On the evening of December 8, 1938, with the fires from Kristallnacht out in Germany but the anger in America still burning, a group of well-heeled anti-Nazi activists gathered at the Beverly Hills home of actor Edward G. Robinson to weigh options and plan a response. Circulating among the stars, screenwriters, and producers—and sampling the libations—was the town’s resident wise guy, Groucho Marx. Raising his glass, and for once not his eyebrows, he announced, “I want to propose a toast to Warners—the only studio with any guts.”1

Groucho, who with his brothers was under contract to MGM, was toasting Hollywood’s other fraternal outfit for initiating production on a domestic espionage thriller called Confessions of a Nazi Spy, the first frontal assault on Nazism from a major studio, indeed the first time the four-letter word that had streaked across newspaper headlines and blared from radio bulletins since 1933 had been boldfaced in the title of a studio film. From the executive offices to the backlots, the news electrified the motion picture industry. “While making the rounds on the Hollywood front yesterday, we couldn’t help but feel the spark which had been set off by the Warners declaration that it would film the Nazi spy story in the raw, with no punches pulled, even insofar as real names were concerned,” wrote Billy Wilkerson, editor-publisher of the Hollywood Reporter. “One top executive of a rival studio went so far as to tell us that the Warners mob had more guts than a lot of other outfits rolled together.”2

In truth, the decision was a gutsy gambit, but not out of line with company policy. Of all the studios that made up the winner’s circle known as the Big Five, Warner Bros. alone wore the badge of anti-Nazism as proudly as the WB-emblazoned shield that was its emblem. Up until the outbreak of war in Europe, MGM, Paramount, RKO, and Twentieth Century-Fox figured business was business. Only Warner Bros. dissented, putting its money where its politics were. It cut off relations with Germany in 1933, contributed funds to an array of anti-Nazi causes, donated airtime for anti-Nazi broadcasts on KFWB, its flagship radio station, and injected anti-Nazi sentiments into its short subjects and feature films.3 No for-profit company did more than Warner Bros. to alert Americans to what Nazism was and where it would lead.

The story of Hollywood’s most famous bloodline moguls—level-headed chieftain Harry, backstage mediator Albert, tech geek Sam, and obnoxious front man Jack—is only partly the story of a smoothly operating dream factory run by a dysfunctional family. It is also the story of how the ideological commitment of two Hollywood moguls—eldest brother Harry M. and youngest brother Jack L.—helped make anti-Nazism synonymous with pro-Americanism. Prior to 1939, the connection was not self-evident.

Like many Hollywood brand names, the Warner brothers were of Eastern European Jewish heritage: father Ben, who emigrated from Poland in 1880, was so eager to erase memories of the Old World that the real family name was jettisoned before his boat docked in the New.4 In 1903, noticing how enthusiastically customers plunked down coins for a nickelodeon treat, the brothers got in on the ground floor of a growth industry—first exhibition, then distribution, finally production. By dint of hustle, hard work, and chutzpah, the quartet soon secured a precarious niche in the wide-open, wildcat business. Setting up shop in Hollywood in 1912, incorporated in 1923 under a logo officially writ as “Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc.,” they made the studio payroll mainly on the back of one of the most talented and least temperamental stars of the silent era, the canine matinee idol Rin Tin Tin, a German shepherd rescued from the battlefield by an American doughboy during the Great War.

In 1925 the mechanically fixated Sam persuaded his skeptical siblings to invest in a new-fangled technology that bid to expand the sensory range of the motion picture medium. The result was The Jazz Singer (1927), the epochal first sound film that was also, fittingly, a story of Jewish assimilation and all-American aspiration. (The original program for the film included a Yiddish-English glossary to help gentiles with the intertitled vernacular.) In a melancholy twist of fate, the Warner brothers did not attend the gala Broadway premiere to witness their triumphal breakthrough: Sam died the day before the film opened.

The Jazz Singer propelled the company from Poverty Row to the big time, but the house style was never as opulent or otherworldly as the product conjured on rival backlots. The Warner Bros. look was lean and hungry, urban and hardscrabble, clouded by cigarette smoke and bathed in noirish lighting, often to hide the bare-bones sets. The roster of contract players suited the atmospherics. Over at MGM, Clark Gable and Greta Garbo embodied the celestial glamour of the studio that boasted “more stars than there are in heaven,” but at Warner Bros. the actors were more down-to-earth, streetwise and smart-mouthed, typified by the likes of James Cagney and Bette Davis, guys who knew the backstreets and gals who had been around the block. They didn’t need to stretch too far to play taxi drivers, waitresses, truck drivers, shopgirls, bootleggers, and dime-a-dance dames on the make.

In the mid-1930s, the studio hit its stride. A series of “great man” biopics, notably The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936) and The Life of Emile Zola (1937), lent prestige and earned Best Picture Oscars, but its trademark genres were gritty crime mellers, fast-paced action pics, and multiple-hankie women’s weepies. Not least, in a series of moody, hard-hitting melodramas such as Black Fury (1935), Black Legion (1936), and They Won’t Forget (1937)—spiritual descendents of the even sharper-edged pre-Code firebombs I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), Heroes for Sale (1933), and Wild Boys of the Road (1933)—the studio pioneered a cycle of “social consciousness” films that fessed up to the fact that something called the Great Depression lurked just outside the theater lobby.

On and off screen, another quality set Warner Bros. apart. In film content and political affinities, it was the most frankly Jewish and fiercely anti-Nazi of all the Hollywood studios. In 1933, after Phil Kaufman, its Berlin branch manager, was pummeled in a back alley by Nazi brown-shirts, Warner Bros. became the first studio to sever economic ties with the lucrative German market.a The brothers also showed their colors by supporting the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, hosting fund-raisers, and shaking down employees for “donations” to the cause. At first allegorically, then more explicitly as Europe headed toward the brink, the studio agitated for racial tolerance at home while warning of the racist menace abroad.

To a company man, Warner Bros.’ corporate rivals opted for a more conciliatory approach. Despite frustration with Nazi censorship and economic restrictions—the banned pictures and the blocked currency—each of the other four major studios was willing to meet the Nazis halfway, or further. After 1933, German filmgoers with a taste for Hollywood cinema did not have a full menu to choose from, but they did not starve for lack of fare.

RKO officially bolted soon after Hitler came to power, but even with no offices in Berlin or formal middlemen for distribution it closed deals and collected money. “RKO has sold a few pictures into Germany in the past couple of years, but strictly on a cash and carry basis,” Variety noted in 1937. “If any German distrib offers to buy an RKO pic, paying dollars for it, he can have it. Otherwise, no dice.” Thus, as the distributor of Walt Disney’s desirable roster, RKO was ready to haggle with the Nazis had not its American client driven so hard a bargain. When Germany’s legions of cartoon fans clamored for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the animator set strict terms. “Walt Disney wants a cash guarantee on the line before he releases the picture and Germany doesn’t want to put up American dollars,” said an RKO executive in 1939. “Until then, there won’t be a deal.”5 There wasn’t.

RKO’s cash-on-demand policy ceded the bulk of the market to Paramount, Twentieth Century-Fox, and MGM, each of whom jostled for a piece of a shrinking pie. In the three-way competition, Paramount and Fox held an advantage over MGM, long top dog in Hollywood’s corporate hierarchy, because both studios produced newsreels in Germany, a side business that allowed them to circumvent restrictions on exporting hard currency earned from their feature films. Profits from commercial features playing in Germany could be spent domestically to produce the newsreels and then the footage could be exported and sold overseas—a roundabout way to sidestep Nazi financial restrictions, and hardly a financial windfall, but better than letting the funds sit in a Reich bank. The arrangement, Variety pointed out, meant Paramount and Fox were, unlike MGM, “not piling up coin internally.” For its part, MGM, despite the blocked currency and confiscatory transfer fees, didn’t “want to leave the field, such as it is, solely to Paramount and 20th.”6 Throughout the decade, the three studios bent to Nazi demands in order to smooth the course of commerce and keep the product flowing.

