenburg; or the Japanese attack on the American warship Panay on the Yangtze River—but the release patterns were as unpredictable as the breaking news stories. For in-depth coverage and intelligent commentary, the well-informed citizen read a good newspaper, listened to the radio, or pored over the weekly articles in Time, Liberty, and Newsweek.

In contrast to the drive-by shooting of the newsreels, the March of Time took things slow and steady, trading on the aura of gravitas inherited from the parent company. Not being up against a twice-a-week deadline, the editors enjoyed the luxury of time—time for background, context, and rumination. They sifted through archival footage (“library stock” in the jargon of the day) and exploited the still novel mnemonic kick of film footage seen long ago and now replayed to jog the cinematic memory of the moviegoer. In the mid-1930s, the record of the past preserved on newsreel film would fill only a small warehouse—maybe a garage—but the March of Time was a pioneering custodian and re-presenter of the past as captured by the motion picture camera.

When library stock or current footage was unavailable, staged reenactments of passable verisimilitude filled in the narrative gaps, sometimes with paid actors, often with the real-life personalities only too flattered to play their part on screen. Intercut with the library stock, the reenacted vignettes may or may not have been mistaken for the real thing by unsophisticated viewers, but sharp-eyed trade critics noted the reenactments and purists lambasted the playacting.

Hectoring though its Voice of God narration was, off-putting though its puffed-up self-regard might be, the March of Time was as responsible as any film title for the First Amendment protections ultimately granted screen journalism. In 1937 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences expressed its appreciation for the luster the series lent the medium with the award of a special Oscar “for its significance to motion pictures and for having revolutionized one of the most important branches of the industry—the newsreel.” The next year, the National Archives in Washington, D.C., hailed the March of Time as the “best medium for transmitting a record of contemporary life to future generations” and established a special archive to preserve the reels.2

Never modest about its own accomplishments, the Luce empire touted the difference its motion picture branch made to screen journalism. In 1936, to celebrate the first anniversary of its cinematic offspring, the editors of Time published a slick folio and publicity sheet entitled “Four Hours a Year.” Gazing down from on high, the Time machine indicted the craven newsreels. “The most stultifying self-imposed censorship ever known to journalism blanketed the existing output” of the newsreel, especially regarding its shameful blacking out of the face of Nazism. “For nearly a year, in 1934, there was an unofficial but strikingly thorough ban on Hitler’s voice and picture in U.S. theaters,” it pointed out correctly. “Controlled by the fiction-magnates of Hollywood, the newsreel was required only to sidestep trouble.” Fortunately, “the public’s avid appetite for newsreels”—that is, for authentic, hard-hitting screen journalism—would be served by a bolder reporter. With the “lords of Hollywood” paralyzed, “Time saw its opportunity.”3

The boast on the March of Time title card (“a new kind of pictorial journalism”) was not just bluster. Unlike the newsreels, a sidebar chronically averse to agitating an audience prior to the featured attraction, prone to fawn or flinch before government officials or conservative exhibitors, the March of Time delighted in roiling the waters. In the context of the 1930s, the topics the series tackled were daring, edgy, and boundary-pushing. “What principally distinguishes March of Time is its outspokenness, its fearlessness, its production qualities and its desire to remain impartial, yet painting as accurate a picture as it can of the current topics selected for coverage,” judged Variety. Abel Green, Variety's editor, placed the screen magazine in a class of its own. “More than a newsreel … it’s a most skillful visualization of important and little known news happenings.”4

The auteur of the March of Time, the man whose vision and tenacity made the series meet its monthly deadline, was not Henry Luce, the tycoon behind the Time-Life media empire, but Louis de Rochemont, a veteran newsreel man turned documentary pioneer. Raymond Fielding, the historian of the March of Time series, described him as “the general in the front office, providing the will, the energy, and the central idea which propelled the March of Time to success and prominence.”5 Besides command and control, however, he also sold and promoted, shilling the series with the vigor of a studio ad-pub boy.

De Rochemont was hired by Roy E. Larsen, vice president of the Time empire, and second only to Luce in influence. In a burst of multimedia synergy, Larsen launched the radio and motion picture versions of the magazine, in 1931 and 1935, respectively. Of the nonprint aspects of the Luce empire, he took a propriety interest. “When it came to the March of Time and movies and radio, [Luce] was my partner,” Larsen recalled. “In everything else, I was his.”6

In 1934, Larsen lured de Rochemont away from Fox Movietone to join the editorial staff of Time and become vice president and production manager for the project on the drawing board. De Rochemont was then the dashing embodiment of the intrepid globetrotting newsreeler. In 1922 he had covered the destruction of the Smyrna by Kemal Atatürk; in 1924, the opening of the tomb of King Tutankhamen; and in 1930, the British Raj in India. To Larsen’s knack for media cross-pollination, he brought a cameraman’s eye and practical experience to the job of filmmaking. In September 1937, when Larsen left the March of Time to take the reins of Life, the company’s newly launched platform for photojournalism, de Rochemont became general manager in charge of all motion picture activities. By then, he had also picked up Larsen’s gift for promotion.

