Dancer, athlete, actress, filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl was the Valkyrie goddess of Third Reich cinema, the lone shimmering star in a constellation of dim hacks. Murnau preferred Camilla Horn for the doomed Gretchen in Faust (1926), Lang tapped Brigitte Helm for the metallic siren in Metropolis (1927), and von Sternberg anointed Marlene Dietrich as The Blue Angel (1929), but an impresario of greater magnitude gave the perennial understudy the role of her lifetime in the director’s chair. An authentic genius of the moving image, as graceful with the camera as her body, she choreographed two Nazi pageants that will live as long as images fill motion picture screens, Triumph of the Will (1935), a Wagnerian paean to the 1934 Nazi Party rally at Nuremberg, and Olympia (1938), a magisterial two-part chronicle of the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Alone of the artists and architects who sculpted idols and built monuments to the Third Reich, she realized her vision in a medium sturdy enough to withstand saturation Allied bombing.

Riefenstahl’s life is the stuff of legend, mainly her own. Sifting the facts from the fabrications has proven a nettlesome task for her biographers, but even stripped of her lies the story is remarkable enough.1

Born in 1902 in comfortable circumstances in the otherwise working-class district of Wedding on the outskirts of Berlin, she vaulted from her humble origins as a day player at Ufa (unbilled and undraped she appeared in the sexploitation sensation Ways to Strength and Beauty [1925] ) and into the Weimar spotlight as a nimble dancer flouncing in the diaphanous style of Isadora Duncan. Given star billing on Max Reinhardt’s stage, she learned to land on her feet, a skill she never lost. In 1925 she got her 8 by 10 glossy into the hands of director Arnold Fanck. Mesmerized by the portrait, he became her first motion picture mentor.

Fanck was a specialist in, virtually the originator of, the “mountain film,” an Ur-German genre played out amid craggy Alpine landscapes, treacherous glaciers, and thundering avalanches. Utterly fearless, game for anything, Riefenstahl mastered the slippery topography, turning herself into an expert mountaineer and skier while risking frostbite and her neck in service to Fanck’s snowblind vision. In on-location escapades such as The Holy Mountain (1926) and the international hit The White Hell of Pitz Palu (1929), she played the snow angel to his ice sculptor.

With her knack for timing and networking, Riefenstahl happened to be present at two key cinematic events of the Weimar era. In 1926, at the Berlin premiere of Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, she joined the crowds who sat spellbound before the kinetic vitality of a revolution in filmmaking. Liberated from the gliding camera and painterly set design of the Ufa aesthetic, directors rushed to mimic the Russian’s pulsating rhythms and whiplash montage. Three years later, Riefenstahl attended the riotous premiere of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), where she caught her first glimpse of a frothing Joseph Goebbels spitting invective at the screen.2

No longer content to let Fanck call the shots—or to bury her in avalanches—Riefenstahl achieved the unthinkable by securing financing to direct and star in her own film. The Blue Light (1932) was a Fanck-like high-altitude melodrama about a gypsy girl so in touch with nature, so in tune with the aurora borealis, that the local peasants think she practices witchcraft. Stateside critics marveled at the career change. “Miss Riefenstahl authored and sponsored the production herself,” a surprised Film Daily noticed, praising her “splendid performance” as the bewitching gypsy.3 Perhaps, had a Hollywood mogul spotted her star potential and made the right offer, she might have resumed her screen rivalry with Marlene Dietrich at Paramount or, though sheer force of will, broken into the exclusive boys’ club of studio directors with Dorothy Arzner.

Riefenstahl’s swan song performance as clay in another director’s hands was in Universal’s S.O.S. Iceberg (1933), an on-location spectacular codirected by Hollywood’s Tay Garnett and Ufa’s Fanck, the last of the big-budget German-American coproductions born of the Weimar era. Garnett handled the melodrama; Fanck the landscapes. Shot in death-defying conditions in Greenland, the subzero action-adventure film built a rescue narrative around astonishing footage of ice calving off the Rink Glacier. Riefenstahl played a tangential character, the aviatrix wife of an Arctic explorer whose research team is cast adrift on an iceberg. The stranded explorers are rescued by the Great War hero Maj. Ernst Udet, famed German air ace, playing himself.