MGM was often reported to be “about ready to kiss the German market goodbye,” but the studio was never quite able to break off a relationship that paid, however measly the dividends. Working with the Nazis, however, required compromise and, sometimes, capitulation. In 1936, when pressure from the Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League to Champion Human Rights forced MGM to withdraw the shorts Sports on Ice (1936) and Olympic Ski Champions (1936) from the program at the Capitol Theatre in New York, MGM balked at pulling the films nationally. “Obviously, any official action nationwide would bring immediate reprisals against Metro product in Germany, where the company is still operating,” explained Variety.7

If not a quid pro quo, the bilateral arrangement between MGM and the Third Reich amounted to a suspiciously convenient chain of causality. In 1936 the elliptically anti-Nazi film Are We Civilized? (1934), an independent production from Raspin Productions, Inc., was booked into Baltimore’s Valencia Theater, a house aligned with the Loew’s circuit, MGM’s corporate parent. Dr. Hans Luther, the German ambassador to the United States, lodged an official protest with Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Loew’s New York office promptly canceled the booking. “Loew didn’t want to become involved in the exhibiting of the flicker because Metro pix are still being sold in Germany,” noted Variety. A week after canceling the Baltimore booking of Are We Civilized?, a slate of twelve MGM pictures was cleared for release in Germany.8

Not that all was smooth sailing for MGM in Nazi Germany. Douglas Miller, the acting commercial attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Berlin, felt that MGM was being treated more harshly than Paramount and Fox because “Metro was considered to be a Jewish firm abroad, while Paramount and Fox were considered as Aryans”—presumably because solid Anglo-Saxon nouns like “Paramount” and “Fox” sounded less semitic than Mayer and Goldwyn, the two surnames in the MGM acronym. Knowing that Paramount was founded by Adolph Zukor and Fox by William Fox, née Wilhelm Fried, both Jews born in the Austrio-Hungarian Empire, attaché Miller could only comment: “As a matter of fact, Jewish influence is strong in all these American moving picture companies.” Frits Strengholt, the non-Jewish Dutchman who headed MGM’s Berlin office, was also, in Nazi terms, a troublemaker. According the Miller, “while honest and trustworthy, [Strengholt] is an unbending fellow who tries to stand on his rights, whereas the representatives of the other American companies have been more successful in personal contacts with local officials, and have cultivated these more extensively.”9

To serve as a counterweight to the uppity Strengholt and to help grease the skids with the Nazi authorities, MGM put the nephew of German foreign minister Konstantin von Neurath on the payroll of its Berlin office.10 As late as June 1939, MGM was still trying to placate the Nazis by playing host to a group of German newspaper editors on a “good will” visit to America, even providing a VIP tour of the MGM lot at Culver City. Though the editors swooped in and out before the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League could launch a protest, MGM was the only studio that by then would have laid out a welcome mat for emissaries from Joseph Goebbels.11

In March 1938, when the Nazis rolled into Austria, the studios faced the same personnel crisis in their foreign offices as when the Nazis took over Germany in 1933. Each responded according to type. “It looks like the end of the Austrian market,” said a spokesman at Universal, reluctant to say too much until hearing from its branch manager in Vienna, William Satori, a native-born Austrian who had recently taken out citizenship papers in the United States.12 (Satori escaped Austria, worked stateside for Universal during the war, and returned to Europe in the postwar era for Monogram and Allied Artists.) Felix Bernstein, MGM’s Jewish sales manager in Austria, was immediately removed. “[It is] anticipated that Metro will name a new sales chief who is acceptable to [the] Nazi-dominated governmental body,” Variety reported, matter of factly.13 (Bernstein landed on his feet in Hollywood with a sweet assignment for a Viennese Jew: technical advisor on MGM’s Florian [1940], an equestrian biopic chronicling the exploits of a magnificent white Lipizzaner stallion owned by Emperor Franz Josef of Austria.) Paramount stood ready not only to ship its Jews out of Vienna but its Catholics as well “to conform with ideas of the new Nazi regime.” The manager of RKO’s Vienna office, Michael Havas, was transferred to Rome. For a time, the whereabouts of Twentieth Century-Fox’s legal representative in Vienna, Dr. Paul Koretz, was unknown and his “safety is in doubt.” (Koretz escaped, making his way to London to head up Fox’s story department, and thence to Hollywood during the war.) No longer needing a branch office in Vienna, Fox did business with the Greater Reich from its main office in Berlin.

Reporting on the annexation of Austria, Variety issued a resigned, non-judgmental assessment. “Expect usual number of anti-Semitic moves directed against the picture business.” It was also expected that the usual antisemitic moves would not deter MGM, Paramount, and Twentieth Century-Fox from adapting to new market realities. “Of course, [their] offices have reduced their staffs considerably and dismissed all Jewish executives,” noted Motion Picture Herald. The casual “of course” is the giveaway: unlike 1933, when surprise and shock greeted the policy of Aryanization, by 1938 it was the predictable and acceptable cost of doing business with the Nazis.14 “Within a few days of the annexation, nearly every Jewish exhibitor, particularly the owners of first-run theaters, was taken into custody on trumped up charges of being in arrears on tax payments,” reported an on-site correspondent for Motion Picture Herald, a stringer who wisely took only the byline of “Special Correspondent.” “The notice ‘Under Aryan Management’ or ‘Under the Commissariat of the Reichsfilmkammer’ is seen at the entrance of almost all cinemas owned hitherto by Jewish exhibitors.”15

Fox, Paramount, and MGM all hung on despite the fact that the financial compensations from the German market were steadily diminishing. Due to ever-tightening currency restrictions, the studios that stayed behind found it harder and harder to squeeze money out of the Reich. “Some major film officials estimate that little more than 10–15% of the total rental money actually is withdrawn to this country because of the blocked-[Deutsche]mark situation as well as the disparity in value between the mark in the Reich and in the U.S.,” reported Variety in mid-1939. “Added factor is the premium charged for such withdrawn coin. Blocked marks is the method employed by the Nazis whereby they ear-mark a certain part of coin for a stay in Germany. Major film companies admit there is little they can do about the situation.”16

Thus, in an irony better appreciated in retrospect, even as Nazi bellicosity and violence toward Jews in Germany escalated, the trademark product of Jews in America remained up on marquees throughout the Third Reich. Before German Jews were banned from motion picture theaters in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the scholar, film buff, and diarist Victor Klemperer, an avid fan of the cinema since the glory days of German Expressionism, often took refuge from the insanity of the Third Reich by treating his wife and himself to a night at the movies. He winced at the propaganda newsreels, but even from a seat in Dresden, an import from Hollywood was not considered exotic fare. In 1937 he caught screenings of MGM’s earthquake disaster film San Francisco (1936), whose seismic upheavals must have reverberated metaphorically, and Universal’s Mississippi riverboat musical Show Boat (1936), whose subplot about miscegenation in the Deep South abided with Nazi racial laws. A “very pleasant film evening,” he said of Showboat, “thoroughly American in music, dance, fights, gum chewing.” Of San Francisco, his only comment was a wistful “all too American,” seemingly glad, if for only two hours, to be in a city besides Dresden.17

Yet as the 1930s wore on, fewer and fewer American films crossed Nazi borders. By 1937, only thirty pictures a year entered Germany, with the studios having to submit to the censors about three or four times that number to meet their quota. In the first half of 1938, a mere thirteen films passed inspection.b Given the sparse profits and near-confiscatory monetary policies, many industry insiders questioned why the major studios continued dealing with the Nazis at all. Politics and morality aside, the economic rewards were paltry. Glancing over the slim pickings, Variety figured that for Paramount, Twentieth Century-Fox, and MGM, “it might be just as well to forget the headaches in the German sales.”18

Nonetheless, in the end, the three studios were willing to suffer the mental anguish to stay in the game. Taking the long view, their unwavering commitment to the German market was less about the immediate lure of hard cash than about maintaining a foothold in a market that had lately been so profitable and, with a change of regime, might well be again. As a hedge against the future, it was thought best to keep the distribution infrastructure in place on the off chance that the market should open up again. The moguls did not expect the Third Reich to last for a thousand years.

At the beginning of 1939, the Nazis turned the financial screw an additional notch by leveling a tax of 75 percent on exported funds, but even then Fox, Paramount, and MGM refused to quit the field. “Today [January 1939] the business of the remaining three is described in New York as almost negligible,” puzzled Motion Picture Herald, when, for the first time in memory, not a single American feature was playing in Berlin’s first-run theaters. The trade weekly estimated that each studio recouped “no more than between $15,000 to $50,000 from the market”—a pittance.19 From the period of January to May 1939, only five Hollywood films entered the Reich. “Hitler Hates Us,” joked a headline in the Hollywood Reporter.20

Only at Warner Bros. was the feeling mutual.

In September 1938, trade reporter Vance King was roaming the Warner Bros. lot when he was accosted by none other than Harry M. Warner. Why, Warner demanded, had King never mentioned the series of patriotic shorts his studio had been making since 1936? A chagrined King said he had never seen one. Warner would remedy that oversight immediately. The studio kingpin marched the reporter into a projection room and ordered up a sampling.

