In 1934, Terry Ramsaye, editor of Motion Picture Herald and a former newsreel man himself, sought to disabuse newsreel editors of the notion they were in the news business. “The newsreel is not a purveyor of news and never is likely to become one,” he explained. “The newsreel ought to be an entertaining and amusing derivative—just so long as its avenue to the public is through the dramatic screen theater and along with the drama.” To aspire to the standards of print journalism or claim the protections of the First Amendment was to reach beyond the proper station of a trivial diversion. “Whether they know it or not, the newsreels, as they call them, are just in the show business, or they should by all means get into it.”1

More often than not, the content of the newsreels confirmed Ramsaye’s low opinion. Working the newsreel beat for Variety in the 1930s, Robert Landry wearily endured, week in week out, “a bewildering assortment of important happenings of worldwide consequence side by side with claptrap stunts important only to the press agents who arranged them.”2 No wonder at the first sound of a newsreel fanfare many moviegoers darted into the lobby for a smoke or a visit to the restroom before the start of the serious part of the program, the feature film.

Throughout the epochal 1930s, by common consent, “the greatest human interest story in the history of the newsreels” was neither the trauma of the Great Depression nor the rise of European fascism but the nativity of the Dionne quintuplets. On May 28, 1934, the birth of a litter of five identical baby girls provided a welcome distraction from the punishing economic news, not to say a sense of gratitude from parents without five new mouths to feed. The Quints (as Annette, Cecile, Emelie, Marie, and Yvonne were affectionately known) logged more screen time in the newsreels than the Spanish Civil War. RKO-Pathé News acquired an exclusive contract to film the five and churned out special issues documenting their every burp and coo. The advertising come-ons positively gurgled: “See them from dawn to bedtime … feeding … sleeping … bathing … laughing … their home … their parents … their doctor … nurses … special hospital … and their washline!” While the newsreel cameras panned diapers flapping in the breeze, the real news of the day was hung out to dry.

Surveys of audience preferences in newsreel content did not encourage a commitment to hard-hitting news coverage. Entertainment fare, fashion parades, and human interest stories rated highest, with women expressing an intense dislike for “strikes, war, crime, and politics.” The squeamishness of the distaff side was a constant worry. “Snakes, rats, and mice are taboo in the newsreels because of their effect on women,” reported a pamphlet issued by the New York and New Jersey Newsreel Theaters in 1939. “Children, dogs, and other pets, and humorous subjects, are most popular.”3 Reading the returns, William P. Montague, assignment editor for Paramount News, bemoaned the bind of a medium caught between “the prerogatives of a news agency and hence the social obligations of a news disseminating organization,” and a clientele that “would only accept their product if it was entertaining—good theater.”4

Even so, when chasing down a hot story, the newsreels might catch the scent and show a hustle and grit that rivaled the print press. In March 1932 the crime of the century (the kidnap-murder of the 18-month-old baby of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh) and, in January 1935, the trial of the century (the prosecution of the accused perpetrator, Bruno Richard Hauptmann) tested the journalistic mettle of the newsreels. The news of the kidnapping hit screens at the Embassy Newsreel Theater in New York within twenty-four hours of the first wire service alerts. Joining the manhunt, the newsreels sent out an all-points bulletin and—in a first for the medium—screened 8mm home movie footage, blown up to 35mm format, of the baby in his crib.5 During Hauptmann’s trial, the newsreels surreptitiously filmed actual on-the-stand testimony, including a withering cross-examination of the defendant by New Jersey attorney general David T. Wilentz. Outraged at the contempt for court decorum—or pretending to be outraged—Wilentz demanded the reels be pulled from circulation. Fox Movietone, Hearst-Metrotone, and Paramount complied; RKO-Pathé and Universal defiantly screened the clips and suffered no legal consequences.6

Bigger than the Spanish Civil War: newsreel darlings the Dionne Quintuplets in Reunion (1936), Twentieth Century-Fox’s homage to the doctor who delivered Canada’s most famous daughters.

In the most controversial brouhaha over newsreel policy in the 1930s, the medium itself became part of the story. On Memorial Day, 1937, outside the Republic Steel Plant in South Chicago, a violent melee between police and union strikers resulted in the death of ten strikers and the wounding of ninety more. Paramount News cameras recorded what looked to all appearances like a police riot. Eyeing the footage, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described “uniformed policemen firing their revolvers point blank into a dense crowd of men, women, and children and then pursuing and clubbing the survivors unmercifully as they made frantic efforts to escape.” The anti-union Chicago Tribune countered that the Paramount News cameraman was changing his lens when the police were provoked by projectiles hurled by communist agitators.

Despite its electrifying scoop, Paramount withheld the footage from its regular issue on the grounds that the “horror” of the scenes might incite violence. No newsreel segment with the Memorial Day footage had been edited or issued, no censor board had seen the footage to approve or ban it, and no government agency threatened Paramount with prior restraint. The editors simply slinked away on their own accord. In an example of the “voluntary restraint” that crippled the ability of the newsreels to run with a controversial story, Paramount itself deemed the pictures of labor unrest and police brutality as “not fit to be seen.” Unlike newspapers, explained Paramount editor A. J. Richard, newsreels were shown to large groups liable to succumb to “crowd hysteria” if exposed to such inflammatory imagery. “Our pictures depict a tense and nerve-racking episode which in certain sections of the country might very well incite local riot and perhaps riotous demonstrations in theaters, leading to further casualties.”7

The United States Senate disagreed. That July, an investigation into the incident by the Senate Civil Liberties Committee, chaired by Robert M. La Follette (I-WI), requested a print of the Memorial Day footage from Paramount News. On July 2, 1937, the self-censored pictures were screened to a packed Senate hearing room, the first instance of newsreel film being submitted into evidence before either body of the U.S. Congress. “This film, having been offered as evidence at a public hearing of the subcommittee, now becomes part of that committee’s public record and as such merits the attention and study of the citizens of this country,” declared Senator La Follette.8

Forgetting its earlier timidity and donning the garments of tribune of the people, Paramount News decided to reap the publicity windfall and release the footage. “More than a month has elapsed since the riot pictures were made. A month ago more than 70,000 men were on strike in seven states; feeling ran at white heat,” explained Paramount’s Richard. “Today, generally speaking, conditions have changed for the better and the feelings of yesterday have subsided.” Considering that the pictures had been “presented as evidence in a public hearing” of the U.S. Senate, Paramount News saw no reason not to release a special issue comprised of exclusive pictures of the clash, “made before and during the trouble … exactly as they came from the camera as a matter of public service.”9

The aggressive, gutsy stance of the newsreels over the Hauptmann trial footage and the instinctive, preemptive cowering over the Memorial Day footage illustrates the difference between a sensational crime story pitting a dastardly villain against an enraged public and an incendiary political story pitting labor against business, but it also shows the newsreels had no clear guidelines or professional ethos about what was fit to screen and what was best left on the cutting-room floor. Following up on the controversy over the Memorial Day footage, Box Office asked the editors of the five newsreels to comment on the state of screen journalism and the ethos of self-imposed censorship. The trade weekly was curious about “when newsreels may or may not be subjected to what is commonly known as self-censorship, or self-regulation, or non-circulation” and whether “this form of editing controversial and certain other subjects would prevent official censorship.” That is, what exactly did the newsreels self-censor and why?