The March of Time’s courtship of controversy was abetted by its relative immunity from censorship, whether external (from the state) or internal (from the studio system). In 1935, when the March of Time was launched, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America considered bringing the series under the aegis of the Production Code Administration. After all, the MPPDA reasoned, the use of dramatic reenactments qualified the series for the same scrutiny as other short subjects. Yet its “pictorial journalism” shingle, Lucean lineage, and somber approach made even the Hays office balk. Unique among shorts, the March of Time escaped oversight from Joseph I. Breen.7

State and city censorship boards were not as deferential. The March of Time’s penchant for controversy dismayed official censors while testing the limits of their authority. The right of the boards to censor motion pictures for moral transgressions was conceded, but the censorship of a news medium for political commentary was a gray area contested as an abridgment of free expression. Unaccustomed to dealing with hard-hitting, opinionated screen journalism, the boards vacillated—alternately clamping down and letting slide, bowing to pressure and then folding under backlash.

A typical dustup occurred in the wake of FDR’s proposal to expand the membership of the Supreme Court from nine to thirteen members, an ill-fated scheme to pack the judicial branch with justices friendlier to his New Deal agenda. In a report from its April 1937 issue entitled “Number Nine,” the March of Time aired both sides of the uproar set off by FDR’s gambit. The president was shown speaking in favor of the measure in a fireside chat and Sen. Burton K. Wheeler (D-MT) was shown speaking for the opposition. Unimpressed by the evenhandedness, the Kansas State Board of Review, chaired by a staunch New Dealer named Mae Clausen, demanded that the March of Time eliminate the remarks by Senator Wheeler. “We feel this dialogue is partisan and biased,” Miss Clausen informed the regional RKO distributor, who complied and cut the senator’s response—thereby igniting a coast-to-coast firestorm.

As Miss Clausen was deluged with criticism from the nation’s newspapers, the March of Time garnered reams of front-page coverage and editorial support. “To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a statement on a national political issue by an accredited authority like a United States Senator has been censored from the screen by a State Board,” responded de Rochemont, before making a calculated comparison. “We are used to censorship like that in our foreign editions (by foreign powers) but it’s new to us here.” The New York Herald Tribune picked up on the theme. “Miss Clausen has functioned precisely as a state censor in Berlin, Moscow, or Rome would have functioned to give her leader the limelight and his critics ‘the works.’”8 Chastened, Miss Clausen backed off and cleared the reel for release.

The pattern was repeated throughout the 1930s: the March of Time would spark a controversy, a censor board would attempt to cut or ban the offending issue, the decision would be roundly condemned by editorials around the country, and the besieged board would then hastily, shamefacedly, beat a retreat. The March of Time got publicity and esteem; state censorship of screen news got derision and discredit.

In September 1936 the March of Time released a report whose forthright editorializing heightened the contrast with the mealy-mouthed newsreels. Entitled “The Lunatic Fringe,” the issue dissected a trio of Great Depression–bred demagogues: the geriatric pension fund planner Dr. Francis E. Townsend; the antisemitic radio priest Father Charles E. Coughlin, and the fanatical preacher Gerald L. K. Smith, self-appointed successor to the assassinated Sen. Huey L. Long (D-LS).a The segment focused on the megalomaniacal Smith, who obligingly performed for the camera, providing de Rochemont with raw footage aplenty to harpoon the blowhard. In a visual vignette fraught with transatlantic reverberations, Smith sits at a table lighting and blowing out matches, a gesture that dissolves into newsreel shots of Mussolini and Hitler fanning the flames of hatred. Rehearsing his tirades before a mirror, haranguing the viewer in blurry tight close-up, Smith seems more cartoon than menace. Still, “in Gerald Smith’s sweating, bombastic oratory, serious commentators see the makings of a Fascist dictator,” notes the March of Time’s own serious commentator. The coda shows the tireless Smith in a railroad sleeping car yammering at train conductors and disturbing the sleep of weary travelers. As the locomotive screeches down the tracks, Smith’s ear-splitting voice is still hollering on the soundtrack.

Following the trail to its source, the March of Time shifted its sights from cantankerous domestic demagogues to the more sinister versions overseas. Unlike Gerald L. K. Smith, however, Adolf Hitler was not about to perform like a trained seal for the American newsreels. A personality profile followed by an exclusive interview being impossible, the March of Time settled for a behind-the-scenes look at his Reich.

From the beginning, the March of Time was not content to cede coverage of Hitler and Nazi Germany to radio and newspapers or, like the newsreels, to look away. The Nazi dictator first came under the lens of the March of Time in its second issue, released March 1935, when the newsreels were observing a virtual moratorium on Hitler imagery. Titled “Berchtesgaden, Bavaria!,” the report is the last and longest segment of a five-segment program. Silhouetted in shadows, sitting glumly, ominously, in a chair, an Adolf Hitler stand-in plots German rearmament and territorial expansion. “In two short years, Adolf Hitler has lost for his country what Germany had nearly regained—the world’s sympathy,” says Van Voorhis. Shots of Hitler mesmerizing a crowd of 500,000 and of steel mills firing up for munitions production show why this “lone strange man” has made all of Europe nervous and fearful, feelings an American moviegoer in 1935 had good reason to share.