Riefenstahl was soon to be tapped for a bigger part in film history. The story was that Hitler, smitten by her sunlit dance on the beach in The Holy Mountain, plucked her from the crowd to channel his cinematic ambitions, much the way Albert Speer gave expression to Hitler’s monumental architectural schemes. As a regular guest at Nazi social functions, she dined with the Nazi power elite and sipped after-dinner drinks before screenings of forbidden Hollywood films. Despite the celibate lifestyle attributed to the host, rumors of a romantic liaison between Hitler and Riefenstahl were whispered in Reich Ministry halls and blared in stateside headlines, though by most accounts, and not just her own, the devil’s bargain was never consummated, at least not physically. Whatever the exact nature of the attraction, she enjoyed privileged access to the executive in charge of production—very much to the consternation of his jealous male entourage.

Goebbels resented her direct line to Hitler, and, if Riefenstahl is to be believed, her rejection of his sexual overtures, but the propaganda minister was also infuriated by the dismal quality of Nazi cinema. In 1933 he banned the static Horst Wessel (1933), a hagio-biopic about the martyred Nazi storm trooper, for “artistic inadequacy,” an embarrassment that “neither does justice to the personality of Horst Wessel, reducing his heroic figure through inadequate presentation, nor to the National-Socialist movement which is today bearer of the State.”4 Despite the full backing of the Nazi machine, the Reichsfilmkammer failed to produce a single film with the cross-border appeal of a program filler from Warner Bros. Not blind to her talent, Goebbels suppressed his bureaucratic jealousy and gender bias. Without Riefenstahl, he had precious little to crow about.

In September 1933, Riefenstahl undertook a kind of audition film for the Third Reich, a documentary short of the Nazi Party Congress at Nuremberg entitled Victory of Faith (1933), a work afterwards disavowed by the director on aesthetic rather than moral grounds. A year later, during the Sixth Party Congress at Nuremberg, she was given the ranking authority and mammoth resources to construct a 35mm edifice to the Nazi ethos. Presiding over acres of territory and an obedient cast of thousands, she called the shots for a cinematic spectacle beyond even the means of a D. W. Griffith or Cecil B. DeMille.

The result—the awe-inspiring Triumph of the Will—proved that the girl director had morphed into a major artist. Often called a documentary, it is more akin to a concert film, recording a showstopping extravaganza staged for the cameras. Yet the Nazi Party Congress of 1934 was no pseudo-event: something real was happening. Columns of robotic troops planted in geometric patterns, tongues of flame illuminating nighttime parades, and blond youths with clear eyes and taut sinews swirl by in a rapturous revue. Above it all—literally so in the film’s devious overture, where the airborne leader swoops down like an eagle from the heavens—is the divine figure of the führer, lord ruler of the Nazi universe. All else are mere mortals, extras in his star vehicle.

Unlike the Party Congress at Nuremberg, Triumph of the Will was not a metronomic goose step but a sensuous ballet, the tempo of the editing a free-form dance recital. True to her roots, Riefenstahl orchestrated a pageant of pulsating, syncopated movement, vibrant and reverent, festive and purposeful. “Pic is an overgrown newsreel abounding in marching brownshirts, flags, and speeches by Nazi leaders,” sneered Variety, noting that it tanked even in Berlin.5 The most important patrons were well satisfied, however. For her cinematic service, Goebbels presented her with the Adolf Hitler prize for Best Picture from 1934.

So vivid in the memory of Nazism today—few archival flashbacks to the Third Reich can resist lifting a clip from Triumph of the Will—Riefenstahl’s epic was known mainly by reputation and rumor in America in the 1930s. Glimpses of her work flashed by in the American newsreels, without attribution, seemingly snuck in by editors incapable of resisting the allure of the imagery. “Although it is far down in the program, one of the most interesting clips on the show is that of a Hitler rally,” observed Variety’s Roy Chartier from a seat at the Embassy Newsreel Theater. “Because of the news importance of the Nazi leader and what’s happening overseas, this contribution, rather long, should have been up front. Unless, of course, newsreel people want to play down the significance and importance of such material as this, which bearing on Hitler and Nazism, brought scattered applause and sibilation [hisses] Saturday afternoon [October 13, 1934].” Chartier was dumbstruck by the fusion of grand spectacle and cinematic dexterity: “The Hitler celebration, attended by 700,000 farmers, does not credit the reel maker which supplies it, nor is there any offscreen narration for explanatory remarks. Sound cameras were on the job, screening the rally in detail and efficiently, with a brief speech by Hitler included. The very impressive page from Hitler activity was just ahead of two shorts, which close the show, and may have been placed there with thought of burying it rather than calling greater attention by spotting up [the Nazi clip] near the lead items.”6