To a man, the newsreel editors voiced support for the concept of voluntary restraint and said nothing about a professional commitment to aggressive screen journalism. Certainly, “the divorces, the juvenile crimes, the unspeakable incidents of life which must be dealt with by police hospitals and the prisons are ‘self-regulated’ out of the newsreels,” and this sort of editorial discretion was a good thing, went the consensus. “It seems that any editor’s job, by its very nature, implies at least some degree of ‘self-censorship,’ ‘self-regulation,’ and ‘non-circulation,’” said M. D. Clofine, editor of MGM’s News of the Day. “This must be particularly true in the case of the newsreel editor whose medium is sold to exhibitors of varied political faiths and social beliefs and reaches millions of people of all ages and classes.” Paramount’s Richard also praised the internal ties that bound the medium. “To this ‘self-regulation’ ‘self-censorship,’ if you please—I attribute the steady growth and tremendous influence of the screen news.” Not one of the editors mentioned the Spanish Civil War, Fascist Italy, or Nazi Germany as a news beat that might have been soft-sold by self-censorship.10

That willful avoidance was about to change. Though the newsreels remained temperamentally averse to hard-hitting news coverage, the accelerating momentum toward war in 1938 thundered too loudly to ignore. On March 12, 1938, Nazi troops breeched the Austrian border, annexing the nation into the greater Reich in a territorial grab known as the Anschluss. Two days later, Hitler marched victoriously into Vienna. Throughout that spring and summer, the fragile democracy of Czechoslovakia was up next on the Nazi chopping block. In October the ax fell. It was awesome theater and momentous history—made for the motion picture camera and, sometimes, staged for it.

Meanwhile, the Far East was also exploding. Though the remoteness of the battlefield, the Euro-centricity of America, and the fact that the newsreels were all headquartered in New York made the Japanese war on China seem less of an immediate threat, Americans, who were overwhelmingly sympathetic to the Chinese, were not without a rooting interest in the match between the Asian giants. Moreover, the enormous territorial expanse and the absence of clear lines of military authority across China were boons to newsreel access. Amid the chaos on the ground, the newsreels were more liable to elude coercive restrictions. As a result, the most spectacular and bloodiest footage of combat projected on screens in the 1930s—surpassing even the carnage brought back from the Spanish Civil War—was shot in China.

The first combat footage of Americans under fire in China testified to the unique pull of the newsreel medium. On December 12, 1937, Japanese warplanes attacked and sank the U.S.S. Panay, a navy gunboat patrolling the Yangtze River. Universal Newsreel, Fox Movietone, and MGM’s News of the Day all got gripping footage of the incident: the Japanese aerial attack, sailors returning fire from machine guns mounted on the boat’s deck, bombs exploding in the river, and the actual sinking of the gunboat while the crew dove overboard. The after-battle report showed survivors fleeing downriver, tending the wounded, identifying the dead, and dodging Japanese patrols.

Throughout the Panay incident, the newsreel cameraman was front and center as audience surrogate, narrating his own daring escapes while keeping the action in focus. Universal Newsreel cameraman Norman Alley, who had been wounded during the attack, was handed a $5,000 check upon docking in San Francisco with his prize footage. To capitalize on the scoop, the turnaround time from photography in China to projection in America set a newsreel speed record. Advertised on marquees above the featured film title, the newsreels were playing in Los Angeles on December 29, 1937, and in New York the next morning. Universal bundled its footage into a special issue, Bombing of the U.S.S. Panay, while Fox Movietone and News of the Day highlighted the material in their regular newsreel issues. The American government censored not a foot. “The whole town’s talking about those Panay bombing newsreels,” reported the Film Daily, adding to the chatter. “Looks as if the various newsreel organizations came through with very graphic portrayals.” The report concluded with a proud comment on the singular attraction of newsreel imagery: “All the newspaper accounts combined do not make the impression that the sight of these films stirs in the beholder.”11

Leaving an even deeper impression was the newsreel coverage of the Japanese depredations on the civilian populations of Shanghai and Nanking in 1937. “It is likely that never before in the history of newsreels has there been such gruesome material on display,” wrote an appalled Wolfe Kaufman in Variety. “The Spanish stuff was largely censored, as [was] true of almost all cases in the past. Here there is no sugar coating. It is war at its cruelest and most vicious, caught by an impartial camera eye. Bodies are strewn right and left. Blood is seen on all sides. Here a headless corpse, there a legless carcass. The scattered pulp of what was once a head is shown. A truckload of scarred and broken and torn bodies, piled carelessly one atop the other, like so much garbage. It’s not the kind of stuff to be looked at by anyone with a sensitive stomach. Women are not likely to be able to take it at any time. But, once seen, the effect will take a long time to wear off and the moral lesson is bound to stick.” Kaufman called the tableaux of death “Grim Reaper material.”12

As if wars in Spain and China and the forward march of Nazism in Europe were not enough to spur initiative, the competition from a bigfoot interloper also sharpened the edge of the newsreels in the late 1930s. Since its premiere in 1935, the monthly screen magazine the March of Time had played critic’s darling to the newsreels’ whipping boy. The Academy Award bestowed on the March of Time in 1937 “for having revolutionized one of the most important branches of the industry—the newsreel” rubbed salt in the wound. Insulted and chastened, the easygoing, trouble-averse newsreels sought to recoup a measure of self-esteem by downplaying the inane interludes and stepping up the serious coverage. Of course, the newsreels never abandoned the fashion parades, dumb yuks, and sports highlights, but the ratio of fluff to substance began to tilt toward weightier topics. Looking ahead to 1938, Paramount editor A. J. Richard said “the function of the newsreel must be concentrated more than ever on the presentation of spot and live news—economic, political, factual, industrial—to the full extent of the screen time at our command. The injection of vaudeville acts and of entertainment material that properly belongs to shorts does not make a true newsreel.”13

Whenever the newsreels underwent a personality change, the trade press critics knew whom to credit. The March of Time “has a daring that is little by little being approached by the other reels in their handling of highly controversial subjects,” Variety’s Roy Chartier observed. “For years the standard newsreels were guided by many ‘don’ts’ for various reasons, but mostly through fear of censorship.” The screen magazine had shown the newsreels that their true media kinship was with print journalism not Hollywood entertainment. “Many [newsreel] editors were afraid to try to duplicate in film what newspapers put into print or pictures,” said Chartier. “The March of Time has definitely acted as an influence in this direction.”14

The influence, however, was a trend not a transformation. In August 1939, days before German troops invaded Poland to ignite war in Europe, the writer Robert Meltzer broke down the ratio of fluff to substance in a recent program at a newsreel theater:a

About thirty minutes of the hour were taken up with variety shorts showing odd occupations, strange lands, a Parisian hairdresser at work (“he models in hair like a sculptor in clay”) and similar edifying hors d’oeuvres. Then about fifteen minutes were devoted to the examination of such semi-newsworthy items as the amazing number of uses to which Madison Square Garden is put each year. And then came fifteen minutes of newsreels. Something like ten of these covered the fields of high diving and women’s jewelry with commendable thoroughness, which left around five or six minutes in which to cover the war crisis.

Meltzer’s critique was more acute because he recognized the potential impact of the newsreel in the media hierarchy, a potential that would only be fulfilled after American entry into World War II. “You may get more complete coverage in reading your newspaper and it may be faster; you may get your news more quickly yet over your radio; but through neither of these media do you get the immediacy and the full three-dimensional awareness of what is happening that a newsreel can transmit.”

Meltzer had a final point to make about the newsreel experience. Listening to his fellow newsreel watchers hiss Hitler and cheer FDR, Meltzer took heart from the vigor of the communal chorus. The participatory spirit was not just an expression of the vox populi, but proof positive that the American demos remained fearlessly opinionated. “This is an extremely important thing,” he emphasized. Unlike the newspaper or the radio, while watching a newsreel “you can join in with your fellow men in reacting to world events.” Sitting in a theater, and seeing the face of British prime minister Neville Chamberlain, still proud of having negotiated the Munich Pact, “hearing him try to justify his shameless policy of intrigue and betrayal and having your feelings echoed or opposed by everyone else in the house—there’s a stirring and in this day extremely important phenomenon. What you experience is a Gallup Poll come to life.”15

Beginning in 1938, the last full year of nominal peace in Europe, all that the medium could be—as archival memory, as screen journalism, and as an arena for democratic expression—was realized when, after years of lackadaisical, hit-and-miss coverage, the newsreels, at long last, took a cold, hard look at Nazi Germany.