The wide-awake look at Hitler in the March of Time contrasted sharply with the willful blindness of the newsreels. The Lucians played up the difference, goading the newsreels for their cowardice and highlighting the fortitude of the screen magazine. “Unplanned, unorganized, unknown to movie audiences, what amounts to a national ban on pictures of Adolf Hitler has been in existence in the United States for many a month,” claimed a publicity release from the screen magazine in March 1935. “The motion picture trade is well aware of it, yet no one will admit or deny it. The fact remains but for rare fleeting glimpses, the screens of this country have not shown pictures of Hitler, nor have the movie theater loudspeakers resounded with his voice, for well over a year.”9

The March of Time promised to end the conspiracy of silence. “We feel that Hitler is too important a figure to be ignored,” declared Roy E. Larsen. “But for exceptional rare, brief glimpses, Hitler has not been seen on U.S. cinema screens, yet he is the topic of many discussions, his actions are internationally significant. Nothing can give so clear a picture of this, or any man, as talking pictures.” The newsreels howled their denials (“It’s a lie!” shouted back Cortland Smith, editor of RKO-Pathé) and pointed out that the March of Time, having no cameraman of its own in Berlin, relied totally on the newsreels of Fox Movietone for its library stock.10

Although not exactly giving blanket coverage to Germany, the March of Time, true to its word, kept an eye on the story. In June 1936, in a segment on the former glory of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Van Voorhis speculated that the territorial greed of Hitler and Mussolini was the main impediment to a restoration of the royal line of the Hapsburgs. During a screening at Radio City Music Hall, a showpiece picture palace whose mainstream clientele was less given to raucous outbursts than the newshounds of the Embassy Newsreel Theater, the crowd hissed at images of the two dictators.11

Seldom did the March of Time lose an opportunity to snipe at the Nazis. In June 1937, in a report on “Poland and War,” the narration chronicles the many “covetous enemies” that have blighted Poland’s tragic history and names the predatory nation most likely to do so again. “All Poles know that Adolf Hitler wants both Danzig and the Polish Corridor.”

Already more aggressive and comprehensive than anything in the newsreels, the preliminary encounters served as warm-ups to the most controversial and comprehensive motion picture report on Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Issued in January 1938, the March of Time’s “Inside Nazi Germany” was a revelation and a provocation. It exposed what the rest of American cinema kept under wraps.

The behind-the-scenes footage that was the reel’s inspiration and exploitation angle was shot by the roving cameraman Julien Bryan. A well-known explorer and lecturer, Bryan took his camera to exotic parts of the world and returned stateside to show the footage and talk about his adventures in a kind of chautauqua-with-film. In 1936, at Carnegie Hall, he presented a show of “all new motion pictures” entitled Soviet Russia 1935, a must-see for starry-eyed communists.12

Having secured entry into one totalitarian regime, Bryan angled for admission to another. As Bryan told the story, he was attending a function at the German Embassy in Istanbul when a Nazi officer berated him for the anti-Nazi bias in the American newsreels. Sensing an opening, Bryan countered that the newsreels were not permitted access to the marvels of the new Germany. If the Nazis wanted a fair shake, why not allow him into the country?13

To Bryan’s surprise, the Nazis took the bait. Arriving in Germany in September 1937, he shot some 25,000 feet of footage, all under Nazi supervision, about 1,000 of which (about 11 minutes) was incorporated into the issue.

In the prepublicity buildup for the release, de Rochemont gave the prosaic arrangement between Bryan and the Nazis a cloak-and-dagger spin. He maintained that Bryan shot the film surreptitiously and then, “after escaping Nazi censorship,” smuggled the footage out of Germany by way of Latvia.14 The magazine branch of Luce’s empire printed the same cover story. Life repeated the claim that “its editors believe [it] to be the first uncensored film ever brought out of Nazi Germany,” a fortuitous happenstance attributed to “Propaganda Minister Goebbels [being] presumably too busy with Mussolini’s visit to Berlin [in September 1937] to notice what was getting by his censors.”15 Not much got by Goebbels, but the skullduggery lent “Inside Nazi Germany” the cachet of smuggled goods.

The issue lived up to another part of the publicity buildup. On behalf of the March of Time, RKO sent out a press release that cast the issue in starkly anti-Nazi terms. “March of Time cameramen survey the scenes unknown to tourists,” it bragged. “The propaganda machine is shown functioning… . The sequestration of the Jews, banned by state edict from professions and business, is pictorially revealed, as is Hitler’s attempt to break down Catholic and Protestant resistance.”16 In truth, “Inside Nazi Germany” contained little in the way of pictorial revelation—Bryan’s camera was not hidden and he shot under the watchful eyes of Nazi handlers—but for the first time on screen a magnifying glass was held over a totalitarian nation bent on oppression at home and aggression abroad. That in itself was news.