Leni Riefenstahl ascendant: the Nazi auteur filming a soaring vertical shot at the Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg in 1934 for Triumph of the Will (1935). (Courtesy Corbis Images)

As a titled motion picture, however, Triumph of the Will floated under the radar of most Americans in the 1930s—at least most English-speaking Americans. A couple of prints circulated stateside in members-only screenings sponsored by the German American Bund and, in 1939, at least one theatrical screening broke out of the underground circuit. “There’s a Nazi controlled theater in New York (96th Street and 3rd Avenue),” revealed Irving Hoffman, the New York–based correspondent for the Hollywood Reporter, not deigning to name the 96th Street Theatre, formerly the notorious Yorkville Theatre, “which is a clearing house for German propaganda films that are considered too hot to handle by other Yorkville movie houses.” The “hatred-mongering and rabid paean to Nazidom,” said Hoffman, “has been kept pretty much of a secret.” Word of mouth—in German—whispered news of the film.a “Attendance has largely been drawn through the German newspapers and mailing lists of German-American organizations. An announcement on the screen at the conclusion of the picture requests that the audience help spread the picture’s ‘message’ of hate and intolerance by sending others to see it.”7

The first reference to Triumph of the Will in the Hollywood trade press came in March 1935 from an unnamed and by then surely non-Jewish stringer for Variety in Berlin. “Called Triumph des Willens (“Triumph of the Will”), production and cutting were directed by Leni Riefenstahl acting under party leaders’ orders. Miss Riefenstahl ordinarily is known as a film star.”8

Not any longer. Triumph of the Will catapulted Riefenstahl onto the international stage as a creative force to be reckoned with in world cinema. It has been said that there are only two characters in Triumph of the Will—Hitler and the masses, der Führer and das Volk—but the third is the controlling intelligence behind every shot, the auteur, Riefenstahl. Set beside Triumph of the Will, wrote the unwillingly awed Carl Dreher, the Austrian-born sound engineer moonlighting as the house expert on Nazi cinema for New Theatre and Film, “all other heroic Nazi movies appear dwarfed.”9

Dreher spoke too soon. In the annals of heroic Nazi movies, Riefenstahl’s next venture dwarfed even Triumph of the Will. The 1936 Olympic Games, held in Berlin from August 1–16, 1936, promised to possess more crossover appeal than a rally for Nazi fanatics. Awarded in 1931 to the soon-to-be-defunct Weimar Republic, the games were to be a media-friendly global showcase for the athletic prowess of a revitalized nation under Nazi rule. The motion picture medium and Riefenstahl were slated to play key roles in fusing the ideal Greek body type to the flesh-and-blood warriors of Nazi myth. “Who else but you could make a film of the Olympics?” Hitler asked her, presumably not rhetorically. Appointed to do for sports what she had done for the party, she was given a free hand to compete for a gold medal in her own event.

The conferring of so singular an honor on a woman, whose gender was ordinarily consigned to children, church, and kitchen in Nazi ideology, fascinated onlookers beyond the Reich. Even before the wire service reporters, radio correspondents, and newsreel cameramen descended on Berlin to cover the sports story of the decade, the American press corps doted on the sidebar story of the red-haired fräulein in command of so much manpower and equipment. In February 1936 a leggy picture of the actress-director on skies in a bathing suit, climbing upward, graced the cover of Time magazine—athlete, artist, and pinup girlb in the same package.10

Unable to imagine a purely professional relationship between the director and the dictator, the press spun outré speculations about the odd couple—he an ascetic vegetarian, she an outdoorsy epicurean. Riefenstahl was tagged with cutesy nicknames by snarky headline writers: “Hitler’s honey,” the “fuehrer’s fraulein,” “the czarina of Nazi movieland,” and so on. In a sea of drab brownshirts, the splashy redhead made great copy.