The media wraparound of 1938—first, scattershot radio reports, followed by newspaper headlines, then newsweekly articles, and finally newsreel pictures—defines a news-and-information experience light years away from the round-the-clock, wall-to-wall digital sensorium of the twenty-first century. Still, the infrastructure for the Age of Too Much Information was already settling into place. The problem was not the state of the technology but the flow of information. Getting the story—especially the images—was a promethean task for journalists covering Nazi Germany.

Radio, the medium that pervaded the atmosphere of American culture in the 1930s, sparked the communications revolution. Live shortwave transmissions had lately edged aside the newspaper wire services for up-to-the-minute, on-site coverage of foreign affairs. On March 13, 1938, the day after the Nazis invaded Austria, CBS inaugurated its pioneering World News Roundup, a series featuring live broadcasts from European capitals. The head of CBS’s European division, based in London and then reporting from a tense Vienna awaiting Hitler’s arrival, was the soon-to-be-legendary Edward R. Murrow, even then recruiting the stellar lineup of correspondents destined for broadcasting immortality as his dauntless “boys.” Despite Nazi censorship and technical glitches, William L. Shirer, Murrow’s man in the belly of the Third Reich from 1937 to 1940, struggled to find the words to describe the street-level brutality and global ambitions of Nazism. At NBC, Dr. Max Jordan, a native German speaker with well-placed informants in the Nazi hierarchy, manned the same post for CBS’s better-financed rival. Both regularly locked horns not only with Nazi censors but with news directors in New York who seemed more interested in broadcasting live performances of children’s choirs than Hitler’s speeches in the Reichstag.

As the momentum toward war in Europe escalated, Americans flocked to the electronic medium for breaking news and hourly bulletins—a shift in media allegiance that deeply distressed motion picture exhibitors. During an international crisis, attendance at movie theaters plummeted. On March 12, 1938, broadcasting from Vienna, Max Jordan patched through a live German broadcast of Hitler speaking from his hometown of Linz, a you-are-there moment the other media could never match.16 The blast of news bulletins and the threat of foreign invasion were very much in the air that year, an emotional link confirmed on October 30, 1938, by the famous Halloween eve broadcast of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds by Orson Welles’s CBS radio series Mercury Theatre on the Air. By mimicking the breathless urgency of on-air announcers interrupting regular programming and the static crackling of shortwave reception from overseas—a parodic mode that eerily echoed the real radio bulletins—Welles set off a panic on the eastern seaboard with the fake news that extraterrestrials were invading New Jersey. On the brink of the next world war, The War of the Worlds sounded like a remote pickup from the European bureaus of CBS or NBC news.

Not being able to compete with the immediacy or pervasiveness of radio or the detail and comprehensiveness of the newspapers, the newsreels sold themselves as a vital motion picture supplement to news already known and heard. Perhaps only once, in the biggest newsreel scoop of the 1930s, did the medium record a sight that beggared the impact of print or sound, that absolutely had to be seen: the death throes of the Hindenburg, the German zeppelin that exploded in flames while coming in for a mooring at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937. For the newsreels, the tragedy was a rare piece of luck: the scheduled mooring of the vessel was a preplanned, stationary event, so cameras were set up, ready to capture a routine landing when the explosion scorched their lenses. The cameramen rushed back to the newsreel offices in New York where the footage was developed, edited, narrated, and scored in mere hours. The next day—and for days afterward—audiences packed sold-out shows at the Embassy, watching mesmerized as the newsreels unspooled scenes of the conflagration, again and again, in slow motion, from multiple angles.

The next year, the flames from the Nazi vessel must have flickered like foreshadowing: 1938 witnessed three earth-shaking episodes of Nazi aggression the newsreels struggled to capture. Two projected Nazi aggression outward, one turned the violence inward—the annexation of Austria in March, the invasion of the Czechoslovakian Sudetenland in October, and the pogrom against the Jews in November. Cumulatively, the three acts pushed the newsreels to confront a story that since 1933 had mainly been whitewashed, downplayed, or ignored.

Being a territorial grab long expected, the annexation of Austria found the newsreels ready and waiting on the streets of Vienna. On March 14, 1938, as Hitler entered the city, Universal and RKO-Pathé each had a newsreel cameraman in position to record the final hours of Austrian sovereignty, but, as usual, the Nazis controlled access to motion pictures of the Nazis in action. Both men were hauled off to jail by the invaders. After protests by the U.S. Embassy, the cameramen—Universal’s Julius Jonak and an unidentified stringer from Pathé—were released. As in Germany, the American newsreel companies had no option but to clear their footage with the Nazis. They also exchanged clips, paying a fee for the dynamic Nazi footage of Hitler riding into Vienna to the cheers of rapturous throngs of newly made subjects of the Third Reich.

On March 21, 1938, newsreel pictures of the Anschluss arrived stateside by ship for screenings at the Embassy Newsreel Theater and Trans-Lux Theater on Broadway that same night. “Actual coverage of history-making event, absorption of Austria by the Nazi government, was as carefully and calmly worked out by the camera crews as handling of a big Fifth Avenue parade, with different locations spotted en route of march, newsreel truck going along in procession and other details,” Variety asserted, neglecting to mention the arrests of the cameramen or the restricted access.17

Yet while as dependent as ever on Nazi-approved footage, the newsreels were no longer uncritical conduits for Nazi propaganda. As scenes of Hitler’s ride into his hometown of Linz and his prize Vienna unspooled, commentators cautioned spectators to watch skeptically. “The newsreels confess that not all of the photography emanating from Austria is to be believed, telling only part of the story,” Variety reported, suspecting that not all Austrians were the joyous welcomers panned by the German newsreel cameras. “The narrators talk about the tragedies which followed the ‘peaceful’ march, and which the cameras can’t show.” Nazi film or not, however, “it’s historical and ought to be seen. Especially that close up of Hitler,” seen savoring his first real taste of territorial conquest.18 Historical it was—but now the footage was branded as filmed or filtered by the Nazis.

After the Anschluss, the world spent the rest of the spring and the summer of 1938 nervously awaiting Hitler’s next gambit. The smart money was on a jutting piece of real estate in Czechoslovakia that the Nazis called the German Sudeten Territory, an enclave populated mainly by ethnic Germans. The land had been ceded to Czechoslovakia in the Treaty of Versailles, which made it doubly coveted for dominion by the Third Reich. On September 12, 1938, Hitler made a territorial demand that pushed Europe to the brink of war. In a speech before 30,000 ecstatic followers at Nuremberg and millions more by loudspeaker and radio, he demanded that the “oppression of Sudeten Germans must end and the right of self-determination be given to them.” Czech president Edvard Beneš was a liar in league with Jews and Bolsheviks, bellowed Hitler. He threatened the use of military force to liberate Sudeten Germans from the yoke of Czech tyranny.

Hitler’s speech was carried live by both the CBS and NBC radio networks, with CBS fading out the speech for translations by Edward R. Murrow and NBC providing near simultaneous translation and analysis from Max Jordon. All that month, radio interrupted regular programming for scary updates. Speaking at the Sports Palace in Berlin on September 26, Hitler solemnly assured France and Britain that the Sudetenland was absolutely his “last territorial demand.” Handling the broadcast for CBS, William L. Shirer never forgot the “fanatical fire” in Hitler’s eyes. “For the first time in all the years I’ve observed him, he seemed to have completely lost control of himself,” Shirer wrote in his diary that night.19

Americans heard it all play out on radio. “European war situation has caused one of the biggest ether jams in the history of broadcasting,” reported Daily Variety, “ether” being archaic trade lingo for the radio airwaves. “Special programs, bulletins, and news flashes cutting into the regular schedules yesterday [September 26th] along with the hour and ten minute talk of Hitler constituted heaviest load of current eventers networks have ever handled.”20 Manning the microphone in New York for CBS, H. V. Kaltenborn kept a 24-hour vigil, sleeping on a cot in the newsroom.b

Three days later, desperate to avoid hostilities, British prime minister Neville Chamberlain and French prime minister Ėdouard Daladier rushed to Munich to negotiate a deal to prevent war. Signed on September 29, formally issued on the 30th, the negotiated agreement—the Munich Pact—sealed Czechoslovakia’s fate. In Berlin, NBC’s Jordan scooped CBS’s Shirer by reading and simultaneously translating the protocols of the pact on live radio. On October 1, Nazi troops crossed the border and absorbed the Sudetenland into the Reich.