“Jews are not welcome here”: cameraman Julien Bryan stole a quick glimpse of Nazi signage in the March of Time’s landmark episode “Inside Nazi Germany,” released in January 1938. (Photo by Julien Bryan/Courtesy the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.)

The issue opens on a note of deceptive serenity, for all the world like one of the chirpy travelogues that the screen magazine often supplanted on the motion picture program. “Show window of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany today is its capital city, Berlin,” begins Van Voorhis in the patented reverse predicate syntax that Citizen Kane lampooned to such devastating effect three years later. Shots of a picture-postcard Germany give the nation its scenic due: the Brandenburg Gate, the Zoological Gardens, and the outdoor cafes along the Ku’damm bustling with beer steins and good cheer, a tourist playground radiating “the air of prosperity” inhaled by “groups of playing, cheerful people.”

Looking around casually, “nowhere does the visitor see privation or hunger,” admits the Voice, before modulating its chipper tone for a darker inflection: “No sign of dissatisfaction with the Fascist dictatorship which controls their lives … a government whose campaign of suppression and regimentation has shocked the world’s democracies.” Unlike the frothy travelogues on the motion picture bill, where happy natives frolic in colorful costume for smiling American tourists, the March of Time promises to peel back the mask over the death’s head. “Only those who get behind the scenes know that this outward cheerfulness is the creation of Adolph Hitler’s fanatic little propaganda minister Paul Joseph Goebbels.” With his mastiff Goebbels, Hitler has “whipped 65 million people into a nation with one mind, one will, and one objective—expansion.”

Menacing footage of the rallies at Nuremberg and illustrations mapping out a German African empire paint a clear picture of the Reich’s imperial ambitions, but the Nazi vise grip also strangles the life out of the homeland. In the first of several staged sequences, the blade of a guillotine drops on a man prostrate on a chopping block. No less dire is a library shot taken during the Nazi boycott of Jewish goods on April 1, 1933, featuring boisterous brownshirts riding down a Berlin street in a swastika-festooned truck.

In reviewing the racial oppression that animates Nazism, Van Voorhis bellows out a word long banished from the feature film soundtrack. “Still going on as pitilessly, as brutally, as it did five years ago is Goebbels’ persecution of the Jews.” Though the footage of scrawled signs (“Jude”) and stars of David in white paint splayed across storefront windows require no translation, the complete sentences do. “Signposts at city limits bear signs reading ‘Jews Not Wanted’ and ‘Jews Keep Out,’” interprets Van Voorhis. Concealed or temporarily taken down during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the antisemitic signage wallpapers the Reich. Bryan scored a real scoop for this sequence, sneaking a brief shot of a segregated park bench. Explains the narrator: “Even in parks, if Jews are allowed at all, special yellow benches are set apart labeled, ‘For Jews.’” However, Judaism is not the only religion persecuted by a führer who will have no other Gods before him. Christian churches are desecrated and nuns are locked behind bars. “To the good Nazi not even God stands above Hitler.”

Being itself an organ of multimedia penetration, the March of Time obsesses over the all-pervasive reach of Nazi propaganda. In print (the jacket from Hitler’s prison memoir, Mein Kampf, initiates a montage of the author barking about “a super race headed for a great destiny”); on radio (from the Volksradio, the transmission belt for Goebbels’ bulletins, snippets from an address by Hitler, untranslated, crackle from the soundtrack); and from the medium before the eyes of the spectator (Nazi newsreels of military might and pageantry), the full range of modern communications is orchestrated to mold the pliable minds of the German masses.

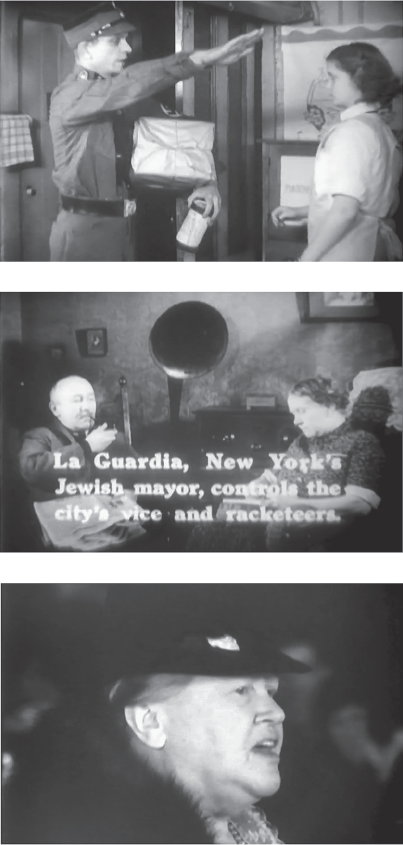

Media-savvy Americans, however, are wise to the tricks of Nazi propaganda. A staged sequence shows a German couple listening to a Nazi propaganda broadcast with the disinformation purveyed over the air translated in subtitles: “La Guardia, New York’s Jewish mayor, controls the city’s vice and racketeers.” The March of Time refrains from correcting so obvious a lie. Unlike the propaganda-fed German, the American knows that La Guardia, whose father was Italian and mother Jewish, was an incorruptible civic reformer and a practicing Episcopalian.