Riefenstahl also made enemies, especially among the newsreel cameramen and still photographers assigned to cover the Berlin Olympics. “Miss Leni Riefenstahl, [Hitler’s] actress friend, is controlling coverage of the Olympic Games,” groused Motion Picture Herald. “All else is streng verboten.” National pride mixed with sexist resentment at the girl who dared to invade the all-male preserves and lord her authority over the newsreel boys. If a photographer were caught trespassing, a Riefenstahl flunky handed him a pink slip that read: “Remove yourself immediately from where you are now—Riefenstahl.”11 Forced to sign contracts that limited the amount of footage shot and required to provide a duplicate print to Riefenstahl, newsreel editors deeply resented her appropriation of American footage that later wound up in Olympia.

In 1937, as Riefenstahl crouched over an editing board to shape miles of raw footage into a coherent whole, the scent of racial scandal heated up the media obsession with Hitler’s tabloid-ordained girlfriend. United Press reported the sensational news that Riefenstahl had been bounced from Hitler’s inner circle for an unconscionable transgression: she was Jewish. Goebbels issued a non-denial denial (the report, he said, was “too silly to be denied”) and pointed out that a certificate attesting to Riefenstahl’s Aryan bloodline was on file at the Reichsfilmkammer.

In America, the Jewish angle only whetted the media appetite for Riefenstahl gossip. “Is Hitler in Love with a Jewess?” teased Liberty magazine in July 1938, answering in the affirmative. “The whole story of the curious romance that has blossomed between the Jew-hating Fuehrer and the beautiful Leni Riefenstahl” was revealed by Princess Catherine Radziwill, Liberty’s aristocratic European correspondent, who claimed to have the inside dope on l’amour fou. “When [Hitler] saw Leni Riefenstahl, something else moved his heart and appealed to his intelligence,” confided a breathless Radziwill. Risking all, a heartsick Riefenstahl confessed her Jewess-ness to the lovestruck Hitler, who then gushed, “What does it matter who or what you are since I love you!” Later, when Hitler presents Olympia with his Best Picture accolade, he melts, “kissing the hands of Leni Riefenstahl, and murmuring as he did so, ‘I love you—oh, how, I love you!’”12

After two years of postproduction work—a marathon editing session compressing 1,500,000 feet of footage into four hours broken into two parts, “Festival of the Nations” and “Festival of Beauty”—Riefenstahl unveiled her magnum opus.

The Nazi ethos proved disturbingly congenial to the Olympic ideal. Like Nazism itself, Olympia harkens back to a golden age when immortals walked the earth. Materializing through the mists of time, sculpted in white marble, Greek statues dissolve into buff Aryans, nude bodies-beautiful without blemish or deformity, hurling javelins, discus, and shot-puts, straining to embody the Platonic-Aryan idea. If the god presiding over the festival in Triumph of the Will is Hitler, the god of Olympia is Apollo—the athletes are solar-powered deities, muscular perfection in motion, a Greek pantheon come to life as Nazi supermen. The nude female athlete, arms outstretched to the sun, is Riefenstahl.

For the athletic events—track and field, swimming, the marathon—Riefenstahl adapted her perspective and pace to fit the competition—close to the ground and up close for track and field; in the air and free-floating for the pole vaulters and divers; and trudging along at feet-, thigh-, and midsection-level for the long-distance marathoners. Putting Soviet aesthetics in service to Nazi ideology, the editing liberates the athletes from gravity itself, especially in the water sports. Flipping and flying in slow motion and reverse projection, the high divers soar with ecstatic buoyancy, lighter than air. Whatever the event, the contest between the genders is unequal: Riefenstahl’s camera caresses the male form, doting on biceps and torsos, muscles stretched tight and blood coursing through veins, seeming to lap up every drop of perspiration.

That Riefenstahl had created a long-form masterpiece was obvious to anyone with eyes. “She has turned out a convincing, exciting, and dramatic record,” Variety grudgingly conceded.13 The best certification of her bona fides came from Hitler himself, who in May 1938 personally presented her his award for “the best motion picture achievement of 1937.”14 At the premiere in Paris, the French surrendered unconditionally. “Olympia is more and better than a film,” wrote a dazzled cinephile. “It is a glowing poem of images, light and life; it is ageless and almost without nationality.”15