Although radio owned the fast-breaking story (“Radio is romancing with destiny these days,” wrote Robert Landry), the newsreels claimed a piece of the Czechoslovakian drama.21 As the crisis raced toward its climax, Landry and his colleagues at Variety, with a rising sense of dread and making no attempt at reportorial objectivity, watched the screen and diagnosed the anxiety attacks inside New York’s newsreel theaters.

“History unreels here this week” was Variety’s succinct description of the Embassy program as the Czechoslovakian crisis intensified in the last weeks of September. The next month, with the Munich Pact signed and Czechoslovakia shredded, the reporters looked on helplessly as Europe hurtled toward the abyss. “History in the making is the way Fox describes the Embassy’s feature clip, and history it is,” marveled Variety. “For here with all the inordinate pomposity dictatorial arrogance could muster, the victory of militarists over democracy is shown, and with no holds barred.” Fox Movietone News commentator Lowell Thomas described a “chastened” Chamberlain and Daladier, “taking the bitter pill of subjugation from Hitler and Mussolini” while signing the Munich Pact, the penmanship lingered over in close-up. In crosscut juxtaposition, the dictators bathe in the adoration of wildly cheering crowds in Berlin while Chamberlain, deplaning at Heston Airport outside of London, waved a white piece of paper over his head.22

After Munich, the sense that the war alarums from Europe were not wild fear mongering but an emphatic future tense was taken for granted by Variety’s clear-eyed sentinels. “War clouds continue to dominate the reels and well they might since every sector of the globe is experiencing the fever,” read the eyewitness report in December 1938. “It’s a seething universe, one that’s continuing to arm in the event of an emergency, bent upon reaching a peak crisis that will ultimately result in another world conflagration.”23 Chronicling the headlong rush into the fire, the reviewers seem like helpless onlookers to a manmade disaster.

As the newsreels screened the headlines in twice-weekly issues, the monthly March of Time continued to set the gold standard for comprehensive motion picture journalism. On April 15, 1938, it released “Nazi Conquest—No. 1,” an ominously titled segment making up around 60 percent of its issue. In a nod to “Inside Nazi Germany” (January 1938), the previous exposé, it was billed as “Inside Nazi Austria.”

The issue opens with a self-reflexive nod to the venues that served as home base for the March of Time: exterior shots of the crowds flocking around the fronts of the Embassy and Trans-Lux theaters in New York. “In a world aflame,” Americans have become ravenous newshounds with “an ever increasing interest in world affairs,” declares narrator Westbrook Van Voorhis. Either because Americans have also cultivated an ever-increasing interest in how the news is gathered or because the media’s favorite story is always its own, the episode gives extensive coverage to a behind-the-scenes look at the business of overseas news gathering, highlighting the enterprising radio reporting of NBC not CBS—doubtless because RKO, which distributed the March of Time, was financially underwritten by RCA, NBC’s parent company. The vignette stars correspondent Max Jordan, who scoops the competition with the report that German troops have breached the Austrian border, making the nation “a new outpost in the ruthless Nazi realm.” Shown in close-up, the pages of Mein Kampf are turned so viewers may see their prophetic significance for the case at hand—and read Hitler’s prose as a promise of things to come.c

The face of appeasement: British prime minister Neville Chamberlain exits the Hotel Dreesen in Bad Godesberg. Behind him is Nazi foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, September 23, 1938.

Even in the transformative year of 1938, however, resistance to screen news of the Nazis remained stubborn in some quarters. Bizarrely, Warner Bros. was no happier with “Nazi Conquest—No. 1” than with “Inside Nazi Germany.” Again, despite a consensus by “impartial observers” that the March of Time review was “an unbiased presentation of Hitler’s Austrian coup, ending with the implication that he may seek further expansion and military power, or meet his downfall attempting it,” the studio banned the issue from its theaters.24

The prescient March of Time also anticipated the final act of the Czechoslovakian crisis. In July 1938, during preparations for its report “Prelude to Crisis,” editor Louis de Rochemont had taken the precaution of asking Czechoslovakian president Edvard Beneš to go before the cameras for an address to the American people should what was feared come to pass. “We have been working hard during the last 20 years and have accomplished a great deal,” said Beneš, referring to the fragile democracy enjoyed by the Czechs since the Great War. “We have tried and are still trying honestly to be just, as much as human beings can be. We hope that we shall be able to continue our work in the future, believing that international peace can be saved and honestly maintained by pacific means.” On September 19, 1938, Beneš gave the green light to the Paris bureau of the March of Time to release the clip, which relayed the go-ahead to de Rochemont.25 The appeal was quickly edited in to the final cut of “Prelude to Conquest.”

Despite its attempts to stay ahead of the story, the monthly screen magazine, even more than the twice-weekly newsreels, was made yesterday’s news by the quick-march of history. In the last week of September, just days before war was averted by the capitulation at Munich and thus dated even as it screened, the March of Time released its report on the Czechoslovakian crisis. Programmed before the Fred Astaire–Ginger Rogers musical Carefree (1938) at Radio City Music Hall in New York, the issue generated the kind of audience response more usually heard at the Embassy. Hitler was boisterously booed and Beneš, leader of the besieged and soon to be engulfed nation of Czechoslovakia, was roundly applauded.26

At some point in 1938, whether watching at Radio City, the Embassy, or neighborhood Bijous across America, newsreel audiences seem to have understood what the images of unchecked aggression and martial pageantry portended. Not voice-overs, or intertitles, or barked threats in a foreign tongue, but just the parade of military might and the shots of smug dictators watching from the stands was enough to sense where the parade was heading. In May 1938, flush from the triumph in Austria, Hitler visited Mussolini in Rome, where the Italian dictator staged a colossal festival of war games in honor of his ally. Newsreels showed the two dictators enjoying the show. “While the war games are unspooled with principals apparently in a state of camaraderie, the grim undertones of the reels have their startling effect upon an audience,” commented Variety, chilled at the sight.27

Yet for all the history that unreeled in the newsreels that year, it was the images that could not be obtained that frustrated newsreel editors. “War clouds over Europe, with stress on Austrian and Czechoslovakian situations, dominate new show here [at the Embassy],” reported Variety’s Mike Wear the week after the Anschluss. “With no really live pictorial news on sudden moves abroad, news weekly lads scurried for latest shots of leaders in wartime preparations or best library material.”28 Looking back over the year’s items, Wear summed up the twin dilemmas facing American newsreel journalism in the 1930s. “It was a year of swift happenings,” he understated, bemoaning the chronic lack of access and timeliness. “Photographically, the difficulty is making a comprehensive story; topically, the difficulty is securing early shipment.” Against the immediacy of radio bulletins and newspaper headlines, the newsreels looked “downright stale” by comparison. Hobbled by a scarcity of pictures, they were left to review news that audiences had already read and heard about, news that was, even as the images flashed on screen, overtaken by events.

As the commercial newsreels and the March of Time struggled to create a playbook for screen journalism, a third form of news on screen made no pretense of timeliness, seeking instead to lend perspective and meaning to the dire events of 1938 with a rueful, retrospective vision. A melancholy eulogy for a murdered democracy, the feature-length film Crisis (1939) served as a prewar prototype for a motion picture genre that would dominate the second half of the twentieth century—the World War II archival documentary.

The building blocks for Crisis were inherited from the handful of archival compilations of Great War footage made in the early 1930s, the pioneering retrieval-reenactment techniques of the March of Time, and the agenda-driven reportage of the Spanish Civil War documentaries. Enlivened by segments of instructional animation (maps of Nazi aggression, illustrated with swastikas bleeding over German borders and blackening the territory of other nations), the repurposing of newsreel footage showed that “library material” would never again be left on a studio shelf, shown once and then tucked away to be seen no more. Newsreel footage was becoming a central repository for the cultural memory of the nation.