After the private screening, Warner took his captive audience aside for an exclusive interview about his labors of love. To be sure, the shorts had met with “tremendous success,” but Warner Bros. was not merely peddling program filler, it was serving the needs of the nation. “In producing [the patriotic shorts], we feel that we are making more than a commercial product,” Warner insisted, warming to his topic. “We believe that we are rendering a service to the entire nation through the presentation of subjects that inspire greater patriotism.”21

Like other major studios, Warner Bros. maintained a shorts department that produced 10- to 20-minute short subjects (also known as one-or two-reelers) to round out the exhibitor’s balanced program and to keep soundstages humming during the downtime between the production of feature films. All of the major studios released trademark shorts and cartoons, usually stitched together in-house, sometimes farmed out to independents—MGM had the Fitzpatrick Travelogues and Pete Smith specialties, Columbia had the Three Stooges, and Warner Bros. had its Merrie Melodies cartoons and Broadway Brevities.

In May 1936, Warner Bros. assigned the minor budget line a major task. The studio announced a commitment to a series of patriotic short subjects whose source material would be drawn from the colorful pageant of American history. A special production unit comprised of supervising producer Gordon Hollingshead, producer Brian Foy, and director Crane Wilbur was assigned to oversee the series, which was initially dubbed “the American Parade.” To devote more resources to the enterprise, Warners cut back on the production of its musical shorts.22 To ensure historical accuracy, research for the series, so said Warner Bros.’ publicity department, would be “done in Washington in government files.”23

Shot in brighter-than-life Technicolor and lavished with front office attention, the patriotic shorts waved two flags—the nation’s and the studio’s. As such, they were sent out in style. Radio City Music Hall showcased each of the series in its program lineup, thereby guaranteeing attention from New York critics and audiences. Beginning in October 1938, each Wednesday and Saturday evening on KFWB, the studio broadcast radio versions of the shorts on a new series called Our America.24 The later slates of shorts were also released under the company name—Warner Bros.—not under the Vitaphone logo as had been the policy with shorts since the onset of sound.

To establish the civic bona fides of the enterprise, Warner Bros. enlisted the cooperation of educators. On September 1, 1938, at the Warners Hollywood Theater, 1,000 teachers convened for a special screening highlighting the shorts. The versatile actor John Litel, a non-marquee name called on to impersonate a series of colonial greats in powdered wigs and long stockings, read a message on behalf of Harry M. Warner. “Educators have encouraged us in our efforts to bring these notable historical moments to life,” wrote Warner. “Their help has inspired us to put more time, effort, and money into them. The result is a series of shorts of which we, at Warner Brothers, are proud not merely because they are interesting to audiences, but because they represent part of our contribution to a better understanding of the ideals and the achievements of those patriots who laid the foundation of our United States of America.”25 Three months later, in response to numerous requests from American Legion posts and other patriotic organizations, Warner Bros. formally established an “Americanization” department to coordinate screenings of the shorts with educational and civic groups. Department head Jack Holmes went on multicity tours to publicize the series and arrange screenings.26

The first of the lineup was Song of a Nation (July 1936), based on the backstory to “The Star Spangled Banner,” composed by Francis Scott Key under the rocket’s red glare of the bombardment of Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. The planned slate of capsule history lessons was also to include The Louisiana Purchase, The Fall of the Alamo, Patrick Henry, The Declaration of Independence, The Burr-Hamilton Duel, John Paul Jones, Thomas Edison—The Wizard, and The Hoosier Youth (about the Indiana boyhood of Abraham Lincoln).27 In the next years, some of the scenarios fell by the wayside and new ones were added, but the titles in the inaugural package give a good sense of the animating vision: presold passages from American history that every schoolchild would be familiar with but that Warner Bros. would punch up with action, drama, and primary colors.

The second and best known of the initial run of releases was Give Me Liberty! (December 1936), a fanciful account of the behind-the-scenes marital crisis that nearly silenced the ringing declaration by Patrick Henry in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1775. In Warner Bros.’ retelling, Henry (played by the reliable John Litel) manages to overcome the misgivings of his pacifist wife to rally his countrymen to the cause of rebellion against British tyranny. Savoring his big moment, Litel wraps his voice around the speech, building slowly in intensity before slamming home the rallying cry that most moviegoers could mouth the words to: “I know not what course others may take, but as for me—give me liberty, or give me death!”

During a special screening of Give Me Liberty! for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the stirring recitation inspired prolonged applause, an accurate augur of the Academy Award given the film that year for Best Short Subject in Color. “I was afraid the audience would find this tiresome, but most of them must have learned Patrick Henry’s oration in school because [Give Me Liberty!] aroused a great deal of interest,” reported a pleasantly surprised theater manager.

Other entries were Under Southern Stars (February 1937), about the death of Confederate general Stonewall Jackson, and Romance of Louisiana (March 1937), about the Louisiana Purchase, but the most celebrated—and curious—was The Man Without a Country (November 1937). Based on a short story written in 1863 by Edward Everett Hale, a work of pure fiction meant to inspire loyalty to the Union during the Civil War, it marked a departure from the highly touted scholarly rigor of the series. However, the liberties with the historical record served a larger historical purpose. Lt. Phillip Nolan (John Litel) is a young naval officer whose ambition for advancement leads him to conspire with the adventurer Aaron Burr in a plot to set up an independent fiefdom west of the Mississippi in 1805. Dragged before a court-martial for his role in the harebrained scheme, the hot-headed Nolan blurts out a shocking blasphemy. “Damn the United States!” he cries. “I hope I may never see or hear of the United States again!”

Nolan gets his wish. A Navy court-martial condemns him to an eternal exile at sea, never again to set eyes upon or hear about the homeland he cursed. Nolan’s shipmates are forbidden from so much as uttering the sacred name of the United States in range of his hearing. His devoted, long-suffering fiancée petitions president after president to pardon him, but the verdict of military justice is final. Not even Abraham Lincoln will extend his legendary mercy to the wretched heretic. Sixty years later, penitent and punished, the ancient mariner lies on his deathbed. Under his pillow is an American flag, sewn from scraps of colored cloth collected over the years.

The Man Without a Country grabbed the second Oscar in a row for the series, winning the 1937 Academy Award for Best Short Subject in Color. It also earned an asterisk mark in Production Code history for being granted a verbal dispensation that would not be heard again until Rhett Butler’s brusque kiss-off of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind (1939)—the use of the word “damn” on the soundtrack of a Hollywood film.

However, despite the Academy kudos and the studio chest-thumping, the Americanism series had little as yet to do with American values. The first entries sent out a nonpartisan glow of free-floating patriotism. The evenhanded selection of Stonewall Jackson to be an honored bust in the pantheon of American heroes indicates how remote from ideology the chapters from American history might be. According to Warner Bros., the Confederacy was a cause as deeply American as the Union.

Likewise, The Man Without a Country pledges allegiance to an America utterly detached from its founding principles. The film salutes a protofascist doctrine of unconditional fealty to the nation state as enforced by uniformed officials determined to mete out every last lash of a harsh sentence. The opening crawl for the film reads: “May this story serve as it has in the past to awaken in the hearts of all men a deeper love for their homeland, a greater homage to their flag.” American patriotism is yoked to icons and talismans—the Stars and Stripes, the name of the nation—but not to religious tolerance, freedom of expression, or the autonomy of the individual. The country the man is without might just as well be Nazi Germany.

Subsequent entries in the series would be more explicit about the self-evident truths held by American patriots, more tied to themes of religious and ethnic tolerance. They would also be positioned more pointedly, if still always allegorically, in opposition to Nazism.

The 1938–39 season called for five inspirational parables: Teddy Roosevelt and His Rough Riders, Remember the Alamo, American Cavalcade, The Declaration of Independence, and Lincoln in the White House. In part because the series was becoming more transparently present-minded, in part because the geopolitical crises of 1938 made the embrace of traditional American values a shelter from the chaos and danger abroad, the next round of patriotic shorts attracted greater attention. As events in Europe grew more ominous, the lessons from the American past sounded less like a distant trumpet and more like a call to arms.

Where better to begin than The Declaration of Independence (October 1938)? The story behind the parchment is built around the action-packed exploits of Caesar Rodney, Delaware delegate to the Second Continental Congress, a dashingly handsome rebel who eludes Tories and Redcoats to arrive in Philadelphia in the nick of time to cast the deciding vote on July 4, 1776. “We have champions in England,” Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee tells his colleague Thomas Jefferson as the men travel by coach to the Second Continental Congress before taking a swipe at the contemporary 75th U.S. Congress. “It’s the conservatives in our own congress that I’m worried about.” In the most pointed historical note, Jefferson (John Litel again) is shown attempting to include his condemnation of the slave trade into the original draft of the Declaration. “I’m sorry but that antislavery clause must come out,” insists John Adams, protecting the profits his New England constituents receive from the traffic in slaves. Ever pragmatic, Ben Franklin agrees. Jefferson reluctantly relents and scratches out the lines, muttering “it only puts off the trouble to another day.”