So that Depression-weary Americans will not be lured into thinking Germany is a land of abundance, the issue shows how ordinary Germans must scrimp and save to burnish the glory of the Reich. Even garbage scraps are saved “to feed Nazi pigs.” The war machine must be fed at all costs.

Yet the menace that is Nazism does not end at the Reich’s borders. Nazi “propaganda extends far beyond Fascist frontiers—and today Hitler expects every German everywhere to help spread the Nazi creed.” Via an intertitle and a quick edit, the story moves from Nazi Germany to another land where the blight of Nazism is taking root—America itself.

Adopting the Popular Front line, the commentary links Nazism overseas to its domestic fifth column. Here the issue unveils its prize catch, none other than Fritz Kuhn, leader of “the Hitler-inspired German American Bund” and the “loudest mouthpiece in this Nazi propaganda drive.” With live synchronous sound, in untranslated German, “Führer Kuhn” is shown preaching “orthodox fascist doctrine” to tens of thousands of American Nazis marching in Nuremberg-like pageants. Across a map of the United States, campgrounds dotted with swastikas sprout up like weeds on American soil. Glorying in it all, and not learning from the experience of Gerald L. K. Smith, Kuhn seized the chance to be immortalized by the Luce Empire—strutting for the cameras, collaborating on his own immolation on screen.

Fortunately, a people with native smarts and sturdy backbone resist the invasion. Interviewed upon his return to the United States, former ambassador to Germany William E. Dodd speaks out about the threat from Nazi aggression, but it is ordinary Americans who deliver the most stinging rebuke. In Southbury, Connecticut, the March of Time sits in on a town meeting where citizens debate whether the German American Bund should be allowed to build a camp on the outskirts of town. To the applause of his fellow citizens, a man speaks out against “Nazi agents masquerading as American citizens,” but the star of the meeting is a feisty Yankee matron. Framed in close-up, she is the picture of New England rectitude, a Puritan goodwife who in another century might have loaded a musket for her husband, or shot it herself. “Mr. Chairman, two of my great-great grandfathers and four of my great grandfathers fought for liberty. So did the other people of this town,” she declares in a voice as clear as a bell. “I call upon all of you here to keep the Nazis out!” The town hall crowd cheers. A newspaper headline reveals the decision of the people in a vibrant democracy: the American Nazis are sent packing.

Back in Central Europe, the blessings of democracy—freedom of speech, press, and assembly—are a distant memory. Riding like emperors in an open-air car, Mussolini and Hitler bathe in the worship of their multitudes. Lest anyone snicker at the smug potentates, Van Voorhis reminds viewers that “behind these leaders lies an unbroken succession of Fascist triumphs, military and political.” Life inside Nazi Germany can be summed up in three sentences. “Democracy is destroyed. The dictator is a demigod who can do no wrong. Propaganda dominates the nation’s mind.”

The final peroration—bracing enough in 1938, eerily prophetic in retrospect—pulled no punches. “Nazi Germany faces her destiny with the greatest war machine in history,” booms Van Voorhis. “And the inevitable destiny of the great war machines of the past has been to destroy the peace of the world, its people, and the governments of their time.” After that oracular prophecy, the triumphal sign-off sounds more like the Voice of Doom than the Voice of God: “Time—marches on!”

A series of images from “Inside Nazi Germany”: a reenacted scene of a Nazi storm trooper collecting garbage scraps from a German housewife (top); a reenacted scene of a German couple listening to a propaganda broadcast on the Volksradio (middle); and an authentic shot of a New England patriot speaking out against Nazism at a town hall meeting.

“Inside Nazi Germany” clocked in at 18 minutes—approximately the total running time for the three segments usually covered by each issue of the series. Underscoring the importance of the story, the March of Time released the exposé as its first ever single-topic issue.

Once the episode was wrapped, de Rochemont held a private screening at the March of Time headquarters in New York, allegedly to allow the German authorities to correct misrepresentations, actually to goad them into an official protest that could be milked for free publicity. Dr. Georg F. Krause-Wichmann, the German Vice Consul, and Fritz Kuhn, leader of the German American Bund and preening featured player, showed up. Each responded according to type. An apoplectic Krause-Wichmann demanded the deletion of scenes “prejudicial to the best interests of Germany and likely to be misunderstood by the American public.” An appalled Kuhn learned that the message of the medium was all in the editing. “If Hitler sees this film,” he moaned, “I’ll be ruined!”17

De Rochemont was thrilled. “There were storming and rantings,” he chuckled. “We fully expect that we will be subjected to retaliations by the triple alliance existing between Italy-Japan-Germany.” The producer also fully expected retaliation from opponents at home, but he vowed to stand his ground. “After escaping Nazi censorship in Germany, we have no intention of submitting to Nazi censorship in this country.”18