That August, at the Venice International Film Exposition, where the fix was in, Olympia won the Mussolini Cup, the plum prize, beating out Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the crowd favorite. Charging “politics,” poor sports in America decried the upset as “an Italian effort to please Germany.” Harold Smith, European representative for the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, argued that a documentary, not being a legitimate feature film, should not have even been in competition. How else to explain how “an obscure German documentary film” had beaten out the fairy-tale magic of Walt Disney?16

Having conquered Germany, France, and Italy, Riefenstahl turned naturally to the nation that ruled world cinema. Like Lubitsch, Murnau, and Lang before her, she would try her luck in Hollywood—not as a hopeful émigré but as a garlanded conqueror. Though her trip to America was officially billed as a private visit, in reality she set sail to secure a stateside distribution deal for Olympia. Along with Ernst Jaeger, her old friend and press handler, and Werner Klingeberg, an official with the German Olympic Committee, she brought ten heavy film canisters with three different versions of the four-hour film.17 On October 29, 1938, Riefenstahl sailed from Bremerhaven aboard the liner Europa, little expecting the buzzsaw she would run into at the next port of call.

On November 4, 1938, when the Europa dropped anchor in New York, Riefenstahl’s arrival had already been heralded by shipboard radio and wirephotos beamed stateside. Speaking for his client, Ernst Jaeger denied the obvious, that Riefenstahl had come to America to publicize Olympia and negotiate a distribution deal. No, he said, she had come purely due to her “interest in America and as a sportswoman.”18

Mere tourist or not, Riefenstahl was Nazism’s second most photogenic face. More than that, though, she was a brilliant motion picture artist in thrall to a ruthless dictator, a match that inspired a special measure of loathing from the artists in the Popular Front. The deal she struck with the Nazis wasn’t exactly a Faustian bargain—the contract suited both parties—but the willing prostitution of beauty and talent to the coarse and brutal Nazis gave the lie to the notion that truth is beauty and beauty is truth. The previous envoy of Fascist cinema, Vittorio Mussolini, was a dilettante and daddy’s boy, a spoiled son of privilege; Riefenstahl was a self-made woman, a charismatic talent. Being the one Nazi filmmaker who was not a second-rater, who was as good, or better, than the Jews purged from Ufa, she intrigued, tantalized, and unnerved. “The gal has charm to burn,” gushed gossip monger Hedda Hopper, who was smitten with the lady. “As pretty as a swastika,” snarled syndicated columnist Walter Winchell, who was not.

In New York, anti-Nazi activists were waiting with their knives out. The Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League to Champion Human Rights sprang into action to isolate Riefenstahl and derail the distribution of the “Hitler-Riefenstahl” film. Founder Samuel Untermyer had stepped down the previous May due to ill health, but after five years the group had logged enough hours walking picket lines and handing out leaflets to operate on automatic. “This visit is part of the Nazi campaign to flood the United States with Nazi doctrines and is in accord with recent statements by German consuls here and German officials abroad in which they attacked American principles and ethics and sought to prove the superiority of Nazism,” declared the League.19

Studio-affiliated distributors assured NSANL that Olympia “won’t get to first base in the United States” and that “they would boycott the picture one hundred per cent.” Independent bookers were no less antagonistic. Foreign film importer Joseph Seiden rejected Olympia on the grounds that any profits from the film would be used “in the furtherance of Nazi propaganda both here and abroad.”20 Even under optimal circumstances, Olympia would have been a tough sell in the American market. At twenty reels—approximately 220 minutes, running times of the film varied—it was a dubious attraction even for dedicated sports fans. But the Nazi aura around Riefenstahl wiped out whatever commercial prospects her film might have had. Trafficking in Olympia was streng verboten.

Outside of the hard core of anti-Nazi activists, however, Riefenstahl herself was often looked upon more as a curiosity than a villain. Initially, reporters were intrigued, even bewitched, by the fetching beauty who blended the exotic allure of Marlene Dietrich and the fiery independence of Katharine Hepburn. “Leni Riefenstahl, an Individualist Even Under Hitler, Expects to Teach 1,000 Beautiful Woman to Ride Horses,” headlined a wide-eyed profile in the New York World-Telgram trumpeting her presence in the city and plugging her next project, an epic version of Heinrich von Kleist’s Penthesilea, with Riefenstahl in the saddle as the Queen of the Amazons (hence the need for a thousand female equestrians). She laughed at the inevitable question about her liaison with Hitler, praised the genius of Walt Disney, and denied the rumors that she was Jewish (“I am an Aryan for generations”). “There is one person at least in Nazi Germany who does as she pleases and doesn’t take dictation,” wrote the male reporter won over by her flirty manner and tentative English. “That would be Leni Riefenstahl.”