Crisis was conceived and directed by Herbert Kline, the former editor of New Theatre and Film who had served a self-taught apprenticeship on the Spanish Civil War shorts Spain in Flames (1937) and Heart of Spain (1937). In spring 1938, Kline slipped into Czechoslovakia, gaining the trust of Czech Nazis in the Sudetenland with a forged letter purporting to be from German American Bund leader Fritz Kuhn. After the Munich Pact, assisted by cameraman Alexandr Hackenschmied and stage director Hans Burger, Kline went underground in Prague to complete post-production work. “We worked in fear of discovery and the consequences but got away with it, feeling like actors in an anti-Nazi drama,” he recalled years later. With the connivance of anti-Nazi Czech customs officials at the Prague airport, he smuggled the film to Paris “in two suitcases so heavy I could barely lift them on the plane.” At Paris customs, Kline switched his story again with a forged letter claiming he was a March of Time cameraman carrying harmless travelogue footage of the Czechoslovakian countryside.29

Back in New York, foreign correspondent Vincent Sheean, the best-selling author of the Spanish Civil War memoir, Personal History, wrote the commentary for Crisis, and actor Leif Erickson, a Group Theatre artist-activist just breaking into Hollywood, recorded the brawny narration. An original score, by the Czech composer Walter Susskin, was also added.

Neither newsreel snippets nor a March of Time synopsis, Crisis was a comprehensive documentary record of the betrayal and destruction of a European democracy. “The newsreels are too hurried, too sketchy to give the public any more than a suggestion of what is going on,” Kline told New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther. “It takes a careful, reasonable analysis in visual terms which may be understood to give the moviegoing public a conception of the forces impelling a great conflict (such as that in Czechoslovakia).”30 Covering events from the Anschluss to the Munich Pact, the film already assumes the inevitable outbreak of a wider war in Europe and is sending out an urgent alarm.

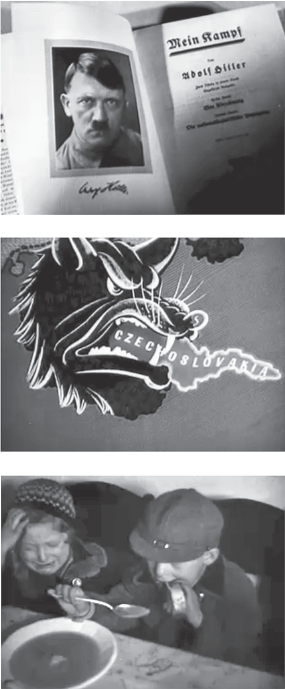

Crisis opens with a picture of the jacket of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, further imprinting the work as the sacred book of Nazism in the American mind. An animated map of middle Europe with the Greater Reich, in black, surrounds the eastern edge of Czechoslovakia. The map of Germany morphs into a wolf’s head, its jaws open and ready to bite into its territorial prey. Once Austria is consumed by the Third Reich, plucky Czechoslovakia stands next in line for the Nazi predator. The citizens of Prague prepare for the worst, buying up gas masks and equipping baby carriages with bellows for ventilation. “Jew and Aryan fared alike among the babies,” notes the voice-over. “They had not yet heard of the Nazi racial laws.”

The external threat from the Third Reich is augmented by its fifth column, the SDP, the Sudeten Deutsch Party, lead by the nefarious Konrad Henlein. Like its model, the SDP is a cover for roving gangs of brownshirted thugs, pledged to racial superiority and devoted to Hitler. To soften the sinews of the Czech democracy, “the Nazi propaganda machine” spews tons of leaflets, posters, and pamphlets into the Sudetenland to spawn hatred and sedition.

Wanting only peace, ordinary Czechs reach out a hand of friendship to the Sudeten Germans, many of whom are anti-Nazi refugees from Germany and Austria. There is much to enjoy in a nation of such rich history and gorgeous scenery, where cathedrals and palaces dot the landscape, and the colorful folk (“Catholic, Protestant, Jew”) practice traditional arts and crafts and labor in industry and on the farm, abiding in harmony and toiling together for the common good.

Meanwhile, socialist trade unions give aid to anti-Nazi refugees and fight fascism with puppet shows and political theater. To the delight of a packed house, Czech comedians George Voskovec and Jan Werich, actor-playwrights for the Liberated Theater, perform a satirical anti-Nazi revue. The comedians also take the message to children at a trade union camp, singing patriotic Czech songs. (By the time Crisis was released, the duo had been forced to flee to New York, where they did publicity for the film.) Viewed from the vantage of 1939, all the bucolic scenes of peace-loving Czechs at work and play unfold as a poignant photo album of a nation-no-more. None of the scenes of indigenous Czech life—the speeches, the performances, and the songs—are subtitled, nor are the clips of Hitler’s rants, but the melodious determination of the Czechs and the angry growl of the Germans require no translation.

Tragically, the pastoral ideal is infested with serpents. On May 22, municipal elections take place amid SDP terror tactics, ballot stuffing, and voter intimidation. Hitler seems poised to pounce, but is deterred by a nationwide mobilization called by the Beneš government. As heroic Czechs (“calm and resolute”) rally to defend the frontier, the Nazis are temporarily blocked. However, the fifth column agitation continues unabated. When two Sudeten Germans are killed by Czech border guards, the SDP holds a grand funeral procession for the martyrs, replete with banners and torches. A wreath bearing the name of Adolf Hitler is solemnly laid in tribute. “No,” says the narrator, “this is not a scene from the Dark Ages. This is the Nazi way.”

A series of images from Herbert Kline’s pioneering anti-Nazi documentary Crisis (1939) (top to bottom): opening the book on Mein Kampf, illustrating the ravenous appetite of Nazi Germany, and showing the plight of refugee children.

A new wave of SDP-instigated violence roils the Sudetenland. The cameras miss the action, but not the aftermath: bloodstained sheets and victims battered by truncheons. Finally Beneš declares martial law and outlaws the SDP, closing down its offices and newspapers, but the forceful measures are too little, too late. The capitulation of France and England seals the fate of the democratic republic so unfortunate as to share a frontier with Germany. Desperate to avoid confrontation, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain scurries first to Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s lair, then to Bad Godesberg, and finally to Munich to sign the white piece of paper. “Betrayed and abandoned,” Czechoslovakia is invaded by the Reich.

"The human race itself is impoverished and humiliated by these events,” mourns the narrator. The outlook for the future is dim, what with men like Chamberlain in England and Daladier in France. We can only hope “that in other lands there may still be men who do not tremble and obey when Adolph Hitler cracks the whip.” Considering the political credentials of the production team behind Crisis, the reference is more likely to Stalin than FDR.

As the pages of Mein Kampf open again, a literal bookend on the tragic tale, the narrator speaks a final admonition, words underscored in script on the screen:

Remember: Peace and freedom and the right to live—they can be possible only in lands where men are determined that the swastika shall not be raised in triumph; that the pages of Mein Kampf shall never become supreme law.

Released by veteran foreign film importers Arthur Mayer and Joseph Burstyn, Crisis premiered on March 13, 1939, at the 55th Street Playhouse. The night before, Kline had gone on the WABC radio program We the People and predicted that Hitler would break the Munich Pact and take Prague—which he did on March 15.