In fact, American not Nazi censorship bedeviled “Inside Nazi Germany.” Provocative by design, the release incited passionate debate and official pushback—over issues of journalistic integrity (was the film real or staged? made independently or under the eyes of the Nazis?), ideological slant (did the film condemn or promote the Nazi state?), and the very nature of news on film (should the cinematic medium even presume to address thorny geopolitical issues?). “Hardly ever in the history of pictures has any film, placed on exhibition, caused as much comment as the March of Time issue depicting the inside story of Germany of 1938,” declared publicist Dave Epstein.19

Taking the bait, the reliably purblind Chicago Board of Censors voted unanimously to ban “Inside Nazi Germany” on the grounds that it was unfriendly toward a nation officially friendly to the United States.20 Happy to stoke the fires of controversy, de Rochemont lashed back. “We believe that censorship of a painstaking and factual report of this kind is almost unprecedented in the United States,” he said. “It puts censorship in Chicago not on the basis of morals or taste but directly on a suppression of news facts. It thus becomes a direct attack on the principles of a free press.”21

“If Hitler sees this film, I’ll be ruined!”: Fritz Kuhn, leader of the German American Bund and featured patsy in “Inside Nazi Germany,” meets with Adolf Hitler in 1936, in a photo released by the House Committee on Un-American Activities in August 1938.

Like every commercial filmmaker in America, de Rochemont accepted the authority of censorship boards on matters of taste and morality—the kind best administered by the Breen office over Hollywood cinema—but he denied the state the power to suppress straight news reporting and political commentary. De Rochemont pledged to appeal the ruling and, if necessary, take his case to court. “Our lawyers are studying the Chicago ordinances relating to films and an appeal will be promptly made,” he warned.22

De Rochemont lined up a battery of big guns in his corner. He arranged for private screenings in Washington for members of the U.S. Congress and other powerful politicians, many of whom issued supportive blurbs. Secretary of State Cordell Hull called “Inside Nazi Germany” “definitely anti-Nazi and a lesson to all Americans.” Agreed Sen. Key Pittman (D-NV), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee: “I think it is highly desirable that the picture be seen by every American.” William E. Dodd’s seal of approval lent special weight. “The members of every American family, young and old, who believe in liberty and democracy, should by all means see ‘Inside Nazi Germany,’” said the former ambassador to Germany.23

Blistered by de Rochemont’s fervent defense, a tide of editorial opprobrium, and, most importantly, the displeasure of the city’s staunchly anti-Nazi Cardinal, George Mundelein, the Chicago Board overturned its initial ruling.24 “Passed by Censors Uncut!” boasted ads in the Chicago papers the next day. For the March of Time, the three-step tango of banning by a censorship board, followed by blasts of editorial contempt, followed by the board lifting its original ban was the best of all possible outcomes: after riding a raft of free publicity, the film played without restriction.

However, by way of collateral comeuppance, the intense scrutiny of “Inside Nazi Germany” focused attention on a long-standing and heretofore uncontroversial editorial practice: the use of dramatic reenactments of news events and the impersonations of real people by actors. A stock-in-trade of the March of Time since its inception, dramatic reenactments had never before much bothered critics or audiences, but the incendiary topic and high stakes put the untelegraphed transitions from authentic archival footage to staged reenactments into heightened relief. Ironically, or appropriately, the March of Time’s broadside at the media manipulations of Joseph Goebbels boomeranged back on the media manipulations of the March of Time.

Unable to obtain sufficient material to tell the full story, even with Bryan’s footage and library stock, the March of Time did what it always did and staged dramatic reenactments. A New Jersey enclave of anti-Nazi German Americans played the part of the Nazis in a snicker-inducing scene where a Nazi trooper “Heils” after receiving food scraps as well as in the depictions of the guillotine execution and of the nuns in prison. American spectators were smart enough to know that the radio broadcast denouncing Mayor La Guardia as a Jewish gangster was a lie, but were they smart enough to know that the scene itself was staged by the March of Time?

Sharp-eyed trade critics had no trouble telling New Jersey from Bavaria. Variety tut-tutted over “obviously” staged scenes, singling out “an execution (probably staged) [that] shows what happens to dissenters,” and the “absurdity of Nazi campaign to keep German laborers content [that] is vividly illustrated with staged radio sequences.”25

At this point, Julien Bryan weighed in. He objected to the false publicity purveyed by the March of Time—the breathless reports that the film had been smuggled out of Germany—and suggested sensibly that the series simply label the staged reenactments with a subtitled notice. Not wanting to burn his bridges with the Nazis, he stated flatly that the pictures “were taken with the full permission and cooperation of the Nazi government and were not intended in any way to do any ‘exposing’ whatsoever, but merely to depict the tenor of the German system.”26 Capitalizing on the furor, Bryan put together a lecture presentation on his Nazi footage, which he debuted at Philharmonic Hall in Los Angeles on March 21, 1938. Speaking in Chicago later that year, he again insisted that the pictures were all taken with “the full permission and cooperation of the German propaganda offices.”27