The date of the love letter to Riefenstahl in the New York World-Telegram was November 9, 1938, at which time the news from that night in Nazi Germany had not yet broken.21 The next day, the front-page banner headline in the paper read: MOBS WRECK 10,000 JEWISH SHOPS IN NAZIS’ 14-HOUR REIGN OF TERROR; BURN SYNAGOGUES ALL OVER NATION AS POLICE WATCH.22

So perfect for so long, Riefenstahl’s timing had failed her. On the night of November 9–10, 1938, while she was still being cast as glamorous celebrity instead of a Nazi henchwoman, the Nazis launched a campaign of antisemitic terror throughout Germany and Austria, the rampage known to history as Kristallnacht. Confronted by reporters, Riefenstahl denied the obvious. The Nazis, she said, would never do such a thing. The reports were false, one-sided, and incomplete.23

After Kristallnacht, Riefenstahl’s coy act as a political naïf—an artist only, gaze fixed on her muse—fell flat. No longer stroking her with sly gossip items and cute photo captions, the press spat out editorial condemnations and full-throated venom. Henceforth, her working vacation in America was to be a gauntlet of ostracism and insults. Columnists derided her, former colleagues deserted her, and politicians rebuffed her.

Ernst Jaeger would later write an eleven-part series for the Hollywood Tribune chronicling Riefenstahl’s coast-to-coast hegira, an insider’s tell-all written under the trashy title “How Leni Riefenstahl Became Hitler’s Girlfriend.” With retrospective schadenfreude, her now-estranged factotum painted a catty portrait of a diva in distress. As she lugged her film cans from city to city, the high priestess of Nazi cinema was disrespected and disparaged. “The only pictures Leni Riefenstahl could interest Americans in,” cracked a refugee director, “would be movies of an autopsy performed on her boyfriend’s brain.”24

Fleeing Judeo-centric New York, Riefenstahl headed south to Washington, D.C. She visited Mount Vernon and the Lincoln Memorial, but no invitation to lunch was forthcoming from FDR and no screening of Olympia could be arranged in the capital.

In Chicago, a city with a strong German population, the reception was marginally warmer. She surfaced to screen sections of Olympia to a friendly German audience of not more than thirty-five, seven of whom worked for the German consulate.25 While in Chicago, she made a side trip up to Detroit to meet with Henry Ford, the auto magnate, antisemite, and admirer of the Nazis. It was a rare taste of American hospitality.

Of course, the final destination of Riefenstahl’s long march across America was the spot her trip had been homing in on since she boarded the Europa in Bremerhaven—Hollywood, where the brilliance of Olympia would be recognized by her peers and rewarded with a lucrative distribution contract from a major studio.

When Riefenstahl stepped off the platform at Union Station in Los Angeles ready to vamp for the cameras, the only welcomers were a forlorn party of four led by Dr. Georg Gyssling, the Nazi consul in Los Angeles, who handed her a bouquet of flowers. Dismayed at the absence of flashbulbs, Riefenstahl wailed at Jaeger, “Where is the press?” “But you’re supposed to be incognito,” he replied. “Ja,” she said, “but not so incognito.”

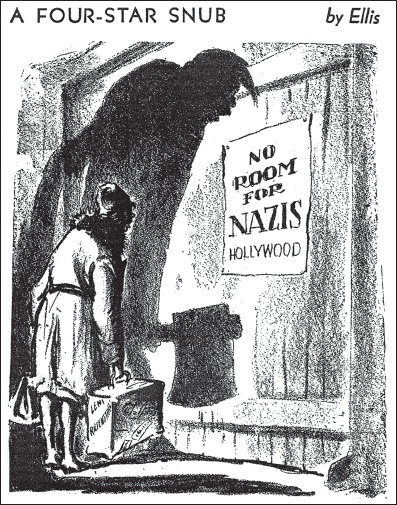

The Hollywood Anti-Nazi League was working hard to make her better known, to make her in fact the talk of the town. Redeploying the tactics that had rendered Vittorio Mussolini persona non grata the previous year, HANL launched a reverse publicity campaign. It published articles in Hollywood Now, posted notices on studio bulletin boards, and timed full-page ads for publication in the trade press. On November 29, 1938, HANL purchased space in the Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety to alert the citizenry that

“Ja, but not so incognito”: director Leni Riefenstahl and Nazi consul Georg Gyssling during her ill-fated visit to Hollywood in December 1938. (Courtesy Corbis Images)

Today Leni Riefenstahl, head of the Nazi film industry, has arrived in Hollywood. There is no room in Hollywood for Leni Riefenstahl. In this moment when hundreds of thousands of our brethren await certain death, close your doors to all Nazi agents. Let the world know there is no room in Hollywood for Nazi agents.