Released in the wake of the signing of the Munich Pact, the story of the signing of the Declaration of Independence benefited by way of comparison. Radio City Music Hall manager W. G. Van Schmus wrote Harry M. Warner to pass on word from the field. “You would be amazed and gratified at the reception, with applause not only at the end but breaking out spontaneously during the course of the picture,” he enthused. “The subject is one that should be thoroughly familiar to all of us, and yet, somehow, is not. It has been treated with such imagination and dramatic effect it makes a profound impression. I am happy to have the privilege of showing it on our screen.”28 Few observers missed the connections between 1776 and 1938. “There is that about the state of the world today which makes for a considerable national consciousness,” observed Motion Picture Herald editor Terry Ramsaye, who couldn’t resist a snarky description of the short as “an action picture with a suspense sequence.” Box Office also picked up the link across the centuries. “It transcends the realm of accepted screen entertainment in that it not only is intensely absorbing, but provides more than a little food for thought at a time when personal liberty is being made the target of reactionary groups.”29

Inevitably, the series went to the other great wellspring of patriotic sustenance in American history. A ripe example of the rampant Lincolnphilia that enraptured so much of Great Depression America, Lincoln in the White House (February 1939) was a tributary in a river of devotion that also included Robert E. Sherwood’s popular Broadway play, Abe Lincoln in Illinois, and Fox’s twinpack, Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) and Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940). Directed by William McGann, written by Charles L. Tedford, and starring veteran Lincoln impersonator Frank McGlynn Sr., the film tracks Lincoln from his inaugural address on March 4, 1861, to the Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863. Whether playing with his son Tad (cherubic child actor Dickie Moore), showing mercy to a court-martialed Union private, or asking a Union band to play “Dixie, “the warm humanitarianism and conciliatory spirit of the Great Emancipator exists in the same lean frame as his frontier fortitude and moral rectitude. The recitation of Lincoln’s 272-word elegy to the Union dead at the site of the pivotal battle of the Civil War, presumably with members of the audience joining in for at least the first and last lines, was the emotional highpoint.

Variety’s Abel Green, no easy audience, succumbed fully to the patriotic spell. “If visual education ever assumes the wide importance its advocates have been urging, this excerpt alone is surefire for every classroom,” he wrote.30 “A must for American screens,” decreed the trades. “Here is a picture that is not only an honor but a duty for every theater to show.… Harry Warner has done the industry and the nation a genuine service in this memorable instance.”31

The official release date for Lincoln in the White House was February 12, 1939—the anniversary of Lincoln’s birthday—and Radio City Music Hall was accorded first honors. “The blasé Music Hall audience salvoed this film like it was the 4th of July,” reported Abel Green. “It’s a natural, of course, now amidst the world strife between democratic and demagogic advocates, but at all times it is forthright entertainment and sound Americanism.”32 “This subject should be played in every theater in the country, regardless of run or size,” lectured Box Office. “It is not only a subject for February 12, but one that comes at a time ripe for maintaining the spirit of Americanism.”33

By far the most explicit colonial-era broadside at Nazism concerned a Founding Father who was neither Deist nor Protestant. After Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln, the hero of Sons of Liberty (April 1939) would be a name unfamiliar even to history buffs: Haym Salomon, the Jewish American financial backer of the American Revolution. The audacity of the topic—and uncertainty over how to handle it—is indicated by its stop-and-start production history. Originally slated as a follow-up to The Man Without a Country under the title His Country First, Sons of Liberty was for a time considered for feature-length treatment. Then the “Jewish angle” was to be downplayed in favor of a story built around George Washington. Then it was reconceived as a four-reeler, then a three-reeler, and finally a two-reeler with Salomon as the hero.

Clocking in at 23 minutes, Sons of Liberty glitters with all the sheen of a big-budget feature production: a Technicolor format, a prestige director (Michael Curtiz, straight from The Adventures of Robin Hood [1938] and Four Daughters [1938] ) and a top-tier cast fronted by Claude Rains, Donald Crisp, and Gale Sondergaard. “Warner Bros. produced it like a feature!” blared trade ads, truthfully. “Warner Bros. promoted it like a feature!”

No sentient moviegoer in 1939 would have missed the echoes of the day’s headlines. The first shot shows a tableau of huddled refugee masses in eighteenth-century garb. “The first Americans were Europeans who came to the New World in search of liberty. In the dangerous days of the Revolution, these people of many races and many creeds, long oppressed in their own native lands, dedicated their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to the creation of a free America” exposits the opening script, offering an interpretation of American history that erases the Puritan errand into the wilderness in favor of a secular vision of America as the last best hope of mankind. “Persecution and intolerance drove my family into exile,” says Salomon (played by the dignified British import Claude Rains), explaining his zeal for the rebel cause. “I came to America in search of liberty and I found it here. And now that liberty is threatened I want to join those who are fighting to secure it.”

The Sons of Liberty are united by more than a desire to cast off the yoke of tyranny. Arrested by the British and tossed into a holding cell for rebel prisoners, Salomon is informed by a Yiddish-accented friend that a fellow prisoner (“a good Christian lad”) condemned to be hanged is in need of religious comfort. The youth cannot remember the words to the Twenty-third Psalm. Salomon approaches him and begins to recite the psalm (“The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not want”). Thus prompted, the lad chimes in and the two patriots recite the psalm together. Now, at peace with God, the condemned man can go to his death with the solace of a heavenly reward. Calling the youth to the gallows, a Redcoat guard barks out his name: “Nathan Hale!”

Salomon escapes from prison and continues his revolutionary service—a good thing too because the fate of the embryonic nation hangs in the balance. Desperately in need of funds to pay the disgruntled Continental army, George Washington knows where to turn. He dispatches an emissary to Salomon with an urgent plea.

The Jewish patriot is at temple observing the holiest day on the Jewish calendar, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. When Washington’s messenger barges through the doors of the synagogue, Salomon heeds the summons.

“Haym—have you forgotten this is the Day of Atonement?” chides the rabbi.

“I’m sorry, rabbi, but this is very urgent,” says the messenger, explaining his appeal comes directly from General Washington.

When the rabbi hears the name of Washington, he is stunned into reverential submission. “An appeal from General Washington must be heeded,” he says. “God will forgive us.”

Salomon pleads with the congregation to dig deep for the necessary donations. “Centuries of bitter persecution have taught us the value of liberty,” he reminds his kinsmen. To sustain the noble cause, the congregation willingly empties its pockets.

Though liberty will be secured through the courage and generosity of the Jewish American patriot, a postwar denouement shows that Haym Salomon has reaped no personal profit from the American Revolution—on the contrary. In 1785, on his deathbed, the observant Jew and steadfast patriot refuses to sign the legal documents that will secure his patrimony for his children, it being the Sabbath, when no business may be conducted. The banker Washington turned to in the nation’s hour of need dies penniless. His dying wish to his wife is “to raise our children to be good Americans.”

While eulogizing a forgotten Jewish American patriot and making an implicit plea for America to welcome refugees from Nazism, Sons of Liberty also had to tread carefully around an inconvenient historical fact. The tale of colonial rebellion against a harsh tyrant risked vilifying the enemy of the eighteenth century (the British) at the expense of the ally of the twentieth century (also the British). Conveniently enough, as the funds raised from Salomon and the Jewish congregation are being rushed to Washington, it is a cavalry of Hessians not British Redcoats that attacks the coach transporting the money. (Fortunately, Washington’s men intercept and rout the German mercenaries.) No less important, American audiences cannot be left with the impression that the stereotypical ethnic niche carved out by Jews—money and financing—is their sole contribution to the Revolutionary War. Among the congregation at the Yom Kippur service, one man has sacrificed two sons to the Revolution, another has lost an arm. Jewish blood, not just Jewish money, has been spent in the cause of American liberty.

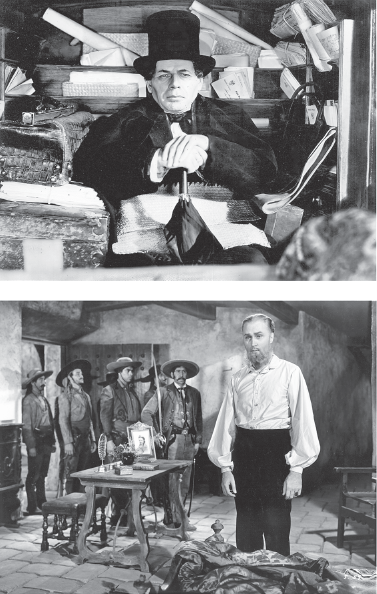

“Raise my children to be good Americans”: Claude Rains as Hyam Salomon, Jewish hero of the American Revolution, in Warner Bros.’ patriotic short, Sons of Liberty (1939).