For one powerful motion picture entity, the mere transmission of Nazi-approved footage proved that the March of Time was in bed with the enemy. Warner Bros., the most stoutly anti-Nazi of the major studios, viewed “Inside Nazi Germany” as out-and-out Nazi propaganda. Acting on orders from Harry M. Warner, the studio banned the issue from all 425 of its affiliated theaters.28 To Warner, the pictures of a well-dressed, well-fed people, marching, singing, and laboring in “iron works and other plants going full blast,” overpowered the voice-over condemnations of the regime. “The effect and appeal of the motion picture is to the eye primarily,” Warner asserted. “Careful analysis has proven that the words of commentators when used in connection with motion pictures have but a small effect against the great effect of what is shown on screen.” Moreover, “nowhere in the picture is there any showing of ministers or priests in jail.”29 Not to mention—Warner didn’t—rabbis. “We don’t intend to make our screens a medium for the dissemination of propaganda for Germany no matter how thinly veiled that purpose may be.”30

At that, de Rochemont confessed himself flummoxed. “It is difficult to believe that Harry Warner authorized a statement which explained why his theaters did not run MOT’s ‘Inside Nazi Germany’ by saying that the picture is pro-Nazi propaganda” given the fact that “during the past 24 hours, the German consuls in San Francisco and Buffalo have lodged protests with city officials asking that it be withdrawn from the screen because of the lack of sympathy with their policies.” Clergymen, politicians, critics, Nazis, the Chicago Board of Censors—virtually everyone read the film as anti-Nazi.31

The bull-headed opposition of Harry M. Warner incited a rare entry into the fray by the grand man of the Time-Life Corporation himself, Henry Luce. “Mr. Warner’s assertion that the March of Time is ‘pro-Nazi propaganda’ is ridiculous,” Luce scoffed. “Mr. Warner also says that ‘movie audiences pay little or no attention to the sound that comes from the screen.’ This is an amazing observation to come from the man generally credited with introducing the talking motion picture.” Savoring the irony, the print mogul lectured the film mogul on the role of his own medium. Warner may think that the screen’s sole purpose was mindless entertainment, but the March of Time held loftier ambitions. “Fortunately, Mr. Warner does not control the entire motion picture industry,” jibed Luce.32

The duel between sound and image recapitulated an already old debate over whether the apparatus of cinema assumes the primacy of the ear or the eye. “A deaf moviegoer might consider the film more pro-Nazi than anti-Nazi,” conceded Life, before taking the company line and concluding that the volume of the voice-over drowned out the impact of the pictures.33 Also elevating the auditory over the optical, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League broke ranks with its patrons at Warner Bros. “To anybody not completely deaf, the March of Time reel will fortify all his biases in favor of democracy,” said Frank Scully, the well-known author, humorist, and bylined columnist for Variety, speaking for HANL’s executive board. “What the pictures show as taken inside Germany are, of course, what the Hitler regime wanted shown, but what was shot outside Nazi Germany is enough to have the reel either banned in Germany or cut to ribbons when shown, and in either case none of the dialogue will ever be heard there.” Calling the reel “unmistakably anti-Nazi,” Scully bestowed HANL’s imprimatur: “it should be seen by everybody with a suspicion of what Fascism means.”34

Finally, a few motion picture professionals resisted the whole notion that the screen should ever treat subjects that might upset the serenity of the moviegoer. Less concerned about whether the film leaned pro- or anti-Nazi, or whether image trumped sound, they fretted over how the motion picture theater—the bucolic oasis tucked away from the woes of the Great Depression and the insanity in Europe—was being hijacked by something so unsettling as political content. Martin J. Quigley of Motion Picture Herald was sad to see de Rochemont aligning himself with the Hollywood radicals “who in a headlong rush for a change in political, social, and economic order are in a fever of covetousness to gain the screens of the nation for their stump speeches.” Citing the press reports of boisterous hissing and intermittent “Heils!” when close-ups of Hitler filled the screen, Quigley shuddered at the prospect of the nation’s theaters being “converted into bedlams of turmoil and dissension” by an incendiary reel that “kindles the embers of violence.” After all, huffed Quigley, “theater patrons are supposed to be seated in comfortable opera chairs and not crouched behind barricades.”35 Noting that de Rochemont had taken the precaution of giving the film a sneak preview in the Yorkville district of New York to gauge the reaction of a German American audience, Variety drolly responded that “No seats were torn up and no disturbances marked [the] showing.”36

Machts nichts, shrugged exhibitors. “Both Nazi sympathizers and anti-Nazis seem to like [“Inside Nazi Germany”] because the film shows the strength of the Hitler regime while the commentary gives facts which are startling,” reported W. French Githens, president of Newsreel Theaters, Inc.37 However, most audiences—and not just in the politically engaged and disproportionately Jewish demographic in and around New York—rallied to the anti-Nazi message. On the opposite coast, word from the ticket window was emphatically one-sided. “Audience response much applause, thrilled with picture,” telegrammed the manager at the Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles.38 Encouraging reports also filtered back to the March of Time home office from Philadelphia (where audiences “nearly tore down the rafters with applause when the good Americans protested against Nazi racism”), Cleveland (“scenes of Americans protesting against Nazi activities drew heavy applause”), and Miami (“reaction unanimously very favorable”).39 With crowds enthused and business booming, exhibitors raked in the twin rewards of critical plaudits and box office profits.40