Given the topic and pedigree, Crisis had an especially high profile in Popular Front circles—and an inside track to the innermost part of the circle with a special advance screening at the White House. “You must show this film everywhere in our country to help counter the ‘America Firsters’ propaganda calling me a warmonger!” FDR exclaimed, according to Kline.31 Better yet, Eleanor Roosevelt plugged the film in her nationally syndicated “My Day” column. “Perhaps the value of this picture for us is the mere realization of the difference which freedom backed by a sense of security gives in comparison with virtual dependency where security can no longer exist,” she wrote, a delicate way of rebuking England and France and cautioning America.32

The First Lady was not alone in her enthusiasm or ruminations. “Here’s a really excellent documentary film that should prove of great historical importance, for it contains phases of the world-stirring crisis that have not been caught by the newsreels,” wrote the Film Daily, alert to the time capsule endurance of the film. Yes, there was propaganda (“all on the side of the Czechs”) but “at least the camera cannot lie, and here are many scenes that will give the intelligent historical student a clearer grasp of many phases that may have escaped his attention, or which newspapers accounts have not covered.”33 Motion Picture Herald’s reviewer George Spires, who caught the film under optimal conditions, reported: “The picture, playing to a capacity anti-Nazi audience in New York, was applauded at the finish.”34 Daily Worker critic Henry Hart, who saw the film twice in the same venue, dwelled on the grief of those around him. “Sobbing could be heard in the darkness of the theatre as the betrayal of the brave, honorable and intelligent Czech people unfolds and, when the picture was over, tears could be seen in the eyes of men and women, young and old.”35

According to Kline, the best scene was not in the film: on the night of Hitler’s Nuremberg speech, in the town of Opaca, close to the convergence of the German, Czech, and Polish borders, Kline had been tipped to look for trouble. It came soon enough: a group of local Nazi sympathizers surrounded an old Jewish man peddling popcorn on the street corner. In response, a group of Czech youths formed a protective cordon around the old man. Before the Nazis could pounce, a lone Czech policeman defused the situation by lecturing the Nazis about the cowardice of the act. “That was one of the most significant indications I saw of the situation in Czechoslovakia before Munich,” Kline recalled. “It was, you might say, the sort of thing that could be easily staged in a studio. I saw it happen. And yet, I couldn’t get it in my camera because there was no light.”36

Yet the newsreels, the March of Time, and Kline’s Crisis shed enough light on the situation in Europe for viewers to see the writing on the wall. Though covered in fits and starts, often with footage filtered by the Nazis, the Anschluss and the Czechoslovakia crises gave Americans their first good look at Nazi aggression. However, a more terrible story was unreeling out of sight of the newsreel camera. “Munich was the highlight of 1938 and history,” Wear stated in his wrap-up of the year in newsreels, casually mentioning the runner-up. “Jewish persecution scenes, ranked by most newsreel editors as next in importance in foreign affairs, were terrifically ticklish and hard to handle.”37

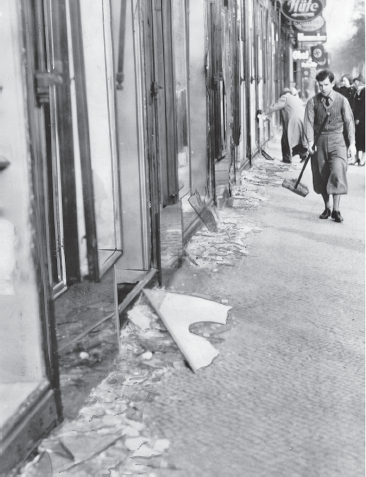

When the news first flashed over the radio airwaves late in the evening of November 9–10, 1938, the German word Kristallnacht had not yet entered the American lexicon. Literally meaning “crystal night,” a glib term coined by the brownshirted perpetrators, but now translated as “the night of broken glass,” it marks a solemn day of remembrance. The compound noun is an oddly poetic metaphor for the shattering of property, bones, and illusions—a thunderclap moment that made it clear as crystal that the Nazi campaign against the Jews was no off-the-cuff rampage but the orchestration of state policy.

For American journalism also, Kristallnacht marked an epiphany. Jolted awake to the full frenzy of the Nazi pathology against the Jews, newspapers headlined the story, radio flashed bulletins, and editorials condemned the persecutions.38 Even the newsreels woke up and harkened to the racket. Heretofore, shut out from coverage of Nazi depredations and “terrifically ticklish” about broaching the topic of antisemitism, they had mainly looked the other way.

The match that lit the firestorm was the shooting of the third secretary of the German embassy in Paris, an official with the too-perfect name of Ernst vom Rath, by Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old Polish Jew driven to derangement by his stateless status. When vom Rath succumbed to his wounds at 4:25 p.m. on November 9, the Gestapo sent out secret orders for an orgy of destruction that smashed property and spilled blood in virtually every German and Austrian town with a visible Jewish presence. Joseph Goebbels later claimed that the pogrom was a spontaneous outburst of righteous anger from the German volk, a “justifiable and understandable” manifestation of Aryan vengeance against Jewish perfidy, but a lengthy paper trail attests to the calculation behind the anarchy in the streets—which is not to say sundry acts of vandalism, brutality, and murder were not improvised on the spot.39

In America the next morning, front-page headlines were already attuned to the sonic atmospherics. “The noise of breaking glass and cracking furniture accompanied loud anti-Jewish jeers,” read the first report from the Associated Press. “When the smashing crew had passed, it looked like a tornado had swept the street. The pavement was covered with broken glass.” Otto D. Tolischus, the Berlin correspondent for the New York Times, was also an earwitness to “the shattering of shop windows falling to the pavement, the dull thuds of furniture and fittings being pounded to pieces and the clamor of fire brigades rushing to burning shops and synagogues.”40

Kristallnacht, November 9–10, 1938: the aftermath of “the night of broken glass” in Berlin, captured in a wire service photograph but not by the American newsreels.

Unfortunately, the most sound-sensitive of the media was well out of hearing range. During Kristallnacht, CBS’s European bureau chief Edward R. Murrow happened to be stateside and Berlin correspondent William L. Shirer, heartsick from the fallout from the Munich Pact, had retreated first to Geneva and then to Warsaw. He makes no mention of Kristallnacht in his diary or memoirs. However, NBC’s Max Jordan was on the scene in Berlin, “when the antisemitic frenzy reach[ed] its climax,” he recalled in his 1944 memoir. Going outside his hotel, he first came across the smoldering ruins of a synagogue and then a fashionable street of Jewish-owned shops where “every single show window had been smashed.” He too mentions no direct live broadcast to America.41 Like all centers of mass communication, the Berlin shortwave transmitter used by the American networks was controlled by Goebbels’ Reich Ministry and the copy of radio correspondents was strictly censored prior to broadcast. Even had either correspondent been near an open microphone, the street-level reality would not have gone out over the air.

Radio journalists attempted to conjure the sounds of terror with words. By the next afternoon in America, the news was being read out from wire reports by breathless announcers on NBC’s Blue Network:

This has been a day of terror for the Jews in Germany. All over Hitler’s country, Nazi mobs have been beating Jews, wrecking their shops and homes, burning and dynamiting synagogues. It was the worse anti-Jewish outbreak since Hitler came to power. … After fourteen hours of violence, propaganda minister Goebbels has finally called a halt, but Goebbels condoned the attacks. … Thousands [of Jews] have been arrested, and in Vienna, twenty-five committed suicide.42

Regular updates were reported on the hour.

Yet perhaps the din of Kristallnacht came most powerfully into American homes not from stateside announcers reading out wire copy, but from editorial commentary, a relatively new practice. Across the airwaves, commentators raised their voices in full-throated denunciations of the Nazi rampage. “The rage of antisemitic terror in Germany was as good as ordered by the Hitler government,” declared NBC’s Lowell Thomas. “It’s all a deliberate policy, a calculated stroke of terror.” On WMCA, former New York governor Al Smith and New York district attorney Thomas E. Dewey condemned the Nazis on a one-hour program later rebroadcast due to popular demand. On WNEW, commentator Richard Brooks recited Marc Antony’s funeral oration from Julius Caesar with Hitler’s name substituted for Brutus’.43 The radio chorus was blunt, loud, and, with one acid-tongued exception, unanimous.

On November 20, the demagogic radio priest Father Charles E. Coughlin devoted his regular Sunday homily to preaching a familiar set of Nazi canards about the Jews—that the Jews were the agents of Bolshevism, that the Jews caused Germany to lose the Great War, and that the Jews undermined Christian America. Though Coughlin had previously said as much or worse, this time his screed unleashed a flood of protests. In New York, WMCA took the unusual step of breaking in after Coughlin’s talk to inform listeners that the priest had made errors of fact. The station later announced it would “not permit a repetition” of Coughlin’s antisemitic incitements.44

Antisemitism over the American airwaves: radio priest Father Charles E. Coughlin, broadcasting from station WJR in Detroit, Michigan, in 1935.