Critical response to Sons of Liberty was ecstatic. At a press screening in New York, hardened scribes from the trade press applauded “spontaneously and sincerely.” The Veterans of Foreign Wars endorsed it, Jewish groups endorsed it, and the trade press reached for superlatives. “There has never been a short subject of finer merit,” stated the Showmen’s Trade Review. “Transcendently magnificent,” exclaimed the Film Daily. “With isms running amuck in a troubled world, this short is like a beacon of light in the darkness.”34 Only Variety refused to join the chorus. “Obviously a compromise,” it demurred. “[The film] reflects a certain hesitation and confusion of counsel. While not without some effectiveness as propaganda in favor of tolerance and projected with restraint, the short is extremely sketchy in continuity and time elements.” Not to mention religion. “A synagogue interior and a ‘rabbi’ addressed by title, are the sole non-secular connotations.”35

In ballyhooing the patriotic shorts, Warner Bros.’ public relations department did not have to fake sincerity. “We sincerely believe this series is an important one, particularly so in these troubled times when the nation is faced with ‘isms’ of all kinds,” Norman H. Moray, the studio’s sales manager for short subjects, announced.36 Jack and Harry also sent personal letters to exhibitors encouraging them to get behind the shorts. “We’re interested in showing what’s been going on here since 1612 and keeping it going on,” Jack Warner declared in 1939. “Yes, you could call it defensive Americanism—we aim to do our part in preserving the United States as is and in making Americans conscious of their heritage.”37

The planned slate for 1939–40 called for five titles: The Monroe Doctrine, Nathan Hale, The Father of His Country, Old Hickory, and Teddy, the Rough Rider. “Warners are sinking heavy dough into these classy shorts … each planned for one hundred grand less distribution costs,” reported the Film Daily, “… all being made with featured cast, writers, and directors … on the same magnificent scale as those patriotic shorts that have preceded them.”38

A few exhibitors squawked about doing their patriotic duty. “We’ve got 530 theaters, lots of them running double features too, but they’ve got standing orders to run the Americanism shorts if they've got to kill the second feature to do it,” said Jack Warner. “Any exhibitor who hasn’t enough love for the rights of man to run an Americanism short isn’t an American”—or, Warner did not need to add, in business with his studio.39

Until the watershed breakthrough of Confessions of a Nazi Spy, the anti-Nazism of Warner Bros. on screen was implicit and allegorical. Off screen, however, the studio telegraphed its message in capital letters. Out front and in public, Harry M. and Jack L. Warner made anti-Nazism company policy and personal business. They wrote checks, sponsored events, lent their names to petitions, and put the squeeze on colleagues and employees for donations. In the ranks of Hollywood’s Popular Front, directors, screenwriters, and actors were common enough. The two Warner brothers were the only active moguls who were also staunch anti-Nazi activists.

Low-key family man Harry, the eldest brother and senior partner, was based in New York, with the Wall Street moneymen and the executive board of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, his formal title being president of Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc. Irascible, randy Jack, the youngest brother, ran the day-to-day operations on the Burbank lot, taking an ego-stroking “executive producer” credit on Warner Bros.’ features, his byline arching over the company logo or under the title as the executive “in charge of production.” The two squabbled over nearly everything—money, films, authority—but on Nazism they saw eye to eye.c

KFWB, the company’s radio station established in 1925, amplified the anti-Nazism message. Some of the loudest radio salvoes against the Nazis were fired not by the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League but by Warner Bros., the group’s main corporate patron. Typical was a special titled “Four Years of Hitler,” broadcast over KFWB on January 30, 1937, featuring lyricist Oscar Hammerstein, comedian George Jessel, and screenwriter Dudley Nichols offering responses to Hitler’s rants.

Warner Bros.-owned and affiliated theaters were also in synch with directives from the front office. Harry monitored the programming in the studio’s theaters and expunged anything that smacked of Nazism. In 1936 he banned the special newsreel issues of the first Max Schmeling–Joe Louis championship bout from all Warner Bros. theaters.40 The African American fighter Louis, the Brown Bomber, had lost to Schmeling, the great Aryan hope, for the heavyweight championship of the world, a fight card with more geopolitical than pugilistic significance. Two years later, in the most anticipated rematch of the 1930s, Louis flattened the Nazi in the first round, knocking him out in two minutes and four seconds. Warners expressed no objection to bookings of The Louis-Schmeling Fight (June 1938), a newsreel short that stretched out the fight coverage to seventeen minutes.

The studio’s open-armed embrace of a non-motion picture star from Germany also made clear where the brothers stood. In March 1938, in a departure from the low regard in which writers were usually held around Warner Bros. (it was Jack who dubbed his stable of screenwriters “schmucks with Underwoods”), Harry and Jack underwrote and sponsored a visit by the famed German novelist Thomas Mann, the exiled author whose Weimar era books had served as kindling for the Nazi book burnings in 1933.d Mann had come to Hollywood to speak at an anti-Nazi rally at the Shrine Auditorium on “The Coming Victory of Democracy.” Jack hosted a $100-a-plate dinner for Mann, with the proceeds—an estimated $10,000—going to the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. “The limited invitation list will be the envy of all admirers of Mann, who with Albert Einstein is the most prominent critic of the Hitler regime,” bragged Hollywood Now.41

On April 1, 1938, the day Mann was scheduled to speak, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League devoted its “Talent in Exile” show on KFWB, scheduled from 6:30 to 7:00 p.m., as a kind of warm-up act for the speech. Actor J. Edward Bromberg played Dr. Edmund Nobel, one of Austria’s most famous child specialists, who had reportedly committed suicide during the Nazi invasion of Austria;e singer-actress-activist Helen Gahagan sang songs by banned German composers; and cartoonist Milt Gross spoke on the artist’s role in defending democracy.42

Jack Warner’s soiree for Mann marked something of a turning point for up-front, no-apologies incursions into politics around Hollywood. Mere actors and screenwriters may not have had the executive status or real-world acumen to justify their involvement in serious affairs of state, but when money-minded moguls cast their lot with the artists of the Popular Front, they lent credibility to what might otherwise be written off as feather-brained idealism. “Though up to now producers have tried hard to turn their backs on political upheavals abroad, figuring it was bad biz to air their own political biases while trying to sell the foreigners a bill of goods, conditions have changed so much that many are in favor of saying, ‘Nuts to the foreign market, let’s be ourselves,’” Variety reported.43 Of course, Warner Bros. had been saying nuts to the Nazis since 1933.

Closing ranks with the Popular Front, however, meant that Harry and Jack needed to protect their right flank. The Dies Committee hearings of August 1938 had given a congressional megaphone to what had long been whispered in country clubs and circulated in antisemitic leaflets: that Hollywood, the Jewish fiefdom, was a hotbed of Bolshevism, that the moviemaking of the moguls was an un-American activity. While tearing into the swastika, the brothers took care to wrap themselves in Old Glory.

The perfect occasion for Warner Bros. to show its colors was provided by the most red, white, and blue-plated organization in America. In September 1938, the month after the Dies Committee staged its first round of hearings, the American Legion held its annual convention in Los Angeles. The leaders of the motion picture industry fell over themselves honoring the conventioneers.

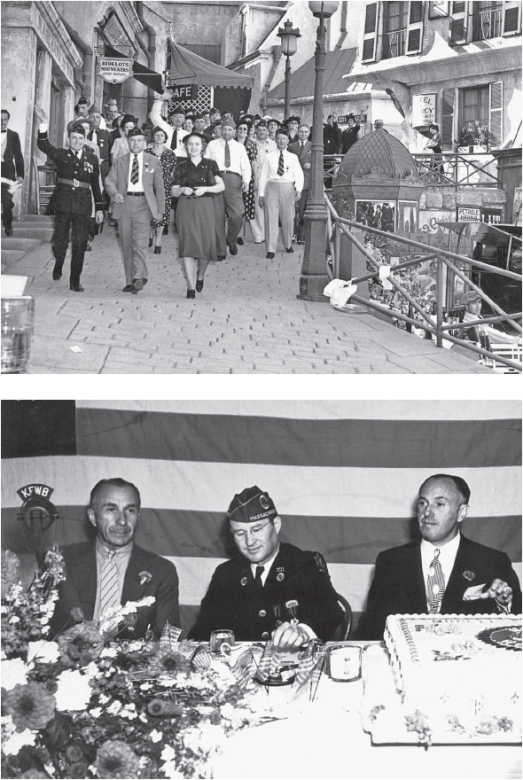

All week, Hollywood treated the veterans like visiting royalty—welcoming the leadership to the studios, feting the conventioneers with parties, dinners, and teas, and providing star-guided tours of the sound-stages and backlots. A huge parade with Frank Merriam, Governor of California; Daniel J. Doherty, National Commander of the Legion; and a phalanx of motion picture executives jammed traffic from Hollywood to the San Fernando Valley. Other tributes included a gala “Motion Picture Night” at Olympic Coliseum, banquets at swank hotels, and special teas for the legionnaires and their wives hosted by Jeanette MacDonald, Marion Davies, and Shirley Temple. At the Paramount Theater, comedienne Martha Raye played mistress of ceremonies for a special screening of Paramount’s Sons of the Legion (1938), a one-hour homage that, if it hadn’t been made to order for the convention, might have been. “It has plenty of flag waving, bugles blowing, lectures on Americanism, and occasional shots of marching Legionnaires,” noted the Hollywood Reporter. “Perhaps it is a little on the propaganda side.”44