Sections of the ad copy scanned like poetry:

The Nazi star is at her hotel.

The man who directed her first picture is barred from his own country.c

The man who discovered her is in a concentration camp.d

The girl’s name is Leni Riefenstahl.

Her answer is “I am not Hitler’s girl friend.”

Our answer is … There is no room in Hollywood for Nazi agents.26

Just a little over a year earlier, a black-tie party for Vittorio Mussolini could be considered a coveted ticket to a swank affair. The annexation of Austria, the seizing of the Czechoslovakian Sudetenland, and the fires of Kristallnacht had converged to change the climate even in far-off California.

Signaling that the antipathy to Riefenstahl was not only personal but institutional, the major studios declared their gates closed. “American films are barred from Germany, so we have nothing to show Miss Riefenstahl that would interest her,” explained a studio executive.27 Asked about the “No Trespassing” signs, Dr. Gyssling denied that his guest was being barred. “I talked with Miss Riefenstahl over the telephone,” Gyssling said, “but she made no request for me to arrange any visits. She said nothing of being rebuffed and I am sure she would have spoken of the incident if it had occurred.”28 Everyone knew better. “So far as Hollywood is concerned,” gloated Variety, “she is just another tourist whom it is too busy to show around or be seen with.”29 Chimed in the Hollywood Reporter: “Leni Riefenstahl has found out just how hard being a bosom pal of Adolph Hitler has made the going in Hollywood.”30

Surprised to be “thus personally attacked,” Riefenstahl issued an aggrieved statement. “Immediately upon my arrival in New York, I told the press that my trip was absolutely private and that I had no official mission to fulfill. Furthermore, I would like to state that I have never had an official position in Germany, and therefore I could not be head of the Nazi film industry. I am a free creative artist. As a consequence of my work in The Blue Light, I was assigned to direct both great artistic documentary films of the Olympic games.”31 To help with damage control, she tried to hire Dick Hunt, a prominent Hollywood press agent. Hunt turned her down flat and, being a press agent, informed the press of his principled rejection.32

While Riefenstahl holed up in a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel and stewed, folks around Hollywood competed in gestures of ostentatious ostracism. Phil Selznick turned her away from his nightclub. Silva Weaver, fashion editor of the Los Angeles Times, called off a cocktail party. Actors that Riefenstahl had been on friendly terms with in Germany avoided eye contact and refused to do lunch.

A few tone-deaf—or just plain ornery—actors and filmmakers broke ranks and met Riefenstahl on the sly, out of sight of photographers. She spent a quiet evening with Vilma Banky and Rod LaRoque, acquaintances from S.O.S. Iceberg. Harboring no grudge about his loss to Riefenstahl at the Venice Film Festival, Walt Disney escorted her around his animation shop, showing off storyboards to his next full-length animated feature, Fantasia (1940). Winfield Sheehan, former head of Fox, and his wife, Viennese opera singer Maria Jeritza, sheltered Riefenstahl at their home in Palm Springs. Sheehan had been on the outs in Hollywood since he had left Fox in 1935 after its merger with Twentieth Century Pictures, and his taste in houseguests did not enhance his popularity.