However vividly Kristallnacht might be rendered in print and on radio, Americans could neither hear the racket nor see the fires in the newsreels. No newsreel footage of the rampage exists and no newsreel cameraman, American or German, risked his neck for the scoop. An amateur shutterbug seems to have been the only exception.d A Los Angeles doctor visiting Berlin was reported to have attempted to take motion pictures of smashed shop windows in the city. He was promptly taken into custody and his film confiscated by the Nazis.45

Of course, the absence of motion picture verification hardly constituted a mediawide news blackout. The persecution of the Jews under the Nazis in the 1930s was widely known and thoroughly chronicled. Antisemitism was a core tenet of Nazi doctrine, shouted by Hitler at the top of his lungs, trumpeted by Goebbels’ propaganda, and visible to any tourist wandering the streets of the Greater Reich. But while news reports and firsthand accounts testified to the systematic discrimination and random violence, motion picture footage documenting the terror was sparse.

Only a few glimpses broke through the Nazi fog. During the brief window of opportunity in early 1933, the literal signs of antisemitism appeared in newsreel coverage of the boycott of Jewish-owned businesses on April 1, 1933. Footage of the Berlin boycott arrived on New York screens precisely two weeks later on April 14, 1933.46 The clips offered glimpses of scuffling brownshirts, a skull and crossbones with the word “Juden” scrawled above it, storefront placards ordering Germans not to buy from Jews, and signs prohibiting Jews from public accommodations. The select montage of images comprised a core cache of reusable material that was replayed as “library stock” for the rest of the decade. Freeze-framed, the crude sign of the “Juden”-tagged skull and crossbones served as a potent symbol of the poison of antisemitism flowing through the Third Reich.

The only supplement to the newsreels that year was an obscure independent film. Released in April 1933, a 17-minute short entitled Hitler and Germany can claim pride of place as the first English-language anti-Nazi documentary. It was produced by the New York–based Film Forum, a self-styled “private society for the discussion and encouragement of unusual motion pictures,” a phrase that translated as cadres of left-wing cinephiles sponsoring screenings of Soviet cinema at the New School for Social Research.47 Modeled on similar groups in Europe, the outfit was bankrolled and presided over by Broadway dramatist Sidney Howard.

A filmed symposium rather than an archival documentary, Hitler and Germany recorded a roundtable discussion moderated by Amos Pinchot, an eccentric pacifist-progressive reformer. Pinchot posed questions to a series of notable anti-Nazis and asked each in turn their impressions of the new regime. First to speak was Edward Dahlberg, the American Jewish novelist, just back from Germany, where he told of being attacked on the streets. Dahlberg was followed by Norman Thomas, the prominent socialist and perennial presidential candidate; Clarence Hathaway, a communist stalwart who edited the Daily Worker; Peretz Hirschbein, the Russian-born Yiddish-language playwright; Ella Winter, the wife of journalist Lincoln Steffens and secretary of the American Committee Against Fascist Oppression in Germany;e and historian Hendrik Willem van Loon, who opined that in a couple of years no one would remember Hitler’s name.

Sold as a short subject and recommended only for limited bookings in Jewish or Catholic neighborhoods, Hitler and Germany was less a symposium than a one-sided fusillade. “Maybe they couldn’t find anyone to take the German butcher’s side,” figured Wolfe Kaufman.48 The Film Daily worded its review carefully: “Their speeches as a whole represent a protest against the alleged Hitlerite terrorism.”49 At the Cameo, the short played on a bill with Slatan Dudow’s Weimer-era communist paean Whither Germany? (1932) and then vanished.

After the first part of 1933, the solidification of Nazi control meant that independent motion picture coverage of Nazi Germany by the American newsreels, and especially of the antisemitic outrages, was virtually impossible to obtain. During the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, when the newsreels were given somewhat freer rein, at least beyond Leni Riefenstahl’s field of vision, the Nazis stored the antisemitic signage away for the duration so as not to distress the tourists. Print reporters commented on the conspicuous absence but the newsreel camera could not show what was not there. A rare shot of the Nazi wallpaper was captured in 1937 by Julien Bryan who, though closely supervised by his Nazi handlers, managed to sneak a shot of antisemitic signage on park benches for the March of Time’s “Inside Nazi Germany” episode of January 1938.

The minimal time the newsreels allotted to coverage of antisemitic incidents in Germany may have been understandable given the medium’s utter dependence on footage. Less understandable was the minimal time allotted anti-Nazi protests by Jews in America. Only occasionally did the newsreels cover an anti-Nazi protest organized by Jewish groups. Two factors increased the odds for recognition: if the rally were large enough and in close proximity to newsreel headquarters in New York. On March 27, 1933, a huge anti-Nazi rally was held in Madison Square Garden, in coordination with dozens of similar rallies staged nationwide. To an overflow crowd of 20,000—with 35,000 more clogging the streets outside the Garden—former New York governor Al Smith told the cheering throngs he would oppose the bigotry of the Nazis with the same zeal he opposed the Ku Klux Klan. “And it don’t make any difference to me whether it is a brownshirt or a nightshirt,” he cracked in his gruff New Yorkese.50 Despite the dramatic images and nationwide significance of the event (nearly one million Jews and their allies participated in anti-Nazi rallies that day), the newsreels mustered little interest in the impressive outpouring of domestic anti-Nazi sentiment. “Luxer was the only house Saturday afternoon to screen the Garden mass meeting in protest of Hitler,” Tom Waller noted that weekend, crediting the sole clip to Paramount News. Also on the program at the Trans-Lux that afternoon were segments on a blind man building a house, a one-armed golfer swinging on the green, and a champion pretzel bender. Footage of slugger Babe Ruth signing his new contract with the New York Yankees was given lavish treatment by all the reels.51

Those kind of priorities put the newsreels at odds with their prestigious rival in screen journalism. In 1935 the March of Time lambasted the newsreels for the timidity of their coverage of Nazism in general and Nazi persecutions of the Jews in particular. Truman Tally, producer of Fox Movietone News, the newsreel with the best field operation in Germany, admitted the screen magazine had a point but insisted such self-censorship was all in the past. “Of course, there was a time when the reels ‘laid off’ Hitler to some extent,” he explained, attributing the hiatus to a desire not to unduly upset audiences discomforted by reports of Jewish persecutions. Motion Picture Herald elaborated:

It was indicated by all managers of newsreel companies that there had been occasional protests on the part of Jewish motion picture exhibitors “whose feelings were hurt,” but with one exception the newsreels appear to be of the opinion that what the exhibitor chooses to delete under such circumstances is no concern of anyone but the exhibitor himself.52

Between the lines of the double-talk, the newsreels were saying that neither audiences nor exhibitors much cared to be shown news of antisemitic terror in Germany. Moviegoing folks, Jew and non-Jew alike, were out for a nice night on the town, and preferred to be walled off from the ugly happenings of the outside world. Thus, even when the newsreels broached the subject of Nazi persecutions, usually with a report on a stateside protest against Nazism, exhibitors often cut the clip to avoid an in-house disturbance or an unpleasant aftertaste that might sour enjoyment of the featured attraction. The same rule applied to coverage of pro-Nazi demonstrations. In April 1939 the German American Bund mounted a massive pro-Nazi rally in Madison Square Garden, which the newsreels dutifully covered. In New York, theater after theater reported disturbances from incensed moviegoers. The newsreels quickly eliminated the Bund clips from the issue.53