In paying tribute to America’s veterans, Warner Bros. surpassed both its studio rivals and the city fathers of Los Angeles. Jack and Harry provided A-list escorts and privileged access to anyone wearing an American Legion cap. On September 19, 1938, the brothers opened the gates of the Burbank studio and gave the starstruck veterans the run of the sound-stages and backlots. “One of the great motion picture studios capitulated to a force of 35,000 Legionnaires and their friends,” beamed American Legion Magazine, the organization’s glossy monthly, aglow at the memory. “For five hours a procession of visitors, by invitation, streamlined through the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank, and at the conclusion screen luminaries filled a studio grandstand to give the Legionnaires a rousing cheer.”45 With newsreel-like speed, Warner Bros.’ shorts department produced a one-reeler commemorating the festivities and presented it as a souvenir.

The centerpiece of the Warner Bros. tribute was a grand luncheon honoring the Legion’s officer corps. After an exchange of pleasantries and introductions, Harry M. Warner took to the podium to salute his guests—and to fire back at the Dies Committee’s allegations that communism was on the march in Hollywood. Though the object of ridicule in Popular Front circles, the hearings had left a nasty residue. Prior to coming to town, the Legion had sent the Hays office a letter listing the names of suspect stars whom they emphatically did not want to meet.46

After praising the Legionnaires as bulwarks of “true Americanism,” Warner belittled the “cheap accusation” that communism was rampant in Hollywood. On the contrary, Hollywood cinema and American values were locked in a beautiful friendship, each having “brought peace and happiness to us when nearly the rest of the world is miserable and afraid.” Warner did not mince words:

The only ism is Americanism: joyous veterans and their families given the run of the Warner Bros. lot during the American Legion convention held in Los Angeles (top) and Harry M. Warner, Legion Commander Daniel J. Doherty, and Jack L. Warner at the luncheon in honor of the Legion’s officer corps, September 19, 1938 (bottom). (Courtesy of the American Legion National Headquarters)

Certain bigots representing malcontents who want to ruin what they cannot rule whisper that Hollywood is run by isms. They lie when they say it. Let them show us the slightest proof. You may have heard communism is rampant in the picture industry. I tell you this industry has no sympathy with communism, fascism, Nazism, or any other ism—except for Americanism. We collectively and as individual studios are doing much, all we can do in fact, to teach the principles of true democracy to the outside world. I defy our accusers to prove this industry is run by isms. We have no need for regimented thinking in this country. We need no dictators to rule our private lives. Within the industry I am known as a man who calls a spade a spade. I tell you, whatever faith you may observe, we must all be Americans first, last and always.

Warner then circled in on his real target:

In recent years, since various foreign governments have fallen in to the bloody hands of dictators, autocrats and tyrants, other organizations have grown up within our own borders. These groups are inspired, financed, and managed by foreign interests, which are supplying a never ending stream of poisonous propaganda aimed, directly and indirectly, at the destruction of our national life. Those who seek to sow the seeds of discontent, of intolerance, and national destruction, are our common enemies, and we can never relax in our vigilance against them if America is to fulfill her splendid destiny.47

Warner’s fusillade received a thunderous ovation from the Legion officers.48 In the days that followed, the speech was also applauded coast-to-coast in the popular press. Newspapers quoted at length from Warner’s remarks and editorials lauded his sentiments. To keep the momentum going, the studio printed 150,000 pamphlets of the talk.

Throughout 1938 and 1939, both brothers gave interviews and speeches reiterating the sentiments in Harry’s speech to the American Legion. “We are descendents of immigrants and we know why our father came to America,” Jack explained. “Possibly we have a more acute appreciation of these ideals than those who accept American freedom as a matter of course. We believe that anyone who is anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic, anti-Protestant or anti-anything that has gone into the building of this country is anti-American.”49

Earlier in the decade, trying to wrap Marxism-Leninism in native garments, Earl Browder, the head of the Communist Party USA, had sought to rebrand his product with a catchy slogan that the targeted consumers never quite bought: “Communism is twentieth century Americanism.” Better salesmen with better wares, Harry M. and Jack L. Warner sold anti-Nazism as twentieth-century Americanism.

Like everyone with a professional interest in Hollywood, Dr. Georg Gyssling, the German consul in Los Angeles, was an avid reader of the motion picture trade press. On October 27, 1938, the Hollywood Reporter ran an item that caught his eye: “Krims Covers Spy Trial for Warners Picture.”

The short piece recounted the outlines of a sensational spy case splashing across the New York tabloids and unspooling in the newsreels.50 In January 1938, tipped by MI5, the British internal intelligence agency, the FBI uncovered a Nazi espionage ring that had been operating with impunity in and around New York. That June, a federal grand jury indicted eighteen persons, including known Nazi officials, on charges of conspiracy to steal military codes from the U.S. armed forces. Most of the indicted had already slipped through the fingers of federal authorities, jumping a liner back to Germany, but in late November three of the accused were brought to trial and found guilty. “The important point is that the American public must be made aware of the existence of this spy plot, and impressed with the dangers,” said U.S. district attorney Lamar Hardy, casting the trial less as a criminal prosecution than a teachable moment. “Our government and citizens must be awakened to the fact that it is imperative that we have an efficient counter-espionage service to protect us against such vicious spy rings as this.”51

Leon G. Turrou, the FBI agent in charge of the case, sold his inside story to the New York Post for $25,000 and published a book, Nazi Spies in America, in collaboration with reporter David G. Wittels, who had covered the trial for the paper. It was during the trial phase that Warner Bros. dispatched screenwriter Milton Krims to New York to follow the testimony for a possible motion picture project. The case was packed with film-friendly elements: cloak-and-dagger espionage, fifth column sedition, a passable Mata Hari, and the timely suspicion that the Nazis were no longer a remote threat but a clear and present danger.

Wise to the location of the levers of Hollywood power, Gyssling contacted Joseph I. Breen at the Production Code Administration. “My dear Mr. Breen,” he began, easing from faux solicitude to veiled threat. “Will you kindly see to it that the matter which is mentioned in the enclosed clipping of the Hollywood Reporter of October 27, 1938 will not result in difficulties such as we have unfortunately experienced before?”

Gyssling was referring to the difficulties experienced over I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany (1936) and The Road Back (1938), the two films that ignited his nastiest flare-ups with Hollywood over depictions of Germany, new and old. Ever since his appointment in 1933, the Nazi consul had badgered the Hollywood studios over any perceived slight to German honor, usually contacting Breen first, who in turn wearily passed the objections on to the offending studio. The year before, Gyssling had been chastened by a rebuke from Nazi ambassador Hans-Heinrich Dieckhoff, for sending a threatening letter to sixty actors performing in The Road Back. A serious overreach, Gyssling’s widely publicized fulmination resulted in a diplomatic incident when Secretary of State Cordell Hull protested the intimidation tactics. A provocation as raw as Confessions of a Nazi Spy roused him again to action—but via the backchannel route through Breen, not with a public denunciation of the project or a threatening letter to the cast. Ready to tussle and reap the advance publicity, Warner Bros. leaked Gyssling’s letter to Breen to the trade press, whereupon the story hit the wire services.52

After Warner Bros. reasserted its commitment to the project, a miffed Gyssling wrote Breen again. “I would greatly appreciate it, if you would let me know, whether this firm”—one can almost hear the Aryan distaste in his throat—“has really the intention to make a picture like that.”53

After nearly five years of playing middleman to the Nazi consul and the Hollywood moguls, Breen was fed up. “My dear Dr. Gyssling,” he responded in kind, “I have sent [your inquiry] along to the Warner Brothers studio, with the request that, if they care to do so, they communicate with you directly in the matter in which you wrote.”54

Breen might wash his hands of the Nazi, but he still needed to launder the most politically incendiary project that had crossed his desk since he set up shop in 1934. On the day before Christmas 1938, Warner Bros. producer Robert Lord sent the “temp script” over to the Breen office for a preliminary once-over. “It goes without saying that this script must be kept under lock and key when you are not actually reading it because the German American Bund, the German Consul, and all such forces are desperately trying to get a copy of it,” Lord cautioned Breen, who hardly needed reminding. “I know you appreciate the gravity of the situation and will do your utmost to cooperate with us.”