By way of wrap-up, the Film Daily offered the most perceptive comment. “Although the intrinsic news value of the material is not startling in view of substantial front-page accounts of Nazi history, the detached and organized treatment of ‘Inside Nazi Germany’ presents a coherent picture which brings home the full truth with uncompromising impact for perhaps the first time.”41 Both blueprint and bellwether, “Inside Nazi Germany” was an early harbinger of what would become one of the most popular motion picture genres of the twentieth century, the Nazi-centric documentary.

Released at the beginning of 1938—before the annexation of Austria, before the appeasement at Munich, before the rampage of Kristallnacht—“Inside Nazi Germany” was at once ahead of the cultural curve and on the crest of an oncoming wave. The syndicated columnist and radio broadcaster Walter Winchell, a fierce opponent of Nazism since 1933, lauded the film on his coast-to-coast radio show. “When the patriots of Connecticut are seen and heard outlawing Nazi camps, the audience responds, surprisingly enough, with 100% applause,” reported Winchell, who attended several screenings. By the end of the year, 100 percent applause for an anti-Nazi preachment would no longer be surprising.

Another seasoned reporter—Irving Hoffman, the Hollywood Reporter’s man in New York—was also monitoring the pulse of the audience. Taking in the charged atmosphere of a packed house at the Embassy Newsreel Theater, his reading preserves the vox populi response to Nazism in the tipping-point year of 1938.

Outside the Embassy, a barker reeled in Broadway passersby with shouts of “Standing Room Only!” and “No Refunds!” Sure enough, the place was mobbed, with standees overflowing into the lobby area for each show, including the midnight screening, and lines snaking down the street. Not since the breathtaking newsreels of the Hindenburg explosion on May 6, 1937, had the Embassy drawn such crowds. But if the audience for the Hindenburg newsreels had come to gape at a tableau of fiery destruction, the viewers of “Inside Nazi Germany” sought a glimpse into a mysterious country shuttered from motion picture view. The tension in the air—the anticipation of another kind of explosion, this one rumbling up from the crowd—was palpable. To help keep the lid on, a half-dozen uniformed policemen, nightsticks at the ready, circulated around the theater while plainclothes detectives mixed in with the paying customers.

When the houselights dimmed, the familiar brass fanfare trumpeting the March of Time had to wait as a title card from the management of the Embassy flashed on the screen:

The issue of March of Time you are about to see has caused much controversy. Our policy is to fearlessly present any worthy film produced by a recognized American producer. We therefore present uncensored and impartially the following subject.

A wave of applause greeted the declaration. The March of Time then submitted its own preamble:

The picture you are about to see has been mistakenly branded “a sensational expose.” The editors wish to state that the sole object of The March of Time is to present through pictorial journalism the significant events of our time.42

Settling in with the Embassy regulars, Hoffman described the action on both sides of the screen:

With the first shot showing rich and good food being served in the cafes, several spectators were heard to shout, “It isn’t true!” The commentator says that this is only a front, but the spectators seem to have beaten him to it. At another point, where bologna is shown, someone yelled, “That’s a lot of baloney! Why don’t they show you and tell you that it is made out of paper?” And when a half pound of lard was introduced, another spectator yelled, “Twelve million American unemployed haven’t even got that!” Goebbels is hissed, Hitler is hissed, and they laugh when a collector [of garbage scraps] and a housewife say, “Heil Hitler!” There are laughter and hisses when the reel shows how false propaganda is delivered over the radio. Fritz Kuhn is hissed. The people of Southbury, Conn., who make a stirring speech against the Nazis, are applauded and so is Ambassador Dodd.

A distinct but vocal minority also made itself heard:

However, generally, whenever the above reactions just recorded took place, the Nazi sympathizers in the house, numbering from a half dozen to a dozen and a half, applauded and once when the Nazi flag was shown, one yelled, urging the audience to STAND UP.

Drawing his report from attendance at three separate shows, Hoffman witnessed a violent flare-up only once. When a Great War veteran “in the back of the house, leaned over and hit a Nazi sympathizer,” a policeman “right on the spot, immediately yanked both of them and told them to fight outside if they wanted to.”

Immediately following the March of Time issue, as if to reassure audiences that not all was wrong with the world, a heartwarming clip unspooled as balm for the soul. Featuring banjo-eyed singer-comedian Eddie Cantor and superstar moppet Shirley Temple, the vignette made a heartwarming appeal for a cause whose name punned on the preceding title: the March of Dimes, the FDR-inspired charity dedicated to finding a cure for polio. Shirley drew warm applause and affectionate laughter when she suggested everyone watching send in a dime “just like me!” Behind him, Hoffman heard a woman sigh, “It’s a pity she has to grow up.”43