Characteristically, the March of Time took a more aggressive and plain-spoken stance toward the antisemitism at the heart of Nazi doctrine. The first segment in its seventh issue, released October 1935, reviewed the history of the British protectorate of Palestine and British efforts to colonize the promised land with Jews. “A topic off the beaten trail,” noted Variety. More offbeat was the reason, besides Zionist zeal, that 50,000 Jews were fleeing Europe. “Shots of Hitler on the soapbox, and of mobs of Nazis making raids on Jewish homes, shops, offices, stores, [are] highly dramatic and, of course, controversial,” continued the review, observing, by way of contrast with the newsreels, that the March of Time “thrives on controversial items” even though “Nazi elements may yelp at the unflattering picturization.”54 Boasting that “764 Rabbis and 23 Jewish organizations [were] cooperating on the Palestine episode,” the publicity for the issue left no doubt about the screen magazine’s sympathies—or its target audience.55

In “Poland and War” (June 1937), the March of Time shows scenes of antisemitic violence in Poland (reenacted), incubated by the antisemitic newspapers (real) of “the club-footed chief of Hitler’s propaganda machine,” Dr. Joseph Goebbels. “In ghettos, for the first time in many years, pogroms are breaking out,” reports narrator Westbrook Van Voorhis, reverting to the house syntax for the indictment: “In the repeated attacks on Jews are seen the workings of Hitler’s machine.” Variety noticed the bluntness and approved: “The March of Time by its offscreen narration blames Hitler and his propaganda machine for the horrifying pogroms upon Jews in Poland.”56

Though “Inside Nazi Germany,” the March of Time’s most famous episode of the 1930s, condemned “Hitler’s relentless campaign against the Jews” in its commentary and underscored the point in publicity material that emphasized “the sequestration of the Jews, banned by state edict from professions and business,” such outspokenness remained exceptional.57 A few weeks before Kristallnacht, the Chicago Board of Censors snipped scenes of Jewish persecutions from a lecture and screening by Julien Bryan, the cameraman whose exclusive photography in Nazi Germany was the episode’s main selling point.58

After Kristallnacht, however, even the Chicago censors lost the habit of kowtowing to a nominally friendly foreign power. Emboldened by the new atmospherics and abashed by the criticism in the print press, the newsreels seized the moment and unloaded on the Nazis—as best they could given the limitations. “Reflecting the most urgent topic of the week, the current bill at the Embassy stresses the outbreak of anti-Semitic terrorism in Germany,” reported Variety, the conscientious monitor of the newsreel bill. “But since no pictures of the violence are available (there wouldn’t have been time enough to get them here even if Nazi censorship permitted the scenes to be filmed), the newsreels have had to treat the subject from this end.” That is, lacking footage of the actual pogrom, newsreel editors recruited politicians and religious leaders for on-camera condemnations, a lineup of luminaries that included former president Herbert Hoover, former New York governor Al Smith, and former Republican presidential candidate Alf Landon.59 “American public opinion is aroused!” proclaimed Lowell Thomas, the voice of Fox Movietone, introducing remarks by Hoover: “The only living ex-president expresses the official attitude that Nazi violence is both anti-Semitic and anti-Christian.”

Goaded at last into action but still strait-jacketed by lack of access, newsreel editors organized to address the problem. On the morning of November 18, 1938, in a hastily arranged huddle at in the New York offices of the MPPDA, representatives from Fox Movietone News, News of the Day, Paramount News, RKO-Pathé, and Universal Newsreel met to pool resources and discuss strategies. According to leaked reports, the purpose of the confab was “to formulate plans for a concerted presentation by each of the reels of the current persecution in Nazi Germany.” On the table was a plan for all five companies to cooperate on the production of a special issue to be released first to theaters around the nation and then circulated free of charge to “churches, schools, labor organizations and other outlets.”

Faced with the usual brick wall, the well-intentioned venture came to naught. “An insurmountable barrier existed to bar the plans, namely the dearth of film footage available to make a vigorous presentation to the public,” lamented the Film Daily, which gave a succinct summation of the paucity of imagination and access that had bedeviled the newsreels since 1933 in covering the Nazi war against the Jews:

Prior to the present persecutions in Germany, the newsreel companies, with the exception of the March of Time, which is not strictly in that category, were slow in anticipating the situation which has now developed. Additionally, the Nazi Government has made the taking of authentic scenes of oppression virtually impossible to obtain.60

Though Kristallnacht lacked a visceral representation in the newsreel medium, it left a profound impact on the Popular Front. A stepped-up campaign of anti-Nazi activism from within the ranks of the motion picture industry helped fill the vacuum in screen coverage. Locked out from on-location coverage, unable to crack the Hollywood feature film, artist-activists responded to the rising tide of antisemitic violence in the greater Reich with a concurrent surge of political action.

On November 18, 1938, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League mounted a massive “Quarantine Hitler” rally at Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles. In between impassioned speeches from actor John Garfield and director Frank Capra, a crowd of 3,500 motion picture industry personnel unanimously voted to send a telegram, signed by dozens of prominent Hollywood personalities, to President Roosevelt. “The Nazi outrages against Jews and Catholics have shocked the world,” read the plea to FDR. “Coming on the heels of the Munich pact, they prove that capitulation to Hitler means barbarism and terror. … We in Hollywood urge you to use your presidential authority to express further the horror and the indignation of the American people.”

Chester Bahn, editor of the Film Daily, had also had enough. In a boxed-off front-page notice, he announced a new policy for the New York–based trade paper:

Effective today [November 21, 1938], The Film Daily announces the discontinuance of its long-established Berlin Bureau.

The reason for this decision to withdraw from normal press relations with Nazi Germany should be obvious.

When and if a responsible German Government takes over, re-establishment of the Berlin Bureau will receive careful consideration.61

Throughout Hollywood, Kristallnacht spurred a militant anti-Nazi fervor that spread beyond the already energized anti-Nazi core. “This very welcome change of attitude on the part of a few tycoons was unquestionably traceable to news of the most recent Nazi persecutive outrages,” reported Ivan Spear in Box Office, though he complained that many in Hollywood’s executive ranks still balked at cooperation “with the groups that have been carrying on the valiant fight against the spread of totalitarian doctrines and policies in America.”62 It was into this charged atmosphere that Leni Riefenstahl walked during her ill-fated visit to Hollywood. The town was primed to vent its pent-up fury at the nearest incarnation of the Nazi regime.

However, the most enduring response to Kristallnacht was not a newsreel, a rally, or a telegram, but a song. For the evening of November 10, 1938, just as the wave of antisemitic violence in Berlin was subsiding, the singer Kate Smith had long planned to dedicate her variety show program to the twentieth anniversary of Armistice Day, a solemn look back at the last war as the world stood on the brink of another. She asked her friend, the composer Irving Berlin, for a patriotic anthem suitable for the occasion. Rummaging through his old sheet music, Berlin resurrected a patriotic song originally written for but cut from his Great War musical Yip Yip Yiphank!63 The tune was “God Bless America.” Smith belted it with a passion that electrified listeners. An instant sensation, the castoff composition by the Jewish American composer with the Germanic surname became Smith’s signature song and America’s unofficial national anthem.

Given the terrifying news from overseas, little wonder Americans sought patriotic expression with song-prayers of thanksgiving for their own blessings. By early 1939 the spread of Nazi hegemony, the brutal antisemitic outbreaks, and the plight of pathetic refugees trudging across Central Europe dominated the news of the day across the media, newsreels not excluded. In response, and with no official prompting, the motion picture industry began to play the National Anthem as an integral part of the balanced program: a few big palaces with orchestras played it live; most venues unspooled a Technicolor short featuring a chorus singing over patriotic imagery.64 When juxtaposed against the nightmarish images from Europe, the contrast could be inspirational. “The showing of [the March of Time’s “The Refugee—Today and Tomorrow” (December 1938)] is brought to a rousing pitch by following it immediately with a Technicolor trailer of the Stars and Stripes blowing in the breeze and a recorded choral group giving way to the ‘Star Spangled Banner,’” reported a Variety reporter at the Embassy Theater. “The audience quickly got to its feet and joined the soundtrack choristers in the anthem’s several verses.”

Woe to the moviegoer who did not show proper deference. “A few men in the audience, who continued to wear their hats during the rendition, discovered they were in the United States,” growled Mike Wear, meaning that the ill-mannered clods were barked at to remove their headgear.65 No one dared to remain seated.