Breen did his utmost. Working through the Christmas holiday, he delivered a formal response before year’s end. Hollywood’s censor had good news for Warner Bros. “[T]he nation involved—Germany—seems to be represented honestly and without fraud or misrepresentation, and the ‘institutions, prominent people, and citizenry’ of the nation represented ‘fairly,’” he concluded, citing the apt section of the Code. “The activities of this nation and its citizenry, as set forth in this script, seem to be supported by the testimony at the trial and the evidence adduced by the United States Attorney and the federal operations.” (After sending his formal response to Warner Bros., Breen continued mulling the implications of Code-sanctioned anti-Nazism for the rest of the day. He composed a second letter on the question of what he italicized as “general industry policy” and worked up a five-page synopsis of the project for Will Hays. Neither document was sent up the chain of command.)55

The restatement of the distinction between “fairly” and “sympathetically”—a parsing that had been on the books since 1936—broke the logjam blocking the passage of anti-Nazi material through the Breen office. Breen had previously granted a Code seal to I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany, but that was an obscure independent film, and would later clear Amkino’s Professor Mamlock (1938), but that was an obscure foreign film. Confessions of a Nazi Spy was a high-profile provocation from a major studio: the Code seal and the Warner Bros. shield flashed a bright green light signaling that anti-Nazism, if based on credible evidence, was now a fit subject for Hollywood cinema. Again, the Code could not be blamed if Hollywood flinched before the Third Reich.

Hoping not just to slip through but to widen the loophole, Lord sent Breen a list of citations from the federal trial. “Some time in the future in case you are questioned, here is a list of our sources of inspiration in the Nazi story,” he offered, playing the helpful research assistant.56

Within the ranks of the Breen office, the break with precedent was dramatic enough to incite a rare instance of internal dissent. In an in-house memo, Code staffer Karl Lischka, a former journalist for the Catholic press and a friend of Breen’s since the 1920s, stated his objections for the record. “Supposing everything in this story is true and fair, it still looks like an impending mistake. I fear it will be one of the most memorable, one of the most lamentable mistakes ever made by the industry,” Lischka predicted. “Will there be a Storm over America?” he asked, using an early title for the project. “There will be a Hurricane!”57

Lischka’s forecast was flat wrong: the winds of change were blowing in another direction. Warner Bros. had an emergent cultural zeitgeist at its back, one it had nurtured with its Americanism shorts, its radio broadcasts on KFWB, and in allegorical anti-Nazi feature films like Black Legion (1936) (against homegrown racist vigilantism), The Life of Emile Zola (1937) (against antisemitism), and They Won’t Forget (1937) (against mob rule and lynch law).

Given the sensitivity of the subject matter, the early versions of the shooting script for Confessions of a Nazi Spy were handled with the security protocols usually reserved for top secret documents. The tensions did not dampen Robert Lord’s sense of humor when he selected a diversionary title for the hush-hush project—though not everyone in the loop was amused. “Dear Bob,” wrote Walter MacEwen, assistant to Hal B. Wallis, head of production for Warner Bros. “Mr. Hays and Mr. Breen are afraid the title ‘Hot Lips’ has too much of a sex connotation for use on the Krims assignment. Can you suggest something else—seriously?”58 Besides “Hot Lips,” Confessions of a Nazi Spy also went under the pseudonyms “I Spy,” “The World Is Ours,” and “Storm over America.”

However glib Lord might be, Hal Wallis was dead serious about keeping the project on a strict need-to-know basis. Hearing that Lord and director Anatole Litvak had shared the script with actors Francis Lederer and Paul Lukas, Wallis issued a stern reprimand. “I don’t have to tell you the dynamite that is in this story and I see no reason for allowing a lot of actors to be familiar with the contents of our script.”59

When production commenced, Confessions of a Nazi Spy was shot on a closed set marked with deceptive signage to misdirect potential saboteurs dispatched from either Nazi Germany or the German American Bund. Accidents during production—a falling light from a catwalk nearly brained actor Edward G. Robinson—took on sinister overtones. Warner Bros.’ internal security was beefed up and placed on high alert.60 In typical Hollywood fashion, the secretive atmosphere surrounding the film was then leaked to the press: publicizing the secrecy for publicity value.61

To lend verisimilitude to its espionage thriller, the studio that had banned the March of Time’s Nazi exposés lifted the screen magazine’s two trademark techniques—the Voice of God narrator for exposition and the use of newsreel footage for flashbacks to the recent past. Hired for voice-over duties was radio actor John Deering, whose no-nonsense baritone would be heard to equally authoritative effect later that year in The Roaring Twenties (1939). “Be sure that [Deering] has plenty of volume on the track and that he comes through clear, sharp, and loud,” Wallis instructed the sound engineers at Warner Bros. “We want plenty of body to the whole thing so that we get the forceful effect as they do in the March of Time.”62 Earlier Wallis had considered hiring March of Time narrator Westbrook Van Voorhis himself to do the voice-over. In a nod to the central role radio was playing in the breaking news from Europe, Deering is shot in blackened silhouette before a microphone, as if broadcasting an urgent news bulletin.

Two departures from Hollywood convention immediately set the film apart. First, except for a single title card, there were no opening credits. All the actors and artists agreed to forgo upfront billing for a cold opening. (The cast credits and main artists were run at the end of the film.) Second, the standard legal disclaimer professing that “all characters are fictional and any similarity to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental” was omitted. The characters and incidents were real and named, and the story was factual not fictional. There was nothing purely coincidental about Confessions of a Nazi Spy.

Breathless and didactic, Confessions of a Nazi Spy is an oddball hybrid, a spy thriller and courtroom drama sprinkled with elements of marital discord (America’s head Nazi is a philandering husband with a jealous wife). The probe into Nazism begins at a raucous meeting of a group that can only be the German American Bund, where the crowd is being harangued by Dr. Karl Kassel (Paul Lukas), a slithery academic type more in the mold of the skeletal Joseph Goebbels than the burly Fritz Kuhn. “America is founded on German blood and culture!” he shrieks. Listening dubiously in the audience, a brave member of the American Legion stands up to oppose the Nazi’s nativism with dialogue lifted nearly verbatim from Harry M. Warner’s speech to the American Legion: “We don’t want any isms in this country except Americanism!” he thunders. When a loyal German American raises his voice to defend the Legionnaire, the American brownshirts launch a wild, chair-throwing melee.

Yet Dr. Kassel’s hate-mongering reaches receptive ears. Hopped-up on the Third Reich rhetoric, the twitchy, delusional Kurt Schneider (Francis Lederer, himself a refugee from Nazi Germany) is a vainglorious German-born loser who offers his services to Nazi intelligence, dragging along his good-natured but dim army buddy Werner (Joe Sawyer) as hapless wing man. Schneider is an amateur and a bumbler, but he delivers the top secret goods to his Nazi masters.

For the typical moviegoer in 1939, more eye-and-ear-opening than the plot or the politics of Confessions of a Nazi Spy was the visual drapery and sonic atmosphere. The insignia, salutes, and catchphrases of Nazism—huge swastikas, giant portraits of Hitler, and throngs of rabid Americans in Nazi garb shouting “Seig heil!,” arms upraised in the Nazi salute as the Horst Wessel song rings out on the soundtrack—had never before been seen and heard in a major feature film. In American territory, the Nazi set design, the German beer halls, the German accents, and the free-wheeling operation of Nazi military men and espionage agents in New York conjured an elaborate fifth column crisscrossing America, a cancer eating away at the body politic.

With the Nazi contagion spreading, Kassel returns to headquarters in Germany to get his marching orders directly from a high-ranking Nazi official who is never named but is a dead ringer for Joseph Goebbels.f While Dr. Kassel is in transit, a flashbacking montage reviews the history of Nazi Germany in the six years since 1933. Narrated by Deering in his best Vorhissian timbre, the rapid-fire cascade of images keeps pace with the accelerating momentum of Nazi aggression. For the cinematic blitzkrieg, the Warner Bros. montage unit unleashed its full arsenal of special effects: wipes, animation, dissolves. The newsreel-laden history lesson would serve as a template for the techniques used by Frank Capra in his Why We Fight series (1942–1945) during World War II.