Riefenstahl’s most prominent local booster was the powerful gossip columnist and harridan-about-town Hedda Hopper, who blabbed harmless tidbits about the stars but kept the best secrets to herself for leverage. She met Riefenstahl, was enchanted, and saw Olympia, and was impressed. Mounting her high horse, Hopper chastised Hollywood for its hypocritical inconsistency in the welcome given two different emissaries from European fascism. “Last year Hal Roach entertained Il Duce’s favorite son, Vittorio, at a great gala party. Our glamorous stars were proud to be photographed with him,” she pointed out, forgetting Mussolini’s own chilly reception the morning after, not to mention the seismic shifts in history that had occurred since. “Now Leni Riefenstahl, supposed to be Hitler’s erstwhile girlfriend, can’t even get a peek through a keyhole.” Olympia, opined Hopper, was made “without propaganda” and featured a winner’s circle of great American athletes, notably track star Jesse Owens, the African American Mercury who won four Gold Medals. “Why shouldn’t we be allowed to see them?” she demanded.33

Box Office columnist Ivan Spear typed out a terse reply. “Those who head the industry that liberally supports Mesdame Hopper, and who are familiar with what the policies and bigotries of Leni and her Aryan playmates have cost the studios, individually and collectively, would have a ready and convincing answer to Hedda’s query—if they took it seriously enough to feel it warranted a reply.”34

On January 7, 1939, Dr. Gyssling hosted a reception in Riefenstahl’s honor at his tony residence on 1801 North Curson Avenue. Over 200 guests feted the actress-director in a well-catered affair totally bereft of star power. “And not a single Hollywoodian among the 200, which indicates pretty clearly the rapid approach toward unanimity of the film capital’s feelings concerning Herr Hitler and his playmate,” exulted Spear.35

If not quite run out of town on a rail, Riefenstahl was all but cold-shouldered out to Union Station for an ignominious exit from the American film capital. On January 13, 1939, as a delegation from the German consulate stood and saluted stiffly in the chill morning, she boarded the Santa Fe Chief for the trip back East. The train reservations were made under an assumed name. She said she had enjoyed the climate and scenery, but kept mum about her very public shunning, saying only “I hope next time it will be different when I come, yes?”36

No, growled HANL, the trade press, and the metropolitan dailies. With one voice, they bid the Nazi filmmaker good riddance. Daily Variety wished her a quick trip back to “Adolf Hitler’s domain, along with the films of the Berlin Olympics, which she brought here to sell but which she couldn’t give away, even with a set of dishes.” Bestowing his mock year-end Oscar awards, columnist Ed Sullivan awarded an apt booby prize: “An Iron Cross to Leni Riefenstahl for the daffiest junket of the year, her tactless trip to Hollywood.”37

Pariah: a cartoon from the Daily Worker welcomes Leni Riefenstahl to Hollywood.

For turning the Nazi goddess into a social leper, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League bathed in the praise of a grateful community. “The Anti-Nazi League is to be complimented on its activity directed against Leni Riefenstahl and the concurrent actions of the studios in denying her entrance,” the Hollywood Reporter editorialized. “If Germany bars Hollywood’s product why shouldn’t Hollywood bar this German film representative? But without the blast of the Anti-Nazi League, apparently nothing would have been done.”38 No longer a cadre of fringe leftists, the group had come to occupy the center of cultural-political gravity in Hollywood.

On January 18, 1939, after a sullen train trip to New York, Riefenstahl boarded the German liner Hansa to head for friendlier shores. Before the ship sailed, she invited the press aboard for a final confab. As Riefenstahl nibbled hors d’oeuvres and autographed pictures, she spoke through an interpreter, who translated her remarks only after careful consultation about the answers.

It was a pity that the American people (“sportsmen all”) would be deprived of the chance to see Olympia, she sighed. Yes, the Hollywood producers behaved abominably, as might be expected, but the “better class” of Californians had treated her marvelously. She looked forward to returning to America at the earliest opportunity.

Yet the wounds from her flaying in Hollywood were still raw. Riefenstahl bristled at her “unfair” treatment from the motion picture industry and singled out the social and professional pressure brought to bear by the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. “If anyone talked to me, they would lose their job,” she claimed. “Is that American?”

“What would happen if a Jewish producer brought some film with him to Germany?” a reporter asked.

“Do you think America is all Jewish?” she snapped.

Riefenstahl wondered if any of the reporters had seen Olympia. None of them had. “That is the trouble. You don’t realize the film is very good. If you would know my picture, you would understand my work.” Exasperated at the injustice of it all, she could contain her frustrations no longer. “Only the bad things you write!” she cried. “Why don’t you write the good things?”39

Back on European soil, Riefenstahl vented her frustrations less diplomatically. “I was welcomed everywhere in the United States but in Hollywood—where the film industry is controlled by Jews and anti-Nazi leagues.”40