As Warner Bros. rolls out its own anti-Nazi propaganda, the techniques of Nazi propaganda—the insidious methods deployed to bore from within—are an obsessive concern. The Goebbels surrogate instructs Dr. Kassel to dress up Nazism “in the American flag” and spread the Big Lie coast-to-coast. Smuggled stateside as cargo in German ocean liners, a blizzard of toxic paper (“vitriolic, scurrilous propaganda”) rains down on America like disease-bearing ticker tape: dropped from planes and tossed out of windows, flyers, pamphlets, and posters choke America in a cloud of foreign-bred hatred. The litter is tossed from the upper floors of office buildings, plastered on walls, and even stuffed into the lunchboxes of American schoolchildren.g

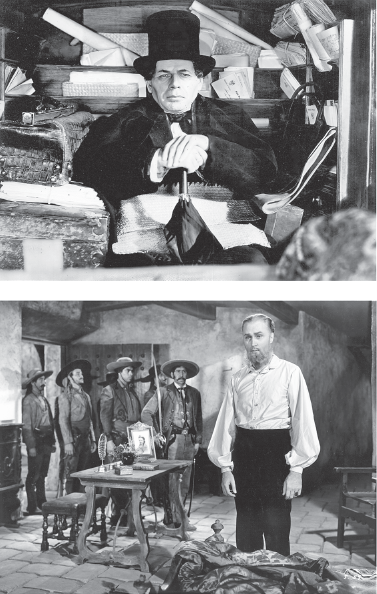

An education in propaganda: a Joseph Goebbels lookalike (Martin Kosleck) orchestrates the ideological invasion of America in Warner Bros.’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939).

However, whether printed or spoken, the Nazi propaganda is close-mouthed about the people the regime most despises. Nazi agents in American refer darkly to “subversive elements” and an “insidious international conspiracy of desperate subhuman criminals,” but the word Jew is never uttered or spotted in the signage—no shouts of “Jews out!” or caricatures of hook-nosed perverts. “Nazi” was emblazoned in the title, but “Jew” was not heard on the dialogue track.

The G-man who brings down the spy ring is Ed Renard (Edward G. Robinson), who breaks the case when the jealous wife of Dr. Kassel finds her husband is tomcatting around with a young blonde acolyte. It is not FBI vigilance or military intelligence that exposes the Nazi network operating under the nose of federal authorities (“the FBI does not have a counter-intelligence program,” sneers a Nazi), but a lucky break. Unlike most Hollywood paeans to G-men, which reassured Americans that the awesome apparatus of federal law enforcement was maintaining domestic tranquility, Confessions of a Nazi Spy depicts a nation whose watchmen are asleep at the switch.

In the final reel, the remaining Nazi spies stand before the bar of justice in a New York courthouse. Winding up his summation to the jury, the district attorney looks into the eyes of the other jury—in the theater seats—for a direct-address history lesson. As he indicts Nazi aggression and the sinister propaganda that softens up the American people, another brisk newsreel montage illustrates his words.h The jury—on screen and presumably off—renders its unanimous verdict of guilty.

With the Nazis convicted and the threat, for the moment, contained, the prosecutor and the FBI agent go to a nearby diner to ponder the nature of Nazism. “You see these Nazis operating here and you think of all those operating in Germany, and you can’t help feeling that they’re—well—absolutely insane,” marvels a disbelieving agent Renard, shaking his head. “We see what’s happened in Europe. We know what they’re trying to do here. It all seems so unreal—fantastic—an absurd nightmare.” Yet “when you think of its potential menace, it’s terrifying.” As Renard speaks, the diner owner and a pair of regular American guys shoot the breeze about the dire headlines from overseas. “This ain’t Europe,” snorts the diner owner. The common sense and firm courage of the average Joe will protect America from the Big Lie that is Nazism.

Or will it? Against the well-coordinated and ruthless machinations of Nazi espionage, the hapless state of American counterintelligence offers a pitiful line of defense. J. Edgar Hoover’s G-men may have neutralized the threat from the gangsters of the early 1930s, but up against the agents of Nazism the feds are undermanned and outmaneuvered. The stateside Nazis kidnap suspected turncoats and sneak them back in to Germany, easily escaping the porous security at American ports. American diplomatic protests are ignored. It can happen here.

After production wrapped on Confessions of a Nazi Spy, the ad-pub boys for Warner Bros. went into overdrive, ballyhooing the gutsy patriotism of “the picture that calls a swastika a swastika!” No mere commercial venture, “it was Warners’ American Duty to Make It!” As for exhibitors: “It Is Your American privilege to Show It!” Sadly, the blather of previous ad-pub hyperbole had diminished the power of words like “great” and “colossal,” but Confessions of a Nazi Spy really was great:

Great in the sense that Warner Brothers have given Hollywood the voice of protest. They have dramatized the protest of the American people. THERE HAS NEVER BEEN AN AMERICAN PICTURE LIKE CONFESSIONS OF A NAZI SPY.63

A gala premiere was scheduled for April 27, 1939, at Warners Beverly Theater. “Are you nervous about the Nazi Spy preview?” quizzed the Hollywood Reporter.64 Anticipating trouble—perhaps a domestic replay of the Nazi trashing of All Quiet on the Western Front—Warner Bros. took no chances. The Los Angeles Police Department was out in force, supplemented by forty members of the studio’s private security force. Stationed inside, plainclothesmen scanned the crowd for troublemakers, ready to leap on any Bund minion planted in the audience to screech “Judenfilm!”

The precautions were unnecessary. The only sounds from the adoring crowd were the bursts of applause that rippled throughout the screening. At the close, a rousing cheer and thunderous ovation lasted for the duration of the end credits. “The heaviest police guard handled one of the quietest preview crowds in recent motion picture history,” reported Daily Variety under a resonant headline: “Big Police Guard at Nazi Preview but All’s Quiet.”65

Telegrams of congratulations poured in to the studio. “Last night, the motion picture had a Bar Mitzvah,” Warner Bros. producer Lou Edelman told Jack Warner. “It came of age.”

Buoyed along by an admiration not wholly aesthetic, the reviews were five-star hosannas. “Daring, fearless, provocative, gripping with an intensity seldom seen in screen offerings, Confessions of a Nazi Spy will be one of the most discussed and argumentative films of current time,” Daily Variety predicted. “It is as timely as this morning’s scare-heads; as disturbing as an impending catastrophe.”66 Most satisfyingly, the film earned plaudits from forums more usually given to smug condescension. “Picture biz is getting a new hunk of applause and hurrahs from a new quarter as a result of the production of Juarez and Nazi Spy,” the trade paper continued. “Arty and radical magazines throughout the country have gone hook, line, and sinker for both films.”67

The German American Bund, the unbilled villains in Confessions of a Nazi Spy, fought back with slurs and disinformation. “Motion pictures of this type disgust American audiences and destroy foreign markets for American-made pictures, and deprive our thousands of unemployed actors, technicians, and extras of opportunity to work,” it claimed in a leaflet signed by a bogus group called the Committee of Unemployment, Hollywood Actors and Technicians. The flyer urged workers in the film industry to oppose “the control of the Jews” in their unions and to “demand that your union leaders take immediate steps to end these un-American Jewish practices.” Alleging libel, Bund chief Fritz Kuhn filed a $5,000,000 lawsuit against the film and demanded an injunction prohibiting distribution.68 (The injunction was denied and the libel suit was ultimately dismissed—to the displeasure of Warner Bros., which was eager to go to court. By then, in 1940, Kuhn was in jail for embezzling Bund funds.)

German consular offices across America also tried to suppress Confessions of a Nazi Spy, but the diplomats found that since the revelations from the New York espionage case, their stock as envoys of a “friendly government” had fallen precipitously. In a letter of protest sent to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, Dr. Hans Thomsen, the German chargé d’affaires, denounced the film “as an example of the pernicious propaganda that has been ‘poisoning’ German-American relations.” The State Department tersely informed Dr. Thomsen it had no legal right to bar the distribution of the film.69 Hermann Gasttriech, Nazi vice consul in Kansas City, charged that “the picture tends to incite discontent and racial feeling and violates the American principles of justice and equality for all regardless of race or creed.”70 The Kansas City Censor Board, not known for cutting-edge commitment to freedom of expression, ignored the diplomatic protest and passed the film.

Given the reviews and the buzz around Hollywood, Warner Bros. expected a huge payday from Confessions of a Nazi Spy. However, for all the brouhaha and ballyhoo, the cloak-and-dagger production process and the precedent-shattering Code imprimatur, the headlines generated by the film did not generate lines at the box office. The financial returns for the film were only so-so—not a failure, but not the breakout hit Warner Bros. had banked on.